Abstract

The treatment landscape of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has changed dramatically in the last few years. The role of chemoimmunotherapy has declined significantly for patients with CLL. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab chemotherapy remains the standard frontline therapy for young fit patients with CLL, especially if IGHV mutated. For older adults, ibrutinib has been shown to be superior to chlorambucil. Hence, the role of chlorambucil monotherapy in the current era in the management of CLL is limited. The combination of chlorambucil and obinutuzumab is an alternative option for patients with comorbidities. For patients with del(17p), ibrutinib has become the standard treatment in the frontline setting. Several phase 3 trials with novel targeted agents, either as monotherapy or in combination, are either ongoing or have completed accrual. The results of many of these trials are expected in the next 1 to 2 years, and they will further help refine the frontline treatment strategy.

Learning Objectives

Understand the data supporting the use of chemoimmunotherapy and targeted therapies in the frontline therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

Understand the stratification of patients based on age, comorbidities, and genomics of the disease to identify optimal frontline treatment

Introduction

The treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has undergone a remarkable evolution in the last few years.1 Up until recently, chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) was the standard treatment of patients with CLL. A better understanding of disease biology has led to significant advances in the treatment of CLL. B-cell receptor inhibitors, such as ibrutinib and idelalisib, and BCL-2 inhibitors, such as venetoclax, are currently approved for patients with CLL. Idelalisib and venetoclax are approved for relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL, whereas ibrutinib is approved for all patients with CLL, including as frontline therapy. Given the emerging data on the targeted agents in both the relapsed and the frontline settings, it is important to reexamine the role of CIT in the frontline therapy of CLL.

The role of CIT in the frontline therapy of CLL

Before rituximab, chemotherapy agents, such as chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, and fludarabine, were commonly used for treatment of CLL.2 With the introduction of rituximab in the late 1990s, regimens, such as fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab (FCR) and bendamustine, rituximab (BR), were developed.3-5 The group at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) reported the initial results of the FCR regimen in patients with treatment-naïve CLL.3 An overall response rate (ORR) of 95% with a complete remission (CR) rate of 72% was noted with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 6.4 years.3 Notably, one-fourth of the patients were unable to complete all 6 cycles of the FCR regimen; this was more common in those with renal dysfunction and those older than 65 years of age. To assess the benefit of rituximab, the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) CLL8 trial randomized treatment-naïve patients with CLL who were physically fit (cumulative illness rating scale [CIRS] score ≤6 and creatinine clearance ≥70 mL/min) to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide (FC) vs FCR.6 The FCR arm had significantly improved CR rate (44% vs 22%, P < .0001), PFS (median 52 vs 33 months, P < .0001), and overall survival (OS; 3-year 87% vs 83%, P = .012), establishing FCR as the standard therapy for young fit patients with CLL.

BR is another commonly used CIT regimen in CLL. Fischer et al5 reported a phase 2 trial of BR in patients with treatment-naïve CLL. Patients with creatinine clearance >30 mL/min were eligible. The authors reported a CR rate of 23% with a median PFS of 34 months. It is important to note that, unlike FCR studies, patients with moderate renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance 30-70 mL/min) did as well as those with normal renal function after receiving BR.

Because BR is less myelosuppressive than FCR, the GCLLSG designed a randomized study with the primary end point of noninferiority of BR vs FCR for PFS. A total of 561 treatment-naïve patients with CLL who were physically fit (CIRS score ≤6 and creatinine clearance ≥70 mL/min) were randomized to receive FCR or BR (the CLL10 trial).7 The FCR arm had a higher CR rate (39.7% vs 30.8%, P = .03) with significantly improved PFS (median 55.2 vs 41.7 months, P < .001). There was no difference in OS. The FCR regimen, not unexpectedly, led to a higher rate of myelosuppression and infectious complications. Notably, among patients older than or equal to 65 years, the PFS for BR vs FCR was not different, and BR led to fewer infectious complications. The CLL10 trial established FCR as the treatment of choice for younger fit patients with CLL. For patients 65 years old or older, if CIT is deemed appropriate, BR is appropriate. For patients with moderate renal dysfunction, BR is preferred over FCR. Several studies have investigated modifications to the FCR regimen, such as lower doses of FCR, dose-intensifying rituximab, replacing fludarabine with pentostatin, or adding alemtuzumab.8 However, none of these strategies have proven to be superior to the standard FCR regimen.

