Abstract

Purpose/Aim:

The aim of this pilot study was to evaluate feasibility and gather initial data for a definitive study to test the clinical and microbiological effectiveness of a nursing facility (NF) customized oral hygiene protocol, intended to be delivered by dental hygienists and NF personnel.

Materials and Methods:

A convenience sample of 8 Eastern Iowa NFs were recruited, and each NF was assigned to one of three intervention groups: 1) control (current oral hygiene practice), 2) educational program only, and 3) educational program plus 1% chlorhexidine varnish monthly application. Demographic information, systemic health data, patient centered data, oral health data, and microbiology samples were collected at baseline and after six months.

Results:

Recruitment response rates were 21% for NFs and 23% for residents. A total of 81 residents were examined at baseline and of those, 49 were examined at 6-month (39.5% attrition). There were no statistically or clinically significant differences among the intervention groups at 6 months for any of the recorded clinical or microbiological outcomes.

Conclusions:

Recruitment and retention posed a significant challenge to this trial, even with a relatively short observation period. Results from this pilot study did not encourage further investigation of this customized oral hygiene protocol.

Keywords: Aged, Geriatric Dentistry, Nursing Homes, Frail Elderly

Introduction

The U.S. elderly population increased by 15% from 2005–10 (from almost 35 million to more than 40 million),1 and is projected to be around 71 million in 2030,2 as baby boomers reach the age of 65 years or more. In Iowa, the elderly represented 15.8% of the population in 2014, and this group is expected to increase to 20% by 2050.3

As the elderly population grows, greater numbers of older adults are expected to live in nursing facilities (NF). Over a 23-year period, the U.S. has seen a 30% increase in the number of older Americans living in NFs 4 and a substantial portion of this population was covered under Medicare and/or Medicaid.5 In Iowa, there were 442 NF with 25,121 residents in 20116, a group representing about 5.5% of the Iowa elderly population.

There is increasing evidence that oral health plays an important role in elderly NF residents’ general health7–9 and life satisfaction.10 Improving oral health seems to improve patients nutrition,8, 9 social interaction,11 and reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia, 12–16 , possibly because dental (or denture) plaque can harbor large quantities of opportunistic pulmonary pathogens.17-19 This is of great importance, as aspiration pneumonia is a leading cause of death in elderly NF residents.12

Though oral health care is recognized as an important part of general care for NF residents, it is frequently neglected.20, 21 In fact oral hygiene among elderly NF residents is often poor worldwide.22–25 In Iowa, only 51% of NF residents received any dental procedure in a given year26, and only 36.2% received a preventive dental procedure within 2 years after entering a NF27. It is likely that patient-related factors (e.g., general health problems28, polypharmacy29, dependence on caregivers24 who might be overburdened and have poor formal training30, 31) and other important variables32 (e.g., financial and dentist-reported constraints33, 34) could be responsible for the relatively low number of oral health services provided through formal contracts with NF.35 However, the establishment of daily oral health care routines by the caregivers at NF may help improve their residents’ oral health.

Implementation of oral health care protocols provided by NF caregivers has shown positive results with respect to oral hygiene outcomes when compared to control groups in some36–39 but not all40-42 studies. This discrepancy may be explained by the studies methodologies and by different barriers related to the caregivers, residents and institution.43 Many approaches have been suggested to overcome these barriers,42, 44–46 and nurses’ knowledge seems to be an important component in explaining variations in oral health hygiene practices in NF.47 Self–efficacy, facilitation of behavior48 and constant evaluation49 also seem to play an important role in good oral hygiene practices in NF.

Considering the importance of developing and establishing effective oral hygiene protocols in Iowa NF, plus the various barriers that preclude dentists’ participation in the establishment of such protocols,33, 34 the overall aim of this pilot study was to develop initial protocols, evaluate feasibility, and gather initial data for a definitive study to test the clinical and microbiological effectiveness of a NF-customized oral hygiene protocol for use in Iowa NFs, intended to be delivered primarily by dental hygienists and NF personnel. Our hypothesis was that the oral hygiene protocol groups would present significantly better key oral health and microbiological outcomes when compared to the control group.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a pilot study for a possible subsequent cluster randomized trial.50–52 For the purposes of this pilot study, which was a stratified cluster randomized trial with NF as the cluster unit, a convenience sample of NFs within a 75-minute drive from Iowa City was used. None of the NFs were served by the University of Iowa College of Dentistry Geriatric Mobile Unit (GMU), as being NFs served by the GMU would introduce bias when compared to other NFs. That is because the GMU provides comprehensive dental care and a recall schedule for cleanings to the residents at the served NFs, and we assumed this may not represent what happens in the majority of Iowa NFs.

Considering this trial had three intervention arms (described below), an initial sample size was calculated to be approximately 140 residents in each of the three treatment groups. In the absence of a priori estimates of variability, we could only speak generally regarding detectable effect sizes. For quantitative outcomes (e.g., DMFS or caries increment, plaque scores, oral health and quality of life scores), we would be able to detect, with 80% power, mean differences between a pair of treatment groups on the order of 0.39 standard deviations or more (based on a Type I error level of 0.05/3 to adjust for three pairwise treatment comparisons in the context of one-way ANOVA) for quantitative measures in NF residents.

Thirty-seven NFs were contacted and agreed to be visited for receiving a more detailed explanation about the study, but only eight NFs agreed to participate (21% NF response rate). Because the numbers of enrolled participants varied across the participating NF, we proceeded with a stratified randomization, in which the NF was assigned to receive one of the three interventions in a blinded fashion such that the number of participants in each intervention arm was as similar as possible. Within each NF, all participants received the same intervention. Interventions were a) Group A- the control group (current oral hygiene practice), b) Group B - educational program only, and c) Group C - educational program plus 1% chlorhexidine varnish monthly application.

