Abstract

Targeted therapies and immunotherapies are associated with a wide range of dermatologic adverse events (dAEs) resulting from common signaling pathways involved in malignant behavior and normal homeostatic functions of the epidermis and dermis. Dermatologic toxicities include damage to the skin, oral mucosa, hair, and nails. Acneiform rash is the most common dAE, observed in 25–85% of patients treated by epidermal growth factor receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitors. BRAF inhibitors mostly induce secondary skin tumors, squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthomas, changes in pre-existing pigmented lesions, as well as hand-foot skin reactions and maculopapular hypersensitivity-like rash. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) most frequently induce nonspecific maculopapular rash, but also eczema-like or psoriatic lesions, lichenoid dermatitis, xerosis, and pruritus. Of the oral mucosal toxicities observed with targeted therapies, oral mucositis is the most frequent with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, followed by stomatitis associated to multikinase angiogenesis and HER inhibitors, geographic tongue, oral hyperkeratotic lesions, lichenoid reactions, and hyperpigmentation. ICIs typically induce oral lichenoid reactions and xerostomia. Targeted therapies and endocrine therapy also commonly induce alopecia, although this is still underreported with the latter. Finally, targeted therapies may damage nail folds, with paronychia and periungual pyogenic granuloma distinct from chemotherapy-induced lesions. Mild onycholysis, brittle nails, and a slower nail growth rate may also be observed. Targeted therapies and immunotherapies often profoundly diminish patients’ quality of life, which impacts treatment outcomes. Close collaboration between dermatologists and oncologists is therefore essential.

Key Points

| Although dermatologic toxicities with systemic cancer therapies are very frequent, a minority of cancer patients are referred to a dermatologist during their therapy. |

| Dermatologic toxicities related to targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors profoundly diminish patients’ quality of life, which impacts adherence to the treatment, jeopardizing its success and thus patient progression-free survival. Closer collaboration between dermatologists and oncologists is essential. |

Introduction

An estimated 14 million individuals were diagnosed with cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancers) worldwide in 2012 (http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home), of which more than 10 million received systemic anticancer therapy. Anticancer therapies including targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are designed to target alterations in DNA repair pathways and defects in the immune system to treat cancer. However, those treatments target signaling pathways involved in both cell malignant behavior and normal homeostatic functions of the epidermis and dermis. Consequently, although intended to treat cancer, targeted therapies and immunotherapies also damage the skin and its appendages, resulting in the consistent report of cutaneous, oral mucosal, hair, and/or nail toxicities in nearly all patients, irrespective of the pathway being blocked. Those dermatologic toxicities are discussed herein, as well as strategies aimed at reducing the burden placed on patients and improving their quality of life (QoL).

Skin Toxicities

Cutaneous toxicities of targeted therapies and immunotherapies profoundly diminish patient QoL, and impairment appears to be unexpectedly more severe in patients treated with a targeted therapy than with chemotherapy (total score 41.7 vs. 32.8; p = 0.02) [1]. The emotional component is the most significantly affected domain (50.0 vs. 38.1; p = 0.02), followed by symptoms and pain, indicating that patients experience a sense of loss of privacy due to their inability to hide their cancer.

The management of skin toxicities is therefore critical to improving cancer patient outcomes. However, compared with dermatologists, oncologists more often overestimate the severity of dermatologic adverse events (dAEs) [2] and are more prone to discontinuing cancer therapy as a result of skin toxicities, hence reducing patient access to a potential life-saving treatment. An interdisciplinary collaborative approach between dermatologists and oncologists is therefore essential to caring for patients receiving anticancer therapies.

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitor- and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Inhibitor-Induced Toxicities

Acneiform Rash

Acneiform rash has been instrumental in drawing attention to cancer therapy-associated skin toxicities in the oncology community. This dAE develops in the majority of patients treated with inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor (EGFRI) and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase inhibitor (MEKI) signaling pathways, while xerosis and pruritus are less frequently observed [3].

In patients on EGFRIs, rash was described with incidences ranging from 25 to 85% for all-grade toxicities and from 1 to 10% for grade 3 [4–6]. Skin rash typically appears within 2–4 weeks and is characterized by papules and pustules, extreme itchiness, and severe pain, with spontaneous bleeding of the lesions therefore profoundly impairing patients’ QoL (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Clinical presentation of grade 3 acneiform rash on the trunk of a patient treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab

Acneiform rash induced by MEKIs presents with a distinguishable rash characterized by papules and pustules on the face, chest, upper back, and scalp. A higher incidence of rash was shown on trametinib than chemotherapy (57% vs. 10%) [7].

