Abstract

Importance

Patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC) are often uninsured or underinsured at the time of their diagnosis. This access to care has been shown to influence treatment decisions and survival outcomes.

Objective

To examine the association of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) health care legislation with rates of insurance coverage and access to care among patients with HNSCC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospectively gathered data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database were used to examine rates of insurance coverage and access to care among 89 038 patients with newly diagnosed HNSCC from January 2007 to December 2014. Rates of insurance were compared between states that elected to expand Medicaid coverage in 2014 and states that opted out of the expansion. Statistical analysis was performed from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2014.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Rates of insurance coverage and disease-specific and overall survival.

Results

Among 89 038 patients newly diagnosed with HNSCC (29 384 women and 59 654 men; mean [SD] age, 59.8 [7.6] years), there was an increase after implementation of the ACA in the percentage of patients enrolled in Medicaid (16.2% after vs 14.8% before; difference, 1.4%; 95% CI, 1.1%-1.7%) and private insurance (80.7% after vs 78.9% before; difference, 1.8%; 95% CI, 1.2%-2.4%). In addition, there was a large decrease in the rate of uninsured patients after implementation of the ACA (3.0% after vs 6.2% before; difference, 3.2%; 95% CI, 2.9%-3.5%). This decrease in the rate of uninsured patients and the associated increases in Medicaid and private insurance coverage were only different in the states that adopted the Medicaid expansion in 2014. No survival data are available after implementation of the ACA, but prior to that point, from 2007 to 2013, uninsured patients had reduced 5-year overall survival (48.5% vs 62.5%; difference, 14.0%; 95% CI, 12.8%-15.2%) and 5-year disease-specific survival compared with insured patients (56.6% vs 72.2%; difference, 15.6%; 95% CI, 14.0%-17.2%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Access to health care for patients with HNSCC was improved after implementation of the ACA, with an increase in rates of both Medicaid and private insurance and a 2-fold decrease in the rate of uninsured patients. These outcomes were demonstrated only in states that adopted the Medicaid expansion in 2014. Uninsured patients had poorer survival outcomes.

This population-based study uses data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database to examine the association of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act with rates of insurance coverage and access to care among patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer.

Key Points

Question

What is the association of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act with rates of insurance coverage and access to care among patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer?

Findings

This population-based study used prospectively gathered data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database and found an increase in the percentage of patients enrolled in Medicaid and private insurance and a large decrease in the rates of uninsured patients after implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in states that adopted the Medicaid expansion in 2014. Patients who were uninsured prior to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act had poorer survival outcomes.

Meaning

With the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, there has been a substantial reduction in uninsured patients and improved access to health care among patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer.

Introduction

Since the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted in March 2010, there has been a nationwide effort to reduce the number of uninsured individuals in the United States and increase the accessibility of health care.1 As the largest change in US health care since the formation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, the major structural components of the ACA included the following: increasing the age at which children are covered by a parent’s insurance, removing barriers to obtaining insurance by reforming practices of insurance companies, requiring individuals to have a prescribed minimum level of health insurance, creating health insurance exchanges for ease in purchasing plans, and providing states with the option to expand Medicaid.2 With open enrollment beginning in October 2013 and Medicaid expansion available in January 2014, Medicaid eligibility would now include individuals with incomes up to 138% of the poverty level in participating states.3 From 2010 to 2015, the number of uninsured individuals in the United States decreased from 49 million to 29 million, heralding the largest decrease in more than 5 decades.4 Although the increased rates of insured individuals are compelling, there is some uncertainty regarding the future of the ACA, making it necessary to evaluate the outcomes of this notable piece of legislation.

