Key Points

Question

Do patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland who have a close (≤1-mm) margin resection benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy?

Findings

In this case series of 45 patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland, 18 had close margins without other high-risk factors and were followed up for a median of 64.3 months. Of these, 10 received adjuvant radiotherapy, while 8 had no adjuvant therapy, and only 1 patient (who had received adjuvant radiotherapy) experienced a recurrence, at 136 months after surgery.

Meaning

Patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland who have a close margin resection but no other high-risk histopathologic features do not appear to benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy.

Abstract

Importance

The precise indications and oncologic effects of adjuvant radiotherapy in acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland are not well known, particularly in patients with negative, but close (≤1 mm), margins without other high-risk histopathologic factors.

Objective

To evaluate the oncologic outcomes of patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland and the results of adjuvant therapy for those with close (≤1-mm) margins.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In a retrospective case series with medical record review at a single academic tertiary referral center, patients treated surgically from January 2000 to December 2014 for acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland were identified from an institutional database. All data analysis was performed in September 2017.

Exposures

All patients underwent parotidectomy with or without adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was locoregional control. Secondary end points included recurrence patterns and survival.

Results

Forty-five patients were identified in this case series (23 [51%] female), with a mean (SD) age of 47.1 (19.5) years. The median follow-up in surviving patients was 56.7 months (range, 18.5-204 months). Four patients (9%) experienced recurrence (1 local and 3 distant) at a median of 67.3 months (range, 12.7-136 months) after surgery. Thirteen patients (29%) had at least one high-risk histopathologic factor (advanced T category, nodal disease, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, high-grade, or positive margins). The remaining 32 patients (71%) without these high-risk factors had significantly improved disease-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.01-0.71). Of patients without high-risk factors, those with close (≤1-mm) margins were significantly more likely to receive adjuvant radiotherapy (10 [56%] vs 1 [7%]; difference, 49%; 95% CI, 16%-82%), although this was not associated with disease control. At a median follow-up of 64.3 months (range, 33-204 months) in the 18 patients with close (≤1-mm) margins without other high-risk factors (10 with adjuvant radiotherapy and 8 without adjuvant therapy), only 1 patient (who had received adjuvant radiotherapy) experienced a recurrence, at 136 months after surgery.

Conclusions and Relevance

Patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland whose only histopathologic risk factor is a close (≤1 mm) but negative margin do not appear to benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy. Recurrent disease is rare but may occur many years after initial treatment, and patients with acinic cell carcinoma could benefit from lifelong clinical surveillance.

This case series evaluates the oncologic outcomes of patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland and the results of adjuvant therapy for those with close (≤1-mm) margins.

Introduction

Acinic cell carcinoma of the head and neck is an uncommon salivary gland cancer, with a reported incidence of less than 1 case per 100 000 population.1 More than 80% of acinic cell carcinomas occur in the parotid gland, and most commonly manifest in the fourth through sixth decades of life.2 Most of these parotid acinic cell carcinomas are local stage and well differentiated at presentation, with excellent long-term disease control when managed with primary surgery alone.3 However, a subset of patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland have a higher risk of recurrence, metastasis, and significantly worse survival outcomes. Several such risk factors have been previously identified, including advanced T category and N category, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, high-grade histopathology, and positive surgical margins.3,4

These high-risk factors are commonly used as indications for postoperative radiotherapy.3,5,6 However, available data specific to acinic cell carcinoma are limited, and such indications are largely extrapolated from the management of head and neck mucosal squamous cell carcinoma or from pooled analyses of resected malignant salivary gland tumors of multiple different histologies.6,7,8 Although patients with acinic cell carcinoma at the highest risk of recurrent disease, such as those with extracapsular extension or positive margins, appear to benefit from adjuvant therapy, the effect of postoperative radiotherapy is less clear in those patients at lower risk.9