The pathophysiology of EGFRI- and MEKI-induced rash remains poorly understood. Experimental and immunohistological findings showed that epidermal keratinocytes were able to produce chemokines CCL2, CCL5, CCL27, and CXCL14 in response to EGFRIs and that inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus colony formation by the supernatant from EGFRI-treated epidermal keratinocytes was markedly decreased [8]. Furthermore, clinical studies with EGFRIs have reported cutaneous inflammation, and altered immunosuppression, as well as neutrophil accumulation, epidermal keratinocyte proliferation, and erosion of the stratum corneum [9, 10]. Those observations, together with the fact that about a third of patients develop secondary dermatological infections at the site of toxicities during EGFR- or MEK-targeted therapy in the form of impetigo, cellulitis, or erysipelas [11], suggest a key role played by inflammation, immunosuppression, and superinfection in the pathophysiology of EGFRI-induced acneiform rash.

Consequently, the prophylactic use of antibiotics and topical corticosteroids to reduce the incidence of dermatological toxicities was evaluated in phase II studies. Results from one of these studies showed a profound reduction in the incidence of grade ≥ 2 dAEs in patients given the EGFRI panitumumab who received a 6-week prophylactic treatment with the oral antibiotic doxycycline, topical corticosteroids, sunscreen, and moisturizers versus a curative treatment after development of skin toxicities (29% vs. 62%, odds ratio [OR] = 0.3 [95% confidence limit 0.1–0.6]), with a five-fold decreased incidence of pruritus and pustular rash, and even a completely abolished paronychia [10]. Similar results were observed in dacomitinib-treated patients given oral doxycycline [12]. Prophylaxis with topical dapsone gel also seems to be a promising treatment [13]. Prescription of antibiotics upon initiation of EGFRIs or MEKIs should be recommended in cancer patients as well as the bacterial culture being performed when secondary infection is suspected to determine the strain involved.

Finally, two phase III studies suggested that, contrary to what might be expected, combination therapies such as those with a MEKI and a BRAF inhibitor (BRAFI) [14, 15] may improve patient survival without necessarily increasing the incidence of MEKI-induced dAEs.

BRAF Inhibitor-Induced Toxicities

Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Approved for the treatment of advanced metastatic melanoma [16], BRAFIs can reversibly bind to the mutant BRAFV600E to inhibit the downstream extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling. However, in wild-type cells or cells with UV-induced mutant RAS, binding of BRAFIs results in heterodimerization of BRAF kinases, which activates the downstream signaling and thus induces opposite effects [17, 18]. As a consequence of this paradoxical activation, approximately 20% of patients treated with BRAFI monotherapy will develop secondary skin tumors and other hyperproliferative lesions, such as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and keratoacanthomas (KA) [14, 16, 18]. Metastatic spread has not been reported from those secondary cancers and there is usually no need for dose modification or treatment interruption [19]. The vast majority of newly appearing proliferative lesions are benign [20], except those harboring RAS mutations, especially HRAS, which have a malignant phenotype [21]. Patients with a family history of skin cancer treated with vemurafenib or melanoma have a higher risk of developing SCC or KA [20]. Interestingly, concomitant treatment with MEKIs decreases the incidence of skin toxicities compared with a BRAFI alone by blocking the MAP kinase pathway downstream [14, 15].

Changes in Melanocytic Lesions

Modifications in pre-existing pigmented lesions, with changes in color and number of globules, have also been reported early after vemurafenib treatment initiation in about 50% of melanocytic lesions, but their incidence is lower than that of SCC under vemurafenib [22, 23]. Although alarming at first, biopsies performed on lesions found suspicious after evaluation by dermoscopy revealed that the incidence of subsequent primary melanoma after vemurafenib treatment (about 1.2% of the modified melanocytic lesions) was what we would expect in any patient following a first primary melanoma not treated with a BRAFI. Therefore, the occurrence of secondary vemurafenib-associated melanoma should not cause a great deal of concern, but requires close clinical monitoring [22]. Interestingly, the addition of a MEKI to vemurafenib treatment resulted in marked depigmentation and complete regression of suspicious lesions after 3 months of combined therapy [23] and, typically, most of these BRAF-induced hyperproliferative melanocytic lesions are non-malignant. Such pigmented lesions are more frequent in the extremities and in patients with a history of melanoma, but also had a higher degree of atypia, hyperpigmentation, pagetoid spread, and upregulated cyclin D1 expression indicative of increased cell proliferation than control nevi [24].

