Abstract

Background

In patients with septic shock, the presence of an elevated heart rate (HR) after fluid resuscitation marks a subgroup of patients with a particularly poor prognosis. Several studies have shown that HR control in this population is safe and can potentially improve outcomes. However, all were conducted in a single-center setting. The aim of this multicenter study is to demonstrate that administration of the highly beta1-selective and ultrashort-acting beta blocker landiolol in patients with septic shock and persistent tachycardia (HR ≥ 95 beats per minute [bpm]) is effective in reducing and maintaining HR without increasing vasopressor requirements.

Methods

A phase IV, multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, controlled study is being conducted. The study will enroll a total of 200 patients with septic shock as defined by The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock criteria and tachycardia (HR ≥ 95 bpm) despite a hemodynamic optimization period of 24–36 h. Patients are randomized (1:1) to receive either standard treatment (according to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines 2016) and continuous landiolol infusion to reach a target HR of 80–94 bpm or standard treatment alone. The primary endpoint is HR response (HR 80–94 bpm), the maintenance thereof, and the absence of increased vasopressor requirements during the first 24 h after initiating treatment.

Discussion

Despite recent studies, the role of beta blockers in the treatment of patients with septic shock remains unclear. This study will investigate whether HR control using landiolol is safe, feasible, and effective, and further enhance the understanding of beta blockade in patients with septic shock.

Trial registration

EU Clinical Trials Register; EudraCT, 2017-002138-22. Registered on 8 August 2017.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13063-018-3024-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Septic shock, Sepsis, Beta-blocker, Landiolol, Tachycardia, Randomized controlled trial

Background

In the early phase of septic shock, overwhelming inflammation leads to vasodilation and capillary leakage, which decreases cardiac output due to both absolute and relative hypovolemia [1–3]. These alterations trigger massive sympathetic activation in the attempt to maintain vital organ perfusion. Tachycardia and vasoconstriction are the hallmarks of this activation and compensate for systemic vasodilatation [4]. In the very early phase of the septic insult, tachycardia is the main compensatory mechanism to maintain cardiac output despite the reduction of preload. Accordingly, current sepsis guidelines recommend intravascular fluid administration as the first step to counteract hypotension [4]. Compensatory tachycardia implies preserved baroreceptor and chemoreceptor activity, thus the majority of patients with sepsis rapidly respond to volume administration with a reduction of tachycardia.

However, some patients with sepsis continue to have an elevated heart rate (HR) despite adequate fluid resuscitation. This elevated HR reflects sympathetic overstimulation resulting from dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system [5–12] in addition to the effect of exogenous catecholamines [7].

Elevated HR has been associated with a poor outcome, but it is unclear whether it is a surrogate of disease severity or whether it plays a pathophysiological role that could be treated to improve patient outcomes [13–16].

Beta-blockers are potential candidates to control HR and numerous animal models provide a rationale for their use during sepsis [17–24]. Despite concerns of hemodynamic decompensation, recent clinical studies using esmolol in patients with sepsis [10, 25–34] suggest that control of HR can be safely achieved with beta1-selective beta-blockers. These studies reported a decrease in HR with limited reduction of cardiac output, improved stroke volume and lactate levels, and stabilization or improvement of organ dysfunction [10, 28–30, 32]. Furthermore, the combined use of beta-blockers and vasopressors appears to be safe and does not appear to increase the need for vasopressor support or impair microcirculation [26, 27, 34]. However, all of the previously reported studies were conducted in single centers with relatively small sample sizes and only one study included a Caucasian population.

Landiolol, the beta-blocker used in our study, is a highly beta1-selective, ultrashort-acting beta-blocker that could be ideally suited for the treatment of critically ill patients due to its limited hypotensive effect [35–38].

The aim of this multicenter, prospective, controlled study is to demonstrate that the administration of the ultrashort-acting beta-blocker landiolol in patients with septic shock and persistent tachycardia (HR ≥ 95 beats per minutes [bpm]) is effective in reducing and maintaining HR without increasing vasopressor requirements.

