This cross-sectional study compares the prices of topical glaucoma medications, laser trabeculoplasty, and trabeculectomy with median annual household income for countries worldwide.

Key Points

Question

How affordable are common interventions for glaucoma (medications, laser trabeculoplasty, and trabeculectomy) for patients living in developing and developed countries throughout the world?

Findings

The annual cost of latanoprost, laser trabeculoplasty, and trabeculectomy were 2.5% or more of the median annual household income in 41%, 44%, and 78% of countries studied, respectively. Substantial variability in pricing was noted across countries for the glaucoma interventions studied.

Meaning

Successfully reducing global blindness from glaucoma requires addressing multiple contributing factors, including making glaucoma interventions more affordable.

Abstract

Importance

Medical and surgical interventions for glaucoma are effective only if they are affordable to patients. Little is known about how affordable glaucoma interventions are in developing and developed countries.

Objective

To compare the prices of topical glaucoma medications, laser trabeculoplasty, and trabeculectomy relative with median annual household income (MA-HHI) for countries worldwide.

Design, Setting and Participants

Cross-sectional observational study. For each country, we obtained prices for glaucoma medications, laser trabeculoplasty, and trabeculectomy using government pricing data, drug databases, physician fee schedules, academic publications, and communications with local ophthalmologists. Prices were adjusted for purchasing power parity and inflation to 2016 US dollars, and annual therapy prices were examined relative to the MA-HHI. Interventions costing less than 2.5% of the MA-HHI were considered affordable.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Daily cost for topical glaucoma medications, cost of annual therapy with glaucoma medications, laser trabeculoplasty, and trabeculectomy relative to MA-HHI in each country.

Results

Data were obtained from 38 countries, including 17 developed countries and 21 developing countries, as classified by the World Economic Outlook. We observed considerable variability in intervention prices compared with MA-HHI across the countries and across interventions, ranging from 0.1% to 5% of MA-HHI for timolol, 0.1% to 27% for latanoprost, 0.2% to 17% for laser trabeculoplasty, and 0.3% to 42% for trabeculectomy. Timolol was the most affordable medication in all countries studied and was 2.5% or more of MA-HHI in only 2 countries (5%). The annual cost of latanoprost was 2.5% or more of MA-HHI in 15 countries (41%) (15 developing countries [75%] and no developed countries). The cost of laser trabeculoplasty was 2.5% or more of the MA-HHI in 15 countries (44%) (11 developing countries [65%] and 4 developed countries [24%]). The cost of trabeculectomy was 2.5% or more of the MA-HHI in 28 countries (78%) (18 developing countries [95%] and 10 developed countries [59%]). In 18 countries (53%), laser trabeculoplasty cost less than a 3-year latanoprost supply.

Conclusions and Relevance

For many patients worldwide, the costs of medical, laser, and incisional surgical interventions were 2.5% or more of the MA-HHI. Successfully reducing global blindness from glaucoma requires addressing multiple contributing factors, including making glaucoma interventions more affordable.

Introduction

Glaucoma will likely affect more than 110 million persons by 2040, with most patients (three-quarters) residing in developing countries.1,2 Effective intraocular pressure (IOP)–lowering therapies—including medications, laser trabeculoplasty (LTP), and incisional surgery—exist but are useful only if patients have access to and can afford them.

Studies have described costs for glaucoma therapies in the United States, Canada, and Europe,3,4,5,6 but few have examined costs elsewhere, especially in developing countries.7,8 The World Health Organization and Health Action International monitor prices for many systemic drugs in countries worldwide but not routinely for glaucoma.9 Because glaucoma is a chronic disease, often requiring continued long-term therapy, relatively costly medications would make regular use over time difficult. Complicating matters, in many developing countries, access to glaucoma medications is limited, as is access to laser or incisional glaucoma surgeries.10 A better understanding of the costs of different glaucoma interventions and how they vary among countries worldwide is useful in determining strategies to most effectively treat patients with glaucoma in resource-rich and resource-limited settings.

We compared the prices of various glaucoma medications, LTP, and trabeculectomy in 38 countries worldwide and studied the prices of these treatments relative to the median annual household income (MA-HHI) in each country to determine the affordability of these therapies for a person of average socioeconomic means.

Methods

We gathered pricing information on topical glaucoma medications, LTP, and trabeculectomy from as many countries as possible. We successfully obtained data from 38 countries, including 17 of the top 25 most populated countries worldwide (Table 1). Countries were identified as developed or developing based on their World Economic Outlook classification.11

Table 1. Daily Cost in US Dollars of Most Affordable Glaucoma Medication in Each Class by Country.

| Country | PGA | BB | AA | CAI | BB + PGAa | BB + AAa | BB + CAIa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Americas | |||||||

| Brazil | 0.85 | 0.12 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 1.07 | 1.20 | 0.91 |

| Canada | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.53 | 0.31 |

| Chile | 1.17 | 0.30 | 2.01 | 1.46 | 1.47 | 2.01 | 2.10 |

| Guatemala | NA | 0.50 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2.07 |

| Jamaica | 3.29 | 0.47 | 1.65 | 1.24 | NA | 2.35 | 1.84 |

| Mexico | 1.50 | 0.11 | 1.36 | 1.25 | 1.82 | 2.07 | 0.58 |

| Paraguay | 0.95 | 0.34 | 0.74 | NA | NA | NA | 0.91 |

| United States | 1.62 | 0.38 | 0.97 | 1.04 | NA | 5.29 | 1.83 |

| Europe | |||||||

| Austria | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.66 |

| France | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.74 | 0.33 |

| Germany | 0.81 | 0.53 | NA | 0.89 | 1.08 | NA | 1.02 |

| Greece | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.59 | 0.46 |

| Italy | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.78 | 0.32 |

| Lithuania | 0.52 | 0.17 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.70 | 0.97 | 0.57 |

