ABSTRACT

Nutrition research can guide interventions to tackle the burden of diet-related diseases. Setting priorities in nutrition research, however, requires the engagement of various stakeholders with diverse insights. Consideration of what matters most in research from a scientific, social, and ethical perspective is therefore not an automatic process. Systematic ways to explicitly define and consider relevant values are largely lacking. Here, we review existing nutrition research priority-setting exercises, analyze how values are reported, and provide guidance for transparent consideration of values while setting priorities in nutrition research. Of the 27 (n = 22 peer-reviewed manuscripts and 5 grey literature documents) studies reviewed, 40.7% used a combination of different methods, 59.3% described the represented stakeholders, and 49.1% reported on follow-up activities. All priority-setting exercises were led by research groups based in high-income countries. Via an iterative qualitative content analysis, reported values were identified (n = 22 manuscripts). Three clusters of values (i.e., those related to impact, feasibility, and accountability) were identified. These values were organized in a tool to help those involved in setting research priorities systematically consider and report values. The tool was finalized through an online consultation with 7 international stakeholders. The value-oriented tool for priority setting in nutrition research identifies and presents values that are already implicitly and explicitly represented in priority-setting exercises. It provides guidance to enable explicit deliberation on research priorities from an ethical perspective. In addition, it can serve as a reporting tool to document how value-laden choices are made during priority setting and help foster the accountability of stakeholders involved.

Keywords: nutrition, priority setting, values, guidance, tool, ethics

Introduction

Poor diets are the leading risk factor for ill health and mortality worldwide (1). Nutrition epidemiology examines associations between diet and health, and informs actions to improve population well-being and health. Research prioritization is key to make targeted choices, optimize the global investment, and accelerate progress in nutrition research in general. Research priority setting is a formal procedure of generating consensus about a set of research questions that are considered when guiding resource allocation (2). There is no golden standard to prioritize research. Many comprehensive approaches to health research prioritization exist and provide structured as well as flexible options for stakeholders to reach consensus (3).

Transparency about values that underlie this process is key (4). Values are “the things and events in life that people desire, aim at, wish for, or demand” (5). A proper and systematic consideration of values during the process of a priority-setting exercise has the potential to improve the quality of research by enhancing relevance, uptake, and societal impact (6, 7). Stakeholders involved in the process come with their own values and interests (8). Reflections on whose interests are served are relevant for readers and they enhance transparency and accountability.

Like other biomedical sciences, nutrition research needs to consider how research waste can be avoided and value can be added (9). Considerable efforts have already been made to enhance downstream aspects of the research value chain, in particular the quality of research conduct (10) and the reporting of findings (11). The development of upstream processes, however, has received less attention. In particular, the governance of research via the development of practical tools to improve priority setting needs attention (9).

Scholars have called for an explicit value framework to assist stakeholders when setting health research priorities (2). Current ethical frameworks for priority setting (2, 12–14) often predefine values. However, the choice of these values is not justified explicitly and current frameworks are generally theoretic, without consideration of practical implementation (6).

Here, we provide guidance for the consideration of values for future priority-setting exercises in nutrition research. We present a tool to enable explicit reflection and transparency on values for future priority-setting exercises. The tool aims to be inclusive and builds on what is currently reported in the literature. Although it is developed for nutrition research, we consider it equally useful to other types of research that rely on broad stakeholder involvement. As a working definition, we define values as general descriptions of an interest, or of what matters (e.g., “honesty”), that are not formulated in a measurable way (which we would define as a norm, e.g., “don't lie”).

Methodology

A 3-step approach was used to develop the guidance tool: 1) a mapping review of nutrition priority-setting exercises summarized the main characteristics of the existing research priority-setting exercises and reported values, 2) values reported in the manuscripts of the mapping review were identified via qualitative content analysis and organized in a tool, and 3) the tool was submitted for comments and feedback during a consultation round with the authors of the priority-setting exercises.

Step 1: mapping review of nutrition priority-setting exercises

The output of a mapping review that systematically identified priority-setting exercises (e.g., in research, policy, and implementation science) in the nutrition field was used for the present study. The detailed review protocol is available elsewhere (15). In summary, 5 online databases were screened including Medline (8 July 2017), ISI Web of Knowledge, Cochrane Library, and Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) (20 July 2016), and Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE) (30 August 2016). The initial syntax was developed in Medline with the use of the PICO (population, intervention, control, and outcomes) model (15). The developed search syntax included MeSH terms as well as free words in the title and abstract. It included the following terms (Delphi OR “Delphi technique” [MeSH] OR “Consensus” [MeSH] OR “voting” [all fields] OR priorities OR priority OR prioritisation OR prioritization OR “priority setting” OR setting priority OR setting priorities OR agenda) AND (“Diet, food and nutrition” [MeSH] OR nutrition OR dietary OR obese OR malnutrition OR nutrition disorders [field: Title/Abstract]). For the other databases, the search terms were adapted and modified, and included both text words and thesaurus terms. Grey literature documents were obtained through the use of the grey literature database Grey Literature Report (http://www.greylit.org), and targeted websites [Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN): www.scalingupnutrition.org; Thousand days: http://www.thousanddays.org; Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED): http://www.cohred.org; the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI): International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): www.ifpri.org/search?keyword=priorities; and USDA Interagency Committee on Human Nutrition: www.fnic.nal.usda.gov/surveys-reports-and-research/interagency-committee-human-nutrition-research] were searched. Moreover, external experts were consulted to identify further relevant websites and papers.

Title and abstract screening was performed for the databases’ results independently by 2 researchers (DH and RV) against the eligibility criteria, and a third researcher (AB, see Acknowledgments) was consulted in case of disagreement. Screening resulted in 133 eligible abstracts. The full report of the mapping review will be presented elsewhere. The grey literature search resulted in 9 documents and the experts’ consultation resulted in 2 papers.

As the present study focuses on nutrition research specifically, the eligible abstracts resulting from the mapping review were screened with “research” as an additional inclusion criterion as per protocol. DH screened the titles and abstracts again to identify papers focused on research. Of these manuscripts, 42 were read in full by DH and CL. Finally, 22 papers were excluded based on the exclusion criteria: 9 papers were not focused on nutrition, 5 were not research priorities, 4 papers had not used a formal priority-setting method, 2 were not in English, and 2 were only abstracts without a full text available. Nine grey literature documents were read in full, of which 4 were excluded (no explicit priority-setting method used). Two papers were added through expert consultation. The first was published after the search date in December 2016 (16). The second was not retrieved by search syntax, but was added for its relevance and importance in moving the research agenda (17). Disagreement was resolved by discussion. A third researcher (PK) was consulted in case of doubt. Data extraction of the study characteristics was performed by DH and included: the objective, methodology used, target population, number of experts involved, and funding sources. The country of affiliation of the first author was used as a proxy to determine where the priority setting was set. Owing to data saturation during qualitative data analysis, grey literature papers were not included in the qualitative analysis.

