Key Points

Question

What are the national and state estimates of parent-reported, diagnosed traumatic brain injury in children aged 0 to 17 years?

Findings

In this analysis of data from the National Survey of Children’s Health, children were shown to have a lifetime estimate of a parent-reported traumatic brain injury diagnosis of 2.5%. National estimates of the association between traumatic brain injury and other childhood health conditions is reported along with parent report of insurance coverage and perception of insurance adequacy.

Meaning

A large number of children experience traumatic brain injury in the United States, and these children are more likely to have childhood health conditions; insurance type and parent adequacy perception contribute to care seeking and outcomes for children.

Abstract

Importance

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) in children results in a high number of emergency department visits and risk for long-term adverse effects.

Objectives

To estimate lifetime prevalence of TBI in a nationally representative sample of US children and describe the association between TBI and other childhood health conditions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data were analyzed from the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health, a cross-sectional telephone survey of US households with a response rate of 23%. Traumatic brain injury prevalence estimates were stratified by sociodemographic characteristics. The likelihood of reporting specific health conditions was compared between children with and without TBI. Age-adjusted prevalence estimates were computed for each state. Associations between TBI prevalence, insurance type, and parent rating of insurance adequacy were examined. Data analysis was conducted from February 1, 2016, through November 1, 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Lifetime estimate of TBI in children, associated childhood health conditions, and parent report of health insurance type and adequacy.

Results

The lifetime estimate of parent-reported TBI among children was 2.5% (95% CI, 2.3%-2.7%), representing over 1.8 million children nationally. Children with a lifetime history of TBI were more likely to have a variety of health conditions compared with those without a TBI history. Those with the highest prevalence included learning disorders (21.4%; 95% CI, 18.1%-25.2%); attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (20.5%; 95% CI, 17.4%-24.0%); speech/language problems (18.6%; 95% CI, 15.8%-21.7%); developmental delay (15.3%; 95% CI, 12.9%-18.1%); bone, joint, or muscle problems (14.2%; 95% CI, 11.6%-17.2%); and anxiety problems (13.2%; 95% CI, 11.0%-16.0%). States with a higher prevalence of childhood TBI were more likely to have a higher proportion of children with private health insurance and higher parent report of adequate insurance. Examples of states with higher prevalence of TBI and higher proportion of private insurance included Maine, Vermont, Pennsylvania, Washington, Montana, Wyoming North Dakota, South Dakota, and Colorado.

Conclusions and Relevance

A large number of US children have experienced a TBI during childhood. Higher TBI prevalence in states with greater levels of private insurance and insurance adequacy may suggest an underrecognition of TBI among children with less access to care. For more comprehensive monitoring, health care professionals should be aware of the increased risk of associated health conditions among children with TBI.

This population-based survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention examines the prevalence of traumatic brain injury in children throughout the United States.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) in children has a relatively high rate of emergency department (ED) visits1 and risk for long-term adverse effects,2,3,4,5 creating a large public health concern. Traumatic brain injury in children can alter cognitive, language, and behavioral development, which can affect learning at school,6 and has also been linked to other comorbid health conditions, such as neurologic disorders (eg, motor difficulties and epilepsy), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), mental disorders, and sleep disorders.7 These conditions can further affect social and emotional development. In 2013, there were approximately 640 000 TBI-related ED visits, 18 000 TBI-related hospitalizations, and 1500 TBI-related deaths among children aged 14 years and younger.1 Children aged 0 to 4 years had the highest rates of TBI-related ED visits of any age group except those older than 75 years.1 The leading causes of TBI-related ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths for individuals aged 0 to 14 years were unintentional falls and being struck by or against an object, whereas for those aged 15 to 24 years, the leading causes were motor vehicle crashes and falls.1 Another common cause of TBI is sports and recreational activity, which accounted for an estimated 325 000 TBI ED visits among children and adolescents in 2012.8

Mild TBI, a brief change in mental status or consciousness that is commonly called concussion,9 accounts for 70% to 90% of TBI ED visits.10,11 Children with mild TBI or concussions may seek care at clinical locations other than the ED or may not seek care, making it difficult to accurately estimate the true incidence, which is a critical factor for understanding the total public health outcome of TBI in children.10,12,13 More recent research examining point of entry for an initial visit for concussion care found that in a large, urban, pediatric health care system, 48.8% of children with TBI visited primary care; 27.2%, specialty care; and 20.2%, ED care.14 Because most pediatric TBIs are mild, only a fraction of children seen for emergency medical care for a TBI are hospitalized—a metric that has been used as an indicator of injury severity.15 In a cohort study reporting severity in children seeking emergency medical care from hospitals (N = 2940), 84.5% had mild TBI, 13.2% had moderate TBI, and 2.3% had severe TBI.16 Traumatic brain injury hospitalizations for children have decreased in recent years.1 Because most incidence reports of mild TBI are based on ED care, current estimates may be underestimating the outcome of pediatric TBI.

