Key Points

Question

What are the high-priority clinical questions and patient-important outcomes associated with the treatment of age-related macular degeneration?

Findings

In this cross-sectional survey of 124 health care professionals and 46 patients with age-related macular degeneration, respondents named the high-priority clinical questions associated with treatment of age-related macular degeneration; respondents, professionals, and patients agreed on 12 questions, and patients with age-related macular degeneration identified 6 highly important outcomes balanced between intended effects of treatment (eg, slowing vision loss) and adverse events (eg, retinal hemorrhage).

Meaning

The results from this cross-sectional survey may inform future age-related macular degeneration research and clinical care.

Abstract

Importance

Identifying and prioritizing unanswered clinical questions may help to best allocate limited resources for research associated with the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Objective

To identify and prioritize clinical questions and outcomes for research associated with the treatment of AMD through engagement with professional and patient stakeholders.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Multiple cross-sectional survey questions were used in a modified Delphi process for panel members of US and international organizations, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) Retina/Vitreous Panel (n=7), health care professionals from the American Society of Retinal Specialists (ASRS) (n=90), Atlantic Coast Retina Conference (ACRC) and Macula 2017 meeting (n=34); and patients from MD (Macular Degeneration) Support (n=46). Data were collected from January 20, 2015, to January 9, 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The prioritizing of clinical questions and patient-important outcomes for AMD.

Results

Seventy clinical questions were derived from the AAO Preferred Practice Patterns for AMD and suggestions by the AAO Retina/Vitreous Panel. The AAO Retina/Vitreous Panel assessed all 70 clinical questions and rated 17 of 70 questions (24%) as highly important. Health care professionals assessed the 17 highly important clinical questions and rated 12 of 17 questions (71%) as high priority for research to answer; 9 of 12 high-priority clinical questions were associated with aspects of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor agents. Patients assessed the 17 highly important clinical questions and rated all as high priority. Additionally, patients identified 6 of 33 outcomes (18%) as most important to them (choroidal neovascularization, development of advanced AMD, retinal hemorrhage, gain of vision, slowing vision loss, and serious ocular events).

Conclusions and Relevance

Input from 4 stakeholder groups suggests good agreement on which 12 priority clinical questions can be used to underpin research related to the treatment of AMD. The 6 most important outcomes identified by patients were balanced between intended effects of AMD treatment (eg, slowing vision loss) and adverse events. Consideration of these patient-important outcomes may help to guide clinical care and future areas of research.

This study identifies clinical questions and patient-important outcomes prioritized using a modified Delphi process and associated with age-related macular degeneration, as well as their implications for future research and clinical care.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of uncorrectable vision loss in adults 50 years and older in the United States.1 Vision loss due to AMD, which ultimately affects central vision, is associated with poor quality of life and a decreased sense of independence in affected individuals.2 Similar to clinical measures, outcomes that have been named as important by patients should be validated through research.3 Patient perspective, clinical expertise, and scientific evidence form the triad of evidence-based medicine; thus these viewpoints should be considered together when setting a research agenda and determining outcomes to be examined in research.4

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews of RCTs are considered to provide the highest level of evidence to determine the effectiveness of clinical interventions.5 Resources are insufficient to conduct RCTs and systematic reviews on all possible research questions.6 Thus, establishing a framework for identifying important unanswered clinical questions would help funders and researchers to prioritize trials and systematic reviews to be conducted.

The overall objective of this study was to identify and prioritize clinical questions and patient-important outcomes associated with the treatment of AMD by adapting a priority-setting framework used for other eye conditions.7,8,9,10,11 The process begins by identifying treatment recommendations from clinical practice guidelines and translating each treatment recommendation into an answerable clinical question. In a previous study,12 evidence gaps were identified by assessing the evidence cited to support each treatment recommendation and mapping the clinical questions to existing reliable systematic reviews for treatment recommendations extracted from the 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) Preferred Practice Pattern (PPP) for the management of AMD.13 In this study, multiple stakeholders, including clinical practice guideline developers, health care professionals, and patients, prioritized the importance of research to answer each clinical question in light of the available evidence.

