Key Points

Question

Does foster care intervention mitigate the long-term effects of institutional rearing on latent dimensions of psychopathology?

Finding

In this randomized clinical trial of 220 children, 119 of whom had histories of institutional rearing, those assigned to early foster care intervention had less problematic trajectories of general and externalizing-specific psychopathology from middle childhood (age 8 years) to adolescence (age 16 years).

Meaning

Social enrichment early in development reduces the risk of psychopathology among children with histories of profound neglect during a period of significant social and biological change.

This randomized clinical trial examines trajectories of latent psychopathology factors—general, internalizing, and externalizing—among children reared in institutions and evaluates whether randomization to foster care is associated with reductions in psychopathology from middle childhood through adolescence.

Abstract

Importance

It is unclear whether early institutional rearing is associated with more problematic trajectories of psychopathology from childhood to adolescence and whether assignment to foster care mitigates this risk.

Objectives

To examine trajectories of latent psychopathology factors—general (P), internalizing (INT), and externalizing (EXT)—among children reared in institutions and to evaluate whether randomization to foster care is associated with reductions in psychopathology from middle childhood through adolescence.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This longitudinal, intent-to-treat randomized clinical trial was conducted in Bucharest, Romania, where children residing in 6 institutions underwent baseline testing and were then randomly assigned to a care as usual group (CAUG) or a foster care group (FCG). A matched sample of a never-institutionalized group (NIG) was recruited to serve as a comparison group. The study commenced in April 2001, and the most recent (age 16 years) follow-up started in January 2015 and is ongoing.

Intervention

Institutionally reared children randomized to high-quality foster homes.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Psychopathology was measured using the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. Teachers and/or caregivers reported on symptoms of psychopathology in several domains.