In particular, for resected acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland with close margins but without other high-risk features, the added benefit of radiotherapy remains controversial. While the definition of close margins is variably described in the literature, reports of low-grade salivary gland cancers with negative but 1-mm to 5-mm surgical margins have shown excellent locoregional control and survival with surgery alone.10,11 Conversely, a microscopically positive margin has been a consistent negative prognostic factor and frequent indication for adjuvant radiotherapy.10 However, the management of patients with negative but 1-mm or less surgical margins is less certain. Some authors have defined surgical margins of 1 mm or less as positive, although cancer cells may not be specifically detected at the inked resection edge.11 However, because of the anatomic constraints of the parotid gland, tumors often approximate branches of the facial nerve but do not directly involve the nerve. Resection necessitates the creation of a “close but clear” surgical margin as the tumor is completely removed and the uninvolved, and functional, nerve is preserved. Nonetheless, tumor cells may be in close proximity to the specimen edge, despite a negative margin resection. Close but negative margins may occur in more than 30% of patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland.10

The objectives of this retrospective case series were to evaluate the oncologic outcomes of patients with surgically managed acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland and to specifically examine those without high-risk features who have negative, but close (≤1 mm), margins. The long-term recurrence patterns and the role of adjuvant radiotherapy in this patient population are also evaluated.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review was performed of patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland treated at a single academic tertiary referral center (Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston) from January 2000 to December 2014. All data analysis was performed in September 2017. Included patients underwent parotidectomy for tumor resection with or without ipsilateral neck dissection and with or without adjuvant therapy. Patients were excluded from the study if they had distant metastatic disease on presentation, did not undergo up-front surgical resection, or had prior head and neck radiotherapy. All data collection and analysis were approved by the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Institutional Review Board, which waived the need for informed patient consent.

When performed, elective neck dissection routinely included levels 2 and 3 and the posterior aspect of level 1b, preserving the submandibular gland. In the presence of clinical nodal disease, the levels of dissection were extended as indicated. Adjuvant therapy was determined by a multidisciplinary tumor board team, guided by histopathologic risk factors, and was evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Standard indications for adjuvant radiotherapy included advanced T category, positive nodal disease, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, high-grade histology, or positive margins. There were no defined policies regarding administration of adjuvant therapy in patients with close margins but no such high-risk features during the study period. All patients were evaluated in the full context of their unique clinical scenario and pathological data.

Parotid gland resection specimens were received fresh (unfixed) at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Department of Pathology and were specifically evaluated by a head and neck pathologist. Before fixation with 10% formaldehyde, each specimen was assessed for several variables. The specimen weight was recorded, and the overall size of the specimen was measured in 3 dimensions in centimeters. Notation was made of any surface lesions, including the presence of tumor extending to the outer surgical resection margin. Next, black ink was applied along the entire outer parotid gland surface to designate the surgical resection margin, and dilute acetic acid was used to fix the black ink. For parotid gland resections with orienting sutures, the specimens were overinked in a separate color to designate a particular orientation, such as “superficial and superior.” Next, the prosector serially sectioned the parotid gland, and the size of the tumor was measured in 3 dimensions. In addition, measurements of the distance of tumor to the closest inked margins were documented in centimeters. Tumors were described in terms of their color, consistency, nodularity, circumscription, and relationship to the surrounding parotid gland parenchyma. For parotid glands measuring less than 4 cm in greatest diameter, the entire specimen was generally submitted for microscopic evaluation after fixation in 10% formaldehyde. For larger specimens, representative sections of the tumor (2-3 sections per centimeter) were processed, including the interface of the tumor with the surrounding normal parotid gland, as well as sections of the tumor closest to the inked margins. Any intraparotid or periparotid lymph nodes were also measured and submitted entirely for microscopic evaluation.

Data collection included demographics, tumor, and treatment details, as well as recurrence and survival outcomes. Close margins were determined from the pathology report and were defined as a negative margin resection, with the nearest margin 1 mm or less. High-risk histopathologic factors were defined as T3-4 category, positive nodal disease, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, high-grade, or positive margins. The primary end point was locoregional control. Secondary end points included recurrence patterns, overall survival (OS), and disease-free survival (DFS). Statistical analysis was performed using a software program (SPSS, version 22; IBM). Descriptive statistics were used to define the study population. Comparative analyses of categorical variables were performed with χ2 test or Fisher exact test as indicated. Cox proportional hazards regression survival univariable analyses were used to investigate risk factors associated with DFS. Survival estimates were examined with Kaplan-Meier analyses.