Methods/Design

Study design and objective

This is a phase IV, multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, controlled study on landiolol in a septic shock population (as defined by The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock criteria [39]) hospitalized in an intensive care unit (ICU). The study duration is expected to be 24 months from first patient enrolled until completion of the final visit for the last patient. Participating centers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of participating centers and ethics committee approvals

| Participating center | PI | Central Ethics committee | Reference number | Approval date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical University Vienna, Department of Internal Medicine II. Division of Cardiology | Gottfried Heinz, MD | Ethics Committee, Medical University Vienna | ECS 1805/2017 | 15 September 2017 |

| Medical University Innsbruck, Division of Emergency Medicine and Intensive Care, Department Internal Medicine | Michael Joannidis, MD | |||

| State Hospital Wiener Neustadt, Department of Anesthesiology, Emergency Medicine and General Intensive Care | Helmut Trimmel, MD, MSc | |||

| University Hospital Greifswald, Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care, Emergency and Pain Medicine | Sebastian Rehberg, MD | Ethics Committee, University Hospital Greifswald | FFV 06/17 | 15 February 2018 |

| University Hospital Munich, Department of Anesthesiology | Christian Siebers, MD | |||

| University Hospital Hradec Králové, Department of Anesthesiology, Resuscitation and Intensive Medicine | Pavel Dostál, MD, PhD, MBA | Ethics Committee, University Hospital Hradec Králové | 201801 I126M | 07 November 2017 |

| Masaryk Hospital, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Medicine and Intensive Care | Vladimír Černý, MD, PhD, FCCM | |||

| University Hospital La Sapienza, Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care | Andrea Morelli, MD. | Ethics Committee, University Hospital La Sapienza | 4846 | 08 February 2018 |

| Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana, Department of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation 5 | Fabio Guarracino, MD | |||

| Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana, Department of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation 6 | Francesca Pratesi, MD | |||

| University School of Medicine Pisa, Department of Anesthesiology and Transplant Intensive Care Unit | Gianni Biancofiore, MD | |||

| University Hospital Modena, Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care | Massimo Girardis, MD | Approval pending | ||

The study objective is to compare the percentage of patients with a HR response (defined as HR within the target range of 80–94 bpm) and maintenance thereof without an increase in vasopressor requirements within the first 24 h of treatment, and to further assess efficacy and safety in the two treatment arms: standard of care treatment and landiolol (landiolol group) or standard of care treatment alone (control group).

Additional file 1 contains the completed Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) checklist.

Study population

This study will enroll a total of 200 patients with septic shock and elevated HR (≥ 95 bpm) despite a hemodynamic optimization phase of at least 24 h but a maximum of 36 h in which they received adequate fluid resuscitation and continuous vasopressor treatment (according to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines 2016 [40]). Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria 1. Informed consent 2. Age ≥ 18 years 3. Confirmed septic shock: a. Confirmed or suspected infection b. Acute increase of ≥ 2 points on SOFA Score c. Need for continuous vasopressor therapy to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of > 65 mmHg despite adequate fluid resuscitation d. Blood lactate > 2 mmol/L (18 mg/dL)a 4. Tachycardia and/or tachyarrhythmia with heart rate ≥ 95 bpm 5. Norepinephrine infusion rate ≥ 0.2 μg/kg/min at the time of study inclusion 6. Patients must have undergone a hemodynamic optimization period of at least 24 h but a maximum of 36 h, during which period they received continuous vasopressor treatment and standard treatment for septic shock according to the SSCG 2016 guidelines aPresence of blood lactate > 2 mmol/L (18 mg/dL) and increase of ≥ 2 points on SOFA score are mandatory for the diagnosis of septic shock, but must not necessarily be present at the time of study inclusion Exclusion criteria: 1. Any form of compensatory tachycardia 2. β-blocker treatment within 72 h before randomization 3. Sick sinus syndrome, or second or third degree AV block 4. Patients with any form of cardiac pacing 5. A known serious cardiovascular condition such as ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack within the last six months, or pre-existing heart failure NYHA class III or IV 6. Cardiogenic shock 7. MAP < 65 mmHg 8. Known pulmonary hypertension 9. Known terminal illness other than septic shock with expected patient’s survival < 28 days 10. Known presence of an advanced condition to withhold life-sustaining treatment 11. Patients for whom a “Do Not Resuscitate” (DNR) order exists 12. Known sensitivity to any component of the study medication (e.g. landiolol, mannitol) 13. Participation in a clinical drug trial within 30 days before randomization 14. Any condition that, in the investigator’s opinion, makes the individual unsuitable for study participation (to be documented) 15. Pregnant or breast-feeding patients 16. Untreated pheochromocytoma |