| Norway | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.53 | 0.48 |

| Russia | 1.76 | 0.09 | 0.98 | 0.58 | NA | NA | 1.40 |

| Spain | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.84 | 0.60 |

| Switzerland | 0.57 | 0.19 | 0.73 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 0.84 |

| Turkey | 0.38 | 0.13 | 1.50 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 0.69 | 0.36 |

| United Kingdom | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.47 | 0.12 |

| Africa | |||||||

| Egypt | 1.03 | NA | 0.75 | 0.55 | NA | NA | 0.93 |

| Ethiopia | 1.22 | 0.10 | 0.87 | 1.02 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ghana | 1.61 | 0.28 | 1.02 | 0.59 | 3.01 | 1.14 | 1.41 |

| Nigeria | 2.63 | 0.42 | NA | 2.46 | NA | NA | NA |

| South Africa | 1.32 | 0.52 | 1.43 | 1.01 | 1.49 | 1.68 | 1.62 |

| Asia | |||||||

| Bahrain | 1.20 | 0.18 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 1.21 | NA | 1.58 |

| China | 1.35 | 0.02 | NA | 0.70 | NA | NA | NA |

| India | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.48 |

| Israel | 0.36 | 0.16 | NA | 0.30 | 0.42 | 0.69 | 0.38 |

| Japan | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 0.98 | NA | 1.03 |

| Nepal | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 0.52 | NA | NA | NA |

| Saudi Arabia | 1.11 | 0.45 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 1.49 | 1.42 | 1.16 |

| Singapore | 0.94 | 0.12 | 1.10 | 1.24 | 1.30 | 1.35 | 1.73 |

| South Korea | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.30 | NA | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.43 |

| Qatar | 0.81 | 0.53 | NA | 0.89 | 1.08 | NA | 1.02 |

| Thailand | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 1.22 | 1.26 | 1.24 | 1.67 |

| United Arab Emirates | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.59 | 0.46 |

| Australia | |||||||

| Australia | 0.57 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.57 |

Abbreviations: AA, α-agonist; BB, topical β-blocker; CAI, topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor; NA, not available; PGA, prostaglandin analog.

Fixed-dose combination medications.

Pricing Data Collection

We sought to study prices borne by the patient for various glaucoma interventions. Because no universal data source captures prices patients pay for ophthalmic medications and other ophthalmic interventions for all countries, we used various data sources, including prices published by government entities on publicly available websites, academic publications, and drug-pricing databases.12 If we could not locate data from any of these sources, we contacted ophthalmologists practicing in the country of interest (eTable in the Supplement). When prices for a specific medication or procedure in a given country varied depending on the data source used, we calculated the mean prices across sources. Because all data came from publicly available sources or personal communications, the University of Michigan institutional review board determined the study did not require its approval.

Glaucoma Medications

Medication classes of interest included topical prostaglandin analogs (PGAs), β-blockers (BBs), α-agonists (AAs), carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs), and fixed-dose combination medications (CAIs + BBs, AAs + BBs, PGAs + BBs). If multiple bottle sizes were available in a given country, prices for the smallest size were recorded. Prices were recorded separately for generic and brand name formulations. If multiple generic products with the same active ingredient were available, prices were averaged and reported as mean values. While pricing data were collected for various different medications, many of our analyses focused on the most affordable medication in each class. For generic timolol, prices were recorded for the 0.5% formulation. For bimatoprost, we used the more widely available 0.1% concentration in all countries except Japan, where the formulary includes only the 0.3% concentration. For AAs, prices for the cheaper of the 0.15% and 0.2% formulations were recorded. Preservative-free formulations were excluded owing to their limited availability.

We estimated the cost of a year’s supply of the medication of interest for treatment of both eyes. In previous studies, multiple factors determine the number of bottles a patient uses.13 We simplified our calculations by assuming that a 2.5-mL bottle of medication with once-daily dosing (PGAs) would treat both eyes for 1 month and a 5-mL bottle with twice-daily dosing (BBs, AAs, and CAIs) would treat both eyes for 1 month. To calculate daily costs, we divided the monthly cost by the mean days per month (30.4). We assumed that the number of bottles needed annually did not vary between eye drop formulations with the same active ingredient. Although variations have previously been shown to exist,13,14 the multitude of generic and name brands available in different countries made determining these variations for each individual agent impractical.

Glaucoma Surgeries

We included prices per eye for any type of LTP (argon, selective, and micropulse LTP). For incisional glaucoma surgery, we focused on trabeculectomy prices per eye. We excluded glaucoma drainage devices or minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries, as these interventions were unavailable in many of the countries studied. Prices for LTP and trabeculectomy were obtained from the sources listed in the eTable in the Supplement and recorded as price to the patient per procedure per eye, or in countries with health insurance programs, as reimbursement fee per procedure per eye. Prices for procedures performed in the United States were obtained from the 2016 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.15 For Canada, we averaged prices from 3 provinces because there is known variation in price among provinces.16 To simplify crosscountry comparisons, glaucoma surgery prices excluded charges for anesthesia, hospitalization, or costs for postoperative visits or to manage complications.

Analysis

All prices were adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates.9,17 The PPP exchange rate accounts for differences in purchasing power between countries so that adjusted prices can be directly compared. Purchasing power parity–adjusted exchange rates are calculated by comparing the prices of goods and services between the country of interest and an index country—in this case, the United States. We used PPP exchange rates calculated by the World Bank to convert prices of glaucoma interventions from local currencies into US dollars using a basket of all goods and services.18 When necessary, prices were adjusted for inflation using each country’s Consumer Price Index.

