Abstract

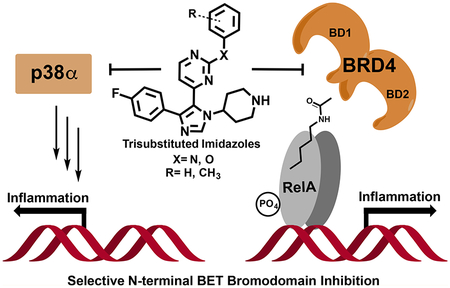

As regulators of transcription, epigenetic proteins that interpret post-translational modifications to N-terminal histone tails are essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis. When dysregulated, “reader” proteins become drivers of disease. In the case of bromodomains, which recognize N-ε-acetylated lysine, selective inhibition of individual bromodomain-and-extra-terminal (BET)-family bromodomains has proven challenging. We describe the >55-fold N-terminal-BET bromodomain selectivity of 1,4,5-trisubstitutedimidazole dual kinase−bromodomain inhibitors. Selectivity for the BRD4 N-terminal bromodomain (BRD4(1)) over its second bromodomain (BRD4(2)) arises from the displacement of ordered waters and the conformational flexibility of lysine-141 in BRD4(1). Cellular efficacy was demonstrated via reduction of c-Myc expression, inhibition of NF-κB signaling, and suppression of IL-8 production through potential synergistic inhibition of BRD4(1) and p38α. These dual inhibitors provide a new scaffold for domain-selective inhibition of BRD4, the aberrant function of which plays a key role in cancer and inflammatory signaling.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

How our genetic information is manipulated and ultimately expressed as a heritable phenotype is a central question in the field of epigenetics. N-terminal modifications on conserved histone proteins are key regulators of transcription.1,2 As such, proteins that interpret these complex modifications through molecular recognition are known to be essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, and when dysregulated, they become drivers of disease.3,4 Bromodomains are a subset of epigenetic “reader” or effector-domain-containing proteins, which function via binding to distinct lysine-acylation states, most commonly N-ε-acetylated lysines (Kac) on histones.5 This similar mode of molecular recognition for all 61 human bromodomains presents a significant hurdle for finding selective inhibitors as both therapeutic agents and chemical probes.6

One family of bromodomains with clinical relevance are the bromodomain-and-extra-terminal (BET) proteins BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and testis-specific BRDT, each of which contains a pair of bromodomains. Recent studies have shown the divergent roles of these domains for targeting both acetylated histones and acetylated transcription factors through the N- and C-terminal bromodomains (D1 and D2, respectively).7 Prominent roles of the BRD4 BET bromodo-mains include regulation of c-Myc expression at super-enhancers8 and enhancement of NF-κB-mediated transcription through interactions with acetylated K310 of the κB RelA subunit.7

Because of the biological significance of bromodomain functions in cellular proliferation and inflammatory pathways, over 20 clinical trials are underway for studying the effects of BET-family inhibition as anticancer and anti-inflammatory therapies. Because of the high sequence identity among BET proteins, most reported inhibitors act as pan-inhibitors of BET bromodomains, such as (+)-JQ1 (1, Figure 1), and do not discern the functions of individual bromodomains.9 Ouyang et al. reported FL-411 (2, Figure 1), which is an exception to the norm in being selective for BRD4 over other BET proteins.10 Nevertheless, the potential off-target effects, dose-limiting thrombocytopenia, and concerns over latent-viral reactivation associated with pan-BET inhibition highlight the need for novel scaffolds with improved selectivity and potency.11–13

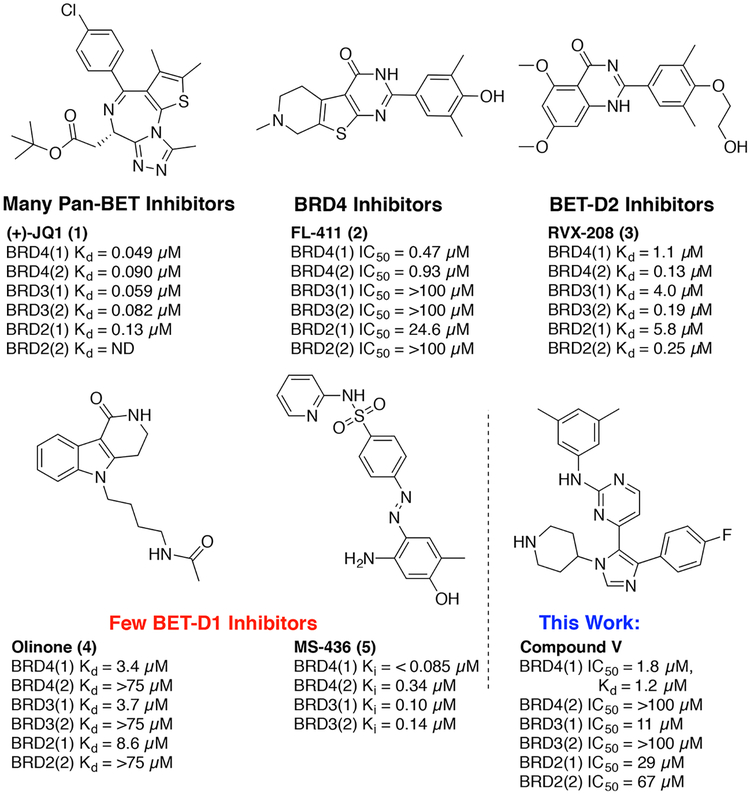

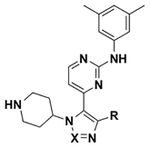

Figure 1.

Reported BET bromodomain inhibitors and a new 1,4,5-trisubstituted imidazole, V.

In lieu of isoform-specific inhibitors, domain selectivity among the BET family of proteins has been explored. D2-selective molecules RVX-208 (3, Figure 1) and RVX-297 have allowed the study of D2-dependent processes, but they have reduced efficacy mitigating BET-related transcription in comparison with that of pan-BET inhibition.14,15 Alternatively, specific deletion of only BRDT(1) in mice was sufficient to impair spermatogenesis.16 In the case of BRD4, fluorescence-recovery-after-photobleaching experiments identified similar levels of BRD4 displacement from chromatin between a D1-defective mutant and (+)-JQ1 (1)-treated cells, whereas chromatin binding by a D2-defective mutant was less affected.17 In relation to NF-κB signaling, interactions of BRD4(1) are likely more relevant for targeting transcriptional activity.18 Although Olinone and MS-436 (4 and 5, Figure 1) have been reported to possess some level of D1 selectivity,19–21 BET bromodomain research continues to be dominated by pan-BET inhibitors. Despite being potent BRD4(1) inhibitors, 5 and structural analogue MS-611 are not selective for D1 over D2 in other BET proteins. In contrast, D1-selective molecule 4 is a modest inhibitor of BRD4(1) (Kd = 3.4 μM) but represents the highest level of selectivity. Alternative chemical-biology strategies like the “bump-and-hole” approach22,23 have considerably advanced our understanding of individual BET bromodomain and protein function. However, improved D1-selective inhibitors are still required to further dissect the relevant interactions of BRD4 with chromatin and acetylated transcription factors. The development of such small molecules may have significant implications for studying the roles of relevant BET proteins in transcription and the treatment of disease.

In this report, we describe dual kinase−bromodomain inhibitors with the strongest affinity for BRD4(1) among BET bromodomains. Although other BET bromodomain inhibitors have been reported in the literature, a notable feature of this molecule is its selectivity for the first bromodomains of BET proteins with simultaneous kinase-inhibitory activity against mitogen-activated-protein (MAP) kinase p38α. The atomic-level insights from structural analysis and structure−activity relationships will inform the future development of BET-D1-selective inhibitors, and optimization of this dual inhibitor should afford a useful tool compound to test synergistic effects in treating inflammation and cancer.

RESULTS

The 1,4,5-trisubstituted imidazole, SB-284851-BT (I), and related analogues are known p38α inhibitors and were recently discovered to bind to BET bromodomains in three separate reports using diverse libraries, including the published kinase-inhibitor-set library from GlaxoSmithKline.24–26 Our study tested for BET bromodomain selectivity by using a 19F NMR assay, which simultaneously assessed binding to BRD4(1) and the bromodomain of BPTF.26 I was selective for BRD4(1) over BPTF in the assay and was further validated as a ligand in a thermal-stability assay, through differential-scanning fluorimetry (DSF), and in a fluorescence-anisotropy (FA) assay, displacing fluorescently labeled pan-BET ligand BI-6727, referred to here as BI-BODIPY. Although our previous study identified selectivity for the BET family, we did not further evaluate selectivity within the BET family of bromodomains.

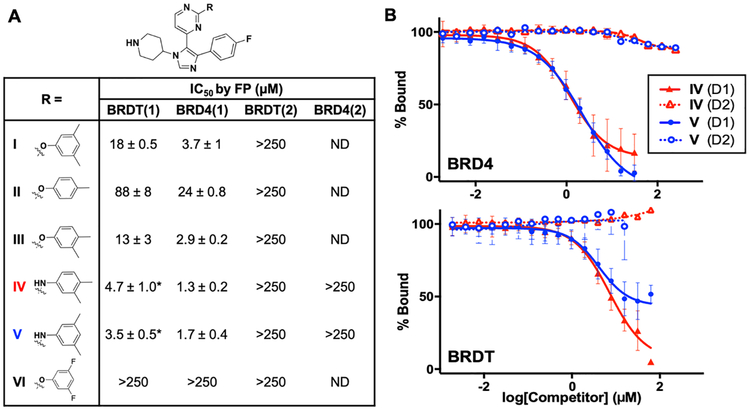

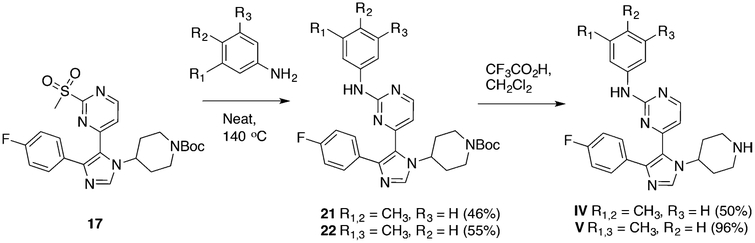

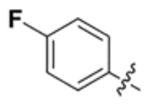

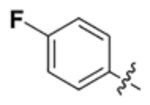

We first turned our attention to two BET bromodomains, BRDT(1) and BRD4(1). On the basis of significant differences in affinity arising from methyl-substitution patterns on the phenyl ring of I for BRD4(1),26 we synthesized several new analogues and determined their affinities to these two domains. The synthesis for I has already been established,27 and we took advantage of a late-stage intermediate (Scheme 1) for analogue synthesis using a nucleophilic aromatic-substitution reaction with various phenolic and anilinic derivatives (Schemes 2–4), of which several are described here (Figure 2A). Using FA to quantify the activities of these newly synthesized compounds against both BRDT(1) and BRD4(1), we found that compound I binds to both domains. The observed affinity for BRD4(1) was 3-fold weaker than the previously reported data of the compound used directly from the library stock, indicating a possible discrepancy in concentration or purity. Consistent with our prior report,26 the para-substituted analogue, II, bound substantially more weakly. However, a 3,4-dimethyl-substituted analogue with an O-substituted pyrimidine, compound III, bound with increased affinity (IC50 = 2.9 ± 0.2 μM). Finally, when the pyrimidine oxygen was changed to a nitrogen, we observed an increase in potency, with IC50 values of 1.3 ± 0.2 and 1.7 ± 0.4 μM for the 3,4- and 3,5-dimethyl analogues, compounds IV and V, respectively, against BRD4(1). Molecule VI, with a 3,5-difluoro-substituted aromatic ring (Scheme 4) versus methyl groups did not interact with high affinity (IC50 > 250 μM), supporting the need for an electron-rich ring. A direct-binding titration of compounds IV and V by isothermal-titration calorimetry (ITC) determined entropically favorable binding events, leading to Kd values of 1.8 and 1.2 μM, respectively (Figure S7).

