Abstract

Background

Anemia is one of the most common diseases of childhood and is a health problem globally, particularly in developing counties and in children less than 2 years of age. Anemia during childhood has short- and long-term effects on health. However, few studies have investigated the prevalence of anemia among children in Huaihua. Therefore, this study analyzed the prevalence and risk factors of anemia among children 6 to 23 months of age in Huaihua.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a maternal and child health care hospital in Huaihua, from September to November 2017. The study population recruited using a multistage sampling technique. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data on the characteristics of the children and members of their families. Hemoglobin (Hb) levels were measured by using a microchemical reaction method. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify associated factors and odds ratio with 95% CI was computed to assess the strength of association.

Results

In total, 4450 children were included in this study. The prevalence of anemia was 29.73%. In multivariate logistic regression analysis, the results show that mother and father of Miao ethnicity (OR = 1.23 and 1.31), diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks (OR = 1.35), breastfeeding in the prior 24 h (OR = 1.50), and caregivers able to identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding (OR = 1.15) had positive correlations with anemia. However, children aged 18 to 23 months (OR = 0.55), father of Dong ethnicity (OR = 0.82), addition of milk powder once or twice (OR = 0.71), addition of infant formula once or twice, three times, and four or more times in the previous 24 h (OR = 0.72, 0.70, and 0.75), and addition of a nutrient sachet four or more times in the prior week (OR = 0.70) were negatively associated with anemia.

Conclusions

The prevalence of anemia among children 6 to 23 months of age in Huaihua was higher than that in more developed regions of China. The feeding practice of caregivers was associated with anemia. nutrition improvement projects are needed to reduce the burden of anemia among children in Huaihua.

Keywords: Risk factors, Anemia, Children

Background

Anemia is one of the most common diseases of childhood and is a health problem globally, particularly in developing counties and in children less than 2 years of age [1, 2]. From 1993 to 2005, the global prevalence of anemia was 47.4% among children less than 5 years of age, and 46–66% in developing countries [3, 4]. In China in 2012, 28.2 and 20.5% of children 6–12 and 13–24 months of age, respectively, had anemia [5].

Anemia during childhood has short- and long-term effects on health. The former include an increased risk of morbidity due to infectious disease [4, 6, 7]. In addition, anemia during childhood is strongly associated with neurological development, and cognitive and immune function, and can lead to mental impairment and poor motor development [8, 9]. The long-term effects include reduced academic achievement and work capacity in adulthood [7, 10].

The majority of related studies show that anemia during childhood is strongly associated with food intake [11, 12]. Others reveal that economic status [13], residence in an urban or rural area [14], caregiver’s educational level [7], fever and diarrhea [15], low birth weight [7], and insufficient nutrition [15] are related to anemia during childhood.

The government of China provides nutrient sachets to children aged 6 to 23 months in poor areas of China, which has dramatically decreased the prevalence of anemia in children in western China [16, 17]. However, few studies have investigated the prevalence of anemia, or the effect of the nutrient sachet program thereon, among children in Huaihua.

Therefore, this cross-sectional study analyzed the prevalence and risk factors of anemia among children 6 to 23 months of age in Huaihua. Our findings will enable the development of countermeasures to reduce the burden of anemia and promote the health of children.

Materials and methods

Study design and area

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a maternal and child health care hospital in Huaihua, the largest city in midwestern China, from September to November 2017. The population of Huaihua in 2017 was 5,450,289, of which 322,876 were children under 5 years of age. A nutrient sachet program has been implemented in Huaihua since 2012.

