Abstract

a-Amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors are implicated in the pathology of neurological diseases such as epilepsy and schizophrenia. As pan antagonists for this target are often accompanied with undesired effects at high doses, one of the recent drug discovery approaches has shifted to subtype-selective AMPA receptor (AMPAR) antagonists, specifically, via modulating transmembrane AMPAR regulatory proteins (TARPs). The quantification of AMPARs by positron emission tomography (PET) would help obtain insights into disease conditions in the living brain and advance the translational development of AMPAR antagonists. Herein we report the design, synthesis and preclinical evaluation of a series of TARP γ−8 antagonists, amenable for radiolabeling, for the development of subtype-selective AMPA PET imaging agents. Based on the pharmacology evaluation, molecular docking studies and physiochemical properties, we have identified several promising lead compounds 3, 17–19 and 21 for in vivo PET studies. All candidate compounds were labeled with [11C]COCl2 in high radiochemical yields (13–31% RCY) and high molar activities (35–196 GBq/µmol). While trac ers 30 ([11C]17) & 32 ([11C]21) crossed the blood-brain barrier and showed heterogeneous distribution in PET studies, consistent with AMPA TARP γ−8 expression, high nonspecific binding prevented further evaluation. To our delight, tracer 31 ([11C]3) showed good in vitro specific binding and characteristic high uptake in the hippocampus in rat brain tissues, which provides the guideline for further development of a new generation subtype selective TARP γ−8 dependent AMPA tracers.

Keywords: ionotropic glutamate receptor, AMPA, transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory protein, TARP, positron emission tomography, epilepsy

Table of Contents graphic

INTRODUCTION

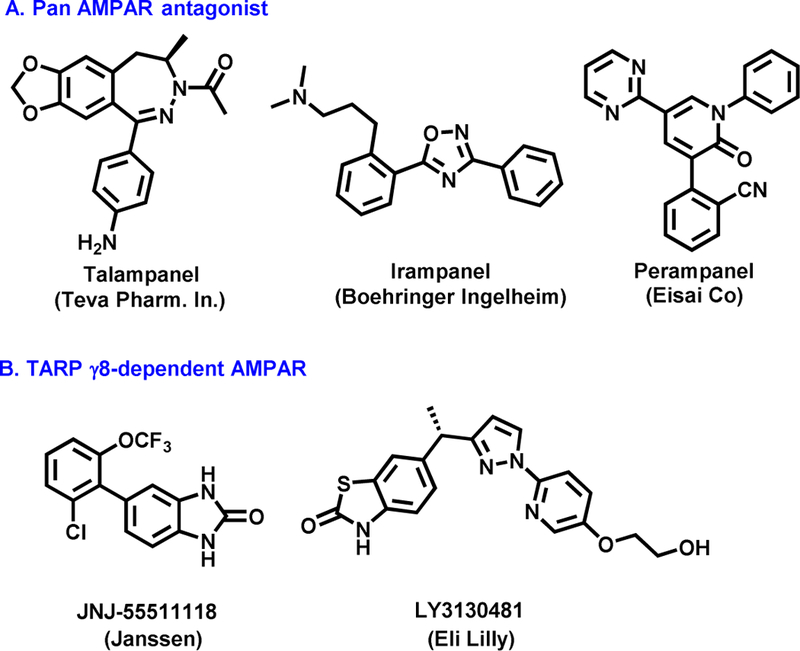

As the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian brain, glutamate exerts postsynaptic effects through a diversity of metabotropic and ionotropic receptors (mGluRs and iGluRs, respectively). [1, 2] In particular, iGluRs are glutamate-gated tetrameric ion channels. Based on their preferential ligands they can be further divided into three main categories, namely a-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, and kainate receptors. [3–6] The AMPA receptors (AMPARs) are primarily expressed on postsynaptic membranes of excitatory synapses and regulate fast synaptic transmission in the central nervous system (CNS). [7] AMPARs play a significant role in memory and learning, [3] and are also implicated in the etiology of several excitotoxic diseases such as epilepsy and ischemia. [8, 9] As a potential therapeutic target, early pharmacotherapies for CNS disorders caused by excessive neuronal activity have focused on pan AMPAR antagonists, including fanapanel, [10] becampanel, [11] tezampanel, [12] selurampanel, [13] talampanel, [14] irampanel, [15] and perampanel. [16–18] Perampanel (Fycompa™; Figure 1) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Since AMPARs are expressed ubiquitously in the CNS, these pan antagonists are often accompanied with undesired effects at high doses, such as dizziness, ataxia, and sedation. [17] To address these challenges, researchers have shifted their therapeutic approach to a new strategy utilizing subtype-selective AMPAR antagonists, specifically, via modulating transmembrane AMPAR regulatory proteins (TARPs). [19–21] As a recently discovered family of receptor auxiliary subunits, [22–24] TARPs have been found to associate with and regulate AMPAR trafficking, gating, protein levels as well as pharmacology. [25–27] TARPs are categorized into two subgroups based on their sequence homology, group I (γ−2/stargazin, γ−3, γ−4, and γ−8) and group II (γ−5, γ−7). Several TARPs are found to be distributed in the brain in a regiospecific manner, [28, 29] such as cerebellum-enriched TARP γ−2 and hippocampus-enriched TARP γ−8, highlighting the feasibility of selective regulation of AMPAR activity in specific brain circuits by targeting individual TARP subtypes without the aforementioned side effects. [30] In particular, TARP γ−8 antagonism is particularly promising for the development of therapies for pathologic disorders distinguished by hyperactivity within forebrain. [31–34] It is encouraging that there are several TARP γ−8-dependent antagonists including JNJ55511118[35] and LY3130481[36–38] debuted in late 2016, among which LY3130481 has been advanced to phase I clinical trial in 2017.

Figure 1.

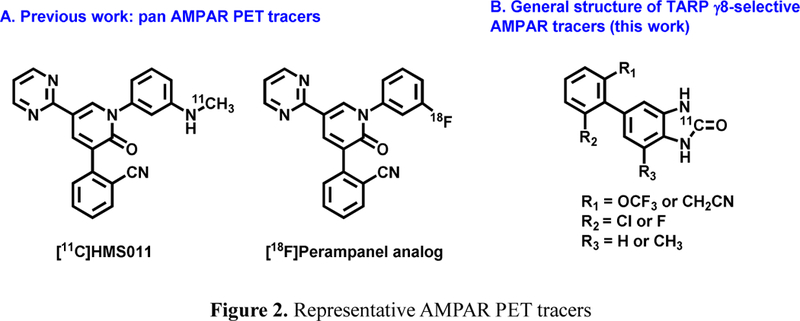

Representative AMPAR antagonists

As a non-invasive imaging technology, positron emission tomography (PET) is ideal for in vivo quantification of biochemical and pharmacological process under both normal and disease conditions with minimal perturbation of the original biological state. [39–41] PET imaging studies of AMPARs in the living brain would help to obtain insights into excitotoxic conditions and to advance the translational development of AMPAR antagonists via target engagement studies, as well as to enable pharmacokinetic profiling of candidate drug molecules. Despite the fact that several AMPAR PET tracers[42–45] have been developed including [11C]HMS011[46, 47] and our [18F]Perampanel analog, further improvement on target:nonspecific binding ratio is necessary for clinical research (Figure 2A). [47] Furthermore, there is no subtype-selective AMPAR PET tracer (i.e., regulated via specific TARP subgroup) available for drug discovery and translational human imaging studies, despite their advantage of significantly reduced side effects over traditional pan AMPAR antagonists. As a result, the unmet clinical need of AMPAR γ−8 selective PET tracers, together with the therapeutic potential of AMPA γ−8 modulating pharmacotherapy, provides a strong stimulus to advance PET tracer development for this target.

