Abstract

Background:

Our aim was to investigate preoperative chemoradiation therapy (pCRT) response in locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) comparing standardized index of shape (SIS) obtained from dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) with intravoxel-incoherent-motion-modelling-derived parameters by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI).

Materials and methods:

Eighty-eight patients with LARC were subjected to MRI before and after pCRT. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), tissue diffusion (Dt), pseudodiffusion (Dp) and perfusion fraction (f) were calculated and percentage changes ∆ADC, ∆Dt, ∆Dp, ∆f were computed. SIS was derived comparing DCE-MRI pre- and post-pCRT. Nonparametric tests and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were performed.

Results:

A total of 52 patients were classified as responders (tumour regression grade; TRG ⩽ 2) and 36 as not-responders (TRG > 3). Mann–Whitney U test showed statistically significant differences in SIS, ∆ADC and ∆Dt between responders and not-responders and between complete responders (19 patients with TRG = 1) versus incomplete responders. The best parameters to discriminate responders by nonresponders were SIS and ∆ADC, with an accuracy of 91% and 82% (cutoffs of −5.2% and 18.7%, respectively); the best parameters to detect pathological complete responders were SIS, ∆f and ∆Dp with an accuracy of 78% (cutoffs of 38.5%, 60.0% and 83.0%, respectively). No increase of performance was observed by combining linearly each possible couple of parameters or combining all parameters.

Conclusion:

SIS allows assessment of preoperative treatment response with high accuracy guiding the surgeon versus more or less conservative treatment. DWI-derived parameters reached less accuracy compared with SIS and combining linearly DCE- and DWI-derived parameters; no increase of accuracy was obtained.

Keywords: assessment response, diffusion parameters change, LARC, neoadjuvant therapy, SIS change

Introduction

Preoperative radiation therapy and concomitant chemotherapy (pCRT) combined with total mesorectal excision (TME) is the standard of care in locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC).1–7 Recently, conservative surgical approaches are being developed for early rectal cancer and for patients with significant response after pCRT,1–4 while a ‘wait and see’ policy was adopted when a complete clinical response is reached after pCRT reducing morbidity and provides a ‘true’ organ-sparing approach.5,6 Complete response (CR) was obtained after pCRT with a percentage of 24% of patients.8,9 However, several studies report that morphological magnetic resonance imaging (mMRI) alone cannot to detect pCRT changes in the early phase. In fact, in this phase, tumour change induced by pCRT cannot correspond to a visible and appreciable lesion size reduction;10 it’s difficult to differentiate residual tumour by fibrosis.11 Several authors focus their attention on the study of functional quantitative imaging modality10–13 such as dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). DCE-MRI has proven useful in detecting residual tumour after pCRT.10,14 Authors have previously examined DCE-MRI data to assess pCRT response in LARC,15–17 individuating the standardized index of shape (SIS),15 a simple semiquantitative parameter capable of detecting significant and CR after CRT in LARC with high accuracy. Moreover, several researchers have proposed functional parameters derived by DWI as potential biomarkers for treatment response.18 Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) can be used as an imaging biomarker to reflect biological tumour changes and to monitor tumoural response to pCRT.10 The intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) model for analysing DWI data allows obtaining tissue diffusion and perfusion parameters and can be used to predict therapy response19–23

The objective of this study is to examine DCE-MRI and DWI diagnostic accuracy in the pathological-response assessment after pCRT in LARC: SIS by DCE-MRI was compared to diffusion parameters derived IVIM model by DWI.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

Eighty-eight consecutive patients with median age of 64.6 years (range 44–84 years) were enrolled in this prospective study, from March 2013 to December 2016. All patients had rectal adenocarcinoma, histologically proven. Inclusion criteria were: clinical T4–3 or nodal involvement. Exclusion criteria were: inability to give informed consent, previous rectal surgery, and contraindications to MRI. The present study was approved by the National Cancer Institute of Naples local ethical committee (institutional deliberation n. 357 of 20.04.2010). All participants provided written informed consent for inclusion in the present study. In this protocol, sample size is obtained using the one-sided t test in a one-sample proportion condition. The significance level of the test was targeted at 0.50. Group sample size of at least 82 cases achieves 80% power to detect a difference between the response accuracy rate of 0.6, considering a known success proportion of 89% (accuracy of SIS reported by Petrillo and colleagues16), an expected success proportion of sample of 95% and a true difference of response accuracy rate δ = 0.