Hand–Foot Syndrome (Hyperkeratotic Lesions)

Benign hyperkeratotic, thick, occasionally painful lesions can be observed on the palms and soles of patients treated with dabrafenib, potentially impacting their QoL and ability to walk [25]. The incidence rate of about 30% with vemurafenib or dabrafenib is decreased to 6–10% upon addition of a MEKI [25, 26]. Preventive and supportive care entails the use of keratolytic agents (salicylic acid, urea) or topic lidocaine for grade ≥ 2 toxicity and, in some cases, manual paring performed by a podiatrist. Other hyperkeratotic lesions, including verrucal keratoses, keratosis–pilaris rash or contact hyperkeratosis, may also occur with BRAFI when used as monotherapy.

Maculopapular ‘Hypersensitivity-Like’ Rash

A very severe grade 3 maculopapular or morbilliform hypersensitivity-like rash has been documented in patients with advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib who received prior immunotherapy with ipilimumab [27] or nivolumab, as activation of the immune system and inflammation persist even after treatment completion [28]. This rash is likely to be a non-allergic, non-specific inflammatory reaction, as no drug-specific T cells were found in patients with this dAE [29]. Therefore, when the switch to another BRAFI at the first warning signs of hypersensitivity reaction is impossible, an alternative option may be to discontinue therapy and prescribe oral corticosteroids until resolution. Further reinstatement of the treatment will not always trigger the same reaction.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Skin Toxicities

Immune checkpoints have a critical role in maintaining normal immunologic homeostasis by downregulating T cell activation. Therapeutic blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4)/programmed death-1 (PD-1) receptors or PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) leads to constitutive CD4 +/CD8 + T cell activation, shifting the immune system toward antitumor activity [30]. Because of this unique mechanism of action, ICIs have a specific safety profile referred to as immune-related adverse events (irAEs) which affect virtually all organs in the body [31].

Cutaneous toxicities are the most frequent irAEs, affecting 40% of patients [32]; they occur within the first 4–8 weeks and can be long-lasting. A non-specific maculopapular rash is most commonly reported (Fig. 2), with a frequency ranging from 14 to 40% depending on the drug and whether it is used in combination or alone [33]. Subsets of patients also present eczema-like or psoriatic lesions [34] while others develop lichenoid dermatitis [35, 36] in response to PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. Lichenoid rash in patients treated with ICIs is very similar to idiopathic lichen planus, except for a slightly increased abundance of CD163-positive cells indicating a macrophage–monocyte lineage [36].

Fig. 2.

Clinical presentation of grade 2/3 non-specific maculopapular rash on the trunk of a patient treated with a programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor

Other bothersome irAEs include xerosis and pruritus with secondary excoriations, which may be associated with a rash. Although all-grade pruritus is frequent (10–30% of patients) [33, 37], it remains underreported and underdiagnosed. As this irAE has a profound negative impact on patients’ QoL, it is currently the focus of intense investigation. Treatment includes high-potency corticosteroids or γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonists along with antihistamines for grade ≥ 2 toxicities.

Other clinical presentations of irAEs include autoimmune bullous disorders such as BP180/230-positive bullous pemphigoid (BP) [38] in < 1% of patients, as well as worsening or de novo appearance of autoimmune dermatosis such as psoriasis [39]. Rarely, life-threatening conditions such as grade 4 Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)-like eruptions may develop; these warrant prompt recognition, discontinuation of treatment, and aggressive management [40]. Vitiligo is also commonly described in patients treated for melanoma [41, 42]. Patients are usually not bothered by the disease as its impact on their social life is minor. Interestingly, however, patients who develop cutaneous reactions in response to pembrolizumab [43, 44] or rash or vitiligo when treated with nivolumab [45] have an overall increased survival and better outcomes than those who do not, suggesting a better response to immunotherapy. ICI-treated patients must therefore receive proper counselling as part of a supportive care regimen to help them cope with dermatological toxicities and ensure that QoL is maintained.

Oral Mucosal Toxicities

Oral Mucosal Toxicities of Targeted Therapies

Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Inhibitor-Associated Stomatitis

Oral mucositis is the most frequent dose-limiting toxicity observed with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (everolimus, temsirolimus, and sirolimus). It is characterized by aphthous-like lesions which are very different from the ones induced by chemo- and radiotherapy. These single or multiple well-circumscribed, round, superficial, painful ulcers are solely localized in the non-keratinized mucosa and occasionally surrounded by an erythematous halo. mTOR inhibitor-associated stomatitis occurs in about 30% of patients treated with monotherapy, mostly within the first 8 weeks of treatment; 5% are grade ≥ 3 toxicities [46]. In addition, although usually self-limited, lesions can be very painful [47].

