SUMMARY

Mutations in CEP290 cause ciliogenesis defects, leading to diverse clinical phenotypes, including Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). Gene therapy for CEP290-associated diseases is hindered by the 7.4 kb CEP290 coding sequence, which is difficult to deliver in vivo. The multi-domain structure of the CEP290 protein suggests that a specific CEP290 domain may complement disease phenotypes. Thus, we constructed AAV vectors with overlapping CEP290 regions and evaluated their impact on photoreceptor degeneration in Cep290rd16/rd16 and Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice, two models of CEP290- LCA. One CEP290 fragment (the C-terminal 989 residues, including the domain deleted in mutant mice) reconstituted CEP290 function and resulted in cone preservation and delayed rod death. The CEP290 C-terminal domain also improved cilia phenotypes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and iPSC-derived retinal organoids carrying the Cep290rd16 mutation. Our study strongly argues for in trans complementation of CEP290 mutations by a cognate fragment and suggests therapeutic avenues.

In Brief

CEP290 mutations are the leading cause of Leber congenital amaurosis, a devastating inherited blindness. Mookherjee et al. show that the in-frame deletion of Cep290 in rd16 mice can be complemented by expressing a cognate protein fragment in trans, suggesting a new avenue for therapy development of CEP290 mutations.

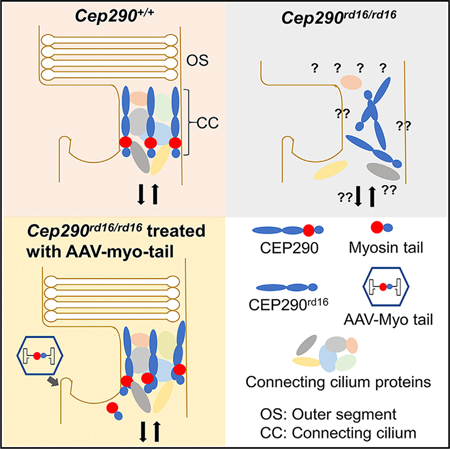

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

CEP290 plays an important role in the development, maturation, and normal functioning of cilium, a cellular organelle involved in multiple biological processes, including motility, sensory perception, and signaling (Betleja and Cole, 2010; Rachel et al., 2012a). Mutations in the CEP290 gene can lead to defects in cilia formation and function, manifesting as a diverse class of congenital diseases termed ciliopathies (Baala et al., 2007; Braun and Hildebrandt, 2017; Sayer et al., 2006; Valente et al., 2006). Patients with CEP290 mutations exhibit a spectrum of devastating phenotypes, from Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), a disease primarily characterized by early-onset retinal degeneration, to Meckel-Gruber syndrome (MKS), with multi-organ involvement and lethality. Although the genotype-phenotype relations are not fully understood, the severity of CEP290-associated phenotypes appears to correlate with the residual amount of functional protein that a mutant allele could produce (Drivas et al., 2015; Shimada et al., 2017).

Developing a treatment for multi-organ disease is challenging; therefore, therapy development for CEP290 ciliopathies would conceivably start with LCA, which afflicts the retina and other sensory systems. LCA patients usually present rapidly progressing vision loss within 1 year after birth and become blind in early childhood. Of the 25 genes identified (https://sph.uth.edu/Retnet/sum-dis.htm), CEP290 mutations account for 15%–30% of all LCA cases (Coppieters et al., 2010; den Hollander et al., 2006). A viable treatment option appears to be gene replacement, which has met with some success in LCA caused by RPE65 mutations (Apte, 2018). However, the CEP290 coding sequence is ~7.4 kb, greatly exceeding the packaging limit of an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector, the most efficient gene delivery tool to target photoreceptor disease. In principle, two fragments of a large gene can be co-delivered by separate AAV vectors, which can then be rejoined post-delivery through recombination mechanisms; however, the efficiency of expressing full-length proteins varied greatly among different studies (Chamberlain et al., 2016). The dual vector approach has yet to be tested successfully for the delivery of CEP290. In lieu of gene replacement, antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) and CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing have shown promise for correcting aberrant splicing of a deep intronic mutation (c.2991 + 1655A > G) (Garanto et al., 2016; Gérard et al., 2015; Ruan et al., 2017), the most common CEP290-LCA mutation generating a cryptic splice donor site (den Hollander et al., 2006). However, functional improvement has not been demonstrated in vivo by these approaches due to the lack of animal models that faithfully mimic the aberrant splicing in photoreceptors (Garanto et al., 2013). In fact, a long-lasting phenotype rescue has not been reported in any existing models with pathogenic mutations of Cep290 following post-natal intervention.

Outer segments (OSs) of retinal photoreceptors are specialized sensory cilia that contain the phototransduction apparatus and convert light to neural signals. No OS structure is observed in mice carrying a Cep290-null mutation, and only rudimentary OSs were detected in a hypomorphic mutant (rd16, or Cep290rd16/rd16), indicating the requirement of CEP290 for OS biogenesis (Chang et al., 2006; Rachel et al., 2015). In photoreceptors, CEP290 protein localizes at the connecting cilia (CC), the only intracellular link between light-sensing OS and the biosynthetic inner segments (ISs). It is essential for the integrity of the transition zone and plays critical roles in regulating protein trafficking between ISs and OSs through interactions with a number of ciliary proteins (Betleja and Cole, 2010; Chang et al., 2006; Rachel et al., 2012a). CEP290 directly binds to cellular membranes through its N-terminal domain, which includes a highly conserved amphipathic helix motif, and to micro-tubules through a region located within its myosin-tail homology domain (Drivas et al., 2013). The microtubule-binding domain overlaps with the BBS6 (or MKKS) protein-interacting domain that is deleted in frame (amino acids [aa] 1606–1904, termed deleted in sensory dystrophy [DSD]) in the naturally occurring rd16 allele of mouse Cep290 (Rachel et al., 2012b). In addition, autoinhibitory domains within N and C termini of CEP290 have been identified and are capable of regulating ciliogenesis (Drivas et al., 2013). Expression of an N-terminal region of human CEP290 or the missing DSD domain in the rd16 allele partially corrected the disease phenotypes in zebrafish induced by Cep290 antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (Baye et al., 2011; Murga-Zamalloa et al., 2011), suggesting the potential of using a CEP290 fragment to treat CEP290 ciliopathies. More recently, a ‘‘mini’’ human CEP290 fragment (aa 580–1180) was reportedly able to delay photoreceptor death in Cep290rd16/rd16 mice (Zhang et al., 2018), although the treatment outcome appeared to be suboptimal.

To examine whether a partial CEP290 coding sequence could complement CEP290 mutations, we designed and produced AAV vectors expressing a series of truncated CEP290 protein fragments and tested these in the Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— double mutant mouse line. In this mouse line, all retinal photoreceptors are cones due to the ablation of the neural retina leucine zipper (NRL), a transcription factor that specifies rod cell fate during retinal development (Cideciyan et al., 2011; Mears et al., 2001). The double mutant mice exhibited rapid cone dysfunction but maintained a relatively long period of cone cell body survival, modeling the changes in the foveal cones of CEP290-LCA patients (Boye et al., 2014). Here, we show that the AAV myo-tail vector encoding a C-terminal CEP290 fragment containing the myosin-tail homology domain (encompassing the domain deleted in the rd16 mice) is capable of preserving cone function and viability in the mutant mice. Our results indicate that some CEP290 mutations could be complemented in trans by a portion of the CEP290 protein and suggest a new avenue for therapy development in CEP290 ciliopathies.

RESULTS

Progression of Retinal Impairment in Cep290rd16/rd16; Nrl—/— Mice

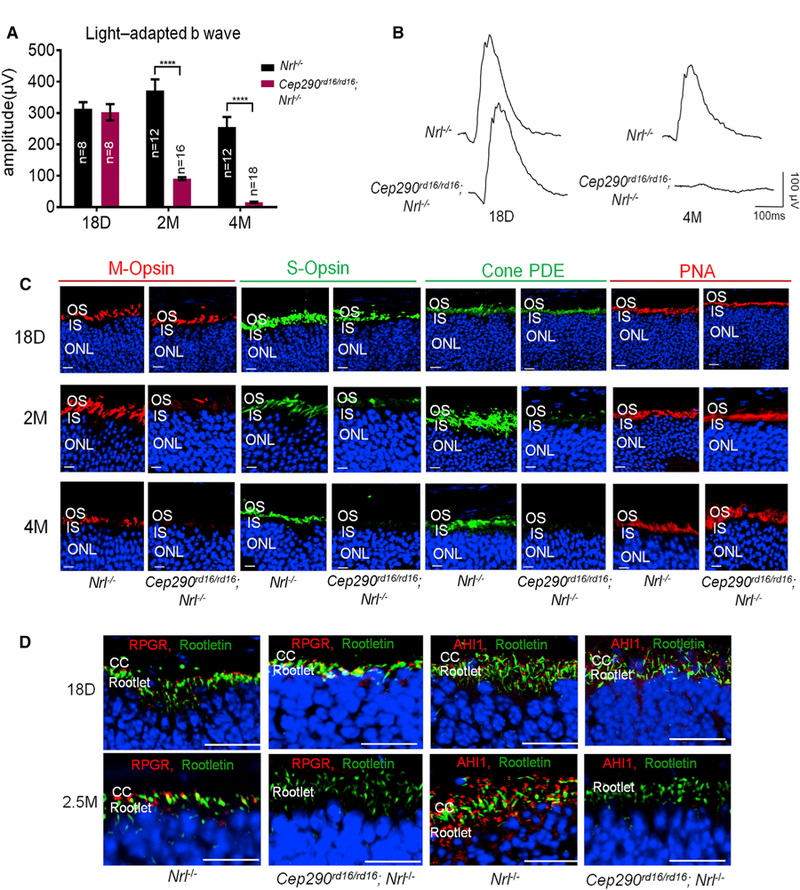

Despite compromised function, foveal cones in patients with CEP290-LCA usually survive for an extended period (Boye et al., 2014; Cideciyan et al., 2011). The disease manifestations are recapitulated in the Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice that possess a cone-only retina. Electroretinogram (ERG) response of these mice is abolished by 3 months of age, with concomitant loss of cone OS proteins (Boye et al., 2014). However, decline in the thickness of the photoreceptor layer is relatively slow, with ~80% remaining. To extend these observations, we monitored ERG changes in the mice between postnatal day 18 (P18) and 4 months and examined a few phototransduction and ciliary proteins (Figure 1). Cone-only Nrl—/— mice (Mears et al., 2001) with the normal Cep290 alleles were used as controls. At P18, no difference was observed between Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— and Nrl—/— mice in light-adapted ERG amplitudes and expression and localization of phototransduction proteins, including S-opsin, M-opsin, and cone phosphodiesterase (PDE). However, ERG amplitudes of Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice declined rapidly between P18 and 2 months and were completely extinguished at 4 months, in striking contrast to the substantially maintained amplitudes of age-matched Nrl—/— mice (Figures 1A and 1B). The phototransduction proteins were concomitantly diminished during the same period and were almost undetectable at 4 months in Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice, while they were well preserved in Nrl—/— mice (Figure 1C). However, peanut agglutinin (PNA) staining did not reveal obvious differences between the two mouse lines at any time point, indicating that the cone matrix sheath was not severely affected. Two cilia proteins, RPGR and AHI1, which reportedly interact with CEP290 directly or indirectly (Chang et al., 2006; Coppieters et al., 2010; Hsiao et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2008), appeared normally expressed and localized at CC at P18 but were barely detectable at 2.5 months in Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice (Figure 1D). These results suggest that the hypomorphic mutant CEP290rd16 protein permits relatively normal ciliogenesis and protein trafficking at early time points but that later CC structure is perturbed, possibly due to altered interactions with other cilia proteins. Compared with the cone-only Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice, the Cep290rd16/rd16 mice display a much earlier onset and more rapid retinal dysfunction and degeneration (Figure S1).