Traumatic brain injury in children has been linked to other childhood health conditions, including ADHD,17,18,19,20 seizures,21,22 behavior problems,23,24,25,26 mental disorders,27 learning problems,2,23,28 and hearing problems.29,30 Furthermore, children who have sustained a TBI tend to use speech and language services after their injury, indicating concerns about acquired cognitive and communication disorders.4,31 There are a number of health outcomes associated with TBI in children, supporting the need for more detailed estimates of conditions associated with TBI.

We currently have an understanding of the incidence of TBI from estimates of TBI-related ED visits and hospitalizations among children. However, these data do not allow for estimates of the number of children seen in other clinical settings or those who do not receive care and provide limited data on comorbid health conditions. The purpose of this study was to estimate both the national and state-specific prevalence of lifetime TBI based on parents’ report of a health care professional diagnosis of brain injury or concussion. Additional aims were to describe the association between TBI and other health conditions in this population and examine associations between state-level prevalence of TBI and state-level insurance coverage.

Methods

Participant Sample

Data were analyzed from the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health32 (NSCH), conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a module of the State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey, to determine a lifetime TBI history. Data analysis was conducted from February 1, 2016, through November 1, 2017. The NCHS Research Ethics Review Board and the institutional review board of NORC at the University of Chicago approved all study procedures and modifications. Participants provided verbal informed consent.

The NSCH is a cross-sectional telephone survey of US households using a random digit dial sample of landlines and cell phones designed to allow for both national and state estimates of children’s health.33 A parent or guardian answered questions in relation to 1 randomly selected child (N = 95 677) aged 0 through 17 years. The interview completion rate (the proportion of households who completed the interview among households known to include children) was 54.1% (landline) and 41.2% (cell phone). The overall response rate—including all nonresponses, such as households that were never successfully screened for the presence of children and telephone lines that rang with no answer—was 23.0%.

For these analyses, TBI was defined by a positive response to the question: “Has a doctor or other health care provider ever told you that [your child] had…a brain injury or concussion?” A help screen was provided for the interviewer that further defined a concussion and indicated that developmental conditions, such as autism, cerebral palsy, or brain tumors, should not be considered as brain injuries. Questions framed in a similar manner were asked for other health conditions, for example, ADHD, hearing problems, anxiety and behavioral or conduct problems, and epilepsy or a seizure disorder, to indicate a child’s lifetime history of the specific condition. The household respondent also reported sociodemographic characteristics including the child’s sex, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, household income (later categorized to reflect the federal poverty level), health insurance status (private, public, or uninsured), and highest educational level achieved by the parent/adult respondent living with the child. Within the survey, parents were asked questions related to whether their child had health insurance, the type of insurance, and their perception of the adequacy of their child’s current health insurance. Data are weighted to represent all noninstitutionalized children living in the United States.

Statistical Analysis

The weighted prevalence of a lifetime history of TBI was calculated by using SUDAAN’s crosstab procedure with 95% CIs derived from Taylor linearization. In addition, prevalence estimates were stratified by sociodemographic characteristics. Differences in TBI prevalence estimates by sociodemographic group were tested using the Wald F test. We also examined the trend in TBI prevalence by age using the stratum-adjusted Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel trend test (Wald χ2 = 257.2490, P < .001).

Crude TBI prevalence rate ratios were estimated by using logistic regression. To examine the association between TBI and specific health conditions, the prevalence of each health condition was calculated among children with and without TBI; prevalence rate ratios were adjusted by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and household income in logistic regression models. To reduce the outcome of different age distributions, age-adjusted lifetime TBI prevalence estimates were computed for each state. Logistic regression models were used to compute the odds ratios (ORs) for the associations between TBI prevalence by state with private health insurance type and with parent report of health care adequacy separately. In the logistic regression models, TBI prevalence rates were grouped hierarchically in 4 groups, and an individual’s private insurance type (private insurance type, 1/0) or report of adequate insurance (insurance adequate, 1/0) was modeled as an outcome variable as a function of state TBI prevalence (the lowest TBI category was used as the reference level).