Step 2: guidance tool development

To extract values considered when setting nutrition research priorities, retrieved papers were analyzed qualitatively (18) with the use of NVivo Pro 11 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). Building on qualitative analysis, we have developed our own strategy of extracting values. Values were defined as general description of an interest/what matters through discussion guided by practices in medical ethics. The focus of the value is in general a nonmeasurable term in contrast to norms, which render values “measurable.” Moreover, a value during the analysis was seen as an action focused on achieving a sole purpose (i.e., an end) and not as an action carried out to achieve something further (i.e., means to an end). For example, “education” as a value is considered a means to achieve a higher quality of living. Hence, “quality of life” instead of “education” was considered as a value during the analysis.

As a first step, a preliminary set of values was extracted by 4 reviewers independently (CL, WP, DH, and NAB) using 3 randomly selected articles of the review. Second, the set of values was applied to a new set of 5 randomly selected articles, and the preliminary list of values was evaluated and revised until a consistent node list was reached. Finally, 2 researchers (DH and NAB) coded all the papers independently, including the 8 papers used in developing the preliminary list of values. The 2 researchers then discussed differences in coding until they reached a common agreement. To ensure correct coding, a medical ethicist (WP) trained DH and NAB on how to identify values. In addition, WP assisted in the structuring of the node trees, and provided advice in case of doubt. Finally, WP also performed sample checks to safeguard the accuracy of the coding.

During data comparison, similarities in the values found were resolved and the values were organized into higher categories and concepts via an iterative process. The list was simplified, i.e., passages that considered means to an end as a value were excluded. After this process of conceptualization and exclusion, the tool and list of values were further modified and simplified through frequent discussions between the reviewers (CL, WP, DH, and NAB) from March to September 2017 until consensus was reached. Consistency between the tool and its source documents was ensured via regular verification of the tool and the source texts.

Step 3: consultation round

A consultation process was conducted to assess perceptions of researchers regarding the proposed tool. The first and last authors of all the retrieved papers in step 2 were contacted to provide feedback on the tool and/or comment wording. The methodology used was based on the assumption that the first author leads the work under the supervision of the principal investigator, who is often placed as the last author (19). However, participants were encouraged to suggest other authors and scholars involved in nutrition priority setting that could provide valuable information. One email and 2 reminders were sent over a period of 90 d. The email was sent to 50 participants in total. Only those who replied positively were sent the tool for feedback.

Results

Characteristics of existing priority-setting exercises in nutrition research

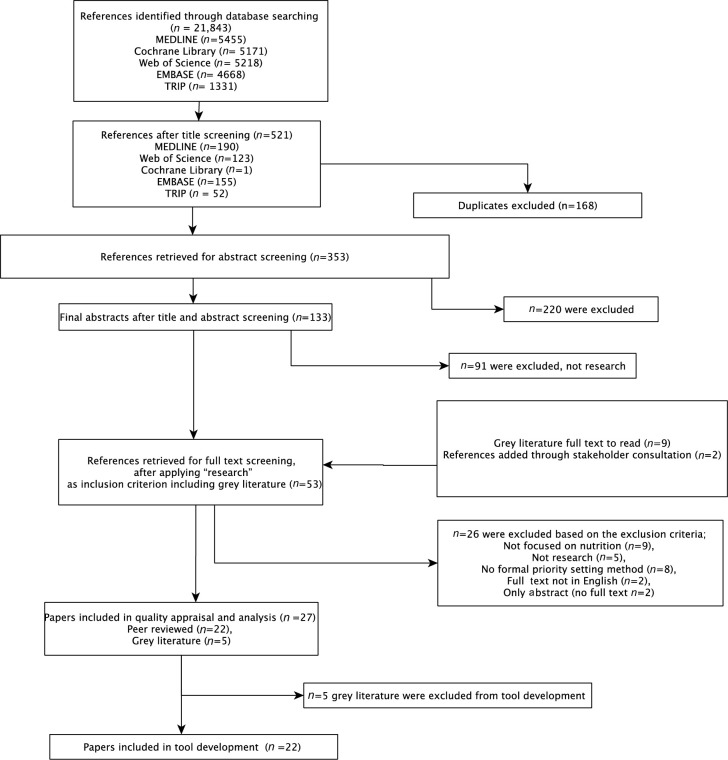

Of the 53 references identified (Figure 1), 27 papers were eligible for data extraction. Priority setting was used to prioritize nutrition research on a wide range of topics, i.e., obesity, wasting, stunting, malnutrition, and food systems, and for different age, populations, and ethnicity groups (Table 1). Diverse priority-setting methods were used, i.e., debates and discussions, Delphi method, and the CHNRI method. A large part (11/27, 40.7%) of the methods used were a combination of the aforementioned methods. CHNRI (20) was the most reported single method (4/27, 14.8%). All priority-setting exercises were led by research groups based in high-income countries, i.e., the United States (n = 16), 8 in Europe, 2 in Canada, 1 in Australia. Although all nutrition research priority-setting exercises were led by authors from high-income countries, 1 paper was implemented in Africa (21), and 2 others focused on minority ethnic groups in the United States (22, 23). Four papers (16, 24–26) reported international organizations as users of the results, without further specification.

FIGURE 1.

