Summary

Objective

A growing proportion of older people live in care homes and are at high risk of preventable harm. This study describes a participatory qualitative evaluation of a complex safety improvement intervention, comprising training, performance measurement and culture-change elements, on the safety of care provided for residents.

Design

A participatory qualitative study.

Setting

Ninety care homes in one geographical locality in southern England.

Participants

A purposeful sample of care home managers, front-line staff, residents, quality improvement facilitators and trainers, local government and health service commissioners, and an embedded researcher.

Main outcome measures

Changes in care home culture and work processes, assessed using documentary analysis, interviews, observations and surveys and analysed using a framework-based thematic approach.

Results

Participation in the programme appears to have led to changes in the value that staff place on resident safety and to changes in their working practices, in particular in relation to their desire to proactively manage resident risk and their willingness to use data to examine established practice. The results suggest that there is a high level of commitment among care home staff to address the problem of preventable harm. Mobilisation of this commitment appears to benefit from external facilitation and the introduction of new methods and tools.

Conclusions

An evidence-based approach to reducing preventable harm in care homes, comprising an intervention with both technical and social components, can lead to changes in staff priorities and practices which have the potential to improve outcomes for people who live in care homes.

Keywords: Care homes, safety, preventable harm

Introduction

In many countries, care homes, also known as medical homes or assisted living facilities, are providing a home, care and support for a growing number of older people.1,2 In the UK, 4% of 75- to 84-year-olds and 50% of 90-year-olds live in care homes.3 A large proportion of these older people are frail and have complex health and care needs.4,5

Care homes in the UK generally provide a high quality of care,6 but they have nevertheless been the subject of considerable negative publicity, including criticisms of poor care, underfunding, high staff turnover and inadequate training and support for the workforce.7,8 A high prevalence of preventable harm is a particular concern.9,10 A number of programmes have been implemented in an effort to improve safety, focusing on staff education, decision support systems and better partnership working with primary care.11–16 Their impact has been variable and often disappointing, usually as a consequence of poorly designed interventions and inadequate implementation.17,18

This paper describes a qualitative evaluation of a care home safety improvement programme which attempted to address these challenges by using a participatory approach to the initiative's design and implementation. PROSPER (PROmoting Safer Provision of care for Elderly Residents) is a programme that was designed to reduce the incidence of three common causes of harm among care home residents—falls, pressure ulcers and urinary tract infections—by improving the safety culture and working practices of participating care homes. The programme comprised a partnership between care homes in one geographical locality, an improvement team from local government and members of a local academic/health service network providing evidence-based advice and conducting a formative qualitative evaluation.

This paper reports on a qualitative evaluation which aimed to support the development of the safety improvement intervention, to assess its impact on care home culture and work processes, and to understand the facilitators and barriers to implementing the improvement programme.

Methods

Evaluation design

The evaluation of the PROSPER programme was carried out using the ‘Researcher-in-Residence’ model,19,20 a practical example of a participatory approach to evaluation.21 The model positions the evaluator as an active member of an operational team with responsibility for delivering the expected outcomes of the project as well as evaluating it. The evaluator achieves this by highlighting the established evidence of what works, undertaking a pragmatic evaluation, and negotiating the meaning and utility of the findings with other members of the team. Ethics approval for the evaluation was granted jointly by the ethics committees of the participating County Council and the lead university.

