Abstract

Straw returns to the soil is an effective way to improve soil organic carbon and reduce air pollution by straw burning, but this may increase CH4 and N2O emissions risks in paddy soils. Biochar has been used as a soil amendment to improve soil fertility and mitigate CH4 and N2O emissions. However, little is known about their interactive effect on CH4 and N2O emissions and the underlying microbial mechanisms. In this study, a 2-year pot experiment was conducted on two paddy soil types (an acidic Utisol, TY, and an alkaline Inceptisol, BH) to evaluate the influence of straw and biochar applications on CH4 and N2O emissions, and on related microbial functional genes. Results showed that straw addition markedly increased the cumulative CH4 emissions in both soils by 4.7- to 9.1-fold and 23.8- to 72.4-fold at low (S1) and high (S2) straw input rate, respectively, and significantly increased mcrA gene abundance. Biochar amendment under the high straw input (BS2) significantly decreased CH4 emissions by more than 50% in both soils, and increased both mcrA gene and pmoA gene abundances, with greatly enhanced pmoA gene and a decreased mcrA/pmoA gene ratio. Moreover, methanotrophs community changed distinctly in response to straw and biochar amendment in the alkaline BH soil, but showed slight change in the acidic TY soil. Straw had little effect on N2O emissions at low input rate (S1) but significantly increased N2O emissions at the high input rate (S2). Biochar amendment showed inconsistent effect on N2O emissions, with a decreasing trend in the BH soil but an increasing trend in the TY soil in which high ammonia existed. Correspondingly, increased nirS and nosZ gene abundances and obvious community changes in nosZ gene containing denitrifiers in response to biochar amendment were observed in the BH soil but not in the TY soil. Overall, our results suggested that biochar amendment could markedly mitigate the CH4 and N2O emissions risks under a straw return practice via regulating functional microbes and soil physicochemical properties, while the performance of this practice will vary depending on soil parent material characteristics.

Keywords: paddy soil, biochar, straw return, CH4, N2O, functional genes

Introduction

Global warming caused by the continued increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is expected to exert a severe impact on the stability of natural ecosystems and sustainable development of human society (Smith and Fang, 2010). The mitigation of GHG emissions remains a formidable challenge in the quest to slow climate change. The respective global warming potentials of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) are 23- and 298-fold higher than that of carbon dioxide (Munoz et al., 2010), and contribute around 17 and 6% to radiative forcing, respectively (WMO, 2017). Paddy soil is one of the important sources of atmospheric CH4 and N2O, with average annual emissions of 7.22–8.64 Tg and 88.0–98.1 Gg in China, respectively (Xing, 1998; Li et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2010). A strategy to mitigate CH4 and N2O emissions in rice paddies is imperative.

Crop residues have been widely applied in agriculture as a source of nutrients to improve soil fertility, and showed significant effects on improving soil organic C stocks (Li et al., 2010), reducing environmental pollution associated with straw burning (Kharub et al., 2004; Romasanta et al., 2017), and regulating carbon and nitrogen cycling (Lugato et al., 2006). However, the application of crop residues can increase the production of atmospheric GHGs (Zou et al., 2005; Ma et al., 2008; Hang et al., 2014). For example, the global warming potential was significantly enhanced by straw incorporation from a rice paddy field, with CH4 increase by 3–11 times in straw-contained soils compared to the control (Ma et al., 2007). Therefore, it is crucial to find a method to mitigate the emissions of GHGs induced by straw application in rice paddy fields.

Biochar, a carbon sequestrating and recalcitrant material, is produced by the pyrolysis of plant residues under a zero or limited oxygen condition (Cao et al., 2011), possessing the characteristics of a high pH, high cation exchange capacity (CEC), and a high hydrophilic characteristic, large porosity and surface area (Lehmann et al., 2011). Biochar has been applied to soil as an optional amendment to improve soil fertility and grain yields via the promotion of nutrient turnover (Zhang et al., 2010; Kang et al., 2016). Soil with a low fertility or pH value can be improved with biochar amendment (Bakar et al., 2015). Biochar amendment can also regulate CH4 and N2O emissions from rice paddy soils (He et al., 2017). For example, CH4 emissions were suppressed by 39.5% by adding biochar to a paddy soil under elevated temperature and CO2 (Han et al., 2016). However, another study found that N2O emissions significantly decreased following biochar addition, while CH4 emissions increased, probably resulting from an improvement in microbial growth due to the supply of additional C (Singla and Inubushi, 2014). Either no effect (Brassard et al., 2016) or stimulation (Yu et al., 2013) of biochar-induced GHG emissions have also been observed, illustrating an apparent dependence on biochar and soil properties (Singla and Inubushi, 2014). However, the mechanism remains unclear as to how the soil interacts with biochar with respect to CH4 and N2O emissions.

CH4 and N2O emissions in paddy soils reflect the balance of production and consumption processes which are associated with microbial activities in soil (Yan et al., 2000; Bodelier, 2015). For example, soil organic matter decomposed by various microorganisms is ultimately utilized by the methanogenic archaea with the production of CH4, which can be consumed by the methanotrophic proteobacteria as a sole source of carbon and energy before release to the atmosphere (Bridgham et al., 2013). N2O emission from soil is also dependent on the balance of N2O reduction and production processes and is influenced by multiple factors. However, there are no consistent conclusions on the influence of biochar amendment on soil microbial communities involved in CH4 and N2O production and consumption. Improved abundance of N2O-reducing bacteria has been observed after biochar amendment, promoting the reduction of N2O to N2 during denitrification thus decreasing N2O emissions (Harter et al., 2014). Similarly, several other studies reported that biochar amendment reduced N2O emissions by increasing nitrous oxide reductase encoding gene (nosZ) due to soil pH increases (Van Zwieten et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2014). Conversely, increased N2O emissions stimulated by biochar amendment in a rice paddy soil was found to be correlated with the increased bacterial ammonia monooxygenase encoding amoA gene, but not with nitrous oxide reductase encoding gene (nosZ) and nitrite reductase encoding genes (nirK and nirS) (Lin et al., 2017).

Among the environmental and edaphic factors influencing the microbial processes, the soil C/N ratio plays a pivotal role in controlling the shifts among key functional microbial processes with separate redox conditions (Kraft et al., 2014). Remarkably, a higher C/N ratio would favor anammox or dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) while a lower ratio would contribute to denitrification (Tiedje et al., 1982; Kraft et al., 2014; Shan et al., 2016). Furthermore, the soil redox potential (Eh) and pH are also essential factors largely deciding the availabilities of electron transfer for microbial-mediated processes and microbial metabolism (Kralova et al., 1992; DeAngelis et al., 2010). Otherwise, soil carbon dynamics are highly relevant with the growth of microorganisms involved in GHGs (Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, the amount of straw addition could regulate GHGs emissions not only via influencing the availability of soil organic C (Wu et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhong et al., 2017), but also via adjusting the soil C/N ratio, and different amounts of straw returns exerted different effects on soil microbial activities and GHGs emissions (Naser et al., 2007). Furthermore, individual rather than interactive effects of straw and biochar amendments on CH4 and N2O emissions were the focus of earlier studies (Shen et al., 2014; Ly et al., 2015; Thammasom et al., 2016). Consequently, more studies are required to estimate the influence of biochar amendment on CH4 and N2O emissions under different rates of straw incorporation, and the processes controlling the gaseous emissions should be identified. Therefore an experiment involving straw and biochar amendments was conducted in two types of paddy soils to evaluate the dynamics of CH4 and N2O emissions in this study. Two rice straw levels were applied to construct different soil C/N ratio, and the effects of biochar on CH4 and N2O emissions were monitored. Microbial functional genes involved in the production and consumption of CH4 and N2O were analyzed. The specific objectives were to: (1) Evaluate the effects of the biochar addition on the CH4 and N2O emissions in rice paddy soils under different rates of straw incorporation; (2) Quantify the responses of different functional microbial groups to biochar and straw amendments under two contrasting soil types and evaluate whether the difference in microbial groups might explain the variation in CH4 and N2O formation and release from the soils.

Materials and Methods

Soil Information and Pot Experiment Setup

The paddy soils were originally collected from Taoyuan (TY, 111.48° E, 28.90° N), Hunan Province, and Binhai (BH, 119.84° E, 34.01° N), Jiangsu Province, rice production areas in Southeast China. The soils were classified as an Inceptisol and an Utisol, respectively, according to the USDA Taxonomy. Fresh soils were air dried to 30–40% maximum field capacity and then passed through a 2 mm sieve, followed by a homogenous mixing before being used for the pot experiment.

The pot experiment was located outdoors in a farm field which received natural day light and ambient temperature in the suburb of Beijing. The experimental design involved two rice straw levels with or without biochar addition, i.e., five treatments: (1) S0, no addition of rice straw (control); (2) S1, 0.33% (w:w) rice straw addition (equal to all aboveground biomass return); (3) S2, 0.66% (w:w) rice straw addition; (4) BS1, 0.33% (w:w) rice straw addition plus 2.0% (w:w) biochar (equal to 45 t ha−1); and (5) BS2, 0.66% (w:w) rice straw addition plus 2.0% (w:w) biochar. The rice straw used in the experiment was collected from the area where soil samples were collected, and ground into a powder before use. Biochar was pyrolytically produced from maize straw feedstock under 450°C, and was purchased as a commercial product from Liao Ning Golden Future Agriculture Technology Co., Ltd., with a pH of 9.2, and total carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus of 679, 9.4, and 7.8 g kg−1, respectively. Three replicate pots (26 cm in diameter and 30 cm in height) were setup for each treatment, and each pot contained 10 kg soil (dry weight). For the rice growing season in 2016, before pots were filled, straw or straw plus biochar were thoroughly mixed with the soil according to the treatment, and phosphorus and potassium were applied as a basal fertilizer mixture for all treatments at 90 and 180 kg ha−1 P2O5 and K2O, respectively. All pots were flooded for 10 days and then two rice seedlings were transplanted to each pot at day 10 to avoid seedling burnt. Nitrogen fertilizer (72 kg N ha−1 as urea) was dissolved in 200 ml deionized water and applied into surface water of each pot before 1 day rice was transplanted. The remaining urea fertilizer (108 kg N ha−1 N) was applied after tillering at day 60. The soils were continuously flooded to a depth of 2.5 cm except for 2 weeks of drainage during tillering (from day 43 to day 58, corresponding to days 33–48 after rice transplanting). After the rice growing season in 2016, pots were preserved in situ and covered with tarpaulins to reduce anthropogenic disturbance. In spring 2017, tarpaulins were removed and all pots were flooded for 1 month before rice straw and basal fertilizers were applied into soils. The water and fertilizers regime, rice transplanting and daily management were the same as those in 2016, except that biochar was no longer added.