Results

Forty-five patients treated at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary for acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland were identified. Baseline demographics, tumor, and treatment characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median follow-up in surviving patients was 56.7 months (range, 18.5-204 months). Four patients (9%) experienced recurrence at a median of 67.3 months (range, 12.7-136 months) after surgery. Three recurrences (7%) were distant metastases, including 1 pulmonary, 1 liver, and 1 calvarial bone. Only 1 recurrence (2%) was local, and no patient experienced a regional recurrence. Seven patients (16%) underwent elective neck dissection, and no occult neck metastases were identified. Only 1 patient in this study was found to have an occult nodal metastasis, which was intraparotid. Five-year Kaplan-Meier OS and DFS estimates for the entire group were 93% (95% CI, 91%-97%) and 89% (95% CI, 83%-95%), respectively (Figure 1).

Table 1. Demographics, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics.

| Variable | (N = 45) |

|---|---|

| Female sex, No. (%) | 23 (51) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 47.1 (19.5) |

| Extent of resection, No. (%) | |

| Superficial parotidectomy | 20 (44) |

| Total parotidectomy | 25 (56) |

| Neck dissection, No. (%) | |

| Elective | 7 (16) |

| Therapeutic | 2 (4) |

| Pathological T category, No. (%) | |

| T1-2 | 37 (82) |

| T3-4a | 8 (18) |

| Pathological N category, No. (%) | |

| N0/Nx | 42 (93) |

| N+ | 3 (7) |

| Tumor size, median (range), cm | 2.1 (1-4) |

| High grade, No. (%) | 2 (4) |

| Final margin positive, No. (%) | 7 (16) |

| Lymphovascular invasion, No. (%) | 2 (4) |

| Perineural invasion, No. (%) | 1 (2) |

| Extracapsular extension, No. (%) | 1 (2) |

| ≥1 High-risk histopathologic factor, No. (%)a | 13 (29) |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy, No. (%) | 22 (49) |

High-risk histopathologic factors include T3-4a, N+, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, high-grade, or positive margins.

Figure 1. Overall and Disease-Free Survival.

Shown are Kaplan-Meier estimates for overall (solid line) and disease-free (dashed line) survival for the entire study cohort.

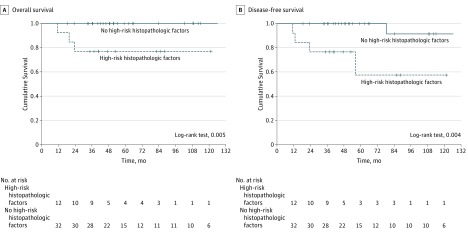

Twenty-two patients (49%) received adjuvant radiotherapy (3 of whom were also given chemotherapy). Thirteen of the 45 patients (29%) had at least one high-risk histopathologic factor and were significantly more likely to receive adjuvant radiotherapy (11 [85%] vs 11 [34%]; difference, 51%; 95% CI, 19%-83%) than patients not demonstrating these features. Six patients (13%) had T4a disease, all with facial nerve involvement requiring resection and nerve grafting. Thirty-two patients (71%) did not have any of the defined high-risk histopathologic factors. Kaplan-Meier estimates for both OS and DFS were significantly higher in patients without these risk factors (log-rank test, 0.005 and 0.004, respectively) (Figure 2). In a univariable analysis of demographics, tumor, and treatment characteristics, only the absence of defined histopathologic risk factors was significantly associated with improved DFS (Table 2).

Figure 2. Overall and Disease-Free Survival in Patients Without High-Risk Histopathologic Factors.

Shown are Kaplan-Meier estimates for overall (A) and disease-free (B) survival in patients with (dashed line) and without (solid line) at least one high-risk histopathologic factor (T3-4a, N+, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, high-grade, or positive margins).