Given the advent of novel targeted therapies, it is important to identify subgroups of patients who derive the most benefit from FCR. Patients with del(17p) respond poorly to CIT, with a median PFS of <1 year in the frontline setting.6 The MDACC group reported that patients with mutated IGHV have a 10-year PFS of ∼55% after receiving frontline FCR.9 This compares favorably to 10-year PFS of ∼10% for the IGHV-unmutated group. Importantly, a plateau was seen on the PFS curve after 10 years for the IGHV-mutated cohort. Assessment of minimal residual disease (MRD) at the end of treatment can help identify patients who may achieve long-term disease-free remission after FCR.10-12 Similar data have been reported by other groups.13,14 Rossi et al14 used del(17p), del(11q), and IGHV mutation status to categorize patients receiving frontline FCR into 3 prognostic subgroups. Patients with del(17p), independent of co-occurring del(11q) or unmutated IGHV, had the worst PFS and OS, followed by patients with either del(11q) and/or unmutated IGHV [without del(17p)], and followed by patients with none of these 3 high-risk prognostic markers. These studies suggest that, for the subset of patients with mutated IGHV [without del(17p)], FCR treatment of 6 cycles provides long-term disease remission in the majority of patients, and hence, this remains an attractive option for this subgroup of patients. There are only limited data available on targeted therapies in the frontline setting for this group of patients (see below). Hence, until more data are available for the targeted therapies in the frontline setting for younger patients, the FCR regimen should remain the treatment of choice for IGHV-mutated young fit patients.15 One important concern with the use of the FCR regimen is the development of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The MDACC group reported up to 5% risk of therapy-related MDS/AML after receiving FCR.16 In the CLL8 trial (comparing FC with FCR), the risk of therapy-related MDS/AML was lower at 1.5%, with no difference in the treatment arms.13

Recently, there have been efforts to develop combinations of CIT with targeted therapies. The MDACC group reported on a CIT + ibrutinib regimen called ibrutinib, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and obinutuzumab (GA101) (iFCG regimen). This trial included young fit patients with mutated IGHV without del(17p).17 Three cycles of iFCG regimen were administered followed by response assessment. (1) Patients achieving CR with bone marrow MRD-negative (by flow cytometry with a sensitivity of 10−4) remission received 3 additional cycles of ibrutinib and obinutuzumab followed by 6 cycles of ibrutinib monotherapy. (2) All other patients received 9 cycles of ibrutinib and obinutuzumab. At 1 year, for patients who had achieved bone marrow MRD-negative remission, ibrutinib was discontinued. Notably, unlike standard FCR, where 6 cycles of chemotherapy are administered, only 3 cycles of chemotherapy were given in the iFCG regimen. After 3 cycles of iFCG regimen, bone marrow MRD-negative remission was achieved in 87% of the patients. This compares favorably with 26% bone marrow MRD-negative remission noted after 3 cycles of FCR for a similar patient population in a historical comparison.18 The CR/complete remission with incomplete count recovery (CRi) rate was 44% after 3 cycles of the iFCG, which improved to 78% after 3 additional cycles of ibrutinib + obinutuzumab. A higher rate of myelosuppression was noted with the iFCG regimen compared with the historical FCR cohorts. The group at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute reported on the combination of ibrutinib with 6 cycles of standard FCR (iFCR regimen) for patients with treatment-naïve CLL.19 Patients with both mutated and unmutated IGHV were eligible. A total of 83% of the patients achieved bone marrow MRD-negative remission, with 63% achieving CR/CRi. Although these studies have small numbers of patients with limited follow-up, the rates of bone marrow MRD-negative remission and CR/CRi rates are numerically significantly higher than what has been reported with the standard FCR regimen.