Table 1 reports patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and histopathological findings.

| Characteristics | All patients n = 88 (%) | TRG 1–2 n = 52 |

TRG 3–4 n = 36 |

p * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | >0.05 | |||

| Male/female | 62 (71)/9 (29) | 35/17 | 27/9 | |

| Median age (range) | 66 (44–84) | 69 (47–84) | 63 (44–81) | |

| Gunderson risk | >0.05 | |||

| Intermediate: T3N0 | 7 (6.8) | 5 | 2 | |

| Moderately high: T3N1, T4N0 | 35 (38.6) | 20 | 15 | |

| High: T3N2, T4N1–2 | 46 (47.7) | 27 | 19 | |

| Distance from anal verge | >0.05 | |||

| ⩽5 cm | 43 (49) | 26 | 17 | |

| >5 cm | 45 (51) | 26 | 19 | |

| Circumferential resection margin | >0.05 | |||

| >2 mm | 28 (32) | 15 | 13 | |

| ⩽2 mm | 21 (24) | 15 | 6 | |

| ⩽1 mm | 38 (43) | 22 | 16 | |

| Not measurable | 1* (1) | 0 | 1 | |

| Pathological T | <0.01 | |||

| T0–2 | 73 (83) | 50 | 23 | |

| T3–4 | 15 (17) | 2 | 13 | |

| Pathological N | <0.05 | |||

| N0 | 71 (81) | 46 | 25 | |

| N1–2 | 17 (19) | 6 | 11 |

Not measurable for intraperitoneal lesion.

TRG, tumour regression grade; T0–4, size and extent of tumour; N0–2, extent of lymph node spread.

Neoadjuvant therapy and surgical approach

External radiation therapy was executed using one posterior–anterior and two lateral fields or intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) system. Standard fractions of 1.8 Gy/day were given, five times a week up to a total dose of 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions. Treatment planning details have been previously reported.24–26 Planning target volume (PTV) for IMRT was produced according to the 83 recommendations of the International Commission for Radiation Units.27 Each patient received the standard treatment with capecitabine at a dose of 825 mg/m2 twice daily, 5 days a week, for 5 weeks.

Patients underwent TME 8 weeks ± 1 week after the end of pCRT.

Magnetic resonance imaging data acquisition

DCE-MRI was performed before and after pCRT (84–95 days as the range for two MRI exams) with a 1.5T scanner (Magnetom Symphony, Siemens Medical System, Erlangen, Germany) and phased-array body coil. Precontrast coronal T1-weighted two-dimensional (2D) turbo spin-echo (TSE) images, sagittal and axial T2 weigthed (T2w) 2D TSE images were acquired. Axial DW images were obtained with spin-echo diffusion-weighted echo–planar sequence (SE-DW-EPI) at b values equal to 0, 50, 100, 150, 300, 600, 800 s/mm2. Axial dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fast low angle shot three-dimensional gradient-echo images were obtained: 1 sequence before and 10 sequences, after intravenous injection of 0.1 mmol/kg of a positive, gadolinium-based paramagnetic contrast agent (Gd-DOTA, Dotarem, Guerbet, Roissy-CdG-Cedex, France) at 2 ml/s of flow rate, followed by a 10 ml saline flush at the same rate. Sagittal, axial and coronal postcontrast T1-weighted 2D TSE images, with and without fat saturation were also acquired. Table 2 reports MR sequence parameters. In order to reduce respiratory artefacts, each patient received bowel preparation and antispasmodic medication.

Table 2.

Pulse sequence parameters on magnetic resonance studies.

| Sequence | Orientation | TR/TE/FA (ms/ms/degree) |

FOV (mm × mm) |

Pixel spacing | ST/gap (mm/mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1w 2D TSE | Coronal | 499/13/150 | 450 × 450 | 0.87 × 0.87 | 3/0 |

