SUMMARY

In this study, we characterized a serine protease from Tannerella forsythia (T. forsythia) that degrades gelatin, type I and III collagen. T. forsythia is associated with periodontitis progression and severity. The primary goal of this research was to understand the mechanisms by which T. forsythia contributes to periodontitis progression. One of our previous metatranscriptomic analysis revealed that during periodontitis progression T. forsythia highly expressed the bfor_1659 ORF. The N-terminal end is homologous to dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase IV (DPP IV). DPP IV is a serine protease that cleaves X-Pro or X-Ala dipeptide from the N-terminal end of proteins. Collagen type I is rich in X-Pro and X-Ala sequences, and it is the primary constituent of the periodontium. This work assessed the collagenolytic and gelatinolytic properties of BFOR_1659. To that end, the complete BFOR_1659 and its domains were purified as His-tagged recombinant proteins, and their collagenolytic activity was tested on collagen-like substrates, collagen type I and III combined and on the extracellular matrix (ECM) formed on human gingival fibroblasts culture HGF-1. BFOR_1659 was only found in T. forsythia supernatants, highlighting its potential role on the pathogenicity of T. forsythia. We also found that BFOR_1659 efficiently degrades all tested substrates but the individual domains were inactive.

Given that BFOR_1659 is highly expressed in the periodontal pocket its clinical relevance is suggested to periodontitis progression.

Keywords: Periodontitis, progression, collagen, periodontium destruction

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is a bacterially induced chronic inflammatory disease, affecting the soft and hard tissues surrounding and supporting teeth. The most recent data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES, (NHANES_National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Homepage, n.d) 2009–2014] indicates that the prevalence of chronic periodontitis among adult Americans is over 47%, representing 64.7 million adults1. In fact, chronic periodontitis is one of the 50 most prevalent disabling health conditions2. Additionally, recent studies have suggested that periodontal disease may increase the risk for diverse systemic conditions including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, respiratory diseases, and pre-term birth3. Tannerella forsythia (T. forsythia) is an assacharolytic Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium, isolated from the gingival sulci and periodontal pockets of patients with periodontitis4. T. forsythia is strongly associated with the pathogenesis and progression of periodontitis. This organism forms part of the red complex, long with Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola5,6. Recent sequencing studies on the oral microbiota have demonstrated expression of new putative virulence factors from commensal oral microorganisms associated with disease progression thus expanding the list of putative oral pathogens7,8.

The association of an increased risk for periodontal disease prevalence and progression with the presence of T. forsythia above certain thresholds has been demonstrated9,10.

In spite of the overwhelming evidence implicating T. forsythia in the pathogenesis of periodontitis, this bacterium remains understudied, in part due to the challenges of working with T. forsythia in the laboratory, which includes its slow growth. Nonetheless, several potential virulence factors have been identified in T. forsythia; they include a cell surface-associated protein (BspA) necessary for attachment and invasion of epithelial cells11; a cysteine protease (PtrH) with a hemolytic activity that correlates with periodontal attachment loss12; a trypsin-like protease13; sialidases SiaHI14 and NanH15; a matrix metalloprotease (karilysin) involved in the inhibition of all pathways of the complement system and in the degradation of peptides LL-3716; and a subtilisin-like serine protease (mirolase) involved in the hydrolysis of human fibrinogen17. Recently, KLIKK proteases have been described as potential virulence factor18. Lately, the outer membrane of T. forsythia has been analyzed resulting in the identification of 221 proteins suggesting the existence of additional T. forsythia virulence factors not yet identified19.

In our previous studies, we used metatranscriptomic analysis to compare community-wide in vivo gene expression of the human oral microbiome to capture a snapshot of gene expression on healthy vs. diseased sites8 and on sites with progressing periodontitis vs. its baseline (the initial sample)20. The present study is based on the in vivo gene expression profiles of T. forsythia during periodontitis progression20 within the periodontal pocket, which highlights its potential clinical relevance. The analysis showed a dramatic up-regulation of bfor_1659 ORF in progressing sites (compared with their baseline). BFO_1659 has homology to dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV (DPP IV). DPP IV is a serine protease that cleaves X-Pro or X-Ala dipeptide at the penultimate position from N-terminal ends of polypeptide chains, and most importantly, it is associated with collagen destruction. Collagen is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix (ECM) in connective tissues in mammals21 and is composed of a triple helix with a majority pattern of Gly-Pro-X or Gly-X-Hyp. The periodontium is mainly composed of collagen type I, which accounts for 80%−85% in the gingiva to 90% in the alveolar bone. Type III is the second most predominant collagen in the periodontal tissue accounting for about 15% of the total. In alveolar bone and cementum, type III is restricted to Sharpey fibers, type IV is present in basement membranes, type V on fibers and blood vessels and type VI collagen is present on microfibrils22.

In periodontitis, the destruction of the periodontium is a coordinated process of collagenolytic enzymes and collagen-like substrates from the host and the oral microbiota. As stated previously, BFOR_1659 was highly expressed during periodontitis progression in the periodontal pocket where T. forsythia is interacting with the host and the oral microbial community, which highlights its potential clinical relevance. To gain knowledge of the contribution of T. forsythia to periodontal tissue destruction, we have characterized the collagenolytic properties of BFO_1659.

METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

T. forsythia 92A2 was grown anaerobically using a GasPak system (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Company Inc) at 37°C for 3–7 days on Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA) supplemented with 5 g L−1 yeast extract (Oxoid), 1 g L−1 L-cysteine, 10 mg L−1 N-acetylmuramic acid, 5 mg L−1 hemin, 0.5 mg L−1 menadione (all reagents from Sigma Aldrich) and 50 ml L−1 defibrinated sheep blood (Northeastern Lab). Liquid cultures were done in Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB) supplemented as noted above without sheep blood. Escherichia coli BL21DE3 was grown on Luria-Bertani agar (LB) (Sigma Aldrich) overnight aerobically at 37°C. After pET-22b+ plasmid cloning, E.coli BL21DE3 (Novagen) was grown on LB agar was supplemented with 50 mg ml−1 of ampicillin (Sigma Aldrich).

Supernatant and cell lysate.

T. forsythia 92A2 was grown in TSB supplemented with 10 mg L−1 of N-acetylmuramic acid and 5 mg L−1 of hemin. The number of viable cells in each liquid culture was calculated by standard plate count and correlated to the optical density OD600 1.0 corresponding to 9 × 107 cells ml−1. A total of 100 ml of T. forsythia 92A2 liquid culture was used to guarantee 40 μg of total protein from supernatants and cell lysates. The supernatants were centrifuged and concentrated using Centriplus YM-30 columns (Millipore) and kept at −20°C. The cell lysates were prepared from the pellets of liquid cultures as follow: after centrifugation (10,000 × g, 30 min), the pellets were washed twice with 10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, resuspended in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, and disintegrated by sonication in ice bath at 1500 Hz for 5 cycles followed by a second wash and resuspended in 50 μl of Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS).

Production of recombinant proteins.

In total, three proteins were expressed and purified as His6-tagged recombinant proteins as follow: rDPPIV corresponding to the entire BFOR_1659 protein, rDppIV-N (DPP IV domain at the N-terminal end) and rPepS_9 (peptidase domain at the C-terminal end). The fragments were PCR-amplified using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, and the primers were engineered with NdeI and XhoI hanging at the 5’ end of forward and reverse primer (Table 1). Each product was cloned into the pGEMT-Easy cloning vector (Promega) and confirmed by sequencing. In all cases, after digestion with NdeI and XhoI, each insert was cloned into the NdeI-XhoI site of vector pET-22b+ (Novagen) for expression as a His6-tagged fusion protein in E.coli BL21DE3 (Novagen). For recombinant protein production, 1 L of pET-22b+ insert-containing E. coli BL21DE3 of each construction was grown 3 hours (OD550 nm 0.6) at 37°C and then induced with 1 mM IPTG overnight at 30°C. The cells were harvested and the pellet resuspended in lysis buffer (NaH2Po4, 50 mM; Na2HPo4, 50 mM; NaCl 300 mM and lysozyme 50mg ml−1; pH 7.5) then sonicated and centrifuged (10,000 rpm at 4°C) to remove unbroken cells and debris. The recombinant proteins were purified by affinity chromatography on Ni2+ nitriloacetic agarose (NTA, Qiagen), and concentrated with 3KDa Amicon Ultra columns (Millipore). Protein concentrations were determined by Bio-Rad protein assay using bovine serum albumin (New England BioLab) as standard. All recombinant proteins were examined by Western blot using anti-His-tag as a primary antibody.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study. NdeI and XhoI adapter sequences are underlined.

| Production of recombinant proteins | Sequence 5’-3’ forward/reverse |

|---|---|

| His6-BFOR_1659 complete protein (rDPPIV) |

CATATGGGGGAAGGAAACAGGAATAGCT / CTCGACATTTTCCAGTACAAAATTCGTCA |

| His6-BFOR_1659 N-terminus (rDppIV_N) |

CATATGGTTTCAATACAGCGGCCCCAATT / CTCGAGATTTTCCAGTAGAAAATTCG |

| His6-BFOR_1659 C-terminus (rPep_S9) |

CATATGGGGGAAGGAAACAGGAATAGCT / CTCGATCGAGACATAATAGGCGAAGTTGG |

Western-blots.