For older adults (patients older than or equal to 65 years of age) and patients with significant comorbidities, chlorambucil was previously considered standard of care. The GCLLSG conducted a phase 3 trial (the CLL11 trial) where treatment-naïve patients with comorbidities were randomized to receive 1 of 3 regimens: chlorambucil vs chlorambucil + rituximab vs chlorambucil + obinutuzumab.20,21 Chlorambucil monotherapy was inferior to either of the antibody arms in terms of PFS and OS, hence establishing the role of CD20 antibody in older adults with CLL. In a recent update, after a median follow-up of 5 years, chlorambucil + obinutuzumab had superior PFS (median PFS, 28.9 vs 15.7 months, P < .001) and OS (median OS, not reached vs 73.1 months, P = .02) compared with chlorambucil + rituximab.22 This trial established the combination of chlorambucil + obinutuzumab as standard frontline treatment of older adults with CLL.

Ofatumumab, a type 1 CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb), has also been combined with chlorambucil for frontline treatment of patients with CLL.23 In a phase 3 trial (the COMPLEMENT-1 trial), 447 patients, deemed ineligible to receive FCR, were randomized to receive chlorambucil ± ofatumumab. The combination of chlorambucil + ofatumumab led to a significant improvement in PFS (median PFS, 22.4 vs 13.1 months, P < .001).

In a recently reported phase 3 trial (the MABLE study), patients with treatment-naïve CLL who were deemed ineligible for fludarabine-based treatment were randomized to BR vs chlorambucil + rituximab.24 A total of 241 patients were randomized with a median age of 72 years. The primary end point, CR rate, was higher in the BR arm vs the chlorambucil + rituximab arm (24% vs 9%, P = .002). The median PFS was longer for the BR arm (39.6 vs 29.9 months, P = .003). Notably, the median PFS with the chlorambucil + rituximab arm in the MABLE trial is longer than the chlorambucil + rituximab arm of the CLL11 trial, likely due to the higher dose of chlorambucil in the MABLE trial and the lower incidence of comorbidities for the patients enrolled in the MABLE trial.

The role of novel targeted agents in the frontline therapy of CLL

Ibrutinib, a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, is approved for patients with CLL. The approved dose for patients with CLL is 420 mg once daily. Ibrutinib was initially investigated in a phase 1/2 clinical trial (the PCYC-1102/1103 study), in which 31 patients with treatment-naïve CLL (older than or equal to 65 years) and 101 patients with R/R CLL were enrolled.25,26 For the treatment-naïve cohort, the median age was 71 years (range, 65-84). After a median follow-up of ∼5 years, 55% of patients in the treatment-naïve cohort remained on ibrutinib, with 6% coming off study due to disease progression and 19% coming off study due to an adverse event. In the overall study, atrial fibrillation (grade 3 or higher) was noticed in 8% of the patients. The ORR was 87% for the treatment-naive cohort. The CR rate in the treatment-naïve group improved with time from ∼10% at 1 year to 29% at 5 years. The estimated 5-year PFS was 92% for the treatment-naïve cohort. In the R/R cohort, the median PFS for all patients was 51 months, with patients with del(17p) and those with complex karyotype having the shortest PFS rates at 26 and 31 months, respectively. The group at the National Institute of Health (NIH) recently reported 5-year follow-up of patients who received ibrutinib monotherapy.27 Patients were included in either the TP53 cohort [presence of del(17p) by fluorescence in situ hybridization in ≥10% cells and/or TP53 mutation] or the elderly cohort (patients older than or equal to 65 years). A total of 35 patients in the TP53 cohort and 18 patients in the elderly cohort were treatment naïve. The estimated 5-year PFS for the treatment-naïve patients within the TP53 cohort was 74.4% (5-year OS was 85.3%). These results are very favorable compared with median PFS of <12 months with frontline CIT in patients with del(17p).6,28 None of the patients in the treatment-naïve elderly cohort in the NIH study have progressed/died. These trials, albeit with a small number of patients in the frontline setting, establish the long-term safety and efficacy of ibrutinib.