Group A participants were enrolled, received no educational program, kept current practices and were followed for the study period. Group B (educational program only) consisted of a one-hour DH-delivered interview with a sample of caregivers at each NF, then a one-hour tailored lecture aiming to address the specific issues raised by the caregivers from each NF (e.g., working with combative residents, how to perform oral hygiene in a time-efficient manner) and hands-on training, followed by the DH visits to the NF every other week. At dental hygienist visits, oral hygiene instructions were reinforced and the DH brushed patients’ teeth. For Group C, Chlorhexidine varnish (FDA approved chemical adjuvant (1% chlorhexidine varnish 1% thymol – Cervitec Plus, Ivoclar Vivadent) 38, 53-56 was applied monthly by the DH to all available natural tooth surfaces. Chlorhexidine varnish was selected over fluoride varnish or silver nitrate since it also might help to reduce microbial burden, thereby improving periodontal health along with protecting against caries55, 56, which is desirable for the elderly population.

The study was approved by the University of Iowa’s Institutional Review Board (IRB ID#201403778) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02668809), and this report was prepared in accordance with the CONSORT 2010 Statement (www.consort-statement.org).

Participants

The total number of residents in the eight participating NFs when recruitment started (January 2015) was 352. All residents were invited to participate and there were no exclusion criteria. As many of the residents had an established legal guardian, the legal guardians were then contacted. One-hundred and forty one (40%) responded to the invitation, and 81 accepted (23% resident response rate).

Data collection

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at University of Iowa. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing an intuitive interface for validated data entry; audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and procedures for importing data from external sources.57

Baseline data included information regarding 1) NF (NF name, number of residents), 2) participants’ demographics (age, sex, race, source of payment for the NF), 3) participants’ systemic health (BMI, episodes of x-ray documented pneumonia and number of febrile days in the last six months, existing medical conditions, and medications taken), 4) mini-cog test (Mini-Cog),58 5) mini nutritional assessment short form (Mini-Nutri),59 6) Rand 36-item short form health survey instrument version 1.0 (SF-36),60 7) oral health impact profile 14-question (OHIP-14),61 8) geriatric oral health assessment index (GOHAI),62 and 9) participants oral health (oral lesions, denture status, number of teeth, dental plaque index, denture plaque index, bleeding on brushing, gingival bleeding index, coronal DMFS, root DMFS, and self-reported dry mouth).

Nursing facilities, participants’ demographics and systemic health data were obtained from participants’ records. The questionnaires (Mini-Nutri, SF-36, OHIP-14, and GOHAI) were answered by non-cognitively impaired participants (participants without a written dementia diagnosis and screened as non-cognitively impaired by the Mini-Cog) during interviews.

All participants received an oral exam, performed in a designated private room or in the participants’ bed, by a single examiner with the help of a dental assistant recorder, using a self-lighting dental mirror and an explorer. At dental hygiene visits (a total of 12 for participants in the intervention groups), dental plaque index, denture plaque index, bleeding on brushing, and gingival bleeding index were recorded. After six months, a final set of data was collected, which included the same variables collected at baseline, except for NF data and participants’ demographics data. Examiners, interviewers and statisticians were blinded to the NF groups allocation.

Microbiology sampling and analysis

Microbiological samples were obtained at baseline, at 2-, 4-, and 6-month. For non-denture wearers, a single microbiological sample was collected from each participant at each time point by swabbing all smooth surfaces of the teeth and the oral mucosa and tongue with a sterile cotton swab.

The cotton part of the swabs was cracked from the handle and placed into individual tubes containing TSB-YE (Tryptic Soy Broth-Yeast Extract) (Difco®, Sparks, MD, USA) with 10% glycerol. Collection tubes were kept in a proper container, and the container was stored in ice in a biohazard labeled cooler until transport to the lab for processing.

Swab samples were vortexed for 3 minutes and then placed in a sonicating water bath for 1 minute to provide homogeneous suspensions of plaque bacteria. The resulting suspensions were diluted and plated using an Autoplate® Spiral Plating System (Advanced Instruments, Inc., Norwood, MA, USA) on selective/differential media for isolation and enumeration of our target species (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Actinomyces viscosus, Actinomyces actinomycetemcomitans, and Candida albicans), or blood agar for all aerobic bacteria counting. Plates were incubated in a Coy Chamber at 37oC for the anaerobes and aerobically at 37oC for the facultative anaerobes and aerobes. Plates were counted following standard incubation times for each group of organisms and numbers of viable bacteria per swab were determined following sector counting and analysis following standard spiral plating methodology.

Data Analysis

Data collected at baseline were tested for group differences using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an exchangeable correlation matrix to account for cluster allocation to NF. GEE using the normal distribution was used to model age. GEE with the logistic distribution was used to model sex, private pay status, febrile days status, dementia status, self-reported dry mouth, denture status upper arch, denture status lower arch, upper denture plaque index status, lower denture plaque index status, bleeding on brushing. GEE with the negative binomial distribution was used to model number of comorbid conditions, number of medications, number of oral lesions, and number of teeth. GEE using the normal distribution after a rank transformation was used to model BMI, dental plaque index, coronal DMFS, coronal DFS, root DMFS, root DFS, DFT, DMFS, total CFU count, Porphyromonas gingivalis counts, Fusobacterium nucleatum counts, Actinomyces viscosus counts, A. actinomycetemcomitans counts, and Candida albicans counts.