For all Western blots, the same amount of protein was mixed with equal volume of Laemmli sample buffer, denatured by boiling, and loaded onto precast 4–20% polyacrylamide gels (GenScript). After SDS-PAGE, fractionated proteins were electro-transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad), incubated with primary antibody and then horseradish peroxide-linked goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Amersham). Signals were detected with the ECL Western-blot detection kit (Amersham). As primary antibodies, we used anti-His-tag and anti-human DPP IV antibodies (Antibodies online Inc).

Collagen degradation activity.

Collagenase activity was measured on a range of substrates. For all of them, three independent biological replicates were done.

Collagen-like substrates.

1- DPP IV-Glo™ Protease Assay (Promega) is a luminescent test that measures specific DPP IV activity. The assay uses a proluminiscent DPP IV substrate (Gly-Pro-aminoluciferin) that produces a luminescent signal, proportional to the DPP IV activity in the sample. 10 mM of DPP IV-Glo™ substrate was used in all tests. Relative luminescence was determined by subtracting the background fluorescence from light recorded from enzyme containing wells. DPP IV-Glo™ Protease Assay was run in triplicate using 20 μg of each protein following the instructions of the manufacturer (n=3). Luminescence was monitored for 4.5 h. 2-EnzChek Gelatinase/Collagenase Assay Kit (Molecular Probes) uses a substrate of pure gelatin from pig skin heavily labeled with fluorescein (DQ™-gelatin). If the substrate is efficiently digested, fluorescence is measured. Samples were incubated 5 h in the dark at 30°C with 100 μg ml−1 of DQ-gelatin following the instructions of the manufacturer. Relative fluorescence was determined by subtracting the background. The assay was run in triplicate using 20 μg of each protein. 3-Spectrophotometric monitoring of hydrolysis of synthetic peptide (N-(3-[2-Furyl]acryloyl)-Leu-Gly-Pro-Ala)(FALGPA) (BioVision, Milpitas, CA). FALGPA mimics collagen structure and is stable at temperatures above 37°C. The hydrolysis was measured up to 120 min, at 345 nm at 37°C following the manufacturer’s instructions. The test was run in triplicate using 20 μg of each protein. Fluorescence, luminescence and optical density were measured on a Synergy HT microplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc).

Collagen type I and type III.

We assessed the degradation of collagen type I and type III present in combination in Bio-Gide® membranes (Geistlich Biomaterials). Bio-Gide®, membranes are composed of pure collagen type I and III and are used in oral surgery for tissue regeneration to protect the initial coagulum. The collagens in the membranes were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (Sigma Aldrich) as follows: Bio-Gide® membranes were immersed in 0.01M NaoH (pH 9.0) solution for 10 min. The membranes were washed with water and acetone and then incubated overnight with 0.2 mg ml−1 fluorescein isothiocyanate in acetone in the dark at 4°C. After labeling, the membranes were exhaustively washed with acetone, water and Tris-Buffered Saline buffer (TBS) until the fluorescence in the washings reached basal levels. The membranes were cut into 5 mm × 5 mm pieces and incubated for 16 hours at 37°C in 1 ml of incubation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) with 20 μg of each protein sample (rDPPIV, rDppIV-N, rPepS_9). After incubation, the hydrolysis was measured as fluorescence in supernatants (excitation/emission 490/520nm). The measurements were made on a PTI spectrophotometer (Synergy HT BioTek) at 25°C. The reference value corresponding to 100% lysis was obtained by incubating the membrane piece with 10 U ml−1 of collagenase from Clostridium hystolyticum (Sigma Aldrich). Three independents assays were done.

A semi-quantitative measure of residual native collagen in the extracellular matrix of Human Gingival Fibroblasts culture HGF-1.

The human gingival fibroblasts cell line HGF-1 (ATCCR CRL-2014) was a kind gift from Dr. Ricardo Battaglino at The Forsyth Institute. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 4.5 g L−1 high glucose content (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, (FBS) (Hyclone) 2 mM L−1 glutamine, 1.5 g L−1 sodium bicarbonate, 100 units ml−1 penicillin G and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin (all reagents from Life Technologies). DMEM was changed twice a week. Cells were subcultured weekly using 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% ethylenediaminetetraacetic (EDTA) (Gibco). All cells were maintained in Petri dishes with 12 ml of growth medium and kept at 37°C in a humidified 95% air, 5% Co2 atmosphere.

HGF-1 cells were seeded on pretreated Poly-L-lysine (NeuVitro Co) round glass cover slips for 4 days until they reached 90% confluence. Cells were incubated with 30 μg of rDPPIV, rDppIV-N, and rPepS_9 on independent round glass cover slips in triplicate. In parallel 10 U ml−1 of C. hystolyticum, collagenase was used as positive control. After incubation, cover slips were transferred to 24 well cell culture plate (NUNC) for collagen semi-quantification and imagining using Sirius Red/Fast Green collagen staining (Chondrex, Inc). This test is a dye combination used to distinguish collagen from its surrounding materials. Sirius Red specifically binds the [Gly-X-Y]n helical structure of fibrillar collagen, regardless of collagen type, whereas Fast Green binds to non-collagenous proteins in cultured cell layers. These dyes were extracted from cell cultures, and the micrograms of collagen and non-collagenous proteins were calculated based on oD 540 (Sirius red) and oD 605 (fast green). This test offered the advantage of imaging the cells before collagen semi-quantification. Briefly, the HGF-1 cells on coverslips were washed with PBS and fixed with Kahle fixative reagent (28 ml of ethanol, 10 ml of 37% formaldehyde, 2 ml of glacial acetic acid and 60 ml of distilled water) for 10 min at room temperature, and washed with PBS. The cells were covered with Red and Green Dye solution for 30 min and extensively rinsed with distilled water. The cells were observed under an Axiovert 25 (Zeiss) microscope. After imagining the cultures were gently covered with Dye Extraction Buffer (provided by Chondrex) and the dye solution was collected and read at oD values at 540 nm and 605 nm with a SmartSpec Plus (BioRad) spectrophotometer. For calculation the manufacturer suggests: collagen (μg/dye solution) = oD 540 value – (oD 605 × 0.291)/0.0378 and for non-collagenous proteins (μg/dye solution) = oD 605 nm/0.00241. The non-collagenous protein values were used to normalize the results of collagen because protein levels are relative to the cell density of the samples.

RESULTS

T. forsythia in vivo up-regulates bfor_1659 during periodontitis progression20. BFoR_1659 shows homology with DPP IV, a collagenolytic protein. Given that BFoR_1659 was highly expressed within the periodontal pocket, coupled with the fact that periodontium is rich in collagen type I and III, the potential clinical relevance of BFoR_1659 is high. The present manuscript reports on the characterization of BFoR_1659 as a collagen/gelatin digesting protein to get a better knowledge of the contribution of T. forsythia to periodontitis progression.

BFoR_1659 is an 82 KDa protein. Bioinformatic analysis identified two motifs in BFoR_1659. At the N-terminus end, there is a domain with high sequence similarity to DPP IV, a serine protease involved in collagen destruction while the C-terminal end harbors a domain with high similarity to peptidase_S9.

