Abstract

Introduction:

Violence is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality for youth, with more than 600,000 emergency department visits annually for assault-related injuries. Risk for criminal justice involvement among this population is poorly understood. The objective of this study was to characterize arrests among high-risk assault-injured drug-using youth following emergency department treatment.

Methods:

Youth (age 18–24 years) with past 6-month drug use who were seeking emergency department treatment for either an assault or for non-violence reasons were enrolled (December 2009–September 2011) in a 2-year longitudinal study. Arrests in the 24 months following the emergency department visit were analyzed in 2016–2017 using survival analysis of objective Law Enforcement Information Network data. Hazard ratios quantifying the association between risk factors for arrest were estimated using Cox regression.

Results:

In the longitudinal cohort, 511 youth seeking emergency department care (assault injury group=299, comparison group=212) were aged ≥18 years and were included for analysis. Youth in the assault injury group cohort had a 47% higher risk of arrest than the comparison group (38.1% vs 25.9%, RR=1.47, p<0.05). In unadjusted analyses, male sex, assault injury, binge drinking, drug use disorder, and community violence exposure were all associated with increased risk of arrest during the follow-up period. Cox regression identified that male sex (hazard ratio=2.57), drug use disorder diagnosis (hazard ratio=1.42), assault injury at baseline (hazard ratio=1.63), and community violence exposure (hazard ratio=1.35) increased risk for arrest.

Conclusions:

Drug-using assault-injured youth have high rates of arrest. Emergency department and community interventions addressing substance use and violence involvement may aid in decreasing negative violence and criminal justice outcomes among high-risk youth.

INTRODUCTION

Youth violence is a significant public health problem.1,2 Homicides are the third leading cause of death for U.S. youth (aged 14–24 years).3 Assault-related injuries are responsible for 600,000 emergency department (ED) visits among youth annually.3 In addition to negative health-related outcomes (e.g., substance use, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], fatal injury),4–6 youth violence has been associated with adverse social consequences, most notably criminal justice involvement.7,8 Nearly 1.2 million youth were arrested in 2015, with 30% of arrests attributable to substance use, weapon, or violence-related offences.9 Disparities are significant, with homicide, violent injury, arrest, and incarceration rates persistently higher for black youth than similarly aged white youth.1,3,10,11 Economic costs are also substantial, with interpersonal violence costs approaching $37 billion annually.12

The effects of an arrest and subsequent incarceration on healthy adolescent development are considerable. Such youth face loss of peer and parental social support, as well as elevated rates of school dropout, substance use, repeat arrest, and adult incarceration.13 Youth offenders have a 50% higher 5-year mortality than non-offenders, with rates increasing substantially as the extent of their involvement progresses from arrest to juvenile detention, incarceration, and transfer to adult court.14 Notably, even when such youth re-engage within their communities, they face low rates of employment, poor access to insurance/health care, family instability, and elevated rates of poverty.11,15 These factors exacerbate the cycle of violence involvement, increasing the likelihood that they re-engage with violent behaviors that increase negative health and social outcomes.

Urban EDs that serve as the primary setting for treating assault-injured youth1,16–18 have emerged as an important venue for violence prevention.19–21 ED- and hospital-based violence prevention programs, recognizing the negative effect of criminal justice involvement on health outcomes, have begun to emphasize the reduction of arrest and incarceration as important outcome measures.1,8,22–24 However, although prior longitudinal studies have characterized criminal justice outcomes among general youth populations,25–27 none have examined the subpopulation of youth seeking assault-injury treatment. Prior ED/hospital-based studies of assault-injured youth have provided mixed results as to whether an assault injury is a marker for increased criminal justice involvement.28,29 Such research has also been limited by non-comparable control groups,30 convenience samples,31 and trauma registry29 or self-report data.32 Further, among assault-injured youth seeking treatment, 55% report recent substance use.33 Substance use is an important risk factor based on theories of problem behavior clustering,34 the pharmacological effects of acute intoxication,35 and the violent nature of the illicit drug trade.36 Thus, an enhanced understanding of criminal justice outcomes among higher-risk drug-using youth following an assault injury is critical to implementing effective prevention strategies.

The primary study objective is to examine rates and characteristics of arrest among drug-using youth (i.e., ages 18–24 years) following ED treatment for assault as compared with a drug-using sample seeking care for other reasons. From prior work5,6,37 and theory,34 it is hypothesized that drug-using assault-injured youth will have higher arrest rates and that arrest risk will be associated with potentially modifiable risk factors, including higher severity substance use, mental health, and violence involvement. Results will aid the design of interventions focused on addressing multiple violence-related outcomes, including criminal justice involvement.

METHODS

The Flint Youth Injury Study5,6,33,38,39 is a 2-year longitudinal study characterizing substance use and violence outcomes among a consecutively obtained sample of assault-injured youth (original sample ages:14–24 years) with past 6-month drug use (AIG) and a comparison group (CG) of non-assaulted drug-using youth. This analysis focuses on arrests among the AIG and CG cohorts between ages 18 and 24 years. University of Michigan and Hurley Medical Center (HMC) IRBs approved study procedures; a NIH Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained.