Group comparisons of microbial counts at 2-, 4-, and 6-month were modeled using GEE with the normal distribution after a rank transformation. We note that attrition was high and the assumption of data missing completely at random may be violated for these analyses.

All analyses were conducted at the 5% level of significance using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). No adjustments were attempted for multiple testing.

Results

In an attempt to avoid repeating the same information in the text and tables, this Results Section was structured to present all baseline data for the entire sample described in the written text; and all the comparisons among groups, for both baseline and 6-month, in the tables.

Participant recruitment, drop-offs and demographics

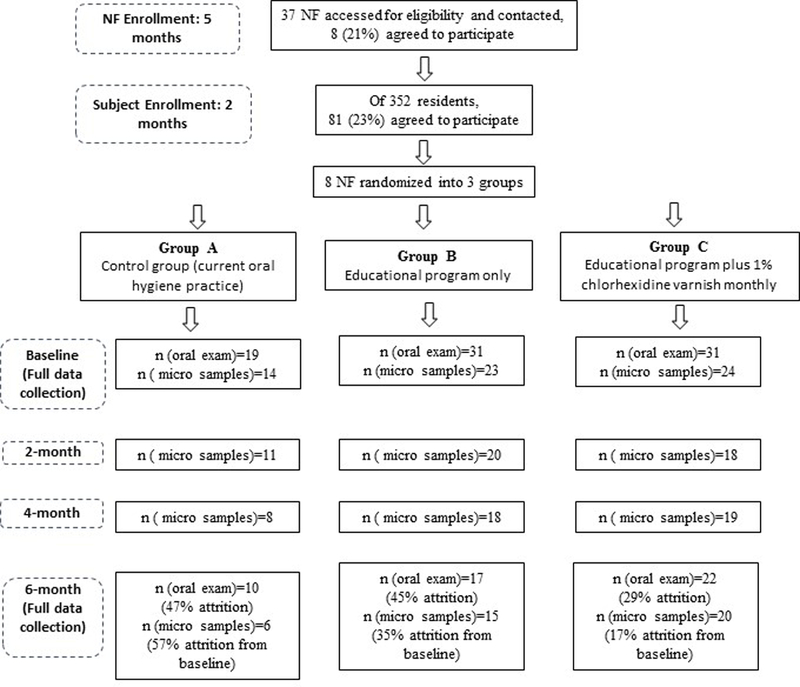

Figure 1 summarizes the study design and flow, showing study procedures, data collection points, and participant flow. Participants were lost to follow-up due to three reasons, all very common to the NF environment: participant was not feeling well/refused to be seen at the day of data collection, participant was transferred to another NF, or participant was deceased.

Figure 1.

INFOH Study flow diagram.

At baseline, there were 49 women with a mean age of 83.7 (± 12.0) and 32 men with a mean age of 79.8 (± 14.2). Women ranged in age from 30 to 99 and men ranged in age from 32 to 98. There was no difference in age by sex (p>0.05). All participants were white. The most common type of NF payment was Private Pay, with 37 residents (22F, 15M) in that category. The next most common was Medicaid (Title XIX) with 21 residents (12F, 9M). Only 49 participants completed the final exam (39.5% drop off rate). Table 1 shows participants’ demographic data by each group at baseline.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline data for all participants and all variables, per group.

| n | Group A | n | Group B | n | Group C | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19 | 79.42 (13.75) | 31 | 81.23 (16.31) | 31 | 84.71 (7.51) | 0.3794 |

| % Female | 19 | 63.16 | 31 | 61.29 | 31 | 58.06 | 0.6255 |

| Source of payment | |||||||

| Medicare | 3 | 1 | 7 | NT | |||

| Medicaid | 8 | 9 | 4 | NT | |||

| Private insurance | 1 | 1 | 3 | NT | |||

| Private Pay | 7 | 20 | 10 | 0.1009 | |||

| Other | 0 | 0 | 7 | NT | |||

| BMI | 19 | 29.77 (10.65) | 29 | 27.03 (5.93) | 26 | 27.12 (5.90) | 0.7442 |

| Episodes of x-ray documented pneumonia |

19 | 0.32 (0.75) | 29 | 0.03 (0.19) | 29 | 0 (0) | NT |

| Any febrile days % | 19 | 26.32% | 29 | 31.03% | 27 | 29.63% | 0.9117 |

| % with dementia | 19 | 73.68% | 31 | 64.52% | 31 | 83.87% | 0.3594 |

| Number of comorbid conditions |

19 | 10.47 (6.41) | 31 | 10.16 (5.44) | 31 | 9.06 (4.57) | 0.6472 |

| Number of medications | 19 | 12.74 (4.86) | 31 | 13.71 (4.90) | 31 | 10.58 (5.81) | 0.3692 |

| Self-reported dry mouth | 19 | 26.32% | 31 | 29.03% | 31 | 38.71% | 0.9046 |

| Number of oral lesions | 19 | 0.42 (0.61) | 31 | 0.26 (0.51) | 31 | 0.23 (0.50) | 0.3249 |

| Upper arch-no denture | 18 | 50.00% | 31 | 61.29% | 31 | 54.84% | 0.4968 |

| Lower arch-no denture | 18 | 61.11% | 31 | 77.42% | 31 | 67.74% | 0.3865 |

| Number of teeth | 19 | 14.37 (10.88) | 31 | 13.87 (11.02) | 31 | 15.16 (10.07) | 0.9023 |

| Dental plaque index | 14 | 79.92 (31.16) | 26 | 61.51 (35.64) | 28 | 80.34 (33.60) | 0.3561 |