The genome sequence of T. forsythia strain 92A2 was initially annotated as T. forsythia ATCC 43037. However, they are different strains. To sequence the genome of T. forsythia ATCC 43037, a new sequencing project was initiated24. BFoR_1659 from T. forsythia 92A2 (Tannerella forsythensis: NC_016610) and T. forsythia ATCC 43037 (Tannerella forsythensis ATCC 43037: Ga0077709_1058 ) are identical. The only difference is in their intergenic region: while T. forsythia 92A2 harbors three hypothetical proteins, T. forsythia ATCC 43037 has 638 bp of intergenic region.

As mentioned above BFoR_1659 from T. forsythia 92A2 at the amino acid sequence level, showed 100% identity to T. forsythia ATCC 43037, Tannerella strains KS16 (99%), 3313 (99%), 10960 (31%), WW11663 (26%), the University of Buffalo strains UB4 (30%), UB20 (26%) and UB22 (26%). Interestingly, the taxa associated with health23, BU63 and BU045 are 100% identical to BFoR_1659. out of Tannerella genus, the highest similarity and identity (99% and 84%, respectively) was found in genomes of Parabacteriodes sp. BFoR_1659 shares 62% identity to P. gingivalis DPP IV and 44% to human DPP IV.

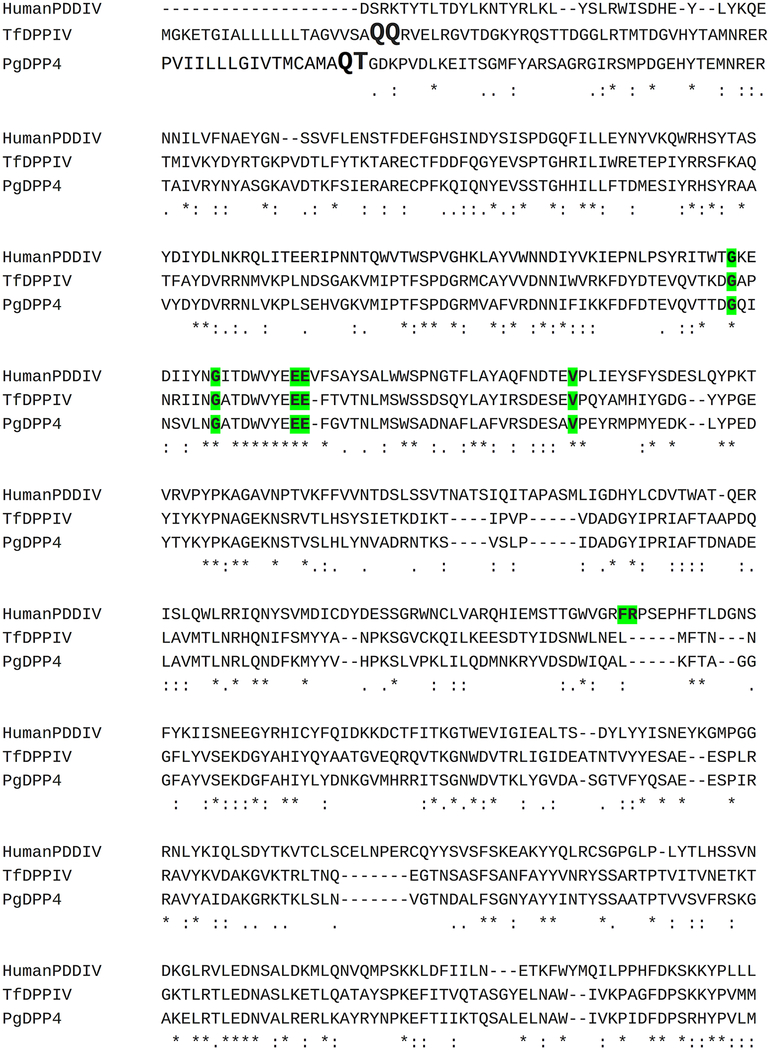

BFoR_1659 belongs to the same family of proteases (prolyl oligopeptidase family, S9, MERoPS Database). BFoR_1659 shares 62% and 44% amino acid sequence identity with P. gingivalis and human DPP IV respectively. All the critical features of the catalytic machinery are structurally conserved, including the S1-pocket accommodating the proline, the catalytic triad, the oxyanion hole required for stabilization of the transition state and tetrahedral intermediates, the two glutamates that bind the positively charged N-terminus of the substrate and the S1’ pocket that maintains a sharp bend in the substrate’s backbone. All these features have been described in detail for the human DPP IV25–27. The analysis of the S1-pocket, S2-glutamates, S2-extensive residues and S1-residues are depicted in Fig 1. The S1-pocket is located next to the catalytic site which is Ser 612 (Ser 593 on P. gingivalis DPP IV)28. Based on the structural alignment the residues flanking the S1-pocket are identical in human, P. gingivalis and T. forsythia DPP IV. The residues on the S2-extended pocket are not completely conserved in P. gingivalis DPP IV and BFoR_1659. one could think that the ligands that take advantage of these local differences of the S2-extended pocket might be more selective for a particular DPP IV form.

Fig. 1.

Structural sequence alignment of human, P. gingivalis and T. forsythia DPP IV (BFoR_1659). Signal peptide in black bold at the N-terminus, with a cleavage site between two glutamines Q-Q at positions 21 and 22 in BFoR_1659 and between threonine and glutamine (Q-T) at position 17 and 18 in P. gingivalis DPPIV. In bold red is the active site on the three proteins located at Ser-593, Asp-668, and His-700 (adopting BFoR_1659 numbering). The S1-pocket, highlighted in yellow is hydrophobic, lipophilic residues Tyr-594, Tyr-629, Trp-622, and Val-619 are almost identical between the three proteins. BFoR_1659 harbors Phe instead of Tyr-594 and Pro instead of Val. The S2-pocket is highlighted in green. P. gingivalis DPP IV and BFoR_1659 lack the phenylalanine and Arginine present in human DPPIV. In the three enzymes, the positive charge of the amino terminus of the substrate peptide is neutralized by the negative charge from the two glutamate residues flanking S2-pocket at the Glu-195 and Glu-196.

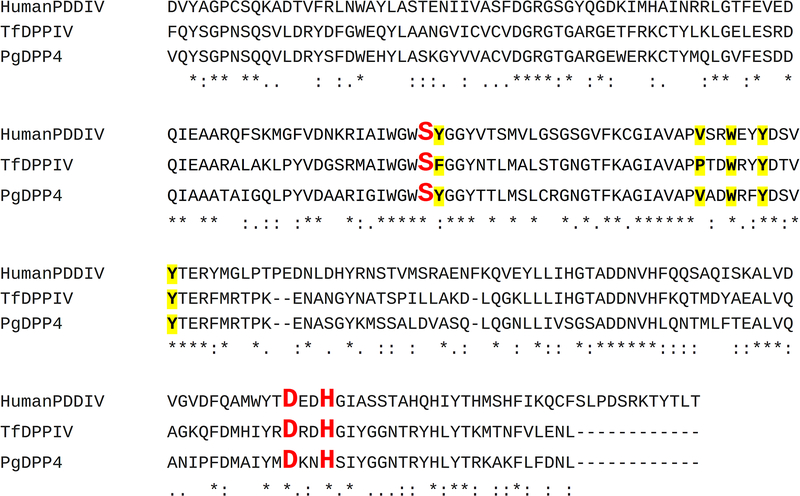

To characterize BFoR_1659 we first induced and semi-purified as His6-tagged fusion proteins: the complete BFoR_1659 (r-DPP IV), the N-terminal domain (rDppIV-N) and the C-terminal domain (rPepS_9). The proteins displayed the expected size: rDPPIV 82 KDa, rDppIV-N 38 KDa and rPepS_9 25 KDa (Fig 2).

Fig. 2.

Western blots and Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of His6-tag recombinant semi-pure proteins A) Coomassie-stained gel and Western blot of 20 μg of rDPPIV (A) Protein ladder (B) SDS-PAGE gel (C) western blot using anti-His-tag antibody. B) Coomassie-stained gel and Western blot of 20 μg of rDppIV and rPepS_9. (A) Western blot using anti-His-tag antibody of (A) rDppIV (B) rPepS_9 (C) of rDPPIV and Western blot showing 82KDa expected size B) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel and Western blot of rDppIV-N and rPepS_9 showing 38KDa and 25 kDa, respectively.