Gas Sampling and Measurement

The soil N2O and CH4 fluxes were measured using the static chamber method during the whole rice growing season at 2- or 3-day intervals from 12 June 2016 to 21 August 2016 and from 8 March 2017 to 19 July 2017. A transparent Plexiglass chamber of 30 or 60 cm in height was affixed by a water-filled groove to the top edge of the soil column to ensure an air-tight system. An electrical fan was attached on the top of the chamber to mix the gas in the headspace. On each sampling day, gas collecting was conducted between 10 and 11 a.m., and gas was collected from each pot at 15 min and 30 min after chamber was sealed. For each time, 30 ml of gas was taken from the chamber using a syringe connected with a three-way valve, and then stored in a glass cylinder for next measurement. Gas samples were measured by using a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890B, Santa Clara, CA, United States) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and an electron capture detector (μECD), and the gas sample (20 ml) was fed into the GC using a syringe manually. Gas fluxes were calculated using a linear regression analysis.

Where: F was the flux of N2O or CH4 (μg N2O-N m−2 h−1 or μg CH4-C m−2 h−1), ρ was the density of the trace gas at 0°C and 101.3 KPa (kg m−3), P was the atmospheric pressure of the experimental site (KPa), V was the volume of chamber (m3), A was the surface area of the chamber, Δc/Δt was the rate of N2O or CH4 accumulation in the chamber (μg m−3 h−1), T was the chamber mean air temperature in Celsius.

Cumulative N2O and CH4 emissions (E, kg N ha−1 for N2O, kg C ha−1 for CH4) were calculated by the following equation:

Where: F was the gas flux (μg N2O-N m−2 h−1 or μg CH4-C m−2 h−1), n was the gross number of gas measurement, i was the time of sampling, (ti+1 − t) represented the days between the two conjoint gas measurements.

Soil Sampling and Physicochemical Analysis

Soil samples were taken after gas sampling at day 18, day 58, and day 120, corresponding to rice seedling, tillering, and heading stages, respectively. A soil core (4 cm in diameter) at a depth interval of 0–5 cm was collected from each pot at each sampling time, the core being 10 cm distant from the rice plant. Finally, three cores in each pot were sampled equidistant along the edge of the soil columns to minimize the disturbance. In situ Eh measurements were made at rice-transplanting and before soil sampling days by using a PRN-41 soil Eh meter (DKK, TOA, Tokyo, Japan). After a homogenous mixing, soil subsamples were stored at 4°C and −40°C for physicochemical determinations and molecular analyses, respectively.

Soil pH was measured in a soil and water suspension (1:2.5 w/w) using a glass electrode. Soil moisture was measured as loss in weight after oven drying at 105°C to constant weight. and were extracted with 1 M KCl solution and determined by using a continuous flow analytical system (AA3, SEAL analytical, Germany). Soil dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4 and determined by a TOC analyzer (Multi N/C 3100, Analytik Jena, German). Soil total carbon (TC) and total nitrogen (TN) were measured by an Elemental analyzer (Vario EL III-Elementar, Germany).

DNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR

Total DNA was extracted from 0.3 g freeze-dried soil by using a Power Soil DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio, Carlsbad, CA, United States) under the guidance of the manufacturer’s instructions, and the quality of the extracted soil DNA was checked by an agarose gel electrophoresis. All the extracted DNA products were stored at −40°C for the next analysis.

Real-time PCR was conducted on an IQ2 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, United States). The abundances of microbial functional genes related to N2O emission (archaeal and bacterial amoA, nirK, nirS, and nosZ genes), and methanotrophs pmoA gene (methane monooxygenase encoding gene) and methanogens mcrA gene (methyl coenzyme M reductase encoding gene) were quantified using a SBYR Green assay with the primer pairs and thermal cycle programs as listed in Supplementary Table 1. The qPCR reactions were executed in a 25 μl mixture containing 12.5 μl SYBR Green Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa Bio Inc.), 1 μl of each primer for nirK, nirS and nosZ (clade I) genes at 10 μM, 2 μL of each primer for archaeal and bacterial amoA, nosZ (clade II), mcrA and pmoA genes at 10 μM, and 2 μl of DNA template (1–20 ng). A negative control without DNA template was also conducted in all the qPCR runs. Melting curves aiming to ensure the reaction specificity were conducted at the end of each PCR run. QPCR results were accepted when melting curve is under a single peak, and the amplification efficiencies were in the range between 86.3% and 110.0% with a R2 value greater than 0.95. To engender a standard curve for qPCR, the amplifications of target genes were performed with the same primer sets mentioned above, following a cloning sequencing. The plasmids DNA containing the correct insert were extracted, purified and quantified, following a 10-fold dilution series as standards for qPCR. Soil DNA samples, standards and negative controls were all included in triplicates in each run.

High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis of pmoA and nosZ Genes

To explore the influence of different treatments on microbial community, all soil samples collected at the seedling stage were subjected to high-throughput sequencing analysis for pmoA and nosZ I genes, and the soils from S0, S2, and BS2 treatments were selected for survey on the variation of nosZ I gene containing community over time. The pmoA and nosZ I genes were amplified with the primers and PCR conditions listed in Supplementary Table 1 in triplicates. And a unique barcode of 6 bp in length were attached in the forward primer at the 5′ end to distinguish the amplicons from different soil samples. Metabarcoded amplicons were purified and sequenced by Illumina Miseq PE300 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, United States).

The sequencing-read data sets were processed using QIIME 1.90 (Caporaso et al., 2010) standard operation pipeline. The raw data was demultiplexed according to the barcode of each sample. Usearch (version 10.0) program (Edgar, 2013) was used to achieve the mergence between the forward and reverse reads, followed by the trimming barcodes from sequences, demultiplexing and quality filter of sequence. Then, filtering chimera, clustering Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) at 97% sequence identity and picking out representative sequences from each OTU (Edgar, 2013) were all operated in the same program. Further, the representative sequences were compared to the public databases, GenBank, by using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI1) BLASTn to guarantee the maximum sequence similarity was a pmoA or nosZ gene. The annotation for taxonomic information of the methanotrophs and nosZ gene containers were conducted based on the Fungenes database2 and further confirmed by blasting the representative sequence of each OTU against the NCBI GenBank database. To correct the sampling effort, OTUs resampling were rarefied at minimum number of sequences (5,689 reads for pmoA gene and 8,356 reads for nosZ gene) per sample for downstream analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS software (version 19, IMB, Inc., United States). Spearman’s correlation was used to determine the relationships among the N2O and CH4 emissions, soil properties and abundance of microbial functional genes at different rice growing stages. Repeated measures ANOVA was applied to assess the difference of soil properties and gas emissions in different rice growing stages and treatments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to test for differences in gas emissions, soil characteristics and abundance of microbial functional genes, while significant difference was defined as P < 0.05.

Mothur (Schloss et al., 2009) was operated to analyze the alpha and beta diversity. Beta diversity was characterized by Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices based on OTU matrices. Cluster analysis was performed with UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean) using Bray–Curtis distance measures. To identify the critical parameters driving the community diversity of denitrifier, canonical correlation analysis (CCA) were performed using community ecology vegan package of R software (3.2.4). The envfit function (999 permutations) was used to identify the environmental variables, which significantly contributed to the soil microbial community variance.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The representative sequences retrieved in this study were deposited in the GenBank database and assigned accession numbers from MH909699 to MH909751 for pmoA gene, from MH909601 to MH909698 for nosZ gene.

Results

Soil Physicochemical Properties

The TY soil had an initial pH(H2O) of 5.7, DOC at 89.07 mg kg−1, total N at 2.20 g kg−1, while the BH soil had an initial pH(H2O) of 7.6, DOC at 33.28 mg kg−1, and total N at 1.30 g kg−1. During the whole rice growing season in 2016, soils properties were significantly impacted by the straw and biochar amendments. For the TY soil, straw addition (S1 and S2) significantly increased DOC by 2.7–42.4%, but showed no significant impact on the soil C/N ratio over the rice growth stage, in comparison with no straw control (S0) (P < 0.05) (Table 1). When compared with straw addition alone (S1 and S2), the TY soil pH significantly increased by 0.5–0.8 unit, DOC by 38.16–40.90% and C/N ratio by 24.07–46.16% with the biochar amendment (BS1 and BS2) at day 18, and similar significant increases of soil pH, DOC, and C/N were also observed at day 58 and day 120 (Table 1, P < 0.05). For the BH soil, there was no significant effect on the soil C/N ratio and pH with straw addition alone (S1 and S2), but soil DOC increased by 0.90- to 1.22-fold at day 18 (Table 1), in comparison with S0 treatment. The C/N ratio significantly increased by 24.10–28.87% and TN by 4.17–23.85% with the biochar amendments (BS1 and BS2) at day 18, compared with treatments without the biochar amendment (S1 and S2). Notably, soil pH increased over time in both soils from 6.1 to 7.6 in TY and from 7.7 to 8.7 in BH (Table 1) due to the occasional drainage during the heading stage. Both the rice growing stages and treatments showed significant impacts on soil properties, such as DOC and Eh, and there was no significant interaction of the treatments and rice growth stages on the , TC and C/N ratio (Table 2).

Table 1.