| T2w 2D TSE | Sagittal | 4820/98/150 | 250 × 250 | 0.78 × 078 | 3/0 |

| T2w 2D TSE | Axial | 3970/98/150 | 250 × 250 | 0.78 × 0.78 | 3/0 |

| SE-DW-EPI | Axial | 2700/83 | 270 × 230 | 1.70 × 1.70 | 4/0 |

| T1w FLASH 3D | Axial | 9.8/4.76/25 | 330 × 247 | 0.59 × 0.59 | 3/0 |

| T1w FLASH 3D | Axial | 9.8/4.76/25 | 330 × 247 | 0.59 × 0.59 | 3/0 |

| T1w 2D TSE | Sagittal | 538/13/150 | 250 × 250 | 0.48 × 0.48 | 3/0 |

| T1w 2D TSE | Coronal | 538/13/150 | 250 × 250 | 0.48 × 0.48 | 3/0 |

| T1w 2D TSE | Axial | 450/12/150 | 270 × 236 | 0.52 × 0.52 | 3/0 |

AT, acquisition time; DW, diffusion weighted; EPI, echo–planar sequence image; FA, flip angle; FLASH, fast low angle shot; FOV, field of view; SE, spin echo; ST, slice thickness; TE, echo time; TF, turbo factor; T1w, T1 weighted; TSE, turbo spin echo; T2w, T2 weighted; TR, repetition time; 2D, two dimensional; 3D, three dimensional.

Magnetic resonance image data analysis

Image evaluation was done by consensus of two radiologists with 25 years and 10 years of experience in abdominal MRI reading and assessing.

Radiologists, using precontrast T1-weighted images,28 drawn manually regions of interests (ROIs) along tumour contours, covering the whole lesion with exclusion of peripheral fat, avoiding artefact and blood vessels. For DW-MRI, the radiologists, using DWI with the highest b value, manually drew ROIs along tumour contours to obtain DW-MR volume of interest (VOI).

In order to perform SIS analysis, an OsiriX (Pixmeo SARL, Bernex, Switzerland) plugin has been developed by the authors.29 For each VOI using the time intensity, curves were calculated using the median value of two dynamic parameters: the maximum signal difference (MSD) and the washout slope (WOS).30 Then, the percentage changes were calculated before and after pCRT (ΔMSD = (MSD1 − MSD2)/MSD1 × 100 and ΔWOS = (WOS1 − WOS2)/WOS1 × 100), and their combination as defined by Petrillo and colleagues.15

ADC was calculated using the mono-exponential model,19,20 while IVIM-derived parameters19,20,23,31–34 were calculated by means of variable projection (VARPRO) algorithm.35 In a previous study we reported that the VARPRO algorithm is superior to the conventional Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm for nonlinear curve fitting in the IVIM method for DW-MRI data analysis.36

All analyses were performed using Matlab R2007a (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA).

No image coregistration was used: we took care to avoid slices where motion artefacts were visible; moreover, a volumetric analysis in order to estimate functional parameters was done to minimize voxel misalignment errors.

Evaluation of pathologic response

Pathologic response evaluation was effected using the procedure described by both Avallone and colleagues24 and Andreola and colleagues,37 considering the TRG used by Mandard and colleagues,38 assessed by two experienced pathologists; patients with TRG 1 or 2 were classified as major responders, while the remaining patients (TRG 3, 4, or 5) were considered as nonresponders. Patients with TRG 1 were categorized as complete responders.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as median ± standard deviation values. Percentage changes of perfusion and diffusion parameters among responders and nonresponders and among pathological complete responders and incomplete responders were analysed using the Mann–Whitney nonparametric test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated to obtain diagnostic performance of SIS and diffusion parameters. Area under the ROC curve (AUC) was considered and optimal thresholds were obtained maximizing the Youden index. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were performed. Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess if the results were statistically significant. McNemar tests were used in order to compare diagnostic performance for each modality and derived parameters. Moreover, a linear classifier was used to assess diagnostic performance of the parameters’ couple combinations, using percentage change of each single parameter and of all derived parameters obtaining sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy.

A p value < 0.05 was considered significant for all tests. All analyses were performed using Statistics Toolbox of Matlab R2007a.

Results

Each patient had rectal adenocarcinomas; after pCRT and TME, 19 patients had TRG 1, 33 had TRG 2, 21 had TRG 3, 15 had TRG 4, while there were none with TRG 5. Consequently, 52 patients were responders and 19 complete responders by TRG.

Table 1 reports patient characteristics, SIS, ΔADC, ΔDt, ΔDp, Δf and histopathological findings.

Mann–Whitney nonparametric test showed statistically significant differences in SIS, ΔADC and ΔDt median values between responder patients and nonresponders (Table 3). Table 4 reports SIS and diffusion parameters performance, while Table 5 shows the performance of each parameter’s couple combination (Δf and ΔDp, Δf and ΔDt, ΔDp and and ΔDt, SIS and ΔADC, SIS and Δf, SIS and ΔDt, SIS and ΔDp, ΔADC and Δf, ΔADC and ΔDt, ΔADC and ΔDp) to differentiate responders from nonresponders and to detect complete responders versus incomplete responders. Results were statistically significant for each parameter (Fisher’s exact test p < 0.01). SIS diagnostic performance to assess pCRT response was statistically powerful compared with ∆ADC, ∆f, ∆Dt and ∆Dp performance, resulting in an increase of values of sensitivity and specificity (p < 0.05 at McNemar test). Conversely, in the discrimination of complete pathological responders, SIS obtained the same accuracy (78%) of ∆f and ∆Dp. However, ∆f and ∆Dp had a very low sensitivity.

