Abstract

Objectives

To study the available data on the prevalence of atopic diseases and food allergy in children living on the Arabian Peninsula.

Methods

A PubMed search for relevant published articles was conducted using the following search terms singly or in combination: “atopy,” “atopic disease,” “atopic disorder,” “International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood,” “ISAAC,” “asthma,” “allergic rhinitis,” “eczema,” and “food allergy” in combination with the names of countries of the Arabian Peninsula (Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and Yemen). The search captured studies published up to December 2017.

Results

A total of 8 publications reporting prevalence rates of any type of atopic disease in children in 7 countries of the Arabian Peninsula were retrieved. The prevalence of all atopic disorders was comparable between countries of the Arabian Peninsula. The overall prevalence of asthma ranged from 8 to 23%, while the reported prevalence of eczema ranged from 7.5 to 22.5%. There was great variation in the prevalence rates of rhinoconjunctivitis, which ranged from 6.3 to 30.5%. The prevalence of food allergy (8.1%) was reported for 1 country only, the United Arab Emirates.

Conclusions

The reported overall rates of atopic disease in countries of the Arabian Peninsula are comparable to those reported in other industrialized countries. This is probably related to the good economic status in the region, which is reflected in the living standards and lifestyle. Further, genetic factors, such as factors related to gene polymorphism, and the high rate of consanguinity in the region may contribute to the higher prevalence of atopic diseases.

Keywords: Atopic disease, Arabian Peninsula, Asthma, Eczema, Food allergy

Significance of the Study

Studying the prevalence of atopic diseases and food allergy is important. The reported overall rates of these diseases in countries of the Arabian Peninsula are comparable to those reported in other industrialized countries. Health authorities should provide resources to facilitate early diagnosis and consider preventive measures which may help reduce economic burden.

Introduction

There has been a dramatic rise in the prevalence of atopic diseases in both developed and developing countries, especially in children. The phase III International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) reported a worldwide increases in the prevalence of atopic disorders over results obtained in the phase I study [1]. This report showed an increase in symptoms of eczema which was greatest in children aged 6–7 years compared to asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and compared to incidences in other age groups.

Atopic diseases are closely related. The manifestations may present in a characteristic sequence in children that has been named the atopic or allergic march [2]. Although the atopic march is highly controversial and only a minority of patients follow this march [3], the first signs of atopic diseases are usually food allergy and atopic dermatitis. As these signs of atopic disease are often observed in the first 3 years of life and are thought to be related to the maturation of the immune system [2]. Symptoms may persist over years or decades and often abate spontaneously with age. Having one atopic disorder is considered a risk factor for the development of a second atopic disorder. However, sequential appearance of atopic disorders is not usually because one disorder causes another, but rather because certain individuals exhibit atopic disorders which are influenced by sequential exposure to environmental factors [4].

The causes of atopic disorders include genetic and nongenetic factors. Some debate exists as to whether or not lifestyle, including socioeconomic status, and environmental pollutants play a role in the development of atopic disorders in children [5, 6]. A subanalysis of da ta from the ISAAC phase I study showed a weak rela tionship between environmental variables and reported symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema [7]. In addition to an increase in the prevalence of food allergy, their severity and complexity are increasing worldwide [5, 8]. Approximately 8% of children younger than 3 years may be affected by food allergy, with prevalences in children with eczema estimated to be as high as 30% [4]. Symptoms of cow's milk allergy are often apparent before 1 month of age, although tolerance may be evident in approximately half of children by 3 years and in 66% by 5 years [9].

Individual and family quality of life may be negatively affected in families with a child with multiple food allergy and coexisting allergic conditions such as eczema, rhinoconjunctivitis, or asthma. On a broader level, these conditions can have a relevant impact on healthcare economics. There are little available data on the prevalence of atopic disorders and food allergy in children living on the Arabian Peninsula. This paper aimed to study the available data on the prevalence of atopic diseases and food allergy in this region.

