Abstract

This cohort study examines the association of androgen deprivation therapy with dementia in male veterans with prostate cancer who receive definitive radiotherapy.

There is conflicting evidence on the association of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and dementia.1,2,3,4 Two studies1,2 reported a strong statistically significant association between ADT and both dementia and Alzheimer disease in patients with prostate cancer (PC). However, these studies1,2 analyzed heterogeneous populations, including patients with localized and metastatic disease, treated with curative and palliative intent, and ADT use in the upfront or recurrent setting.1,2 Different treatment modalities and disease stages are associated with substantial selection bias that may predispose results to false associations.5 Furthermore, an association between ADT use and dementia in the recurrent or metastatic setting may be confounded by factors, such as chronic pain, or salvage treatments, such as chemotherapy. We hypothesized that there is no statistically significant association between ADT use and the development of dementia in men with PC who received definitive radiotherapy after controlling for multiple sources of selection bias.

Methods

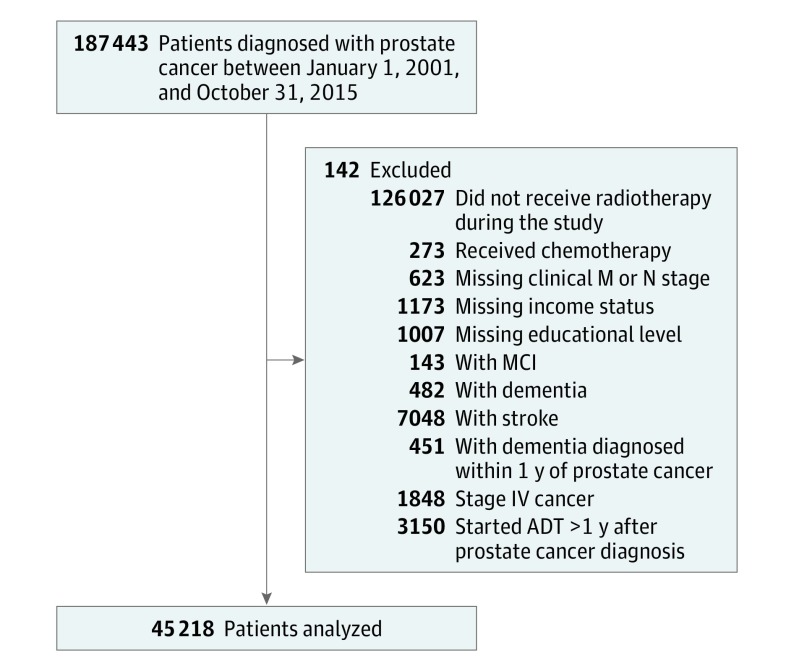

This observational cohort study included men diagnosed with nonmetastatic PC at the US Department of Veterans Affairs from January 1, 2001, to October 31, 2015, who received definitive radiotherapy with or without ADT (Figure). We excluded patients with a prior diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, stroke, and dementia or a diagnosis of dementia within 1 year of PC diagnosis. Patients who underwent other treatment modalities, including radical prostatectomy, or who did not receive definitive treatment were excluded. Patients who initiated ADT more than 1 year after their PC diagnosis were excluded to avoid inclusion of patients with metastatic disease. Finally, patients who received chemotherapy as a component of their treatment were excluded because chemotherapy may be related to the development of dementia. This study was reviewed, approved, and granted a waiver of consent and authorization by the Veterans Affairs San Diego Health Care System. All data were deidentified.

Figure. Cohort Flowchart.

ADT indicates androgen deprivation therapy; and MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

The use of ADT in veterans with PC was assessed in a Fine-Gray competing risks regression model through subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs), and we considered death from any cause as a competing event to development of dementia. We assumed a 2-sided α = .05.

The primary outcome was new development of any form of dementia. Secondary outcomes included vascular dementia and Alzheimer disease. These outcomes were modeled as a function of ADT use, age, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, statin use, antiplatelet use, antihypertensive use, alcohol use, substance use, race, smoking status, region, income, educational level, and year of diagnosis. Sensitivity analysis with a time-varying definition of ADT was also conducted.