Figure 1. Natural History of Disease Progression of Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— Mice.

(A)Light-adapted b-wave of ERG response with a stimulus intensity of 2 log cd.s.m—2 from mice of different ages. Nrl—/— mice were used as controls. The number of mice in each group is indicated in the graph. ERG amplitudes from Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— and Nrl—/— mice were compared by two-tailed t test and are represented as means ± SEMs. ****p < 0.0001.

(B) Representative light-adapted ERG traces from an Nrl—/— and a Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mouse at 18 days and 4 months of age.

(C) Representative confocal images of M-opsin, S-opsin, cone PDE, and PNA staining of retinal sections. Progressive loss of M- and S-opsin and cone PDE signals with increasing age was observed in Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice.

(D) Representative confocal images of RPGR and AHI1 staining of the retinal sections. Loss of RPGR and AHl1 signals from retinal sections of older mice was observed.

Scale bars, 20 µm. CC, connecting cilia; IS, inner segment; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segment.

See also Figure S1.

Generation of AAV Vectors Carrying Cep290 Fragments

We generated expression constructs encoding four mouse CEP290 fragments (Figures S2A, 2A, and 2B). The DSD vector contains the portion of the CEP290 coding sequence deleted in the rd16 allele (aa 1606–1904). The myo-tail vector encodes the myosin-tail homology domain of the CEP290 protein along with the rest of the C-terminal region (aa 1491–2479). The C-terminal and N-terminal vectors carry sequences encoding the C-terminal (aa 1173–2479) and the N-terminal regions (aa 1–1059), respectively. The N-terminal human CEP290 fragment (aa 1–1059) was previously shown to rescue vision impairment in zebrafish caused by a Cep290 defect (Baye et al., 2011). Each of these four coding sequences contains a Myc (or hemagglutinin [HA]) tag at the N terminus and is driven by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. Immunoblotting analysis of HEK293 cells transfected with the DNA constructs revealed the expected molecular weight of each protein fragment, with the myo-tail construct exhibiting the strongest expression (Figure S2B). These DNA constructs were packaged into AAV type 8 (AAV8). Administration of the AAV8-myo-tail vector to Cep290rd16/rd16; Nrl—/— mice subretinally resulted in the stable expression of the myosin-tail protein (Figure 2C), which was localized to the CC of the photoreceptors (Figure 2D). However, none of the other three vectors led to detectable expression of corresponding proteins following injection, suggesting that either these proteins are unstable or they are otherwise poorly expressed in photoreceptors.

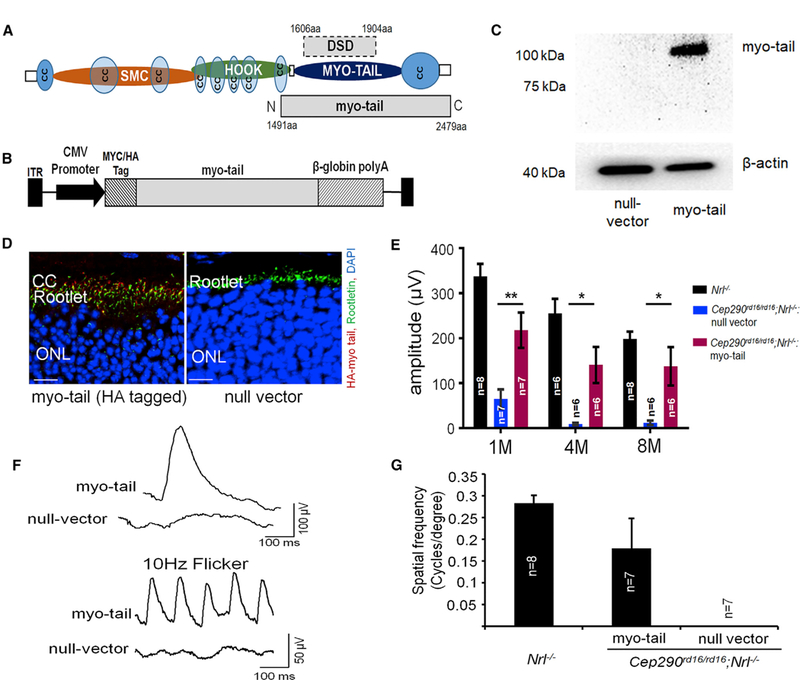

Figure 2. Preservation of Retinal Function and Visual Behavior in Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— Mice by AAV8-Myo-tail Vector.

(A) Schematic representation of the mouse CEP290 protein with predicted domains. Location of the myo-tail fragment and the DSD domain are shown. CC, coiled coil; myo-tail, myosin tail homology domain; SMC, structural maintenance of chromosome.

(B) Schematic representation of the AAV vector carrying the myo-tail expression cassette.

(C) Immunoblot using an antibody against Myc-tag showing myo-tail expression in the retinal lysate of Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice injected with AAV8-myc-myo- tail vector. β-Actin was used as loading control.

(D) Representative confocal images of retinal sections from Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice injected with AAV8-HA-myo-tail using an antibody against HA tag. The retinal sections were obtained at 2 months after vector injection. Expression of myo-tail can be seen at the CC region. Scale bars, 20 µm.

(E) Light-adapted b-wave of ERG response with a stimulus intensity of 2 log cd.s.m—2 from myo-tail or null vector injected eyes of Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/—. Age-matched Nrl—/— mice were used as controls. The number of mice used in each group is indicated in the graph. Data from myo-tail vector and null vector treated eyes were compared by a paired two-tailed t test and are represented as means ± SEMs. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

(F) Representative ERG traces from a single 8.5-month-old Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mouse treated with the myo-tail vector unilaterally. Null vector treated contralateral eye was used as a negative control. Flicker ERG traces, 10 Hz, are also shown.

(G) Optomotor response from Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice at 2 months after vector injection. These mice were injected with AAV8-myo-tail at 21 days of age unilaterally. The contralateral eyes were injected with a null vector. Age-matched Nrl—/— mice were used as controls. The number of mice used in each group is indicated in the graph. Error bars indicate SEM. The null vector treated eyes had no spatial resolution, whereas the vector treated eyes retained substantial responses.

See also Figures S2, S3, and S4.

Preservation of Retinal Function and Visual Behavior by the AAV-Myo-tail Vector

Each Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mouse received subretinal injection of one of the expression vectors in one eye and a null vector in the fellow eye at a dose of 1 × 109 vector genomes (vg). The null vector has a DNA fragment packaged into the AAV8 capsid, but it does not express any protein (Yu et al., 2017). The vectors were administrated at P14–P17 before obvious retinal pathology developed. Among the four vectors tested, the myo-tail vector displayed the most pronounced and long-lasting therapeutic effects. Eyes receiving this vector exhibited significantly higher light-adapted b-wave amplitudes than did control eyes throughout the entire 8-month monitoring period, with approximately 70% amplitude preserved as compared with age-matched Nrl—/— mice (Figure 2E). Preservation of S-cone function appeared to be better than that of M-cone function, as revealed by ERG responses elicited with spectrally selective stimuli (Figure S3). Flicker response was also well preserved. Representative ERG waveforms are shown in Figure 2F. Treatment with the other three vectors resulted in either a slight improvement or no improvement at all (Figure S2C) and was therefore not further pursued. Optomotor response of the myo-tail vector treated eyes was well maintained, with the average spatial frequency reaching approximately 60% of that of the Nrl—/— mice, which was in contrast to the lack of response in the control eyes (Figure 2G). These results indicate that the myo-tail vector can efficiently preserve retinal function and visual behavior of the Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice.

We then evaluated whether intervention at later stages (P35 and P52) would still provide therapeutic benefits. P35 represents an early stage of the disease when cone degeneration and dysfunction have already started, whereas severely compromised cone function and substantial loss of phototransduction and ciliary proteins are evident at P52 (Boye et al., 2014). In both instances, significantly higher ERG amplitudes and more cone proteins were detected in the myo-tail vector injected eyes than in the control eyes (Figures S4A and S4B), indicating a relatively wide treatment window. We must mention that the intervention at P52 resulted in suboptimal therapeutic effects, as reflected by less preservation of light-adapted ERG compared with earlier intervention. Administration with two other doses of the vector, 5 × 108 vg/eye and 2 × 109 vg/eye also demonstrated prominent functional preservation (Figure S4C).

Preservation of Photoreceptor Proteins and CC Structure by the AAV-Myo-tail Vector

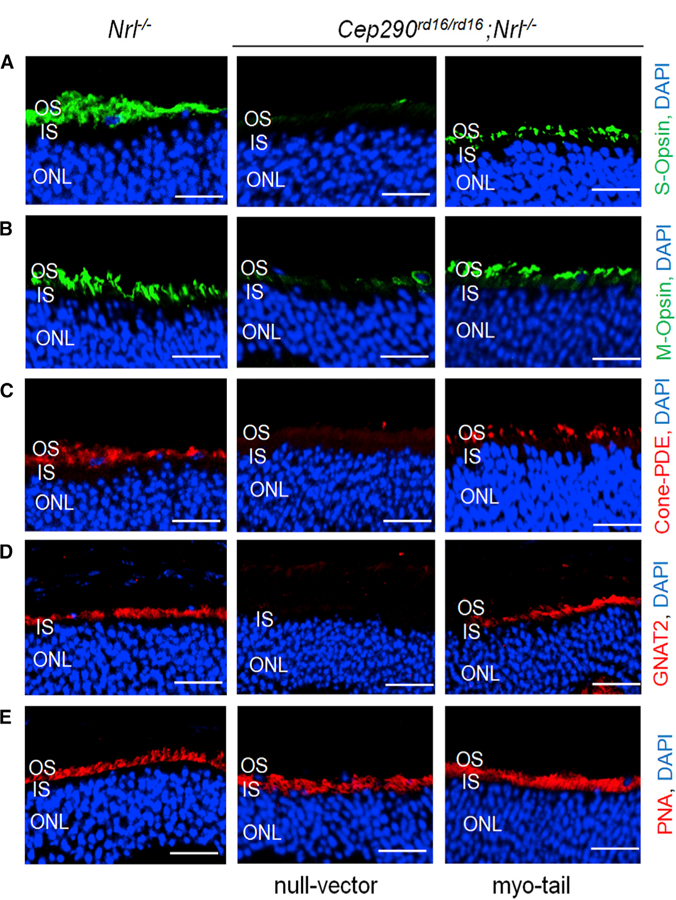

A nearly complete loss of cone proteins occurred in 4-month-old Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice (Figure 1C). With myo-tail vector treatment, phototransduction proteins, including M- and S-opsin, cone PDE, and GNAT2, were nearly normally expressed and localized at OS at 4 months post-injection (Figures 3A–3D). PNA staining again did not reveal obvious differences between Nrl—/— and Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice or treatment modalities (Figure 3E). The myo-tail vector treatment also resulted in nearly normal expression of RPGR, AHI1, and RPGRIP1 at CC (Figure 4A).

