Abstract

Autophagy is an evolutionarily-conserved self-degradative process that maintains cellular homeostasis by eliminating protein aggregates and damaged organelles. Recently, vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B (VAPB), which is associated with the familial form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, has been shown to regulate autophagy. In the present study, we demonstrated that knockdown of VAPB induced the up-regulation of beclin 1 expression, which promoted LC3 (microtubule-associated protein light chain 3) conversion and the formation of LC3 puncta, whereas overexpression of VAPB inhibited these processes. The regulation of beclin 1 by VAPB was at the transcriptional level. Moreover, knockdown of VAPB increased autophagic flux, which promoted the degradation of the autophagy substrate p62 and neurodegenerative disease proteins. Our study provides evidence that the regulation of autophagy by VAPB is associated with the autophagy-initiating factor beclin 1.

Keywords: VAPB, Autophagy, Beclin 1, ALS, Autophagic flux, LC3

Introduction

Autophagy is an evolutionarily-conserved cellular process that degrades long-lived proteins, cytosolic aggregated proteins, and damaged organelles via lysosomes [1]. The process of autophagy includes autophagosome formation, a step in which the cytoplasmic components are sequestered in a double membrane; autolysosome formation by fusion of mature autophagosomes with lysosomes; and substrate degradation in which the cargo-containing substrates are degraded by proteases in the lysosome [2]. Autophagy plays roles in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis in physiologically normal and stress conditions [3], but is also involved in many disease processes, such as neurodegeneration, aging, inflammation, and metabolism [1, 3, 4]. Multiple cellular factors are associated with the regulation of autophagy, including nutrient status, oxidative stress, and Ca2+ signaling [5–7]. Oxidative stress is tightly associated with Ca2+ signaling and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and is related to the pathogenesis of many diseases [7–9]. Recently, vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B (VAPB), an integral ER-membrane protein, has been reported to regulate autophagy through ER-mitochondrial signaling [10].

VAPB is a multi-functional protein, involved in ER-to-Golgi protein trafficking [11, 12], neuromuscular junction development [13], and neurite extension [14]. Mutations in VAPB cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [15–17], a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the progressive degeneration of motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord [18]. Although the mechanism by which mutant VAPB causes ALS remains unknown, transgenic mice with the P56S mutant of VAPB present with abnormal aggregation of mutant VAPB [19–21]. In addition, P56S VAPB knock-in mice also show progressive defects in motor behaviors, with cytoplasmic inclusions that are labeled with VAPB, ubiquitin, and LC-3 (microtubule-associated protein light chain 3), but not ER markers [22]. Furthermore, in P56S VAPB knock-in mice, the mutant VAPB induces ER stress [22].

Although P56S VAPB mice show positive phenotypes that suggest a role of mutant VAPB in disease pathogenesis, the normal function of VAPB as well as its association with disease is still unclear. Most recently, VAPB has been shown to interact with mitochondrial protein tyrosine phosphatase-interacting protein 51 (PTPIP51), which regulates ER-mitochondria contacts [23]. Overexpression of VAPB increases these contacts, leading to an increased exchange of Ca2+ between ER and mitochondria. However, knockdown of VAPB decreases the contacts and Ca2+ delivery from ER to mitochondria, thus increasing cytosolic Ca2+ and inducing autophagy [10].

In the present study, we demonstrated that VAPB knockdown-induced autophagy is mediated by beclin 1. Knockdown of VAPB increased beclin 1 at both the protein and mRNA levels, suggesting transcriptional regulation of beclin 1 by VAPB. Thus, our study provides insight into the mechanisms underlying VAPB-regulated autophagy.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Treatment

HeLa, HEK293, and HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Los Angeles, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 μg/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were cultured at the same passage number for experimental consistency. SH-SY5Y cells were grown in DMEM/F12 (Gibco). Cells were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2. For transient overexpression, the cultured cells were transfected with plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were harvested for immunoblot or immunofluorescence analysis. HEK293 cells that stably expressed mCherry-LC3 were obtained by fluorescent sorting with a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) after transient transfection. HEK293 cells transfected with si-VAPB were treated with bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) at 100 nmol/L or MG132 (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 10 μmol/L. Twenty-four hours later, the treated cells were used in experiments.

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA)

RNA oligonucleotides were transfected into cells with RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). Briefly, the cells were incubated in a mixture of Opti-MEM, RNAiMAX, and RNA oligonucleotides for 20 min at room temperature before transfection. Twelve hours later, the medium was replaced with fresh complete medium. The cells were collected 72 h after transfection for further analysis. The oligonucleotides that target human VAPB, VAPA (vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A), and Beclin 1 were from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The sequences were as follows: si-VAPB #1 sense 5’-UGUUACAGCCUUUCGAUUATT-3’, antisense 5’-UAAUCGAAAGGCUGUAACATT-3’; si-VAPB #2 sense 5’-GGUUCAGUCUAUGUUUGCUTT-3’, antisense 5’-GCAAACAUAGACUGAACCTT-3’; si-VAPA sense 5’-GGCAAAACCUGAUGAAUUATT-3’, antisense 5’-UAAUUCAUCAGGUUUUGCCTT-3’; si-Beclin 1 sense 5’-UUCAACACUCUUCAGCUCAUCAUCCTT-3’, antisense 5’-GGAUGAUGAGCUGAAGAGUGUUGAATT-3’.