Study Sample

This sample was recruited within the HMC ED in Flint, Michigan. HMC is the region’s only Level-1 trauma center, providing care to ≅75,000 adults and ≅25,000 children annually. The study population reflects the sociodemographics of Flint,40 which is 50%–60% black, and is similar to prior HMC studies.41–43 Flint violent crime rates are comparable to other deindustrialized urban settings.44

Recruitment proceeded December 2009–September 2011. Research assistants (RAs) recruited participants 7 days/week (excluding holidays), 21 hours/day (5:00AM–2:00AM) on Tuesday/Wednesday, and 24 hours/day Thursday through Monday. Eligible participants included youth seeking treatment for assault and reporting past 6-month drug use, and youth recruited for a proportionately sampled CG of youth seeking care for reasons other than assault (e.g., abdominal pain, sprained ankle from fall) and reporting past 6-month drug use. Assault was defined as any intentional injury caused by another person. Exclusion criteria included presentation for sexual assault, suicidal ideation/attempt, child maltreatment, or cognitive conditions precluding consent (e.g., intoxication). Incarcerated youth (3.2%) and those not speaking English (<1%) were excluded. Unstable trauma patients were recruited if they stabilized within 72 hours.

Detailed methods have been published.33 RAs utilized electronic patient logs to identify potentially eligible participants. After consent, patients were screened for eligibility using a self-administered computerized survey. Those screening positive for past 6-month illicit or non-medical prescription drug use on the NIDA–ASSIST were eligible. The CG was recruited in parallel to limit seasonal/temporal variation and was systematically enrolled to balance cohorts by sex/age. Enrolled participants completed a 90-minute baseline assessment, including a computerized survey and an RA-administered diagnostic interview. In-person follow-ups were at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. Although incarcerated youth were not recruited, follow-ups were conducted with consenting youth who were in jail/incarcerated during follow-up. Remuneration was $1 for the screen, $20 for the baseline, and $35, $40, $40, and $50 for the 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-month follow-ups, respectively.

Measures

Arrest records were obtained from the Michigan State Police Law Enforcement Information Network.45 Data includes arrest date, offense, and judicial disposition. Offenses were categorized: violent crime, property-related crime, weapon-related, alcohol/drug offense, sexual offense, operating vehicle while impaired, obstruction of justice/police, or an administrative offense (e.g., bribery). Judicial dispositions included: arrest without charge, case dismissal, case delayed/closed, jail/prison sentence, probation, judicial fines/restitution, and assignment to personal development program (e.g., community service). Offense and disposition categories were not mutually exclusive.

Sociodemographic measures (age, male, race/ethnicity, public assistance) were from the Adolescent Health and Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Studies.46–48 Any participant/parental receipt of a government assistance program (e.g., welfare, bridge card, disability) was included as an affirmative response. Extra-curricular school (e.g., clubs) and community program (e.g., Big Brothers/Big Sisters) involvement was measured using two-items from the Flint Adolescent Study.49 Items were asked of all participants as some school-based activities may apply to college age students. The response scale was dichotomized to indicate any involvement in the prior 6 months. Community violence exposure was assessed with five-items (heard gun shots, seen drug deals, my house has been broken into, seen someone get shot/stabbed, and seen neighborhood gangs) measured using a Likert-type scale ranging from zero (“never”) to three (“many times”) from the “Things I Have Seen and Heard Survey.”50,51 For analysis, a summary score was created.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test52 and NIDA–ASSIST53,54 separately measured past 6-month substance use, including alcohol, marijuana, illicit drugs (cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine, street opioids), and non-medical use of prescription drugs (opioids, sedatives, stimulants). Binge drinking was defined as more than five drinks on a single occasion. Substance use variables were dichotomized (yes/no). The RA-administered Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview assessed DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for: (1) drug use disorder (i.e., abuse/dependence of marijuana, illicit drugs, or prescription drugs), (2) depression, (3) anti-social personality or conduct disorder, and (4) PTSD.55 For analysis, any mental health diagnosis included meeting criteria for depression, anti-social personality disorder, conduct disorder, or PTSD.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were restricted to youth age 18 years at enrollment as Law Enforcement Information Network data were only available for adult youth. Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations with the dependent variable, arrest in the 24 months following the ED visit, were examined. Time to arrest for AIG and CG were plotted using Kaplan–Meier estimators of the survival function with their associated confidence bands. Cox regression was performed to identify baseline characteristics associated with increased arrest hazard (i.e., factors that increased or decreased the expected time until arrest). Independent variables were chosen based on bivariate significance (male, assault injury, drug use disorder, community violence exposure) and theory (age, race, public assistance, mental health). Drug use disorder was retained over marijuana given that drug use disorder is inclusive of marijuana use abuse or dependence.

