Abstract

Religiosity and spirituality are influential experiences that buffer adverse effects of stressors. Spirituality typically declines during adolescence, although not universally. Using Latent Class Growth Analysis, we examined changes in spiritual connectedness among 188 early (52% female; M age = 10.77, SD = 0.65 years) and 167 middle (N = 167; 56% female; M age = 13.68, SD = 0.82 years) predominantly African American adolescents participating in a 4-year longitudinal study. Three distinct profiles of spiritual connectedness emerged: low and steady, moderate with declines over the study period, and high and steady. Profile distributions varied across developmental level: there were more early adolescents in the high and steady profile and more middle adolescents in the decliner profile. Youth in the high and steady profile evidenced more goal-directedness and life satisfaction and more effective emotion management and coping strategies than youth in other profiles. Contributions to the positive development literature are discussed.

Keywords: Spiritual Connectedness, African American, Profiles, Coping, Goal Directedness, Emotion Regulation

Introduction

Religiosity and spirituality are protective resources that buffer against adverse effects of stressful life events (Cotton et al. 2006; Lee and Neblett 2017). Despite this positive role of religiosity and spirituality, researchers have found that with time, adolescents’ beliefs and participation in religious activities decline (Desmond et al. 2010). However, the decline is not universal, suggesting distinct group differences among individuals in this age group that has implications for their well-being. During adolescence, individuals tend to engage in spiritual explorations and make commitments that have enduring implications throughout the lifespan. The period of adolescence therefore becomes a sensitive stage for spiritual development (Good and Willoughby 2008). In spite of the sensitivity of the adolescent period of development for spirituality, little is known about patterns of spirituality and how trends change during this stage of life. The present study examines profiles of change in spiritual connectedness during adolescence, as well as associations between the profiles and well-being in African American youth.

The terms religiosity and spirituality are overlapping concepts that are defined and measured differently in the scientific community (Dyson et al. 1997). Religiosity is commonly defined as the outward expression of the relationship with the sacred through a formal and organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols (Moreira-Almeida and Koenig 2006). It is measured by one’s level of belief in God and frequency of attendance at religious services, and practice of prayers and meditation (Cotton et al. 2006). Spirituality, on the other hand, is defined as an awareness of the existence and experience of inner feelings and beliefs in connection to the sacred, which in turn gives the individual purpose, meaning, value of life, inner peace, and harmonious interpersonal relationships (Fisher 2011). It is measured by well-being, peace, and comfort that is derived from faith and spiritual connectedness as well as religious coping (Cotton et al. 2006). Unlike spirituality, which is an internal experience that goes beyond physical limits of time and space, religiosity is an external practice within a social entity or institution which is defined by boundaries and characterized by goals that are nonspiritual in focus such as culture, economic, political, and social (Miller and Thoresen 2003). Another area of contention surrounds the terminology used to connote religion. Terms such as religiosity and religiousness have been used to connote the practice of religion at the individual level (Miller and Thoresen 2003). This theorization is similar to William James’s (1902/1961) conceptualization of religiosity which highlighted the private form of religiosity and is distinct from the public form that tends to be overt expression of belief in the sacred through an organized institution. Despite the differences between religiosity and spirituality, these terms are connected in that they both focus on a belief in the sacred (Hill and Pargament 2003; Moreira-Almeida and Koenig 2006).

The role of religiosity and spirituality to the well-being of the African American population has been emphasized by several researchers. In 2014, the Pew Research Center reported that 83% of Blacks indicated that they believed in God, 75% identified religion as important in their life, and 47% attended religious services at least once a week. Additionally, a significant number of African-Americans also identify God as a core aspect of their coping and rely on their connection with the sacred during difficult times (Whitley 2012). These figures show the significance of religiosity and spirituality to African Americans. This significance can be traced to the role of the Black Church and religious traditions in the fight for freedom and building social capital (i.e., education, health, social welfare institutions) among African American communities. Dating back to the era of slavery, churches were used as the focal points for communal relationship, education, and fellowship among black slaves (Avent and Cashwell 2015). Through these gatherings, slaves learned to read and their knowledge base of scriptures increased. This in turn led to frustrations with organized religion as the slaves perceived Christianity as a mechanism used to advance oppression. The church subsequently was used as means to bring about change as slaves fought for their own churches out of the desire to have a place of worship of their own and to escape discrimination during religious gatherings. The separation of Blacks from the Methodist Denomination to form the predominantly African American Black Methodist church became the major civil rights protest of African Americans (Lincoln and Mamiya 1990) and further laid the foundation for other civil rights protests. In these Black churches, slaves experienced temporal freedom, relief, and an escape from the pressures and brutality that they experienced on the plantations (Wilmore 1998). The church became the primary source of support and change during trying times. Furthermore, the church was strongly instrumental in the fight for civil rights, as it was used as a platform for activists to promote equal rights for African Americans (Chandler 2010), created opportunities for financial independence both at the individual and group levels, and enhanced individuals’ self-worth which was lacking outside the church (Douglas and Hopson 2001). Presently, the church plays a central role in the building and organization of African American communities. Black Churches serve as sites for education, perform social welfare functions, and provide spiritual and political leadership (Hendricks et al. 2012). Among children and adolescents, the church provides instrumental support in the form of academic support programs and mentorship that ameliorate the effects of stressful life events such as neighborhood violence and school dropout on depressive symptoms (Billingsley 1999). Churches also provide opportunities for involvement in activities such as volunteer work, musical training, and mentoring that enhance self-esteem and self-efficacy (Mattis and Mattis 2011).

Adolescence is a challenging stage involving the transition from childhood to adulthood, and from dependence to independence. During this stage the church, and spirituality more generally, can function as a protective resource against several adverse life challenges (Lee and Neblett 2017). Aside from major physical and psychological changes that may cause some adolescents significant distress (Kelsey and Simons 2014), African Americans in the United States experience further challenges brought on by institutional racism. As a result, African American adolescents experience more stress and are more vulnerable to develop mental illness (e.g., depression) compared to adolescents of other racial groups (Adkins et al. 2009; Lee and Neblett 2017). Despite the challenges experienced by African Americans adolescents, not all of these youth develop adverse outcomes.

A number of scholars investigating different racial and cultural groups have documented the protective role of spirituality on adolescent well-being. For example, research reviews indicate that spirituality has a direct positive effect on adolescent health, although this tends to be moderate (Cotton et al. 2006). Previous studies have found that higher levels of spirituality were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms and fewer risk-taking behaviors (Cotton et al. 2005; Holder et al. 2000), as well as lower risk of suicide (Greening and Stoppelbein 2002). Spirituality was associated with other indicators of well-being, including life satisfaction (Holder et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2012; Sawatzky et al. 2009), hope (Souza et al. 2015), happiness (Holder et al. 2010), and global quality of life (Sawatzky et al. 2009). Specifically, among African American adolescents, both intrinsic spirituality and extrinsic religiosity buffered against stressful life events and depressive symptoms, although the protective effects tended to diminish with time (Lee and Neblett 2017). Although levels of religious practice and of spiritual connectedness are sometimes considered in tandem, internal beliefs in God, or spiritual connectedness also have been studied alone. For example, Kliewer and Murrelle (2007) found that a personal belief in God was the strongest protective factor against substance use and substance use problems in a large study of youth from Central America. Smith (2003) identified nine mechanisms through which religious practice exerts a positive and constructive influence on the lives of American adolescents. These distinct factors are further grouped into three larger dimensions as moral order (consisting of the provision of moral directives, spiritual experiences, and role models), learned competencies (consisting of the provision of community and leadership skills, coping skills, and cultural capital) and social organizational ties (which include provision of social capital, network closure, and extra-community skills). Although religious practice more commonly involves engagement in a religious community that provides space and opportunity for these mechanisms to emerge, the formal structure is not necessarily required. Youth with strong spiritual connectedness can also find positive influence in their lives through these mechanisms, as they interpret moral questions, grow their competencies and coping skills, and build less formal social ties through their self-established spiritual framework (Dill 2017).