Methods

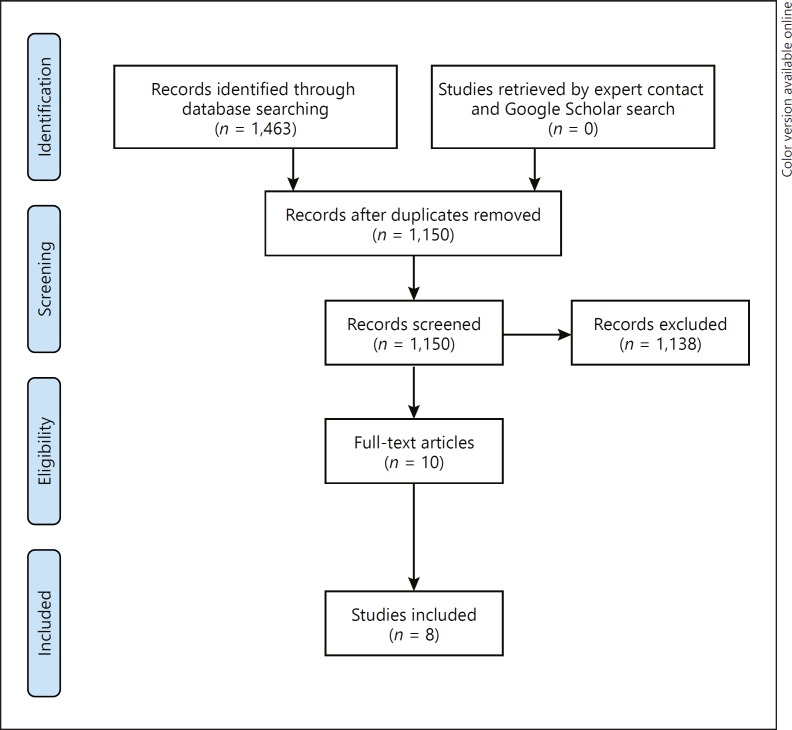

We conducted this systematic review according to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [10]. A PubMed search for articles of relevance to the prevalence of atopic disease in children in countries of the Arabian Peninsula was conducted (Fig. 1). The following search terms were used either singly or in combination: “atopy,” “atopic disease,” “atopic disorder,” “International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood,” “ISAAC,” “asthma,” “allergic rhinitis,” “eczema,” and “food allergy” in combination with the names of countries of the Arabian Peninsula (Kuwait, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [KSA], and Yemen). The search captured studies published up to December 2017. Data from each of the publications are presented in a descriptive manner.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of information through the different phases of the systematic review.

Results

A total of 8 publications reporting prevalence rates of any type of atopic disease in children in a country of the Arabian Peninsula were found: 1 from the KSA, 2 from the UAE, 2 from Kuwait, 2 from Oman, and 1 from Qatar. No publications reporting the prevalence of atopic diseases in Yemen and Bahrain were found. A brief description of the study design, results, and conclusions from the publications included in this study is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the analysis of the prevalence of atopic disease on the Arabian Peninsula

| Country and reference(s) | Study aims and design | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Al Frayh et al. [14], 2001 | investigate the change in asthma prevalence between 1986 and 1995 in children aged 8–16 years; random selection of participants living in a coastal and inland city; ISAAC-based questionnaire used | n = 2,123 (1986), n = 1,008 (1995); the majority of children with asthma at both time points were aged 8–12 years; significant increase in asthma and allergic rhinitis; no change in eczema; significant increase in asthma if ≥1 family member smoked cigarettes | significant increase over 9 years in prevalence of asthma and allergic rhinitis |

| United Arab Emirates Al-Hammadi et al. [11], 2010 | determine the prevalence of physician-diagnosed food allergy and atopic disorders in children aged 6–9 years; multistage random sampling used; modified ISAAC questionnaire used | n = 397, mean age 7.2 years; significantly higher rate of atopic disorders in children with food allergy | eggs, fruits, and fish main allergens; risk factors included family history and small number of siblings; strong association between food allergy and atopic disorders |

| United Arab Emirates Al-Maskari et al. [27], 2000 | determine the prevalence of asthma, wheeze, hay fever, and eczema in children aged 6–13 years; ISAAC questionnaire used | n = 3,200 | prevalence of asthma and wheeze consistent with prevalence rates in neighboring countries |

