Short abstract

Alderson critiques our recent book on the basis that it overlooks children’s own views about their medical treatment. In this response, we discuss the complexity of the paediatric clinical context and the value of diverse approaches to investigating paediatric ethics. Our book focuses on a specific problem: entrenched disagreements between doctors and parents about a child’s medical treatment in the context of a paediatric hospital. As clinical ethicists, our research question arose from clinicians’ concerns in practice: What should a clinician do when he or she thinks that parents are choosing a treatment pathway that does not serve the child’s best interests? Alderson’s work, in contrast, focuses on the much broader issue of children’s role in decision-making about treatment and research. We argue that these different types of work are zooming in on different aspects of paediatric ethics, with its complex mix of agents, issues and relationships. Paediatric ethics overall needs a rich mix of approaches, investigating a range of different focal problems in order to further understanding. The zone of parental discretion is not incompatible with valuing children’s rights and views; its focus is a different element of a complex whole.

Keywords: Paediatrics, children, families

The complexity of paediatrics and paediatric ethics

In a recent issue of Clinical Ethics, Alderson discussed our book – When Doctors and Parents Disagree: Ethics, Paediatrics and the Zone of Parental Discretion1 – claiming that it is illustrative of ‘a fall in respect for children’s views’ (Alderson,2 p. 1). Alderson argues for the importance of children’s views, rights and wishes in any discourse about paediatric ethics and, on that basis, suggests that because the book does not explicitly engage with the child’s perspective, that this represents a deficiency. However, her argument both fundamentally misinterprets our project and represents too narrow a view of the ethical dimensions of paediatric practice.

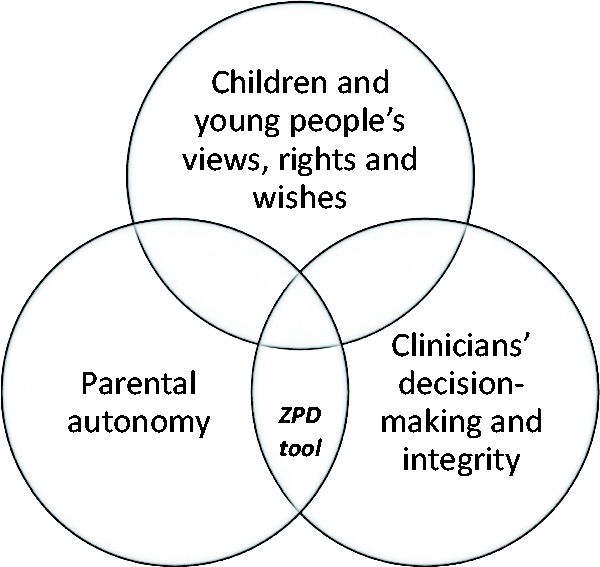

The paediatric clinical context is complex. It is characterised by patients, parents, and healthcare professionals all interacting in diverse ways in relation to a vast array of healthcare challenges for children and young people. There is much to be understood about the ethics of paediatrics – about children, young people, parents, and clinicians as particular groups, about their interactions and relationships in the clinical setting and about the range of ethical challenges that arise. The inherent complexity of the ethical aspects of this clinical context can be represented as a series of intersecting elements: children and young people’s views, rights and wishes, parental autonomy, and clinicians’ decision-making and integrity (Figure 1). Alderson2 suggests a Venn diagram to represent different perspectives on the child’s best interests (p. 5). Building on her idea, we suggest that this kind of conceptualisation can be extended more broadly to the ethical aspects of paediatrics as a whole.

Figure 1.

Ethical aspects of paediatrics.

As well as different ethical aspects, there are also many different types of ethical ‘work’ to be done in paediatric ethics: for example, helping clinicians to think through problems, empowering patients and families in their care, supporting organisations to facilitate ethical practice and so on. The complexity of the paediatric clinical context is, rightly, reflected in the diversity of work in paediatric ethics.

Zooming in

Our book focuses on one aspect of this complexity, investigates it from a particular standpoint and aims to do a specific kind of ethical work. The book’s focus is the rare but ethically very significant situation of entrenched disagreement between health professionals and parents about a child’s medical treatment. As we highlight in the book’s introduction, our approach arose from clinicians' ethical questions and focuses on the interaction between clinician integrity and parental autonomy. We are interested in the specific ethical problem of clinicians being asked by parents to give treatment that the clinicians think is not in the child’s best interests. Alderson2 correctly points out that there may be multiple perspectives on the child’s best interests (p. 5). One way of understanding the situations which we are addressing is to see them as instances where parents and doctors have different and ultimately irreconcilable perspectives on what is in the child’s best interests. For clinicians, this creates a need to make ethical decisions about whether to act in line with parents’ treatment refusals or requests, when they perceive these as contrary to the child’s best interests.

The concept that we explore in the book – the zone of parental discretion (ZPD) – was inductively derived from our experience in clinical ethics case consultations with clinicians faced with these sorts of situations. This relates to the type of ethical work that the concept is designed for: as we explain, ‘[t]he goal was to develop an explanatory concept which could assist clinicians to frame, analyse and then decide how to respond to these situations’ (Delany,3 p. 244). The central concern for clinicians in making these decisions is to consider the child’s interests and how they will be affected by parents’ requests or refusals of treatment. The tool is to help when two sets of adult decision makers disagree, i.e. parents and clinicians. Both groups should (and in our experience do) regard the child’s views and interests as the primary consideration.

