Abstract

Introduction

We assessed outcome and outcome-measure reporting in randomised controlled trials evaluating surgical interventions for anterior-compartment vaginal prolapse and explored the relationships between outcome reporting quality with journal impact factor, year of publication, and methodological quality.

Methods

We searched the bibliographical databases from inception to October 2017. Two researchers independently selected studies and assessed study characteristics, methodological quality (Jadad criteria; range 1–5), and outcome reporting quality Management of Otitis Media with Effusion in Cleft Palate (MOMENT) criteria; range 1–6], and extracted relevant data. We used a multivariate linear regression to assess associations between outcome reporting quality and other variables.

Results

Eighty publications reporting data from 10,924 participants were included. Seventeen different surgical interventions were evaluated. One hundred different outcomes and 112 outcome measures were reported. Outcomes were inconsistently reported across trials; for example, 43 trials reported anatomical treatment success rates (12 outcome measures), 25 trials reported quality of life (15 outcome measures) and eight trials reported postoperative pain (seven outcome measures). Multivariate linear regression demonstrated a relationship between outcome reporting quality with methodological quality (β = 0.412; P = 0.018). No relationship was demonstrated between outcome reporting quality with impact factor (β = 0.078; P = 0.306), year of publication (β = 0.149; P = 0.295), study size (β = 0.008; P = 0.961) and commercial funding (β = −0.013; P = 0.918).

Conclusions

Anterior-compartment vaginal prolapse trials report many different outcomes and outcome measures and often neglect to report important safety outcomes. Developing, disseminating and implementing a core outcome set will help address these issues.

Keywords: Anterior repair, Colporrhaphy, Core outcome sets, Cystocele, Outcomes, Outcome measures

Introduction

The most common type of pelvic organ prolapse (PO) is anterior-compartment prolapse. Hendrix et al. demonstrated in a group of 16,616 postmenopausal women a prevalence of anterior-compartment prolapse of 34%, and this was much higher than the rates of apical- or posterior-compartment prolapse [1]. The aetiology of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is complex and associated with various factors such as age, menopausal status and childbirth-related pelvic floor trauma [2, 3]. Possible surgical interventions include biological-graft, mesh and native tissue repair [4, 5]. The development of new surgical interventions is urgently required, and potential surgical interventions require robust evaluation. Selecting appropriate efficacy and safety outcomes is a crucial step in designing randomised trials. Outcomes collected and reported in randomised trials should be relevant to a broad range of stakeholders, including women with anterior-compartment prolapse, healthcare professionals and researchers. For example, resolution of bladder symptoms is an important outcome for all stakeholders; however, it is not commonly reported across trials. Even when outcomes have been consistently reported, secondary research methods, including pair-wise meta-analysis, may be limited by the use of different definitions and measurement instruments [6, 7]. A core outcome set should help address these issues. The first stage in core outcome-set development is to evaluate outcome and outcome-measure reporting across published trials. Therefore, we systematically evaluated outcome and outcome-measure reporting in published randomised trials evaluating surgical interventions for anterior-compartment prolapse. In addition, we assessed the relationships between outcome reporting quality with other important variables, including year of publication, impact factor and methodological quality.

Materials and methods

This systematic review is part of a wider project of the International Collaboration for Harmonising Outcomes, Research and Standards in Urogynaecology and Women’s Health (CHORUS) (i-chorus.org) and was registered with the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative database, registration number 981, and with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration identification CRD42017062456. We searched bibliographical databases comprising the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EMBASE and MEDLINE from inception to September 2017. The search strategy used several MeSH terms, including bladder prolapse, cystocele and POP. Randomised trials evaluating surgical interventions for anterior-compartment prolapse were eligible. We included trials evaluating the surgical management of anterior prolapse as a unicompartmental prolapse procedure, as well as trials in which anterior repair was undertaken in addition to other surgical interventions. Non-randomised studies, observational studies and case reports were excluded.

Two researchers (CD and AE) independently screened the titles and abstracts of electronically retrieved articles. The articles potentially eligible for inclusion were retrieved in full text to assess eligibility, and reference lists were independently reviewed. Any discrepancies between the researchers were resolved by review of a third senior researcher (SKD). Two researchers (CD and AE) independently extracted the study characteristics, including year of publication, journal topicality (subspecialist, general obstetrics and gynaecology or general medicine), journal’s impact factor and commercial funding (yes/no). The journal’s impact factor was determined using InCites Journal Citation Reports (Clarivate Analytics, Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA). Funding status was identified by reviewing the article text and included the donation of equipment or other resources. Two researchers (CD and AE) independently assessed the methodological quality of included randomised trials using the modified Jadad criteria (score range 1–5) [8]. Studies were assessed as high quality when they achieved a score >4. Outcome reporting quality was assessed using the Management of Otitis Media with Effusion in Cleft Palate (MOMENT) criteria (score range 1–5) [9]. Studies were assessed as high quality when they achieved a score >4.

The non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Spearman’s rho) was used to explore univariate associations between outcome reporting quality and impact factor during the year of publication, year of publication and methodological quality. Multivariate linear regression analysis using the Enter model was also undertaken to assess the combined association of quality of outcome reporting and journal type, impact factor during the year of publication, year of publication and methodological quality (independent variables) with outcome reporting (dependent variable). All tests were two-tailed. Statistical significance was set at 0.05, and analyses were conducted using the SPSS statistical software (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY, USA).

This study was reported with reference to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [6].

Results

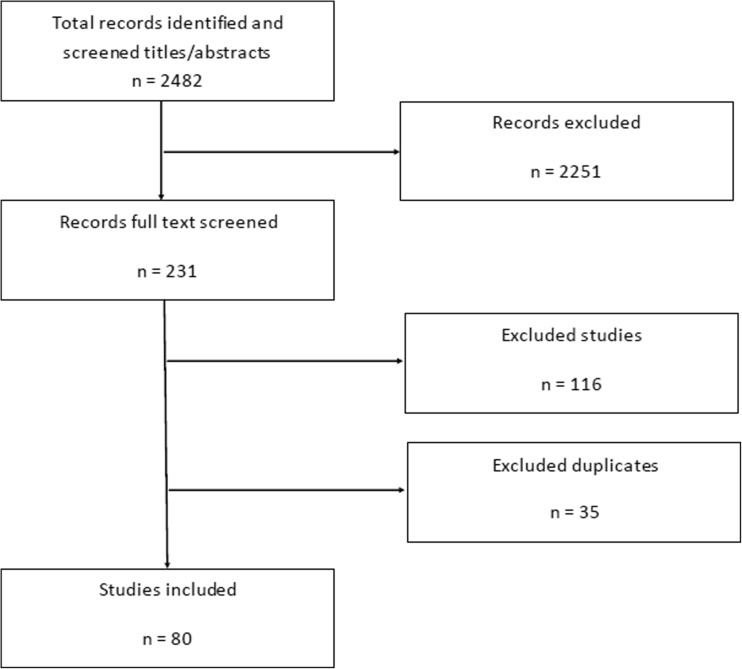

In total, 2482 titles and abstracts were screened, and 231 potentially relevant studies were examined in detail (Fig. 1). Sixty-eight randomised trials, reporting data from 10,499 participants, met the inclusion criteria (Table 1) [5, 10–88]. Additionally, 12 randomised trials published long-term follow-up data [5, 22, 29, 39, 40, 64, 71, 72, 79, 81, 86, 87].

Fig. 1.