Figure 2.

Representative AMPAR PET tracers

As part of our continuing interest in the development of AMPAR-targeting PET tracers, [48] we presented herein a novel class of γ−8 dependent TARP AMPAR PET tracers. Our medicinal chemistry efforts concentrated on the synthesis of a focused array of 1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ones and benzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-ones based on recently discovered JNJ5551118 scaffold. [35] These molecules are amenable for radiolabeling with carbon-11 or fluorine-18 for PET imaging studies (Figure 2B). Preliminary pharmacology, molecule docking studies and physicochemical properties evaluation of top candidates were carried out to select the most promising γ−8 dependent TARP antagonists 3, 17–19 and 21 for in vivo evaluation using PET. Utilizing [11C]COCl2 labeling strategy, we first evaluated brain permeability and specificity of candidate compounds by PET and in vitro autoradiography studies. We also unveiled the underlying cause of low brain penetration for 31, the most in vitro specific tracer in our design, which provides a medicinal chemistry roadmap for future design of TARP γ−8 dependent AMPA antagonists and PET tracers.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry.

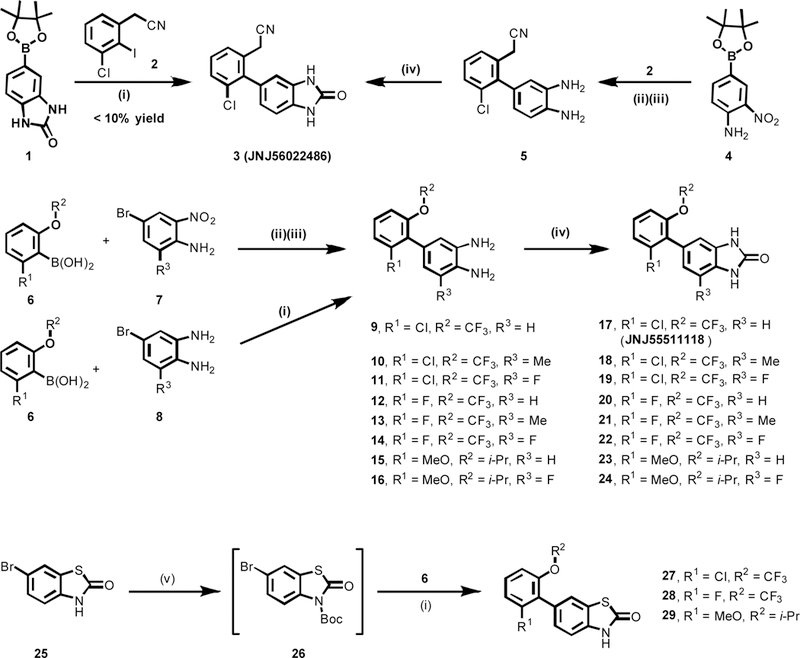

A focused library of 1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ones 3, 17–24 and benzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-ones 27–29 were synthesized with emphasis on amenability for radiolabeling with carbon-11 or fluorine-18. As summarized in Scheme 1, initial attempt on direct palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of (2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-5-yl)borate 1 with 2-(3-chloro-2-iodophenyl)acetonitrile 2 offered the desired urea-type AMPAR inhibitor 3 in low yield (<10%). Fortunately, when (4-amino-3-nitrophenyl)borate 4 was employed as the starting material, its cross-coupling with 2 followed by Fe-mediated reduction readily generated [1,1’-biaryl]-3,4-diamine 5 in 67% yield over two steps, which served as an important precursor for subsequent 11C-labeling. The cyclization of diamine 5 was achieved by reacting with 1,1’-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) to provide the desired candidate 3 in 90% yield. Another [1,1’-biaryl]-3,4-diamine 9 was also obtained in 46% yield via an analogous two-step sequence of palladium-catalyzed coupling of aryl boric acid 6 with 4-bromo-2-nitroaniline 7 followed by Fe-mediated reduction. However, further studies demonstrated that direct cross-coupling between aryl boric acid 6 and 4-bromobenzene-1,2-diamines 8. represented a more efficient and step-economical avenue, thus delivering [1,1’-biaryl]-3,4-diamines 9-16 in good to excellent yields (42–85%). Subsequent cyclization triggered by CDI smoothly occurred to give the urea-type AMPAR antagonists 17-24 in 52–82% yields. The carbamothioate-type AMPAR inhibitors 27-29 were obtained in 62–83% yields through protection of 6-bromobenzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-one 25 with Boc2O, followed by the cross-coupling reactions with aryl boric acid 6. It was worth noting that Boc-protected thialzolone intermediate 26 is critical for the high-yielding (62–83%) cross-coupling reactions with 6 since merely 5% yield was observed when using unprotected 25.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of TARP ɣ8-dependent AMPA antagonists. Conditions: (i) PdCl2(dtbpf), K3PO4, 1,4-dioxane/H2O, 100 oC, 2 h; <10% yield for 3; 53% yield for 9; 74% yield for 10; 86% yield for 11; 42% yield for 12; 46% yield for 13; 75% yield for 14; 66% yield for 15; 85% yield for 16; 62% yield for 27 over two steps; 83% yield for 28 over two steps; 78% yield for 29 over two steps; (ii) PdCl2(dppf), Na2CO3, 1,4-dioxane/H2O, 80 oC, 16 h; (iii) Fe, conc. HCl, EtOH/H2O, reflux for 2 h; 67% yield for 5 over two steps; 46% yield for 9 over two steps; (iv) CDI, THF, rt, 16h; 90% yield for 3; 68% yield for 17; 52% yield for 18; 64% yield for 19; 78% yield for 20; 67% yield for 21; 63% yield for 22; 63% yield for 23; 82% yield for 24; (v) (Boc)2O, NaH, DMF, rt, 2 h. dtbpf = 1,1′-bis(di-tert-butylphosphino)ferrocene; dppf = 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene; DMF = N,N-dimethylformamide; CDI = 1,1’-carbonyldiimidazole; (Boc)2O = di-tert-butyl dicarbonate.

Pharmacology.

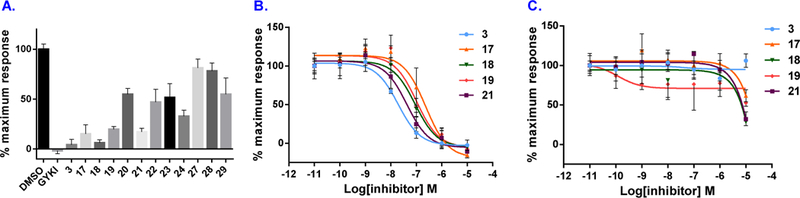

Compounds 3, 17-24 and 27-29 were subsequently screened for their in vitro potency and selectivity towards AMPARs associated with TARPγ−8. The results are shown in Figure 3. Since GluA1 subunit is one of the major AMPARs expressed in hippocampus, we utilized GluA1 as the principal AMPAR subunit in our in vitro pharmacological studies. The splice variant flop isoform of GluA1 was used in our assay due to its faster desensitization than the flip isoform and increased modulation by TARP. Specifically, an intracellular calcium flux system in human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells expressing AMPA receptor GluA1o fusion construct with TARPγ−8 or γ−2 was used to evaluate the ability of candidate compound to block glutamate-induced increases using fluorescence imaging plate reader (FLIPR)-based assays. With these in vitro assays in place, based on a preliminary screening of antagonists at a single concentration (300 nM), urea-type compounds 3, 17–19 and 21 demonstrated promising in vitro potency towards AMPARs associated with TARPγ−8 (as top 40% most potent compounds), while carbamothioate-type compounds 27-29 showed inferior potency towards TARP (Figure 3A). Subsequently, candidate compounds 3, 17–19 and 21 were determined as the IC50 values for inhibition of glutamate-evoked currents in HEK293 cells co-expressing GluA1 and TARPγ−8 via concentration-response curves. All these five candidates potentially blocked human GluA1 + TARPγ−8 with IC50 values as 19.5 nM for 3, 235.3 nM for 17, 90.9 nM for 18, 103.3 nM for 19, 42.6 nM for 21, respectively (Figure 3B). As proof of concept, we evaluated these five compounds 3, 17–19 and 21 in TARP sub-type selectivity. No significant inhibition of GluA1 with TARPγ−2 was observed up to a concentration of 1 µM (Figure 3C). Notably, no substantial off-target binding of 3 and 17 was identified in a panel of 52 receptors, ion channels and transporters, demonstrating greater than 100 fold selectivity against all tested targets. [35]

Figure 3.