Study population and sampling techniques

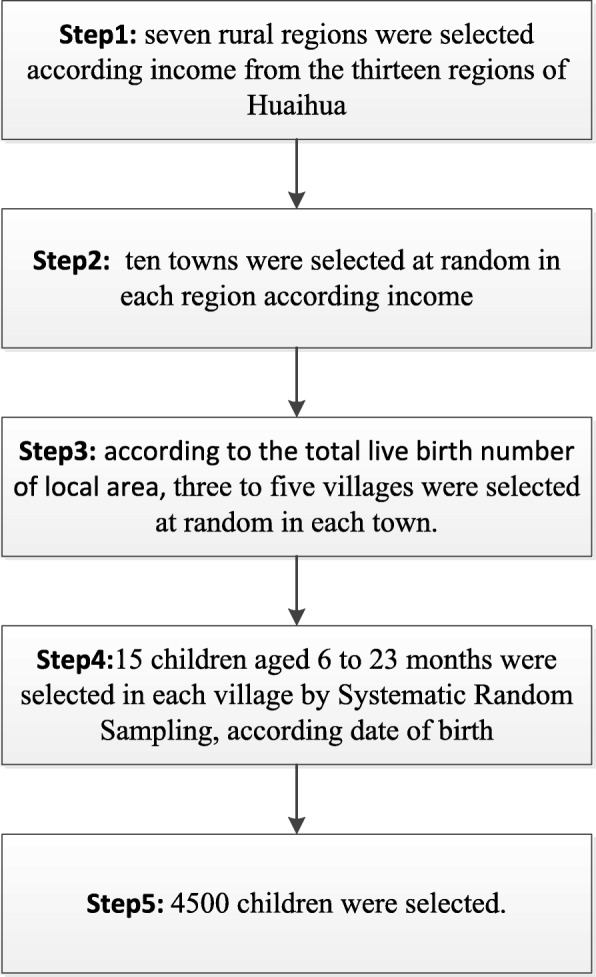

The study population consisted of caregivers and their children 6 to 23 months of age in seven rural regions of Huahuai recruited using a multistage sampling technique. Initially, the 13 regions of Huaihua line up according income, 7 rural regions were selected according income. Secondly, all towns of each region line up according income, ten towns were selected at random in each region. Then all villages of each town line up according income, three to five villages were selected at random in each town. According to the total number of live births, three villages were selected in Zhijiang and Huitong, four villages in Xinghuang, and five villages in Yuangling, Xupu, Mayang, and Chenxi. In total, 300 villages were selected. All children 6 to 23 months of age in each village line up according date of birth and 15 children 6 to 23 months of age in each village were selected by systematic random sampling, for a total of 4500 children (See Fig. 1). Income data were obtained from the 2016 Huaihua Statistical Yearbook and the number of live births from the 2016 Child Annual Report.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the sampling process

Data collection

A structured questionnaire was used to collect data on the demographic characteristics of the children and members of their families, as well as the children’s health status, feeding practice in the previous 24 h, and the caregivers’ level of knowledge of nutrition. Information on the children’s health status included gestational age, birth weight, and any episode of fever or diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks. The questionnaire was designed by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention to assess pilot projects for improving child nutrition in poverty-stricken areas of China. Hemoglobin (Hb) levels were measured in the fingertip peripheral blood of the children using a microchemical reaction method and Hemocue 301 instrument (Hemocue AB, Sweden), and were expressed as g/dL. Blood samples were collected in local public health centers. Anemia was assessed based on the criteria of Pediatrics, seventh edition published by the People’s Medical Publishing House. The cut-off point for anemia for children 6 to 23 months of age was < 11.0 g/dL Hb.

Statistical analysis

Data were cleaned, coded, and entered using Epidata 3.1 and analyzed by Statistical Product and Service Solutions 13. A descriptive analysis was performed to summarize the data, followed by bivariate logistic regression analyses of caregivers’ ethnicity, educational level, occupations, group, and level of knowledge of nutrition, as well as the age, sex, preterm birth, low birth weight, episode of diarrhea or fever in the previous 2 weeks, and food intake in the prior 24 h of the children. Factors with a value of P ≤ 0.10 in a bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable stepwise logistic regression model. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to determine the strength of associations. A value of P < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was signed by the caregivers of the children prior to their being interviewed. The project complies with national guidelines and does not involve personal privacy. The project was approved by Huaihua Women's Federation and Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (No. 201563).

Results

Demographic characteristics and health status

In total, 4450 children were included in this study. Fifty children whose caregivers refused to be interviewed were excluded (collection rate, 98.88%). The characteristics of the 4450 children are listed in Table 1. The prevalence of anemia was 29.73%. The educational level of > 70% of the parents/caregivers was under senior. The parents of almost 50% of the children were of Han ethnicity. The majority of the mothers and caregivers were homemakers (48.74 and 99.64%, respectively). Of the caregivers of the children, 61.71% were their mothers. The incidences of premature birth and a low birth weight were less than 5%. Of the children, 18.58 and 12.20% reported that they had experienced fever and diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks (Table 2).

Table 1.

The demographic characteristic of children 6 to 23 months of age (n = 4450)

| Characteristic | Frequencies | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Boys | 2345 | 52.70 |

| Girls | 2105 | 47.30 |

| Age | ||

| 6~ 11 months | 1536 | 34.52 |

| 12~ 17 months | 1411 | 31.71 |

| 18~ 23 months | 1503 | 33.78 |

| Mother’s ethnicity | ||

| Han | 2219 | 49.87 |

| Dong | 991 | 22.27 |

| Miao | 1012 | 22.74 |

| Others | 228 | 5.12 |

| Mother’s educational level | ||

| Primary | 409 | 9.19 |

| Junior | 2953 | 66.36 |

| Senior | 828 | 18.61 |

| University | 260 | 5.84 |

| Mother’s occupation | ||

| Homemakers | 2169 | 48.74 |

| Professionals | 143 | 3.21 |

| Commerce | 227 | 5.10 |

| Animal husbandry and fishery | 1225 | 27.53 |

| Operators equipment | 79 | 1.78 |

| Others | 607 | 13.64 |

| Father’s ethnicity | ||

| Han | 2133 | 47.93 |

| Dong | 1120 | 25.17 |

| Miao | 1007 | 22.63 |

| Others | 190 | 4.27 |

| Father’s occupation | ||

| Homemakers | 791 | 17.78 |

| Professionals | 316 | 7.10 |

| Commerce | 350 | 7.87 |

| Animal husbandry and fishery | 1678 | 37.71 |

| Operators equipment | 305 | 6.85 |

| Others | 1010 | 22.70 |

| Father’s educational level | ||

| Primary | 326 | 7.33 |

| Junior | 2957 | 66.45 |

| Senior | 858 | 19.28 |

| University | 309 | 6.94 |

| Caregiver’s groups | ||

| Mothers | 2746 | 61.71 |

| Fathers | 42 | 0.94 |

| Grandparents | 1651 | 37.10 |

| Others | 11 | 0.25 |

| Caregiver’s educational level | ||

| Primary | 3243 | 72.88 |

| Junior | 938 | 21.08 |

| Senior | 257 | 5.78 |

| University | 12 | 0.27 |

| Caregiver’s occupation | ||

| Professionals | 16 | 0.36 |

| Homemakers | 4434 | 99.64 |

| Anemia status | ||

| Normal | 3127 | 70.27 |

| Anemia | 1323 | 29.73 |

Table 2.

