ABSTRACT

Nutrient profile (NP) models, tools used to rate or evaluate the nutritional quality of foods, are increasingly used by government bodies worldwide to underpin nutrition-related policies. An up-to-date and accessible list of existing NP models is currently unavailable to support their adoption or adaptation in different jurisdictions. This study used a systematic approach to develop a global resource that summarizes key characteristics of NP models with applications in government-led nutrition policies. NP models were identified from an unpublished WHO catalog of NP models last updated in 2012 and from searches conducted in different databases of the peer-reviewed (n = 3; e.g., PubMed) and gray literature (n = 15). Included models had to meet the following inclusion criteria (selected) as of 22 December 2016: 1) developed or endorsed by governmental or intergovernmental organizations, 2) allow for the evaluation of individual food items, and 3) have publicly available nutritional criteria. A total of 387 potential NP models were identified, including n = 361 from the full-text assessment of >600 publications and n = 26 exclusively from the catalog. Seventy-eight models were included. Most (73%) were introduced within the past 10 y, and 44% represent adaptations of ≥1 previously built model. Models were primarily built for school food standards or guidelines (n = 27), food labeling (e.g., front-of-pack; n = 12), and restriction of the marketing of food products to children (n = 10). All models consider nutrients to limit, with sodium, saturated fatty acids, and total sugars being included most frequently; and 86% also consider ≥1 nutrient to encourage (e.g., fiber). No information on validity testing could be identified for 58% of the models. Given the proliferation of NP models worldwide, this new resource will be highly valuable for assisting health professionals and policymakers in the selection of an appropriate model when the establishment of nutrition-related policies requires the use of nutrient profiling.

Keywords: food quality, healthfulness, healthy food, unhealthy food, nutrient profiling, nutritional quality, nutrition policy, public health, systematic review, validation

Introduction

Worldwide, authoritative bodies increasingly recognize the value of the use of objective, transparent, and reproducible methods to evaluate the nutritional quality of foods and nonalcoholic beverages (henceforth foods) to support a vast array of nutrition-related policies (1–4). Nutrient profiling, defined by the WHO as “the science of classifying or ranking foods according to their nutritional composition for reasons related to preventing disease and promoting health” (5, 6), aims to meet this need. Nutrient profile (NP) models utilize algorithms that take into consideration the amounts or the presence of nutrients and other related food components (e.g., whole grain) in a food product to characterize its degree of “healthfulness” through either numerical scores (e.g., from 1 to 100, where 100 represents the highest nutritional quality) or more qualitative classifications (e.g., eligible/not eligible to carry a logo designating a “better-for-you” product) (7).

Although NP models characterize foods as opposed to diets, they represent a way to improve dietary choices, and hence overall dietary patterns, through a variety of applications in the field of public health (1). Such applications include, but are not limited to, the underpinning of food labeling schemes [e.g., voluntary or mandatory front-of-pack (FOP) nutrition labeling schemes to assist consumers in their food-selection decisions], the regulation of health and nutrition claims (e.g., to identify which food products are eligible to carry a specific claim), restrictions on the commercial marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children, food procurement regulations or food quality standards for public institutions (e.g., schools, health facilities, government facilities), the underpinning of food taxes or subsidies for producers, manufacturers, retailers, or consumers, and nutritional surveillance (i.e., evaluation of changes across time in the nutritional quality of the food supply in a given population) (2–4).

A draft catalog of existing NP models and its accompanying report prepared by Mike Rayner and colleagues, which was last updated in November 2012, indicated that NP models are increasingly being developed worldwide [Nutrient Profiling Catalogue of Nutrient Profile Models: Summary Report; 4 March, 2013 (unpublished report prepared for the WHO); hereafter cited as draft catalog (2013); available from one of the authors (MR) upon request]. When compared with a review of NP models published 5 y earlier (8) using the same inclusion criteria, 28 new models were included in the draft catalog (2013). However, the authors stressed that the proliferation of NP models can “lead to confusion, inconsistencies between models, and possibly loss of credibility for nutrient profiling with regulators, consumers and researchers.” Given these risks associated with the proliferation of NP models and the time and cost constraints associated with the development and validation of a new model, it is now highly recommended to either adopt or adapt an existing model, ideally one developed by an authoritative body (4, 6). However, an up-to-date, accessible, and global resource summarizing existing NP models is currently unavailable for assisting policymakers in the selection of a model that is appropriate for the use for which it is intended.

The overall aim of this systematic review was therefore to develop such a resource that identifies NP models built in the context of government-led nutrition policies and summarizes their key characteristics. We hypothesized that the number of existing NP models developed by authoritative bodies worldwide has increased since the last review conducted in November 2012 [draft catalog (2013)]. It should also be noted that recommending one NP model over others in the context of a given policy is outside the scope of the present work.

Methods

The present review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (9). The methods of the review were pre-established in a protocol that has been registered in PROSPERO (2015: CRD42015024750) (10).

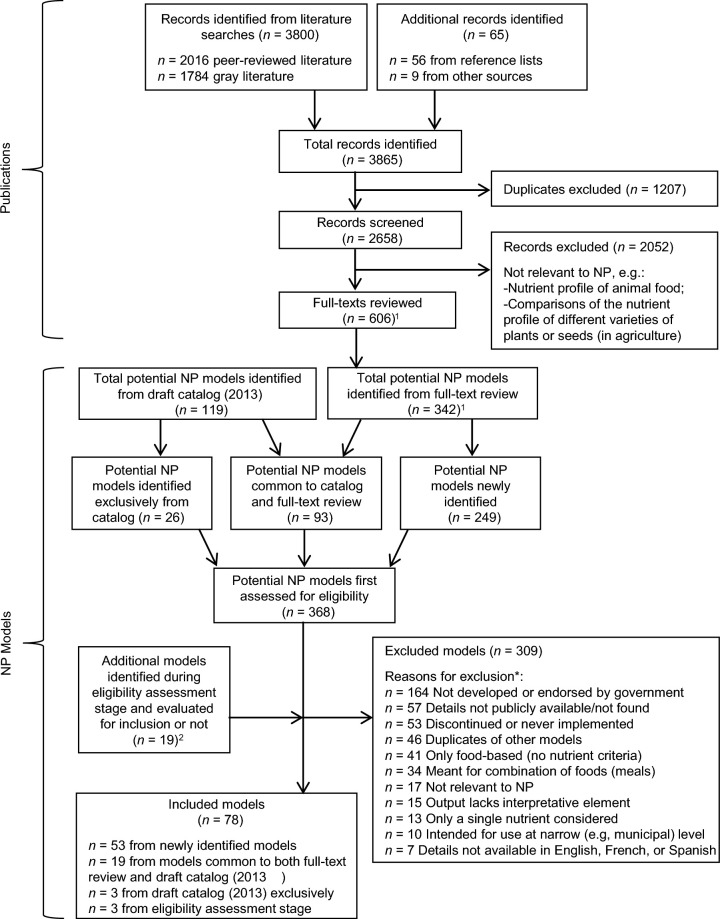

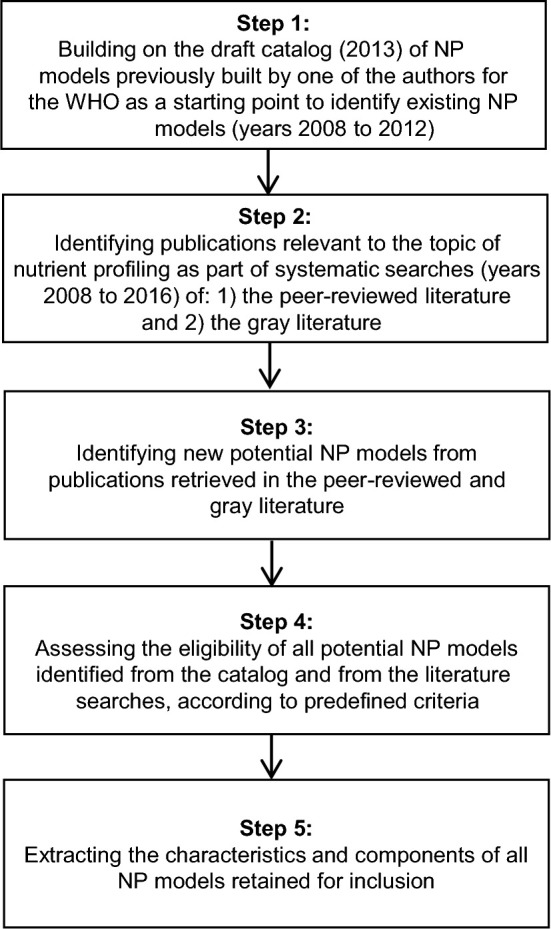

The primary outcome of the systematic review was to identify NP models that exist worldwide for application specifically in government-led nutrition-related policies aimed at health promotion and noncommunicable disease (NCD) prevention. Briefly, the review was conducted following 5 main steps that are described in Figure 1, and further detailed in what follows after the description of the eligibility criteria.

FIGURE 1.

Steps of the systematic review. NP, nutrient profile.

Eligibility criteria

Publication eligibility criteria

The review included any type of publication (e.g., original research articles, reviews, government documents, reports, theses, abstracts, and news articles) that was deemed potentially relevant to nutrient profiling at the screening stage (see the “Publication selection” subsection) to allow for the identification of the maximum possible number of potential NP models. With regard to research articles, there was no restriction on the type of study design or type of participants eligible for inclusion.