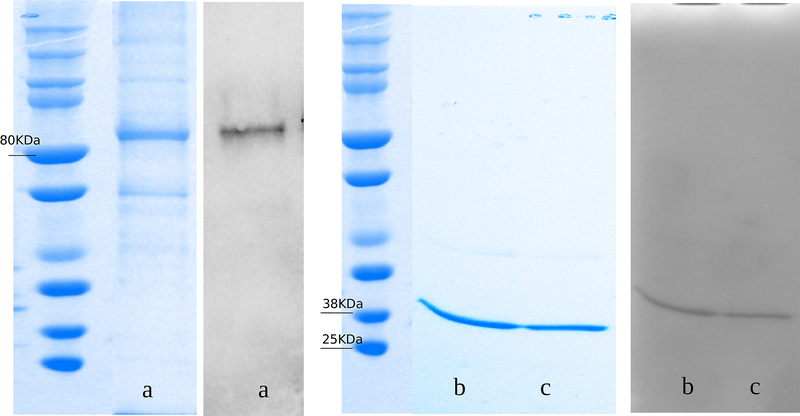

Secondly, we determined the cellular localization of BFoR_1659. Knowing where the protein is in the cell is often critical to understanding its function. The cellular localization of the native BFoR_1659 was assessed by Western blot on an equal amount of total proteins from supernatants and cell lysates of T. forsythia liquid cultures containing 1.0 E 108 cell ml−1. To this extent, anti-human DPP IV was used as primary antibody. The use of this antibody was previously validated by Western-blot. As expected, r-DPP IV and rDppIV-N cross-reacted with anti-human DPP IV antibody and no detectable signal were present on rPepS_9 (Fig 3A). We found that BFoR_1659 is secreted into the medium as the correct size signal was present only in the supernatants and no detectable signal was seen in any of the corresponding cell lysate samples (Fig 3B). Moreover, BFoR_1659 sequence analysis showed a cleavage peptide prediction between amino acid 21 and 22 (Q-Q), indicating that BFoR_1659 has features of secreted proteins (Fig 1).

Fig. 3.

Cellular localization of BFoR_1659. A) Western blot to validate the use of the anti-human DPPIV antibody. The signal was present on N-terminus of BFoR_1659 where major homology exists. No detectable signal was present on rPepS_9. B) Western blot showing the cellular localization of BFoR_1659. 40 μg of total proteins of supernatant and its cell lysate were loaded into the SDS-PAGE gel. No detectable signal was seen on cell lysate samples, supernatant sample showed the expected size of 80KDa. (n=3). The left panel shows the Coomassie-stained gel.

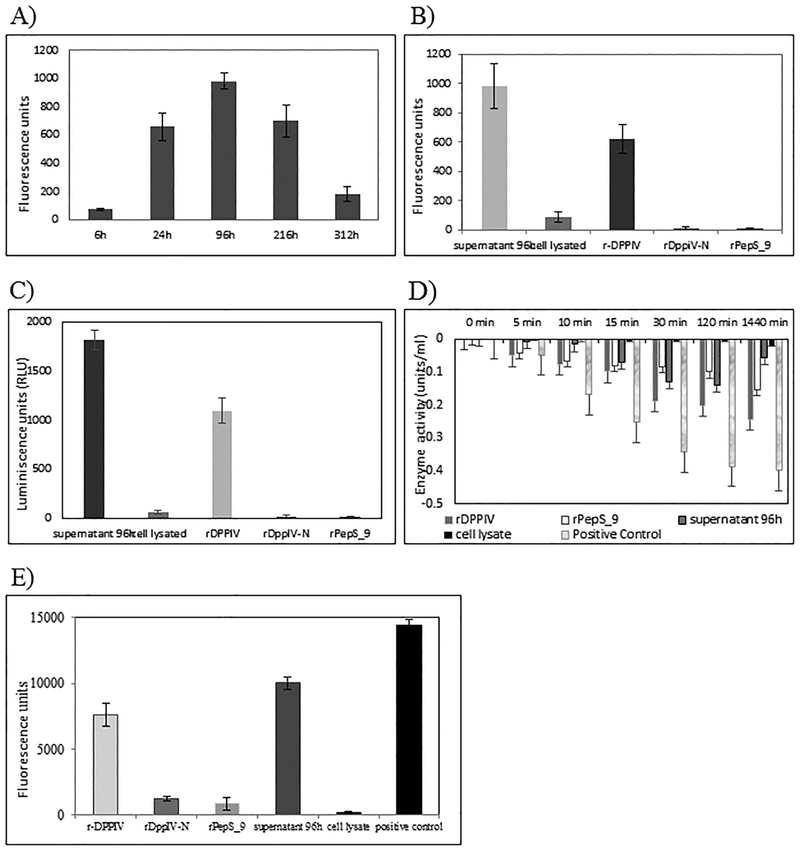

We started the characterization of BFoR_1959 by evaluating the gelatinolytic properties of the recombinant proteins. Knowing that BFoR_1659 is secreted into the medium, we checked the dynamics of expression by determining the peak of activity in time series experiments. We tested the hydrolysis of fluorescein-labeled DQ gelatin conjugate substrate after incubation with the proteins at equal concentration. This substrate is highly labeled so that the fluorescence signal is quenched until enzymatic digestion yields highly fluorescent fragments. To get a better approach we paired time point samples with growth curve and tested supernatant samples of T. forsythia growth at 6 h, 24 h, 96 h (4 days), 216 h (9 days), and 312 h (13 days). T. forsythia doubling time is 14.2 hours and stationary phase starts approximately after 4 days of growth (data not shown). Fig 4A shows that the highest level of gelatin degradation was detected after 4 days (beginning of stationary phase). Subsequent experiments were performed with supernatants from 4 day-old cells.

Fig. 4.

Collagen-like degradation assays. A) Time series experiment to determine the level for expression of BFoR_1659 in supernatants at different times of growth using EnzChek Gelatinase assay. 20 μg of total protein from each supernatant were tested (n=3) B) Gelatinolytic activity of recombinant proteins (EnzChek assay). In all cases, 20 μg of total protein from each sample were tested (n=3) supernatant 96h was taken as reference C) DPP IV-Glo Protease Assay measuring specific DPP IV activity on 20 μg of each protein tested (n=3) supernatant 96h was taken as reference D) Hydrolysis FALGPA peptide 20 μg of total protein from each sample was tested (n=3). Collagenase of C. hystolyticum was taken as a standard of hydrolysis. E) Degradation of collagen type I and III in FITC-labeled Bio-Gide bilayer collagen membranes 20 μg of each protein were tested (n=3). Collagenase of C. hystolyticum was taken as reference.

We then assessed the gelatinolytic properties of BFoR_1659. Fig 4B summarizes those results. The higher activity was present in the supernatant, and it was arbitrarily taken as the standard, followed by rDPPIV which represented 63% of the supernatant activity. The cell lysate retained a low activity of 8%, and the independent domains were unable to digest this substrate even after 5h of incubation.

The collagenolytic activity assessment was tested on different collagen substrates: 1-proteolysis of Gly-Pro-aminoluciferin. This assay is specific for DPP IV activity. As shown in Fig 4C, the higher activity was also present in supernatant samples, followed by the rDPPIV which represented 60% of supernatant activity. This percentage is very close to the one found on the gelatinolytic test (63%). In contrast, the cell lysate showed less than 1% of activity and rDppIV-N, and rPepS-9 showed no detectable activity. 2-hydrolysis of FALGPA peptide. 10 U ml−1 of C. hystolyticum collagenase was taken as 100% of activity. The complete protein (rDPPIV) showed the highest hydrolysis, which represented 40% of control while the rDppIV-N and rPepS_9 fragment only had 16% and 2% respectively. (Fig 4D). 3-Collagen types I and III combined in the same matrix. We tested the hydrolysis of Bio-Gide® membranes previously labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate. We also use 10 U ml−1 of C. hystolyticum collagenase as 100% activity. As Fig 4E shows, the hydrolysis of the supernatant corresponded to 70% rDPPIV hydrolyzed 53%, rDppIV-N 8.7%, rPepS_9 6.0%, and its cell lysate 1.1%. The degradation pattern of collagen types I and III present in Bio-Gide® membranes and collagen-like substrates are similar.

