Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a major cause of several infectious diseases, has become a hazardous resistant pathogen. One of the factors contributing to quinolone resistance in P. aeruginosa is mutations occurring in gyrA and parC genes encoding the A subunits of type II and IV topoisomerases, respectively, in quinolone resistance determining regions (QRDR) of the bacterial chromosome.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty seven isolates from patients with burn wounds and 20 isolates from blood, urine and sputum specimen were collected. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of ciprofloxacin were determined by agar diffusion assay. Subsequently, QRDRs regions of gyrA and parC were amplified from resistant isolates and were assessed for mutations involved in ciprofloxacin resistance after sequencing.

Results:

Nine isolates with MIC≥8 μg/ml had a mutation in gyrA (Thr83→Ile). Amongst these, seven isolates also had a mutation in parC (Ser87→ Leu or Trp) indicating that the prevalent mutation in gyrA is Thr83Ile and Ser87Leu/Trp in parC. No single parC mutation was observed.

Conclusion:

It seems that mutations in gyrA are concomitant with mutations in parC which might lead to high-level ciprofloxacin resistance in P. aeruginosa isolates from patients with burn wounds and urinary tract infections.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Fluoroquinolones, GyrA, ParC, Ciprofloxacin resistance

INTRODUCTION

A growing population of multidrug resistant bacteria has emerged as the “post antibiotic era” of infectious diseases. One prominent example is Pseudomonas aeruginosa which has been the focus of therapeutic challenges. This ubiquitous organism exists in many diverse environments, and can be isolated from various living sources. The ability of P. aeruginosa to survive in harsh conditions and endure stress has allowed the organism to persist in both community and hospitals. P. aeruginosa is commonly responsible for nosocomial infections in ICUs, including surgical site, urinary tract, pneumonia and bloodstream, eye, ear, nose and throat infections (1–4).

Due to the low permeability of its cell wall, P. aeruginosa is intrinsically resistant to most antibiotics as a result of decreased intracellular drug concentration caused by decreased uptake or increased efflux pumps expression (5–6).

Principal mechanisms of bacterial resistance to quinolones are modification of the target site (DNA gyrase) and reduction of intracellular concentration of quinolones due to mutations in the regulatory genes mexR and nfxB (7). In P. aeruginosa, resistance to quinolones is also often mediated by mutations in regulatory genes leading to upregulation of different efflux pumps systems (8–10). Mutations in plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes (pmqr) in P. aeruginosa have also been reported (11, 12) and attribute to high levels of resistance albeit at a lower scale compared to mutations in the qrdr region of the bacterium. Frequently, these resistance genes are acquired from other organisms via plasmids, transposons, bacteriophages or integrons (13).

Fluoroquinolones are an important class of wide spectrum antibacterial agents; an example is ciprofloxacin which has emerged as one of the most effective antibiotics against P. aeruginosa (14). Fluoroquinolones target DNA gyrase (topoisomerase II) and topoisomerase IV, which are vital in replication of bacterial DNA. DNA gyrase consists of A2 and B2 subunits encoded by the gyrA and gyrB genes. Topoisomerase IV is encoded by parC and parE subunits (15–17).

Alterations in QRDR in both gyrA and parC genes are now known to play an integral role in quinolone resistance in P. aeruginosa (18–20).

The aim of this study was to find possible mutations in gyrA of DNA gyrase and parC of topoisomerase IV in ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. The correlation between these mutations and minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of ciprofloxacin-resistance was also determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

Thirty seven isolates were obtained from patients with burn wounds admitted to Shahid Mottahari Burn Hospital and 20 isolates collected from blood, urine and sputum specimen at Shahid Rajaei Burn Hospital (2009–2013) in Tehran, Iran. Resistance to ciprofloxacin was evaluated by the Kirby-Bauer test (21). P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, E. coli ATCC 25922 and S. aureus ATCC 25932 were used as susceptibile controls and compared to CLSI references (22–24). MIC of ciprofloxacin was measured by microdilution in ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates.

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing.

