Abstract

This cohort study assesses the association of bacteremic sepsis during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia with long-term neurocognitive dysfunction among children.

Although long-term survival in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) now exceeds 90%, survivors are at risk for treatment-related neurocognitive dysfunction that can persist into adulthood.1,2 We hypothesized that bacteremic sepsis during treatment for ALL contributes to long-term neurocognitive dysfunction and tested this hypothesis in a cohort study, using a propensity score–weighted model to adjust for potential confounders.3

Methods

In a prospective cohort study, survivors of pediatric ALL who had received risk-adapted chemotherapy from July 8, 2000, through November 25, 2010, without hematopoietic cell transplant or cranial irradiation underwent neurocognitive testing a median of 7.7 years after diagnosis of ALL (range, 5.1 to 12.5 years), with final follow-up completed on October 12, 2014.1,2 Episodes of bacteremia during treatment were retrospectively identified from institutional databases, and sepsis during each episode was categorized by review of medical records. Sepsis was defined as bacteremia plus urgent intervention for stabilization or severe sepsis according to consensus definitions.4,5 Because the participants were immunocompromised, systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria were not obligatory.4 This study was prospectively approved by the institutional review board of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee, and written consent was obtained from participants or their legally authorized representatives.

Each neurocognitive outcome variable, obtained from performance-based research testing, was expressed as an age-adjusted z score against population norms. Propensity for sepsis was estimated with a multinomial logistic regression model, including sex, self-reported race, age at diagnosis of ALL, leukemia risk category, and age at the time of testing. We estimated propensity score–adjusted z scores using generalized linear modeling, with age at diagnosis as a covariate and inverse propensity score weighting and calculated the difference between the mean values for participants with and without sepsis. Statistical tests were performed using SAS software for Windows (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc) with α set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 212 pediatric patients with ALL (104 girls [49.1%] and 108 boys [50.9%]; median age, 5.0 years [interquartile range, 3.2-8.8]) were enrolled. During ALL therapy, 16 participants (7.5%) had bacteremic sepsis, and 45 (21.2%) had bacteremia without sepsis. Baseline characteristics were similar for participants with a history of sepsis and the other participants; although those with a history of sepsis were older (median age, 7.8 years [IQR, 3.8-14.7 years] vs 4.9 years [IQR, 32-8.4 years]), the difference was not statistically significant (P = .07) (Table).

Table. Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Study Group | P Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis (n = 16) | No Sepsis | |||

| Bacteremia (n = 45) | No Bacteremia (n = 151) | |||

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 7.8 (3.8-14.7) | 3.8 (2.5-7.9) | 5.3 (3.4-8.9) | .07b |

| Time to evaluation, median (IQR), yc | 6.9 (6.2- 8.9) | 7.7 (6.6-9.4) | 7.3 (6.1-8.8) | .67b |

| Female, No. (%) | 8 (50.0) | 27 (60.0) | 69 (45.7) | >.99d |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| White | 13 (81.2) | 37 (82.2) | 123 (81.4) | .57e |

| Black or other | 3 (18.8) | 8 (17.8) | 28 (18.5) | |

| Final leukemia risk category, No. (%) | ||||

| Low | 10 (62.5) | 31 (68.9) | 81 (53.6) | .80d |

| Standard | 6 (37.5) | 14 (31.1) | 70 (46.4) | |

| Sepsis during treatment, No. (%) | ||||

| Severe sepsisf | 9 (56.2) | NA | NA | NA |

| Urgent interventiong | 7 (43.8) | NA | NA | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

Describes the difference between participants with sepsis (n = 16) and all others (n = 196).

Calculated using the Mann-Whitney test.

Indicates time to performance-based neurocognitive assessment since diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Calculated using the Fisher exact test.

Calculated using the χ2 test.