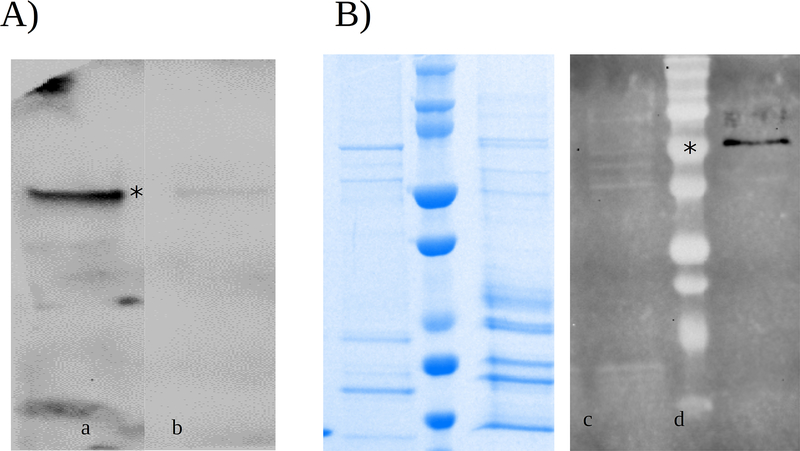

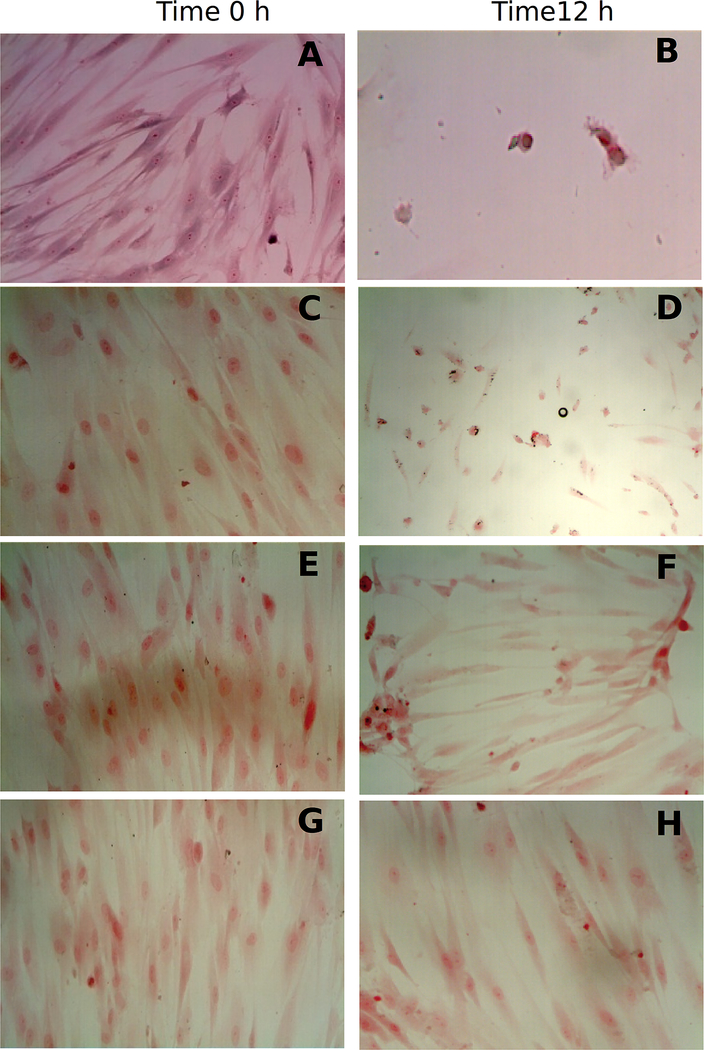

Finally, we imaged and semi-quantified the residual collagen on HGF-1 cells grown in cover slides after degradation of extracellular matrix. The amount of residual collagen was calculated after normalizing with non-collagenous proteins using Sirius Red/Fast Green collagen staining assay, after 12 h incubation, residual collagen was 30% in the presence of rDPPIV, and in the presence of the independent motifs the collagen was no degraded, as the residual collagen was very low, 98% with rDppiV-N and 96% with rPepS_9. After incubation with the positive control the residual collagen was 12%. See Fig 5.

Fig. 5.

Degradation of ECM on Human Gingival Fibroblast (HGF-1) cells grown on cover slides. 30 μg of protein from each sample were incubated for 12h with HGF-1 cells. The residual collagen was measured with Sirius Red assay on culture and after the cells were fixed and imaged. A,B positive control (10 U ml−1 of C.histolyticum collagenase) C,D rDPPIV; E,F rDppIV-N; G,Hr-PepS_9.

DISCUSSION

Periodontitis is a polymicrobial disease characterized by chronic inflammation of the gingiva that, if untreated, leads to the destruction of tooth-supporting tissues. It is apparent that the functions of distinct species within the subgingival microbiota are intimately intertwined with the rest of the oral microbial community and the host. This point highlights the relevance of examining the gene expression profile of specific species of the subgingival microbiota, in the context of the periodontal pocket. To gain more insights on the onset and development of the periodontal disease, we have previously carried out independent studies on in vivo gene expression profiles of the oral microbial community in severe periodontitis8 and periodontal disease progression20. T. forsythia is strongly associated with the pathogenesis and progression of periodontitis5. To provide a better understanding of the contribution of T. forsythia to the onset of periodontal disease, we have focused our research efforts on the in vivo gene expression patterns of T. forsythia, during periodontitis progression20. our studies revealed that T. forsythia expressed bfor_1659 at high levels during periodontitis progression and most importantly this up-regulation occurs within the periodontal pocket in which bacteria-bacteria and bacteria-host interactions shape its behavior, thus validating BFoR_1659 potential clinical relevance20. BFo_1659 has high homology to DPP IV, at its N-terminal end and belongs to the serine protease family. At the functional level, DPP IV is an ectopeptidase associated with degradation of collage, cleaving X-Pro or X-Ala dipeptide at the penultimate position from N-terminal ends of polypeptide chains.

Collagen is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix in connective tissues in mammals29. It is composed of a triple helix with a majority pattern of Gly-Pro-X or Gly-X-Hyp. So far, 29 types of collagen have been described with collagen type I being the most abundant in the human body30–32.

The periodontium is mainly composed of collagen type I, which accounts for 80%−85% in the gingiva to 90% in the alveolar bone. Type III is the second most predominant collagen in gingiva representing about 15% of the total. In alveolar bone and cementum, type III is restricted to Sharpey fibers. Type IV collagen is present in basement membranes, type V in blood vessels and type VI in microfibrils33.

The destruction of periodontal tissue is a critical feature of chronic and aggressive periodontitis and the degradation of gingival collagen initiates the formation of the periodontal pocket, which harbors the growth of anaerobic species. The tissue destruction may result in local impairment of the blood supply, and the buildup of metabolites from protein hydrolysis results in the reduction of redox level34. The proteins involved in collagen destruction processes are considered virulence factors given their crucial role in tissue degradation. DPP IV has been directly linked to periodontitis, as it is present in the saliva of chronic periodontitis patients21,35. Moreover, the positive correlation between high levels of DPP II and DPP IV in gingival crevicular fluid and periodontal attachment loss has been reported22,36. In the working model, the periodontally diseased sites are wounds that do not heal as a result of unresolved chronic inflammatory processes37 and constant bacterial protease aggression. It has been shown that P. gingivalis secretes endopeptidases (Arg-gingipains and Lys-gingipain) as well as exopeptidases (DPP IV, DPP-7, DPP11, PTP-A, and CPG-70) with the ability to degrade collagen type I38–40. DPP IV from P. gingivalis has recently been fully characterized28

As mentioned above, BFoR_1659 shares 62% and 44% amino acid sequence identity with the corresponding genes from P. gingivalis and the human DPP IV, respectively. All the critical features of the catalytic site are structurally conserved, including the S1-pocket accommodating the proline, the catalytic triad, the oxyanion hole required for stabilization of the transition state and tetrahedral intermediates, the two glutamates that bind the positively charged N-terminus of the substrate and the S1’ pocket that maintains a sharp bend in the substrate’s backbone. All these features have been described in detail for the human DPP IV27,41,42. The analysis of the S1-pocket, S2-glutamates, S2-extensive residues and S1-residues and the catalytic site, show a high similarity between human, P. gingivalis DPP IV and BFoR_165928. Based on the structural alignment the residues flanking the S1-pocket are identical in human, P. gingivalis and T. forsythia DPP IV. The residues on the S2-extended pocket are not completely conserved in P. gingivalis DPP IV and BFoR_1659. one could think that the ligands that take advantage of these local differences of the S2-extended pocket might be more selective for a particular DPP IV form. The structural conservation among these three enzymes strongly suggests that they might cleave the same substrates including collagen. Interestingly, mice injected with P. gingivalis mutant strain lacking DPP IV developed fewer abscesses and survived longer than mice injected with the wild-type strain (P. gingivalis strain W83). These data suggest that DPP IV plays a crucial role in virulence43. DPP IV has also been proposed to play a role in pathogenicity for Streptococci44–46.