Early patient education is critical to prevent repeated trauma and avoid aggressive treatment modalities to the oral mucosa [47, 48]. Close follow-up by an odontologist is also essential. Early management consists of the promotion of good oral hygiene, including mouth washing with normal saline, sterile water, or sodium bicarbonate. A wide range of treatments can also be used, including low-level laser therapy, also known as soft laser therapy, pain management, and morphine mouthwash, but the first line of therapy should include topical corticosteroids [47, 48]. The SWISH trial demonstrated the efficacy of topical corticosteroids in post-menopausal women treated with everolimus and exemestane who prophylactically used dexamethasone-based mouthwash starting on the first day of treatment [49]. After 8 weeks, the incidence of grade ≥ 2 stomatitis was only 2% compared with 33% in the historical BOLERO-2 (Breast Cancer Trials of Oral Everolimus-2) study (p < 0.0001), with no grade 3 toxicity.

Multikinase Angiogenesis and HER Inhibitor-Associated Stomatitis

About 25% and 15% of patients treated with multikinase angiogenesis inhibitors (sorafenib, sunitinib, cabozantinib, pazopanib, etc.) and EGFRIs (erlotinib, gefitinib) develop stomatitis, respectively. However, the all-grade incidence appears to be significantly higher with the newly developed pan-HER inhibitors (dacomitinib, afatinib) [47].

Similar well-demarcated ulcerations on non-keratinized mucosa may also occur, which are roughly similar to aphthous-like lesions induced by mTOR inhibitors [47]. However, they are most often limited and of low grade, and patients generally report non-specific stomatitis with diffuse mucosal hypersensitivity/dysesthesia and dysgeusia, sometimes associated with erythema or painful burning mouth (mucosa inflammation). Rapid development after treatment initiation and gradual disappearance is noted.

Other Oral Toxicities with Targeted Therapies

Geographic tongue has been described in association with bevacizumab or multikinase angiogenesis inhibitors [50]. Although geographic tongue does not require any treatment, it is essential to reassure the patient, and clinicians should avoid prescribing ineffective antifungal agents.

As described in Sect. 2.2.3, reactional hyperkeratotic lesions are also observed in both keratinized and non-keratinized areas, as well as occasional SCC occurring in patients treated with BRAFIs as monotherapy [51]. Vemurafenib or dabrafenib in monotherapy results in oral mucosal hyperkeratosis within the first weeks of treatment, which noticeably regresses upon addition of MEKIs (cobimetinib, trametinib), as shown for skin toxicities [52].

Oral lichenoid reactions are frequently observed in patients treated with the first-generation BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib and are characterized by a combination of reticular striae with symptomatic ulcerative, erosive, or atrophic lesions [53]. Often underestimated, these lesions can be isolated or associated with nail or skin reactions and regular follow-up is recommended. Of note, these lesions have not been described with the new-generation BCR-ABL TKIs nilotinib, dasatinib, and bosutinib. Finally, blue–gray–black asymptomatic hyperpigmentation of the hard palate has sometimes been reported in response to imatinib, similar to that induced by antimalarial agents [54].

Oral Mucosal Toxicities of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Besides skin reactions, ICIs may also induce oral mucosal injuries. Oral lichenoid reactions are typically described with ICIs targeting PD-1/PD-L1, with reticulated white streaks and papular, plaque-like, ulcerative, or atrophic/erythematous lesions (Fig. 3). Patients usually remain asymptomatic [35, 55]. These lesions are reversible and can be treated with topical corticosteroids while maintaining immunotherapy at the same dose [55]. Histological analysis shows patchy and/or florid lichenoid interface dermatitis in the upper lamina propria and predominantly CD4/CD8-positive band-like T cell infiltrate.

Fig. 3.

Oral lichenoid reaction induced by immune checkpoint inhibitor anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) nivolumab

Xerostomia, the second most common oral toxicity induced by ICIs (6% of patients) is occasionally associated with dysgeusia and occasionally can be very severe [47]. The occurrence of Sjögren’s syndrome has been seldom reported. Xerostomia may represent the most burdensome adverse effect induced by immunotherapy and patients with xerostomia need to be managed properly. Xerostomia has also been described with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, as well as targeted therapies with human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) TKIs, multi-targeted angiogenesis inhibitors (4–12%), mTOR inhibitors (6%), and new selective fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitors [47].

Hair Toxicities

Hair toxicities caused by systemic therapies are rapidly growing in importance as patients survive longer and QoL is becoming a key component of cancer treatment.

Targeted Therapy and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Alopecia

Alopecia is commonly reported in patients treated with BRAFIs (23.7% and 18.9% of patients treated with vemurafenib and dabrafenib, respectively) and MEKIs (trametinib, 13.3%), with a decreased incidence with combined BRAFI/MEKI therapy (vemurafenib/cobimetinib, 13% and dabrafenib/trametinib, 6%) [56, 57]. Management of this type of alopecia may involve use of minoxidil. Furthermore, evidence shows that PD-L1 is expressed on the hair follicle dermal sheath cup cells [58]. Therefore, an estimated 1–2% of patients treated with ICIs develop either alopecia areata (spot baldness) or alopecia universalis with CD4 and scant CD8-positive T cells [59].