To assess the affordability of therapies in each country, we divided prices for each therapy by the country’s MA-HHI. This provides an indicator of the economic burden imposed by the intervention on an average middle-class family in the country.19 Median annual household income data were unavailable for a few countries. In these countries, the gross domestic product per capita adjusted for PPP was substituted. There is no universally accepted threshold for affordability. Others have used 5% of MA-HHI as an affordability threshold for some life-threatening diseases.20,21 Because glaucoma is not life-threatening but can be sight-threatening, we selected 2.5% as our threshold.

For selected analyses, we divided the cost of LTP or trabeculectomy by that of a 3-year supply of generic latanoprost or generic latanoprost plus a generic BBs to obtain a cost ratio, providing a sense of variations in costs for medical vs surgical interventions. In these analyses we assumed patients were adherent to medications, and the LTP or trabeculectomy was effective for the 3-year period. In additional analyses, we divided the price of brand-name latanoprost, Xalatan, by that of generic latanoprost to obtain a price ratio in countries with pricing data for both medications.

Results

We obtained pricing data for 38 countries: 17 developed (44.7%) and 21 developing (55.3%). Eight countries (21.1%) were in the Americas, 12 (31.6%) in Europe, 5 (13.2%) in Africa, 13 (34.2%) in Asia/Middle East/Australia. These countries together comprise more than 60% of the world population, including 17 of the 25 most populous countries. Pricing data for PGAs, BBs, AAs, and CAIs were available in 37, 37, 32, and 35 countries, respectively; for LTP and trabeculectomy, data were available in 34 and 36 countries, respectively.

Daily-Use Drug Prices

β-Blockers were the cheapest class in all 37 countries with data available. The lowest daily-use price was in China ($0.02/d), and the highest was in Germany and Qatar ($0.53/d)—a 27-fold difference. Topical CAIs and AAs were generally costlier than BBs but equally or less expensive compared with PGAs. Prostaglandin analogs were the costliest medication class in 20 of the 37 countries (54.1%). The PGA price was lowest in the United Kingdom ($0.08/d) and highest in Jamaica ($3.29/d)—a 41-fold difference.

Within each country, daily-use prices differed greatly between the cheapest and most expensive medication classes, ranging from a 1.3-fold difference in France ($0.21/d for AA vs $0.27/d for PGA) to 68-fold in China ($0.02/d for BB vs $1.35/d for PGA) (Table 1).