| Upper denture plaque index (% “Poor” score) |

9 | 44.44% | 11 | 36.36% | 14 | 64.29% | 0.3377 |

| Lower denture plaque index (% “Poor” score) |

6 | 50.00% | 7 | 42.86% | 9 | 88.89% | 0.1518 |

| Bleeding on brushing on multiple sites |

14 | 42.86% | 22 | 77.27% | 26 | 65.38% | 0.2782 |

| Gingival bleeding index | 14 | 0.08 (0.12) | 26 | 0.05 (0.14) | 28 | 0.05 (0.11) | 0.5240 |

| Coronal DMFS | 19 | 111.42 (41.23) | 31 | 110.81 (44.55) | 31 | 110.42 (37.20) | 0.9687 |

| Coronal DFS | 19 | 22.47 (23.56) | 31 | 19.19 (23.45) | 31 | 24.61 (21.88) | 0.5258 |

| Root DMFS | 19 | 71.52 (42.77) | 31 | 75.29 (44.23) | 31 | 70.13 (38.85) | 0.9736 |

| Root DFS | 19 | 0.58 (1.61) | 31 | 2.00 (4.08) | 31 | 1.48 (2.54) | 0.2221 |

| DFT | 19 | 7.26 (6.21) | 31 | 6.23 (6.50) | 31 | 8.03 (6.74) | 0.4259 |

| DMFT | 19 | 25.05 (6.35) | 31 | 24.55 (7.95) | 31 | 25.19 (6.50) | 0.9507 |

| Total CFU count | 14 | 7.10 (0.43) | 23 | 7.07 (0.53) | 24 | 7.25 (0.58) | 0.5632 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | 14 | 3.76 (1.50) | 23 | 3.12 (2.04) | 24 | 4.44 (1.85) | 0.0960 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | 14 | 6.07 (0.72) | 23 | 5.85 (0.69) | 24 | 6.09 (0.90) | 0.2898 |

| Actinomyces viscosus | 14 | 6.34 (0.61) | 23 | 6.01 (0.80) | 24 | 6.18 (0.92) | 0.2860 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | 14 | 6.21 (0.58) | 23 | 5.28 (1.56) | 24 | 6.10 (1.02) | 0.2077 |

| Candida albicans | 14 | 2.67 (1.88) | 23 | 2.22 (1.96) | 24 | 2.43 (1.93) | 0.7326 |

P-value = comparison among the three groups; NT= Not tested

Systemic health

At baseline, average BMI was 27.8 (± 7.4), 93.5% had no episodes of documented pneumonia in the last six months, and 70.7% had no episodes of febrile days in the last six months. The mean number of comorbidities per participants was 9.8 (± 5.3), and the most common comorbidities were essential (primary) hypertension (72.8%), depressive episode (44.4%), gastro-esophageal reflux disease (34.6%), constipation (32.1%), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (25.9%). The mean number of daily medications per participant was 12.3 (± 5.4), and the most common medications were acetaminophen (85.2%), acetylsalicylic acid (45.7%), magnesium hydroxide (45.7%), polyethylene glycol (43.2%), docusate , furosemide and omeprazole (27.2%). Through the use of the medical record information and the mini-cog exam, a total of 60 participants (74.1%) were identified as having cognitive impairment. Table 1 shows participants’ systemic health data by each group at baseline, and Table 2 shows participants’ systemic health data at 6-month exam.

Table 2.

Systemic health data at 6-month exam.

| Group A | Group B | Group C | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (n) | 10 | 17 | 22 | |

| BMI | 27.16 (6.31) | 25.78 (4.20) | 25.83 (6.37) | 0.8453 |

| Episodes of x-ray documented pneumonia (last six months) |

0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NT |

| Any febrile days % | 26.32% | 31.03% | 29.63% | 0.9117 |

| % with dementia | 0.0% | 29.41% | 9.09% | NT |

| Number of comorbid conditions | 11.30 (6.50) | 10.00 (3.92) | 9.41 (5.47) | 0.4563 |

| Number of medications | 11.50 (6.06) | 13.47 (4.42) | 9.59 (5.09) | 0.2035 |

P-value = comparison among the three groups; NT = Not tested

Patient centered outcomes

At baseline, 13 participants answered the mini nutritional assessment short form (Mini-Nutri)59, and the mean score was 12.00 (± 1.83). At 6-month 3 participants answered the same questionnaire, and the mean score was 10.67 (± 3.21). Considering the modest sample sizes in each group for the patient centered outcomes, the results for each group were deemed irrelevant as it was not possible to test for differences among the groups, and thus are not reported here.

As for the Rand 36-item short form health survey instrument version 1.0 (SF-36)60, 10 participants (3F, 7M) agreed to respond at baseline and the mean score for physical functioning was 7.5 (± 13.8), for role limitations due to physical health was 20.0 (±30.7), for role limitations due to emotional problems (n=9) was 74.1 (± 40.1), for energy/fatigue was 42.5 (± 22.4), for emotional well-being (n=9) was 80.9 (± 15.5), for social functioning was 62.5 (± 36.3), for pain was 55.2 (± 34.3), and for general health 49.0 (± 27.3). At 6-month, only 4 participants (1F, 3M) agreed to answer the SF-36 and the mean score for physical functioning was 16.2 (± 17.0), for role limitations due to physical health was 43.7 (± 51.5), for role limitations due to emotional problems was 25.0 (± 31.9), for energy/fatigue was 25.0 (± 22.7), for emotional well-being was 73.0 (± 11.5), for social functioning was 56.2 (± 16.1), for pain was 70.0 (± 16.2), and for general health 45.0 (± 24.8).

Regarding the oral health impact profile 14-question (OHIP-14)61, 10 participants agreed to respond at baseline, and the mean score was 2.1 (± 3.6), ranging from 0 to 10.8. At 6-month, only four participants responded, and the mean was 0.6 (± 1.3), ranging from 0 to 2.6.