DNA was extracted from ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates by the SET buffer method (25). QRDR amplification of gyrA and parC from resistant isolates was carried out using specific primers: gyrA-1 (5′-GTGTGCTTTATGCCATGAG-3′) and gyrA-2 (5′-GGTTTCCTTTTCCAGGTC-3′) for the amplification of 287 bp of the fluoroquinolone resistance-determining region of the gyrA gene and parC-1 (5′-CATCGTCTACGCCATGAG-3′) and parC-2 (5′-AGCAGCACCTCGGAATAG-3′) were used to amplify 267 bp of the fluoroquinolone resistance-determining region of parC as previously reported (10). In the design of parC amplification, the annealing temperature was increased to 59°C and for some samples up to 60°C. PCR enhancer was also added to augment the efficiency of PCR (26, 27). Amplified products were then separated using 1.5% agarose gels and PCR products were sequenced (Bioron, Germany).

Analysis of DNA sequences.

DNA sequences obtained using forward and reverse primers were processed by Bioeditor program using pairwise alignment. The sequence of each of sample was compared with P. aeruginosa PAO1 sequence. The sequences were multiple aligned by Clustal W2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) in order to detect mutations. Nucleotide Sequences were translated by Expasy Bioinformatics Resource Portal (http://web.expasy.org/translate/) then compared with P. aeruginosa PAO1 protein sequence using Clustal W2 to find changes in amino acids sequences.

RESULTS

Among 57 isolates, 41.37% showed resistance and 15.51% showed intermediate susceptibility to ciprofloxacin as detected by disc diffusion test (Table 1). MICs of ciprofloxacin were measured for 30 isolates (Fig. 1) of which 22 isolates were resistant (MIC >4 μg/ml).

Table 1.

Point mutations in resistant isolates and their susceptibility to ciprofloxacin

| No. | Isolate name | gyrA mutation | Silent mutation in gyrA | parC mutation | Silent mutation in parC | MIC μg/ml | Diameter of inhibitory zone (mm) | Mutation in both genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | B1 | Thr ➡ Ile | _ | Ser ➡ Leu | Ala ➡ Ala | 32 | 12 | Yes |

| ACC83ATC | TCG87TTG | GCT115GCG | ||||||

| 2 | B14 | Thr ➡ Ile | _ | Ser ➡ Leu | Ala ➡ Ala | 64 | 13 | Yes |

| ACC83ATC | TCG87TTG | GCT115GCG | ||||||

| 3 | B25 | Thr ➡ Ile | _ | Ser ➡ Leu | Ala ➡ Ala | 64 | 10 | Yes |

| ACC83ATC | TCG87TTG | GCT115GCG | ||||||

| 4 | B32 | Thr ➡ Ile | _ | Ser ➡ Leu | Ala ➡ Ala | 64 | 13 | Yes |

| ACC83ATC | TCG87TTG | GCT115GCG | ||||||

| 5 | B38 | Thr ➡ Ile | _ | Ser ➡ Leu | Ala ➡ Ala | 32 | 13 | Yes |

| ACC83ATC | TCG87TTG | GCT115GCG | ||||||

| 6 | B48 sensitive | _ | _ | _ | Ala ➡ Ala | 1 | 30 | No |

| Ser ➡ Leu | GCT115GCG | |||||||

| 7 | B50 | Thr ➡ Ile | _ | TCG87TTG | Ala ➡ Ala | 16 | 11 | Yes |

| ACC83ATC | GCT115GCG | |||||||

| 8 | S2 | Thr ➡ Ile | Val ➡ Val | _ | _ | 32 | 10 | _ |

| ACC83ATC | GTA103GTC | |||||||

| Ala ➡ Ala | ||||||||

| GCA118GCG | ||||||||

| Ala ➡ Ala | ||||||||

| GCG136GCC | ||||||||

| 9 | S4 | Thr ➡ Ile | Val ➡ Val | _ | _ | 32 | 11 | _ |

| ACC83ATC | GTA103GTC | |||||||

| Ala ➡ Ala | ||||||||

| GCA118GCG | ||||||||

| Ala ➡ Ala | ||||||||

| GCG136GCC | ||||||||

| 10 | S14 | _ | His ➡ His | _ | Ala ➡ Ala | 8 | 15 | No |

| CAC132CAT | GCT115GCG | |||||||

| 11 | S20 | Thr ➡ Ile | _ | Ser ➡ Trp | Ala ➡ Ala | 64 | 10 | Yes |

| ACC83ATC | TCG87TGG | GCT115GCG |

Fig. 1.