Methods

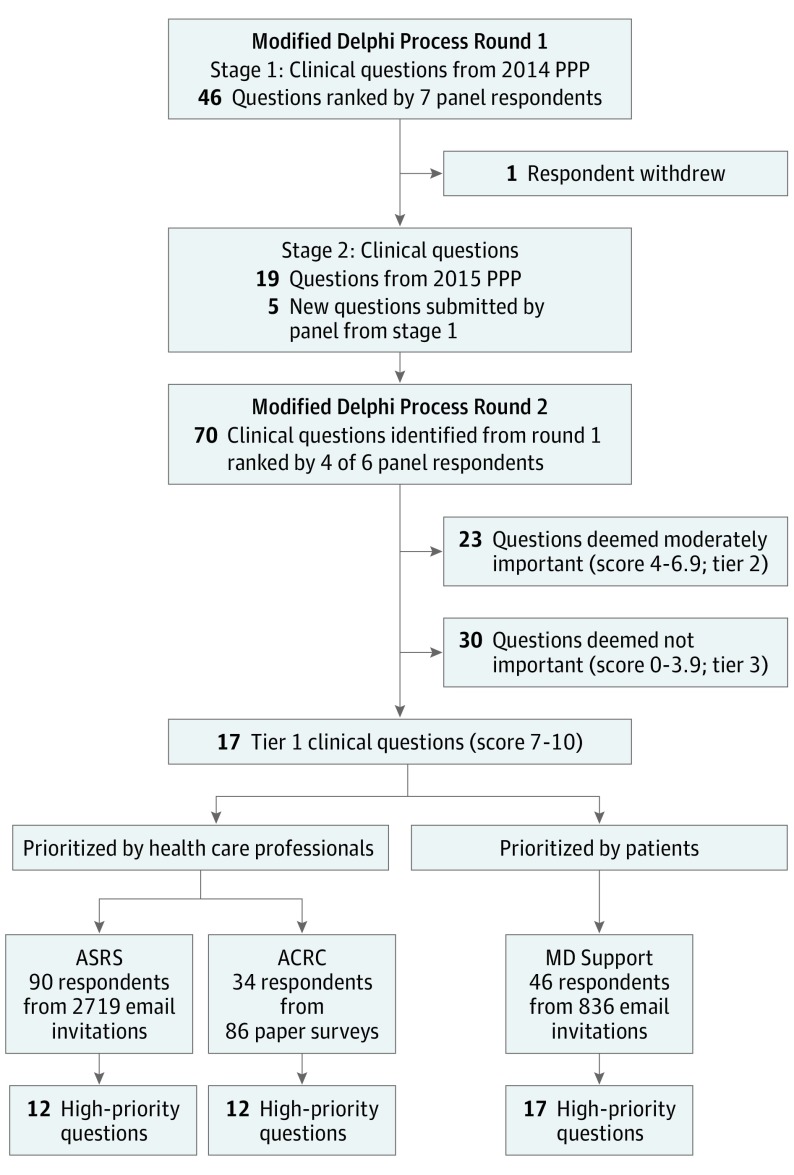

This study used a modified Delphi process to identify and prioritize clinical research questions and patient-important outcomes associated with the treatment of AMD in 4 steps: (1) derive clinical questions from clinical practice guidelines and specialists in AMD; (2) survey clinical practice guideline developers to identify the most important clinical questions for research to answer; (3) survey retina experts and health care professionals to prioritize the order in which the most important clinical questions should be addressed by research; and (4) survey patients to prioritize the most important clinical questions and outcomes from their perspective (Figure).

Figure. Flowchart for Identification and Prioritization of Clinical Questions.

ACRC indicates Atlantic Coast Retina Conference; ASRS, American Society of Retinal Specialists; MD, macular degeneration; and PPP, preferred pratice pattern.

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board, Baltimore, Maryland. Per direction from the institutional review board, the survey included the statement that completing the survey was also providing informed consent. We did not collect identifiable data from any survey participant and all responses remain anonymous. eAppendix 1 in the Supplement includes protocol and amendments.

Step 1: Derive Clinical Questions From Clinical Practice Guidelines and Specialists in AMD

We identified treatment recommendations in the 2014 and 2015 AAO clinical practice guidelines, known as Preferred Practice Pattern (PPP), for management of AMD.13,14 Two individuals (B.S.H. and K.B.L. for 2014 PPP and K.B.L. and S.H. for 2015 PPP) independently reviewed and extracted every statement that could be considered a treatment recommendation published in the PPP guideline. We formulated each recommendation into an answerable clinical question using the PICO (participant, intervention, comparison, and outcome) format. We consulted with AMD specialists (1 member of ACRC and Macula 2017, Neil M. Bressler, MD, and 1 of us, T.W.O.) who had expertise both in the management of AMD and in forming answerable clinical questions to confirm that our restatements were accurate and adding other clinical questions that were not addressed directly in the PPP guideline.

Step 2: Identify Highly Important Clinical Questions

We conducted a 2-round, web-based, cross-sectional, modified Delphi consensus survey.15 We asked each panel member to assign a rating to each clinical question derived from the PPP on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 indicating highly important and 0 indicating not important at all. Panel members also had an option to assign a score of “no judgment.” At each round, panel members could enter comments and suggest new clinical questions.