Table 2. Univariable Analysis of Risk Factors for Disease-Free Survival.

| Variable | Disease-Free Survival HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age <47.1 vs ≥47.1 y | 0.01 (0.01-20.08) |

| Extent of resection superficial vs total parotidectomy | 1.88 (0.34-10.88) |

| Neck dissection | 4.97 (0.77-32.72) |

| Pathological T category T1-2 vs T3-4a | 0.19 (0.03-1.20) |

| Pathological N category N0/Nx vs N+ | 0.36 (0.11-1.20) |

| Tumor size <2.1 vs ≥2.1 cm | 0.15 (0.02-1.25) |

| Final margin positive | 3.72 (0.62-22.31) |

| No high-risk histopathologic factorsa | 0.08 (0.01-0.71) |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 2.47 (0.45-13.65) |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

High-risk histopathologic factors include T3-4a, N+, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, high-grade, or positive margins.

Of the 32 patients without the defined histopathologic risk factors, patients with close (≤1-mm) margins (n = 18) were significantly more likely to receive adjuvant radiotherapy (10 [56%] vs 1 [7%]; difference, 49%; 95% CI, 16%-82%). Of the 18 patients with close margins but without other histopathologic risk factors, 10 received adjuvant radiotherapy and 8 did not undergo adjuvant therapy. In these patients at a median follow-up of 64.3 months (range, 33-204 months), only 1 recurrence occurred, a calvarial metastasis at 136 months after surgery in a patient who had received adjuvant radiotherapy after the initial parotidectomy. Of these 18 patients, there were no significant differences in demographics, tumor, or treatment variables between those undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy compared with observation (Table 3).

Table 3. Demographics, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics in Patients With Close (≤1-mm) Surgical Margins but No High-Risk Histopathologic Factorsa.

| Variable | Observation (n = 8) | Adjuvant Radiotherapy (n = 10) | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 40.5 (24.1) | 50.6 (13.2) | 10.1 (−8.7 to 28.9) |

| Extent of resection, No. (%) | |||

| Superficial parotidectomy | 5 (63) | 2 (20) | 43 (−15 to 100) |

| Total parotidectomy | 3 (38) | 8 (80) | |

| Elective neck dissection, No. (%) | 1 (13) | 1 (10) | 3 (−100 to 100) |

| Pathological T category, No. (%) | |||

| T1 | 6 (75) | 3 (30) | 45 (−17 to 100) |

| T2 | 2 (25) | 7 (70) | |

| Tumor size, median (range), cm | 1.5 (1 to 4) | 2.4 (2 to 4) | 0.9 (−0.1 to 1.9) |

High-risk histopathologic factors include T3-4a, N+, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, high-grade, or positive margins.

Discussion

In patients with localized, low-grade acinic cell carcinoma tumors of the parotid gland without identified high-risk histopathologic factors, the presence of close margins (≤1 mm) did not affect locoregional control, and these patients did not appear to benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy. The definition of close margins has been variably reported in the literature by different authors for different head and neck subsites and histologies. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network12 guidelines define close margins as less than 5 mm and provide a consensus recommendation for adjuvant radiotherapy in resected salivary gland cancer with close margins. However, the literature cited in support of this recommendation is composed of pooled retrospective analyses of multiple different salivary gland histologies, each study with less than 20% acinic cell carcinoma. Furthermore, none of these reports evaluate the role of adjuvant radiotherapy in low-risk patients with close but otherwise negative surgical margins.13,14,15

In resected salivary gland cancer, some authors have defined any margin of 1 mm or less as a positive margin.11 However, margin assessment is subject to several processing and analytic variabilities, including tissue shrinkage and reporting inconsistencies.16,17 More important than arbitrary cutoff values to define a margin as positive or close are the prognostic implications of margin assessment for a particular histology and disease subsite. In low-risk patients in this study, provided that cancer cells were not detected at the inked resection edge, margins of 1 mm or less were not associated with local recurrence in any patient with or without adjuvant radiotherapy. This is likely related to the anatomic boundaries of the parotid gland, within which tumors often directly abut branches of the facial nerve. For low-grade, early-stage patients without high-risk histopathologic factors, the facial nerve perineurium appears to provide an anatomic boundary to direct tumor invasion, and narrow but negative resection margins were sufficient to prevent local recurrence without adjuvant therapy in this study.