Physiochemical parameters in two paddy soils over rice growth stages in 2016.

| Days after straw addition | Treatment | pH | Eh-surface (mV) | Eh-subsurface (mV) | DOC (mg kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | TN g kg−1 | C/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 days (seedling stage) | TY-S0a | 6.4 ± 0.1Bb | 12.9 ± 31.4A | 75.7 ± 125.7A | 61.98 ± 18.33B | 49.74 ± 3.74A | 0.24 ± 0.15A | 2.14 ± 0.08B | 9.53 ± 0.13C |

| TY-S1 | 6.1 ± 0.02C | 19.3 ± 43.3A | 38 ± 85.1A | 66.19 ± 5.45B | 51.19 ± 4.07A | - | 2.18 ± 0.10B | 9.64 ± 0.25C | |

| TY-S2 | 6.4 ± 0.13B | 6.9 ± 59.6A | 157 ± 83.4A | 88.25 ± 31.81AB | 50.6 ± 13.62A | 1.47 ± 2.15A | 2.2 ± 0.05AB | 10.03 ± 0.09C | |

| TY-BS1 | 6.9 ± 0.13A | -105.3 ± 40.3B | 132 ± 26.6A | 93.26 ± 13.39AB | 52.91 ± 9.43A | 0.85 ± 1.11A | 2.14 ± 0.12B | 11.96 ± 1.27B | |

| TY-BS2 | 6.9 ± 0.07A | -90 ± 40.7B | 136 ± 91.9A | 121.93 ± 31.02A | 45.61 ± 13.14A | 0.11 ± 0.16A | 2.34 ± 0.05A | 14.66 ± 1.44A | |

| BH-S0 | 7.9 ± 0.22a | 180.8 ± 12.4a | 30.3 ± 52.5a | 46.10 ± 4.68c | 8.71 ± 6.88a | 9.93 ± 5.65a | 1.11 ± 0.02c | 19.43 ± 0.36b | |

| BH-S1 | 7.8 ± 0.11a | 3.8 ± 32.7b | -224.7 ± 140.3b | 87.48 ± 12.78abc | 12.75 ± 3.02a | 0.84 ± 0.53b | 1.44 ± 0.14ab | 17.99 ± 0.26b | |

| BH-S2 | 7.7 ± 0.05a | -6.1 ± 38.3b | -169.7 ± 67.6b | 102.53 ± 33.93ab | 6.93 ± 4.69a | 0.32 ± 0.34b | 1.3 ± .15bc | 18.8 ± 0.32b | |

| BH-BS1 | 7.8 ± 0.06a | -32.1 ± 12.9b | -132.7 ± 47.2b | 60.23 ± 35.64bc | 7.50 ± 0.54a | 0.27 ± 0.19b | 1.5 ± .14ab | 23.18 ± 1.78a | |

| BH-BS2 | 7.8 ± 0.07a | -278.2 ± 48.1c | -171.7 ± 50.9b | 131.14 ± 8.45a | 4.45 ± 3.57a | 0.31 ± 0.28b | 1.61 ± 0.204a | 23.33 ± 1.62a | |

| 58 days (tillering stage) | TY-S0 | 6.5 ± 0.34B | 510.9 ± 33.8A | 438.3 ± 88.5A | 61.90 ± 1.10B | 26.84 ± 2.63A | 4.38 ± 1.87A | 2.02 ± 0.05B | 9.66 ± 0.05B |

| TY-S1 | 6.5 ± 0.13B | 439.8 ± 127.7A | 494.3 ± 41.6A | 63.57 ± 5.55B | 25.12 ± 0.35A | 2.03 ± 0.42AB | 2.04 ± 0.06A | 10.25 ± 0.24B | |

| TY-S2 | 6.5 ± 0.12B | 536.8 ± 10.9A | 507.3 ± 38.6A | 69.00 ± 10.23AB | 26.34 ± 2.63A | 1.85 ± 0.73AB | 2.01 ± 0.12B | 9.96 ± 0.11B | |

| TY-BS1 | 7.2 ± 0.41A | 435 ± 67A | 501.5 ± 215.7A | 81.84 ± 2.01A | 30.37 ± 4.73A | 1.30 ± 1.81B | 2.19 ± 0.09A | 13.8 ± 0.94A | |

| TY-BS2 | 7.0 ± 0.01A | 488.7 ± 33.9A | 452.7 ± 203.3A | 79.26 ± 11.7A | 30.06 ± 4.61A | 0.23 ± 0.13B | 2.18 ± 0.08A | 14.57 ± 1.39A | |

| BH-S0 | 8.4 ± 0.12b | 434.7 ± 61.5a | 423 ± 176.7a | 47.06 ± 15.71a | 33.12 ± 3.86a | 5.23 ± 1.77c | 1.12 ± 0.05c | 19.42 ± 0.56b | |

| BH-S1 | 8.4 ± 0.1b | 358.3 ± 117.3ab | 334.7 ± 181.7a | 34.73 ± 3.84a | 33.06 ± 5.14a | 7.03 ± 0.37bc | 1.41 ± 0.12ab | 17.98 ± 0.4b | |

| BH-S2 | 8.6 ± 0.07a | 205.6 ± 174.6b | 279.3 ± 140.3a | 39.91 ± 2.90a | 29.06 ± 4.07a | 11.74 ± 2.05a | 1.38 ± 0.17b | 18.17 ± 0.19b | |

| BH-BS1 | 8.7 ± 0.04a | 336.6 ± 24.2ab | 563 ± 11a | 32.91 ± 5.42a | 26.83 ± 2.09a | 6.52 ± 3.02bc | 1.42 ± 0.14ab | 23.17 ± 1.39a | |

| BH-BS2 | 8.6 ± 0.03a | 206.6 ± 132.9b | 229.7 ± 105.6a | 39.41 ± 5.57a | 29.53 ± 2.42a | 9.36 ± 1.21ab | 1.62 ± 0.08a | 22.37 ± 1.33a | |

| 120 days (heading stage) | TY-S0 | 7.1 ± 0.14C | 435.3 ± 24.6A | 318 ± 199.3B | 124.11 ± 7.62B | 43.10 ± 2.20A | 1.36 ± 2.06A | 2.04 ± 0.04BC | 9.85 ± 0.16B |

| TY-S1 | 7.2 ± 0.34BC | 380.6 ± 69.1A | 161 ± 36.7AB | 137.37 ± 25.1AB | 41.05 ± 2.73A | 0.93 ± 0.51A | 2.15 ± 0.10AB | 9.58 ± 0.13B | |

| TY-S2 | 7.2 ± 0.12BC | 352.9 ± 74.8A | 227.7 ± 17.9B | 148.29 ± 19.82A | 43.61 ± 1.30A | 0.63 ± 0.11A | 2.01 ± 0.03C | 9.69 ± 0.25B | |

| TY-BS1 | 7.5 ± 0.04AB | 446.3 ± 22.9A | 385.7 ± 112.3A | 174.01 ± 27.15A | 41.64 ± 18.14A | 0.16 ± 0.17A | 2.05 ± 0.11BC | 13.34 ± 1.19A | |

| TY-BS2 | 7.6 ± 0.19A | 437.8 ± 76.9A | 465.7 ± 206.4B | 144.46 ± 11.16A | 31.38 ± 2.56A | 0.05 ± 0.04A | 2.26 ± 0.02A | 13.79 ± 0.46A | |

| BH-S0 | 8.3 ± 0.15bc | 164.9 ± 7.9b | -10.3 ± 112b | 102.80 ± 13.49a | 32.09 ± 3.24b | 1.57 ± 1.54a | 1.1 ± 0.06b | 19.81 ± 0.35b | |

| BH-S1 | 8.5 ± 0.07a | 234.7 ± 93.6ab | 129 ± 30.8ab | 75.80 ± 10.85ab | 29.59 ± 2.63b | 0.52 ± 0.06a | 1.45 ± 0.109a | 18.46 ± 0.61b | |

| BH-S2 | 8.4 ± 0.14abc | 164.8 ± 60.8b | 186.3 ± 78.3a | 68.05 ± 12.12b | 37.34 ± 2.79a | 0.26 ± 0.23a | 1.25 ± 0.15ab | 18.93 ± 0.29b | |

| BH-BS1 | 8.5 ± 0.12ab | 321.1 ± 50.3a | 210.3 ± 58.9a | 80.33 ± 7.14ab | 40.25 ± 3.19a | 0.33 ± 0.06a | 1.49 ± 0.12a | 22.52 ± 1.85a | |

| BH-BS2 | 8.2 ± 0.05c | 251.9 ± 75.1ab | 118 ± 112.2ab | 100.94 ± 26.30a | 41.55 ± 2.31a | 1.97 ± 2.17a | 1.5 ± 0.16a | 21.81 ± 1.38a |

aTreatment: TY represents acidic Utisol from Taoyuan, BH represents alkaline Inceptisol from Binhai; control without straw and biochar (S0), with straw at low (S1) and high (S2) rate, and their counterpart plus biochar (BS1 and BS2). bMean values ± SD, n = 3. The captical letters indicate significant differences in parameters among treatments for TY soils at the individual stage, while the lowercase letters are used for BH soils, analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05). “–” means the concentration below detecting limit.

Table 2.

Repeat measures ANOVA of rice growing stages and treatments on soil properties and gases emissions.

| Soil | Items | Stage (rice growing) | Treatment | Stage × Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TY | ||||

| DOC | P < 0.001 a∗∗∗ | P = 0.005 ∗∗ | P = 0.264 ns | |

| pH | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.278 ns | |

| Eh | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | |

| P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.556 ns | P = 0.727 ns | ||

| P = 0.034 ∗ | P = 0.027 ∗ | P = 0.163 ns | ||

| TC | P = 0.409 ns | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.216 ns | |

| TN | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.018 ∗ | P = 0.028 ∗ | |

| C/N ratio | P = 0.184 ns | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.264 ns | |

| Cumulative CH4 emission | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | |

| Cumulative N2O emission | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.331 ns | |

| CH4 flux | P = 0.022 ∗ | P = 0.026 ∗ | P = 0.043 ∗ | |

| N2O flux | P = 0.011 ∗ | P = 0.240 ns | P = 0.509 ns | |

| BH | ||||

| DOC | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.037 ∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | |

| pH | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.213 ns | P = 0.004 ∗∗ | |

| Eh | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | |

| P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.414 ns | P = 0.801 ns | ||

| P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.014 ∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | ||

| TC | P = 0.255 ns | P = 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.354 ns | |

| TN | P = 0.175 ns | P = 0.013 ∗ | P = 0.074 ns | |

| C/N ratio | P = 0.543 ns | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.470 ns | |

| Cumulative CH4 emission | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | |

| Cumulative N2O emission | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P = 0.249 ns | P = 0.005 ∗∗ | |

| CH4 flux | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | P < 0.001 ∗∗∗ | |

| N2O flux | P = 0.008 ∗∗ | P = 0.593 ns | P = 0.424 ns |

a∗∗∗For the effect, ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗ denote significant difference at P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively. The ns means no significant difference.