Health status of children 6 to 23 months of age(n = 4450)

| Characteristic | Frequencies | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational age | ||

| Term | 4270 | 95.96 |

| Premature | 180 | 4.04 |

| Birth weight | ||

| Normal | 4279 | 96.16 |

| Low birth weight | 171 | 3.84 |

| Fever in the previous 2 weeks | ||

| No | 3623 | 81.42 |

| Yes | 827 | 18.58 |

| Diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks | ||

| No | 3907 | 87.80 |

| Yes | 543 | 12.20 |

Feeding practice and nutrition knowledge

In the previous 24 h, most of the children had consumed water, soup, rice soup (92.45%), and solid/semisolid food (92.61%), but only 6.94% had consumed yogurt. Of the children, 31.03% had consumed infant formula once or twice and 48.85% had consumed a nutrient sachet four times or more in the prior week (Table 3). Of the caregivers, 44.20% could identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding but only 5.06% could identify the first complementary food which should be consumed by infants (Table 4).

Table 3.

Feeding practice of children 6 to 23 months of age in the previous 24 h (n = 4450)

| Feeding Practice | Frequencies | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding | ||

| No | 3205 | 72.02 |

| Yes | 1245 | 27.98 |

| Consume water, soup, rice soup | ||

| No | 336 | 7.55 |

| Yes | 4114 | 92.45 |

| Consume sugary drink | ||

| No | 3160 | 71.01 |

| Yes | 1290 | 28.99 |

| Consume infant formula and frequencies | ||

| 0 | 1951 | 43.84 |

| 1 to 2 | 1381 | 31.03 |

| 3 | 613 | 13.78 |

| 4 or more | 505 | 11.35 |

| Consume milk powder and frequencies | ||

| 0 | 3698 | 83.10 |

| 1 to 2 | 474 | 10.65 |

| 3 | 161 | 3.62 |

| 4 or more | 117 | 2.63 |

| Consume yoghourt and frequencies | ||

| 0 | 4141 | 93.06 |

| 1 to 2 | 279 | 6.27 |

| 3 | 12 | 0.27 |

| 4 or more | 18 | 0.40 |

| Consume solid/ semisolid food and frequencies | ||

| 0 | 329 | 7.39 |

| 1 to 2 | 1289 | 28.97 |

| 3 | 1715 | 38.54 |

| 4 or more | 1117 | 25.10 |

| Consume nutrient sachet and frequencies* | ||

| 0 | 1773 | 39.84 |

| 1 to 2 | 302 | 6.79 |

| 3 | 201 | 4.52 |

| 4 or more | 2174 | 48.85 |

*Consume nutrient sachet in the prior week

Table 4.

Caregivers nutrition knowledge of children 6 to 23 months of age (n = 4450)

| Nutrition Knowledge | Frequencies | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Is able identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding | ||

| No | 2483 | 55.80 |

| Yes | 1967 | 44.20 |

| Is able identify to the first complementary food which should be consumed by infants | ||

| No | 4225 | 94.94 |

| Yes | 225 | 5.06 |

| Has know the optimum food of supplementary iron | ||

| No | 3185 | 71.57 |

| Yes | 1265 | 28.43 |

| Is able identify nutrient relate to anemia | ||

| No | 2522 | 56.67 |

| Yes | 1928 | 43.33 |

| Is able identify the optimum timing of breastfeeding | ||

| No | 3852 | 86.56 |

| Yes | 598 | 13.44 |

Bivariate logistic regression analyses

Table 5 shows the results of bivariate logistic regression analyses of anemia among children 6 to 23 months of age. Compared to children 6 to 11 months of age, the prevalence of anemia was lower among those 12 to 17 and 18 to 23 months of age (OR = 0.64, 0.39 and P < 0.001, < 0.001, respectively). Compared to children with Han mothers and fathers, the prevalence of anemia was higher in those with Miao mothers and fathers (OR = 1.46, 1.44 and P < 0.001, < 0.001, respectively) and lower in children with Dong mothers and fathers (OR = 0.80, 0.80 and P = 0.010, 0.007, respectively). Compared to the children of homemaker mothers, those of mothers employed in the professions, commerce, as equipment operators, and other occupations had a lower risk of anemia (OR = 0.70, 0.65, 0.61, 0.60 and P = 0.072, 0.008, 0.073, < 0.001, respectively). Compared to the children of homemaker fathers, those of fathers employed in animal husbandry and fishery, and others had a lower risk of anemia (OR = 0.85, 0.81 and P = 0.085, 0.038, respectively). Compared to children cared for by their mothers, those cared for by their father or grandparents had a lower prevalence of anemia (OR = 0.46, 0.59 and P = 0.050, < 0.001, respectively). In addition, female gender (OR = 0.89, P = 0.078), mothers and fathers’ education to university level (OR = 0.65, 0.70, and P = 0.016, 0.046, respectively) were associated with a lower risk of anemia. Diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks was also correlated with anemia (OR = 1.50, P < 0.001).

Table 5.