As for the geriatric oral health assessment index (GOHAI)62, 10, participants agreed to respond at baseline, and the mean score was 28.9 (± 3.7), ranging from 21 to 34. At 6-month, only four participants responded, and the mean was 29.7 (± 3.6), ranging from 25 to 33.

Oral health

At baseline, 54.3% of the participants were dentate without dentures, 23.5% were dentate wearing dentures, 21.0% were complete denture wearers and only 1.2% were edentulous without dentures. Xerostomia was reported by 32.1% of the participants at baseline. A total of 20 participants (24.7%) presented with oral lesions. The four types of oral lesions identified were denture stomatitis (16), ulceration (3), candidiasis (2), and epulis fissuratum (2). Lesions were located on the hard and or soft palate (15), alveolar ridge or gingiva (12), commissures (1), the sulci (1), and the floor of the mouth (1). The average number of teeth at baseline was 14.5 (± 10.5) with a range of 0 to 29. Coronal DMFS mean was 110.8 (± 40.6), with a range of 20 to 160. Root DMFS mean was 90.2 (± 51.8) with a range of 17 to 128. The dental plaque index mean was 73.0 (± 34.6) with a range of 0 to 100. Gingival bleeding index mean was 0.06 (SD=0.12) with a range of 0 to 0.58.

Table 1 shows participants’ oral health data by each group at baseline, and Table 3 shows participants’ oral health data at the 6-month exam. There was no difference among the groups for the variables thought to be most sensitive to the interventions, i.e., dental plaque index (p=0.5750), and gingival bleeding index (p=0.3990).

Table 3.

Oral health data at 6-month exam.

| N | Group A | N | Group B | N | Group C | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported dry mouth | 10 | 60.00% | 17 | 29.41% | 22 | 36.36% | 0.9046 |

| Number of oral lesions | 10 | 0.10 (0.32) | 17 | 0.12 (0.33) | 22 | 0.18 (0.50) | 0.8817 |

| Upper arch-no denture | 10 | 50.00% | 16 | 81.25% | 22 | 63.64% | 0.1319 |

| Lower arch-no denture | 10 | 60.00% | 16 | 100.00% | 22 | 72.73% | NT |

| Number of teeth | 10 | 14.20 (12.59) | 17 | 16.35 (10.18) | 22 | 17.18 (8.64) | 0.4773 |

| Dental plaque index | 6 | 39.26 (34.88) | 14 | 45.69 (31.73) | 16 | 62.37 (35.79) | 0.1709 |

| Upper denture plaque index (% “Poor” score) |

2 | 50.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 3 | 33.33% | NT |

| Lower denture plaque index (% “Poor” score) |

1 | 100.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 33.33% | NT |

| Bleeding on brushing on multiple sites |

6 | 50.00% | 14 | 42.85% | 17 | 64.7% | 0.2233 |

| Gingival bleeding index | 6 | 4.90 (3.94) | 17 | 3.84 (7.39) | 20 | 3.16 (11.25) | 0.7978 |

| Coronal DMFS | 10 | 116.30 (42.29) | 17 | 97.06 (47.20) | 22 | 108.68 (34.55) | 0.6945 |

| Coronal DFS | 10 | 25.80 (25.63) | 17 | 17.94 (21.71) | 22 | 32.55 (21.80) | 0.3274 |

| Root DMFS | 10 | 72.40 (49.76) | 17 | 74.65 (57.79) | 22 | 64.68 (34.25) | 0.7122 |

| Root DFS | 10 | 0 (0) | 17 | 11.35 (23.95) | 22 | 3.77 (4.59) | 0.2285 |

| DFT | 10 | 7.90 (7.20) | 17 | 8.35 (6.96) | 22 | 10.36 (6.47) | 0.5642 |

| DMFT | 10 | 26.00 (5.79) | 17 | 22.53 (10.03) | 22 | 25.18 (5.79) | 0.7758 |

P-value = comparison among the three intervention groups (Groups 1, 2 and 3)

NT = Not tested

Microbiology

Table 1 shows participants’ microbiological data by each group at baseline, and Table 4 shows participants’ microbiological data at 2-, 4-and 6-month. There were no differences among the groups for any of the microbiological outcomes, at any observation period.

Table 4.

Log10 cell counts for dentate participants at 2-month, 4-month, and 6-month.

| Group A | Group B | Group C | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-month | Participants (n) | 11 | 20 | 18 | |

| Total CFU count for aerobic | 7.13 (0.30) | 6.47 (1.65) | 6.87 (0.69) | 0.2666 | |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | 4.99 (1.42) | 3.46 (2.12) | 4.99 (0.93) | 0.0971 | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | 5.83 (0.62) | 5.78 (1.05) | 5.92 (0.72) | 0.3587 | |

| Actinomyces viscosus | 5.73 (0.68) | 5.37 (1.27) | 5.11 (0.75) | 0.1304 | |

| Actinomyces actinomycetemcomitans | 5.66 (0.85) | 5.28 (1.54) | 5.75 (0.89) | 0.5051 | |

| Candida albicans | 2.38 (1.72) | 2.15 (2.01) | 2.43 (2.06) | 0.7780 | |

| 4-month | Participants (n) | 8 | 18 | 19 | |

| Total CFU count for aerobic | 7.15 (0.40) | 6.92 (0.77) | 6.97 (0.65) | 0.9248 | |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | 5.57 (0.66) | 5.16 (1.34) | 4.74 (1.18) | 0.3144 | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | 5.53 (1.39) | 5.72 (1.11) | 6.04 (0.65) | 0.2972 | |