Immunoblot Analysis and Antibodies

The cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and a complete protein inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Approximately 20 μg of lysate was separated on SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). The following antibodies were used for immunoblot analysis: anti-β-actin (Sigma), anti-FLAG (M2, F3165, Sigma), anti-GAPDH (MAB374, Chemicon, Temecula, CA), anti-GFP (sc-9996, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), anti-LC3 (NB100-2220, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), anti-VAPA (D223525, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). and anti-VAPB (14477-1AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL).

The anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). The proteins were viewed with an ECL detection kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA).

Plasmids

The EGFP-LC3 and FLAG-P62 plasmids were as described previously [24]. Full-length human VAPB cDNA was amplified using PCR from a human fetal brain cDNA library with the primers 5’-GAGGATCCCCATGGCCTTGGCCGGGGCC-3’ and 5’-GAGAATCCCGAAATCCAGGGGGTGA-3’. The PCR product was inserted in-frame into the pKH3 vector at the BamHI/EcoRI sites to obtain FLAG-VAPB plasmids. The plasmid pmCherry-EGFP-LC3B (human) was from Bioworld Technology (Nanjing, China) and the plasmid FLAG-VAPA (human) was from YouBio (Changsha, China).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min, and then blocked for 3 min with 4% fetal bovine serum containing 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The cells were then incubated with mouse anti-FLAG antibody followed by incubation with rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen). The cells were then stained with Hoechst (Sigma). After staining, the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, IX71, Tokyo, Japan) or a confocal microscope (LSM710, Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from HEK293T cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and then reverse-transcribed into cDNA for PCR assays with a TransScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Otsu, Shiga, Japan). The primer pairs used for qRT-PCR were as follows: human β-actin sense 5’-GACCTGACTGACTACCTC-3’, antisense 5’-GACAGCGAGGCCAGGATG-3’; human Beclin 1 sense 5’-CTCGACAGATCG-3’, antisense 5’-GATCCGTTTCACC-3’.

Statistical Analysis

Densitometric analyses of immunoblots from three independent experiments were performed using Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA). The data were analyzed using Prism6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The quantitative data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed via one-way ANOVA and significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Knockdown of VAPB Activates Autophagy