Table 3.

Standardized index of shape change and diffusion parameter change median values for responders and nonresponders groups.

| ∆ADC % | ∆f % | ∆Dp % | ∆Dt % | SIS % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonresponders | Median value | 15.53 | −14.77 | −8.17 | 20.04 | −34.57 |

| Standard deviation | 13.14 | 111.30 | 106.83 | 53.70 | 79.72 | |

| Responders | Median value | 28.18 | −33.16 | −19.19 | 29.09 | 60.31 |

| Standard deviation | 11.45 | 139.86 | 144.47 | 97.46 | 48.66 | |

| All | Median value | 24.65 | −31.18 | −16.98 | 25.78 | 25.18 |

| Standard deviation | 15.45 | 101.27 | 125.82 | 45.74 | 81.09 | |

| p value * | <<0.001 | 0.91 | 0.48 | <<0.001 | <<0.001 | |

Mann–Witney U test.

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; f, perfusion fraction; Dp, pseudodiffusion; Dt, tissue diffusion; SIS, standardized index of shape.

Table 4.

Performance of standardized index of shape and diffusion parameters’ change.

| AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | Cutoff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance to discriminate responders by nonresponders group | |||||||

| ∆ADC | 0.79 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 18.74 |

| ∆f | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 46.41 |

| ∆Dp | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.97 | 0.80 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 76.98 |

| ∆Dt | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 27.76 |

| SIS | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.91 | −5.16 |

| Performance to discriminate complete pathological response versus not complete response | |||||||

| ∆ADC | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.94 | 0.56 | 18.74 |

| ∆f | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.94 | 0.50 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 56.95 |

| ∆Dp | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.97 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 80.49 |

| ∆Dt | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 0.89 | 0.68 | 29.00 |

| SIS | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 0.49 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 38.46 |

∆, change in parameter; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; AUC, area under curve; f, perfusion fraction; Dp, pseudodiffusion; Dt, tissue diffusion; SIS, standardized index of shape; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Table 5.

Performance of combinations of standardized index of shape with the diffusion parameters’ change.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance to discriminate responders by nonresponders group | |||||

| SIS and ∆ADC | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.90 |

| SIS and ∆f | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.85 |

| SIS and ∆Dp | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.86 |

| SIS and ∆Dt | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| ∆Dp and ∆f | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 0.39 | 0.50 |

| ∆Dt and ∆f | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.73 |

| ∆Dt and ∆Dp | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.69 |

| ∆ADC and ∆f | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.76 |

| ∆ADC and ∆Dp | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.80 |

| ∆ADC and ∆Dt | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.77 |

| All parameters | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| Performance to discriminate complete pathological response versus not complete response | |||||

| SIS and ∆ADC | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.93 | 0.75 |

| SIS and ∆f | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 0.93 | 0.76 |

| SIS and ∆Dp | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.42 | 0.91 | 0.73 |

| SIS and ∆Dt | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.93 | 0.75 |

| ∆Dp and ∆f | 0.26 | 0.78 | 0.25 | 0.79 | 0.67 |

| ∆Dt and ∆f | 0.58 | 0.70 | 0.34 | 0.86 | 0.67 |

| ∆Dt and ∆Dp | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.41 | 0.87 | 0.73 |

| ∆ADC and ∆f | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.82 | 0.53 |

| ∆ADC and ∆Dp | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.84 | 0.60 |

| ∆ADC and ∆Dt | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.35 | 0.87 | 0.67 |

| All parameters | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 0.91 | 0.74 |

∆, change in parameter; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; AUC, area under curve; f, perfusion fraction; Dp, pseudodiffusion; Dt, tissue diffusion; SIS, standardized index of shape; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Couple parameter combinations and linear combinations of all MR-extracted parameters did not increase diagnostic performance compared with SIS, both to discriminate responders versus nonresponders and to detect pathological complete responders.