The relative SE, a measure of an estimate’s statistical reliability (100 times SE of an estimate divided by the estimate), was calculated for each estimate and cell sizes reviewed. All relative SEs were less than 30%, and all sample sizes were greater than 20. SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc) and SAS-callable SUDAAN, version 11.0 (Research Triangle Institute) were used for statistical analysis. All analyses were performed by incorporating complex sample design features (including stratified sampling and weighting for unequal sample selection probabilities and nonresponse). Statistical significance of all 2-sided, unpaired P values was set at .05.

Results

Prevalence of TBI in Children

Among US children aged 0 to 17 years, the lifetime estimate of a parent-reported TBI diagnosis (ie, ever being told by a health care professional that the child had a brain injury or concussion) was 2.5% (95% CI, 2.3%-2.7%); this figure represents over 1.8 million US children (Table 1). Parent report of TBI in this survey was more common among children who were non-Hispanic white, boys, and those with private health insurance (Table 1). A trend test showed that TBI prevalence (percentage) increased with increasing age: 0 to 4 years (0.6%; 95% CI, 0.5%-1.0%), 5 to 11 years (1.7; 95% CI, 1.4%-2.0%), 12 to 14 years (3.9; 95% CI, 3.3%-4.5%), and 15 to 17 years (5.9; 95% CI, 5.3%-6.6%) (P < .01).

Table 1. Characteristics of Children With Parent Report of Brain Injury or Concussiona.

| Characteristic | No. of TBIs in Sample (Unweighted) | Estimated Population With TBI (Weighted) | TBI Prevalence (Weighted), % (95% CI) | Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (Weighted) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 2871 | 1 850 000 | 2.5 (2.3-2.7) | |

| Children | ||||

| Age, yb | ||||

| 0-4 | 195 | 128 000 | 0.6 (0.5-1.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| 5-11 | 703 | 490 000 | 1.7 (1.4-2.0) | 2.7 (1.8- 3.9) |

| 12-14 | 656 | 479 000 | 3.9 (3.3-4.5) | 6.1 (4.2- 8.7) |

| 15-17 | 1317 | 753 000 | 5.9 (5.3-6.6) | 9.2 (6.4-13.1) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1793 | 1 148 000 | 3.1 (2.8-3.4) | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) |

| Female | 1075 | 700 000 | 2.0 (1.7-2.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Missing/other | 3 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 225 | 266 000 | 1.6 (1.1-2.2) | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 2195 | 1 234 000 | 3.3 (3.0-3.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 119 | 134000 | 1.4 (1.0-2.0) | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) |

| Multiracial/other, non-Hispanic | 279 | 179 000 | 2.4 (1.9-3.1) | 0.5 (0.3-0.9) |

| Missing | 53 | |||

| Household | ||||

| Parent educational level | ||||

| <High school or high school | 1282 | 946 000 | 2.6 (2.3-3.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| >High school | 1472 | 825 000 | 2.6 (2.3-2.9) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

| Missing/DK/other | 117 | |||

| Family structure | ||||

| 2 Parent, biological or adopted | 1894 | 1 126 000 | 2.4 (2.1-2.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| 2 Parent, step family | 257 | 203 000 | 3.2 (2.5-4.1) | 1.4 (1.0-1.8) |

| Single mother, no father present | 507 | 365 000 | 2.7 (2.2-3.1) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) |

| Other | 192 | 141 000 | 2.9 (2.0-4.1) | 1.2 (0.9-1.8) |

| Household income, FPL %c | ||||

| <100 | 338 | 276 000 | 1.7 (1.3-2.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| 100-199 | 479 | 311 000 | 2.0 (1.6-2.4) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

| 200-399 | 870 | 575 000 | 2.8 (2.4-3.2) | 1.7 (1.3-2.2) |

| ≥400 | 1184 | 688 000 | 3.4 (3.0-3.8) | 2.1 (1.5-2.6) |

| Health insurancec | ||||

| Enrolled in health insuranced | 2774 | 1 783 000 | 2.6 (2.4-2.8) | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) |

| Lapse of insurancee | 92 | 65 000 | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 1 [Reference] |

| Missing/other | 5 | |||

| Insurance adequacy | ||||

| Yes | 1970 | 1 303 000 | 2.5 (2.2-2.7) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) |

| No | 901 | 546 000 | 2.6 (2.3-3.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| Type of insurancec | ||||

| Public (Medicaid/SCHIP) | 756 | 567 000 | 2.1 (1.8-2.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Private | 2007 | 1 210 000 | 2.9 (2.7-3.2) | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) |

| Uninsured/missing/other | 108 | |||

Abbreviations: DK, do not know; FPL, federal poverty level; SCHIP, State Children's Health Insurance Program; TBI, traumatic brain injury (parent report of diagnosed brain injury or concussion).