Bivariate regression analysis of anemia among children 6 to 23 months of age

| Parameters | N | n | (%) | OR(95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Boy | 2345 | 724 | 30.87 | 1 | |

| Girl | 2105 | 599 | 28.46 | 0.89(0.78,1.10) | 0.078 |

| Age | |||||

| 6~ 11 months | 1536 | 604 | 39.32 | 1 | |

| 12~ 17 months | 1411 | 414 | 29.34 | 0.64(0.55,0.75) | < 0.001 |

| 18~ 23 months | 1503 | 305 | 20.29 | 0.39(0.33,0.46) | < 0.001 |

| Mother’s ethnicity | |||||

| Han | 2219 | 637 | 28.71 | 1 | |

| Dong | 991 | 241 | 24.32 | 0.80(0.67,0.95) | 0.010 |

| Miao | 1012 | 374 | 36.96 | 1.46(1.24,1.70) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 228 | 71 | 31.14 | 1.12(0.84,1.51) | 0.440 |

| Mother’s educational level | |||||

| Primary | 409 | 133 | 32.52 | 1 | |

| Junior | 2953 | 879 | 29.77 | 0.88(0.70,1.10) | 0.256 |

| Senior | 828 | 249 | 30.07 | 0.89(0.69,1.15) | 0.381 |

| University | 260 | 62 | 23.85 | 0.65(0.46,0.92) | 0.016 |

| Mother’s occupation | |||||

| Homemakers | 2169 | 704 | 32.46 | 1 | |

| Professionals | 143 | 36 | 25.17 | 0.70(0.48,1.03) | 0.072 |

| Commerce | 227 | 54 | 23.79 | 0.65(0.47,0.89) | 0.008 |

| Animal husbandry and fishery | 1225 | 376 | 30.69 | 0.92(0.79,1.07) | 0.290 |

| Operators equipment | 79 | 18 | 22.78 | 0.61(0.36,1.04) | 0.073 |

| Others | 607 | 135 | 22.24 | 0.60(0.48,0.76) | < 0.001 |

| Father’s ethnicity | |||||

| Han | 2133 | 617 | 28.93 | 1 | |

| Dong | 1120 | 274 | 24.46 | 0.80(0.68,0.94) | 0.007 |

| Miao | 1007 | 372 | 36.94 | 1.44(1.23,1.89) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 190 | 60 | 31.58 | 1.13(0.82,1.56) | 0.441 |

| Father’s educational level | |||||

| Primary | 326 | 108 | 33.13 | 1 | |

| Junior | 2957 | 874 | 29.56 | 0.85(0.66,1.08) | 0.182 |

| Senior | 858 | 261 | 30.42 | 0.88(0.67,1.16) | 0.369 |

| University | 309 | 80 | 25.89 | 0.70(0.50,0.99) | 0.046 |

| Father’s occupation | |||||

| Homemakers | 791 | 259 | 32.74 | 1 | |

| Professionals | 316 | 102 | 32.28 | 0.98(0.74,1.29) | 0.882 |

| Commerce | 350 | 100 | 28.57 | 0.82(0.62,1.10) | 0.162 |

| Animal husbandry and fishery | 1678 | 492 | 29.32 | 0.85(0.71,1.10) | 0.085 |

| Operators equipment | 305 | 85 | 27.87 | 0.79(0.59,1.06) | 0.120 |

| Others | 1010 | 285 | 28.22 | 0.81(0.66,0.99) | 0.038 |

| Caregiver’s groups | |||||

| Mothers | 2746 | 928 | 33.79 | 1 | |

| Fathers | 42 | 8 | 19.05 | 0.46(0.21,1.00) | 0.050 |

| Grandparents | 1651 | 385 | 23.32 | 0.59(0.52,0.68) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 11 | 2 | 18.18 | 0.43(0.09,2.02) | 0.288 |

| Caregiver’s educational level | |||||

| Primary | 3243 | 990 | 30.53 | 1 | |

| Junior | 938 | 262 | 27.93 | 0.88(0.75,1.04) | 0.127 |

| Senior | 257 | 69 | 26.85 | 0.83(0.63,1.11) | 0.217 |

| University | 12 | 2 | 16.67 | 0.45(0.10,2.08) | 0.310 |

| Caregiver’s occupation | |||||

| Professionals | 16 | 2 | 12.50 | 1 | |

| Homemakers | 4434 | 1321 | 29.79 | 2.97(0.67,13.08) | 0.150 |

| Gestational age | |||||

| Term | 4270 | 1265 | 29.63 | 1 | |

| Premature | 180 | 58 | 32.22 | 1.13(0.82,1.55) | 0.455 |

| Birth weight | |||||

| Normal | 4279 | 1276 | 29.82 | 1 | |

| Low birth weight | 171 | 47 | 27.49 | 0.89(0.63,1.26) | 0.513 |

| Fever in the previous 2 weeks | |||||

| No | 3623 | 1077 | 29.73 | 1 | |

| Yes | 827 | 246 | 29.75 | 1.10(0.85,1.18) | 0.991 |

| Diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks | |||||

| No | 3907 | 1119 | 28.64 | 1 | |

| Yes | 543 | 204 | 37.57 | 1.50(1.24,1.81) | < 0.001 |

| Breastfeeding | |||||

| No | 3205 | 788 | 24.59 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1245 | 534 | 42.89 | 2.30(2.00,2.64) | < 0.001 |

| Consume water, soup, rice soup | |||||

| No | 336 | 107 | 31.85 | 1 | |

| Yes | 4112 | 1215 | 29.55 | 0.90(0.71,1.14) | 0.377 |

| Consume sugary drink | |||||

| No | 3146 | 976 | 31.07 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1290 | 343 | 26.59 | 0.79(0.69,0.91) | 0.001 |