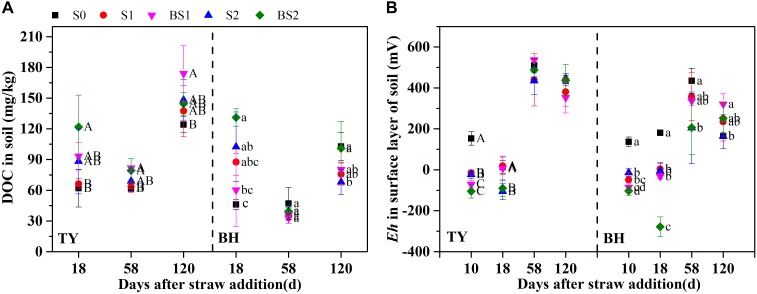

Similar trends of soil DOC variation were found in both soils (Figure 1A). Soil DOC was greatly increased after straw addition during the seedling stage, while it decreased at the tillering stage. Soil DOC was also increased by the biochar amendment over all rice growth stages, when compared with that in control, except for a decrease at the tillering and heading stages in the BH soil (Figure 1A), which might have been caused by adsorption on the biochar. The dynamics of soil redox potential (Eh) was generally consistent in the two paddy soils (Figure 1B). The Eh was generally low during the flooding period, and sharply increased through the drainage. Straw incorporation reduced the Eh in both soils during the flooding stage, which ranged from −104.7 to −15.2 mV in the TY soil, and from −103.6 to −13.7 mV in the BH soil. A lower Eh in both soils was recorded at the seedling stage with biochar amendment, which was nearly 36–272 mV lower than treatments without biochar incorporation (S1 and S2) (Figure 1B). Moreover, the difference in Eh between the treatments with and without biochar amendment became smaller following drainage.

FIGURE 1.

Soil dissolved organic carbon contents (A) and redox potential in surface layer of paddy soil (B) among the treatments during rice growing season in 2016. Error bars present standard deviation of means (n = 3). The different letters (capital letter for the TY soil and lowercase for the BH soil) indicate significant difference among treatments at each stage, which is analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05).

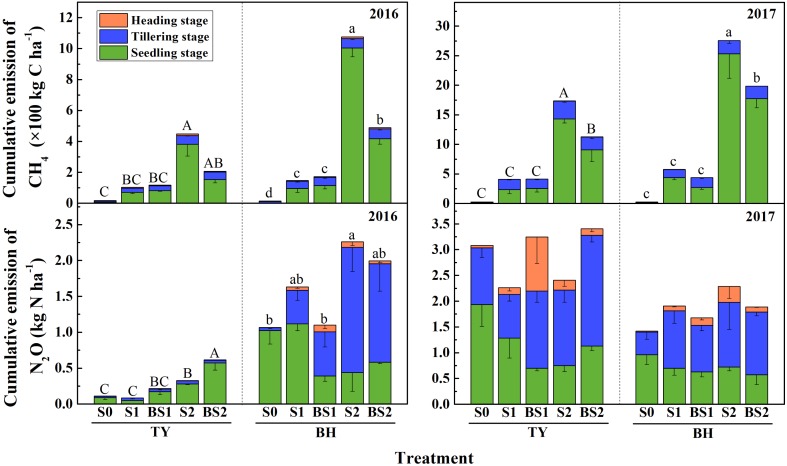

CH4 Emissions From Rice Paddy Soils

The methane fluxes showed significant differences among treatments and varied over the rice growing season (Supplementary Figure 1). In general, the transient and cumulative CH4 emissions in the TY soil were much lower than those in the BH soil. During the rice growing season in 2016, CH4 emissions were more concentrated in the seedling stage in both soils (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1), which accounted for 64.5–93.4% of cumulative methane emissions in all treatments except the control (S0) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative emissions of CH4 and N2O over the rice growing season in 2016 and 2017. Colors in column denote different stage: the seedling stage in green, the tillering stage in blue and the heading stage in orange. Error bars present standard deviation of means (n = 3). The different letters (capital letter for the TY soil and lowercase for the BH soil) among different treatments indicate significant difference of the cumulative emissions during the whole rice growing season, which was analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05).

CH4 emissions significantly increased in both soils with straw addition (P < 0.01), and the response in the high straw rate (S2) was greater than in the low straw rate (S1) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). The S2 treatment had the highest cumulative CH4 emissions among all the treatments with 448 kg C ha−1 in TY and 1,075 kg C ha−1 in BH in 2016. In contrast, the cumulative CH4 emissions significantly decreased to 207 kg C ha−1 in the TY soil and 489 kg C ha−1 in the BH soil under biochar amendment at the high straw input level (BS2) (P < 0.05). However, no significant difference in cumulative CH4 emissions was detected between with and without biochar amendment at the low straw input level, i.e., S1 and BS1 (Figure 2). Furthermore, the data of CH4 emissions collected in the rice growing season in 2017 were highly consistent with that in 2016, showing a significant increase by rice straw addition and a significant suppression by biochar amendment in the high straw incorporated soils (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1, P < 0.05).

N2O Emissions From Rice Paddy Soils

A similar trend of N2O flux among all the treatments was observed in the two soils during the rice growing season. For both soils in the 2016 rice growth season, the N2O flux was pronounced at the start of the continuously flooding period, and quickly decreased within a week (Supplementary Figure 2a). No marked variation was found in the following drainage and re-flooding periods, except for a peak flux in the BH soil at the 55th day, which might be due to the alternation of the water regime caused by a rainfall event.

Generally, the N2O flux in the TY soil was slightly lower than that in the BH soil in 2016 (Supplementary Figure 2a). During the whole rice growing season in 2016, cumulative N2O emissions in the TY soil were significantly lower than those in the BH soil (Figure 2). For the TY soil, nearly 55.4–92.8% of the cumulative N2O was emitted at the seedling stage. Moreover, the cumulative N2O emissions significantly increased with straw addition in treatment S2 by 1.94-fold (P < 0.05), while little effect was seen in treatment S1. The cumulative N2O emissions increased by 0.88- to 1.51-fold with biochar addition, compared with no biochar incorporation (Figure 2). For the BH soil, 91.2–99.8% of the cumulative N2O emissions originated at the seedling and tillering stages. The cumulative N2O emissions in S2 treatment was significantly higher than that in control (S0, P < 0.05), while a decreasing trend was observed with biochar amendment in treatment BS2 (Figure 2). For both TY and BH soil, N2O emissions showed no significant difference among treatments in the year 2017 (Supplementary Figure 2b).

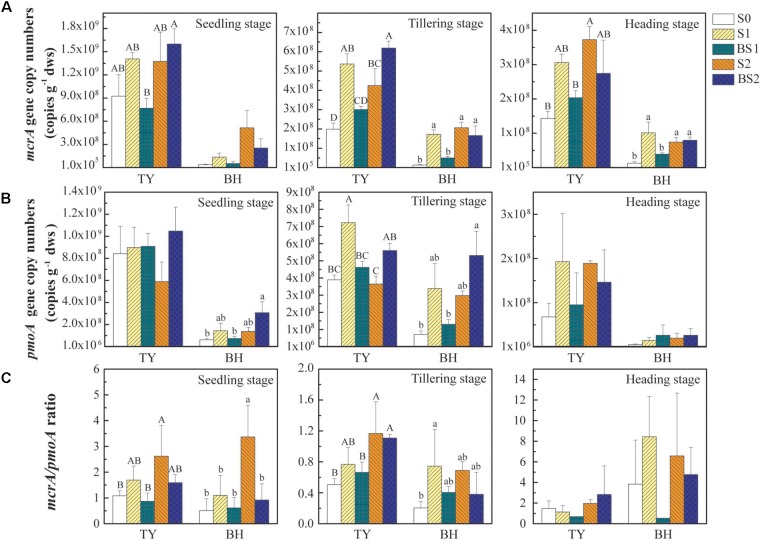

Abundances of Methanogens and Methanotrophs in Rice Paddy Soils

The abundances of mcrA and pmoA genes, encoding the key enzymes functioning in the generation of CH4 and the consumption of CH4, respectively, were quantified to estimate the dynamics of methanogens and methanotrophs during the rice growing season. Generally, both mcrA and pmoA genes were more abundant in the TY soil (ranged from 1.43 × 108 to 1.60 × 109 copy genes g−1 dws for mcrA, and from 6.79 × 107 to 1.05 × 109 copy genes g−1 dws for pmoA) than those in the BH soil (ranged from 1.27 × 107 to 5.15 × 108 copy genes g−1 dws for mcrA and from 5.05 × 106 to 3.38 × 108 copy genes g−1 dws for pmoA), and decreased over time in both soils (Figures 3A,B). The mcrA gene abundance generally increased with straw addition alone (S1 and S2) and high straw level plus biochar (BS2), and showed statistically significant differences at tillering and heading stages for both soil types (Figure 3A, P < 0.05). Interestingly, the mcrA gene abundance in biochar amendment under low straw input (BS1) showed no significant difference with control (S0), but was generally lower than S1 treatment (Figure 3A, P < 0.05), which could be due to the suppressive influence of the biochar amendment under low straw input.

FIGURE 3.

The abundance of mcrA (A) and pmoA (B) genes and the mcrA/pmoA ratio (C) at the seedling, tillering, and heading stages in 2016. Error bars present standard deviations of means (n = 3). The different letters (capital letter for the TY soil and lowercase for the BH soil) indicate significant difference among different treatments at each sampling point, which was analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05).

Compared with the control (S0), straw addition at low and high rates (S1 and S2) showed no significant promotion or suppression effects on the pmoA gene abundances in both TY and BH soils, except that pmoA gene abundance was significantly higher in S1 than in S0 at tillering in the TY soil (Figure 3B). By contrast, biochar amendment under high straw input (BS2) showed a visible promotion on the pmoA gene abundance in both TY and BH soils at seedling and tillering stage, when compared with S0 and S2 treatments. A distinct augment of pmoA gene abundance by 53.3–123.9% was observed in the BS2 treatment at the seedling and tillering stages, when compared with S2 in both soils (Figure 3B). Consequently, biochar plus straw amendment (BS1 and BS2) generally decreased the ratio of mcrA to pmoA gene abundance in comparison with straw addition alone (S1 and S2) (Figure 3C).