NP model eligibility criteria

The present review included publicly available NP models developed or endorsed by government bodies for application in nutrition-related policies at the provincial/state level or higher, which provided an interpretation of the nutritional quality of individual food products based on multiple (i.e., ≥2) nutrients or food components, and which represented the final version in use or a draft version proposed for use within the last 3–5 y, with details available in English, French, or Spanish. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the NP models are fully described in Table 1. Further details on the eligibility assessment stage are also provided in “Step 4: eligibility assessment of all potential NP models identified.”

TABLE 1.

Criteria used for the eligibility assessment of all potential NP models identified1

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Models allowing for the classification or categorization of individual foods | Models only allowing for the classification or categorization of combinations of foods (i.e., meals or diets, such as the Healthy Eating Index) |

| B | Models integrating data from >1 nutrient or food component to produce a single overall score or categorization, or models with separate sets of criteria for multiple nutrients or food components (e.g., Traffic Light System in which the levels of each of the nutrients considered are interpreted separately) |

Models in which only a single nutrient or food component is used, as focusing on only 1 aspect of the nutritional composition can mask the overall nutritional quality of a food product (e.g., nutrient content claim; reformulation targets for single nutrients such as sodium; Whole Grain Stamp) |

| C | Models with a food focus that also use criteria based on nutrients and other food components | Models with a food focus that do not use criteria based on the amounts of nutrients and other food components (e.g., a model that only states that soft soda cannot be advertised to children without considering the underlying nutritional composition of the products) |

| D | Models in which the output (score or classification) includes at least a modest interpretative element | Models in which the output shows little or no interpretative element (e.g., models only repeating the amounts of some nutrients found in the Nutrition Facts Table, or models showing a percentage of GDAs, a percentage of DVs, or the GDAs/DVs themselves) |

| E | Models developed or endorsed2 by governmental or intergovernmental organizations and having applications in government-led nutrition policy and regulation, including, but not limited to the following: | Models developed by different types of organizations (e.g., commercial; nongovernmental; academic) that are not endorsed2 by government bodies (e.g., models developed by the food industry for their own voluntary marketing restrictions; models developed by heart foundations for food-certification schemes) |

| -Food certification schemes/front-of-pack labeling | ||

| -Standards for food advertising or marketing | ||

| -Regulation of health and nutrition claims | ||

| -Food procurement regulations/food-quality standards for public institutions (e.g., schools, workplaces, hospitals, armed services, prisons, elderly care homes) | ||

| -Food taxation | ||

| -Food subsidies | ||

| -Welfare support schemes | ||

| -Food fortification | ||

| -Nutritional surveillance | ||

| F | Models intended for national or international use, or for use in a jurisdiction with responsibility for the relevant food policy or regulation (e.g., models developed by states or provinces responsible for school food standards) | Models intended for use at a very specific/narrow level (e.g., municipal) |

| G | Details of the model are publicly available in the peer-reviewed or gray literature (e.g., government documents/websites, theses) | Details of the model are not known because they are not publicly or freely available, or they could not be found, therefore not allowing for the appropriate use or adaptation of a model or appropriate evaluation of its construct and components |

| H | Final versions of models that are currently in use or draft models that have been proposed for use within the last 3–5 y | Discontinued models no longer in use, or proposed models that were never implemented |

| I | Models that do not duplicate information included previously | Models duplicating information from another model (e.g., an exact same model is described in multiple documents, but under slightly different names) |

| J | Full details of the model are available in English, French, or Spanish | Full details available in another language than specified in the left column |

| K | N/A | “Not relevant”: this represents the situation where it is found, during eligibility assessment, that a policy, regulation, standard, scheme, etc., initially considered as a potential NP model actually does not correspond to such a model (i.e., does not use any criteria to classify foods, either food-based or nutrient-based). For example, this could be a Code in which it is found, when reviewing the source document, that there is a total ban of the commercial advertising of any type of product to children, food or not. Therefore, this means that no NP model is used as part of this Code to determine which foods can or cannot be advertised to children |

1Letters are used to indicate the reason(s) for exclusion in the list of excluded models (Supplemental Table 3). DV, Daily Value; GDA, Guideline Daily Amount; N/A, not applicable; NP, nutrient profile.

2For the purpose of this review, “endorsed” refers to models that are used by governmental or intergovernmental organizations or that are made reference to in government publications in relation to ≥1 of the above applications but that were not developed by such organizations.

Steps of the systematic review

Step 1: Collection of information from a key previous review of NP models

The research team determined that the most- efficient approach to identify NP models would be first to build on the draft catalog of NP models (2013) previously built by one of the authors (MR; see the Introduction for more details). A total of 119 models were identified at that time based on the following: 1) information obtained from 5 reviews of NP models conducted between the end of the year 2007 and the year 2010 (8, 11–14); 2) searches carried out in PubMed, Google, and Google Scholar for articles published since January 2008; 3) information obtained from key individuals and organizations following a joint WHO/International Association for the Study of Obesity technical meeting on nutrient profiling held in London on 4–6 October 2010; and 4) information from the developers/owners of included models to ensure accuracy (summer 2011). The draft catalog included 54 models and excluded 65 models based on predefined eligibility criteria. However, because the current eligibility criteria (Table 1) differed from those used in the catalog, the total of 119 models (i.e., 54 + 65) has been used here as the basis for building a list of potential NP models to be assessed for eligibility.

Step 2: Identification of publications relevant to nutrient profiling in the peer-reviewed and gray literature

Search strategy for the peer-reviewed literature

Searches were carried out in PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus to identify peer-reviewed publications relevant to the topic of nutrient profiling with the use of the following search terms: nutrient, nutritional, or nutrition, each preceding the truncated term profil*. An example of the search strategy specific to each database is provided as supplementary data (Supplemental Table 1). Searches were limited to articles published between January 2008 and 26 May 2016, corresponding to the date that all 3 electronic databases were searched by one of the authors (M-ÈL). The same start date as the one used to build the draft catalog was retained to ensure appropriate retrieval of NP models with applications in government-led nutrition-related policies that were not necessarily captured in the catalog (e.g., food taxation, nutritional surveillance). No restriction on language was imposed during the searches. All search results were exported to a citation management software [EndNote X6; Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters)]. The searches were conducted again in July 2016 (7 July in PubMed, 19 July in EMBASE, and 21 July in Scopus) independently by a second author (MA) to ensure complete retrieval of all relevant articles.

Search strategy for the gray literature

Since valuable sources of information on NP models developed or endorsed by government bodies may not necessarily be identified in the peer-reviewed literature, an extensive search of the gray literature was conducted following consultation with a qualified librarian at the University of Toronto, as described in the study protocol (10). Searches were conducted by one of the authors (M-ÈL) in 15 gray literature search tools including the PAIS Index, Science.gov, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, and OpenGrey between 20 July and 3 August 2016. Details on the search strategy used in each gray literature search tool are provided in Supplemental Table 2. Whenever possible, searches were carried out with the same terms and limits developed for the peer-reviewed literature.

In order to check for saturation of the gray literature search results, brief searches were conducted in addition in the following tools: OpenDOAR (Repository Contents), Google custom searches for Canadian documents (Canadian Government Publications on the Web and Canadian Health Departments and Agencies), Canadian Research Index, and a Google search in the European Union Domain (.eu) specifically. A rapid screening of the first 100 results in each tool (if applicable) led to the observation that only low numbers of potentially relevant records were retrieved, and that these had already been identified via the other search tools. As such, results from these additional searches were not recorded.

Additional publications identified from reference lists or other sources

Additional publications potentially relevant to nutrient profiling that were not retrieved as part of the peer-reviewed and gray literature searches were identified from the search results included in the full-text assessment stage (e.g., by checking the reference lists; see “Step 3: identification of new potential NP models from retained publications” for more details on full-text assessment). Some additional publications were also identified from other sources, consisting of personal communications received by the authors or news articles included in daily e-mail newsletters received by the authors before the start of the eligibility assessment stage of the identified NP models.

Publication selection

Duplicates were removed via EndNote, primarily based on the title, authors, and year of each publication. Publications remaining after this stage were screened for the presence of terms directly related to nutrient profiling or related to the possible applications (i.e., purposes) of NP models (e.g., the terms nutrient, nutritional, nutrition, or food combined with or close to terms including, but not limited to, profil*, criter*, scor*, standard*, requirement*, program*, guideline*, schem*, healthy, healthi*, healthful*, classification, advertis*, market*, labeling/labelling, subsid*, tax*, govern*). Publications containing such terms in their title, abstract, summary, or table of contents, depending on the type of document, were retained for further evaluation. Only the publications that were clearly not relevant to the objective of the systematic review were excluded at this stage (e.g., articles about the nutrient profile of animal food; experimental studies in animal models; nutrition intervention studies comparing the impact of different diets on health outcomes; nutritional profiles of patients with specific diseases, such as cancer; studies in the field of agriculture, such as comparisons of the nutrient profile of different varieties of plants or seeds; government documents on a population's status for a specified nutritional factor, such as vitamin D). Two authors (M-ÈL and MA) independently conducted the screening of articles identified from the peer-reviewed literature. Because of resource and time constraints, only 1 author (M-ÈL) performed the screening of publications identified from the gray literature.