In a phase 3 trial (the RESONATE-2), 269 patients (older than or equal to 65 years) with treatment-naïve CLL were randomized to receive ibrutinib vs chlorambucil.29 The PFS was significantly longer for the ibrutinib arm (median not reached vs 18.9 months for chlorambucil, P < .001; 2-year PFS, 89% for ibrutinib vs 34% for chlorambucil).30 The OS was significantly better for the ibrutinib arm. This trial led to the approval of ibrutinib in the frontline setting. There is an ongoing randomized phase 3 trial comparing ibrutinib + obinutuzumab with chlorambucil + obinutuzumab (PCYC-1130, the iLLUMINATE trial) that has completed enrollment; this trial has met its primary end point of improvement in PFS for the ibrutinib + obinutuzumab arm (AbbVie press release May 24, 2018; https://news.abbvie.com/news/imbruvica-ibrutinib-plus-gazyva-obinutuzumab-phase-3-illuminate-trial-for-first-line-therapy-chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia-cll-patients-met-primary-endpoint.htm). It should be noted that, at the time of this writing, the data for the iLLUMINATE trial have not yet been presented or reported.

Mato et al31 conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study to assess patterns of care with the use of ibrutinib in the “real-world” setting. A total of 616 patients were included (13% first line, 87% R/R); the majority (88%) received ibrutinib outside of a clinical trial. At a median follow-up of 17 months, 41% of patients (24% first line, 43% R/R) discontinued ibrutinib; the median time to ibrutinib discontinuation was 7 months, and the most common reason for treatment discontinuation was drug-related toxicities. These discontinuation rates for ibrutinib are higher than what is noted in clinical trials.

The role of combination of ibrutinib with a CD20 mAb remains under investigation. Michallet et al32 treated 135 physically fit patients (CIRS score ≤6) with treatment-naïve CLL with a combination of ibrutinib for 9 months and obinutuzumab for the first 6 months (the ICLL-07 FILO study). Patients with del(17p) or TP53 mutation were excluded. Patients underwent response assessment after 9 cycles of ibrutinib. (1) Patients achieving CR with bone marrow MRD-negative remission received 6 additional cycles of ibrutinib. (2) All other patients receive 4 cycles of FC, ibrutinib, and obinutuzumab. The median age was 62 years (range, 35-80). Of the 123 evaluable patients, 41% achieved CR. The CR rate with the combination of ibrutinib + obinutuzumab in this trial seems favorable compared with ibrutinib monotherapy (∼10% at 1 year), although the patient population is different (younger CIT-eligible patients in the ibrutinib + obinutuzumab trial; older patients or patients with comorbidities in the ibrutinib monotherapy trials). Notably, the majority of patients (87%) remained MRD positive after receiving ibrutinib + obinutuzumab. Woyach et al33 treated treatment-naïve patients who were older than or equal to 65 years (<65 years if CIT ineligible) with acalabrutinib + obinutuzumab. A total of 19 treatment-naïve patients were treated. After a median follow-up of 18 months, an ORR of 95% with a CR rate of 16% was noted. Burger et al34 reported a phase 2 randomized study of ibrutinib ± rituximab for patients with CLL (87% were R/R, 13% were treatment naïve with TP53 aberrations) and showed no improvement in PFS with the addition of rituximab. As expected, the rituximab arm had less pronounced reactive lymphocytosis. A total of 21% of patients on the ibrutinib arm and 28% of patients on the ibrutinib + rituximab arm achieved a CR; the time to CR was shorter for the combination arm.

Several ongoing phase 3 trials will help further clarify the role of ibrutinib vs CIT for patients with CLL. The ECOG-E1912 trial randomized 519 physically fit patients (ages 18-70 years) with treatment-naïve CLL to FCR vs ibrutinib + rituximab (NCT02048813). The ALLIANCE A041202 trial randomized 523 patients (older than or equal to 65 years) with treatment-naïve CLL to BR vs ibrutinib + rituximab vs ibrutinib. Both of these trials have completed accrual, and results are awaited. The ALLIANCE trial will also help assess the role of CD20 mAb in combination with ibrutinib.

Novel BTK inhibitors, such as acalabrutinib (ACP-196) and zanubrutinib (BGB-3111), are also being explored in phase 3 trials in the treatment-naïve patient population. In a phase 3 trial (the ACE-CL-007), patients older than or equal to 65 years (or younger than 65 years with comorbidities) are randomized to receive chlorambucil + obinutuzumab vs acalabrutinib + obinutuzumab vs acalabrutinib monotherapy (NCT02475681). In a phase 3 trial (BGB-3111-304), patients older than or equal to 18 years deemed unfit to receive FCR are randomized to receive BR vs zanubrutinib (NCT03336333). The results of both of these trials are pending.