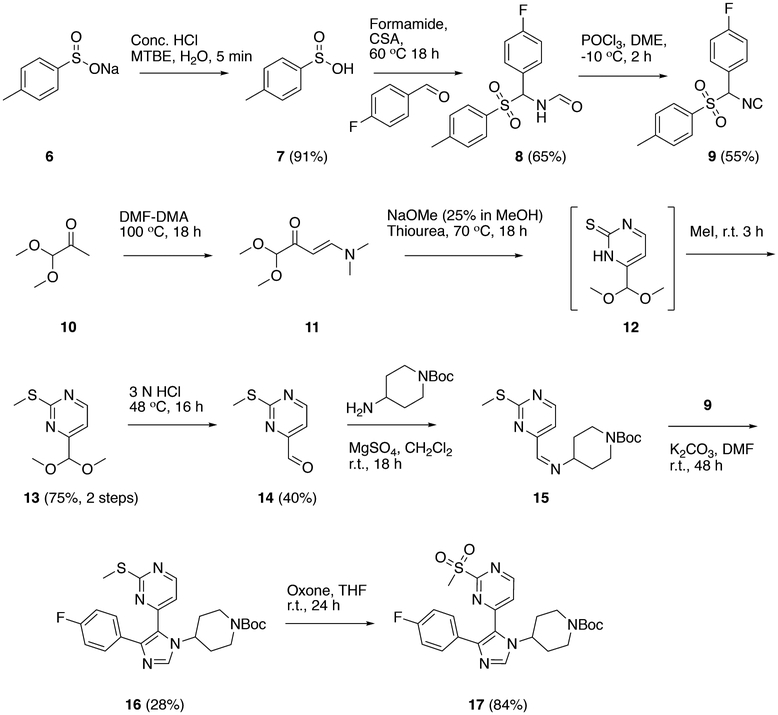

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Common Intermediate 17a

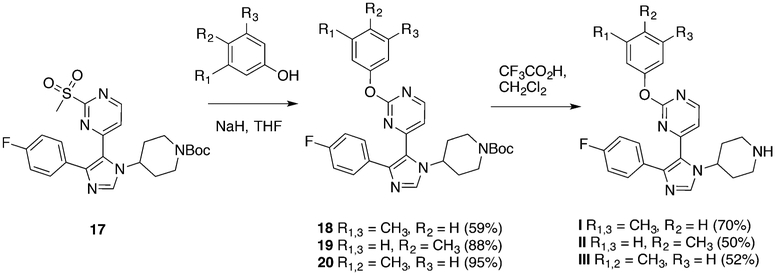

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Compounds I, II, and III

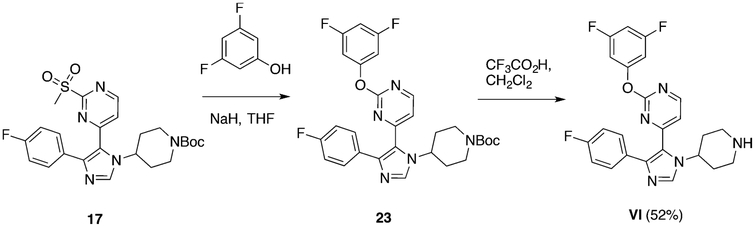

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of Compound VI

Figure 2.

Competitive-inhibition experiments via fluorescence anisotropy of SB-284851-BT (I) and analogues against BET bromodomains indicating selectivity for BET D1s. (A) IC50 values of analogues (means ± SEM) determined by competitive-fluorescence-anisotropy assays. Asterisks (*) indicate incomplete inhibition observed; ND indicates not determined. (B) Competition-binding isotherms of compounds IV and V against the first and second bromodomains of BRD4 and BRDT.

To evaluate if these molecules would function as pan-BET inhibitors on the basis of binding to both BRDT(1) and BRD4(1), we next tested D1 versus D2 selectivity, as our fluorescent tracer binds to D2s of BRDT and BRD4 with high affinity (Kd = 270 and 183 nM). Surprisingly, in all cases, the analogues tested were unable to fully displace BI-BODIPY from either D2 construct (Figure 2B). Alternatively, pan-BET inhibitor BI253628 displaced the fluorescent tracer from the domains of both BRDT and BRD4. A D2-selective inhibitor, RVX-208, was tested in a similar fashion and validated the experimental outcomes seen with our protein constructs (Figures S2 and S3). Additionally, a dual bromodomain construct of BRD4 was tested in our FA assay, and only partial displacement was observed with compound V, consistent with it only fully displacing BI-BODIPY from the first bromodo-main (Figure S4). Molecules I−III also maintained their selectivity for D1 over D2 when tested against BRDT(2), indicating that neither the substitution pattern on the aromatic ring nor the O to N substitution on the pyrimidine ring was responsible for the observed selectivity.

The observed preference toward BRD4(1) led us to evaluate selectivity against the two other BET proteins, BRD2 and BRD3, using an orthogonal assay. Compound V was assayed commercially against seven of the eight BET bromodomains in an ALPHAScreen format.29 Although BRDT(2) was not available for testing by ALPHAScreen, D1 over D2 selectivity was maintained for compound V (Table 1 and Figure S8). Additionally, compound V displayed 6- and 16-fold selectivity for BRD4 over ubiquitously expressed BET proteins BRD2 and BRD3, respectively (Figure S8). Together, these results support a valuable scaffold for developing D1-selective inhibitors of BET bromodomains, albeit with the highest affinity for BRD4(1) and BRDT(1).

Table 1.

ALPHAScreen Analysis of Compounds V, VII, VIII, and IX against 7 of 8 BET Bromodomains

|

R | X | IC50 by ALPHAScreen (μM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRD4 | BRD3 | BRD2 | BRDT | ||||||

| D1 | D2 | D1 | D2 | D1 | D2 | D1 | |||

| V |  |

C | 1.8 | >100 | 11.2 | >100 | 29 | 67 | 5.3 |

| VII |  |

N | 27 | 75 | 51 | 110 | 43 | 30 | 36 |

| VIII |  |

N | 160 | 102 | 200 | 310 | >250 | 260 | 110 |

| IX |  |

N | 1.3 | 0.56 | 0.77 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 12 | 1.6 |

Structural Analysis of Binding.

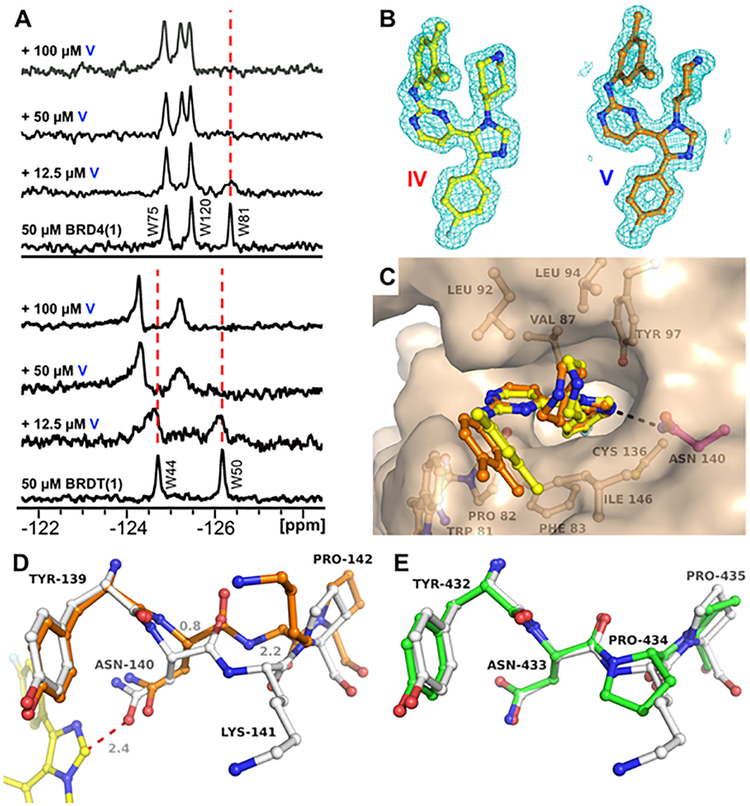

Because of the paucity of D1-selective inhibitors and the generality of these results within the trisubstituted-imidazole scaffold, we sought to structurally characterize their interactions. Protein-observed fluorine NMR (PrOF NMR) is an emerging method for ligand discovery that has been used to characterize the binding interfaces of small molecules with bromodomains30 as well as to quantify the affinities of weakly binding molecules via chemical-shift-perturbation experiments over a range of ligand concentrations.31 PrOF NMR was used to characterize the binding interactions of compound V with both BRD4(1) and BRDT(1) (Figure 3A) and to further test selectivity against additional bromodomains at higher small-molecule concentrations than were tolerated in earlier experiments. Our focus in these experiments was primarily on the WPF-shelf tryptophan residue adjacent to the Kac-binding site, W81 for BRD4(1) and W50 for BRDT(1), to see if an unusual effect on resonance perturbation was observed relative to those of our prior reports.26 With both BRD4(1) and BRDT(1) and using compound V, an intermediate to slow exchange perturbation of the WPF-shelf resonance was observed, which reached the fully bound state at approximately 1 equiv. of small molecule. Such NMR behavior is indicative of a residence time on the protein that is sufficiently long on the NMR time scale to partially resolve both the bound and unbound states and is consistent with the binding site and single-digit-micromolar-Kd affinities exhibited by compounds IV and V for these domains.32 W44 of BRDT(1) is outside the binding site and was also minimally perturbed, indicating a conformational change of the protein. However, these data did not support binding to a new binding site and were similar to observations in our prior reports.26 We further tested non-BET bromodomains of BPTF and a yeast GCN5-like malarial protein that also contains a WPF-shelf. In these cases, we did not detect binding to either protein, consistent with selectivity for the BET family of bromodomains (Figure S9).

Figure 3.

Confirmation of compound V binding BRD4(1) and BRDT(1) and possible structural basis for the D1 over D2 selectivity of the inhibitors. (A) PrOF NMR titrations with bromodomains of BRD4 and BRDT. Samples contain 50 μM 19F-labeled BRD4(1) or BRDT(1) with increasing concentrations of ligand V. (B) Electron-density maps of ligands (2Fo − Fc, 1σ) from X-ray structures of BRD4(1) liganded with IV (yellow, 1.74 Å, PDB ID 6MH7) and V (orange, 1.60 Å, PDB ID 6MH1). (C) Superposition of compounds IV and V in the Kac site of BRD4(1) revealing subtle conformational changes of the dimethylphenyl moieties nested in the WPF shelf. (D) Unliganded state of BRD4(1) (gray, PDB ID 4IOR), with the Kac site around Asn140 in a relaxed state, and BRD4(1) bound to inhibitor V (yellow ligand and orange structure), with Asn140 giving way (Δ = 0.8 Å) as a result of steric hindrance with the imidazole moiety of the inhibitor (red dotted line) and positioning itself for optimal H-bonding interaction. As a result, the adjacent Lys141 undergoes a large conformational change (Δ = 2.2 Å). (E) Unliganded BRD4(2) (green, PDB ID 2OUO), with the region around Asn433 being highly similar to that of BRD4(1) (gray) except for the presence of Pro434 instead of lysine. The geometric constraints of the Asn−Pro−Pro sequence in BRD4(2) likely renders the peptide more rigid and less compatible with the inhibitor-induced conformational changes observed in BRD4(1).