We administered the first round of the survey in 2 stages because the AAO PPP published an update during the first survey period (January 2015). From January to February 2015, the 7-member panel rated 46 clinical questions derived from the 2014 AAO PPP on the management of AMD. We used Survey Monkey (http://www.surveymonkey.com) in the first part of round 1; we used Qualtrics (http://www.qualtrics.com) for all subsequent online surveys. One panel member withdrew from the panel between the first and second part of round 1 and was not replaced. In the second part of round 1 (March 2016), the 6-member panel rated 24 additional clinical questions as a continuation of the first round of the survey, 19 derived from the 2015 AAO PPP and 5 contributed by the panel members in the first stage. In the 2 parts of round 1, panel members prioritized a total of 70 clinical questions.

In round 2 of the survey, conducted from June through August 2016, we provided the 6 panel members the median score for each clinical question from the first round of the survey. We asked them to rate the 70 clinical questions again, taking into account the median scores from the first round.

After the second round was completed, we grouped clinical questions into 3 prespecified tiers based on the median scores after the second round (tier 1, median score of 7-10; tier 2, median score of 4-6.9, and tier 3, median score of 0 to 3.9). We considered tier 1 questions to represent highly important clinical research questions. The rationale for asking the panel to identify the most important clinical questions was to reduce the number of clinical questions so that the prioritization surveys could be completed in 15 minutes or less.

Step 3: Prioritize Clinical Questions by Health Care Professionals

To prioritize the tier 1 clinical questions, we surveyed members of the American Society of Retinal Specialists (ASRS) and attendees of the Atlantic Coast Retina Conference (ACRC) and Macula 2017 meetings. Survey participants rated each tier 1 clinical question on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 indicating the highest priority and 0 indicating not a priority at all (eAppendix 3 in the Supplement). Survey participants also had an option to assign a score of “no judgment” and to submit additional clinical questions important to them. Additionally, we asked survey participants to provide demographic and professional information.

In partnership with ASRS, the survey was announced and first made available at the ASRS exhibitor booth on Retina Subspecialty Day at the AAO Annual Meeting in Chicago, Illinois, on October 14, 2016. The survey was available online via ASRS listserv until December 19, 2016; invitations and reminders to complete the survey were sent to the membership via ASRS’s Retina FYI monthly e-newsletter (October, November, and December 2016). The ASRS listserv included 2719 email addresses.

We surveyed attendees of the ACRC and Macula 2017 meeting, held January 5-7, 2017, in Baltimore, Maryland. The survey, administered on paper, included the same questions as those posed to ASRS, with an additional question that asked whether the participant had completed the online survey. We distributed 86 surveys to attendees from the registration table. We collected completed surveys through January 9, 2017.

Step 4: Prioritize Clinical Questions and Outcomes by Patients

The online MD (Macular Degeneration) Support is a nonprofit organization established to educate and support individuals affected by macular degeneration. Survey participants rated each tier 1 clinical question on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 indicating the highest priority and 0 indicating not a priority at all. In addition to rating the tier 1 clinical questions, survey participants ranked the importance of outcomes related to the management of AMD using 4 categories: most important, moderately important, least important, and unsure (no judgment). We identified the outcomes to be ranked based on common AMD-related outcomes assessed in published RCTs and systematic reviews.16,17 We considered outcomes ranked as “most important” by 70% or more respondents as highly important and those scored as “most important” by 15% or fewer respondents as not highly important.18 We asked participants to record any clinical questions or outcomes of importance to them that were not included in the survey. We also asked broad, nonidentifying questions about the respondents’ AMD status, such as stage of AMD.

The patient survey was available online from October 13, 2016, until December 19, 2016. The MD Support online forum consists of 385 listserv members and 451 people registered for automatic notices on the website. An unknown number of people are registered to both lists; thus, we considered the forum to include a maximum of 836 unique email addresses.

We calculated the median and interquartile range for each clinical question from each prioritization survey. We considered clinical questions with a median score of 7 or higher to represent high-priority clinical questions for research to answer. We compared scores by cohort of stakeholders (ie, ASRS, ACRC and Macula 2017, and MD Support). Data were collected from January 20, 2015, to January 9, 2017.

Results

In total, we identified 70 clinical questions associated with the management of AMD (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). Of the 70 clinical questions, 17 involved anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents; 13 photodynamic therapy; 8 laser photocoagulation; 8 antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements; and 24 were related to other treatment modalities.