Venetoclax is an oral BCL2 inhibitor, and it is approved for patients with R/R CLL in combination with rituximab. Due to risk of tumor lysis syndrome, venetoclax is administered in a weekly dose escalation schedule starting at 20 mg daily to a target dose of 400 mg daily. In a phase 1 study, a total of 116 patients with R/R CLL with a median of 3 prior therapies were treated.35 An ORR of 79%, with a CR rate of 20%, was noted. Venetoclax + rituximab was investigated in 49 patients with R/R CLL.36 ORR was 86%, with a CR rate of 51%. Remarkably, MRD negativity in the bone marrow was achieved in 57% of the patients. A total of 11 patients who had MRD-negative remission discontinued venetoclax and remained MRD negative with a median follow-up of 9.7 months after stopping venetoclax. In a recently reported phase 3 trial (the MURANO trial), 389 patients with R/R CLL were randomized to BR vs venetoclax + rituximab.37 The 2-year PFS was significantly longer for the venetoclax + rituximab arm vs BR (84.9% vs 36.3%, P < .001). The 2-year OS was significantly higher for the venetoclax + rituximab arm.

There are limited data on the use of venetoclax in the treatment-naïve patients with CLL. Flinn et al38 reported outcomes of 32 patients with treatment-naïve CLL who received 6 cycles of venetoclax + obinutuzumab followed by 6 cycles of venetoclax monotherapy. Additional venetoclax could be given after 1 year of treatment of patients in partial remission or MRD positive. The median age was 63 years (range, 47-73). All 32 patients had a response, with 56.3% achieving CR/CRi. All patients achieved MRD-negative remission in the peripheral blood. MRD negativity in the bone marrow was noted in 74% of the evaluable samples (62.5% on intention-to-treat analysis). Two patients had disease progression at around month 14 [both patients had del(17p) and were MRD positive in bone marrow at 1 year].

To test the efficacy of the combination of venetoclax + obinutuzumab, the GCLLSG initiated a phase 3 trial (the CLL14 trial) for patients with treatment-naïve CLL and coexisting medical conditions (CIRS score >6 and/or creatinine clearance < 70 mL/min). Patients were randomized to receive either 6 cycles of chlorambucil + obinutuzumab followed by 6 cycles of chlorambucil or 6 cycles of venetoclax + obinutuzumab followed by 6 cycles of venetoclax. In the run-in phase, 13 patients were treated.39 A total of 58% patients achieved a CR. Of the 12 patients who were evaluated for MRD in peripheral blood at the end of treatment, 11 (92%) were MRD negative. The randomized phase of the CLL14 trial has completed accrual of 432 patients, and the results are awaited.

Preliminary data have been reported with the use of ibrutinib + venetoclax in the frontline setting by the MDACC group.40 A total of 40 patients (median age, 64.5 years) with high-risk CLL [93% were unmutated IGHV, TP53 aberration, or del(11q)] received ibrutinib for 3 months followed by the addition of venetoclax. At 6 months of the combination, 75% of the patients had achieved CR/CRi, and 45% were MRD negative in the bone marrow. These numbers improved to 80% CR/CRi and 80% MRD negative at 9 months of the combination. Rogers et al41 investigated a three-drug regimen (ibrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab) in patients with treatment-naïve CLL. A total of 25 patients were treated at a median age of 59 years. After 8 months of the combination therapy, 52% of the patients achieved CR/CRi, and ∼60% were MRD negative in the bone marrow.

In a phase 3 trial by the United Kingdom group (the FLAIR trial), treatment-naïve patients with CLL are randomized to 1 of 4 treatment arms: (1) FCR, (2) ibrutinib + rituximab, (3) ibrutinib, and (4) ibrutinib + venetoclax. In a phase 3 trial by the GCLLSG (the CLL13 trial), treatment-naïve patients with CLL are randomized to 1 of 4 treatment arms: (1) FCR/BR (based on age younger than or equal to 65 or older than 65 years), (2) venetoclax + obinutuzumab, (3) venetoclax + rituximab, and (4) venetoclax + ibrutinib + obinutuzumab. Both of these trials are currently enrolling patients, and results are awaited.

PI3Kδ inhibitors, such as idelalisib, are currently approved in combination with rituximab for patients with R/R CLL. [In Europe, idelalisib is also approved for patients with del(17p) or TP53 mutation who cannot be treated with any other therapy.] The development of idelalisib in the treatment-naïve patient population was halted due to increased infectious complications and immune-mediated toxicities. Umbralisib (TGR-1202) is a more specific PI3Kδ inhibitor,42 and it seems to have a more favorable toxicity profile than idelalisib.43 The UNITY trial is a phase 3 trial randomizing patients with CLL (including both treatment-naïve and R/R patients) to chlorambucil + obinutuzumab vs umbralisib + ublituximab (a novel CD20 mAb; NCT02612311). This trial has completed accrual, and results are awaited.

Patient stratification and treatment

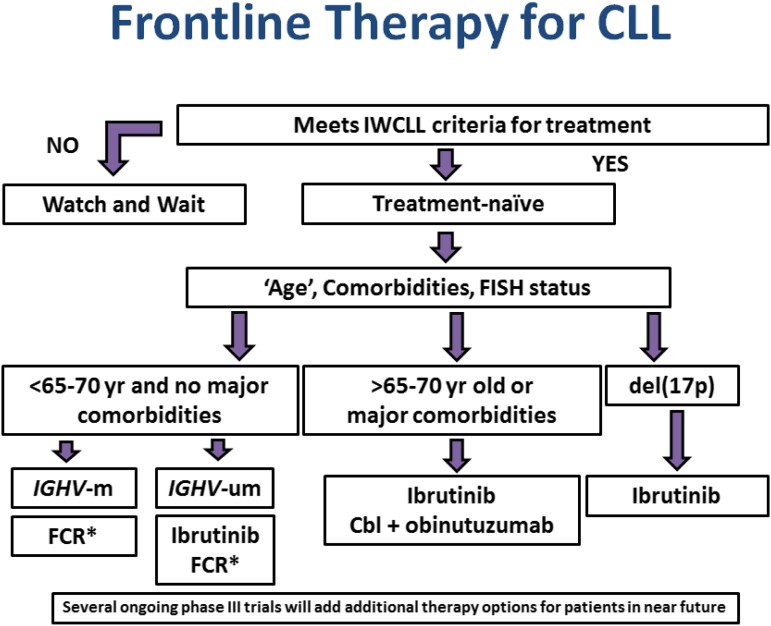

Based on the data provided above, patients with CLL can be divided into the following groups for frontline therapy (Figure 1). For all patients, enrollment in a clinical trial remains a preferred approach.

Young “fit” patients. These patients are typically younger than 65 years of age with no major comorbidities. For these patients, very limited data are available with targeted therapies. The ECOG-E1912 trial has completed accrual, and results are pending. Until additional data are available to help direct treatment choices, FCR treatment remains the standard therapy for this group of patients. Because the long-term outcomes are most favorable with the IGHV-mutated subgroup, FCR chemotherapy is recommended for IGHV-mutated patients without TP53 aberrations. This group constitutes approximately one-third of the young fit patients and around 8% to 10% of all patients (all age groups) requiring frontline therapy. For the IGHV-unmutated subgroup, given continuous relapse with CIT but limited data with targeted therapy to date, clinical trials are preferred, but targeted therapy (such as ibrutinib) is also an option (with the caveat that limited clinical data are available with ibrutinib for this group of patients). For “fit” patients older than 65 years of age for whom CIT is deemed appropriate, BR is an appropriate option. For patients with moderate renal dysfunction, BR is favored over FCR.