The output of the mapping review with research as an extra exclusion criterion. TRIP, Turning Research Into Practice.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of priority-setting exercises found in nutritional research1

| Reference | Priority methodology | Objective | Who is represented, # of experts | Target audience | Funding source | Follow-up of the results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggett (35), United Kingdom | Debate | Complementary feeding | International Pediatric Association and European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, n = not clear | Caregivers and policymakers, health professionals | The Infant Food Manufacturers | NA |

| Kumanyika et al. (23), United States | 2-d workshop | Obesity | African-American researchers, n = not clear | The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the NIH overall | The CDC | Follow-up of the workshop: research project ideas, funding proposals, position papers, and presentations, and further development of a focal point to continue the dialogue |

| Alley et al. (36), United States | Formal presentations and informal discussions | Causes and consequences of changes in body weight and composition over the aging process | Working Group, n = not clear | Researchers that address the questions mentioned in a special section of the Journal | NA | Call for papers that address these questions for a special section of the Journal, to be published in 2009 |

| Angood et al. (24), United Kingdom | CHNRI | Links between wasting and stunting | 18 of the 25 members of the existing TIG facilitated by the Emergency Nutrition Network took part in the survey, 16 completed the survey in full | International agencies, research funding bodies, donors, governments, and policymakers | USAID and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation | NA |

| Angood et al. (25), United Kingdom | CHNRI | The management of acute malnutrition | “Core group” of authors of the paper, n = 64 individuals participated in the survey | Governments, researchers, investors, international organizations, and national agencies | USAID/OFDA and Irish Aid | NA |

| Brown et al. (37), United States | CHNRI | Zinc research in child health | A group of 7 leading experts in the field of zinc research in child health | Not clear | CHNRI | Repeat periodically, possibly with a larger group and reference group of stakeholders, as new information becomes available |

| Buzzard and Sievert (38), United States | A conference; the results were circulated inviting extra comments. | Dietary assessment methodology | 41 speakers participated in the conference; 3 categories of invited presenters: 1) researchers working on research relating to dietary assessment methodology; 2) major users of dietary assessment methods; 3) policymakers; 19 of the 41 respondents gave comments for revisions of the lists of research priorities and recommendations | Not clear | University of Minnesota, WHO, and the FAO of the UN | Follow-up conference and ongoing forum to continue the process of updating and revising the priorities |

| Byrne et al. (39), Australia | Delphi technique (2 stages) | Longitudinal research on childhood and adolescent obesity questions | ACAORN; in Stage 2, delegates to the 2005 conference of the Australian Society for the Study of Obesity (a scientific organization of >600 medical practitioners, and other health care professionals) repeated the prioritization; Stage 1: 32 members of ACAORN; Stage 2: 39 of the 75 attendees contributed | Funding bodies, researchers, medical practitioners, and medical staff | ACAORN, an NHMRC Australian Public Health Training Fellowship, and an NHMRC Population Health Career Development Award | NA |

| Curtin et al. (40), United States | Delphi and a survey | Obesity | The HWRN, including family members, self-advocates, and policy leaders; 1st Delphi Round: n = 18/20 participants provided responses; a final vote via an online survey: 75% (15/20) of HWRN members and advisors ranked the 4 most important themes | HWRN | Health Resources and Services Administration Maternal and Child Health Bureau, NIH | Anticipation that the research agenda will be reviewed, re-evaluated, and refined as the Network evolves and matures: reaching out to the broader community of stakeholders to obtain their input |

| D'Andreamatteo et al. (41), Canada | Mixed method with 1) scoping review; 2) national online stakeholder survey; 3) key informant consultations in the form of interviews and online survey; 4) national workshop; and 5) triangulation of textual and quantitative data | Nutrition and mental health | Canadian Institute of Health Research, Dieticians of Canada, Canadian Mental Health Association, the University of British Columbia, the University of British Columbia Behavioral Research Ethics Board; n = 811 for national online stakeholder survey; n = 299 dieticians responded; n = 105 were invited either for an interview or to complete an online key-informant questionnaire, n = 79 responded; n = 16 participated in a national workshop | Dietitians | A Planning Grant of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; the Canadian Mental Health Association (Ontario), Dietitians of Canada, and the University of British Columbia, School of Nursing | Integrate the findings into further development of relevant content for the Practice-based Evidence in Nutrition database and Learning on Demand. Long-range plans entail outlining directives that formulate these findings into actions that target training, continued education, knowledge dissemination, as well as research, advocacy, and policy initiatives |

| Lachat et al. (21), Europe | Mixed methods: 1) review of institutions publishing nutrition research and type of research; 2) analysis of the perceptions of nutrition research by researchers, through 3 regional workshops; 3) assessment of the nutrition research priorities of stakeholders, and identification of research needs for environmental challenges | Malnutrition | SUNRAY consortium (academics from 4 European institutions, academics from 4 universities in Africa, an international nongovernmental organization, and an organization that funds research in SSA), researchers and policymakers in SSA, external stakeholders (i.e., government officials, UN agencies, nongovernmental organizations, bilateral donors, and the private sector), Department for International Development (UK), with the European Commission, and during a national workshop in Benin for Beninese and Togolese stakeholders, n = 117 participants from 40 countries in SSA attended the workshops; participants were principally senior researchers (52%) and policymakers (30%) in nutrition, the remaining participants (18%) were external stakeholders | NA | The European Commission | An annual course on evidence-based nutrition was piloted after SUNRAY and initiated the development of a knowledge network for evidence-based nutrition in Africa |

| McKinnon et al. (42), United States | Mixed methods: semistructured telephone interviews, followed by a meeting; a conference call was held by the National Cancer Institute after the meeting | Obesity | The participants represented a range of organizations, including academic research institutions, health organizations, private and federal research funding agencies, and state and federal government agencies; n = 27 participants and n = 11 nongovernment experts who had been invited to the meeting had a telephone interview | Knowledge generation partners and knowledge transfer/generation partners | No financial disclosures | Begin the work of building the evidence base for obesity policy, by evaluating the effects of next/existing policies |

| McPherson et al. (43), Canada | Mixed methods: a multistakeholder workshop with multiple methods | Disability and Obesity in Canadian Children Network | Researchers; trainees; front-line clinicians; parents; former clients with disabilities; community; partners; and decision makers; most invitees were Canadian; n = 38 invited attendees: 12 researchers; 4 trainees; 12 front-line clinicians; 3 parents; 1 former client with disabilities; 3 community partners; and 3 decision makers | NA | Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, and Bloorview Research Institute | DOCC-Net will be promoted across all Canadian provinces and disseminated through pan-Canadian organizations; international partners will also be encouraged to contribute their expertise to DOCC-Net and disseminate relevant information across their networks |

| Menon et al. (44), United States | Mixed methods: working group, e-consultation, conference, published literature (deliberations) | A nutrition implementation-focused framework | The New York Academy of Sciences, delivery science working group, multiple stakeholders including academia, intergovernmental organizations, nongovernmental organizations, the private sector, and the public sector; n = ∼54 respondents participated in the survey | NA | NA | NA |

