Abstract

Nanomedicines have evolved into various forms including dendrimers, nanocrystals, emulsions, liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, micelles, and polymeric nanoparticles since their first launch in the market. Widely highlighted benefits of nanomedicines over conventional medicines include superior efficacy, safety, physicochemical properties, and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles of pharmaceutical ingredients. Especially, various kinetic characteristics of nanomedicines in body are further influenced by their formulations. This review provides an updated understanding of nanomedicines with respect to delivery and pharmacokinetics. It describes the process and advantages of the nanomedicines approved by FDA and EMA. New FDA and EMA guidelines will also be discussed. Based on the analysis of recent guidelines and approved nanomedicines, key issues in the future development of nanomedicines will be addressed.

Keywords: Nanomedicines, Pharmacokinetics, Delivery, Guidelines

Introduction

To date, various nanomedicines have been developed and commercially applied in clinical and non-clinical areas. Nanomedicines have shown essential characteristics such as efficient transport through fine capillary blood vessels and lymphatic endothelium, longer circulation duration and blood concentration, higher binding capacity to biomolecules (e.g. endogenous compounds including proteins), higher accumulation in target tissues, and reduced inflammatory or immune responses and oxidative stress in tissues. These characteristics differ from those of conventional medicines depending on physiochemical properties (e.g.; particle surface, size and chemical composition) of the nano-formulations (De Jong and Borm 2008; Liu et al. 2011; Onoue et al. 2014). Efforts to develop these characteristics of nanomedicines are likely to make them available for treatment of specific diseases which have not been efficiently controlled using conventional medicines, because nanomedicines allow more specific drug targeting and delivery, greater safety and biocompatibility, faster development of new medicines with wide therapeutic ranges, and/or improvement of in vivo pharmacokinetic properties (Onoue et al. 2014). Many nanomedicines have been used for the purpose of increasing efficacy and reducing adverse reactions (e.g., toxicity) by altering efficacy, safety, physicochemical properties, and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic properties of the original drugs (Dawidczyk et al. 2014). In particular, higher oral bioavailability or longer terminal half-life can be expected in case of orally administered nanomedicines, leading to reduction of administration frequency, dose and toxicity (Charlene et al. 2014; Dawidczyk et al. 2014). Regulation of pharmacokinetic characteristics of nanomedicines can results in significant advances in their utilization. Considerations of pharmacokinetic characteristics of nanomedicines and formulability for development purposes, direction and status of their development, and evaluation systems are thought to have important implications for effective development and use of more effective and safe nanomedicines. Therefore, we will present examples of effective go/stop evaluation stages through a review of pharmacokinetic characteristics and delivery of nanomedicines, and the status and processes of nanomedicine evaluation by global regulatory agencies through comparative analysis.

Delivery and pharmacokinetics of nanomedicines

Changes in pharmacokinetic characteristics of nanomedicines are due to changes in pharmacokinetic properties of their active pharmaceutical ingredients (API), which include longer stay in the body and greater distribution to target tissues, possibly increasing their efficacy and alleviating adverse reactions (Onoue et al. 2014). Regulation of efficacy and/or adverse reactions of nanomedicines is affected by alteration of pharmacokinetics such as in vivo absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion in the body.

Physiochemical properties of nanomedicines depend on their composition and formulation, which ultimately affect their efficacy and toxicity (EMA 2015a; TGA 2016). Control of physiochemical properties (e.g. composition or formulation) of nanomedicines and adjustment of the degree of binding between nanomedicines and biomolecules eventually regulate in vivo distribution of nanomedicines (EMA 2015a, b; TGA 2016). For example, it has been reported that the type and amount of binding proteins are significantly reduced when nanomedicines are prepared using PEGylated particles. Further, binding of polysorbate coated particles to ApoE was reported to increase their migration to the brain (EMA 2015a; TGA 2016).

Based on the above concepts connecting and efficacy/toxicity, Table 1 shows targeted delivery methods that can lead to changes in the pharmacokinetics of nanomedicines in the body. Delivery mechanisms of nanomedicines can be divided into intracellular transport, epileptic transport and other types (Table 1). Intercellular transport is regulated and facilitated by intracellularization, transporter-mediated endocytosis, and permeation enhancement through interactions involving particle size and/or cell surface (Francis et al. 2005; Jain and Jain 2008; Petros and DeSimone 2010; Roger et al. 2010). In general, a smaller particle size of nanomedicines increases intercellular transport, which facilitates cell permeation and affects absorption, distribution, and excretion of nanomedicines. In particular, cell internalization by transporter-mediated endocytosis depends on particle size of nanomedicines. When nanomedicine particles are large, opsonization occurs rapidly and their removal from the blood by endothelial macrophages is accelerated. It has been reported that affinity of cell surface transporters to nanomedicines varies depending on the particle size of nanomedicines, and this could also influence rapid removal of large particles from the blood by macrophages. In addition, nanomedicines containing non-charged polymers, surfactants, or polymer coatings which degrade in in vivo due to their hydrophilicity, interact with cell surface receptors or ligands to increase permeability or promote internalization of nanomedicines (Francis et al. 2005; Jain and Jain 2008; Petros and DeSimone 2010; Roger et al. 2010).

Table 1.

Target delivery characteristics related to pharmacokinetic properties of nanomedicines

| Targeting methods | Mechanism | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Intercellular transport | ||

| Cell internalization | Caveolar-mediated endocytosis (< 60 nm) Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (< 120 nm) |

Difference in intracellular defense mechanism depending on particle size Difference in affinity with cell surface transporter the easier the permeation to affect absorption, distribution and excretion by the smaller the particle size Removal from the blood by macrophages by large particles Increased permeability by changing the interaction with cell surface receptors or ligands by coating with polymers, surfactants |

| Transporter-mediated endocytosis | Interactions between molecules and nanoparticles by cell surface receptors in in vivo system | |

| Permeation accelerator | Perturbation of intracellular lipids by fatty acids | |

| Intracellular transport | ||

| Bioadhesive polymer | Opening reversible tight junction and increase of membrane permeability | Improvement of cytotoxic transport of intrinsic drugs by binding to specific proteins, antibodies and other in vivo polymers Anti-cancer drugs: Minimizing cytotoxicity in normal cells by reducing the anticancer effect of the site where the drug does not reach the tight junction and transferring it to the normal cells Reducing the elimination in lungs during inhalation |

| Chelator | Opening reversible tight junction and increase of membrane permeability | |

| Others | ||

| EPR effect | Accumulation in tumor cells | Increased anticancer efficacy through increased permeability to cancerous tissue and prolongation of retention time (ie, accumulation) |

| Conjugation with antibody, protein, peptide, polysaccharide | Selective delivery to target tissues | Control of delivery to the target using receptor/ligand or physiologic specific days on the surface of the target cell enhances drug efficacy/reduction of adverse reactions |

| Coated with unhygienic hydrophilic material | Improved stability and transport to mucus, prevention of opsonization | Reduction of macrophage-induced or mucosal instability such that drugs stay in the body for a long time to increase drug efficacy/reduce harmful reactions |

| Control of particle size to avoid removal by mucilage cilia | Retention extension in lung tissue | Degradation in lung mucosa or alleviation of macrophage action |

In addition, nanomedicines improve intracellular transport of active pharmaceutical ingredients through binding involving bioadhesive polymers or chelates (Table 1) (Bur et al. 2009; Des Rieux et al. 2006; Devalapally et al. 2007; Francis et al. 2005; Jain and Jain 2008; Mori et al. 2004; Roger et al. 2010). Increased intracellular trafficking of active pharmaceutical ingredients coupled to specific proteins, antibodies, and others in polymers in vivo occurs due to opening of tight junctions and/or increased membrane permeability. In particular, introduction of such a feature in anti-cancer agents can improve the effect of chemotherapy, including targeting brain tumors which are inaccessible to drugs bound by tight junctions, increasing tumor cell targeting, and reducing normal cell targeting. Cytotoxicity against normal cells can be minimized and anti-cancer efficacy achieved using such a nanomedicine strategy. Reduction of nanomedicine elimination in lungs during inhalation leads to increased due to reduced degradation and removal by lung mucosa or macrophages, resulting in increased drug retention time and movement of drug to the target.

Using the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, it is possible to increase anti-cancer efficacy through increasing tumor permeation and retention time. The EPR effect also makes it possible to selectively deliver nanomedicines to target tissue via conjugation to an antibody, protein, peptide, or polysaccharide, which can be used to modify delivery of nanomedicines to target tissues using receptor/ligand interactions or other physiologically specific target cell interactions, modulating drug efficacy or adverse reactions. Nanomedicines coated with hydrophilic material have improved stability, and their opsonization or accumulation in mucus is prevented. By inhibiting macrophage-induced or mucosal instability, nanomedicines can be retained in vivo, e.g., in lung tissue for prolonged periods of time through particle size, control and avoiding removal by mucus ciliates, which could lead to degradation or macroscopic effects in lung mucosa (Bur et al. 2009). Therefore, a variety of formulations have been developed to use delivery mechanisms which can control pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nanomedicines.