Cost of Treatments Relative to Household Income

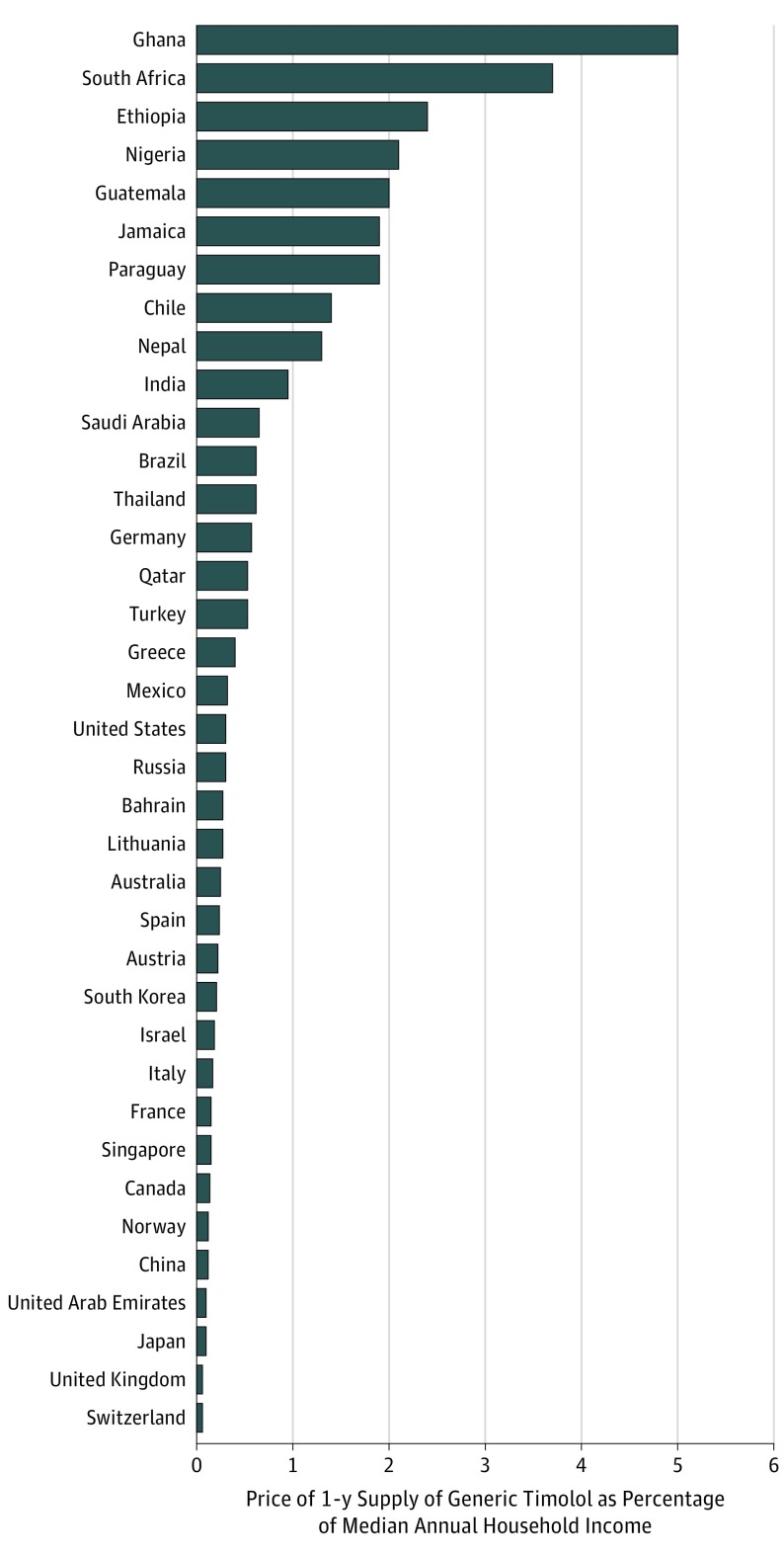

Timolol

The cost of 1-year’s timolol supply compared with MA-HHI was lowest in Switzerland (0.06%) and the United Kingdom (0.06%), 0.31% in the United States, and highest in Ghana (5%) (Figure 1). A 1-year timolol supply cost 2.5% or more of MA-HHI in only 2 of 37 countries (5.4%), both of them developing countries. A 1-year timolol supply compared with MA-HHI was lower than that of any generic or branded PGA in every country studied.

Figure 1. Cost of 1-Year Supply of Generic Timolol as a Percentage of Median Annual Household Income.

Prices for generic timolol were divided by the median annual household income in each country and expressed as a percentage. Prices were calculated for 1 year of generic timolol therapy for both eyes. Data were not available for Egypt.

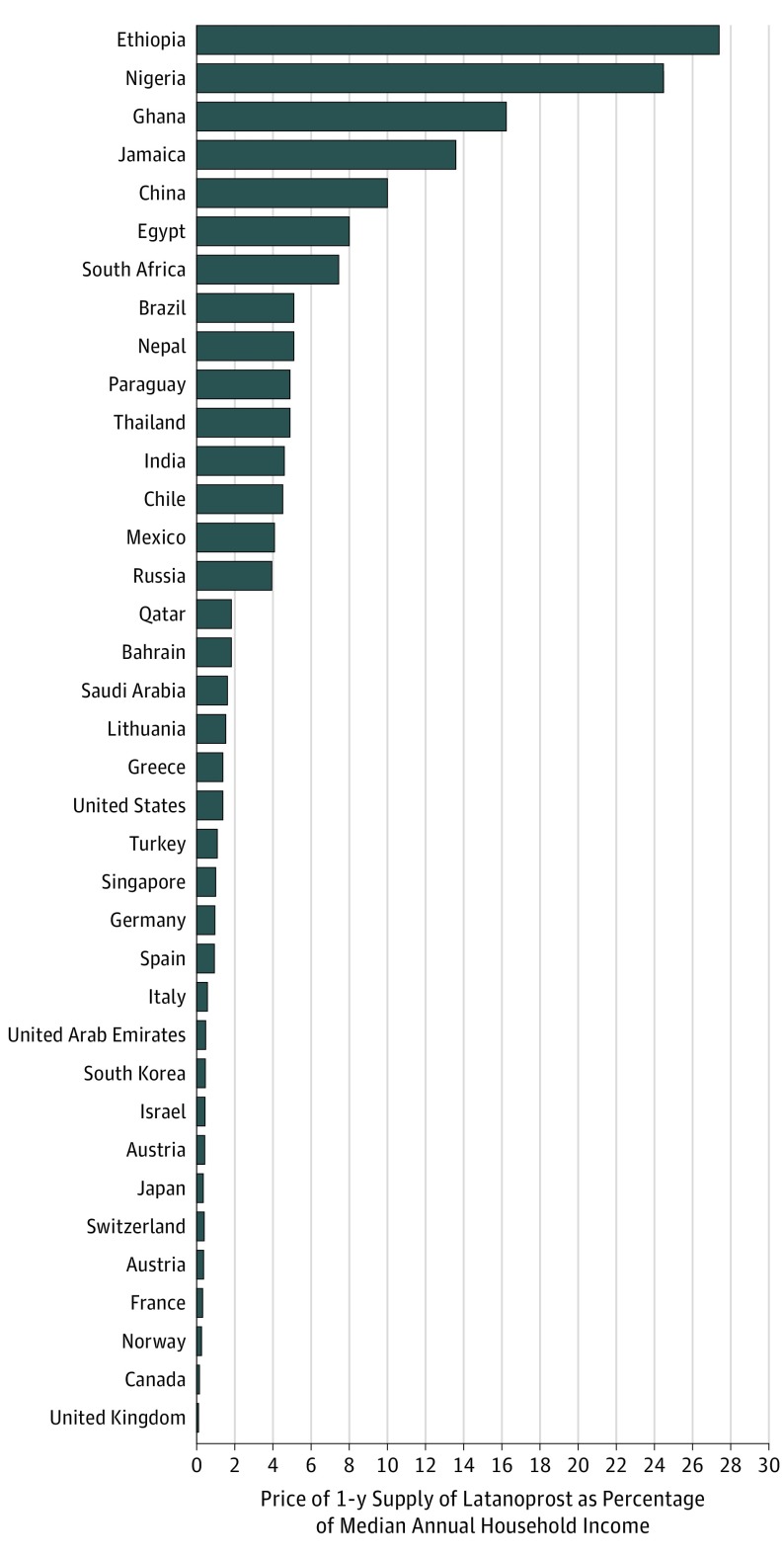

Latanoprost

The cost of 1-year’s latanoprost supply relative to MA-HHI was lowest in the United Kingdom (0.09%) and Canada (0.20%), 1.3% in the United States, and highest in Ethiopia (27.4%) (Figure 2). A 1-year supply was 2.5% or more of MA-HHI in 15 countries (41%), including 15 developing countries (75%) and no developed nations. The price ratio for brand name to generic latanoprost was lowest in Norway (0.8) and Greece (0.6). It was 1.0, indicating no price difference between the generic and brand name products, in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Austria, Australia, and Israel. The United States had the highest ratio (3.5) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Cost of 1-Year Supply of Generic Latanoprost as a Percentage of Median Annual Household Income.