| Nagata et al. (45), United States | Modified version of the CHNRI priority-setting method in 3 phases | Adolescent health in low- and middle-income countries | Experts were identified through 1) journal publications, membership of journal editorial boards, from lists of participants at WHO meetings and consultations, and by nominations from WHO departments; 2) participants at WHO meetings and consultations held in 2010–2015 and that were relevant to the 8 adolescent health areas through reports that were available on the WHO website and the WHO Index Medicus; 3) representatives of the WHO departments relevant to each health area to review the lists and nominate any additional key experts in their respective fields—overall, this resulted in 265 additional experts; combining the list of experts resulted in a total of n = 450 different individuals, n = 217 (48%) agreed to participate; in October 2015, n = 15 external experts joined the authors and other WHO staff in a meeting at which the methods and preliminary findings were discussed before they were finalized; n = 142 experts submitted questions; scored questions by health area (n = 130) | Donors, program managers, and researchers to stimulate and develop research in adolescent health | US Agency for International Development and the Mary Duke Biddle Clinical Scholars Program, Stanford University | NA |

| Ohlhorst et al. (46), United States | Mixed methods: in 2011 the ASN reached out to experts; then, it convened a Working Group to determine the nutrition research needs and share them via ASN's member newsletter | The prevention and treatment of nutrition-related diseases | ASN's Public Policy Committee, scientists and researchers representing a cross-section of the Society's membership; the characteristics of the conference attendees and newsletter members are not clear; in September 2011, ASN's 75 leaders developed a draft list of nutrition research needs; in February 2012, ASN convened a Working Group; workshop was held with nearly n = 250 attendees; to inform and seek input from (n = 5000) members (who didn't attend the annual meeting or workshop) the results were shared via ASN's newsletter | Stakeholders with differing areas of expertise to establish the evidence-based nutrition guidance and policies | NA | NA |

| Ramirez et al. (22), United States | A modified 3-round web Delphi survey | To reduce and prevent Latino childhood obesity | Females and predominantly Hispanic/Latino followed by Whites, African Americans, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and other ethnicities; most participants were academicians or researchers, followed by health educators or administrators or managers and clinicians, and public health workers; Delphi respondents were located in 31 US states; first Delphi round: 579 invitations were sent, n = 177 individuals responded; second Delphi round: 103 people completed the survey, of whom n = 57 had completed Round 1 (55.3%) and n = 46 were new participants (44.7%); third Delphi round: 194 people completed surveys, of which n = 93 completed a survey in Rounds 1 and 2 (47.9%) and n = 101 were new recruits (52.1%) from the Salud America! network | Investigators, educators, health care providers, and communities to collaborate on childhood obesity prevention and control | RWJF | Results will guide the development of a call for proposals to support 20 pilot projects aimed at identifying effective prevention and control strategies, encouraging partnerships and collaborations; it also will guide others in developing new and innovative ecologic interventions focusing on the identified research areas and priorities to fight Latino childhood obesity |

| Ward et al. (47), United States | Mixed methods: meeting, conference, online survey, voting | Identify the key issues related to obesity prevention research in ECE settings | Faculty from a variety of universities, representatives from multiple foundations interested in child obesity prevention, delegates from multiple branches of the NIH and the US Department of Health and Human Services, and other key leaders in ECE; not clear how many were initially invited to the conference, n = 43 attendees; among the 43, 44% completed the follow-up online survey to identify research priorities | Funders, both federal agencies (such as (NHLBI, CDC, and USDA) and foundations (RWJF, American Health Association, and others) | The NHLBI and Office of Behavioural and Social Sciences Research; the RWJF ’s Healthy Eating Research and Active Living Research programs, the Nemours Foundation, and the Altarum Institute; University of North Carolina's Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, a member of the Prevention Research Centers Program of the CDC | NA |

| Pratt et al. (48), United States | Workshop | Childhood obesity prevention and treatment | Leaders and representatives from public and private academic and medical institutions with expertise in a variety of health specialties and research methodology, staff from the NIH and the USDA, n = NA | Investigators and funding agencies in setting research agendas for childhood obesity prevention and treatment | NA | NA |

| Wu et al. (49), United States | Mixed methods: 1) a comparative effectiveness review and meta-analysis; 2) a 3-round Delphi process with the use of a web-based assessment tool | Childhood obesity | A modified Delphi process with 6 expert stakeholders with potential interest in childhood obesity prevention such as parents, researchers, and representatives from government, public agencies, n = 6 | Researchers and funding agencies | The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality | NA |

| Haddad et al. (16), United Kingdom | Conclusion from compiling a report commissioned by the Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition | Food systems | n = NA | Researchers, funders, governments, delegates to the G20 and G7 2017 meeting | NA | NA |

| Black et al. (17), United States | NA | To reassess the problems of maternal and child undernutrition | Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group, Series Advisory Committee, n = NA | NA | Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation | NA |

| Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and UK Aid (50), United States | Mixed methods: 1) a review of existing evidence of agriculture nutrition linkages and explored research; 2) consultations with leading researchers in the field to solicit ideas of where knowledge gaps still exist | Nutrition-sensitive agriculture | Not clear, but they state consulting leading researchers, n = NA | Researchers, policymakers, and program implementers | UK Aid, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation | This white paper serves as the basis for a soon-to-be-announced Request for Applications from the UK Department for International Development and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation |

| Commission of the European Communities (51), Europe | Not clear | Contribute to reducing ill health due to poor nutrition, overweight, and obesity | Commission of the European Communities, n = NA | Member states, private actors, international cooperation | The European Commission | Collaborate with the WHO to develop a nutrition and physical activity surveillance system for the EU-27; a review of obesity status progress in 2010; a Green Paper on urban transport in 2007, followed by an Action Plan in 2008; publish guidance on sustainable urban transport plans; a White Paper on Sport; in 2007 the Commission will finance a study looking at the relation between obesity and socioeconomic status with a view to considering the most effective interventions |

| The Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science (52), United States | Mixed methods: Academy of Sciences Group identified 3 critical “Focus Areas” topics, Focus Area Working Groups developed critical gaps in knowledge, a web-based consultation for feedback followed, the conclusion was presented during a conference | Malnutrition | The Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science, academic and nonprofit researchers, WHO, Humanities Global Development; n = 55 researchers, organized in Focus Area Working Groups, developed more than 20 critical gaps in knowledge from the broad Focus Areas; a web-based consultation secured feedback from >100 stakeholders in the nutrition science community—from both developed and developing countries—on these critical areas | The research community and stakeholders in the field of nutrition towards focusing on pressing research needs | The New York Academy of Sciences in partnership with the Mortimer D. Sackler Foundation | Specific research proposals focusing on the gaps identified in this agenda will be developed; the Sackler Institute will hold working sessions and symposiums that will bring together key stakeholders to support these projects in nutritional, agricultural, and environmental sciences; public health; and policy |

| Byrne and Daniel (53), Europe | NA | Sustainable food and nutrition security | Joint Programming Initiative: a healthy diet for a healthy life, n = not clear | All age groups | Joint Programming Initiative | Implementation Plan every 2–3 y in which the actions and activities to be carried out in the next years are presented |

| The AFRESH Project (54), Europe | NA | I—Tackling avoidable diet- and lifestyle-related noncommunicable diseases; II—Implementation of the European “Lisbon strategy” at the regional level | The AFRESH Project: 16 stakeholders from 8 European regions work together, n = NA | Enterprises, research organizations, and regional authorities; European population | The European Union's Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development | NA |

| UNSCN (26), Europe | A review of global commitments and goals, recommendations in the 2014 Global Nutrition Report, and stakeholder consultations | Framework for UN action in response to global and country nutrition goals for the years to come | The UN agencies with a key mandate in nutrition: FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO; n = NA | Agencies and interagency teams at global, regional, and country levels | Flemish government | NA |