Correlation analysis showed that mcrA gene abundance was positively correlated with the CH4 flux (r = 0.514, P < 0.01 for the TY soil, r = 0.730, P < 0.01 for the BH soil), while negatively correlated with soil pH and Eh in both soils (Supplementary Table 2). The pmoA gene abundance showed no significant correlation with the CH4 flux in both soils, but was negatively correlated with Eh (r = −0.665, P < 0.01) was observed in the TY soil, but not in the BH soil (Supplementary Table 2). Otherwise, the ratio of mcrA to pmoA gene abundance was positively correlated with the cumulative CH4 emission (r = 0.476, P < 0.01 for the TY soil, r = 0.299, P < 0.05 for the BH soil (Supplementary Table 2). All these suggested that the mcrA gene abundance, compared with pmoA gene abundance, was more closely related to the dynamics of CH4 flux, and the ratio of mcrA to pmoA gene abundance also could be a good indicator for CH4 flux.

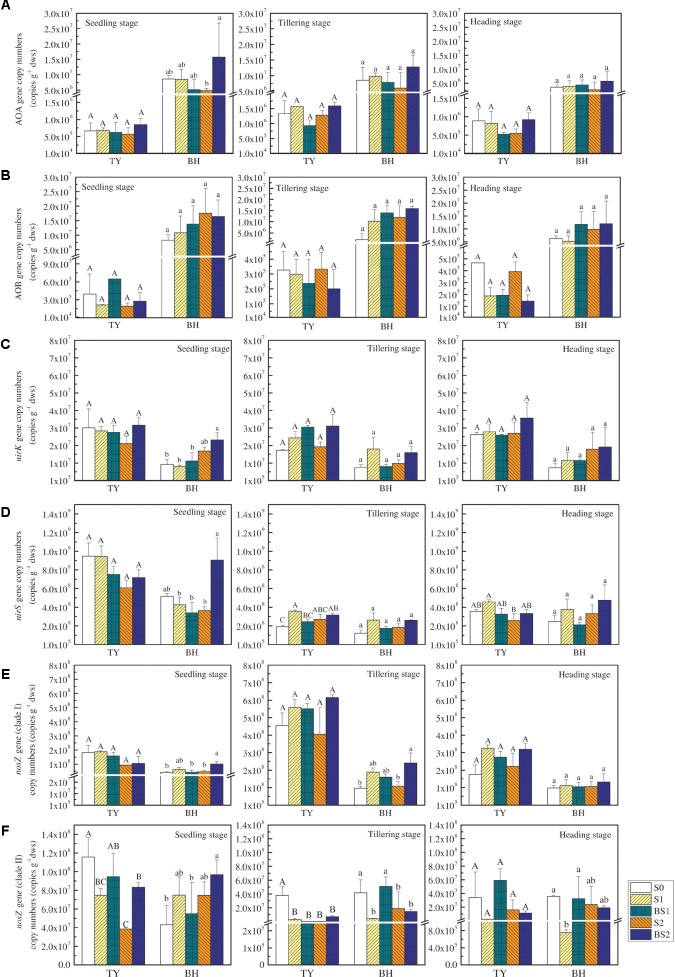

Abundances of N2O-Related Functional Genes

The functional genes relevant to the N2O production and consumption were analyzed in this study (Figure 4). The abundance of ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and bacteria (AOB) amoA genes were both lower in the TY soil (ranged from 5.29 × 105 to 1.59 × 106 copy genes g−1 dws for AOA and from 1.44 × 105 to 6.48 × 105 copy genes g−1 dws for AOB) compared with that in the BH soil (ranged from 2.65 × 106 to 1.57 × 107 copy genes g−1 dws for AOA and from 2.03 × 106 to 1.75 × 107 copy genes g−1 dws for AOB), with slight change over the crop growth stages (Figures 4A,B). Besides, no significant variations of AOA and AOB amoA gene abundances were observed among all the treatments regardless of rice growth stage in both soils, except for a significant promotion of AOA abundance in the BS2 treatment at the seedling stage in the BH soil (Figures 4A,B). Generally, both straw addition and biochar incorporation (S1, S2, BS1, and BS2) had little impact on AOA and AOB amoA gene abundances for both soil types over time, when compared with the control (S0).

FIGURE 4.

The abundance of N2O-related functional genes at the seedling, tillering and heading stages in 2016. The copy numbers of archaeal amoA, bacteria amoA, nirK, nirS, nosZ I, and nosZ II genes are exhibited in (A–F), respectively. Error bars present standard deviations of means (n = 3). The different letters (capital letter for the TY soil and lowercase for the BH soil) indicate significant difference among different treatments at each sampling point, which was analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05).

Similarly, straw addition and biochar application showed little effect on the nirK gene abundance, except for a significant increase by 1.51-fold in BS2 treatments in the BH soil at the seedling stage (P < 0.05), when compared with the control (S0) (Figure 4C). In general, the abundance of the nirS gene (ranged from 1.22 × 108 to 9.48 × 108 copy genes g−1 dws) was much greater than that of nirK gene (ranged from 7.28 × 106 to 3.28 × 107 copy genes g−1 dws) (P < 0.01). Straw addition alone (S1, S2) or biochar amendment (BS1, BS2) had little effect on the nirS gene abundance compared with the control (S0) for both soils over time, except for significant increases by 87.6% and 65.8% under the treatments S1 and BS2 in the TY soil at the tillering stage, respectively (Figure 4D, P < 0.05).

The nosZ gene, as an index of the nitrous oxide-reducing bacteria, consisted of two distinct clades (clade I and clade II). The abundance of nosZ clade I was higher in both soils at tillering compared to the seedling stage, followed by a decrease at the heading stage (Figure 4E). Straw addition alone (S1, S2) had no significant effect on the abundance of the nosZ I gene for both TY and BH soils. Biochar amendment (BS1, BS2) showed no obvious influence on the nosZ I gene abundance in the TY soil, while BS2 treatment significantly increased the nosZ I gene abundance in the BH soil at the seedling and tillering stages (Figure 4E, P < 0.05), during which N2O emissions peaked. The enhanced nosZ I gene abundance could be responsible for the suppression of N2O emissions in BH soil. The abundance of nosZ II gene showed slight variation over time, and generally decreased in straw addition treatments (S1 and S2) in relative to S0 in both soils (Figure 4F). Biochar amendment under low straw addition (BS1) significantly buffered the straw-induced decrease of nosZ II gene in the BH soil at tillering and heading stages, but showed no significant effect in the TY soil, which further explained the suppression of N2O emissions in BH soil.

Community Similarity of the Methanotroph and N2O-Reducing Bacteria

The methanotroph community at seedling stage and nosZ gene containers community at seedling, tillering and heading stages were characterized by Miseq sequencing. After resampling, 5,689 pmoA gene reads and 8,356 nosZ gene reads from each sample were selected for alpha- and beta-diversity analysis. Alpha diversity of both methanotroph and nosZ-containing bacteria showed no significant differences among treatments in both soils. However, the alpha diversity of nosZ-containing bacteria was generally much higher in the BH soil than in the TY soil (Supplementary Table 3, P < 0.05).

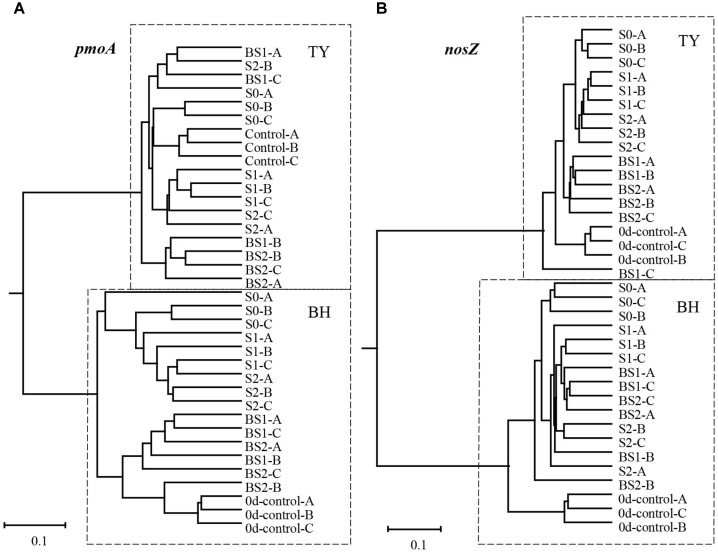

The UPGMA clustering analysis for the beta-diversity of methanotroph and nosZ gene container communities at the seedling stage showed a clear separation between the two soil types (Figure 5). Within each soil type, samples generally clustered among treatments, with clear separation between treatments with and without biochar amendment for methanotroph community in the BH soil, and for nosZ gene container in the TY soil (Figure 5). These results suggested that community structure of methanotroph and nosZ gene containing denitrifiers were largely influenced by the addition of biochar than that of the straw, depending on the soil type.

FIGURE 5.

UPGMA dendrogram contrasted from Bray–Curtis distance matrix of pmoA (A) and nosZ I (B) gene sequences at day 18 during the seedling stage. 0d-control represents the background of original soil at the beginning of pot experiment, and A, B, C mean three replicate pots.

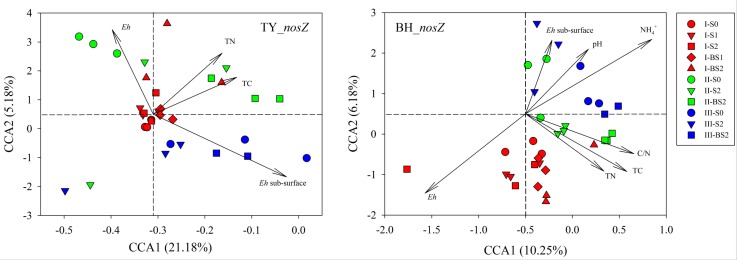

Canonical correlation analysis based on the OTU matrix was performed to examine the influence of soil environmental factors on the community composition of nosZ gene containing denitrifiers. On the CCA plots, well separation of nosZ gene community among the three rice growth stages but slight aggregation among treatments were observed (Figure 6). The x-axis explained 21.18% and 10.25% of the variation of nosZ gene community in TY and BH soils, and the y-axis explained 5.18% and 6.18% of variation, respectively. Monte Carlo tests showed that Eh, TN and TC were factors significantly influencing nosZ gene containing community in the TY soil, and together explained the variation by 11.85%. For the BH soil, Eh, TC, TN, C/N, pH and significantly influenced nosZ gene containing community and together explained 24.05% of variation (Figure 6). For both soils, Eh generally accounted for the greatest impact on nosZ gene containing community (Supplementary Table 4).