Classification and pharmacokinetic properties of nanomedicines

Nanomedicines exhibit a range of in vivo kinetic characteristics depending on their formulations. In this context, disadvantages and advantages of each type of formulation commonly used in nanomedicines (Devalapally et al. 2007) are summarized, and pharmacokinetic properties of various nanomedicines formulations are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Classification of nanomedicines considering pharmacokinetic properties

| Formulations | Pharmacokinetic properties | Others | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |||

| Dendrimers | Polysine Poly(amidoamine) PEGylated polylysine Lactoferrin-conjugated |

High permeability Release control Drug-selective delivery Improved solubility |

Limit of administration routes | Low immunogenicity Blood toxicity |

| Engineered nanoparticles | Nanocrystal SoluMatrix fine particle Nanosized amorphous |

Improved systemic exposure Increased retention time in mucus Various routes of administration |

Insufficient persistent emission | Gastric mucosal irritation relief of NSAIDs Toxicity by higher Cmax |

| Lipid nanosystems | Emulsion Liposome Solid lipid nanoparticle Lectin-modified solid lipid |

Degradation or metabolism of formulated materials Improved systemic exposure Drug-selective delivery Accumulation in tumor cells |

Quick removal by RES uptake Limit of administration routes |

Low toxicity and antigenicity Cytotoxicity due to surfactant |

| Micelles | High permeability Improved solubility Improved systemic exposure |

Insufficient persistent emission | Low immunogenicity Cytotoxicity due to surfactant |

|

| Polymeric nanoparticles | Ethyl cellulose/casein PLGA alginate, PLGA PLA-PEG Hydrogel Albumin Chitosan analog |

Stable drug release in in vivo Increased retention time of drug |

Required initial burst protection Limit of administration routes |

Low immunogenicity Required removal of non-degradable polymer |

Table 3.

Specific pharmacokinetic characteristics of drugs based on the classification of nanomedicines

| Formulations | API | Techniques | Administration routes | PK properties | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dendrimer | Doxorubicin | Polylysine dendrimer | IV | Increase of systemic exposure, accumulation in tumor cells | |

| Flurbiprofen | Poly(amidoamine) dendrimer | IV | Increase of distribution and retentions in inflammatory sites | ||

| Methotrexate | PEGylated polylysine dendrimer | IV | Prolongation of systemic exposure | ||

| Lactoferrin-conjugated dendrimer | IV | Accumulation in lungs | |||

| Piroxicam | Poly(amidoamine) dendrimer | IV | Prolongation of systemic exposure | ||

| Engineered NPs | Carbendazim | Nanocrystals | PO | Increase of oral F | |

| Cilostazol | Nanocrystals | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Curcumin | Nanocrystals | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Danazol | Nanocrystals | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Diclofenac | SoluMatrix™ fine particle | PO | Rapid absorption, pain relief | ||

| Fenofibrate | Nanocrystals | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Indomethacin | SoluMatrix fine particle | PO | Rapid absorption | ||

| Megestrol acetate | Nanocrystals | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Nitrendipine | Nanocrystals | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Nobiletin | Nanosized amorphous particles | PO | Increase of oral F, liver protective effect | ||

| Tranilast | Nanocrystals | PO | Increase of oral F, rapid absorption | ||

| Inhalable nanocrystalline powders | Lungs | Increase of anti-inflammatory effect in lungs | |||

| Paclitaxel | Albumin nanoparticles | IV | Tumor targeting | ||

| Lipid | Emulsion | Cinnarizine | Self-emulsifying drug delivery | PO | Increase of oral F |

| Coenzyme Q10 | Solid self-emulsifying delivery | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Cyclosporin A | Self-emulsifying drug delivery | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Inhalable dry emulsions | Lungs | Increase of anti-inflammatory effect in lungs | |||

| Halofantrine | Self-emulsifying drug delivery | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Simvastatin | Self-emulsifying drug delivery | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Liposomes | Amikacin | Liposome (Phospholipid/Chol) | IV | Increase of half-life | |

| Amphotericin B | Liposome (PC/Chol/DSPG) | IV | Increase of systemic exposure, decrease of RES uptake | ||

| Cytarabine/daunorubicin | Liposome (DSPC/DSPG/Chol) | IV | CL reduction | ||

| Doxorubicin | Liposome, PEGylated liposome | IV | Increase of distribution in tumor cells | ||

| O-palmitoyl tilisolol | Liposome (PC/Chol) | IV | Increase of distribution | ||

| Paclitaxel | Liposome (PC/PG) | IV | Prolongation of systemic exposure | ||

| Prednisolone | Liposome (PC/Chol/10% DSPE-PEG2000) | IV | Prolongation and increase of systemic exposure | ||

| Solid lipid NPs | Azidothymidine | Solid lipid NPs | IV | Increase of permeability and retention time in brain | |

| Clozapine | Solid lipid NPs | IV | Increase of systemic exposure, CL reduction | ||

| Diclofenac Na | Solid-in-oil NPs | Skin | Increase of percutaneous absorption | ||

| Insulin | Lectin-modified solid lipid NPs | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Lidocaine | Solid lipid nanoparticles | Skin | Regulation of skin permeability | ||

| Micelles | Camptothecin | Block copolymeric micelles | IV | Increase of systemic exposure | |

| Doxorubicin | Block copolymeric micelles | IV | Increase of systemic exposure, CL reduction | ||

| Paclitaxel | Block copolymeric micelles | IV | Increase of systemic exposure, CL reduction | ||

| Pilocarpine | Block copolymeric micelles | Eyes | Increase of efficacy | ||

| Tranilast | Self-micellizing solid dispersion | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Polymeric NPs | Celecoxib | Ethyl cellulose/casein NPs | PO | Increase of oral F | |

| Clotrimazole/econazole | PLGA and alginate NPs | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Docetaxel | PLA-PEG NPs | IV | Increase of half-life and anti-cancer effect | ||

| Doxorubicin | PLGA NPs | IV, IP | Increase of half-life, decrease of distribution in heart | ||

| Glucagon | PLGA NPs | Lungs | Increase of half-life, increase of oral F | ||

| Glucagon | PLGA NPs | Lungs | Increase of oral F and half-life | ||

| Insulin | Hydrogel NPs | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| Rifampicin | PLGA NPs | PO | Increase of oral F | ||

| siRNA | Chitosan analog NPs | PO | Increase of systemic exposure, gene silencing | ||

| VIP derivative | PLGA NPs | Lungs | Anti-inflammatory effect | ||

Dendrimers

Dendrimers are characterized by the presence of polysine, poly(amidoamine), PEGylated polylysine, or lactoferrin-conjugated formulations, with high membrane permeability, controlled release ability, selective delivery of active pharmaceutical ingredients, and solubility improvement. There have been reports of limitations in route of administration and immunogenicity, and blood toxicity cases have also been reported (Devalapally et al. 2007; Kawabata et al. 2011; Liu and Fréchet 1999; Mora-Huertas et al. 2010). Applications of dendrimer technology to active pharmaceutical ingredients are exemplified in several reports (Asthana et al. 2005; Barenholz 2012; Chaturvedi et al. 2013; Fanciullino et al. 2013; Feldman et al. 2012; Fetterly and Straubinger 2003; Hanafy et al. 2007; Hrkach et al. 2012; Jia et al. 2003; Jinno et al. 2006; Kaminskas et al. 2011, 2012; Kato et al. 2012; Kawabata et al. 2010; Kurmi et al. 2011; Larsen et al. 2013; Manvelian et al. 2012a, b; Manjunath and Venkateswarlu 2005; Matsumura et al. 2004; Morgen et al. 2012; Onoue et al. 2010a, b, 2011a, b, 2012a, b, 2013a, b; Pandey et al. 2005; Pathak and Nagarsenker 2009; Piao et al. 2008; Pepic´ et al. 2004; Prajapati et al. 2009; Reddy and Murthy 2004; Reddy et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2004; Strickley 2004; Sylvestre et al. 2011; Teshima et al. 2006; Thomas et al. 2012, 2013; Tomii 2002; Watanabe et al. 2006; Wu and Benet 2005; Xia et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2006, 2008, 2013). Polylysine dendrimer with doxorubicin, an intravenously administered anti-cancer nanomedicine, results in increased systemic exposure and tumor cell of doxorubicin. Poly(amidoamine) dendrimer with flurbiprofen is an intravenously injectable solution with increased distribution to the site of inflammation and increased in vivo retention time. PEGylated polylysine dendrimer with methotrexate or lactoferrin-conjugated dendrimer with methotrexate are intravenous formulations with prolonged systemic exposure and increased lung accumulation, respectively. Poly(amidoamine) dendrimer with piroxicam with is a formulation with increased systemic exposure.

Engineered nanoparticle

Engineered nanoparticles comprise nanocrystals, solumatrix fine particles, or nanosized amorphous particles, which can improve systemic exposure and decrease retention in the mucosal layer. They can be administered via various routes, but result in insufficient sustained release. Examples of engineered nanoparticle application include reducing gastric mucosal irritation due to NSAID nanomedicines, reducing other kinds of toxicity due to high Cmax compared to the original drug (Devalapally et al. 2007; Kawabata et al. 2011; Liu and Fréchet 1999; Mora-Huertas et al. 2010).

Carbendazim, cilostazol, curcumin, danazol, fenofibrate, megestrol acetate, nitrendipine, and tranilast are administered orally by increasing oral bioavailability (F) using nanocrystal formulations. Diclofenac and indomethacin formulations, using SoluMatrix™ fine particle technology, are oral formulations with improved absorption rates and pain relief. Nanosized amorphous particles of Nobilet show reduced hepatotoxicity (i.e., protection of liver function) with oral F. Inhalable nanocrystalline powder of Tranilast is a formulation administered directly to lungs and with improved anti-inflammatory effect. Albumin nanoparticles of paclitaxel improves targeting variability by increasing delivery to cancer cells when intravenously administered (Asthana et al. 2005; Barenholz 2012; Chaturvedi et al. 2013; Fanciullino et al. 2013; Feldman et al. 2012; Fetterly and Straubinger 2003; Hanafy et al. 2007; Hrkach et al. 2012; Jia et al. 2003; Jinno et al. 2006; Kaminskas et al. 2011, 2012; Kato et al. 2012; Kawabata et al. 2010; Kurmi et al. 2011; Larsen et al. 2013; Manvelian et al. 2012a, b; Manjunath and Venkateswarlu 2005; Matsumura et al. 2004; Morgen et al. 2012; Onoue et al. 2010a, b, 2011a, b, 2012a, b, 2013a, b; Pandey et al. 2005; Pathak and Nagarsenker 2009; Piao et al. 2008; Pepic´ et al. 2004; Prajapati et al. 2009; Reddy and Murthy 2004; Reddy et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2004; Strickley 2004; Sylvestre et al. 2011; Teshima et al. 2006; Thomas et al. 2012, 2013; Tomii 2002; Watanabe et al. 2006; Wu and Benet 2005; Xia et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2006, 2008, 2013).

Lipid nanosystems

Lipid nanosystems including emulsions, liposomes, solid-lipid nanoparticles, and lectin-modified solid lipids can be used to control the degradation and metabolism of the formulation and prolong systemic exposure. In addition, the selective delivery of pharmaceuticals can be improved and the pharmacological effect (e.g. anti-cancer effects in anti-cancer nanomedicines) can be enhanced by the increase of its accumulation in cancer tissues However, their disadvantages include rapid removal due to reticuloendothelial system (RES) uptake, limitation of administration routes, cytotoxicity risk due to low anti-genicity, and surfactant use for formulation (Devalapally et al. 2007; Kawabata et al. 2011; Liu and Fréchet 1999; Mora-Huertas et al. 2010).

Emulsions were formulated to increase oral F in both self-emulsifying and drug delivery systems, and several nanomedicines with emulsion formulations have been clinically used including cinnarizine, coenzyme Q10, cyclosporin A, halofantrine, and simvastatin. Inhalable dry emulsion of cyclosporin A is used to induce an anti-inflammatory effect in the lungs (Devalapally et al. 2007; Kawabata et al. 2011; Liu and Fréchet 1999; Mora-Huertas et al. 2010).

Differences in liposome constituents in liposome formulations have been documented in several reports (Asthana et al. 2005; Barenholz 2012; Chaturvedi et al. 2013; Fanciullino et al. 2013; Feldman et al. 2012; Fetterly and Straubinger 2003; Hanafy et al. 2007; Hrkach et al. 2012; Jia et al. 2003; Jinno et al. 2006; Kaminskas et al. 2011, 2012; Kato et al. 2012; Kawabata et al. 2010; Kurmi et al. 2011; Larsen et al. 2013; Manvelian et al. 2012a, b; Manjunath and Venkateswarlu 2005; Matsumura et al. 2004; Morgen et al. 2012; Onoue et al. 2010a, b, 2011a, b, 2012a, b, 2013a, b; Pandey et al. 2005; Pathak and Nagarsenker 2009; Piao et al. 2008; Pepic´ et al. 2004; Prajapati et al. 2009; Reddy and Murthy 2004; Reddy et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2004; Strickley 2004; Sylvestre et al. 2011; Teshima et al. 2006; Thomas et al. 2012, 2013; Tomii 2002; Watanabe et al. 2006; Wu and Benet 2005; Xia et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2006, 2008, 2013). Intravenous injectable solutions of amikacin and O-palmitoyl tilisolol in liposomes (Phospholipid/Chol) have been used for half-life extension, amphotericin B in liposomes (PC/Chol/DSPG) shows decreased systemic exposure and RES uptake, and cytarabine/daunorubicin in liposomes (DSPC/DSPG/Chol) has been used to reduce clearance. Pegylated liposome-treated doxorubicin results in increased distribution of doxotubicin to cancer tissues, and prednisolone in liposomes (PC/PG) or (PC/Chol/10% DSPE-PEG2000) results in prolonged systemic exposure. Solid-lipid nanoparticles of azidothymidine result in increased permeability to the brain, those of clozapine result in increased systemic exposure due to clearance reduction, those of diclofenac developed as a transdermal preparation result in increased transdermal absorption, and those of lidocaine as a transdermal preparation result in longer duration of drug efficacy by regulating skin permeability. A lectin-modified solid-lipid N of insulin shows increased oral F (Asthana et al. 2005; Barenholz 2012; Chaturvedi et al. 2013; Fanciullino et al. 2013; Feldman et al. 2012; Fetterly and Straubinger 2003; Hanafy et al. 2007; Hrkach et al. 2012; Jia et al. 2003; Jinno et al. 2006; Kaminskas et al. 2011, 2012; Kato et al. 2012; Kawabata et al. 2010; Kurmi et al. 2011; Larsen et al. 2013; Manvelian et al. 2012a, b; Manjunath and Venkateswarlu 2005; Matsumura et al. 2004; Morgen et al. 2012; Onoue et al. 2010a, b, 2011a, b, 2012a, b, 2013a, b; Pandey et al. 2005; Pathak and Nagarsenker 2009; Piao et al. 2008; Pepic´ et al. 2004; Prajapati et al. 2009; Reddy and Murthy 2004; Reddy et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2004; Strickley 2004; Sylvestre et al. 2011; Teshima et al. 2006; Thomas et al. 2012, 2013; Tomii 2002; Watanabe et al. 2006; Wu and Benet 2005; Xia et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2006, 2008, 2013).

Micelles

Micelles have advantages of high membrane permeability, and improved solubility and systemic exposure, but disadvantages of insufficient sustained release and cytotoxicity due to surfactant use (Devalapally et al. 2007; Kawabata et al. 2011; Liu and Fréchet 1999; Mora-Huertas et al. 2010). Block copolymeric micelles reduce clearance and increase systemic exposure of active pharmaceutical ingredients in intravenously administered formulations of camptothecin, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel. Block copolymer micelle allow direct administration to the eyeball increasing its efficacy. Self-micellizing solid dispersion of tranilast result in increased oral F (Asthana et al. 2005; Barenholz 2012; Chaturvedi et al. 2013; Fanciullino et al. 2013; Feldman et al. 2012; Fetterly and Straubinger 2003; Hanafy et al. 2007; Hrkach et al. 2012; Jia et al. 2003; Jinno et al. 2006; Kaminskas et al. 2011, 2012; Kato et al. 2012; Kawabata et al. 2010; Kurmi et al. 2011; Larsen et al. 2013; Manvelian et al. 2012a, b; Manjunath and Venkateswarlu 2005; Matsumura et al. 2004; Morgen et al. 2012; Onoue et al. 2010a, b, 2011a, b, 2012a, b, 2013a, b; Pandey et al. 2005; Pathak and Nagarsenker 2009; Piao et al. 2008; Pepic´ et al. 2004; Prajapati et al. 2009; Reddy and Murthy 2004; Reddy et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2004; Strickley 2004; Sylvestre et al. 2011; Teshima et al. 2006; Thomas et al. 2012, 2013; Tomii 2002; Watanabe et al. 2006; Wu and Benet 2005; Xia et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2006, 2008, 2013).

Polymeric nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles include ethyl cellulose/casein, PLGA (PLGA and alginate), PLA-PEG, hydrogel, albumin and chitosan analogs with characteristics of relatively stable drug release and prolonged duration of action. However, there are a few cases in which initial rupture is inhibited, or administration routes are limited. In particular, it is necessary to consider factors involved in elimination of non-degradable polymers from the body (Devalapally et al. 2007; Kawabata et al. 2011; Liu and Fréchet 1999; Mora-Huertas et al. 2010).