1ACAORN, The Australian Child and Adolescent Obesity Research Network; AFRESH, Activity and Food for Regional Economies Supporting Health; CHNRI, Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative; DOCC-Net, Disability and Obesity in Canadian Children Network; ECE, early care and education; HWRN, Healthy Weight Research Network; IFAD, International Fund for Agricultural Development; NA, not available; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NHMRC, National Heart and Medical Research Council; OFDA, Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance; RWJF, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa; TIG, Technical Interest Group; UNSCN, United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition.

A considerable share (n = 11, 40.7%) of the papers did not describe stakeholders represented and/or invited clearly. More than half of the papers (n = 14, 51.9%) did not describe follow-up activities of the proposed priorities and, of the 27 papers, 5 (18.5%) did not report the source of funding.

Guidance tool development

Values found in the priority-setting papers (Table 2) are grouped in 8 clusters, i.e., understanding, impact, feasibility, efficacy, equity, soundness, sustainability, and novelty. In line with guidance on how to address research waste at large (9), research questions in Table 2 are initially classified as either purely fundamental or applied. Fundamental research questions are defined as questions that attempt to increase our understanding of the topic, whereas applied research questions are defined as questions to be implemented in practice.

TABLE 2.

Values found in the priority-setting exercises in nutrition research along the priority-setting cycle

| Value | Pure basic research | Pure applied research |

|---|---|---|

| Impact | − Dissemination | – Commitment |

| − Research translation | – Effectiveness | |

| − Timeliness | – Acceptability | |

| − Answerability (21, 23–25, 35–42, 44–49) | – Community concerns and demands | |

| – Accessibility | ||

| – Affordability | ||

| − Education prevention (16–17, 21–25, 35, 37–38, 40–42, 44–48) | ||

| Understanding of the problem | – Long-term consequences | — |

| – Burden | ||

| – Comprehensiveness (Global) | ||

| – Quantification | ||

| – Specificity (16–17, 21–25, 35–49) | ||

| Feasibility | Research infrastructure (16, 21, 23–25, 36, 38, 40, 42–43, 46–47) | Infrastructures |

| – Deliverability | ||

| – Expertise | ||

| – Funding | ||

| – Network (16–17, 21–25, 35, 37–38, 40–49) | ||

| Efficacy—cost effectiveness | — | Applied research is carried out in the most cost-effective way (24–25, 41–42, 46–48) |

| Equity | Equal opportunities for all ethnic groups to conduct research, equal inclusion of all ethnic groups and vulnerable groups in research addressing nutrition problems (23, 43) | Equal opportunities for all ethnic groups to implement research, equal inclusion of all ethnic groups and vulnerable groups in research implementation addressing nutrition problems (23–25, 35, 37, 40–41, 43, 45, 47–49) |

| Sound methods | – Measurability | Accountability |

| – Validity | Safety (do no harm) (16, 22, 24–25, 35–37, 44, 48) | |

| – Appropriateness | ||

| – Reliability | ||

| – Standardization of definitions and cutoff | ||

| – Representative | ||

| – Participatory research | ||

| – Social grounding and perceptions | ||

| – Transparency (16, 21–25, 35, 37–44, 47–48) | ||

| Sustainability | Doing research to evaluate and monitor the implemented interventions (21, 47) | Respect for environment |

| Adaptability | ||

| Prevention | ||

| Capacity building | ||

| Education | ||

| Evaluation and monitoring (16, 21–25, 35, 37–40, 42–45, 47–49) | ||

| Novelty | Exploring new methods, new approaches, and new interventions (16, 22–24, 37–40, 43–44, 46–49) |

The result of the qualitative analysis served as the basis to formulate the tool (Table 3). The categorization of pure fundamental and pure applied research was removed to enhance clarity. In an attempt to make a simple tool and limit the burden on the users, the 8 clusters found in Table 2 were simplified through frequent discussions between the reviewers (CL, WP, DH, and NAB) until consensus was reached upon the 3 values: “feasibility”, “impact”, and “accountability”. Each of the 3 categories has respective aspects to be considered with 2 columns to fill: relevance of the value for the stakeholders involved (from low to high, as well as “not applicable”) and decision explanation/points to consider to justify the relevance selected and to highlight certain aspects that must be considered for specific values. Moreover, each category has an empty row, to be determined, in case priority setters have the need to consider more aspects, and an empty column for more values.

TABLE 3.

Value-oriented guidance tool for priority-setting exercises1

| Value | Relevance | Decision/points to consider | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEASIBILITY | |||

| Answerable | The research hypothesis is both clear and has the potential to be answered |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Realistic | The infrastructure to undertake the research is considered (e.g., funding, expertise, sufficient prior knowledge, etc.) |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| The infrastructure necessary to deliver the applied research is considered (e.g., funding, expertise, network, etc.) |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

||

| Supported | The necessary stakeholders (e.g., government, funders, researchers) commit to the implementation |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| TBD | (Empty row to add a value) |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| IMPACT | |||

| Relevant | The research advances scientific knowledge and/or practice (e.g., definition, burden, scope) and is addressed at a suitable moment in time e.g., there is a sense of urgency |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Practice-oriented | Translation and implementation of research results are considered |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Accessible | The accessibility of the applied research (e.g., affordability, proximity, reachability) by the target population is maximized |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Effective | The research has the potential to achieve the desired outcomes |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Context-sensitive | Social or cultural disapproval by the target population and demands and preferences of the target population are taken into account |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Specific | Research is sufficiently targeted/focused to certain problems/populations/contexts |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Comprehensive | A wide range of relevant elements (scope, long-term effects, contextual approach) are considered in the research |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| If applied, different approaches including preventive approaches are considered |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