It is often difficult to distinguish true collagenases from gelatinases or other bacterial proteases. For vertebrates, the difference between collagenases and gelatinases is evident, as they hydrolyze native collagen (or water-insoluble native collagen) at a single peptide bond across the three alpha chains47,48. After this initial fragmentation resulting fragments tend to uncoil into collagen polypeptides, which are more susceptible to other proteases, such as gelatinases and the majority of microbial collagen-degrading proteins. Interestingly, almost all collagen types are likely to be attacked by microbial collagenases at specific sites of the α-chains. However, these collagenolytic bacterial proteases should not be confused with the true microbial collagenases, which can degrade the triple-helical native collagen49,50. According to the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (NC-IUBMB), microbial collagenases are classified as metalloproteases (MMP). Interestingly, karilysin from T. forsythia is one of the prokaryotic MMP characterized at the functional and structural level50,51. BFoR_1659 does not belong to the MMP family. To date, only Clostridium sp collagenases (C. hystolyticum, C. tetani, and C. perfringens) marine collagenases (Vibrio alginolyticus) collagenases from Penicillium auranteogriseum, Rhizoctonia solani, and Bacillus spp. are considered true microbial collagenases51.

It has been proposed that collagenolysis is started by human collagenases, and later the microbial collagen-degrading proteins are responsible for the degradation of the uncoiled or pre-digested collagen. Based on the present results, it is possible that BFoR_1659 might work in coordination with human collagenases to the breakdown of collagen. Moreover, human DPP IV can degrade cytokines containing X-Pro or X-Ala at their N-terminus ends, such as RANTES (Regulated on Activation, Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted), MDC (Monocyte-Derived Chemokine) and SDF-1 (Stromal-Derived Factors)52,53. As shown in this manuscript, BFoR_1659, human and P. gingivalis DPPIV harbor the same active site, with some differences at the S1 and S2 pocket. The active site on the three proteins is located at Ser-593, Asp-668, and His-700 (adopting BFoR_1659 numbering). The S1-pocket is hydrophobic and the lipophilic residues Tyr-594, Tyr-629, Trp-622, and Val-619 are also almost identical between the three proteins. BFoR_1659 harbors Phe instead of Tyr-594 and Pro instead of Val. In the S2-pocket P. gingivalis, DPP IV and BFoR_1659 lack the phenylalanine and arginine present in human DPPIV. In the three enzymes, the positive charge of the amino terminus of the substrate peptide is neutralized by the negative charge from the two glutamate residues flanking S2-pocket at the Glu-195 and Glu-196 (Fig 1). By comparing structural sequence features, it is tempting to think that BFoR_1659 could help in the attenuation of the immune response or has similar biological activities; however, a completely new set of experimentation would be needed to prove that concept.

In this report, we have also explored BFoR_1659 localization. It is known that secreted proteins are important in bacterial pathogenesis by invading surrounded tissue which might also facilitate toxin diffusion52,54. We found that BFoR_1659 is a secreted protein. Contrary to P. gingivalis DPP IV which is also a secreted protein but remains associated with the membrane and to human DPP IV that is on the cellular membrane55, BFoR_1659 is released into the medium. Interestingly, the time series experiments showed a peak of secretion at 4 days of growth, at the end of its exponential growth curve. It has been also reported that in E. facealis and L. monocitogenes the expression of gelatinases is higher at the end of the logarithmic phase56.

The fact that BFoR_1659 is secreted into the tissue and is able to degrade collagen can give T. forsythia an ecological advantage compared with non-collagenolytic bacteria. Degradation of some extracellular components could help T. forsythia reach the anaerobic environment in deep periodontal sites52,53.

It is known that the subgingival microbiota produces proteolytic enzymes; some are secreted, bound within the cell envelope or shed in vesicles. P. gingivalis, the most studied member of the “red complex”, expresses periodontain, a well-characterized cysteine protease57. Periodontain can degrade gelatin but not native collagen or fibrinogen55. Another well-characterized enzyme from P. gingivalis is the exopeptidase prolyl tripeptidyl peptidase A (PtpA). PtpA is a cell surface associated serine peptidase involved in the final processing of collagen/gelatin58–60. Interestingly, Arg-gingipains from P. gingivalis can cleave type I collagen, only when they are attached to the cell surface61. DPP IV activity in P. gingivalis is associated with whole cells and washed cell membranes58 but not in the supernatant as is the case of BFoR_1659, the DPP IV in T. forsythia.

Recently it has been documented that T. forsythia can degrade collagen types I, III, and IV. However, this activity has been associated with proteins linked to the membrane62 and in the sonic extract of T. forsythia63, and it is therefore independent of BFoR_1659 activity. It is tempting to think that the destruction of the periodontium is a coordinated event of the action of enzymes produced by the oral microbial community and one of the reasons why the oral pathogens persist, causing disease.

BFoR_1659 harbors a signal peptide at the N-terminus, with a predicted cleavage site between two glutamines Q-Q at positions 21 and 22 that suggests the transit of this protein to the outer membrane. P. gingivalis DPP IV signal peptide is found at position 17 and 18 between threonine and glutamine (Q-T) while human DPP IV does not harbor a signal peptide since it is a membrane protein (Fig 1). To date, the transport system of BFoR_1659 is unknown. In bacteria, two major pathways have been described for secretion of proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane: the general Secretion route (Sec-pathway) and the Twin-arginine pathway (Tat-pathway)56. We previously showed that SecD, SecE, SecY, described in the Sec-pathway, as well as twin-arginine targeting, translocated proteins (TatA-E) were up-regulated in T. forsythia during disease progression20. Those results might suggest that the transport system of BFoR_1659 could be a mix of secretion pathways, however further investigation needs to be done to prove that concept.

In the present study, we characterized BFoR_1569 as degrading protein using different types gelatin, collagen type I, III and native collagen. Gelatin is a form of partially hydrolyzed collagen that is a substrate for a wide variety of proteases. It has been reported that P. gingivalis has glycyl-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase to act on partially digested collagen and gelatin64 and P. gingivalis PrtT cysteine protease is linked to degradation of only denatured or easily accessible peptides58,64. In our experiments, rDPPIV and the supernatant samples showed the capacity to digest gelatin. The gelatinolytic activity was deficient in the independent motifs rDppIV-N and rPepS_9. Interestingly, the cell lysate showed activity suggesting the T. forsythia possesses membrane-associated proteins with gelatinolytic capacity. FALGPA a synthetic peptide that mimics the structure of collagen type I, was efficiently hydrolyzed rDPP IV. Contrary to other tests, rDPPIV was able to hydrolyze FALGPA more efficiently than the supernatant sample. These results suggest that other components present in the supernatant could inhibit either the hydrolysis of FALGPA or that the concentration of BFoR_1659 in the supernatant is lower than the pure rDPPIV. These results highlight the importance of testing a range of different substrates. Both independent domains showed similar hydrolysis, lower than the complete protein. our results suggested that besides BFoR_1659 T. forsythia secretes other proteins with the ability to digest collagen-like substrates and gelatin.