Ciprofloxacin sensitivity test using Kirby-Bauer test

Amongst the 57 isolates, 30 isolates were selected for the MIC test based on CLSI principles. Of the 30 clinical isolates, 22 isolates (73.3%) were resistant, 4 isolates (13.3%) showed intermediate susceptibility to CIP and 4 isolates (13.3%) were susceptible to CIP.

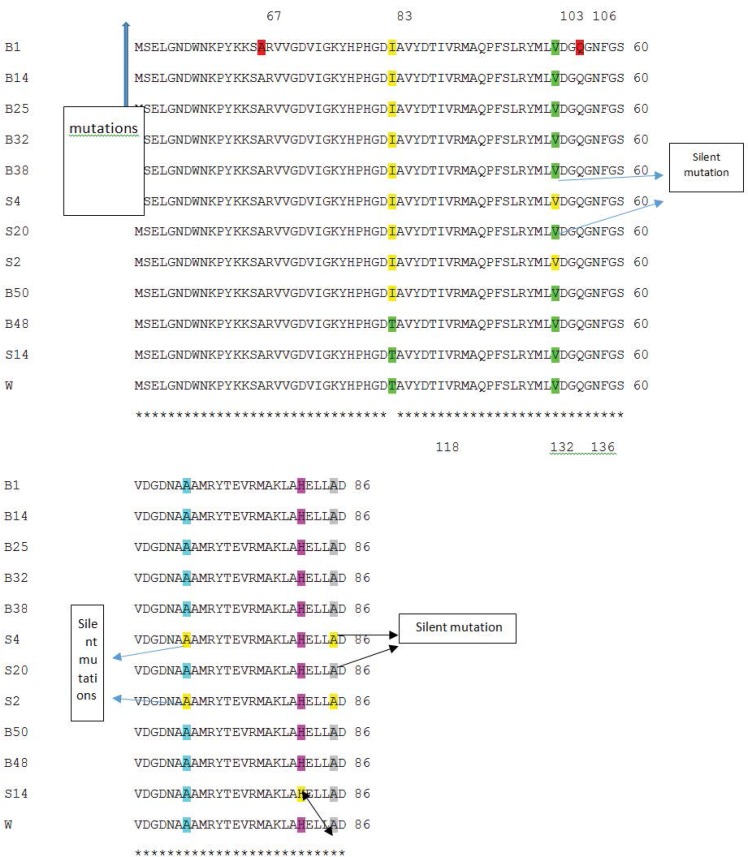

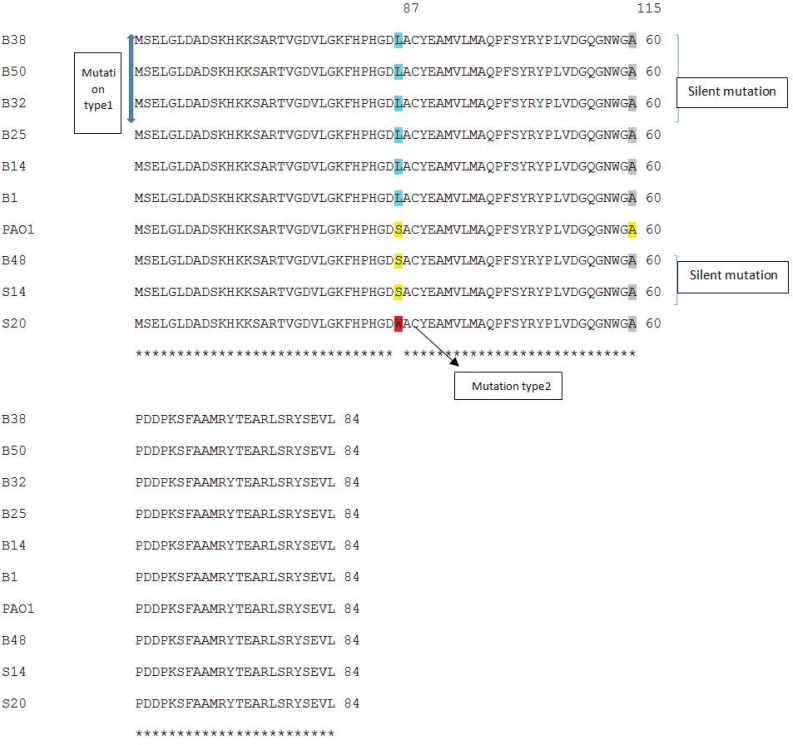

PCR amplification of gyrA and parC genes were carried out using DNA from 22 ciprofloxacin resistant isolates of which 10 were selected for gyrA sequencing and 8 for parC sequencing. Finally, in order to detect the correlation between resistance and gyrA and parC mutations, the results of sequencing were analyzed (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of gyrA PCR products sequences with P. aeruginosa PAO1 using CLUSTAL 2.1 multiple sequence alignment.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of parC PCR products sequences with P. aeruginosa PAO1 using CLUSTAL 2.1 multiple sequence alignment.

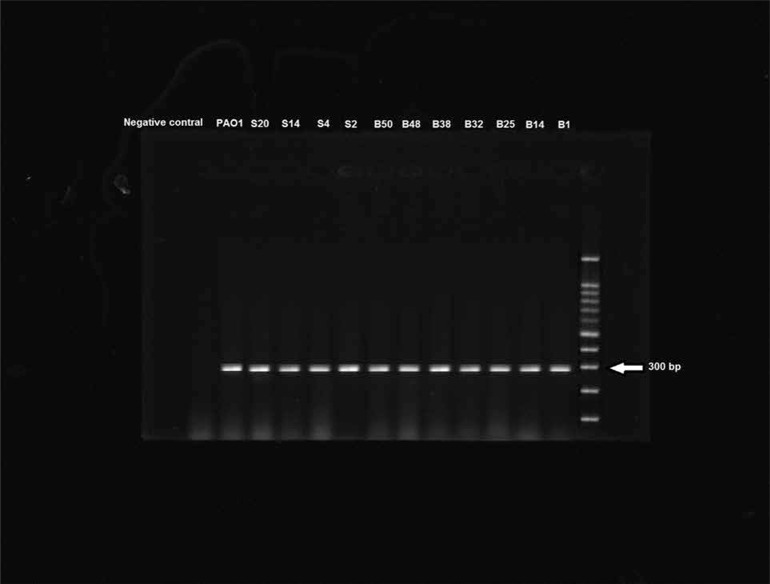

Amplification of gyrA resulted in specific bands of 300 bp (Fig. 2). P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was used as a control for the presence of qrdr region, isolate B48 which was sensitive was used for comparison and a negative control was used as contamination control.

Fig. 2.

PCR products amplified with gyrA specific primers and electrophoresed on agarose gel

DISCUSSION

Due to the growing number of antibiotic resistant bacteria, the significance of this resistance in MDR P. aeruginosa strains must be taken into greater consideration. The elucidation of the mechanisms leading to this resistance is one of the key factors involved in the treatment of hospital patients with more narrow spectrum, target specific and modified antibiotics (10).