| Consume infant formula and frequencies | |||||

| 0 | 1951 | 697 | 35.73 | 1 | |

| 1 to 2 | 1381 | 328 | 23.75 | 0.56(0.48,0.65) | < 0.001 |

| 3 | 613 | 152 | 24.80 | 0.59(0.48,0.73) | < 0.001 |

| 4 or more | 505 | 146 | 28.91 | 0.73(0.59,0.91) | 0.004 |

| Consume milk powder and frequencies | |||||

| 0 | 3698 | 1145 | 30.96 | 1 | |

| 1 to 2 | 474 | 101 | 21.31 | 0.60(0.48,0.76) | < 0.001 |

| 3 | 161 | 45 | 27.95 | 0.86(0.61,1.23) | 0.418 |

| 4 or more | 117 | 32 | 27.35 | 0.84(0.55,1.27) | 0.405 |

| Consume yoghourt and frequencies | |||||

| 0 | 4141 | 1242 | 29.99 | 1 | |

| 1 to 2 | 279 | 74 | 26.52 | 0.84(0.64,1.11) | 0.220 |

| 3 | 12 | 3 | 25.00 | 0.78(0.21,2.88) | 0.707 |

| 4 or more | 18 | 4 | 22.22 | 0.67(0.22,2.03) | 0.476 |

| Consume solid/semisolid food and frequencies | |||||

| 0 | 329 | 99 | 30.09 | 1 | |

| 1 to 2 | 1289 | 410 | 31.81 | 1.08(0.83,1.41) | 0.550 |

| 3 | 1715 | 515 | 30.03 | 0.99(0.77,1.29) | 0.982 |

| 4 or more | 1117 | 299 | 26.77 | 0.85(0.65,1.11) | 0.236 |

| Consume nutrient sachet and frequencies | |||||

| 0 | 1773 | 581 | 32.77 | 1 | |

| 1 to 2 | 302 | 115 | 38.08 | 1.26(0.98,1.62) | 0.071 |

| 3 | 201 | 69 | 34.33 | 1.07(0.79,1.46) | 0.656 |

| 4 or more | 2174 | 558 | 25.67 | 0.71(0.62,0.81) | < 0.001 |

| Is able identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding | |||||

| No | 2483 | 697 | 28.07 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1967 | 626 | 31.83 | 1.20(1.05,1.36) | 0.007 |

| Is able identify to the first complementary food which should be consumed by infants | |||||

| No | 4225 | 1246 | 29.49 | 1 | |

| Yes | 225 | 77 | 34.22 | 1.24(0.94,1.65) | 0.131 |

| Has know the optimum food of supplementary iron | |||||

| No | 3185 | 939 | 29.48 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1265 | 384 | 30.36 | 1.04(0.91,1.20) | 0.565 |

| Is able identify nutrient relate to anemia | |||||

| No | 2522 | 772 | 30.61 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1928 | 551 | 28.58 | 0.91(0.80,1.03) | 0.142 |

| Is able identify the optimum timing of breastfeeding | |||||

| No | 3852 | 1151 | 29.88 | 1 | |

| Yes | 598 | 172 | 28.76 | 0.95(0.78,1.145) | 0.578 |

Breastfeeding in the past 24 h was correlated with anemia (OR = 2.30, P < 0.001). Compared to children who did not consume a sugary drink in the past 24 h, those who did consume a sugary drink had a decreased risk of anemia (OR = 0.79, P = 0.001). Compared to no addition of infant formula in the past 24 h, addition of infant formula once or twice, three times, and four times or more decreased the risk of anemia (OR = 0.56, 0.59, 0.73 and P < 0.001, < 0.001, 0.004, respectively). Compared to no addition of milk powder in the past 24 h, addition of milk powder once or twice decreased the risk of anemia (OR = 0.60, P < 0.001). Compared to no addition of a nutrient sachet in the previous week, addition of a nutrient sachet once or twice increased the risk of anemia (OR = 1.26, P = 0.071), while addition of a nutrient sachet four or more times decreased the risk of anemia (OR = 0.071, P < 0.001). The ability of caregivers to identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding was significantly associated with anemia (OR = 1.20, P = 0.007).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis

All variables with P < 0.10 in bivariate logistic regression analyses were entered into the multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 6). Compared to children 6 to 11 months of age, the risk of anemia among those 18 to 23 months of age decreased by 45% (OR = 0.55, P < 0.001). Compared to children with Han mothers, those with Miao mothers had a 1.23-fold increased risk of anemia (OR = 1.23, P = 0.044). Compared to children with Han fathers, those with Miao fathers had a 1.31-fold increased risk of anemia (OR = 1.31, P = 0.013) and those with Dong fathers had an 18% decreased risk (OR = 0.82, P = 0.047). Having diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks increased the risk of anemia 1.35-fold (OR = 1.35, P = 0.003).

Table 6.