The AAO Retina/Vitreous Panel rated 17 of 70 clinical questions (24%) as tier 1 (ie, highly important) (Figure; eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). No clinical question changed tiers between round 1 and round 2 of the survey. Nine of the 17 tier 1 clinical questions (53%) related to anti-VEGF agents, 4 to antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements (24%), and 1 each to photodynamic therapy, smoking cessation, self-monitoring, and surgery for cataract in eyes with AMD (Table 1). Six of the 7 panel members reported no conflicts of interest.

Table 1. Prioritization of 17 Highly Important Clinical Questions Associated With the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD).

| Clinical Questions Scored as Highly Important by the AAO Retina/Vitreous Panel | ASRS | ACRC and Macula 2017 | MD Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are intravitreous injections of anti-VEGF agents effective treatments for neovascular AMD? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Is aflibercept effective for the treatment of AMD? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Is aflibercept safe for the treatment of AMD? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Is bevacizumab effective for the treatment of AMD? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Is bevacizumab safe for the treatment of AMD? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Is ranibizumab effective for the treatment of AMD? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Is ranibizumab safe for the treatment of AMD? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Are intravitreous injections of anti-VEGF agents effective as a primary treatment for AMD with juxtafoveal lesions? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Are anti-VEGF agents safe to inject during pregnancy? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Are antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements an effective treatment for intermediate AMD? | Not high priority | High priority | High priority |

| Are antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements an effective treatment for advanced AMD in only 1 eye? | Not high priority | Not high priority | High priority |

| Is long-term supplementation with high-dose antioxidants safe for the general patient with AMD? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Is long-term supplementation with high-dose antioxidants safe for smokers with AMD? | Not high priority | Not high priority | High priority |

| Does smoking cessation prevent progression of AMD? | High priority | Not high priority | High priority |

| Is self-monitoring by patients at high-risk effective in preventing progression of advanced AMD? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

| Does avoiding sunlight after verteporfin photodynamic therapy prevent or reduce photosensitivity reactions? | Not high priority | Not high priority | High priority |

| Is surgery for cataracts in people with AMD safe? | High priority | High priority | High priority |

Abbreviations: AAO, American Academy of Ophthalmology; ACRC, Atlantic Coast Retina Conference; ASRS, American Society of Retina Specialists; MD, macular degeneration; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

From invitations sent to 2719 email addresses in the ASRS listserv, 106 ASRS members (4%) accessed the online prioritization survey and 90 of 106 members (85%) participated in the survey. Health care professionals assessed the 17 highly important clinical questions and rated 12 of 17 questions (71%) as high priority for research to answer. Nine of the 12 high-priority clinical questions were associated with aspects of anti-VEGF agents. We distributed 86 paper surveys to ACRC and Macula 2017 attendees and 34 of 86 surveys (40%) were returned. None of the ACRC and Macula 2017 respondents reported completing the online survey. In total, the prioritization surveys were viewed by 192 health care professionals and 124 of 192 professionals (65%) responded to at least 1 survey question.

There were similarities and differences among participants in the ASRS and ACRC and Macula 2017 cohorts (Table 2). Most respondents were US-based ophthalmologists specializing in the retina, had affiliation with at least one professional society, had experience working on RCTs, used systematic reviews for making treatment decisions, and reported no conflicts of interest. Many ASRS participants (61 of 90 [68%]) were self-employed or in private practice, whereas most ACRC and Macula 2017 participants (22 of 34 [65%]) were affiliated with academic centers. Eleven percent of ASRS participants (10 of 90) reported that 1% to 25% of their patients had AMD compared with 44% of ACRC and Macula 2017 participants (15 of 34); 54% of ASRS participants (49 of 90) reported that 26% to 50% of their patients had AMD compared with 18% of ACRC and Macula 2017 participants (6 of 34). Among ASRS respondents, 57% (51 of 90) were not members of any formal research group compared with 74% of ACRC and Macula 2017 respondents (25 of 34).

Table 2. Characteristics of the Clinical Survey Respondents.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ASRS (n = 90) | ACRC and Macula (n = 34) | |

| Area of expertisea | ||

| Retina | 84 (93) | 26 (77) |

| Anterior segment or cornea | 6 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Glaucoma | 4 (4) | 0 |

| Neuro-ophthalmology | 3 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Pediatric ophthalmology | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Oculoplastics | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Optometry | 1 (1) | 1 (3) |