In support of this concept, several studies9,10,18 have failed to identify an added benefit of adjuvant therapy in low-risk low-grade resected salivary gland cancer. Stodulski et al11 reported on 32 patients with low-grade or intermediate-grade parotid carcinoma with surgical margins ranging from 1 mm to 3 mm treated without adjuvant radiotherapy. They found a local recurrence rate of less than 10%, without any recurrent disease in patients with acinic cell histology. However, in the presence of other histopathologic risk factors, including advanced T category, nodal disease, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, or cancer cells at the inked resection margin, the addition of adjuvant radiotherapy is frequently recommended and may significantly improve locoregional control and survival.10,19 Nonetheless, patients with close margins are often grouped in analysis with those who have positive margins, and treatment recommendations for adjuvant therapy are extrapolated from such pooled analyses.20

Overall, similar to prior studies,3,6,10 patients with acinic cell carcinoma managed with parotidectomy and selective use of adjuvant therapy demonstrated excellent locoregional control and long-term survival in this study, with most relapses occurring as late distant metastases. No regional recurrences or cervical occult metastases were detected, despite almost 30% (13 of 45) of patients having at least one high-risk histopathologic feature. Furthermore, patients who were initially seen with gross clinical neck disease all achieved long-term regional control with neck dissection and adjuvant therapy. Although other authors have found a small decrease in regional recurrence with elective neck dissection for acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland, nodal disease in these patients is rare, and salvage therapy is effective at achieving regional control.6 Together, these data suggest that elective neck dissection may be omitted in patients with low-grade acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. The draining parotid basin appears to be at a similarly low risk of lymphatic spread, with only 1 patient (2%) in this study developing an intraparotid metastasis. However, given the increased risk of facial nerve paresis or paralysis in reoperative salvage parotidectomy, complete superficial parotidectomy may be considered for clearance and staging of the intraparotid lymphatic basin.21

Although rare, the major source of disease failure in patients with acinic cell carcinoma is not locoregional but distant relapse. Neskey et al6 reviewed the long-term oncologic outcomes of 155 patients with head and neck acinic cell carcinoma and found that almost 20% developed distant metastases, which were the dominant cause of disease-specific mortality. These often occur many years after initial treatment; although pulmonary metastases are most common, other organ systems may be involved, including intra-abdominal, osseous, and central nervous system metastases.6,22 A similar phenomenon was seen in the present study, with a calvarial metastasis occurring more than 11 years after the initial parotidectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy. Unfortunately, there is no clear effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on distant metastatic rates, and the role of systemic therapies in the management of distant metastatic acinic cell carcinoma has yet to be well defined.23,24

Limitations

This study has some limitations. It is limited by its single-institution, retrospective design and sample size. Of patients with close (≤1-mm) margins but without high-risk features, there were no statistically significant tumor or treatment differences identified between patients who received observation vs postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy (Table 3). However, those receiving observation vs adjuvant radiotherapy had more total parotidectomies (38% vs 80%) and more T2 tumors (25% vs 70%). While each patient was individually evaluated by a multidisciplinary tumor board to determine the need for adjuvant therapy, the specific records of those discussions and all the factors taken into consideration were not available for review. In addition, since 2000, new salivary gland cancers, such as mammary analogue secretory carcinoma, have been described that can be similar in pathological appearance to acinic cell carcinoma. While the original specimens could not be obtained for further immunohistochemistry in this study, the head and neck pathologists who initially reviewed these cases are well versed in these newly described salivary gland cancers, making a misdiagnosis unlikely. Future multi-institutional and prospective trials are needed to confirm the results of this study. In this group, otherwise low-risk patients with close margins who underwent surgery alone, the median follow-up was 110.5 months.

Conclusions

Patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland with high-risk histopathologic factors can be managed with surgery and adjuvant therapy, with excellent locoregional control. Those whose only risk factor is a close (≤1-mm) margin may not benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy. The major source of relapse in these patients is distant and may be found in several different organ systems, often many years after initial treatment. As such, patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland may benefit from lifelong clinical surveillance. Future developments in systemic therapy are needed for the prevention and management of distant disease.