Endocrine Therapy and Alopecia

While more than half of women with breast cancer report alopecia as the most traumatic adverse event during treatment, hormone therapy-induced alopecia (HTIA) is still largely underreported, with only 6% of studies of tamoxifen reporting it [60]. In a meta-analysis of 35 studies (n = 13,415 patients) the incidence of all-grade HTIA ranged from 0% with anti-androgen therapies to 25% with selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), corresponding to an overall incidence of 4.4% [60]. In a retrospective study of the data for 112 patients treated with SERMs/aromatase inhibitors, HTIA was most often (92%) characterized by an androgenic alopecia pattern and low severity grade [61]. Tamoxifen-induced alopecia is characterized by a reduction in the number of hair follicles [62]. Microscopically, hair looks more brittle and breaks more easily due to estrogen production inhibition. Topical minoxidil may provide moderate to significant improvement in most patients (80%) [61].

Nail Toxicities

Nail Toxicities of Targeted Therapies

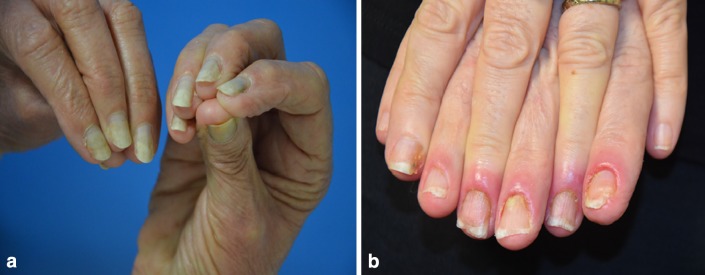

Targeted therapies may cause damage to nail folds, with paronychia and periungual pyogenic granuloma distinct from chemotherapy-induced lesions (Fig. 4a, b) that are mostly observed in the nail plate or the nail matrix. As some patients may receive both treatment types combined, clinicians must be fully informed of differences between chemotherapy and targeted therapy-associated nail toxicities. Paronychia and periungual granulomas are mostly reported in response to EGFRIs, with a 17.2% all-grade toxicity incidence [63], as well as MEKIs and mTOR inhibitors to a lesser extent [64]. Typical lesions, which mostly affect toenails or thumbs, develop slowly after several weeks or months of treatment. Damage typically starts with the development of periungual inflammatory paronychia and can evolve into overgrowing of friable granulation tissue on lateral and/or proximal nail folds, mimicking ingrown nails. Although usually not severe, such lesions can still be very debilitating for the patient, especially when they persist for a long time. Therefore, aggressive strategies must be implemented to help patients cope with these adverse effects. The standard of care for pyogenic granuloma is surgery with partial removal of the nail plate and matrix and physical destruction of the granulation tissue and phenolization [65]. In patients with multiple concomitant lesions, conservative treatment should be prioritized, with supportive oncodermatology while maintaining targeted therapy. In close collaboration with a podiatrist, nail curvature can be corrected if needed. Stretchable tape, liquid nitrogen, a combination of topical corticosteroids and antibiotics, antiseptic soaks, and silver nitrate can also be used [66]. Topical timolol can also be helpful for periungual pyogenic granuloma [67].

Fig. 4.

a Painful onycholysis with docetaxel. b Diffuse paronychia secondary to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy

Patients treated with MEKIs, EGFRIs, and mTOR inhibitors can also develop mild to moderate changes of the nail bed and matrix. These lesions are characterized by mild onycholysis, brittle nails, and a slower nail growth rate [68].

Selective pan-FGFR 1–4 inhibitors are a new class of targeted therapy drugs currently under development for a large range of solid tumors. More than 35% of patients receiving these drugs experience very severe nail toxicities 1–2 months after starting the treatment, with onycholysis, onychomadesis, and nail bed superinfection occurring [69]. These dose-dependent adverse events are similar to taxane-related nail changes. Ibrutinib is a first-in-class, oral covalent inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase that is now approved in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and cell mantle lymphoma. Nail changes including brittle nails (23–67% of patients), onychoschizia, onychorrhexis, and onycholysis have been described. These nail changes become apparent after several months of treatment (median 6–9 months) and are commonly associated with hair changes [70].