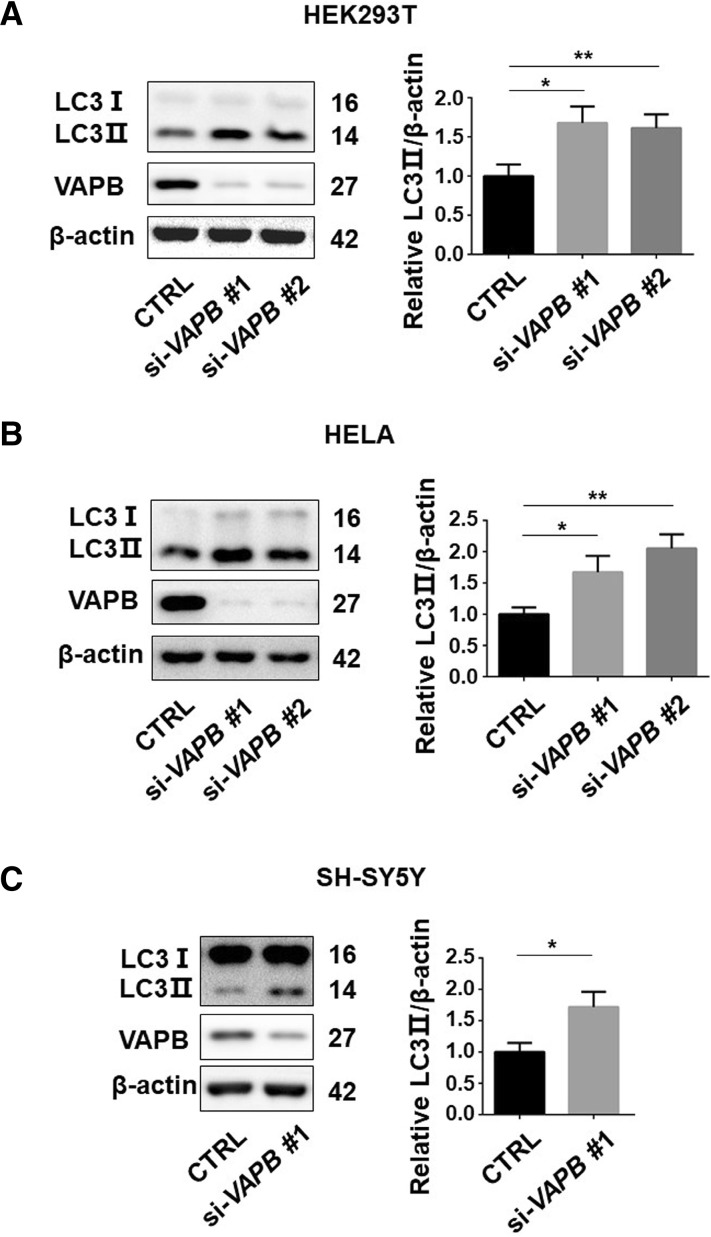

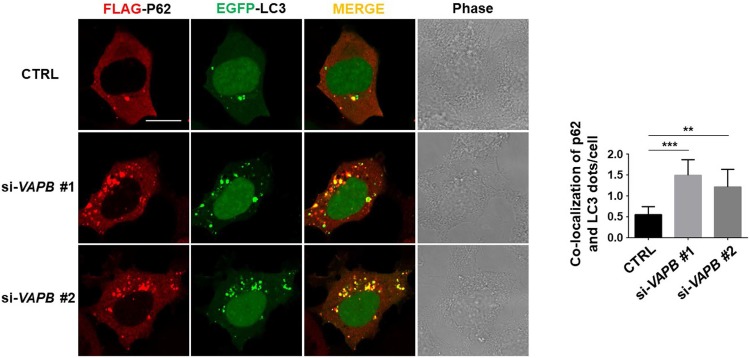

To investigate whether VAPB is involved in the regulation of autophagy, we used two siRNAs to silence VAPB expression in three cell lines, HEK293T, HeLa, and SH-SY5Y cells. Knockdown of VAPB with both of the siRNAs against VAPB significantly increased the LC3-II levels in all three cell lines (Fig. 1A–C), suggesting that VAPB deficiency leads to autophagosome formation across diverse cell types. The ubiquitin-binding autophagic adaptor p62/SQSTM1 has been shown to bind to LC3 and mediate the engulfment of autophagic cargoes into autophagosomes, so the co-localization of p62 and LC3 puncta may serve as a marker of autophagosome formation [25, 26]. We found an increased co-localization of FLAG-p62 with EGFP-LC3 puncta in VAPB-knockdown cells (Fig. 2). Together, these data indicated that VAPB deficiency activates autophagy.

Fig. 1.

Loss of VAPB activates autophagy. A–C Immunoblots (left) and statistics (right) of LC3, VAPB, and β-actin antibodies in lysates of HEK293T (A), HeLa (B), and SH-SY5Y (C) cells transfected with si-Ctrl (negative control siRNA), si-VAPB#1, or si-VAPB#2 for 72 h (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

VAPB deficiency is essential for autophagosome formation. Immunofluorescence images of FLAG-P62 (red) and EGFP-LC3 (green) puncta (left) and statistics of co-localization (right) in HEK293 cells transfected with two kinds of si-VAPB for 24 h (n = 30–40; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

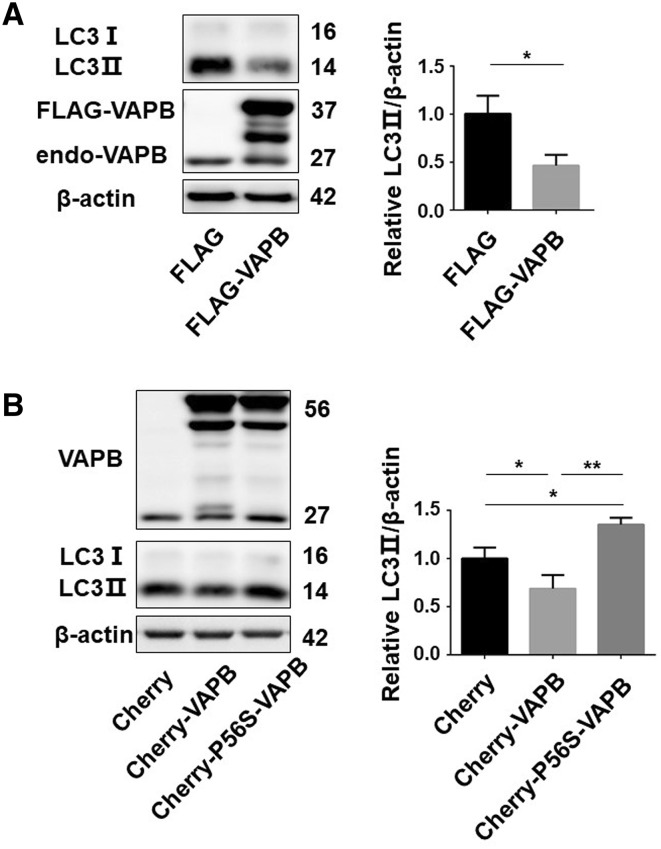

Overexpression of Wild-Type VAPB but not P56S-VAPB Inhibits Autophagy

As VAPB deficiency activates autophagy, we next investigated the effect of VAPB overexpression. We found that overexpression of FLAG-VAPB inhibited the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II (Fig. 3A), suggesting an inhibition of autophagy by VAPB overexpression. The P56S mutation in VAPB (P56S-VAPB) has been reported to cause familial ALS [17], so we assessed its effect on autophagy. Surprisingly, overexpression of P56S-VAPB significantly increased the LC3II protein levels compared with control (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the P56S mutant lost the ability to inhibit autophagy. These data indicate that wild-type VAPB inhibits autophagy, whereas the ALS-associated mutation P56S-VAPB plays a different role in the regulation of autophagy.

Fig. 3.