It has been long established that insurance status effects the continuum of cancer care, from prevention and diagnosis to medical and surgical management of disease.5 Specifically, among patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC), it has been reported that those who are uninsured or have Medicaid and Medicare disability coverage have a lower rate of survival compared with individuals who have private insurance.6 Furthermore, Rohlfing et al7 demonstrated that insurance status is associated with tumor stage, comorbidity burden, length of hospital stay, and complications. Chen et al8,9 supported this notion by demonstrating that uninsured patients or those with Medicaid coverage often present with advanced oropharyngeal and laryngeal cancer. Lack of insurance can also delay time to treatment, which adversely affects survival.10 Although HNSCC represents just 4% of all malignant neoplasms in patients in the United States, the morbidity and mortality rates associated with this type of cancer are high, making adequate health insurance all the more important.11 In 2008 prior to the implementation of the ACA, it was estimated that more than 47 000 individuals would receive a diagnosis of oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx cancer, with an estimated 11 260 deaths related to these cancers.12 Although data have demonstrated that there are increased rates of insurance coverage since implementation of the ACA, no studies have examined the association of the ACA with insurance coverage among patients with HNSCC and how this change in insurance status is associated with prognosis and survival.

A recent study conducted by Moss et al13 examined the association of the ACA with gynecologic malignant neoplasms. Using data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, that study found that the ACA was able to increase insurance coverage among this population of patients with cancer, especially among states that participated in the Medicaid expansion. Further analysis completed by Moss et al14 again demonstrated increased insurance coverage among patients who received a diagnosis of colon, lung, or breast cancer when Moss et al14 examined rates of health insurance coverage before and after the passage of the ACA. Results from these studies were insightful, which prompted us to evaluate the outcomes of the ACA legislation specifically with regard to patients with HNSCC. Because a large percentage of patients with HNSCC are often uninsured or underinsured at the time of diagnosis, our primary objective was to determine the association of the ACA with the rate of uninsured patients with newly diagnosed HNSCC in a population-based analysis.

Methods

All patients with newly diagnosed HNSCC (as defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology15) from January 2007 to December 2014 were extracted from tumor registries in 18 areas from the SEER database. This information included the following primary sites and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes: malignant neoplasms of the lip (ICD-9 code 140); tongue (ICD-9 code 141); gum (ICD-9 code 143); floor of mouth (ICD-9 code 144); other and unspecified parts of mouth (ICD-9 code 145); oropharynx (ICD-9 code 146); nasopharynx (ICD-9 code 147); hypopharynx (ICD-9 code 148); other and ill-defined sites within the lip, oral cavity, and pharynx (ICD-9 code 149); nasal cavities, middle ear, and accessory sinuses (ICD-9 code 160); and larynx (ICD-9 code 161). Only squamous cell carcinoma histologic findings were included. Our exclusion criteria were pediatric patients (<18 years) and those without insurance data. For the survival outcomes analysis, only those with survival data were included. Patients with prior malignant neoplasms other than nonmelanoma skin cancer, patients with metastatic disease at presentation, and patients treated for palliative intent were excluded from this portion of the analysis. Data reported to the SEER database are gathered prospectively and are compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. The University of Utah Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from approval and exempt from requiring patient consent owing to the deidentified data.

Clinicopathologic data, insurance information, and survival outcomes were extracted from the database. Rates of insurance coverage were examined before and after the ACA Medicaid expansion, insurance mandate and subsidies, and opening of the health insurance marketplace to examine the outcomes of this health care policy. Factors associated with insurance types were calculated and compared. All patients between January 2007 and December 2013 were recorded as the pre-expansion group, while all patients between January 2014 and December 2014 were recorded as the postexpansion group. Rates of insurance coverage were also compared between states with the Medicaid expansion vs those without the Medicaid expansion in 2014. The primary outcome was rates of insurance coverage. The secondary outcomes were disease-specific survival and overall survival.

Statistical analysis was performed from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2014. Descriptive statistics and rates of insurance coverage were calculated. Univariate survival estimates were generated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test, and 95% CIs were generated at each time estimate. Multivariable survival analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model, using all variables approaching significance (P ≤ .20) to control for confounding covariates. Random censoring was used based on the available survival data in the SEER database. Standardized mean differences were used to calculate effect size and 95% CIs. Statistical analysis was performed using XLSTAT, version 2018.2 (Addinsoft). All P values were from 2-sided tests, and results were deemed statistically significant at P ≤ .05.