Despite the benefits of spirituality, research over the last decade has shown that during adolescence many youth, particularly youth living in the United States, lose a sense of spiritual connectedness and their commitment to religious institutions wanes. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health from 1994 to 2002, Lee and Neblett (2017) found a decline in both extrinsic religiosity (service attendance and participation in youth activities) and intrinsic spirituality (prayer and religious importance) among non-Hispanic African American adolescents. The rate of decline among high and low profiles of both intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity was similar. Denton and colleagues (2008), using data from the National Study of Youth and Religion’s longitudinal survey, reported a decline in various measures of religiosity as adolescents aged, although the pattern of decline was dependent on the aspect of religiosity. They found that over a three-year period (2002–2005), more adolescents reported uncertainty about their religious beliefs. Additionally, participation in religious services and practices occurred less often with time. However, assessment of self-reported religiosity remained steady or increased with time. Furthermore, cross-sectional data among six countries (Canada, The Czech Republic, England, Israel, Poland and Scotland) on the spiritual health of adolescents (defined as an aspect of health which pertains to awareness of the sacred qualities of life experiences and is characterized by connection to self, others, nature, and a sense of meaning of life) also showed lower levels of spiritual health among older compared to younger adolescents (Michaelson et al. 2016). The decline was persistent across both genders and for all six countries. Reynolds et al. (2013) also found that older adolescents tended to use more negative religious coping (spiritual discontentment, negative reappraisal of God’s powers, or demonic reappraisal) than did younger adolescents.

Decline in adolescents’ religiosity and spirituality has been associated with the emergence of abstract thought and development of complex skills for self-regulation in adolescence (Good and Willoughby 2008) as well as continued development of the brain which allows adolescents to engage more extensively in the significance of spirituality and religiosity to their lives as they age (King et al. 2014). The loss of interest in religiosity and spirituality over time may explain why these factors are more protective against risky behaviors (Holder et al. 2000) and depressive symptoms (Lee and Neblett 2017) in younger than in older adolescents. Given the known protective effects of religious involvement on adolescent health and well-being (Jennings et al. 2014), declines in spiritual connectedness also may be a contributing factor to the rise in suicides among late adolescents, to substance abuse, or to other mental or physical health problems during this developmental period. Other studies also have shown demographic differences based on gender, with girls attending religious services more often and viewing religion as important than boys (Michaelson et al. 2016; Smith 2005; Wallace et al. 2003). These demographic trends show diversity among adolescents with respect to religiousness and spirituality-diversity that has important implications for adolescents’ mental and physical health. This body of research has shown that not all adolescents experience a loss of religiosity and spirituality, and among those who do, the rate of decline is not universal. This finding suggests the possibility of distinct group differences that characterize the patterns of change in spiritual connectedness during this developmental period. These differences have implications for how adolescents cope with the stressors in their lives and ultimately their health and well-being.

Adolescence is a sensitive stage for spiritual development given that it is a period when youth tend to engage in spiritual exploration, convert, or make spiritual commitments that endure throughout the life span (Good and Willoughby 2008). However, little is known about patterns of spiritual connectedness during adolescence. Further, although nationally representative studies consistently show that African Americans report more religious involvement and spirituality than non-Hispanic Whites (Chatters et al. 2009; Gallup and Lindsay 1999), there is still considerable religious variability among African Americans (Taylor et al. 2004). Within the African American community, research has revealed that women, older adults, married individuals, and those living in the South tend to have higher rates of religious involvement than their counterparts (Taylor et al. 2014). Education and income levels also influence the ways in which African American individuals express their spiritual connectivity and engage in religious practice (Taylor et al. 2014). Most research on religious variability within the African American and other minority communities, however, has been conducted with adults. Thus, an important but unexplored question concerns not only whether distinct profiles of spiritual connectedness could be identified in a sample of adolescents, but whether these profiles could be identified in a sample of low-income, predominantly African American adolescents. Further, few studies have examined the developmental timing of changes in spiritual connectedness during the course of adolescence, especially among African American youth. If distinct profiles of spiritual connectedness are observed in African American youth, do these profiles look the same for youth in early adolescence versus middle adolescence? Further, how are these profiles associated with coping and adjustment?

Compass et al. (2001, p. 89) view coping as a voluntary effort and defined it as “... one aspect of a broader set of processes that are enacted in response to stress.” Compass et al. further argued that coping in children and adolescents may follow a developmental course, may change in relation to development and situational demands, and include both overt behaviors and covert cognitive responses that are determined by the stressful situation. When faced with challenges, adolescents may choose from a repertoire of coping responses (e.g., distraction, avoidance, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, positive reappraising, information seeking, etc.) to manage the stress (Compass et al. 2001; Vaillant 1998). These strategies often are categorized differently (Compass et al. 2001; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). For example, problem-focused coping includes strategies that employ behavioral activities such as planning and decision making whereas emotion-focused coping involves expression of emotions and altering one’s expectations (Brougham et al. 2009). The choice of strategies depends on the adolescent’s temperament, developmental level, and the nature and context of the stressor involved (Holen et al., 2012). Strategies chosen may yield positive or negative results. For example, strategies such as problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, and positive reappraisal of stress were associated with positive outcomes whereas strategies such as avoidance, social withdrawal, and self-blame were associated with adverse outcomes (Compass et al., 2001).

Both positive reframing coping and avoidant coping are relevant to Smith’s (2003) perspective on the effects of religiosity and to the experiences of low-income African American individuals. Reframing coping is a cognitive strategy that includes positive and optimistic thinking (Ayers and Sandler 1996). Also referred to as reappraisal, this coping strategy can reduce the emotional impact of a situation (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Reframing is a core feature of Chen and Miller’s (2012) “Shift-and-Persist” theory, which explains why a subset of individuals low in socioeconomic status show reduced physiological responses to stress and a lower risk of disease. Avoidant coping, which is not a core feature of the shift and persist theory and which includes avoidant actions (staying away from the problem) as well as trying not to think about the problem and wishing things were better, has been associated with worse mental and physical health in a large number of studies with both adults and youth (Compas et al. 2001). However, among African American youth from low-resourced environments, some scholars have found that the negative effects of avoidant coping on adjustment are only evident when the effects of active coping, and in some cases, social support coping, are considered simultaneously (Gaylord-Harden et al. 2010). Further, some aspects of avoidant coping, such as staying away from the problem, may be quite adaptive for youth living in low-income neighborhoods because although these strategies are “avoidant” they keep youth out of harm’s way. Despite some avoidant strategies requiring active decision-making or initiative by an adolescent, they are still considered avoidant because the individual is staying away from the problem they are faced with.

Current Study

The first purpose of the present study was to determine, using a person-centered approach, whether distinct profiles of changes in spiritual connectedness over time could be identified in a sample of low-income, largely African American adolescents. Such findings would be helpful in identifying differential factors that influence adolescents to either stay spiritually connected or disconnected or become spiritually connected or disconnected as they navigate this developmental stage. In addition to identifying distinct profiles of spiritual connectedness in our sample, a second purpose of the present study was to determine if profiles differed by developmental stage. That is, we asked whether patterns of change in spiritual connectedness were similar across early and middle adolescence, or if they differed, and if so, in what ways. A final purpose of the present study was to determine if profiles were differentially associated with well-being. Specifically, we focused on how the profiles differed in terms of coping, goal-directedness, caregiver-rated emotion management, and life satisfaction. This aim was influenced by Smith’s (2003) theorizing about the mechanisms through which religious and spiritual experiences affect adolescent health and well-being. Of particular interest to the present study is how spirituality offers various beliefs and practices that adolescents can use to cope with stress, process difficult emotions, solve problems, and resolve conflicts, which in turn enhance adolescents’ well-being and life capacities.