Polymeric nanoparticles with increased F include ethyl cellulose/casein nanoparticles with celecoxib, PLGA and alginate nanoparticle with clotrimazole/econazole or rifampicin, hydrogel nanoparticle with insulin, and an oral formulation of siRNA using chitosan analog nanoparticles. An docetaxel IV formulation using PLA-PEG nanoparticles showed a prolonged anticancer effect due to increased half-life. IV or IP formulations of LGA nanoparticles with doxorubicin have been reported to show reduced toxicity through prolongation of half-life and reduction of cardiac distribution. Half-life extension and F increase are also reported in the case of PLGA nanoparticles with glucagon (Asthana et al. 2005; Barenholz 2012; Chaturvedi et al. 2013; Fanciullino et al. 2013; Feldman et al. 2012; Fetterly and Straubinger 2003; Hanafy et al. 2007; Hrkach et al. 2012; Jia et al. 2003; Jinno et al. 2006; Kaminskas et al. 2011, 2012; Kato et al. 2012; Kawabata et al. 2010; Kurmi et al. 2011; Larsen et al. 2013; Manvelian et al. 2012a, b; Manjunath and Venkateswarlu 2005; Matsumura et al. 2004; Morgen et al. 2012; Onoue et al. 2010a, b, 2011a, b, 2012a, b, 2013a, b; Pandey et al. 2005; Pathak and Nagarsenker 2009; Piao et al. 2008; Pepic´ et al. 2004; Prajapati et al. 2009; Reddy and Murthy 2004; Reddy et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2004; Strickley 2004; Sylvestre et al. 2011; Teshima et al. 2006; Thomas et al. 2012, 2013; Tomii 2002; Watanabe et al. 2006; Wu and Benet 2005; Xia et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2006, 2008, 2013).

Pharmacokinetic properties of nanomedicines

Pharmacokinetic characteristics of various nanomedicines with different formulations are determined by particle size, shape (chemical structure), and surface chemical characteristics (FDA 2015). Nanomedicines with particle size less than 10 nm are removed by kidneys whereas those with particle size more than 10 nm are sometimes elongated and removed by the liver and/or the mononuclear-phagocyte system (MPS). The aim of regulating particle size in nanomedicines is to increase their retention in target tissues, and to remove them rapidly when distributed to non-target tissues. A protein corona is formed around nanomedicines by non-specific protein adsorption in body, but this is prevented by materials such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) applied on the nano-particle through surface coating. Such protein adsorption induces protein denaturation, which may lead to protein aggregation or phagocytosis due to activated macrophages. Nanoparticle targeting based on chemical properties of nanoparticles and surface coatings comprises active and passive targeting. Passive targeting is defined as non-specific accumulation in disease tissue (usually cancer tissue). This is especially applicable to solid cancers in which targeting results in increased blood vessel and transporter permeations and retention (enhanced permeability and retention, EPR effect) of nanomedicines, and their increased accumulation in tumor tissues. Specific or active targeting is defined as selective transport of nanomedicines containing protein, antibody, or small molecule only to specific tissues and/or specific cells. This may occur via homing to overexpressed cell-surface receptors.

Pharmacokinetic assessment of nanomedicine by regulatory agencies

As mentioned above, a wide variety of nanomedicine have been developed and approved for use in clinical practice and there are also a number of nanomedicines in clinical trials. As of 2016, 78 nanomedicines were on pharmaceutical markets across the world and 63 nanomedicines were approved as drugs or were in the approval process based on search results from ‘http://www.clinicaltrial.gov’. It would be meaningful to summarize key considerations of the approval authorities and use this knowledge for the development and approval of nanomedicines.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Nanoscale materials as defined by the US FDA include nanomaterials (materials used in the manufacture of nanomedicine, additives, etc.) and final products (nanomedicine). The particle size of such materials is typically 1–100 nm and such nanomedicines tend to result in increased bioavailability, decreased dose, improved drug efficacy, and decreased toxicity. Improvements in physical properties through effective formulation have led to improved solubility, dissolution rate, oral bioavailability, targeting to specific organs or cells, and/or improved dosage/convenience, leading to dose reduction with less adverse reactions due to the constituent active pharmaceutical ingredients or surfactants (FDA 2015).

Status of nanomedicines approved by the FDA

The FDA approved 51 nanomedicines by the year 2016, 40% of which were in clinical trials between 2014 and 2016 (Arnold et al. 2001; Benbrook 2015; Berges and Eligard 2005; Bobo et al. 2016; Desai et al. 2006; Duncan 2014; FDA 2006, 2014, 2015; Foss 2006; Foss et al. 2013; Fuentes et al. 2015; Green et al. 2006; Hann and Prentice 2001; Hu et al. 2012; Ing et al. 2016; James et al. 1994; Johnson et al. 1998; May and Li 2013; Möschwitzer and Müller 2006; Salah et al. 2010; Shegokar and Müller 2010; Taylor and Gercel-Taylor 2008; Ur Rehman et al. 2016; Wang-Gillam et al. 2016) (Table 4). Formulated nanomedicines approved by the FDA can be classified into polymer nanomedicines, micelles, liposomes, antibody-drug conjugates, protein nanoparticles, inorganic nanoparticles, hydrophilic polymers, and nanocrystals. Polymer nanomedicines are the simplest forms of nanomedicines and contain soft materials to increase solubility, biocompatibility, half-life and bioavailability as well as to control release of active pharmaceutical gradients from nanomedicines in body. In particular, Paxone®, Ulasta®, and PLEGRIDY® formulated with the use of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) are representative polymer nanomedicines resulting in increased half-life and bioavailability in in vivo. Micelles include Estrasorb®, BIND-014, and CALAA-01 as controlled-release forms of lipophilic drugs. Liposomes have reduced toxicity and increased bioavailability, and include Onivyde®, Doxil®, Visudyne®, and Thermodox®. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have been used to reduce drug cytotoxicity and improve solubility (PEGylation). ADCs are stable in blood and within targeted cancer cells and are expected to be released into intracellular or paracellular compartments after uptake. The pairing and linkage of antibody and drug are important, and are critical factors for their slow clearance and long half-life (approximately 3 and 4 days). Brentuximab emtasine is an example of an ADC nanomedicine which addresses safety issues by reducing toxicity of monomethyl auristane E. In this case, maleimide linkage and conjugation with thiolated antibody results in the release of only 2% monomethyl auristane E even 10 days after administration. ADCs with non-cleavable linkages such as those with tratuzumab are also available. Nanomedicines using protein nanoparticles include Abraxane®, an albumin-bound paclitaxel, and Ontak®, an engineered fusion protein, which consist of endogenous or engineered protein carriers. Inorganic nanoparticles in nanomedicine are drug formulations commonly used for treatment and/or imaging, in which metallic and metal oxide materials are used. Coating with hydrophilic polymers (dextran or sucrose) such as iron oxide is used for iron supplements including Venofer®, Ferrlecit®, INFed®, Dexferrum®, and Feraheme®, which show slow dissolution patterns after intravenous administration and less toxicity due to free iron in high dosage regimens. Because poor absorption of free iron is one of the reasons for increasing iron dosage resulting in severe toxicity, an iron oxide nanomedicine formulation with iron supplementation is clinically meaningful. Inorganic nanomedicines using gold are based on thermal and surface chemistry of gold, and it have not yet been approved by the FDA. Several clinical investigations using nanomedicines formulated with gold have been conducted. CYP-6091 containing colloidal gold with recombinant human tumor necrosis factor rhTNF is in a phase 2 trial, NBTXR3 and PEP503 are radio enhancers containing hifnium metal oxide for brain tumor treatment and inorganic silica nanoparticles for fluorescence-based cancer imaging, respectively, and are in phase 1 trials. Nanocrystal formulations increase nanoscale dimensions and improve dissolution and solubility and include Rapamune®, Tricor®, Emend®, and Megace ES®.

Table 4.

Nanomedicines approved by FDA

| Formulations | Product names | Pharmaceutical company | Indications | Characteristics | Approval year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer NP: synthetic polymer particles | |||||

| PEGylated adenosine deaminase enzyme | Adagen®/pegademase bovine | Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals |

Serious immunodeficiency therapy | Improved circulation (retention) in body and decreased immunogenicity | 1990 |

| PEGylated antibody fragment (Certolizumab) | Cimzia®/certolizumabpegol | UCB | Chron’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis | Improved circulation (retention) in body and stability | 2008 2009 2013 |

| Random copolymer of l-glutamate, l-alanine, l-lysine and l-tyrosine | Copaxone®/Glatopa | Teva | Multiple sclerosis | Regulation of CL by large amino-acid polymers | 1996 |

| Leuprolide acetate and polymer [PLGH(poly(dl-lactide-coglycolide)] | Eligard® | Tolmar | Prostate cancer | Regulation of drug delivery by prolongation of circulation (retention) in body | 2002 |

| PEGylated anti-VEGF aptamer (vascular endothelial growth factor) aptamer | Macugen®/Pegaptanib | Bausch&Lomb | Decreased vision | Improved aptamier stability by PEGylation | 2004 |

| Chemically synthesized ESA (erythropoiesis-stimulating agent) | Mircera®/Methoxy PEG glycol-epoetin β | Hoffman-LaRoche | Anemia with chronic renal failure | Improved aptamier stability by PEGylation | 2007 |

| PEGylated GCSF protein | Neulasta®/pegfilgrastim | Amgen | Leukopenia by chemotherapy | Improved protein stability by PEGylation | 2002 |

| PEGylated IFN alpha-2a protein | Pegasys® | Genentech | Hepatitis B and C | Improved protein stability by PEGylation | 2002 |

| PEGylated IFN alpha-2b protein | PegIntron® | Merck | Hepatitis C | Improved protein stability by PEGylation | 2001 |