The safety improvement intervention

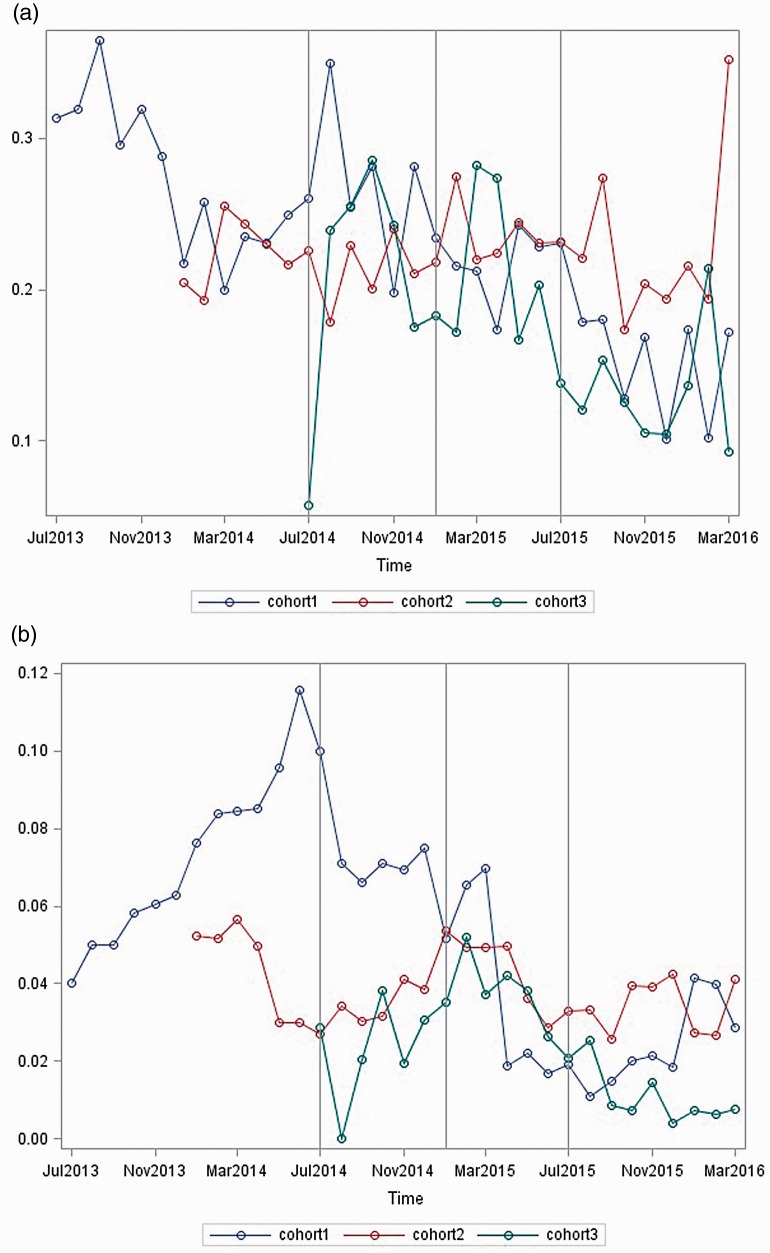

In line with the participatory design, a complex socio-technical safety improvement intervention was co-designed by participants from the care homes, local government and the evaluation team. The development of the intervention has been described elsewhere.18 Briefly, it comprised three complementary components. First, training in quality improvement methods was provided for the care home staff, initially by quality improvement experts from the local academic/health service network, then using a train-the-trainers model by members of the local government quality improvement team. Second, participating care homes were encouraged to collect their own data on the incidence of falls, pressure ulcers and urinary tract infections, which was collated, analysed using chi-squared test (SPSS version 9.3) and fed back to the homes in graphical form by the evaluation team (for example, Figure 1(a) and (b)). The data were collected by 64 of the 90 participating homes over a period of 6–12 months before and six months after the intervention and served as a tool to monitor progress. Third, the prevailing safety culture of the homes was assessed using a version of the Manchester Patient Safety Framework (MaPSaF)22 adapted for use in care homes.23 The three main components of the intervention were delivered or facilitated over a six-month period in each care home by members of the local government improvement team in partnership with NHS staff and the evaluation team. A strong emphasis was placed on providing support and advice, and sharing learning between the participating homes.

Figure 1.

(a) Run chart of rates of falls over time for three cohorts of care homes and (b) run chart of rates pressure ulcers over time for three cohorts of care homes.

Programme theory

A programme theory24 devised by the PROSPER team hypothesised that the complex intervention, when fully developed, would reduce the incidence of falls, pressure ulcers and urinary tract infections by improving the knowledge of front-line staff, changing their behaviours and providing insights into the culture of the homes with respect to safety. This in turn would be expected to reduce the rates of attendance at A&E departments and unplanned admission to hospital, thereby improving resident safety. This paper focuses on the development and testing of the intervention and its impact on safety culture and work processes.