We did not have a priori expectations regarding the type of distinct profiles of spiritual connectedness in our sample, however, we did expect that at least two profiles would emerge. This hypothesis was based on past research showing the heterogeneity in patterns of change in spiritual beliefs across adolescence (Denton et al. 2008). We also anticipated that if declines in spiritual connectedness characterized one or more profiles, they would be more prevalent among middle adolescents than among early adolescents. This hypothesis was based on the timeframe for the emergence of abstract thought, assuming that youth would have established this cognitive ability by middle adolescence and would have had time to question and adapt their spiritual beliefs and practices to fit their new cognitive framework which they would not yet have had time to do right at the start of early adolescence. Finally, we anticipated that youth with the most robust levels of spiritual connectedness over time would engage in more reframing and avoidant coping, would evidence higher levels of goal-directedness, be rated higher in emotion management, and would report more life satisfaction relative to youth in other profiles.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 355 youth and their maternal caregivers who participated in a four-time point longitudinal study (with one year between time points) on stress, coping, and adjustment, which took place in a midsized city in the mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. At time 1, all youth participants were enrolled in either the 5th (N = 188; 52% female; Mage = 10.77, SD = 0.65 years) or 8th grades (N = 167; 56% female; Mage = 13.68, SD = 0.82 years). This two-cohort design was employed to follow youth in their transition into middle school or high school, respectively. At time 4, most youth were in the 8th or 11th grades. The majority of participants were African American (92%). Most (>85%) of the maternal caregivers were the youth participants’ biological mothers. Most (88%) of the youth reported they lived with their biological mother most of the time, while only 20% reported they lived with their biological father most of the time. Socioeconomic status (SES) varied, but most of the sample came from low SES backgrounds. Median weekly household income at time 1 was $401–500, with 17% reporting household earnings of $200 or less per week. The most common reports on maternal education level were no high school diploma (23%), high school diploma or General Education Diploma (GED) (31%) or some college but no degree (28%). Thirteen percent of the maternal caregivers had an Associate’s or Vocational degree; Only 9% of maternal caregivers had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Maternal caregivers tended to have high religious attendance rates: 24% reported attending services more than once a week, and 18% reported attending services weekly, while only 6% reported never attending religious services. The remaining 52% fell somewhere between ‘rarely’ and ‘more than once a month’.

Procedure

The Institutional Review Board at the first author’s institution approved all study procedures. Families were recruited through community events and agencies, by participant referral, and through flyers posted door-to-door in low-income neighborhoods. To be eligible, participants had to be the female caregiver of a 5th or 8th grade child during the first timepoint of data collection, and speak English. Sixty-three percent of the eligible families who were approached enrolled in the study. This figure is better than those of many community-based studies for recruiting participants from disadvantaged neighborhoods (Luthar and Goldstein 2004; Tingen et al. 2013). Caregivers provided written consent and adolescents provided written assent for participation in the study. Interviews were conducted face-to-face with visual aids in families’ homes, unless otherwise requested by the family. Two trained research team members interviewed the caregiver and adolescent separately in different rooms. At time 1, female staff interviewed 224 adolescents (175 females and 49 males) and male staff interviewed 131 adolescents (18 females and 115 males). All female caregivers were interviewed by female staff. Responses of male and female adolescents were compared on all time 1 scales reported by adolescents (e.g., spiritual connectedness, goal directedness, positive reframing and avoidant coping, and life satisfaction) separately for female staff and male staff using t-tests. None of the comparisons were significant (all ts < 1.29, all ps > .20), indicating no systematic biases by interviewer gender. Regarding race, African American staff interviewed 198 youth (183 African American / Black, 8 White, and 7 other races), and Caucasian staff interviewed 157 youth (143 African American / Black, 12 White, and 2 other races). African American staff interviewed 281 maternal caregivers (256 African American / Black, 17 White, and 8 other races), and Caucasian staff interviewed 74 maternal caregivers (70 African American / Black, 3 White, and 1 other race). Responses of African American and Caucasian adolescents were compared on all time 1 scales reported by adolescents separately for African American and Caucasian staff using i-tests. With one exception, which was marginal (t = 1.92. p = .095) all t values were less than .90 (all ps > .37). Parallel analyses were conducted for the responses of African American and Caucasian maternal caregivers. None of the comparisons were significant (all ts < 1.30, all ps > . 19), indicating no systematic biases by interviewer race. Interviews lasted approximately 2.5 hours and families were compensated $50 in Wal-Mart gift cards for each time of participation.

Measures

Spiritual connectedness.

Spiritual connectedness, a measure of intrinsic religiosity, was self-reported at each of the four time points with the 7-item subscale from the Personal Experience Inventory (PEI; Winters and Henly 1989). The PEI is a youth self-report measure that documents the onset, nature, degree, and duration of chemical involvement and other risk or protective behaviors in youth, including spiritual connectedness, a known protective factor against substance use. It has been validated across a number of populations, including African American adolescents (Winters et al. 2004). Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Items include: “I believe there is a spiritual force that can help me with my problems,”“I am helped by prayer or meditation,”“I feel a spiritual force working in my life,”“I have faith in a power greater than me,”“I have had a powerful religious or spiritual experience,”“I am not a religious person” (reverse-coded), and “I rely on religion when I have problems.” Items were scored such that higher total scores indicated greater spiritual connectedness. Cronbach alphas ranged between .85 to .90 across the four study time points.

Coping efforts.

Coping efforts were self-reported at each of the four time points with two higher-order factors from the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (CCSC; Ayers and Sandler 1996). We utilized the 12-item higher order factor of positive reframing coping, consisting of the subscales positivity, optimism, and control, and the 12-item higher order factor of avoidant coping, consisting of the subscales avoidant actions, repression, and wishful thinking. All items were rated on a scale from 1 (didn‘t do this at all) to 4 (did this a lot); higher scores indicate more frequent use of the given coping strategy. Sample items for the positive reframing coping factor include: “Remind yourself that you are better off than a lot of other kids,” “Tell yourself that things would get better,” and “Tell yourself that you could handle this problem.” Sample items for the avoidant coping factor include: “Avoid it by going somewhere else,” “Try to ignore it,” and “Wish that things were better.” Cronbach alphas ranged from .90 to .91 across the four study time points for positive reframing coping, and from .85 to .88 for avoidant coping.

Goal-directedness.

Goal-directedness was self-reported at each of the four time points with 7-item subscale from the Personal Experience Inventory (PEI; Winters and Henly, 1989). A sample item is “It is important for people my age to think about the future.” Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater goal-directedness. Cronbach alphas ranged from .74 to .79 across the study period.

Emotion management.

Emotion regulation and emotional lability were assessed at each of the four time points with the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields and Cicchetti 1997). The ERC is a well-validated, parent-report measure of child emotion management patterns. There are two subscales: a 15-item lability scale and an 8-item emotion regulation scale. Items are rated on a scale from 1 (rarely/never) to 4 (almost always)’, higher scores indicate greater emotion regulation abilities or higher lability depending on the subscale. A sample item from the emotion regulation subscale is “responds positively to neutral or friendly overtures by adults.” A sample item from the lability subscale is “is prone to angry outbursts/tantrums easily.” Cronbach alphas ranged from .69 to .73 for emotion regulation and from .84 to .87 for lability across the study period.

Life satisfaction.

Life satisfaction was self-reported at each of the four time points using the Life Satisfaction Scale (Valois et al. 2001). This scale was designed to assess youth’s satisfaction with specific areas of their life. The original scale consists of six questions, all beginning with the stem “I would describe my satisfaction with my...” Stem endings are: (1) family life, (2) friendships, (3) school experience, (4) myself, (5) where I live, and (6) overall life. We used items 1, 2, 4, and 6 as these items were theoretically most strongly linked to spiritual connectedness. Items are rated on a scale from 1 (terrible) to 7 (delighted); higher scores indicate greater life satisfaction. Cronbach alphas ranged from .70 to .77 across the study period.

Data Analyses

Following the guidelines outlined in Jung and Wickrama (2008), we utilized Latent Class Growth Analysis (LCGA) in Mplus 8 (Muthen and Muthen 1998–2017) in order to determine if distinct profiles of changes in spiritual connectedness over our study period could be identified in our sample of low-income, largely African American adolescents. Because a second purpose of our study was to determine if profiles differed by developmental stage, we conducted these analyses separately by grade cohort. Consistent with Jung and Wickrama’s (2008) recommendations, as an initial step we first specified a single-class latent growth curve model with spiritual connectedness at each of the four time points as the dependent variables. A full-information maximum likelihood algorithm was used to handle missing data.

Next, we specified an unconditional latent class model without covariates or distal outcomes, again with spiritual connectedness at each of the four time points as the dependent variables. As recommended by Jung and Wickrama, we specified our LCGA models with no within-class variance. We examined solutions for 2, 3, and 4-class models, using Bayesian information criteria (BIC) values and the Lo et al. (2001) likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT) to determine the best fitting models. Lower BIC values and significant LMR-LRT tests generally indicated better fit. Once we had determined the best fitting models for each grade cohort, we specified a conditional latent class model with adolescent age and gender as covariates in separate models. We then saved the predicted class for each adolescent from the Mplus output.