| General ophthalmology | 9 (10) | 4 (12) |

| No response | 6 (7) | 3 (9) |

| Type of practice | ||

| Self-employed or private practice | 61 (68) | 9 (27) |

| Academic medical center or university | 18 (20) | 22 (65) |

| Government hospital or organization | 3 (3) | 2 (6) |

| For-profit hospital | 2 (2) | 1 (3) |

| No response | 6 (7) | 0 |

| Country of practice | ||

| United States | 63 (70) | 28 (82) |

| Outside the United States | 18 (20) | 2 (6) |

| No response | 9 (10) | 4 (12) |

| Patients with AMD | ||

| 1%-25% | 10 (11) | 15 (44) |

| 26%-50% | 49 (54) | 6 (18) |

| >50% | 25 (28) | 9 (27) |

| Do not see patients | 0 | 3 (9) |

| No response | 6 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Primary professional affiliation | ||

| Ophthalmologist | 84 (93) | 28 (82) |

| Other | 0 | 5 (15) |

| No response | 6 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Professional society affiliationsa | ||

| ASRS | 83 (92) | 18 (53) |

| AAO | 77 (86) | 24 (71) |

| ARVO | 30 (33) | 16 (47) |

| ASCRS | 6 (7) | 3 (9) |

| Macula Society | 12 (13) | 7 (21) |

| Other | 10 (11) | 5 (15) |

| No response | 6 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Research group affiliations | ||

| Cochrane Collaborative | 2 (2) | 0 |

| DRCRnet | 19 (21) | 4 (12) |

| None | 51 (57) | 25 (74) |

| No response | 19 (21) | 5 (15) |

| Randomized clinical trial experience | ||

| None | 14 (16) | 13 (38) |

| At least 1 clinical trial | 67 (74) | 19 (56) |

| 1-3 | 8 (9) | 6 (18) |

| 4-6 | 10 (11 | 2 (6) |

| ≥7 | 11 (12) | 7 (21) |

| Not specified | 37 (41) | 4 (12) |

| If at least 1, level of involvementa | ||

| Designed a multisite or single-site randomized clinical trial | 10 (11) | 7 (21) |

| Site participant for a multicenter randomized clinical trial | 56 (62) | 11 (32) |

| Other | 8 (9) | 4 (12) |

| No response | 9 (10) | 2 (6) |

| Systematic review publications | ||

| None | 54 (60) | 23 (68) |

| At least 1 | 16 (18) | 8 (24) |

| No response | 20 (22) | 3 (9) |

| Use systematic reviews to make treatment decisions | ||

| No | 3 (3) | 2 (6) |

| Yes | 77 (86) | 29 (85) |

| No response | 10 (11) | 3 (9) |

| Clinical practice guideline experience | ||

| No | 53 (59) | 26 (77) |

| Yes | 27 (30) | 7 (21) |

| No response | 10 (11) | 1 (3) |

| Potential conflicts of interest relevant to AMD research | ||

| No | 71 (79) | 32 (94) |

| Yes | 7 (8) | 1 (3) |

| No response | 12 (13) | 1 (3) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 76 (84) | 24 (71) |

| Female | 4 (4) | 9 (27) |

| No response | 10 (11) | 1 (3) |

| Decade of birth | ||

| 1950s or earlier | 27 (30) | 10 (29) |

| 1960s | 26 (29) | 4 (12) |

| 1970s | 15 (17) | 1 (3) |

| 1980s or later | 10 (11) | 7 (21) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| White | 68 (76) | 22 (65) |

| Other | 14 (16) | 12 (35) |

| No response | 12 (13) | 1 (3) |

| Hispanic origin | ||

| No | 65 (72) | 32 (94) |

| Yes | 9 (10) | 1 (3) |

| No response | 16 (1.8) | 1 (3) |

Abbreviations: AAO, American Academy of Ophthalmology; ACRC, Atlantic Coast Retina Conference; AMD, age-related macular degeneration; ARVO, Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, ASCRS, American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery; ASRS, American Society of Retina Specialists; DCRCNet, Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network.

Multiple answers allowed; total percentages may not add to 100.

Of the 17 tier 1 clinical questions, there was general agreement among respondents from the health care professional groups surveyed (Table 1). Both groups rated all 9 of the tier 1 clinical questions associated with anti-VEGF treatments as high priority. Two additional clinical questions were suggested by survey participants: (1) Which types of drug delivery systems are effective and safe? (2) Which interventions are effective and safe for treating or preventing geographic atrophy?

Of the 836 email addresses in the MD Support forum, 56 patients (7%) accessed the online prioritization survey and 46 of 56 patients (82%) participated in the survey. Half of the patients who responded had wet AMD (Table 3). Of 35 respondents with AMD, most had been diagnosed at least 1 year earlier, were women, were aged 70 years or older, and lived in the United States.