||

| Empowering | The pure research enables the target population to promote their own health (e.g., through prevention, improved capacities for self-care) |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Innovative | The research topics go beyond traditional methods, approaches, and thinking around the topic |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| TBD | (Empty row to add a value) |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| ACCOUNTABILITY | |||

| Reported | Dissemination of research findings beyond the research team is anticipated (e.g., publication, public presentation) |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Transparent | Research data, methods, and evidence are publicly reported |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Sound | The research uses appropriate, valid, and reliable methods |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Environmental friendly | The research takes into account environmental sustainability and minimizes environmental harm |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Cost-effective | Efficient use of resources to achieve the maximum impact |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Sustainable | The applied research targets long-term improvements (e.g., capacity-building, adaptability) |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| Quality assured | The research has a monitoring and evaluation plan |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| The applied research has a monitoring and evaluation plan | |||

| Inclusive | The research adopts participatory approaches in which different stakeholders are represented |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

|

| If it is applied research, it is not increasing inequity in society and seeks to maximize fairness | |||

| TBD | (Empty row to add a value) |

Low Low  Medium Medium  High High  NA NA |

1NA, Not Applicable; TBD, To Be Determined.

The tool draws attention to the broad definitions and criteria for values found in the literature. It encourages those involved in priority settings to go beyond the simple definition of what are feasibility, impact, and accountability and to consider a range of concepts much larger than a simple definition of practicality, pure effect, and responsibility. For instance, feasibility includes the ability of the proposed priority list to be answerable, realistic, and supported (Table 3). Impact looks more comprehensively at other dimensions than effectiveness, including relevance, innovation, empowerment, comprehensiveness, specificity, sensitivity, accessibility, and translation. Accountability is represented as a comprehensive category, emphasizing that those involved in setting priorities have a responsibility to consider what is already available as well as emerging challenges when doing research. The tool hence fosters reflection on sustainability, environmentally conscious approaches, and inclusiveness when setting priorities in future. We developed a manual to assist readers when using the tool (27). An MS word version of Table 3 can be downloaded from supplementary material.

Consultation round

Out of the 17 authors who replied to participate in the consultation round, 7 authors provided feedback, representing scholars and leading agencies in nutrition including the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Five authors agreed to participate but did not provide input. Five authors declined to participate: 3 owing to time constraints, and 2 reported not having the right expertise.

In response to the feedback received, the layout of the tool was simplified. The final tool contains 3 categories of values for all types of research. The distinction between fundamental and applied research was omitted as the results from the consultation rounds indicated confusion with the 2 categories. As a result, additional values relevant only for applied research were clarified, but mentioned alongside values relevant for both fundamental and applied research. In addition, relevance rankings were simplified to low, medium, and high relevance (as opposed to our original 5 level options). Other comments related to rewording of sentences and to logical ordering of values in the table were considered. One expert suggested applying each value to each prioritized question instead of to the exercise as a whole. The final version of Table 3 was sent to COHRED for external review.

Discussion

The present research adds to the larger body of work considering how values shape agendas in nutrition. Attention towards solving malnutrition and improving nutrition has increased lately with a Decade of Action on Nutrition declared by the UN General Assembly in 2016 (28). Some work has been done to embed nutrition agenda setting for policy considerations, e.g., Nutrition for Growth (29), and the Mainstreaming Nutrition Initiative which considered the importance of values, strategies, and actions in several countries (30). The findings of our review call for more consistency between the values used and the reporting of the priority-setting exercises. For instance, although the majority of the papers valued impact, there was an apparent lack of transparency in the reporting of the follow-up plan, and outcome processes of the priority-setting exercises.

The tool does not assess the importance of specific values as such, nor does it serve as a quality stamp for research priority exercises. Rather, it aims to trigger explicit and open-ended reflection on research, in which values can be adopted or forfeited, but not neglected. In this sense, it provides guidance and opportunity to reflect on the criteria chosen to rank the priority options proposed. The tool is proposed to complement existing priority-setting methods (13, 20, 31, 32). For instance, CHNRI proposes a pre-established list of criteria to rank research questions, whereas the present tool provides guidance and opportunity to take time and reflect on the criteria chosen to rank the priority options proposed.

The tool serves a double purpose. First, the tool provides a set of values that can be systematically discussed in the process of research priority setting. Second, it can also serve as a reporting instrument to increase transparency on how values were considered in the process of priority setting. As such, the guidance tool improves rational use of limited resources for research. The tool aims to draw attention to the accountability of those involved in setting research priorities and ensures due attention to, and transparency in, values during this process. However, like any other instrument, the proposed tool will require further testing before its potential to improve priority setting is fully assessed (33).

Because the tool is built around the values that were already explicitly or implicitly reported in existing priority-setting exercises in nutrition research, it is applicable to different research types and topics. By extension, it is also applicable to other fields of biomedical research.

As values are by definition open to interpretation, the discussion on their relevance and relative priority over others is left to the discretion of those setting priorities. Even with considerable disagreement on the definition (e.g., what is meant with justice?) or the implications (e.g., what does a just intervention require?) of values, it still makes sense to explicitly consider all relevant values in priority-setting exercises. In this way, the proposed tool facilitates the process of eliciting a comprehensive debate ensuring that relevant values are not ignored and that research agendas are not solely inspired by coincidence, practicality, or hype, rather than by a profound consideration of what matters most. During the consultation round, 1 expert commented on the level at which the tool should be applied, proposing to apply it for every question at hand. Although this was a relevant suggestion, applying the tool to every research option would add considerable burden to those involved in the discussions. We therefore propose to apply the tool on the priority-setting exercise as a whole, as it is essentially meant to be a tool for debate and discussion.

Adequate consideration of values during the priority-setting exercise requires proper preparation and methodological considerations. Box 1 summarizes the conditions that need to be fulfilled before starting the research prioritization. These conditions correspond largely with previous recommendations to reduce research waste when setting research priorities (9).

Box 1. Prerequisites for initiating research priorities exercise

Before setting priorities, consider the following:

– Is enough known on the topic? Consider carrying out a systematic review of literature to understand the options discussed (e.g., disease burden)

– Can additional information (e.g., current developments) be provided to set priorities for research?

– Are the background information and rationale communicated adequately to all priority-setting participants (e.g., briefing, training participants)?

– Are participants informed sufficiently about the procedures and use of results of the priority-setting exercise? Should participants of the priority-setting exercise complete an informed consent? Is the involvement of participants recognized?