Step 3: Identification of new potential NP models from retained publications

The full text of all publications retained after the screening stage was assessed to identify all potential NP models that were made reference to, described, tested, or used to answer a specific research question in a given publication. Any classification or scoring system, standard, requirement, program, guideline, regulation, legislation, etc., that could potentially include the use of nutritional criteria to evaluate the nutritional quality of food products was recorded as a potential NP model. A similar approach to the one used in the screening stage was adopted in which the full text of the publications was also searched for the presence of terms relevant to nutrient profiling to ensure complete identification of potential NP models.

Given the high number of full texts to review, the large size of certain documents (e.g., theses), and time constraints, the total number of publications was split approximately equally between 2 authors (M-ÈL and TP). The authors captured the names of all potential NP models included in each publication evaluated in order to build a list of models. The authors then evaluated the presence of possible duplicates in the model names, with help from the references provided for each model, and decided on a single name for each potential model. They also assessed whether each potential NP model corresponded to 1 of the 119 models previously identified in the draft catalog (2013) or if it corresponded to a newly identified model. For example, a potential model named “UK Ofcom marketing restrictions” in the authors’ list clearly corresponded to the model from the United Kingdom named “Ofcom model for regulating the marketing of food to children final version (WXYfm)” in the draft catalog (2013), and therefore was given the same identifier (model no.) as in the catalog (i.e., no. 5). For all models that were not previously identified in the catalog, or if not enough information was known at this point to determine whether a model was either a previously identified model or a newly identified model, a new identifier was given to the model in preparation for eligibility assessment, starting from no. 128, which represented the number next to the last identifier given in the draft catalog (2013).

Step 4: Eligibility assessment of all potential NP models identified

Evaluation process

All NP models previously identified in the draft catalog (2013) and newly identified as part of the full-text assessment stage were assessed against the eligibility criteria defined in Table 1. Eligibility assessment was conducted with the use of information from the catalog and from the publications retrieved in the literature searches, supplemented if necessary with information obtained from online searches about specific models (e.g., on Google or government websites), or from requests sent to a contact person in organizations that developed certain models. A preliminary eligibility assessment of the 119 models from the catalog was conducted in January–February 2016, before the literature searches and full-text assessment stage, but final assessment of these models was conducted within the same period as for the newly identified models, that is between 9 August and 22 December 2016. Eligibility assessment was completed independently by 2 authors, more specifically M-ÈL and MA for models from the catalog, and M-ÈL and TP for models identified from the full-text assessment stage. Evaluations were then compared and discordances were resolved by consensus or by involving a third author.

Models that met all eligibility criteria as of 22 December 2016 were included in the review and retained for data extraction. Models that were not eligible based on ≥1 of the exclusion criteria were kept in a list of excluded models (Supplemental Table 3). This list comprises the model number, the model name, the source reference(s), the date of last access, reason(s) for exclusion, details on reason(s) for exclusion, and additional information on the model (if relevant).

Additional NP models identified during the eligibility assessment stage

Some NP models were identified as part of the process of determining the eligibility of the models identified from the catalog and from the full-text assessment stage, through additional documentation reviewed. A few other models were also identified from other sources (e.g., personal communications or e-mail newsletters) during the period that the eligibility assessment process occurred (9 August–22 December 2016). These additional potential NP models were assessed independently by 2 authors (M-ÈL and TP) against the eligibility criteria defined in Table 1.

Step 5: Data extraction

Data on all included NP models were extracted into a Microsoft Office Excel 2010 Workbook using fields based on and adapted from those used previously in the draft catalog (2013). Data extraction fields included, for example the model number, model name, type and name of the organization(s) that developed the model, possible applications (purposes) of the model, a list of food categories included, list of nutrients to limit and nutrients to encourage, reference amounts, outputs, and information on validation. These fields are further detailed in the review protocol (10). One of the authors (BG) conducted most of the data extraction and 3 other authors (TP, BF-A, and M-ÈL) assisted in a small proportion of the models. Most of the data were extracted between 13 October 2016 and 13 February 2017, although data on 9 of the included models had first been extracted in May or June 2016 by 1 of the authors (TP) as a pilot test. Extracted data were also independently verified between 14 November 2016 and 14 April 2017 by 1 of 2 authors (M-ÈL or TP) who did not participate in the initial data extraction of a given model.

In the present article, selected data fields have been separated into different tables to facilitate data synthesis, reading, and understandability. Although the article does not present all of the extracted data, a searchable database including all possible fields will be made available online at http://labbelab.utoronto.ca, to provide information and facilitate comparison of the components and constructs of different NP models for researchers, health and nutrition professionals, policymakers, and other knowledge users interested in nutrient profiling.

Results

Literature search results and publication selection

A total of 3865 records were initially retrieved for the identification of new potential NP models, of which 2016 records were identified from the 3 databases of the peer-reviewed literature, 1784 records from the 15 gray literature search tools, 56 from the reference lists of the publications for which full-text assessment was conducted, and 9 from other sources such as personal communications or e-mail newsletters received by the authors (Figure 2). Of that total, 2658 records remained after the exclusion of duplicates. However, 2052 records were excluded as part of the screening process, because they were found to be irrelevant to the topic of the review. Therefore, the full text of 606 publications was retrieved for further evaluation.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of the publications and NP models selection. Data are current as of 22 December 2016. 1The number of publications included in the full-text assessment is independent of the number of potential models identified from these publications. 2Of these 19 models, n = 15 were specifically identified as part of the process of assessing the eligibility of the first 368 potential models (e.g., through additional documentation reviewed) and n = 4 were identified from other sources (e.g., personal communication or e-mail newsletter received during the weeks that the eligibility assessment process occurred). *Note: Total is higher than 309 because n = 123 models are classified into ≥2 possible reasons for exclusion. NP, nutrient profile.

Identification of NP models and eligibility assessment

The full-text assessment stage permitted the identification of 342 potential NP models, of which 249 consisted of newly identified models and 93 were common to the 119 models from the draft catalog (2013) (Figure 2). Thus, only 26 potential NP models were identified exclusively from the draft catalog (2013), giving 368 potential NP models first assessed for eligibility. Nineteen additional potential NP models were identified during the eligibility assessment process through additional documentation reviewed, personal communications, or e-mail newsletters received by the authors, and were also assessed for eligibility. Of the total 387 potential NP models, 78 met the inclusion criteria. Of the 309 models that did not meet the inclusion criteria, over half (n = 164, 53%) were excluded because they were not developed or endorsed by a government body (Figure 2). More than one possible reason for exclusion was applicable to 40% of the excluded models (n = 123). As indicated previously, supplementary data (Supplemental Table 3) provide the detailed reason(s) for exclusion, per excluded model.

Main characteristics of included NP models

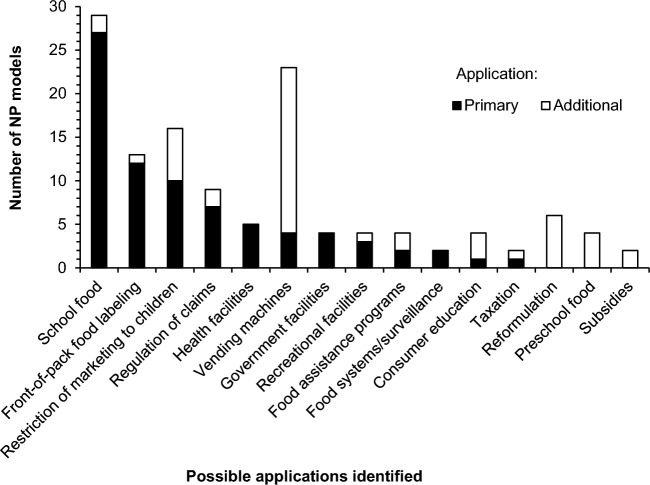

Possible applications of NP models

Each included NP model has been associated with a single primary application, representing the main purpose for which the model was built. This was essentially determined based on the model's name and on specifications provided in the source reference of the model (e.g., based on a clear mention of the model's primary purpose or, alternatively, based on the model's main output or on the order according to which all potential applications of the model were listed). Figure 3 shows that of 12 possible primary applications identified, the top 5 consisted of school food standards/requirements (n = 27, 35%), FOP food labeling (n = 12, 15%), restriction of marketing to children (n = 10, 13%), regulation of health or nutrition claims (n = 7, 9%), and food standards/requirements in health facilities (n = 5, 6%). At least 1 additional application was identified for 37 (47%) of the included models. An additional application represented one that was specified in the source document of a model in addition to its primary application. The most common additional applications represented standards for vending machines in various settings (n = 19), restriction of marketing to children (n = 6), and reformulation (n = 6). Table 2 provides details on the specific model numbers associated with each possible application, either primary or additional.

FIGURE 3.

Number of NP models associated with each possible application identified. An application represents the purpose for which an NP model was built. Applications are sorted first by descending order of the number of models per primary application and second by descending order of the number of models per additional application (where relevant). Each model is associated with only 1 primary application; therefore, the total of the number of models per primary application equals 78. An additional application represents one that is specified in the source reference of a model in addition to its primary application (e.g., model no. 11 is primarily meant for front-of-pack food labeling but also has reformulation as an additional application). For a given model, the number of additional applications could range between 0 and 5. Further details on the possible applications of the models and specific model numbers associated with each one are provided in Table 2. NP, nutrient profile.

TABLE 2.