Wild-type VAPB but not P56S-VAPB inhibits autophagy. A LC3 protein levels in HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG-VAPB for 48 h (n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). B LC3 protein levels in HEK293T cells transfected with mCherry-VAPB or mCherry-P56S-VAPB for 48 h (n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

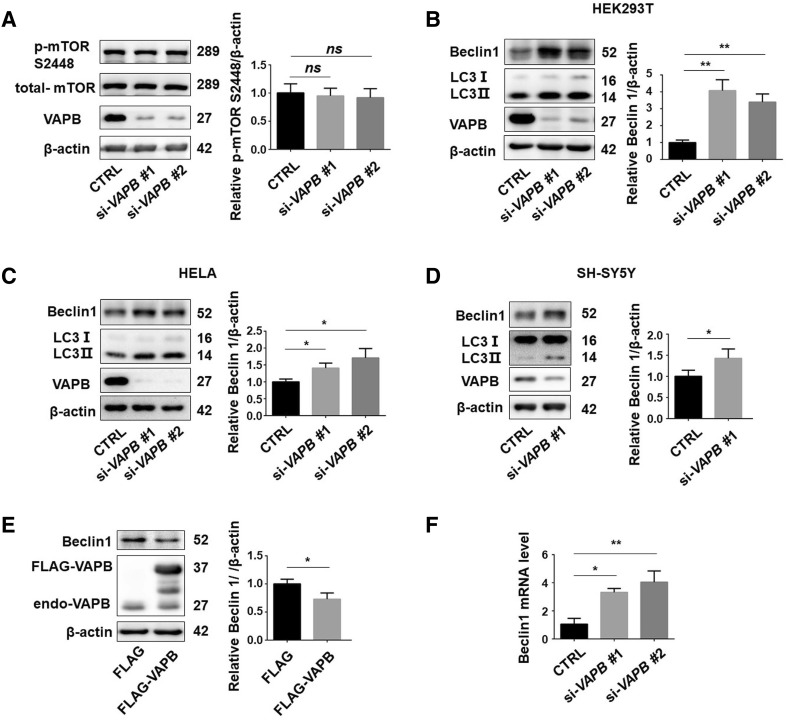

Activation of Beclin 1 Transcription by Knockdown of VAPB

As VAPB was found to regulate autophagy, we set out to determine which pathway is involved in the autophagosome formation induced by VAPB deficiency. We examined mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and beclin 1, proteins that are considered to regulate the initiation of autophagy [27–29]. In VAPB-knockdown cells, the phosphorylation of mTOR remained unchanged (Fig. 4A). However, knockdown of VAPB significantly up-regulated the beclin 1 protein levels in HEK293T, HeLa, and SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 4B–D). Consistently, overexpression of FLAG-VAPB down-regulated the beclin 1 protein levels (Fig. 4E). Moreover, the Beclin 1 mRNA levels were also dramatically up-regulated by knockdown of VAPB (Fig. 4F). These data suggested that VAPB deficiency transcriptionally induces beclin 1 expression.

Fig. 4.

VAPB deficiency transcriptionally activates beclin 1 expression. A Phosphorylated m-TOR (S2248) in HEK293T cells transfected with each of two kinds of si-VAPB for 72 h (n = 3; ns, no significant difference). B–D Beclin 1 protein levels in HEK293T (B), HeLa (C) and SH-SY5Y (D) cells transfected with each of two kinds of si-VAPB for 72 h. E Beclin 1 protein levels in HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG-VAPB for 48 h. F qRT-PCR assays of the mRNA levels of Beclin 1 in HEK293T cells transfected with the two kinds of si-VAPB for 72 h (n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

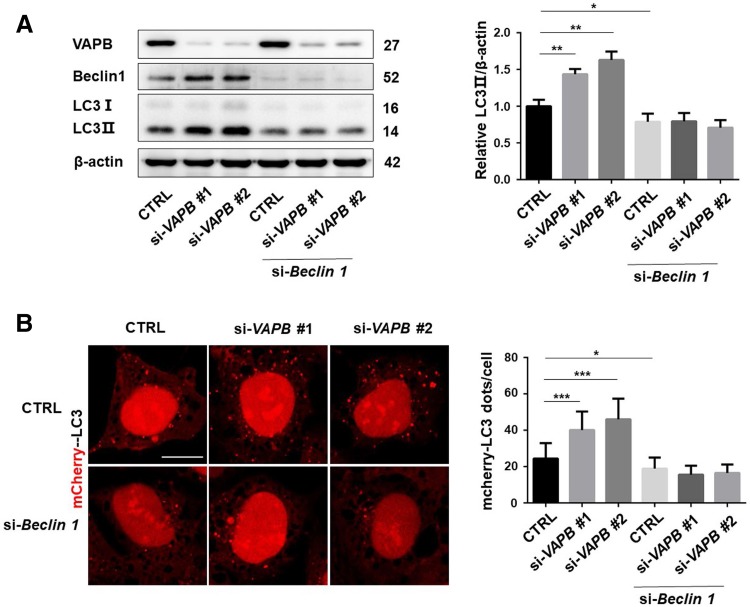

Loss of VAPB Affects Autophagy in a Beclin 1-Dependent Manner

To further identify the role of beclin 1 in VAPB-regulated autophagy, we examined the LC3 levels after knockdown of beclin 1 in VAPB-knockdown cells. Knockdown of VAPB significantly increased LC3 conversion, but failed to do so in cells in which beclin 1 was silenced (Fig. 5A). Consistently, in HEK293 cells stably expressing mCherry-LC3, knockdown of VAPB induced the formation of LC3 puncta, but failed to do so in beclin 1-knockdown cells (Fig. 5B). These data further suggested that loss of VAPB induces autophagy in a beclin 1-dependent manner.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of VAPB induces autophagy in a beclin 1-dependent manner. A Immunoblots (left) and statistics (right) of LC3 in HeLa cells co-transfected with si-Beclin 1 and two kinds of si-VAPB for 72 h (n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). B Confocal microscopic images (left) and statistics (right) of LC3 puncta in HEK293 cells stably expressing mCherry-LC3 and transfected with si-Beclin 1 and each of two kinds of si-VAPB for 72 h (scale bar, 10 μm; n = 30; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001).