We turned to X-ray crystallography to obtain higher-resolution structural information to understand the mode of molecular recognition and to rationalize the domain selectivity. Trisubstituted imidazoles SB-251527 and SB-284847-BT have previously been crystallized with BRD4(1) (PDB IDs 4O7F and 4O7B, respectively).25 In addition, we crystallized compounds IV and V, with BRD4(1) (Figure 3C). All four compounds engage the protein in a similar fashion, with the imidazole making direct hydrogen-bonding interactions with N140, which is displaced by 0.8 Å relative to the apo structure, along with a displacement of the Cα of the adjacent K141 by 2.2 Å (Figures 3D,E and S11). However, unlike pan-BET inhibitors, these molecules failed to hydrogen bond to Y97 via a bridging-structured water. The O−N substitution pattern did alter the orientation of the aromatic ring slightly, which may favor edge-to-face π−π interactions with W81 of BRD4(1) in a lipophilic region adjacent to the WPF shelf (Figure S12), impacting affinity but not selectivity. The methyl groups were necessary for binding affinity, as a 3,5-difluoro-substituted analogue, VI, only bound weakly to both bromodomains of BRD4. Overlay of a BRD4(2) crystal structure shows potential steric incompatibilities at multiple regions of the small molecule, including a steric clash of the C2 imidazole portions of the rings of compounds IV and V with N433 in the binding site, which may not be as conformationally flexible as the BRD4(1) N140 because of the adjacent P434. These incompatibilities may preclude a high-affinity interaction with BRD4(2); however, such a steric effect could not be directly proven from our structures. Together, 19F NMR and X-ray structural analysis could be used to rationalize binding interactions but were not sufficient to describe selectivity.

As an alternative possibility for selectivity, we considered the sequence similarity between BET D1 and D2. Of the three nonconserved amino acids between the binding sites, we hypothesized the proximity of the piperdyl group to D144 in our crystal structures was potentially responsible for the observed selectivity trends. This BET-D1-conserved aspartic acid is replaced by a histidine (H437 of BRD4) in BET D2s. At physiological pH, H437 will be weakly protonated and may result in potential electrostatic repulsions in addition to steric effects that prevent binding to D2. To determine whether the origins of D1 versus D2 selectivity are due to H437 in D2, we expressed a H437D-mutant BRD4(2) construct to restore binding of compound V. For this experiment, we used a new fluorescent tracer for the FA assay based on a fluorescein-labeled (+)-JQ1 molecule. (+)-JQ1 bound to H437D BRD4(2) with comparable affinity to the WT D2 protein in direct-binding assays (Figure S5; Kd BRD4(2) = 120 nM, H437D BRD4(2) = 200 nM) and with a slightly attenuated IC50 in competition assays (IC50 BRD4(2) = 490 nM, H437D BRD4(2) = 590 nM). Binding of V to H437D BRD4(2), however, was not observed (Figure S6), suggesting the observed selectivity trends are not entirely attributable to H437 of BRD4(2).

Displacement of Structured Waters.

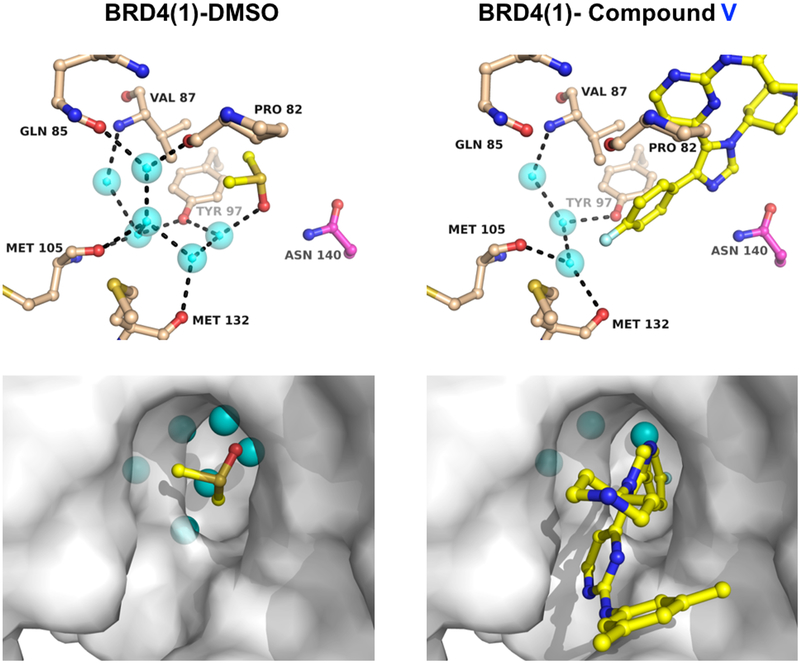

Recent computational studies suggested a second possible explanation for the observed selectivity on the basis of differential affinities for the four structured waters within the BET bromodomain binding sites. In these reports, the stabilities of bromodomain water networks have identified the water molecules most likely to be displaced in BRD4(1) and BRDT(1) among the other BET bromodomains,33,34 whose water molecules are more tightly bound to the protein. Such an effect would also explain the observed selectivity of compound V for BRD4(1) and BRDT(1) over the other BETs measured in the ALPHAScreen assay. We compared the cocrystal structures of compound V with BRD4(1) and of a DMSO molecule bound to the same protein (Figure 4). Whereas in the DMSO costructure, six water molecules are present, including the four conserved structured waters, three water molecules are displaced in the cocrystal structure with compound V, and the water network is reorganized by the fluorophenyl group of compound V. Similar displacements were observed in the cocrystal structure with compound IV (not shown). Displacement of water in the binding site is also consistent with the positive entropy of binding in ITC experiments with compounds IV and V (5.0 and 4.2 cal/mol/°C, respectively). Importantly, these modes of binding and selectivity are not observed in BET-D1-selective molecules 4 (olinone) and 5 (MS-436); however, a remarkably similar binding mode has been observed with a selective TRIM24-bromodomain inhibitor.35 These results may in part give rise to our observed selectivity, but the generality of such a finding will be useful to study in future investigations.

Figure 4.

Displacement of structured waters from BRD4(1). Crystal structure of BRD4(1) with DMSO (left, yellow, PDB ID 4IOR) and compound V (right, yellow, PDB ID 6MH1), with structurally conserved water molecules shown in cyan.

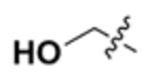

To further evaluate the displacement of structured waters by the fluorophenyl group and additional effects around the imidazole ring, which removes steric effects from a C−H at position C2, we synthesized three new molecules (VII, VIII, and XI) based on a 1,4,5-trisubsititued triazole scaffold (Scheme 5). These molecules either maintain the fluorophenyl group for a direct comparison with V or replace this phenyl group with a smaller hydroxymethyl or methyl group to maintain the structured waters. According to PrOF NMR, compound VII bound BRD4(1) in a manner similar to that of compound V (Figure S10), but because of solubility challenges at high concentrations and the low sensitivity of FA, ALPHAScreen was used to test for BET selectivity. Replacement of the imidazole ring with a triazole in compound VII resulted in a moderate loss of potency to BRD4(1) (IC50 = 1.8 μM for V vs 27 μM for VII), likely because of the weakened hydrogen bonding with the conserved N140 of BRD4, and a significant loss of selectivity (27 μM for D1 vs 75 μM for D2). Replacement of the fluorophenyl group with a hydroxymethyl group (VIII) resulted in further reduced binding (IC50 > 100 μM), possibly because of the hydrophobic nature of the binding pocket. Finally, in contrast, truncation of the fluorophenyl group to a methyl in compound IX enhanced binding 20-fold relative to that of VII (IC50 = 1.3 μM for IX vs 27 μM for VII). The large gain in potency indicates an energetic penalty must be overcome for displacing the structured waters with a large aromatic group. In the case of compound IX, which lacks a large aromatic group displacing structured waters, an inversion of BRD4-domain selectivity favoring BRD4(2) (IC50 = 0.56 μM) and overall pan-BET inhibition were observed.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of Triazoles VII, VIII, and IXa

aReagents and conditions: (a) 100 °C, 3 h for the synthesis of 34 and 36; (b) NaHMDS, −78 °C, 0.5 h for the synthesis of 35.

From these data, we conclude that D1 over D2 selectivity cannot be attributed to the methyl-substitution pattern of the pyrimidine-substituted aromatic ring, the phenoxy-pyrimidine to anilino-pyrimidine substitution, or even steric incompatibilities with the piperdyl group. Rather, the observed selectivity is due to a combination of effects including the imidazole ring itself and from the fluorophenyl ring displacing structured waters.

Bromodomain and Kinase-Selectivity Profiling.

To more broadly test the bromodomain selectivity of compound V, we used a commercial-assay platform to characterize the activity against 32 of the 61 bromodomains provided by DiscoverX. On the basis of a measured Kd of 1.2 μM, we tested the selectivity of V at 10 μM (approximately 10-fold above the Kd). Consistent with our FA and ALPHAScreen results, the two most significant interactions with V of the eight BET bromodomains were those of BRD4(1) and BRDT(1), with 86 and 50% inhibition at that concentration, respectively (Table S3). The BET D2s were the most unaffected (7−27% inhibition) relative to D1s. Overall, only bromodomains SMARCA2, PCAF, p300, and SMARCA4 had inhibitory activity between 40 and 50%. These results demonstrate the selectivity of compound V toward BET D1s and, given the modular synthesis of the 1,4,5-trisubstituted-imidazole scaffold, represent a useful starting point for domain-selective-inhibitor development.

As compound I is a reported MAP-kinase inhibitor, we were interested in verifying the selectivity of these analogues against other kinases. Similar analogues of I, either maintaining pyrimidyl-aniline substitutions but lacking dimethyl groups or containing methylated piperidinyl groups, have been previously reported and are highly potent and selective for p38α and β at 100 nM.36 As such, we expected a similar affinity for p38α and a similar kinase-selectivity profile. Indeed, the Kd of analogue V against p38α was determined to be 0.47 nM (Figure S13). Because of the weaker D1 potency, we tested for selectivity among kinases at a concentration of 1 μM using the DiscoverX platform. In this case, we measured high inhibitory activity against p38α and β (Table S4). However, additional kinases were inhibited at this concentration, giving a selectivity score, S(1), of 0.037, similar to that of the p38α chemical probe SB203580 (0.024 at 100 nM). Because of the available crystal-structure data of related compounds bound to p38α and the wealth of data available on this inhibitor class, kinase selectivity may be further improved and potentially even abolished through rational design.

Cellular Evaluation of Lead Compounds.