RESULTS

Overall, 599 youth (AIG=349, CG=250) were enrolled in the longitudinal study. Baseline characteristics and the flowchart have been previously published.6 Of note, 75.6% of the CG patients were seeking care for a medical issue (e.g., abdominal pain), with the remainder seeking care for an unintentional injury (e.g., motor-vehicle crash). No differences were noted between the baseline cohorts with regards to age, sex, race, or SES. Follow-up rates were 85.5% at the 6-month, 83.8% at the 12-month, 84.3% at the 18-month, and 85.5% at the 24-month follow-up, with no differential follow-up.6 On average, 3.5% of follow-ups at each timepoint were conducted in prison/jail. Among the sample, 511 (AIG=299, CG=212) youth were aged ≥18 years at baseline and were included in this analysis. Among the analytic sample (n=511), 57.1% of youth were male, 58.3% identified as black, and 73.2% were on public assistance.

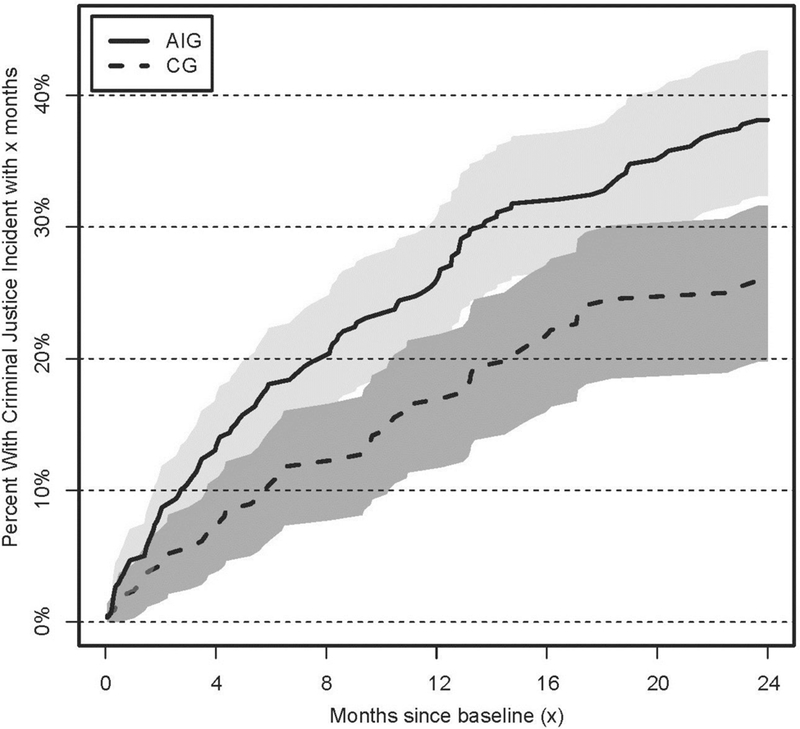

Risk of arrest in the 24 months following the ED visit was 47% higher in the AIG than the CG (38.1% vs 25.9%, RR=1.47, 95% CI=1.07, 2.02). Figure 1 depicts the Kaplan–Meier survival curve estimates for both the CG and AIG; from that it is apparent that the expected time until arrest is shorter for the AIG group. The AIG also had a higher average number of arrests per participant than the CG (2.00 vs 1.55, p<0.01) and a higher proportion of AIG youth had more than one arrest during the study (21.1% vs 9.0%, p<0.001). Table 1 presents descriptive data on the 313 arrests among 195 participants (with one or more arrests). Nearly 41% of arrests were for violent or weapon-related crimes. When compared with the CG, the AIG had a higher proportion of arrests for property crime. Among 313 arrests, 44.4% did not result in formal charges and for the 174 arrests where criminal charges were filed, 30.5% resulted in fines or monetary restitution, 23.6% involved jail/prison time, 17.2% involved probation, and 5.8% involved diversionary programs. No group differences for judicial disposition were identified.

Figure 1. Cumulative frequency of time to first arrest during the 24-month follow-up by cohort (AIG; CG).

AIG, assault injury group; CG, comparison group.

Table 1.

Criminal Offence Categories for Arrests (n=313 Arrests/195 Participants) During the 24-month Follow-up by Cohort (AIG; CG)

| Category | Assault-injury group N=228 (72.8%) |

Comparison group N=85 (27.2%) |

Total arrests N=313 |

RRa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violent crime/Weapon offence |

95 (41.7) | 32 (37.7) | 127 (40.6) | 1.11 (0.81, 1.51) |

| Property crime | 73 (32.0) | 16 (18.8) | 89 (28.4) |

1.70 (1.05, 2.75) |

| Administrative offences | 16 (7.0) | 6 (7.1) | 22 (7.0) | 0.99 (0.40, 2.26) |

| Alcohol offenses | 4 (1.8) | 1 (1.2) | 5 (1.6) | 1.49 (0.17, 13.15) |

| Drug offenses | 48 (21.1) | 19 (22.4) | 67 (21.4) | 0.94 (0.59, 1.51) |

| Sexual offensesa | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | NA |

| Operating while impaired | 27 (11.8) | 16 (18.8) | 43 (13.7) | 0.63 (0.36, 1.11) |

| Obstructing police | 30 (13.2) | 7 (8.2) | 37 (11.8) | 1.60 (0.73, 3.50) |

Notes: Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Participants may have more than one arrest; denominator is total number of arrest incidents. Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05). Notation about offences: Examples of each type of offence are provided. List not exhaustive. Violent crime/Weapon offence = Homicide, kidnapping, sexual assault, robbery, assault, inappropriate possession, carrying, sales or trafficking or firearms. Property crime = robbery, arson, extortion, burglary, larceny, stolen vehicle, forgery and counterfeiting, embezzlement, stolen or damaged property. Administrative offences = Obscenity, gambling, escape and flight, obstruction of judiciary, congress or legislative proceedings, bribery, disturbing public peace, traffic offenses, health and safety violations, civil rights violation, invasion of privacy, or vagrancy. Alcohol or drug offences = Drunkenness, dangerous drug intoxication or possession. Sexual offences = Sexual assault, commercializing sex. Operating while impaired = Driving while under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Obstructing police = Impairing the proceedings of a police investigation.