NYHA New York Heart Association

Randomization, blinding, and treatment allocation

Patients fulfilling the selection criteria are randomized in a 1:1 ratio to one of the two groups (landiolol or control) after informed consent, as required by local law, has been obtained. The presence of atrial fibrillation in the hemodynamic optimization period is used as a stratification factor for randomization. As this is an open label study, investigators and other study personnel will not be blinded to the treatment.

Study drug

Lyophilized landiolol hydrochloride 300 mg (Rapibloc Lyo, 300 mg) is to be reconstituted in 50 mL of 0.9% NaCl to a concentration of 6 mg/mL before use.

Treatments

Landiolol group

Patients in the landiolol group begin continuous infusion with landiolol within 2 h after randomization at a starting dose of 1 mcg/kg/min. The dose is to be progressively increased at increments of 1 mcg/kg/min to a maximum of 40 mcg/kg/min at intervals of at least 20 min to obtain and maintain a HR of 80–94 bpm. Landiolol must be infused continuously to maintain the target HR until one the following events occurs: discontinuation of vasopressor infusion; death; a serious adverse event (AE) attributable to the study drug that necessitates study drug discontinuation as determined by the investigator; patient discharge from the ICU; or day 28 of study participation.

Control group

Patients in the control group receive standard of care treatment according to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines 2016 [40], which does not specify a target for HR control. Patients in the control group are to be withdrawn from the study if they receive beta-blocker treatment.

Patient assessments

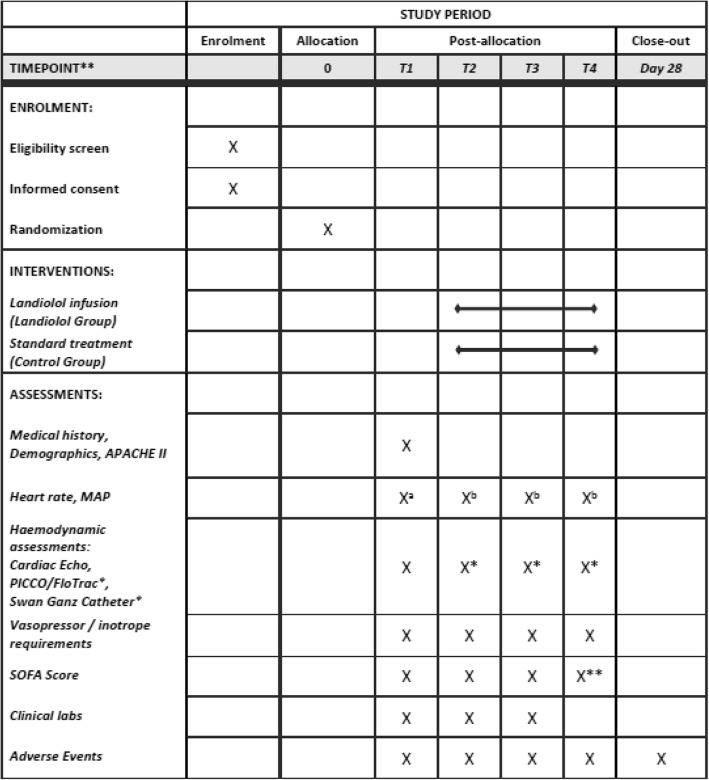

Heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature will be documented hourly for the first 24 h after treatment start and every 12 h thereafter in both treatment groups, and additionally at every dose change of landiolol in the landiolol group. Clinical laboratory analysis including blood gas analysis will be performed daily for the first four days of the study. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score will be assessed daily for the first four days and every third day thereafter. If performed, hemodynamic parameters (CO, CI, GEDI, ELWI, PAOP, MPAP, LVEF, TAPSE, VTI) obtained by PICCO/FloTrac, Swan-Ganz catheter or Cardiac Echo will be documented. Concomitant medication and AE will be documented over the entire study period. Measurements and assessments performed in both groups are listed in Fig. 1 in the completed SPIRIT figure.