Inhibition of TARPγ−8-dependent AMPAR activity by antagonists. GluA1 and TARPγ−8 were co-expressed in HEK293 cells and stimulated by glutamate and cyclothiazide. Maximal inhibition was defined by the noncompetitive AMPAR antagonist GYKI53655. A) Inhibition by 300 nM candidate compounds. B) Dose-response curves of 3, 17–19 and 21 for inhibition of AMPA TARPγ−8. IC50 values were 19.5 nM (3), 235.3 nM (17), 90.9 nM (18), 103.3 nM (19), and 42.6 nM (21). C) Dose-response curves of 3, 17–19 and 21 for inhibition of AMPA TARPγ−2.

Homology model and molecular docking studies.

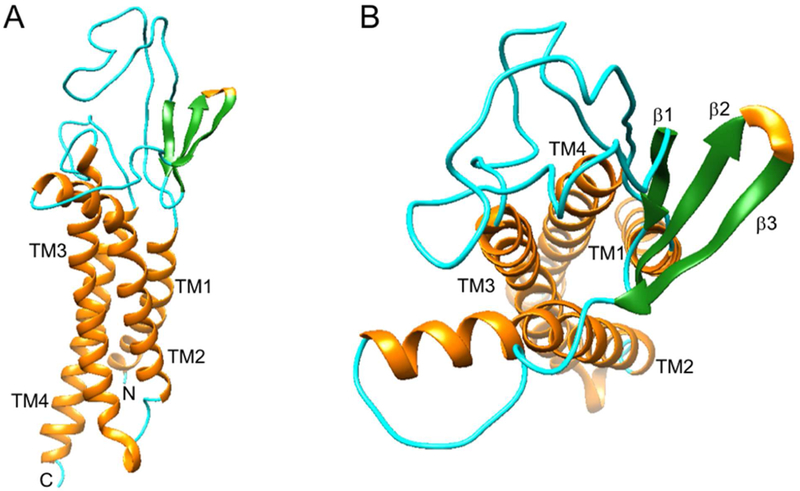

We investigated the molecular interactions of candidate antagonists with AMPA TARP γ−8 by molecular docking studies. The goal is to identify the possible key molecular interaction between TARP γ−8 antagonists and the binding domain based on the fact that nanomolar potency (19–235 nM) was determined from compounds 3, 17–19 and 21. Homology modeling-based server, SWISS-MODEL, was used to generate the three-dimensional structure of TARPγ−8, with the best hit, PDB ID 5KK2, chosen as the building template. 5KK2, a TARP γ−2, shares 48% sequence similarity with TARP γ−8 query sequence. [49] The built γ−8 model was uploaded to PDBsum and analyzed with PROCHECK program. All-residue Ramachandran plot showed that 81.9% of the residues fell into most favored regions and 17.5% of the residues fell into additional allowed regions (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Of note is the Asp110 residue, which appeared in the disallowed region, but its corresponding Phi-Psi torsion angle was edged to an additional allowed region. The overall G-factor average of the structure was −0.26, indicating good normality. Analyzing the secondary structures of the computed TARP γ −8 model, we found four major helices, which are bundled into a trans-membrane structure (Figure 4A) similar to the cryo-EM γ−2 structure, [50] two long loops and three beta strands between transmembrane helix 1 (TM1) and TM2, as well as one loop between TM3 and TM4 (Figure 4B). It is noteworthy that about 180 amino acids towards the TARP γ−8 C-terminus were not included in the computed model due to lacking the corresponding regions within the template; however, the missing C-terminal residues should be located within the cytoplasm, [50] thus unlikely influencing the subsequent ligand docking results.

Figure 4.

Homology model of TARP γ−8. (A) Viewed parallel to the membrane; (B) Viewed from the extracellular side of the membrane.

Candidate compounds, 3, 17–19 and 21 were docked onto the homology-computed AMPAR/TARPγ−8 structure using Autodock Vina in Chimera. [51] Based on the docking studies, a consensus binding pocket was found within the extracellular opening of the four helices bundle, which is adjacent to TM2, TM3 and the β3-TM2 loop (Figure 5A). For each compound, the docking pose with the highest docking score was chosen for subsequent analyses and comparison with our experimental data. Deep in the binding pocket, an angled π-π stacking interaction was found between γ−8 Phe107 side chain and the phenyl group of the compounds (Figure 5B). In addition, the trifluoromethoxy moiety of the compounds was found in proximity to the Lys103 side chain, indicating possible electrostatic interactions between the two. Furthermore, the side chain of Ser182 was approximately 3Å away from one of the secondaryamines of the compounds, suggesting the potential formation of a hydrogen bond.

Figure 5.

Interactions between TARP γ−8 and candidate compounds 3, 17–19 and 21. A) The overview of the docking pose of the candidate compounds 3, 17–19 and 21 onto TARP γ−8, and B) the zoom-in view of potential interacting residues of TARP γ−8 with the candidate compounds.

We note that Lys103 and Phe107 belong to a highly conserved sequence (KINHFPEDTDYDHD), which was previously found across all type TARPs, [52, 53] including γ−2, γ−3, γ−4 and γ−8. This conserved electronegative sequence was reported to be responsible for altering AMPAR gating and pharmacology. [52, 54–58] For instance, this motif within γ−2 interacts with subunits B and D of GluA2 AMPAR. [50] Interestingly, in our study, we found the above conserved sequence within the β3-TM2 loop of the predicted TARP γ−8 structure and located next to our proposed binding pocket. This allows two of the residues, Lys103 and Phe107, to interact with the candidate compounds. Therefore, we hypothesized that binding to the candidate compounds might cause some conformational changes of the TARP γ−8 β3-TM2 loop, and consequently, interfere with the interactions between AMPAR and γ−8.

Physicochemical property.