Prices for generic latanoprost were divided by the median annual household income in each country and expressed as a percentage. Prices were calculated for 1 year of generic latanoprost therapy for both eyes. Data were not available for Guatemala.

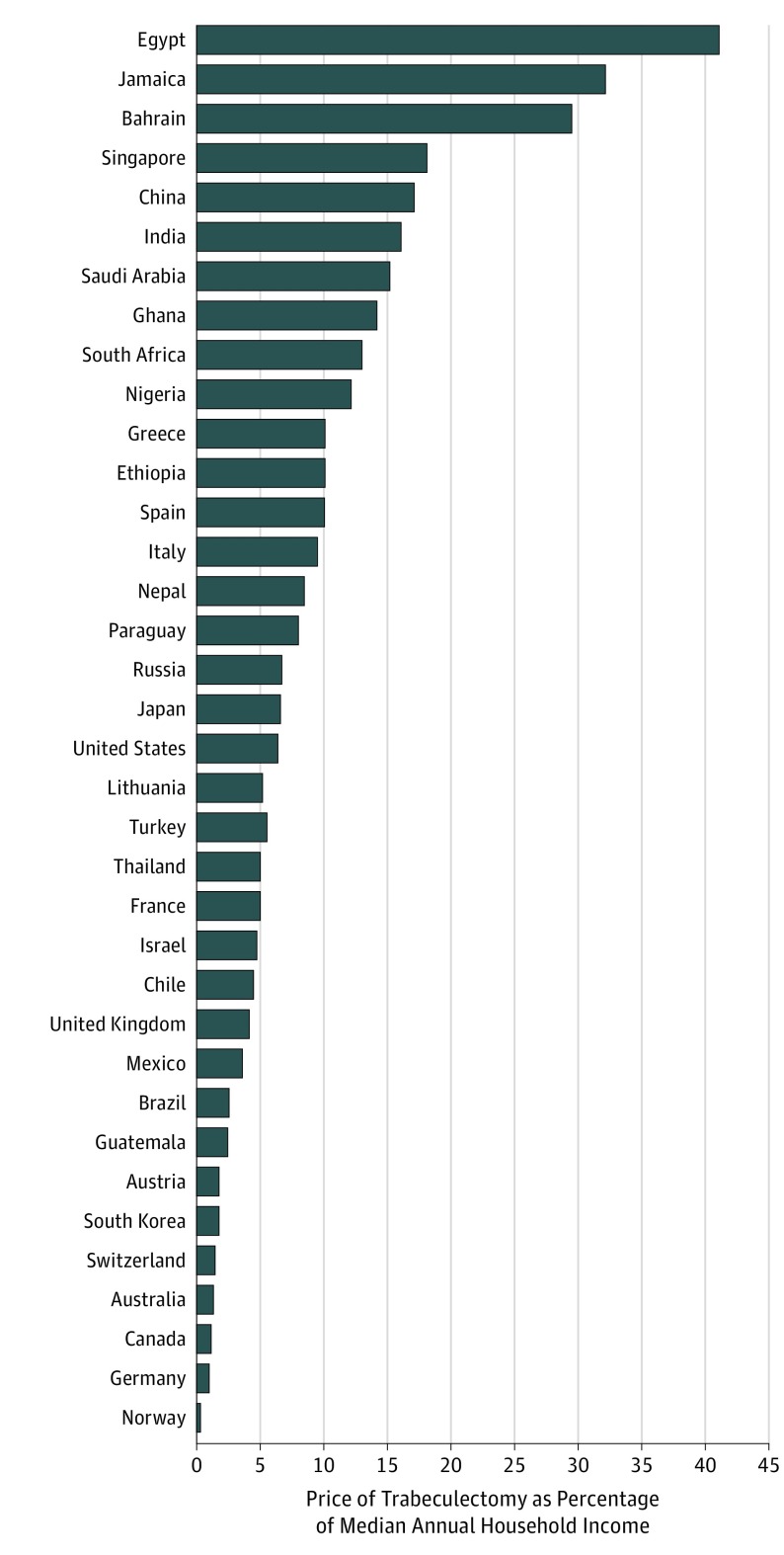

Surgery

The cost of LTP relative to MA-HHI was lowest in Switzerland (0.2%) and Brazil (0.22%). In the United States, the cost compared with MA-HHI was 1.6%. It was highest in Egypt (16.7%) and Jamaica (15.8%) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). After adjustment for relative differences in MA-HHI, LTP was 84-times costlier in Egypt than in Switzerland. In 15 countries (44%) (11 developing countries [65%] and 4 developed countries [24%]), LTP cost was 2.5% or more of the MA-HHI. For trabeculectomy, the cost compared with MA-HHI was lowest in Norway (0.3%) and Germany (0.9%). The cost compared with MA-HHI was 6.4% in the United States; it was highest in Jamaica (32.8%) and Egypt (41.7%) (Figure 3). After adjustment for MA-HHI, trabeculectomy was 139-fold costlier in Egypt than in Norway. In 28 countries (78%) (18 developing countries [95%] and 10 developed countries [59%]), trabeculectomy cost was 2.5% or more of MA-HHI. Table 2 summarizes the cost in different countries of medications, LTP, and trabeculectomy as a proportion of MA-HHI.

