Abstract

Background

Small colony and capnophilic variant cases have been separately reported, but there has been no reports of their simultaneous presence in one isolate. We report a case of Escherichia coli with coexpressed small colony and capnophilic phenotypes causing misidentification in automated biochemical kits and non-reactions in antimicrobial susceptibility test cards.

Case presentation

An 86-year-old woman developed urinary tract infection from a strain of Escherichia coli with SCV and capnophilic phenotypes in co-existence. This strain did not grow without the presence of CO2, and therefore proper identification from automated system was not possible. 16 s rRNA sequencing and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry was able to identify the bacteria.

Conclusion

As these strains do not grow on culture parameters defined by CLSI or on automated systems, proper identification using alternative methods are necessary.

Keywords: Small colony variant, Capnophilic, Escherichia coli, Misidentification

Background

Small colony variants (SCV) can be defined as a naturally occurring sub-population of bacteria characterized by their reduced colony size and distinct biochemical properties [1]. Capnophilic E. coli, which thrive in the presence of high concentrations of carbon dioxide, have rarely been reported [2, 3]. SCV and capnophilic variant cases have never been reported in co-existence. Herein, we report the first case of E. coli with coexpressed SCV and capnophilic phenotypes isolated from a urinary tract infection.

Case report

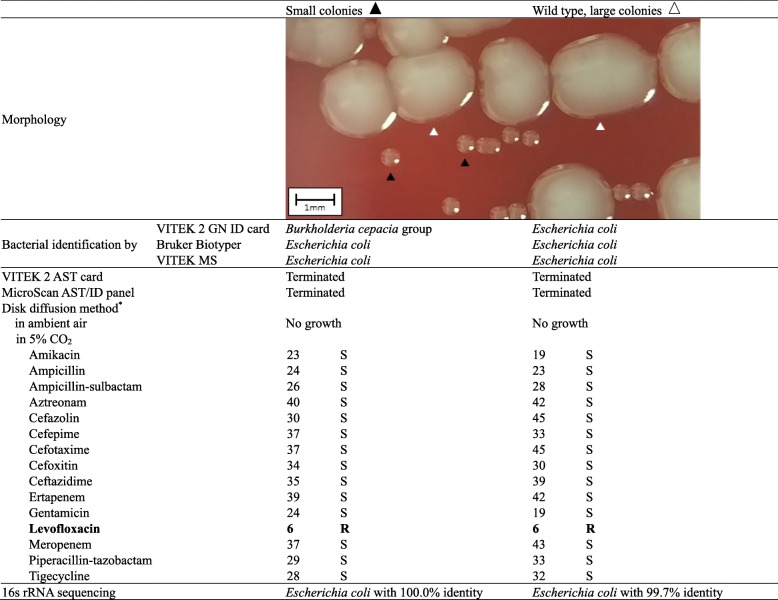

An 86-year-old woman visited our hospital with foamy urine and foul odor. Urinalysis showed many WBCs (163.7 WBCs/μL) and bacteria (11,343.7 bacteria/uL), and positivity for nitrite. Gram-negative coccobacilli were revealed upon microscopic examination. The sample was cultured on sheep blood agar plate (BAP) and MacConkey agar plates at 35 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. After one day of incubation, > 100,000 CFU/ml of pinpoint Gram-negative colonies grew on the BAP with 10,000 CFU/ml of Gram-positive cocci. After isolation of pinpoint colonies and another 24-h incubation, the pinpoint Gram-negative colonies were irregularly divided into large colonies and pinpoint SCV colonies on BAP (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing results

*Disk diffusion method results are given as measured zone diameters [8] and interpretive category. S susceptible, R resistant

While the VITEK 2 system (bioMerieux, Durham, USA) identified the pinpoint colony as Burkholderia cepacia group, the Bruker Biotyper (Bruker Daltonics, Leipzig, Germany) and VITEK MS (bioMerieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) systems identified both colonies as E. coli. The 16 s rRNA sequencing concluded both isolates were E. coli. As automated systems in an ambient air were unable to grow capnophilic SCVs, antimicrobial susceptibility testing profile was determined through disk diffusion method [4]. With the exception of levofloxacin resistance, bacteria was susceptible to all other antimicrobials. From these findings, we concluded that this isolate was CO2-dependent and had the ability to revert to its natural large form in the presence of CO2.