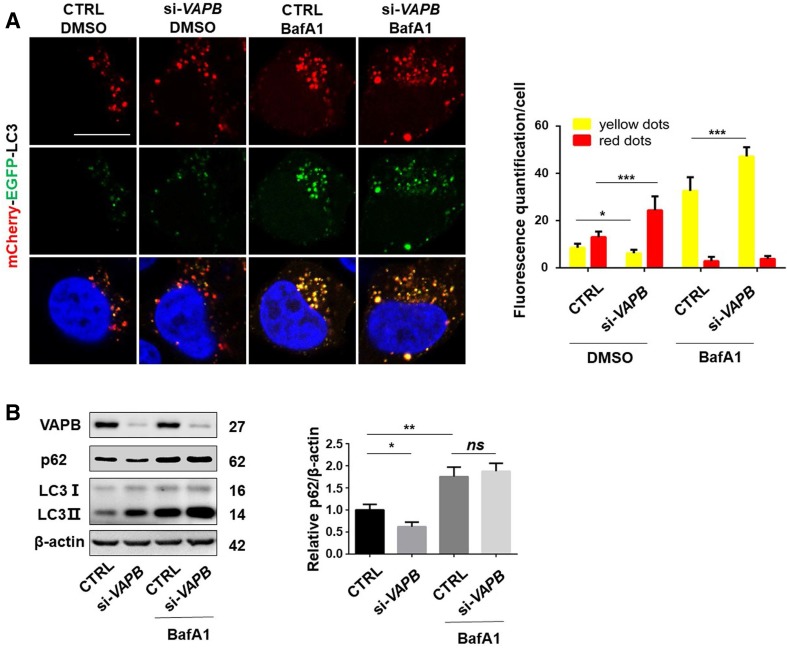

Loss of VAPB Promotes Autophagic Flux

We then examined whether VAPB affects the whole process of dynamic autophagy, autophagic flux. We knocked VAPB down in cells expressing mCherry-EGFP-LC3B. The mCherry (red) and EGFP (green) together emitted yellow fluorescence in autophagosomes; however, when autolysosomes were formed, the pH-sensitive EGFP fluorescence was lost while the red fluorescence was preserved [30, 31], which suggested the successful fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes and the degradation of cargoes by lysosomes in autophagic flux. A decreased yellow LC3 ratio and an increased red fluorescence ratio were present in VAPB-knockdown cells relative to control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 6A), giving a different appearance to those treated with BafA1, a vacuolar-type H+-ATPase inhibitor that decreases lysosome acidification and affects the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes (Fig. 6A). In addition, the yellow fluorescence further increased in VAPB-knockdown cells compared with controls under BafA1 treatment (Fig. 6A). These data suggested that loss of VAPB induces autophagosome formation and promotes autophagic flux. Moreover, we examined the effect of VAPB on the autophagy-mediated degradation of p62, a well-known autophagy substrate [32, 33]. Knockdown of VAPB significantly decreased the p62 protein levels, but failed to do so in cells treated with BafA1 (Fig. 6B). Together, these data suggested that loss of VAPB induces autophagic flux and promotes the degradation of autophagy substrates.

Fig. 6.

Loss of VAPB increases autophagic flux. A Confocal microscopic images (left) and statistics (right) of EGFP-LC3 and mCherry-LC3 punctate aggregates in HeLa cells transfected with si-VAPB#1 for 24 h, then with mCherry-EGFP-LC3 for 24 h, and then treated with or without 100 nmol/L BafA1 for 4 h. Yellow, number of green/red merged aggregates; red, number of mCherry-LC3 aggregates (scale bar, 10 μm; n = 30–40; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). B Immunoblots (left) and analysis (right) of p62, VAPB, and β-actin antibodies in lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with si-Ctrl, or si-VAPB#1 for 48 h then treated with or without 100 nmol/L BafA1 for 12 h (n = 3; ns, no significant difference, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