Applications listed for the 78 included NP models and model numbers associated with each application1

| Applications | Primary application, n | Model number(s) | Additional application, other than primary, n | Model number(s) | Total: primary + additional application, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food labeling: | |||||

| Food certification scheme/front-of-pack labeling | 12 | 1; 11; 27; 41; 53; 73; 156; 172; 178; 196; 291; 314 | 1 | 388 | 13 |

| Regulation of claims (e.g., health and/or nutrient claims) | 7 | 18; 20; 35; 69; 75; 319; 394 | 2 | 27; 73 | 9 |

| Food in public settings: | |||||

| Schools | 27 | 59; 60; 61; 70; 72; 76; 93; 131; 138; 140; 1442; 163; 167; 180; 193; 200; 205; 211; 241; 248; 259; 272; 290; 293; 325; 352; 393 | 2 | 44; 388 | 29 |

| Preschools | 0 | N/A | 4 | 70; 72; 131; 293 | 4 |

| Recreational facilities (e.g., national parks) | 3 | 169; 273; 376 | 1 | 131 | 4 |

| Health facilities (e.g., hospitals) | 5 | 160; 201; 285; 367; 381 | 0 | N/A | 5 |

| Government facilities (e.g., food procurement; food sold in cafeterias) | 4 | 174; 232; 330; 364 | 0 | N/A | 4 |

| Vending machines (in various settings) | 4 | 146; 256; 329; 3413 | 19 | 60; 61; 76; 131; 160; 169; 180; 193; 200; 241; 248; 259; 272; 293; 325; 330; 364; 367; 381 | 23 |

| Restriction of the promotion/marketing of foods to children | 10 | 5; 44; 62; 220; 251; 287; 334; 335; 388; 392 | 6 | 70; 1442; 156; 167; 180; 272 | 16 |

| Food assistance programs | 2 | 81; 318 | 2 | 254; 388 | 4 |

| Food systems/surveillance | 2 | 195; 254 | 0 | N/A | 2 |

| Consumer education | 1 | 351 | 34 | 201; 367; 376 | 4 |

| Taxation | 1 | 3715 | 1 | 388 | 2 |

| Reformulation | 0 | N/A | 6 | 11; 53; 70; 178; 3715; 393 | 6 |

| Subsidies | 0 | N/A | 2 | 201; 388 | 2 |

1An application represents the purpose for which an NP model was built. Each model is associated with only 1 primary application; therefore, the total of the number of models per primary application equals 78. An additional application represents one that is specified in the source reference of a model in addition to its primary application (e.g., model no. 11 is primarily meant for front-of-pack food labeling but also has reformulation as an additional application). For a given model, the number of additional applications could range between 0 and 5. N/A, not applicable; NP, nutrient profile.

2Other additional applications for model 144 not indicated in the table include: limiting the sale of sugar substitutes; supporting healthy eating in the classroom (classroom celebrations and rewards); decreasing or eliminating bottled water.

3An additional application for model 341 not indicated in the table includes: concessions (meaning here food services in general; not specifically related to recreational, health, or government facilities).

4Also implied in most of the other models without necessarily being explicitly mentioned (e.g., model no. 291).

5Another additional application for model 371 not indicated in the table includes: revenue-generating tool (for the health care system).

Characteristics related to the development of NP models

Table 3 describes the characteristics related to the development of each NP model including the model name, the country and state/province of origin, the type(s) and name(s) of the organization(s) that developed the model, and the year of introduction or seminal publication of the model. Models were primarily listed according to their primary application and country. Two-thirds of the models originated from the following countries: United States (n = 19), Canada (n = 13), Australia (n = 10, of which 2 models were developed jointly with New Zealand), United Kingdom (n = 5), and international (n = 5; e.g., models by regional offices of the WHO). Only 4 models (5%) were solely endorsed as opposed to developed either partly or completely by a governmental or intergovernmental organization. Most models (n = 57, 73%) were first introduced within the past 10 y, that is from 2007 onwards. Almost half of these models (n = 27/57; representing 35% of all included models) were more specifically introduced within the past 5 y, that is from 2012 onwards, essentially for the purposes of restricting marketing to children (n = 7), food labeling (n = 5), and school food standards/requirements (n = 5). Only 4 models were introduced in the 1980s or 1990s, and the year of introduction was not specified for 2 of the included models. Thirty-four models (44%) were found to be derived from another model identified as part of the present systematic review.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of the development of each included NP model (n = 78)1

| Country | State/province | Model number | Model name (reference) | Organization type | Organization name | Year of introduction or seminal publication | Model derived from other models identified as part of the review? [yes (indicated by model numbers) or no] | Model that served at least in part as the basis for the development of ≥1 other included model? [yes (indicated by model numbers) or no] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School food (n = 27) | ||||||||

| Australia | N/A | 93 | National Healthy School Canteens Project (15, 16) | Govt or intergovt, academic | Australian Government (Department of Health) and Flinders University (with support from Flinders Partners) | 2010 | 138 | No |

| Australia | New South Wales | 138 | Australia—Fresh Tastes @ School NSW Healthy School Canteens Strategy (17) | Govt or intergovt | NSW Department of Health and NSW Department of Education and Training | 2004 | No | 93; 140; 273; 290; 293; 367; 381 |

| Australia | Queensland | 290 | Smart Choices: healthy food and drink supply strategy for Queensland schools—nutrient criteria for the “Occasional” (red) food and drink category (18) | Govt or intergovt | Queensland Government (Education Queensland and Queensland Health) | 2004–2007 (revised 2016) | 138 | 273; 381 (therefore indirectly: 367) |

| Australia | South Australia | 293 | South Australia Right Bite for schools and preschools—nutrient criteria for the “Occasional” (red) category (19) | Govt or intergovt | Government of South Australia, Department for Education and Child Development | 2008 (revised 2015) | 138 | No |

| Australia | Victoria | 140 | Australia—State Government of Victoria—Go For Your Life healthy canteen kit—nutrient criteria for the “Occasionally” (red) food category (20) | Govt or intergovt | Office of Learning and Teaching, Department of Education and Training Victoria | 2006 | 138 | No |

| Canada | N/A | 393 | Canada—Provincial and Territorial nutrient criteria for foods and beverages in schools (2013) (21) | Govt or intergovt | Federal, Provincial, Territorial Group on Nutrition Working Group on Improving the Consistency of School Food and Beverage Criteria [working group included members from provincial/territorial government health departments and (federal) Health Canada] | 2013 | 131; 144; 180; 193; 200 (therefore indirectly: 282); 241; 259; 272 | No |

| Canada | Alberta | 131 | Alberta nutrition guidelines for children and youth (22) | Govt or intergovt | Government of Alberta (collaborative effort initiated by Alberta Health, Wellness Branch, Family and Population Health Division) | 2008 | No | 393 |

| Canada | British Columbia | 144 | Guidelines for food and beverage sales in BC schools (23) | Govt or intergovt | Government of BC (Ministry of Health, Population and Public Health Division and Ministry of Education) | 2005 (mandated for all public schools in 2008; revised 2010 and 2013) | No | 146; 393 |

| Canada | Manitoba | 193 | Guidelines for foods available in K to 12 schools in Manitoba (criteria for packaged foods) (24) | Govt or intergovt | Government of Manitoba | 2006 (revised 2014)2 | No | 393 |

| Canada | New Brunswick | 241 | New Brunswick healthier foods and nutrition in public schools (25, 26) | Govt or intergovt | Department of Education in partnership with the Department of Wellness, Culture and Sport | 2005 (revised 2008) | No | 393 |

| Canada | Nova Scotia | 180 | Food and beverage standards for Nova Scotia public schools (27) | Govt or intergovt | Nova Scotia Department of Education and Nova Scotia Department of Health Promotion and Protection | 2006 | No | 393 |

| Canada | Ontario | 259 | Ontario school food and beverage policy/program memorandum 150 (PPM 150) (28) | Govt or intergovt | Ontario Ministry of Education | 2010 (effective 2011) | No | 393 |

| Canada | PEI | 272 | PEI school nutrition policy (29) | Govt or intergovt | PEI Healthy Eating Alliance, Eastern School District | 2011 (superseded 2005 policy) | No | 393 |

| Canada | Saskatchewan | 200 | Healthy eating guidelines for Saskatchewan schools (Nourishing Minds) (30) | Govt or intergovt | Saskatchewan Ministry of Education in partnership with the Ministries of Health and Social Services | 2009 (revised 2012) | 282 (earlier version) | 393 |

| China | Hong Kong | 205 | Hong Kong nutritional criteria for snack classification (31) | Govt or intergovt | Department of Health | 2006 (revised 2009, 2010, 2014) | No | No |

| Costa Rica | N/A | 72 | Costa Rica school food regulations (32) | Govt or intergovt | Ministerio de Educación Pública and Ministry of Health | 2011 (effective 2012) | No | No |

| Czech Republic | N/A | 167 | Czech Republic draft decree for food sold and advertised in schools (33) | Govt or intergovt | Ministry of Education, Youth, and Physical Education and the Ministry of Health | 2016 | No | No |

| Greece | N/A | 59 | New School Canteen Standards (34) | Govt or intergovt | Greek Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity | 2006 | No | No |

| India | N/A | 211 | FSSAI draft guidelines for making available wholesome, nutritious, safe and hygienic food to schoolchildren in India (35) | Govt or intergovt | Central Advisory Committee of the FSSAI | 2015 | No | No |