In this study, resistance to ciprofloxacin was 41.37% which is close to the report by Tohidpour and colleagues in Tehran (35%) (28) but lower than the rates reported by Saderi and coworkers’ study in Tehran (55%) (29) and another report of Nouri and coworkers from Tabriz, Iran (30). In addition, results from the study by Lu and coworkers showed resistance of P. aeruginosa to ciprofloxacin in Asia-Pacific region from 2009 to 2010 was around 44.4% (31).

However, the resistance to ciprofloxacin obtained in this study was higher compared to reports from Canada (27%) (32) and also higher than published data from USA (33.1%) (33).

Statistics indicate that different resistance patterns exist among various regions. The magnitude of antibiotic use might contribute to the variety of antibiotic resistance range; therefore, elevated resistance rate in Asia might be associated with the notably increased use of antibiotics in the area (29, 31).

One of the major mechanisms involved in the development of quinolone resistance is the mutational alterations in DNA gyrase. In this study, almost 90% of resistant isolates had a gyrA mutation and the most common was the conversion of threonine which is a polar amino acid to non-polar isoleucine amino acid at codon 83. Moreover, high-level resistance is usually associated with the presence of both gyrA and parC mutations simultaneously and one of the frequent mutation in parC changed serine 87 to leucine and more importantly, to tryptophan (Table 1, Figs 3 and 4). Pasca and coworkers have reported an overwhelming percentage of gyrA and parC mutations as causes for fluoroquinolone resistance in P. aeruginosa isolates from Northern Italian hospitals (34).