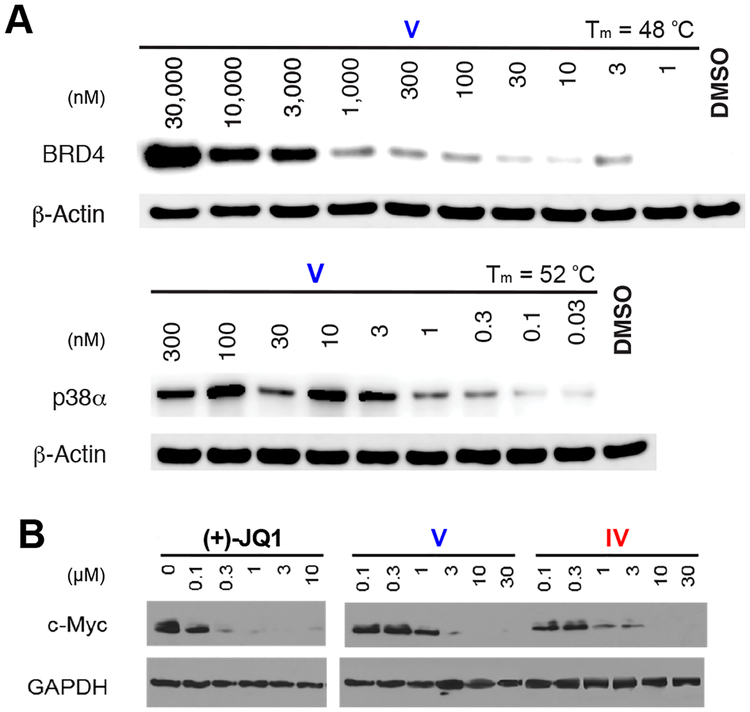

Given the BET-D1 selectivity exhibited by compounds IV and V, we proceeded by testing these molecules in cells. First, we verified target engagement in the native chemical environment by using a cellular thermal-shift assay (CETSA) in A549 cells, where the thermal stability of the target protein is altered upon binding to small molecules.37 Here, an isothermal-denaturation experiment indicated compound V stabilized BRD4 and p38α in a dose-dependent manner at concentrations above 3 μM and 1 nM, respectively. Protein-melt temperatures correlated well with previous CETSA experiments performed on BRD4 and p38α.38,39 Importantly, as this experiment does not measure cellular outcomes downstream of target inhibition, these results confirm unambiguously that compound V enters cells and maintains interactions with BRD4 and p38α in a cellular context (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Cellular evaluation of lead compounds confirming target engagement. (A) Cellular thermal-shift assay with compound V indicating thermal stabilization of BRD4 and p38α in A549 cells, with β-actin used as a loading control. (B) Western blots of expressed c-Myc levels in MM.1S cells, with GAPDH used as a loading control.

After verifying protein-target engagement, we proceeded to test the efficacy of our D1-selective inhibitors in MM.1S cells by measuring reduction of c-Myc, an oncogene highly sensitive to BET inhibition, in several leukemia cell lines. Similar to (+)-JQ1, used as a positive control, compounds IV and V inhibited expression of the c-Myc oncoprotein in MM.1S cells at concentrations approaching their respective BRD4(1) Kd values, as determined by Western blot (Figure 4B). These results also mirrored cell-viability data in the cell line studied (Figure S14). Together, these are characteristic hallmarks of BET inhibitors, and suggest effective cellular bromodomain-inhibitory activity. To verify inhibition of the p38α kinase, we determined the phosphorylation states of its downstream phosphorylation target, MSK1. Here we observed a decrease in levels of MSK1 phosphorylation at T581 upon treatment with compounds IV and V, although at levels significantly higher than their affinity for p38α. This effect was not observed with (+)-JQ1 treatment (Figure S16). Together, these results are consistent with BET-D1 inhibition using our 1,4,5-trisubstituted-imidazole scaffold being sufficient to regulate transcription in cells in a BRD4-specific manner.

Inhibition of Inflammation.

The role BRD4 plays in coupling NF-κB signaling to gene transcription via Kac recognition has been disputed. In certain systems, transcriptional activation of RelA-target genes has been observed independent of BRD4,40 whereas Chen and co-workers have reported on BRD4 maintaining activity of NF-κB signaling via recognition of K310 acetylation at the RelA subunit.18 In the case of NF-κB-dependent activity, it remains unclear whether D1 or D2 plays the dominant role in driving transcription; the two bromodomains of BRD4 maintain interactions with chromatin, and the presence of both domains enhances transcription.7 In contrast, whereas Zou and co-workers showed a 10-fold stronger interaction of RelA with D2 by a fluorescence-competition assay,18 Jung et al. did not detect any binding interactions in a TR-FRET assay,41 leading to uncertainty of a direct interaction between RelA and BRD4. Together, these data highlight a need for confirmation of the relevant interactions of each bromodomain of BRD4.

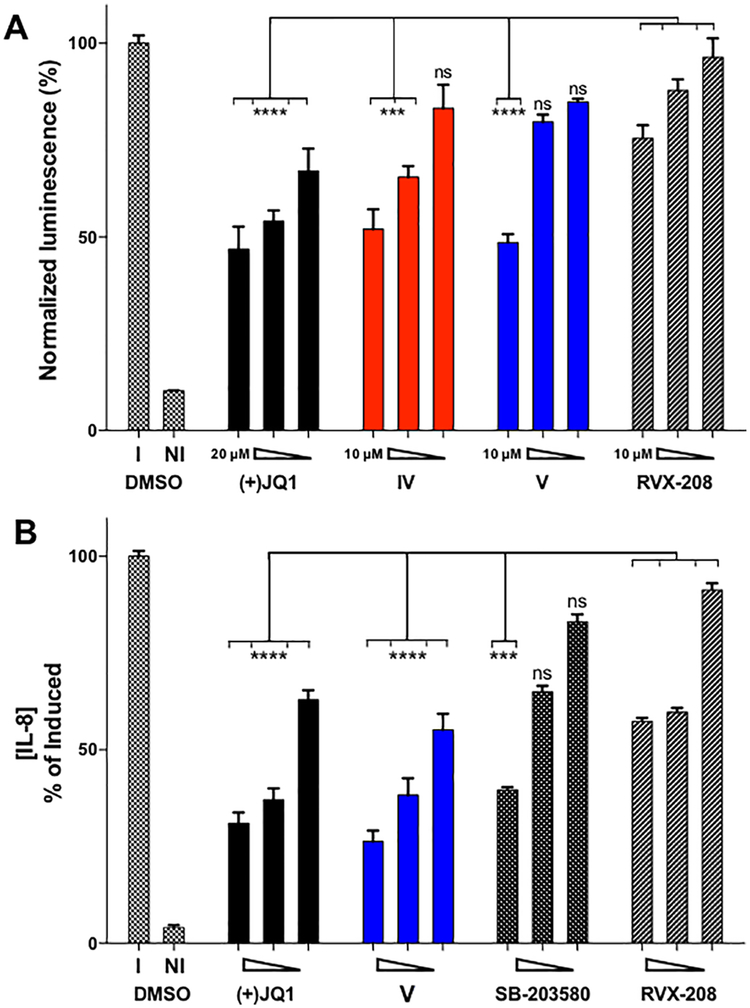

To further assess cellular efficacy of our D1-selective inhibitors, we employed a luminescence-based NF-κB reporter assay in A549-NF-κB-luc cells. Compound V (51% inhibition at 10 μM) produced the most effective knockdown of TNFα-induced transcription in this assay, compared to inhibition of BRD4(2) using RVX-208 (25% inhibition at 10 μM, Figure 6A). As other p38 MAPK inhibitors (SB-203580 and VX-702) showed limited inhibitory effects in this assay (Figure S17), and compounds IV and V exhibited minimal cytotoxicity toward A549 cells up to concentrations of 25 and 10 μM, respectively (Figure S14), these experiments suggest BRD4(1) inhibition may be crucial to NF-κB signaling in A549 cells and support earlier results using BET-selective inhibitor MS-611.21

Figure 6.

Inhibition of NF-κB signaling and an NF-κB target gene. (A) NF-κB−luciferase-reporter assay with A549 cells with 20, 5, and 1 μM (+)-JQ1 and 10, 5, and 1 μM IV, V, and RVX-208. (B) Sandwich IL-8 ELISA with 10, 1, and 0.1 μM (+)-JQ1, V, SB-203580, and RVX-208. Data reported are means ± SEM values (n = 3 biological replicates) normalized to compound-induced (I) control values. All samples except the not-induced (NI) control were induced with 10 ng/mL TNFα. ANOVA comparisons to the three RVX-208 treatments; ns, not statistically significant; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. See Figure S3 for compound-mediated-cellular-cytotoxicity data.

Inhibition of BET bromodomains has been shown to decrease production of cytokines; however, the roles of individual BET bromodomains are also yet to be deconvoluted. To assess the effect of compound V on inflammation at the protein level, we quantitated the suppression of cytokine production using an immunosorbent assay (ELISA). We chose to measure the concentrations of secreted cytokine IL-8, because its role as an inflammatory stimulus for neutrophil recruitment has been well characterized.42 At concentrations of 1 μM in this assay, BRD4(1) inhibition using compound V reduced levels of cytokine production (62% inhibition at 1 μM) more effectively than BRD4(2) inhibition by RVX-208 (40% inhibition at 1 μM). Moreover, the effects of compound V were comparable to those of pan-BET inhibition by (+)-JQ1 (63% inhibition at 1 μM, Figure 6B). This increased potency of V is likely due to the additional inhibition of p38α. However, other off-targets cannot be ruled out at this point. Interestingly, complete inhibition of cytokine production was not observed with any of these molecules, whereas an irreversible NF-κB inhibitor, parthenolide, decreased IL-8 production to baseline at 20 μM.43 These results, coupled with confirmation of target occupancy by CETSA, establish a potential mode of synergy via dual targeting of p38α and BET bromodomains.

DISCUSSION

Through a late-stage structure−activity-relationship (SAR) investigation of 1,4,5-trisubstituted imidazoles, we identified a small series of BET inhibitors. Biophysical characterization of lead compounds against the entire BET family revealed an unexpected but high selectivity toward BET D1s over D2s, with the highest affinity for BRD4(1). Our experimental data ruled out selectivity toward N-terminal BET bromodomains because of steric hindrance by a histidine present in C-terminal BET bromodomains, where the corresponding position is occupied by aspartic acid in BET D1s (D144 in the case of BRD4). Although H437 appears within 3 Å of the piperidyl group in overlays of BRD4(2) crystal structures (e.g., PDB ID 2YEM), this amino acid adopts alternate conformations that may accommodate the ligand (e.g., PDB ID 5UEU).

Rather, our data with compounds VII to IX indicate selectivity was largely due to the fluorophenyl moiety and the imidazole ring itself. Structural analysis indicates a binding mode of suitably substituted imidazole rings similar to that of acetyl groups on acetylated histones, with hydrogen bonding to a conserved asparagine residue (N140 in the case of BRD4(1)) by the imidazole-ring nitrogen, although N140 and K141 are slightly displaced to accommodate the imidazole ring. Additionally, the fluorophenyl group sits much deeper in the binding pocket than those of previously reported BET inhibitors and is able to displace three water molecules present in the cocrystal structure of BRD4(1) with DMSO, in which one of these is a structurally conserved water. Our data and previous computational studies on the stability of bromodomain water networks33,34 lead us to believe our observed selectivity profile also arises in part from the displacement of a conserved water from BRD4(1) and BRDT(1) but not from other BET bromodomains.