| Poly(allylamine hydrochloride) | Renagel®

[sevelamer HCl]/Renagel® [sevelamer carbonate] |

Sanofi | Chronic renal failure | Regulation of drug delivery by prolongation of circulation (retention) in body and increased target delivery | 2000 |

| PEGylated HGH receptor antagonist | Somavert®/pegvisomant | Pfizer | Acromegaly | Improved protein stability by PEGylation | 2003 |

| Polymer-protein conjugate PEGylated l-asparaginase | Oncaspar®/pegaspargase | EnzonPharmaceuticals | Acute lymphocytic blood clot | Improved protein stability by PEGylation | 1994 |

| Polymer-protein conjugate (PEGylated porcine-likeuricase) | Krystexxa®/pegloticase | Horizon | Chronic gout | Improved protein stability by PEGylation | 2010 |

| Polymer-protein conjugate (PEGylated IFNbeta-1a) | Plegridy® | Biogen | Multiple sclerosis | Improved protein stability by PEGylation | 2014 |

| Polymer-protein conjugate (PEGylated factor VIII) | ADYNOVATE | Baxalta | Hemophilia | Improved protein stability by PEGylation | 2015 |

| Liposome | |||||

| Liposomal daunorubicin | DaunoXome® | Galen | Karposi sarcoma | Increased drug delivery to tumor cells and decreased systemic toxicity | 1996 |

| Liposomal cytarabine | DepoCyt© | Sigma-Tau | Lymphoma | Increased drug delivery to tumor cells and decreased systemic toxicity | 1996 |

| Liposomal vincristine | Marqibo® | Onco TCS | Acute lymphocytic blood clot | Increased drug delivery to tumor cells and decreased systemic toxicity | 2012 |

| Liposomal irinotecan | Onivyde® | Merrimack | Pancreatic cancer | Increased drug delivery to tumor cells and decreased systemic toxicity | 2015 |

| Liposomal amphotericin B | AmBisome® | Gilead Sciences | Fungal infection | Reduced renal toxicity | 1997 |

| Liposomal morphine sulphate | DepoDur® | Pacira Pharmaceuticals | Loss of pain due to surgery | Prolonged exposure | 2004 |

| Liposomal verteporfin | Visudyne® | Bauschand Lomb | Decreased vision, Ophthalmic hiscomaplastia | Improved drug delivery to lesion vessels and photosensitivity | 2000 |

| Liposomal doxorubicin | Doxil®/Caelyx™ | Janssen | Karposi sarcoma, ovarian cancer, Multiple myeloma | Increased drug delivery to target sites and decreased systemic toxicity | 1995 2005 2008 |

| Liposomal amphotericinB lipid complex | Abelcet® | Sigma-tau | Fungal infection | Reduced toxicity | 1995 |

| Liposome-proteins SP-band SP-C | Curosurf®/Poractantalpha | Chieseifarmaceutici | Lung activator for stress disorder | Increased drug delivery at low dose and decreased toxicity | 1999 |

| Micelles | |||||

| Micellar estradiol | Estrasorb™ | Novavax | Menopause hormone Therapy | Clinically release control | 2003 |

| Protein NP | |||||

| Albumin-bound paclitaxel NP | Abraxane®/ABI-007 | Celgene | Breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer | Improved solubility and drug delivery to target tissues | 2005 2012 2013 |

| Engineered protein combining L-2 and diphtheria toxin | Ontak® | Eisai Inc | T-Cell lymphoma | T cell-selective targeting | 1999 |

| Nanocrystal | |||||

| Aprepitant | Emend® | Merck | Vomiting agent | Rapid absorption and increased F | 2003 |

| Fenofibrate | Tricor® | Lupin Atlantis | Hyperlipidemia | Increased F | 2004 |

| Sirolimus | Rapamune® | Wyeth Pharmaceuticals |

Immunosupressant | Increased F and decreased dose | 2000 |

| Megestrol acetate | MegaceES® | Par Pharmaceuticals | Anorexia | Increased F and decreased dose | 2001 |

| Morphine sulfate | Avinza® | Pfizer | Mental stimulant | Increased F and decreased dose | 2002 2015 |

| Dexamethyl-phenidate HCl | Focalin XR® | Novartis | Mental stimulant | Increased F and decreased dose | 2005 |

| Metyhlphenidate HCl | Ritalin LA® | Novartis | Mental stimulant | Increased F and decreased dose | 2002 |

| Tizanidine HCl | Zanaflex® | Acorda | Muscle relaxant | Increased F and decreased dose | 2002 |

| Calcium phosphate | Vitoss® | Stryker | Bone substitute | Imitation of bone structure by cell adhesion and growth | 2003 |

| Hydroxyapatite | Ostim® | Heraseus Kulzer | Bone substitute | Imitation of bone structure by cell adhesion and growth | 2004 |

| Hydroxyapatite | OsSatura® | IsoTis Orthobiologics | Bone substitute | Imitation of bone structure by cell adhesion and growth | 2003 |

| Hydroxyapatite | NanOss® | Rti Surgical | Bone substitute | Imitation of bone structure by cell adhesion and growth | 2005 |

| Hydroxyapatite | EquivaBone® | Zimmer Biomet | Bone substitute | Imitation of bone structure by cell adhesion and growth | 2009 |

| Paliperidone Palmitate | Invega®Sustenna® | Janssen Pharms | Schizoaffective disorder | Control of slow release rate in drugs with low solubility | 2009 2014 |

| Dantrolene sodium | Ryanodex® | Eagle Pharmaceuticals | Malignant benign hypothermia | Rapid absorption at high dose | 2014 |

| Inorganic/metallic NPs | |||||

| Iron oxide | Nanotherm® | MagForce | Hybrid species | Vertical irritant effect by increased uptake | 2010 |

| Ferumoxytol SPION with poly glucose sorbitol carboxy methylether | Feraheme™/ferumoxytol | AMAG pharmaceuticals | Chronic renal failure with iron deficiency | Extended release and reduced dose | 2009 |

| Iron sucrose | Venofer® | Luitpold Pharmaceuticals |

Chronic renal failure with iron deficiency | Increased dose capacity | 2000 |

| Sodium ferric gluconate | Ferrlecit® | Sanofi Avertis | Chronic renal failure with iron deficiency | Increased dose capacity | 1999 |

| Iron dextran (low MW) | INFeD® | Sanofi Avertis | Chronic renal failure with iron deficiency | Increased dose capacity | 1995 |

| Iron dextran (high MW) | DexIron®/Dexferrum® | Sanofi Avertis | Chronic renal failure with iron deficiency | Increased dose capacity | 1997 |

| SPION coated with dextran | Feridex®/Endorem® | AMAG pharmaceuticals | Imaging materials | Vertical irritant effect | 1996 2008 |

| SPION coated with dextran | GastroMARK™/umirem® | AMAG pharmaceuticals | Imaging materials | Vertical irritant effect | 2001 2009 |

Suggested considerations for the evaluation of nanomedicines by the FDA

Based on guidelines and reports from the FDA, considerations for evaluation of nanomedicines are as follows. Evaluation of nano-formulation properties of nanomedicines comprises evaluating physicochemical properties of the nanomaterials, constituents and proportions of the nanomaterials, and quality and manufacturing of the nanomaterials (Eifler and Thaxton 2011; FDA 2010). First, pharmacokinetics of nanomedicines are assessed in the context of their systemic exposure considering (1) rate and amount of absorption and retention in circulation based on blood concentration over time, (2) relationship between prolongation of half-life and whole body exposure duration, and (3) bioavailability changes (Eifler and Thaxton 2011; FDA 2010, 2015). Second, assessment of nanomedicine distribution to blood and tissue is recommended to be done based on apparent volume of distribution, and distribution or accumulation to positive targeting sites based on time-dependent changes. Third, in the context of metabolism, it is important to evaluate whether decomposition or metabolism of nano-formulations or their active pharmaceutical ingredients occur. Fourth, elimination of raw materials used in nano-formulations, and products from decomposition and/or metabolism of nano-formulations and their active pharmaceutical ingredients are recommended for evaluation. The accumulation of nano-formulations in target tissues and elimination through MPS are also investigated. Finally, toxicity assessment of nanomedicines needs to be conducted.

EMA

In 2011, the EMA defined nanomedicines as drugs composed of nanomaterials 1–100 nm in size, and these are classified into liposomes, nanoparticles, magnetic NPs, gold NPs, quantum dots, dendrimers, polymeric micelles, viral and non-viral vectors, carbon nanotubes, and fullerenes (EFSA 2011; EMA 2015a).