Results

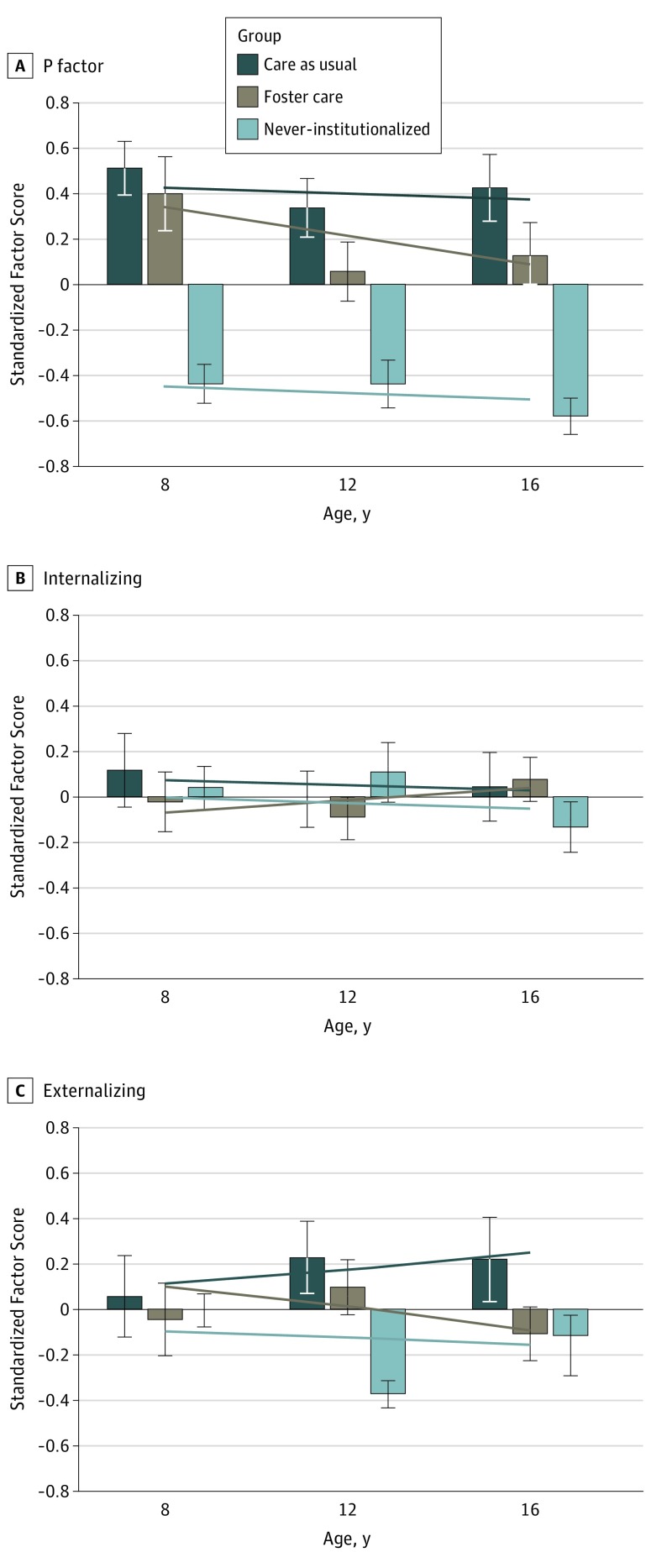

A total of 220 children (50.0% female; 119 ever institutionalized) were included in the analysis at the mean ages of 8, 12, and 16 years. A latent bifactor model with general (P) and specific internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) factors offered a good fit to the data. At age 8 years, CAUG (mean, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.17-0.67) and FCG (mean, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.04-0.53) had higher P than NIG (mean, −0.40; 95% CI, −0.56 to −0.18). By age 16 years, FCG (mean, 0.07; 95% CI, −0.18 to 0.29) had lower P than CAUG (mean, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.13-0.60). This effect was likely driven by modest declines in P from age 8 years to age 16 years among FCG (slope, −0.12; 95% CI, −0.26 to 0.04) compared with CAUG, who remained stably high over this period (slope, −0.02; 95% CI, −0.19 to 0.14). Moreover, CAUG and FCG showed increasing divergence in EXT over time, such that FCG (mean, −0.30; 95% CI, −0.58 to −0.02) had fewer problems than CAUG (mean, 0.05; 95% CI, −0.25 to 0.36) by age 16 years. No INT differences were observed.

Conclusions and Relevance

Institutionalization increases transdiagnostic vulnerability to psychopathology from childhood to adolescence, a period of significant social and biological change. Early assignment to foster care partially mitigates this risk, thus highlighting the importance of social enrichment in buffering the effects of severe early neglect on trajectories of psychopathology.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00747396

Introduction

Children who experience early psychosocial neglect are at risk for a host of socioemotional, cognitive, and behavioral difficulties. Such is the case for children reared in institutions typified by high ratios of children to caregivers, high caregiver turnover, frequent isolation, regimentation, and inadequate social and cognitive stimulation. Children reared in institutions have significantly higher rates of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders than never-institutionalized children, including depression, anxiety, disruptive behavior disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.1,2,3

Early foster care placement has been shown to partially mitigate the negative psychiatric outcomes of institutionally reared children. Some of the best evidence for these effects comes from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP), the only existing randomized clinical trial (RCT) to date of foster care as an alternative to institutional care. Results from BEIP suggest that children randomly assigned to foster care have fewer internalizing problems at age 54 months compared with children who remain in institutions.3 Eight years later, lower risk of externalizing problems was the primary intervention effect.4 Therefore, foster care appears to reduce the risk of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology at different periods of development, with the possibility of “sleeper effects,” in which the benefits of foster care may not fully manifest until later in development.

Several issues remain unresolved in the extant literature. The first is whether longitudinal trajectories of psychopathology differ between never-institutionalized and ever-institutionalized children and whether foster care intervention is associated with different patterns of growth over time. Little is known about the mental health trajectories of institutionalized children, in part because there are so few longitudinal studies in this field. The English and Romanian Adoptees study5 recently showed that children who spent more than 6 months in institutions had similar rates of emotional problems compared with never-institutionalized children from ages 6 to 15 years, with a late onset of problems during the transition to adulthood. A similar, although less pronounced, pattern was observed for conduct problems. Furthermore, early-emerging and persistent problems with inattention and overactivity were observed in those with longer compared with shorter periods of deprivation.

Unlike other studies of postinstitutionalized children, the randomized design of BEIP provides an experimental model of the effects of institutionalization and foster care placement on psychopathology. The advantage of randomization is that children assigned to foster care and those who remain in institutions share preexisting risk factors. Therefore, differences in outcomes can be attributed to the intervention. The recent completion of the adolescent follow-up (age 16 years) in BEIP allows us to chart trajectories of psychopathology in this unique sample from middle childhood to adolescence, a period of considerable social and biological change.6