Cellular data indicate our compounds are highly cell-permeable and capable of engaging BRD4 in various cell lines. However, whereas effects on the MM.1S cell line appear to be largely BRD4-driven because of the c-Myc sensitivity of this cell line, the A549 lung-cancer cell line appears to be increasingly sensitive to both p38α and BRD4 inhibition, on the basis of decreases in cytokine secretion upon treatment with our molecules. Although such cooperative effects can only be cautiously assigned because of additional off-target kinase engagement, our preliminary evaluations suggest selective inhibition of BRD4(1) may be more efficacious than BRD4(2) inhibition. These cellular data confirm previous chromatin-binding studies and work targeting inhibition of BET bromodomains in inflammation;44,45 however, bromodomain inhibition alone failed to completely inhibit signaling pathways in the system studied here.

Although kinase activity was secondary to our aim of developing selective BET inhibitors, we endeavored to fully characterize the kinase activity of our lead molecules. Previous reports on substituted imidazoles and pyrazoles of the “DFG-out” class of hinge-binding kinase inhibitors suggest that modest additions to the periphery of the scaffold, such as through N-alkylation, may improve selectivity.46,47 Additionally, by replacing the p-fluorophenyl moiety from similar trisubstituted imidazoles with ethyl or chloro groups, Gallagher et al. observed a loss of p38α-kinase inhibition.48 We thus envision the selectivity profile of these molecules may be readily improved by further analogue synthesis and SAR studies.

CONCLUSION

Through a systematic investigation of a recently characterized 1,4,5-substituted-imidazole scaffold and a newly reported 1,4,5- substituted-triazole scaffold, we have described a new BET-inhibitor class with high selectivity for D1 over D2 of BRD4 and BRDT. From a therapeutic standpoint, this class of 1,4,5-trisubstituted imidazoles and triazoles may be a valuable starting point for dual kinase−bromodomain inhibition, as simultaneous BRD4 and MAP−PI3-kinase inhibition has recently been suggested for synergistic treatment of colon cancer, avoiding the development of resistance to BET- or kinase-inhibitor monotherapy28,49 and resulting in decreased toxicity relative to a cocktail of (+)-JQ1 and PI3K inhibitors.50 As demonstrated here, the optimization of further inhibitors of individual BET D1s may enable selective control of BRD4-associated inflammatory signaling. Finally, the displacement of structured waters may also be a general strategy that can be applied to other known pan-BET inhibitors, which we are actively investigating.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Synthetic Methods.

All chemical reagents were purchased from commercial vendors and used without further purification. Flash chromatography of compounds was performed on a Teledyne-Isco Rf-plus CombiFlash instrument across RediSep Rf columns. 1H (400 MHz) and 13C (125 MHz) NMR spectra were recorded in chloroform-d or methanol-d4 and chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million (ppm). All coupling constants (J) are reported in hertz (Hz), with s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; and m, multiplet. Purities of final compounds diluted in DMSO were determined by reverse-phase-high-performance-liquid-chromatography (HPLC) analysis using an Agilent 1200 Series HPLC (215 and 254 nm DAD detector; Agilent Zorbax SBC18 column, 4.6 × 150 mm, 5.0 μm; mobile phase gradient of 90:10 to 15:85 0.1% TFA in H2O/acetonitrile over 22 min; flow rate of 1.0 mL/min), and all compounds used were verified to be >95% pure by peak area. High-resolution mass spectrometry was performed using positive-mode-electrospray-ionization methods (ESI-MS) with a Bruker BioTOF II spectrometer.

Synthesis of Common Intermediate 12. Synthesis of 4-Methylbenzenesulfinic Acid (7).

To a suspended solution of p-toluenesulfinic acid sodium salt, 6 (3.0 g, 16 mmol), in water (10.0 mL) was added methyl tert-butylether (5.0 mL) followed by dropwise addition of concd HCl (1.5 mL). After the reaction was stirred for 5 min, the organic phase was separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted with methyl tert-butylether (2 × 25 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure. The solid obtained was resuspended in hexanes (50 mL), filtered, and dried to give the desired compound, 7, as a white solid (2.4 g, 91%).

Synthesis of N-((4-Fluorophenyl)(tosyl)methyl)formamide (8).

A mixture of 4-methylbenzenesulfinic acid, 7 (0.50 g, 3.2 mmol); 4-fluorobenzaldehyde (0.58 g, 4.7 mmol); formamide (0.52 g, 12 mmol); and camphorsulfonic acid (0.09 g, 0.4 mmol) was stirred at 60 °C for 18 h. The resulting solid was stirred with a mixture of methanol (0.8 mL) and hexanes (1.9 mL). The solid was filtered, resuspended in methanol/hexanes (1:3, 4.5 mL), and stirred to obtain a fine suspension. The suspension was filtered and dried to give the pure compound, 8, as a white solid (0.64 g, 65%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.06 (s, 1H), 7.69 (d, 2H, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.43−7.4 (m, 2H), 7.31 (d, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.06 (t, 2H, J = 8.3 Hz), 6.29 (s, 1H), 2.43 (s, 3H).

Synthesis of 1-Fluoro-4-(isocyano(tosyl)methyl)benzene (9).

To a solution of N-((4-fluorophenyl)(tosyl)methyl)formamide 8 (0.20 g, 0.65 mmol) in 1,2-dimethoxyethane (3.5 mL) at −10 °C was added POCl3 (0.15 mL, 1.6 mmol) followed by Et3N (0.46 mL, 3.3 mmol), keeping the internal temperature below −5 °C. The reaction was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 2 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by addition of ice-cold water, and the aqueous phase was extracted with methyl tert-butylether (2 × 15 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (1 × 10 mL) and brine (1 × 10 mL) and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was triturated with hexanes to give the desired product as a brown solid (0.11 g, 55%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.65 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.38−7.37 (m, 4H),7.12 (t, 2H, J = 8.3 Hz), 5.61 (s, 1H), 2.5 (s, 3H).

Synthesis of 4-(Dimethoxymethyl)-2-(methylthio)pyrimidine (13).

A mixture of pyruvic aldehyde dimethylacetal, 10 (6.0 mL, 50 mmol), and N,N-dimethylformamide dimethylacetal (6.0 mL, 45 mmol) was heated at 100 °C for 18 h. After the mixture was cooled to room temperature, methanol (30.0 mL), thiourea (6.96 g, 91.4 mmol), and sodium methoxide (25% in MeOH, 23.1 mL, 106 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was then stirred at 70 °C for 2 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled, iodomethane (14.4 mL, 231 mmol) was added dropwise, and the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The reaction mixture was then diluted with ethyl acetate (200 mL) and water (100 mL). The organic phase was separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 100 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the corresponding product, 13, as a brown oil (7.5 g, 75%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.56 (d, 1H, J = 5.1 Hz), 7.19 (d, 1H, J = 4.9 Hz), 5.19 (s, 1H), 3.42 (s, 6H), 2.58 (s, 3H).

Synthesis of 2-(Methylthio)pyrimidine-4-carbaldehyde (14).

A solution of 4-(dimethoxymethyl)-2-(methylthio)pyrimidine 13 (2.0 g, 10 mmol) in 3 N HCl (8.4 mL, 25 mmol) was stirred at 48 °C for 16 h. The reaction was cooled and quenched by addition of solid Na2CO3. The residue was washed with ethyl acetate (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic phase was dried and concentrated to give the crude product, which was purified by filtration over a pad of silica gel eluting with dichloromethane to give the pure product as a pale-yellow solid (0.6 g, 40%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.96 (d, 1H, 0.6 Hz), 8.77 (dd, 1H, J = 4.8, 0.5 Hz), 7.45 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 2.64 (s, 3H).

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(((2-(Methylthio)pyrimidin-4-yl)methylene)amino)piperidine-1-carboxylate (15).

To a solution of 2-(methylthio)pyrimidine-4-carbaldehyde, 9 (0.20 g, 1.3 mmol), and tert-butyl 4-aminopiperidine-1-carboxylate (0.26 g, 1.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (3 mL) was added anhydrous magnesium sulfate (0.31 g, 2.6 mmol), and the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. After confirmation of the completion of reaction by TLC, the reaction mixture was filtered, and the solvent was evaporated to give the desired product, which was taken directly to the next step.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl-(4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylthio)-pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (16).

A mixture of tert-butyl 4-(((2-(methylthio)pyrimidin-4-yl)methylene)-amino)piperidine-1-carboxylate, 15 (0.44 g, 1.3 mmol); 1-fluoro-4-(isocyano(tosyl)methyl)benzene, 4 (0.38 g, 1.3 mmol); and potassium carbonate (0.18 g, 1.3 mmol) in DMF at room temperature was stirred for 48 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by the addition of water and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 25 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with 5% aqueous LiCl and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the crude product, which was purified by column chromatography over silica gel (60−120 mesh) using ethyl acetate and hexanes as eluent (0−60%) to give the desired product as a yellow solid (0.17 g, 28%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.35 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.45−7.41 (m, 2H), 7.03 (t, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.79 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.85 (tt, 1H, J = 12.0, 3.6 Hz), 4.31 (br s, 2H), 2.84−2.78 (m, 2H), 2.6 (s, 3H), 2.19− 2.16 (m, 2H), 1.86 (dq, 2H, J = 12.3, 4.1 Hz), 1.49 (s, 9H).

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylsulfonyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (17).

A solution of OXONE (160 mg, 0.25 mmol) in water (1.4 mL) was added dropwise to a solution of tert-butyl 4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylthio)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-piperidine-1-carboxylate, 16 (50 mg, 0.11 mmol), in THF (2.0 mL) at −10 °C. The reaction mixture was then stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by addition of ice-cold water and extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with brine and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the desired product as a pale-yellow foam (45 mg, 84%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.50 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.42−7.35 (m, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.00 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 3.72−3.64 (m, 4H), 3.32 (s, 3H), 2.28−2.11 (m, 2H), 2.00−1.81 (m, 2H).

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(5-(2-(3,5-Dimethylphenoxy)pyrimidin-4-yl)-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (18).

To a suspension of NaH (60% in mineral oil, 9 mg, 0.04 mmol) in anhydrous THF (2 mL) was added 3,5-difluorophenol (50 mg, 0.40 mmol) in anhydrous THF (0.5 mL) dropwise at room temperature. The mixture was stirred for 10 min; this was followed by the addition of tert-butyl 4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylsulfonyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate, 17 (45 mg, 0.091 mmol), in anhydrous THF (0.5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 0.5 h, quenched by the addition of water, and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried and concentrated to give the product, which was taken to the next step without further purification (29 mg, 59%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.37 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.48−7.41 (m, 2H), 7.05 (t, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.91 (dt, J = 1.5, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 6.87−6.79 (m, 3H), 4.69 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 4.22−4.01 (m, 2H), 2.48 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 2H), 2.34 (s, 6H), 1.95−1.88 (m, 2H), 1.70 (dd, J = 11.7, 4.2 Hz, 2H), 1.48 (s, 9H). ESI-MS: calcd: 543.3, found: 544.3 (M+H).

Synthesis of 2-(3,5-Dimethylphenoxy)-4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl)pyrimidine (I).