We use candidate compounds’ lipophilicity as one of the predictive factors for blood-brain barrier permeability with a favorable range between 1.0 and 3.5. [59–61] Using liquid-liquid partition between n-octanol and PBS (‘shake flask method’), [62] the logD values of 3, 17-19 and 21 were determined to be 2.13, 2.17, 2.67, 2.01 and 3.18, respectively (n = 3), indicating a high possibility of brain penetration (Table 1). We also utilized in silico prediction methods to determine the topological polar surface area (tPSA) and multiple parameter optimization (MPO) scores. The candidate compounds 3, 17-19 and 21 showed reasonable range in tPSA and MPO values as potential brain penetrant leads (Table 1). These results indicated the high possibility of sufficient brain permeability of compounds 3, 17-19 and 21. Together with binding potency, molecular docking and physicochemical properties, we chose AMPA antagonists 3, 17-19 and 21 for radiolabeling experiments.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of compounds 3, 17–19 and 21.

| Entry | 3 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LogDa | 2.13 ± 0.04 | 2.17 ± 0.07 | 2.67 ± 0.23 | 2.01 ± 0.20 | 3.18 ± 0.31 |

| tPSAb | 64.9 | 50.3 | 50.3 | 50.3 | 50.3 |

| MPOc | 5.2 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

Distribution coefficient (LogD) was measured by the ‘shake-flask’ method and quantified by LC-MS. The data are expressed in mean ± SD (n = 3)

topological polar surface area (tPSA) was calculated by ChemBioDraw Ultra 14.0

MPO score was calculated using the method reported in Zhang, L. et al. [63]

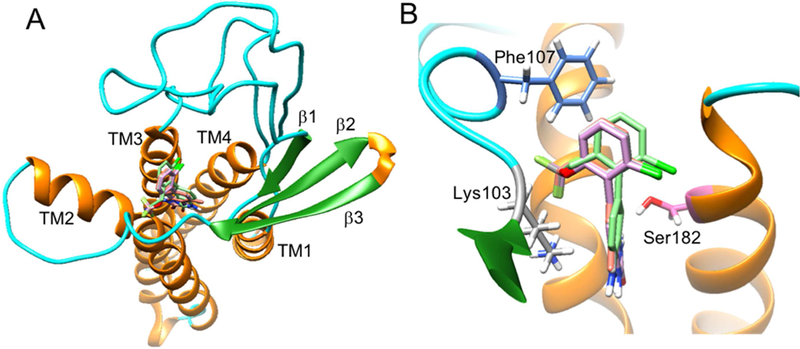

Radiochemistry.

The chemical scaffold of 1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ones offers a unique opportunity and unified labeling strategy using 11C-carbonylation methodology. [64] Dolle and Kassiou et al. have demonstrated the use of [11C]COCl2 (generated from [11C]CO2) to radiolabel the carbonyl position of chemical structures including 1,3-dihydrobenzoimidazol-2-one[65] and 3H-benzoxazol-2-one, [66] respectively. Thus we adopted their methodology to carry out radiosynthesis of 30–33 from the corresponding precursors 9, 5, 13 and 10, respectively. The [1,1’-biaryl]-3,4-diamines 5, 9-10 and 13 for 11C-carbonylation were synthesized by the method outlined in Scheme 2. The radiosynthesis of 30 ([11C]17) was performed using [11C]COCl2 generated from our modified procedure[67] (Scheme 2A). Specifically, the reaction of [11C]COCl2 with benzenediamine 9 generated 11C-labeled cyclic urea 17 in the presence of triethylamine (Et3N) in THF. The reaction mixture was purified by a reverse phase semi-preparative HPLC, and reformulated for imaging study. 30 was synthesized in an average of 28% decay-corrected radiochemical yield (RCY) based on starting [11C]CO2 at end-of-synthesis with >99% radiochemical purity (n = 2) . The molar activity was greater than 35 GBq/µmol (0.95 Ci/µmol ). In an analogous fashion, 31 ([ 11C]3, Scheme 2B) and 32 ([11C]21, Scheme 2C) were radiolabeled with [11C]COCl2 in a range of 19–31% RCY (decay corrected) with high radiochemical purity (>99%) and high molar activity (Am >80 GBq/µmol, n = 2). It is also our interest to evaluate brain permeability of 33 ([11C] 18), which was synthesized from [11C]COCl2 in 13% decay-corrected RCY based on starting [11C]CO2 at end-of-synthesi with >99% radiochemical purity (n = 1). In summary, all these radioligands showed no signs of radiolysis up to 90 min after formulation. The efficient radiosynthesis with high radiochemical purity and molar activities of 30-33 enabled the subsequent in vitro and in vivo evaluation.

Scheme 2.

Radiolabeling of tracers 30–33. Conditions: [11C]COCl2, Et3N, THF; 30 oC, 1 min.

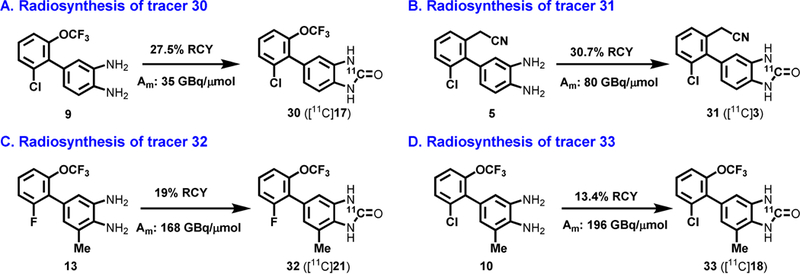

Preliminary PET imaging studies in rat brain.

Dynamic PET acquisitions were carried out with 30-33 in Sprague-Dawley rats for 60 mins. Representative PET images of 32 (sagittal and coronal, summed images 0–60 min) and time-activity curves of two characteristic brain regions, namely TARP γ−8 enriched hippocampus and TARP γ−8 deficient cerebellum, are shown in Figure 6. Time-activity curves of 30, 32, 33 in the whole brain are shown in Figure S2, Supporting Information. Compounds 30, 32 and 33 all demonstrated reasonable blood-brain-barrier (BBB) penetration ability with maximum standard uptake value (SUV) of ca. 1.0, 0.8 and 0.8 in the whole brain, respectively. The regional distribution of 32 was heterogeneous with high uptake observed in the hippocampus and low uptake in the cerebellum (Figures 6A and 6B), consistent with TARP γ −8 expression in the rodent brain. [68] 30 also showed similar distribution pattern as shown in Figure 6C. However, pretreatment of 32 with unlabeled 21 (1 mg/kg) or 30 with JNJ5551118 (1 mg/kg) failed to show significant reduction of brain uptake, probably attributed to in vivo nonspecific binding (Figure S2). Compound 31 showed limited whole brain uptake (ca. 0.2 SUV), which might cause no significant changes between baseline and blocking conditions (JNJ56022486, 1mg/kg, Figures 6D and 6E).

Figure 6.

Representative PET images and time-activity curves of 30–32 in rat brain: (A) baseline PET images (summed 0–60 min) of 32; (B and C) time-activity curve of 32 and 30 under baseline in the region of hippocampus (high expression) and cerebellum (low expression); (D) baseline PET images (summed 0–60 min) of 31 and (E) whole brain time-activity curve of 31 under baseline and blocking conditions (1 mg/kg, JNJ56022486).