Kulberge and her colleagues have shown that single mutations in gyrA or gyrB caused low-level resistance whereas high-level resistant mutants had double mutations in gyrA and parC, parE, nfxB or unknown genes (16).

An evaluation of samples collected in this report from urine, burn wounds and sputum, show high level resistance with MIC>8 μg/ml and mutations in gyrA and parC in the isolates.

In the present study, among 8 resistant isolates, 7 had both gyrA and parC mutations causing relatively high level resistance (MIC≥16 μg/ml). The resistance of 1 isolate (S14) with only silent mutations was comparatively lower than the other resistant mutants (MIC=8 μg/ml and inhibitory zone diameter of 15 mm). It can hence be concluded that other resistance mechanisms except mutations in gyrA and parC can be held responsible for this low-level resistance (Table 1).

The alteration of polar threonine (Thr) to the non-polar and highly hydrophobic isoleucine (Ile) does not occur in active site of enzyme; thus the enzyme is able to maintain its function. This mutation is likely to influence the gyrase- quinolone interaction by loss of essential enzyme- drug contacts or conformational modifications that may ultimately result in antibiotic resistance. The presence of gyrA mutation in all resistant isolates endorses the fact that DNA gyrase is pivotal target enzyme in ciprofloxacin resistance in P. aeruginosa (35–37).

This data substantiates the experiment conducted by Higgins and coworkers in 2003 indicating that the main mechanism of fluoroquinolone resistance in P. aeruginosa is mediated mainly through mutations in gyrA and mutations in parC genes are subsidiary (38). Reports by Salma and coworkers (39) in Lebanon also substantiate our results and other studies (27, 36) that P. aeruginosa resistant mutants with sole parC mutations have not been detected.