Although potentially eligible papers in informal and unpublished reports within the context of institutional settings for example were not considered, we still noted that all of the research-setting exercises reviewed were conducted in high-income countries. Despite the high needs and limited resources, it remains unclear how, and if, priority-setting exercises for nutrition research in low- and middle-income countries are done. This complicates inclusive and equitable approaches to global challenges in nutrition, and calls for more research to understand how the research agenda is being set in low- and middle-income countries. Equitable consideration of priorities from local stakeholders compared with those of international researchers or donors is a concern (34).

We acknowledge that the proposed tool requires testing and evaluation by various stakeholder groups to ensure its correct understanding and application. Moreover, the tool has been built and developed by researchers based on research output from high-income countries. Hence, it does not necessarily reflect the values of stakeholders in low- and middle-income countries, and further research is needed to understand values in this context. Further investigations are needed to assess understanding, applicability, and legitimacy of the tool when setting research priorities in low- and middle-income countries. We are encouraging contributions from groups who work on research prioritization and are willing to apply the tool in their process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sara Abassbhay, MSc (intern at Ghent University) for double checking Table 1 results, and Prof Andrew Booth for support in abstract screening for the mapping review. We thank the following people for their feedback on the guidance tool: Lawrence Haddad, Executive Director, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN); Carla D'Andreamatteo, RD, MSc, The Food Lady; Sarah D Ohlhorst, MS, RD, Senior Director of Advocacy and Science Policy, American Society for Nutrition (ASN), Rockville, MD; Shelly Sundberg, Senior Program Officer, Nutrition, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Carel IJsselmuiden, COHRED. The authors’ contributions were as follows—CL, DH, and WP: conceptualization; DH and RV: developed search strategy; DH: data curation; DH, NAB, and WP: qualitative data analysis; CL, DH, NAB, PK, and WP: drafting the tool; CL and WP: supervision; CL and DH: wrote the first draft of the manuscript; NAB, PK, WP, and RV: contributed to the writing of the manuscript; and all authors: agree with the manuscript's results and conclusions, have read and approved the final version of the paper, and confirm that they meet ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Notes

Perspective articles allow authors to take a position on a topic of current major importance or controversy in the field of nutrition. As such, these articles could include statements based on author opinions or point of view. Opinions expressed in Perspective articles are those of the author and are not attributable to the funder(s) or the sponsor(s) or the publisher, Editor, or Editorial Board of Advances in Nutrition. Individuals with different positions of the topic of a Perspective are invited to submit their comments in the form of a Perspectives article or in a Letter to the Editor.

Supported by a scholarship from the Schlumberger Foundation's Faculty for the Future Program (www.fftf.slb.com) (to DH).

Author disclosures: CL, WP, and PK are coauthors of one of the priority-setting exercises: Developing a sustainable nutrition research agenda in sub-Saharan Africa—findings from the SUNRAY project. PLoS Med 2014;11(1):e1001593. DH's funding had no role in the conduct of this study or in the content of this article. NAB and RV, no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Table 3 as MS word table is available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article, and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/advances/.