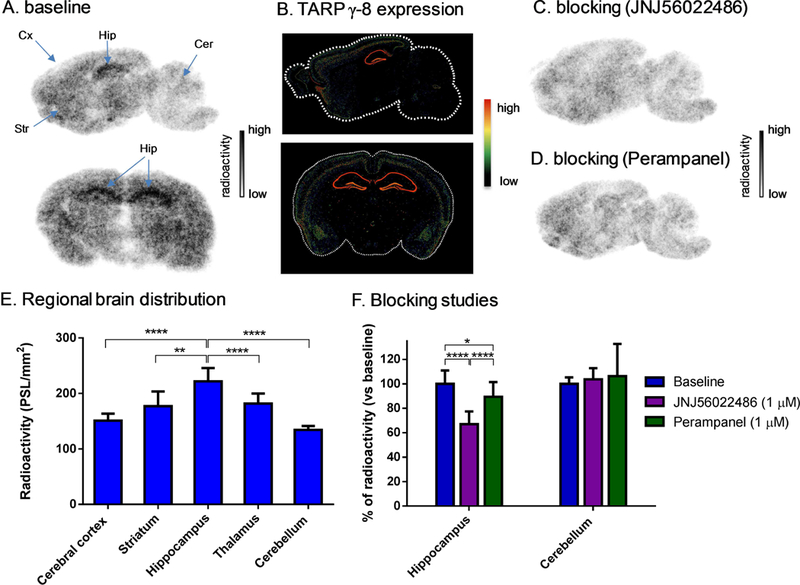

In vitro Autoradiography

Since structural scaffolds bearing 30 and 32 showed a high level of nonspecific binding in vivo, we shifted our focus into a structurally diverse molecule 31. The in vitro binding specificity of 31 was evaluated by in vitro autoradiography studies. Representative in vitro autoradiograms of 31 on sagittal and coronal sections of rat brains are shown in Figure 7A. The baseline study demonstrated the heterogeneous distribution of bound radioactivity with signal levels from high to low in the order of hippocampus, striatum, thalamus, cerebral cortex and cerebellum (Figures 7A and 7D). The distribution pattern was consistent with the mRNA expression pattern of TARPγ−8 with the highest signal level in the region of the hippocampus and the lowest level in the cerebellum (Figure 7B). Blocking studies with JNJ56022486 (1 µM) resulted in greater than 30% reduction of the bound radioactivity in hippocampus and abolishment of the heterogeneity in different brain regions. No notable change was observed for the reference region, i.e., the cerebellum (Figures 7C and 7E). These results indicate that 31 has a reasonable medium-to-good level of in vitro specific binding to AMPARs complexed with TARPγ−8.

Figure 7.

Ex vivo biodistribution in mice at four different time points (5, 15, 30 and 60 min) post injection of 31. All data are mean ± SD, n = 4. Asterisks indicate statistical significance. * p < 0.05, and ** p ≤ 0.01.

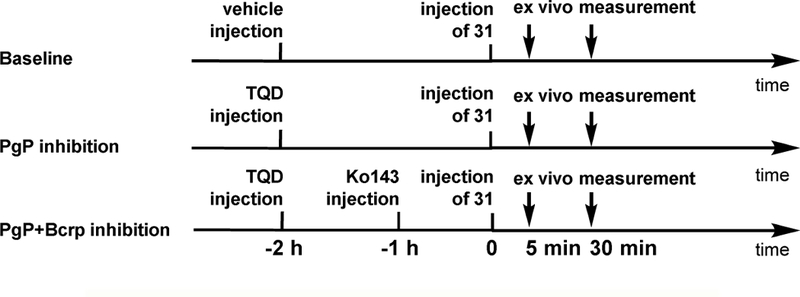

Efflux transporter inhibition experiments.

Since 31 showed promising in vitro binding specificity towards TARPγ−8 dependent AMPARs, we next investigated the underlying cause of low brain uptake. Recent studies demonstrated that both P-glycoprotein (Pgp) and breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp) are essential members of the ABC transporter family, which co-localize at the BBB. [69] Many drug molecules, which are substrates of Pgp and/or Bcrp, are promptly excreted back into the blood from the brain and thus exhibit limited brain uptake. To determine whether the low uptake is attributed to the excretion from the brain by the Pgp and/or Bcrp, we performed ex vivo measurement of 31 brain uptake under the administration of tariquidar (TQD), a Pgp inhibitor, and/or Ko143, a Bcrp inhibitor. [70] TQD (8 mg/kg) or the combination of TQD (8 mg/kg) and Ko143 (15 mg/kg) was administrated intravenously via tail vein 2 h (for TQD) or 1 h (for Ko143) before injection of 31 (Scheme 3). The brain uptake was measured at 5 min and 30 min post -injection under control and PgP/Bcrp inhibition conditions. As depicted in Table 1, TQD pretreatment increased the brain uptake to 146% and 204% at 5 min and 30 min post-injection, respectively. The more profound effect was observed when PgP/Bcrp were simultaneously inhibited by TQD and Ko143, which showed 186% and 282% increased brain uptake. The brain-to-blood ratio also increased significantly under Pgp (177% and 206% at 5 and 30 min post injection, respectively) and Pgp/Bcrp (202% and 233% at 5 and 30 min post injection, respectively) inhibition conditions, the trend of which was consistent with the observations in the brain uptake (Table 2). These findings demonstrated that 31 had intensive interactions with brain efflux pumps including Pgp and Bcrp at the BBB, which may, in part, account for the low brain accumulation of 31 at tracer dose.

Scheme 3.

brain efflux transporter inhibition experiments

Table 2.

Effect of tariquidar (TQD) and Ko143 on brain uptake of 31 and brain-to-blood ratio in mice.

| (A) brain uptake under baseline and PgP inhibition conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Brain uptake (%ID/g)a |

%increase under Pgp inhibition |

%increase under Pgp/Bcrp inhibition |

||

| control | TQDb | TQD+ko143b,c | |||

| 5mind | 0.50 ± 0.10 | 0.73 ± 0.12 | 0.93 ± 0.18 | 146±23* | 186 ± 36** |

| 30 mine | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 1.46 ± 0.19 | 2.02 ± 0.51 | 204 ± 27**** | 282 ± 73** |

| (B) brain-to-blood ratio under baseline and PgP inhibition conditions | |||||

| Time | Brain uptake (%ID/g)a |

%increase under Pgp inhibition |

%increase under Pgp/Bcrp inhibition |

||

| control | TQDb | TQD+ko143b,c | |||

| 5mind | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 177 ± 26** | 202 ± 27** |

| 30 mine | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.72 ± 0.43 | 0.83 ± 0.12 | 206 ± 110* | 233 ± 34*** |

p < 0.05 vs control.

p < 0.01 vs control.

p < 0.0004 vs control.

p < 0.0001 vs control.

The data are expressed in mean ± SD (n = 3–4).

TQD (8 mg/kg) was intravenously injected into mice 2 h before tracer injection.

Ko143 (15 mg/kg) was intravenously injected into mice 1 h before tracer injection.

Tracer uptake was expressed as %ID/g 5 min post-injection of 31.

Tracer uptake was expressed as %ID/g 30 min post-injection of 31. Asterisks indicate statistical significance.