Risk ratio is non-finite because one risk is zero.

Participants who were arrested were more likely than those not arrested to be male, have a baseline assault injury, binge drink, use marijuana, meet criteria for a drug use disorder, and report higher levels of community violence exposure (Table 2). No differences were noted for the other baseline characteristics or for other substance use and mental health variables.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Youth (n=511) With and Without an Arrest During the 24-Months Follow-up Period

| Characteristics | Arrest within the 24-months after baseline ED visit (N=169; 33.1%) |

No arrest within the 24-months after baseline ED visit (N=342; 66.9%) |

RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age, years, mean (SD)a | 20.79 (1.87) | 20.70 (1.94) | 1.02 (0.95, 1.08) |

| Male, n (%) | 127 (75.2) | 165 (48.3) |

1.56 (1.35, 1.79) |

| Black race, n (%) | 100 (59.2) | 198 (57.9) | 1.02 (0.88, 1.19) |

| Public assistance, n (%) | 126 (74.6) | 248 (72.5) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) |

| School/Community involvement, n (%) |

54 (32.0) | 116 (33.9) | 0.94 (0.72, 1.23) |

| Community violence, mean (SD)a | 2.52 (0.70) | 2.27 (0.72) |

1.39 (1.17, 1.65) |

| Baseline ED visit presentation | |||

| Assault–Injury, n (%) | 114 (67.5) | 185 (54.1) |

1.24 (1.08, 1.44) |

| Past 6-month substance use at baseline ED visit |

|||

| Marijuana use, n (%)b | 167 (98.8) | 329 (96.2) |

1.03 (1.00, 1.06) |

| Illicit drug use, n (%)c | 23 (13.6) | 36 (10.5) | 1.29 (0.79, 2.11) |

| Non-medical prescription drug | 42 (24.9) | 63 (18.4) | 1.38 |

| use, n (%)d | (0.98, 1.94) | ||

| Binge drinking, n (%)e | 85 (50.3) | 139 (40.6) |

1.24 (1.02, 1.51) |

| Drug use disorder, n (%) | 112 (66.3) | 173 (50.6) |

1.31 (1.13, 1.52) |

| Mental health diagnoses at baseline | |||

| ED visit | |||

| PTSD (past month), n (%) | 19 (11.2) | 37 (10.8) | 1.04 (0.62, 1.75) |

| Any mental health diagnosis, n (%)f |

70 (41.4) | 113 (33.0) | 1.25 (0.99, 1.58) |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05). Baseline characteristics were measured at the time of the ED visit.

For mean-calculated variables, RR was estimated using binomial regression with a log link.

p-value is 0.049.

Illicit drugs includes cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine, street opioids (e.g., heroin).

Prescription drugs involves non-medical use (i.e., to get high and/or using someone else’s prescription) of prescription opioids, stimulants, or sedatives.

Binge drinking is 5 or more drinks consumed on a single occasion.

Any mental health diagnosis includes meeting diagnostic DSM-IV criteria for depression, antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder, or PTSD.

ED, emergency department; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Cox regression analysis demonstrating covariate effects on the hazard of arrest is shown in Table 3. The hazard of arrest was about 2.5 times larger among males. A diagnosis of assault injury and drug use disorder each corresponded to a 63% and 42% increased hazard, respectively. For each additional point on the community violence exposure scale, the hazard for arrest increased by ≅35%. Age, race/ethnicity, public assistance, and mental health diagnosis were not significantly related to the expected time until arrest. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by analyzing the Schoenfeld residuals and found to be tenable (x2=11.94, df=8, p=0.156).

Table 3.

Cox Regression Characterizing Covariate Effects on the Hazard of Criminal Justice Involvement During 24-month Follow-up

| Baseline characteristics | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 (0.92, 1.08) |

| Male | 2.57 (1.79, 3.67) |

| Black race | 1.02 (0.75, 1.40) |

| Public assistance | 1.20 (0.85, 1.71) |

| Drug use disorder | 1.42 (1.01, 2.00) |

| Any mental health diagnosisa | 0.98 (0.70, 1.38) |

| Assault-injury group | 1.63 (1.18, 2.25) |

| Community violence | 1.35 (1.06, 1.72) |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05). Baseline characteristics were measured at the time of the ED visit.