Study search and inclusion

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Author | Study year | Journal | Impact factor | Journal type3 | Jadad score | MOMENT score | Study size | Commercial funding | Validated questionnaire use | Intervention group 1 | Intervention group 2 | Intervention group 3 | Intervention group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altman et al.a | 2011 | New England Journal of Medicine | 29.1 | G | 4 | 5 | 389 | Yes | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Antosh et al. | 2013 | Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.78 | S | 3 | 6 | 60 | No | Yes | Use of dilators post prolapse surgery | Non-use of dilators post prolapse surgery | ||

| Ballard et al. | 2014 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.17 | G | 5 | 5 | 150 | No | Yes | Preop. bowel preparation | Preop. non bowel preparation | ||

| Benson et al. | 1996 | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | – | S | 3 | 3 | 80 | No | No | Pelvic surgery for prolapse | Abdominal surgery | ||

| Borstad et al.a | 2009 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.84 | SS | 3 | 4 | 184 | No | No | Anterior colporrhaphy TVT | Anterior colporrhaphy + TVT staged procedure | ||

| Bray et al. | 2017 | European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology | N/A | G | 3 | 5 | 60 | No | N/A | Suprapubic catheter | Immediate removal of catheter | ||

| Carey et al. | 2009 | British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.64 | S | 3 | 5 | 139 | Yes | Yes | Conventional vaginal repair | Mesh vaginal repair | ||

| Choe et al.a | 2000 | Journal of Urology | 2.64 | SS | 2 | 3 | 40 | No | Yes | Antilogous vaginal wall slings | Micromesh | ||

| Colombo et al.a | 2000 | British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.64 | S | 3 | 3 | 71 | No | No | Anterior colporrhaphy | Burch colposuspension | ||

| da Silveira et al. | 2014 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.17 | SS | 3 | 5 | 184 | Yes | Yes | Native tissue repair | Synthetic mesh repair | ||

| Dahlgren et al. | 2011 | Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica | 2.2 | S | 3 | 3 | 135 | No | Yes | Conventional colporrhaphy | Porcine skin graft | ||

| Delroy et al.a,b | 2013 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.45 | SS | 5 | 6 | 79 | Yes | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Dias et al.a,c | 2016 | Neurourology and Urodynamics | 2.48 | SS | 5 | 6 | 88 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| de Tayrac et al.a | 2012 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.53 | SS | 3 | 5 | 147 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Ek et al.a | 2012 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.53 | SS | 2 | 4 | 99 | No | Yes | Anterior trocar-guided transvaginal mesh repair | Anterior colporrhaphy with lateral defects repair | ||

| Ek et al.a | 2010 | Neurourology and Urodynamics | 3.01 | SS | 5 | 4 | 50 | No | N/A | Anterior colporrhaphy | Trocar guided transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| El-Nazer et al.a | 2012 | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 1.56 | S | 5 | 5 | 44 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Farthmann et al.a | 2013 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.45 | SS | 3 | 3 | 200 | Yes | Yes | Conventional anterior colporrhaphy | Partially absorbable mesh | ||

| Feldner et al.a,b | 2010 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.66 | SS | 5 | 5 | 56 | Yes | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | SIS graft | ||

| Feldner et al.a,c | 2012 | Clinical Science | 5.87 | G | 5 | 4 | 56 | No | Yes | Small intestine submucosa graft | Traditional colporrhaphy | ||

| Galvind et al. | 2007 | Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica | 1.94 | G | 3 | 2 | 136 | No | N/A | 3-h catheterisation and vaginal tampon | 24-h catheterisation and vaginal tampon | ||

| Gandhi et al.a | 2005 | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4 | S | 3 | 5 | 154 | No | No | Anterior colporrhaphy | Colporrhaphy and fascial patch | ||

| Geller et al. | 2011 | British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.34 | S | 3 | 4 | 50 | No | N/A | Spontaneous postop. micturition | Micturition after bladder refill | ||

| Glazener et al.b | 2017 | The Lancet | N/A | G | 3 | 6 | 1352 | No | Yes | Standard repair | Mesh repair | Biological graft | |

| Glazener et al.c | 2017 | Health Technology Assessment | N/A | G | 4 | 6 | 3087 | No | Yes | Standard repair | Mesh repair | Biological graft | |

| Guerette et al.a | 2009 | Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.69 | S | 4 | 4 | 94 | Yes | Yes | Anterior repair | Anterior repair + porcine graft mesh | ||

| Gupta et al.a | 2014 | South African Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology | 0.23 | S | 3 | 4 | 106 | No | N/A | Anterior repair | Anterior repair + mesh | ||

| Hakvoort | 2004 | British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.75 | S | 2 | 3 | 100 | No | N/A | 4-day catheterisation | 1-day catheterisation | ||

| Henn et al. | 2016 | International Urogynecology Journal | 1.83 | SS | 5 | 6 | 80 | No | N/A | Vaginal vasoconstrictor infiltration | Vaginal saline infiltration | ||

| Hiltunen et al.a,b | 2007 | Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.45 | G | 3 | 4 | 202 | No | No | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Nieminen et al.a,c | 2010 | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.98 | G | 3 | 4 | 202 | No | No | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Nieminen et al.a,c | 2008 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.51 | SS | 3 | 2 | 202 | No | No | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Huang et al. | 2010 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.66 | SS | 3 | 3 | 90 | No | N/A | Removal of catheter on day 2 postop. | Removal of catheter on day 3 postop. | Removal of catheter on day 4 postop. | |

| Hviid et al.a | 2010 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.66 | SS | 3 | 3 | 61 | No | Yes | Conventional anterior repair | Anterior repair + porcine skin collagen implants | ||

| Iglesia et al. | 2010 | Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.98 | S | 5 | 6 | 65 | No | Yes | Conventional colporrhaphy or uterosacral ligament suspension | Vaginal colpopexy with mesh | ||

| Kamilya et al. | 2010 | Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research | 1.13 | S | 3 | 6 | 200 | No | N/A | Catheter removal day 4 postop. | Catheter removal day 1 postop. | ||

| Khalil et al. | 2016 | Journal of Clinical Anaesthesia | 1.64 | S | 5 | 5 | 57 | No | No | General anaesthesia | General anaesthesia + pudendal nerve block | ||

| Kringel et al.a | 2010 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.66 | SS | 3 | 5 | 232 | No | N/A | Intraurethral catheterisation 24 h | Intraurethral catheterisation 96 h | Suprapubic catheterisation 96 h | |

| Lambin et al.a | 2013 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.45 | SS | 3 | 5 | 68 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy with vaginal colposuspension | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Lazzeri et al.a | 2007 | Journal of Urology | 4.27 | S | 3 | 5 | 47 | No | Yes | Abdominal prolapse repair NO Burch colposuspension | Abdominal prolapse repair and Burch colposuspension | ||

| Lindholm et al. | 1985 | International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics | N/A | S | 4 | 3 | 20 | No | N/A | Phenoxybenzamine use | Control | ||

| Mahuvrata et al. | 2011 | Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 0.75 | G | 5 | 5 | 66 | No | Yes | Mesh repair | No mesh | PDS | Vicryl |

| McNanley et al. | 2012 | Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery | 0.42 | SS | 3 | 6 | 60 | No | Yes | Docusate sodium laxative postoperative | Other laxatives postoperative | ||

| Menefee et al.a | 2011 | Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 5.34 | S | 5 | 6 | 99 | Yes | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Mesh repair | Biological graft | |

| Meschia et al.a | 2003 | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 2.96 | S | 3 | 5 | 50 | No | No | Endopelvic fascia plication | TVT + Anterior repair | ||

| Minassian et al.a | 2014 | Neurourology and Urodynamics | 2.71 | SS | 3 | 5 | 70 | No | Yes | Conventional anterior colporrhaphy | Abdominal paravaginal defect repair | ||

| Miranda et al.a | 2011 | Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada | 1.42 | S | 5 | 2 | 22 | No | N/A | Anterior colporrhaphy with polyglactin 910 mesh | Anterior colporrhaphy without plication of pubovesical fascia | ||

| Natale et al.a | 2009 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.84 | SS | 3 | 5 | 190 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Synthetic mesh | ||

| Park et al.a | 2013 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.45 | SS | 3 | 5 | 92 | No | Yes | Anterior repair + TVT | TVT | ||

| Pauls et al. | 2015 | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 5.23 | S | 5 | 5 | 74 | No | Yes | Dexamethasone prior to surgery | Placebo | ||