Results

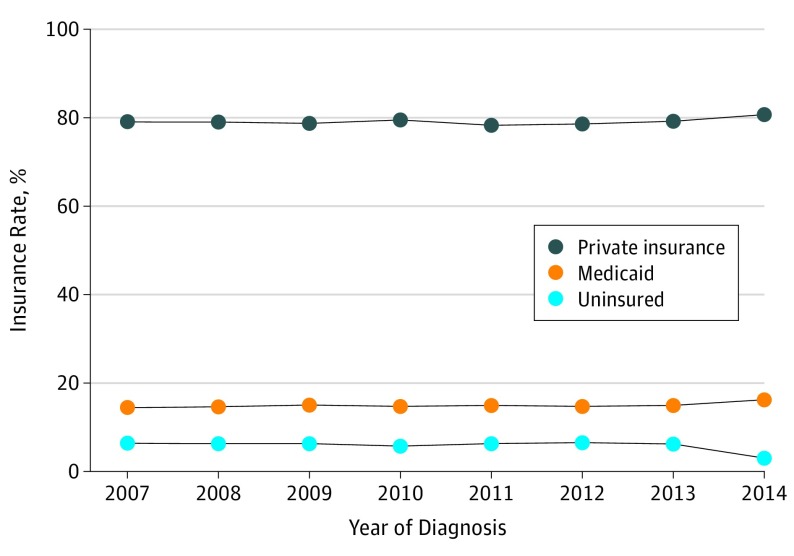

A total of 89 038 patients with newly diagnosed HNSCC met the inclusion criteria. There were 29 384 women and 59 654 men (mean [SD] age, 59.8 [7.6] years). Patient demographics and tumor characteristics of the study population and cohorts are illustrated in Table 1. After implementation of the ACA in January 2014, there was an increase in the percentages of patients enrolled in Medicaid (16.2% after vs 14.8% before; difference, 1.4%; 95% CI, 1.1%-1.7%) and private insurance (80.7% after vs 78.9% before; difference, 1.8%; 95% CI, 1.2%-2.4%) (Figure 1). There was also a large decrease in the percentages of uninsured patients after implementation of the ACA (3.0% after vs 6.2% before; difference, 3.2%; 95% CI, 2.9%-3.5%).

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients Before and After Implementation of the ACA.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of Patients (N = 89 038) | |

|---|---|---|

| Prior to ACA (2007-2013) (n = 76 313) | After ACA (2014) (n = 12 725) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 59.8 (7.5) | 59.6 (7.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 51 130 (67.0) | 8524 (67.0) |

| Female | 25 183 (33.0) | 4201 (33.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 62 577 (82.0) | 10 408 (81.8) |

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 534 (0.7) | 101 (0.8) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3053 (4.0) | 496 (3.9) |

| Black | 7479 (9.8) | 1235 (9.7) |

| Unknown | 2670 (3.5) | 485 (3.8) |

| Insurance status | ||

| Insurance | 60 258 (79.0) | 10 272 (80.7) |

| Medicaid | 11 284 (14.8) | 2066 (16.2) |

| Uninsured | 4771 (6.3) | 387 (3.0) |

| Primary site of cancer | ||

| Oral cavity | 25 195 (33.0) | 4091 (32.1) |

| Oropharynx | 19 863 (26.0) | 3359 (26.4) |

| Hypopharynx | 4574 (6.0) | 774 (6.1) |

| Larynx | 16 003 (21.0) | 2685 (21.1) |

| Nasopharynx | 6099 (8.0) | 1057 (8.3) |

| Sinonasal cavity | 4579 (6.0) | 759 (6.0) |

| AJCC Stage | ||

| I | 30 625 (40.1) | 5065 (39.8) |

| II | 15 242 (20.0) | 2567 (20.2) |

| III | 6868 (9.0) | 1158 (9.1) |

| IV | 22 794 (29.9) | 3820 (30.0) |

| Unknown | 784 (1.0) | 115 (0.9) |

Abbreviations: ACA, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Figure 1. Rates of Insurance Types Before and After the Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in January 2014.