Any mental health diagnosis includes meeting diagnostic DSM-IV criteria for depression, antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

DISCUSSION

This study identified that nearly 40% of high-risk youth seeking ED treatment for assault experience at least one arrest within the 24 months following their visit, a 47% higher risk than CG youth. Although comparisons are difficult as this is the first longitudinal study to examine arrests among a systematically sampled cohort of assault-injured drug-using ED youth, results are comparable or higher than case-control/retrospective studies.8,22–24 Findings have implications for violence prevention. First, similar to research identifying that an assault injury increases the risk for violent injury recidivism,6 firearm violence,5 and substance use,37 findings suggest that it is also a marker for identifying youth at elevated risk for negative criminal justice outcomes. Second, the finding that more than 20% of AIG participants experienced more than one arrest and that a quarter of the participants who were charged with a crime received jail/prison time (less than 6% were sent to a diversionary program) reinforces that once youth are engaged within the justice system, they have an elevated risk of recidivism and negative outcomes that perpetuate the cycle of violence. This is consistent with research demonstrating that criminal justice involvement disrupts the transitional milestones necessary for a healthy progression from adolescence to adulthood (e.g., education, employment, family formation)13 and with data indicating that youth who experience official court processing instead of diversionary programs had higher rates of subsequent violent and non-violent criminal activity and were more likely to have an adult criminal record.56 This is particularly concerning in light of research showing that more severe criminal justice involvement (e.g., incarceration) is accompanied by higher mortality.14 Taken together, findings underscore the need for violence prevention initiatives that address risk for arrest and future incarceration as key outcome measures in parallel with violence.

Several hospital-based violence interventions focusing on intensive wrap-around services have demonstrated modest success reducing arrest and conviction rates for violent crimes during the post-injury period.8,22,23 Although the optimal structure of such interventions continues to be a focus of research, study data may aid the identification of components critical to enhancing intervention efficacy. The finding that arrests were higher among those with an assault injury and that more than 40% of all arrests were related to violence- and weapon-related charges raises concern for retaliatory violence stemming from the ED visit. This is consistent with data demonstrating that the immediate post-injury period is a high-risk time for retaliatory violence57,58 and that retaliation is a key motivation for youth violence, especially severe violence involving firearms.58–60 In addition, almost half of assault-injured youth indicated that they did not believe the altercation leading to their ED visit was over, and a quarter indicated that they or their friends/family intended to seek retribution.33 Thus, the need for violence initiatives to address retaliatory risk and include skills training on non-violent conflict resolution cannot be overstated.

Although all enrolled youth had drug use as a criterion of inclusion (96.8% reported marijuana use), those with a drug use disorder had a 42% higher risk of arrest. This, combined with the finding that a quarter of arrests were for drug- or alcohol-related offenses and that arrested youth had higher rates of binge drinking compared with those not arrested, emphasizes the need to address substance use and referral to treatment within violence prevention programs. Many hospital-based interventions, while showing promise, have not traditionally addressed substance use beyond referral to treatment.8,20,22,24,61–66 Yet, other researchers have demonstrated that single-session substance use67–69 and combined multisession collaborative care interventions70 addressing PTSD and associated comorbidities (e.g., substance use) are efficacious in reducing violence among lower at-risk youth. Thus, incorporating substance use treatment as a central component of interventions designed for higher-risk assault-injured youth may enhance efficacy, especially among youth in low-resource communities with limited access to treatment services.71–73 Although mental health diagnoses were not predictive of arrest, it is notable that approximately 36% of youth met criteria for at least one diagnosis. This, combined with research establishing an association between PTSD and violence,5,6 and studies demonstrating that providing ED youth with serious mental health disorders access to treatment reduces criminal justice involvement74 emphasizes the need to incorporate access to mental health services within prevention programs.

Higher perceived community violence exposure was associated with an elevated risk of arrest, emphasizing the need for interventions crossing multiple socioecologic levels. Within a theoretic context, community-level interventions focused on increasing social capital and community engagement are thought to enhance overall community organization, leading to lower rates of problem behaviors (e.g., violence) and improving neighborhood safety.75,76 Greening initiatives have demonstrated success with such an approach, decreasing rates of firearm violence, violent crime, and community stress, while improving perceptions of neighborhood safety.77 Recent research has also demonstrated the strength of combining individual-level hospital interventions with broader community-wide interventions, such as mentoring programs, neighborhood greening, and community policing, finding that a comprehensive intervention package addressing multiple socioecologic levels can be successful decreasing violent crime and assault injuries.76

Similar to prior research,78,79 males had a greater risk of arrest. Despite this, females accounted for one quarter of those arrested and half of youth seeking assault treatment,33 highlighting the need for interventions tailored for both sexes. Although SES was not associated with differential arrest risk, it is notable that more than 70% of youth reported receipt of public assistance, reflecting the high rates of poverty, unemployment and neighborhood disadvantage in this community. It is interesting to note, however, that AIG youth were noted to have higher rates of property-related crimes than the CG, highlighting monetary gain as a potential motivation for criminal activities. Future analyses should consider more sensitive SES measures as a means of exploring the role of poverty in criminal justice involvement. Interestingly, arrest rates did not differ by race/ethnicity, likely reflecting overall low variability between racial/ethnic categories in this sample.