Fig. 1.

Schedule of enrolment and assessments (SPIRIT 2013 Figure)

Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint is HR response (HR = 80–94 bpm) and maintenance thereof without increase in vasopressor requirements during the first 24 h after treatment start.

Secondary efficacy endpoints will consist of ICU and 28-day mortality, ICU and hospital stay duration, SOFA score, and inotrope and vasopressor support requirements. Efficacy and safety endpoints are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Efficacy and safety endpoints

| Primary endpoint: • HR response (i.e. HR = 80–94 bpm) and maintenance thereof and no increase in vasopressor requirements during the first 24 h after treatment start Secondary endpoints: • Change in vasopressor requirements over the study period (dose and duration) • HR response (i.e. HR = 80–94 bpm) during the first 24 h after treatment start • 28-day mortality (all cause) • ICU mortality (all cause) • Duration of ICU stay (survivors/non-survivors) • Duration of hospital stay (survivors/non-survivors) • SOFA score (as long as the patient is treated with vasopressors) on days 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, 25, and 28 • Daily inotropic requirements (as long as the patient is treated with vasopressors) Safety endpoints: • Incidence rate of bradycardic episodes requiring intervention • Incidence of adverse events (AE) • Incidence of serious adverse events (SAE) |

Data collection

Data will be collected and entered into the electronic data capture system by trained study personnel (investigators and study nurses).

Sample size

Sample size estimation is based upon the assumption that 60% of patients in the landiolol group reach the primary endpoint versus 40% of patients in the control group. The sample size of 200 patients will provide 80% power to demonstrate a statistically significant difference (upon standard level alpha = 0.05) between the treatment groups using a Chi-square test. The sample size in the study by Morelli et al. [10] was adequate considering that to detect a 20% change in HR with a power of 80% at a level of significance of alpha = 0.05, 64 patients per group would have been required. In order to detect the binary primary endpoint of our study an additional 36 patients per group are required.

Statistical analysis

The hypothesis that Group L is superior to Group C in proportion of patients who reached the primary endpoint will be demonstrated if the lower limit of the two-sided 95% Newcombe confidence interval of difference pL-pC is above zero, where pL and pC are percentages of patients who reached the primary endpoint in Group L and Group C, respectively. P values based on Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (according to SAS® terminology) will be presented together with the confidence intervals to evaluate statistical significance of association between treatment group and outcome after adjustment for the stratification group. For the purpose of exploratory analysis, the individual criteria of the primary endpoint, heart rate response (i.e. HR = 80–94 bpm) reached (also defined as secondary endpoint), heart rate response reached and maintained and no increase in vasopressor requirements during the first 24 h, will be compared separately between treatment groups. Additional subgroup and sensitivity analyses will have exploratory character and will be defined in all details in the SAP.

Secondary endpoints with continuous, ordinal, and binary variables measured at multiple time-points will be analyzed as longitudinal data by linear, ordinal logistic, logistic, or log-binomial regression models with repeated measures. Covariates used in the models will be (but not limited to) treatment, visit, stratification group, and interaction treatment/visit. For continuous variables baseline value of the outcome variable will be a covariate as well. Distribution of data and a feasibility check of planned analyses will be performed before finalization of SAP and alternative statistical methods will be defined if assumptions on the application of the planned methods are not met (e.g. ln-transformation of data, non-parametric method, or other alternative way). ICU mortality and 28-day mortality will be analyzed using the same methods as for the primary endpoint. Duration of ICU stay and duration of hospital stay (in survivors/non-survivors) will be analyzed as time-to-event data (using Kaplan–Meier curve and using log-rank test or Wilcoxon test and/or proportional hazards regression model if appropriate).

For secondary analyses, no multiplicity adjustment is planned; therefore, a higher rate of type-I error must be considered in interpretation of results of secondary analyses. The analysis of secondary endpoints/analyses can provide supportive evidence related to the primary objective, but no confirmatory conclusion based on secondary analyses can be done.