Older adults (older than or equal to 65 years) or patients with comorbidities. In this patient population, ibrutinib has been shown to be superior to chlorambucil (the RESONATE-2 trial), although chlorambucil has not been the standard of care since the CLL11 trial. The iLLUMINATE trial comparing ibrutinib + obinutuzumab with chlorambucil + obinutuzumab has met its primary end point of improvement in PFS, although the data are not yet presented. The data currently point toward ibrutinib monotherapy or chlorambucil + obinutuzumab combination, which may soon be replaced by ibrutinib + obinutuzumab combination as the current standard for this patient population. It is important to note that limited data are available for ibrutinib in patients with significant comorbidities, and chlorambucil + obinutuzumab may be appropriate for this group of patients. Unlike the CLL11 trial, both the RESONATE-2 and the iLLUMINATE trials enrolled older adults, irrespective of comorbidities. The CLL14 trial is currently evaluating the combination of venetoclax + obinutuzumab compared with chlorambucil + obinutuzumab in patients with comorbidities (CIRS score >6 and/or creatinine clearance <70 mL/min). High cost of targeted therapies may also lead to preference for chlorambucil + obinutuzumab for many patients. Several pivotal phase 3 trials targeting this patient population have been initiated/completed, including with the use of novel BTK inhibitors (acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib), PI3Kδ inhibitor (umbralisib), and BCL2 inhibitor (venetoclax). The results of these trials are awaited and will likely add additional treatment options for this patient population.

Patients with del(17p). Chemotherapy has no role for this patient population. Ibrutinib is the current standard treatment of these patients. Results of ongoing phase 3 trials as described above will likely expand therapy options for this group of patients as well.

Figure 1.

Selection of frontline therapy for CLL. *BR is preferred over FCR for patients with moderate renal dysfunction and patients 65 years or older who are deemed appropriate for FCR therapy. Cbl, chlorambucil; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; IWCLL, International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia.

Conclusions

The frontline therapy of CLL has already changed dramatically in the last few years and will continue to evolve, because several phase 3 trials with novel targeted agents will be reported in the next 1 to 2 years. Early data with the combination of venetoclax and CD20 mAbs and the combination of venetoclax and ibrutinib look promising. Several trials with targeted agents are investigating time-limited treatment (such as 1 or 2 years of therapy with targeted agents) as opposed to indefinite therapy, with the goal of achieving MRD-negative remission. A time-limited treatment approach, if successful, will be advantageous to the patients (less drug exposure and fewer side effects), and it will also help curtail treatment costs.