Limitations

First, the study was conducted at a single urban hospital in a city that is approximately 60% black. Although results may not be generalizable to rural/suburban youth, or to communities with dissimilar ethnic compositions, the study context is not that dissimilar from other economically challenged small U.S. cities. Second, although arrest data was from objective sources, baseline measures were self-report. Researchers have, however, identified that self-reported behaviors are reliable/valid when privacy/confidentiality is assured and when self-administered by computer as in this study.80–85 Third, entry criterion included drug use. As such, the ability to generalize findings to assault-injured youth without drug use are limited. Yet, given that a single use of marijuana in the preceding 6 months qualified for inclusion, impact on generalizability is likely negligible. Further, as standardized measures did not assess traditional or synthetic forms of cannabis use, no comment was able to be made on the emerging trends of synthetic cannabis use. Fourth, the authors were not able to specifically link arrest data to a retaliation episode for the ED visit. Yet, self-report data on intention to retaliate collected at the ED visit (noted above) highlights the elevated retaliatory risk. Fifth, because access to arrest data was limited to adult youth (age 18 years or older), younger youth (age 14–17 years at baseline, n=88) were not able to be included. Finally, the age of the data (enrollment December 2009– September 2011) is a potential limitation; however, given the paucity of longitudinal studies examining objective criminal justice outcomes among high-risk youth, findings remain relevant to informing violence prevention initiatives.

CONCLUSIONS

Youth violence has been associated with multiple negative health and social outcomes, including criminal justice involvement. This study examines legal involvement of a cohort of assault-injured drug-using youth. The finding that rates of criminal arrest approach nearly 40% in the 24 months following the ED visit and that most relate to retaliatory violence, weapons, or substance use suggests that prevention efforts focused on reducing violence and substance use may have the potential to reduce criminal justice involvement and negative health-related outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge project staff, including Bethany Buschmann, MPH; Linping Duan, MS; Sonia Kamat; and Wendi Mohl, BS, for their assistance in data and manuscript preparation. Finally, special thanks are owed to the patients and medical staff of the Hurley Medical Center for their support of this project.

This work was funded by National Institute on Drug Abuse R01 024646 and in part, by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1R49CE002099 and NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse K23DA039341. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies. Dr. Carter authored the first draft of this manuscript. No honoraria, grants or other form of payment were received for producing this manuscript.

Trial registration: Clinical Trials Number - NCT01152970.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cunningham R, Knox L, Fein J, et al. Before and after the trauma bay: the prevention of violent injury among youth. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53(4):490–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kretman SE, Zimmerman MA, Morrel-Samuels S, Hudson D. Adolescent violence: Risk, resilience, and prevention. Adolescent Health: Understanding and preventing risk behaviors John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009:213–232. [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System www.cdc.gov/injury Published 2017. Accessed Mar 10, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Walton M, Epstein-Ngo Q, Carter P, et al. Marijuana use trajectories among drug-using youth presenting to an urban emergency department: violence and social influences. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;173:117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter PM, Walton MA, Roehler DR, et al. Firearm violence among high-risk emergency department youth after an assault injury. Pediatrics 2015;135(5):805– 815. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham RM, Carter PM, Ranney M, et al. Violent reinjury and mortality among youth seeking emergency department care for assault-related injury. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169(1):63 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowhani-Rahbar A, Zatzick D, Wang J, et al. Firearm-related hospitalization and risk for subsequent violent injury, death, or crime perpetration: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162(7):492–500. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker MG, Hall JS, Ursic CM, Jain S, Calhoun D. Caught in the crossfire: the effects of a peer-based intervention program for violently injured youth. J Adolesc Health 2004;34(3):177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Reports https://ucr.fbi.gov/. Published 2016. Accessed Mar 12, 2017.