In order to examine the final aim of our study, which was to determine if profiles were differentially associated with coping and well-being, we conducted a series of repeated measures Analyses of Covariance (ANCOVAs) with the profiles as the predictor variable, and coping, goal-directedness, or well-being as the outcome variables. These analyses controlled for grade cohort, adolescent gender, household income, and maternal education. We examined between-subjects’ effects for profile to determine any overall differences in variables by spiritual connectedness profile, which were followed by planned contrasts comparing youth in the “high and steady” profile to youth in the other profiles. We also examined profile X time interactions to determine if changes in outcome differed by profile at different rates or patterns. We imputed missing data prior to conducting these analyses in order to preserve power.

Results

Attrition analyses

Seventy percent of the sample was retained across the four time points. Youth who had all time points of data (N = 247) were compared with youth who were missing data at time 4 (N = 108) on child gender using Chi square analysis, and on child age, spiritual connectedness, positive reframing and avoidant coping, emotion regulation, emotional lability, goal directedness, and life satisfaction at time 1 using t-tests. Chi square analyses [X2 (1) = 4.44, p = .038] indicated that females (74%) were more likely to remain in the study than were males (64%). T-tests with age as the outcome indicated that youth who remained in the study were younger at time 1 than youth who attrited by an average of 6 months, t(353) = 2.72, p = .007 (M= 11.98, SD = 1.57 ;M= 12.49, SD = 1.72). There were no differences at time 1 on spiritual connectedness, t(344) = −0.81. p = .42, positive reframing coping, t(344) =0.95, p = .34, avoidant coping, t(342) = 0.54, p = .59, emotion regulation, t(353) = 1.13, p = .26, emotional lability, t(353) = 1.88, p = .06, goal directedness, t(346) = 0.39, p = .70, or life satisfaction, t(349) = 0.98, p = .33.

Descriptive Statistics on the Constructs and Associations with Gender and Age

Table 1 presents descriptive information on the study constructs by developmental stage. As seen in the table, there was a general trend for spiritual connectedness to decline across the four time points of the study. T-tests were used to evaluate gender and developmental stage differences in the study variables. Gender differences were evident in avoidant coping, goal directedness, and emotion management, but not at every time point. There were no gender differences in spiritual connectedness, positive reframing coping, or life satisfaction. With the exception of emotional lability, in all cases where there were differences, females reported engaging in more of the behavior than males. Significant differences included time 1 avoidance coping, t(342) = 2.25, p = .025 (Ms = 32.7 vs=30.8); time 4 avoidance coping, t(240) = 2.50, p = .013 (Ms = 30.0 vs 27.2); time 1 emotional lability, t(353) = 2.62, p = .009 (Ms = 29.6 vs 31.7); time 2 emotion regulation, t(316) = 2.01, p = .045 (Ms = 25.4 vs 24.5); and goal-directedness at time 3, t(267) = 2.80, p = .005 (Ms = 25.2 vs 24.0) and time 4, t(245) = 2.77, p = .006 (Ms = 25.2 vs23.8). In contrast, there were few significant developmental differences on the study variables, and all significant differences were observed at time 1 or time 2. There were significant differences on time 1 positive reframing coping, t(344) = 2.97, p = .033 and time 1 avoidant coping, t(342) = 3.65, p < .001 (Ms = 33.3 vs 30.1), with early adolescents reporting more coping than middle adolescents. Early adolescents also reported greater life satisfaction than middle adolescents at time 2, t(312) = 1.99, p = .048, as well as higher levels of spiritual connectedness at time1 t(344) = 4.41, p < .001, and time 2, t(300) = 2.11, p = .036 (see Table 1 for descriptive values).

Table 1.

Descriptive Information on the Study Variables by Developmental Stage

| Variable | Early Adolescents | Middle Adolescents | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Spiritual Connectedness (T1) | 3.08 | .62 | 2.75 | .71 |

| Spiritual Connectedness (T2) | 2.89 | .80 | 2.69 | .76 |

| Spiritual Connectedness (T3) | 2.62 | .84 | 2.48 | .81 |

| Spiritual Connectedness (T4) | 2.57 | .91 | 2.53 | .90 |

| Positive Reframing Coping (T1) | 32.45 | 8.16 | 30.12 | 8.22 |

| Positive Reframing Coping (T2) | 30.70 | 9.09 | 30.67 | 8.37 |

| Positive Reframing Coping (T3) | 29.77 | 8.51 | 28.20 | 8.31 |

| Positive Reframing Coping (T4) | 28.60 | 9.10 | 29.24 | 9.24 |

| Avoidant Coping (T1) | 33.25 | 8.00 | 30.21 | 7.81 |

| Avoidant Coping (T2) | 31.17 | 8.55 | 29.59 | 8.16 |

| Avoidant Coping (T3) | 29.89 | 8.18 | 28.20 | 7.86 |

| Avoidant Coping (T4) | 28.84 | 8.88 | 28.68 | 8.39 |

| Goal-Directedness (T1) | 24.06 | 3.46 | 24.65 | 3.25 |

| Goal-Directedness (T2) | 24.20 | 3.95 | 24.70 | 4.02 |

| Goal-Directedness (T3) | 24.51 | 3.67 | 24.80 | 3.58 |

| Goal-Directedness (T4) | 24.64 | 3.86 | 24.24 | 4.09 |

| Emotion Regulation (T1) | 25.50 | 3.83 | 24.74 | 3.67 |

| Emotion Regulation (T2) | 25.21 | 3.79 | 24.72 | 3.78 |

| Emotion Regulation (T3) | 24.75 | 3.67 | 24.83 | 3.66 |

| Emotion Regulation (T4) | 24.48 | 3.75 | 24.43 | 4.32 |

| Emotional Lability (T1) | 30.21 | 7.36 | 31.08 | 7.88 |

| Emotional Lability (T2) | 29.51 | 7.10 | 29.29 | 7.37 |

| Emotional Lability (T3) | 29.26 | 6.52 | 28.91 | 6.98 |

| Emotional Lability (T4) | 29.31 | 6.86 | 28.68 | 7.74 |

| Life Satisfaction (T1) | 33.19 | 6.07 | 33.27 | 4.94 |

| Life Satisfaction (T2) | 34.81 | 5.59 | 33.53 | 5.77 |

| Life Satisfaction (T3) | 33.64 | 5.86 | 33.71 | 5.38 |

| Life Satisfaction (T4) | 34.28 | 5.41 | 33.65 | 5.19 |

Note. Emotion regulation and emotional lability were reported by maternal caregivers; other study constructs were self-reported by adolescents

Latent Class Growth Analysis: Patterns of Spiritual Connectedness in Adolescence

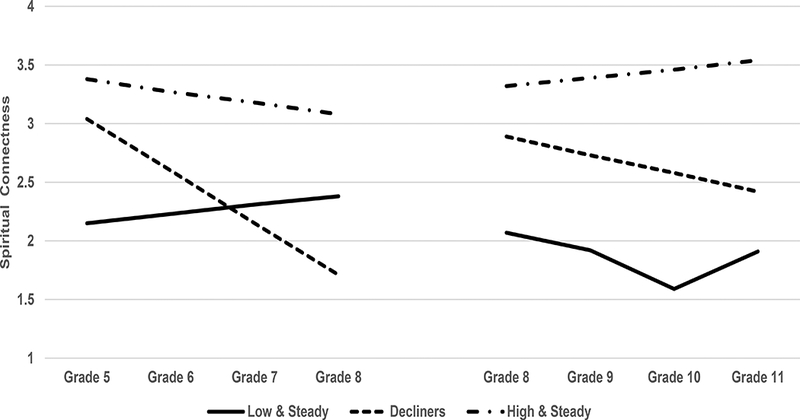

Table 2 presents model fit statistics for latent class growth analysis models specifying two to four classes for early and middle adolescents. For early adolescents, the BIC values were similar across the 2, 3, and 4 class solutions. The significant BLRT test, in concert with the lower ABIC for a 3-class solution relative to a 2-class solution, and the pattern of ACPs for the 3-class solution relative to a 4-class solution, favored a 3-class solution. For middle adolescents, the BIC value was lowest in the 3-class solution, and the VLMR-LRT, Adjusted LRT, and BLRT tests were all significant, making this an obvious choice. Further, the 4-class solution only had two cases. Figure 1 shows the plots of estimated means for each of the 3-class solutions by development stage. As seen in the figure, each developmental stage had a group of youth who displayed a “high and steady” profile; a group of “decliners” whose sense of spiritual connectedness waned over the 3-year period of the study; and a group of youth who were “low and steady” - who started low and remained low. For both developmental cohorts, the slope for the “decliners” was significant, while the slope for the “low and steady” profile was not. Among the “high and steady” group, the slope for early adolescents was slightly negative and significant, while the slope for the middle adolescents was slightly positive and marginally significant. However, the distribution of youth across the profiles within each developmental cohort varied significantly, χ2 (2) = 38.8, p < .001. Among early adolescents, 56% were in the high and steady profile, 28% were decliners, and 16% were in the low and steady profile; for middle adolescents, 24% were located in the high and steady profile, 47% were decliners, and 29% were in the low and steady group.