Status of nanomedicines approved by the EMA

The EMA has approved 8 of the 11 commercially available nanomedicine drugs developed as first-generation nanomedicines (such as liposomes or iron-containing formulations), and three of them were withdrawn. Investigations were conducted to establish the scientific basis for efficacy and safety of 12 nanomedicines, and were evaluated via the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval process. Following this initial process, 48 nano medicines or imaging materials are currently in clinical trials (Phase 1–Phase 3) in the EU. In addition, preclinical trials are underway for a number of nanomedicine products (Draca et al. 2013; Ehmann et al. 2013; Hafner et al. 2014; Lawrence and Rees 2000; Ling et al. 2013; Shegokar and Müller 2010) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Nanomedicines approved by EMA

| Formulations | API | Product name | Pharmaceutical company | Administration route | Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocrystals | Aprepitan | Emend® | Merck Sharp and Dohme BV | Capsule | Vomiting after surgery |

| Fenofibrate | Tricor®/Lipanthyl®/Lipidil® | Recipharm, FR | Tablet | Hyperlipidemia | |

| Olanzapine | Zypadhera® | Lilly Pharma | Powder/solvent | Schizophrenia | |

| Paliperidone | Xeplion® | Janssen Pharmaceutica NV | Prolonged release suspension for injection (im) | Schizophrenia | |

| Sirolimus | Rapamune® | Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals, IE | Tablet | Kidney transplantation rejection | |

| Nanoemulsions | Cyclosporine | Norvir® | Aesica Queenborough Ltd | Soft capsules | HIV infection, kidney transplantation rejection |

| Pegaspargase (mPEG-asparaginase) | Oncaspar® | Sigma-tau Arzneimittel GmbH | Solution (iv/im) | Acute lymphocytic leukemia | |

| Sevelamer | Renagel®/Renvela® | Genzyme Ltd | Tablet | Dialysis, hyperphosphatemia | |

| Polymer-protein conjugates | Amphotericin B | AmBisome® | Gilead Sciences | Suspension (iv) | Fungal infection |

| Certolizumabpegol (PEG-anti-TNFFab) | Cimzia™ | UCB Pharma SA | Solution (sc) | Rheumatoid arthritis | |

| Methoxypolyethylene glycol-epoetin beta | Mircera® | Roche Pharma | Solution (iv/sc) | Anemia, chronic renal failure | |

| Pegfilgrastim (PEG-rhGCSF) | Neulasta® | Amgen Technology | Solution (sc) | Leukopenia by chemotherapy | |

| Peginterferonalpha-2a (mPEG-interferon alpha-2a) | Pegasys® | Roche Pharma | Solution (sc) | HBV/HCV infection | |

| Peginterferonalpha-2b (mPEG-interferon alpha-2b) | PegIntron® | Schering-Plough | Solution for injection (sc) | HIV inflammation | |

| Pegvisomant (PEG-HGH antagonist) | Somavert® | Pfizer Manufacturing | Solution for injection (sc) | Peripheral hypertrophy | |

| Liposomes | Cytarabine | DepoCyt® | Almac Pharma | Suspension (intrathecal) | Brain cancer |

| Daunorubicin | DaunoXome® | Gilead Sciences Ltd | Suspension (iv) | Kaposi sarcoma by HIV | |

| Doxorubicin | Myocet® | GP-Pharm | Suspension (iv) | Breast cancer | |

| Doxorubicin | Caelyx® | Janssen Pharmaceutical | Suspension (iv) | Breast cancer, ovarian cancer, Kaposi sarcoma | |

| Mifamurtide | Mepact® | Takeda | Suspension (iv) | Myosarcoma | |

| Morphine | DepoDur® | Almac Pharma | Suspension(epidural) | Pain | |

| Paclitaxel | Abraxane® | Celgene | Powder for suspension | Breast cancer | |

| Propofol | Diprivan®/Propofol-Lipuro®/Propofol® | Astra Zeneca | Emulsion (iv) | Anesthesia | |

| Verteporfin | Visudyne® | Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nürnberg | Suspension (iv) | Decreased vision, myopia | |

| Nanoparticles | Inactivated hepatitis A virus | Epaxal® | Crucell | Suspension (iv) | Hepatitis A vaccines |

| 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | Zevalin® | Bayer Pharma | Solution (iv) | Lymphoma | |

| Virosomes | Adjuvanted influenza vaccine | Inflexal® V | Crucell | Suspension (iv) | Influenza vaccines |

| Glatiramer (Glu,Ala,Tyr,Lys copolymer) | Copaxone® | Teva Pharmaceuticals | Solution (sc) | Multiple sclerosis | |

| Polymeric drugs | Sodium ferric gluconate | Ferrlecit® | Aventis Pharma | Solution (iv) | Anemia with iron deficiency |

| Nanocomplex | Ferric carboxymaltose | Ferinject® | Vifor | Solution (iv) | Iron deficiency |

| Ferumoxytol | Rienso® | Takeda | Solution (iv) | Anemia with iron deficiency, chronic renal failure | |

| Iron sucrose [iron(III)-hydroxidesucrose complex] | Visudyne® | Novartis | Solution (iv) | Iron deficiency | |

| Iron(III) isomaltoside | Monofer® | Pharmacosmos | Solution (iv) | Iron deficiency | |

| Iron(III)-hydroxide dextran complex | Ferrisat®/Cosmofer® | Pharmacosmos | Solution (iv) | Iron deficiency |

Suggesting points for the evaluation of nanomedicines in EMA

EMA presents that pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of nanomedicines were determined by chemical composition and physicochemical properties. So, EMA suggest to consider six possibilities to evaluate nanomedicines considering the chemical composition and physicochemical properties (EFSA 2011; TGA 2016) including (1) nano-formulations are unstable at the time of manufacture and are converted into non-nanosized form, (2) the state of conversion into non-nanosized form when the drug substance in the manufacturing site is present as a matrix, (3) conversion to non-nanosized forms due to lack of bio-similarity under in vitro non-stable conditions, (4) conversion from nano-forms to non-nanosized forms during toxicity assessment (5) co-existence of nano forms and non-nano forms at the in vivo administration site, and (6) existence of the nano form in biological samples and tissues after absorption. In view of these various considerations for nanomedicine evaluation, EMA suggested the need to discuss the following aspects for the evaluation of nanomedicines (EFSA 2011; EMA 2015a, b; Ehmann et al. 2013; TGA 2016). Overall, physicochemical properties, stability, and functionality of nanomedicines should be evaluated. To this end, interactions and reactivity with biointerfaces due to coatings or additives in the final nanomedicines, suitability of biomarkers of in vivo functionality of nanomedicines, in vivo distribution and bio-persistence of nanomedicines, long-term safety of decomposition products, and adequacy of dose and dose interval settings have emerged as key factors for the evaluation process. Notably, liposome formulations, iron-based formulations, and nanocrystal formulations which can be considered first-generation nanomedicines and have already been marketed and used, have proved their effectiveness and safety over a long period. Based on this status, evaluation methods for approval of second-generation nanomedicines have been suggested for consideration (Ehmann et al. 2013; EMA 2013a, b, EMA 2015b).

Future perspectives on nanomedicines considering their pharmacokinetic properties

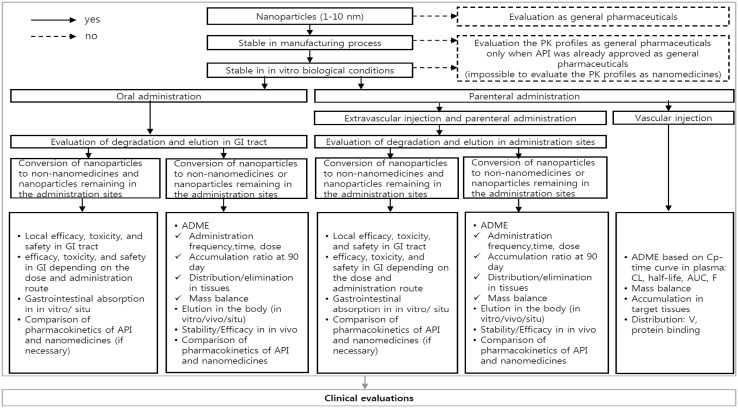

Given the considerations for development and use of nanomedicines, indispensable steps to attain clinical significance include assessment of the nature of formulations, pharmacokinetic properties, and the approval process for nanomedicines. Therefore, based on recent trends in nanomedicine development and guidelines of the FDA and EMA, we propose a simple algorithm to guide the recommended ADME evaluations of nanomedicines (Fig. 1). In the proposed algorithm, stability in the manufacturing process and simulated human conditions determine whether ADME properties of the drugs of interest are assessed or not. Assessment varies based on administration routes and distribution. For example, evaluation varies based on whether orally administered nanomedicines are found in nano forms or non-nano forms in the gastro-intestinal tract. Thus, the proposed algorithm provides critical and practical checkpoints in nanomedicine development and assessment.

Fig. 1.

A proposed new algorithm to assess ADME of nanomedicines

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Grant (16173MFDS542) from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2016.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

These authors (Young Hee Choi and Hyo-Kyung Han) declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Change history

11/5/2018

The article ?Nanomedicines: current status and future perspectives in aspect of drug delivery and pharmacokinetics?, written by Young Hee Choi and Hyo?Kyung Han, was originally published electronically on the publisher?s internet portal (currently SpringerLink) on 28 November 2017 without open access.