CONCLUSION

Results from this study and validation from previous research postulate that gyrA mutations are the major mechanism of resistance to fluoroquinolone for clinical strains of P. aeruginosa and demonstrate that DNA gyrase encoding gene, gyrA is the primary target for fluoroquinolone and further mutations in parC could lead to a higher level of quinolone resistance. This is the first report of parC mutations detected in addition to gyrA mutations reported earlier in resistant P. aeruginosa isolates from Tehran, Iran.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the funding received from Vice Chancellor for Research, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kollef MH, Micek ST. Strategies to prevent antimicrobial resistance in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2005; 33: 1845–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett JV, Jarvis WR, Brachman PS. (2007) Bennett & Brachman's Hospital Infections, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhlmann J, Dalhoff A, Zeiler HJ. (2012) Quinolone Antibacterials, Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potron A, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Emerging broad-spectrum resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii: Mechanisms and epidemiology. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015; 45: 568–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hancock RE, Speert DP. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and impact on treatment. Drug Resist Updat 2000; 3: 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahmani-Badi A, Abdi-Ali A, Falsafi T. Association of MexAB-OprM with intrinsic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to aminoglycosides. Ann Microbiol 2007; 57: 425–429. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aires JR, Köhler K, Nikaido H, Plésiat P. Involvement of an active efflux system in the natural resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to aminoglycosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999; 43: 2624–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jalal S, Ciofu O, Høiby N, Gotoh N, Wretlind B. Molecular mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000; 44: 710–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Islam S, Jalal S, Wretlind B. Expression of the MexXY efflux pump in amikacin-resistant isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Microbiol Infect 2004; 10: 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorgani NS, Ahlbrand S, Patterson A, Pourmand N. Detection of point mutations associated with antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2009; 34: 414–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Cano ME, Velasco C, Martínez-Martínez L, Pascual A. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance: an update. J Infect Chemother 2011; 17:149–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araujo BF, Ferreira ML, Campos PA, Royer S, Batistão DW, Dantas RC, et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa carrying aac(6')-Ib-cr, qnrS1 and blaSPM Genes in Brazil. PLoS One 2016; 11(5):e0155914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert P A. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J R Soc Med 2002; 95 (Suppl 41): 22–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mouneimné H, Robert J, Jarlier V, Cambau E. Type II topoisomerase mutations in ciprofloxacin-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999; 43: 62–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooper DC. Mode of action of fluoroquinolones. Drugs 1999; 58: 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kugelberg E, Löfmark S, Wretlind B, Andersson DI. Reduction of the fitness burden of quinolone resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 55: 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jalal S, Wretlind B. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance in clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb Drug Resist 1998; 4: 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chenia HY, Pillay B, Pillay D. Analysis of the mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in urinary tract pathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 58: 1274–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ronald AR, Low D. (2012) Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics (Eds), Birkhäuser, Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redgrave LS, Sutton SB, Webber MA, Piddock LJ. Fluoroquinolone resistance: mechanisms, impact on bacteria, and role in evolutionary success. Trends Microbiol 2014; 22: 438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer AW, Perry DM, Kirby WMM. Single-disk antibiotic-sensitivity testing of Staphylococci: an analysis of technique and results AMA. AMA Arch Intern Med 1959; 104:208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moosdeen F, Williams J, Secker A. Standardization of inoculum size for disc susceptibility testing: a preliminary report of a spectrophotometric method. J Antimicrob Chemother 1988; 21: 439–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldman E, Green LH. (2015) Practical Handbook of Microbiology, CRC Press, Felorida, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsukatani T, Suenaga H, Shiga M, Noguchi K, Ishiyama M, Ezoe T, et al. Comparison of the WST-8 colorimetric method and the CLSI broth microdilution method for susceptibility testing against drug-resistant bacteria. J Microbiol Methods 2012; 90: 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Russel D. (2001) Molecular cloning. 3rd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartlett JM, Stirling D. (2003). PCR protocols, Springer, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter IW, Schuller M, James GS, Sloots TP, Halliday CL. (2010). PCR for clinical microbiology: an Australian and international perspective, springer science & business media. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tohidpour A, Najar Peerayeh S, Najafi S. Detection of DNA gyrase mutation and multidrug efflux pumps hyperactivity in ciprofloxacin resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 1:1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saderi H, Lotfalipour H, Owlia P, Salimi H. Detection of metallo-β-lactamase producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from burn patients in Tehran, Iran. Lab Med 2010; 41: 609–612. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nouri R, Ahangarzadeh Rezaee M, Hasani A, Aghazadeh M, Asgharzadeh M. The role of gyrA and parC mutations in fluoroquinolones-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Iran. Braz J Microbiol 2016; 47:925–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu PL, Liu YC, Toh HS, Lee YL, Liu YM, Ho CM, et al. Epidemiology and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Gram-negative bacteria causing urinary tract infections in the Asia-Pacific region: 2009–2010 results from the study for monitoring antimicrobial resistance trends (SMART). Int J Antimicrob Agents 2012; 40: S37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karlowsky JA, Lagacé-Wiens PR, Simner PJ, DeCorby MR, Adam HJ, Walkty A. Antimicrobial resistance in urinary tract pathogens in Canada from 2007 to 2009: CANWARD surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:3169–3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones ME, Draghi DC, Thornsberry C, Karlowsky JA, Sahm DF, Wenzel RP. Emerging resistance among bacterial pathogens in the intensive care unit–a European and North American Surveillance study (2000–2002). Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2004; 3: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasca MR, Dalla Valle C, De Jesus Lopes Ribeiro AL, Buroni S, Papaleo MC, Bazzini S. Evaluation of fluoroquinolone resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa multidrug resistance clinical isolates. Microb Drug Resist 2012; 18:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wydmuch ZO, Skowronek-Ciolek K, Cholewa, Mazurek U, Pacha J, Kepa M, et al. GyrA mutations in ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Silesian Hospital in Poland. Pol J Microbiol 2005; 54: 201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aldred KJ, Kerns RJ, Osheroff N. Mechanism of quinolone action and resistance. Biochemistry 2014; 53: 1565–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drlica KA, Mustaev TR, Towle G, Luan RJ, Kerns, Berger JM. Bypassing fluoroquinolone resistance with quinazolinediones: studies of drug–gyrase–DNA complexes having implications for drug design. ACS Chem Biol 2014; 9: 2895–2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins P, Fluit A, Milatovic D, Verhoef J, Schmitz F-J. Mutations in gyrA, parC, mexR and nfxB in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2003; 21: 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salma R, Dabboussi F, Kassaa I, Khudary R, Hamze M. gyrA and parC mutations in quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Nini Hospital in North Lebanon. J Infect Chemother 2013; 19: 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]