Data source: 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health.

TBI age trend test results obtained by using the stratum-adjusted Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel hypothesis test, Wald χ2 = 257.2490, P < .001.

Population prevalence estimates rounded to the nearest thousand.

Enrolled in any type of health insurance (private or public).

Lapse in health insurance reported at the time of interview.

TBI and Childhood Health Conditions

After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics of age, sex, parent educational level, and household income, children with a lifetime history of TBI were more likely to have received a parent-reported diagnosis of 13 of the 14 health conditions examined compared with children without a history of TBI (Table 2). For example, prevalence ratios ranged from 1.6 for ADHD to 7.3 for epilepsy or seizure disorder. Additional mental disorders (depression, anxiety problems, or behavioral and conduct problems), neurologic conditions (Tourette syndrome, epilepsy), chronic health conditions (hearing, vision), and intellectual disability were also significantly more likely to be reported by parents of children with a history of TBI. The conditions most commonly reported among children with a history of TBI were learning disorders (21%), ADHD (20%), speech and language problems (19%), developmental delay (15%), and bone, joint, or muscle problems (14%). Although learning disorders, ADHD, and speech and language problems were also the conditions most commonly reported by parents of children without a history of TBI, their prevalence was lower than in the TBI group.

Table 2. Prevalence of Parent-Reported Health Conditions Among Children With and Without a Parent-Reported, Diagnosed Brain Injury or Concussiona.

| Health Condition | Presence of Specific Health Condition, Prevalence (95% CI) | Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TBI | No TBI | ||

| Epilepsy or seizure disorder | 7.9 (5.8-10.7) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 7.3 (5.0-10.5) |

| Intellectual disability | 5.9 (4.5-7.7) | 1.0 (0.8-1.1) | 5.1 (3.7-7.0) |

| Bone, joint, or muscle problem | 14.2 (11.6-17.2) | 2.8 (2.6-3.1) | 3.7 (3.0-4.7) |

| Vision problem | 6.7 (4.8-9.4) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 3.6 (2.5-5.1) |

| Developmental delay | 15.3 (12.9-18.1) | 4.9 (4.6-5.2) | 2.9 (2.4-3.4) |

| Speech/language problem | 18.6 (15.8-21.7) | 7.9 (7.5-8.3) | 2.2 (1.7-2.6) |

| Tourette syndrome | 0.8 (0.4-1.7) | 0.2 (0.1-0.2) | 2.2 (1.0-4.6) |

| Behavioral or conduct problems | 9.3 (7.0-12.1) | 3.5 (3.3-3.8) | 2.1 (1.5-2.8) |

| Depression | 10.9 (8.7-13.5) | 3.2 (2.9-3.5) | 2.1 (1.7-2.7) |

| Anxiety problem | 13.2 (11.0-16.0) | 4.3 (4.1-4.6) | 2.0 (1.6-2.4) |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 5.1 (3.7-6.9) | 2.0 (1.8-2.2) | 1.9 (1.4-2.8) |

| Learning disorder | 21.4 (18.1-25.2) | 8.6 (8.2-9.0) | 1.9 (1.6-2.3) |

| ADHD | 20.5 (17.4-24.0) | 8.5 (8.1-8.9) | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) |

| Diabetes | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 0.4 (0.3-0.5) | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; TBI, traumatic brain injury (parent report of diagnosed brain injury or concussion).

Data source: 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health.

Prevalence of specific condition among children with vs without brain injury, adjusted by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and household income.