The zone of parental discretion

The key idea of the ZPD is that in situations of entrenched disagreement, clinicians can accept parental decisions that the clinicians see as suboptimal for the child, so long as the decisions do not involve probable harm to the child. (It is worth noting that Alderson2 (p. 5) misquotes the threshold as ‘possible’ harm, rather than probable harm). We are not assuming that the clinicians’ perspective is more important or objectively more accurate than the parents’ perspective, simply that it is the position which they genuinely hold and must acknowledge if they are to decide and act with integrity.

The ZPD was articulated for situations where parents are the primary decision makers because of the young age of the children (Gillam4 and McDougall et al.,5 p. 16). In these situations, the difference in perspectives between clinicians and parents cannot ethically be resolved by turning to the child for a final decision or adjudication. We take the common view in paediatric bioethics, that many young children have not yet fully developed all of the capacities needed for independent medical decision-making; age is a relevant guide, but of course capacity assessment should ultimately be made on a case-by-case basis. In our view, it is the ethical obligation of clinicians and parents to make medical decisions based on the child’s best interests, broadly considered, including the child’s wishes. To say, as Alderson2 does, that our book ‘frames children as property for adults to dispose of as they see fit’ (p. 6) is a serious mis-reading of the situation. In many situations, adults are the ethically appropriate decision makers and involving the child beyond their capacities would in fact be irresponsible.

Several chapters in the book critically engage with the ZPD concept’s potential in relation to older children or adolescent patients, but these explorations highlight the limits of the concept in this context. There is an important ethical puzzle here. Clearly the views of patients matter, and are definitive in some cases; the challenge is identifying the cases in which children and young people’s views should be definitive. In such cases, we would suggest that the ZPD is no longer the appropriate ethical tool for thinking about the case as it is designed to help clinicians think through conflicts with parents specifically.

In our book, the ZPD concept is explicitly framed as one ethical tool among many. We write that ‘[t]he ZPD is a crucial tool in the clinicians’ conceptual toolkit, but given the complexity of clinical practice, other supplementary tools will also be necessary and important in their thinking’ (McDougall et al.,5 p. 23). Alderson2 critiques the concept of the ZPD on the basis of ‘its silence on children’s views, rights and wishes’ (p. 6), overlooking our clearly stated position that ‘[w]e see the ZPD as a key part of clinicians’ ethical decision-making in these situations, but it is not the whole story’ (McDougall et al.,5 p. 22).

Alderson fundamentally misinterprets our project. Our focus on the clinician–parent intersection is aiming to understand one important piece of the puzzle, and to assist health professionals to think and act ethically. It is crucial to understand that ethical decisions are always made from a particular standpoint, by an agent who has a particular place and role in the situation. The agent’s position is relevant to their decision-making and ethical obligations. The zone of parental discretion is not incompatible with valuing children’s rights and views; its focus is a different element of a complex whole.

Zooming out

Our book focuses on two aspects of the intersecting circles in Figure 1: parental autonomy and clinicians’ integrity. Alderson focuses on the circle encompassing the child’s views, rights and wishes. The ZPD is an example of zooming in on the issue of conflicts between doctors and parents, and of identifying a conceptual framework to support and encourage clinicians discussing this aspect of paediatric ethics. Alderson similarly focuses on a particular perspective – that of the child – and gives a detailed overview of the importance of considering children’s views, rights and wishes. Both discussions are worthwhile and useful in building an understanding of paediatric ethics as a whole.

We suggest that acknowledging the value of different types of contributions is crucial to building scholarship in paediatric ethics and ultimately deepening our understanding of this complex ethical landscape. This requires a preparedness to recognise the multitude of perspectives, issues and approaches that characterise this field. While Alderson2 characterises the field simply in terms of a ‘rise and later a fall in respect for children’s views’ (p. 1), she does not do justice to the field of paediatric ethics with its rich, diverse and ultimately useful combination of approaches.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.McDougall R, Delany C, Gillam L. (eds). When Doctors and Parents Disagree: Ethics, Paediatrics and the Zone of Parental Discretion. Sydney: Federation Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderson P. Children’s consent and the zone of parental discretion. Clin Ethics 2017; 12: 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delany C. Conclusion: the ZPD as an ethics education tool In: McDougall R, Delany C, Gillam L. (eds) When Doctors and Parents Disagree: Ethics, Paediatrics and the Zone of Parental Discretion. Sydney: Federation Press, 2016, pp. 244–254. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillam L. The zone of parental discretion: an ethical tool for dealing with disagreement between parents and doctors about medical treatment for a child. Clin Ethics 2016; 11: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDougall R, Gillam L, Gold H. The zone of parental discretion In: McDougall R, Delany C, Gillam L. (eds) When Doctors and Parents Disagree: Ethics, Paediatrics and the Zone of Parental Discretion. Sydney: Federation Press, 2016, pp. 14–24. [Google Scholar]