- 10.Lane J Juvenile Delinquency and Justice Trends in the United States. In: Krohn MD, Lane J, eds. The Handbook of Juvenile Delinquency and Juvenile Justice John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2015:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118513217.ch1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jails Freudenberg N., prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J Urban Health 2001;78(2):214–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corso PS, Mercy JA, Simon TR, Finkelstein EA, Miller TR. Medical costs and productivity losses due to interpersonal and self-directed violence in the United States. Am J Prev Med 2007;32(6):474–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apel RJ, Sweeten GA. The effect of criminal justice involvement in the transition to adulthood U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aalsma MC, Lau KS, Perkins AJ, et al. Mortality of youth offenders along a continuum of justice system involvement. Am J Prev Med 2016;50(3):303–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iguchi MY, Bell J, Ramchand RN, Fain T. How criminal system racial disparities may translate into health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2005;16(4):48–56. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2005.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mollen CJ, Fein JA, Vu TN, Shofer FS, Datner EM. Characterization of nonfatal events and injuries resulting from youth violence in patients presenting to an emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2003;19(6):379–384. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pec.0000101577.65509.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Adolescent Assault Victim Needs. Adolescent assault victim needs: a review of issues and a model protocol. Pediatrics 1996;98(5):991–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng TL, Johnson S, Wright JL, et al. Assault-injured adolescents presenting to the emergency department: causes and circumstances. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13(6):610–616. https://doi.org/10.1197/j.aem.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng TL, Schwarz D, Brenner RA, et al. Adolescent assault injury: risk and protective factors and locations of contact for intervention. Pediatrics 2003;112(4):931–938. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.112.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng TL, Wright JL, Markakis D, Copeland-Linder N, Menvielle E. Randomized trial of a case management program for assault-injured youth. Pediatr Emerg Care 2008;24(3):130–136. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181666f72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents. JAMA 2010;304(5):527 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper C, Eslinger DM, Stolley PD. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. J Trauma 2006;61(3):534–540. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000236576.81860.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibru D, Zahnd E, Becker M, Bekaert N, Calhoun D, Victorino GP. Benefits of a hospital-based peer intervention program for violently injured youth. J Am Coll Surg 2007;205(5):684–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zun LS, Downey L, Rosen J. The effectiveness of an ED-based violence prevention program. Am J Emerg Med 2006;24(1):8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jolliffe D, Farrington DP, Loeber R, Pardini D. Protective factors for violence: results from the Pittsburgh Youth Study. J Crim Justice 2016;45:32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.02.007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahonen L, Loeber R, Pardini D. The prediction of young homicide and violent offenders. Justice Q 2016;33(7):1265–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2015.1081263. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loeber R, Wei E, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Huizanga D, Thornberry TP. Behavioral antecedents to serious and violent offending: Joint analyses from the Denver Youth Survey, Pittsburgh Youth Study and the Rochester Youth Development Study. Studies on Crime & Crime Prevention 1999;8(2):245–263. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivara FP, Shepherd JP, Farrington DP, Richmond P, Cannon P. Victim as offender in youth violence. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26(5):609–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moscovitz H, Degutis L, Bruno GR, Schriver J. Emergency department patients with assault injuries: previous injury and assault convictions. Ann Emerg Med 1997;29(6):770–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(97)70199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shepherd J Violence: the relation between seriousness of injury and outcome in the criminal justice system. J Accid Emerg Med 1997;14(4):204–208. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.14.4.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Claassen CA, Larkin GL, Hodges G, Field C. Criminal correlates of injury-related emergency department recidivism. J Emerg Med 2007;32(2):141–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frank JW, Linder JA, Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Wang EA. Increased hospital and emergency department utilization by individuals with recent criminal justice involvement: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29(9):1226–1233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2877-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunningham RM, Ranney M, Newton M, Woodhull W, Zimmerman M, Walton MA. Characteristics of youth seeking emergency care for assault injuries. Pediatrics 2014;133(1):e96–e105. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jessor R Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health 1991;12(8):597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(91)90007-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP. Developmental associations between substance use and violence. Dev Psychopathol 1999;11(4):785– 803. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579499002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldstein PJ. The drugs/violence nexus: a tripartite conceptual framework. J Drug Issues 1985;15(4):493–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204268501500406. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walton MA, Epstein-Ngo Q, Carter PM, et al. Marijuana use trajectories among drug-using youth presenting to an urban emergency department: violence and social influences. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;173:117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bohnert KM, Walton MA, Ranney M, et al. Understanding the service needs of assault-injured, drug-using youth presenting for care in an urban emergency department. Addict Behav 2015;41:97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carter PM, Walton MA, Newton MF, et al. Firearm possession among adolescents presenting to an urban ED for assault. Pediatrics 2013;132(2):213–221. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.U.S. Census Bureau. Quick Facts www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/26290000,00 Published 2010. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- 41.Resko SM, Reddock EC, Ranney ML, et al. Reasons for fighting among violent female adolescents: a qualitative investigation from an urban, midwestern community. Soc Work Public Health 2016;31(3):99–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2015.1087914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Roahen Harrison S, et al. Past-year intentional and unintentional injury among teens treated in an inner-city emergency department. J Emerg Med 2011;41(4):418–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ranney ML, Whiteside L, Walton MA, Chermack ST, Zimmerman MA, Cunningham RM. Sex differences in characteristics of adolescents presenting to the emergency department with acute assault-related injury. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18(10):1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Federal Bureau of Investigation. Annual Uniform Crime Report, 2014. Crime in the United States https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.s−2014 Accessed July 11, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michigan State Police. Michigan Law Enforcement Information Network (LEIN) www.michigan.gov/msp/0,4643,7-123-3493_72291---,00.html Accessed June 5, 2016.

- 46.Sieving RE, Beuhring T, Resnick MD, et al. Development of adolescent self-report measures from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Adolesc Health 2001;28(1):73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Handelsman L, Stein JA, Grella CE. Contrasting predictors of readiness for substance abuse treatment in adults and adolescents: a latent variable analysis of DATOS and DATOS-A participants. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;80(1):63–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Add Health The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth Accessed June 5, 2016.

- 49.Ramirez-Valles J, Zimmerman MA, Newcomb MD. Sexual risk behavior among youth: modeling the influence of prosocial activities and socioeconomic factors. J Health Soc Behav 1998;39(3):237–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richters J, Saltzman W. Survey of exposure to community violence: self report version Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richters JE, Martinez P. Things I have seen and heard: A structured interview for assessing young children’s violence exposure Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Rohsenow DJ, Spirito A, Monti PM. Screening adolescents for problem drinking: performance of brief screens against DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses. J Stud Alcohol 2000;61(4):579–587. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2000.61.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction 2008;103(6):1039– 1047. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA-Modified ASSIST—Prescreen V1.0 2009; www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed/screening/nmassist.pdf Accessed June 5, 2016.