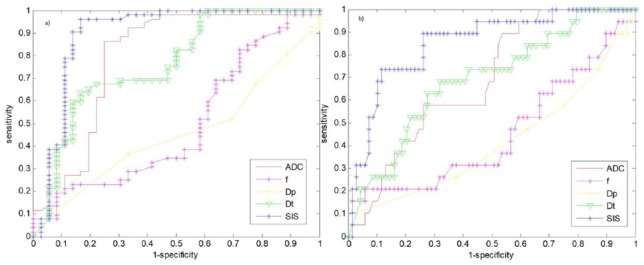

Figure 1(a) reports ROC analysis for SIS and diffusion-derived parameters differentiating responders from nonresponders. Figure 1(b) shows ROC analysis for SIS and diffusion-extracted parameters to detect complete pathological response.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis for the standardized index of shape and diffusion parameters by intravoxel incoherent motion.

This analysis discriminates responders from nonresponders (a), and complete pathological response versus noncomplete pathological response (b).

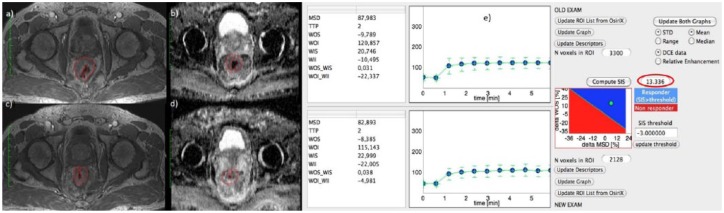

Figure 2(a), (c) and (e) show DCE-MRI images and SIS evaluation for a responder patient with TRG 2 and SIS = 13.34%. For the same patient, Figure 2(b) and (c) show the ADC map pre- and post-treatment. ΔADC value was 38.79%.

Figure 2.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance images and standardized index of shape analysis for a responder patient with tumour regression grade 2.

Figure 2(a), (c) and (e) show DCE-MRI images and SIS analysis for a responder patient with TRG 2 and ΔSIS = 13.34%. For the same patient, Figure 2(b) and (d) show the ADC map pre- and post-treatment. ΔADC value was 38.79%.

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DCE, dynamic contrast enhanced; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SIS, standardized index of shape; TRG, tumour regression grade; MSD, maximum signal difference; ROI, region of interest; STD, standard deviation; TTP, time to peak; WII, wash in intercept; WIS, wash in slope; WOI, wash out intercept; WOI_WII, wash out intercept on wash in intercept rate; WOS, wash out slope; WOS_WIS, wash out slope on wash in slope rate.

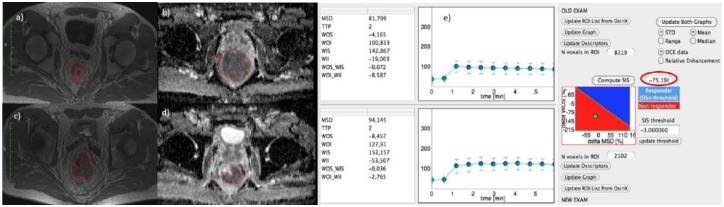

Figure 3(a), (c) and (e) show DCE-MRI images and SIS evaluation for a nonresponder patient with TRG 4 and SIS = −75.19%. For the same patient, Figure 3(b) and (c) show the ADC map pre- and post-treatment. ΔADC value was 8.92%.

Figure 3.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and standardized index of shape analysis for a nonresponder patient.

Figure 3(a), (c) and (e) show DCE-MRI images and SIS analysis for a nonresponder patient with TRG 4 and ΔSIS = −75.19%. For the same patient, Figure 3(b) and (d) show the ADC map pre- and post-treatment. ΔADC value was 8.92%.

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DCE, dynamic contrast enhanced; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SIS, standardized index of shape; TRG, tumour regression grade; MSD, maximum signal difference; ROI, region of interest; STD, standard deviation; TTP, time to peak; WII, wash in intercept; WIS, wash in slope; WOI, wash out intercept; WOI_WII, wash out intercept on wash in intercept rate; WOS, wash out slope; WOS_WIS, wash out slope on wash in slope rate.

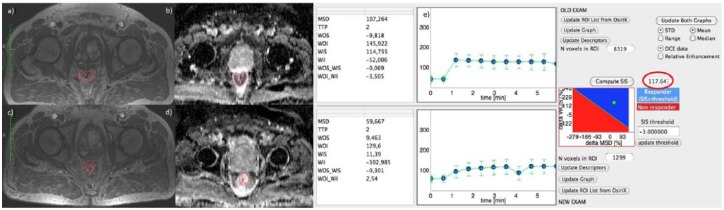

Figure 4(a), (c) and (e) show DCE-MRI images and SIS evaluation for a complete pathological responder patient with TRG 1 and SIS = 117.64%. For the same patient, Figure 4(b) and (c) show the ADC map pre- and post-treatment. ΔADC value was 54.86%.