Setting and participants

A total of 118 care homes located in one geographical area in the south-east of England initially signed up for the programme. The homes either volunteered to participate or were targeted because the local government improvement team perceived that they might benefit from being involved. Twenty-eight of these homes withdrew before or shortly after starting the programme because they felt that participation would be too time-consuming. Ninety homes therefore remained actively involved to a variable extent throughout the project period. Each home signed up to one of four separate cohorts (18 homes in each of the first two cohorts, 21 in the third and 33 in the fourth) recruited at approximately six-monthly intervals starting in July 2014 and finishing in February 2016. The homes were encouraged to choose which and how many of the safety issues they wanted to prioritise.

Participating homes were representative of all care homes in the locality and across England in terms of size and type of care provided (residential or nursing). All homes were privately owned, some independently and some members of corporate groups. As for all care homes in England, they were performance managed by local government and regulated by the health and social care regulator for England, the Care Quality Commission.

Data collection and analysis

In line with the qualitative design, a combination of data from documentary review, participant observation, interviews and a survey was used to evaluate the programme. Most of the data, obtained between July 2014 and March 2016, were collected by the evaluation team but, aligned to the participatory approach, some were collected by the improvement team and by the care home staff.

More than 500 documents produced by the care homes and local government staff were reviewed to provide an understanding of the local context. Twelve planning meetings (including one workshop to adapt Manchester Patient Safety Framework for use in care homes), training sessions and community of practice meetings were observed by the researcher-in-residence in order to understand how the participants interacted with each other in relation to safety matters. Two hundred and three semi-structured telephone interviews were carried out with the managers and front-line staff of the care homes. Twenty-three interviews were conducted with non-care home stakeholders, including health service staff and social and healthcare commissioners. In addition, a small number of informal discussions were held with family members and residents. All of these interviews enabled the embedded researcher to explore the participants' understanding of safety and how they were responding to the safety improvement intervention. A simple structured online survey of the care home managers (one per home), based largely on the components of Manchester Patient Safety Framework, was conducted to provide a quantitative assessment of any changes in perception of safety culture before and 8–20 months after the intervention. The survey data were analysed using a chi-squared test. Eighty-nine per cent (80/90) of the care homes provided both before and after responses to the survey.

Ten of the 90 care homes were purposefully sampled for a more in-depth study by the in-residence researcher and one assistant researcher. The homes were selected to represent a range of sizes, geographical locations and levels of engagement with the initiative. These in-depth studies comprised an additional 103 individual or group interviews and 60 hours of observations of front-line care and staff meetings.

Some of the interviews were audio-recorded, but at the request of the care home staff most were not and so detailed notes were taken of the interviews and observations by the researchers, including verbatim quotations. All notes were typed and shared with the participants. Using NVivo, the observational, interview, survey and documentary data were analysed iteratively by two researchers to extract key themes. Only those themes which were common to, and could be triangulated between, the different data sources are presented in this paper. In line with the participatory design of the evaluation, emerging themes were shared with the care home participants at regular meetings, with the wider evaluation team and with an expert advisory group. The interpretation of these themes was negotiated between all of these stakeholders until an acceptable level of consensus was achieved.

Results

Impact of the programme on working practices and safety culture

Evidence from across the different methods of data collection demonstrated that, as a consequence of participation in PROSPER, most of the care homes showed changes in their working practices, priorities and the ways in which they thought about their role with respect to safety. In particular, the emphasis changed from a focus on responding to regulatory imperatives to reflecting on risk for their residents. At the start of the project the manager of a small home stated:

Safety is about reducing our risk of safeguarding problems and making sure that we are ok when the Care Quality Commission comes.

But a year later, she recognised that her view had changed:

Safety is all about trying to make life as good as possible for our residents. We work for them and we want to give them a home with dignity and respect. We want them to have quality of life.

Another manager responsible for a medium-sized home described how participation in PROSPER had encouraged her staff to be more proactive in reducing risks and monitoring safety:

It's (PROSPER) helped my staff an awful lot. We're more aware of how to prevent falls. We concentrated on urinary tract infections. Now there are always jugs of juice around. There is a big board in the lounge with tips, the crosses, our graphs and newsletters. This sparks discussion with staff and relatives.

Care home staff of all levels of seniority described how they felt more empowered and more confident to suggest new ideas to improve resident safety and to implement change. One home helped residents to personalise their walking frames so that they had a greater sense of ownership and were more likely to use them (a project that became known as ‘Pimp the Zimmer’ (Figure 2)).

Figure 2.

Personalised walking frame.