Table 2.

Model Fit Statistics for Latent Class Growth Analysis Models Specifying Two to Four Classes for Early and Middle Adolescents

| Model Fit Information | Early Adolescents | Middle Adolescents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| N of free parameters | 9 | 12 | 15 | 9 | 12 | 15 |

| Loglikelihood | −1874.23 | −1866.21 | −1859.18 | −1573.60 | −1557.21 | −1553.79 |

| Information Criteria | ||||||

| Akaike’s information criteria (AIC) | 3766.46 | 3756.42 | 3748.36 | 3165.21 | 3138.42 | 3137.58 |

| Bayesian information criteria (BIC) | 3795.59 | 3795.26 | 3796.91 | 3193.27 | 3175.84 | 3184.35 |

| Sample-Size Adjusted BIC (ABIC) | 3767.08 | 3757.25 | 3749.40 | 3164.77 | 3137.84 | 3136.86 |

| ACPs | .86 - .86 | .78 - .84 | .70 - .85 | .89 -.91 | .81 - .86 | .83 - .93 |

| VLMR – LRT | −1913.60 | −1874.23 | −1866.21 | −1626.45 | −1573.60 | −1557.21 |

| p<.001 | p = .51 | p = .09 | p = .002 | p = .03 | p = .047 | |

| Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted LRT Test | 74.03 | 15.08 | 13.22 | 99.23 | 30.78 | 6.42 |

| p<.001 | p = .53 | p = .10 | p = .002 | p = .04 | p = .054 | |

| Parametric Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) | −1913.60 | −1874.23 | −1866.21 | −1626.45 | −1573.60 | −1557.21 |

| p < .001 | p < .001 | p = .01 | p < .001 | p < .001 | p = .19 | |

Note. N = 188 for early adolescents and 167 for middle adolescents. ACPs = average latent class probabilities for most likely latent class membership; VLMR-LRT = Vuong-Lo-Mendell Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test.

Figure 1.

Estimated means from the Latent Class Growth Analyses (LCGA) for both the early and middle adolescent cohorts. N = 188 for early adolescents and 167 for middle adolescents. For early adolescents (M = .08, SE = .10. p = .46) and middle adolescents (M = −. 16, SE = . 10, p = . 11) the slope for the “low and steady” profile was not significant. In contrast, for both early and middle adolescents, the slopes for the “decliners” was significant (M = −.44. SE = .19.p = .02 for early adolescents; M = −.16, SE = .05, p = .001 for middle adolescents). For early adolescents, the slope for the “high and steady” profile was slightly negative and significant (M = −.10, SE = .04, p = .006); for middle adolescents the slope for the “high and steady” profile was slightly positive and marginally significant (M= .07, SE = .04, p = .06). Estimated means were obtained from the Mplus output

In order to determine if adolescent age or gender had significant direct effects on either the intercept or the slope in the above analyses, we ran conditional latent class models with adolescent age and adolescent gender added as covariates. Age and gender were included in separate models to preserve power. For the early adolescents, gender was not associated with the intercept (Est = −.83, SE= 1.35. p = .54) or with the slope (Est = −.59, SE = .89, p = .51). Likewise, for the early adolescents, age was not associated with the intercept (Est =−.19. .SE = .74, p = .80) or with the slope (Est = −.42, SE= .23, p= .07). For middle adolescents, gender was associated with the intercept (Est = 2.53, SE= .97, p = .009) but not with the slope (Est = −.01, SE= .38, p = .98). A similar patten was observed with age. Age was associated with the intercept (Est = −1.27, SE= .55, p = .02) but not with the slope (Est = .14, SE =.26, p = .60).

Analyses of Covariance Linking Spiritual Connectedness Profiles with Coping and Adjustment

We used ANCOVAs to assess our hypotheses that adolescents with a “high and steady” profile of spiritual connectedness would evidence more adaptive coping, higher levels of goal-directedness and caregiver-rated emotion regulation, and greater life satisfaction relative to youth in other profiles. For all models, profile membership was the grouping variable with three levels, and grade cohort, adolescent gender, household income, and maternal education were included as control variables. We considered both between subjects’ effects of profile on our outcomes, which tells us if there are overall differences by profile on coping and adjustment, and profile X time interactions, which indicated if changes in outcome differed by profile at different rates or patterns.

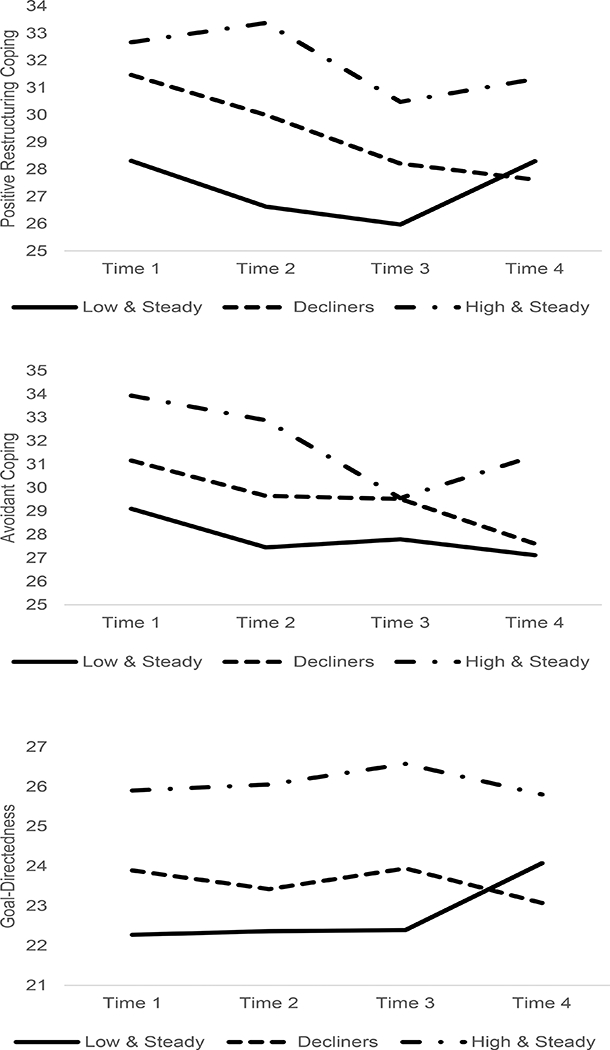

Coping outcomes were examined first. For the ANCOVAs with positive reframing coping as the outcome, the between-subjects’ effect was significant indicating that overall levels of positive reframing coping differed by patterns of spiritual connectedness (see Table 3 for results of the ANCOVAs). Planned contrasts indicated that youth in the low and steady and decliner profiles had lower levels of positive reframing coping than youth in the high and steady profile. There was a multivariate effect of time and a multivariate profile X time interaction. These results indicate that positive reframing coping changed over time, and that the pattern of these changes differed by profile membership. Figure 2 displays the changes in positive reframing coping over time as a function of profile membership. As seen in the Figure 2, Panel a, while there was some variation from year to year in positive reframing coping among all groups, youth in the decliner profile demonstrated the most significant decline in this type of coping over time.

Table 3.