Figure 4.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and standardized index of shape analysis for a complete pathological responder patient.

Figure 4 (a), (c) and (e) show DCE-MRI images and SIS analysis for a complete pathological responder patient with TRG 1 and ΔSIS = 117.64%. For the same patient, Figure 4(b) and (d) show the ADC map pre- and post-treatment. ΔADC value was 54.86%.

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DCE, dynamic contrast enhanced; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MSD, maximum signal difference; ROI, region of interest; SIS, standardized index of shape; STD, standard deviation; TRG, tumour regression grade; TTP, time to peak; WII, wash in intercept; WIS, wash in slope; WOI, wash out intercept; WOI_WII, wash out intercept on wash in intercept rate; WOS, wash out slope; WOS_WIS, wash out slope on wash in slope rate.

Discussion and conclusion

Recently, there has been emergent interest in functional imaging to improve treatment-response assessment allowing detection of treatment-induced changes before morphological changes are visible.10 DCE-MRI and DWI have emerged as powerful tools for predicting pCRT response in several types of tumours and also in rectal cancer. The objective of this study was to examine DCE-MRI and DWI diagnostic accuracy in the pathological-response assessment after pCRT in LARC: SIS by DCE-MRI was compared with the diffusion-parameter-derived IVIM model by DWI.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no other studies that compare DCE-MRI and DWI data in LARC and their combination for therapy-response assessment after pCRT. There are several studies that with a single modality examine the capability of evaluating therapy response.11–16,39,40 We demonstrated the ability of SIS to detect complete and significant response after pCRT in LARC15 and the strength of SIS compared with fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) examination.41 Some studies demonstrated the role of DWI in LARC for assessing therapy response39,40 and several studies evaluated the use of the IVIM model for extracting DWI data by both perfusion and diffusion parameters in different types of tumours.32,33,42 In our previous study,10 we compared SIS with diffusion parameters and their combination after short-course radiotherapy in LARC, demonstrating that no accuracy increase was obtained combining linearly each possible perfusion and diffusion parameter couple extracted by DCE-MRI and DWI or combining all functional MR-derived parameters with respect to SIS alone.

Our results showed that there were statistically significant differences between responders and nonresponder patients for SIS, ∆ADC and ∆Dt (p < 0.001 with Mann–Whitney U test). The best parameters for classifying responder and nonresponder patients were ∆ADC and SIS, with a sensitivity of 87% and 96%, a specificity of 75% and 83% and an accuracy of 82% and 91%, respectively, using cutoffs of 18.74% and −5.16%, respectively. SIS diagnostic performance to assess pCRT response was statistically significant compared with ∆ADC, ∆f, ∆Dt and ∆Dp performance, resulting in an increase both of sensitivity and specificity (p < 0.05 with McNemar test).

Patients with pathological CR have a favourable long-term outcome with very good local control and disease-free survival.38 Adopting a ‘wait and see’ policy for clinical complete responders helps prevent surgical morbidity and mortality risks.43–45 Choi and colleagues39 reported that ADC low percentile values have significant difference between pathological CR and nonpathological CR groups. Our findings showed that the best parameter for detecting complete responders was SIS, with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 74%, with a cutoff of 38.46%. SIS showed the same accuracy (78%) as IVIM-derived ∆f and ∆Dp. However, ∆f and ∆Dp had a very low sensitivity, probably due to major complexity in the IVIM-derived parameter calculation which is more influenced by image noise. Combining different functional imaging techniques could increase the specificity of therapy response. Lambrecht and colleagues46 demonstrated that combining 18F-FDG PET/computed tomography (CT) with DWI may further increase the response assessment specificity. In our study, instead, each parameter couple combination and the linear classifier of all MR-extracted parameters did not determine an increase of the diagnostic performance compared with SIS alone, both in detecting significant and complete responders.

There are some possible limits in our study: two radiologists evaluated the MR images by consensus in a single session, therefore intraobserver variability was not evaluated. IVIM-extracted parameter reproducibility was not assessed; however the use of median values for VOI for each DCE and DW parameter allows obtaining more robust measures. In this study, our aim was to assess pathological complete and significant response after neoadjuvant therapy. Other modalities having an important role in clinical diagnosis (CT, endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound) were not included, however, these could be added in a future study for patient stratification.