To a solution of compound 18 (29 mg, 0.053 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.1 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The solvent was evaporated, and the crude sample was triturated with diethyl ether to give the desired product, I, as a white solid (2TFA salt; 25 mg, 70%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 8.41 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (s, 1H), 7.40−7.33 (m, 2H), 7.10 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (s, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (s, 2H), 4.64 (ddd, J = 11.9, 7.9, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 3.29−3.25 (m, 2H), 2.61 (td, J = 13.1, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 2.26 (s, 6H), 2.15−2.08 (m, 2H), 1.99 (qd, J = 13.1, 4.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 165.1, 164.5 (d, J = 248.7 Hz), 162.5, 160.9 (d, J = 36.4 Hz), 160.6, 157.6, 152.9, 139.7, 139.0, 136.2, 130.9 (d, J = 8.9 Hz), 127.0, 126.4, 125.0, 119.0, 116.7, 115.9 (d, J = 22.7 Hz), 115.7, 115.4, 52.4, 43.1, 29.5, 19.9. HRMS: calcd: 444.2200, found: 444.2207. HPLC Purity: 97.2%.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(p-tolyloxy)-pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (19).

To a suspension of NaH (60% in mineral oil, 13 mg, 0.56 mmol) in anhydrous THF (2 mL) was added p-cresol (66 mg, 0.62 mmol) in anhydrous THF (0.5 mL) dropwise at room temperature. The mixture was stirred for 10 min, which was followed by the addition of tert-butyl 4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylsulfonyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate, 17 (70 mg, 0.14 mmol), in anhydrous THF (0.5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 0.5 h, quenched by the addition of water, and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried and concentrated to give the product, which was taken to the next step without further purification (65 mg, 88%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.38 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.47−7.39 (m, 2H), 7.26−7.21 (m, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.08−7.00 (m, 2H), 6.84 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (tt, J = 11.9, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 4.21− 3.99 (m, 2H), 2.46 (t, J = 12.8 Hz, 2H), 2.38 (s, 3H), 1.91−1.84 (m, 2H), 1.70 (dt, J = 12.3, 6.1 Hz, 2H), 1.48 (s, 9H).

Synthesis of 4-(4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl)-2-(p-tolyloxy)pyrimidine (II).

To a solution of compound 19 (65 mg, 0.12 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.1 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The solvent was evaporated, and the crude was triturated with diethyl ether to give the desired product, II, as a white solid (2TFA salt; 35 mg, 50%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 8.55 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.50−7.46 (m, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.25−7.19 (m, 4H), 6.98 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.77 (tt, J = 11.6, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 3.44−3.36 (m, 2H), 2.76 (td, J = 13.0, 3.2 Hz, 2H), 2.42 (s, 3H), 2.23−2.09 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 165.3, 164.6, (d, J = 249.3 Hz), 162.6, 161.2, 161.0, (d, J = 35.5 Hz), 157.7, 150.7, 138.2, 136.1, 135.4, 131.0 (d, J = 9.0 Hz), 130.9, 130.0, 125.8, 125.0, 121.3, 116.8, 115.9 (d, J = 21.8 Hz), 115.8, 52.5, 43.0, 29.4, 19.5. HRMS: calcd: 430.2043, found: 430.2041. HPLC Purity: 99.5%.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(5-(2-(3,4-Dimethylphenoxy)pyrimidin-4-yl)-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (20).

To a suspension of NaH (60% in mineral oil, 9.0 mg, 0.36 mmol) in anhydrous THF (2 mL) was added 3,4-dimethylphenol (50 mg, 0.40 mmol) in anhydrous THF (0.5 mL) dropwise at room temperature. The mixture was stirred for 10 min; this was followed by the addition of tert-butyl 4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylsulfonyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate, 17 (45 mg, 0.091 mmol), in anhydrous THF (0.5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 0.5 h, quenched by the addition of water, and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried and concentrated to give the product, which was taken to the next step without further purification (47 mg, 95%). ESI-MS: calcd: 543.3, found: 544.3 (M+H).

Synthesis of 2-(3,4-Dimethylphenoxy)-4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl)pyrimidine (III).

To a solution of compound 20 (47 mg, 0.86 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.1 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The solvent was evaporated, and the crude was triturated with diethyl ether to give the desired product, III, as a white solid (2TFA salt; 30 mg, 52%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 8.53 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 7.51−7.45 (m, 2H), 7.26 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.24−7.19 (m, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (dq, J = 11.9, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.42−3.33 (m, 2H), 2.73 (td, J =13.0, 3.1 Hz, 2H), 2.33 (s, 6H), 2.25−2.16 (m, 2H), 2.10 (qd, J =12.9, 3.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 165.3, 164.6 (d, J = 248.9 Hz), 162.6, 160.8, (d, J = 35.1 Hz) 157.1, 150.8, 138.3, 137.9, 136.0, 134.0, 131.1, 131.0 (d, J = 8.6 Hz), 130.3, 129.8, 125.5, 125.1, 122.3, 118.6, 116.8, 115.9 (d, J = 22.1 Hz), 115.8, 52.6, 43.0, 29.4, 18.5, 17.8. HRMS: calcd: 444.2200, found: 444.2226. HPLC Purity: 99.7%.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(5-(2-((3,4-Dimethylphenyl)amino)-pyrimidin-4-yl)-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (21).

A mixture of 3,4-dimethylaniline (150 mg, 1.25 mmol) and tert-butyl 4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylsulfonyl)-pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate, 17 (65 mg, 0.13 mmol), in 1,4-dioxane (1 mL) were heated in a sealed tube at 140 °C for 16 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by the addition of water and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic phase was dried and concentrated to give the product, which was purified by column chromatography over silica gel (60−120 mesh) using ethyl acetate and hexanes as eluent (70−100%, 32 mg, 46%). The product was taken to the next step without further purification.

Synthesis of N-(3,4-Dimethylphenyl)-4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl)pyrimidin-2-amine (IV).

To a solution of compound 21 (32 mg, 0.059 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.1 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The solvent was evaporated, and the crude was triturated with diethyl ether to give the desired product, IV, as a pale-yellow solid (3TFA salt; 23 mg, 50%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 8.28 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (s, 0.5H), 7.55−7.46 (m, 2H), 7.35 (dq, J = 4.7, 2.4 Hz, 2H), 7.22−7.09 (m, 3H), 6.52 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (ddt, J = 12.1, 8.3, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 3.42−3.34 (m, 2H), 2.76−2.67 (m, 2H), 2.39 (dt, J = 13.3, 2.7 Hz, 2H), 2.28 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 6H), 2.15 (qd, J = 13.2, 4.2 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 163.9, 161.9, 161.7, 161.4, 160.8, 158.5, 157.0, 139.9, 137.0, 136.6, 135.8, 131.6, 130.5, 130.4, 129.4, 125.4, 122.8, 119.0, 117.9, 115.4, 115.2, 112.4, 51.6, 43.1, 29.7, 18.6, 17.8. HRMS: calcd: 443.2359, found: 443.2345. HPLC Purity: 97.5%.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(5-(2-((3,5-Dimethylphenyl)amino)-pyrimidin-4-yl)-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (22).

A mixture of 3,5-dimethylaniline (100 mg, 0.825 mmol) and tert-butyl 4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylsulfonyl)-pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate, 17 (45 mg, 0.091 mmol), was heated in a sealed tube at 140 °C for 16 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by the addition of water and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the product, which was purified by column chromatography over silica gel (60−120 mesh) using ethyl acetate and hexanes as eluent (70−100%, 27 mg, 55%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.25 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (s, 1H), 7.53−7.45 (m, 2H), 7.22−7.18 (m, 3H), 7.06−6.98 (m, 2H), 6.75 (s, 1H), 6.56 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.86−4.74 (m, 1H), 4.12 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.44 (dd, J = 15.7, 9.9 Hz, 2H), 2.32 (s, 6H), 1.84− 1.69 (m, 4H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

Synthesis of N-(3,5-Dimethylphenyl)-4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl)pyrimidin-2-amine (V).

To a solution of compound 22 (30 mg, 0.05 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.1 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The solvent was evaporated, and the crude was triturated with diethyl ether to give the desired product, V, as a pale-yellow solid (3TFA salt; 37 mg, 96%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.29 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (s, 1H), 7.51 (dd, J = 8.4, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (s, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.04 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.76 (s, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 3.15−3.08 (m, 2H), 2.49−2.40 (m, 2H), 2.34 (s, 6H), 2.12−2.05 (m, 2H), 1.84 (qd, J = 12.2, 3.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 164.4, (d, J = 247.6 Hz) 162.4, 160.7, 158.8, 156.0, 152.6, 148.2, 139.1, 138.2, 135.4, 130.7, (d, J = 8.4 Hz) 130.6, 124.8, 119.0, 115.8, (d, J = 22.1 Hz) 115.6, 112.6, 52.3, 48.1, 43.0, 29.5, 20.1. HRMS: calcd: 443.2359, found: 443.2388. HPLC Purity: 95.7%.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(5-(2-(3,5-Difluorophenoxy)pyrimidin-4-yl)-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (23).

To a suspension of NaH (60% in mineral oil, 9 mg, 0.04 mmol) in anhydrous THF (2 mL) was added 3,5-dimethylphenol (50 mg, 0.40 mmol) in anhydrous THF (0.5 mL) dropwise at room temperature. The mixture was stirred for 10 min; this was followed by the addition of tert-butyl 4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylsulfonyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate, 17 (45 mg, 0.091 mmol), in anhydrous THF (0.5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 0.5 h, quenched by the addition of water and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried and concentrated to give the product, which was taken to the next step without further purification (29 mg, 59%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 8.46 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 7.5− 7.3 (m, 2H), 7.09 (t, 2H), 6.95 (dt, 3H), 6.87 (tt, J = 9.2, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.7−4.6 (m, 1H), 3.5−3.4 (m, 3H), 2.88 (td, J = 13.1, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 2.21 (d, J = 13.4 Hz, 2H), 2.10 (qd, J = 13.0, 4.1 Hz, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H). 1.22 (s, 1H), 1.19 (s, 2H), 0.8−0.7 (m, 1H). ESI-MS: calcd: 551.6, found: 552.1 (M+H).

Synthesis of 2-(3,5-Difluorophenoxy)-4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazol-5-yl)pyrimidine (VI).

To a solution of compound 23 (45 mg, 0.82 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.1 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The solvent was evaporated, and the crude was triturated with diethyl ether to give the desired product, VI, as a white solid (2TFA salt; 31 mg, 56%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 8.46 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.40−7.32 (m, 1H), 7.14−7.03 (m, 1H), 6.99−6.82 (m, 2H), 3.44−3.36 (m, 2H), 2.88 (td, J = 13.1, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 2.21 (d, J = 13.4 Hz, 1H), 2.10 (qd, J = 13.0, 4.1 Hz, 2H), 1.19 (s, 1H), 0.84−0.73 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 163.3 (dd, JC−F = 248.8, 15.2 Hz), 161.1 (d, JC−F = 35.2 Hz), 160.6, 158.6, 154.7 (d, J C−F = 13.4 Hz), 136.5, 130.7 (d, JC−F = 8.5 Hz), 117.7, 115.6 (d, JC−F = 22.1 Hz), 105.8 (t, JC−F = 22.1, 21.5 Hz), 100.9 (t, JC−F = 26.1 Hz), 51.9, 43.2, 29.7. HRMS: calcd: 451.1680, found: 452.2210. HPLC Purity: 97.9%.

Synthesis of Triazoles VII−IX.

Synthesis of Sulfones 31, 32, and 33. Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-Azidopiperidine-1-carboxylate (24).