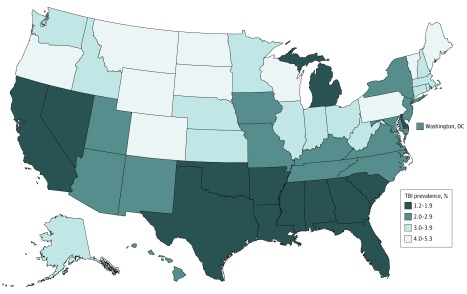

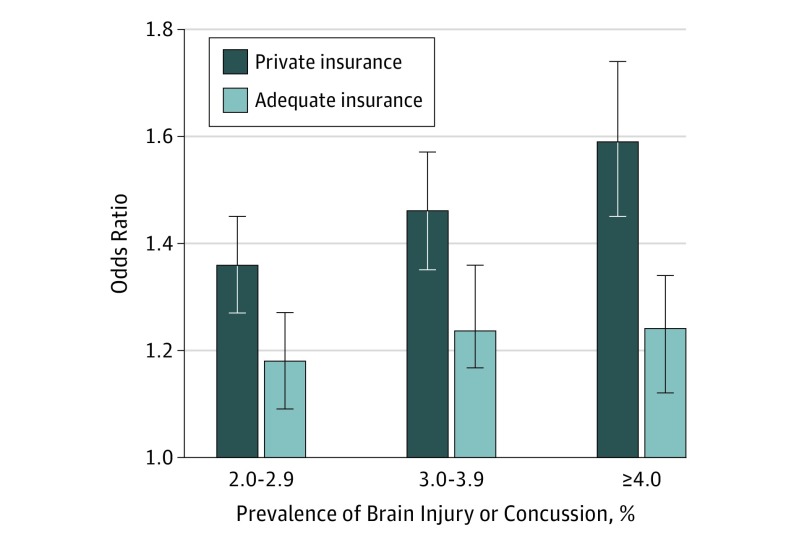

Lifetime History of TBI by State

State estimates of parent-reported TBI ranged from an age-adjusted prevalence of 1.20% in Mississippi to 5.30% in Maine (Table 3, Figure 1). In examining health insurance type, states with a higher prevalence of childhood TBI were more likely to also have higher estimates of private health insurance compared with public health insurance (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.27-1.46). Examples of states with higher proportions of private insurance include Maine, Vermont, Pennsylvania, Washington, Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Colorado, and Michigan. States with a higher prevalence of childhood TBI also had higher estimates of parent-reported adequate insurance compared with those reporting less-adequate insurance (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.16-1.36) (Figure 2).

Table 3. Age-Adjusted Prevalence of Parent-Reported, Diagnosed Brain Injury or Concussion (TBI) Among Children by Statea.

| State | No. of TBIs in Sample (Unweighted) | Estimated Population With TBI (Weighted) | Age-Adjusted Prevalence (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2871 | 1 849 989 | 2.51 (2.32-2.72) |