References

- 1. GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390(10100):1151–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sibbald SL, Singer PA, Upshur R, Martin DK. Priority setting: what constitutes success? A conceptual framework for successful priority setting. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Viergever RF, Olifson S, Ghaffar A, Terry RF. A checklist for health research priority setting: nine common themes of good practice. Health Res Policy Syst 2010;8:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grill K, Dawson A. Ethical frameworks in public health decision-making: defending a value-based and pluralist approach. Health Care Anal 2017;25(4):291–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark T. The policy process: a practical guide for natural resource professionals. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martin D, Singer P. A strategy to improve priority setting in health care institutions. Health Care Analysis 2003;11(1):59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cruz Rivera S, Kyte DG, Aiyegbusi OL, Keeley TJ, Calvert MJ. Assessing the impact of healthcare research: a systematic review of methodological frameworks. PLoS Med 2017;14(8):e1002370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Development Initiatives Global Nutrition Report 2017: nourishing the SDGs. Bristol, United Kingdom: Development Initiatives; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gulmezoglu AM, Howells DW, Ioannidis JPA, Oliver S. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 2014;383(9912):156–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bornmann L. Measuring the societal impact of research: research is less and less assessed on scientific impact alone—we should aim to quantify the increasingly important contributions of science to society. EMBO Rep 2012;13(8):673–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lachat C, Hawwash D, Ocke MC, Berg C, Forsum E, Hornell A, Larsson C, Sonestedt E, Wirfalt E, Akesson A et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology-nutritional epidemiology (STROBE-nut): an extension of the STROBE Statement. PLoS Med 2016;13(6):e1002036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gruskin S, Daniels N. Process is the point: justice and human rights: priority setting and fair deliberative process. Am J Public Health 2008;98(9):1573–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Montorzi G, de Haan S, IJsselmuiden C. Priority setting for research for health: a management process for countries. In: COHRED manuals and guidelines series Geneva, Switzerland: Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nasser M, Ueffing E, Welch V, Tugwell P. An equity lens can ensure an equity-oriented approach to agenda setting and priority setting of Cochrane Reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66(5):511–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Verstraeten R, Hawwash D, Lachat C, Bonn N, Pinxten W, Gillespie S, Holdsworth AB. Nutrition prioritisation: three inter-dependent (mapping, methodology, and ethics) systematic review outputs. PROSPERO 2016:CRD4201604380. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haddad L, Hawkes C, Webb P, Thomas S, Beddington J, Waage J, Flynn D. A new global research agenda for food. Nature 2016;540(7631):30–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham-McGregor S, Katz J, Martorell R et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013;382(9890):427–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62(1):107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao DZ, Strotmann A. Counting first, last, or all authors in citation analysis: a comprehensive comparison in the highly collaborative stem cell research field. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 2011;62(4):654–76. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rudan I, Gibson JL, Ameratunga S, El Arifeen S, Bhutta ZA, Black M, Black RE, Brown KH, Campbell H, Carneiro I et al. Setting priorities in global child health research investments: guidelines for implementation of CHNRI method. Croat Med J 2008;49(6):720–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lachat C, Nago E, Roberfroid D, Holdsworth M, Smit K, Kinabo J, Pinxten W, Kruger A, Kolsteren P. Developing a sustainable nutrition research agenda in sub-Saharan Africa—findings from the SUNRAY project. PLoS Med 2014;11(1):e1001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramirez AG, Chalela P, Gallion KJ, Green LW, Ottoson J. Salud America! Developing a national Latino childhood obesity research agenda. Health Educ Behav 2011;38(3):251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kumanyika SK, Gary TL, Lancaster KJ, Samuel-Hodge CD, Banks-Wallace J, Beech BM, Hughes-Halbert C, Karanja N, Odoms-Young AM, Prewitt TE et al. Achieving healthy weight in African-American communities: research perspectives and priorities. Obes Res 2005;13(12):2037–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Angood C, Khara T, Dolan C, Berkley JA, WaSt Technical Interest Group Research priorities on the relationship between wasting and stunting. PLoS One 2016;11(5):e0153221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Angood C, McGrath M, Mehta S, Mwangome M, Lung'aho M, Roberfroid D, Perry A, Wilkinson C, Israel AD, Bizouerne C et al. Research priorities to improve the management of acute malnutrition in infants aged less than six months (MAMI). PLoS Med 2015;12(4):e1001812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. UNSCN United Nations Global Nutrition Agenda (UNGNA v. 1.0). 1st ed 2015. Available from: http://scalingupnutrition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/UN-Global-Nutrition-Agenda-2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hawwash D, Pinxten W, Bonn AN, Lachat C. Tool to consider values when setting research priorities: manual for use. 2018[cited 2018 Jan 15]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-8544974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baker P, Hawkes C, Wingrove K, Demaio AR, Parkhurst J, Thow AM, Walls H. What drives political commitment for nutrition? A review and framework synthesis to inform the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(1):e000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nutrition for Growth. 2016 [cited 2018 Apr 6]. Available from: https://nutritionforgrowth.org. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA, Gervais S, Hoey L, Menon P, Ngo T, Stoltzfus RJ, Ahmed AM, Ahmed T. Nutrition agenda setting, policy formulation and implementation: lessons from the Mainstreaming Nutrition Initiative. Health Policy Plan 2012;27(1):19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Okello D, Chongtrakul P, The COHRED Working Group on Priority Setting A manual for research priority setting using the ENHR Strategy. Geneva, Switzerland: Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ghaffar A, Collins T, Matlin SA, Olifson S. The 3D combined approach matrix: an improved tool for setting priorities in research for health. Geneva, Switzerland: Global Forum for Health Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fudickar A, Horle K, Wiltfang J, Bein B. The effect of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist on complication rate and communication. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012;109(42):695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chu KM, Jayaraman S, Kyamanywa P, Ntakiyiruta G. Building research capacity in Africa: equity and global health collaborations. PLoS Med 2014;11(3):e1001612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aggett PJ. Research priorities in complementary feeding: International Paediatric Association (IPA) and European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) workshop. Pediatrics 2000;106(5):1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alley DE, Ferrucci L, Barbagallo M, Studenski SA, Harris TB. A research agenda: the changing relationship between body weight and health in aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63(11):1257–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brown KH, Hess SY, Boy E, Gibson RS, Horton S, Osendarp SJ, Sempertegui F, Shrimpton R, Rudan I. Setting priorities for zinc-related health research to reduce children's disease burden worldwide: an application of the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative's research priority-setting method. Public Health Nutr 2009;12(3):389–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Buzzard IM, Sievert YA. Research priorities and recommendations for dietary assessment methodology. First international conference on dietary assessment methods. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59(1 Suppl):275S–80S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Byrne S, Wake M, Blumberg D, Dibley M. Identifying priority areas for longitudinal research in childhood obesity: Delphi technique survey. Int J Pediatr Obes 2008;3(2):120–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Curtin C, Must A, Phillips S, Bandini L. The Healthy Weight Research Network: a research agenda to promote healthy weight among youth with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities. Pediatr Obes 2017;12(1):e6–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. D'Andreamatteo C, Davison KM, Vanderkooy P. Defining research priorities for nutrition and mental health: insights from dietetics practice. Can J Diet Pract Res 2016;77(1):35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McKinnon RA, Orleans CT, Kumanyika SK, Haire-Joshu D, Krebs-Smith SM, Finkelstein EA, Brownell KD, Thompson JW, Ballard-Barbash R. Considerations for an obesity policy research agenda. Am J Prev Med 2009;36(4):351–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McPherson AC, Ball GD, Maltais DB, Swift JA, Cairney J, Knibbe TJ, Krog K, Net D. A call to action: setting the research agenda for addressing obesity and weight-related topics in children with physical disabilities. Child Obes 2016;12(1):59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Menon P, Covic NM, Harrigan PB, Horton SE, Kazi NM, Lamstein S, Neufeld L, Oakley E, Pelletier D. Strengthening implementation and utilization of nutrition interventions through research: a framework and research agenda. Annals N Y Acad Sci 2014;1332:39–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nagata JM, Ferguson BJ, Ross DA. Research priorities for eight areas of adolescent health in low- and middle-income countries. J Adolesc Health 2016;59(1):50–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ohlhorst SD, Russell R, Bier D, Klurfeld DM, Li Z, Mein JR, Milner J, Ross AC, Stover P, Konopka E. Nutrition research to affect food and a healthy life span. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98(2):620–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ward DS, Vaughn A, Story M. Expert and stakeholder consensus on priorities for obesity prevention research in early care and education settings. Child Obes 2013;9(2):116–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pratt CA, Stevens J, Daniels S. Childhood obesity prevention and treatment: recommendations for future research. Am J Prev Med 2008;35(3):249–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wu Y, Lau B, Bleich S, Cheskin L, Boult C, Segal J, Wang Y. Future research needs for childhood obesity prevention programs. In: Future research needs papers Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Evidence-based Practice Center; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and DFID (UK Department for International Development) Agriculture for Improved Nutrition: A Future Research Agenda. 2017. London: Agriculture, Nutrition and Health Academy; https://anh-academy.org/sites/default/files/Agriculture%20for%20Improved%20Nutrition-A%20Future%20Research%20Agenda.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Commission of the European Communities White paper on a strategy for Europe on nutrition, overweight and obesity-related health issues. 2007. Brussels: http://ec.europa.eu/health/archive/ph_determinants/life_style/nutrition/documents/nutrition_wp_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 52. The Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science A Global Research Agenda for Nutrition Science. Outcome of a collaborative process between academic and non-profit researchers and the World Health Organization. 2013;17 New York, http://www.nutritionresearchagenda.org. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Byrne P, Daniel H. Strategic research agenda 2012–2020 and beyond: Joint Programming Initiative: a healthy diet for a healthy life. 2nd ed 2015. Den Haag, http://www.healthydietforhealthylife.eu. [Google Scholar]

- 54. AFRESH solutions–a Joint Action Plan for Health. European project AFRESH: Activity and food for regional economies supporting health. 2013. Montpellier, France: http://www.afresh-project.eu/the-project/documents. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.