Summary of Analyses of Covariance Models Linking Spiritual Connectedness Profiles with Study Outcomes

| ANCOVA Results | Reframing Coping |

Avoidant Coping |

Emotion Regulation |

Emotional Lability |

Goal- Directedness |

Life Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Subjects Effects: |

||||||

| Gender |

F(1, 348) =

3.07, p = .08 |

F(1, 348) =

6.12, p = .01 |

F(1, 348) =

2.89, p = .09 |

F(1, 348) =

1.42, p = .23 |

F(1, 348) =

6.18, p = .01 |

F(1, 348) =

0.12, p = .73 |

| Grade level |

F(1, 348) =

0.28, p = .60 |

F(1, 348) =

0.57, p = .45 |

F(1, 348) =

0.01, p = .91 |

F(1, 348) =

1.79, p = .18 |

F(1, 348) =

16.55, p < .001 |

F(1, 348) =

0.07, p = .79 |

| Household income |

F(1, 348) =

1.84, p = .18 |

F(1, 348) =

1.11, p = .29 |

F(1, 348) =

1.00, p = .32 |

F(1, 348) =

2.40, p = .12 |

F(1, 348) =

0.01, p = .91 |

F(1, 348) =

1.37, p = .24 |

| Maternal Education |

F(1, 348) =

5.92, p = .02 |

F(1, 348) =

6.53, p = .01 |

F(1, 348) =

10.94, p = .001 |

F(1, 348) =

5.57, p = .02 |

F(1, 348) =

9.35, p = .002 |

F(1, 348) =

0.80, p = .37 |

| Connectedness Profile |

F(2, 348)

= 15.42, p < .001 |

F(2, 348)

= 14.53, p < .001 |

F(2, 348) =

8.73, p < .001 |

F(2, 348) =

8.02, p < .001 |

F(2, 348)

= 59.96, p < .001 |

F(2, 348)

= 11.13,p < .001 |

| Planned Contrasts: | ||||||

| Low &

Steady vs High & Steady Profile |

−4.66 CI[−6.34,− 2.98] p < .001 |

−4.06 CI[−5.59, −2.54] p < .001 |

−1.05 CI[−1.92,−0.19] p = .02 |

2.81 CI[1.03,4.59] p = .002 |

−3.31 CI[−3.96, −2.65] p < .001 |

−2.76 CI[−3.96, −1.57] p < .001 |

| Decliners vs

High & Steady Profile |

−2.64 CI[−4.12,−1.15] p = .001 |

−2.44 CI[−3.79, −1.08] p < .001 |

−1.61 CI[−2.37,0.84] p = .001 |

2.96 CI[1.39,4.54] p < .001 |

−2.50 CI[−3.08, −1.92] p < .001 |

−1.75 CI[−2.81, −0.69] p = .001 |

| Multivariate Effects: | ||||||

| Time |

F(3, 346) =

6.11, p < .001 |

F(3, 346) =

7.74, p < .001 |

F(3, 346) =

11.11, p < .001 |

F(3, 346) =

2.76, p = .04 |

F(3, 346) =

0.99, p = .40 |

F(3, 346) =

0.91, p = .44 |

| Time X gender |

F(3, 346) =

0.43, p = .73 |

F(3, 346) =

2.78, p = .04 |

F(3, 346) =

1.53, p = .21 |

F(3, 346) =

4.77, p = .003 |

F(3, 346) =

4.51, p = .004 |

F(3, 346) =

3.92, p = .009 |

| Time X grade level |

F(3, 346) =

4.58, p = .004 |

F(3, 346) =

3.20, p = .02 |

F(3, 346) =

3.16, p = .03 |

F(3, 346) =

2.41, p = .07 |

F(3, 346) =

3.26, p = .02 |

F(3, 346) =

2.69, p = .04 |

| Time X income |

F(3, 346) =

1.23, p = .30 |

F(3, 346) =

0.62, p = .60 |

F(3, 346) =

2.15, p = .09 |

F(3, 346) =

1.55, p = .20 |

F(3, 346) =

1.49, p = .22 |

F(3, 346) =

2.48, p = .06 |

| Time X education |

F(3, 346) =

4.50, p = .004 |

F(3, 346) =

2.60, p = .05 |

F(3, 346) =

3.07, p = .03 |

F(3, 346) =

1.28, p = .28 |

F(3, 346) =

3.49, p = .02 |

F(3, 346) =

0.40, p = .75 |

| Time X profile |

F(6, 692) =

2.20, p = .04 |

F(6, 692) =

2.54, p = .02 |

F(6, 692) =

0.68, p = .68 |

F(6, 692) =

1.92, p = .08 |

F(6, 692) =

5.52, p < .001 |

F(6, 692) =

0.61, p = .73 |

Note. Significant effects are bolded for emphasis Emotion regulation and emotional lability were reported by maternal caregivers; other constructs were self-reported by adolescents.

Figure 2.

Interactions of spiritual connectedness profile membership and time for positive reframing coping (panel a), avoidant coping (panel b), and goal directedness (panel c) controlling for grade level, adolescent gender, household income, and maternal caregiver education level

Turning next to avoidant coping as the outcome, the between-subjects’ effect was significant, indicating that overall levels of avoidant coping differed by patterns of spiritual connectedness. Planned contrasts indicated that youth in the low and steady and decliner profiles had lower levels of avoidant coping than youth in the high and steady profile. There again was a multivariate effect of time and a significant multivariate profile X time interaction. These results indicate that avoidant coping changed over time, and that the pattern of these changes differed across profile membership. As seen in Figure 2, Panel b, youth in all profiles evidenced declines in avoidant coping from Time 1 to Time 2, but youth in the high and steady profile showed the least amount of decline and evidenced an increase in avoidant coping at Time 4.

Goal-directedness was examined next. Once again, the between-subjects’ effect was significant, indicating that overall levels of goal directedness differed by patterns of spiritual connectedness. Planned contrasts indicated that youth in the low and steady and decliner profiles had lower levels of goal directedness than youth in the high and steady profile. There was no multivariate effect of time but the multivariate profile X time interaction was significant. These results indicate that overall goal directedness did not change over time, but that patterns of fluctuation differed across profile membership. As seen in Figure 2, Panel c, goal-directedness was fairly stable in the first three timepoints of the study for the low and steady and decliner profiles, while goal directedness rose in the high and steady profile. At the final study timepoint, there was a dip in goal directedness among the high and steady profile youth, and an increase in goal directedness among the low and steady profile youth.

Caregiver reports of emotion management was our next outcome, which was quantified by reports of emotion regulation and emotional lability. For the ANCOVA with emotion regulation, the between-subjects’ effect was significant, indicating that overall levels of emotion regulation differed by patterns of spiritual connectedness. Planned contrasts indicated that youth in the low and steady and decliner profiles had significantly lower regulation scores than youth in the high and steady profile. There was a multivariate effect of time but the multivariate profile X time interaction was not significant. These results indicate that overall emotion regulation changed over time, but that patterns of fluctuation did not differ across profile membership. The results for emotional lability were similar to those for emotion regulation. The between-subjects’ effect again was significant, indicating that overall levels of emotional lability differed by patterns of spiritual connectedness. Planned contrasts indicated that youth both in the low and steady profile and decliner profile had higher emotional lability scores than youth in the high and steady profile. There was a multivariate effect of time but the multivariate profile X time interaction was only marginally significant. These results indicate that overall emotional lability changed over time, and that patterns of fluctuation differed marginally across profile membership.

Finally, we evaluated associations of spiritual connectedness profiles with life satisfaction. As with the prior analyses, there was a significant between subjects’ effect for profile membership, indicating overall differences in life satisfaction by profile. Consistent with many of the prior analyses, planned contrasts indicated that youth both in the low and steady profile and decliner profile had lower life satisfaction scores than youth in the high and steady profile. In contrast to many of the prior results, there was neither a multivariate effect of time, nor a multivariate profile X time interaction. This indicated that life satisfaction remained stable over the study period and did not vary by profile membership.

In terms of sensitivity analyses, we compared analyses with non-imputed data to analyses with imputed data. In terms of overall conclusions, there were few differences. Using non-imputed data, there were main between subjects’ effects of connectedness profile for all outcomes with the exception of avoidant coping, which was marginally significant. Planned comparisons using non-imputed data revealed significant differences between the decliner profile and the high and steady profile on all outcomes except life satisfaction which was marginally different and avoidant coping which was not different. Youth in the low and steady profile differed from youth in the high and steady profile on all outcomes except emotion regulation and emotional lability, which were marginally different from one another. In terms of multivariate time X profile interactions, the results were similar for imputed and non-imputed data for emotion management, goal-directedness, and life satisfaction. Using non-imputed data, the time X profile interactions were not significant for the positive reframing or avoidant coping.