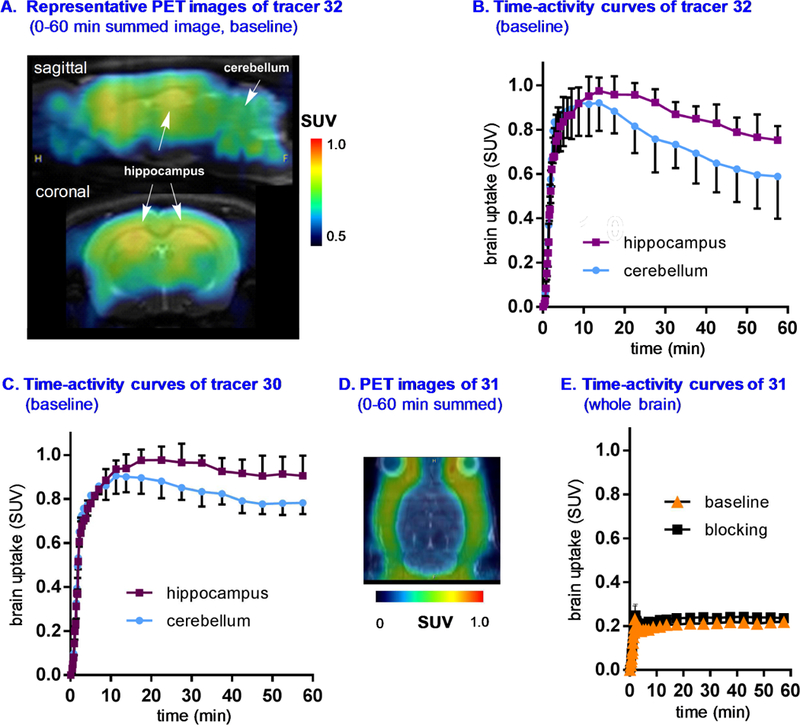

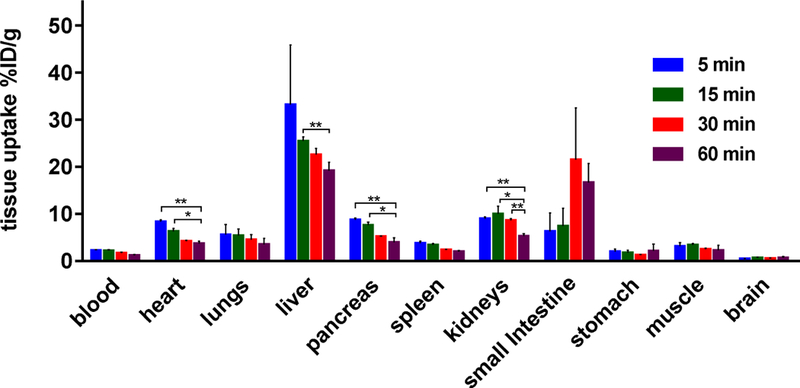

Whole body ex vivo biodistribution studies and radiometabolite analysis.

The uptake, biodistribution and clearance of 31 were investigated in mice at four time points (5, 15, 30 and 60 min) after i.v. injection of the radiotracer (Figure 8 and Table S1, Supporting Information). Several organs including heart, lungs, pancreas, small intestine, kidneys and liver exhibited high uptake (>5% ID/g) at 5 min post-injection. After the initial uptake, the radioactivity in heart, lungs, pancreas and liver decreased rapidly, while that in small intestine and kidney started to decrease at 15 and 30 min post-injection, respectively. These results together with high radioactivity remaining in liver, kidneys and small intestine at 60 min post-injection demonstrated the rapid hepatobiliary elimination of 31, and concurrently relatively-slow urinary elimination. To evaluate the stability of 31 in vivo, radiometabolites in the plasma and brain homogenate in mice were evaluated at 30 min post-injection of the radiotracer. The fraction of unchanged 31 in brain and plasma was determined to be 65% and 35%, respectively, and SMARTCyp [71] was utilized to propose three possible sites for the metabolism (Table S2 in the supporting information). These results indicated that 31 showed reasonable stability in the brain and relatively rapid metabolism in the plasma.

Figure 8.

Ex vivo biodistribution in mice at four different time points (5, 15, 30 and 60 min) post injection of 31. All data are mean ± SD, n = 4. Asterisks indicate statistical significance. * p < 0.05, and ** p ≤ 0.01.

CONCLUSION

We have efficiently synthesized a focused library of AMPAR/TARPγ−8 antagonists containing 1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ones and benzo[d]thiazol-2(3H)-ones. IC50 values towards TARP γ−8 and subtype-selectivity between TARPγ−2 and TARPγ−8 were determined in vitro by calcium flux assay on human HEK-293 cells expressing AMPA GluA1 + TARPγ−8. Physiochemical properties including distribution coefficient (LogD), and in silico MPO and tPSA values were also measured. As a result, compounds 3, 17–19 and 21 were identified as promising candidates for the PET tracer development. 11C-Carbonylation labeling strategy using [11C]COCl2 was employed to provide [11C-carbonyl]labeled TARP γ−8 dependent AMPAR antagonists in high radiochemical yield (13–31%), high molar activity (35–196 GBq/µmol) and high radiochemical purity (>99%). The pharmacokinetic profile including brain uptake, clearance and binding specificity of compounds 30–32 was evaluated by PET. While trifluoromethoxy substituted tracers 30 and 32 showed heterogenous regional brain uptake, which was consistent with TARP γ−8 distribution, further investigation was not pursued due to high nonspecific binding evidenced in the blocking experiment. To our delight, despite low brain uptake in PET experiments, a structurally diverse tracer 31 demonstrated good in vitro specific binding and heterogeneous regional brain uptake, which was aligned with TARP γ−8 distribution. We also carried out efflux transporter inhibition experiments to confirm the underlying reason for low brain uptake of 31, which was, to a large extent, attributed to the PgP/Bcrp efflux mechanism. Further optimization to improve the brain uptake and minimize the intensive interaction with PgP/Bcrp is needed. As a result, this work not only represents the first medicinal chemistry approach towards subtype selective AMPA PET tracers, but also offers a new roadmap towards next generation AMPA tracers by utilizing the knowledge of pharmacology, molecular docking, physiochemical properties as well as radiochemistry presented in this work.

Supplementary Material

Highlight:

Synthesis, pharmacology and docking evaluation of AMPAR/TARP γ−8 antagonists.

All lead compounds labeled with [11C]COCl2 in high radiochemical yields and high molar activities

The first AMPAR/TARP γ−8 PET tracer with good in vitro specific binding and characteristic high uptake in the hippocampus in rat brain tissues

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Lei Zhang (Medicine Design, Pfizer, Inc) and Professor Thomas J. Brady (Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, Radiology, MGH and Harvard Medical School) for helpful discussion. Financial support from the NIH grants (DA038000, DA043507, MH117125 to S.L., R01AG054473 to N.V., R01MH077939 to S.T.), CSC scholarship to Z. C. (Grant No. 201606250107), NSFC (Grant No. 21772142) and the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, 2014CB745100) to J.A.M. is gratefully acknowledged.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PET