Discussion

Despite intensive research, morbidity and mortality of patients with sepsis remain high [39]. Hence, novel therapeutic concepts are urgently needed. Recently, the use of beta-blockers during sepsis has been suggested [10, 28–30, 32, 41]. This represents a true innovation, as current guidelines recommend beta-mimetics [40]. The potential benefits of beta-blockers are most likely due to their pleotropic effects and include myocardial protection, modulation of inflammatory processes, and improvements in organ functions [3, 22, 42–44]. However, it is still unclear which patients would benefit most from this intervention.

Morelli et al. [10] (and later others [28–30, 32]) showed that a HR reduction in patients with septic shock, after adequate resuscitation with fluids, vasopressors, and inotropes, was not associated with an increase in AEs and did not trigger an increase in vasopressor support. As in the original protocol by Morelli et al. [10], the target HR in the present study is < 95 bpm, which is based on studies showing poorer patient outcomes when this threshold is exceeded and studies showing good tolerance after achieving this target with beta-blockers [7, 11, 45–48]. More recently, several studies conducted in China [28–30, 32] that selected a similar HR target showed good tolerance of the beta-blocker treatment. Therefore, the HR target of < 95 bpm seems appropriate for further comparison and optimal with respect to feasibility and tolerance.

In order to minimize the risk of hemodynamic compromise, patients are only included in the study after at least 24 h of adequate fluid resuscitation and vasopressor support. In addition, landiolol is started at a low dose of 1 mcg/kg/min (as supported by landiolol sepsis [49], postoperative [50], and heart failure studies [51]) and titration is performed conservatively at 20-min intervals (5 half-lives) [35]. The HR target should be reached within the first 24 h, as supported by published data [28–30, 32].

Esmolol is the beta-blocker that has been most frequently evaluated in patients with sepsis, as its pharmacokinetic profile allows for rapid titration when used intravenously [10, 27–29, 31]. However, landiolol has demonstrated a more favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile than esmolol [52–55]. Landiolol has a faster onset (1 min vs 2 min) and shorter half-life (4 min vs 9 min) than esmolol, which should allow for more rapid titration and enhanced safety [35]. Furthermore, the beta1 selectivity of landiolol is eight times higher than that of esmolol, resulting in a beta1/beta2 ratio of 255 [35]. This provides landiolol with more profound negative chronotropic effects and a lesser degree of negative inotropic and hypotensive action [36–38, 56].

This study will investigate whether HR control using the short-acting beta-blocker landiolol is feasible, safe, and effective in patients with septic shock and persistent tachycardia, and provide a better understanding of the potential role of beta-blockers in this patient population.

Trial status

Protocol version 3.0 dated 3 January 2018. The first participant was enrolled on 24 February 2018.

Additional file

Checklist_SPIRIT_guidelines.pdf, Checklist of the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines. (PDF 129 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Alain Rudiger for his support and feedback during the writing of the study protocol and this publication.

Funding

This study is sponsored by AOP Pharmaceuticals AG and co-sponsored by Amomed Pharma GmbH.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- APACHE II

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- AV

Atrioventricular

- Bpm

Beats per minute

- CI

Cardiac Index

- CO

Cardiac output

- ELWI

Extravascular lung water index

- GEDI

Global end-diastolic volume index

- HR

Heart rate

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- MPAP

Mean pulmonary arterial pressure

- PAOP

Pulmonary arterial occlusion pressure

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- PICCO

Pulse contour cardiac output

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- SPIRIT

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials

- TAPSE

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

- VTI

Velocity time integral

Authors’ contributions

MU, AM, MS, PR, SR, HT, MJ, KK, GH, VC, PD, CS, FG, FP, GB, MG, BGI, MZ, CKL, and GK contributed to the design of the trial. PK provided the statistical analysis. MU and OB drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approvals of central ethics committees are listed in Table 1.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MU, GK, BGI, MZ, KK, and CK are employees of AOP Pharmaceuticals AG, OB is an employee of Amomed Pharma GmbH.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Martin Unger, Email: martin.unger@aoporphan.com.

Andrea Morelli, Email: andrea.morelli@uniroma1.it.

Mervyn Singer, Email: m.singer@ucl.ac.uk.

Peter Radermacher, Email: peter.radermacher@uni-ulm.de.

Sebastian Rehberg, Email: Sebastian.Rehberg@uni-greifswald.de.