| Ploege et al. | 2015 | International Urogynecology Journal | 1.83 | SS | 3 | 6 | 91 | Yes | Yes | Prolapse surgery | Prolapse surgery + TVT | ||

| Qatawneh et al. | 2013 | Gynaecological Surgery | 0.46 | S | 3 | 5 | 116 | No | No | Native tissue repair | Mesh repair | ||

| Quadri et al.a | 2000 | International Urogynecology Journal | 1.15 | SS | 3 | 3 | 45 | No | N/A | Use of PGE-2 | Control | ||

| Robert et al.a | 2014 | Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.76 | S | 5 | 4 | 57 | Yes | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Rudnicki et al.a,b | 2013 | British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 2.9 | G | 3 | 5 | 160 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Rudnicki et al.a,c | 2015 | British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 2.9 | G | 3 | 3 | 138 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Sand et al. | 2001 | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 2.72 | S | 3 | 4 | 161 | No | N/A | Conventional anterior colporrhaphy | Use of mesh | ||

| Schierlitz et al. | 2013 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.45 | SS | 3 | 5 | 80 | No | Yes | Conventional pelvic repair | Conventional pelvic repair + TVT | ||

| Segal et al. | 2006 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.38 | SS | 3 | 5 | 40 | No | No | Local anaesthesia | General anaesthesia | ||

| Sivaslioglu et al.a | 2007 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.79 | SS | 3 | 2 | 90 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Stekkinger et al. | 2011 | Gynecologic and Obstetric investigation | 1.74 | G | 3 | 5 | 126 | No | N/A | Trans urethral catheter | S/pubic catheter | ||

| Tamanini et al.a,b | 2012 | International Braz J Urol: official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology | 1.24 | G | 4 | 5 | 100 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Tamanini et al.a,c | 2012 | International Braz J Urol: official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology | 1.24 | G | 4 | 5 | 100 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Tamanini et al.a,c | 2014 | Journal of Urology | 4.68 | S | 4 | 5 | 92 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Tantanasis et al.a | 2008 | Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica | 1.72 | S | 2 | 2 | 50 | No | No | Anterior colporrhaphy | Bladder base tape repair | ||

| Thiagamoorthy et al. | 2013 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.45 | SS | 5 | 6 | 190 | No | N/A | Use of postop. vaginal pack | No use of postop. vaginal pack | ||

| Tincello et al.a | 2009 | British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.18 | S | 3 | 4 | 31 | No | Yes | Colposuspension + anterior repair | TVT + Anterior repair | ||

| Turgal et al.a | 2013 | European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology | 2.4 | G | 3 | 2 | 40 | No | No | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Van et al. | 2011 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.39 | SS | 3 | 5 | 179 | No | N/A | 1-day suprapubic catheterisation | 3-day suprapubic catheterisation | ||

| Vollebregt et al.a,b | 2011 | British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 2.96 | S | 5 | 6 | 125 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Vollebregt et al.a,c | 2012 | Journal of Sexual Medicine | 3.67 | SS | 5 | 6 | 125 | No | Yes | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal anterior or posterior mesh repair | ||

| Weber et al.a,b | 2001 | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 2.72 | G | 2 | 3 | 114 | No | No | Unilateral anterior colporrhaphy | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | |

| Chmielewski et al.a,c | 2011 | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 5.34 | G | 4 | 4 | 114 | No | No | Unilateral anterior colporrhaphy | Anterior colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | |

| Weemhoff et al.a | 2011 | International Urogynecology Journal | 2.39 | SS | 3 | 6 | 246 | No | N/A | Postop. catheterisation for 2 days | Postop. catheterisation for 5 days | ||

| Wei et al.a | 2012 | New England Journal of Medicine | 29.36 | G | 5 | 6 | 337 | No | Yes | Anterior repair | TVT + Anterior repair | ||

| Westermann et al. | 2016 | Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery | 1.49 | SS | 4 | 5 | 93 | No | Yes | Use of postop. vaginal pack | No use of postop. vaginal pack | ||

| Withagen et al.b | 2011 | Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 5.34 | S | 5 | 6 | 194 | No | Yes | Conventional colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Withagen et al.c | 2011 | British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 4.34 | S | 5 | 6 | 59 | No | Yes | Conventional colporrhaphy | Transvaginal mesh repair | ||

| Milani et al.c | 2011 | Journal of Sexual Medicine | 3.67 | SS | 3 | 6 | 59 | No | Yes | Conventional colporrhaphy | Trocar-guided Mesh | ||

| Yuk et al.a | 2012 | Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynaecology | 2.1 | S | 3 | 3 | 87 | No | N/A | 2-point mesh | 4-point mesh |

SS subspecialty (urogynaecology), S specialty (obs/gyn), G general, TVT tension free vaginal tape (retropubic tape), PDS polydioxanone

aStudies focused on surgical management of anterior repair solely, boriginal study, csecondary analysis

Trials were published between 1985 and 2017, with most being published in subspecialty journals (33/80; 41%). Trials were frequently published in journals with an impact factor <3 [median = 2.7; interquartile range (IQR) = 2.2–4.3] and were generally small (median = 93; IQR = 60–154). Ten trials (14%) declared commercial funding. The methodological quality and outcome reporting quality varied considerably between trials (Table 1). One hundred different outcomes were organised into 11 thematic domains. The three most commonly reported thematic domains were presence of symptoms posttreatment (50 trials, 28 outcomes; 28 outcome measures), prolapse treatment success rates (47 trials; 3 outcomes; 16 outcome measures) and perioperative complications (46 trials; 15 outcomes; 13 outcome measures) (Table 2). Commonly reported outcomes were anatomical prolapse stage (43 trials; 54%), commonly assessed using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) instrument (35 trials; 81%), QoL (25 trials; 31%); and intra- and postoperative complications (23 trials; 29%). Patient-reported outcomes were infrequently reported; for example, a minority of trials reported prolapse symptoms (9 trials; 11%), urinary symptoms (11 trials; 14%) and sexual dysfunction (14 trials; 17%) (Table 3). Eleven trials (14%) reported patient satisfaction.

Table 2.

Most commonly reported outcome domains

| Outcome domains | RCTs reporting on the domain | Outcomes reported | Outcome measures reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of symptoms posttreatment | 50 | 28 | 28 |

| Prolapse treatment success rate | 47 | 3 | 16 |

| Perioperative complications and observations | 46 | 15 | 13 |

| Quality of life and satisfaction with treatment | 40 | 5 | 25 |

| Treatment success evaluation | 15 | 11 | – |

| Postoperative catheterisation | 10 | 17 | 10 |

| Pain | 9 | 4 | 7 |

| Mesh-related outcomes | 8 | 3 | – |

RCT randomised controlled trial

Table 3.

Outcomes reported in 80 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating surgical management of anterior-compartment prolapse

| Outcomes | Reporting studies |

|---|---|

| Prolapse treatment success rate | |

| Anatomical prolapse stage | 43 |

| Composite anatomical/functional success rate | 3 |

| Urethral mobility | 1 |

| Perioperative complications and observations | |

| Complications intra-/postoperatively | 23 |

| Postoperative hospital stay length | 11 |

| Blood loss intraoperatively | 6 |

| Duration of operation | 6 |

| Quality and time of recovery | 4 |

| Postoperative nausea and vomiting | 3 |

| Bleeding postoperatively (with/out vaginal pack use) | 2 |

| Constipation preoperatively | 2 |

| Blood pressure | 2 |

| Blood transfusion indicated | 2 |

| Heart rate change | 2 |

| Consistency of bowel movement postoperatively | 1 |

| Intra- and postoperative morbidity | 1 |

| Time to first postoperative bowel movement | 1 |

| Time to mobilisation | 1 |

| Pain | |

| Postoperative pain | 8 |

| Intraoperative requirement of analgesics | 1 |

| Total analgesic consumption | 1 |

| Pain level associated with first postoperative bowel movement | 1 |

| Postoperative catheterisation | |

| Postoperative UTI | 5 |

| Recatheterisation rates | 5 |

| Postoperative catheterisation duration | 4 |

| First postvoid residual volume | 4 |

| Time to normal spontaneous voiding | 2 |

| Acute urinary retention | 1 |

| Bacterial count in the urine | 1 |

| Catheter blockage | 1 |

| Day of spontaneous voiding | 1 |

| Diagnostic accuracy of different voiding trial methods | 1 |

| Mean residual urine volume pre- and postoperatively | 1 |

| Prediction of voiding dysfunction lasting >7 days. | 1 |

| Prolonged catheterisation | 1 |

| Pyelectasia | 1 |

| Residual urine volume | 1 |

| Urinary retention prevention with intravesically administered prostaglandin-E2 | 1 |