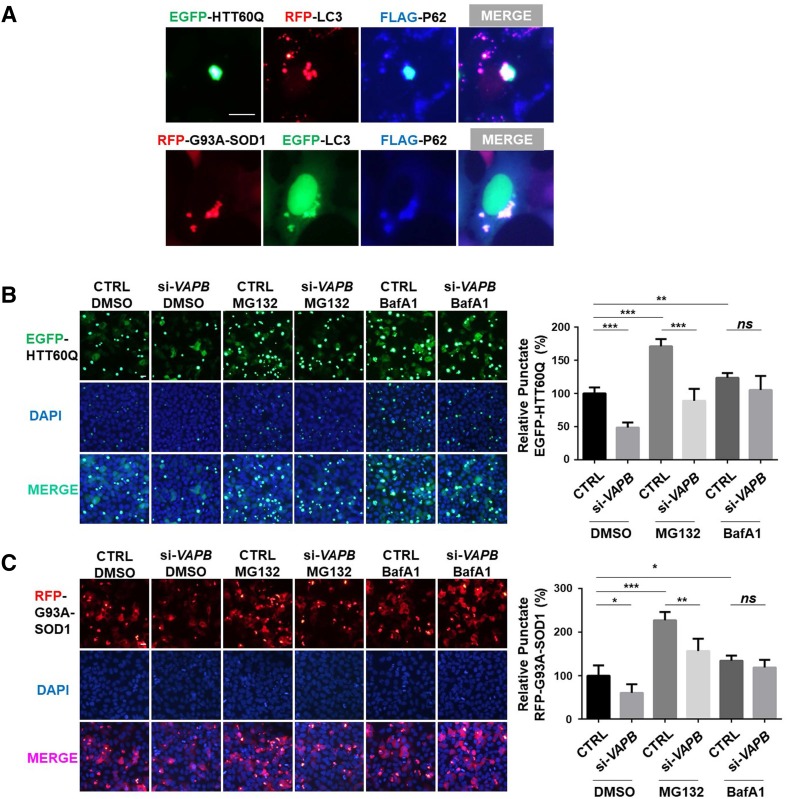

Loss of VAPB Increases the Degradation of Neurodegenerative Disease-Related Proteins

Since VAPB deficiency promoted autophagic flux, we further investigated whether the flux induced by VAPB-knockdown promotes the degradation of proteins that are prone to aggregate, such as mutant huntingtin and mutant superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1). SOD1-G93A is one of the most important pathogenic proteins of ALS [34]. We found that aggregates formed by RFP-G93A-SOD1 or EGFP-HTT60Q, a truncated fragment of huntingtin with 60Q [35, 36], co-localized with autophagosomes (Fig. 7A). The number of aggregates of EGFP-HTT60Q or RFP-SOD1-G93A was lower in VAPB-knockdown cells, indicating that VAPB-deficiency induces the degradation of EGFP-HTT60Q and RFP-SOD1-G93A (Fig. 7B, C). MG132 treatment increased the aggregates of EGFP-HTT60Q and RFP-SOD1-G93A more than BafA1 (Fig. 7B, C), suggesting that EGFP-HTT60Q and RFP-SOD1-G93A are mainly degraded by the proteasome. However, the decrease of aggregates caused by VAPB deficiency was not blocked in the presence of MG132, but was distinctly blocked in the presence of BafA1 (Fig. 7B, C), which indicated that the degradation of EGFP-HTT60Q and RFP-SOD1-G93A by VAPB-deficiency is associated with the regulation of autophagy.

Fig. 7.

Loss of VAPB increases the degradation of neurodegenerative disease-related proteins. A Immunofluorescence images of the co-localization of EGFP-HTT60Q, mCherry-LC3, and FLAG-P62, or RFP-SOD1-G93A, EGFP-LC3, and FLAG-P62 transfected into HEK293 cells for 24 h. B–C Fluorescence microscopic images (left) and quantitation (right) of aggregation in HEK293 cells transfected with si-VAPB#1 for 24 h, and then with EGFP-HTT60Q (B) or RFP-SOD1-G93A (C) for 24 h and then treated with 10 μmol/L MG132 or 100 nmol/L BafA1 for 12 h. The relative quantity of punctate EGFP-HTT60Q or RFP-G93A-SOD1 was statistically analyzed (n = 200–300; ns, no significant difference, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

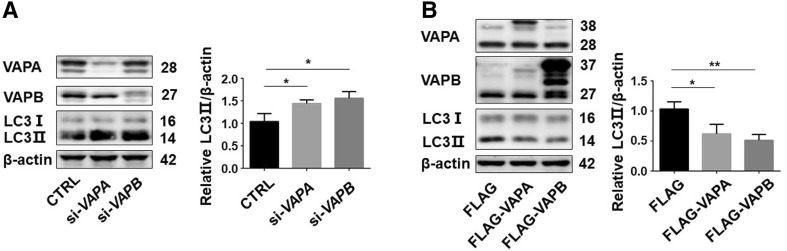

VAPA and VAPB Have Similar Functions in Autophagy Regulation

VAPA is another VAP which is structurally and functionally related to VAPB in cells [37, 38]. So, we also investigated its effect on autophagy. Interestingly, similar to VAPB, VAPA-knockdown upregulated LC3II protein levels (Fig. 8A), while VAPA overexpression decreased them (Fig. 8B). These results indicated that VAPA and VAPB have similar functions in the regulation of autophagy.

Fig. 8.

VAPA and VAPB have similar functions in autophagy regulation. A Immunoblots (left) and statistics (right) of LC3, VAPA, VAPB, and β-actin antibodies in lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with si-Ctrl, si-VAPA and si-VAPB#1 for 72 h. B LC3 protein levels in HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG-VAPA or FLAG-VAPB for 48 h. n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that knockdown of VAPB induces the initiation of autophagy by activating beclin 1 transcription. Knockdown of beclin 1 completely blocked the VAPB loss-induced autophagy, suggesting an involvement of beclin 1 in VAPB-mediated autophagy.