Figure 3. Cost of Trabeculectomy as a Percentage of Median Annual Household Income.

Prices for trabeculectomy were divided by the median annual household income in each country and expressed as a percentage. Prices are reported as individually charged surgical procedures per eye. Data were not available for United Arab Emirates and Qatar.

Table 2. Proportion of Median Annual Household Income for Common Medical and Surgical Interventions for Glaucoma for Each Countrya.

| Country | Timolol | Latanoprost | Laser Trabeculoplasty | Trabeculectomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | 0.13b | 0.25b | 0.30b | 0.30b |

| Germany | 0.57b | 0.97b | 0.50b | 0.90b |

| Canada | 0.14b | 0.20b | 0.37b | 1.10b |

| Australia | 0.24b | 0.41b | 0.60b | 1.30b |

| Switzerland | 0.06b | 0.34b | 0.20b | 1.40b |

| South Korea | 0.22b | 0.43b | 2.10b | 1.70b |

| Austria | 0.22b | 0.33b | 0.70b | 1.70b |

| Guatemala | 2.00b | NA | NA | 2.40b |

| Brazil | 0.61b | 5.10c | 0.22b | 2.60c |

| Mexico | 0.33b | 4.10c | 0.68b | 3.60c |

| United Kingdom | 0.06b | 0.09b | 0.50b | 4.20c |

| Chile | 1.40b | 4.60c | 4.35c | 4.50c |

| Israel | 0.18b | 0.42b | 0.30b | 4.70c |

| France | 0.16b | 0.32b | 0.50b | 5.00c |

| Thailand | 0.61b | 4.80c | 2.50c | 5.00c |

| Turkey | 0.53b | 1.10b | 2.00b | 5.60c |

| Lithuania | 0.26b | 1.50b | 3.00c | 6.10c |

| United States | 0.31b | 1.30b | 1.61b | 6.40c |

| Japan | 0.09b | 0.38b | 2.50b | 6.60c |

| Russia | 0.30b | 3.90c | 2.30b | 6.80c |

| Paraguay | 1.90b | 4.80c | 2.90c | 8.00c |

| Nepal | 1.30b | 5.10c | 2.50c | 8.40c |

| Italy | 0.16b | 0.57b | 0.60b | 9.50c |

| Spain | 0.23b | 0.89b | 1.70b | 10.30c |

| Ethiopia | 2.40b | 27.40c | 1.40b | 10.70c |

| Greece | 0.41b | 1.30b | 3.10c | 10.90c |

| Nigeria | 2.10b | 24.40c | 6.70c | 12.10c |

| South Africa | 3.70c | 7.40c | 6.90c | 13.00c |

| Ghana | 5.00c | 16.30c | NA | 14.30c |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.65b | 1.60b | 2.90c | 15.50c |

| India | 0.96b | 4.70c | 10.00c | 16.10c |

| China | 0.13b | 10.00c | 2.20b | 17.60c |

| Singapore | 0.14b | 1.00b | 3.40c | 18.10c |

| Bahrain | 0.27b | 1.80b | 10.20c | 24.40c |

| Jamaica | 1.90b | 13.60c | 15.80c | 32.80c |

| Qatar | 0.53b | 1.80b | NA | NA |

| United Arab Emirates | 0.09b | 0.47b | NA | NA |

| Egypt | NA | 8.00c | 16.70c | 41.70c |

Abbreviations: MA-HHI, median annual household income; NA, not available.

Prices for timolol, latanoprost, laser trabeculoplasty, and trabeculectomy were divided by the MA-HHI in each country and expressed as a percentage.

Treatment cost less than 2.5% of the MA-HHI.

Treatment cost more than 2.5% of the MA-HHI.

Relative Costs of Medication vs Other Interventions

To further analyze differences in cost between different treatments, we divided the cost of bilateral LTP by the cost of a 3-year supply of generic latanoprost to calculate a price ratio. Ratios smaller than 1 indicate that bilateral LTP was cheaper; ratios larger than 1 indicate that PGA was cheaper. The countries with the lowest cost ratio were Brazil, Ethiopia, and Mexico. The United Kingdom, Bahrain, and Japan had the highest ratios. In 18 countries (53%) LTP cost less than a 3-year latanoprost supply. The cost ratio was smaller than 1 in 12 developing countries (71%) and larger than 1 in 11 developed countries (65%) (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Next, we compared the 3-year price of dual therapy (PGA and BB) vs bilateral trabeculectomy. Ethiopia and Nigeria had the lowest ratios, and the United Kingdom and Singapore had the highest. In 22 countries (65%) bilateral trabeculectomy cost more than a 3-year supply of dual therapy (eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

We know of no prior studies comparing costs of glaucoma therapies among countries worldwide. Here we compared prices of topical medications, LTP, and trabeculectomy in 38 countries, representing approximately two-thirds of the world population. For commonly used therapies such as PGAs, LTP, and trabeculectomy, the proportion of countries studied where these interventions cost 2.5% or more of the MA-HHI were 41%, 44%, and 78%, respectively, and for those living in developing countries, 75%, 65%, and 95%, respectively. These findings highlight the nonaffordability of existing glaucoma therapies, especially for patients living in developing nations.