| Urinary retention rates | 1 |

| Postoperative vaginal packing | |

| Bleeding postoperatively (with/out vaginal pack use) (compared with menstrual average) | 1 |

| Bleeding postoperatively (with/out vaginal pack use) | 1 |

| Presence of vaginal haematoma | 1 |

| Presence of vaginal infection | 1 |

| Bother related to the pack | 1 |

| Presence of symptoms posttreatment | |

| Sexual dysfunction symptoms | 14 |

| Urinary symptoms | 11 |

| Prolapse symptoms postoperatively | 9 |

| Dyspareunia | 6 |

| SUI postoperatively | 5 |

| De novo SUI postoperatively | 4 |

| Change in urinary symptoms (any) | 3 |

| Prolapse symptoms severity | 3 |

| De novo urinary urgency | 2 |

| Postoperative urinary symptoms | 2 |

| Urinary symptoms severity | 2 |

| Bowel symptoms | 2 |

| Faecal incontinence | 2 |

| Postoperative bowel symptoms | 2 |

| Change in incontinence rates | 1 |

| De novo urinary symptoms | 1 |

| De novo voiding difficulty | 1 |

| Urgency and urge urinary incontinence | 1 |

| Worsening urinary symptoms (any) | 1 |

| Obstructed defecation | 1 |

| Back pain improvement | 1 |

| Change in a pelvic symptom score | 1 |

| Change of vaginal symptoms | 1 |

| Symptomatic prolapse improvement | 1 |

| Time of prolapse recurrence | 1 |

| De novo dyspareunia | 1 |

| Sexual function in partner | 1 |

| QoL and satisfaction with treatment | |

| QoL and impact from symptoms evaluation | 25 |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment | 11 |

| Surgeon satisfaction with operation | 2 |

| Patient acceptability of preoperative bowel preparation | 1 |

| Surgeon—ease of procedure | 1 |

| Treatment success evaluation | |

| Symptoms—presence posttreatment | 5 |

| Subjective cure rates | 3 |

| Cure of SUI postoperatively | 3 |

| Reoperation rates | 3 |

| Symptoms—bother change | 2 |

| Retreatment success rates | 1 |

| Symptom improvement | 1 |

| Functional recurrence | 1 |

| Healing abnormalities | 1 |

| Need for subsequent anti-incontinence surgery | 1 |

| Treatment of overactive bladder | 1 |

| Mesh-related outcomes | |

| Mesh erosion | 6 |

| Mesh shrinkage | 2 |

| Degree of morbidity in mesh vs. native tissue | 1 |

| Cost/effectiveness | |

| Cost-effectiveness of treatment | 2 |

| Cost of procedure | 1 |

| Recruitment feasibility | |

| Number of patients agreed to participate | 1 |

| Number of eligible patients | 1 |

| Physician acceptance and protocol | 1 |

| Rate of recruitment compliance | 1 |

UTI urinary tract infection, SUI stress urinary incontinence, QoL quality of life

Forty-two randomised trials compared native tissue or biological graft versus mesh repair for anterior vaginal prolapse. Mesh-related complications were rarely reported: seven trials (9%) reported mesh erosion, six (7%) reported mesh shrinkage and a single trial (1%) reported the degree of morbidity associated with mess Only three trials (4%) evaluated cost effectiveness. One hundred and twelve different outcome measures wer reported (Table 4). Forty-six questionnaires were used as measurement instruments, most of which were validated (45; 98%). Anterior prolapse symptoms were measured using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12) (13 trials; 16%), Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6) (11 trials; 14%) and the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) (9 trials; 11%). QoL was measured using the Prolapse Quality of Life (P-QoL) (10 trials; 12%), Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire Short Form (PFIQ-7) (8 trials; 10%) and the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Short Form (IIQ-7) (6 trials; 7%). Table 5 summarises our main findings, demonstrating the most frequently reported outcomes. It reveals the significant discrepancies in terms of outcome reporting.

Table 4.

Outcome measures reported in 80 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating surgical management of anterior-compartment prolapse

| Outcomes | No of reporting studies |

|---|---|

| Prolapse treatment success rate | |

| Anatomical success rate POP-Q < 2 | 23 |

| Anatomical success rate (POP-Q ≤ 1) | 5 |

| Anatomical success rate (postoperative POP-Q stage improvement) | 5 |

| Anatomical success rate (POP above hymen) | 3 |

| Anatomical success rate POP-Q ≤ 2 | 2 |

| Anatomical success rate (POP-Q < 2 vs. POP-Q ≤ 1) | 1 |

| Anatomical success rate POP-Q Index (POP-Q-I) = 0 | 1 |

| Anatomical success rate (postoperative POP-Q + BW stage improvement) | 1 |

| Anatomical success rate (cotton swab mobility test) | 1 |

| Composite success rate (POP-Q < 2 + UDI question 16 negative | 1 |

| Composite success rate (POP above hymen + VAS >20 (0–100 scale)) | 1 |

| Composite success rate - (POP above hymen + no symptoms) | 1 |

| Composite success rate - (apex below levator plate + no symptoms) | 1 |

| Denovo POP in untreated compartments (POP-Q ≥ 2) | 1 |

| Denovo POP in untreated compartments (POP ≥ hymen) | 1 |

| Recurrence rate of POP (halfway BW stage change) | 1 |

| Perioperative complications and observations | |

| Postoperative hospital stay length (days) | 11 |

| Blood loss (ml) | 8 |

| Duration of operation (min) | 6 |

| PONV (postoperative nausea and vomiting), visual analogue scale [VAS (0–10)] | 2 |

| PONV scale | 2 |

| PONV QoR (quality of recovery) score > 50 | 2 |

| Recovery time (days) | 2 |

| PONV intensity score [QoR (0–40)] | 1 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 1 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 1 |

| Consistency of bowel movement (Bristol stool scale) | 1 |

| Constipation perioperatively (Rome III constipation questionnaire) | 1 |

| Time to mobilisation (days) | 1 |

| Pain | |

| VAS (0–10) | 5 |

| VAS (0–100) | 2 |

| VAS (not specified) | 2 |

| Mcgill pain questionnaire | 2 |

| Verbal numerical pain scale (0–10) | 1 |

| Baudelocque’s questionnaire | 1 |

| Nonvalidated questionnaire (0–3) | 1 |

| Postoperative catheterisation | |

| Postoperative catheterisation duration (days) | 4 |

| Day of spontaneous voiding (days) | 3 |

| Bacterial count in the urine | 1 |

| Residual urine volume (ml) | 1 |

| First PVR (postvoid residual volume) > 150 ml | 1 |

| First PVR > 1500 ml | 1 |

| Mean residual urine volume pre- and postoperatively (ml) | 1 |

| Recatheterisation if PVR >200 ml | 1 |

| Prediction of voiding dysfunction >7 days (positive predictive value) | 1 |

| Diagnostic accuracy of two voiding trial methods (sensitivity/specificity) | 1 |

| Postoperative vaginal packing | |

| Bleeding postoperatively (with/out vaginal pack use) (compared with menstrual average) | 1 |

| Bleeding postoperatively (with/out vaginal pack use) [FBC change and volume (ml)] | 1 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 1 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 1 |