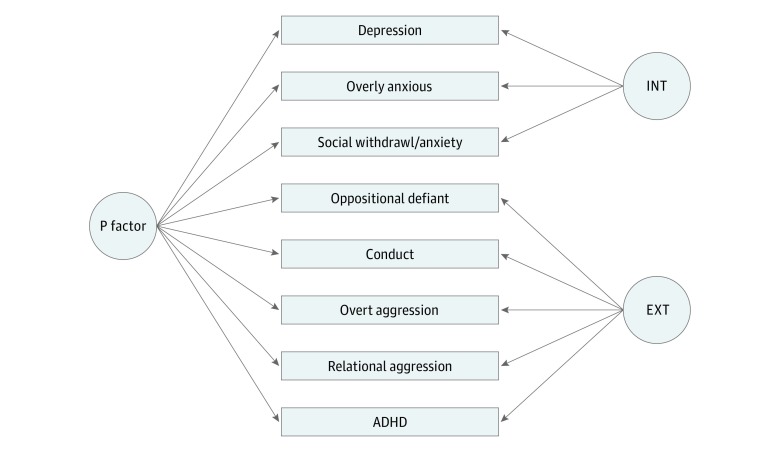

Our measurement of psychopathology follows a corpus of recent research that has revealed the presence of latent general (P) and specific internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) factors.7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Estimation of these factors is accomplished through latent bifactor modeling.14 This approach allows researchers to determine whether certain risk factors are transdiagnostically linked to several conditions via their association with P or whether they show specific associations with INT or EXT. The present study examined trajectories of these psychopathology factors among previously institutionalized children and hypothesized that those assigned to early foster care would demonstrate less problematic patterns of change than those with prolonged institutional rearing.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The original trial was an RCT of abandoned children living in 6 institutions in Bucharest, Romania. After approval by the institutional review boards of the 3 principal investigators (N.A.F., C.H.Z., and C.A.N.) and by the local Commissions on Child Protection in Bucharest, the study started in collaboration with the Institute of Maternal and Child Health of the Romanian Ministry of Health. Children were aged 6 to 31 months at baseline testing (mean age, 22 months). After this testing, half of them were randomly assigned to a care as usual group (CAUG [remained in institutions]) and half were randomly assigned to a high-quality foster care group (FCG) by drawing names from a hat. The CAUG and FCG did not differ on key baseline characteristics (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Given the nature of the study, masking of group assignments to children, their caregivers, and study investigators was not possible. A matched sample of a never-institutionalized group (NIG) reared in their biological families was recruited to serve as a comparison group. Details about the original sample and ethical implications of the project are available elsewhere.15,16 Signed informed consent was obtained from each child’s legal guardian, and written or verbal assent was obtained from each child (trial protocol in Supplement 2). Demographic characteristics for each group are listed in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. The study commenced in April 2001, and the most recent (age 16 years) follow-up started in January 2015 and is ongoing.

Procedures

Because Bucharest had almost no foster homes at trial commencement, BEIP investigators created a foster care network in collaboration with Romanian officials.17 After advertising and screening, 56 foster families were selected to care for 68 children. Foster care intervention was designed to be affordable, replicable, and grounded in empirical research on development-enhancing caregiving. Foster parents were supported by social workers in Bucharest who provided regular family visits to train caregivers on how to appropriately respond to the emotional and behavioral needs of their children.18 Throughout the trial, a noninterference policy was adopted so that CAUG children were able to transition to a family setting if the opportunity arose (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

Group assignment and follow-up measurement in the randomized clinical trial. BEIP indicates Bucharest Early Intervention Project; CAUG, care as usual group; FCG, foster care group; HBQ, MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire; and NIG, never-institutionalized group.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes of the trial included several measures of cognition, physical growth, and psychiatric symptoms. At age 54 months, support of the foster families was taken over by local child protection authorities. Participants were followed up at 8, 12, and 16 years. At the time of the initial trial, no prespecifications were made with respect to follow-up analyses of psychopathology.

For the present study, the primary outcome was psychopathology, measured using the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire19 at ages 8, 12, and 16 years. At age 8 years, reporters were the children’s teachers; at ages 12 and 16 years, both teachers and caregivers reported on problems, which were standardized and combined into a composite score to reduce rater bias. Teachers and caregivers responded to several items on a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (“never or not true”) to 2 (“often or very true”). Subscales included the following: depression, overly anxious, social withdrawal/anxiety, oppositional defiant, conduct, overt aggression, relational aggression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (details are available at the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development website20).

Statistical Analysis

All models were estimated using statistical software (Mplus, version 7.3; Muthén & Muthén). The analyses were conducted in 2 steps. First, latent bifactor models14 were fit at ages 8, 12, and 16 years to examine the latent structure of psychopathology. For this step, each domain of psychopathology was set to load onto the P factor and its specific INT or EXT factor simultaneously (Figure 2), and factors were forced to orthogonality. As is common in ratings of psychopathology, some of the scales were positively skewed; therefore, the analyses were performed using robust maximum likelihood estimation, which yields parameter estimates with standard errors and a χ2 statistic that are robust to nonnormality when missing data are present.21

Figure 2. Latent Structure of Psychopathology as Estimated Using Latent Bifactor Modeling.