Figure 3. Preservation of Phototransduction Proteins in Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— Mice by AAV8-Myo-tail Vector.

Each mouse was injected with 1 × 109 vg AAV8-myo-tail vector in one eye and the same dose of a null vector in the fellow eye at P14. Representative confocal images of retinal sections from 4.5-month-old treated mice for S-opsin (A), M-opsin (B), cone PDE (C), GNAT2 (D), and PNA (E) are shown. Sections from an age-matched Nrl—/— mouse were used as controls. Expression of phototransduction proteins in the OS of retina were preserved in Cep290rd16/rd16; Nrl—/— mice following myo-tail treatment. Scale bars, 20 µm.

See also Figure S4

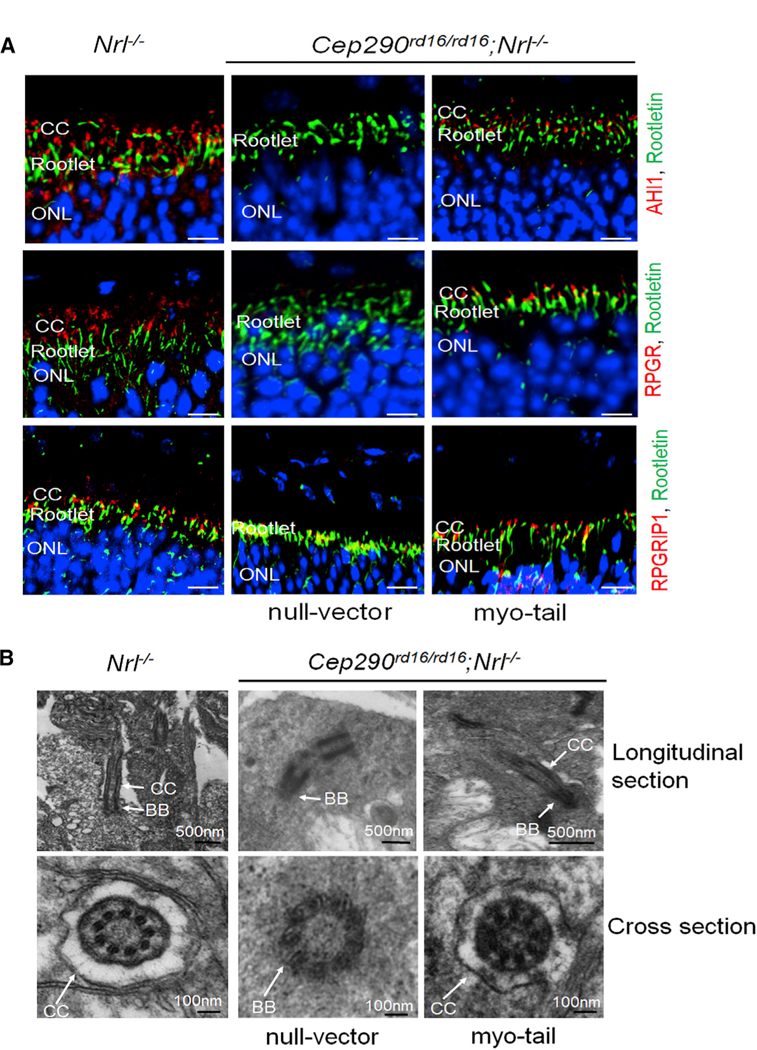

Figure 4. Preservation of Proteins and Structure of CC in Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— Mice by AAV8-Myo-tail Vector.

Each mouse was injected with 1 × 109 vg AAV8-myo-tail vector in one eye and the same dose of a null vector in the fellow eye at P14.

(A) Representative confocal images of retinal sections from 4.5-month-old Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice showing the preservation of AHL1, RPGR, and RPGRIP1 at CC following myo-tail vector treatment. Sections of an age-matched Nrl—/— mouse were used as controls. Scale bars, 20 µm.

(B) Representative images of transmission electron microscopy showing relatively normal connecting cilium structure with myo-tail vector treatment. No connecting cilium structure was found in eyes treated with the null vector.

BB, basal body; CC, connecting cilia.

An electron micrograph (EM) revealed a remarkable structural preservation of the CC in myo-tail vector treated retinas (Figure 4B). With the treatment, intact CC structure was observed in the photoreceptors of Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice, similar to those of the Nrl—/— mice. In contrast, only a basal body-like structure was observed without the adjoining CC in null vector treated retinas. Cross-sections through this region confirmed the presence of a membrane-bound CC structure in both myo-tail vector treated Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— and the Nrl—/— retina. Only micro-tubule bundles within the basal body were detected in the null vector treated retina.

Interdependency of the Myo-tail Fragment and the Endogenous CEP290rd16 Protein for Treatment

The Cep290rd16 allele is considered functionally hypomorphic (Chang et al., 2006; Rachel et al., 2015). We therefore examined whether the myosin-tail domain by itself or in combination with the endogenous CEP290rd16 protein is required to reconstitute CEP290 function. To obtain mice that were null for Cep290, we initially attempted to breed from Cep290+/— parental pairs but failed to obtain sufficient offspring. We therefore opted for the AAV-mediated triple gene delivery strategy to ablate with CRISPR (Yu et al., 2017) in the cones of Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice and concomitantly deliver the myo-tail domain to the same cells. S. pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) expression was controlled by a photoreceptor-specific rhodopsin kinase (RK) promoter in one AAV vector. A separate AAV vector carried a U6 promoter-driven single guide RNA (sgRNA) cassette targeting exon 3 of Cep290, together with the myo-tail expression cassette (Figures 5A and 5B). A control vector was also constructed to express sgRNA against the EGFP gene together with the myo-tail cassette. We validated this system by ablating the wild-type Cep290 gene in the retinas of Cep290+/—:Nrl—/— mice (Figure S5). Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice received concomitant delivery of the Cas9 vector and the myo-tail/sgRNA-Cep290 vector in the right eyes and co-injection of the Cas9 vector and the myo-tail/sgRNA-EGFP vector in the left eyes at P14 (Figure 5C). At 2 months post-injection, insertions and deletions (indels) at the targeted site in the Cep290 gene were detected only in the eyes receiving CRISPR-Cep290 treatment (Figure 5D). The amount of CEP290rd16 protein was significantly lower in CRISPR-Cep290 treated eyes (Figure 5E). We were not surprised that eyes receiving co-injection of the Cas9 vector and the myo-tail/sgRNA-EGFP vector displayed substantially preserved ERG amplitude (Figure 5F). In contrast, ERG amplitude in eyes receiving co-delivery of the Cas9 vector and the myo-tail/sgRNA-Cep290 vector was significantly lower, suggesting that both the myosin-tail domain and the endogenous mutant CEP290rd16 are required for functional rescue. Co-immunoprecipitation following transfection of HEK293 cells confirmed a direct interaction between the myosin-tail domain and CEP290rd16 (Figure 5G). These results suggest that the myosin-tail domain physically associates with CEP290rd16 in vivo and that the two proteins in combination reconstitute complete CEP290 function in the mutant retina.

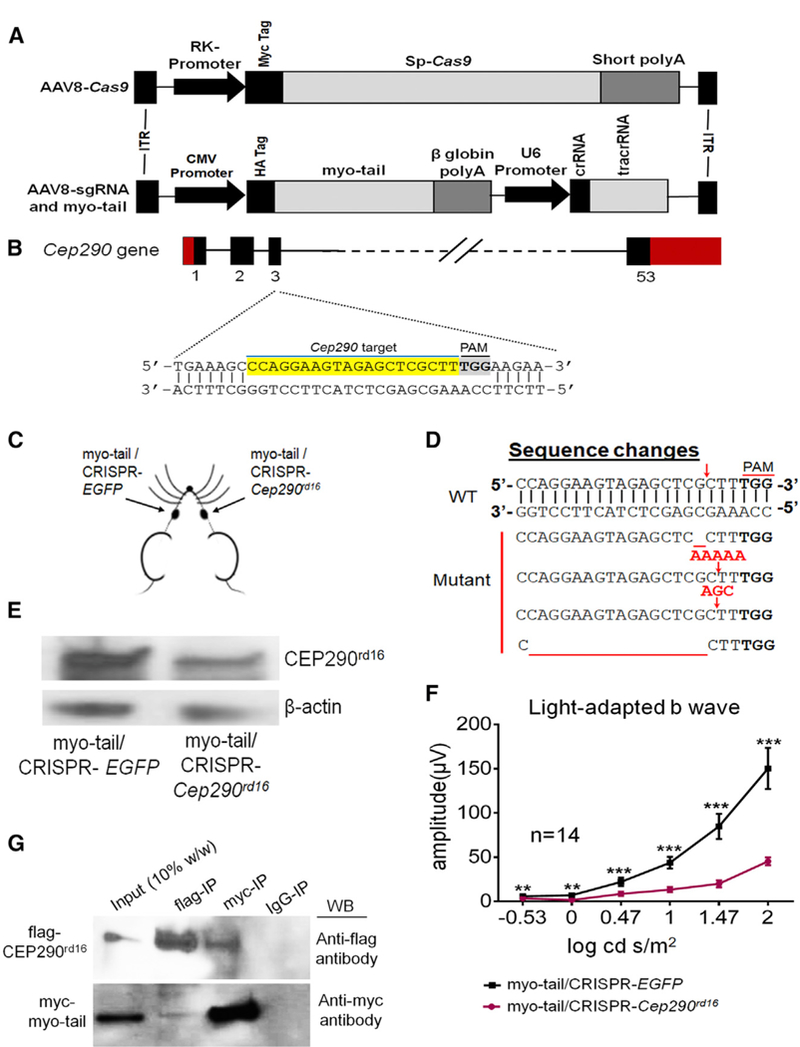

Figure 5. Interdependency of AAV-Expressed Myo-tail and Endogenous CEP290rd16 for Retinal Function Preservation in Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— Mice.

(A) Schematic of AAV vectors carrying spCas9 and sgRNA with myo-tail expression cassette.

(B) The sgRNA targets exon 3 of the mouse Cep290 gene. The targeted sequence is highlighted in yellow.

(C) Each mouse was injected with AAV8-Cas9 along with the vector carrying the myo-tail cassette and sgRNA targeting Cep290 in one eye, with AAV8-Cas9 together with myo-tail and sgRNA targeting EGFP in the fellow eye.

(D) Representative mutation patterns at Cep290 locus following CRISPR treatment. Top, WT sequence, with red arrow indicating the cleavage site; Bottom, mutated sequences, with red arrows representing insertions and red underlines indicating deletions.

(E) Immunoblots showing lower CEP290rd16 expression in the retinal lysate of mice receiving CRISPR-Cep290 treatment. b-Actin was used as a loading control.

(F) Light-adapted ERG response showing significantly higher b-wave amplitude in mice receiving CRISPR-EGFP and myo-tail than mice receiving CRISPR-Cep290 and myo-tail. The number of mice used is indicated in the graph. ERG amplitudes were compared by two-tailed paired t test and are represented as means ± SEMs. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

(G) Co-immunoprecipitation showing interaction of myo-tail and CEP290rd16 proteins. Myo-tail was tagged with Myc and CEP290rd16 was tagged with FLAG. These constructs were co-transfected into HEK293 cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc or anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitated proteins were detected either with anti-FLAG or anti-Myc antibody.

crRNA, CRISPR RNA; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitation; ITR, inverted terminal repeat; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif; tracrRNA, trans-activating crRNA; WB, western blot.

See also Figure S5.

Cell-Type Independent Complementation of the Cep290rd16 Mutation by the Myo-tail Vector

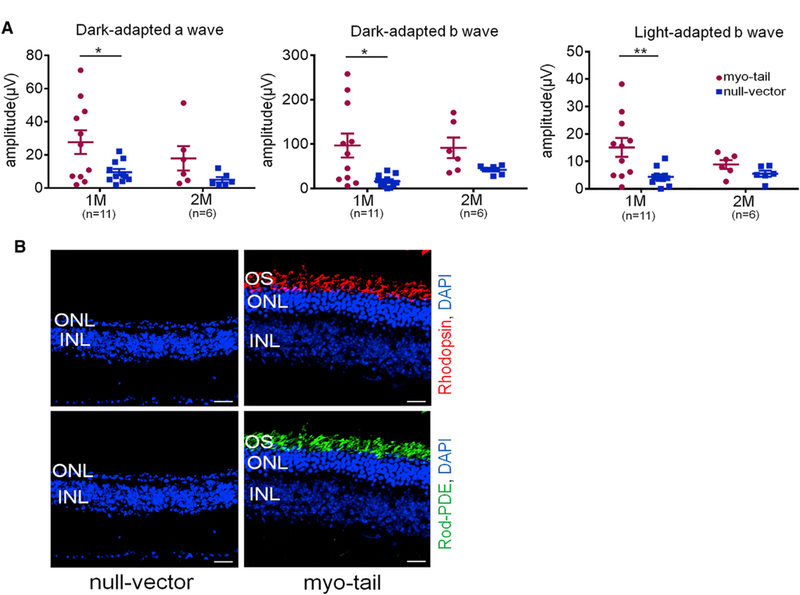

We next asked whether complementation of the Cep290rd16 mutation by the myo-tail vector is applicable to other cells and tissues. We evaluated whether the rapid rod degeneration in Cep290rd16/rd16 mice could be rescued by the vector. ERG amplitudes were significantly higher in the myo-tail vector treated eyes than those in the null vector treated eyes at 1 month post-injection (P38) (Figure 6A). The overall ERG amplitudes were still higher in myo-tail vector treated eyes at 2 months post-injection, although no longer statistically significant. The retinas receiving the myo-tail vector maintained much of their photoreceptor layers and rod-specific phototransduction proteins at P38, which were almost completely missing in the control retinas (Figure 6B). These results indicate that the myo-tail vector is able to partially complement the Cep290rd16 allele in rods despite the rapid kinetics of their degeneration.

Figure 6. Delayed Retinal Degeneration in Cep290rd16/rd16 Mice following AAV8-Myo-tail Treatment.

(A) Dark- and light-adapted ERG responses from Cep290rd16/rd16 mice at 1 and 2 months after treatment. Each mouse was injected with 2 × 109 vg/eye of AAV8-myo-tail unilaterally at P8. The contralateral eye was injected with the same dose of null vector as a control. The number of mice used is indicated in the graph. Statistical comparisons were conducted by paired t test. Error bars indicate SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

(B) Representative confocal images of rhodopsin and rod-PDE staining of retinal sections from treated mice at 1 month after vector injection. Scale bars, 20 µm.

See also Figure S6.

Cep290rd16/rd16 mice also display auditory and olfactory deficits (McEwen et al., 2007; Rachel et al., 2012b). To test whether the myo-tail vector could complement the mutation in cochlear hair cells, which are responsible for auditory sensation, the vector was injected into the posterior semicircular canal at P2 (Isgrig et al., 2017; Suzuki et al., 2017), and the mice were examined for auditory brainstem response (ABR) at 3 months of age. The mice displayed more severe auditory deficits when responding to higher frequency sound, because a significantly elevated ABR threshold was detected in all untreated mice when a 32-kHz stimulus was given (Figure S6A). However, two of the nine treated mice exhibited a remarkably lower threshold at 32 kHz, suggesting that the treatment improved their sensitivity to higher frequency sounds (Figure S6A). Although functional rescue was not statistically significant due to the inherent variability of the treatment to P2 mice (Isgrig et al., 2017; Suzuki et al., 2017), immunofluorescence analysis revealed more inner hair cells in treated cochlea than those of untreated cochlea (Figures S6B–S6D). The hair cells at the cochlear base are tonotopically tuned for high-frequency sounds (Davis and Silverman, 1970). Thus, the preservation of inner hair cells at the cochlear base with the myo-tail vector treatment explains the lower ABR threshold at high frequency. These results suggest that the myo-tail vector could complement the Cep290rd16 mutation in cochlear hair cells as well.

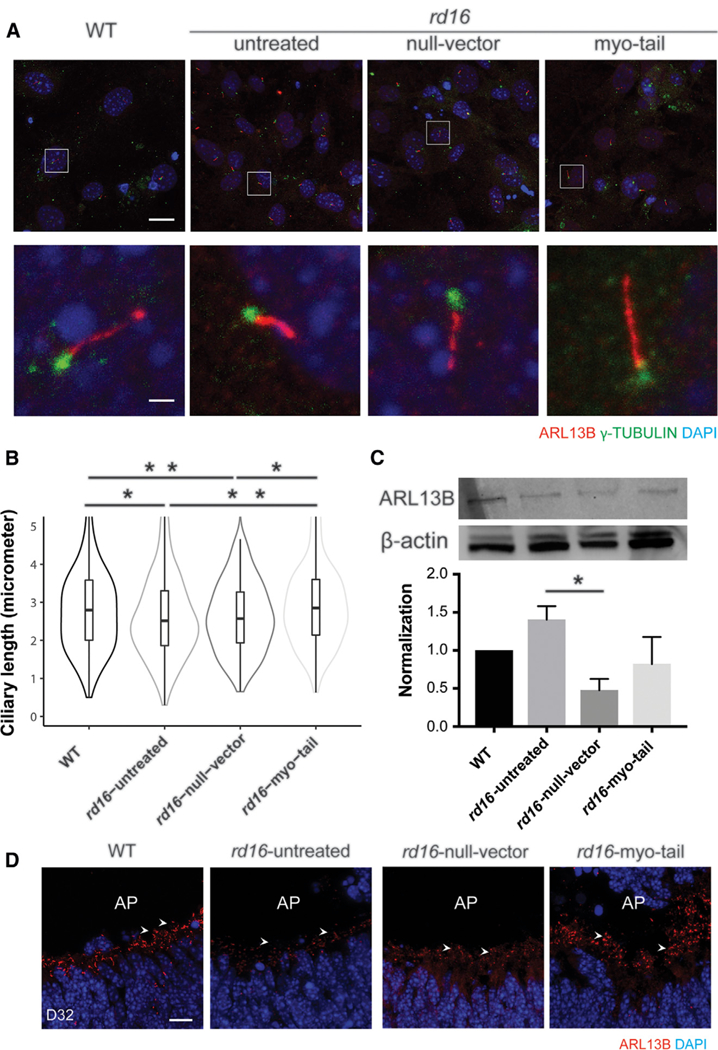

Rescue of In Vitro Models of Cep290rd16 Mutation by the Myo-tail Vector

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Cep290rd16/rd16 mice, which expressed a truncated CEP290 protein (Figure S7A), were reported to have shorter cilia compared to wild-type (WT) upon serum starvation (Burnight et al., 2014). We wanted to test whether the myo-tail vector could correct the cilia phenotype in rd16 MEFs. The AAV2 vectors demonstrated a higher transduction efficiency for MEFs compared to AAV8 and enabled efficient expression of the myosin-tail protein (Figures S7B and S7C). The expressed myosin-tail protein was transported to cilia rootlets and co-localized with basal bodies (Figure S7D). Upon serum starvation, cilia were detectable in WT, untreated, and vector transduced rd16 MEFs with ciliary axonemes (ADP ribosylation factor-like guanosine tri-phosphatase [GTPase] 13B [ARL13B] staining) protruding from basal bodies (g-tubulin staining) (Figure 7A). Although a lower percentage of cilia formation in rd16 primary dermal fibroblasts than in WT was reported (Drivas et al., 2013), we did not observe this change in rd16 MEFs (data not shown). rd16 MEFs had shorter cilia than WTs (Figure 7B), which is consistent with a previous study (Burnight et al., 2014). However, the myo-tail vector transduced rd16 MEFs harbored significantly longer cilia compared to untreated and null vector treated rd16 MEFs. The difference in ciliary length was not due to altered ARL13B expression, because no significant difference was detected among the four comparison groups, except between untreated and null vector treated rd16 MEFs (Figure 7C). Our data suggest that the CEP290 mutation in rd16 MEFs lead to defective ciliary structure, and expression of the myosin tail protein fragment partially rescue the ciliary length.

Figure 7. Restoration of Cilia Formation of Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts and Retinal Organoids Derived from Cep290rd16/rd16 Mice following Myo-tail Vector Treatment.

(A) Development of cilia upon serum starvation. ADP ribosylation factor-like guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) 13B (ARL13B; red) and γ-tubulin (green) are markers for the ciliary axoneme and basal bodies, respectively. White squares in row 1 indicate the zoomed-in region shown in row 2. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 50 µm (row 1); 10 µm (row 2).