| Kuwait Behbehani et al. [12], 2000; Owayed et al. [13], 2008 | estimate the prevalence of asthma and allergic disease; children aged 13–14 years; ISAAC questionnaire used; phase I conducted 1995–1996; phase III conducted 2001–2002 | n = 3,110 (phase I), n = 2,882 (phase III); prevalence of asthma and respiratory symptoms higher in boys than girls | physician-diagnosed asthma and eczema rates unchanged; physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis increased significantly |

| Oman Al-Riyami et al. [28], 2003 (ISAAC phase I) | determine the prevalence and severity of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in schoolchildren; ISAAC questionnaire used; conducted in 1995–1996 | n = 3,893 (6–7 years), n = 3,174 (13–14 years); prevalence of diagnoses of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema higher in older children than in younger children; allergic rhinitis and eczema associated with sleep disturbance and limitation of activity | prevalence of symptoms and diagnoses of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema high and associated with significant morbidity and underrecognition |

| Oman Al-Rawas et al. [15], 2008 | data from ISAAC phase I and III analyzed to identify changes in wheeze prevalence and patient-reported asthma | n = 7,067 (phase I), n = 7,879 (phase III); no significant change in self-reported asthma or asthma symptoms; highest prevalence of asthma in eastern region of Sharqiya; increases in wheeze and asthma significant in children aged 6–7 years | regional differences in self-reported asthma symptoms, persistent increases in Sharqiya region; differences possibly due to genetic and/or environmental risk factors; findings suggest underdiagnosis and/or poor recognition of asthma |

| Qatar Janahi et al. [16], 2006 | determine asthma and allergic disease prevalence; ISAAC used; conducted in 2003–2004 | n = 3,283; mean age 9 years; asthma and allergic rhinitis highest in children aged 6–8 years, eczema highest in children aged 12–14 years; high correlation between parental history and disease; 72% with asthma had either allergic rhinitis or eczema | prevalence of asthma, eczema, and allergic rhinitis higher in Qatar than in developing and some developed countries, but similar to rates in neighboring countries |

ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood.

Prevalence of Atopic Disorders

The prevalence of all atopic disorders was comparable between countries of the Arabian Peninsula and highest in Qatar. The overall prevalence of asthma ranged from 8 to 23%. The reported prevalence of eczema ranged from 7.5 to 22.5%. There was great variation in the prevalence rates of rhinoconjunctivitis, which ranged from 6.3 to 30.5% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of asthma, eczema, rhinoconjunctivitis, and food allergy on the Arabian Peninsula

| Country and reference | Prevalence of atopic disorder |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| asthma | eczema | rhinoconjunctivitis | food allergy | |

| Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Al Frayh et al. [14], 2001 | 8% (1986) 23% (1995) | 12% (1986) 13% (1995) | 20% (1986) 25% (1995) | - |

| United Arab Emirates Al-Hammadi et al. [11], 2010 | 13.6% | 8.8% | 6.3% | 8.1% |

| United Arab Emirates Al-Maskari et al. [27], 2000 | 13% | 11% | 14.9% | - |

| Kuwait Behbehani et al. [12], 2000 (ISAAC phase I) |

16.8% (13–14 years) | 17.1% (13–14 years) | 11.3% (13–14 years) | - |

| Kuwait Owayed et al. [13], 2008 (ISAAC phase III) |

15.6% (13–14 years) | 22.2% (13–14 years) | 12.8% (13–14 years) | - |

| Oman Al-Riyami et al. [28], 2003 (ISAAC phase I) |

10.5% (6–7 years) 20.7% (13–14 years) |

7.5% (6–7 years) 14.4% (13–14 years) |

7.4% (6–7 years) 10.5% (13–14 years) |

- |

| Oman Al-Rawas et al. [15], 2008 (ISAAC phase III) |

10.6% (6–7 years) 19.8% (13–14 years) |

- | - | - |

| Qatar | ||||

| Janahi et al. [16], 2006 | 19.8% | 22.5% | 30.5% | - |

ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood.

Prevalence of Food Allergy

The prevalence of food allergy was reported for 1 country, the UAE [11]. In a sample of children aged 6–9 years, the rate of physician-diagnosed food allergy in the UAE was 8.1%. The most common food allergens identified were eggs, fruits, and fish.