To a solution of tert-butyl 4-((methylsulfonyl)oxy)piperidine-1-carboxylate (1.1 g, 3.9 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) was added solid NaN3 (0.48 g, 7.3 mmol). The reaction was sealed under air and heated to 75 °C. After 20 h, the reaction was cooled to room temperature. The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were washed with water and brine, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. This afforded azide 24 quantitatively, which was used without further purification. Characterization data for this compound have been previously reported.52

General Click Procedure and Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (25).

The crude oil of azide 24 (3.9 mmol, assuming quantitative yield from previous reaction) was dissolved in t-BuOH/H2O (1:1, 10 mL). A separate vial was charged with alkyne (660 mg, 4.8 mmol), copper sulfate pentahydrate (40 mg, 0.16 mmol), and sodium ascorbate (170 mg, 0.84 mmol). The solution of azide was transferred into the vial containing alkyne by pipet and sealed under air. After 18 h at room temperature, the reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford the triazole (1.10 g, 77%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.81 (apparent dd, J = 8.8, 5.3 Hz, 2H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.13 (apparent t, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 4.67 (tt, J = 11.6, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (br, 2H), 2.97 (br, 2H), 2.28−2.22 (m, 2H), 2.00 (qd, J = 12.2, 4.4 Hz, 2H), 1.50 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.7 (d, JC−F = 247.4 Hz), 154.5, 146.8, 127.4 (d, JC−F = 8.1 Hz), 126.8 (d, JC−F = 3.2 Hz), 117.1, 115.9 (d, JC−F = 21.6 Hz), 80.2, 58.3, 42.7 (br), 32.5, 28.4. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −113.5. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2974, 1689, 1496, 1424, 1244, 1166. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C18H23FN4 NaO2 +, (M+Na)+ 369.1697, found 369.1682.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(((tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (26).

The General Click Procedure was used, and the product, 26, was isolated as a white solid in 83% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.47 (s, 1H), 4.84 (s, 2H), 4.59 (tt, J = 11.6, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.26 (br, 2H), 2.93 (t, J = 13.1 Hz, 2H), 2.26−2.12 (m, 2H), 1.94 (apparent qd, J = 12.3, 4.4 Hz, 2H), 1.47 (s, 9H), 0.91 (s, 9H), 0.10 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.7, 148.7, 119.4, 80.3, 58.2, 58.2, 42.9 (br) 32.6, 28.6, 26.1, 18.5, −5.1. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2930, 2857, 1696, 1423, 1366, 1244, 1168, 838, 778. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C19H36N4NaO3Si+, (M+Na)+ 419.2449, found 419.2452.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-Methyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-piperidine-1-carboxylate (27).

The crude oil of the azide (3.6 mmol, assuming quantitative yield from previous reaction) was dissolved in t-BuOH/H2O (1:1, 20 mL). A separate three-neck round-bottom flask was charged with copper sulfate pentahydrate (290 mg, 1.2 mmol) and sodium ascorbate (710 mg, 3.6 mmol). The solution of azide was transferred into this flask by pipet. The center neck of the flask was fitted with a condensing dewar which was filled with a dry ice/acetone bath. The other two necks were sealed with septa. The top of the condensing dewar was vented by needle, and this vent remained open to avoid over pressurization. Propyne was bubbled into the solution of azide by needle until the propyne started to reflux in the condensing dewar. After 1 h at room temperature, the flask was placed on a 40 °C heating block to melt the ice that formed in the flask as a result of propyne condensation. After 4 h at this temperature, the reaction was cooled to room temperature, and the mixture was diluted with water and brine and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford the triazole quantitatively as a pale-green solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.96 (s, 1H), 4.64 (tt, J = 11.4, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 4.04 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (br, 2H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 2.02 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 2H), 1.80 (qd, J = 12.2, 4.3 Hz, 2H), 1.42 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 154.3, 142.9 (br), 121.3, 79.4, 57.3, 43.1 (br), 32.4, 28.5, 11.1. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2974, 1689, 1424, 1366, 1250, 1169, 1004. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C13H22N4NaO2 +, (M+Na)+ 289.1635, found 289.1632.

General Coupling Procedure and Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylthio)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (28).

A solution of triazole 25 (170 mg, 0.50 mmol) in THF (8 mL) was cooled in a dry ice/acetone bath. Then n-BuLi (0.26 mL, 2.5 M in hexanes, 0.65 mmol) was added dropwise. After 10 min, a freshly prepared solution of ZnCl2 (110 mg, 0.78 mmol) in THF (1 mL) was added dropwise. After 10 min, a freshly prepared solution of SPhos Pd G3 (17 mg, 22 μmol) in THF (1 mL) was added followed by chloro-pyrimidine (0.12 mL, 1.0 mmol). The reaction was heated to 60 °C. After 1.5 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Final purification by column chromatography (0− 50% EtOAc in hexanes) yielded the product as a white solid (210 mg, 88%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.50 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (apparent dd, J = 8.6, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (apparent t, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.86 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.96 (tt, J = 11.4, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (br, 2H), 2.89 (br, 2H), 2.61 (s, 3H), 2.42−2.28 (m, 2H), 2.23−2.06 (m, 2H), 1.50 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.9, 163.1 (d, JC−F = 248.9 Hz), 158.0, 155.3, 154.6, 146.3, 130.3 (d, JC−F = 8.3 Hz), 129.3, 126.4 (d, JC−F = 3.3 Hz), 116.5, 116.0 (d, JC−F = 21.8 Hz), 80.0, 57.8, 43.0 (br), 32.3, 28.4, 14.1. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −112.2. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2976, 2930, 2863, 1692, 1550, 1506, 1420, 1349, 1243, 1158, 997, 913, 841, 732. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C23H27FN6NaO2S+, (M+Na)+ 493.1792, found 493.1774.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(((tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-methyl)-5-(2-(methylthio)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-piperidine-1-carboxylate (29).

A solution of triazole 26 (830 mg, 2.1 mmol) in THF (15 mL) was cooled in a dry ice/acetone bath. Then n-BuLi (1.1 mL, 2.5 M in hexanes, 2.7 mmol) was added dropwise. After 10 min, a freshly prepared solution of ZnCl2 (370 mg, 2.7 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added dropwise. After 10 min, a freshly prepared solution of SPhos Pd G3 (71 mg, 91 μmol) in THF (5 mL) was added followed by chloro-pyrimidine (0.36 mL, 3.1 mmol). The reaction was heated to 60 °C. After 18 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Final purification by column chromatography (0−80% EtOAc in hexanes) yielded the product as a white solid (990 mg, 92%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.64 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 5.24 (tt, J = 11.3, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.83 (s, 2H), 4.28 (br, 2H), 2.88 (br, 2H), 2.58 (s, 3H), 2.28 (qd, J = 11.8, 4.1 Hz, 2H), 2.18− 2.11 (m, 2H), 1.47 (s, 9H), 0.87 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 9H), 0.09 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.2, 158.4, 154.7, 154.6, 146.9, 131.6, 116.3, 80.0, 58.1, 57.1, 42.9, 32.4, 28.5, 25.9, 18.3, 14.2, −5.1. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2929, 2856, 1697, 1542, 1419, 1157, 837. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C24H40N6NaO3SSi+, (M+Na)+ 543.2544, found 543.2529.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(((tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-methyl)-5-(2-(methylthio)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-piperidine-1-carboxylate (30).

A variation of the general coupling procedure was used. After the addition of SPhos Pd G3 and electrophile 27, the reaction was heated to 60 °C for 3.5 h. Final purification by column chromatography (0−60% IPA in hexanes) yielded the product (210 mg, 52%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.65 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 5.11 (tt, J = 11.3, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (br, 2H), 2.86 (br, 2H), 2.58 (s, 3H), 2.49 (s, 3H), 2.26 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 2H), 2.10 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 2H), 1.47 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.5, 158.1, 155.0, 154.6, 143.8, 129.6, 115.1, 79.9, 57.8, 42.6 (br), 32.2, 28.4, 14.1, 12.1. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2974, 2930, 2864, 1691, 1548, 1422, 1276, 1162, 1006. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C18H26N6NaO2S+, (M+Na)+ 413.1730, found 413.1732.

General Oxidation Procedure and Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(2-(methylsulfonyl)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (31).

To a solution of thioether 28 (350 mg, 0.74 mmol) in THF (10 mL) cooled in an ice bath, a solution of oxone (690 mg, 2.3 mmol) in water (3 mL) was added dropwise. The reaction was sealed under air and warmed to rt. After 20 h, the reaction was diluted with ice water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phase was washed with brine, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. This afforded sulfone 31 (330 mg, 66%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.80 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (apparent dd, J = 8.8, 5.2 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (apparent t, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.15 (tt, J = 10.6, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (br, 2H), 3.41 (s, 3H), 2.97 (br, 2H), 2.44−2.16 (m, 4H), 1.48 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 163.4 (d, JC−F = 250.2 Hz), 158.9, 157.0, 154.6, 147.7, 130.6 (d, JC−F = 8.3 Hz), 128.0, 126.0 (d, JC−F = 3.3 Hz), 122.8, 116.4 (d, JC−F = 21.8 Hz), 79.9, 59.2, 43.3 (br), 39.1, 32.4, 28.4. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −110.9. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2977, 2929, 1685, 1578, 1507, 1420, 1324, 1244, 1159, 1135, 843. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C23H27FN6NaO4S+, (M +Na)+ 525.1691, found 525.1688.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(((tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-methyl)-5-(2-(methylthio)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-piperidine-1-carboxylate (32).

To a solution of thioether 29 (290 mg, 0.56 mmol) in THF (10 mL) cooled in an ice bath, a solution of oxone (400 mg, 1.3 mmol) in H2O (4 mL) was added dropwise. The reaction was sealed under air and warmed to room temperature. After 20 h, the reaction was diluted with ice water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude material was dissolved in DCM (5 mL). To this solution, imidazole (65 mg, 0.95 mmol) was added followed by TBSCl (130 mg, 0.85 mmol). The reaction was sealed under air at room temperature. After 3 h, the reaction was quenched by the addition of water and extracted with DCM. The combined organic phases were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. This afforded sulfone 32 (275 mg, 89%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.07 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 8.35 (d, J = 5.3, 1H), 5.40−5.27 (m, 1H), 4.91 (br, 2H), 4.31 (br, 2H), 3.42 (s, 3H), 3.01 (br, 2H), 2.26 (br, 4H), 1.49 (s, 9H), 0.92 (s, 9H), 0.10 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.1, 159.7, 156.0, 154.6, 148.0, 130.4, 123.2, 80.0, 59.4, 55.9, 43.3, 39.2, 32.4, 30.3, 28.4, 25.7, −3.6. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2977, 2932, 1684, 1582, 1429, 1320, 1161, 1006, 736. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C24H40N6NaO5SSi+, (M+Na)+ 575.2442, found 575.2430.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-Methyl-5-(2-(methylsulfonyl)-pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (33).

The General Oxidation Procedure was used with thioether 30, and the sulfone was isolated in quantitative yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.02 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 5.35−5.06 (m, 1H), 4.26 (br, 2H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 2.94 (br, 2H), 2.58 (s, 3H), 2.36−2.09 (m, 4H), 1.45 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.3, 159.3, 156.7, 154.6, 145.1, 128.4, 121.5, 79.8, 59.1, 42.8 (br), 39.2, 32.3, 28.4, 12.6. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2976, 2931, 1687, 1580, 1452, 1426, 1321, 1249, 1163, 1007. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C18H26N6NaO4S+, (M+Na)+ 445.1628, found 445.1623.