References

- 1.Jain N, O’Brien S. Targeted therapies for CLL: practical issues with the changing treatment paradigm. Blood Rev. 2016;30(3):233-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gribben JG, O’Brien S. Update on therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(5):544-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keating MJ, O’Brien S, Albitar M, et al. . Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4079-4088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer K, Cramer P, Busch R, et al. . Bendamustine combined with rituximab in patients with relapsed and/or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3559-3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer K, Cramer P, Busch R, et al. . Bendamustine in combination with rituximab for previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(26):3209-3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. ; German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Bahlo J, et al. ; German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG). First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL10): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):928-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain N, O’Brien S. Initial treatment of CLL: integrating biology and functional status. Blood. 2015;126(4):463-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson PA, Tam CS, O’Brien SM, et al. . Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab treatment achieves long-term disease-free survival in IGHV-mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(3):303-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson PA, Peterson CB, Strati P, et al. . Serial minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring during first-line FCR treatment for CLL may direct individualized therapeutic strategies [published online ahead of print 17 April 2018]. Leukemia. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0132-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Böttcher S, Ritgen M, Fischer K, et al. . Minimal residual disease quantification is an independent predictor of progression-free and overall survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multivariate analysis from the randomized GCLLSG CLL8 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(9):980-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimier N, Delmar P, Ward C, et al. . A model for predicting effect of treatment on progression-free survival using MRD as a surrogate end point in CLL. Blood. 2018;131(9):955-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer K, Bahlo J, Fink AM, et al. . Long-term remissions after FCR chemoimmunotherapy in previously untreated patients with CLL: updated results of the CLL8 trial. Blood. 2016;127(2):208-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi D, Terzi-di-Bergamo L, De Paoli L, et al. . Molecular prediction of durable remission after first-line fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;126(16):1921-1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JR, Kay NE. Chemoimmunotherapy is not dead yet in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(26):2989-2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamini O, Jain P, Trinh L, et al. . Second cancers in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who received frontline fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab therapy: distribution and clinical outcomes. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(6):1643-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain N, Thompson PA, Burger JA, et al. . Ibrutinib, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and obinutuzumab (GA101) (iFCG) for first-line treatment of patients with CLL with mutated IGHV and without TP53 aberrations. Blood. 2017;130:495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strati P, Keating MJ, O’Brien SM, et al. . Eradication of bone marrow minimal residual disease may prompt early treatment discontinuation in CLL. Blood. 2014;123(24):3727-3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davids MS, Kim HT, Brander DM, et al. . A multicenter, phase II study of ibrutinib plus FCR (iFCR) as frontline therapy for younger CLL patients. Blood. 2017;130:496. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. . Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1101-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goede V, Fischer K, Engelke A, et al. . Obinutuzumab as frontline treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: updated results of the CLL11 study. Leukemia. 2015;29(7):1602-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goede V, Fischer K, Dyer MJ, et al. Overall survival benefit of obinutuzumab over rituximab when combined with chlorambucil in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and comorbidities: final survival analysis of the CLL11 study. In: Proceedings from the European Hematology Association Annual Meeting; June 2018; Stockholm, Sweden. Abstract S151. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillmen P, Robak T, Janssens A, et al. ; COMPLEMENT 1 Study Investigators. Chlorambucil plus ofatumumab versus chlorambucil alone in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (COMPLEMENT 1): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1873-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michallet AS, Aktan M, Hiddemann W, et al. . Rituximab plus bendamustine or chlorambucil for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: primary analysis of the randomized, open-label MABLE study. Haematologica. 2018;103(4):698-706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. . Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Brien S, Furman RR, Coutre S, et al. . Single-agent ibrutinib in treatment-naïve and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a 5-year experience. Blood. 2018;131(17):1910-1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahn IE, Farooqui MZH, Tian X, et al. . Depth and durability of response to ibrutinib in CLL: 5-year follow-up of a phase 2 study. Blood. 2018;131(21):2357-2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strati P, Keating MJ, O’Brien SM, et al. . Outcomes of first-line treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia with 17p deletion. Haematologica. 2014;99(8):1350-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. ; RESONATE-2 Investigators. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2425-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barr P, Robak T, Owen CJ, et al. . Updated efficacy and safety from the phase 3 Resonate- 2 study: ibrutinib as first-line treatment option in patients 65 years and older with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;128:234. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mato AR, Nabhan C, Thompson MC, et al. . Toxicities and outcomes of 616 ibrutinib-treated patients in the United States: a real-world analysis. Haematologica. 2018;103(5):874-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michallet A-S, Dilhuydy M-S, Subtil F, et al. High rate of complete response but minimal residual disease still detectable after first-line treatment combining obinutuzumab and ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): ICLL07 FILO trial. In: Proceedings of the European Hematology Association Annual Meeting; June 2018; Stockholm, Sweden. Abstract S804. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woyach JA, Awan FT, Jianfar M, et al. . Acalabrutinib with obinutuzumab in relapsed/refractory and treatment-naive patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the phase 1b/2 ACE-CL-003 study. Blood. 2017;130:432. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burger JA, Sivina M, Ferrajoli A, et al. . Randomized trial of ibrutinib versus ibrutinib plus rituximab (Ib+R) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Blood. 2017;130(suppl 1):427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. . Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):311-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seymour JF, Ma S, Brander DM, et al. . Venetoclax plus rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(2):230-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, et al. . Venetoclax-rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1107-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flinn IW, Gribben JG, Dyer MJS, et al. . Safety, efficacy and MRD negativity of a combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia - results from a phase 1b study (GP28331). Blood. 2017;130:430. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Fink AM, et al. . Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129(19):2702-2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jain N, Thompson PA, Ferrajoli A, et al. . Combined venetoclax and ibrutinib for patients with previously untreated high-risk CLL, and relapsed/refractory CLL: a phase II trial. Blood. 2017;130:429. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogers KA, Huang Y, Stark A, et al. . Initial results of the phase 2 treatment naive cohort in a phase 1b/2 study of obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, and venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;130:431. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lampson BL, Brown JR. PI3Kδ-selective and PI3Kα/δ-combinatorial inhibitors in clinical development for B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26(11):1267-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davids M, Flinn I, Mato A, et al. . an integrated safety analysis of the next generation PI3Kδ inhibitor umbralisib (TGR-1202) in patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2017;130:4037. [Google Scholar]