References

- Arnold J, Kilmartin D, Olson J, Neville S, Robinson K, Laird A. Verteporfin therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: two-year results of a randomized clinical trial including lesions with occult with no classic choroidal neovascularization-verteporfin in photodynamic therapy report 2. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:541–560. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)00967-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asthana A, Chauhan AS, Diwan PV, Jain NK. Poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendritic nanostructures for controlled site-specific delivery of acidic anti-inflammatory active ingredient. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2005;6:E536–E542. doi: 10.1208/pt060367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barenholz Y. Doxil®—the first FDA-approved nano-drug: lessons learned. J Control Release. 2012;160:117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbrook DM. Biotechnology and biopharmaceuticals: transforming proteins and genes into drugs, 2ndedition. Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2015;60:331–332. [Google Scholar]

- Berges R, Eligard R. Pharmacokinetics, effect on testosterone and PSA levels and tolerability. Eur Urol Suppl. 2005;4:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bobo D, Robinson KJ, Islam J, Thurecht KJ, Corrie SR. Nanoparticle-based medicines: a review of FDA-approved materials and clinical trials to date. Pharm Res. 2016;33:2373–2387. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-1958-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bur M, Henning A, Hein S, Schneider M, Lehr CM. Inhalative nanomedicine—opportunities and challenges. Inhal Toxicol. 2009;1:S137-S143. doi: 10.1080/08958370902962283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlene MD, Luisa MR, Peter CS. Nanomedicines for cancer therapy: state-of-the-art and limitations to pre-clinical studies that hinder future developments. Front Chem. 2014;2:69. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi K, Ganguly K, Nadagouda MN, Aminabhavi TM. Polymeric hydrogels for oral insulin delivery. J Control Release. 2013;165:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawidczyk CM, Kim C, Park JH, Russell LM, Lee KH, Pomper MG, Searson PC. State-of-the-art in design rules for drug delivery platforms: lessons learned from FDA-approved nanomedicines. J Control Release. 2014;10:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong WH, Borm PJ. Drug delivery and nanoparticles: applications and hazards. Int J Nanomed. 2008;3:133–149. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Rieux A, Fievez V, Garinot M, Schneider YJ, Préat V. Nanoparticles as potential oral delivery systems of proteins and vaccines: a mechanistic approach. J Control Release. 2006;116:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai N, Trieu V, Yao ZW, Louie L, Ci S, Yang A. Increased antitumor activity, intratumor paclitaxel concentrations, and endothelial cell transport of Cremophor-free, albumin-bound paclitaxel, ABI-007, compared with Cremophor-based paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1317–1324. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devalapally H, Chakilam A, Amiji MM. Role of nanotechnology in pharmaceutical product development. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:2547–2565. doi: 10.1002/jps.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draca N, Lazic R, Simic P, Dumic-Cule I, Luetic AT, Gabric N. Potential beneficial role of sevelamer hydrochloride in diabetic retinopathy. Med Hypotheses. 2013;80:431–435. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R. Polymer therapeutics: top 10 selling pharmaceuticals—what next? J Control Release. 2014;190:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehmann F, Sakai-Kato K, Duncan R, Hernán P, de la Ossa D, Pita R, Vidal JM, Kohli A, Tothfalusi L, Sanh A, Tinton S, et al. Next-generation nanomedicines and nanosimilars: EU regulators’ initiatives relating to the development and evaluation of nanomedicines. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:849–856. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eifler AC, Thaxton CS. Nanoparticle therapeutics: FDA approval, clinical trials, regulatory pathways, and case study. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;726:325–338. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-052-2_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority Guidance on the risk assessment of the application of nanoscience and nanotechnologies in the food and feed chain. EFSA J. 2011;9:2140. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (2013a) Reflection paper on surface coatings: general issues for consideration regarding parenteral administration of coated nanomedicine products. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/08/WC500147874.pdf

- European Medicines Agency (2013b) Reflection paper on the development of 5 block copolymer micelle medicinal products. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/02/WC500138390.pdf

- European Medicines Agency (2015a) Nanomedicines: EMA experience and perspective. http://www.euronanoforum2015.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2_NanomedicinesEMA-experienceperspective_DoloresHernan_10042015.pdf

- European Medicines Agency (2015b) Reflection paper on the data requirements for intravenous iron-based nano-colloidal products developed with reference to an innovator medicinal product. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2015/03/WC500184922.pdf

- Fanciullino R, Ciccolini J, Milano G. Challenges, expectations and limits for nanoparticles-based therapeutics in cancer: a focus on nano-albumin-bound drugs. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:504–513. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA (2006) FDA considerations for regulation of nanomaterial containing products [DOI] [PubMed]

- FDA (2010) A FDA perspective on nanomedicine current initiative in the US

- FDA (2014) Guidance for industry considering whether an FDA-regulated product involves the application of nanotechnology. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm257698.htm

- FDA (2015) Liposome drug products guidance for industry. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/default.htm