General Nucleophilic-Aromatic-Substitution Procedure and Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(5-(2-((3,5-Dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxy-late (34).

To a vial containing sulfone 31 (85 mg, 0.170 mmol), 2,5-dimethylaniline (0.21 mL, 1.7 mmol) was added neat. The vial was sealed under air and heated to 100 °C. After 3 h, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and diluted with THF (0.5 mL), and then Boc2O (0.10 mL, 0.44 mmol) was added. After an additional 2 h at room temperature, the reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification by column chromatography (0−60% IPA in hexanes with 1% TEA) yielded semipure material. The purified material was recrystallized in DCM and hexanes to afford the desired product, 34 (54 mg, 59%), as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.41 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (apparent dd, J = 8.7, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.20 (s, 2H), 7.10 (apparent t, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.80 (s, 1H), 6.61 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.93 (tt, J = 11.4, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (br, 2H), 2.58 (br, 2H), 2.33 (s, 6H), 2.32−2.19 (m, 2H), 2.09− 2.02 (m, 2H), 1.49 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 163.0 (d, JC−F = 248.4 Hz), 160.7, 159.3, 156.0, 154.5, 145.7, 138.7, 138.3, 130.2 (d, JC−F = 8.2 Hz), 130.0, 126.6 (d, JC−F = 3.1 Hz), 125.7, 118.4, 115.8 (d, JC−F = 21.7 Hz), 112.9, 79.9, 57.3, 42.7 (br), 32.2, 28.4, 21.4. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −112.7. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2974, 1691, 1536, 1430, 1160. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C30H34FN7NaO2+, (M+Na)+ 566.2650, found 566.2643.

General Boc-Deprotection Procedure and Synthesis of N-(3,5-Dimethylphenyl)-4-(4-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-5-yl)pyrimidin-2-amine (VII).

To a solution of Boc-protected amine 34 (18 mg, 32 μmol) in DCM (0.5 mL) at room temperature was added TFA (0.5 mL). After 1 h, the product was concentrated under reduced pressure. This afforded the product quantitatively as a yellow solid. The ratio of TFA and amine was determined by 19F NMR. 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.44 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (apparent dd, J = 8.8, 5.3 Hz, 2H), 7.27−7.18 (m, 4H), 6.79 (s, 1H), 6.68 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 5.16 (tt, J = 10.7, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 3.52−3.45 (m, 2H), 2.96−2.86 (m, 2H), 2.55−2.36 (m, 4H), 2.31 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 163.2 (d, JC−F = 247.6 Hz), 160.8, 159.0, 155.2, 145.4, 139.0, 138.2, 130.9, 130.1 (d, JC−F = 8.4 Hz), 126.2, 124.9, 118.9, 115.5 (d, JC−F = 22.1 Hz), 112.0, 54.0, 42.7, 28.8, 20.1. 19F NMR (376 MHz, MeOD) δ −77.5 (9H), −114.3 (1H). IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2916, 2850, 1676, 1624, 1592, 1510, 1457, 1198, 1186, 1160, 1143. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C25H26FN7Na+, (M +Na)+ 466.2126, found 466.2117. HPLC Purity: 96.3%.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-(((tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-methyl)-5-(2-((3,5-dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (35).

To a solution of 3,5-dimethylaniline (0.02 mL, 0.2 mmol) in THF (2 mL) cooled in a dry ice/acetone bath was added NaHMDS (0.28 mL, 1 M in THF, 0.28 mmol). After 5 min, a solution of sulfone 32 (62 mg, 0.11 mmol) in THF (2 mL) was added dropwise. After an additional 30 min, the reaction was quenched with water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification by column chromatography (0−55% EtOAc in hexanes) yielded the desired product, 35 (39.1 mg, 59%), as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.55 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (s, 1H), 7.14 (s, 2H), 6.79 (s, 1H), 5.16 (tt, J = 11.3, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.87 (s, 2H), 4.11 (br, 2H), 2.51 (br, 2H), 2.32 (s, 6H), 2.24−2.15 (m, 2H), 2.07−1.96 (m, 2H), 1.48 (s, 9H), 0.91 (s, 9H), 0.13 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.3, 159.4, 155.2, 154.5, 146.3, 138.6, 138.3, 132.3, 125.8, 118.9, 112.6, 79.8, 57.4, 56.9, 42.2, 32.1, 28.4, 25.9, 21.4, 18.3, −5.1. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2927, 2854, 1688, 1596, 1453, 1330, 1250, 1158. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C31H47N7NaO3Si+, (M+Na)+ 616.3402, found 616.3394.

Synthesis of (5-(2-((3,5-Dimethylphenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methanol (VIII).

To a solution of Boc-protected amine 35 (39 mg, 66 μmol) in DCM (0.5 mL) at room temperature was added TFA (0.5 mL). After 3 h, the solution was heated to 40 °C. After 1 h, the reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure. Analysis by 19F NMR with 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol as the standard indicated the formation of a mono-TFA salt in quantitative yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.60 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 6.79 (s, 2H), 5.36 (tt, J = 10.8, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 4.79 (s, 2H), 3.44 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 2H), 2.91− 2.75 (m, 2H), 2.48−2.32 (m, 4H), 2.31 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 160.8, 159.6, 154.3, 146.1, 139.1, 138.1, 132.6, 124.9, 119.3, 111.6, 54.4, 54.1, 42.7, 28.8, 20.1. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2932, 2859, 1679, 1627, 1595, 1463, 1403, 1190, 1139, 1076. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C20H25N7NaO+, (M+Na)+ 402.2013, found 402.2022. HPLC Purity: 96.9%.

Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(5-(2-((3,5-Dimethylphenyl)amino)-pyrimidin-4-yl)-4-methyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (36).

A variation of the General SNAr Procedure was used with sulfone 33. The product was purified by prep TLC (20% IPA in hexanes), and the product was isolated in 68% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.54 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 1H), 7.15 (s, 2H), 6.83 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (s, 1H), 5.06 (tt, J = 11.4, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (s, 2H), 2.64−2.38 (m, 5H), 2.31 (s, 6H), 2.24−2.13 (m, 2H), 2.06−1.91 (m, 2H), 1.47 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.5, 159.3, 155.7, 154.5, 143.3, 138.6, 138.4, 130.4, 125.7, 118.9, 111.5, 79.8, 57.2, 42.3 (br), 32.1, 28.4, 21.4, 12.0. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2974, 2929, 1693, 1567, 1537, 1427, 1366, 1164. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C25H33N7NaO2+, (M+Na)+ 486.2588, found 486.2574.

Synthesis of N-(3,5-Dimethylphenyl)-4-(4-methyl-1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-5-yl)pyrimidin-2-amine (IX).

The General Boc-Deprotection Procedure was used with Boc-protected amine 36, and the product was isolated in quantitative yield. Analysis by 19F NMR with 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol as the standard indicated the formation of a bis-TFA salt in quantitative yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.57 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (s, 2H), 7.07 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (s, 1H), 5.30 (tt, J = 10.7, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 3.43 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 2H), 2.85−2.75 (m, 2H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.35−2.32 (m, 2H), 2.31 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 159.8, 157.8, 155.8, 143.4, 138.5, 138.4, 130.8, 125.5, 119.7, 110.8, 54.2, 42.7, 28.7, 20.1, 10.4. IR (NaCl, thin film, cm−1): 2925, 2852, 1681, 1628, 1593, 1513, 1460, 1198, 1141. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C20H25N7Na+, (M+Na)+ 386.2064, found 386.2053. HPLC Purity: 96.1%.

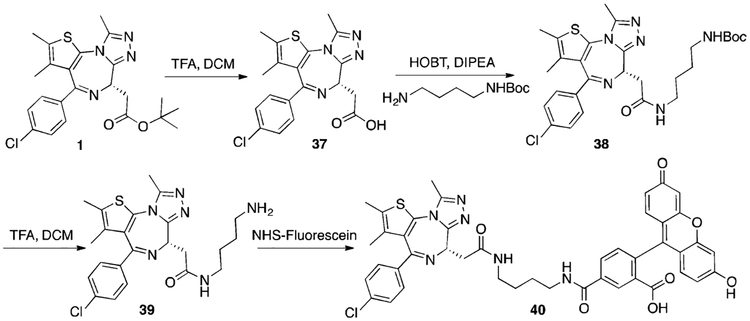

Synthesis of (S)-N-(4-Aminobutyl)-2-(4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,3,9-trimethyl-6H-thieno[3,2-f][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]diazepin-6-yl)-acetamide (39).

Commercially acquired (+)-JQ1 (Sigma, SML0974) was hydrolyzed to acid 37; conjugated to the N-Boc-1,4-butanediamine linker (Sigma, 15404); and deprotected to yield the free amine, 39, according to previously reported procedures.53

Synthesis of (S)-5-((4-(2-(4-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2,3,9-trimethyl-6H-thieno[3,2-f][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]diazepin-6-yl)acetamido)-butyl)carbamoyl)-2-(6-hydroxy-3-oxo-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoic Acid (40).

To a solution of 39 (8 mg, 12 μmol) in DCM (1 mL) was added NHS−fluorescein (6 mg, 13 mmol; Thermo Scientific, 46409). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature and purified using reverse-phase chromatography (Scheme 6). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C44H37ClN6O7S (M+H)+ 829.3250, found 829.3762; C44H37ClN6NaO7S (M+Na)+ 851.2031, found 851.3621.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of Fluorescein−JQ1 Tracer (40)

Protein Expression.

Expression of BRD4(1), BRD4(2), H437D BRD4(2), BRD4(1 + 2), BRDT(1), BRDT(2), BPTF, and 5FW-pfGCN5 in either unlabeled or 5FW-labeled forms was based on established methods using Escherichia coli Bl21(DE3) + pRARE strains26 and is briefly described here. To express the labeled protein, a secondary culture in LB media was grown to an OD at 600 nm of 0.6 was reached; this was followed by harvesting. Cells were resuspended in defined media containing 5-fluoroindole (60 mg/L) in place of tryptophan. The resuspended E. coli were incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 1.5 h. This was followed by cooling to 20 °C and media temperature equilibration for 30 min. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG overnight (14−16 h) at 20 °C. The cells were harvested and stored at −20 °C. Cell pellets were thawed at room temperature; this was followed by the addition of lysis buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl) containing PMSF (5 mM) and Halt protease-inhibitor cocktail, and proteins were purified using Ni-affinity chromatography. Purity of proteins was assessed by SDS-PAGE. Fluorinated amino acid incorporation efficiency in proteins was measured by LC-MS on a Waters Synapt G2 UPLC/QTOF-MS. Protein concentrations were determined via absorbance at 280 nm.

Fluorescence Anisotropy.

Fluorescence-anisotropy experiments were carried out in 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, and 4 mM CHAPS (pH 7.4) in 384-well plates (Corning 4511). Stock solutions (25 μM) of fluorescent tracer in DMSO were diluted to 15 nM for these experiments. Plates were read on a Tecan Infinity 500 with an excitation wavelength at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm. For direct-binding experiments, the protein was serially diluted across the plate, and the resulting anisotropy values were fit using eq 1 in GraphPad Prism, where b and c are the maximum and minimum anisotropy values, respectively; a is the concentration of fluorescent tracer; x is the concentration of protein; and y is the observed anisotropy value.

| (1) |