Beclin 1 was originally identified as a Bcl-2-interacting protein [39], functioning in multiple cellular pathways and diseases, such as development, innate immunity, cancer suppression, and neuroprotection [40]. Beclin 1 is involved in activating autophagy through its interaction with other proteins, including ATG14L and VPS34 (vacuolar protein sorting 34), a class III phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase [40]. The complex formed by beclin 1 and its partners functions to generate phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate that promotes autophagosome nucleation [41]. Knockdown of VAPB disturbs VAPB-PTPIP51 interactions, resulting in a decrease of ER-mitochondrial contact, thus increasing cytosolic Ca2+ [23]. The elevated cytosolic Ca2+ may activate the expression of c-FOS that acts as an element of AP-1 to regulate the transcription of beclin 1 [42], an important factor for autophagosome nucleation [29, 43]. It is therefore possible that an increase of cytosolic Ca2+ induced by knockdown of VAPB is responsible for the up-regulation of beclin 1, thereby activating autophagy.

Both loss-of-function and gain-of-function have been documented in VAPB animal models. VAPB P56S transgenic mice present TDP-43-positive aggregates in motor neurons [44] and P56S knock-in mice show motor defects [22], suggesting a gain-of-function. However, knockdown of VAPB in zebrafish or its knockout in mice induces motor symptoms similar to ALS [45]; and in ALS patients, the expression of VAPB is decreased in the spinal cord [46], suggesting a loss-of-function mechanism. Here, we found that overexpression of wild-type VAPB inhibited autophagy, while overexpression of VAPB (P56S) increased LC3II levels, suggesting that, unlike the wild-type, VAPB (P56S) has different effects on autophagy regulation. Although the pathological role of VAPB in ALS remains unclear, its role in the regulation of ER-mitochondrial contact and autophagy is certain. In the present study, we found that VAPB regulated beclin 1 expression for autophagy activation.

In summary, we found that knockdown of VAPB activated autophagy by promoting the expression of beclin 1 at the transcriptional level. The activation of autophagy by knockdown of VAPB promoted the degradation of the autophagy substrate p62 and neurodegenerative disease proteins. This study increases our understanding of the mechanism of autophagy regulation by VAPB.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1306000), the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (31330030, 31471012, and 81761148024), and a Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Haigang Ren, Email: rhg@suda.edu.cn.