In summary, we used Latent Class Growth Analysis to identify patterns of change in spiritual connectedness across the period of early and middle adolescence. Three distinct patterns emerged in each developmental cohort: a group of youth who had low levels of connectedness and who remained low, a group of youth whose level of connectedness declined over the study period, and a group who had high levels of spiritual connectedness and remained high. The percentage of youth in each of these profiles varied in the early and middle adolescent cohorts. We then conducted analyses to identify associations of these profiles with coping and adjustment, controlling for grade level, adolescent gender, household income, and maternal caregiver education. Our analyses revealed significant associations between patterns of spiritual connectedness over time and positive reframing and avoidant coping, emotion regulation and emotional lability, goal directedness, and life satisfaction. In each case youth evidencing a “high and steady” spiritual connectedness profile showed more adaptive levels of these constructs relative to youth in the “decliner” and “low and steady” profiles. Positive reframing coping, avoidant coping, and goal-directedness interacted with profile membership but in different ways: Youth in the decliner profile showed steeper declines in positive reframing coping relative to youth in other profiles, while for avoidant coping and goal directedness, youth in the high and steady profile differed from youth in other profiles, showing less steep declines in avoidant coping and increases in goal-directedness over time relative to youth in other profiles.

Discussion

Religiosity and spirituality play a significant role in the lives of adolescents, however levels of religiosity and spirituality have been known to decline with age (Denton et al. 2008; Lee and Neblett 2017; Michaelson et al. 2016). Although there was some evidence from prior research that this decline was heterogeneous, little was known of the various patterns of change in spiritual connectedness during adolescence. Based on these gaps the present study examined whether distinct profiles emerge when considering change in adolescent spiritual connectedness over time, whether these profiles differed by developmental stage, and if these profiles were differentially associated with coping, goal-directedness, and well-being. Similar to past literature, our study found levels of spiritual connectedness declined as adolescents aged (Denton et al. 2008; Lee and Neblett, 2017; Michaelson et al. 2016). As hypothesized, distinct patterns of change in levels of spiritual connectedness over time emerged, with a three-profile solution best fitting the data for both early and middle adolescents. Adolescents with a “low and steady” profile of spiritual connectedness started low and remained low throughout the 3-year period of the study; one in six early adolescents and nearly one in three middle adolescents fell into this profile. Adolescents who were “decliners” started moderately high but declined significantly over the study period, with early adolescents experiencing steeper declines than middle adolescents. Over a quarter of the early adolescents and nearly half of the middle adolescents fell into this profile. A “high and steady” pattern characterized the third profile, with adolescents starting high and remaining so over the study period, although early adolescents experienced a slight but significant decline and middle adolescents experienced a slight and marginally significant increase during this time frame. Over half of the early adolescents and just under a quarter of the middle adolescents fell into this profile.

These patterns of change in spiritual connectedness are consistent with Denton et al. (2008) finding that decline in religiosity is not universal. Denton et al. (2008) found that the pattern of change was dependent on which aspect of religiosity was measured, such that when adolescents were assessed on most standard measures of private and public religious practices (beliefs in God, attendance of religious services, praying and reading of scriptures alone etc.), there was a decline over the three-year period. However, when adolescents were asked to self-report on whether they had become more religious, less religious, or stayed the same over the study period, a majority reported they remained the same and for those who reported a change, a higher proportion reported becoming more religious than less religious. Although African Americans are socialized by their parents to engage in religious activities (Mattis and Mattis 2011), adolescence also is a period of spiritual exploration where individuals take their own initiative in evaluating their beliefs and the significance of religiosity and spirituality in their lives (Good and Willoughby 2008). In the current study, among adolescents in the low and steady and high and steady profiles, spiritual connectedness might have been very insignificant or highly significant and continued to remain so during the study period such that even with further exploration of their beliefs, its significance remained the same. However, for those in the decliner category, as noted by other researchers (Mattis and Mattis 2011) adolescents might have identified other effective and non-religious means of managing their stressors, might begin to question the place of science and spirituality as well as question the moral expectations tied to a system of faith. Hence, spiritual connected was not that influential with time.

On the other hand, our findings contradict Lee and Neblett’s (2017) findings that among adolescents who experienced a decline in both intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity, the rate of decline was similar for those in the high and low categories. Despite the contradictions, the varying profiles provide a more detailed and descriptive evaluation of what happens to spiritual connectedness across adolescence for low-income, predominantly African American youth. Our findings highlight the importance of investigating further, as variations in the decline in spiritual connectedness had significant impacts on other important aspects of an adolescent’s life, including coping strategies, emotion management, and overall life satisfaction.

High and steady spiritual connectedness was associated with greater use of reframing and avoidant coping for both early and middle adolescents, confirming our hypotheses. Given that religiosity and spirituality are protective for adolescents (Jennings et al. 2014), this finding is entirely consistent with Chen and Miller’s (2012) “shift and persist” theory regarding why some low-income individuals do not fare poorly even in the face of adversity. As noted by Chen and Miller (2012), a minority of individuals low in socioeconomic status likely exhibit shift and persist strategies, which involve accepting stressors and adjusting to them through coping strategies such as reappraisal, in concert with enduring hardships by finding meaning and maintaining a positive outlook. Those that do have a reduced physiological response to stressors, thus lowering their risk of chronic disease. Interestingly, from a developmental perspective Chen and Miller emphasized the role of positive role models whom youth learn to depend upon and trust, from whom youth learn to regulate their emotions, and who facilitate hopefulness by helping youth to find meaning in life. Our findings linking adolescents in the high and steady profile with greater coping efforts also is consistent with work by Fernando and Ferrari (2011) and Moreira-Almeida et al. (2006) who found that spirituality fostered acceptance of both positive and negative experiences, and aided in reframing experiences to foster coping. As suggested by Smith’s (2003) theory, youth who have high and steady levels of spiritual connectedness over the course of adolescence may be exposed more regularly to adults who model adaptive coping by virtue of their involvement with places of worship. The ability to accept negative experiences, fostered by spiritual connectedness, may relate to a tendency to engage in avoidant coping in that adolescents who do not wish to think about their problems can attribute their circumstances to their faith, accept them, and move forward thinking about other things. Similarly, the aspect of avoidant coping linked to wishing your circumstances were better may be fueling an adolescent choice to maintain a connection to his or her spirituality, in hopes that faithful religious practice will lead to an improved life situation.

Consistent with research on the benefits of spirituality and spiritual connectedness, youth who kept the faith, that is, who were in the “high and steady” profile, were rated by maternal caregivers across both early and middle adolescence as having better emotion regulation and lower emotional lability compared to youth who lost spiritual connectedness or maintained low spiritual connectedness over their adolescent development (Vishkin et al. 2014; 2016). These findings reflected cross-reporter effects, as spiritual connectedness was reported by adolescents, while emotion management was reported by caregivers. The association between spiritual connectedness and emotion management is particularly important, as emotion dysregulation has been linked to alcohol, tobacco, and other drag use in middle- and high-school students (Weinberg and Klonsky 2009; Weinstein et al. 2008; Wills et al. 2011).

Our hypothesis that youth with higher spiritual connectedness would have higher levels of goal-directedness also was supported by our results. This finding relates to Smith’s (2003) theory on the mechanisms through which spirituality exerts a positive and constructive influence in the lives of adolescents in that the network of role models provided, and leadership skills developed through spiritual connectedness likely models the benefits of remaining focused on one’s goals. Additionally, youth who are highly goal-oriented may view their spirituality as a means to achieving other goals and therefore may prioritize maintaining their spiritual connectedness (Emmons et al. 1998). Finally, youth with high and steady spiritual connectedness reported higher life satisfaction than youth in the decliner or low and steady groups. This finding was consistent with research by Kelley and Miller (2007) who found positive associations between dimensions of religiosity/spirituality and satisfaction with life in a sample of diverse adolescents.