| Actinomyces viscosus | 5.38 (0.42) | 5.26 (0.94) | 5.54 (0.90) | 0.4555 | |

| Actinomyces actinomycetemcomitans | 5.89 (0.38) | 5.96 (0.66) | 5.92 (1.06) | 0.3226 | |

| Candida albicans | 2.96 (1.94) | 2.12 (1.99) | 2.29 (1.90) | 0.3663 | |

| 6-month | Participants (n) | 6 | 15 | 20 | |

| Total CFU count for aerobic | 6.69 (0.68) | 7.00 (0.83) | 7.06 (0.58) | 0.5407 | |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | 5.12 (1.35) | 5.09 (1.71) | 5.07 (1.64) | 0.4229 | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | 5.34 (1.58) | 6.00 (0.81) | 6.08 (0.63) | 0.3778 | |

| Actinomyces viscosus | 4.97 (0.67) | 5.01 (1.26) | 5.38 (0.97) | 0.4686 | |

| Actinomyces actinomycetemcomitans | 5.70 (0.83) | 5.65 (1.06) | 5.85 (0.93) | 0.3780 | |

| Candida albicans | 1.80 (1.56) | 2.05 (2.14) | 2.43 (1.93) | 0.7515 |

P-value = comparison among the three groups

Discussion

Although this pilot was able to develop initial protocols and assess the feasibility for a larger trial, the initial data gathered was discouraging in the hope of pursuing a future larger trial for this NF-customized oral hygiene program, as no significant differences were observed for the oral health and microbiological outcomes among the control and intervention groups.

However, this pilot provided important lessons. The initial protocols of this pilot, its oral exams and its data collection from participants’ records worked well. There was some difficulty with obtaining the number of febrile days, and weight and height, which were usually not readily available in particpants’ records. However, directors of nursing were able to find it per research team request.

Due to the high frequency of participants with dementia, obtaining adequate patient centered data in reasonable numbers proved very difficult, which should be considered when planning future trials. First, it should be pointed out that there is no tool specifically designed to assess quality of life among cognitively impaired individuals, to our knowledge. The absence of a validated tool makes quality of life assessment even more subjective among this subpopulation. Second, even among participants considered able to respond competently, questionnaire length (particularly SF-36) proved onerous to complete, thus further reducing the number of completed questionnaires. It is also possible that healthier people were more likely to complete the assessments, which could have biased our findings.

Regarding feasibility, the planned initial sample size (n=140 per group) far exceeded the actual enrollment (n=19 for Group A, n=31 for Groups B and C, at baseline). This was due to a reduced response rate from NFs (21%) and also from NF residents (23%). Sloane (2013)31 did not report NF response rates, but reported a much higher residents’ response rate (74%). Many attempts were made to increase our NF response rates, including contacting NF organizations and visiting NFs in person, which proved to be the most successful approach. Contacting NF residents’ guardians to obtain their consent was also very difficult, and many times unsuccessful, as many of them would request “not bothering” their loved ones in spite of our attempts to convince them that the study protocol might be beneficial. As a possible solution for the recruitment issue, future trials should consider hiring and training a research assistant whose main role in recruitment would be contacting NF and powers of attorney, using the arguments we derived as more convincing during this pilot (e.g., highlighting the importance of oral health to prevent infection and pain). It is highly advisable that researchers consider these response rates when planning for future investigations.

Attrition was also an important barrier in achieving the desired final sample size, adding to the challenges posed by the recruitment phase, although less can be done regarding this issue as the main causes for attrition were not within our control (participant was not feeling well/refused to be seen at the day of data collection, participant was transferred to another NF, or participant was deceased). Our attrition rate was comparable to other studies with the same follow-up period.37, 39 Due to low response rates and high attrition rates, this pilot study was underpowered, which negatively impacted our ability to find statistically significant differences.

Regarding gathering initial data, our baseline data confirmed previous findings among institutionalized older adults22–25, 31, 39, as the participants presented with very complex health histories, polypharmacy, and high prevalence of xerostomia and inflammatory lesions of the soft oral tissues (denture stomatitis being the most prevalent lesion). High coronal and root DMFS and DFS suggest complex remaining dentitions, with many fillings and some decay. Bleeding on brushing at multiple sites was also high, which precluded meaningful evaluation of the gingival bleeding index (as GBI was assessed after brushing residents teeth to remove plaque disclosing solution, and not performed if participant was bleeding at multiple sites).The high prevalence of gingivitis and denture stomatitis could be explained by the high dental and denture plaque indices observed in this pilot, which denotes the inefficiency of current oral hygiene routine practices, as reported before24, 31.

The combination of high prevalence of cognitive impairment, multi-morbidity, polypharmacy and inadequate oral health and inefficient oral hygiene routines have been linked to the possible rise of some NF acquired infections, such as aspiration pneumonia12–16. In this context, improving oral hygiene routines is of paramount importance20, 21. Due to reduced sample size and small proportion of participants showing aspiration pneumonia and febrile days, we were not able to test these variables for differences among intervention groups. In addition, our hygiene protocols did not improve oral hygiene outcomes when compared to the control group. Other studies have reported failure to improve oral hygiene outcomes in nursing facilities40–42, and many suggestions on how to obtain better results were presented. There is agreement that a successful program for improving oral hygiene outcomes should address the barriers related to caregivers, residents and nursing facilities, and many approaches have been suggested to overcome these barriers42–47. During the planning phase of our trial, those approaches were incorporated by having previous discussions with the caregivers and incorporating their concerns in the training phase. We submit that a program including a longer training period, allowing for the training of oral health “champions”, associated with more administrative enforcement of new oral hygiene protocols, is necessary to achieve substantial improvement in oral health outcomes.