Another bought new rubber ends for walking sticks to make them less likely to slip. One home started offering jelly to residents with dementia who had problems drinking fluids and another introduced coloured drink mats to remind staff to encourage high-risk patients to remain hydrated. As a carer in a medium-sized home described:

We were talking about how we could adapt the red trays used in hospital, you know where people with red trays have to be given more drinks or a certain type of food or whatever. Well then we started using red doilies (mats) for hydration, to remind us to give those people more drinks.

Several homes described how they started to involve families and residents in improving safety. About one-quarter of the relatives interviewed mentioned seeing displays on notice boards relating to PROSPER. One relative stated that she felt more confident in pouring their mother a drink, rather than relying on the staff to do so.

Care homes compete for business and do not have a tradition of collaboration but PROSPER encouraged the homes to be more outward-looking and more willing to learn from and with each other. As one carer from a small home described:

We've found it really useful to listen to feedback from other homes. For example, we found out we had a local falls prevention team. She (a member of the team) then did assessments on our residents and we made changes in the care plans. We wouldn't have known about that service if other homes didn't mention it.

The homes also described how, as a consequence of participating in PROSPER, they learnt how to work more effectively with the NHS, a relationship which had previously been fractious. In addition, they forged a more constructive and mutually appreciative relationship with their local councils. Overall, the homes described a sense of pride associated with being part of the programme.

Factors enabling the PROSPER programme

The participants identified a number of factors which they thought contributed to PROSPER's impact. They placed a high value on the encouragement, support and practical help provided by local council quality improvement facilitators and the in-residence evaluator. In particular, they appreciated the ways in which the PROSPER team introduced them to a range of specific improvement methods and tools, including data displays and the principles of the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle. A manager of a large home stated:

The tools have helped us to stop behaving like robots, to stand back and think about things.

Feedback of the charts demonstrating changes in the prevalence of safety events over time were particularly highly valued by the staff. Graphical displays of the data catalysed more informed and often more challenging conversations among the staff, and sometimes with relatives. As one senior carer described:

[PROSPER] is making carers think outside of the box and consider all the reasons for things. Like falls is not just about mobility, there may be other reasons people fall. We started to analyse the falls to see whether it is to do with capacity and weakness. We look at how often people fall, how many people fall and when. We look at what precautions are needed.

The care home staff particularly appreciated the training that they received as part of the PROSPER programme. They enjoyed learning in groups, within or between organisations and established several communities of practice to develop their thinking and exchange ideas.

Factors acting as a barrier to the PROSPER programme

The participants also identified a number of constraints to PROSPER having an impact, most of which were a consequence of the environment within which care homes currently operate in the UK. Local government interviewees felt that the high level of turn-over of senior managers in the homes was a notable barrier to successful engagement. About half of the care homes complained that they did not have time to fully commit to the programme and about one-third of homes did not feel that they gained much from taking part. One-quarter of homes complained about the quality and consistency of the support from the improvement team. Such comments reduced in later cohorts, reflecting changes in the knowledge, capacity and capability of the improvement team as the programme developed.

Discussion

Principal findings

Participation in the PROSPER programme appears to have led to notable changes in the value that care home staff place on resident safety and to changes in their working practices. While not universal, these improvements were reported by the majority of participating homes. Care home staff particularly appreciated the encouragement and support from the improvement facilitators, the opportunity to learn from other organisations and non-judgemental feedback of performance data. Major barriers included staff turnover, workload pressures and inconsistent support.

Interpretation of findings in context of wider literature

Overall, the study suggests that despite considerable economic and workforce pressures in the care home sector, there is a high level of commitment and innovative thinking among care home staff to address the problem of preventable harm. Mobilisation of these assets appears to benefit from external facilitation and the introduction of new methods and tools. These results are consistent with the growing body of theoretical and empirical evidence that improvement starts to happen when multi-faceted interventions containing both technical and social components are combined with rigorous methods of implementation and an enabling environment.18,25

Strengths and limitations

The participatory nature of the programme and the formative orientation of the evaluation both promoted a high level of engagement and commitment on the part of the care home staff.26

The results should be viewed in light of a number of features which are an inherent consequence of the formative and participatory design and the decision to develop a robust intervention prior to conducting a rigorous quantitative evaluation of its impact on resident or health system outcomes.