Table 3. Characteristics of Patient Survey Respondents.

| Characteristic | MD Support (n = 46), No. (%) |

|---|---|

| AMD diagnosis | |

| Yes | 35 (76) |

| Dry (nonexudative, nonneovascular) AMD | 12 (26) |

| Wet (exudative, neovascular) AMD | 23 (50) |

| None/no response | 11 (24) |

| Time since AMD diagnosis,a y | |

| <1 | 3 (7) |

| 1-5 | 9 (20) |

| 5-10 | 9 (20) |

| >10 | 14 (30) |

| Sexb | |

| Female | 28 (61) |

| Male | 9 (20) |

| Age, yb | |

| <70 | 11 (24) |

| 70 to <80 | 17 (37) |

| ≥80 | 9 (20) |

| Race/ethnicityb,c | |

| White | 37 (80) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (2) |

| Hispanic originb | |

| No | 37 (80) |

| Yes | 0 |

| Country of residenceb,c | |

| United States | 35 (76) |

| Outside the United States | 7 (15) |

| Highest level of educationb | |

| No 4-y college degree | 11 (24) |

| Bachelor's degree | 14 (30) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 12 (26) |

| Participation in a randomized clinical triald | |

| None | 31 (67) |

| At least 1 | 5 (11) |

| Use systematic reviews to make treatment decisionsd | |

| No | 14 (30) |

| Yes | 18 (39) |

| Not sure | 4 (9) |

Abbreviation: AMD, age-related macular degeneration.

No response for 11 of 46 survey participants.

No response for 9 of 46 survey participants.

Multiple answers allowed; total percentages may add to more than 100.

No response for 10 of 46 survey participants.

Participants from MD Support rated all 17 tier 1 clinical questions as high priority (Figure), with 12 of 17 questions given a median score of 10 (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). Survey participants suggested 4 additional clinical questions that were not included in the survey:

Is gene therapy (or stem cell therapy) effective in treating AMD?

Is the intraocular miniature telescope an effective treatment for AMD?

Are cholesterol-lowering diets effective in preventing or reducing AMD-related drusen?

What types of education improve living with AMD (eg, online support groups, communication with health care professionals)?

Six of 33 outcomes were identified as most important: choroidal neovascularization, development of advanced AMD, any retinal hemorrhage occurring with choroidal neurovascularization, gain of vision, vision loss, and serious ocular events (eg, endophthalmitis). Eight outcomes were scored as not highly important: copper deficiency anemia, cosmetic effects (eg, yellowing of skin), depression, falls, hospitalizations, lung cancer among smokers, visual hallucination, and vitreous floaters (Table 4). No additional outcomes were suggested by survey participants.

Table 4. Prioritization of Patient-Important Outcomes for Research in Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD).

| Clinical Outcomes Categorized by Members of MD Support | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly Important | Moderately Important | Least Important | Unsure (No Judgment) | |

| Cataract | 8 (33) | 9 (38) | 4 (17) | 3 (13) |

| Choroidal neovascularizationa | 24 (86) | 2 (7) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Copper deficiency anemiab | 0 | 7 (28) | 10 (40) | 8 (32) |

| Cornea problems | 12 (52) | 4 (17) | 4 (17) | 3 (13) |

| Cosmetic effects (eg, yellowing of skin)b | 0 | 3 (13) | 19 (79) | 2 (8) |

| Death | 12 (48) | 2 (8) | 6 (24) | 5 (20) |

| Depressionb | 3 (13) | 13 (57) | 6 (26) | 1 (4) |

| Development of advanced AMDa | 24 (83) | 4 (14) | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Development of blind spots | 14 (50) | 10 (36) | 4 (14) | 0 |

| Eye bleeding or discharge | 11 (50) | 7 (32) | 2 (9) | 2 (9) |

| Eye pain | 7 (28) | 12 (48) | 4 (16) | 2 (8) |

| Fallsb | 2 (9) | 9 (39) | 7 (30) | 5 (22) |

| Gain of visiona | 19 (70) | 5 (19) | 2 (7) | 1 (4) |

| Hemorrhage in the retina or inside of the eyea | 20 (74) | 7 (26) | 0 | 0 |

| Hospitalizationsb | 2 (9) | 9 (39) | 7 (30) | 5 (22) |

| Increased intraocular pressure | 11 (50) | 9 (41) | 2 (9) | 0 |

| Increased sensitivity to light | 5 (20 | 15 (60 | 5 (20 | 0 |

| Inflammation of the eye | 5 (21) | 13 (54) | 2 (8) | 4 (17) |

| Lung cancer among current and former smokersb | 2 (7) | 7 (26) | 8 (30) | 10 (37) |

| Near vision tasks such as reading | 11 (44) | 11 (44) | 3 (12) | 0 |

| Patient independence | 7 (28) | 12 (48) | 4 (16) | 2 (8) |

| Quality of life (eg, activities of daily living) | 11 (42) | 11 (42) | 4 (15) | 0 |