Besides the limited sample, this study is mainly limited by the fact that compliance level is not equal among NFs which increases the risk of selection bias at cluster level; the inability of some participants to effectively participate in all steps of the research protocol; and because the control NFs also have their residents examined, they might have improved their usual care during the study period (Hawthorne effect).

The strengths of this trial include the blinded examiners, interviewers and statisticians; the randomization scheme, and the variety of patient-based outcomes assessed (systemic health, oral health, and microbiological outcomes).

Further research projects should account for low recruitment and high attrition rates, use simpler, smaller questionnaires for assessing patient centered outcomes, and design interventions that incorporate more hours of oral health training with greater administrative enforcement of the oral hygiene protocols.

Conclusion

Recruitment and retention posed a significant challenge to this randomized clinical trial, even with a relatively short observation period. Results from this pilot study did not encourage further investigation of this customized oral hygiene protocol.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participating nursing facilities; Ms. Heather Stallman, Ms. Mary-Kelly Grief and Ms. Allison Winter for their help during several nursing facility visits; and Ivoclar Vivadent, for providing Cervitec Plus. Research reported in this publication used REDCap, which is supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (#U54TR001356). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We also would like to thank Delta Dental of Iowa Foundation and the University of Iowa College of Dentistry and Dental Clinics for their generous support of this study

References

- 1.US Census Bureau. 2010 Census 3. 2010. [Cited 2013 October 7] http://www.aoa.gov/AoAroot/Aging_Statistics/Census_Population/census2010/docs/Pop_Age_65_Alpha_List.xls.

- 2.US Census Bureau. 2010 Census 2. 2010 [Cited 2013 October 7] http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/future_growth/docs/State-Persons65+age-projections-2005-2030.xls.

- 3.State Data Center of Iowa and The Iowa Department of Aging. Older Iowans: 2016. Iowa; 2016. p. 4.

- 4.Ness J, Ahmed A, Aronow WS. Demographics and payment characteristics of nursing home residents in the United States: a 23-year trend. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:1213–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Health Statistics. Nursing home current residents. 2013 [Cited 2013 October 7] http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nnhsd/estimates/nnhs/estimates_paymentsourcetables.pdf.

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics. Nursing home facilities 2006. 2006 [Cited 2013 October 7] http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nnhsd/nursinghomefacilities2006.pdf.