| Blood transfusion indicated (yes/no) | 1 |

| Vaginal haematoma (TVUSS) | 1 |

| Vaginal infection (HVS) | 1 |

| Bother related to the pack (VAS 0–100) | 1 |

| Presence of symptoms posttreatment | |

| PISQ-12 (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Urinary Incontinence–Sexual Questionnaire) | 13 |

| UDI-6 (Urogenital Distress Inventory) | 11 |

| PFDI-20 (Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory) | 9 |

| SUI urodynamic studies | 7 |

| DDI (Defecatory Distress Inventory) | 5 |

| ICIQ-UI SF (International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Short Form) | 4 |

| SUI cough test (presence of leakage) | 4 |

| FSFI (Female Sexual Function Index) | 2 |

| ICIQ-BS (International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Bowel Symptoms) | 2 |

| PGI-I (Patient Global Impression of Improvement) | 2 |

| OAB-V8 (Overactive Bladder-Validated 8-question) | 2 |

| POPDI-6 (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory) | 2 |

| POP-SS (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Severity of Symptoms) | 2 |

| UDI-I (Urogenital Distress Inventory–Irritative) | 2 |

| UDI-O (Urogenital Distress Inventory-Obstructive) | 2 |

| UDI-S (Urogenital Distress Inventory–Stress) | 2 |

| AUASS [American Urological Association Symptom Score (urinary)] | 1 |

| CRADI-8 (Colorectal–Anal Distress Inventory) | 1 |

| CRAIQ-7 (Colorectal–Anal Impact Questionnaire) | 1 |

| Danish prolapse questionnaire | 1 |

| ICIQ-VS (International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Vaginal Symptoms) | 1 |

| MESAAQ (Medical Epidemiologic and Social Aspects of Ageing Questionnaire) | 1 |

| MHU (French Urinary Dysfunction Measurement Scale) | 1 |

| MSHQ (Male Sexual Health Questionnaire) | 1 |

| PGI-S (Patient Global Impression of Severity) | 1 |

| QS-F (Sexual Quotient–Female Version) | 1 |

| SUI number of daily pads | 1 |

| Impact on quality of life | |

| P-QoL (Prolapse Quality of Life) | 10 |

| PFIQ-7 (Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire–Short Form) | 8 |

| IIQ-7 (Incontinence Impact Questionnaire–Short Form) | 6 |

| ICIQ-UI SF (International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Symptoms) | 4 |

| ICIQ-VS (International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Vaginal Symptoms) | 3 |

| KHQ (King’s Health Questionnaire) | 3 |

| UIQ-7 (Urogenital Impact Questionnaire) | 3 |

| DDI (Defecatory Distress Inventory) | 2 |

| EQ5D [Quality of Life (EuroQol)] | 2 |

| POPIQ-7 (Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire–Prolapse) | 2 |

| VAS (0–10) | 2 |

| CRAIQ-7 (Colorectal–Anal Impact Questionnaire) | 1 |

| PSI-QOL (Prolapse Symptom Inventory and Quality of Life Questionnaire) | 1 |

| SF-12 (12-Item Short-Form Health Survey) | 1 |

| SF-36 (36-Item Short-Form Health Survey) | 1 |

| Satisfaction | |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment, VAS (0–10) | 3 |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment, PGI (Patient Global Improvement) | 3 |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment (yes/no) | 3 |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment, VAS (0–100) | 2 |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment, VAS (0–4) | 1 |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment, custom (0–5) | 1 |

| Patient acceptability of preoperative bowel preparation, VAS) (0–4) | 1 |

| Surgeon satisfaction with preoperative bowel preparation, Likert scale (0–4) | 1 |

| Surgeon ease to perform operation, Likert scale (0–4) | 1 |

| Surgeon’s satisfaction with operation, VAS (0–100) | 1 |

| Cost/effectiveness | |

| Incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) | 2 |

| Cost of procedure (US$) | 1 |

TVUSS transvaginal ultrasound scan, HVS high vaginal swab, FBC full blood count

Table 5.

Reported outcomes by by more than eight studies with greater than 93 participants (median value)

| Study | Sample size (N) | Outcomes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomical prolapse stage | Quality of life and impact from symptoms | Complications intra-/postoperatively | Sexual dysfunction symptoms | Postoperative hospital stay length | Urinary symptoms | Patient satisfaction with treatment | Prolapse symptoms postoperatively | Postoperative pain | ||

| Glazener et al. | 1352 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Altman et al. | 389 | x | x | x | ||||||

| Wei et al. | 337 | x | x | |||||||

| Weemhoff et al. | 246 | x | ||||||||

| Nieminen et al. | 203 | x | x | |||||||

| Hiltunen et al. | 202 | x | x | |||||||

| Farthmann et al. | 200 | x | x | x | ||||||

| Kamilya et al. | 200 | x | ||||||||

| Withagen et al. | 194 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Natale et al. | 190 | x | x | |||||||

| Thiagamoorthy et al. | 190 | x | ||||||||

| da Silveira et al. | 184 | x | x | |||||||

| Borstad et al. | 184 | x | ||||||||

| Van et al. | 179 | x | ||||||||

| Sand et al. | 161 | x | ||||||||

| Rudnicki et al. | 160 | x | x | x | ||||||

| Gandhi et al. | 154 | x | ||||||||

| Ballard et al. | 150 | x | ||||||||

| de Tayrac et al. | 147 | x | x | x | ||||||

| Carey et al. | 139 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Rudnicki et al. | 138 | x | ||||||||

| Dahlgren et al. | 135 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Stekkinger et al. | 126 | x | ||||||||

| Vollebregt et al. | 125 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Qatawneh et al. | 116 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Weber et al. | 114 | x | x | |||||||

| Chmielewski et al. | 114 | x | ||||||||

| Gupta et al. | 106 | x | x | |||||||

| Tamanini et al. | 100 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Hakvoort | 100 | x | ||||||||

| Menefee et al. | 99 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Ek et al. | 99 | x | ||||||||

| Guerette et al. | 94 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Westermann et al. | 93 | x | x | |||||||

| Studies not included | <93 | 19 | 16 | 11 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Total studies | 43 | 25 | 23 | 14 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 8 | |

We observed a moderate correlation between outcome reporting quality and year of publication in the univariate analysis (r 0.458; p < .001) and study quality (r 0.409; p < .001) (Table 6). The latter index significantly affected outcome reporting in the multivariate logistic regression (β = 0.412; p = .018).

Table 6.

Univariate and multivariate correlation with outcome reporting quality

| Factor | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | P value | Beta | P value | |

| Study quality (Jadad) | 00.409 | <0.001 | 0.412 | 0.018 |

| Journal IF | 0.053 | 0.643 | 0.078 | 0.306 |

| Year of publication | 0.458 | <0.001 | 0.149 | 0.295 |

| Study size | 0.215 | 0.051 | 0.008 | 0.961 |

| Journal type | – | – | 0.024 | 0.852 |

| Commercial funding | – | – | −0.013 | 0.918 |

| Validated questionnaire | – | – | 1.310 | 0.196 |

Bolded data statistically significant

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This study demonstrated considerable variation in outcome and outcome-measure reporting across published trials evaluating surgical interventions for anterior-compartment prolapse. Commonly reported outcomes included normalised anatomy, QoL and pain. Patient-reported outcomes were infrequently reported, and a minority of trials reported on patient satisfaction. Mesh-related complications, including erosion, shrinkage and morbidity, were rarely reported. Forty-five different questionnaires were used as measurement instruments; most were validated. Only a few trials considered cost effectiveness.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our systematic review include originality, a rigorous search strategy and methodological robustness. To our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to evaluate outcomes and outcome measures in anterior-compartment prolapse trials. Study screening and selection and data extraction and assessment were conducted independently by two researchers to avoid bias. Our findings were based on outcome reporting in published randomised trials. The exclusion of observational studies may have potentially missed outcomes related to harm [89, 90] and selecting only trials reported in English may have introduced selection bias. The variation of interventions for correcting anterior prolapse may have caused variation in outcome and outcome-measure reporting.