Helmut Trimmel, Email: helmut.trimmel@wienerneustadt.lknoe.at.

Michael Joannidis, Email: michael.joannidis@i-med.ac.at.

Gottfried Heinz, Email: Gottfried.Heinz@meduniwien.ac.at.

Vladimír Cerny, Email: cernyvla1960@gmail.com.

Pavel Dostál, Email: pavel.dostal@fnhk.cz.

Christian Siebers, Email: Christian.Siebers@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Fabio Guarracino, Email: f.guarracino@ao-pisa.toscana.it.

Francesca Pratesi, Email: francesca.pratesi@hotmail.it.

Gianni Biancofiore, Email: g.biancofiore@med.unipi.it.

Massimo Girardis, Email: girardis.massimo@unimore.it.

Pavla Kadlecova, Email: pkadlecova@aixial.com.

Olivier Bouvet, Email: o.bouvet@amomed.com.

Michael Zörer, Email: michael.zoerer@aoporphan.com.

Barbara Grohmann-Izay, Email: barbara.grohmann-izay@aoporphan.com.

Kurt Krejcy, Email: kurt.krejcy@aoporphan.com.

Christoph Klade, Email: christoph.klade@aoporphan.com.

Günther Krumpl, Email: guenther.krumpl@aoporphan.com.