| Alabama | 47 | 19 500 | 1.72 (1.15-2.57) |

| Alaska | 51 | 5600 | 3.14 (2.14-4.60) |

| Arizona | 53 | 40 574 | 2.50 (1.67-3.75) |

| Arkansas | 41 | 12 178 | 1.73 (1.09-2.72) |

| California | 36 | 176 924 | 1.91 (1.17-3.10) |

| Colorado | 84 | 50 731 | 4.26 (3.15-5.73) |

| Connecticut | 76 | 25 663 | 3.01 (2.28-3.96) |

| Delaware | 41 | 3482 | 1.74 (1.13-2.69) |

| District of Columbia | 41 | 2692 | 2.77 (1.66-4.60) |

| Florida | 35 | 55 233 | 1.38 (0.82-2.34) |

| Georgia | 39 | 42 534 | 1.78 (1.16-2.71) |

| Hawaii | 40 | 7463 | 2.47 (1.62-3.74) |

| Idaho | 71 | 12 509 | 3.00 (2.06-4.34) |

| Illinois | 62 | 99 952 | 3.21 (2.31-4.46) |

| Indiana | 67 | 58 732 | 3.72 (2.64-5.22) |

| Iowa | 52 | 17 422 | 2.40 (1.70-3.37) |

| Kansas | 65 | 25 606 | 3.64 (2.57-5.14) |

| Kentucky | 46 | 27 884 | 2.76 (1.93-3.93) |

| Louisiana | 30 | 14 587 | 1.31 (0.74-2.29) |

| Maine | 90 | 14 450 | 5.30 (4.06-6.88) |

| Maryland | 56 | 30 308 | 2.24 (1.54-3.27) |

| Massachusetts | 67 | 51 217 | 3.53 (2.64-4.71) |

| Michigan | 35 | 32 598 | 1.37 (0.84-2.22) |

| Minnesota | 67 | 41 081 | 3.32 (2.39-4.59) |

| Mississippi | 33 | 9006 | 1.20 (0.69-2.07) |

| Missouri | 58 | 38 007 | 2.66 (1.91-3.70) |

| Montana | 80 | 9131 | 4.29 (3.16-5.79) |

| Nebraska | 59 | 16 592 | 3.78 (2.74-5.20) |

| Nevada | 43 | 10 695 | 1.68 (1.03-2.73) |

| New Hampshire | 70 | 10 918 | 3.57 (2.66-4.78) |

| New Jersey | 48 | 56 919 | 2.69 (1.83-3.93) |

| New Mexico | 49 | 10 957 | 2.17 (1.40-3.37) |

| New York | 48 | 103 776 | 2.40 (1.67-3.42) |

| North Carolina | 55 | 52 386 | 2.33 (1.62-3.34) |

| North Dakota | 64 | 5769 | 3.98 (2.84-5.56) |

| Ohio | 63 | 96 961 | 3.52 (2.43-5.07) |

| Oklahoma | 48 | 16 788 | 1.84 (1.27-2.66) |

| Oregon | 71 | 35 148 | 4.16 (3.08-5.60) |

| Pennsylvania | 86 | 142 760 | 5.01 (3.66-6.82) |

| Rhode Island | 64 | 7686 | 3.42 (2.41-4.82) |

| South Carolina | 34 | 16 825 | 1.57 (0.98-2.50) |

| South Dakota | 61 | 8333 | 4.30 (3.13-5.88) |

| Tennessee | 46 | 37 845 | 2.53 (1.69-3.77) |

| Texas | 35 | 92 715 | 1.38 (0.77-2.47) |

| Utah | 64 | 21 943 | 2.66 (1.92-3.68) |

| Vermont | 89 | 5940 | 4.41 (3.35-5.77) |

| Virginia | 41 | 37 444 | 2.00 (1.28-3.10) |

| Washington | 77 | 52 123 | 3.38 (2.41-4.71) |

| West Virginia | 50 | 12 131 | 3.15 (2.21-4.45) |

| Wisconsin | 69 | 66 652 | 5.03 (3.67-6.87) |

| Wyoming | 74 | 5598 | 4.20 (3.08-5.69) |

Data source: 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health.

Figure 1. Age-Adjusted Prevalence of Parent-Reported, Diagnosed Brain Injury or Concussion Among Children, by State.

TBI indicates parent report of diagnosed traumatic brain injury or concussion.

Figure 2. Association of Private Insurance and Parent Report of Insurance Adequacy With State-Level Prevalence Estimates of Parent-Reported, Diagnosed Brain Injury or Concussion by Prevalence Group.

Parent report of diagnosed traumatic brain injury or concussion; 1.2%-1.9% was established as a reference group, with an odds ratio of 1.0.

Discussion

Based on parent report of a health care professional’s diagnosis among a nationally representative sample in 2011-2012, 2.5% of US children aged 0 to 17 years have experienced a TBI in their lifetime. To our knowledge, this is the first lifetime estimate across the developmental age span for children. Previous national estimates were based on ED visit rates or a report of visit location for concussion in a large pediatric health care system.14 In 2013, children aged 0 to 4 years (1591 per 100 000 population) had the highest rate of pediatric ED visits followed by children in the age 15- to 24-year population (1080.7 per 100 000 population).1

The estimate provided by this study does not capture children who did not receive medical care for their injury, so it is likely an underestimate of childhood TBI in the United States. In addition, the type of clinician and the location of the health care visit where the TBI was diagnosed was not included as part of the survey. Consequently, this study cannot provide information on where parents sought treatment for a TBI sustained by their children.

Findings from this nationally representative sample indicate a higher occurrence of other health and developmental conditions in children who experienced a lifetime TBI, including learning disorders, ADHD, speech and language problems, developmental delay, anxiety, depression, and behavior problems. Although many of these findings align with previous research reporting on the association of TBI with other childhood health conditions,3,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,34 to our knowledge, this is the first report to examine associations in a national sample and include speech and language conditions and developmental delay. Previous reports have provided prevalence data on these specific conditions but have not considered an association with TBI. The presence of these conditions may be a compounding factor affecting the likelihood of experiencing cognitive, social, and health challenges following TBI. However, due to the cross-sectional nature of the NSCH, we cannot distinguish whether the conditions occurred before or after the TBI and therefore cannot determine whether these conditions contributed to or were a consequence of the TBI. Knowing the association of other childhood health conditions with TBI suggests that health care professionals should inquire about TBI history at the time of diagnosis of childhood health conditions and ask parents about a child’s total health history at the time of TBI diagnosis. Understanding a more comprehensive picture of a child’s health status at the time of TBI diagnosis facilitates optimal management to improve recovery and outcomes.