| New Zealand | N/A | 70 | Food and beverage classification system nutrient criteria (Fuelled4life) (36) | Govt or intergovt, NGO | Ministry of Health, but managed by the New Zealand Heart Foundation | 2007 (revised 2013)3 | No | No |

| Scotland | N/A | 60 | Scotland nutritional requirements for food and drink in schools (37) | Govt or intergovt | Scottish Government | 2008 | No | No |

| Singapore | N/A | 76 | Healthy meals in schools program (Eating Healthily At The School Canteen) (38, 39) | Govt or intergovt | Health Promotion Board | 2009 (former version, Model School Tuckshop Programme, introduced in 2003) | 73 | No |

| United Kingdom (England) | N/A | 61 | England requirements for school food regulations (40, 41) | Govt or intergovt | Secretary of State for Education, England | 2007 (revised 2014; effective 2015) | No | No |

| United States | N/A | 325 | USDA smart snacks in school nutrition standards (also known as competitive food standards) (42) | Govt or intergovt | USDA | 2013 (effective 2014) | 80 | 163; 352 |

| United States | California | 352 | California's nutrition standards SB12 and SB965 (competitive food and beverage standards for schools) (43, 44) | Govt or intergovt | California Department of Education | 2005 | 325 (therefore indirectly: 80) | No |

| United States | Connecticut | 163 | Connecticut nutrition standards (45) | Govt or intergovt | Connecticut State Department of Education | 2006 (revised 2016)4 | 325 (therefore indirectly: 80) | No |

| United States | North Carolina | 248 | Eat Smart: North Carolina's recommended standards for all foods available in school (46) | Govt or intergovt | North Carolina Division of Public Health, North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, and the North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service | 2004 | 125 | No |

| Front-of-pack food labeling (n = 12) | ||||||||

| International | N/A | 53 | Choices (47, 48) | Foundation (private initiative) | Choices International Foundation5 | 2006 | No | No |

| Australia and New Zealand | N/A | 196 | Health Star Rating System (49, 50) | Govt or intergovt, commercial, NGO | Australian state and territory governments and New Zealand Government in collaboration with industry, public health, and consumer groups6 | 2014 | 20 (therefore indirectly: 5) | No |

| Chile | N/A | 156 | Chile “Black Octagonal Stop-Sign” warning labels (51) | Govt or intergovt | Ministry of Health (Ministerio de Salud) | 2012 (effective 2015) | No | No |

| Ecuador | N/A | 172 | Ecuador traffic light labeling system (52) | Govt or intergovt | Ministry of Public Health | 2014 | 41 | No |

| Finland | N/A | 27 | Heart symbol (53) | NGO, govt or intergovt | Finnish Heart Association and Finnish Diabetes Association, in active collaboration with the Finnish Food Safety Authority | 2000 | No | No |

| France | N/A | 178 | Five-Colour Nutrition Label (5-CNL/Nutri-Score) (54) | Govt or intergovt, academic | National Nutrition and Health Program (PNNS) of ANSES7 | 2013 | 5 | No |

| Singapore | N/A | 73 | Healthier choice symbol program (55) | Govt or intergovt | Health Promotion Board (Healthy Foods and Dining Department, Obesity Prevention Management Division) | 2009 | No | 75; 76 |

| Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Iceland | N/A | 11 | Keyhole (56) | Govt or intergovt | Swedish National Food Administration, Norwegian Directorate of Health and Norwegian Food Safety Authority, Danish Veterinary and Food Administration | 1989 in Sweden (revised 2005 and 2009); 2009 in Norway and Denmark; 2013 in Iceland (revised 2015) | No | 251 (therefore indirectly: 335; 334); 314 |

| United Arab Emirates | N/A | 314 | United Arab Emirates nutrition labeling model (Weqaya logo) (57, 58) | Govt or intergovt, academic, commercial | Abu Dhabi Quality and Conformity Council8 | 2015 | 11 | No |

| United Kingdom | N/A | 41 | Traffic light labeling (59) | Govt or intergovt | Food Standards Agency9 | 2007 (revised 2016) | No | 172 |

| United States | N/A | 1 | Fruits & veggies—More Matters (60) | NGO (nonprofit consumer education foundation), govt or intergovt | Produce for Better Health Foundation and US CDC | 2007 (former version, 5 A Day Program, introduced in 1991) | No | 291 |

| United States | Colorado | 291 | Smart Meal Seal nutrition criteria (61, 62) | Govt or intergovt, commercial | COPAN (program of the CDPHE) with food service/industry partners10 | 2007 (revised 2012) | 1; 133; 134; 135 | No |

| Restriction of marketing to children (n = 10) | ||||||||

| International | N/A | 334 | WHO nutrient profile model for the Western Pacific Regional Office (WHO-WPRO) (63) | Govt or intergovt | WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific Region | 2015 (field tested); 2016 (published) | 335 (therefore indirectly: 62; 251 (also implies 5; 11)) | No |

| International | N/A | 335 | WHO Regional Office for Europe nutrient profile model (WHO-EURO) (64) | Govt or intergovt | WHO Regional Office for Europe in collaboration with Department of Nutrition for Health and Development at WHO headquarters | 2015 | 62; 251 (therefore indirectly: 5; 11) | 334 |

| International | N/A | 388 | PAHO nutrient profile model (WHO Regional Office for the Americas) (65) | Govt or intergovt | PAHO | 2016 | 123 | No |

| Denmark | N/A | 62 | Danish Code of responsible food marketing communication to children (66) | Commercial | Forum of Responsible Food Marketing Communication11 | 2008 (revised 2010) | No | 335 (therefore indirectly: 334) |

| Ireland | N/A | 220 | Ireland—broadcasting authority model for restricting the marketing of food and drink to children (67, 68) | Govt or intergovt | Broadcasting Authority of Ireland | Not specified (revised and effective 2013) | 5 | No |

| Mexico | N/A | 392 | Mexico—restriction on the promotion of high-caloric-density foods (69) | Govt or intergovt | Ministry of Health (Secretaria de Salud) | 2014 (effective 2015) | No | No |

| Norway | N/A | 251 | Norwegian Nutrient Profile model (70) | Govt or intergovt | Norwegian Directorate of Health12 | 2012 (revised 2013) | 5; 11 (were considered for the development of the present model) | 335 (therefore indirectly: 334) |

| Singapore | N/A | 287 | Singapore common nutrition criteria of the guidelines for food advertising to children (71) | Govt or intergovt | Nutrition Working Group established following discussions with Ministry of Health, HPB, and ASAS | 2013 (consultation); 2014 (published); effective 2015 | No | No |

| South Korea | N/A | 44 | South Korea—guideline for energy-dense, nutrition-poor food for children (72, 73) | Govt or intergovt | Korea FDA | 2009 | No | No |

| United Kingdom | N/A | 5 | Ofcom model for regulating the marketing of food to children, final version (WXYfm) (74) | Govt or intergovt | Ofcom (broadcast regulator) and Department of Health (Food Standards Agency) | 2004–2005 (revision process started in October 2016) | No | 20 (therefore indirectly: 196; 394); 178; 220; 251 (therefore indirectly: 335; 334) |

| Regulation of claims (n = 7) | ||||||||

| Australia and New Zealand | N/A | 20 | FSANZ—nutrient profiling scoring criterion (75) | Govt or intergovt | FSANZ | 2007 | 5 | 196; 394 |

| France | N/A | 69 | The SAIN, LIM system (76) | Govt or intergovt | French Food Safety Agency (Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Aliments) | 2008 | 227; 253 | No |

| Singapore | N/A | 75 | Singapore—nutrient- specific diet-related health claims (77) | Govt or intergovt | Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority | 2010 | 73 | No |

| South Africa | N/A | 394 | South Africa NP model (FSANZ validated in South Africa) (78) | Govt or intergovt, academic, commercial | Centre of Excellence for Nutrition, North-West University, South Africa; FSANZ13 | 2013 | 20 (therefore indirectly: 5) | No |

| United States | N/A | 18 | US—requirements for foods carrying a health claim (79) | Govt or intergovt | US FDA | 1993 | No | No |

| United States | N/A | 35 | US—definition of a “healthy” food as an implied nutrient content claim (80) | Govt or intergovt | US FDA | 1993 (revision process started in September 2016) | No | No |

| United States | N/A | 319 | US—requirements for the “extra lean” and “lean” nutrient content claims (81) | Govt or intergovt | US FDA | Not specified | No | No |

| Health facilities (n = 5) | ||||||||

| Australia | Queensland | 381 | Queensland Health's A better choice – healthy food and drink supply strategy (2007)—nutrient criteria for the red category (82) | Govt or intergovt | Queensland Government (Queensland Health) | 2007 | 138; 290 | 367 |

| Australia | South Australia | 367 | Healthy food and drink choices for staff and visitors in South Australia health facilities—nutrient criteria for the red category (83) | Govt or intergovt | Government of South Australia, Department of Health | 2009 | 138; 381 (therefore indirectly: 290) | No |

| Canada | Nova Scotia | 160 | Colchester East Hants Health Authority food and beverage nutrient standards (84, 85) | Govt or intergovt | Colchester East Hants Health Authority, Nova Scotia (referred to as Nova Scotia Health Authority since April 2015) | 2013 | No | No |