This study has several strengths. First, our person-centered approach allowed us to identify patterns of spiritual connectedness during adolescence. Second, our longitudinal, two-cohort design allowed us to evaluate changes in spiritual connectedness in youth during the critical developmental period of adolescence, comparing the early adolescent transition into middle school with the middle adolescent transition into and through high school. Third, our multiple-reporter assessment of coping, goal-directedness, emotion regulation, and life satisfaction allowed us to identify ways in which changes in spiritual connectedness varied with those constructs. Finally, our use of a predominantly African American sample of adolescents contributes significant new evidence relating to a population less frequently studied in relation to spiritual connectedness. Our findings confirmed and built upon past literature on spirituality among minority adolescents by highlighting different trends in spiritual connectedness over significant developmental periods as well as confirming the heterogeneous nature of spirituality not only among African American adults, but adolescents as well.

Despite the strengths, the present study includes limitations that warrant recognition. Nearly one third of the sample dropped out of participation between time 1 and time 4 of the study. Slight differences in attrition based on age and gender existed, with males and older children more likely to stop participating before the end of the study. Given that the study intentionally recruited a high-risk, urban sample of families, it is not surprising that attrition was high. Despite the best efforts of the study staff to reduce barriers to participation and burden on participants, the sampled families faced extensive barriers that may have precluded them from participating at all four time points. Barriers included frequent changes in address and contact information, making it difficult for study staff to locate and follow up with families, as well as parents’ need to work multiple jobs or jobs with inflexible schedules making it challenging to coordinate schedules for interviews. As adolescents aged throughout the study they may have felt pressures to take on work after school to help support their family, which would again reduce availability for scheduling interviews. More generally speaking, this population experiences multiple stressors and threats to family health and wellbeing which frankly may have reduced the degree to which families made continued participation a priority. This attrition rate reduces generalizability of our findings to a broad population of low-income African American adolescents, given that there may be important contextual or individual factors differentiating those who participated fully from those who were not able or willing to complete all time points.

Additionally, given that we studied a group of primarily African American, low-income adolescents, our results may not be generalizable to youth from other racial, cultural, or demographic backgrounds. It will be important for future studies to investigate the applicability of our findings to other cultural and contextual populations. It is unclear from our single study whether these findings generalize to adolescents from other backgrounds or environments. We presume that different cultural contexts will demonstrate varying levels of spiritual connectedness in general; therefore, different baseline levels of spirituality could be seen across contexts, however it would be interesting to determine whether the same patterns of longitudinal change exist, perhaps with varying frequencies, despite initial levels of connectedness. Knowing whether these trends are consistent or varied across differing populations will allow us to identify groups who may be at particular risk of decreasing levels of protective factors during certain periods of their life.

The current study did not collect data on specific religious denominations; rather, we examined spiritual connectedness more broadly, outside of the framework of a specific religion. It is possible that trends in changes in spiritual connectedness vary based on religious affiliation. In addition to examining other racial, cultural, and demographic contexts, future studies may find value in determining if patterns of spiritual connectedness are consistent across multiple denominational or religious affiliations. The value in this would not be as an intervention strategy, but rather to identify groups particularly likely to experience declines in spiritual connectedness, and who therefore might need protective factors bolstered.

While our longitudinal design highlighted important patterns of change in spiritual connectedness over time, we were unable to investigate changes in spirituality before or after the critical developmental period of adolescence. It would be informative for future studies to see whether those with high spiritual connectedness in adolescence hold this pattern from childhood through adulthood, or if they too show declining rates over a longer period of time. It would also be important to explore whether the loss of connectedness during adolescence is permanent or merely stage-related. This understanding of long-term spiritual connectedness would inform intervention efforts designed to increase protective factors and subsequent positive adjustment and life satisfaction. Finally, while we considered gender differences in descriptive analyses and examined how gender was distributed across profiles, we did not evaluate gender as a moderator. Additionally, we did not appraise change in caregiver religious attendance or spiritual connectedness over time. Future studies may want to consider family-level changes in religious attendance as children age as a predictor of changes in adolescent spiritual connectedness over time.

Conclusion

Adolescence is a sensitive stage for spiritual development. During this period, individuals tend to engage in spiritual explorations and make commitments that have enduring implications throughout the lifespan (Good and Willoughby 2008). A large body of research has documented the protective effects of religiosity and spirituality for adolescent well-being (Cotton et al. 2006; Jennings et al. 2014). Despite this positive role of religiosity and spirituality, adolescents’ religious beliefs and participation in religious activities decline over time (Desmond et al. 2010). This decline is not universal, which has implications for adolescents’ well-being. However, relatively little research has documented patterns of spirituality during adolescence and how these patterns are linked to adjustment. The present study addressed this gap in a sample of low-income, urban, predominantly African American adolescents followed over a three-year period. The results demonstrated that indeed, there are different patterns of spiritual connectedness and not all adolescents experience a decline in spirituality over time. Specifically, a sizable percentage - just over 4 in 10 youth - maintained high and steady levels of spiritual connectedness over the periods of early or middle adolescence, although more of these youth were represented in the early adolescent cohort. Roughly, the same percentage of youth showed declines in spiritual connectedness across the adolescent years, with more middle than early adolescents represented in this profile. Just over 2 in 10 youth reported low levels of spiritual connectedness and remained low throughout the study period. Our results also confirm the clear protective effects conferred by spiritual connectedness, or intrinsic religiosity. Youth in our study with high and steady levels of spiritual connectedness were more goal-directed, reported higher life satisfaction, evidenced more effective coping strategies, and had caregivers who indicated that these youth managed their emotions more effectively than youth in the decliner or low and steady profiles. Interventions seeking to improve adolescent adjustment would do well to consider spiritual connectedness as a potential intervention target. Finding ways to increase, or reduce the decline of, spiritual connectedness in adolescence may protect against the damaging effects of poor emotion regulation and increase positive youth adjustment and well-being.

Acknowledgement

We thank the families who participated in this study and the research staff who supported this work.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants K01 DA015442–01A1 and R21 DA 020086–02 awarded to Wendy Kliewer.

Biography

Anna W. Wright is a graduate student in the Clinical Psychology doctoral program at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her research interests are on predictors of risk and resilience among youth who grow up under adverse circumstances. Specifically, she is interested in the positive adjustment of youth in institutional care settings. Ms. Wright earned her Master of Science in Clinical Psychology from Virginia Commonwealth University.

Dr. Joana Salifu Yendork is a Lecturer of Psychology at the Department of Psychology, University of Ghana. Her research interests focus broadly on the wellbeing of vulnerable children and adolescents as well as the influence of religion on mental health. Dr. Yendork obtained her PhD in Psychology from Stellenbosch University in South Africa.

Dr. Wendy Kliewer is Professor of the Department of Psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University. Dr. Kliewer’s research centers on the broad theme of risk and resilience, with specific attention to cumulative stressors, their impacts on a broad array of functioning, and protective factors that mitigate risk. She has long-standing interests in interdisciplinary, cross-cultural research, and is committed to training the next generation of scholars to continue to do research that matters. Dr. Kliewer earned her Ph.D. in Social Ecology from the University of California, Irvine, and completed postdoctoral training in prevention science at Arizona State University.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

A.W.W. drafted portions of the manuscript and participated in interpretation of the data. J.S.Y. drafted and edited portions of the manuscript. W.K. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted portions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Sharing Declaration

This manuscript’s data will not be deposited.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors report any conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of Virginia Commonwealth University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU).

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was provided by the maternal caregiver and assent was provided by the adolescent prior to initiating the data collection.

Contributor Information

Anna W. Wright, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University

Joana Salifu Yendork, Department of Psychology, University of Ghana, Ghana.

Wendy Kliewer, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University.

References

- Adkins DE, Wang V, & Elder GH (2009). Structure and stress: Trajectories of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood. Social Forces, 88, 31–60. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avent JR, & Cashwell CS (2015). The black church: Theology and implications for counselling African Americans. The Professional Counselor, 5, 81–90. doi: 10.15241/jra.5.1.81 [Google Scholar]

- Ayers T, & Sandler S (1996). Manual for the children ‘s coping strategies checklist. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University Program for Prevention Research. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley A (1999). Mighty like a river: The black church and social reform. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brougham RR, Zail CM, Mendoza CM, & Miller JR (2009). Stress, sex differences, and coping strategies among college students. Current Psychology. 28 85–97. doi: 10.1007/sl2144-009-9047-0 [Google Scholar]