In this conceptual model, all domains of psychopathology are set to load onto general (P) and their specific internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) factors simultaneously. These factors are forced to orthogonality during model estimation. At each age (8, 12, and 16 years), this model offered the best fit to the data, and the pattern of loadings was similar (results are presented in eTable 4 in Supplement 1). ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Second, the factor scores derived from the models described in the first step were used to examine trajectories of latent psychopathology factors (P, INT, and EXT) over time. For this analysis, multigroup latent growth modeling (LGM) within a Bayesian framework was used to estimate growth parameters (intercept and slope) within and between CAUG, FCG, and NIG groups. Pairwise comparisons at each time point were evaluated by resetting the intercept to the age of interest within the LGM model. In this longitudinal RCT, an intent-to-treat approach was used to compare CAUG and FCG children. We report 1-tailed P values based on the posterior distributions and the 95% Bayesian credibility interval. All models controlled for children’s sex (0 for female and 1 for male) and birth weight (in grams). There were some missing data over time. Any child who contributed data at 1 or more time points was included in the analysis, for a total of 220 children (58 CAUG, 61 FCG, and 101 NIG). There were 195 children who contributed data at age 8 years (44 CAUG, 52 FCG, and 99 NIG), 162 at age 12 years (56 CAUG, 56 FCG, and 50 NIG), and 149 at age 16 years (49 CAUG, 52 FCG, and 48 NIG). Missing data were handled using Bayesian estimation, which is akin to full information maximum likelihood estimation. This method outperforms other methods for handling missing data, such as listwise deletion, pairwise deletion, and mean substitution in terms of parameter bias, convergence, and model fit.22

Results

Bifactor Model and Descriptive Statistics

A total of 220 children (50.0% female; 119 ever institutionalized) contributed data at 1 or more of the age 8-year, 12-year, and 16-year assessments. Results of the bifactor analysis are provided in Supplement 1 (model fit in eTable 3 in Supplement 1 and individual loadings in eTable 4 in Supplement 1). In brief, all bifactor models offered a good fit to the data and were a better reflection of the latent structure of psychopathology than 1-factor or 2-factor models. Configural, metric, and partial scalar invariance was established across time, suggesting that interpretation of the factors is largely isomorphic at each age23 (Supplement 1).

Bivariate associations between the psychopathology factors and other child characteristics are listed in Table 1. There was significant rank order stability in P, INT, and EXT across ages, especially from age 12 years to age 16 years. Lower birth weight was associated with higher P at all ages, and male sex was associated with higher P at all ages and with higher EXT at age 12 years and age 16 years. This finding supported our inclusion of sex and birth weight as covariates in the latent growth analysis. Neither age when children entered the institutions nor age at placement into foster care was associated with any of the latent psychopathology factors.

Table 1. Bivariate Correlations Between the Psychopathology Factors and Child Characteristics.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 P, age 8 y | ||||||||||||

| 2 INT, age 8 y | 0.00 | |||||||||||

| 3 EXT, age 8 y | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| 4 P, age 12 y | 0.29a | 0.00 | −0.09 | |||||||||

| 5 INT, age 12 y | −0.23a | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.15b | ||||||||

| 6 EXT, age 12 y | 0.37c | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.25a | |||||||

| 7 P, age 16 y | 0.46c | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.54c | −0.09 | 0.33c | ||||||

| 8 INT, age 16 y | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.10 | 0.17b | 0.36c | −0.09 | 0.15b | |||||

| 9 EXT, age 16 y | 0.26a | −0.15 | 0.35c | 0.10 | −0.13 | 0.37c | 0.13 | −0.23a | ||||

| 10 Sex, male | 0.15d | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.16d | 0.01 | 0.24a | 0.21d | −0.04 | 0.18d | |||

| 11 Birth weight | −0.23a | −0.09 | 0.23a | −0.22a | −0.13 | −0.11 | −0.15b | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.07 | ||

| 12 Age when entered institution | 0.15 | 0.13 | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.22 | 0.13 | −0.07 | −0.14 | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.01 | |

| 13 Age at placement into foster caree | −0.07 | 0.16 | 0.09 | −0.14 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.29d | 0.26b | 0.29d |

Abbreviations: EXT, externalizing; INT, internalizing; P, general.

P < .01.

P < .10.

P < .001.

P < .05.

Correlation is only within the foster care group.