| Retinal pigment epithelium rips (tears) | 9 (38) | 6 (25) | 4 (17) | 5 (21) |

| Retinal scarring | 16 (67) | 3 (13) | 3 (13) | 2 (8) |

| Retinal thickness | 7 (29) | 7 (29) | 1 (4) | 9 (38) |

| Serious ocular adverse events (eg, endophthalmitisa) | 19 (76) | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) |

| Serious systemic adverse events (eg, stroke, heart attack) | 14 (52) | 4 (15) | 4 (15) | 5 (19) |

| Traumatic injury to the lens | 8 (32 | 5 (20 | 4 (16) | 8 (32) |

| Vision lossa | 21 (72) | 4 (14) | 2 (7) | 2 (7) |

| Visual acuity | 13 (57) | 6 (26) | 4 (17) | 0 |

| Visual function | 16 (64) | 4 (16) | 5 (20) | 0 |

| Visual hallucination (eg, Charles Bonnet syndrome)b | 2 (8) | 8 (33) | 8 (33) | 6 (25) |

| Vitreous floaters | 2 (8) | 11 (46) | 10 (42) | 1 (4) |

Abbreviation: MD, macular degeneration.

The outcome was rated “most important” by at least 70% of respondents.

The outcome was rated “most important” by fewer than 15% of respondents.

Discussion

The results of this priority-setting study suggest that research related to anti-VEGF treatments for AMD remains a key area of interest for multiple stakeholder groups. Nine of 17 highly important clinical questions identified by the AAO Retina/Vitreous Panel were associated with aspects of anti-VEGF treatments, all of which were rated as high priority by all prioritization survey cohorts. Previous research evaluating the reliability of systematic reviews of interventions for AMD also showed that anti-VEGF agents were the most common treatment modality evaluated by systematic reviewers.12 Although many high-quality RCTs and systematic reviews have addressed the effectiveness and safety of intravitreous anti-VEGF injections for AMD, new questions have emerged now that they have become the standard of care for neovascular AMD, concerning how frequently injections should be administered, the long-term (≥10 years) effects of these injections, and other possible drug delivery options.

Health care professionals and patients rated clinical questions addressing both effectiveness and safety as highly important. Furthermore, the highly important outcomes identified by patients in this study were balanced between intended effects of AMD treatment (eg, slowing vision loss) and adverse events (eg, retinal hemorrhage). This balance suggests research that examines potential benefits and harms together (eg, trade-off analysis) as an area for future investigation.

Methodologic Considerations

In this study, we evaluated a single method for prioritizing clinical research; another method may have led to other topics given priority. A priority-setting project in the United Kingdom that used a focus group format identified 29 priority questions related to AMD.19 However, their questions included question types not limited to treatment, such as “What is the cause of AMD?” and questions too broad for an RCT to address, such as “Can a treatment to stop dry AMD progressing and/or developing into the wet form be devised?” Our project was designed to include and prioritize only clinical questions for specific treatments.

As part of the study design, we asked the AAO Retina/Vitreous Panel to narrow the list of 70 clinical questions that we identified to a shortened list of highly important (tier 1) clinical questions. The rationale was to reduce the number of clinical questions for the larger groups to prioritize. However, even with a shortened survey, the response rate was low for all groups surveyed.

Patients rated all 17 clinical questions identified as highly important by the AAO Retina/Vitreous Panel as high priority, compared with 12 of 17 rated as high priority by both health care professional groups. When asked to rank the importance of outcomes by allocating outcomes into 1 of 4 categories, patients distinguished 6 highly important outcomes and 8 not so important outcomes among 33 outcomes assessed. Other patient-focused research has shown that patients tend to score all items as high priority when using rating scales, such as Likert scales.20 For prioritization research, asking participants to rank items rather than rating them independently may elicit clear patient preferences.

We identified at least 12 high-priority clinical research questions. Survey participants suggested additional areas of interest, such as alternative drug delivery systems, interventions for treating or preventing geographic atrophy, and effects of gene therapy. In a 2015 study of evidence used to underpin clinical practice guidelines, reliable systematic reviews were cited to support 15 of 35 treatment recommendations in the 2015 AAO PPP for AMD.12 Nine of the high-priority clinical questions identified by this prioritization project map to the 15 treatment recommendations with reliable systematic reviews available, suggesting that even with existing high-quality evidence, some uncertainty may remain as to whether a clinical question has been answered. For the remaining 8 highly important clinical questions identified by the AAO Retina/Vitreous Panel, no reliable systematic review had been identified, suggesting research areas with evidence gaps.