Interpretation

Randomised trials require a substantial investment of resources. Variation in outcomes and outcome measures limits the ability of trials to be combined with meta-analyses, which contributes to inevitable research waste, as identified in various areas of women’s health, including childbirth trauma, endometriosis and pre-eclampsia [91–94]. This systematic review is the first step in the development of a minimum data set, which will be known as a core outcome set. It will be developed with reference to methods described by the COMET initiative, Core Outcomes in Women’s and Newborn Health (CROWN) initiative and other core-outcome-set development studies, including those on endometriosis, pre-eclampsia, termination of pregnancy, Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome and neonatal medicine [95–99].

CHORUS is aiming to work towards a standardisation of outcomes and outcome measures and subsequently establish a minimum of standards in research and clinical practice. Chorus working groups are currently evaluating reported outcomes in all areas of urogyneacology and have been registered with the COMET (registration number 981, http://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/details/981) and CROWN initiatives. Each working group has carefully considered the scope of its work [100], and CHORUS will replicate the success of other international initiatives that have standardised outcome selection, collection and reporting across preterm birth research [101].

In the absence of a core outcome, we recommend QoL (incorporating sexual function), postoperative complications, patient and physician satisfaction and postoperative prolapse, bladder and bowel symptoms be collected across all anterior prolapse trials.

Conclusion

Anterior-compartment prolapse trials report many different outcomes and outcome measures and often neglect to report important safety outcomes. Developing, disseminating and implementing a core outcome set will help address these issues.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors report that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Constantin M. Durnea, Phone: +44 1372 735 735, Email: costea.durnea@gmail.com

Stergios K. Doumouchtsis, Email: sdoum@yahoo.com

References

- 1.Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women's Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1160–1166. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH, Wilson D. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. BJOG. 2000;107(12):1460–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durnea CM, Khashan AS, Kenny LC, Durnea UA, Smyth MM, O'Reilly BA. Prevalence, etiology and risk factors of pelvic organ prolapse in premenopausal primiparous women. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(11):1463–1470. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2382-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Brown J. Surgery for women with anterior compartment prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD004014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glazener CM, Breeman S, Elders A, Hemming C, Cooper KG, Freeman RM, et al. Mesh, graft, or standard repair for women having primary transvaginal anterior or posterior compartment prolapse surgery: two parallel-group, multicentre, randomised, controlled trials (PROSPECT) Lancet. 2017;389(10067):381–392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson NK, Jayaratne YS. Methodological challenges when performing a systematic review. Eur J Orthod. 2015;37(3):248–250. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjv022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy J, Bhattacharya S, Herman M, Mol B, Vail A, Wilkinson J, et al. Reducing research waste in benign gynaecology and fertility research. BJOG. 2017;124(3):366–369. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephen H. Halpern (Editor) MJDE. Evidence-Based Obstetric Anesthesia (Appendix: Jadad scale for reporting randomized controlled trials.): Blackwell Publishing; p.237 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/9780470988343.app1/asset/app1.pdf?v=1&t=jbcu6wdr&s=4f0ac0743368957ad4e80e988495338ca8e8f985; 2005.