Preventive Strategies for Targeted Therapy-Induced Nail Toxicities

To prevent nail adverse effects of targeted therapies, it is recommended that patients be counselled and properly educated with clear and detailed information, and offered appropriate preventive strategies (avoid repeated trauma or friction and pressure on nails and nail beds; use protective gloves; avoid prolonged contact with water; do not use nail polish removers and hardeners; trim nails regularly; apply topical emollients daily and US Food and Drug Administration [FDA]-approved nail lacquers; wear comfortable, wide-fitting footwear and cotton socks) upon initiation of the treatment, particularly for patients treated with EGFRIs [64]. Clinicians should be proactive and aggressive when addressing very severe toxicities such as painful onycholysis or pyogenic granuloma.

Conclusion

Dermatologic toxicities involving the skin, mucosa, hair, and nails are very common and varied in patients treated with targeted therapies and ICIs. These toxicities profoundly diminish patients’ QoL, which impacts their adherence to the treatment, jeopardizing its success and thus patients’ progression-free survival. Closer collaboration between dermatologists and oncologists is therefore essential.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marianne Pons, PhD and Marielle Romet, PhD (Synergy Pharm) who provided medical writing assistance funded by Laboratoires dermatologiques Avène.

Funding

Medical writing assistance was funded by Laboratoires dermatologiques Avène. Mario Lacouture and Vincent Sibaud received funds from Laboratoires dermatologiques Avène for traveling to and presenting at the Entretiens d'Avène Americas conference. MEL is funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Conflict of interest

Vincent Sibaud declares he received fees from Laboratoires dermatologiques Avène, Roche, Novartis, Bayer, Pierre Fabre and BMS. Mario Lacouture declares he has received consulting/advisory fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation, Galderma, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, Abbvie, Inc., Helsinn Healthcare SA, Novocure Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GMBH & Co.KG, F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Allergan Inc., Amgen Inc., E.R. Squibb & Sons, L.L.C., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, EMD Serono, Inc., Astrazeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Genentech, Inc, Leo Pharma Inc, Seattle Genetics, Debiopharm, Lindi, Bayer, Manner SAS, Menlo Ther, Celldex, Lutris, Pierre Fabre, Legacy Healthcare, Roche, Amryt Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, Paxman Coolers, Adjucare, Dignitana, Biotechspert, Parexel, Adgero, Veloce, Berg, US Biotest and research funding from Veloce, Berg, US Biotest, BMS.

Disclosure statement

This article is published as part of a journal supplement wholly funded by Laboratoires dermatologiques Avène.

Contributor Information

Mario Lacouture, Phone: +1 646 361 6536, Email: lacoutuM@mskcc.org.

Vincent Sibaud, Phone: +33 5 31 15 51 69, Email: sibaud.vincent@iuct-oncopole.fr.