- 55.Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, et al. Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71(3):313–326. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petitclerc A, Gatti U, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE. Effects of juvenile court exposure on crime in young adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 2013;54(3):291–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiebe DJ, Blackstone MM, Mollen CJ, Culyba AJ, Fein JA. Self-reported violence-related outcomes for adolescents within eight weeks of emergency department treatment for assault injury. J Adolesc Health 2011;49(4):440–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Copeland-Linder N, Johnson SB, Haynie DL, Chung SE, Cheng TL. Retaliatory attitudes and violent behaviors among assault-injured youth. J Adolesc Health 2012;50(3):215–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rich JA, Stone DA. The experience of violent injury for young African-American men: the meaning of being a ―sucker‖. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11(2):77–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02599582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carter PM. Antecedents to firearm violence among high-risk emergency department youth: an event-level analysis Society for Academic Emergency Medicine [SAEM]; 2015; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng TL, Haynie D, Brenner R, Wright JL, Chung SE, Simons-Morton B. Effectiveness of a mentor-implemented, violence prevention intervention for assault-injured youths presenting to the emergency department: results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2008;122(5):938–946. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Vos E, Stone DA, Goetz MA, Dahlberg LL. Evaluation of a hospital-based youth violence intervention. Am J Prev Med 1996;12(5 suppl):101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30242-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dicker R Violence prevention for trauma centers: A feasible start [Poster 2901]. Paper presented at: Injury and Violence In America; May 11, 2005; Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fein JA, Mollen CJ, Greene MB. The assault-injured youth and the emergency medical system: what can we do? Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 2013;14(1):47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpem.2013.01.004. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karraker N, Cunningham RM, Becker MG, Fein JA, Knox LM. Violence is Preventable: A Best Practices Guide for Launching & Sustaining a Hospital-based Program to Break the Cycle of Violence. Youth ALIVE!; 2011.

- 66.Zun LS, Downey LV, Rosen J. Violence prevention in the ED: linkage of the ED to a social service agency. Am J Emerg Med 2003;21(6):454–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-6757(03)00102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Goldstein A, et al. Three-month follow-up of brief computerized and therapist interventions for alcohol and violence among teens. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16(11):1193–1207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304(5):527–535. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cunningham RM, Chermack ST, Ehrlich PF, et al. Alcohol interventions among underage drinkers in the ED: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2015;136(4):e783–e793. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zatzick D, Russo J, Lord SP, et al. Collaborative care intervention targeting violence risk behaviors, substance use, and posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms in injured adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168(6):532–539. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(12):2027–2032. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu P, Hoven CW, Tiet Q, Kovalenko P, Wicks J. Factors associated with adolescent utilization of alcohol treatment services. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2002;28(2):353– 369. https://doi.org/10.1081/ADA-120002978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heflinger CA, Chatman J, Saunders RC. Racial and gender differences in utilization of Medicaid substance abuse services among adolescents. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57(4):504–511. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2006.57.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brimblecombe N, Knapp M, Murguia S, et al. The role of youth mental health services in the treatment of young people with serious mental illness: 2‐ year outcomes and economic implications. Early Interv Psychiatry 2017;11(5):393–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. AJS 1989;94(4):774–802. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heinze JE, Reischl TM, Bai M, et al. A comprehensive prevention approach to reducing assault offenses and assault injuries among youth. Prev Sci 2016;17(2):167–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0616-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Garvin EC, Cannuscio CC, Branas CC. Greening vacant lots to reduce violent crime: a randomised controlled trial. Inj Prev 2013;19(3):198–203. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Goldstein AL, et al. Rates and correlates of violent behaviors among adolescents treated in an urban emergency department. J Adolesc Health 2009;45(1):77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Chermack ST, Maio R, Blow FC, Weber J. Correlates of violence history among injured patients in an urban emergency department. J Addict Dis 2007;26(3):61–75. https://doi.org/10.1300/J069v26n03_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. The self-report method of measuring delinquency and crime. In: Duffee D, ed. Measurement and Analysis of Crime and Justice: Criminal Justice 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2000:33–83. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Buchan BJ, Dennis ML, Tims FM, Diamond GS. Cannabis use: consistency and validity of self-report, on-site urine testing and laboratory testing. Addiction 2002;97(suppl 1):98–108. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health 2003;33(6):436–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science 1998;280(5365):867–873. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Webb PM, Zimet GD, Fortenberry JD, Blythe MJ. Comparability of a computer-assisted versus written method for collecting health behavior information from adolescent patients. J Adolesc Health 1999;24(6):383–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Harrison LD, Martin SS, Enev T, Harrington D. Comparing drug testing and self-report of drug use among youths and young adults in the general population Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies;2007. HHS Publication No. SMA 07–4249, Methodology Series M-7. [Google Scholar]