- 9.Harman NL, Bruce IA, Callery P, Tierney S, Sharif MO, O’Brien K, et al. MOMENT – Management of Otitis Media with Effusion in Cleft Palate: protocol for a systematic review of the literature and identification of a core outcome set using a Delphi survey. Trials. [journal article] 2013;14(1):70. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altman D, Vayrynen T, Engh ME, Axelsen S, Falconer C. Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1826–1836. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antosh DD, Gutman RE, Park AJ, Sokol AI, Peterson JL, Kingsberg SA, et al. Vaginal dilators for prevention of dyspareunia after prolapse surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(6):1273–1280. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182932ce2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballard AC, Parker-Autry CY, Markland AD, Varner RE, Huisingh C, Richter HE. Bowel preparation before vaginal prolapse surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):232–238. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benson JT, Lucente V, McClellan E. Vaginal versus abdominal reconstructive surgery for the treatment of pelvic support defects: a prospective randomized study with long-term outcome evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(6):1418–1421. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borstad E, Abdelnoor M, Staff AC. Kulseng-Hanssen S. Surgical strategies for women with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(2):179–186. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bray R, Cartwright R, Digesu A, Fernando R, Khullar V. A randomised controlled trial comparing immediate versus delayed catheter removal following vaginal prolapse surgery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carey M, Higgs P, Goh J, Lim J, Leong A, Krause H, et al. Vaginal repair with mesh versus colporrhaphy for prolapse: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2009;116(10):1380–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choe JM, Ogan K, Battino BS. Antimicrobial mesh versus vaginal wall sling: a comparative outcomes analysis. J Urol. 2000;163(6):1829–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colombo M, Vitobello D, Proietti F, Milani R. Randomised comparison of Burch colposuspension versus anterior colporrhaphy in women with stress urinary incontinence and anterior vaginal wall prolapse. BJOG. 2000;107(4):544–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Da Silveira Dos Reis Brandao S, Haddad JM, de Jarmy-Di Bella ZI, Nastri F, Kawabata MG, da Silva Carramao S, et al. Multicenter, randomized trial comparing native vaginal tissue repair and synthetic mesh repair for genital prolapse surgical treatment. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(3):335–342. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2501-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahlgren E, Kjolhede P. Long-term outcome of porcine skin graft in surgical treatment of recurrent pelvic organ prolapse. An open randomized controlled multicenter study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(12):1393–1401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delroy CA, Castro Rde A, Dias MM, Feldner PC, Jr, Bortolini MA, Girao MJ, et al. The use of transvaginal synthetic mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse repair: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(11):1899–1907. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2092-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dias MM, De ACR, Bortolini MA, Delroy CA, Martins PC, Girao MJ, et al. Two-years results of native tissue versus vaginal mesh repair in the treatment of anterior prolapse according to different success criteria: a randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35(4):509–514. doi: 10.1002/nau.22740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Tayrac R, Cornille A, Eglin G, Guilbaud O, Mansoor A, Alonso S, et al. Comparison between trans-obturator trans-vaginal mesh and traditional anterior colporrhaphy in the treatment of anterior vaginal wall prolapse: results of a French RCT. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(10):1651–1661. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ek M, Altman D, Gunnarsson J, Falconer C, Tegerstedt G. Clinical efficacy of a trocar-guided mesh kit for repairing lateral defects. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(2):249–254. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1833-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ek M, Tegerstedt G, Falconer C, Kjaeldgaard A, Rezapour M, Rudnicki M, et al. Urodynamic assessment of anterior vaginal wall surgery: a randomized comparison between colporraphy and transvaginal mesh. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(4):527–531. doi: 10.1002/nau.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Nazer MA, Gomaa IA, Ismail Madkour WA, Swidan KH, El-Etriby MA. Anterior colporrhaphy versus repair with mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a comparative clinical study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286(4):965–972. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farthmann J, Watermann D, Niesel A, Funfgeld C, Kraus A, Lenz F, et al. Lower exposure rates of partially absorbable mesh compared to nonabsorbable mesh for cystocele treatment: 3-year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(5):749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldner PC, Jr, Castro RA, Cipolotti LA, Delroy CA, Sartori MG, Girao MJ. Anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial of SIS graft versus traditional colporrhaphy. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(9):1057–1063. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldner PC, Jr, Delroy CA, Martins SB, Castro RA, Sartori MG, Girao MJ. Sexual function after anterior vaginal wall prolapse surgery. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012;67(8):871–875. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(08)03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glavind K, Morup L, Madsen H, Glavind J. A prospective, randomised, controlled trial comparing 3 hour and 24 hour postoperative removal of bladder catheter and vaginal pack following vaginal prolapse surgery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(9):1122–1125. doi: 10.1080/00016340701505317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gandhi S, Goldberg RP, Kwon C, Koduri S, Beaumont JL, Abramov Y, et al. A prospective randomized trial using solvent dehydrated fascia lata for the prevention of recurrent anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1649–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geller EJ, Hankins KJ, Parnell BA, Robinson BL, Dunivan GC. Diagnostic accuracy of retrograde and spontaneous voiding trials for postoperative voiding dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):637–642. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318229e8dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glazener C, Breeman S, Elders A, Hemming C, Cooper K, Freeman R, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of surgical options for the management of anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall prolapse: two randomised controlled trials within a comprehensive cohort study - results from the PROSPECT study. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(95):1–452. doi: 10.3310/hta20950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guerette NL, Peterson TV, Aguirre OA, Vandrie DM, Biller DH, Davila GW. Anterior repair with or without collagen matrix reinforcement: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(1):59–65. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a81b41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta Bindiya, Vaid Neelam B, Suneja Amita, Guleria Kiran, Jain Sandhya. Anterior vaginal prolapse repair: A randomised trial of traditional anterior colporrhaphy and self-tailored mesh repair. South African Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2014;20(2):47. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakvoort RA, Elberink R, Vollebregt A, Ploeg T, Emanuel MH. How long should urinary bladder catheterisation be continued after vaginal prolapse surgery? A randomised controlled trial comparing short term versus long term catheterisation after vaginal prolapse surgery. BJOG. 2004;111(8):828–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henn EW, Nondabula T, Juul L. Effect of vaginal infiltration with ornipressin or saline on intraoperative blood loss during vaginal prolapse surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(3):407–412. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2821-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiltunen R, Nieminen K, Takala T, Heiskanen E, Merikari M, Niemi K, et al. Low-weight polypropylene mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 2):455–462. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000261899.87638.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nieminen K, Hiltunen R, Takala T, Heiskanen E, Merikari M, Niemi K, et al. Outcomes after anterior vaginal wall repair with mesh: a randomized, controlled trial with a 3 year follow-up. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(3):235 e1–235 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nieminen K, Hiltunen R, Heiskanen E, Takala T, Niemi K, Merikari M, et al. Symptom resolution and sexual function after anterior vaginal wall repair with or without polypropylene mesh. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(12):1611–1616. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang CC, Ou CS, Yeh GP, Der Tsai H, Sun MJ. Optimal duration of urinary catheterization after anterior colporrhaphy. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(4):485–491. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hviid U, Hviid TV, Rudnicki M. Porcine skin collagen implants for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomised prospective controlled study. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(5):529–534. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iglesia CB, Sokol AI, Sokol ER, Kudish BI, Gutman RE, Peterson JL, et al. Vaginal mesh for prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 Pt 1):293–303. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e7d7f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamilya G, Seal SL, Mukherji J, Bhattacharyya SK, Hazra A. A randomized controlled trial comparing short versus long-term catheterization after uncomplicated vaginal prolapse surgery. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(1):154–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khalil I, Itani SE, Naja Z, Naja AS, Ziade FM, Ayoubi JM, et al. Nerve stimulator-guided pudendal nerve block vs general anesthesia for postoperative pain management after anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair: a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Anesth. 2016;34:668–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kringel U, Reimer T, Tomczak S, Green S, Kundt G, Gerber B. Postoperative infections due to bladder catheters after anterior colporrhaphy: a prospective, randomized three-arm study. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(12):1499–1504. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lamblin G, Van-Nieuwenhuyse A, Chabert P, Lebail-Carval K, Moret S, Mellier G. A randomized controlled trial comparing anatomical and functional outcome between vaginal colposuspension and transvaginal mesh. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(7):961–970. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Costantini E, Lazzeri M, Bini V, Del Zingaro M, Zucchi A, Porena M. Burch colposuspension does not provide any additional benefit to pelvic organ prolapse repair in patients with urinary incontinence: a randomized surgical trial. J Urol. 2008;180(3):1007–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lose G, Lindholm P. Prophylactic phenoxybenzamine in the prevention of postoperative retention of urine after vaginal repair: a prospective randomized double-blind trial. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1985;23(4):315–320. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(85)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Madhuvrata P, Glazener C, Boachie C, Allahdin S, Bain C. A randomised controlled trial evaluating the use of polyglactin (Vicryl) mesh, polydioxanone (PDS) or polyglactin (Vicryl) sutures for pelvic organ prolapse surgery: outcomes at 2 years. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31(5):429–435. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.576282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McNanley A, Perevich M, Glantz C, Duecy EE, Flynn MK, Buchsbaum G. Bowel function after minimally invasive urogynecologic surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18(2):82–85. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3182455529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Menefee SA, Dyer KY, Lukacz ES, Simsiman AJ, Luber KM, Nguyen JN. Colporrhaphy compared with mesh or graft-reinforced vaginal paravaginal repair for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(6):1337–1344. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318237edc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meschia M, Pifarotti P, Spennacchio M, Buonaguidi A, Gattei U, Somigliana E. A randomized comparison of tension-free vaginal tape and endopelvic fascia plication in women with genital prolapse and occult stress urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(3):609–613. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minassian VA, Parekh M, Poplawsky D, Gorman J, Litzy L. Randomized controlled trial comparing two procedures for anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33(1):72–77. doi: 10.1002/nau.22396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miranda V, Alarab M, Murphy K, Pineda R, Drutz H, Lovatsis D. Randomized controlled trial of cystocele plication risks: a pilot study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(11):1146–1149. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)35083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Natale F, La Penna C, Padoa A, Agostini M, De Simone E, Cervigni M. A prospective, randomized, controlled study comparing Gynemesh, a synthetic mesh, and Pelvicol, a biologic graft, in the surgical treatment of recurrent cystocele. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(1):75–81. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0732-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park HK, Paick SH, Lho YS, Choo GY, Kim HG, Choi J. Lack of effect of concomitant stage II cystocele repair on lower urinary tract symptoms and surgical outcome after tension-free vaginal tape procedure: randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(7):1123–1126. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1961-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pauls RN, Crisp CC, Oakley SH, Westermann LB, Mazloomdoost D, Kleeman SD, et al. Effects of dexamethasone on quality of recovery following vaginal surgery: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(5):718 e1–718 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Ploeg JM, Oude Rengerink K, van der Steen A, van Leeuwen JH, van der Vaart CH, Roovers JP. Vaginal prolapse repair with or without a midurethral sling in women with genital prolapse and occult stress urinary incontinence: a randomized trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(7):1029–1038. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2924-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qatawneh FA-K A, Saleh S, Thekrallah F, Bata M, Sumreen I, Al-Mustafa M. Transvaginal cystocele repair using tension-free polypropylene mesh at the time of sacrospinous colpopexy for advanced uterovaginal prolapse: a prospective randomised study. Gynecol Surg. 2013;10:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quadri NN G, Spreafico C, Belloni C, Barisani D, Lahodny J. Intravesical prostaglandin e2 effectiveness in the prevention of urinary retention after transvaginal reconstruction of the pubo-cervical fascia and short arm sling according to Lahodny: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Urogynaecologia International Journal. 2000;14(1):15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robert M, Girard I, Brennand E, Tang S, Birch C, Murphy M, et al. Absorbable mesh augmentation compared with no mesh for anterior prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):288–294. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rudnicki M, Laurikainen E, Pogosean R, Kinne I, Jakobsson U, Teleman P. Anterior colporrhaphy compared with collagen-coated transvaginal mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2013;121(1):102–111. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rudnicki M, Laurikainen E, Pogosean R, Kinne I, Jakobsson U, Teleman P. A 3-year follow-up after anterior colporrhaphy compared with collagen-coated transvaginal mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2016;123(1):136–142. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sand PK, Koduri S, Lobel RW, Winkler HA, Tomezsko J, Culligan PJ, et al. Prospective randomized trial of polyglactin 910 mesh to prevent recurrence of cystoceles and rectoceles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(7):1357–1362. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.115118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schierlitz L, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A, De Souza A, Murray C, Thomas E, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery with and without tension-free vaginal tape in women with occult or asymptomatic urodynamic stress incontinence: a randomised controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(1):33–40. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Segal JL, Owens G, Silva WA, Kleeman SD, Pauls R, Karram MM. A randomized trial of local anesthesia with intravenous sedation vs general anesthesia for the vaginal correction of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(7):807–812. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sivaslioglu AA, Unlubilgin E, Dolen I. A randomized comparison of polypropylene mesh surgery with site-specific surgery in the treatment of cystocoele. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(4):467–471. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0465-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stekkinger E, van der Linden PJ. A comparison of suprapubic and transurethral catheterization on postoperative urinary retention after vaginal prolapse repair: a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2011;72(2):109–116. doi: 10.1159/000323827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tamanini JT, Tamanini MM, Castro RC, Feldner PC, Jr, Castro Rde A, Sartori MG, et al. Treatment of anterior vaginal wall prolapse with and without polypropylene mesh: a prospective, randomized and controlled trial - part I. Int Braz J Urol. 2013;39(4):519–530. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2013.04.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tamanini JT, Castro RC, Tamanini JM, Feldner PC, Jr, Castro Rde A, Sartori MG, et al. Treatment of anterior vaginal wall prolapse with and without polypropylene mesh: a prospective, randomized and controlled trial - part II. Int Braz J Urol. 2013;39(4):531–541. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2013.04.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tamanini JT, de Oliveira Souza Castro RC, Tamanini JM, Castro RA, Sartori MG, Girao MJ. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of the treatment of anterior vaginal wall prolapse: medium term followup. J Urol. 2015;193(4):1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tantanasis T, Giannoulis C, Daniilidis A, Papathanasiou K, Loufopoulos A, Tzafettas J. Anterior vaginal wall reconstruction: anterior colporrhaphy reinforced with tension free vaginal tape underneath bladder base. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(4):464–468. doi: 10.1080/00016340801991003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thiagamoorthy G, Khalil A, Cardozo L, Srikrishna S, Leslie G, Robinson D. The value of vaginal packing in pelvic floor surgery: a randomised double-blind study. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(5):585–591. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2264-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tincello DG, Kenyon S, Slack M, Toozs-Hobson P, Mayne C, Jones D, et al. Colposuspension or TVT with anterior repair for urinary incontinence and prolapse: results of and lessons from a pilot randomised patient-preference study (CARPET 1) BJOG. 2009;116(13):1809–1814. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Turgal M, Sivaslioglu A, Yildiz A, Dolen I. Anatomical and functional assessment of anterior colporrhaphy versus polypropylene mesh surgery in cystocele treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170(2):555–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van Der Steen Annemarie, Detollenaere Renee, Den Boon Jan, Van Eijndhoven Hugo. One-day versus 3-day suprapubic catheterization after vaginal prolapse surgery: a prospective randomized trial. International Urogynecology Journal. 2011;22(5):563–567. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1358-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vollebregt A, Fischer K, Gietelink D, van der Vaart CH. Primary surgical repair of anterior vaginal prolapse: a randomised trial comparing anatomical and functional outcome between anterior colporrhaphy and trocar-guided transobturator anterior mesh. BJOG. 2011;118(12):1518–1527. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vollebregt A, Fischer K, Gietelink D, van der Vaart CH. Effects of vaginal prolapse surgery on sexuality in women and men; results from a RCT on repair with and without mesh. J Sex Med. 2012;9(4):1200–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR, Ballard LA. Anterior colporrhaphy: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(6):1299–1304. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.119081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chmielewski Lauren, Walters Mark D., Weber Anne M., Barber Matthew D. Reanalysis of a randomized trial of 3 techniques of anterior colporrhaphy using clinically relevant definitions of success. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;205(1):69.e1-69.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weemhoff M, Wassen MM, Korsten L, Serroyen J, Kampschoer PH, Roumen FJ. Postoperative catheterization after anterior colporrhaphy: 2 versus 5 days. A multicentre randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(4):477–483. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1304-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wei John T., Nygaard Ingrid, Richter Holly E., Nager Charles W., Barber Matthew D., Kenton Kim, Amundsen Cindy L., Schaffer Joseph, Meikle Susan F., Spino Cathie. A Midurethral Sling to Reduce Incontinence after Vaginal Prolapse Repair. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(25):2358–2367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Westermann Lauren B., Crisp Catrina C., Oakley Susan H., Mazloomdoost Donna, Kleeman Steven D., Benbouajili Janine M., Ghodsi Vivian, Pauls Rachel N. To Pack or Not to Pack? A Randomized Trial of Vaginal Packing After Vaginal Reconstructive Surgery. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery. 2016;22(2):111–117. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Withagen MI, Milani AL, den Boon J, Vervest HA, Vierhout ME. Trocar-guided mesh compared with conventional vaginal repair in recurrent prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):242–250. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318203e6a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Withagen MI, Milani AL, de Leeuw JW, Vierhout ME. Development of de novo prolapse in untreated vaginal compartments after prolapse repair with and without mesh: a secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2012;119(3):354–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Milani AL, Withagen MI, The HS, Nedelcu-van der Wijk I, Vierhout ME. Sexual function following trocar-guided mesh or vaginal native tissue repair in recurrent prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. J Sex Med. 2011;8(10):2944–2953. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yuk JS, Jin CH, Yi KW, Kim T, Hur JY, Shin JH. Anterior transobturator polypropylene mesh in the correction of cystocele: 2-point method vs 4-point method. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(6):737–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.08.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Perry H, Duffy JMN, Umadia O, Khalil A. Outcome reporting across randomised trials and observational studies evaluating treatments for twin-twin transfusion syndrome: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Duffy JMN, Hirsch M, Pealing L, Showell M, Khan KS, Ziebland S, McManus RJ. Inadequate safety reporting in pre-eclampsia trials: a systematic evaluation. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017;125(7):795–803. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pergialiotis V DC, Duffy JMN, Elfituri A, Doumouchtsis S. Do we need a core outcome sets for childbirth trauma research? A systematic review of outcome reporting in randomised controlled trials evaluating the management of childbirth trauma. Accepted by BJOG: International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 92.Hirsch M, Duffy JMN, Kusznir JO, Davis CJ, Plana MN, Khan KS. Variation in outcome reporting in endometriosis trials: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):452–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Duffy JMN, Hirsch M, Gale C, Pealing L, Kawsar A, Showell M, et al. A systematic review of primary outcomes and outcome-measure reporting in randomized trials evaluating treatments for pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;139(3):262–267. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Duffy J, Hirsch M, Kawsar A, Gale C, Pealing L, Plana MN, et al. Outcome reporting across randomised controlled trials evaluating therapeutic interventions for pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2017;124(12):1829–1839. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Duffy JMN, Rolph R, Gale C, Hirsch M, Khan KS, Ziebland S, McManus RJ. Core outcome sets in women's and newborn health: a systematic review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017;124(10):1481–1489. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Duffy JM, Van’t Hooft J, Gale C, Brown M, Grobman W, Fitzpatrick R, et al. A protocol for developing, disseminating, and implementing a core outcome set for pre-eclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2016;6(4):274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Whitehouse KC, Kim CR, Ganatra B, Duffy JMN, Blum J, Brahmi D, et al. Standardizing abortion research outcomes (STAR): a protocol for developing, disseminating and implementing a core outcome set for medical and surgical abortion. Contraception. 2017;95(5):437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Khalil A, Perry H, Duffy J, Reed K, Baschat A, Deprest J, et al. Twin-twin transfusion syndrome: study protocol for developing, disseminating, and implementing a core outcome set. Trials. 2017;18(1):325. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Webbe J, Brunton G, Ali S, Duffy JM, Modi N, Gale C. Developing, implementing and disseminating a core outcome set for neonatal medicine. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2017;1(1):e000048. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Duffy JMN, McManus RJ. Influence of methodology upon the identification of potential core outcomes: recommendations for core outcome set developers are needed. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2016;123(10):1599–1599. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.van 't Hooft J, Duffy JM, Daly M, Williamson PR, Meher S, Thom E, et al. A Core outcome set for evaluation of interventions to prevent preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):49–58. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]