Multivariate regression analysis of anemia among children 6 to 23 months of age

| Parameters | OR(95.0% C.I) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Boys | 1 | |||

| Girls | 0.93(0.81,1.07) | 0.317 | ||

| Age | ||||

| 6~ 11 months | 1 | |||

| 12~ 17 months | 0.84(0.70,1.00) | 0.053 | ||

| 18~ 23 months | 0.55(0.45,0.67) | < 0.001 | ||

| Mother’s ethnicity | ||||

| Han | 1 | |||

| Dong | 0.83(0.67,1.02) | 0.069 | ||

| Miao | 1.23(1.01,1.51) | 0.044 | ||

| Others | 0.98(0.71,1.35) | 0.894 | ||

| Mother’s educational Level | ||||

| Primary | 1 | |||

| Junior | 0.97(0.75,1.25) | 0.804 | ||

| Senior | 1.03(0.77,1.39) | 0.838 | ||

| University | 0.84(0.54,1.29) | 0.423 | ||

| Mother’s occupation | ||||

| Homemakers | 1 | |||

| Professionals | 0.96(0.61,1.51) | 0.866 | ||

| Commerce | 1.02(0.70,1.48) | 0.936 | ||

| Animal husbandry and fishery | 1.46(1.16,1.83) | 0.081 | ||

| Operators equipment | 0.99(0.54,1.80) | 0.967 | ||

| Others | 0.84(0.63,1.11) | 0.221 | ||

| Father’s ethnicity | ||||

| Han | 1 | |||

| Dong | 0.82(0.67,1.00) | 0.047 | ||

| Miao | 1.31(1.06,1.61) | 0.013 | ||

| Others | 1.14(0.80,1.62) | 0.475 | ||

| Father’s educational level | ||||

| Primary | 1 | |||

| Junior | 0.85(0.65,1.13) | 0.266 | ||

| Senior | 0.86(0.63,1.18) | 0.339 | ||

| University | 0.79(0.52,1.19) | 0.257 | ||

| Father’s occupation | ||||

| Homemakers | 1 | |||

| Professionals | 1.23(0.89,1.68) | 0.206 | ||

| Commerce | 1.00(0.72,1.40) | 0.980 | ||

| Animal husbandry and fishery | 0.85(0.65,1.09) | 0.198 | ||

| Operators equipment | 0.95(0.68,1.33) | 0.768 | ||

| Others | 1.09(0.84,1.41) | 0.512 | ||

| Caregiver’s groups | ||||

| Mothers | 1 | |||

| Fathers | 0.56(0.25,1.24) | 0.153 | ||

| Grandparents | 0.86(0.72,1.02) | 0.085 | ||

| Others | 0.50(0.10,2.40) | 0.386 | ||

| Diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.35(1.11,1.65) | 0.003 | ||

| Breastfeeding | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.50(1.26,1.80) | < 0.001 | ||

| Consume sugary drink | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.95(0.82,1.10) | 0.495 | ||

| Consume infant formula and frequencies | ||||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 to 2 | 0.72(0.61,0.85) | < 0.001 | ||

| 3 | 0.70(0.56,0.87) | 0.001 | ||

| 4 or more | 0.75(0.60,0.96) | 0.020 | ||

| Consume milk powder and frequencies | ||||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 to 2 | 0.71(0.56,0.90) | 0.005 | ||

| 3 | 0.90(0.62,1.29) | 0.556 | ||

| 4 or more | 0.74(0.48,1.14) | 0.167 | ||

| Consume nutrient sachet and frequencies | ||||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 to 2 | 0.95(0.73,1.24) | 0.697 | ||

| 3 | 0.83(0.60,1.15) | 0.270 | ||

| 4 or more | 0.70(0.61,0.82) | < 0.001 | ||

| Is able identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.15(1.01,1.32) | 0.039 | ||

Children not breastfed in the past 24 h had a 1.50-fold greater risk of anemia than those breastfed (OR = 1.50, P < 0.001). Addition of milk powder once or twice in the previous 24 h decreased the risk of anemia by 29% (OR = 0.71, P = 0.005) compared to no addition of milk powder. Moreover, addition of infant formula once or twice, three times, and four or more times in the previous 24 h decreased the risk of anemia by 28, 30, and 25% compared to no addition of infant formula, respectively (OR = 0.72, 0.70, 0.75 and P < 0.001, 0.001, 0.020, respectively). Addition of a nutrient sachet four or more times in the previous week decreased the risk of anemia by 30% (OR = 0.70, P < 0.001) compared to no addition of a nutrient sachet. The risk of anemia for children whose caregivers were able to identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding was 1.15-fold higher than that of children whose caregivers were not (OR = 1.15, P = 0.039).

Discussion

Our findings revealed that almost 30% of children 6 to 23 months of age in Huaihua were anemic. The prevalence of anemia in our study is higher than the 4.54% of children under 2 years of age in Beijing [18], but lower than that in western rural areas of China (> 30%), such as 37.84% among children under 3 years of age in rural Tibet [19] and 64.7% among children 6 to 35 months of age in Yushu, Qinghai Province [20]. By contrast, the prevalence of anemia in children globally is 43%, and approximately 70% in Central and West Africa [21]. The burden of anemia in developed counties is much lower; 7–9% of children 1 to 3 years of age in the US [22] and 2–9% of children 6 to 39 months of age in Europe [23] are anemic.

In further analysis, the results show that mother and father of Miao ethnicity (OR = 1.23 and 1.31), diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks (OR = 1.35), breastfeeding in the prior 24 h (OR = 1.50), and caregivers able to identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding (OR = 1.15) had positive correlations with anemia. However, children aged 18 to 23 months (OR = 0.55), father of Dong ethnicity (OR = 0.82), addition of milk powder once or twice in the prior week (OR = 0.71), addition of infant formula once or twice, three times, and four or more times in the previous 24 h (OR = 0.72, 0.70, and 0.75), and addition of a nutrient sachet four or more times in the prior week (OR = 0.70) were negatively associated with anemia.