SIS is an encouraging DCE-MRI semiquantitative functional biomarker suitable for assessing and predicting pCRT response guiding surgeon versus more or less conservative treatment. SIS allows assessment of preoperative treatment response with high accuracy while DWI-derived parameters reached less accuracy compared with SIS. Moreover, in combining linearly DCE- and DWI-derived parameters, no increase in accuracy was obtained.

Acknowledgments

Writing/editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Manuela Di Giovanni, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Antonella Petrillo, Radiology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Roberta Fusco, Radiology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Via Mariano Semmola, Naples 80131, Italy.

Vincenza Granata, Radiology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Salvatore Filice, Radiology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Mario Sansone, Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Technologies, University ‘Federico II’ of Naples, Naples, Italy.

Daniela Rega, Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Paolo Delrio, Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Francesco Bianco, Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Giovanni Maria Romano, Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Fabiana Tatangelo, Diagnostic Pathology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Antonio Avallone, Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Biagio Pecori, Radiotherapy Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori, IRCCS, Fondazione G Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

References

- 1. Plummer JM, Leake PA, Albert MR. Recent advances in the management of rectal cancer: no surgery, minimal surgery or minimally invasive surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 9: 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, São Julião GP, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (tem) following neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer: outcomes of salvage resection for local recurrence. Ann Surg Oncol 2016; 23: 1143–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Avallone A, Aloj L, Delrio P, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to rectal cancer: are we ready for selective treatment strategies? Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2013; 13: 852–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Avallone A, Delrio P, Guida C, et al. Biweekly oxaliplatin, raltitrexed, 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid combination chemotherapy during preoperative radiation therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: a phase I-II study. Br J Cancer 2006; 94: 1809–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim HJ, Song JH, Ahn HS, et al. Wait and see approach for rectal cancer with a clinically complete response after neoadjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Colorectal Dis 2017; 32: 723–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Delrio P, Avallone A, Guida C, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to locally advanced rectal cancer: results of a single institution trial. Suppl Tumori 2005; 4: S8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fusco R, Petrillo M, Granata V, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation in neoadjuvant therapy of locally advanced rectal cancer: a systematic review. Radiol Oncol 2017; 51: 252–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Janjan NA, Crane C, Feig BW, et al. Improved overall survival among responders to preoperative chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2001; 24: 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 835–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petrillo A, Fusco R, Granata V, et al. MR imaging perfusion and diffusion analysis to assess preoperative short course radiotherapy response in locally advanced rectal cancer: standardized index of shape by DCE-MRI and intravoxel incoherent motion-derived parameters by DW-MRI. Med Oncol 2017; 34: 198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL. Rectal cancer: review with emphasis on MR imaging. Radiology 2004; 232: 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fusco R, Sansone M, Filice S, et al. Integration of DCE-MRI and DW-MRI quantitative parameters for breast lesion classification. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 237863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sansone M, Fusco R, Petrillo A, et al. An expectation-maximisation approach for simultaneous pixel classification and tracer kinetic modelling in dynamic contrast enhanced-magnetic resonance imaging. Med Biol Eng Comput 2011; 49: 485–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leach MO, Brindle KM, Evelhoch JL, et al. The assessment of antiangiogenic and antivascular therapies in early-stage clinical trials using magnetic resonance imaging: issues and recommendations. Br J Cancer 2005; 92: 1599–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petrillo A, Fusco R, Petrillo M, et al. Standardized index of shape (SIS): a quantitative DCE-MRI parameter to discriminate responders by non-responders after neoadjuvant therapy in LARC. Eur Radiol. Epub ahead of print 11 January 2015. DOI: 10.1007/s00330-014-3581-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Petrillo M, Fusco R, Catalano O, et al. MRI for assessing response to neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer using DCE-MR and DW-MR data sets: a preliminary report. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 514740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL. MRI for assessing and predicting response to neoadjuvant treatment in rectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 11: 480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jennings D, Hatton BN, Guo J, et al. Early response of prostate carcinoma xenografts to docetaxel chemotherapy monitored with diffusion MRI. Neoplasia 2002; 4: 255–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, et al. Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging. Radiology 1988; 168: 497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, et al. MR imaging of intravoxel incoherent motions: application to diffusion and perfusion in neurologic disorders. Radiology 1986; 161: 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Granata V, Fusco R, Catalano O, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) in diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) for hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation with histologic grade. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 79357–79364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Granata V, Fusco R, Catalano O, et al. Early assessment of colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases treated with antiangiogenic drugs: the role of intravoxel incoherent motion in diffusion-weighted imaging. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0142876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fusco R, Sansone M, Petrillo A. A comparison of fitting algorithms for diffusion-weighted MRI data analysis using an intravoxel incoherent motion model. MAGMA 2017; 30: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Avallone A, Pecori B, Bianco F, et al. Critical role of bevacizumab scheduling in combination with pre-surgical chemo-radiotherapy in MRI-defined high-risk locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the BRANCH trial. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 30394–30407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Avallone A, Delrio P, Pecori B, et al. Oxaliplatin plus dual inhibition of thymidilate synthase during preoperative pelvic radiotherapy for locally advanced rectal carcinoma: long-term outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 79: 670–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Avallone A, Piccirillo MC, Delrio P, et al. Phase 1/2 study of valproic acid and short-course radiotherapy plus capecitabine as preoperative treatment in low-moderate risk rectal cancer-V-shoRT-R3 (Valproic acid–short Radiotherapy–rectum 3rd trial). BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements. Prescribing, recording, and reporting photon-beam intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). ICRU Report 83. J ICRU 2010; 10: 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dresen RC, Beets GL, Rutten HJ, et al. Locally advanced rectal cancer: MR imaging for restaging after neoadjuvant radiation therapy with concomitant chemotherapy. Part I. Are we able to predict tumor confined to the rectal wall? Radiology 2009; 252: 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SIS Tool by Antonella Petrillo available requiring for email at an.petrillo@istitutotumori.na.it [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fusco R, Petrillo A, Petrillo M, et al. Use of tracer kinetic models for selection of semi-quantitative features for DCE-MRI data classification. Appl Magn Reson 2013; 44: 1311–1324. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oto A, Yang C, Kayhan A, et al. Diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of prostate cancer: correlation of quantitative MR parameters with Gleason score and tumor angiogenesis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 197: 1382–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luciani A, Vignaud A, Cavet M, et al. Liver cirrhosis: intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging-pilot study. Radiology 2008; 249: 891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wirestam R, Borg M, Brockstedt S, et al. Perfusion-related parameters in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging compared with CBV and CBF measured by dynamic susceptibility contrast MR technique. Acta Radiol 2001; 42: 123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Curvo-Semedo L, Lambregts DM, Maas M, et al. Rectal cancer: assessment of complete response to preoperative combined radiation therapy with chemotherapy–conventional MR volumetry versus diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Radiology 2011; 260: 734–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seber GAF, Wild CJ. Nonlinear regression. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fusco R, Sansone M, Petrillo A. The use of the Levenberg-Marquardt and variable projection curve-fitting algorithm in intravoxel incoherent motion method for DW-MRI data analysis. Appl Magn Reson 2015; 46: 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andreola S, Leo E, Belli F, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the lower third of the rectum surgically treated with a <10-mm distal clearance: preliminary results in 35 N0 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2001; 8: 611–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mandard AM, Dalibard F, Mandard JC, et al. Pathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. Clinicopathologic correlations. Cancer 1994; 73: 2680–2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Choi MH, Oh SN, Rha SE, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging: apparent diffusion coefficient histogram analysis for detecting pathologic complete response to chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging. Epub ahead of print 15 December 2015. DOI: 10.1002/jmri.25117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Doi H, Beppu N, Kato T, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for prediction of tumor response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy using irinotecan plus S-1 for rectal cancer. Mol Clin Oncol 2015; 3: 1129–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Petrillo A, Fusco R, Petrillo M, et al. Standardized index of shape (DCE-MRI) and standardized uptake value (PET/CT): two quantitative approaches to discriminate chemo-radiotherapy locally advanced rectal cancer responders under a functional profile. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 8143–8153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Iima M, Le Bihan D. Clinical intravoxel incoherent motion and diffusion MR imaging: past, present, and future. Radiology 2016; 278: 13–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peeters KC, Van de Velde CJ, Leer JW, et al. Late side effects of short-course preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: increased bowel dysfunction in irradiated patients—a Dutch colorectal cancer group study. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 6199–6206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Remzi FH, Fazio VW, Gorgun E, et al. Quality of life, functional outcome, and complications of coloplasty pouch after low anterior resection. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sartori CA, Sartori A, Vigna S, et al. Urinary and sexual disorders after laparoscopic TME for rectal cancer in males. J Gastrointest Surg 2011; 15: 637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lambrecht M, Deroose C, Roels S, et al. The use of FDG-PET/CT and diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging for response prediction before, during and after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2010; 49: 956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]