An illustration of the percentage of each insurance type by year for patients newly diagnosed with head and neck squamous cell cancer.

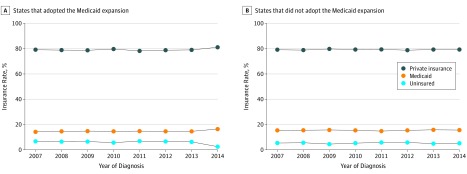

This decrease in the rate of uninsured patients and the associated increases in the rates of Medicaid and private insurance coverage were observed only in the states that adopted the Medicaid expansion in 2014 (Figure 2). For states with the Medicaid expansion, after implementation of the ACA, there was an increase in the percentages of patients enrolled in Medicaid (16.4% after vs 14.6% before; difference, 1.8%; 95% CI, 1.3%-2.3%) and private insurance (81.1% after vs 78.9% before; difference, 2.2%; 95% CI, 1.6%-3.0%) and a large decrease in the percentage of uninsured patients (2.5% after vs 6.5% before; difference, 4.0%; 95% CI, 3.4%-4.6%). For states that did not adopt the Medicaid expansion, after implementation of the ACA, there was no change in the percentage of patients enrolled in Medicaid (15.6% after vs 15.5% before; difference, 0.1%; 95% CI, 0.06%-0.14%) or private insurance (79.3% after vs 79.2% before; difference, 0.1%; 95% CI, 0.05%-0.15%) or in the percentage of uninsured patients (5.2% after vs 5.3% before; difference, 0.1%; 95% CI, 0.04%-0.16%).

Figure 2. Rates of Insurance Types Before and After the Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in January 2014 by Adoption of the Medicaid Expansion Act.

An illustration of the percentage of each insurance type by year for patients newly diagnosed with head and neck squamous cell cancer.

From 2007 to 2013, there was also a difference in disease-specific survival and overall survival among patients with HNSCC who were insured vs those who were not insured (Table 2). The rate of 5-year overall survival was 62.5% for insured patients vs 48.5% for uninsured patients (difference, 14.0%; 95% CI, 12.8%-15.2%), and the rate of 5-year disease-specific survival was 72.2% for insured patients vs 56.6% for uninsured patients (difference, 15.6%; 95% CI, 14.0%-17.2%).

Table 2. Survival Rates Among Insured and Uninsured Patients.

| Survival | Insured Patients, % (n = 62 780) | Uninsured Patients, % (n = 3443) | Mean Difference, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival, mo | |||

| 12 | 86.0 | 77.5 | 8.5 (7.8-9.2) |

| 24 | 76.6 | 62.6 | 14.0 (12.4-15.6) |

| 36 | 70.6 | 55.2 | 15.4 (13.9-16.9 |

| 48 | 66.2 | 51.1 | 15.1 (13.8-16.4) |

| 60 | 62.5 | 48.5 | 14.0 (12.8-15.2) |

| Disease-specific survival, mo | |||

| 12 | 89.1 | 81.1 | 8.0 (7.2-8.8) |

| 24 | 81.2 | 67.6 | 13.6 (12.6-14.6) |

| 36 | 76.8 | 61.1 | 15.7 (14.2-17.2) |

| 48 | 74.1 | 58.0 | 16.1 (14.3-17.9) |

| 60 | 72.2 | 56.6 | 15.6 (14.0-17.2) |

Discussion

Expanding health care coverage helps to mitigate barriers to preventive services and alleviate the disproportionate burden among uninsured patients with cancer.16 With the creation of the ACA, there has been a substantial reduction in rates of uninsured patients and an improvement in access to health care. At a national level, this study demonstrates that individuals with HNSCC are more likely to have insurance after the implementation of the ACA. Analysis completed after the first enrollment period for the ACA determined that the percentage of uninsured people 19 to 64 years of age decreased from 20% to 15%, with an estimated 9.5 million fewer individuals being uninsured.17 When specifically examining the rate of uninsured individuals among patients with HNSCC, Lawrence et al18 estimated a 27% reduction (14% after vs 19% before) in uninsured patients at a single academic institution after implementation of the ACA.