The map (Figure 1) illustrates differences in state estimates of the age-adjusted prevalence of parent-reported TBI diagnosed by a health care professional. Estimates of uninsured populations in 2011-2012 were previously reported by region rather than state, with higher estimates in the South (18.6%) and West (17.0%) compared with the Northeast (10.8%) and Midwest (11.9%).35 Recent research indicates that insurance status among children with TBI is associated with better health outcomes. Children with TBI who had private health insurance had lower mortality rates and better quality of care following TBI than those with public insurance or those who were uninsured,36 suggesting an association between insurance type and health care quality for children with TBI. In this study, individuals in states with higher levels of TBI were more likely to report private insurance and adequate insurance coverage, suggesting that insurance coverage may explain some of the differences in lifetime TBI estimates found between states.

Some studies of pediatric TBI report high rates of private insurance,14 suggesting that coverage by this insurance type may support seeking care at the time of the TBI. Also, parents who believe that they have adequate insurance may be willing to seek care. However, further investigation is needed to determine additional factors related to seeking care for TBI in children, including parents’ views on the need for a medical assessment of TBI.

Limitations

This study has limitations. The NSCH relies on parent report of health care professionals’ diagnosed brain injury or concussion, other health conditions and insurance, and does not examine medical records. Health care professionals’ diagnoses were inferred by parents’ response to survey questions; however, these estimates may have been affected by difficulties in recall as well as any challenges related to communication of the diagnosis between the health care professional and the parent/guardian. This survey did not capture those who experienced a TBI but did not seek a medical assessment by a health care professional. In addition, other types of acquired brain trauma, such as anoxic brain injuries (ie, due to lack of oxygen), may have been included in affirmative responses provided by respondents resulting from question wording (ie, a brain injury or concussion). The response rate for this survey was low, increasing the likelihood that the results were influenced by factors associated with the decision to participate. However, the data were weighted to adjust for nonresponse in an effort to account for differences between the sample and population.

The brain injury question includes help text informing parents not to consider developmental conditions, such as cerebral palsy and autism; however, it is possible that some parents missed that instruction and incorrectly included those conditions as brain injuries. To the extent that this misunderstanding occurred, it would increase the report of brain injuries and contribute to the observed association between autism and brain injury. Directionality between TBI and associated health conditions cannot be inferred owing to the cross-sectional nature of the study. Parent report of health insurance indicated current status, so it is possible that one’s insurance status was different at the time of the injury.

Conclusions

Children of all backgrounds may be affected by TBI in their lifetime, highlighting the importance of inquiring about a history of TBI during well-child health care visits. The combination of TBI and the health conditions associated with a TBI can have a significant outcome on a child’s overall health, learning, and behavior. Although it is unclear whether the conditions existed prior to or are a consequence of the TBI injury, improved care for children can be better achieved if pediatric health care professionals offer medical guidance to parents in the context of a child’s overall health history, including history of lifetime TBI. For children with diagnosed TBI, health care professionals can assess for conditions identified in this analysis. To produce more comprehensive estimates of TBI in children, nonmedical data sources will need to be expanded to capture children who do not or cannot seek treatment. A proposed system, the National Concussion Surveillance System, holds the potential for obtaining more comprehensive prevalence estimates of TBI in children.37

References

- 1.Taylor CA, Bell JM, Breiding MJ, Xu L. Traumatic brain injury–related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths—United States, 2007 and 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(9):1-16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6609a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson VA, Catroppa C, Dudgeon P, Morse SA, Haritou F, Rosenfeld JV. Understanding predictors of functional recovery and outcome 30 months following early childhood head injury. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(1):42-57. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.1.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ewing-Cobbs L, Prasad MR, Kramer L, et al. Late intellectual and academic outcomes following traumatic brain injury sustained during early childhood. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(4)(suppl):287-296. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.105.4.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivara FP, Koepsell TD, Wang J, et al. Incidence of disability among children 12 months after traumatic brain injury. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):2074-2079. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeates KO, Swift E, Taylor HG, et al. Short- and long-term social outcomes following pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(3):412-426. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704103093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haarbauer-Krupa J, Ciccia A, Dodd J, et al. Service delivery in the healthcare and educational systems for children following traumatic brain injury: gaps in care. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017;32(6):367-377. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babikian T, Merkley T, Savage RC, Giza CC, Levin H. Chronic aspects of pediatric traumatic brain injury: review of the literature. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(23):1849-1860. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.3971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coronado VG, Haileyesus T, Cheng TA, et al. Trends in sports- and recreation-related traumatic brain injuries treated in US emergency departments: the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP) 2001-2012. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30(3):185-197. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Traumatic brain injury and concussion, TBI: get the facts. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/get_the_facts.html. Updated April 27, 2017. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- 10.Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Peloso PM, et al. ; WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury . Incidence, risk factors and prevention of mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Rehabil Med. 2004;(43)(suppl):28-60. doi: 10.1080/16501960410023732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faul M, Xu L, Wald M, Coronado V Traumatic brain injury in the United States: emergency department visits, hospitalizations and deaths 2002-2006. http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/blue_book.pdf. Published March 2010. Accessed September 15, 2012.