Whole genome sequencing analysis by the MiSeq® system (Illumina, San Diego, USA) was performed to inspect assumed genes that contained previously-reported causative mutations for the E. coli SCV phenotype (hemB, menC, and lipA gene) [1, 5], but no genetic mutational variations were observed between the two strains. The yadF gene was not present in either strain, which is consistent with previous reports about capnophilic E. coli strains [6].

Discussion

The first E. coli SCV was reported in 1931, but there have been only few reports from clinical specimens [7–9]. Interestingly, this SCV strain was also capnophilic. The bacterial growth for reported capnophilic E. coli strains formed either large colonies in the presence of CO2 or no colonies in the absence of CO2 [2, 3]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of E. coli with coexpressed SCV and capnophilic phenotype. Fortunately, this strain was susceptible to all other antimicrobials with the exception of levofloxacin, and therefore did not cause any severe outcome clinically. However, if this strain was to acquire drug resistance in the future, it is diagnostically crucial not to misidentify or neglect such strain for proper therapeutic purposes.

Additional criteria including CO2 conditions are needed because CLSI guidelines defining incubation conditions for Enterobacteriaceae involve 35 °C ambient air [4], which are unsuitable for growing capnophilic SCVs. We advise that all urine cultures should be incubated in an environment containing 5% CO2 to avoid overlooking of such strains. Proper identification using alternative methods such as MALDI-TOF MS systems are necessary for these capnophilic strains.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed.

Abbreviations

- BAP

Blood agar plate

- MALDI-TOF MS

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- SCV

Small colony variants

Authors’ contributions

The study was planned and designed by YP, NP, NAP, MK, RD, JB, HS, and DY. MK collected the samples. YP, JB, HS, and DY conducted the experiments. The interpretation of the genetic results was done by NP, NAP, and RD. The manuscript was prepared by YP and JB. All authors contributed to and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and conesnt to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea (#2018–1951-001).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yu Jin Park, Email: parkyj@yuhs.ac.

Nguyen Le Phuong, Email: luongphekidz07@gmail.com.

Naina Adren Pinto, Email: naina.pinto@gmail.com.

Mi Jeong Kwon, Email: mjkwon@yuhs.ac.

Roshan D’Souza, Email: roshanbernard@gmail.com.

Jung-Hyun Byun, Phone: +82-2-2228-2454, Email: jhbyun@yuhs.ac, Email: JHBYUN@yuhs.ac.

Heungsup Sung, Email: sung@amc.seoul.kr.

Dongeun Yong, Email: deyong@yuhs.ac.

References

- 1.Santos Victor, Hirshfield Irvin. The Physiological and Molecular Characterization of a Small Colony Variant of Escherichia coli and Its Phenotypic Rescue. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0157578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu Weiping, Chang Kai, Deng Shaoli, Li Min, Wang Junji, Xia Ji, Huang Hengliu, Chen Ming. Isolation of a capnophilic Escherichia coli strain from an empyemic patient. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2012;73(3):291–292. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tena Daniel, González-Praetorius Alejandro, Sáez-Nieto Juan Antonio, Valdezate Sylvia, Bisquert Julia. Urinary Tract Infection Caused by CapnophilicEscherichia coli. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2008;14(7):1163–1164. doi: 10.3201/eid1407.071053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . CLSI document M100: clinical and laboratory standards institute. 2018. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 28th edition ed. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tashiro Y, Eida H, Ishii S, Futamata H, Okabe S. Generation of small colony variants in biofilms by Escherichia coli harboring a conjugative F plasmid. Microbes Environ. 2017. 10.1264/jsme2.ME16121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Sahuquillo-Arce J.M., Chouman-Arcas R., Molina-Moreno J.M., Hernández-Cabezas A., Frasquet-Artés J., López-Hontangas J.L. Capnophilic Enterobacteriaceae. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2017;87(4):318–319. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roggenkamp A, Sing A, Hornef M, Brunner U, Autenrieth IB, Heesemann J. Chronic prosthetic hip infection caused by a small-colony variant of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(9):2530–2534. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2530-2534.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sendi P., Frei R., Maurer T. B., Trampuz A., Zimmerli W., Graber P. Escherichia coli Variants in Periprosthetic Joint Infection: Diagnostic Challenges with Sessile Bacteria and Sonication. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(5):1720–1725. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01562-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tappe D., Claus H., Kern J., Marzinzig A., Frosch M., Abele-Horn M. First case of febrile bacteremia due to a wild type and small-colony variant of Escherichia coli. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2006;25(1):31–34. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-0072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed.