Abstract

Background

Overactivated microglial cells exhibit chronic inflammatory response and can lead to the continuous production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, perpetuating inflammation, and ultimately resulting in neuronal injury. 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-Galloyl-β-D-Glucose (PGG), which is a naturally occurring polyphenolic compound, has exhibited anti-inflammatory effect through the inhibition of many cytokines in different experimental models, but its effect on activated microglia cells was never described. In the present study, we investigated PGG effect in proteins involved in the NFƙB and MAPK signaling pathways, which play a central role in inflammation through their ability to induce transcription of pro-inflammatory genes.

Methods

PCR arrays and RT-PCR with individual primers were used to determine the effect of PGG on mRNA expression of genes involved in NFƙB and MAPK signaling pathways. Western blots were performed to confirm PCR results.

Results

The data obtained showed that PGG modulated the expression of 5 genes from the NFƙB (BIRC3, CHUK, IRAK1, NFƙB1, NOD1) and 2 genes from MAPK signaling pathway (CDK2 and MYC) when tested in RT-PCR assays. Western blots confirmed the PCR results at the protein level, showing that PGG attenuated the expression of total and phosphorylated proteins (CDK2, CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1) involved in NFƙB and MAPK signaling.

Conclusion

These findings show that PGG could modulate the expression of genes and proteins involved in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in microglia cells.

Keywords: 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-Galloyl-β-D-Glucose; Microglia cells; NFƙB and MAP kinase signaling pathways

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic microglial activation induces the overproduction of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines (Streit et al., 2004), and might override the beneficial effect of these cells in the CNS (Schwartz & Baruch, 2014). In the state of prolonged inflammation, continual activation and recruitment of effector cells can establish a feedback loop that perpetuates inflammation and ultimately results in neuronal injury (Gendelman, 2002; Oh et al., 2004). The activation of microglial cells is observed in brain injuries and is induced after the exposure to the Gram-negative bacterial coat component, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Hanisch, 2002). Microglial activation is a highly potent trigger for cytokine synthesis through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (Hanisch, 2002), interferon-γ (IFNγ), or amyloid β (Aβ) (Lacy & Stow, 2011; Giulian et al., 1994). The released pro-inflammatory cytokines play a key role in the induction and maintenance of neuroinflammation. Numerous studies confirmed that the levels of classical pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated in chronic neurodegenerative diseases, especially in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and significantly contribute to this disease progression (Smith et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2016; Rocha et al., 2012). This inflammation process is mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines and would create a chronic and self-sustaining inflammatory interaction between activated microglia and astrocytes, stressed neurons, and amyloid β (Aβ) plaques (Rubio-Perez & Morillas-Ruiz, 2012). Also, Aβ can stimulate a nuclear factor-kappa B (NFƙB) dependent pathway which is required for cytokine production (Combs et al., 2001). The subsequent activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways by Aβ binding to the microglial cell surface induces pro-inflammatory gene expression and leads to the production of cytokines and chemokines (Ho et al., 2005).

The expression of NFƙB transcription factors is abundant in the brain. The basal levels of NFƙB expression have been identified in the brain where their amounts are higher than those of peripheral tissues (Shih et al., 2015). Studies of postmortem brain tissue from patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have revealed increased NFƙB activity in cells involved in the neurodegenerative process. p65 immunoreactivity increased in neurons and astrocytes in the immediate vicinity of amyloid plaques in brain sections from AD patients, consistent with NFƙB activation in those cells (O’Neill & Kaltschmidt, 1997). Immunohistochemical analyses of brain sections from Parkinson’s patients revealed a 70-fold increase, relative to age-matched controls, in the proportion of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra exhibiting nuclear p65 immunoreactivity (Hunot et al., 1997). Spinal cords of patients with ALS show increased NFƙB activation in astrocytes associated with degenerating motor neurons (Migheli et al., 1997). Another evidence supporting a role for NFƙB in chronic neurological disorders comes from studies of multiple sclerosis. Analyses of neural tissue from patients with multiple sclerosis indicated that NFƙB is activated at high levels in microglia of active plaques (Bonetti et al., 1999). Therefore, this pathway seems to be an essential target for anti-inflammatory compounds.

Natural compounds offer a great source of novel bioactive compounds and development into drugs for treating inflammatory diseases with fewer side effects and more accessible costs (Gautam & Jachak, 2009). 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-Galloyl-β-D-glucose (PGG) is a naturally occurring polyphenolic compound highly enriched in some medicinal herbs such as Rhus chinensis Mill and Paeonia suffruticosa (Cao et al., 2014). These plants have been reported as a traditional Chinese medicine (Djakpo & Yao, 2010). PGG studies have reported its anti-angiogenesis, anti-cancer, and anti-diabetic effects (Yu et al., 2011; Bruno et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009). In our laboratory, we have established that PGG is a very potent inhibitor of hLDH-A, which is a therapeutic target for cancer, given its role in tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis (Deiab et al., 2015).

Previous studies showed that PGG also exhibits anti-aggregation effects on Alzheimer’s amyloid β proteins in vitro and in vivo. Low concentrations of PGG (IC50=3uM) could inhibit Aβ aggregation and promote its destabilization. PGG oral intake reduced Aβ plaque burden and Aβ peptide content in brain tissue in transgenic mice, suggesting that PGG could be a potential therapeutic drug for AD patients with mild cognitive impairment (Fujiwara et al., 2009). Studies involving pro-inflammatory cytokines showed PGG activity through the inhibition of the expression of TNF-α in LPS-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Feldman et al., 2011), and the secretion of TNF-α and IL-6 induced by IL-1-β in rat synoviocytes (Wu & Gu, 2009). It also inhibited IL-8 mRNA expression and secretion in human monocytic U937 cells stimulated with PMA or TNF-α (Oh et al., 2004). PGG studies in peritoneal and colonic macrophages reduced activation of NFƙB and MAPK signaling pathways by directly interacting with the MyD88 adaptor protein, having a potential to ameliorate inflammatory diseases, such as colitis (Jang et al., 2013). PGG also suppressed gene expression and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in a dose-dependent manner and blocked the activation of NFƙB, indicating its potential for the treatment of inflammatory diseases through the down-regulation of NFƙB mediated activation of human mast cells (Lee et al., 2007).

In our previous study, we demonstrated that PGG inhibited the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines: MCP-5 and Pro MMP-9, which may be associated with the formation of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in AD disease (Mendonca et al., 2017). Therefore, the present study was designed to determine the effect of PGG in genes and proteins of the NFƙB and MAPK signaling pathways, which are known to have a crucial role in inflammatory processes through their ability to induce transcription of pro-inflammatory genes.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium-High Glucose Medium (DMEM) and Heat Inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS-HI) were obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Flowery Branch, GA, USA). Penicillin/streptomycin and Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) were obtained from GIBCO (Waltham, MA, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-Galloyl-β-D-glucose (purity 96.8%), lipopolysaccharide from Salmonella enterica (LPS), interferon γ (IFNγ), and other general reagents were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and VWR International (Radnor, PA, USA). NFƙB and MAPK signaling pathways arrays, Bradford protein assay and PCR reagents were bought from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). Protease and Phosphatase inhibitors were obtained from G-Biosciences (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Anti-goat IgG-horseradish peroxidase and anti-GAPDH antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and primary antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA), and Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), as listed below.

2.2. Cell Culture

BV-2 microglial cells were generously provided by Dr. Elizabetta Blasi (Blasi et al., 1990). Cells were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% Heat Inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS-HI) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100U/ml penicillin and 0.1mg/ml streptomycin) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37oC in an incubator. Plating media for each experiment consisted of DMEM, 2.5% of FBS-HI, and no penicillin/streptomycin-penicillin. LPS was prepared in water at 1 mg/ml, and IFNγ in PBS at 200ng/ml; both stored at −20oC. For experiments, LPS and IFNγ were added to the culture media at a working concentration of 0.2µg/ml and 0.2ng/ml, respectively. PGG was dissolved in DMSO before dilution in the media and the final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1% (Elsisi et al., 2005). The concentration of PGG used in all the experiments was 25µM, which was established by cell viability in our previous study (Mendonca et al., 2017). The experiments were set in T-75 flasks, and the concentration of cells was 5×105/ml.

2.3. PCR

2.3.1. RNA Extraction

BV-2 cells were treated with PGG and then activated or not with LPS/IFNγ after 1 h. The cells were harvested after 24 h and then washed twice with PBS. Cell pellets were lysed with the 1ml Trizol reagent. Chloroform (0.2 ml) was added to the lysed samples; the tubes were shaken, incubated at 15–30°C for 2–3 min and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 2–8°C. The aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube, and the RNA precipitated by mixing 0.5 ml of isopropyl alcohol. After incubation, samples were centrifuged, the supernatant was removed, and the RNA pellets were washed with 75% ethanol. The samples were mixed before being centrifuged at 7,500 g for 5 min at 2–8°C. The RNA pellet was dried and dissolved in RNase-free water and incubated for 30 min on the ice before use. Finally, RNA purity and quantity were determined using Nanodrop (Thermo Fischer Scientific - Wilmington, DE, USA).

2.3.2. cDNA Synthesis

The cDNA strand was synthesized from the mRNA using iScript advanced reverse transcriptase from Bio-Rad. A solution of 4µl of the 5X iScript advanced reaction mix (containing primers), 1µl of reverse transcriptase, 5µl of the sample (250ng/5µl) for RT-PCR assay and 7.5µl of the sample (1.5µg/7.5µl) for RT-PCR with individual primers, and water were added to 0.2ml tubes, in a total of 20µl. The Reverse Transcription thermal cycling program included two steps: 42oC for 30 min and then 85oC for 5 min.

2.3.3. RT-PCR Array (NFƙB and MAPK Signaling Pathway) and RT-PCR (individual primers)

Real-time PCR amplification was performed following the manufacturer protocol (BioRad). A 10µl of the sample (10ng cDNA/reaction) plus 10ul of master mix were added to each well for the array assays, and a 1µl of the sample (200ng cDNA/reaction), 10µl of master mix, 1µl of primer and 8µl of water were added to each tube for the individual RT-PCRs. The thermal cycling process including the initial hold step at 95oC for 2 min and denaturation at 95oC for 5 secs, followed by 40 cycles of 60oC for 30 secs (annealing/extension), and 600C for 5 sec/step (melting curve) using Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time System (Hercules, CA, USA). The PCR arrays were specific to genes that play a role in the NFƙB, and MAPK signaling pathways and the selected primers were specific to each gene of interest.

The UniqueAssay ID for each primer is described as follows:

BIRC3 (UniqueAssayID: qMmuCID0027290); CHUK (UniqueAssayID: qMmuCID0005344); IRAK1 (UniqueAssayID: qMmuCID0005129); NFKB1 (UniqueAssayID: qMmuCID0005357); NOD1 (UniqueAssayID: qMmuCID0015768); CDK2 (UniqueAssayID: qMmuCID0017791); MYC (UniqueAssayID: qMmuCID0006528)

2.4. Western Blot

2.4.1. Protein Assay

BV-2 cells were treated with PGG and then activated or not with LPS/IFNγ after 1 h. The cells were harvested after 24 h and then washed twice with PBS. Lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail and/or phosphatase inhibitor cocktail was added to the pellet. Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad Bradford protein assay. A series of concentration standards ranging from 0 – 2 mg/ml were prepared using bovine serum albumin (BSA). The standards and samples (5µl), and Bio-Rad Bradford protein assay reagent (200µl) were loaded into a 96-well plate. Protein concentrations were quantified at 595 nm wavelength with a microplate reader Infinite M200 (Tecan Trading AG).

2.4.2. Western Blot

Cell lysates were separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to Immobilon-P PVDF membranes. Blots were blocked for 1h with 5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS (PBST) and then incubated overnight at 4oC with the specific antibody (dilution 1:1000). Next day membranes were washed with PBST and incubated with anti-goat IgG-horseradish peroxidase in PBST for 4h. Protein loading was monitored in each gel lane by probing the membranes with anti-GAPDH antibodies. Immunoblot images were obtained using a Bio-Rad VersaDoc Imager, and the densitometry analyzed with Quantity One Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

2.4.3. ProteinSimple Western Assay

Phosphorylated proteins were determined using automated Wes Simple Western Analysis (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA). All reagents were supplied by ProteinSimple, and the analysis was performed according to the user manual. Protocols were optimized for each antibody and protein loading. In brief, protein extracts were mixed with a master mix to give a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml total protein, 1x sample buffer, and 1x fluorescent molecular weight markers and 40 mM dithiothreitol. Samples were heated at 95°C for 5 min. Samples, blocking solution, primary antibodies (dilution: 1:5 to 1:25), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, chemiluminescent substrate, and separation and stacking matrices were loaded into designated wells in a microplate. After plate loading, fully automated electrophoresis and immunodetection took place with the capillary system. Target proteins were identified using a primary antibody and immunosorbed using an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and chemiluminescent substrate. Chemiluminescence was captured by a charge-coupled device camera, and the digital image was analyzed and quantified using ProteinSimple Compass software.

2.5. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism (version 6.07). All data were expressed as a mean ± standard error from at least 3 independent experiments, and the significance of the difference between the groups was assessed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet multiple comparison test. STRING (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins - string-db.org) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes - genome.jp/kegg) databases were used to analyze protein function and interaction.

3. RESULTS

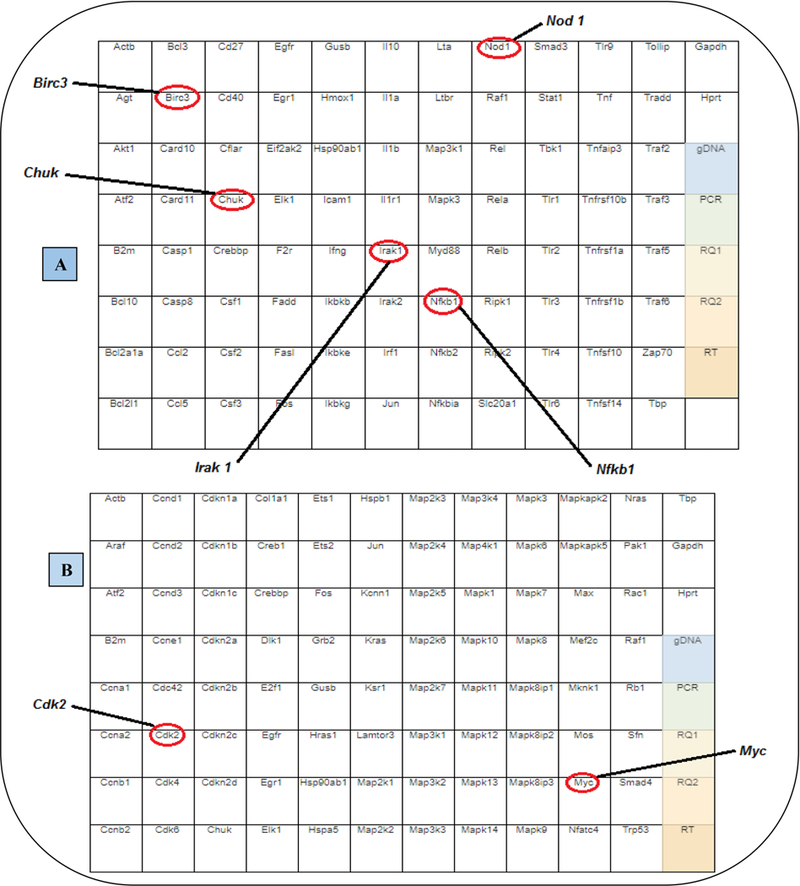

To determine the effect of PGG on mRNA expression of 89 genes from NFƙB and 88 genes from MAPK signaling pathways in BV-2 microglia cells (Figure 1A and 1B), the total RNA of LPS/IFNγ-treated BV-2 cells with and without PGG pre-treatment were subjected to real-time PCR. Results showed that among the studied genes, 7 were significantly modulated by PGG (6 negatively and 1 positively) (Table 1A and 1B).

Figure 1: NFƙB (A) and MAPK (B) PCR array layout.

Figures A and B show the tested genes in each one of the arrays. The red circles show the genes down or up-regulated after PGG pre-treatment (1 h before) in LPS/IFNγ activated BV-2 microglia cells.

Table 1: NFƙB (A) and MAPK (B) PCR array results.

The table shows the difference in gene expression in LPS/IFNγ vs. PGG pre-treatment (PGG (1 h before) + LPS/IFNγ) BV-2 microglia cells. A- NFƙB and B- MAPK signaling pathways. Arrows indicate down or up-regulation of the genes. Statistical significance was evaluated by a Student’s t-test, p≤0.05 (n=3).

| A | Symbol | Description | Fold Change | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIRC3 | Baculoviral IAP Repeat Containning 3 |

⬇1.8 | Cellular inhibitor of Apoptosis, upregulated in activated microglia (Kavanagh et al., 2014) | |

| CHUK | Conserved Helix-Loop-Helix Ubiquitous Kinase |

⬇4.5 | Regulates the release of NFRB transcription factor (Adli et al., 2010) | |

| IRAK1 | Interleukin 1 Receptor Associated Kinase 1 |

⬇9.7 | Protein activated by TLR. Regulates inflammatory Gene expression (Gottipati et al., 2007) | |

| NFKB1 | Nuclear Factor Kappa B Subunit 1 | ⬇3.2 | Regulates the release of NFRB transcription factor (Lappas et al., 2002; Yoon etal., 2009) | |

| NOD1 | Nucleoide Binding Oligomerization Domain Containing 1 |

⬇1.7 | Pathogen recongnition Cytoplasmic receptors (Caruso et al., 2014) | |

| B | Symbol | Description | Fold Change | Function |

| CDK2 | Cyclin Dependent Kinase 2 | ⬇3.8 | Regulation and Progression of Cell Cycle (Kang et al., 1997; Boonstra, 2003) | |

| MYC | Myelocytomatosis Viral Oncogence Homolog |

⬇6.9 | Pro-oncogence Increased in many Neurodegenerative diseases (Ferrer et al., 2001) |

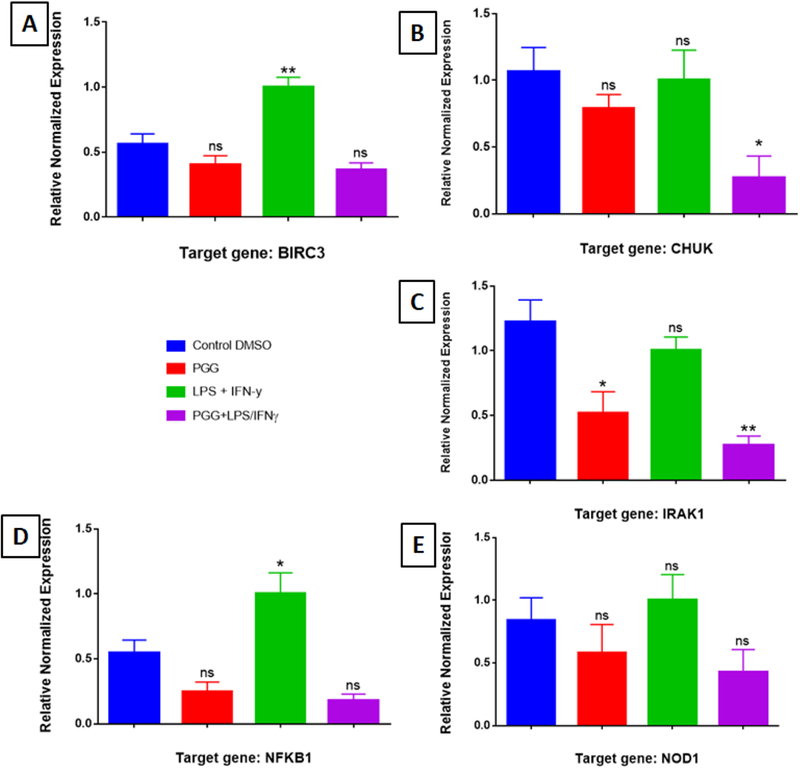

The 6 genes down-regulated by PGG were: BIRC3, CHUK, IRAK1, NFƙB1, NOD1 and CDK2; and the one up-regulated was MYC (see the description of genes in Figure 1A and 1B). Most of them belong to the NFƙB signaling pathway, except CDK2 and MYC, which are involved in the MAPK signaling pathway (Table 1A and 1B). RT-PCR with individual primers was performed with the genes modulated by PGG to validate the results from the arrays. The results corroborated with the ones found in the PCR array. PGG caused a change in the expression of the genes BIRC3, CHUK, IRAK1, NFƙB1, NOD1, CDK2, and MYC involved in the NFƙB and MAPK signaling pathways (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 2: RT-PCR Assay (individual primers): Proteins from NFƙB Signaling.

The effect of PGG on the expression of genes involved in the NFƙB signaling pathway: BIRC3 (A), CHUK (B), IRAK1 (C), NFƙB1 (D), and NOD1 (E). Graph bars show control, PGG (25µM), LPS/IFNy, and PGG pre-treatment (PGG (1 h before) + LPS/IFNγ). Data represent protein expression as the mean ± S.E.M (n=3).). Statistical significance of the difference between control and different treatments was determined by a one-way ANOVA, followed by a Dunnett multiple comparison test. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001and ****p≤0.0001, ns: not significant.

Figure 3: RT-PCR Assay (individual primers): Proteins from MAPK Signaling.

The effect of PGG on the expression of genes involved in the MAPK signaling pathway: CDK2 (A) and MYC (B). Graph bars show control, PGG (25µM), LPS/IFNy, and PGG pre-treatment (PGG (1 h before) + LPS/IFNγ). Data represent protein expression as the mean ± S.E.M (n=3).). Statistical significance of the difference between control and different treatments was determined by a one-way ANOVA, followed by a Dunnett multiple comparison test. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001and ****p≤0.0001, ns: not significant.

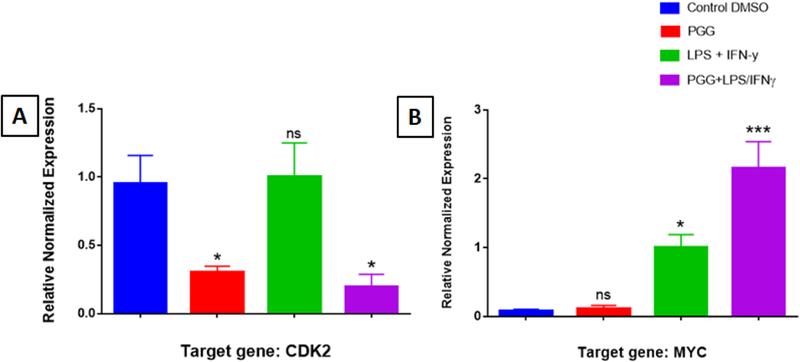

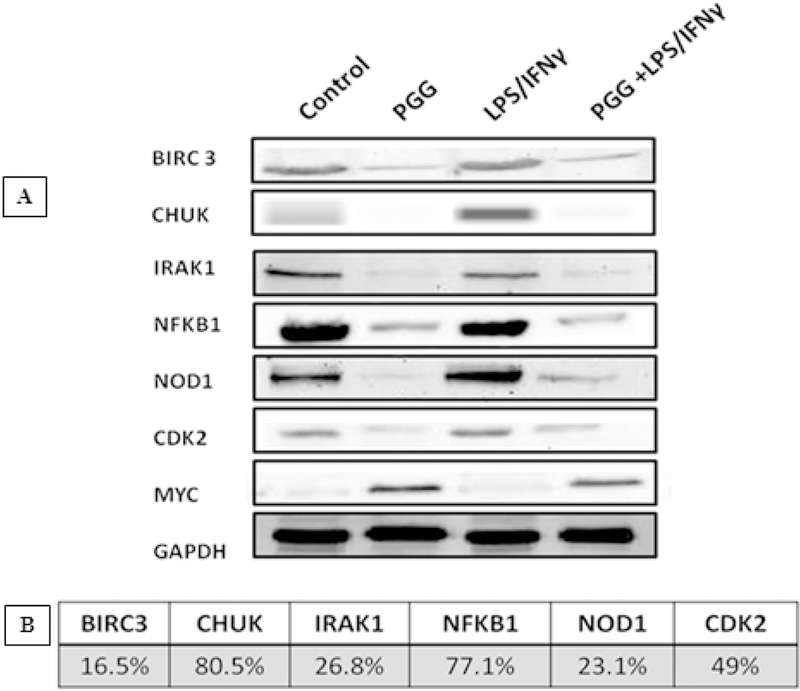

To confirm PCR results at the protein level, Western blots were performed with specific antibodies against BIRC3, CHUK, IRAK1, NFƙB1, NOD1, CDK2, and MYC. The results showed that LPS/IFNγ induced the expressions of these proteins in BV-2 microglial cells, but this induction was significantly reduced when PGG was added 1h before LPS/IFNγ treatment.

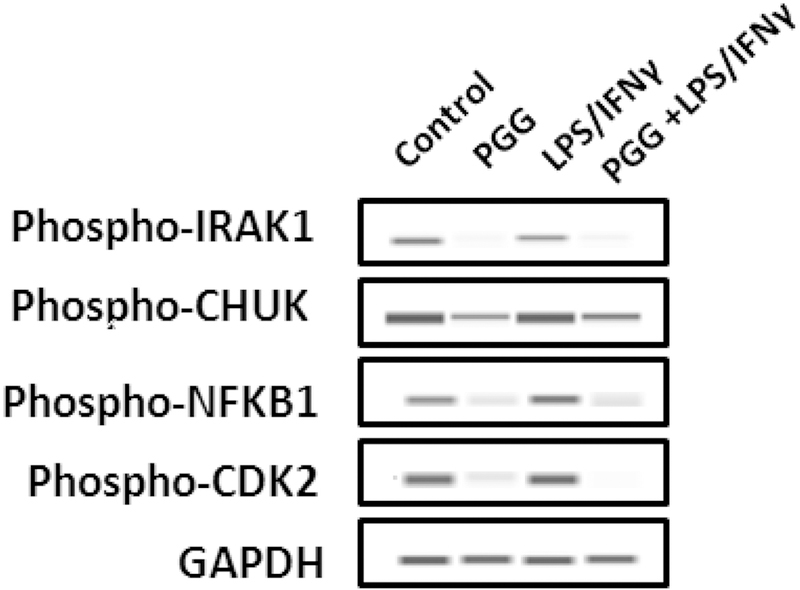

The protein expression of normalized intensity expressed as a percentage of control showed that PGG inhibited the expression of BIRC3 (16.5%), CHUK (80.5%), IRAK1 (26.8%), NFƙB1 (77.1%), NOD1 (23.1%), and CDK2 (49%). The opposite occurred with the gene MYC from the MAPK signaling pathway, which was highly expressed (46%) when the cells were treated with PGG. The results corroborated with the data obtained from the RT-PCR assays (Figure 4A and 4B). The effect of PGG in the expression level of phosphorylated proteins was measured by using ProteinSimple Western assay. CDK2, CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1 were chosen based on the greatest activity of PGG on the inhibition of the total protein levels. The activation of BV-2 microglial cells by LPS/IFNy increased the expression of phosphorylated CDK2, CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1. However, the pre-treatment with PGG attenuated the expression all the examined proteins, following the same pattern as seen when the total proteins were tested (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Western Blot Assay.

The effect of PGG on the expression of total proteins involved in the NFƙB (CHUK, IRAK1, NFƙB1, and NOD1) and MAPK signaling pathways (CDK2 and MYC). Bands (A) represent control, PGG (25µM), LPS/IFNγ, and PGG pre-treatment (PGG (1 h before) + LPS/IFNγ) after 24 hours of treatment. B shows the protein expression of normalized intensity, expressed as % of control of the proteins inhibited by PGG treatment (mean ± S.E.M. n=3).

Figure 5: ProteinSimple Western Assay.

The effect of PGG in the expression of the phosphorylated proteins: IRAK1, CHUK, NFƙB1, and CDK2. Bands represent control, PGG (25µM), LPS/IFNy, and PGG pre-treatment (PGG (1 h before) + LPS/IFNγ) after 24 hours of treatment (n=3).

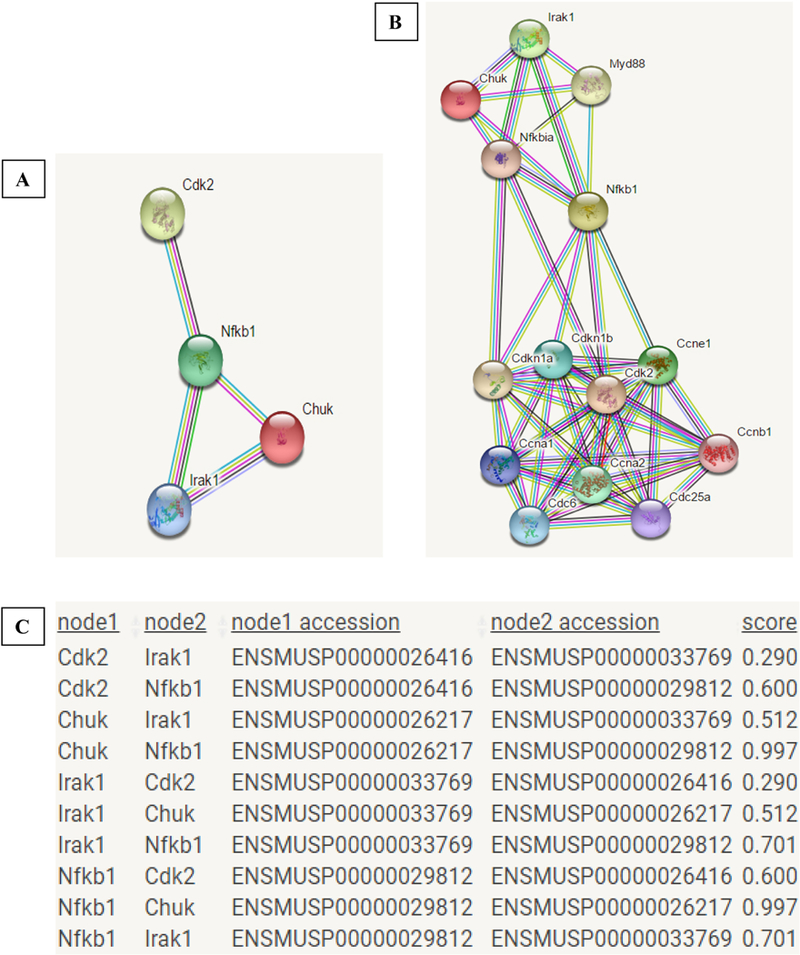

To study the functional protein association among CDK2, CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1, we used bioinformatics tools. STRING database was used to analyze the association of the selected proteins (Figure 6A). The results obtained show that CDK2 and CHUK only interacted with IRAK1 and NFƙB1, while IRAK1 and NFƙB1 show association with all the other two proteins. The highest interaction was found between NFƙB1 and CHUK, and NFƙB1 and IRAK1, suggesting a functional link between them (Figure 6C). Besides the association among these four proteins, several others also interacted with them, maximizing connections in different signaling pathways (Figure 6B).

Figure 6: Protein Association Network.

A- Interactions among IRAK1, CHUK, NFƙB1, and CDK2. B- Interaction among IRAK1, CHUK, NFƙB1, and CDK2 and other proteins in the same network. C- Table showing the protein interactions and the suggested score for the functional link between them, according to STRING database.

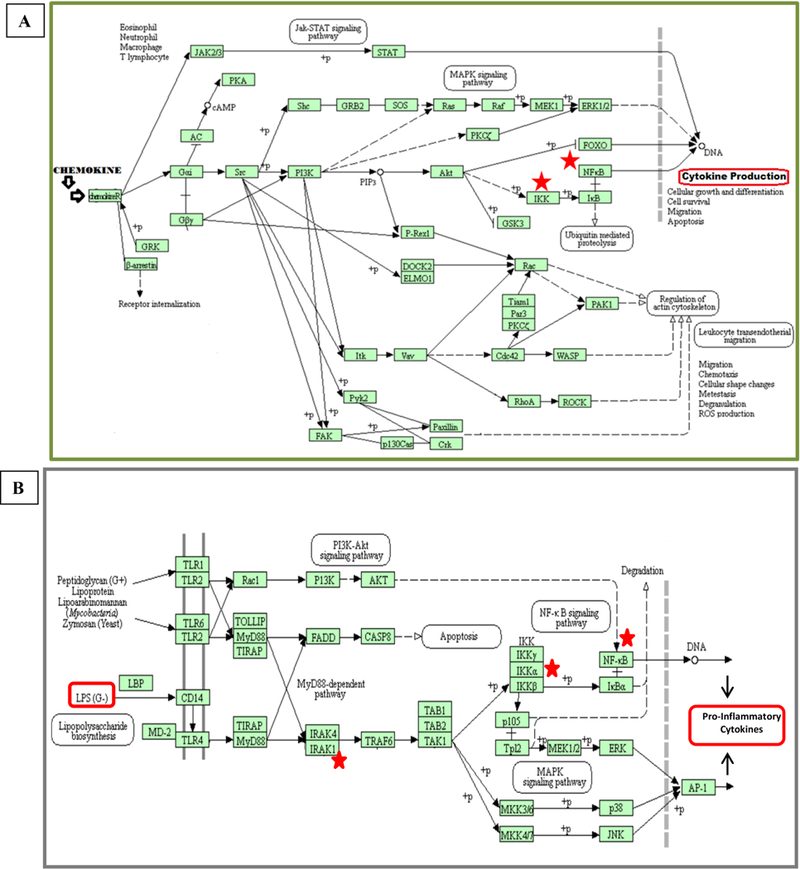

Gene ontology annotation achieved from the STRING database showed that these genes are placed into 5 biological processes and have 2 molecular functions (Table 2A and 2B). They are also involved in 35 KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathways (Table 3). CDK2, CHUK, NFƙB1, and IRAK1 were described as associated with many signaling pathways that lead to cytokine production, including NFƙB, MAPK, Chemokine, Toll-like receptor, and Nod-like Receptor signaling pathways (Table 3; Figures 7).

Table 2: Biological Processes and Molecular Functions.

Table A shows 5 biological processes and Table B shows 2 molecular functions in which CDK2, CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1 are involved (STRING database).

| A | BIOLOGICAL PROCESSES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Description | |||||

| Proteins |

I-KappaB Kinase/NFƙB Signaling |

Intracellular Signal Transduction |

NIK/NFƙB Signaling |

Positive Regulation of Transcription |

Cellular Response to Interleukin-1 |

| IRAK1 | X | X | X | X | |

| CHUK | X | X | X | ||

| NFKB1 | X | X | X | X | X |

| CDK2 | X | X | |||

| B | MOLECULAR FUNCTIONS | ||||

| Pathway Description | |||||

| Proteins |

Protein Heterodimerization activity |

Protein-Serine-Threonine Kinase Activity |

|||

| IRAK1 | X | X | |||

| CHUK | X | X | |||

| NFKB1 | X | ||||

| CDK2 | X | ||||

Table 3: KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) Pathway.

The table shows the 35 pathways by which CDK2, CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1 are involved. The ones in red correspond to the main pathways associated with cytokine production.

| Pathway Description | IRAK1 | CHUK | NFKB1 | CDK2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measles | X | X | X | X |

| Epstein-Barr virus infection | X | X | X | X |

| NF-kappa B signaling pathway | X | X | X | |

| Apoptosis | X | X | X | |

| Prostate cancer | X | X | X | |

| Small cell lung cancer | X | X | X | |

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | X | X | X | |

| Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) | X | X | X | |

| Toxoplasmosis | X | X | X | |

| Hepatitis B | X | X | X | |

| Herpes simplex infection | X | X | X | |

| Pathways in cancer | X | X | X | |

| PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | X | X | X | |

| NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| Acute myeloid leukemia | X | X | ||

| RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| Cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway | X | X | ||

| B cell receptor signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| Adipocytokine signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| Pertussis | X | X | ||

| Leishmaniasis | X | X | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | X | X | ||

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | X | X | ||

| T cell receptor signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| TNF signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| Neurotrophin signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| Osteoclast differentiation | X | X | ||

| FoxO signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| Hepatitis C | X | X | ||

| Tuberculosis | X | X | ||

| Chemokine signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| Viral carcinogenesis | X | X | ||

| Ras signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| MAPK signaling pathway | X | X | ||

| HTLV-I infection | X | X |

Figure 7: Chemokine (A) and Toll-like Receptor (B) Signaling Pathways.

The figure shows the activation pathway for cytokine production, including the steps of receptor activation, gene transcription, and cytokine production. Red stars show where CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1 play their role (KEGG Pathway).

These results show that PGG modulates the expression of genes and proteins involved in the NFƙB and MAPK signaling pathways, which play a key role in cytokines release in the inflammatory process.

4. DISCUSSION

The expression of proinflammatory genes associated with neurodegenerative diseases is regulated by transcriptional mechanisms (Glass et al., 2010). A possible mechanism for the increase in cytokines seen in AD is via Aβ stimulation of NFƙB activity in microglia (Combs et al., 2001). Suppression of NFƙB in microglia results in decreased neurotoxicity (Chen et al., 2005) and NFƙB regulatory elements lie upstream of the APP protein, which is necessary for plaque formation (Grilli et al., 1996). The hypothesis that inflammation and NFƙB activation is the underlying cause of AD is further supported by the observations that chronic LPS injections accelerate AD progression (Lynch et al., 2003) and patients with systemic infection exhibit increased rates of cognitive decline (Holmes et al., 2003). Taken together, the evidence suggests that NFƙB plays a role in plaque formation and even a more important role in inflammation and cytokine signaling in AD progression (Tilstra et al., 2011). Another important signaling route is the MAPK signal transduction pathway, which plays a crucial role in many aspects of immune-mediated inflammatory responses (Hommes et al., 2003). Given the critical role of MAPK pathways in regulating cellular processes that are affected in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the importance of MAPKs in disease pathogenesis is being increasingly recognized. All MAPK pathways, such as ERK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 pathways, are activated in vulnerable neurons in patients with AD, suggesting that MAPK pathways are involved in the pathophysiology and pathogenesis of AD (Zhu et al., 2002).

Previous studies have shown that PGG inhibited LPS-induced IRAK1 degradation and phosphorylation, IKKβ phosphorylation, IƙBα degradation and translocation of the p65 subunit of NFƙB into the nucleus. IRAKs work in the signaling cascades of TLRs, which, unregulated activation may lead to pathological situations ranging from chronic inflammation to the onset of autoimmune diseases (Gottipati et al., 2007) through the induction of pro-inflammatory transcription factors, such as NFƙB (Lukiw et al., 1998; Ringwood & Lil, 2008; Keating et al., 2007; Meylan & Tschopp, 2008). Many genomic studies show that AD brains have a significant disruption in the homeostatic expression of essential brain genes and a progressive up-regulation of inflammatory gene expression, driven in part by over-activation of transcription factor NFƙB. This supports both, the development and progression of neurodegenerative disease processes (Colangelo et al., 2002; Lukiw et al., 2000b; Lukiw & Pogue, 2007; Lukiw, 2004; Loring et al., 2001; Bazan & Lukiw, 2002; Lukiw et al., 2005; Cui et al., 2007). Indeed, the TLR-IRAK-NFƙB signaling axis is substantially over-stimulated in AD brain (Ringwood & Lil, 2008, Colangelo et al., 2002; Lukiw et al., 2000b; Lukiw & Pogue, 2007; Lukiw, 2004) and plays a regulatory role in mediating neuropathological effects of the Aβ peptide since Aβ activation further modulates the release of inflammatory cytokines (Li, 2004; Tan et al., 2008; Tahara et al., 2006;). Regarding neuroinflammation, NFƙB activation has been shown to mediate cytokine expression (Jana et al., 2002; Nakajima et al., 2006). It has been suggested that NFƙB plays an important role in sustaining the vicious cycle of inflammatory response and in neuroglial interactions in neurons and astrocytes (Pugazhenthi et al., 2013). Many reports have been shown that PGG has the potential to suppress the activation of NFƙB via inhibition of IKK activity. PGG inhibited IƙB kinase activity in activated macrophages RAW 264.7 cells activated by LPS, blocked phosphorylation of IƙB from the cytosolic fraction, and inhibited NFƙB activity in activated macrophages (Pan et al., 2000). Also, by using LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages, PGG activity was investigated in several intracellular signaling proteins. PGG treatment reduced the phosphorylation of p-TAK1, p-IKKβ, and p-IκBα at a concentration of 5 μM (Jang et al., 2013).

Using LPS/IFNγ-stimulated BV-2 microglia cells, in this study, we investigated the effect of PGG on several genes and proteins involved in the signaling cascade of NFƙB and MAPK pathways. The results show that PGG may be able to modulate the level of expression of different cytokines that are transcribed in the cellular nucleus, by modulating the expression of genes and proteins that participate in the NFƙB and MAPK signaling activation. Although the controls for some genes presented a high basal activity, by comparing “LPS/ IFNγ” and “PGG + LPS/ IFNγ” treatments, it is clear that PGG was able to attenuate the expression of the genes in a significant way. The results also showed that PGG activity could be seen not only in the transcription but also in the protein level.

Our data showed that PGG down-regulated the expression of NFƙB1, CDK2, CHUK, and IRAK1. All four genes are involved in signaling pathways that lead to the production of inflammatory cytokines through the activation of NFƙB and MAPK pathways. The previous report studying the deregulation of the NFƙB pathway in peripheral mononuclear cells (PBMC) of AD showed that the expression level of the NFƙB1 (p105/50Kd) gene was significantly higher in AD on adult age-matched controls. Also, expression of various genes and both NFƙB p50 and NFƙB p65 DNA binding activity were increased in PBMC from AD patients in comparison with those from age-matched controls (Ascolani et al., 2012). The CDKs (Cyclin-dependent kinases) are known to be responsible for the progression of the cell cycle (Kang et al., 1997; Boonstra, 2003), and play roles in cell differentiation, cell death (especially apoptosis), transcription and neuronal function (Knockaert et al., 2002). Previous studies also have suggested that CDK inhibitor drugs may have potential as a novel anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution agents (Chen et al., 2003). CHUK, also known as IKK-α or IKK1, is involved in the NFƙB activation. Activation of the transcription factor NFƙB by cytokines is rapid, mediated through the activation of the IKK complex with subsequent phosphorylation and degradation of the inhibitory IκB proteins (Adli et al., 2010). IκB phosphorylation by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex is a critical regulatory step in the NFƙB activation pathway (Gilmore, 2006; Scheidereit, 2006), and it involves kinases, including IKK1/IKKα as the catalytic component of this complex. When the pathway is activated, phosphorylated NFƙB dimers are released and translocated to the nucleus, bind to the DNA sequences ƙB, and induce transcription of target genes (Scheidereit, 2006; Zandi et al., 1997). By down-regulating the expression of these genes and proteins, PGG may be modulating the activation of signaling pathways that lead to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which consequently induce neuroinflammation.

Although PGG present gallic acid in its structure, the literature shows that its potential activity is not exclusively because of the presence of this component. Bruno and colleagues (2013) investigated the inhibitory potential of gallic and tannic acid, and the structure related compound PGG, on the aggregation of islet amyloid polypeptide, amylin (IAPP). Results showed that while both, tannic and gallic acids, appear to be poor inhibitors of IAPP-based aggregation, PGG appears to be a strong inhibitor of IAPP-based aggregation. PGG functioned in a concentration-dependent manner to inhibit fiber formation and Thioflavin T (ThT) binding under extreme conditions known to promote IAPP aggregation. The authors stated that it remains to be determined why PGG functions as a strong inhibitor of IAPP aggregation, while its structural relatives, tannic and gallic acids, are not (Bruno et al., 2013). Therefore, the potent properties of PGG listed in our paper may not be the same as the ones exhibited by gallic acid.

5. CONCLUSION

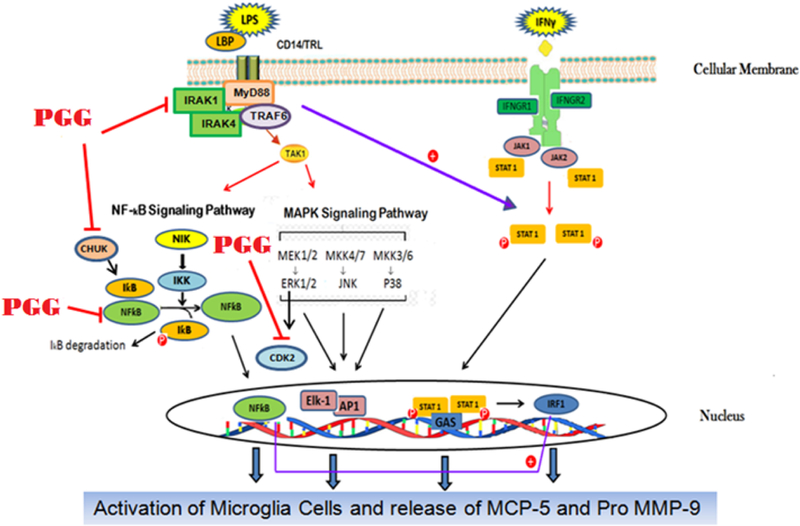

Our findings show that PGG can modulate several genes and proteins involved in the NFƙB and MAPK signaling pathways, which play a key role in neuroinflammation. PGG attenuating effect may be able to regulate TLR-IRAK-NFƙB signaling pathway, which, unregulated activation may lead to chronic inflammation (Gottipati et al., 2007). By modulating the expression of CDK2, CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1, PGG may regulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and therefore, it could explain the mechanism by which PGG exhibited an inhibitory effect on the expression of MCP-5 and Pro MMP-9 pro-inflammatory cytokines in activated microglia cells (described in our previous paper (Mendonca et al., 2017)).

Figure 8 shows a diagram of the proposed mechanism of PGG attenuating effects in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines through the inhibition of CDK2, CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1, consequently reducing neuroinflammation.

Figure 8:

Proposed effects of PGG on the NFƙB and MAPK signaling proteins involved in the release of MCP-5 and Pro MMP-9 cytokines.

| Antibody | Catalog # | Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| BIRC3 | SC-7944 | Santa Cruz |

| CHUK | SC-10760 | Santa Cruz |

| IRAK1 | SC-7883 | Santa Cruz |

| NFKB1 | SC-7178 | Santa Cruz |

| NOD1 | SC-99163 | Santa Cruz |

| CDK2 | SC-748 | Santa Cruz |

| MYC | SC-40 | Santa Cruz |

| GAPDH | SC-25778 | Santa Cruz |

| Phospho IRAK1 | PA5–38631 | ThermoFisher Scientific |

| Phospho CHUK | C84E11 | Cell Signaling |

| Phospho NFKB1 | SC-271908 | Santa Cruz |

| Phospho CDK2 | SC-101656 | Santa Cruz |

Highlights.

PGG modulated the expression of genes and proteins involved in the NFƙB and MAP kinase signaling pathways.

PGG down-regulated the expression of CDK2, CHUK, IRAK1, and NFƙB1 in the transcriptional and protein level in LPS/IFNγ-activated BV-2 microglial cells.

By down-regulating the expression of these genes and proteins, PGG may be modulating the activation of transcription factors that are responsible for the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which consequently induce neuroinflammation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH-National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparity Grants G12 MD007582 and P20 MD 006738.

List of Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s Disease

- Aβ

Amyloid β

- CDKs

Cyclin-dependent kinases

- CHUK

Conserved Helix-Loop-Helix Ubiquitous Kinase

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- IFNγ

Interferon γ

- IRAK1

Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NFKB

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- PBMC

Peripheral mononuclear cells

- PGG

1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-Galloyl-β-D-glucose

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Adli M, Merkhofer E, Cogswell P & Baldwin AS, 2010. IKKα and IKKβ Each Function to Regulate NF-κB Activation in the TNF-Induced/Canonical Pathway. PLoS ONE 5(2): e9428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascolani A, Balestrieri E, Minutolo A, Mosti S, Spalletta G, Bramanti P, Mastino A, Caltagirone C & Macchi B, 2012. Dysregulated NF-κB pathway in peripheral mononuclear cells of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Curr Alzheimer ResVol.: 9(1): 128–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan NG, Lukiw WJ, 2002. Cyclooxygenase-2 and Presenilin-1 Gene Expression Induced by Interleukin-1β and Amyloid β42 Peptide Is Potentiated by Hypoxia in Primary Human Neural Cells. J. Biol. Chem 277, 30359–30367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi E, Barluzzi R, Bocchini V, Mazzolla R & Bistoni F, 1990. Immortalization of Murine Microglial Cells by a v-raf/v-myc Carrying Retrovirus. Journal of Neuroimmunology, Vol.: 27(2–3): 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti B, Stegagno C, Cannella B, Rizzuto N, Moretto G, & Raine CS, 1999. Activation of NF-κB and c-jun transcription factors in multiple sclerosis lesions. Implications for oligodendrocyte pathology. Am J Pathol,155:1433–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonstra J, 2003. Progression through the G1-phase of the on-going cell cycle. J Cell Biochem Vol.: 90(2):244–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno E, Pereira C, Roman KP, Takiguchi M, Kao P, Nogaj LA & Moffet DA, 2013. IAPP Aggregation and Cellular Toxicity Are Inhibited by 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-Galloyl-β-D-Glucose. Amyloid: March; Vol.: 20(1): 34–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Himmeldirk KB, Qian Y, Ren Y, Malki A & Chen X, 2014. Biological and Biomedical Functions of Penta-O-Galloyl-D-Glucose and its derivates. J. Nat. Med Vol.: 68(3):465–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WJ, Chang CY & Lin JK, 2003. Induction of G1 phase arrest in MCF human breast cancer cells by Penta-Galloyl-Glucose through the down-regulation of CDK4 and CDK2 activities and up-regulation of the CDK inhibitors p27 (Kip) and p21 (Cip). Biochem Pharmacol Vol.: 65(11):1777–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhou Y, Mueller-Steiner S, Chen LF, Kwon H, Yi S, Mucke L, Gan L., 2005. SIRT1 protects against microglia-dependent amyloid-beta toxicity through inhibiting NF-kappaB signaling. J Biol Chem 280:40364–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo V, Schurr J, Ball MJ, Pelaez RP, Bazan NG, Lukiw WJ, 2002. Gene expression profiling of 12633 genes in Alzheimer hippocampal CA1: transcription and neurotrophic factor down-regulation and up-regulation of apoptotic and pro-inflammatory signaling. J. Neurosci. Res 70, 462–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs CK, Karlo C, Kao SC & Landreth GE, 2001. β-amyloid stimulation of microglia anti monocytes results in TNFα-dependent expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and neuronal apoptosis. Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 21 (4): 1179–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui JG, Hill JM, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ, 2007. Expression of inflammatory genes in the primary visual cortex of late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport 18, 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiab S, Mazzio E, Eyunni S, McTier O, Mateeva N, Elshami F, & Soliman KFA, 2015. 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-Galloylglucose within Galla Chinensis Inhibits Human LDH-A and Attenuates Cell Proliferation in MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 2015: 276946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djakpo O & Yao W, 2010. Rhus chinensis and Galla Chinensis - Folklore to Modern evidence: Review. Phytother. Res Vol. 24:1739–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsisi N, Darling-Reed S, Lee EY, Oriaku ET & Soliman KF, 2005. Ibuprofen and Apigenin Induce Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest in Activated Microglia. Neurosci. Lett 375: 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman KS, Sahasrabudhe K, Lawlor MD, Wilson SL, Lang CH, Scheuchenzuber WJ, 2011. In vitro and In vivo Inhibition of LPS-Stimulated Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Secretion by the Gallotannin Beta-D-Pentagalloylglucose. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett Vol.: 11(14): 1813–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H, Tabuchi M, Yamaguchi T, Iwasaki K, Furukawa K, Sekiguchi K, Ikarashi Y, Kudo Y, Higuchi M, Saido TC, Maeda S, Takashima A, Hara M, Yaegashi N, Kase Y & Arai HA, 2009. Traditional Medicinal Herb Paeonia suffruticosa and its Active Constituent 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-Galloyl-Beta-D-Glucopyranose have Potent Anti-Aggregation effects on Alzheimer’s Amyloid Beta Proteins In vitro and In vivo. J. Neurochem Vol.: 109(6): 1648–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam R & Jachak SM, 2009. Recent Developments in Anti-Inflammatory Natural Products. Med. Res. Rev Vol.: 29: 767–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendelman HE, 2002. Neural Immunity: Friend or Foe? J. Neurovirol Vol.: 8(6):474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore TD, 2006. Introduction to NF-kappaB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene Vol.: 25:6680–6684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulian D, Li J, Li X, George J, Rutecki P. A., 1994. The impact of microglia-derived cytokines upon gliosis in the CNS. Dev Neurosci: 16: 128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH, 2010. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell Vol.: 140: 918–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottipati S, Rao NL & Fung-Leung WP, 2007. IRAK1: a critical signaling mediator of innate immunity. Cell Signal Vol.: 20(2):269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli M, Goffi F, Memo M, Spano P, 1996. Interleukin-1beta and glutamate activate the NF-kappaB/Rel binding site from the regulatory region of the amyloid precursor protein gene in primary neuronal cultures. J Biol Chem 271:15002–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch UK, 2002. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia Vol.: 40 (2):140–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho GJ, Drego R, Hakimian E & Masliah E, 2005. Mechanisms of cell signaling and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Current Drug Targets: Inflammation and Allergy, vol.: 4 (2): 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, El-Okl M, Williams AL, Cunningham C, Wilcockson D & Perry VH, 2003. Systemic infection, interleukin 1beta, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry Vol.: 74:788–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommes DW, Peppelenbosch MP & Van Deventer SJH, 2003. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signal transduction pathways and novel anti-inflammatory targets. Gut Vol.: 52(1): 144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Lee HJ, Jiang C, Zhang J, Wang L, Zhao Y, Xiang Q, Lee EO, Kim SH, Lu J, 2008. Penta-1,2,3,4,6-O-Galloyl-Beta-D-Glucose induces p53 and inhibits STAT3 in prostate cancer cells in vitro and suppresses prostate xenograft tumor growth in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther Vol.: 7: 2681–2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunot S, Brugg B, Ricard D, Michel PP, Muriel M-P, Ruberg M, Hirsch EC, 1997. Nuclear translocation of NF-κB is increased in dopaminergic neurons of patients with Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 94:7531–7536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana M, Dasgupta S, Liu X, Pahan K, 2002. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor-α expression by CD40 ligation in BV-2 microglial cells. J Neurochem 80(1):197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SE, Hyam SR, Jeong JJ, Han MJ & Kim DH, 2013. Penta-O-Galloyl-β-D-Glucose Ameliorates Inflammation by Inhibiting Myd88/NF-Κb And Myd88/MAPK Signaling Pathways. British Journal of Pharmacology Vol.: 170(5): 1078–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S, 1997. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental Status Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc 15:300–308. [Google Scholar]