| Scotland | N/A | 285 | Scotland nutritional standards for hospital food: Food in Hospitals (86, 87) | Govt or intergovt | Scottish Government | 2008 (revised 2016) | No | No |

| United States | North Carolina | 201 | Healthy food environments pricing incentives Nutrition Criteria (88–90) | NGO (nonprofit organization) | North Carolina Prevention Partners14 | 2007 (revised 2013) | No | No |

| Government facilities (n = 4) | ||||||||

| United Kingdom (England) | N/A | 174 | England government buying standards for food and catering services (91) | Govt or intergovt | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 2014 (revised 2015) | No | No |

| United States | N/A | 364 | Food service guidelines for federal facilities (formerly Health and sustainability guidelines for federal concessions and vending operations; HHS/GSA guidelines) (92, 93) | Govt or intergovt | Health and Human Services General Services Administration collaborative team, Federal Health and Sustainability Team for Concessions and Vending | 2011 (revised 2017)15 | No | 256; 330; 376 |

| United States | Massachusetts | 232 | Massachusetts state agency food standards (94) | Govt or intergovt | Nutrition and Physical Activity Obesity Initiative, Bureau of Community Health Access and Promotion, Massachusetts Department of Public Health | 2009 (revised 2012) | No | No |

| United States | Washington | 330 | Washington State healthy nutrition guidelines (95) | Govt or intergovt | Washington State Department of Health | 2014 | 364 (in part) | No |

| Vending machines (n = 4) | ||||||||

| Canada | British Columbia | 146 | Healthier choices in vending machines in BC public buildings policy (96) | Govt or intergovt | Government of BC (Ministry of Health, Population and Public Health Division) | 2006 (revised 2014) | 144 | No |

| United Kingdom (Wales) | N/A | 329 | Wales—health-promoting vending guidance (hospitals) (97) | Govt or intergovt | Department of Health and Health Improvement Division of the Welsh Government | 2008 | No | No |

| United States | N/A | 341 | Nemours Health and Prevention Services (Delaware's public health department) “Go, Slow, and Whoa” model (guide to healthier vending and concessions) (98, 99) | NGO (nonprofit foundation) | Nemours Health and Prevention Services16 | 2010 | No | 169 |

| United States | Iowa | 256 | Nutrition Environment Measurement Survey-Vending (NEMS-V) traffic light system (100, 101) | Govt or intergovt, academic, NGO (nonprofit foundation) | Iowa State University Extension and Outreach, Iowa Department of Public Health, and Wellmark Foundation | 2012 | 364 (when it was previously called Health and sustainability guidelines for federal concessions and vending operations) | No |

| Recreational facilities (n = 3) | ||||||||

| Australia | Queensland | 273 | Queensland—red criteria of the Food for Sport guidelines (102, 103) | Govt or intergovt | Department of National Parks, Sport and Racing, Queensland Government | Not specified (Queensland Government websites updated 2010 and 2011) | 138; 290 | No |

| United States | N/A | 376 | US National Park Service healthy food choice standards and sustainable food choice guidelines for front country operations (104) | Govt or intergovt | US National Park Service | 2012 (revised 2013) | 364 | No |

| United States | Delaware | 169 | Delaware State Parks healthy eating initiative—“Munch Better at Delaware State Parks” (105, 106) | NGO (nonprofit foundation), govt or intergovt | Nemours Health and Prevention Services, Delaware Division of Parks and Recreation, and Delaware Health and Social Services’ Division of Public Health | 2010 | 341 | No |

| Food assistance programs (n = 2) | ||||||||

| United States | N/A | 81 | Minimum requirements and specifications for food items allowed in the WIC food packages (supplemental foods) (107, 108) | Govt or intergovt | USDA, Food and Nutrition Service | 1980 (interim rule 2007; final rule 2014) | No | 318 |

| United States | Georgia | 318 | US—Georgia WIC approved food list—criteria to evaluate an eligible food item (109, 110) | Govt or intergovt | Georgia Department of Public Health, Georgia WIC- Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for WIC | Not specified (criteria to evaluate an eligible food item updated 2015; WIC- approved foods list revised 2016) | 81 | No |

| Food systems/ surveillance (n = 2) | ||||||||

| International | N/A | 254 | Nutrient value score (111, 112) | Govt or intergovt | UN World Food Program | 2013 | No | No |

| Canada | N/A | 195 | Health Canada Surveillance Tool tier system (113) | Govt or intergovt | Health Canada | 2014 | No | No |

| Consumer education (n = 1) | ||||||||

| Canada | Alberta | 351 | Alberta nutrition guidelines for adults (114) | Govt or intergovt | Government of Alberta | 2012 | No | No |

| Taxation (n = 1) | ||||||||

| Hungary | N/A | 371 | Hungarian public health tax (tax on food products containing unhealthy levels of sugar, salt, and other ingredients) (115–117) | Govt or intergovt | Hungarian Government | 2011 (revised 5 times between 2011 and 2015) | No | No |

1ANSES, Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire de l'Alimentation, de l'Environnement et du Travail; ASAS, Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore; BC, British Columbia; CDPHE, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment; COPAN, Colorado Physical Activity and Nutrition Program; FSANZ, Food Standards Australia New Zealand; FSSAI, Food Safety and Standards Authority of India; Govt/govt, government; GSA, General Services Administration; HHS, Health and Human Services; HPB, Health Promotion Board; intergovt, intergovernmental; LIM, limited nutrients; N/A, not applicable; NGO, nongovernmental organization; NP, nutrient profile; NSW, New South Wales; Ofcom, Office of Communications; PAHO, Pan American Health Organization; PEI, Prince Edward Island; PNNS, Programme National Nutrition Santé; SAIN, Nutrient Adequacy Score for Individual foods; WHO-EURO, WHO-Europe; WHO-WPRO, WHO Western Pacific Region; WIC, Women, Infants and Children.

2Data from the 2014 version were extracted.

3Nutritional criteria from the September 2013 version were extracted. This information was e-mailed to one of the authors by the New Zealand Heart Foundation in February 2016. The New Zealand Heart Foundation also indicated that the criteria were due for review in 2016.

4Data from the 2016 version were extracted.

5Although the model was developed by a foundation, the initiative was initially triggered by a governmental request to the food industry in the Netherlands as indicated by Roodenburg et al. (47).

6Including Australian Beverages Council, Australian Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance, Australian Food and Grocery Council, Australian Industry Group, Australian Medical Association, Australian National Retail Association, CHOICE, Obesity Policy Coalition, and Public Health Association of Australia.

7The model specifically proposed by Serge Hercberg (professor at the University Paris-XIII and director of the PPNS) as per a request by the Minister of Social Affairs and Health (Ministre des Affaires Sociales et de la Santé) in June 2013.

8The working Group consists of members from Abu Dhabi Quality and Conformity Council, Health Authority Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi Food Control Authority, Emirates Authority For Standardization and Metrology, United Arab Emirates University, Abu Dhabi University, AGTHIA Company, Al FOAH Company, and AbuDhabi Farmers Service Centre.

9The responsibility for the policy was transferred to the Department of Health as of October 2010. Also, it is stressed that the updated 2016 guidance document was developed by the Department of Health, the Food Standards Agency, and devolved administrations in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales in collaboration with the British Retail Consortium.

10COPAN partnered with the Colorado Restaurant Association and owners of large and small restaurants to help shape and define the Smart Meal Seal program.

11The model is endorsed by the Danish government as indicated in the reference document of the WHO Regional Office for Europe nutrient profile model (no. 335).

12The working group consisted of the Norwegian Directorate of Health, Consumer Ombudsman, Food Safety Authority, Ministry of Children and Equality, Ministry of Health and Care Services, and Secretariat: Ministry of Health and Care Services.

13The original model (no. 20) was developed by government. Stakeholders for the present model no. 394 included government (Department of Health, South Africa, Directorate: Food Control; FSANZ), the food industry, and academia (North-West University).

14According to the USDA webpage, the present program is part of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)-Ed Strategies & Interventions Toolkit. The model therefore appears to be endorsed by the government.

15Data from the 2011 version were extracted.

16The model was developed by a foundation but is endorsed or used by Delaware State Parks (refer to model no. 169).