Latent Growth Model of P, INT, and EXT

Parameters of the LGM, including within-group and between-group comparisons on intercepts and slopes, are listed in Table 2. The pattern of these effects is shown in Figure 3, which presents both observed and model-estimated differences across ages. The model-estimated differences are the focus of the present analysis. At age 8 years (intercept), NIG had significantly lower general psychopathology (P) than both CAUG and FCG, who did not differ from one another. In terms of within-group rate of change, FCG demonstrated modest declines in P from age 8 years to age 16 years, while CAUG remained stably high and NIG stably low. There were no significant slope differences between groups. Beginning at age 12 years and continuing through age 16 years, FCG had lower P than CAUG but still had higher P than NIG. Therefore, there was evidence that general psychopathology among those assigned to early foster care declined modestly across the transition to adolescence, eventuating in reduced liability to P compared with those who remained in institutions.

Table 2. Growth Parameters for P, INT, and EXT Within and Between Groups From Age 8 Years to Age 16 Yearsa.

| Variable | Intercept | Group Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAUG (95% CI) | FCG (95% CI) | NIG (95% CI) | ||

| P | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| 8 | 0.41 (0.17 to 0.67)b | 0.30 (0.04 to 0.53)c | −0.40 (−0.56 to −0.18)b | NIG < CAUG,b FCGb |

| 12 | 0.38 (0.20 to 0.59)b | 0.18 (−0.01 to 0.37)c | −0.43 (−0.58 to −0.27)b | NIG < CAUG,b FCGb FCG < CAUGd |

| 16 | 0.37 (0.13 to 0.60)e | 0.07 (−0.18 to 0.29) | −0.47 (−0.72 to −0.24)b | NIG < CAUG,b FCGb FCG < CAUGc |

| Slope, ages 8-16 y | −0.02 (−0.19 to 0.14) | −0.12 (−0.26 to 0.04)d | −0.04 (−0.18 to 0.11) | No differences |

| INT | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| 8 | 0.07 (−0.17 to 0.30) | −0.11 (−0.36 to 0.11) | 0.04 (−0.13 to 0.22) | No differences |

| 12 | 0.04 (−0.12 to 0.20) | −0.05 (−0.21 to 0.11) | 0.01 (−0.13 to 0.15) | No differences |

| 16 | 0.03 (−0.20 to 0.27) | 0.03 (−0.21 to 0.25) | −0.04 (−0.27 to 0.20) | No differences |

| Slope, ages 8-16 y | −0.02 (−0.20 to 0.16) | 0.06 (−0.11 to 0.24) | −0.04 (−0.19 to 0.12) | No differences |

| EXT | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| 8 | 0.13 (−0.12 to 0.44) | 0.16 (−0.11 to 0.39) | −0.17 (−0.36 to 0.07)d | NIG < CAUG,c FCGc |

| 12 | 0.10 (−0.11 to 0.32) | −0.07 (−0.28 to 0.15) | −0.25 (−0.42 to −0.06)e | NIG < CAUG,c FCGd FCG < CAUGd |

| 16 | 0.05 (−0.25 to 0.36) | −0.30 (−0.58 to −0.02)c | −0.35 (−0.66 to −0.05)e | CAUG > NIG,c FCGc |

| Slope, ages 8-16 y | −0.04 (−0.26 to 0.15) | −0.23 (−0.39 to −0.05)e | −0.08 (−0.26 to 0.08) | FCG > CAUGd,f |

Abbreviations: CAUG, care as usual group; EXT, externalizing; FCG, foster care group; INT, internalizing; NIG, never-institutionalized group; P, general.

All effects are based on 1-tailed directional tests and control for sex and birth weight. Coefficients are unstandardized, and covariates (sex and birth weight) are centered. Controlling for ethnicity did not substantively alter the pattern of results.

P < .001.

P < .05.

P < .10.

P < .01.

This difference indicates that EXT of FCG declines at a quicker rate than CAUG.

Figure 3. Latent Growth Model Showing Trajectories of Psychopathology Across Groups.

Trajectories of general (P) (A), internalizing (B), and externalizing (C) psychopathology from age 8 years to age 16 years. Bars represent observed means at each age. Lines represent model-estimated trajectories. Error bars are standard errors.

After accounting for P, there were no group differences on INT in terms of mean differences at any given time point (intercepts at ages 8, 12, and 16 years) and no evidence of significant change over time within or between groups. In other words, INT problems did not differ across CAUG, FCG, and NIG from age 8 years to age 16 years after accounting for variance in P.

Finally, at age 8 years (intercept), NIG had significantly lower EXT than both CAUG and FCG, who did not differ from one another. In terms of rate of change, FCG showed significant declines in EXT from age 8 years to age 16 years, while CAUG did not show significant changes. By age 16 years, FCG had significantly fewer EXT problems than CAUG and were not statistically different from NIG. An alternative model with 2 correlated factors (internalizing and externalizing) is presented in the eFigure and eTable 5 in Supplement 1 and is consistent with the results from the primary bifactor analyses.