Changes in Prevalence in Individual Countries

Two papers used the ISAAC questionnaire to estimate the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases in schoolchildren aged 13–14 years living in Kuwait [12, 13]. A comparison of results obtained from the 1995/1996 study with those obtained from the 2001/2002 study indicated a significant decrease in self-reported symptoms of allergic rhinitis, while the rate of physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis significantly increased over time. While self-reported symptoms of asthma significantly decreased, there was no change over time in the rate of physician-diagnosed asthma. The rates of physician-diagnosed eczema remained unchanged from the 1995/1996 study to the 2001/2002 study.

Using a modified version of the ISAAC questionnaire, Al Frayh et al. [14] compared the prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in a costal versus an inland city in the KSA in 1986 and 1995. In children aged 8–6 years, the rate of asthma increased significantly from 8% in 1986 to 23% in 1995, and the prevalence of allergic rhinitis increased from 20 to 25%. No significant change in the prevalence of eczema was found: 12% in 1986 and 13% in 1995. Using data from the ISAAC phase I and phase III studies, Al-Rawas et al. [15] found no change after 6 years in the rate of asthma symptoms and diagnosis in children aged 6–7 or 13–14 years living in Oman. Similarly, a comparison of data from the two study periods showed no relevant change in the prevalence of self-reported symptoms of severe asthma in either age group.

Factors Contributing to Atopic Disorders

In addition to collecting data on the prevalence of atopic disease, the relationship between independent variables, such as environment and genetics, on the presence of atopic disease was reported in some studies. Al Frayh et al. [14] attributed the significant increase in asthma between 1986 and 1995 in the KSA to environmental factors. In 1986, 17% of asthmatic children had one or more family members who smoked cigarettes compared to 35% in 1995. In 1986, 14% of children with asthma were living in homes with pets compared to 34% in 1995. In Qatar, Janahi et al. [16] found a high correlation between parental history of asthma and the occurrence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in their children.

A few reports have described the genetic predisposition to asthma on the Arabian Peninsula (Table 3). Polymorphisms in the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRIβ) in the Kuwaiti population and in IL-13, STAT-6, and the IL-4 receptor alpha subunit (IL-4Rα) in the Saudi population were associated with an increased risk of developing asthma [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. In an evaluation of genetic disposition to food allergy in the UAE, Al-Hammadi et al. [11] found that children with fewer siblings and with a family history of food allergy were more likely to have food allergy themselves.

Table 3.

Gene polymorphism and predisposition to asthma on the Arabian Peninsula

| Country | Gene | Variant | Disease associatio | Refern ence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kuwait | FceRIß | Leu181/Leu183 | yes | 17 |

| IL-4 | C590T | no | 18 | |

| Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | IL-13 | rs20541 | yes | 19 |

| rs1295686 | yes | |||

| rs1800925 | no | |||

| rs762534 | no | |||

| STAT-6 | rs324011 | yes | 20 | |

| (C2892T) | rs324015 | no | ||

| IL-4Ra | rs1805010 | yes | 21 | |

| rs1801275 | yes | |||

| GLCCI1 | rs37972 | no | 22 | |

| rs37973 | no | |||

Discussion

Research on the epidemiology of atopic diseases in children has helped provide a better understanding of the occurrence of these disorders. Previously, the lack of a standardized method to collect epidemiological data presented an obstacle to identifying the actual prevalence or changes in disease prevalence. Implementation of the ISAAC questionnaire, however, has greatly enhanced the quality of information collected and allowed a comparison of the prevalence of atopic disorders between different age groups as well as between populations in different countries.

While many of the publications included in this review used the ISAAC questionnaire or a modified version thereof as an instrument of data collection, differences in methodology make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the prevalence of atopic disorders on the Arabian Peninsula. It is also important to highlight the limitation of the ISAAC criteria for atopic dermatitis, which may also include allergic contact dermatitis and possibly also other less frequent pruritic dermatoses [23].