(B) Violin plot displaying the ciliary length of the MEFs. Outliers are omitted for better display of the main population. The bars in the middle of the boxes indicate medians, and the upper and lower bars show +1 and —1 SDs, respectively. The width of the violins demonstrates frequency. The data consist of >3 independent experiments, with >80 cilia quantified blindly in each group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

(C)Immunoblotting to compare the expression of ARL13B. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The histogram shows the relative level of ARL13B in normalization against β-actin. Error bars indicate SEM. *p < 0.05.

(D)D 32 retinal organoids with infection of null vector or myosin-tail vector. AP indicates the apical side of neural retina. Arrowheads show relevant staining of ARL13B. Scale bar, 10 µm.

See also Figure S7.

Three-dimensional retinal organoids can be differentiated from mouse pluripotent stem cells and can provide a valuable in vitro platform for evaluating therapeutics (Chen et al., 2016; DiStefano et al., 2018). We optimized AAV transduction conditions, enabling the effective delivery of genes into retinal organoids (Figure S7E). By differentiation day (D) 32, cilia were evident in photoreceptors at the apical side of neural retina (Figure 7D). rd16 photoreceptors had dramatically fewer cilia, as shown by ARL13B labeling. Null vector treated rd16 photoreceptors had no significant morphological differences with untreated photoreceptors; however, treatment with the myo-tail vector showed restoration of photoreceptor ciliogenesis. Our data demonstrate the complementation of the Cep290rd16 mutation by the myosin-tail and provide support for using retinal organoids from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) as a platform for testing treatment candidates.

DISCUSSION

Mutations in the CEP290 gene are a leading cause of LCA and are associated with multiple distinct ciliopathies. AON and CRISPR/ Cas9 genome editing are being evaluated to correct the most common CEP290-LCA mutation, but in vivo therapeutic effects of these approaches remain unknown. Other treatment strategies, including modulating CEP290 interacting proteins (Rachel et al., 2012b) and inhibiting Raf-1 kinase inhibitory protein (Murga-Zamalloa et al., 2011; Subramanian et al., 2014), have been proposed but not validated through post-natal intervention. Here, we show that a C-terminal CEP290 fragment complements the Cep290rd16 mutation in trans by preserving photoreceptor cell viability and function and improving visual behavior in the Cep290rd16/rd16;/Nrl—/— mutant mice. The present study may represent the most efficacious treatment for retinal degeneration in a mammalian model carrying a pathogenic Cep290 mutation.

AAV-mediated delivery of miniaturized versions of dystrophin, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), and coagulation factor VIII has shown treatment benefits for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Gregorevic et al., 2006), cystic fibrosis (Cebotaru et al., 2008), and hemophilia A (McIntosh et al., 2013), respectively. These successful examples prompted us to examine shorter CEP290 fragments for rescuing CEP290-associated cilia phenotypes. However, because the structure-function correlation of CEP290 protein is less clear, a rational design of a ‘‘mini’’-CEP290 possessing full function appeared challenging. Maintaining known functional domains involved in protein interaction, membrane binding, and microtubule binding, but removing auto-regulatory domains, was predicted to result in a mini-CEP290 gene that is small enough to be delivered by a single AAV vector yet carry out complete functions (Drivas et al., 2013). Such a mini-CEP290 gene possessing the full function of CEP290 has not yet been reported. Recently, a mini-human CEP290 fragment was found to delay photoreceptor death in rd16 mice (Zhang et al., 2018). In the present study, we tested several truncated CEP290 fragments that represent various functional domains (N-terminal and DSD) or contain the missing portion in the Cep290rd16 mutation (DSD, myo-tail, and C-terminal). Only the 989-residue C-terminal fragment containing the myosin-tail homology domain (myo-tail) preserved the cone structure and function in the Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice. Other fragments failed to show any meaningful efficacy. Although the fragments produced cognate protein domains in HEK293 cells after transfection, very low or no protein was detected in the mouse retina following AAV-mediated gene delivery. Instability of the recombinant protein products in an in vivo photoreceptor setting appears to be a significant contributing factor for lack of complementation.

The myo-tail fragment, with many known functional domains excluded, is unlikely to possess the full function of CEP290. Co-existence of the endogenous CEP290rd16 protein is indispensable for functional preservation of cones in the myo-tail vector treated Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— mice (Figure 5). The Cep290rd16 mutation, with a deletion of a 299-residue-long coding sequence, is considered a hypomorph because the mutant mice manifest only sensory defects but no other ciliopathy phenotype. In photoreceptors, the CEP290rd16 protein allows relatively normal ciliogenesis, as evidenced by the formation of CC and rudimentary OS during post-natal development (Rachel et al., 2012b, 2015). However, it is not able to support normal structure and function, leading to rapid photo-receptor dysfunction and death in the Cep290rd16/rd16 mouse. CEP290 is proposed to be localized vertically along the length of the transition zone in the region of the Y-linkers, between the plasma membrane and the microtubule ring (Rachel et al., 2015). Structural integrity of the transition zone is compromised with the CEP290rd16 mutation, partly due to the absence of the microtubule-binding domain in the mutant CEP290rd16 protein (Drivas et al., 2013). Consequently, normal interactions could be altered with many other cilia proteins such as AHI1, RPGR, and RPGRIP (Figures 1D, 4A, and S1D), resulting in the exacerbation of structural and functional abnormalities at the transitional zone. Loss of direct physical interactions with the BBS6 protein because of the missing DSD domain in the CEP290rd16 protein (Rachel et al., 2012b) may also disrupt the link between CEP290 and BBSome. Given that the myo-tail fragment directly interacts with the mutant CEP290rd16 (Figure 5), we propose that the myo-tail fragment helps improve the integrity of the transitional zone structure by restoring the interactions with MKKS and other cilia proteins.

Nrl—/— mice possess a cone-only retina, mimicking the cone-only fovea (and broadly the cone-rich macula) region of a human retina (Mears et al., 2001). Foveal cones in CEP290- LCA patients do not show visual function but survive for an extended period, making them a potential target for gene-based therapies (Boye et al., 2014; Cideciyan et al., 2011). To determine the therapeutic window, we conducted vector administration at different stages of the disease. Although intervention at a later time point was still effective in preserving the visual function, early intervention provided a much better outcome, which is consistent with a number of preclinical studies of other inherited retinal diseases (Mookherjee et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2017). Our results also suggest that the therapy could only ‘‘preserve’’ the remaining retinal structure and function and is not be able to regenerate or restore normal retina.

Complementation of the Cep290rd16 mutation by the myo-tail vector may not be limited to photoreceptors, because the degenerating cochlear hair cells in Cep290rd16/rd16 mice also seemed to be preserved following the treatment. In addition, ciliary phenotypes were restored in MEFs and iPSC-derived retinal organoids carrying the mutation, suggesting a common role that the myo-tail may play in different tissues with CEP290rd16 background. It will be intriguing to see whether ol-factory defects presented in Cep290rd16/rd16 mice (McEwen et al., 2007) could also be corrected by the myo-tail vector treatment. To treat multi-organ involvement, a systemic vector delivery instead of local administration could be used. Because retinal degeneration is often presented as a common phenotype among many syndromic ciliopathies, treatment paradigms should initially target retinal degeneration, as the requirement for vector dose is low and the treatment effects can be easily monitored. Once effective for the retinal phenotype, this approach can be extended to the treatment of defects in other organs.

In the present study, the myo-tail vector was tested for complementation of the Cep290rd16 mutation in mice. Among almost 140 human CEP290 mutations identified so far, approximately 1/5 are located within the human counterpart of the DSD domain missing in the Cep290rd16/rd16 mice, and most of these are nonsense or frameshift. Recent studies have revealed that the exon containing a premature termination codon could be spliced out in some instances by nonsense-associated altered splicing (NAS) and/or basal exon skipping (BES), resulting in the generation of a near full-length CEP290 protein possessing partial function (Barny et al., 2018; Drivas et al., 2015). Although the total amount of the near full-length protein was suggested to correlate with disease severity, the skipped exon may also be critical for full CEP290 function. We surmise that patients with mutations within the human DSD domain would generate truncated CEP290 proteins that are similar to mouse CEP290rd16 by the NAS or BES mechanism, and these could be complemented by the myo-tail vector. In addition, mutations in other regions of CEP290 may also be complemented by cognate protein fragments provided in trans. Future investigations could focus on directly testing these hypotheses using model systems described in the present study.

STAR★METHODS

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse CEP290 | Proteintech Group | Cat#22490–1-AP; RRID: AB_10973679 |

| Anti-mouse CEP290 | A Swaroop (PI) (Chang et al., 2006) | N/A |

| Anti-mouse S-OPSIN | T Li (PI) (Sun et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Anti-mouse M-OPSIN | Millipore | Cat#AB5405; RRID: AB_177456 |

| Anti-mouse RHODOPSIN | T Li (PI) (Li et al., 1996) | N/A |

| Anti-mouse GNAT2 | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-390; RRID: AB_2279097 |

| Anti-mouse β-Actin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A5441; RRID: AB_476744 |

| Anti-mouse Cone PDE | T Li (PI) (Sun et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Anti-mouse Rod PDE | T Li (PI) (Sun et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Anti-mouse ROOTLETIN | T Li (PI) (Yang et al., 2002) | N/A |

| Anti-mouse RPGR | T Li (PI) (Hong and Li, 2002) | N/A |

| Anti-mouse AHI1 | Abcam | Cat#Ab93386; RRID: AB_10561623 |

| Anti-MYC Tag | Cell Signaling | Cat#2276; RRID: AB_331783 |

| Anti-HA Tag | Cell Signaling | Cat#2367; RRID: AB_331789 |

| Anti-mouse RPGRIP1 | T Li (PI) (Hong et al., 2001) | N/A |

| Anti-FLAG Tag | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A2220; RRID: AB_1006303 |

| Anti-FLAG Tag | Cell Signaling | Cat#2368; RRID: AB_2217020 |

| HRP-conjugated Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L); AffiniPure |

Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat#711035152; RRID: AB_10015282 |

| HRP-conjugated Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L); AffiniPure |

Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat#715035150; RRID: AB_2340770 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey anti-Chicken IgY (IgG) (H+L); AffiniPure |

Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat#703545155; RRID: AB_2340375 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) | Invitrogen | Cat#A21206; RRID: AB_141708 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Invitrogen | Cat#A21202; RRID: AB_141607 |

| Alexa Fluor 568 Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Invitrogen | Cat#A10037; RRID: AB_2534013 |

| Alexa Fluor 568 Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) | Invitrogen | Cat#A10042; RRID: AB_2534017 |

| Alexa Fluor 594 Lectin PNA from Arachis hypogaea | Invitrogen | Cat#L32459 |

| DAPI | Invitrogen | Cat#D1306; RRID: AB_2629482 |

| Anti-mouse IgG for IP (HRP) (veriblot antibody) | Abcam | Cat#131368 |

| VeriBlot for IP Detection Reagent (HRP) | Abcam | Cat#131366 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| NEB-10β | New England Biolab | Cat#C3019H |

| AAV8-CMV-MYC-MYO tail (mCep290) | This paper | N/A |

| AAV8-CMV-N-term (mCep290) | This paper | N/A |

| AAV8-CMV-C-term (mCep290) | This paper | N/A |

| AAV8-CMV-DSD (mCep290) | This paper | N/A |

| AAV8-CMV-HA-MYO tail (mCep290) | This paper | N/A |

| AAV2-CMV-MYC-MYO tail (mCep290) | This paper | N/A |

| AAV2-CMV-EGFP | This paper | N/A |

| AAV8-RK-Cas9 | Zhijian Wu (PI) (Yu et al., 2017) | N/A |

| AAV8-CMV-MYC-MYO tail (mCep290)-U6- sgRNA_EGFP |

This paper | N/A |

| AAV8-CMV-MYC-MYO tail (mCep290)-U6- sgRNA_mCep290 |

This paper | N/A |

| Critical Commercial Assays/Chemicals | ||

| Co-Immunoprecipitation kit | ActiveMotif, | Cat#54002 |

| Fluoromount-G | SouthernBiotech | Cat#0100–01 |

| QIAGEN Miniprep kit | QIAGEN | Cat#27106 |

| QIAGEN Hi-Speed Maxi kit | QIAGEN | Cat#12662 |

| Lipofectamin 3000 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#L3000001 |

| SuperSignal west Pico | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#34577 |

| SuperSignal west Femto | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#34094 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HEK293 cell line | ATCC | CRL-1573 |

| Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | This paper | N/A |

| Mouse iPSCs | A Swaroop (PI) (Chen et al., 2016) | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX stock #000664 |

| Mouse: B6.Cg-Cep290rd16/Boc | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX stock #012283 |

| Mouse: Cep290rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— | A Swaroop (PI) (Cideciyan et al., 2011) | N/A |

| Mouse: B6;129-Nrltm1Asw/J (or Nrl—/—) | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX stock #021152 |

| Mouse: Cep290+/—;Nrl—/— | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for Cep290 fragments, see Table S1 | This paper | N/A |

| CMV-probe: 6FAM-TCCAAAATGTCGTAACAA CT–MGBNFQ |

This paper | N/A |

| CMV F: TGGGAGTTTGTTTTGCACCAA | This paper | N/A |

| CMV R: CGCCTACCGCCCATTTG | This paper | N/A |

| sgRNA Cep290: CCAGGAAGTAGAGCTCGCTT | This paper | N/A |

| sgRNA EGFP: CGCGCCGAGGTGAAGTTCGA | Z Wu (PI) (Yu et al., 2017) | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GraphPad prism | GraphPad software | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Espion software | Diagnosys LLC | http://diagnosysllc.com/products/ |

| OptoMotry© software (ver14) | Cerebral Mechanics | http://www.cerebralmechanics.com/ |

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact Zhijian Wu (wuzh@nei.nih.gov).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

This study used the following mouse strains: C57BL/6J (JAX stock #000664), Cep290 rd16/rd16 (or B6.Cg-Cep290rd16/Boc, JAX stock #012283), Nrl—/— (or B6;129-Nrltm1Asw/J, JAX stock #021152) (Mears et al., 2001), Cep290 rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— (Cideciyan et al., 2011) and Cep290+/—;Nrl—/— mice. The Cep290+/—;Nrl—/— mouse line was obtained by crossing the Cep290+/— mice (Rachel et al., 2015) with the Nrl—/— mice. All mice were kept in central facility maintained by NIH animal care facility personnel with controlled ambient illumination on a 12h light/12h dark cycle. The studies conform to the ARVO statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. All the animal study protocols were approved by the NEI Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were typically 8 days to 8.5 months old at the time of use and consisted of males and females.

Cell lines

HEK293 cells were purchased from ATCC (Cat#CRL-1573) and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, GIBCO BRL) with 4g/L glucose and with 1mM sodium pyruvate supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS) containing penicillin/ streptomycin in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37°C. The cells were passaged at 80%–90% confluency.

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were prepared from pregnant mouse at E14. The mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. The embryos were removed from uterus. Heads were removed and body cavities were cleaned. The rest of the embryos was minced and re-suspended in 1 × 0.25% trypsin-EDTA by repetitive pipetting. After incubation at 37°C for 5 min, the supernatant was transferred to pre-warmed medium (DMEM with sodium pyruvate, GlutaMAX and 15% FBS) formulated for mouse embryonic fibroblast culture (MEF medium). This step was repeated four times to collect all the fibroblasts. MEFs were pelleted by centrifuging at 1,000 rpm for 5 min and plated in 150-mm plates with pre-warmed fresh MEF medium.

The mouse wild-type (WT) induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) clone was generated, characterized and maintained as previously described (Chen et al., 2016). Briefly, the iPSC clones were reprogrammed from fibroblasts of embryonic day 14.5 Nrl-GFP WT mice, by infection of Doxycyclin-inducible lentiviral vectors carrying Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc genes. Embryonic stem cell-like colonies were selected and evaluated by morphology, proliferation rate and percentage of cells with Nanog expression. The selected iPSC clones were maintained on feeder cells (Millipore) in maintenance medium comprised of Knockout DMEM (Life Technologies), 1 × MEM non-essential amino acids (NEAA)(Sigma), 1 × GlutaMAX (Life Technologies), 1 × Penicillin-Streptomycin (PS) (Life Technologies), 2000 U/ml LIF (Millipore), and 15% ES cell-qualified fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies) at 37°C, 5% CO2. Media were fully changed every day, with 1 × 2-Mercaptoethanol (2-ME) (Life Technologies) freshly added. Cells were passaged using TrypLE Express (Life Technologies) every two or three days.

METHODS DETAILS

Plasmid construction and AAV vector production

The constructs carrying full-length or truncated Cep290 fragments were generated by PCR amplification with Sac II and BglII restriction enzyme sites at the 5’ and 3’ end respectively from a synthetic murine Cep290 cDNA-containing plasmid maintained in the lab. The epitope tags, e.g., Myc, 3 × flag or HA, were incorporated into the constructs by PCR primers. The rd16 deletion in the construct was incorporated by two-step overlapping extension PCR method described previously (Lee et al., 2004). The resulting PCR products were digested with Sac II and BglII restriction enzymes and cloned into an existing AAV shuttle plasmid with CMV promoter and a β-globin poly A tail maintained in the lab. These plasmids were also used as expression plasmids in cell culture-based assays. Primers used for cloning purpose are listed in Table S1.

The plasmid containing spCas9 was described previously (Yu et al., 2017). The sgRNA against the Cep290 and EGFP were cloned into existing AAV shuttle vector maintained in the lab containing the sgRNA scaffold with the U6 promoter. The synthetic sgRNA with Sap I restriction site overhang was used for cloning it into the shuttle vector. HA-tagged myo-tail expression cassette was cloned between Sac II and BglII restriction enzyme sites, which is downstream to the sgRNA cassette.

AAV particles was produced in HEK293 cells by triple-transfection method as described previously (Grimm et al., 2003). HEK293 cells were transfected with three plasmids simultaneously, containing the transgene, genes required for viral replication and capsid assembly and adenoviral genes needed for helper function. Two days after transfection, virus particles were isolated by rupturing the transfected cells and purified by Cesium Chloride density gradient centrifugation. The virus particles were suspended in tris-buffered saline (10 µm Tris–HCl, 180 µm NaCl, pH 7.4) with Pluronic F-68 (0.001%) and stored at —80°C freezer.

Subretinal Injection

Subretinal injections were performed with the protocol described previously with some modifications (Sun et al., 2010). Mice older than P14 were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/Kg) and xylazine (8 mg/Kg). The pupils were dilated with topical tropicamide (0.5%), phenylepinephrin (2.5%) and proparacaine (0.5%) was used for topical anesthesia. For convenience, all the components were mixed together with equal volume and a single drop of the mixture was applied to each eye. Surgery was performed under an ophthalmic surgical microscope. An 18-gauge sharp needle was used to make a small incision in the cornea adjacent to limbus. A 34-gauge blunt needle fitted with Hamilton syringe was inserted slowly through the corneal incision avoiding the lens and pushed through the retina. One microliter of AAV vector diluted in dialysis buffer (10 µm Tris–HCl, 180 µm NaCl, pH 7.4) was delivered subretinally. Fluorescein (100 mg/ml AK-FLUOR, Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) was used to visualize the movement of injected fluid in the subretinal space.

For mice younger than P10, anesthesia was achieved by hypothermia. The eyes were then popped out by cutting open the eye lid. They were injected following the same method described above for mice older than P14.

Electroretinography

ERGs were performed with Espion E2 system (Diagnosys LLC). Mice were dark adapted overnight. The pupils were dilated with topical phenylephrine (2.5%) and tropicamide (0.5%). Then the mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/Kg) and xylazine (8 mg/Kg). All the above procedures were done under dim red light. ERGs were recorded for eyes using a gold wire loop with proparacaine (0.5%) as a local anesthesia and a drop of hypromellose (2.5%) ophthalmic demulcent solution for corneal hydration. A gold wire loop was placed in mouth as a reference. The whole system is grounded with another electrode on the platform. Dark adapted ERG was performed with flash intensities ranging from –4.0 to +3.0 log.cd.s.m—2. Light adapted ERG was performed after light adapting the animal for 2 min in 32cd.m−2 rod suppressing white light, and recorded with light flash intensities ranging from –0.53 to +2.0 log cd.s.m-2. The flicker response was taken with 10Hz light flick. The responses were taken in a 3 to 60 s interval depending on the flash intensity and were computer averaged. For Cep290 rd16/rd16;Nrl—/— and Nrl—/— mice where no rod cells are present, only light adapted ERG was preformed using the same protocol above without dark adapting the animals.

For recording the M and S cone mediated responses, mice were light adapted with 20 cd.m−2 green light for 2 min. ERG was recorded with alternating green and UV light flashes with a background green light of 20 cd.m-2. The green light intensities were ranged from 0.1671 × 104 to 55.7 × 104 photon.µm−2 and the UV light intensities ranges from 0.0113 × 104 to 33.9 × 104 photon.mm-2.

Optomotor test

Visual behavior test was performed by a virtual-reality system (Douglas et al., 2005; Prusky et al., 2004) (OptoMotry; Cerebral Mechanics Inc). The mouse was placed on an elevated platform in a closed box surround by four LCD monitors. The mirror in the base of the box created an illusion of infinite depth and kept the mouse form falling off the platform. A camera placed on top to monitor the movement of the mouse. The four computer screens created a virtual image of circular rotating drum with sine-wave grating. The tracking of the rotating gratings was determined by the head and neck movement of the mouse. The spatial frequency of the grating was controlled by OptoMotry © software (ver14). The maximum spatial frequency that generates a tracking movement was scored for each eye. All the tests were performed with 100% background contrast.