Characteristics related to the components of NP models

Table 4 summarizes the key characteristics related to the components of included NP models, overall and according to the 12 primary applications identified. A more -detailed summary of the key characteristics of each model is provided in Table 5. Supplementary data also provide further details on the specific nutrients and food components “to limit” and “to encourage” included in each model (Supplemental Table 4) and on the specific types of reference amounts and other evaluation units used in each model (Supplemental Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Main characteristics of NP models, overall and according to the 12 primary applications identified1

| Characteristics | Total (n = 78) | School food (n = 27) | Front-of-pack food labeling (n = 12) | Restriction of marketing to children (n = 10) | Regulation of claims (n = 7) | Health facilities (n = 5) | Government facilities (n = 4) | Vending machines (n = 4) | Recreational facilities (n = 3) | Food assistance programs (n = 2) | Food systems/ surveillance (n = 2) | Consumer education (n = 1) | Taxation (n = 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of rating system | |||||||||||||

| Summary rating of the nutritional quality | 71 (91) | 27 (100) | 7 (58) | 9 (90) | 7 (100) | 5 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Nutrient-specific rating | 3 (4) | — | 3 (25) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Combination of both | 4 (5) | — | 2 (17) | 1 (10) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 (50) | — | — |

| Type of output | |||||||||||||

| Classification | 70 (90) | 27 (100) | 10 (83) | 8 (80) | 4 (57) | 5 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Score | 1 (1) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 (50) | — | — |

| Combination of both | 7 (9) | — | 2 (17) | 2 (20) | 3 (43) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Food categories2 | |||||||||||||

| Level(s) at which nutrient criteria are applied (major, sub-, and/or sub-subcategory level) | |||||||||||||

| Major only | 36 (46) | 5 (19) | 6 (50) | 6 (60) | 6 (86) | 3 (60) | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | 2 (67) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | — | — |

| Major and sub | 21 (27) | 12 (44) | 2 (17) | 3 (30) | — | — | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | — | 1 (50) | — | — | 1 (100) |

| Major, sub, and sub-sub | 6 (8) | — | 1 (8) | 1 (10) | — | 2 (40) | 1 (25) | — | 1 (33) | — | — | — | — |

| Sub only | 12 (15) | 9 (33) | 2 (17) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 (100) | — |

| Sub and sub-sub | 3 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (8) | — | 1 (14) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Total number of food categories including nutrient criteria (major, sub-, and sub-subcategories combined, if applicable) (min–max) | 1–99 | 2–73 | 2–99 | 1–31 | 1–99 | 3–9 | 3–27 | 5–14 | 2–9 | 15–22 | 1–4 | 25 | 12 |

| Nutrients and food components | |||||||||||||

| Number/type of nutrients and food components may vary across the model's food categories/types of food product evaluated | 60 (77) | 26 (96) | 6 (50) | 7 (70) | 2 (29) | 5 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Inclusion of nutrients3 to limit | 78 (100) | 27 (100) | 12 (100) | 10 (100) | 7 (100) | 5 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Number of nutrients3 considered (min–max) | 2–12 | 3–12 | 3–12 | 2–8 | 3–11 | 3–9 | 3–10 | 4–12 | 4–6 | 7–12 | 2–4 | 11 | 6 |

| Top 3 nutrients3 considered (% of models that include the nutrient)4 | 1. Total sodium (91) | 1. Total sodium (93) | 1. Total sodium (100) | 1. SFAs (90) | 1. SFAs (100) | 1. SFAs (100) | 1. Energy (100) | 1. Free/added sugars (100) | 1. Energy (100) | 1. Added fat (100) | 1. Total fat (100) | N/A | N/A |

| 2. SFAs (83) | 2. SFAs (89) | 2. SFAs (83) | 2. Total sodium (90) | 2. Total sodium (86) | 2. Energy (80) | 2. Total sugars (100) | 2. SFAs (100) | 2. Total sodium (100) | 2. Added sodium (100) | 2. Energy (50) | |||

| 3. Total sugars (73) | 3. Total fat (81) | 3. Total sugars (75) | 3. Total sugars (90) | 3. Cholesterol (57) | 3. Total sodium (80) | 3. Total fat (75) | 3. Total fat (100) | 3. SFAs (67) | 3. Free/added sugars (100) | 3. SFAs (50) | |||

| 4. Total fat (57) | 4. Total sodium (75) | 4. Total sodium (100) | 4. Total fat (67) | 4. Total fat (100) | 4. Total sodium (50) | ||||||||

| 5. trans fat (75) | 5. Total sodium (100) | 5. Total sugars (50) | |||||||||||

| 6. Total sugars (100) | |||||||||||||

| Inclusion of nutrients3 to encourage | 67 (86) | 25 (93) | 9 (75) | 6 (60) | 6 (86) | 5 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Number of nutrients3 considered (min–max) | 1–15 | 1–14 | 1–8 | 1–8 | 3–8 | 1–2 | 2–5 | 1–5 | 1–2 | 14–15 | 9 | 7 | 1 |

| Top 3 nutrients3 considered (% of models that include the nutrient)4 | 1. FVNL (64) | 1. Fiber (60) | 1. Fiber (89) | 1. Fiber (67) | 1. Fiber (100) | 1. Fiber (40) | 1. FVNL (100) | 1. FVNL (100) | 1. Fiber (67) | Many5 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2. Fiber (63) | 2. FVNL (56) | 2. FVNL (89) | 2. Protein (67) | 2. Protein (83) | 2. FVNL (40) | 2. Fiber (75) | 2. Whole grain (75) | 2. FVNL (33) | |||||

| 3. Protein (43) | 3. Whole grain (48) | 3. Whole grain (44) | 3. FVNL (50) | 3. Calcium (67) | 3. Energy (20) | 3. Calcium (50) | 3. Calcium (25) | 3. Whole grain (33) | |||||

| 4. Protein (20) | 4. Whole grain (50) | 4. Fiber (25) | |||||||||||

| 5. Whole grain (20) | 5. Milk/dairy-based content (25) | ||||||||||||

| 6. Protein (25) | |||||||||||||

| 7. Small serving size (25) | |||||||||||||

| 8. Vitamin D (25) | |||||||||||||

| 9. Water (25) | |||||||||||||

| Reference amounts/units | |||||||||||||

| Top 3 types of reference amounts or other units considered (% of models that include the reference amount/ unit)6 | 1. Per serving (76) | 1. Per serving (89) | 1. Per 100 g and/or mL (83) | 1. Per 100 g and/or mL (80) | 1. Per 100 g and/or mL (86) | 1. Per serving (100) | 1. Per serving (100) | 1. Per serving (100) | 1. Per serving (100) | 1. Per 100 g and/or mL (100) | 1. Per 100 g and/or mL (50) | N/A | N/A |

| 2. Presence/position (64) | 2. Presence/position (78) | 2. Per serving (58) | 2. Presence/position (60) | 2. Per serving (71) | 2. Per 100 g and/or mL (60) | 2. Presence/position (75) | 2. Presence/position (100) | 2. Per 100 g and/or mL (67) | 2. Per other prespecified amount (100) | 2. Per serving (50) | |||

| 3. Per 100 g and/or mL (60) | 3. Per 100 g and/or mL (44) | 3. Presence/position (50) | 3. Per serving (30) | 3. Per 419 kJ (i.e., 100 kcal) (43) | 3. Presence/position (60) | 3. Maximum size (50) | 3. Maximum size (50) | 3. Maximum size (33) | 3. Per serving (100) | ||||

| 4. Per 419 kJ (i.e., 100 kcal) (33) | 4. Presence/position (100) | ||||||||||||

| 5. Presence/position (33) | |||||||||||||

| Some degree of validity testing identified (e.g., content, construct/convergent, face, and/or criterion/predictive validity) | 33 (42) | 5 (19) | 7 (58) | 7 (70) | 5 (71) | 1 (20) | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Number of models derived from other models, either included or excluded, identified as part of the review | 34 (44) | 11 (41) | 5 (42) | 5 (50) | 4 (57) | 2 (40) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 3 (100) | 1 (50) | — | — | — |

| Number of models that served at least in part as the basis for the development of ≥1 other included model | 24 (31) | 11 (41) | 4 (33) | 4 (40) | 1 (10) | 1 (20) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | — | 1 (50) | — | — | — |

1Values are n (%) of models unless stated otherwise. A more detailed summary of the key characteristics of each model is provided in Table 5. Supplementary data also provide further details on the specific nutrients and food components “to limit” and “to encourage” included in each model (Supplemental Table 4) and on the specific types of reference amounts and other evaluation units used in each model (Supplemental Table 5). FVNL, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes; min-max, minimum–maximum; NP, nutrient profile; N/A, not applicable.

2Major food categories represented the first and sometimes only level of categories described in a model. In some models, ≥1 major category was subdivided into subcategories. In a few cases, ≥1 subcategory was further subdivided into sub-subcategories (e.g., Nordic Keyhole model, no. 11, in which the major category of meat and meat products includes 2 subcategories, and 1 of these also includes 3 sub-subcategories).

3Also implies food components.

4Nutrients are listed in descending order of the proportion of models that include them; alphabetical order was used when proportions were equal; therefore, the number of nutrients listed may be >3. N/A was used when the number of models evaluated was equal to 1.

5Calcium, FVNL, iron, magnesium, phosphorous, potassium, protein, riboflavin, vitamin A, vitamin B-12, vitamin C, vitamin D, and whole grain are all nutrients/food components included in both models evaluated.

6Reference amounts and other evaluation units are listed in descending order of the proportion of models that include them; alphabetical order was used when proportions were equal, therefore the number of reference amounts/units listed may be >3. N/A was used when the number of models evaluated was equal to 1. Presence/position refers to the presence (or absence) of a nutrient or food component in a product (e.g., no added sweeteners) or to its position in the ingredient list (e.g., the first ingredient must be a whole grain).

TABLE 5.