Guanghui Wang, Email: wanggh@suda.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galluzzi L, Pietrocola F, Levine B, Kroemer G. Metabolic control of autophagy. Cell. 2014;159:1263–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin CW, Chen B, Huang KL, Dai YS, Teng HL. Inhibition of autophagy by estradiol promotes locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury in rats. Neurosci Bull. 2016;32:137–144. doi: 10.1007/s12264-016-0017-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell RC, Yuan HX, Guan KL. Autophagy regulation by nutrient signaling. Cell Res. 2014;24:42–57. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippi-Chiela EC, Viegas MS, Thome MP, Buffon A, Wink MR, Lenz G. Modulation of autophagy by calcium signalosome in human disease. Mol Pharmacol. 2016;90:371–384. doi: 10.1124/mol.116.105171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yap YW, Llanos RM, La Fontaine S, Cater MA, Beart PM, Cheung NS. Comparative microarray analysis identifies commonalities in neuronal injury: evidence for oxidative stress, dysfunction of calcium signalling, and inhibition of autophagy-lysosomal pathway. Neurochem Res. 2016;41:554–567. doi: 10.1007/s11064-015-1666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao K, Wang B, Feng D, Zhang W, Lu F, Lai J, et al. Salidroside protects against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced cytotoxicity by attenuating ER stress. Neurosci Bull. 2016;32:61–69. doi: 10.1007/s12264-015-0001-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Q, Yang X, Cai D, Ye L, Hou Y, Zhang L, et al. Echinacoside protects against MPP(+)-induced neuronal apoptosis via ROS/ATF3/CHOP pathway regulation. Neurosci Bull. 2016;32:349–362. doi: 10.1007/s12264-016-0047-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez-Suaga P, Paillusson S, Stoica R, Noble W, Hanger DP, Miller CC. The ER-mitochondria tethering complex VAPB-PTPIP51 regulates autophagy. Curr Biol. 2017;27:371–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peretti D, Dahan N, Shimoni E, Hirschberg K, Lev S. Coordinated lipid transfer between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi complex requires the VAP proteins and is essential for Golgi-mediated transport. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3871–3884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-05-0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuijpers M, Yu KL, Teuling E, Akhmanova A, Jaarsma D, Hoogenraad CC. The ALS8 protein VAPB interacts with the ER-Golgi recycling protein YIF1A and regulates membrane delivery into dendrites. EMBO J. 2013;32:2056–2072. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennetta G, Hiesinger PR, Fabian-Fine R, Meinertzhagen IA, Bellen HJ. Drosophila VAP-33A directs bouton formation at neuromuscular junctions in a dosage-dependent manner. Neuron. 2002;35:291–306. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuzaki F, Shirane M, Matsumoto M, Nakayama KI. Protrudin serves as an adaptor molecule that connects KIF5 and its cargoes in vesicular transport during process formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:4602–4620. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-01-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura AL, Mitne-Neto M, Silva HC, Richieri-Costa A, Middleton S, Cascio D, et al. A mutation in the vesicle-trafficking protein VAPB causes late-onset spinal muscular atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:822–831. doi: 10.1086/425287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanekura K, Nishimoto I, Aiso S, Matsuoka M. Characterization of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked P56S mutation of vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B (VAPB/ALS8) J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30223–30233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen HJ, Anagnostou G, Chai A, Withers J, Morris A, Adhikaree J, et al. Characterization of the properties of a novel mutation in VAPB in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40266–40281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.161398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor JP, Brown RH, Jr, Cleveland DW. Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism. Nature. 2016;539:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature20413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuijpers M, van Dis V, Haasdijk ED, Harterink M, Vocking K, Post JA, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-associated VAPB-P56S inclusions represent an ER quality control compartment. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:24. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aliaga L, Lai C, Yu J, Chub N, Shim H, Sun L, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-related VAPB P56S mutation differentially affects the function and survival of corticospinal and spinal motor neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4293–4305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiu L, Qiao T, Beers M, Tan W, Wang H, Yang B, et al. Widespread aggregation of mutant VAPB associated with ALS does not cause motor neuron degeneration or modulate mutant SOD1 aggregation and toxicity in mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2013;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larroquette F, Seto L, Gaub PL, Kamal B, Wallis D, Lariviere R, et al. Vapb/Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 8 knock-in mice display slowly progressive motor behavior defects accompanying ER stress and autophagic response. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:6515–6529. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Vos KJ, Morotz GM, Stoica R, Tudor EL, Lau KF, Ackerley S, et al. VAPB interacts with the mitochondrial protein PTPIP51 to regulate calcium homeostasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1299–1311. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo D, Ying Z, Wang H, Chen D, Gao F, Ren H, et al. Regulation of autophagic flux by CHIP. Neurosci Bull. 2015;31:469–479. doi: 10.1007/s12264-015-1543-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heras-Sandoval D, Perez-Rojas JM, Hernandez-Damian J, Pedraza-Chaverri J. The role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in the modulation of autophagy and the clearance of protein aggregates in neurodegeneration. Cell Signal. 2014;26:2694–2701. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:571–580. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy. 2007;3:452–460. doi: 10.4161/auto.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahani MH, Itakura E, Mizushima N. Expression of the autophagy substrate SQSTM1/p62 is restored during prolonged starvation depending on transcriptional upregulation and autophagy-derived amino acids. Autophagy. 2014;10:431–441. doi: 10.4161/auto.27344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He L, Chen L, Li L. The TBK1-OPTN axis mediates crosstalk between mitophagy and the innate immune response: a potential therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:354–356. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0116-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng HX, Hentati A, Tainer JA, Iqbal Z, Cayabyab A, Hung WY, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and structural defects in Cu. Zn superoxide dismutase. Science. 1993;261:1047–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.8351519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jana NR, Tanaka M, Wang G, Nukina N. Polyglutamine length-dependent interaction of Hsp40 and Hsp70 family chaperones with truncated N-terminal huntingtin: their role in suppression of aggregation and cellular toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2009–2018. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.13.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li HL, Zhang YB, Wu ZY. Development of research on Huntington disease in China. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:312–316. doi: 10.1007/s12264-016-0093-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi J, Lua S, Tong JS, Song J. Elimination of the native structure and solubility of the hVAPB MSP domain by the Pro56Ser mutation that causes amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3887–3897. doi: 10.1021/bi902057a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong R, Saheki Y, Swarup S, Lucast L, Harper JW, De Camilli P. Endosome-ER contacts control actin nucleation and retromer function through VAP-dependent regulation of PI4P. Cell. 2016;166:408–423. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang XH, Kleeman LK, Jiang HH, Gordon G, Goldman JE, Berry G, et al. Protection against fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis by beclin, a novel Bcl-2-interacting protein. J Virol. 1998;72:8586–8596. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8586-8596.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Brien CE, Wyss-Coray T. Sorting through the roles of beclin 1 in microglia and neurodegeneration. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2014;9:285–292. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9519-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He C, Levine B. The Beclin 1 interactome. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang JD, Cao YL, Li Q, Yang YP, Jin M, Chen D, et al. A pivotal role of FOS-mediated BECN1/Beclin 1 upregulation in dopamine D2 and D3 receptor agonist-induced autophagy activation. Autophagy. 2015;11:2057–2073. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kihara A, Kabeya Y, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Beclin-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex functions at the trans-Golgi network. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:330–335. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tudor EL, Galtrey CM, Perkinton MS, Lau KF, De Vos KJ, Mitchell JC, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mutant vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein-B transgenic mice develop TAR-DNA-binding protein-43 pathology. Neuroscience. 2010;167:774–785. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kabashi E, El Oussini H, Bercier V, Gros-Louis F, Valdmanis PN, McDearmid J, et al. Investigating the contribution of VAPB/ALS8 loss of function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:2350–2360. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anagnostou G, Akbar MT, Paul P, Angelinetta C, Steiner TJ, de Belleroche J. Vesicle associated membrane protein B (VAPB) is decreased in ALS spinal cord. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:969–985. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]