References

- 1.Rosen AC, Case EC, Dusza SW, Balagula Y, Gordon J, West DP, et al. Impact of dermatologic adverse events on quality of life in 283 cancer patients: a questionnaire study in a dermatology referral clinic. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14(4):327–333. doi: 10.1007/s40257-013-0021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassel JC, Kripp M, Al-Batran S, Hofheinz RD. Treatment of epidermal growth factor receptor antagonist-induced skin rash: results of a survey among German oncologists. Onkologie. 2010;33(3):94–98. doi: 10.1159/000277656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacouture ME. Mechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(10):803–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drucker AM, Wu S, Dang CT, Lacouture ME. Risk of rash with the anti-HER2 dimerization antibody pertuzumab: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135(2):347–354. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen AC, Wu S, Damse A, Sherman E, Lacouture ME. Risk of rash in cancer patients treated with vandetanib: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(4):1125–1133. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, Nathan P, Garbe C, Milhem M, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):107–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lichtenberger B. M., Gerber P. A., Holcmann M., Buhren B. A., Amberg N., Smolle V., Schrumpf H., Boelke E., Ansari P., Mackenzie C., Wollenberg A., Kislat A., Fischer J. W., Rock K., Harder J., Schroder J. M., Homey B., Sibilia M. Epidermal EGFR Controls Cutaneous Host Defense and Prevents Inflammation. Science Translational Medicine. 2013;5(199):199ra111–199ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nardone B, Nicholson K, Newman M, Guitart J, Gerami P, Talarico N, et al. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical characterization of rash to human epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (HER1) and HER1/2 inhibitors in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(17):4452–4460. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lacouture ME, Mitchell EP, Piperdi B, Pillai MV, Shearer H, Iannotti N, et al. Skin toxicity evaluation protocol with panitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-Emptive Skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(8):1351–1357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.7828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eilers RE, Jr, Gandhi M, Patel JD, Mulcahy MF, Agulnik M, Hensing T, et al. Dermatologic infections in cancer patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(1):47–53. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacouture ME, Keefe DM, Sonis S, Jatoi A, Gernhardt D, Wang T, et al. A phase II study (ARCHER 1042) to evaluate prophylactic treatment of dacomitinib-induced dermatologic and gastrointestinal adverse events in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(9):1712–1718. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belum VR, Marchetti MA, Dusza SW, Cercek A, Kemeny NE, Lacouture ME. A prospective, randomized, double-blinded, split-face/chest study of prophylactic topical dapsone 5% gel versus moisturizer for the prevention of cetuximab-induced acneiform rash. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(3):577–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, Gonzalez R, Kefford RF, Sosman J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(18):1694–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dreno B, Atkinson V, Liszkay G, Maio M, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1867–1876. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, Brandhuber BJ, Anderson DJ, Alvarado R, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464(7287):431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature08833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacouture ME, O’Reilly K, Rosen N, Solit DB. Induction of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas by RAF inhibitors: cause for concern? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(3):329–330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacouture ME, Duvic M, Hauschild A, Prieto VG, Robert C, Schadendorf D, et al. Analysis of dermatologic events in vemurafenib-treated patients with melanoma. Oncologist. 2013;18(3):314–322. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belum VR, Rosen AC, Jaimes N, Dranitsaris G, Pulitzer MP, Busam KJ, et al. Clinico-morphological features of BRAF inhibition-induced proliferative skin lesions in cancer patients. Cancer. 2015;121(1):60–68. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su F, Viros A, Milagre C, Trunzer K, Bollag G, Spleiss O, et al. RAS mutations in cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(3):207–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perier-Muzet M, Thomas L, Poulalhon N, Debarbieux S, Bringuier PP, Duru G, et al. Melanoma patients under vemurafenib: prospective follow-up of melanocytic lesions by digital dermoscopy. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(5):1351–1358. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perier-Muzet M, Boespflug A, Poulalhon N, Caramel J, Breton AL, Thomas L, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of melanocytic nevi changes with combined mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibitors therapy for melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(10):1162–1164. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mudaliar K, Tetzlaff MT, Duvic M, Ciurea A, Hymes S, Milton DR, et al. BRAF inhibitor therapy-associated melanocytic lesions lack the BRAF V600E mutation and show increased levels of cyclin D1 expression. Hum Pathol. 2016;50:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, de Braud F, Larkin J, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):444–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60898-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dreno B, Atkinson V, Liszkay G, Di Giacomo AM, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1248–1260. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30122-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harding JJ, Pulitzer M, Chapman PB. Vemurafenib sensitivity skin reaction after ipilimumab. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):866–868. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1114329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imafuku K, Yoshino K, Ymaguchi K, Tsuboi S, Ohara K, Hata H. Nivolumab therapy before vemurafenib administration induces a severe skin rash. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(3):e169–e171. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klossowski N, Kislat A, Homey B, Gerber PA, Meller S. Successful drug desensitization after vemurafenib-induced rash [in German] Hautarzt. 2015;66(4):221–223. doi: 10.1007/s00105-015-3590-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ott PA, Hodi FS, Robert C. CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: new immunotherapeutic modalities with durable clinical benefit in melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(19):5300–5309. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Champiat S, Lambotte O, Barreau E, Belkhir R, Berdelou A, Carbonnel F, et al. Management of immune checkpoint blockade dysimmune toxicities: a collaborative position paper. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(4):559–574. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, Vigarios E, Mazieres J, Delord JP. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28(4):254–263. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, Hellmann MD, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaunitz GJ, Loss M, Rizvi H, Ravi S, Cuda JD, Bleich KB, et al. Cutaneous eruptions in patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade: clinicopathologic analysis of the nonlichenoid histologic pattern. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(10):1381–1389. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, Leventhal JS, Neckman JP, Girardi M, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed cell death 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(10):1128–1136. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaberg KB, Novoa RA, Wakelee HA, Kim J, Cheung C, Srinivas S, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of lichenoid reactions in patients treated with anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43(4):339–346. doi: 10.1111/cup.12666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ensslin CJ, Rosen AC, Wu S, Lacouture ME. Pruritus in patients treated with targeted cancer therapies: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):708–720. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naidoo J, Schindler K, Querfeld C, Busam K, Cunningham J, Page DB, et al. Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorders with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(5):383–389. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonigen J, Raynaud-Donzel C, Hureaux J, Kramkimel N, Blom A, Jeudy G, et al. Anti-PD1-induced psoriasis: a study of 21 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(5):e254–e257. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villadolid J, Amin A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4(5):560–575. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, Routier E, Boutros C, Cazenave H, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(1):45–51. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai Julia, Belum Viswanath R., Wu Shenhong, Sibaud Vincent, Lacouture Mario E. Pigmentary changes in patients treated with targeted anticancer agents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017;77(5):902-910.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lo JA, Fisher DE, Flaherty KT. Prognostic significance of cutaneous adverse events associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(9):1340–1341. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Daud A, Algazi A, Gubens M, Luna SA, et al. Pembrolizumab cutaneous adverse events and their association with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(11):1206–1212. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, Richards A, Gibney G, Weber JS. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(4):886–894. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rugo HS, Hortobagyi GN, Yao J, Pavel M, Ravaud A, Franz D, et al. Meta-analysis of stomatitis in clinical studies of everolimus: incidence and relationship with efficacy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(3):519–525. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vigarios E, Epstein JB, Sibaud V. Oral mucosal changes induced by anticancer targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1713–1739. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3629-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson DE, Boers-Doets CB, Bensadoun RJ, Herrstedt J. Management of oral and gastrointestinal mucosal injury: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v139–v151. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rugo HS, Seneviratne L, Beck JT, Glaspy JA, Peguero JA, Pluard TJ, et al. Prevention of everolimus-related stomatitis in women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer using dexamethasone mouthwash (SWISH): a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(5):654–662. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hubiche T, Valenza B, Chevreau C, Fricain JC, Del Giudice P, Sibaud V. Geographic tongue induced by angiogenesis inhibitors. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):e16–e17. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vigarios E, Lamant L, Delord JP, Fricain JC, Chevreau C, Barres B, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma and hyperkeratotic lesions with BRAF inhibitors. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(6):1680–1682. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carlos G, Anforth R, Clements A, Menzies AM, Carlino MS, Chou S, et al. Cutaneous toxic effects of BRAF inhibitors alone and in combination with MEK inhibitors for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1103–1109. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sibaud V, Boralevi F, Vigarios E, Fricain JC. Oral toxicity of targeted anticancer therapies [in French] Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2014;141(5):354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fricain JC, Sibaud V. Pigmentations of the oral cavity [in French] Presse Med. 2017;46(3):303–319. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sibaud V, Eid C, Belum VR, Combemale P, Barres B, Lamant L, et al. Oral lichenoid reactions associated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies: clinicopathological findings. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(10):e464–e469. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Belum VR, Marulanda K, Ensslin C, Gorcey L, Parikh T, Wu S, et al. Alopecia in patients treated with molecularly targeted anticancer therapies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2496–2502. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piraccini BM, Patrizi A, Fanti PA, Starace M, Bruni F, Melotti B, et al. RASopathic alopecia: hair changes associated with vemurafenib therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(4):738–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang X, Marr AK, Breitkopf T, Leung G, Hao J, Wang E, et al. Hair follicle mesenchyme-associated PD-L1 regulates T-cell activation induced apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune privilege. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(3):736–745. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zarbo A, Belum VR, Sibaud V, Oudard S, Postow MA, Hsieh JJ, et al. Immune-related alopecia (areata and universalis) in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(6):1649–1652. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saggar V, Wu S, Dickler MN, Lacouture ME. Alopecia with endocrine therapies in patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18(10):1126–1134. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Freites-Martinez A, Shapiro J, Chan D, Fornier M, Modi S, Gajria D, et al. Endocrine therapy-induced alopecia in patients with breast cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(6):670–675. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lindner J, Hillmann K, Blume-Peytavi U, Lademann J, Lux A, Stroux A, et al. Hair shaft abnormalities after chemotherapy and tamoxifen therapy in patients with breast cancer evaluated by optical coherence tomography. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(6):1272–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garden BC, Wu S, Lacouture ME. The risk of nail changes with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(3):400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robert C, Sibaud V, Mateus C, Verschoore M, Charles C, Lanoy E, et al. Nail toxicities induced by systemic anticancer treatments. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):e181–e189. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piraccini BM, Bellavista S, Misciali C, Tosti A, de Berker D, Richert B. Periungual and subungual pyogenic granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(5):941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(3):463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cubiro X, Planas-Ciudad S, Garcia-Muret MP, Puig L. Topical timolol for paronychia and pseudopyogenic granuloma in patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors and capecitabine. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(1):99–100. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Osio A, Mateus C, Soria JC, Massard C, Malka D, Boige V, et al. Cutaneous side-effects in patients on long-term treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(3):515–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Betrian S, Gomez-Roca C, Vigarios E, Delord JP, Sibaud V. Severe onycholysis and eyelash trichomegaly following use of new selective pan-FGFR inhibitors. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(7):723–725. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bitar C, Farooqui MZ, Valdez J, Saba NS, Soto S, Bray A, et al. Hair and nail changes during long-term therapy with ibrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(6):698–701. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]