Summary characteristics of the 78 included NP models1

| Type of reference amount/unit considered | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model number | Model name | Type of model2 | Output3 | Category level(s) at which nutrient criteria are applied4 | Number of food categories with nutrient criteria5 | Model including only nutrients/food components to limit (A) or nutrients/food components to limit and to encourage (B)6 | Number/type of nutrients and food components may vary across the model's food categories/types of food product evaluated (Y/N) | Total nutrients/food components to limit7 | Total nutrients/food components to encourage7 | Per 100 g and/or per 100 mL | Per 419 kJ (i.e., 100 kcal) or % of energy | Per serving | Other reference amount or unit8 |

| School food (n = 27) | |||||||||||||

| 93 | National Healthy School Canteens Project | A | A | Major, sub | 6–239 | B | Y | 4 | 1 | Y | — | Y | — |

| 138 | Australia—Fresh Tastes @ School NSW Healthy School Canteens Strategy | A | A | Major, sub | 7310,11 | B | Y | 3 | 1 | Y | — | Y | — |

| 290 | Smart Choices: healthy food and drink supply strategy for Queensland schools—nutrient criteria for the “Occasional” (red) food and drink category | A | A | Sub | 7 | B | Y | 3 | 1 | Y | — | Y | — |

| 293 | South Australia Right Bite for schools and preschools—Nutrient criteria for the “Occasional” (red) category | A | A | Sub | 6 | B | Y | 3 | 1 | Y | — | Y | — |

| 140 | Australia—State Government of Victoria—Go For Your Life healthy canteen kit—nutrient criteria for the “Occasionally” (red) food category | A | A | Sub | 7 | B | Y | 3 | 1 | Y | — | Y | — |

| 393 | Canada—Provincial and Territorial nutrient criteria for foods and beverages in schools (2013) | A | A | Sub | 19 | B | Y | 10 | 3 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 131 | Alberta nutrition guidelines for children and youth | A | A | Sub | 25 | B | Y | 11 | 5 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 144 | Guidelines for food and beverage sales in BC schools | A | A | Sub | 21 | B | Y | 10 | 4 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 193 | Guidelines for foods available in K to 12 schools in Manitoba (criteria for packaged foods) | A | A | Major | 6 | B | Y | 8 | 6 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 241 | New Brunswick healthier foods and nutrition in public schools | A | A | Major, sub | 19 | B | Y | 9 | 8 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 180 | Food and beverage standards for Nova Scotia public schools | A | A | Major | 5 | B | Y | 8 | 2 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 259 | Ontario school food and beverage policy/program memorandum 150 (PPM 150) | A | A | Sub | 33 | B | Y | 9 | 6 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 272 | PEI school nutrition policy | A | A | Major | 5 | B | Y | 7 | 3 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 200 | Healthy eating guidelines for Saskatchewan schools (Nourishing Minds) | A | A | Major | 5 | B | Y | 5 | 9 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 72 | Costa Rica school food regulations | A | A | Sub | 17 | A | Y | 7 | 0 | Y | — | — | Y |

| 167 | Czech Republic draft decree for food sold and advertised in schools | A | A | Major, sub | 16 | B | Y | 8 | 7 | Y | — | — | Y |

| 59 | New School Canteen Standards | A | A | Major, sub | 18 | B | Y | 9 | 0 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 205 | Hong Kong nutritional criteria for snack classification | A | A | Sub, sub-sub | 12 | B | Y | 9 | 1 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 211 | FSSAI draft guidelines for making available wholesome, nutritious, safe and hygienic food to schoolchildren in India | A | A | Major | 2 | A | N | 6 | 0 | — | — | Y | — |

| 70 | Food and beverage classification system nutrient criteria (Fuelled4life) | A | A | Sub | 38 | B | Y | 11 | 2 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 76 | Healthy meals in schools program (Eating Healthily At The School Canteen) | A | A | Major, sub | 2 | B | Y | 12 | 8 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 60 | Scotland nutritional requirements for food and drink in schools | A | A | Major, sub | 1611 | B | Y | 8 | 1 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 61 | England requirements for school food regulations | A | A | Major, sub | 1011 | B | Y | 5 | 3 | — | — | — | Y |

| 325 | USDA smart snacks in school nutrition standards (also known as competitive food standards) | A | A | Major, sub | 10 | B | Y | 10 | 4 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 352 | California's nutrition standards SB12 and SB965 (competitive food and beverage standards for schools) | A | A | Major, sub12 | 5–813 | B | Y | 10 | 14 | — | Y | Y | Y |

| 163 | Connecticut nutrition standards | A | A | Major, sub | 13 | B | Y | 10 | 5 | — | Y | Y | Y |

| 248 | Eat Smart: North Carolina's recommended standards for all foods available in school | A | A | Major, sub | 3–414 | B | Y | 6 | 4 | — | Y | Y | Y |

| Front-of-pack food labeling (n = 12) | |||||||||||||

| 53 | Choices | A | A | Major, sub | 31 | B | Y | 5 | 1 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 196 | Health Star Rating System | C | C | Sub | 6 | B | N | 4 | 3 | Y | — | — | — |

| 156 | Chile “Black Octagonal Stop-Sign” warning labels | B | A | Major | 2 | A | N | 4 | 0 | Y | — | — | — |

| 172 | Ecuador traffic light labelling system | B | A | Major | 2 | A | N | 3 | 0 | Y | — | — | — |

| 27 | Heart symbol | A | A | Sub | 75 | B | Y | 10 | 3 | Y | Y | — | Y |

| 178 | Five-Colour Nutrition Label (5-CNL/Nutri-Score) | A | C | Major | 2 | B | N | 4 | 3 | Y | — | — | — |

| 73 | Healthier Choice Symbol program | C | A | Sub, sub-sub | 99 | B | Y | 11 | 8 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 11 | Keyhole | A | A | Major, sub, sub-sub | 46 | B | Y | 10 | 6 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 314 | United Arab Emirates nutrition labeling model (Weqaya logo) | A | A | Major, sub | 20 | B | Y | 12 | 3 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 41 | Traffic light labelling | B | A | Major | 2 | A | N | 4 | 0 | Y | — | Y | — |

| 1 | Fruits & veggies—More Matters | A | A | Major | 3 | B | Y | 4 | 2 | — | Y | Y | Y |

| 291 | Smart Meal Seal nutrition criteria | A | A | Major | 2 | B | N | 5 | 3 | — | — | Y | Y |

| Restriction of marketing to children (n = 10) | |||||||||||||

| 334 | WHO nutrient profile model for the Western Pacific Regional Office (WHO-WPRO) | A | A | Major, sub | 21 | A | Y | 8 | 0 | Y | — | — | Y |

| 335 | WHO Regional Office for Europe nutrient profile model (WHO-EURO) | A | A | Major, sub | 20 | A | Y | 8 | 0 | Y | — | — | Y |

| 388 | PAHO nutrient profile model (WHO Regional Office for the Americas) | C | A | Major | 1 | A | N | 6 | 0 | — | Y | — | Y |

| 62 | Danish Code of responsible food marketing communication to children | A | A | Major | 10 | A | Y | 2 | 0 | Y | — | — | Y |

| 220 | Ireland—broadcasting authority model for restricting the marketing of food and drink to children | A | C | Major | 2 | B | N | 4 | 3 | Y | — | — | — |

| 44 | South Korea—guideline for energy-dense, nutrition -poor food for children | A | A | Major | 2 | B | Y | 4 | 1 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 392 | Mexico—restriction on the promotion of high-caloric-density foods | A | A | Major, sub | 31 | B | Y | 5 | 1 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 251 | Norwegian nutrient profile model | A | A | Major | 8 | B | Y | 7 | 1 | Y | — | — | Y |

| 287 | Singapore common nutrition criteria of the guidelines for food advertising to children | A | A | Major, sub, sub-sub | 27 | B | Y | 7 | 8 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 5 | Ofcom model for regulating the marketing of food to children, final version (WXYfm) | A | C | Major | 2 | B | N | 4 | 3 | Y | — | — | — |

| Regulation of claims (n = 7) | |||||||||||||

| 20 | FSANZ—nutrient profiling scoring criterion | A | C | Major | 3 | B | N | 4 | 3 | Y | — | Y | — |

| 69 | The SAIN, LIM system | A | C | Major | 1 | B | N | 3 | 5 | Y | Y | — | Y |

| 75 | Singapore—nutrient- specific diet-related health claims | A | A | Sub, sub-sub | 99 | B | Y | 11 | 8 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 394 | South Africa nutrient profile model (FSANZ validated in South Africa) | A | C | Major | 3 | B | N | 4 | 3 | Y | — | — | — |

| 18 | US—requirements for foods carrying a health claim | A | A | Major | 3 | B | N | 4 | 6 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 35 | US—definition of a “healthy” food as an implied nutrient content claim | A | A | Major | 6 | B | Y | 4 | 6 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 319 | US—requirements for the “extra lean” and “lean” nutrient content claims | A | A | Major | 4 | A | N | 3 | 0 | Y | — | Y | — |

| Health facilities (n = 5) | |||||||||||||

| 381 | Queensland Health's A better choice – healthy food and drink supply strategy (2007)—nutrient criteria for the red category | A | A | Major, sub, sub-sub | 9 | B | Y | 4 | 1 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 367 | Healthy food and drink choices for staff and visitors in South Australia health facilities—nutrient criteria for the red category | A | A | Major, sub, sub-sub | 9 | B | Y | 4 | 1 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| 160 | Colchester East Hants Health Authority food and beverage nutrient standards | A | A | Major | 7 | B | Y | 9 | 2 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 285 | Scotland nutritional standards for hospital food: Food in Hospitals | A | A | Major | 3 | B | Y | 3 | 2 | — | — | Y | Y |

| 201 | Healthy food environments pricing incentives nutrition criteria | A | A | Major | 715 | B | Y | 8 | 1 | Y | — | Y | Y |

| Government facilities (n = 4) | |||||||||||||