- Feldman EJ, Kolitz JE, Trang JM, Liboiron BD, Swenson CE, Chiarella MT, Mayer LD, Louie AC, Lancet JE. Pharmacokinetics of CPX-351; a nano-scale liposomal fixed molar ratio formulation of cytarabine: daunorubicin, in patients with advanced leukemia. Leuk Res. 2012;36:1283–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetterly GJ, Straubinger RM. Pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel-containing liposomes in rats. AAPS Pharm Sci. 2003;5:E32. doi: 10.1208/ps050432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss F. Clinical experience with Denileukin Diftitox (ONTAK) Semin Oncol. 2006;33(1 Supplement 3):S11–S16. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss FM, Sjak-Shie N, Goy A, Jacobsen E, Advani R, Smith MR. A multicenter phase II trial to determine the safety and efficacy of combination therapy with denileukin diftitox and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone in untreated peripheral T-cell lymphoma: the CONCEPT study. Leuk lymphoma. 2013;54:1373–1379. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.742521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis MF, Cristea M, Winnik FM. Exploiting the vitamin B12 pathway to enhance oral drug delivery via polymeric micelles. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2462–2467. doi: 10.1021/bm0503165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes AC, Szwed E, Spears CD, Thaper S, Dang LH, Dang NH (2015) Denileukin diftitox (Ontak) as maintenance therapy for peripheral T-Cell lymphomas: three cases with sustained remission. Case Rep Oncol Med 2015:123756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Green MR, Manikhas GM, Orlov S, Afanasyev B, Makhson AM, Bhar P, Hawkins MJ. Abraxane((R)), a novel Cremophor((R))-free, albuminbound particle form of paclitaxel for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1263–1268. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner A, Lovrić J, Lakoš GP, Pepić I. Nanotherapeutics in the EU: an overview on current state and future directions. Int J Nanomed. 2014;19:1005–1023. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S55359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanafy A, Spahn-Langguth H, Vergnault G, Grenier P, Tubic Grozdanis M, Lenhardt T, Langguth P. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of oral fenofibrate nanosuspensions and SLN in comparison to conventional suspensions of micronized drug. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann IM, Prentice HG. Lipid-based amphotericin B: a review of the last 10 years of use. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrkach J, Von Hoff D, Mukkaram Ali M, Andrianova E, Auer J, Campbell T, De Witt D, Figa M, Figueiredo M, Horhota A, et al. Preclinical development and clinical translation of a PSMA-targeted docetaxel nanoparticle with a differentiated pharmacological profile. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:128–139. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Miller L, Richman S, Hitchman S, Glick G, Liu S, Zhu Y, Crossman M, Nestorov I, Gronke RS, et al. A novel PEGylated interferon Beta-1a for multiple sclerosis: safety, pharmacology, and biology. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:798–808. doi: 10.1177/0091270011407068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ing M, Gupta N, Teyssandier M, Maillere B, Pallardy M, Delignat S, Lacroix-Desmazes S. Immunogenicity of long-lasting recombinant factor VIII products. Cell Immunol. 2016;301:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A, Jain SK. In vitro and cell uptake studies for targeting of ligand anchored nanoparticles for colon tumors. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2008;35:404–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James ND, Coker RJ, Tomlinson D, Harris JR, Gompels M, Pinching AJ. Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): an effective new treatment for Kaposi’s sarcoma in AIDS. Clin Oncol. 1994;6:294–296. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)80269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Wong H, Wang Y, Garza M, Weitman SD. Carbendazim: disposition, cellular permeability, metabolite identification, and pharmacokinetic comparison with its nanoparticle. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:161–172. doi: 10.1002/jps.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinno J, Kamada N, Miyake M, Yamada K, Mukai T, Odomi M, Toguchi H, Liversidge GG, Higaki K, Kimura T. Effect of particle size reduction on dissolution and oral absorption of a poorly water-soluble drug, cilostazol, in beagle dogs. J Control Release. 2006;111:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, Ford CC, Goldstein J, Lisak RP, Myers LW, Panitch HS, Rose JW, Schiffer RB, et al. Extended use of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) is well tolerated and maintains its clinical effect on multiple sclerosis relapse rate and degree of disability. Neurology. 1998;50:701–708. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.3.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminskas LM, Kelly BD, McLeod VM, Sberna G, Boyd BJ, Owen DJ, Porter CJ. Capping methotrexate α-carboxyl groups enhances systemic exposure and retains the cytotoxicity of drug conjugated PEGylated polylysine dendrimers. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:338–349. doi: 10.1021/mp1001872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminskas LM, McLeod VM, Kelly BD, Sberna G, Boyd BJ, Williamson M, Owen DJ, Porter CJ. A comparison of changes to doxorubicin pharmacokinetics, antitumor activity, and toxicity mediated by PEGylated dendrimer and PEGylated liposome drug delivery systems. Nanomedicine. 2012;8:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Chin K, Yoshikawa T, Yamaguchi K, Tsuji Y, Esaki T, Sakai K, Kimura M, Hamaguchi T, Shimada Y, et al. Phase II study of NK105, a paclitaxel-incorporating micellar nanoparticle, for previously treated advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:1621–1627. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9709-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, Yamamoto K, Debari K, Onoue S, Yamada S. Novel crystalline solid dispersion of tranilast with high photostability and improved oral bioavailability. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;39:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, Wada K, Nakatani M, Yamada S, Onoue S. Formulation design for poorly water-soluble drugs based on biopharmaceutics classification system: basic approaches and practical applications. Int J Pharm. 2011;420:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurmi BD, Gajbhiye V, Kayat J, Jain NK. Lactoferrin-conjugated dendritic nanoconstructs for lung targeting of methotrexate. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:2311–2320. doi: 10.1002/jps.22469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen AT, Ohlsson AG, Polentarutti B, Barker RA, Phillips AR, Abu-Rmaileh R, Dickinson PA, Abrahamsson B, Ostergaard J, Müllertz A. Oral bioavailability of cinnarizine in dogs: relation to SNEDDS droplet size, drug solubility and in vitro precipitation. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;48:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MJ, Rees GD. Microemulsion-based media as novel drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2000;45:89–121. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H, Luoma JT, Hilleman D. A review of currently available fenofibrate and fenofibric acid formulations. Cardiol Res. 2013;4:47–55. doi: 10.4021/cr270w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Fréchet JM. Designing dendrimers for drug delivery. Pharm Sci Technol Today. 1999;2:393–401. doi: 10.1016/s1461-5347(99)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Yang XL, Ho WS. Preparation of uniform-sized multiple emulsions and micro/nano particulates for drug delivery by membrane emulsification. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:75–93. doi: 10.1002/jps.22272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjunath K, Venkateswarlu V. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and bioavailability of clozapine solid lipid nanoparticles after intravenous and intraduodenal administration. J Control Release. 2005;107:215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvelian G, Daniels S, Gibofsky A. The pharmacokinetic parameters of a single dose of a novel nano-formulated, lower-dose oral diclofenac. Postgrad Med. 2012;124:117–123. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2012.01.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvelian G, Daniels S, Altman R. A phase I study evaluating the pharmacokinetic profile of a novel, proprietary, nano-formulated, lower-dose oral indomethacin. Postgrad Med. 2012;124:197–205. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2012.07.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y, Hamaguchi T, Ura T, Muro K, Yamada Y, Shimada Y, Shirao K, Okusaka T, Ueno H, Ikeda M, Watanabe N. Phase I clinical trial and pharmacokinetic evaluation of NK911, a micelle-encapsulated doxorubicin. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1775–1781. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May JP, Li S-D. Hyperthermia-induced drug targeting. Exp Opin Drug Deliv. 2013;10:511–527. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.758631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Huertas CE, Fessi H, Elaissari A. Polymer-based nanocapsules for drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2010;385:113–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgen M, Bloom C, Beyerinck R, Bello A, Song W, Wilkinson K, Steenwyk R, Shamblin S. Polymeric nanoparticles for increased oral bioavailability and rapid absorption using celecoxib as a model of a low-solubility, high-permeability drug. Pharm Res. 2012;29:427–440. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0558-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Matsuura A, Rama Prasad YV, Takada K. Studies on the intestinal absorption of low molecular weight heparin using saturated fatty acids and their derivatives as an absorption enhancer in rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:418–421. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möschwitzer J, Müller RH. New method for the effective production of ultrafine drug nanocrystals. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2006;6:3145–3153. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue S, Takahashi H, Kawabata Y, Seto Y, Hatanaka J, Timmermann B, Yamada S. Formulation design and photochemical studies on nanocrystal solid dispersion of curcumin with improved oral bioavailability. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99:1871–1881. doi: 10.1002/jps.21964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue S, Uchida A, Kuriyama K, Nakamura T, Seto Y, Kato M, Hatanaka J, Tanaka T, Miyoshi H, Yamada S. Novel solid self-emulsifying drug delivery system of coenzyme Q10 with improved photochemical and pharmacokinetic behaviors. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;46:492–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue S, Aoki Y, Kawabata Y, Matsui T, Yamamoto K, Sato H, Yamauchi Y, Yamada S. Development of inhalable nanocrystalline solid dispersion of tranilast for airway inflammatory diseases. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:622–633. doi: 10.1002/jps.22299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue S, Kuriyama K, Uchida A, Mizumoto T, Yamada S. Inhalable sustained-release formulation of glucagon: in vitro amyloidogenic and inhalation properties, and in vivo absorption and bioactivity. Pharm Res. 2011;28:1157–1166. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue S, Sato H, Ogawa K, Kojo Y, Aoki Y, Kawabata Y, Wada K, Mizumoto T, Yamada S. Inhalable dry-emulsion formulation of cyclosporine A with improved anti-inflammatory effects in experimental asthma/COPD-model rats. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;80:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue S, Matsui T, Kuriyama K, Ogawa K, Kojo Y, Mizumoto T, Karaki S, Kuwahara A, Yamada S. Inhalable sustained-release formulation of long-acting vasoactive intestinal peptide derivative alleviates acute airway inflammation. Peptides. 2012;35:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue S, Nakamura T, Uchida A, Ogawa K, Yuminoki K, Hashimoto N, Hiza A, Tsukaguchi Y, Asakawa T, Kan T, Yamada S. Physicochemical and biopharmaceutical characterization of amorphous solid dispersion of nobiletin, a citrus polymethoxylated flavone, with improved hepatoprotective effects. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;49:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue S, Kojo Y, Suzuki H, Yuminoki K, Kou K, Kawabata Y, Yamauchi Y, Hashimoto N, Yamada S. Development of novel solid dispersion of tranilast using amphiphilic block copolymer for improved oral bioavailability. Int J Pharm. 2013;452:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue S, Yamada S, Chan HK. Nanodrugs: pharmacokinetics and safety. Int J Nanomed. 2014;20:1025–1037. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S38378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R, Ahmad Z, Sharma S, Khuller GK. Nano-encapsulation of azole antifungals: potential applications to improve oral drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2005;301:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak P, Nagarsenker M. Formulation and evaluation of lidocaine lipid nanosystems for dermal delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2009;10:985–992. doi: 10.1208/s12249-009-9287-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepic´ I, Jalsenjak N, Jalsenjak I. Micellar solutions of triblock copolymer surfactants with pilocarpine. Int J Pharm. 2004;272:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros RA, DeSimone JM. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:615–627. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao H, Kamiya N, Hirata A, Fujii T, Goto M. A novel solid-in-oil nanosuspension for transdermal delivery of diclofenac sodium. Pharm Res. 2008;25:896–901. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati RN, Tekade RK, Gupta U, Gajbhiye V, Jain NK. Dendimer-mediated solubilization, formulation development and in vitro-in vivo assessment of piroxicam. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:940–950. doi: 10.1021/mp8002489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy LH, Murthy RS. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution studies of Doxorubicin loaded poly(butyl cyanoacrylate) nanoparticles synthesized by two different techniques. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2004;148:161–166. doi: 10.5507/bp.2004.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy LH, Sharma RK, Chuttani K, Mishra AK, Murthy RR. Etoposide-incorporated tripalmitin nanoparticles with different surface charge: formulation, characterization, radiolabeling, and biodistribution studies. AAPS J. 2004;6:e23. doi: 10.1208/aapsj060323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger E, Lagarce F, Garcion E, Benoit JP. Biopharmaceutical parameters to consider in order to alter the fate of nanocarriers after oral delivery. Nanomedicine. 2010;5:287–306. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salah EDTA, Bakr MM, Kamel HM, Abdel KM. Magnetite nanoparticles as a single dose treatment for iron deficiency anemia. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Sharma S, Khuller GK. Lectin-functionalized poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles as oral/aerosolized antitubercular drug carriers for treatment of tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:761–766. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shegokar R, Müller RH. Nanocrystals: industrially feasible multifunctional formulation technology for poorly soluble actives. Int J Pharm. 2010;399:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickley RG. Solubilizing excipients in oral and injectable formulations. Pharm Res. 2004;21:201–230. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000016235.32639.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre JP, Tang MC, Furtos A, Leclair G, Meunier M, Leroux JC. Nanonization of megestrol acetate by laser fragmentation in aqueous milieu. J Control Release. 2011;143:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. MicroRNA signatures of tumorderived exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshima M, Fumoto S, Nishida K, Nakamura J, Ohyama K, Nakamura T, Ichikawa N, Nakashima M, Sasaki H. Prolonged blood concentration of prednisolone after intravenous injection of liposomal palmitoyl prednisolone. J Control Release. 2006;112:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TGA (2016) Regulation of nanomedicines by the therapeutic goods administration