FIGURE 6.

Canonical correlation analysis for the nosZ gene containing denitrifier communities and soil properties. Three rice growth stages, seedling, tillering and heading, were included and labeled as I (red), II (green) and III (blue), respectively.

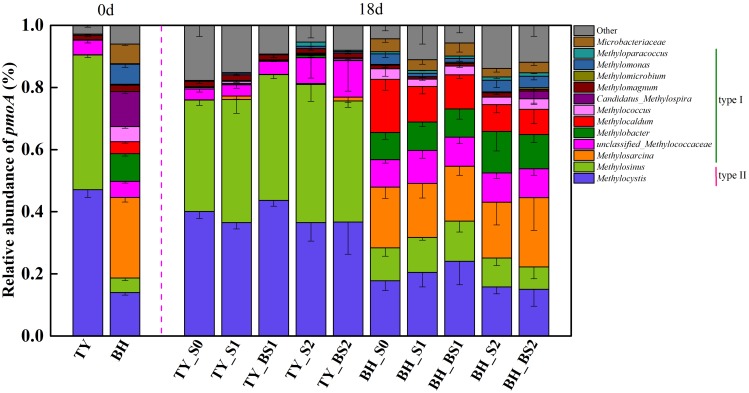

Community Composition of Methanotroph and N2O-Reducing Bacteria Under Different Treatments

Analysis of methanotroph communities based on pmoA gene further showed that the TY soil and the BH soil possessed different methanotroph communities, with the TY soil dominated by Type II methanotrophs and the BH soil by type I methanotrophs (Figure 7). For the TY soil, Methylocystis (36.53–47.09%) and Methylosinus (38.93–44.46%) of Alphaproteobacteria (type II) were the dominant group and showed no marked variations among the five treatments, while the proportion of unclassified_Methylococcaceae belonging to type I increased from 3.54% in control (S0) to 8.27% in S2 and 11.78% in BS2 treatment, respectively. For BH soil, type II methanotrophs (Methylocystis and Methylosinus) accounted for 25.08–37.01% of the methanotroph community and type I methanotrophs accounted for 53.13–63.55%, with 3.93–13.67% of unclassified among the five treatments in day 18 (Figure 7). Compared with the S0, S1, and BS1 treatments, the proportion of type II methanotrophs decreased by 14.7–40.12% while the proportion of Methylobacter (type I methanotroph) significantly increased by 21.30–53.13% with the high straw incorporation (S2 and BS2). Straw addition and biochar amendment (S1, S2, BS1, and BS2) both decreased the relative abundance of Methylocaldum by 33.26–52.61% compared with the control (S0). Besides, a distinct increased (by 14.03%) of Methylosarcina was observed in the BS2 treatment with biochar amendment at high straw input. All these suggested that methanotrophs community responded to straw and biochar amendments more greatly in the BH soil than in the TY soil, coinciding with the separation of methanotrophs among the treatments in the UPGMA dendrogram.

FIGURE 7.

Taxonomic distribution of pmoA-based methanotrophs at the genus level at day 18 during the seedling stage. Other includes the sequences with a relative abundance less than 0.9% and the unclassified sequences at genus level. Mean ± SD, n = 3. 0d represents the original soil used in this experiment.

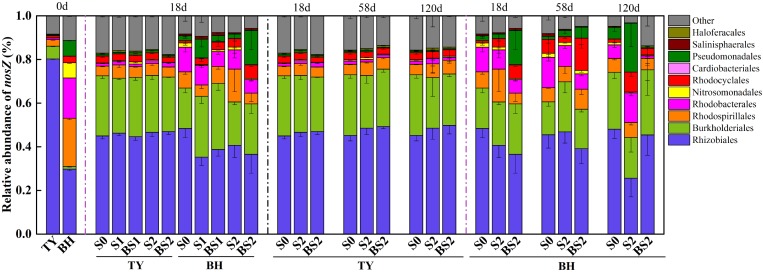

As for typical nosZ genes, 1,362 OTUs at 97% similarity level were identified from 72 samples covering all treatments at seedling stage, and S0, S2, and BS2 treatments over three rice growth stages. The majority of nosZ gene reads were grouped into Proteobacteria (89.7%), with 3.48–18.05% unclassified (Figure 8). At the order level, the nosZ gene community was predominated by Rhizobiales in the TY soil with a proportion of 80.27%, while it was dominated by Rhizobiales, Rhodospirillales, and Rhodobacterales with similar proportions between 18.47% and 29.76% in the BH soil at day 0 (Figure 8). Flooding changed the nosZ gene community with Rhizobiales significantly decreasing from 80.27 to 44.61–46.98% in the TY soil, Rhodospirillales decreasing from 22.09 to 4.87–15.04% in the BH soil, and Burkholderiales increasing from 1.20–5.85% to 18.55–30.32% in both soils. After flooding, the nosZ gene containing denitrifiers showed no significant variation among all the treatments over the time in the TY soil (Figure 8). In contrast, the nosZ gene containing denitrifiers community in the BH soil showed visible variations among different straw and biochar treatments and greater variation over the three rice growth stages. Within treatments at day 18 (seedling stage), the proportion of Burkholderiales significantly increased by 6.78–50.28% in the straw addition alone treatment (S1 and S2), and 24.53–63.43% in the biochar amendment treatments (BS1 and BS2) compared with the control (S0) (Figure 8) in the BH soil. Compared with the S0 treatment, S2 treatment had a higher proportion of Pseudomonadales and Rhodobacterales but a relatively low proportion of Rhizobiales at day 120 (heading stage), while the proportions of these groups in BS2 treatment were closer to that in S0 treatment (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Taxonomic distribution of nosZ I gene derived OTUs at the order level in paddy soils over time. Other includes the sequences with a relative abundance less than 0.8% and the unclassified sequences. Mean ± SD, n = 3. 0d represents the original soil used in this experiment.

Discussion

Effect of Straw Addition and Biochar Incorporation on CH4 Emissions

In this study, the transient CH4 and N2O fluxes showed quite similar patterns between the two different soil types. Both the CH4 flux and cumulative emissions peaked at the early rice growth period (seedling stage), and a significant increase in cumulative CH4 emissions induced by the rice straw amendment and a greater increase with high straw rate input (S2 treatment) were observed (Figure 2). Correspondingly, a significantly higher DOC in the S2 treatment than in the S0 and S1 treatments (no straw and low straw rate) were detected in the early rice growth period (Table 1), indicating that more straw-driven C was probably transforming into CH4 at the seedling stage. As suggested by previous studies, the increase of CH4 emissions could be attributed to the additional substrate (e.g., H2/CO2 and acetate) provided for the methanogens via anaerobic decomposition of crop residues (Watanabe et al., 1995, 1998; Ma et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2016). The amounts of straw used in this study were equal (S1) and double (S2) to all aboveground biomass return, and the high straw level (S2) was set to stimulate the straw concentrated patches in field, as straw is generally surface returned to the field or incorporated into the plow layer by plowing thus cause highly concentrated patches. The similar case that the higher straw amount induced higher CH4 and N2O emissions observed in our pot experiments probably occurred in the field, so the amount of straw return to field should be taken into consideration in practice, even though biochar amendment could markedly mitigate the CH4 emissions in straw incorporated soils.

On the other hand, soil Eh was extremely low in the BH soil (−104 to −14 mV in surface and −190 to −156 mV in subsurface) and the TY soil (−105 to −15 mV in surface and −165 to −146 mV in subsurface) 1 week after straw input (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 3), and significantly negative correlations were observed between soil Eh and CH4 fluxes in both soils (Supplementary Table 2). This is consistent with previous studies which showed that soil Eh ranging from −230 to −150 mV greatly favored CH4 emissions (Wang et al., 1993). Moreover, the soil Eh decrease was considered as another main reason of the enhanced CH4 emissions after rice straw amendment, as more electron donors were provided for methanogen process under low Eh conditions (Tanji et al., 2003; Ma et al., 2008; Shen et al., 2014). Soil Eh therefore could be a sensitive indicator for CH4 emission forecasting under flooded conditions.

By contrast, biochar amendment significantly decreased the CH4 emissions under the high straw rate during the whole rice growing season in this study. Though sporadic studies found that biochar amendment increased CH4 emissions in paddy fields (Knoblauch et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012), the majority of previous studies have shown that single biochar application could decrease CH4 emissions effectively, and this was attributed to the increased soil pH induced by biochar (Tanji et al., 2003; Conrad and Klose, 2006; Liu et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2014; Ly et al., 2015; Thammasom et al., 2016). In this study, a significant pH increase by 0.5 unit with biochar amendment (BS2) was also observed in the acidic TY soil at the early period (at day 18 and day 58), which partially accounted for the decreased CH4 emissions under biochar amendment with high straw input (Table 1). However, biochar amendment did not significantly increase pH in the BH soil at both straw input levels (Table 1), probably due to the alkaline property of the BH soil. Biochar-induced pH increase therefore could not explain the decreased CH4 emissions in the BS2 treatment in the BH soil. Moreover, though biochar amendment with straw incorporation markedly decreased soil Eh for both soil types, while CH4 emissions did not increase with decreasing Eh as observed in the straw incorporation treatments (S1 and S2). Biochar contains electroactive functional groups such as quinone/hydroquinone and has been shown to serve as electron acceptors or donors during the redox processes (Kluepfel et al., 2014). It is also proposed as a “geoconductor” which could directly transfer electrons from char matrices to minerals (Sun et al., 2017). The depressed CH4 emissions from biochar amended soil under high straw incorporation in this study therefore could be explained as a result of biochar competing for electrons with CO2 thus disturbing the methanogenesis process. This also explained why the depression of biochar on CH4 emissions was only obvious under high straw but not under low straw inputs, as the high straw input created a stronger redox condition (much lower Eh in BS2 than BS1, Table 1) and biochar could trap more electrons. All these suggest that biochar amendment together with straw incorporation is beneficial to mitigating CH4 emissions from paddy soils, especially under high straw input conditions.