Discussion

The present study used data from the only existing RCT to date of foster care intervention for institutionally reared children to examine trajectories of latent psychopathology factors from childhood to adolescence. Children randomly assigned to remain in institutions (CAUG), as well as those assigned to early foster care (FCG), had higher general psychopathology (P) compared with never-institutionalized children at ages 8, 12, and 16 years. While CAUG and FCG did not differ on their level of general psychopathology at age 8 years, differences began to emerge by age 12 years; by age 16 years, FCG had significantly lower P than CAUG. These group differences are likely explained by the finding that FCG showed modest declines in P from age 8 years to age 16 years, while CAUG remained stably high on this factor. These results provide strong evidence that early foster care is associated with less problematic trajectories of general psychopathology from middle childhood to adolescence, a period of pronounced social and biological change.

Because P captures what is common across disorders, any risk variable that predicts P can be thought of as a transdiagnostic vulnerability factor. Previous studies24,25 have identified several transdiagnostic risks, including social class, economic deprivation, family history of psychiatric disorder, child maltreatment, and stress exposure. Exposure to various types of adversity in adolescence have also been linked to increased P in adulthood, including family violence, peer violence, crime subjection, sexual abuse, and neglect.26 The present results add to this growing literature by providing the first evidence to date that profound psychosocial deprivation as a function of early institutionalization increases transdiagnostic liability to psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. Moreover, these effects appear to be at least partially amenable to foster care intervention, suggesting that, whatever P is indexing, it is not immutable. Converging evidence suggests that P is underpinned by dysregulation of emotion and cognition.10,12,27,28 Therefore, it is conceivable that institutional rearing engenders broad deficits in emotion dysregulation, which increase vulnerability to multiple psychiatric problems, but that early placement into socially enriching environments enhances the regulatory competencies that mitigate risk for later psychopathology. It is also possible that transdiagnostic interventions aiming to address multiple simultaneous difficulties with universal therapeutic protocols may prove especially beneficial for children with high levels of P, including those with histories of adversity.29

Lower birth weight and male sex were associated with higher P in the present study. While the latter effect has been reported previously,30 not all studies have shown this result,24 and future research should aim to determine under what conditions sex is associated with heightened risk for general and specific psychopathology. The relation between lower birth weight and P—which became weaker over time—is consistent with meta-analytic studies demonstrating higher risk of internalizing and externalizing problems among children born preterm or low birth weight.31 While not a primary focus of the present study, these results highlight the possibility of shared etiological factors in the emergence of different psychiatric conditions via P, including conditions related to fetal growth and development.

In contrast to P, there were no group differences on INT (either on the means or rate of change) after P variance was accounted for. Review studies of international adoptees have revealed mixed findings with respect to internalizing psychopathology in childhood,32 with problems becoming more prevalent in adolescence.33 Recent longitudinal work suggests that the largest differences between institutionalized and noninstitutionalized children on emotional problems are observed between age 15 years and young adulthood.5 Therefore, it is plausible that follow-up into young adulthood in our RCT will yield significant differences in INT psychopathology. Another interpretation of the present results is that previous findings of increased INT among ever-institutionalized children were actually capturing an unaccounted-for liability to general psychopathology characterized by deficits in emotional processing attributable to P. There is evidence that postinstitutionalized children who spend longer periods in orphanages have poorer self-regulation in the context of emotionally arousing stimuli than noninstitutionalized children.34 Children reared in institutions also display more negative affect than community controls.18 Therefore, negative emotionality and emotion dysregulation may be transdiagnostic endophenotypes that confer vulnerability to several psychiatric conditions via P, with little INT specificity once this general liability is accounted for.

Finally, NIG demonstrated lower EXT at 8 years than CAUG and FCG, who did not differ from one another. Emerging differences between CAUG and FCG at age 12 years became full-fledged by age 16 years, at which time FCG had lower EXT than CAUG, and FCG were indistinguishable from NIG. These results complement prior findings from BEIP showing that FCG had fewer externalizing symptoms than CAUG at age 12 years.4 The present study advances these findings by demonstrating continued divergence in EXT among previously institutionalized children, with declining levels for FCG but stably high levels for CAUG during this formative period of individuation. It has been suggested that high approach-related traits may underlie susceptibility to and overlap of externalizing disorders.35,36,37,38 Determining whether the intervention effects documented herein are mediated by recovery in the biobehavioral systems that modulate approach-related traits is a critical question for the next wave of research in this area.