Our results showed an even more robust outcome, with approximately a 50% reduction in uninsured patients with HNSCC after implementation. Although these results demonstrate a substantial reduction in the rate of uninsured patients among those with HNSCC, the clinical and survival outcomes of these changes in patients with HNSCC remains unclear, especially with anticipated changes in health care in the coming years.19 We also demonstrated that, prior to ACA implementation, uninsured patients with HNSCC had reduced survival outcomes. Although the long-term effects of this legislation are yet to be seen, these data are compelling, especially in settings caring for individuals with HNSCC.

Past literature has demonstrated that medical insurance is highly correlated with improved prognosis and survival among patients with HNSCC.5,6,8,20 Despite insurance status itself being protective, studies have also suggested that patients with HNSCC experience varying outcomes depending on the type of insurance, such as 2 studies that concluded that patients with HNSCC who have Medicaid coverage experienced decreased overall and cancer-specific survival compared with individuals with private insurance.6,20 Studies conducted in other fields suggest that uninsured individuals are more likely to obtain care outside of standard treatment guidelines, and specifically with regard to patients with HNSCC, they are less likely to obtain definitive treatment or obtain adjuvant therapy, such as radiotherapy.20,21 One recent study suggested that uninsured patients or those insured by government programs were also more likely to seek care at hospitals with statistically poorer survival outcomes, unlike individuals with private insurance, who are more likely to obtain care from an urban or teaching hospital.22 It remains unclear how survival among these patients has been affected by changes in insurance type with health care reform because our analysis was limited by the lack of survival data available after the ACA was enacted in 2014; however, uninsured patients with HNSCC had poorer survival outcomes from 2007 to 2013. Uninsured patients, however, represent an independent patient population and likely have other risk factors that correlate with and contribute to this outcome.

As seen with previous studies examining insurance outcomes among patients with cancer, there was an increased number of individuals who became insured among states that had increased their Medicaid eligibility. Moss et al13 determined that patients with gynecologic cancer who were living in states that did not undergo Medicaid expansion were more likely to be uninsured, live in an impoverished area, and be ethnically diverse. Similar results were found in our analysis, with the increased rates of private and Medicaid insurance seen only in states that underwent the Medicaid expansion. Currently, 32 states have undergone the Medicaid expansion; thus, there is still significant opportunity to increase access to care in the United States.23 However, there is a debate whether increasing access to medical care through Medicaid expansion could alter the quality of care provided and that legislation cannot change patient adherence. There is a disparity in access to high-quality hospitals among populations of Medicaid patients.23 Although it is difficult to assess patient participation and how it affects health outcomes, patient adherence does play an important role in several aspects of head and neck cancer care.24 Our study demonstrates a nearly equivalent increase in both private and public coverage after ACA implementation, which is consistent with published data.25 However, owing to the possible variability in cancer prognosis with insurance type, further research is necessary to determine how the ongoing fluctuations in enrollment choices with the ACA have influenced cancer outcomes.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include the observational design with retrospective data analysis using the SEER database. Several issues arise with the use of SEER data, including miscoding of data, potential for unaccounted changes in insurance status after publication of the data, and poor evaluation of the SEER insurance variable.13 However, using the SEER database allows for a large sample size, which enabled us to evaluate outcomes of more than 89 000 patients with HNSCC. Owing to the inclusion of medical insurance status in our data set, the time period was limited to years within the SEER database with these data available (2007-2014), limiting our ability to examine several years prior. Furthermore, survival data after the implementation of the ACA had yet to be released, so our study was unable to evaluate differences in mortality associated with HNSCC before and after the ACA was passed. Although a certain population of elderly patients with HNSCC may not reap survival benefits, patients affected by HNSCC at a young age may see true benefits as a result of the ACA. However, while previous studies have found that patients with private insurance have improved survival compared with those who are uninsured, there is little evidence that providing insurance alone improves survival outcomes.26 Those with no insurance and public insurance represent an independent population and likely have other risk factors that contribute to an increased risk of cancer-related mortality.26 Identifying and adjusting for these risk factors will be an important next step in evaluating the health outcomes of the ACA. The true effect of the ACA may not be seen for several years, especially for the younger generation of individuals who gained health insurance as a result of this program. Furthermore, for improved insurance status to have a true effect on cancer survival, there must also be patient compliance. Further studies that evaluate improvement of patient adherence with treatment of HNSCC will enable us to maximize the benefits of improved insurance coverage.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates a 50% decrease in the percentage of uninsured patients with HNSCC and a resultant increase in rates of both private insurance and Medicaid insurance since the implementation of the ACA. Since insurance status is closely associated with time to diagnosis, treatment, and survival outcomes, these findings are of the utmost importance. Although the association between the ACA and survival has yet to be determined, there is compelling evidence that uninsured patients with HNSCC have reduced survival outcomes; however, other risk factors likely correlate and contribute to this outcome as well.