There were variations in the prevalence of atopic diseases among populations from different ethnicities and geographic areas. This could be attributed to differences in both genetic and environmental factors. The reported overall rates of atopic disorders in countries of the Arabian Peninsula are closer to those reported in industrialized countries than the rates in developing countries. For example, the rates of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in children aged 6–7 years living in Canada were 20, 12.9, and 17%, respectively [1]. By comparison, the rates of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in children aged 6–7 years living in India were 6.8, 3.9, and 2.4%, respectively, much lower than the rates reported in children from the Arabian Peninsula [1].

It can be assumed that the good economic status in the Arabian Peninsula region is reflected in the living standards and lifestyle. While greater affluence may have a positive impact on overall health, increased industrialization with subsequent increased exposure to pollutants may adversely impact the prevalence of some atopic diseases. An ecological analysis of the ISAAC phase I data revealed an association between economic development and changes influencing asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema [7]. The increase in plantation and agricultural activities using nonnative trees and seeds may possibly contribute to the prevalence of atopic diseases in this region. In addition, countries of the Arabian Peninsula experience extremely hot weather, and due to changes in lifestyle, children are spending less time outdoors, which results in decreased exposure to ultraviolet rays. This may play a role in the relatively high prevalence of eczema [24]. Other possible contributing factors might include changes in health services with less exposure to microbial agents, widespread use of antibiotics and vaccines, and an increased awareness among healthcare professionals about atopic diseases. Further, genetic factors, such as factors related to gene polymorphism, and the high rate of consanguinity in the region may also play a role in the higher prevalence of atopic diseases.

Unfortunately, there is only 1 report on the prevalence of food allergy on the Arabian Peninsula. The prevalence of food allergy in one city in the UAE is similar to that reported for children in the US [25]. Without comparable data from other countries on the Arabian Peninsula, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions.

While this evaluation of available studies provides a basis for the assessment of the prevalence of atopic diseases in children on the Arabian Peninsula, a more systematic approach to gathering relevant literature might yield data of benefit in identifying not only the scope of the problem, but also information on allergen exposure, diet, air pollution, and genetic factors which are known to be associated with the development of atopic disorders or could exacerbate the manifestations of these disorders [7]. More objective data, such as better characterization of type and severity of asthma and confirmation of sensitization by either skin or specific IgE testing, are also needed to obtain a true picture of the scope of the problem of atopic disease in the region. Performing epidemiological studies on atopic diseases in Bahrain and Yemen is also important. These two countries have a somewhat lower economic status compared to the other countries assessed in this study, although their populations share the same genetic pool. Accordingly, such studies will help determine the effect of lifestyle versus genetic factors on the development of atopic diseases [26]. Since the diagnosis of food allergy is usually associated with atopic diseases and because of the likely role that food allergy plays in the later development of atopic disorders leading most experts to conclude that food allergy is a first step in the allergic march, studying the prevalence and pattern of food allergy in the region is highly recommended.

Conclusions

Studies evaluating both atopic disorders and food allergy could yield critical information to support intervention for the prevention of atopic disorders and for strategies to guide the diagnosis and management of these disorders. Implementation of strategies to facilitate patients' access to allergy services, introduction of modern diagnostic and therapeutic options, and physician education about atopic diseases are among the major challenges to provide better care to patients suffering from these diseases.