Limitations

These results should be considered in light of several limitations. First, our assessment of psychopathology relied on teacher and caregiver ratings. Although combining teacher and caregiver ratings reduces the risk of single-rater bias, replication using interviewer-based assessments is encouraged. Second, there were some missing data over time. This was minimized by using best-practice methods for handling missing data, but studies with larger samples and minimal attrition are warranted. Third, the small sample may have limited our ability to detect certain effects. For instance, there is some evidence for “sensitive periods,” in which the harmful effects of institutionalization are most prominent for children receiving institutional care beyond 6 months5 or 24 months,39 depending on the study. We did not see a relation between the age when children entered the institutions or the timing at which they left the institutions for foster care and any of the psychopathology factors, consistent with previous reports3 (Table 1). Future studies should focus on elucidating which individuals respond most favorably to early removal from institutions and the outcomes that are most amenable to early intervention. Fourth, the meaning of the residual INT and EXT factors derived from bifactor models is less clear than for traditional internalizing and externalizing dimensions, which have a long history in the psychiatric literature.26 As research on the hierarchical structure of psychopathology expands, additional studies should explicitly compare and contrast the biological, cognitive, personality, and socioemotional correlates of traditional and residual INT and EXT factors as a means of better characterizing the shared and unique pathways to different syndromes and disorders. Fifth, this sample of institutionalized children is unique, and generalizability of the present findings to other forms of early adversity cannot be assumed. Likewise, we cannot rule out the possibility that the effects reported herein are limited to children experiencing gross and pervasive deprivation, for which the deleterious effects of institutionalization may be especially pronounced.40 Uncovering the consequences of institutional rearing under conditions of less pervasive deprivation is an important next step in this field.

Conclusions

Severe early psychosocial deprivation has negative long-term consequences for psychopathology. In particular, children reared in institutions are at an increased risk for both general and EXT–specific psychopathology, effects that are observed years after removal from institutions. However, early intervention is associated with less problematic trajectories of psychopathology from age 8 years to age 16 years, ultimately resulting in lower levels of problems by the time children reach adolescence. This study provides strong evidence that the beneficial effects of foster care grow incrementally over time and may promote healthy adaptation during a formative period of neurophysiological reorganization.41 Elucidating how these neurophysiological systems map onto long-term trajectories of psychopathology is a crucial area for future research.

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of Institutionally-Reared Children

eTable 2. Demographic Characteristics of Children in the Current Study

eTable 3. Fit Information for One-, Two-, and Bifactor Models at Age 8, 12, and 16

eTable 4. Factor Loadings for the Bifactor Models at Age 8, 12, and 16

eFigure. Latent Growth Model for Correlated Factors Model

eTable 5. Growth Parameters for the Correlated-Factors Model With Internalizing and Externalizing Dimensions Only

eReferences.

Trial Protocol

References

- 1.Gunnar MR, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Beckett C, et al. A commentary on deprivation-specific psychological patterns: effects of institutional deprivation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2010;75(1):232-247. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens SE, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Kreppner JM, et al. Inattention/overactivity following early severe institutional deprivation: presentation and associations in early adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36(3):385-398. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9185-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeanah CH, Egger HL, Smyke AT, et al. Institutional rearing and psychiatric disorders in Romanian preschool children. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):777-785. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08091438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humphreys KL, Gleason MM, Drury SS, et al. Effects of institutional rearing and foster care on psychopathology at age 12 years in Romania: follow-up of an open, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(7):625-634. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00095-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonuga-Barke EJS, Kennedy M, Kumsta R, et al. Child-to-adult neurodevelopmental and mental health trajectories after early life deprivation: the young adult follow-up of the longitudinal English and Romanian Adoptees study. Lancet. 2017;389(10078):1539-1548. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30045-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(12):947-957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahey BB, Applegate B, Hakes JK, Zald DH, Hariri AR, Rathouz PJ. Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathology during adulthood? J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121(4):971-977. doi: 10.1037/a0028355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laceulle OM, Vollebergh WA, Ormel J. The structure of psychopathology in adolescence: replication of a general psychopathology factor in the TRAILS study. Clin Psychol Sci. 2015;3(6):850-860. doi: 10.1177/2167702614560750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patalay P, Fonagy P, Deighton J, Belsky J, Vostanis P, Wolpert M. A general psychopathology factor in early adolescence. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(1):15-22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.149591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tackett JL, Lahey BB, van Hulle C, Waldman I, Krueger RF, Rathouz PJ. Common genetic influences on negative emotionality and a general psychopathology factor in childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122(4):1142-1153. doi: 10.1037/a0034151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Keenan K, Stepp SD, Loeber R, Hipwell AE. Criterion validity of the general factor of psychopathology in a prospective study of girls. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(4):415-422. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martel MM, Pan PM, Hoffmann MS, et al. A general psychopathology factor (P factor) in children: structural model analysis and external validation through familial risk and child global executive function. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017;126(1):137-148. doi: 10.1037/abn0000205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olino TM, Dougherty LR, Bufferd SJ, Carlson GA, Klein DN. Testing models of psychopathology in preschool-aged children using a structured interview–based assessment. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42(7):1201-1211. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9865-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reise SP. The rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behav Res. 2012;47(5):667-696. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2012.715555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millum J, Emanuel EJ. Ethics: the ethics of international research with abandoned children. Science. 2007;318(5858):1874-1875. doi: 10.1126/science.1153822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, Fox NA, et al. Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavioral development: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Dev Psychopathol. 2003;15(4):885-907. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smyke AT, Zeanah CH Jr, Fox NA, Nelson CA III. A new model of foster care for young children: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(3):721-734. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyke AT, Koga SF, Johnson DE, et al. ; BEIP Core Group . The caregiving context in institution-reared and family-reared infants and toddlers in Romania. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):210-218. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Goldstein LH, Armstrong JM, Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ; MacArthur Assessment Battery Working Group . The confluence of mental, physical, social, and academic difficulties in middle childhood, II: developing the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(5):588-603. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development. https://www.macfound.org/networks/research-network-on-psychopathology-development/details/. Accessed August 6, 2018.