First, while this study provides robust insights into the face validity of the safety improvement intervention for care home staff and its impact on their norms and working practices, it does not tell us about the impact of the intervention on resident health or health system outcomes. Data were collected by the care home staff themselves and fed back as part of the intervention, but the amount and quality of the data and the lack of controls meant that no robust conclusions about effectiveness could be drawn. It would in any case have been too early to look for evidence of impact given the fact that the programme theory suggested that changes in behaviour had to precede measurable changes in outcomes. In addition, there is a growing consensus that it is inappropriate to evaluate the outcomes of improvement interventions until the nature and the mechanism of action of the intervention are fully understood.27–29

Second, while one of the advantages of the Researcher-in-Residence model is the close proximity to the project and the resulting in-depth understanding of the issues, it also risks a lack of objectivity and the researcher might have felt constrained in critiquing working practices. We believe that we counterbalanced this risk by having a wider evaluation team involved in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Implications for practice, policy and research

The findings of this study have useful implications for those leading quality improvement work in care homes. Well-designed improvement programmes with a focus on sharing ideas and using data to enable change appear to engage care home staff and can lead rapidly to changes in working practices. Such programmes may be more likely to work if they are delivered using a participatory methodology by multi-disciplinary teams bringing expertise in the local context, quality improvement, evidence-based change management and a formative approach to evaluation. The potential tensions between regulatory and performance management drivers on one side, and an improvement philosophy on the other, need to be managed carefully.

The study also contains important learning for researchers and research funders interested in the care home sector. More thought, effort and time need to go into the co-design of improvement programmes. Once the programme is optimally designed, large scale, methodologically rigorous and longer-term evaluations are needed before a definitive judgement about the effectiveness and value of a programme can be made. Given that the most effective interventions are likely to be multifaceted, studies need to be of sufficient scale to explore the relative effectiveness of the different components of the intervention.

Conclusion

PROSPER is a rare example of a participatory, evidence-informed and rigorous improvement programme carried out in the care home sector. This study provides robust qualitative evidence that well-designed improvement programmes can result in changes in what care home staff value and in their working practices. It therefore offers considerable hope to the growing number of older people living in care homes and guidance to practitioners and policy makers.

Declarations

Competing Interests

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Foundation, an independent charity based in London, England.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the evaluation was granted jointly by the ethics committees of the participating County Council and the lead university.

Guarantor

MM.

Contributorship

MM, LC and JS designed the original study protocol. LC and KAJ were responsible for recruiting and supporting the participating homes. DdS led the qualitative data collection and analysis working in particular with MM, JA and JS. LW led the quantitative data collection and analysis working in particular with JA, JS and LC. KAJ and NP worked with the lead analysts of the quantitative and qualitative data on the interpretation of the data. MM and NP wrote the first draft of the paper and all authors contributed to subsequent drafts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating care homes, including the staff, managers, residents and their families and the home owners, as well as the local government officers and staff. We are also indebted to the PROSPER Advisory Group comprising of Professor Bryony Dean Franklin, Professor Claire Goodman, Professor Steve Iliffe, Dr. Yogini Jani, Dr. James Mountford, Professor Maxine Power and Professor Mike Roberts. Zahraa Mohammed Ali, Chris Singh and Clem White provided additional research expertise for the evaluation.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Louise Butler and Julie Morris.

References

- 1.Office of National Statistics, National Population Projections, 2014. See www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/datasets/tablea21principalprojectionukpopulationinagegroups (last checked 13 December 2016).

- 2.OECD, Historical population data and projections (1950–2050). See https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=POP_PROJ (last checked 13 December 2016).

- 3.The National Care Homes Research and Development Forum. My Home Life, Quality of Life in Care Homes, A Review of the Literature, London: Help the Aged, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of Fair Trading. Survey of Older People in Care Homes, London: Office of Fair Trading, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laing W. Care of Elderly People: UK Market Survey 2010-11, London: Laing and Buisson, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Care Quality Commission. The state of adult social care services 2014 to 2017. See www.cqc.org.uk/publications/evaluation/state-adult-social-care-services-2014-2017 (last checked 7 July 2017).

- 7.Eborall C, Fenton W, Woodrow S. The State of the Adult Social Care Workforce in England 2010, London: Skills for Care, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franklin B. The Future Care Workforce. London: ILCUK. See www.ilcuk.org.uk/images/uploads/publication-pdfs/Future_Care_Workforce_Report.pdf (2014, last checked 9 January 2016).