- Keating SE, Maloney GM, Moran EM, Bowie AG, 2007. IRAK-2 Participates in Multiple Toll-like Receptor Signaling Pathways to NFκB via Activation of TRAF6 Ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem 282, 33435–33443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knockaert M, Greengard P & Meijer L, 2002. Pharmacological inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases. Trends Pharmacol Sci Vol.: 23: 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy P & Stow JL, 2011. Cytokine release from innate immune cells: association with diverse membrane trafficking pathways. Blood Vol: 7; 118 (1): 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Park HH, Kim JE, Kim JA, Kim YH, Jun CD & Kim SH, 2007. Allose gallates Suppress Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines through Attenuation of NF-kappa B in Human Mast Cells. Planta Med Vol.: 73(8): 769–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, 2004. Regulation of Innate Immunity Signaling and its Connection with Human Diseases. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 3, 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loring JF, Wen X, Lee JM, Seilhamer J, Somogyi R, 2001. A gene expression profile of Alzheimer’s disease. DNA Cell Biol .20, 683–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ, Pelaez RP, Martinez J, Bazan NG, 1998. Budesonide epimer R or dexamethasone selectively inhibit platelet-activating factor-induced or interleukin 1β-induced DNA binding activity of cis-acting transcription factors and cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in human epidermal keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A Vol.: 95, 3914–3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ, Rogaev EI, Bazan NG, 2000b. Potential of transcriptional coordination of nine genes associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Reports 3, 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ, 2004. Gene Expression Profiling in Fetal, Aged, and Alzheimer Hippocampus: A Continuum of Stress-Related Signaling. Neurochem. Res 29, 1287–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ, Cui JG, Marcheselli VL, Bodker M, Botkjaer A, Gotlinger K, Serhan CN, Bazan NG, 2005. A role for docosahexaenoic acid-derived neuroprotectin D1 in neural cell survival and Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest 115, 2774–2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ, Pogue AI, 2007. Induction of specific micro RNA (miRNA) species by ROS-generating metal sulfates in primary human brain cells. J. Inorg. Biochem 101, 1265–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JR, Tang W, Wang H, Vitek MP, Bennett ER, Sullivan PM, Warner DS, Laskowitz DT, 2003. APOE Genotype and an ApoE-mimetic Peptide Modify the Systemic and Central Nervous System Inflammatory Response. J Biol Chem Vol.: 278:48529–48533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendonca P, Taka E, Bauer D, Cobourne-Duval M & Soliman KFA, 2017. The attenuating effects of 1,2,3,4,6 Penta-O-Galloyl-β-D-Glucose on inflammatory cytokines release from activated BV-2 microglial cells. Journal of Neuroimmunology Volume 305, 15 April 2017, Pages 9–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E & Tschopp J, 2008. IRAK2 takes its place in TLR signaling. Nat. Immunol 9, 581–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migheli A, Piva R, Atzori C, Troost D & Schiffer D, 1997. c-Jun, JNK/SAPK kinases and transcription factor NF-κB are selectively activated in astrocytes, but not motor neurons, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1997; 56:1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Matsushita Y, Tohyama Y, Kohsaka S, Kurihara T, 2006. Differential suppression of endotoxin-inducible inflammatory cytokines by nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) inhibitor in rat microglia. Neurosci Lett 401(3):199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill LA, Kaltschmidt C, 1997. NF-kappa B: a crucial transcription factor for glial and neuronal cell function. Trends Neurosci, 20:252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh GS, Pae HO, Choi BM, Lee HS, Kim IK, Yun YG, Kim JD & Chung HT, 2004. Penta-O-Galloyl-Beta-D-Glucose inhibits phorbol myristate acetate-induced interleukin-8 [correction of intereukin-8] gene expression in human monocytic U937 cells through its inactivation of nuclear factor-kappa B. Int. Immunopharmacol Vol.: 4(3): 377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan MH, Lin-Shiau SY, Ho CT, Lin JH & Lin JK, 2000. Suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activity by theaflavin-3, 3′-digallate from black tea and other polyphenols through down-regulation of IkappaB kinase activity in macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol Vol.: 59:357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugazhenthi S, Zhang Y, Bouchard R, Mahaffey G, 2013. Induction of an inflammatory loop by interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha involves NF-kappa B and STAT-1 in differentiated human neuron progenitor cells. PLoS One 8(7): e69585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwood L & Li L, 2008. The involvement of the interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs) in cellular signaling networks controlling inflammation. Cytokine Vol.: 42, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha NP, Teixeira AL, Coelho FM, Caramelli P, Guimarães HC, Barbosa IG, da Silva TA, Mukhamedyarov MA, Zefirov AL, Rizvanov AA, Kiyasov AP, Vieira LB, Janka Z, Palotas A & Reis HJ, 2012. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells derived from Alzheimer’s disease patients show elevated baseline levels of secreted cytokines but resist stimulation with the βamyloid peptide. Mol. Cell. Neurosci Vol.: 49: 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Perez JM, & Morillas-Ruiz JM, 2012. A Review: Inflammatory Process in Alzheimer’s disease, Role of Cytokines. The Scientific World Journal 2012: 756357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidereit C, 2006. IkappaB kinase complexes: gateways to NF-kappaB activation and transcription. Oncogene Vol.: 25:6685–6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M & Baruch K, 2014. The resolution of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration: leukocyte recruitment via the choroid plexus. EMBO J Vol.: 33: 7–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih R-H, Wang C-Y, & Yang C-M, 2015. NF-kappaB Signaling Pathways in Neurological Inflammation: A Mini Review. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 8, 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Das A, Ray SK & Banik NL, 2012. The role of proinflammatory cytokines released from microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Bull Vol.: 87:10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ, Mark RE & Griffin WST, 2004. Microglia and neuroinflammation: a pathological perspective. J Neuroinflammation Vol.: 1(1): 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara K, Kim HD, Jin JJ, Maxwell JA, Li L, Fukuchi K, 2006. Role of toll-like receptor signaling in Aβ uptake and clearance. Brain 129, 3006–3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Schedl P, Song HJ, Garza D, Konsolaki M, 2008. The Toll-->NFkappaB signaling pathway mediates the neuropathological effects of the human Alzheimer’s Abeta42 polypeptide in Drosophila. PLoS One 3, e3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilstra JS, Clauson CL, Niedernhofer LJ & Robbins PD, 2011. NF-κB in Aging and Disease. Aging Dis Vol.: 2(6) :449–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M & Gu Z., 2009. Screening of Bioactive compounds from Moutan cortex and their anti-inflammatory activities in rat synoviocytes. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med Vol.: 6(1): 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu WS; Jeong SJ; Kim JH; Lee HJ; Song HS; Kim MS; Ko E; Lee HJ; Khil JH; Jang HJ; Kim YC, Bae H; Chen CY; Kim SH, 2011. The genome-wide expression profile of 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-Galloyl-β-D-Glucose-treated MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells: Molecular target of cancer metabolism. Mol. Cells Vol.: 32, (2): 123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi E, Rothwarf DM, Delhase M, Hayakawa M & Karin M, 1997. The IkappaB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKalpha and IKKbeta, necessary for IkappaB phosphorylation and NF-kappaB activation. Cell Vol.: 91:243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Li L, Kim SH, Hagerman AE & Lu J, 2009. Anti-cancer, Anti-Diabetic and other Pharmacologic and Biological Activities of Penta-Galloyl-Glucose. Pharm Res Vol.: 26(9): 2066–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Zhou X-W& Wang J-Z, 2016. The dual roles of cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease: update on interleukins, TNF-α, TGFβ, and IFN-γ. Transl Neurodegener 5:7 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Lee HG, Raina AK, Perry G & Smith MA, 2002. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosignals Vol.: 5: 270–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]