In our study, breastfeeding in the previous 24 h had a marked effect on the prevalence of anemia. A Chinese birth cohort study of the association between the duration of exclusive breastfeeding and infant anemia found that exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months was associated with an increased risk of anemia in infants 12 months of age [24]. The concentration of iron in human milk is relatively low, and so iron is supplied mainly from iron stores from birth until 6 months of age. However, iron stores are depleted after 6 months of age, the time at which iron demand increases because of rapid growth and development [25]. Therefore, the risk of anemia increases after 6 months of age in breastfed children; indeed, their risk is higher than that of children 18 to 23 months of age. Anemia in children 6 months of age is ameliorated by the intake of iron-rich foods, and their risk of anemia increases with age [19, 26].

Addition of milk powder or infant formula was associated with a decreased risk of anemia, likely because these have higher levels of minerals than breast milk. The production of powdered formulas was base on ordinary powdered, as iron has been added to powdered formulas to prevent anemia in recent decades [27].

Addition of a nutrient sachet four or more times in the previous week was significantly negatively associated with anemia. In rural areas of China, soybean powder-based micronutrient supplements (nutrient sachets) significantly reduced the burden of anemia among children 6 to 23 months of age. Consumption of four nutrient sachets weekly by infants is recommended in China. In this study, the risk of anemia in the 48.85% of the children who consumed a nutrient sachet four or more times weekly was 30% lower than that of those who did not consume any nutrient sachets. Zhouxun reported that the child’s age and ethnicity, the parents’ education and occupation, and adverse reactions to Yingyangbao were associated with taking Yingyangbao among children 6 to 23 months of age in poor rural areas of Hunan Province, China [28]. Therefore, provision of nutrient sachets reduced the burden of anemia among children in Huaihua; however, its implementation is unsatisfactory.

In this study, having parents of Miao ethnicity was associated with an increased risk of anemia, and a father of Dong ethnicity with a reduced risk of anemia. This is in agreement with several prior reports. For example, Luoyan reported that the prevalence of anemia in children of Kazakh ethnicity is higher than in those of Han ethnicity, which is likely due to the unique habitats and customs of minority ethnicities [29]. Therefore, health education in areas inhabited by minority ethnicities needs to be strengthened. In Yunnan Province, the risk of anemia among children of Li ethnicity is 1.9-fold greater than that of those of Han ethnicity due to Mediterranean anemia [30].

Of the children, 12.20 and 18.58% had experienced diarrhea and fever in the previous 2 weeks. Wuxiao-jian reported that the 2-week prevalence of diarrhea and fever among children less than 3 years of age is associated with socioeconomic status, healthcare during pregnancy and the puerperal period, and mothers’ knowledge of disease prevention [31]. Children with a history of diarrhea during the past 2 weeks were more likely to be anemic than children without diarrhea because of loss of appetite and malabsorption of nutrients in the intestine. Similar findings have been reported by studies conducted in Indonesia [32, 33].

The ability of the caregiver to identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding increased the risk of anemia in this study. Caregivers’ level of knowledge of nutrition and feeding may influence the feeding behavior of children [34, 35]. Although 44.20% of the caregivers were able identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding, only 5.06% were able identify to first complementary food which should be consumed by infants. A lack of knowledge of feeding practices among caregivers may explain the link between their ability to identify the optimum timing of complementary feeding and the risk of anemia.

This study had several limitations that should be taken into consideration. The cross-sectional design of this study prevents determination of the causality of the associations of factors with anemia. Further, the lack of information on family income, prenatal maternal anemia status, birth interval, and the timing of complementary feeding hampered analysis of the factors associated with anemia in children 6–23 months of age. However, this study involved 4500 children in a large geographic area (six regions of Huaihua), and considered caregivers’ knowledge of feeding practices and nutrition. Our findings clarify the prevalence and risk factors of anemia among children 6–23 months of age in Huaihua, and will facilitate the development of countermeasures to reduce the burden of anemia.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the prevalence of anemia among children 6 to 23 months of age in Huaihua was higher than that in more developed regions of China, and represents a considerable healthcare burden. The feeding practice of caregivers was associated with anemia. In addition, diarrhea, parents’ ethnicity, and caregivers’ level of knowledge of nutrition were associated with anemia. Therefore, nutrition improvement projects are needed to reduce the burden of anemia among children in Huaihua.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank maternal and child health care hospital of Yuangling, Mangyang, Xupu, Chenxi, Zhijiang, Huitong, Xinghuang to collected the data.

Funding

Self-funded.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- COR

Crude odds ratio

Authors’ contributions

ZH, FJ and JL conceived the research idea. ZH collected the data, performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. TX, DJ and JZ participated in data acquisition, analysis, and reviewed the draft manuscript. FJ and JL provided the critical review of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was signed by caregiver of children before the interview. The project was approved by Huaihua Women’s Federation and Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (No. 201563).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhi Huang, Email: hhsfbyzhige@hotmail.com.

Fu-xiang Jiang, Email: hhsfby@126.com.

Jian Li, Email: weijianzhige@sina.com.

Dan Jiang, Email: 2464871791@qq.com.

Ti-gang Xiao, Email: 1061647935@qq.com.