Everywhere, generic timolol was substantially more affordable than other medications. A year’s supply was less than 2.5% of the MA-HHI in all except 2 countries. While some patients cannot tolerate this medication, timolol seems like a viable option for many patients with glaucoma worldwide. However, our analyses revealed that for patients requiring more than 1 medication class to lower IOP sufficiently, the fixed-dose combination products could be unaffordable for many patients.

Prostaglandin analogs are the most common first-line glaucoma therapy in the United States because of their effectiveness, once-daily dosing, and limited adverse effects.22 In our analyses, the price of a year’s supply of latanoprost is 2.5% or more of the MA-HHI for patients in 75% of developing countries, indicating that PGAs may be unaffordable for much of the developing world. A lack of affordability is known to be associated with medication nonadherence,23,24,25 contributing to disease progression.

Clinicians practicing in developing countries may wish to consider LTP or trabeculectomy for patients whose IOP cannot be controlled with timolol alone. Bilateral LTP was less expensive than a 3-year supply of PGA in 71% of developing countries. A previous study found that for many patients, LTP was more cost-effective than PGA therapy.3 Given that nonadherence rates are likely to be even higher in developing countries where access to glaucoma medications is difficult, LTP may be a viable alternative for many patients. For example, Realini26 demonstrated favorable results using SLT to lower IOP and reduce glaucoma progression in St Lucia. Besides affordability, the availability of lasers and skilled ophthalmologists to perform LTP and equipment costs are additional considerations.

While in countries such as the United States, incisional surgery is often reserved for patients in whom other therapies have failed, our analyses highlight how incisional surgery may be a viable alternative for many patients living in developing nations since the long-term cost of medication use is much higher than that of bilateral trabeculectomy. Other surgical benefits include the potential need for less long-term follow-up care and avoidance of glaucoma medication use afterward. Nevertheless, incisional surgery has its own challenges. As with LTP, proper equipment and trained clinicians are required. Also, there is an additional cost of adjunctive corticosteroids and antimetabolites to consider, plus medication costs if surgery fails. Moreover, given the importance of postoperative care to the success of these surgeries, undergoing these interventions may be logistically challenging for some patients. For incisional surgery to be a reasonable option for patients in developing countries, patients must be educated about the goals of the surgery (to prevent future glaucomatous vision loss) and expectations properly set.

Medication prices in the United States were high for a developed country. This finding is consistent with a study finding that identical eye drops were considerably costlier in the United States compared with Canadian pharmacies.14 We found that brand name latanoprost cost 3.5-times more than generic latanoprost. This finding reflects US pharmaceutical pricing trends, where per-capita spending on pharmaceutical products, especially branded medications, is high. Reasons for relatively higher medication prices in the United States include market exclusivity for patent-protected medications, delayed entry and reduced access to generic medications, and limited ability of insurers to negotiate drug prices.27 By comparison, several other countries we studied can offer medications at lower prices because the government negotiates directly with pharmaceutical companies. Additionally, some countries have local pharmaceutical companies that manufacture medications at low cost, such as India’s Aravind Eye Care System. United States–based clinicians, medical professional societies, and patient/consumer advocacy groups should engage health policy makers on challenging pharmaceutical companies to make medications more affordable. Making interventions for glaucoma more affordable could substantially reduce glaucoma-related vision loss, increasing patients’ quality of life and potentially reducing patient falls, fractures, and nursing-home admissions due to glaucoma-attributed suboptimal vision.28,29

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, we intended to study the costs of these interventions borne by patients. In countries where health insurance is unavailable (many developing nations), the costs we report likely reflect the actual costs to patients. However, in countries with health insurance (most developed nations), the costs borne by patients may differ from the values our data sources capture; patient costs, including not only out-of-pocket costs, but also taxes, copays, deductibles, etc, may be difficult to accurately quantify. This can be particularly challenging in countries with nationalized health care systems, such as the United Kingdom, since the costs of interventions are shared among all citizens in the form of taxes. We looked to data sources such as national fee schedules, but how well these sources fully capture both the direct out-of-pocket expenses plus indirect costs to support the infrastructure to permit a patient to receive these glaucoma interventions is unclear. Second, we obtained pricing data from a mean of 2 sources per country, and the prices reported could vary by region within each country. While we averaged prices to obtain reasonably accurate pricing data for persons residing in a given country, these prices may not capture cost variation within each country, and patients in some areas of a country could encounter prices lower or higher than the mean prices listed. Third, we assumed that a 2.5-mL bottle of eye drops for both eyes taken once daily will last 1 month, an assumption that can be challenged.13 Costs will vary according to the actual number of bottles required. Fourth, we did not consider the availability of eye care, availability of medications, or the accessibility of laser or incisional surgery. Affordability of care is only 1 of many factors that affect outcomes. Other care barriers include insufficient access to eye care providers (leading to late presentation), transportation difficulties, logistical issues with drug manufacturing, importation, distribution, storage, and lack of trained personnel. All of these factors undoubtedly also affect which patients can benefit from different interventions. Fifth, our analyses did not consider costs of hospitalizations, anesthesia services, or postoperative visits associated with trabeculectomy. While these services are bundled into the cost of surgery for patients living in some of the countries we studied, in others, these services may be billed separately. As such we may be underestimating the total cost of trabeculectomy in some countries. Sixth, our cost ratios of medication to LTP or trabeculectomy assumed excellent adherence and successful IOP lowering for the 3 years. If these assumptions are untrue, the cost ratios could differ. Finally, receipt of interventions through charity programs or the dispensing of medication samples, which could be free of charge to patients were not considered.