positron emission tomography

- AMPA a

amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- TARP

transmembrane AMPAR regulatory protein

- SUV

standardized uptake value

- TAC

time-activity curve

- %ID/g

the percentage of injected dose per gram of wet tissue

- PgP

P-glycoprotein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

This information is included in the supplementary material.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Characterization of all new compounds and NMR spectra; assay methods; supplemental figures and tables. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Meldrum BS, Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology, J. Nutr, 130 (2000) 1007S–1015S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Watkins JC, Jane DE, The glutamate story, Br. J. Pharmacol, 147 (2006) S100–S108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF, The glutamate receptor ion channels, Pharmacol. Rev, 51 (1999) 7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mayer ML, Armstrong N, Structure and function of glutamate receptor ion channels, Annu. Rev. Physiol, 66 (2004) 161–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ, Menniti FS, Vance KM, Ogden KK, Hansen KB, Yuan HJ, Myers SJ, Dingledine R, Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function, Pharmacol. Rev, 62 (2010) 405–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hollmann M, Heinemann S, Cloned glutamate receptors, Annu. Rev. Neurosci , 17 (1994) 31–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Compans B, Choquet D, Hosy E, Review on the role of AMPA receptor nanoorganization and dynamic in the properties of synaptic transmission Neurophotonics, 3 (2016) 041811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Calabresi P, Cupini LM, Centonze D, Pisani F, Bernardi G, Antiepileptic drugs as a possible neuroprotective strategy in brain ischemia, Ann. Neurol, 53 (2003) 693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chang PK, Verbich D, McKinney RA, AMPA receptors as drug targets in neurological disease-advantages, caveats, and future outlook, Eur. J. Neurosci, 35 (2012) 1908–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Turski L, Huth A, Sheardown M, McDonald F, Neuhaus R, Schneider HH, Dirnagl U, Wiegand F, Jacobsen P, Ottow E, ZK200775: a phosphonate quinoxalinedione AMPA antagonist for neuroprotection in stroke and trauma, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 95 (1998) 10960–10965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ornstein PL, Arnold MB, Augenstein NK, Lodge D, Leander JD, Schoepp DD, (3SR,4aRS,6RS,8aRS)-6-[2-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)ethyl]decahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid: a structurally novel, systemically active, competitive AMPA receptor antagonist., J. Med. Chem, 36 (1993) 2046–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gilron I, Max MB, Lee G, Booher SL, Sang CN, Chappell AS, Dionne RA, Effects of the 2-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-proprionic acid/kainate antagonist LY293558 on spontaneous and evoked postoperative pain, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther, 68 (2000) 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Faught E, BGG492 (selurampanel), an AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist drug for epilepsy, Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs, 23 (2014) 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chappell AS, Sander JW, Brodie MJ, Chadwick D, Lledo A, Zhang D, Bjerke J, Kiesler GM, Arroyo S, A crossover, add-on trial of talampanel in patients with refractory partial seizures, Neurology, 58 (2002) 1680–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Feigin V, Irampanel boehringer ingelheim, Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs, 3 (2002) 908–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].French JA, Krauss GL, Steinhoff BJ, Squillacote D, Yang H, Kumar D, Laurenza A, Evaluation of adjunctive perampanel in patients with refractory partial-onset seizures: results of randomized global phase III study 305, Epilepsia, 54 (2013) 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zwart R, Sher E, Ping X, Jin X, Sims JR, Chappell AS, Gleason SD, Hahn PJ, Gardinier K, Gernert DL, Hobbs J, Smith JL, Valli SN, Witkin JM, Perampanel, an antagonist of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors, for the treatment of epilepsy: studies in human epileptic brain and nonepileptic brain and in rodent models, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther, 351 (2014) 124–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ko D, Yang H, Williams B, Xing D, Laurenza A, Perampanel in the treatment of partial seizures: Time to onset and duration of most common adverse events from pooled Phase III and extension studies, Epilepsy Behav, 48 (2015) 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Letts VA, Felix R, Biddlecome GH, Arikkath J, Mahaffey CL, Valenzuela A, Bartlett FS, Mori Y, Campbell KP, Frankel WN, The mouse stargazer gene encodes a neuronal Ca2+-channel gamma subunit, Nat. Genet, 19 (1998) 340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Burgess DL, Davis CF, Gefrides LA, Noebels JL, Identification of three novel Ca2+ channel gamma subunit genes reveals molecular diversification by tandem and chromosome duplication., Genome Res, 9 (1999) 1204–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Klugbauer N, Dai S, Specht V, Lacinová L,Marais E, Bohn G, Hofmann F, A family of gamma-like calcium channel subunits, FEBS Lett, 470 (2000) 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shaw AS, Filbert EL, Scaffold proteins and immune-cell signalling, Nat. Rev. Immunol, 9 (2009) 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yan D, Tomita S, Defined criteria for auxiliary subunits of glutamate receptors, J. Physiol , 590 (2012) 21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jackson AC, Nicoll RA, The expanding social network of ionotropic glutamate receptors: TARPs and other transmembrane auxiliary subunits, Neuron, 70 (2011) 178–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hashimoto K, Fukaya M, Qiao X, Sakimura K, Watanabe M, Kano M, Impairment of AMPA receptor function in cerebellar granule cells of ataxic mutant mouse stargazer, J. Neurosci, 19 (1999) 6027–6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tomita S, Regulation of ionotropic glutamate receptors by their auxiliary subunits, Physiology, 25 (2010) 41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jackson AC, Nicoll RA, The expanding social network of ionotropic glutamate receptors: TARPs and other transmembrane auxiliary subunits, Neuron, 70 (2011) 178–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tomita S, Chen L, Kawasaki Y, Petralia RS, Wenthold RJ, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS,Functional studies and distribution define a family of transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory proteins, J. Cell Biol, 161 (2003) 805–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fukaya M, Yamazaki M, Sakimura K, Watanabe M, Spatial diversity in gene expression for VDCCγ subunit family in developing and adult mouse brains, Neurosci. Res, 53 (2005) 376–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gill MB, Bredt DS, An emerging role for TARPs in neuropsychiatric disorders, Neuropsychopharmacology, 36 (2011) 362–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rouach N, Byrd K, Petralia RS, Elias GM, Adesnik H, Tomita S, Karimzadegan S, Kealey C, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA, TARP γ−8 controls hippocampal AMPA receptor number, distribution and synaptic plasticity., Nat. Neurosci, 8 (2005) 1525–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fukaya M, Tsujita M, Yamazaki M, Kushiya E, Abe M, Akashi K, Natsume R, Kano M, Kamiya H, Watanabe M, Sakimura K, Abundant distribution of TARP γ−8 in synaptic and extrasynaptic surface of hippocampal neurons and its major role in AMPA receptor expression on spines and dendrites, Eur. J. Neurosci, 24 (2006) 2177–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gleason SD, Kato A, Bui HH, Thompson LK, Valli SN, Stutz PV, Kuo M-S, Falcone JF, Anderson WH, Li X, Witkin JM, Inquiries into the biological significance of transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory protein (TARP) γ−8 through investigations of TARP γ−8 Null Mice, CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets, 14 (2015) 612–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yamasaki M, Fukaya M, Yamazaki M, Azechi H, Natsume R, Abe M, Sakimura K, Watanabe X, TARP γ−2 and γ−8 differentially control AMPAR density across schaffer collateral/commissural synapses in the hippocampal CA1 area, J. Neurosci, 36 (2016) 4296–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Maher MP, Wu N, Ravula S, Ameriks MK, Savall BM, Liu C, Lord B, Wyatt RM, Matta JA, Dugovic C, Yun S, Donck LV, Steckler T, Wickenden AD, Carruthers NI, Lovenberg TW, Discovery and characterization of AMPA receptor modulators selective for TARP-γ8, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther, 357 (2016) 394–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gardinier KM, Gernert DL, Porter WJ, Reel JK, Ornstein PL, Spinazze P, Stevens FC, Hahn P, Hollinshead SP, Mayhugh D, Schkeryantz J, Khilevich A, Frutos OD, Gleason SD, Kato AS, Luffer-Atlas D, Desai PV, Swanson S, Burris KD, Ding C, Heinz BA, Need AB, Barth VN, Stephenson GA, Diseroad BA, Woods TA, Y