Results

The cohort included 45 218 men followed up for a median of 6.8 years (interquartile range, 4.1-9.9 years). During the study follow-up, 1497 patients were diagnosed with any dementia. Of these, 335 had vascular dementia, 404 had Alzheimer disease, and 758 had other or unclassified dementia. There was no statistically significant association between ADT use and any dementia (SHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94-1.16; P = .43), vascular dementia (SHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.97-1.50; P = .10), or Alzheimer disease (SHR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.91-1.36; P = .29) (Table). Furthermore, no association was found between ADT length of 1 year or less with any dementia (SHR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.89-1.15; P = .89) and ADT length greater than 1 year with any dementia (SHR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.95-1.24; P = .21) (Table). A sensitivity analysis using time-varying ADT exposure revealed no significant association between ADT and any dementia (SHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94-1.16; P = .43), vascular dementia (SHR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.97-1.50; P = .09), and Alzheimer disease (SHR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.91-1.35; P = .29).

Table. Association Between Androgen Deprivation Therapy and Dementia.

| ADT Exposure | New Diagnosis of Dementia, No. (Crude %) | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADT Group | Non-ADT Group | |||

| Any Dementia | ||||

| ≤1 Year | 336 (54.0) | 875 (100) | 1.00 (0.89-1.14) | .92 |

| >1 Year | 286 (46.0) | 875 (100) | 1.09 (0.95-1.25) | .22 |

| Total | 622 (100) | 875 (100) | 1.04 (0.94-1.16) | .43 |

| Vascular Dementia | ||||

| ≤1 Year | 85 (55.6) | 182 (100) | 1.21 (0.94-1.57) | .14 |

| >1 Year | 68 (44.4) | 182 (100) | 1.19 (0.90-1.58) | .22 |

| Total | 153 (100) | 182 (100) | 1.20 (0.97-1.50) | .09 |

| Alzheimer Disease | ||||

| ≤1 Year | 105 (58.4) | 224 (100) | 1.17 (0.93-1.49) | .17 |

| >1 Year | 75 (41.6) | 224 (100) | 1.03 (0.79-1.34) | .82 |

| Total | 180 (100) | 224 (100) | 1.11 (0.91-1.36) | .29 |

Abbreviation: ADT, androgen deprivation therapy.

Discussion

Our cohort included more than 45 000 men who were treated in a relatively homogeneous fashion with definitive radiotherapy with or without ADT. The study has some limitations. First, because our cohort focused on radiotherapy-treated patients, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other patients with PC treated with other modalities. Second, our cohort included only veterans. Therefore, some differences in sociodemographic factors may exist that limit the generalizability of these results to the larger population of men with PC. We did not observe a statistically significant increase in risk of any dementia, vascular dementia, or Alzheimer disease. Furthermore, the effect sizes (SHRs, 1.00-1.21) were substantially lower than those seen in studies from Nead and colleagues1,2 (HRs, 1.66-2.32), suggesting that our results were not attributable to inadequate power to detect these differences. These results may mitigate concerns regarding the long-term risks of ADT on cognitive health in the treatment of PC.

References

- 1.Nead KT, Gaskin G, Chester C, et al. . Androgen deprivation therapy and future Alzheimer’s disease risk. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):566-571. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.6266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nead KT, Gaskin G, Chester C, Swisher-McClure S, Leeper NJ, Shah NH. Association between androgen deprivation therapy and risk of dementia. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):49-55. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baik SH, Kury FSP, McDonald CJ. Risk of Alzheimer’s disease among senior medicare beneficiaries treated with androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3401-3409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.6109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khosrow-Khavar F, Rej S, Yin H, Aprikian A, Azoulay L. Androgen deprivation therapy and the risk of dementia in patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(2):201-207. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.6203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams SB, Huo J, Chamie K, et al. . Discerning the survival advantage among patients with prostate cancer who undergo radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy: the limitations of cancer registry data. Cancer. 2017;123(9):1617-1624. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]