On the other hand, CH4 emissions from soil are dependent on the balance of microbe-mediated methanogenesis and methane oxidation processes. Methane produced via methanogenesis under anaerobic conditions could be consumed by the methanotrophic bacteria via oxidizing CH4 to CO2, when O2 was available (Bridgham et al., 2013). Some previous studies showed that straw incorporation enhanced CH4 emissions with an increase in the abundance of the mcrA gene (Freitag et al., 2010; Cai et al., 2017). Consistently, straw addition generally increased the abundance of the mcrA gene, but showed no significant effect on the abundance of the pmoA gene in this study (Figures 3A,B). As a consequence, the mcrA/pmoA gene abundance ratio increased with straw incorporation, and both the ratio and the mcrA gene abundance were positively correlated with CH4 emissions in both soils (Supplementary Table 2), which could be attributed to the stimulation of straw degradation and high available DOC for methanogens (Figure 2 and Table 1). Biochar amendments under high straw input (BS2) showed no clear effect on the mcrA gene abundance but promoted the pmoA gene abundance, and consequently decreased the ratio of mcrA/pmoA significantly in both soils, when compared with that of S2 (Figure 3C). Therefore, it was the activated methanotrophs and the attenuated ratio of mcrA/pmoA that lead to the suppressed CH4 emissions after biochar amendment at high straw incorporation.

Effect of Straw Addition and Biochar Incorporation on N2O Emissions

For both TY and BH soils, straw amendment at the low rate (S1) caused no significant increase in N2O emissions while the cumulative N2O emissions increased significantly with straw addition at the high rate (S2) in this study (Figure 2). Ambiguous effects of straw amendment on N2O emissions in paddy soils had been found in previous studies. For example, Ma et al. (2007) found that the N2O emissions decreased by approximately 30% with straw incorporation, while significant N2O emissions increased with straw addition was observed in other studies (Ma et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2016). The different effects of straw application on N2O emissions were mainly due to the quality of the crop residues with various C/N ratios (Toma and Hatano, 2007). Incorporating crop residue with a high C/N ratio (>40) (like wheat straw) could enhance microbial N immobilization, which results in less available N for nitrification and denitrification (Vigil and Kissel, 1991; Millar and Baggs, 2005; Toma and Hatano, 2007; Rizhiya et al., 2011). In contrast, a lower C/N ratio of straw (like soybean stem, cabbage, and red clover) would provide more available N for denitrifiers and thus result in increased N2O emissions (Baruah et al., 2016). Moreover, a negative correlation was detected between the N2O emissions from crop residue incorporated soil and straw C/N ratio (Millar and Baggs, 2005), suggesting that the C/N ratio of incorporated straw might be a key factor influencing the N-cycling in paddy soils. In this study, no visible increase in N2O emissions was observed under low straw input rate, and significantly higher N2O emissions under high straw input rate were only observed in 2016, but not in 2017. The high C/N ratio at about 38 in the rice straw used in this study well explained the non-significant increase in N2O emissions under low and high straw input in most cases. The higher N2O emissions in S2 than in S0 treatment in 2016 could be attributed to the additional C and N substrate via straw decomposition under high straw input rate, while the effect of straw on N2O emissions would be limited in the tested soils.

The cumulative N2O emissions in biochar amendment treatments (BS1 and BS2) showed a decreasing trend in the alkaline BH soil. Conversely, N2O emissions in BS1 and BS2 in the TY soil showed an increasing trend for two growth seasons and were statistically significant higher compared with straw incorporation treatments (S1 and S2) in 2016. Similarly, some previous studies reported that soil N2O emissions decreased significantly following biochar amendment (Liu et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2012; Saarnio et al., 2013), while some others showed a significant increase of N2O emissions after biochar inputs (Verhoeven and Six, 2014). The inconsistent effect of biochar amendment on N2O emissions might be explained by the soil properties (Cayuela et al., 2014). The above mentioned studies attributed the reduced N2O emissions in the paddy fields with biochar amendment to soil aeration improvement after biochar application and the decrease of availability due to the absorption by biochar (Lehmann et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2010). These reasons could well explain the decreasing trend of N2O emissions in biochar treatment in the BH soil in this study, but not for the TY soil with a converse trend. Some studies also suggested that the increase of soil pH in biochar-treated soils could enhance the activity of N2O reductase within denitrifier microorganisms, and thus reducing the ratio of N2O/N2 (Yanai et al., 2007). Though soil pH increased significantly by more than 0.5 units in the TY soil under biochar amendments, biochar application did not decrease N2O emissions but promoted N2O emissions to some extent in this study. The possible explanation for such inconsistency could be: The TY soil contained much higher ammonia concentration (52.91 mg kg−1 in BS1 and 45.61 mg kg−1 in BS2) than the BH soil (7.50 mg kg−1 in BS1 and 4.45 mg kg−1 in BS2). The increased soil pH induced by biochar probably stimulated the nitrification and denitrification under such high ammonia condition, thus induced N2O emissions in the TY soil. Some studies also suggested that biochar-induced increase of or -N content was the main reason for the increased N2O emissions (Yoo and Kang, 2012; Shen et al., 2014). Differently, our study did not observe significant increase -N content induced by pH improve in the TY soil with biochar amendment, as the high -N background probably buffered it. These observations suggested that biochar-induced pH increase would not necessarily decrease N2O emissions, but might increase N2O emissions conversely when available N is high in soil environment. As biochar amendment might produce inconsistent effect on N2O emissions in different soils, its extensive application requires appropriate estimation based on soil property.

A previous study found that the increased N2O emissions were closely related with the significant increase in AOB abundance after biochar amendment in a paddy soil (Lin et al., 2017). However, in present study, no significant effects of straw and biochar addition on the abundances of AOA and AOB amoA genes were found during the rice growth stages (Figure 4), suggesting that nitrification was probably not the main process influencing the N2O emissions in both soils. Meanwhile, straw addition showed little effect on the nirK, nirS, and nosZ I genes abundances, but showed depressive effect on nosZ II gene abundance in both soils. Previous studies have indicated that the nosZ II gene-containing denitrifier had higher affinity to N2O than the nosZ I gene container and might be more responsible for the mitigation of N2O emission (Jones et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2016). The depression of nosZ II gene by straw addition in two soils partially explained the higher N2O emissions in S1 and S2 treatment in relative to the control (S0). On the contrary, biochar amendment under high straw input significantly increased the nirS and nosZ I gene copy numbers, and biochar amendment under low straw input showed promotive effect on nosZ II gene in the BH soil (Figure 4). The increased nosZ gene abundance probably stimulated the transformation process from N2O to N2, and thus decreased N2O emissions in the BH soil with biochar amendment. As the functional genes were quantified at DNA level and multiple genes were involved in the processes of N2O production and consumption, the targeted genes and DNA-based analysis in this study might not sensitively indicate the microbial activity in N-cycling in this study. Further studies at RNA level and based on more functional genes like fungal, archaeal nirK and non-typical nosZ genes were necessary to reveal the microbial mechanism of N2O emissions under straw and biochar amendments in future.

Effects of Straw and Biochar Addition on Functional Microbial Community

Generally, distinct dominant methanotrophs and nosZ-containing denitrifiers groups were found in the TY and BH soil. Particularly, type II methanotrophic groups (i.e., Methylocystis and Methylosinus) dominated in the TY soil, while the type I methanotrophs (i.e., Methylosarcina, Methylobacter and Methylocaldum) dominated in the BH soils (Figure 7). It has been suggested that both type I and type II were active methanotroph groups in different paddy soils, and that their distributions were mainly determined by the property of original soil types (Kolb et al., 2003; Ho et al., 2011, 2015). Generally, the type I methanotrophs possessed a lower affinity with CH4 therefore preferred the condition with lower O2 and high CH4 concentrations, while the type II methanotrophs were more active in low CH4 concentration environments (Dunfield et al., 1999; Macalady et al., 2002). Type I methanotrophs were also interpreted as r-type life strategy which could respond fast to environment change and devote to the oxidation of CH4, while the type II were described as K-type life strategy possessing high competition ability under low nutrient conditions (Steenbergh et al., 2010). These characteristics well explained why straw addition resulted in a distinct shift of methanotrophs community in the BH soil but posed little effect in the TY soil in this study, as the BH soil and TY soil were dominated by type I and type II methanotrophs, respectively.

Specifically, the relative abundance of type I Methylobacter increased significantly in all straw addition treatments (S1, S2, BS1, and BS2) in the BH soil, corresponding to the significant decrease of nitrate in these treatments (Figure 7 and Table 1). It has been found that the activities of Methylobacter can be strongly suppressed by extra and supply (King and Schnell, 1994). Markedly decreased under straw incorporation treatments might relieve the suppression of nitrate and promoted the growth of Methylobacter, which well explained the enhanced proportion of Methylobacter under straw amendment condition.

On the other hand, biochar amendment in the high straw input treatment (BS2) greatly changed the community composition of methanotrophs, with Methylosarcina significantly increased (Figure 7). It has been reported that Methylosarcina and Methylomonas possibly required a certain O2 and relatively higher concentration of CH4 for methane oxidation (Lee et al., 2014). DNA-SIP experiment also demonstrated that Methylosarcina dominated under high CH4 conditions (Zheng et al., 2014). As biochar could adsorb O2 or CH4, thus creating high-CH4 hotspots (Brassard et al., 2016), which might contribute to the increased proportions of Methylosarcina in BS2 treatment. Moreover, significantly higher DOC and TN were detected in the BS2 treatment in this study (Table 1), which might contribute to the variation of methanotrophs community. Indirectly, the huge surface area and pores in biochar could provide habitats for microbial activities (Gul et al., 2015). All these difference in soil conditions induced by biochar amendment resulted in the change of methanotrophs community.