H, Bredt D, Witkin JM, Discovery of the first α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor antagonist dependent upon transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory protein (TARP) γ−8, J. Med. Chem, 59 (2016) 4753–4768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lee MR, Gardinier KM, Gernert DL, Schober DA, Wright RA, Wang H, Qian Y, Witkin JM, Nisenbaum ES, Kato AS, Structural determinants of the γ−8 TARP dependent AMPA receptor antagonist, ACS Chem. Neurosci, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Witkin JM, Li J, Gilmour G, Mitchell SN, Carter G, Gleason SD, Seidel WF, Eastwood BJ, McCarthy A, Porter WJ, Reel J, Gardinier KM, Kato AS, Wafford KA, Electroencephalographic, cognitive, and neurochemical effects of LY3130481 (CERC-611), a selective antagonist of TARP-γ8-associated AMPA receptors, Neuropharmacology, 126 (2017) 257–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Phelps ME, Positron emission tomography provides molecular imaging of biological processes, Proc Natl Acad Sci, 97 (2000) 9226–9233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee CM, Farde L, Using positron emission tomography to facilitate CNS drug development, Trends Pharmacol. Sci, 27 (2006) 310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Willmann JK, Bruggen N.v., Dinkelborg LM, Gambhir SS, Molecular imaging in drug development, Nat Rev Drug Discov, 7 (2008) 591–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gao M, Kong D, Clearfield A, Zheng Q-H, Synthesis of carbon-11 and fluorine-18 labeled N-acetyl-1-aryl-6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives as new potential PET AMPA receptor ligands, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 16 (2006) 2229–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Årstad E, Gitto R, Chimirri A, Caruso R, Constanti A, Turton D, Hume SP, Ahmad R, Pilowskyd LS, Luthra SK, Closing in on the AMPA receptor: synthesis and evaluation of 2-acetyl-1-(40-chlorophenyl)-6-methoxy-7-[11C]methoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline as a potential PET tracer, Bioorg. Med. Chem, 14 (2006) 4712–4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kronenberg UB, Drewes B, Sihver W, Coenen HH, N-2-(4-N-(4-[18F]Fluorobenzamido)phenyl)-propyl-2-propanesulphonamide: synthesis and radiofluorination of a putative AMPA receptor ligand, J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm, 50 (2007) 1169–1175. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lee HG, Milner PJ, Placzek MS, Buchwald SL, Hooker JM, Virtually instantaneous, room-temperature [11C]-cyanation using biaryl phosphine Pd(0) complexes, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 137 (2015) 648–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Oi N, Tokunaga M, Suzuki M, Nagai Y, Nakatani Y, Yamamoto N, Maeda J, Minamimoto T, Zhang M-R, Suhara T, Higuchi M, Development of novel PET probes for central 2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolyl)propionic acid receptors, J. Med. Chem, 58 (2015) 8444–8462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Takahata K, Kimura Y, Seki C, Tokunaga M, Ichise M, Kawamura K, Ono M, Kitamura S, Kubota M, Moriguchi S, Ishii T, Takado Y, Niwa F, Endo H, Nagashima T, Ikoma Y, Zhang M-R, Suhara T, Higuchi M, A human PET study of [11C]HMS011, a potential radioligand for AMPA receptors, EJNMMI Res, 7 (2017) 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yuan G, Jones GB, Vasdev N, Liang SH, Radiosynthesis and preliminary PET evaluation of 18F-labeled 2-(1-(3-fluorophenyl)-2-oxo-5-(pyrimidin-2-yl)-1,2-dihydropyridin-3-yl) benzonitrile for imaging AMPA receptors, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 26 (2016) 4857–4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zhao Y, Chen S, Yoshioka C, Baconguis I, Gouaux E, Architecture of fully occupied GluA2 AMPA receptor-TARP complex elucidated by cryo-EM, Nature, 536 (2016) 108–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Twomey EC, Yelshanskaya MV, Grassucci RA, Frank J, Sobolevsky AI, Elucidation of AMPA receptor-stargazin complexes by cryo-electron microscopy, Science, 353 (2016) 83–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Trott O, Olson AJ, AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading, J. Comput. Chem, 31 (2010) 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kato AS, Gill MB, Yu H, Nisenbaum ES, Bredt DS, TARPs differentially decorate AMPA receptors to specify neuropharmacology, Trends in Neurosciences, 33 (2010) 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Chu PJ, Robertson HM, Best PM, Calcium channel gamma subunits provide insights into the evolution of this gene family, Gene, 280 (2001) 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kato AS, Siuda ER, Nisenbaum ES, Bredt DS, AMPA receptor subunit-specific regulation by a distinct family of type II TARPs, Neuron, 59 (2008) 986–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Tomita S, Adesnik H, Sekiguchi M, Zhang W, Wada K, Howe JR, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS, Stargazin modulates AMPA receptor gating and trafficking by distinct domains, Nature, 435 (2005) 1052–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Riva I, Eibl C, Volkmer R, Carbone AL, Plested AJ, Control of AMPA receptor activity by the extracellular loops of auxiliary proteins, eLife, 6 (2017) e28680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Chen S, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Shekhar M, Tajkhorshid E, Gouaux E, Activation and desensitization mechanism of AMPA receptor-TARP complex by cryo-EM, Cell, 170 (2017) 1234–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Tomita S, Shenoy A, Fukata Y, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS, Stargazin interacts functionally with the AMPA receptor glutamate-binding module, Neuropharmacology, 52 (2007) 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Waterhouse RN, Determination of lipophilicity and its use as a predictor of blood-brain barrier penetration of molecular imaging agents, Mol. Imaging Biol, 5 (2003) 376–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Patel S, Gibson R, In vivo site-directed radiotracers: a mini-review, Nucl. Med. Biol, 35 (2008) 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Pike VW, Considerations in the Development of Reversibly Binding PET Radioligands for Brain Imaging, Curr. Med. Chem, 23 (2016) 1818–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].OECD, Test No. 107: Partition Coefficient (n-octanol/water): Shake Flask Method, OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zhang L, Villalobos A, Beck EM, Bocan T, Chappie TA, Chen L, Grimwood S, Heck SD, Helal CJ, Hou X, Humphrey JM, Lu J, Skaddan MB, McCarthy TJ, Verhoest PR, Wager TT, Zasadny K, Design and selection parameters to accelerate the discovery of novel central nervous system positron emission tomography (PET) ligands and their application in the development of a novel phosphodiesterase 2A PET ligand, J. Med. Chem, 56 (2013) 4568–4579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Rotstein BH, Liang SH, Placzek MS, Hooker JM, Gee AD, Dolle F, Wilson AA, Vasdev N, 11C=O bonds made easily for positron emission tomography radiopharmaceuticals, Chem. Soc. Rev, 45 (2016) 4708–4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Roger G, Lagnel B, Besret L, Bramoulle Y, Coulon C, Ottaviani M, Kassiou M, Bottlaender M, Valette H, Dolle F, Synthesis, radiosynthesis and in vivo evaluation of 5-[3-(4-benzylpiperidin-1-yl)prop-1-ynyl]-1,3-dihydrobenzoimidazol-2 -[(11)C]one, as a potent NR(1A)/2B subtype selective NMDA PET radiotracer, Bioorg. Med. Chem, 11 (2003) 5401–5408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Roger G, Dolle F, De Bruin B, Liu X, Besret L, Bramoulle Y, Coulon C, Ottaviani M, Bottlaender M, Valette H, Kassiou M, Radiosynthesis and pharmacological evaluation of [11C]EMD-95885: a high affinity ligand for NR2B-containing NMDA receptors, Bioorg. Med. Chem, 12 (2004) 3229–3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Wang L, Mori W, Cheng R, Yui J, Hatori A, Ma L, Zhang Y, Rotstein BH, Fujinaga M, Shimoda Y, Yamasaki T, Xie L, Nagai Y, Minamimoto T, Higuchi M, Vasdev N, Zhang M-R, Liang SH, Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of sulfonamido-based [11C-Carbonyl]-carbamates and ureas for imaging monoacylglycerol lipase, Theranostics, 6 (2016) 1145–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lee MR, Gardinier KM, Gernert DL, Schober DA, Wright RA, Wang H, Qian Y, Witkin JM, Nisenbaum ES, Kato AS, Structural determinants of the gamma-8 TARP dependent AMPA receptor antagonist, ACS Chem. Neurosci, 8 (2017) 2631–2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Tatsuta T, Naito M, Oh-hara T, Sugawara I, Tsuruo T, Functional involvement of P-glycoprotein in blood-brain barrier, J. Biol. Chem , 267 (1992) 20383–20391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wanek T, Kuntner C, Bankstahl JP, Mairinger S, Bankstahl M, Stanek J, Sauberer M, Filip T, Erker T, Muller M, Loscher W, Langer O, A novel PET protocol for visualization of breast cancer resistance protein function at the blood-brain barrier, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab, 32 (2012) 2002–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Rydberg P, Gloriam DE, Zaretzki J, Breneman C, Olsen L, SMARTCyp: A 2D Method for Prediction of Cytochrome P450-Mediated Drug Metabolism, ACS Med. Chem. Lett, 1 (2010) 96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.