Defined by Goldstein et al.5

Defined by Wolf et al.4

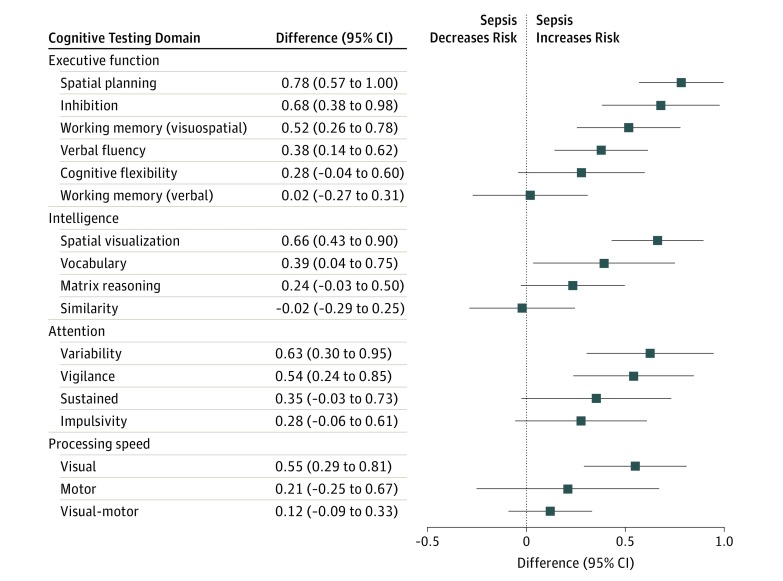

After adjustment for demographic and treatment-related confounders, including age, sex, race, and leukemia risk category, survivors with a history of sepsis performed worse than other participants in multiple neurocognitive domains, including executive function (spatial planning [difference, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.57-1.00], visuospatial working memory [difference, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.26-0.78], and verbal fluency [difference, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.14-0.62]) and attention (response time variability [difference, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.30-0.95], and vigilance [difference, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.24-0.85]) (Figure). Covariates, including sex, race, leukemia risk category, age at diagnosis, and age at testing, were well-balanced after adjustment. Unadjusted analyses showed similar results, and outcomes for participants who had bacteremia without sepsis were comparable to those of patients without bacteremia.

Figure. Differences in Mean Propensity Score–Adjusted Cognitive Testing Variables .

Differences are measured between participants who had experienced sepsis (n = 16) and all other participants (n = 196). Data points indicate differences; error bars, 95% CI.

Discussion

This study is, to our knowledge, the first publication to evaluate the association of sepsis during treatment for ALL with long-term neurocognitive function. Patients who had experienced bacteremic sepsis during therapy had significantly poorer neurocognitive function at long-term follow-up compared with other participants. Studies in other populations have suggested a similar association, but the mechanism remains controversial.3 In the population of children with cancer, these mechanisms might be augmented by increased blood-brain barrier permeability to neurotoxic chemotherapy drugs.3

The study has some limitations. Although outcome differences were observed for many measures, not all attained statistical significance because of the relatively small number of exposed study participants. A pragmatic sepsis definition enabled the identification of significant organ dysfunction, but the study-specific definition hampers interstudy comparisons.4 Last, because of potential confounding by unidentified variables, the gap between exposure and outcome assessment, and lack of information about baseline neurocognitive function, a causative association cannot be proven.

Conclusions

The finding that sepsis was associated with impaired long-term neurocognitive function has practice-changing implications for cancer survivorship. Prevention of infection, early recognition and appropriate management of sepsis, and preemptive neurocognitive interventions should be prioritized, because these might prevent or ameliorate neurologic damage.2,4,6 Future research could aim to validate this finding independently and evaluate mechanisms of brain injury.

References

- 1.Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, et al. . Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2730-2741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacola LM, Krull KR, Pui CH, et al. . Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive outcomes in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on a contemporary chemotherapy protocol. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(11):1239-1247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Widmann CN, Heneka MT. Long-term cerebral consequences of sepsis. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):630-636. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70017-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf J, Tang L, Flynn PM, et al. . Levofloxacin prophylaxis during induction therapy for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1790-1798. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A; International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis . International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(1):2-8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balamuth F, Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, et al. . Protocolized treatment is associated with decreased organ dysfunction in pediatric severe sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(9):817-822. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]