BFoR_1659 was also able to degrade collagen type I and III present in Bio-Gide® membranes and on cultures of human gingival fibroblasts. It has been reported that Treponema denticola and P. gingivalis have the capacity to degrade Bio-Gide® membranes, but not their culture supernatants. The oral pathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans cannot, however, degrade collagen type I and III in those membranes65. For combined collagens, this trend was similar to degradation of collagen-like substrates. As stated above, the gingival tissue is formed by a mix of type I and type III primarily; therefore we tested BFoR_1659 ability to cleave the extracellular matrix on cultures of human gingival fibroblasts since the degradation of all types of collagens is crucial for bacterial subgingival invasion66.

The degradation of the ECM was evident in the cell culture images. It is described that fibroblasts are also collagenase producers. Those enzymes are released during wound healing, cancer, fertility and infection diseases. Bauer E. et al. 1975, demonstrated that fibroblasts in cell culture could release active form of collagenases either after withdrawing of serum or during preincubation with trypsin67. To evaluate BFoR_1659 ability to break down collagen we controlled the HGF-1 production of collagenase by adding whole serum in the medium. Despite that, it is possible that fibroblasts might contribute a small level to the destruction of collagen in the extracellular matrix of HGF-1 cultures. However, the higher degradation of ECM was observed only after incubation with rDPPIV not when the independent domains were tested. Those results suggest that BFoR_1659 needs to be complete to show full activity.

Recently two proteases have been identified in T. forsythia with the collagenolytic activity that does not share consensus sequences with BFoR_1659: a chymotrypsin-like serine protease that cleaves collagen type I but not type IV62 and KLIKK proteases that degrades host proteins including collagen17.

There is a growing evidence implicating T. forsythia in periodontal destruction. In this work we show that BFoR_1659 can break down gelatin, collagen type I, a combination of collagen types I and type III, and native collagen present in HGF-1 cultures. Based on the results we propose that T. forsythia might contribute to the destruction of periodontium by breaking down collagen through BFoR_1659 activity during periodontitis progression.