Similar to methanotrophs community, the community structure of nosZ gene containing bacteria responded to straw and biochar inputs differently in two soil types. For the TY soil, straw addition and biochar amendment showed little effect on the community composition of nosZ gene communities (Figure 8). Though straw and biochar additions significantly increased soil DOC, Eh in the subsurface of the TY soil was identified as the most significant environmental factor contributing to the shift of community structure in the TY soil in RDA analysis (Figure 6). Similarly, Richardson et al. (2009) found that denitrifiers containing nosZ gene were impressible to the dynamics of soil Eh. Contrastingly, the nosZ gene containing bacteria in the BH soil showed visible variations among different straw and biochar treatments. The relative abundances of Rhizobiales and Nitrosomonadales were obviously decreased, while Rhodocyclales and Burkholderiales were increased under straw incorporation in comparison with control. Biochar application (BS1 and BS2) further enhanced the relative abundance of Burkholderiales, when compared with the straw input alone treatment (S1 and S2). In a DNA-SIP microcosm experiment, Burkholderiales and Rhodospirllales were identified as the predominant population under suitable N2O reduction conditions, and were responsible for reduction of N2O in rice paddy soils (Ishii et al., 2011). Another study also found that denitrifiers belonging to the orders of Burkholderiales and Rhodocyclales showed strong denitrifying activities in paddy soils (Ishii et al., 2009). The enhanced proportion of Burkholderiales and Rhodocyclales with biochar amendment might contribute to a more intensive N2O consumption, thus led to the decreased N2O emissions under biochar amendment in the BH soil.

Conclusion

2-year pot experiment in this study demonstrated that the rice straw amendment could significantly increase the cumulative CH4 emissions in an acidic Utisol (TY) and an alkaline Inceptisol (BH) paddy soil, while biochar amendment could markedly mitigate the CH4 emissions augmented by high straw incorporation in both soil types. These results could be explained by the straw-driven C and N substrate change, biochar-induced pH and Eh change, or electron competition etc., depending on the physiochemical characteristics of original soil type. Straw addition at high rate caused significant increase in N2O emissions in both soils, while biochar amendment could decrease N2O emissions in the BH soil but caused converse effect in the TY soil. The abundance of mcrA and pmoA genes related to the production and consumption of CH4 changed in response to straw and biochar amendments well explained the variation of CH4 emissions among the treatments. Straw and biochar amendment induced visible community change in methanotrophs and nosZ gene containing denitrifier in the alkaline BH soil, but slight change in the acidic TY soil. The BH soil and the TY soil possessed distinct microbial community, and straw and biochar amendments caused differentiated effect on soil property of two soil types, which together explained the interactive effect of straw plus biochar application on CH4 and N2O emissions in two contrasting paddy soils. Our pot experiment suggested that biochar amendment could effectively mitigate CH4 and N2O emissions risks induced by straw application in the tested soil types, while its extensive application into different soil types requires appropriate estimation based on soil physicochemical and microbial properties, and the amount of straw return should be taken into consideration in term of gross GHG emissions.

Author Contributions

Y-QW was responsible to most of the pot experiments, laboratorial works, data processing, and article writing. RB had an important contribution to gas collecting, sampling, and some laboratorial activities. HJD provided essential helps for the article writing and revision. L-YM paid great efforts on the setup of pot experiments, and contributed to the gas and soil samplings. BH contributed to the bioinformatics analysis of sequencing data. J-ZH provided essential ideas to the experimental design and article writing. L-MZ provided essential ideas to the experimental design and paper writing, guidance for the experiments, and was responsible for pot experiments setup, article writing and revising.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Phillip Chalk for language polishing for the manuscript, and Dr. Haijun Hou and Dr. Lili Han for assistance in soil sampling, and Dr. Jupei Shen for technical support.

Funding. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41322007 and 41771288) and the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB15020200). L-MZ was supported by the Youth Innovation Promotion Association, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02566/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bakar R. A., Razak Z. A., Ahmad S. H., Seh-Bardan B. J., Tsong L. C., Meng C. P. (2015). Influence of oil palm empty fruit bunch biochar on floodwater pH and yield components of rice cultivated on acid sulphate soil under rice intensification practices. Plant Prod. Sci. 18 491–500. 10.1626/pps.18.491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baruah A., Baruah K. K., Gorh D., Gupta P. K. (2016). Effect of organic residues with varied carbon-nitrogen ratios ongrain yield, soil health, and nitrous oxide emission from a rice agroecosystem. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 47 1417–1429. 10.1080/00103624.2016.1178764 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodelier P. L. (2015). Bypassing the methane cycle. Nature 523 534–535. 10.1038/nature14633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassard P., Godbout S., Raghavan V. (2016). Soil biochar amendment as a climate change mitigation tool: key parameters and mechanisms involved. J. Environ. Manage. 181 484–497. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.06.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgham S. D., Cadillo-Quiroz H., Keller J. K., Zhuang Q. L. (2013). Methane emissions from wetlands: biogeochemical, microbial, and modeling perspectives from local to global scales. Glob. Change Biol. 19 1325–1346. 10.1111/gcb.12131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai F., Feng Z. J., Zhu L. Z. (2017). Effects of biochar on CH4 emission with straw application on paddy soil. J. Soils Sedim. 18 599–609. 10.1007/s11368-017-1761-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X. D., Ma L. N., Liang Y., Gao B., Harris W. (2011). Simultaneous immobilization of lead and atrazine in contaminated soils using dairy-manure biochar. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45 4884–4889. 10.1021/es103752u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Bittinger K., Bushman F. D., Costello E. K., et al. (2010). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7 335–336. 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayuela M. L., van Zwieten L., Singh B. P., Jeffery S., Roig A., Sanchez-Monedero M. A. (2014). Biochar’s role in mitigating soil nitrous oxide emissions: a review and meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 191 5–16. 10.1016/j.agee.2013.10.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad R., Klose M. (2006). Dynamics of the methanogenic archaeal community in anoxic rice soil upon addition of straw. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 57 476–484. 10.1111/j.1365-2389.2006.00791.x 22291691 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis K. M., Silver W. L., Thompson A. W., Firestone M. K. (2010). Microbial communities acclimate to recurring changes in soil redox potential status. Environ. Microbiol. 12 3137–3149. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield P. F., Liesack W., Henckel T., Knowles R., Conrad R. (1999). High-affinity methane oxidation by a soil enrichment culture containing a type II methanotroph. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 1009–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2013). UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10 996–998. 10.1038/nmeth.2604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag T. E., Toet S., Ineson P., Prosser J. I. (2010). Links between methane flux and transcriptional activities of methanogens and methane oxidizers in a blanket peat bog. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 73 157–165. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00871.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gul S., Whalen J. K., Thomas B. W., Sachdeva V., Deng H. Y. (2015). Physico-chemical properties and microbial responses in biochar-amended soils: mechanisms and future directions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 206 46–59. 10.1016/j.agee.2015.03.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. G., Sun X., Wang C., Wu M. X., Dong D., Zhong T., et al. (2016). Mitigating methane emission from paddy soil with rice-straw biochar amendment under projected climate change. Sci. Rep. 6:24731. 10.1038/srep24731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang X. N., Zhang X., Song C. L., Jiang Y., Deng A. X., He R. Y., et al. (2014). Differences in rice yield and CH4 and N2O emissions among mechanical planting methods with straw incorporation in Jianghuai area. China. Soil Till. Res. 144 205–210. 10.1016/j.still.2014.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harter J., Krause H. M., Schuettler S., Ruser R., Fromme M., Scholten T., et al. (2014). Linking N2O emissions from biochar-amended soil to the structure and function of the N-cycling microbial community. ISME J. 8 660–674. 10.1038/ismej.2013.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y. H., Zhou X. H., Jiang L. L., Li M., Du Z. G., Zhou G. Y., et al. (2017). Effects of biochar application on soil greenhouse gas fluxes: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 9 743–755. 10.1111/gcbb.12376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A., Lüke C., Frenzel P. (2011). Recovery of methanotrophs from disturbance: population dynamics, evenness and functioning. ISME J. 5 750–758. 10.1038/ismej.2010.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A., van den Brink E., Reim A., Krause S. M., Bodelier P. L. (2015). Recurrence and frequency of disturbance have cumulative effect on methanotrophic activity, abundance, and community structure. Front. Microbiol. 6:1493. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N. J., Wang B. J., Gu Z. H., Tao B. R., Zhang Z. W., Hu S. J., et al. (2016). Effects of different straw returning modes on greenhouse gas emissions and crop yields in a rice-wheat rotation system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 223 115–122. 10.1016/j.agee.2016.02.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii S., Ohno H., Tsuboi M., Otsuka S., Senoo K. (2011). Identification and isolation of active N2O reducers in rice paddy soil. ISME J. 5 1936–1945. 10.1038/ismej.2011.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii S., Yamamoto M., Kikuchi M., Oshima K., Hattori M., Otsuka S., et al. (2009). Microbial populations responsive to denitrification-inducing conditions in rice paddy soil, as revealed by comparative 16S rRNA gene analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 7070–7078. 10.1128/AEM.01481-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. M., Spor A., Brennan F. P., Breuil M. C., Bru D., Lemanceau P., et al. (2014). Recently identified microbial guild mediates soil N2O sink capacity. Nat. Clim. Change 4 801–805. 10.1038/nclimate2301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S. W., Park J. W., Seo D. C., Ok Y. S., Park K. D., Choi I. W., et al. (2016). Effect of biochar application on rice yield and greenhouse gas emission under different nutrient conditions from paddy soil. J. Environ. Eng. 142:04016046 10.1061/(Asce)Ee.1943-7870.0001083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kharub A. S., Sharma R. K., Mongia A. D., Chhokar R. S., Tripathi S. C., Sharma V. K. (2004). Effect of rice (Oryza sativa) straw removal, burning and incorporation on soil properties and crop productivity under rice-wheat (Triticum aestivum) system. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 74 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- King G. M., Schnell S. (1994). Ammonium and nitrite inhibition of methane oxidation by Methylobacter albus BG8 and Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b at low methane concentrations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60 3508–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluepfel L., Keiluweit M., Kleber M., Sander M. (2014). Redox properties of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 48 5601–5611. 10.1021/es500906d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]