References

- 1.Patel NR, Sanghvi S, Khan MN, Husain Q, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Demographic trends and disease-specific survival in salivary acinic cell carcinoma: an analysis of 1129 cases. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(1):172-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Robinson RA, Pinkston JA, Menck HR. National Cancer Data Base report on cancer of the head and neck: acinic cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 1999;21(4):297-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez DR, Katabi N, Zhung J, et al. . Clinical and pathologic prognostic features in acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. Cancer. 2009;115(10):2128-2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Su M, Yang Y, Zhao B, Qin L, Han Z. Prognostic factors associated with decreased survival in patients with acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(2):416-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sood S, McGurk M, Vaz F. Management of salivary gland tumours: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(S2):S142-S149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neskey DM, Klein JD, Hicks S, et al. . Prognostic factors associated with decreased survival in patients with acinic cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(11):1195-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safdieh J, Givi B, Osborn V, Lederman A, Schwartz D, Schreiber D. Impact of adjuvant radiotherapy for malignant salivary gland tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157(6):988-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen AM, Granchi PJ, Garcia J, Bucci MK, Fu KK, Eisele DW. Local-regional recurrence after surgery without postoperative irradiation for carcinomas of the major salivary glands: implications for adjuvant therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67(4):982-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakst RL, Su W, Ozbek U, et al. . Adjuvant radiation for salivary gland malignancies is associated with improved survival: a National Cancer Database analysis. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2017;2(2):159-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho JK, Lim BW, Kim EH, et al. . Low-grade salivary gland cancers: treatment outcomes, extent of surgery and indications for postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(13):4368-4375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stodulski D, Mikaszewski B, Majewska H, Wiśniewski P, Stankiewicz C. Close surgical margin after conservative parotidectomy in early stage low-/intermediate-grade parotid carcinoma: outcome of watch and wait policy. Oral Oncol. 2017;68:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Head and Neck Cancer. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed April 28, 2018.

- 13.Nagliati M, Bolner A, Vanoni V, et al. . Surgery and radiotherapy in the treatment of malignant parotid tumors: a retrospective multicenter study. Tumori. 2009;95(4):442-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell RB, Dierks EJ, Homer L, Potter BE. Management and outcome of patients with malignant salivary gland tumors. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(7):917-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cederblad L, Johansson S, Enblad G, Engström M, Blomquist E. Cancer of the parotid gland: long-term follow-up: a single centre experience on recurrence and survival. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(4):549-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinstock YE, Alava I III, Dierks EJ. Pitfalls in determining head and neck surgical margins. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2014;26(2):151-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alicandri-Ciufelli M, Bonali M, Piccinini A, et al. . Surgical margins in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: what is “close”? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270(10):2603-2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreoli MT, Andreoli SM, Shrime MG, Devaiah AK. Radiotherapy in parotid acinic cell carcinoma: does it have an impact on survival? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(5):463-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terhaard CH, Lubsen H, Van der Tweel I, et al. ; Dutch Head and Neck Oncology Cooperative Group . Salivary gland carcinoma: independent prognostic factors for locoregional control, distant metastases, and overall survival: results of the Dutch head and neck oncology cooperative group. Head Neck. 2004;26(8):681-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richter SM, Friedmann P, Mourad WF, Hu KS, Persky MS, Harrison LB. Postoperative radiation therapy for small, low-/intermediate-grade parotid tumors with close and/or positive surgical margins. Head Neck. 2012;34(7):953-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wittekindt C, Streubel K, Arnold G, Stennert E, Guntinas-Lichius O. Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland: analysis of 108 consecutive patients. Head Neck. 2007;29(9):822-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khelfa Y, Mansour M, Abdel-Aziz Y, Raufi A, Denning K, Lebowicz Y. Relapsed acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland with diffuse distant metastasis: case report with literature review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2016;4(4):2324709616674742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amini A, Waxweiler TV, Brower JV, et al. . Association of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy vs radiotherapy alone with survival in patients with resected major salivary gland carcinoma: data from the National Cancer Data Base. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142(11):1100-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alfieri S, Granata R, Bergamini C, et al. . Systemic therapy in metastatic salivary gland carcinomas: a pathology-driven paradigm? Oral Oncol. 2017;66:58-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]