References

- 1.Parrillo JE. Pathogenetic mechanisms of septic shock. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1471–1477. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marx G, Vangerow B, Burczyk C, Gratz KF, Maassen N, Cobas Meyer M, et al. Evaluation of noninvasive determinants for capillary leakage syndrome in septic shock patients. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1252–1258. doi: 10.1007/s001340000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhagat K, Hingorani AD, Palacios M, Charles IG, Vallance P. Cytokine-induced venodilatation in humans in vivo: eNOS masquerading as iNOS. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:754–764. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werdan K, Schmidt H, Ebelt H, Zorn-Pauly K, Koidl B, Hoke RS, et al. Impaired regulation of cardiac function in sepsis, SIRS, and MODS. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;87:266–274. doi: 10.1139/Y09-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt H, Müller-Werdan U, Hoffmann T, Francis DP, Piepoli MF, Rauchhaus M, et al. Autonomic dysfunction predicts mortality in patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome of different age groups. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1994–2002. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000178181.91250.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmittinger CA, Torgersen C, Luckner G, Schröder DCH, Lorenz I, Dünser MW. Adverse cardiac events during catecholamine vasopressor therapy: A prospective observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:950–958. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sander O, Welters ID, Foëx P, Sear JW. Impact of prolonged elevated heart rate on incidence of major cardiac events in critically ill patients with a high risk of cardiac complications. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:81–88. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000150028.64264.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudiger A, Singer M. The heart in sepsis: from basic mechanisms to clinical management. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013;11:187–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morelli A, Ertmer C, Westphal M, Rehberg S, Kampmeier T, Ligges S, et al. Effect of heart rate control with esmolol on hemodynamic and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2013;310:1683. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leibovici L, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M, Almanasreh N, Tacconelli E, Andreassen S, et al. Relative tachycardia in patients with sepsis: An independent risk factor for mortality. QJM. 2007;100:629–634. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dünser MW, Hasibeder WR. Sympathetic overstimulation during critical illness: Adverse effects of adrenergic stress. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24:293–316. doi: 10.1177/0885066609340519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayase N, Yamamoto M, Asada T, Isshiki R, Yahagi N, Doi K. Association of heart rate with N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide in septic patients: a prospective observational cohort study. Shock. 2016;46:642–648. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vellinga NAR, Boerma EC, Koopmans M, Donati A, Dubin A, Shapiro NI, et al. International study on microcirculatory shock occurrence in acutely Ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:48–56. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoke RS, Müller-Werdan U, Lautenschläger C, Werdan K, Ebelt H. Heart rate as an independent risk factor in patients with multiple organ dysfunction: A prospective, observational study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2012;101:139–147. doi: 10.1007/s00392-011-0375-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grander W, Müllauer K, Koller B, Tilg H, Dünser M. Heart rate before ICU discharge: A simple and readily available predictor of short- and long-term mortality from critical illness. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102:599–606. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du W, Liu D, Long Y, Wang X. The β-blocker esmolol restores the vascular waterfall phenomenon after acute endotoxemia. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:e1247–e1253. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei C, Louis H, Schmitt M, Albuisson E, Orlowski S, Levy B, et al. Effects of low doses of esmolol on cardiac and vascular function in experimental septic shock. Crit Care. 2016;20:407. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1580-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimmoun A, Louis H, Al Kattani N, Delemazure J, Dessales N, Wei C, et al. β1-adrenergic inhibition improves cardiac and vascular function in experimental septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:e332–e340. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calzavacca P, Lankadeva YR, Bailey SR, Bailey M, Bellomo R, May CN. Effects of selective β1-adrenoceptor blockade on cardiovascular and renal function and circulating cytokines in ovine hyperdynamic sepsis. Crit Care. 2014;18(6):610. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0610-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aboab J, Sebille V, Jourdain M, Mangalaboyi J, Gharbi M, Mansart A, et al. Effects of esmolol on systemic and pulmonary hemodynamics and on oxygenation in pigs with hypodynamic endotoxin shock. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1344–1351. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2236-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Maeda H, Noguchi T. Landiolol, an ultrashort-acting β1-adrenoceptor antagonist, has protective effects in an lps-induced systemic inflammation model. Shock. 2009;31:515–520. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181863689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki T, Morisaki H, Serita R, Yamamoto M, Kotake Y, Ishizaka A, et al. Infusion of the beta-adrenergic blocker esmolol attenuates myocardial dysfunction in septic rats. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2294–2301. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000182796.11329.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackland GL, Yao ST, Rudiger A, Dyson A, Stidwill R, Poputnikov D, et al. Cardioprotection, attenuated systemic inflammation, and survival benefit of β1-adrenoceptor blockade in severe sepsis in rats. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:388–394. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c03dfa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, Li M, Duan J, Yi L, Huang X, Chen D, et al. Effect of esmolol on hemodynamics and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2017;29:390–395. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balik M, Ruliseky J, Leden P, Zakharchenko M, Otahal M, Bartakova H, et al. Concomitant use of beta-1 adrenoreceptor blocker and norepinephrine in patients with septic shock. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:552–556. doi: 10.1007/s00508-012-0209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du W, Wang X-T, Long Y, Liu D-W. Efficacy and safety of esmolol in treatment of patients with septic shock. Chin Med J. 2016;129:1658. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.185856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shang X, Wang K, Xu J, Gong S, Ye Y, Chen K, et al. The effect of esmolol on tissue perfusion and clinical prognosis of patients with severe sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2016/1038034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z, Wu Q, Nie X, Guo J, Yang C. Combination therapy with milrinone and esmolol for heart protection in patients with severe sepsis: a prospective, randomized trial. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35:707–716. doi: 10.1007/s40261-015-0325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xinqiang L, Weiping H, Miaoyun W, Wenxin Z, Wenqiang J, Shenglong C, et al. Esmolol improves clinical outcome and tissue oxygen metabolism in patients with septic shock through controlling heart rate. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2015;27:759–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tao Y, Jingyi W, Xiaogan J, Weihua L, Xiaoju J. Effect of esmolol on fluid responsiveness and hemodynamic parameters in patients with septic shock. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2015;27:885–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang S, Liu Z, Yang W, Zhang G, Hou B, Liu J, et al. Effects of the beta-blockers on cardiac protection and hemodynamics in patients with septic shock: a prospective study. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2014;26:714–717. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen JX, Sun J, Liu YY, Jia BH. Effects of adrenergic beta-1 antagonists on hemodynamics of severe septic patients. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013;93:1243–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morelli A, Donati A, Ertmer C, Rehberg S, Kampmeier T, Orecchioni A, et al. Microvascular effects of heart rate control with esmolol in patients with septic shock: A pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2162–2168. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a678d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plosker GL. Landiolol: A review of its use in intraoperative and postoperative tachyarrhythmias. Drugs. 2013;73:959–977. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibata S, Okamoto Y, Endo S, Ono K. Direct effects of esmolol and landiolol on cardiac function, coronary vasoactivity, and ventricular electrophysiology in guinea-pig hearts. J Pharmacol Sci. 2012;118:255–265. doi: 10.1254/jphs.11202FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sasao J, Tarver SD, Kindscher JD, Taneyama C, Benson KT, Goto H. In rabbits, landiolol, a new ultra-short-acting β-blocker, exerts a more potent negative chronotropic effect and less effect on blood pressure than esmolol. Can J Anesth. 2001;48:985–989. doi: 10.1007/BF03016588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krumpl G, Ulč I, Trebs M, Kadlecová P, Hodisch J, Maurer G, et al. Pharmacodynamic and -kinetic behavior of low-, intermediate-, and high-dose landiolol during long-term infusion in whites. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2017;70:42–51. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singer M, CS D, Seymour C, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:486–552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanfilippo F, Santonocito C, Morelli A, Foex P. Beta-blocker use in severe sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:1817–1825. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1062357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogura Y, Jesmin S, Yamaguchi N, Oki M, Shimojo N, Islam MM, et al. Potential amelioration of upregulated renal HIF-1alpha–endothelin-1 system by landiolol hydrochloride in a rat model of endotoxemia. Life Sci. 2014;118:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mori K, Morisaki H, Yajima S, Suzuki T, Ishikawa A, Nakamura N, et al. Beta-1 blocker improves survival of septic rats through preservation of gut barrier function. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1849–1856. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seki Y, Jesmin S, Shimojo N, Islam MM a, Rahman MA r, Khatun T, et al. Significant reversal of cardiac upregulated endothelin-1 system in a rat model of sepsis by landiolol hydrochloride. Life Sci. 2014;118:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmittinger CA, Dünser MW, Haller M, Ulmer H, Luckner G, Torgersen C, et al. Combined milrinone and enteral metoprolol therapy in patients with septic myocardial depression. Crit Care. 2008;12(4):R99. doi: 10.1186/cc6976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuishi Y, Jesmin S, Kawano S, Hideaki S, Shimojo N, Mowa CN, et al. Landiolol hydrochloride ameliorates acute lung injury in a rat model of early sepsis through the suppression of elevated levels of pulmonary endothelin-1. Life Sci. 2016;166:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azimi G, Vincent JL. Ultimate survival from septic shock. Resuscitation. 1986;14:245–253. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(86)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parker MM, Shelhamer JH, Natanson C, Alling DW, Parrillo JE. Serial cardiovascular variables in survivors and nonsurvivors of human septic shock: Heart rate as an early predictor of prognosis. Crit Care Med. 1987;15:923–929. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okajima M, Takamura M, Taniguchi T. Landiolol, an ultra-short-acting β1-blocker, is useful for managing supraventricular tachyarrhythmias in sepsis. World J Crit Care Med. 2015;4:251–257. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v4.i3.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamura T, Yatabe T, Yokoyama M. Prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery using low-dose landiolol: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2017;42:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagai R, Kinugawa K, Inoue H, Atarashi H, Seino Y, Yamashita T, et al. Urgent management of rapid heart rate in patients with atrial fibrillation/flutter and left ventricular dysfunction: comparison of the ultra-short-acting β1-selective blocker landiolol with digoxin (J-Land Study) Circ J. 2013;77:908–916. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Syed YY. Landiolol: a review in tachyarrhythmias. Drugs. 2018;78:377–388. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0883-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krumpl G, Ulc I, Trebs M, Kadlecová P, Hodisch J. Bolus application of landiolol and esmolol: comparison of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles in a healthy Caucasian group. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73:417–428. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krumpl G, Ulc I, Trebs M, Kadlecová P, Hodisch J, Maurer G, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of low-, intermediate-, and high-dose landiolol and esmolol during long-term infusion in healthy whites. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2018;71(3):137–146. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krumpl G, Ulc I, Trebs M, Kadlecová P, Hodisch J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of two different landiolol formulations in a healthy Caucasian group. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2016;92:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ikeshita K, Nishikawa K, Toriyama S, Yamashita T, Tani Y, Yamada T, et al. Landiolol has a less potent negative inotropic effect than esmolol in isolated rabbit hearts. J Anesth. 2008;22:361–366. doi: 10.1007/s00540-008-0640-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Checklist_SPIRIT_guidelines.pdf, Checklist of the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines. (PDF 129 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.