Disclosure Statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CKW, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ker J, Hartert TV. The atopic march: what's the evidence? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:34–289. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60526-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoos AM, Chawes BL, Rasmussen MA, Bloch J, Bønnelykke K, Bisgaard H. Atopic endotype in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:844–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cochrane S, Beyer K, Clausen M, Wjst M, Hiller R, Nicoletti C, et al. Factors influencing the incidence and prevalence of food allergy. Allergy. 2009;64:1246–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kay AB. Allergy and allergic diseases. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:30–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallit S, Raherison C, Malaeb D, Hallit R, Kheir N, Salameh P. The AAA risk factors scale: a new model to screen for the risk of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis in children. Med Princ Pract. 2018 doi: 10.1159/000490704. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asher MI, Stewart AW, Mallol J, Montefort S, Lai CK, Aït-Khaled N, et al, ISAAC Phase One Study Group Which population level environmental factors are associated with asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema? Review of the ecological analyses of ISAAC Phase One. Respir Res. 2010;11:8. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawankar R, Canonica GW, Holgate ST, Lockey RF. World Allergy Organization White Book on Allergy 2011–2012: Executive Summary. http://www.worldallergy.org/publications/wao_white_book.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyano Martínez T, García-Ara C, Díaz-Pena JM, Muñoz FM, García Sánchez G, Esteban MM. Validity of specific IgE antibodies in children with egg allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1464–1469. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Hammadi S, Al-Maskari F, Bernsen R. Prevalence of food allergy among children in Al-Ain City, United Arab Emirates. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;151:336–342. doi: 10.1159/000250442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behbehani NA, Abal A, Syabbalo NC, Abd Azeem A, Shareef E, Al-Momen J. Prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in 13- to 14-year-old children in Kuwait: an ISAAC study. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:58–63. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owayed A, Behbehani N, Al-Momen J. Changing prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases among Kuwaiti children. An ISAAC study (phase III). Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:284–289. doi: 10.1159/000129607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Frayh AR, Shakoor Z, Gad El Rab MO, Hasnain SM. Increased prevalence of asthma in Saudi Arabia. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86:292–296. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)63301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Rawas OA, Al-Riyami BM, Al-Maniri AA, Al-Riyami AA. Trends in asthma prevalence and severity in Omani schoolchildren: comparison between ISAAC phases I and III. Respirology. 2008;13:670–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janahi IA, Bener A, Bush A. Prevalence of asthma among Qatari schoolchildren: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, Qatar. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41:80–86. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hijazi Z, Haider MZ, Khan MR, Al-Dowaisan AA. High frequency of IgE receptor Fc epsilonRIbeta variant (Leu181/Leu183) in Kuwaiti Arabs and its association with asthma. Clin Genet. 1998;53:149–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1998.tb02664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hijazi Z, Haider MZ. Interleukin-4 gene promoter polymorphism (C590T) and asthma in Kuwaiti Arabs. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2000;122:190–194. doi: 10.1159/000024396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halwani R, Vazquez-Tello A, Kenana R, Al-Otaibi M, Alhasan KA, Shakoor Z, et al. Association of IL-13 rs20541 and rs1295686 variants with symptomatic asthma in a Saudi Arabian population. J Asthma. 2017;6:1–9. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2017.1400047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Muhsen S, Vazquez-Tello A, Jamhawi A, Al-Jahdali H, Bahammam A, Al Saadi M, et al. Association of the STAT-6 rs324011 (C2892T) variant but not rs324015 (G2964A), with atopic asthma in a Saudi Arabian population. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:791–795. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Muhsen S, Vazquez-Tello A, Alzaabi A, Al-Hajjaj MS, Al-Jahdali HH, Halwani R. IL-4 receptor alpha single-nucleotide polymorphisms rs1805010 and rs1801275 are associated with increased risk of asthma in a Saudi Arabian population. Ann Thorac Med. 2014;9:81–86. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.128849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Muhsen S, Vazquez-Tello A, Jamhawi A, Al-Dosari MS, Mahboub B, Iqbal N, et al. rs37972 and rs37973 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the glucocorticoid-inducible 1 gene are not associated with asthma risk in a Saudi Arabian population. J Asthma. 2015;52:115–122. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.955189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Czarnobilska E, Obtulowicz K, Dyga W, Spiewak R. A half of schoolchildren with “ISAAC eczema” are ill with allergic contact dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1104–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thyssen JP, Zirwas MJ, Elias PM. Potential role of reduced environmental UV exposure as a driver of the current epidemic of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawankar R. Allergic diseases and asthma: a global public health concern and a call to action. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1939-4551-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, Smith B, Kumar R, Pongracic J, et al. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e9–e17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Maskari F, Bener A, Al-Kaabi A, Al-Suwaidi N, Norman N, Brebner J. Asthma and respiratory symptoms among school children in United Arab Emirates. Allerg Immunol (Paris) 2000;32:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Riyami BM, Al-Rawas OA, Al-Riyami AA, Jasim LG, Mohammed AJ. A relatively high prevalence and severity of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic eczema in schoolchildren in the sultanate of Oman. Respirology. 2003;8:69–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]