- 12.Kirkwood MW, Yeates KO, Taylor HG, Randolph C, McCrea M, Anderson VA. Management of pediatric mild traumatic brain injury: a neuropsychological review from injury through recovery. Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;22(5):769-800. doi: 10.1080/13854040701543700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schootman M, Fuortes LJ. Ambulatory care for traumatic brain injuries in the US, 1995-1997. Brain Inj. 2000;14(4):373-381. doi: 10.1080/026990500120664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arbogast KB, Curry AE, Pfeiffer MR, et al. Point of health care entry for youth with concussion within a large pediatric care network. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(7):e160294. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneier AJ, Shields BJ, Hostetler SG, Xiang H, Smith GA. Incidence of pediatric traumatic brain injury and associated hospital resource utilization in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):483-492. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivara FP, Koepsell TD, Wang J, et al. Disability 3, 12, and 24 months after traumatic brain injury among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1129-e1138. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bloom DR, Levin HS, Ewing-Cobbs L, et al. Lifetime and novel psychiatric disorders after pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(5):572-579. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200105000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iverson GL, Atkins JE, Zafonte R, Berkner PD. Concussion history in adolescent athletes with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33(23):2077-2080. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keenan HT, Hall GC, Marshall SW. Early head injury and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a1984. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKinlay A, Grace RC, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM, Ridder EM, MacFarlane MR. Prevalence of traumatic brain injury among children, adolescents and young adults: prospective evidence from a birth cohort. Brain Inj. 2008;22(2):175-181. doi: 10.1080/02699050801888824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen G, Joffe AR, Bowman SM, Richer L. Nonconvulsive seizures and status epilepticus in pediatric head trauma: a national survey. [published online February 27, 2015]. SAGE Open Med. 2015;3:2050312115573817. doi: 10.1177/2050312115573817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaaramo K, Puljula J, Tetri S, Juvela S, Hillbom M. Predictors of new-onset seizures: a 10-year follow-up of head trauma subjects with and without traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(6):598-602. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawley CA, Ward AB, Magnay AR, Long J. Parental stress and burden following traumatic brain injury amongst children and adolescents. Brain Inj. 2003;17(1):1-23. doi: 10.1080/0269905021000010096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karver CL, Wade SL, Cassedy A, et al. Age at injury and long-term behavior problems after traumatic brain injury in young children. Rehabil Psychol. 2012;57(3):256-265. doi: 10.1037/a0029522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor HG, Orchinik LJ, Minich N, et al. Symptoms of persistent behavior problems in children with mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30(5):302-310. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ylvisaker M, Feeney T. Pediatric brain injury: social, behavioral, and communication disability. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18(1):133-144, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Max JE, Friedman K, Wilde EA, et al. Psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents 24 months after mild traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;27(2):112-120. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13080190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glang A, Todis B, Thomas CW, Hood D, Bedell G, Cockrell J. Return to school following childhood TBI: who gets services? NeuroRehabilitation. 2008;23(6):477-486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schell A, Kitsko D. Audiometric outcomes in pediatric temporal bone trauma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154(1):175-180. doi: 10.1177/0194599815609114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waissbluth S, Ywakim R, Al Qassabi B, et al. Pediatric temporal bone fractures: a case series. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;84:106-109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slomine BS, McCarthy ML, Ding R, et al. ; CHAT Study Group . Health care utilization and needs after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):e663-e674. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health frequently asked questions. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm. April 2013. Accessed November 12, 2015.

- 33.Bramlett MD, Blumberg SJ, Zablotsky B, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children’s Health, 2011-2012. Vital Health Stat 1. 2017;(59):1-256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Identified attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and medically attended, nonfatal injuries: US school-age children, 1997-2002. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(1):38-44. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith J US Census Bureau, current population reports, P60-245: income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2012. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fabio A, Murray A, Mellers M, Wisniewski S, Bell M. The effects of insurance status on pediatric traumatic brain injury outcomes: a literature review. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2017;10(2):107-120. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Traumatic brain injury & concussion. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/ncss/index.html. Updated March 30, 2017. Accessed September 5, 2017.