Immunoblot

For western blot retinal or cellular lysate was prepared in RIPA buffer. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. Protein was measured by Bio-Rad protein assay kit. The protein was denatured by boiling in SDS lysis buffer. Electrophoresis was done with equal amount of protein in Bio-Rad precast TGX gel with molecular weight marker (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). The protein was then transferred to PVDF membrane, blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST at room temperature, incubated overnight in primary antibody diluted to desired concentration in TBST with 2% non-fat dry milk, washed three time with TBST, incubated in HRP conjugated secondary antibody, washed three times in TBST and developed with chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). The image was developed either by using X-ray film or by Chemidoc (Bio-Rad Inc, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence

For immunostaining, mouse eyes were collected after euthanasia and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 1 h. Lens and cornea were removed and the eye cup was kept in 30% sucrose for overnight. The eye cups were then mounted in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek Inc,Torance, CA USA) and frozen with dry ice and ethanol mix. Orientation of the eyes was determined by the position of the nictitating membrane which marks the nasal side. Thin sections (10 µm) were cut with cryostat and placed on charged slides (Super- frost Plus®, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) which aid in adherence of the sections. The sections were blocked with 5% donkey serum diluted in phosphate buffered saline with 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST) for 30 min. The sections were then incubated over- night with primary antibodies diluted in PBST with 2% donkey serum. Sections were washed three times in PBST the following day and then stained with appropriate secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa fluor 488, 568 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). The sections were mounted with Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech Inc) and observed under confocal/fluorescence micro- scope. DAPI was used for nuclear staining.

An alternative protocol was used for staining the connecting ciliary proteins (Hong et al., 2003). In this process mouse eyes were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen after enucleation and embedded in OCT solutions. Thin sections were cut by cryostat and fixed for 2 min on the slide with 4% PFA, washed with PBS for three times and then stained with desired primary and secondary antibody as described above.

For immunofluorescence assay using cultured cells, the cells were fixed and permeabilized with PBS containing 5% donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100. The cells were then incubated with primary antibody overnight. On the following day, they were washed three times with PBS and incubated with appropriate secondary antibody for 1 h. The cells were then rewashed three times with PBS and observed under confocal/fluorescence microscope. Fixation, cryosectioning and immunostaining of retinal organoids have been described in detail previously (Chen et al., 2016; DiStefano et al., 2018).

Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

The Co-IP assay was performed with Active Motif Co-IP kit (Active Motif Inc; Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, the cells were collected in ice-cold PBS buffer with protease inhibitors. Then the cells were lysed in whole cell lysis buffer with protease inhibitors provided with the kit. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 mins. The protein concentration of the lysate was measured by Bio-Rad (Bio-Rad Inc; Hercules, CA, USA) protein assay kit. About 1,000 µg of whole protein lysate was incubated with the desired antibody overnight at a rotating platform. Isotype control immunoglobulin (IgG) was used as a negative control. Next day the antigen-antibody complex was incubated with magnetic protein G beads for 2hrs on a rotating platform. The antigen-antibody-protein G complex was washed with Co-IP wash buffer for three times and then boiled with Laemmli sample buffer to release and denature the precipitated proteins. The proteins were detected by western blot with 50 µg of whole cell lysate as input control. All the procedure starting from cell collection to the addition of Laemmli buffer was carried out at 4°C or on ice.

Electron microscopy

Mouse eyes were collected after euthanasia and fixed in PBS buffered glutaraldehyde (2.5%)/PFA (2%) and dehydrated with increasing percentage of ethanol (50%, 70%, 95% and 100%) propylene oxide, and embedded in epoxy resin (Embed 812; Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA). Ultrathin sections (100nm) of mouse eyes were cut by ultra-microtome. The sections were then stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and mounted on copper grid and observed under electron microscope.

Vector administration in the inner ear

AAV8 myo-tail was administrated in the inner ear of 2-day-old Cep290rd16/rd16 mice using a protocol described previously (Isgrig et al., 2017). In brief, the mice were anesthetized by hypothermia. Unilateral vector administration was done by making a post-auricular incision following which posterior semicircular canal was exposed and vector was delivered by a glass micropipette with a micro-injector. Untreated animals were used as control.

Measurement of auditory brainstem response

Auditory brainstem response (ABR) testing was used to evaluate hearing sensitivity. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injections and placed on a warming pad inside a sound booth (ETS-Lindgren Acoustic Systems, Cedar Park, TX). The animal’s temperature was maintained using a closed feedback loop and monitored using a rectal probe (CWE Incorporated, TC-1000, Ardmore, PN). Sub-dermal needle electrodes were inserted at the vertex (+) and test-ear mastoid (−) with a ground electrode under the contralateral ear. Stimulus generation and ABR recordings were completed using Tucker Davis Technologies hardware (RZ6 Multi I/O Processor, Tucker-Davis Technologies, Gainesville, FL, USA) and software (BioSigRx, v.5.1). ABR thresholds were measured at 4, 8, 16, and 32 kHz using 3-ms, Blackman-gated tone pips presented at 29.9/sec with alternating stimulus polarity. At each stimulus level, 512 to 1024 responses were averaged. Thresholds were determined by visual inspection of the waveforms and were defined as the lowest stimulus level at which any wave could be reliably detected. A minimum of two waveforms was obtained at the threshold level to ensure repeatability of the response. Physiological results were analyzed for individual frequencies, and then averaged for each of these frequencies from 4 to 32 kHz.

Differentiation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells into retinal organoids

WT iPSCs were differentiated into retinal organoids using the HIPRO protocol, with minor modifications (Chen et al., 2016; DiStefano et al., 2018). At differentiation day (D) 0, dissociated single cells were plated in PrimeSurface low adhesion U-shaped 96-well plate (Wako) at a density of 3,000 cells per well in 100 µl retinal differentiation medium GMEM (Life Technologies), 1 × NEAA (Sigma), 1 × sodium pyruvate (Sigma) and 1.5%(v/v) knockout serum replacement (Life Technologies). Twenty percent (v/v) diluted Matrigel (120 µl > 9.5 mg/ml Matrigel diluted in 900 µl retinal differentiation medium, Corning) was added to each well at D1. At D7, retinal organoids with clear optic vesicle structure were transferred to a 100 µm Poly 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (Sigma)-coated Petri dish with 10 mL DMEM/F12 with GlutaMAX (Life Technologies),1 × N2 supplement (Life Technologies) and 1 × PS (Life Technologies). Organoid cultures were maintained in DMEM/F12 with GlutaMAX (Life Technol- ogies), 1 × PS (Life Technologies), 1 × N2 supplement (Life Technologies), 1 mM taurine (Sigma), 500 nM 9-cis retinal (Sigma) and 100 ng/ml insulin-like growth factor 1 (Life Technologies) from D10 to D26. 1 × NEAA acid (Sigma), 1 × B27 supplement without Vitamin A (Life Technologies) and 2%(v/v) FBS (Atlanta Biologicals) were added to the culture after D26. Media were half exchanged every two days with 1 × 2-ME was freshly added. The cultures were maintained in 5% O2 from D0 to D10 and in 20% O2 from D10 onward.

Viral infection

For ciliogenesis assay of MEFs, 5,000 MEFs were plated on 0.1% gelatin-coated 8-well chamber (Ibidi, Munich, Germany) in MEF medium. Forty-eight hours after plating, cells were supplied with serum-free medium only (untreated), with AAV2 null vector, or with AAV2-myo-tail vector, in an MOI of 106 vector genomes (vg) per cell. The medium was removed 6 h later and the cells were supplied with regular MEF medium. Three days after infection, MEFs were serum starved for 72 h for cilia growth. To infect retinal organoids, AAV2 carrying null vector or myosin tail was added to the culture with an MOI of 5 × 109 vg per organoid at D18.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For graphs, data are shown as mean ± SEM unless otherwise specified. Two tailed unpaired t test was used to compare ERG response between control and Cep290 mutant mice (Figure 1 and Figure S1), and to compare auditory brainstem response and inner/outer hair cell counts between untreated and vector treated Cep290rd16/rd16 mice (Figure S6). Two-tailed paired t test was used to compare ERG or optomotor responses between eyes receiving different treatment (Figure 2, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure S2, Figure S3, Figure S4, Figure S5). For in vitro assays, one-way ANOVA (95% confidence interval) was used to compare different groups and Tukey’s test was used as Post hoc test (Figure 7). p < 0.05 was considered significant. Number of mice or replicates in each experiment is provided in the corresponding figure or figure legend. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A CEP290 C-terminal fragment rescues retinal degeneration due to the Cep290rd16 mutation

Full function of CEP290 is reconstituted by CEP290rd16and the C-terminal fragment

Complementation of the Cep290rd16 mutation is cell-type independent

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to Margaret Starostik for assistance with the violin plot and to Dr. Pinghu Liu and Dr. Lijin Dong for their technical support of cell culture. We also thank the Visual Function Core, Histopathology Core, and Biological Imaging Core of the National Eye Institute for their assistance. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Eye Institute (EY000443, EY000474, and EY000546) and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (DC000082–02).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

Z.W., A.S., S.M., and S.H. have submitted a patent application entitled ‘‘Methods and Compositions for Treating Leber Congenital Amaurosis.’’