Ju-hua Zeng, Email: 570327445@qq.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Vitamin and mineral nutrition/Anemia. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . The global prevalence of anemia in 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benoist BD, Cogswell EM MLEI, Wojdyla D. Worldwide Prevalence of Anemia 1993–2005: WHO Global Database on Anemia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mclean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, Debenoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anemia, WHO vitamin and mineral nutrition information system, 1993–2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(4):444–454. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health . The Nutrition Development Report of Chinese Children Aged 0–6 (2012) Beijing: Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thankachan P, Muthayya S, Walczyk T, Kurpad AV, Hurrell RF. An analysis of the etiology of anemia and iron deficiency in young women of low socioeconomic status in Bangalore, India. Food Nutr Bull. 2007;28:328–336. doi: 10.1177/156482650702800309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollitt E. Early iron deficiency anemia and later mental retardation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(1):4–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cusick SE, Georgieff MK. The role of nutrition in brain development: the golden opportunity of the “first 1,000 days”. J Pediatr. 2016;175:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter RC, Jacobson JL, Burden MJ. Iron deficiency anemia and cognitive function in infancy. Pediatrics. 2010;126:427–434. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C. Maternal and child under-nutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Te Lancet. 2008;371:340–357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hipgrave DB, Fu X, Zhou H, Jin Y, Wang X, Chang S, Scherpbier RW, Wang Y, Guo S. Poor complementary feeding practices and high anemia prevalence among infants and young children in rural central and western China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68:916–924. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong CX, Ge PF, Zhang CJ, Ren XL, Fan HQ, Zhang YR ZJ, Xi JE. Effects of different feeding practices at 0–6 months and living economic conditions on anemia prevalence of infants and young children. J Hyg Res. 2013;42:596–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasricha SR, Black J, Muthayyaetal S. Determinants of anemia among young children in rural India. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e140–e149. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desalegn A, Mossie A, Gedefaw L, Schooling CM. Nutritional iron deficiency anemia: magnitude and its predictors among school age children, Southwest Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shet A, Mehta S, Rajagopalan N. Anemia and growth failure among HIV-infected children in India: a retrospective analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huo JS, Sun J, Fang Z. Effect of home-based complementary food fortification on prevalence of on anemia among infants and young children aged 6 to 23 months in rural poor region of China[J] Food Nutr Bull. 2015;36(4):405–414. doi: 10.1177/0379572115616001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun QN, Sun J, Jia XD. The intervention effect of community-based complementary food supplement (Ying yang bao) to infants and young children in China: a review. J Hyg Res. 2015;44(6):970–977. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuang X, Run SJ, Duan JH. The anemia status of children aged 0 to 6 years from 1998 to 2007 in Beijing. Chinese Journal of Child and Woman Health Research. 2010;21(4):412–414. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Su XG, Wang C. The status of anemia and associated factors among children under 3 years in 4 provinces rural of central and Western China. Chinese Journal Health Education. 2013;29(5):390–393. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu YY. Malnutrition and anemia among children under 3 years in Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Yushu in 2012. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care. 2013;23(9):986–988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engle-Stone R, Aaron GJ, Huang J, Wirth JP, Namaste SM, Williams AM. Predictors of anemia in preschool children: biomarkers reflecting inflammation and nutritional determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:402S–415S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.142323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carla C. Iron Nutriture of the fetus, neonate, infant, and Child. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;71(suppl 3):8–14. doi: 10.1159/000481447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domellöf M, Braegger C, Campoy C. Iron requirements of infants and toddlers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58(1):119–129. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang FL, Liu HJ, Prolonged Exclusive WY, Breastfeeding Duration I. Positively associated with risk of Anemia in infants aged 12Months. J Nutr. 2016;146:1707–1713. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.232967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai SF, Chen SJ, Yen HJ, Hung GY, Tsao PC, Jeng MJ, Lee YS, Soong WJ, Tang RB. Iron deficiency anemia in predominantly breastfed young children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2014;55:466–469. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joo EY, Kim KY, Kim DH, Lee JE, Kim SK. Iron deficiency anemia in infants and toddler. Blood Res. 2016;51:268–273. doi: 10.5045/br.2016.51.4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang SP, Ren FZ, Luo J, Peng HX, Wang YH. Progress in infant formula Milk powder. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery. 2015;46(4):200–210. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou X, Fang JQ, Luo JY, Wang H, Du QY. Factors associated with taking Yingyangbao efficiently among Infants Young Child aged 6–24 months in poor rural areas of Hunan Province,China. J Hyg research. 2017;46(2):256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo Y, Zhou P. Analysis on the causes of nutritional iron deficiency anemia in one year old children of Kazak nationality. Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 2011;26(23):3575–3577. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zu HP, Rao YH, Pan LC, Huang WM, Fang WM, Wu Y, Du YK. Analysis on the current situation and effect factors of anemia among the children under six years in rural areas of Hainan province. Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 2012;27(6):886–889. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu XJ. The two-week prevalence rates and risk factors of common cold and diarrhoea for children under 3 across 45 countries of western China.Master thesis, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and. Prevention. 2008; In Chinese.

- 32.Semba RD, Pee S, Ricks MO, Sari M, Bloem MW. Diarrhea and fever as risk factors for anemia among children under age five living in urban slum areas of Indonesia. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(1):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howard CT, Pee S, Sari M, Bloem MW, Semba RD. Association of diarrhea with anemia among children under age five living in rural areas of Indonesia. J Trop Pediatr. 2007;53(4):238–244. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmm011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng R, Luo JY, Tan C, Du QY, Zhang WM, Li YP. Relationship between caregivers’ nutritional knowledge and children’s dietary behavior in Chinese rural areas. J Cent South Univ. 2012;37(11):1097–1103. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gui XC, Ju KM. Relationship between the nutrition knowledge level of parents and nutritional status of their children in Shanghai. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2003;24(6):755–756. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.