Conclusions

Unfortunately, for many patients with glaucoma, living in developed and especially developing nations, the cost of various interventions for glaucoma is 2.5% or more of the MA-HHI. To effectively reduce global blindness from glaucoma, researchers could work with health policy makers, governmental agencies, and pharmaceutical companies to make interventions more affordable.

eFigure 1. Price Ratio of Brand Name Xalatan versus Generic Latanoprost

eFigure 2. Cost of Laser Trabeculoplasty as a Percentage of Median Annual Household Income

eFigure 3. Price Ratio of Trabeculoplasty versus Latanoprost Therapy

eFigure 4. Price Ratio of Trabeculectomy versus Latanoprost + Timolol Therapy

eTable. List of data sources arranged by country

References

- 1.Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081-2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262-267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein JD, Kim DD, Peck WW, Giannetti SM, Hutton DW. Cost-effectiveness of medications compared with laser trabeculoplasty in patients with newly diagnosed open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(4):497-505. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.2727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee R, Hutnik CM. Projected cost comparison of selective laser trabeculoplasty versus glaucoma medication in the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41(4):449-456. doi: 10.1016/S0008-4182(06)80006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan RI, De Moraes CG, Cioffi GA, Al-Aswad LA, Blumberg DM. Comparative cost-effectiveness of the baerveldt implant, trabeculectomy with mitomycin, and medical treatment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(5):560-567. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Traverso CE, Walt JG, Kelly SP, et al. Direct costs of glaucoma and severity of the disease: a multinational long term study of resource utilisation in Europe. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(10):1245-1249. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.067355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazcano-Gomez G, Hernandez-Oteyza A, Iriarte-Barbosa MJ, Hernandez-Garciadiego C. Topical glaucoma therapy cost in Mexico. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34(2):241-249. doi: 10.1007/s10792-013-9823-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omoti AE, Edema OT, Akpe BA, Musa P. Cost analysis of medical versus surgical management of glaucoma in Nigeria. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2010;5(4):232-239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falvey M, ed. Measuring Medicine Prices, Availability, Affordability, and Price Components. 2nd ed Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008, http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/access/OMS_Medicine_prices.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnikoff S, Felch W, Gauthier TM, Spivey B. The number of ophthalmologists in practice and training worldwide: a growing gap despite more than 200,000 practitioners. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(6):783-787. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World economic outlook financial surveys. International Monetary Fund; 2018. hhttp://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2018/01/weodata/groups.htm. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- 12.Red Book Online. Truven Health Analytics Micromedex 2.0. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 13.Fiscella RG, Green A, Patuszynski DH, Wilensky J. Medical therapy cost considerations for glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(1):18-25. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00102-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlenker MB, Trope GE, Buys YM. Comparison of United States and Canadian glaucoma medication costs and price change from 2006 to 2013. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:547960. doi: 10.1155/2015/547960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Physician Fee Schedule CMS. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. hthttps://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/. Accessed July 25, 2018.

- 16.Buys YM, Austin PC, Campbell RJ. Effect of physician remuneration fees on glaucoma procedure rates in Canada. J Glaucoma. 2011;20(9):548-552. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181fa0e90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Mourik MS, Cameron A, Ewen M, Laing RO. Availability, price and affordability of cardiovascular medicines: a comparison across 36 countries using WHO/HAI data. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2010;10:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-10-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $). World Bank Open Data.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP?end=2016&start=2016&vie%20w=map. Accessed July 25, 2018.

- 19.Countries Ranked by Median Self-Reported Per-Capita and Household Income Gallup, Inc; 2013. https://news.gallup.com/poll/166211/worldwide-median%20household-income-000.aspx. Accessed July 25, 2018.

- 20.Niëns LM, Brouwer WBF. Measuring the affordability of medicines: importance and challenges. Health Policy. 2013;112(1-2):45-52. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baird KE. The financial burden of out-of-pocket expenses in the United States and Canada: how different is the United States? SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:2050312115623792. doi: 10.1177/2050312115623792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein JD, Ayyagari P, Sloan FA, Lee PP. Rates of glaucoma medication utilization among persons with primary open-angle glaucoma, 1992 to 2002. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1315-1319, 1319.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein JD, Shekhawat N, Talwar N, Balkrishnan R. Impact of the introduction of generic latanoprost on glaucoma medication adherence. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(4):738-747. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman-Casey PA, Robin AL, Blachley T, et al. The most common barriers to glaucoma medication adherence: a cross-sectional survey. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(7):1308-1316. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamrat L, Gessesse GW, Gelaw Y. Adherence to topical glaucoma medications in Ethiopian patients. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22(1):59-63. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.148350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Realini T. Selective laser trabeculoplasty for the management of open-angle glaucoma in St Lucia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(3):321-327. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutton D, Newman-Casey PA, Tavag M, Zacks D, Stein J. Switching to less expensive blindness drug could save Medicare part B $18 billion over a ten-year period. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(6):931-939. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramulu PY, van Landingham SW, Massof RW, Chan ES, Ferrucci L, Friedman DS. Fear of falling and visual field loss from glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1352-1358. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramulu P. Glaucoma and disability: which tasks are affected, and at what stage of disease? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20(2):92-98. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32832401a9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Price Ratio of Brand Name Xalatan versus Generic Latanoprost

eFigure 2. Cost of Laser Trabeculoplasty as a Percentage of Median Annual Household Income

eFigure 3. Price Ratio of Trabeculoplasty versus Latanoprost Therapy

eFigure 4. Price Ratio of Trabeculectomy versus Latanoprost + Timolol Therapy

eTable. List of data sources arranged by country