- 9.Stubbs B, Denkinger MD, Brefka S, Dallmeier D. What works to prevent falls in older adults dwelling in long term care facilities and hospitals? An umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. Maturitas 2015; 81: 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mody L, Krein SL, Saint S, Min LC, Montoya A, Lansing B, et al. A targeted infection prevention intervention in nursing home residents with indwelling devices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175: 714–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buljac-Samardzic M, van Wijngaarden JD, Dekker-van Doorn CM. Safety culture in long-term care: a cross-sectional analysis of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire in nursing and residential homes in the Netherlands. BMJ Qual Saf 2015; 25: 424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mody L, Meddings J, Edson BS, McNamara SE, Trautner BW, Stone ND, et al. Enhancing resident safety by preventing healthcare-associated infection: a national initiative to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections in nursing homes. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: 86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim RH, Anderson JE, Buckle PW. Work domain analysis for understanding medication safety in care homes in England: an exploratory study. Ergonomics 2016; 59: 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marasinghe KM. Computerised clinical decision support systems to improve medication safety in long-term care homes: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e006539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zúñiga F, Ausserhofer D, Hamers JP, Engberg S, Simon M, Schwendimann R. The relationship of staffing and work environment with implicit rationing of nursing care in Swiss nursing homes – a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2015; 52: 1463–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang T, Yu P. The impact of electronic health records on client safety in aged care homes. Stud Health Technol Inform 2014; 201: 116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enabling Research In Care Homes (ENRICH). A Toolkit for Care Home Research. See http://enrich.nihr.ac.uk (last checked 7 July 2017).

- 18.Marshall M, de Silva D, Cruikshank L, Shand J, Wei L, Anderson J. What we know about designing an effective improvement intervention (but too often fail to put into practice). BMJ Qual Saf 2017; 26: 578–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall M, Pagel C, French C, Utley M, Allwood D, Fulop N, et al. Moving improvement research closer to practice: the Researcher-in-Residence model. BMJ Qual Saf 2014; 23: 801–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall M, Eyre L, Lalani M, Khan S, Mann S, de Silva D, et al. Increasing the impact of health services research on service improvement: the researcher-in-residence model. J R Soc Med 2016; 109: 220–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornwall A, Jewkes R. What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med 1995; 41: 1667–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirk S, Parker D, Claridge T, Esmail A, Marshall M. Patient safety culture in primary care: developing a theoretical framework for practical use. Qual Saf Health Care 2007; 16: 313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall M, Cruickshank L, Shand J, Perry S, Anderson J, Wei L, et al. Assessing the safety culture of care homes: a multi-method evaluation of the adaptation, face validity and feasibility of the Manchester Patient Safety Framework. BMJ Qual Saf 2017; 26: 751–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2015; 24: 228–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, Davis D. Improving Patient Care: The Implementation of Change in Health Care. 2nd Edition, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vindrola-Padros C, Pape T, Utley M, Fulop NJ. The role of embedded research in quality improvement: a narrative review. BMJ Qual Saf 2017; 26: 70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welsh European Funding Office. Introduction to Soft Outcomes and Distance Travelled. In A Practical Guide to Measuring Soft Outcomes and Distance Travelled – Guidance Document. Cardiff: Welsh European Funding Office. See www.networkforeurope.eu/files/File/downloads/A%20Practical%20Guide%20to%20Measuring%20Soft%20Outcomes%20and%20Distance%20Travelled%20-%20Guidance%20Document%202003.pdf (2003, last checked 13 December 2016).

- 28.Butcher B, Foster H, Marsden L, McKibben J, Anderson C and Mazey R. The Soul Record. Summary Report. Soft Outcomes for Universal Learning: A Practical Framework for Measuring the Progress of Informal Learning. Norwich: Norwich City College of Further and Higher Education. See https://soulrecord.org/sites/default/files/fields/publication/file/SOULFeb006.pdf (last checked 13 December 2016).

- 29.Parry GJ, Carson-Stevens A, Luff DF, McPherson ME, Goldmann DA. Recommendations for evaluation of health care improvement initiatives. Acad Pediatr 2013; 13: S23–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]