- 7.Haumschild MS, Haumschild RJ. The importance of oral health in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009;10:667–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Lancker A, Verhaeghe S, Van Hecke A, Vanderwee K, Goossens J, Beeckman D. The association between malnutrition and oral health status in elderly in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:1568–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walls AW, Steele JG. The relationship between oral health and nutrition in older people. Mech Ageing Dev 2004;125:853–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benyamini Y, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Self-rated oral health as an independent predictor of self-rated general health, self-esteem and life satisfaction. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnelly LR, MacEntee MI. Social interactions, body image and oral health among institutionalised frail elders: an unexplored relationship. Gerodontology 2012;29:e28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassim CW, Gibson G, Ward T, Paphides BM, Denucci DJ. Modification of the risk of mortality from pneumonia with oral hygiene care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1601–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quagliarello V, Ginter S, Han L, Van Ness P, Allore H, Tinetti M. Modifiable risk factors for nursing home-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quagliarello V, Juthani-Mehta M, Ginter S, Towle V, Allore H, Tinetti M. Pilot testing of intervention protocols to prevent pneumonia in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1226–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarin J, Balasubramaniam R, Corcoran AM, Laudenbach JM, Stoopler ET. Reducing the risk of aspiration pneumonia among elderly patients in long-term care facilities through oral health interventions. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9:128–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tada A, Miura H. Prevention of aspiration pneumonia (AP) with oral care. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012;55:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campos MS, Marchini L, Bernardes LAS, Paulino LC, Nobrega FG. Biofilm microbial communities of denture stomatitis. Oral Microbiology and Immunology 2008;23:419–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pace CC, McCullough GH. The association between oral microorgansims and aspiration pneumonia in the institutionalized elderly: review and recommendations. Dysphagia 2010;25:307–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awano S, Ansai T, Takata Y, et al. Oral health and mortality risk from pneumonia in the elderly. J Dent Res 2008;87:334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman P Improving oral health care for the frail elderly: a review of widespread problems and best practices. Geriatr Nurs 2002;23:189–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gil-Montoya JA, de Mello AL, Cardenas CB, Lopez IG. Oral health protocol for the dependent institutionalized elderly. Geriatr Nurs 2006;27:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Visschere LM, Grooten L, Theuniers G, Vanobbergen JN. Oral hygiene of elderly people in long-term care institutions--a cross-sectional study. Gerodontology 2006;23:195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsoulis J, Schimmel M, Avrampou M, Stuck AE, Mericske-Stern R. Oral and general health status in patients treated in a dental consultation clinic of a geriatric ward in Bern, Switzerland. Gerodontology 2012;29:e602–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchini L, Vieira PC, Bossan TP, Montenegro FL, Cunha VP. Self-reported oral hygiene habits among institutionalised elderly and their relationship to the condition of oral tissues in Taubaté, Brazil. Gerodontology 2006;23:33–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuluaga DJ, Ferreira J, Montoya JA, Willumsen T. Oral health in institutionalised elderly people in Oslo, Norway and its relationship with dependence and cognitive impairment. Gerodontology 2012;29:e420–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ettinger RL, O’Toole C, Warren J, Levy S, Hand JS. Nursing directors’ perceptions of the dental components of the Minimum Data Set (MDS) in nursing homes. Spec Care Dentist 2000;20:23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly MC, Caplan DJ, Bern-Klug M, et al. Preventive dental care among Medicaid-enrolled senior adults: from community to nursing facility residence. J Public Health Dent 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.de Deco CP, Fernandes do Santos JF, Prisco da Cunha VdP, Marchini L. General health of elderly institutionalised and community-dwelling Brazilians. Gerodontology 2007;24:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchini A, de Deco C, Silva M, Lodi K, da Rocha R, Marchini L. Use of Medicines Among a Brazilian Elderly Sample: A Cross-sectional Study. International Journal of Gerontology 2011;5:94–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barbosa CS, Marchini AM, Marchini L. General and oral health-related quality of life among caregivers of Parkinson’s disease patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013;13:429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Chen X, et al. Effect of a person-centered mouth care intervention on care processes and outcomes in three nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1158–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warren JJ, Kambhu PP, Hand JS. Factors related to acceptance of dental treatment services in a nursing home population. Spec Care Dentist 1994;14:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacEntee MI, Kazanjian A, Kozak JF, Hornby K, Thorne S, Kettratad-Pruksapong M. A scoping review and research synthesis on financing and regulating oral care in long-term care facilities. Gerodontology 2012;29:e41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunez B, Chalmers J, Warren J, Ettinger RL, Qian F. Opinions on the provision of dental care in Iowa nursing homes. Spec Care Dentist 2011;31:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NationalCenterforHealthStatistics. Health, United States, 2012: With special feature on Emergency Care Hyattsville, MD; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boczko F, McKeon S, Sturkie D. Long-term care and oral health knowledge. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009;10:204–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Visschere L, Schols J, van der Putten GJ, de Baat C, Vanobbergen J. Effect evaluation of a supervised versus non-supervised implementation of an oral health care guideline in nursing homes: a cluster randomised controlled clinical trial. Gerodontology 2012;29:e96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Visschere LM, van der Putten GJ, Vanobbergen JN, Schols JM, de Baat C, Dutch Association of Nursing Home Physicians. An oral health care guideline for institutionalised older people. Gerodontology 2011;28:307–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Putten GJ, Mulder J, de Baat C, De Visschere LM, Vanobbergen JN, Schols JM. Effectiveness of supervised implementation of an oral health care guideline in care homes; a single-blinded cluster randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig 2013;17:1143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Visschere L, de Baat C, Schols JM, Deschepper E, Vanobbergen J. Evaluation of the implementation of an ‘oral hygiene protocol’ in nursing homes: a 5-year longitudinal study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011;39:416–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forsell M, Kullberg E, Hoogstraate J, Herbst B, Johansson O, Sjögren P. A survey of attitudes and perceptions toward oral hygiene among staff at a geriatric nursing home. Geriatr Nurs 2010;31:435–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thorne S, Kazanjian A, MacEntee M. Oral health in long-term care -The implications of organizational culture. Journal of Aging Studies 2001;15:271–83. [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Visschere L, de Baat C, De Meyer L, et al. The integration of oral health care into day-to-day care in nursing homes: a qualitative study. Gerodontology 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.de Lugt-Lustig KH, Vanobbergen JN, van der Putten GJ, De Visschere LM, Schols JM, de Baat C. Effect of oral healthcare education on knowledge, attitude and skills of care home nurses: a systematic literature review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Forsell M, Kullberg E, Hoogstraate J, Johansson O, Sjögren P. An evidence-based oral hygiene education program for nursing staff. Nurse Educ Pract 2011;11:256–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kullberg E, Forsell M, Wedel P, et al. Dental hygiene education for nursing staff. Geriatr Nurs 2009;30:329–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vanobbergen JN, De Visschere LM. Factors contributing to the variation in oral hygiene practices and facilities in long-term care institutions for the elderly. Community Dent Health 2005;22:260–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weening-Verbree L, Huisman-de Waal G, van Dusseldorp L, van Achterberg T, Schoonhoven L. Oral health care in older people in long term care facilities: a systematic review of implementation strategies. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:569–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pruksapong M, MacEntee MI. Quality of oral health services in residential care: towards an evaluation framework. Gerodontology 2007;24:224–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caplan DJ, Slade GD, Gansky SA. Complex sampling: implications for data analysis. J Public Health Dent 1999;59:52–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Ness PH, Peduzzi PN, Quagliarello VJ. Efficacy and effectiveness as aspects of cluster randomized trials with nursing home residents: methodological insights from a pneumonia prevention trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33:1124–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Putten GJ, De Visschere L, Schols J, de Baat C, Vanobbergen J. Supervised versus non-supervised implementation of an oral health care guideline in (residential) care homes: a cluster randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2010;10:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wyatt CC, Maupome G, Hujoel PP, et al. Chlorhexidine and preservation of sound tooth structure in older adults. A placebo-controlled trial. Caries Res 2007;41:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gonda T, MacEntee MI, Kiyak HA, Persson GR, Persson RE, Wyatt C. Predictors of multiple tooth loss among socioculturally diverse elderly subjects. Int J Prosthodont 2013;26:127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sajjan P, Nagesh L, Sajjanar M, Reddy S, Venktesh U. Comparative evaluation of chlorhexidine varnish and fluoride varnish on plaque Streptococcus mutans count -an in vivo study. International Journal of Dental Hygiene 2013;11:191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rethman MP, Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Billings RJ, et al. Nonfluoride caries-preventive agents: executive summary of evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc 2011;142:1065–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging 2009;13:782–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997;25:284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Atchison KA, Dolan TA. Development of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. J Dent Educ 1990;54:680–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]