- 21.Yuan KH, Bentler PM. Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociol Methodol. 2000;30(1):165-200. doi: 10.1111/0081-1750.00078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Modeling. 2001;8(3):430-457. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Putnick DL, Bornstein MH. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: the state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Dev Rev. 2016;41:71-90. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, et al. The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2(2):119-137. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snyder HR, Young JF, Hankin BL. Chronic stress exposure and generation are related to the p factor and externalizing specific psychopathology in youth [published online May 25, 2017]. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1321002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer JD, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, et al. Adolescent victimization and early-adult psychopathology: approaching causal inference using a longitudinal twin study to rule out noncausal explanations. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6(3):352-371. doi: 10.1177/2167702617741381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castellanos-Ryan N, Brière FN, O’Leary-Barrett M, et al. ; IMAGEN Consortium . The structure of psychopathology in adolescence and its common personality and cognitive correlates. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125(8):1039-1052. doi: 10.1037/abn0000193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang-Pollock C, Shapiro Z, Galloway-Long H, Weigard A. Is poor working memory a transdiagnostic risk factor for psychopathology? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017;45(8):1477-1490. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0219-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caspi A, Moffitt TE All for one and one for all: mental disorders in one dimension. Am J Psychiatry. 2018:appiajp201817121383. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17121383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lahey BB, Zald DH, Perkins SF, et al. Measuring the hierarchical general factor model of psychopathology in young adults. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27(1):e1593. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, Cradock MM, Anand KJ. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288(6):728-737. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawk B, McCall RB. CBCL behavior problems of post-institutionalized international adoptees. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13(2):199-211. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0068-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124(1):111-126. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tottenham N, Hare TA, Quinn BT, et al. Prolonged institutional rearing is associated with atypically large amygdala volume and difficulties in emotion regulation. Dev Sci. 2010;13(1):46-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00852.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beauchaine TP, Zisner AR, Sauder CL. Trait impulsivity and the externalizing spectrum. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:343-368. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmad SI, Hinshaw SP. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, trait impulsivity, and externalizing behavior in a longitudinal sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017;45(6):1077-1089. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0226-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forbes MK, Rapee RM, Camberis AL, McMahon CA. Unique associations between childhood temperament characteristics and subsequent psychopathology symptom trajectories from childhood to early adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017;45(6):1221-1233. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0236-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martel MM. Dispositional trait types of ADHD in young children. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(1):43-52. doi: 10.1177/1087054712466915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeanah CH, Humphreys KL, Fox NA, Nelson CA. Alternatives for abandoned children: insights from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;15:182-188. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodhouse S, Miah A, Rutter M. A new look at the supposed risks of early institutional rearing. Psychol Med. 2018;48(1):1-10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blakemore SJ, Mills KL. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:187-207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of Institutionally-Reared Children

eTable 2. Demographic Characteristics of Children in the Current Study

eTable 3. Fit Information for One-, Two-, and Bifactor Models at Age 8, 12, and 16

eTable 4. Factor Loadings for the Bifactor Models at Age 8, 12, and 16

eFigure. Latent Growth Model for Correlated Factors Model

eTable 5. Growth Parameters for the Correlated-Factors Model With Internalizing and Externalizing Dimensions Only

eReferences.

Trial Protocol