Limitations

A potential limitation to our framework is that we derived our initial set of clinical questions from clinical practice guidelines concurrently with the request for new clinical questions. Although evidence-based clinical practice guidelines may reflect the current state of prevention, screening and therapy from multiple stakeholder groups,4 they may not anticipate new treatments or areas of research. To address this issue, we consulted with members of the AAO Retina/Vitreous Panel to add relevant clinical questions to our initial set and provided survey participants opportunities to suggest additional research questions at each stage of the process.

Conclusions

The 6 highly important outcomes targeted by patients should be considered in the discussion of core outcome sets for studies that evaluate the treatment of AMD. Choroidal neovascularization and visual acuity are outcomes that have been noted frequently in outcome research related to AMD; however, retinal hemorrhage has been considered less frequently by clinicians and researchers.17,21,22 While we cannot assume that patients understand the AMD process, all patient participants were members of MD Support, an education-oriented support community for individuals with AMD. Further research could survey AMD patients more generally to see if there are different priorities or outcome concerns based on different levels of understanding of AMD.

eAppendix 1. Study Protocol

eAppendix 2. American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina/Vitreous Panel Scoring of Clinical Questions

eAppendix 3. Figure of Results of Prioritization of Tier 1 Clinical Question

References

- 1.Friedman DS, O’Colmain BJ, Muñoz B, et al. ; Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group . Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):564-572. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1941.00870100042005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paulus YM, Jefferys JL, Hawkins BS, Scott AW. Visual function quality of life measure changes upon conversion to neovascular age-related macular degeneration in second eyes. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(8):2139-2151. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1547-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18(suppl 3):280. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sackett D, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2nd ed Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al. ; Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group . Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the Users’ Guides to patient care. JAMA. 2000;284(10):1290-1296. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine Learning What Works Best: The Nation’s Need for Evidence on Comparative Effectiveness in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li T, Ervin AM, Scherer R, Jampel H, Dickersin K. Setting priorities for comparative effectiveness research: a case study using primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(10):1937-1945. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li T, Vedula SS, Scherer R, Dickersin K. What comparative effectiveness research is needed? a framework for using guidelines and systematic reviews to identify evidence gaps and research priorities. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(5):367-377. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu T, Li T, Lee KJ, Friedman DS, Dickersin K, Puhan MA. Setting priorities for comparative effectiveness research on management of primary angle closure: a survey of Asia-Pacific clinicians. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(5):348-355. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31829e5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le JT, Hutfless S, Li T, et al. Setting priorities for diabetic retinopathy clinical research and identifying evidence gaps. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;1(2):94-102. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saldanha IJ, Dickersin K, Hutfless ST, Akpek EK. Gaps in current knowledge and priorities for future research in dry eye. Cornea. 2017;36(12):1584-1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindsley K, Li T, Ssemanda E, Virgili G, Dickersin K. Interventions for age-related macular degeneration: are practice guidelines based on systematic reviews? Ophthalmology. 2016;123(4):884-897. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina/Vitreous Panel Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines: Age-Related Macular Degeneration San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology;2015. http://www.aao.org/ppp.

- 14.American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina/Vitreous Panel Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines: Age-Related Macular Degeneration San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology;2014. http://www.aao.org/ppp.

- 15.Custer RL, Scarcella JA, Stewart BR. The modified Delphi technique: a rotational modification. J Career Tech Educ. 1999;15(2):50-58. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saldanha IJ, Dickersin K, Wang X, Li T. Outcomes in Cochrane systematic reviews addressing four common eye conditions: an evaluation of completeness and comparability. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saldanha IJ, Lindsley K, Do DV, et al. Comparison of clinical trial and systematic review outcomes for the 4 most prevalent eye diseases. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(9):933-940. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.2583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials. 2012;13:132. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowe F, Wormald R, Cable R, et al. The Sight Loss and Vision Priority Setting Partnership (SLV-PSP): overview and results of the research prioritisation survey process. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7):e004905. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayo-Wilson E, Golozar A, Cowley T, et al. Methods to identify and prioritize patient-centered outcomes for use in comparative effectiveness research [published online June 12, 2018]. Pilot Feas Stud. doi: 10.1186/s40814-018-0284-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krezel AK, Hogg RE, Azuara-Blanco A. Patient-reported outcomes in randomised controlled trials on age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(11):1560-1564. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodrigues IA, Sprinkhuizen SM, Barthelmes D, et al. Defining a minimum set of standardized patient-centered outcome measures for macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;168:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Study Protocol

eAppendix 2. American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina/Vitreous Panel Scoring of Clinical Questions

eAppendix 3. Figure of Results of Prioritization of Tier 1 Clinical Question