REFERENCES

- Apte RS (2018). Gene therapy for retinal degeneration. Cell 173, 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baala L, Audollent S, Martinovic J, Ozilou C, Babron MC, Sivanandamoorthy S, Saunier S, Salomon R, Gonzales M, Rattenberry E, et al. (2007). Pleiotropic effects of CEP290 (NPHP6) mutations extend to Meckel syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet 81, 170–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barny I, Perrault I, Michel C, Soussan M, Goudin N, Rio M, Thomas S, Attie´ -Bitach T, Hamel C, Dollfus H, et al. (2018). Basal exon skipping and nonsense-associated altered splicing allows bypassing complete CEP290 loss-of-function in individuals with unusually mild retinal disease. Hum. Mol. Genet 27, 2689–2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baye LM, Patrinostro X, Swaminathan S, Beck JS, Zhang Y, Stone EM, Sheffield VC, and Slusarski DC (2011). The N-terminal region of centrosomal protein 290 (CEP290) restores vision in a zebrafish model of human blindness. Hum. Mol. Genet 20, 1467–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betleja E, and Cole DG (2010). Ciliary trafficking: CEP290 guards a gated community. Curr. Biol 20, R928–R931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boye SE, Huang WC, Roman AJ, Sumaroka A, Boye SL, Ryals RC, Olivares MB, Ruan Q, Tucker BA, Stone EM, et al. (2014). Natural history of cone disease in the murine model of Leber congenital amaurosis due to CEP290 mutation: determining the timing and expectation of therapy. PLoS One 9, e92928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun DA, and Hildebrandt F (2017). Ciliopathies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 9, a028191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnight ER, Wiley LA, Drack AV, Braun TA, Anfinson KR, Kaalberg EE, Halder JA, Affatigato LM, Mullins RF, Stone EM, and Tucker BA (2014). CEP290 gene transfer rescues Leber congenital amaurosis cellular phenotype. Gene Ther 21, 662–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebotaru L, Vij N, Ciobanu I, Wright J, Flotte T, and Guggino WB (2008). Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator missing the first four trans-membrane segments increases wild type and DeltaF508 processing. J. Biol. Chem 283, 21926–21933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain K, Riyad JM, and Weber T (2016). Expressing transgenes that exceed the packaging capacity of adeno-associated virus capsids. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 27, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Khanna H, Hawes N, Jimeno D, He S, Lillo C, Parapuram SK, Cheng H, Scott A, Hurd RE, et al. (2006). In-frame deletion in a novel centrosomal/ciliary protein CEP290/NPHP6 perturbs its interaction with RPGR and results in early-onset retinal degeneration in the rd16 mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet 15, 1847–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HY, Kaya KD, Dong L, and Swaroop A (2016). Three-dimensional retinal organoids from mouse pluripotent stem cells mimic in vivo development with enhanced stratification and rod photoreceptor differentiation. Mol. Vis 22, 1077–1094. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Rachel RA, Aleman TS, Swider M, Schwartz SB, Sumaroka A, Roman AJ, Stone EM, Jacobson SG, and Swaroop A (2011). Cone photoreceptors are the main targets for gene therapy of NPHP5 (IQCB1) or NPHP6 (CEP290) blindness: generation of an all-cone Nphp6 hypomorph mouse that mimics the human retinal ciliopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet 20, 1411–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppieters F, Casteels I, Meire F, De Jaegere S, Hooghe S, van Regemorter N, Van Esch H, Matuleviciene A, Nunes L, Meersschaut V, et al. (2010). Genetic screening of LCA in Belgium: predominance of CEP290 and identification of potential modifier alleles in AHI1 of CEP290-related pheno-types. Hum. Mutat 31, E1709–E1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H, and Silverman SR (1970). Hearing and Deafness, Third Edition (Holt; ). [Google Scholar]

- den Hollander AI, Koenekoop RK, Yzer S, Lopez I, Arends ML, Voesenek KE, Zonneveld MN, Strom TM, Meitinger T, Brunner HG, et al. (2006). Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) gene are a frequent cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet 79, 556–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano T, Chen HY, Panebianco C, Kaya KD, Brooks MJ, Gieser L, Morgan NY, Pohida T, and Swaroop A (2018). Accelerated and improved differentiation of retinal organoids from pluripotent stem cells in rotating-wall vessel bioreactors. Stem Cell Reports 10, 300–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RM, Alam NM, Silver BD, McGill TJ, Tschetter WW, and Prusky GT (2005). Independent visual threshold measurements in the two eyes of freely moving rats and mice using a virtual-reality optokinetic system. Vis. Neurosci 22, 677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drivas TG, Holzbaur EL, and Bennett J (2013). Disruption of CEP290 microtubule/membrane-binding domains causes retinal degeneration. J. Clin. Invest 123, 4525–4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drivas TG, Wojno AP, Tucker BA, Stone EM, and Bennett J (2015). Basal exon skipping and genetic pleiotropy: a predictive model of disease pathogenesis. Sci. Transl. Med 7, 291ra97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garanto A, van Beersum SE, Peters TA, Roepman R, Cremers FP, and Collin RW (2013). Unexpected CEP290 mRNA splicing in a humanized knock-in mouse model for Leber congenital amaurosis. PLoS One 8, e79369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garanto A, Chung DC, Duijkers L, Corral-Serrano JC, Messchaert M, Xiao R, Bennett J, Vandenberghe LH, and Collin RW (2016). In vitro and in vivo rescue of aberrant splicing in CEP290-associated LCA by antisense oligonucleotide delivery. Hum. Mol. Genet 25, 2552– 2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge´ rard, X., Perrault, I., Munnich, A., Kaplan, J., and Rozet, J.M. (2015). Intravitreal injection of splice-switching oligonucleotides to manipulate splicing in retinal cells. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 4, e250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Minami E, Blankinship MJ, Haraguchi M, Meuse L, Finn E, Adams ME, Froehner SC, Murry CE, and Chamberlain JS (2006). rAAV6-microdystrophin preserves muscle function and extends lifespan in severely dystrophic mice. Nat. Med 12, 787–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D, Zhou S, Nakai H, Thomas CE, Storm TA, Fuess S, Matsushita T, Allen J, Surosky R, Lochrie M, et al. (2003). Preclinical in vivo evaluation of pseudotyped adeno-associated virus vectors for liver gene therapy. Blood 102, 2412–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong DH, and Li T (2002). Complex expression pattern of RPGR reveals a role for purine-rich exonic splicing enhancers. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 43, 3373–3382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong DH, Yue G, Adamian M, and Li T (2001). Retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGRr)-interacting protein is stably associated with the photoreceptor ciliary axoneme and anchors RPGR to the connecting cilium. J. Biol. Chem 276, 12091–12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong DH, Pawlyk B, Sokolov M, Strissel KJ, Yang J, Tulloch B, Wright AF, Arshavsky VY, and Li T (2003). RPGR isoforms in photoreceptor connecting cilia and the transitional zone of motile cilia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 44, 2413–2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lHsiao YC, Tong ZJ, Westfall JE, Ault JG, Page-McCaw PS, and Ferand RJ (2009). Ahi1, whose human ortholog is mutated in Joubert syndrome, is required for Rab8a localization, ciliogenesis and vesicle trafficking. Hum. Mol. Genet 18, 3926–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isgrig K, Shteamer JW, Belyantseva IA, Drummond MC, Fitzgerald TS, Vijayakumar S, Jones SM, Griffith AJ, Friedman TB, Cunningham LL, and Chien WW (2017). Gene therapy restores balance and auditory functions in a mouse model of Usher syndrome. Mol. Ther 25, 780–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Krishnaswami SR, and Gleeson JG (2008). CEP290 interacts with the centriolar satellite component PCM-1 and is required for Rab8 localization to the primary cilium. Hum. Mol. Genet 17, 3796–3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Lee HJ, Shin MK, and Ryu WS (2004). Versatile PCR-mediated insertion or deletion mutagenesis. Biotechniques 36, 398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Snyder WK, Olsson JE, and Dryja TP (1996). Transgenic mice carrying the dominant rhodopsin mutation P347S: evidence for defective vectorial transport of rhodopsin to the outer segments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 14176–14181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen DP, Koenekoop RK, Khanna H, Jenkins PM, Lopez I, Swaroop A, and Martens JR (2007). Hypomorphic CEP290/NPHP6 mutations result in anosmia caused by the selective loss of G proteins in cilia of olfactory sensory neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15917– 15922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh J, Lenting PJ, Rosales C, Lee D, Rabbanian S, Raj D, Patel N, Tuddenham EG, Christophe OD, McVey JH, et al. (2013). Therapeutic levels of FVIII following a single peripheral vein administration of rAAV vector encoding a novel human factor VIII variant. Blood 121, 3335– 3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears AJ, Kondo M, Swain PK, Takada Y, Bush RA, Saunders TL, Sieving PA, and Swaroop A (2001). Nrl is required for rod photoreceptor development. Nat. Genet 29, 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mookherjee S, Hiriyanna S, Kaneshiro K, Li L, Li Y, Li W, Qian H, Li T, Khanna H, Colosi P, et al. (2015). Long-term rescue of cone photoreceptor degeneration in retinitis pigmentosa 2 (RP2)-knockout mice by gene replacement therapy. Hum. Mol. Genet 24, 6446–6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Zamalloa CA, Ghosh AK, Patil SB, Reed NA, Chan LS, Davuluri S, Pera¨ nen J, Hurd TW, Rachel RA, and Khanna H (2011). Accumulation of the Raf-1 kinase inhibitory protein (Rkip) is associated with Cep290-mediated photoreceptor degeneration in ciliopathies. J. Biol. Chem 286, 28276–28286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusky GT, Alam NM, Beekman S, and Douglas RM (2004). Rapid quantification of adult and developing mouse spatial vision using a virtual optomotor system. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 45, 4611–4616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachel RA, Li T, and Swaroop A (2012a). Photoreceptor sensory cilia and ciliopathies: focus on CEP290, RPGR and their interacting proteins. Cilia 1, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachel RA, May-Simera HL, Veleri S, Gotoh N, Choi BY, Murga-Za-malloa C, McIntyre JC, Marek J, Lopez I, Hackett AN, et al. (2012b). Combining Cep290 and Mkks ciliopathy alleles in mice rescues sensory defects and restores ciliogenesis. J. Clin. Invest 122, 1233–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachel RA, Yamamoto EA, Dewanjee MK, May-Simera HL, Sergeev YV, Hackett AN, Pohida K, Munasinghe J, Gotoh N, Wickstead B, et al. (2015). CEP290 alleles in mice disrupt tissue-specific cilia biogenesis and recapitulate features of syndromic ciliopathies. Hum. Mol. Genet 24, 3775–3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan GX, Barry E, Yu D, Lukason M, Cheng SH, and Scaria A (2017). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing as a therapeutic approach for Leber congenital amaurosis 10. Mol. Ther 25, 331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer JA, Otto EA, O’Toole JF, Nurnberg G, Kennedy MA, Becker C, Hennies HC, Helou J, Attanasio M, Fausett BV, et al. (2006). The centrosomal protein nephrocystin-6 is mutated in Joubert syndrome and activates transcription factor ATF4. Nat. Genet 38, 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada H, Lu Q, Insinna-Kettenhofen C, Nagashima K, English MA, Semler EM, Mahgerefteh J, Cideciyan AV, Li T, Brooks BP, et al. (2017). In vitro modeling using ciliopathy-patient-derived cells reveals distinct cilia dysfunctions caused by CEP290 mutations. Cell Rep 20, 384–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian B, Anand M, Khan NW, and Khanna H (2014). Loss of Raf-1 kinase inhibitory protein delays early-onset severe retinal ciliopathy in Cep290rd16 mouse. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 55, 5788–5794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Pawlyk B, Xu X, Liu X, Bulgakov OV, Adamian M, Sandberg MA, Khani SC, Tan MH, Smith AJ, et al. (2010). Gene therapy with a promoter targeting both rods and cones rescues retinal degeneration caused by AIPL1 mutations. Gene Ther 17, 117–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Suzuki J, Hashimoto K, Xiao R, Vandenberghe LH, and Liberman MC (2017). Cochlear gene therapy with ancestral AAV in adult mice: complete transduction of inner hair cells without cochlear dysfunction. Sci. Rep 7, 45524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente EM, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Barrano G, Krishnaswami SR, Castori M, Lancaster MA, Boltshauser E, Boccone L, Al-Gazali L, et al. ; International Joubert Syndrome Related Disorders Study Group (2006). Mutations in CEP290, which encodes a centrosomal protein, cause pleiotropic forms of Joubert syndrome. Nat. Genet 38, 623–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]