Acknowledgments

Research in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (HIDCR) of the National Institutes of Health (R03DE023394). We are also grateful to Dr. Blanca Barquera for reviewing the manuscript and her useful comments and Dr. Yan Xu for her recommendations on tissue cell culture experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans Go, Genco RJ, CDC Periodontal Disease Surveillance workgroup: James Beck (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA), Gordon Douglass (Past President, American Academy of Periodontology), Roy Page (University of Washin. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;91(10):914–920. doi:10.1177/0022034512457373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Vos P, Stefanini A, De Ceukelaire W, Schuftan C, People’s Health Movement. A human right to health approach for non-communicable diseases. Lancet Lond Engl. 2013;381(9866):533. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck JD, offenbacher S. Systemic effects of periodontitis: epidemiology of periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 2005;76(11 Suppl):2089–2100. doi:10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanner ACR, Izard J. Tannerella forsythia, a periodontal pathogen entering the genomic era. Periodontol 2000. 2006;42:88–113. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RLJ. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(2):134–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holt SC, Ebersole JL. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia: the “red complex”, a prototype polybacterial pathogenic consortium in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:72–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorth P, Turner KH, Gumus P, Nizam N, Buduneli N, Whiteley M. Metatranscriptomics of the human oral microbiome during health and disease. mBio. 2014;5(2):e01012–1014. doi:10.1128/mBio.01012-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duran-Pinedo AE, Chen T, Teles R, Starr JR, Wang X, Krishnan K, Frias-Lopez J. Community-wide transcriptome of the oral microbiome in subjects with and without periodontitis. ISME J. 2014;8(8):1659–1672. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamlet SM, Ganashan N, Cullinan MP, Westerman B, Palmer JE, Seymour GJ. A 5-year longitudinal study of Tannerella forsythia prtH genotype: association with loss of attachment. J Periodontol. 2008;79(1):144–149. doi:10.1902/jop.2008.070228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machtei EE, Dunford R, Hausmann E, Grossi SG, Powell J, Cummins D, Zambon JJ, Genco RJ. Longitudinal study of prognostic factors in established periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24(2):102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inagaki S, onishi S, Kuramitsu HK, Sharma A. Porphyromonas gingivalis vesicles enhance attachment, and the leucine-rich repeat BspA protein is required for invasion of epithelial cells by “Tannerella forsythia.” Infect Immun. 2006;74(9):5023–5028. doi:10.1128/IAI.00062-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito T, Ishihara K, Kato T, okuda K. Cloning, expression, and sequencing of a protease gene from Bacteroides forsythus ATCC 43037 in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1997;65(11):4888–4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grenier D, Bertrand J, Mayrand D. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles promote bacterial resistance to chlorhexidine. oral Microbiol Immunol. 1995;10(5):319–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa I, Nakashima K, Koseki T, Nagasawa T, Watanabe H, Arakawa S, Nitta H, Nishihara T. Induction of the immune response to periodontopathic bacteria and its role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:79–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanner A, Maiden MF, Macuch PJ, Murray LL, Kent RL. Microbiota of health, gingivitis, and initial periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(2):85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karim AY, Kulczycka M, Kantyka T, Dubin G, Jabaiah A, Daugherty PS, Thogersen IB, Enghild JJ, Nguyen K-A, Potempa J. A novel matrix metalloprotease-like enzyme (karilysin) of the periodontal pathogen Tannerella forsythia ATCC 43037. Biol Chem. 2010;391(1):105–117. doi:10.1515/BC.2010.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ksiazek M, Karim AY, Bryzek D, Enghild JJ, Thøgersen IB, Koziel J, Potempa J. Mirolase, a novel subtilisin-like serine protease from the periodontopathogen Tannerella forsythia. Biol Chem. 2015;396(3):261–275. doi:10.1515/hsz-2014-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ksiazek M, Mizgalska D, Eick S, Thøgersen IB, Enghild JJ, Potempa J. KLIKK proteases of Tannerella forsythia: putative virulence factors with a unique domain structure. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:312. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veith PD, o’Brien-Simpson NM, Tan Y, Djatmiko DC, Dashper SG, Reynolds EC. outer membrane proteome and antigens of Tannerella forsythia. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(9):4279–4292. doi:10.1021/pr900372c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yost S, Duran-Pinedo AE, Teles R, Krishnan K, Frias-Lopez J. Functional signatures of oral dysbiosis during periodontitis progression revealed by microbial metatranscriptome analysis. Genome Med. 2015;7(1):27. doi:10.1186/s13073-015-0153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uitto VJ, Suomalainen K, Sorsa T. Salivary collagenase. origin, characteristics and relationship to periodontal health. J Periodontal Res. 1990;25(3):135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eley BM, Cox SW. The relationship between gingival crevicular fluid cathepsin B activity and periodontal attachment loss in chronic periodontitis patients: a 2-year longitudinal study. J Periodontal Res. 1996;31(6):381–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller EJ, Epstein EH, Piez KA. Identification of three genetically distinct collagens by cyanogen bromide cleavage of insoluble human skin and cartilage collagen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;42(6):1024–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedrich V, Pabinger S, Chen T, Messner P, Dewhirst FE, Schäffer C. Draft Genome Sequence of Tannerella forsythia Type Strain ATCC 43037. Genome Announc. 2015;3(3). doi:10.1128/genomeA.00660-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasmussen HB, Branner S, Wiberg FC, Wagtmann N. Crystal structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase IV/CD26 in complex with a substrate analog. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10(1):19–25. doi:10.1038/nsb882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nabeno M, Akahoshi F, Kishida H, Miyaguchi I, Tanaka Y, Ishii S, Kadowaki T. A comparative study of the binding modes of recently launched dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors in the active site. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;434(2):191–196. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metzler WJ, Yanchunas J, Weigelt C, Kish K, Klei HE, Xie D, Zhang Y, Corbett M, Tamura JK, He B, Hamann LG, Kirby MS, Marcinkeviciene J. Involvement of DPP-IV catalytic residues in enzyme-saxagliptin complex formation. Protein Sci Publ Protein Soc. 2008;17(2):240–250. doi:10.1110/ps.073253208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rea D, Van Elzen R, De Winter H, Van Goethem S, Landuyt B, Luyten W, Schoofs L, Van Der Veken P, Augustyns K, De Meester I, Fülöp V, Lambeir A-M. Crystal structure of Porphyromonas gingivalis dipeptidyl peptidase 4 and structure-activity relationships based on inhibitor profiling. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;139:482–491. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Lullo GA, Sweeney SM, Korkko J, Ala-Kokko L, San Antonio JD. Mapping the ligand-binding sites and disease-associated mutations on the most abundant protein in the human, type I collagen. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(6):4223–4231. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kadler KE, Baldock C, Bella J, Boot-Handford RP. Collagens at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 12):1955–1958. doi:10.1242/jcs.03453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manka SW, Carafoli F, Visse R, Bihan D, Raynal N, Farndale RW, Murphy G, Enghild JJ, Hohenester E, Nagase H. Structural insights into triple-helical collagen cleavage by matrix metalloproteinase 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(31):12461–12466. doi:10.1073/pnas.1204991109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silver FH, Freeman JW, Seehra GP. Collagen self-assembly and the development of tendon mechanical properties. J Biomech. 2003;36(10):1529–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almeida T, Valverde T, Martins-Júnior P, Ribeiro H, Kitten G, Carvalhaes L. Morphological and quantitative study of collagen fibers in healthy and diseased human gingival tissues. Romanian J Morphol Embryol Rev Roum Morphol Embryol. 2015;56(1):33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg GA, Estrada E, Kelley Ro, Kornfeld M. Bacterial collagenase disrupts extracellular matrix and opens blood-brain barrier in rat. Neurosci Lett. 1993;160(1):117–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elgün S, ozmeriç N, Demirtaş S. Alanine aminopeptidase and dipeptidyl peptidase IV in saliva: the possible role in periodontal disease. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem. 2000;298(1–2):187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eley BM, Cox SW. Proteolytic and hydrolytic enzymes from putative periodontal pathogens: characterization, molecular genetics, effects on host defenses and tissues and detection in gingival crevice fluid. Periodontol 2000. 2003;31:105–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartold PM, McCulloch CA, Narayanan AS, Pitaru S. Tissue engineering: a new paradigm for periodontal regeneration based on molecular and cell biology. Periodontol 2000. 2000;24:253–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S, Lesnik EA, Hall TA, Sampath R, Griffey RH, Ecker DJ, Blyn LB. A bioinformatics based approach to discover small RNA genes in the Escherichia coli genome. Biosystems. 2002;65(2–3):157–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo Y, Wu Y, Liu T, Zhang J, Xiao X, Zhao L. [Interleukin-8 regulations of oral epithelial cells by Porphyromonas gingivalis with different fimA genotypes]. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi Huaxi Kouqiang Yixue Zazhi West China J Stomatol. 2008;26(6):652–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis MA, Kuramitsu HK, Lantz M, Macrina FL, Nakayama K, Potempa J, Reynolds EC, Aduse-opoku J. Molecular genetics and nomenclature of proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Periodontal Res. 1999;34(8):464–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasmussen HB, Branner S, Wiberg FC, Wagtmann N. Crystal structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase IV/CD26 in complex with a substrate analog. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10(1):19–25. doi:10.1038/nsb882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nabeno M, Akahoshi F, Kishida H, Miyaguchi I, Tanaka Y, Ishii S, Kadowaki T. A comparative study of the binding modes of recently launched dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors in the active site. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;434(2):191–196. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumagai Y, Konishi K, Gomi T, Yagishita H, Yajima A, Yoshikawa M. Enzymatic properties of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV produced by the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis and its participation in virulence. Infect Immun. 2000;68(2):716–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abiko Y, Hayakawa M, Murai S, Takiguchi H. Glycylprolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Bacteroides gingivalis. J Dent Res. 1985;64(2):106–111. doi:10.1177/00220345850640020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rigolet P, Xi XG, Rety S, Chich J-F. The structural comparison of the bacterial PepX and human DPP-IV reveals sites for the design of inhibitors of PepX activity. FEBS J. 2005;272(8):2050–2059. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yagishita H, Kumagai Y, Konishi K, Takahashi Y, Aoba T, Yoshikawa M. Histopathological studies on virulence of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV (DPPIV) of Porphyromonas gingivalis in a mouse abscess model: use of a DPPIV-deficient mutant. Infect Immun. 2001;69(11):7159–7161. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.11.7159-7161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gross J, Nagai Y. Specific degradation of the collagen molecule by tadpole collagenolytic enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1965;54(4):1197–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang S, Singh S, Winkelstein BA. Collagen organization regulates stretch-initiated pain-related neuronal signals in vitro: Implications for structure-function relationships in innervated ligaments. J orthop Res off Publ orthop Res Soc. July 2017. doi:10.1002/jor.23657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duarte AS, Correia A, Esteves AC. Bacterial collagenases - A review. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016;42(1):106–126. doi:10.3109/1040841X.2014.904270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MERoPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D343–350. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mookhtiar KA, Van Wart HE. Clostridium histolyticum collagenases: a new look at some old enzymes. Matrix Stuttg Ger Suppl. 1992;1:116–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grenier D, Uitto VJ, McBride BC. Cellular location of a Treponema denticola chymotrypsinlike protease and importance of the protease in migration through the basement membrane. Infect Immun. 1990;58(2):347–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loesche WJ, Paunio KU, Woolfolk MP, Hockett RN. Collagenolytic activity of dental plaque associated with periodontal pathology. Infect Immun. 1974;9(2):329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grenier D, La VD. Proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis as important virulence factors in periodontal disease and potential targets for plant-derived compounds: a review article. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12(3):322–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banbula A, Bugno M, Goldstein J, Yen J, Nelson D, Travis J, Potempa J. Emerging family of proline-specific peptidases of Porphyromonas gingivalis: purification and characterization of serine dipeptidyl peptidase, a structural and functional homologue of mammalian prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Infect Immun. 2000;68(3):1176–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakayama J, Cao Y, Horii T, Sakuda S, Akkermans ADL, De Vos WM, Nagasawa H. Gelatinase biosynthesis-activating pheromone: a peptide lactone that mediates a quorum sensing in Enterococcus faecalis. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41(1):145–154. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nelson D, Potempa J, Kordula T, Travis J. Purification and characterization of a novel cysteine proteinase (periodontain) from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Evidence for a role in the inactivation of human alpha1-proteinase inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(18):12245–12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Banbula A, Mak P, Bugno M, Silberring J, Dubin A, Nelson D, Travis J, Potempa J. Prolyl tripeptidyl peptidase from Porphyromonas gingivalis. A novel enzyme with possible pathological implications for the development of periodontitis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(14):9246–9252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee W, McCulloch CA. Deregulation of collagen phagocytosis in aging human fibroblasts: effects of integrin expression and cell cycle. Exp Cell Res. 1997;237(2):383–393. doi:10.1006/excr.1997.3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Potempa J, Mikolajczyk-Pawlinska J, Brassell D, Nelson D, Thøgersen IB, Enghild JJ, Travis J. Comparative properties of two cysteine proteinases (gingipains R), the products of two related but individual genes of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(34):21648–21657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Houle M-A, Grenier D, Plamondon P, Nakayama K. The collagenase activity of Porphyromonas gingivalis is due to Arg-gingipain. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;221(2):181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hockensmith K, Dillard K, Sanders B, Harville BA. Identification and characterization of a chymotrypsin-like serine protease from periodontal pathogen, Tannerella forsythia. Microb Pathog. 2016;100:37–42. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2016.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kawase N, Kishi J, Nakamura H, Hayakawa T. Collagenolytic activity in sonic extracts of Tannerella forsythia. Arch oral Biol. 2010;55(8):545–549. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Potempa J, Banbula A, Travis J. Role of bacterial proteinases in matrix destruction and modulation of host responses. Periodontol 2000. 2000;24:153–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sela MN. Role of Treponema denticola in periodontal diseases. Crit Rev oral Biol Med off Publ Am Assoc oral Biol. 2001;12(5):399–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakurai Y, Sullivan M, Yamada Y. Alpha 1 type IV collagen gene evolved differently from fibrillar collagen genes. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(15):6654–6657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bauer EA, Stricklin GP, Jeffrey JJ, Eisen AZ. Collagenase production by human skin fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;64(1):232–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]