References

- 1.Rak S, Coffin J. Affordable Care Act. J Med Pract Manage. 2013;28(5):317-319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw FE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Rein AS. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: opportunities for prevention and public health. Lancet. 2014;384(9937):75-82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60259-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sommers BD, Musco T, Finegold K, Gunja MZ, Burke A, McDowell AM. Health reform and changes in health insurance coverage in 2014. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):867-874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1406753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obama B. United States health care reform: progress to date and next steps. JAMA. 2016;316(5):525-532. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, et al. . Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(1):9-31. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwok J, Langevin SM, Argiris A, Grandis JR, Gooding WE, Taioli E. The impact of health insurance status on the survival of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(2):476-485. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohlfing ML, Mays AC, Isom S, Waltonen JD. Insurance status as a predictor of mortality in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(12):2784-2789. doi: 10.1002/lary.26713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen AY, Schrag NM, Halpern MT, Ward EM. The impact of health insurance status on stage at diagnosis of oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(2):395-402. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen AY, Schrag NM, Halpern M, Stewart A, Ward EM. Health insurance and stage at diagnosis of laryngeal cancer: does insurance type predict stage at diagnosis? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(8):784-790. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.8.784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy CT, Galloway TJ, Handorf EA, et al. . Survival impact of increasing time to treatment initiation for patients with head and neck cancer in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(2):169-178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.5906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5-29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. . Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):71-96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moss HA, Havrilesky LJ, Chino J. Insurance coverage among women diagnosed with a gynecologic malignancy before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(3):457-464. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moss HA, Havrilesky LJ, Zafar SY, Suneja G, Chino J. Trends in insurance status among patients diagnosed with cancer before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(2):e92-e102. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.027102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Head and neck cancers, version 2.2018. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- 16.Davidoff AJ, Hill SC, Bernard D, Yabroff KR. The Affordable Care Act and expanded insurance eligibility among nonelderly adult cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(9):djv181. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins SR, Rasmussen PW, Doty MM. Gaining ground: Americans’ health insurance coverage and access to care after the Affordable Care Act’s first open enrollment period. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2014;16:1-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence L, Sharma A, Heuermann M, Javadi P. Affordable Care Act impact on head and neck cancer care [published online August 30, 2017]. Head Neck Surg. doi: 10.1177/0194599817717251d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell BH, Levine PA. Could the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion affect otolaryngology–head and neck surgery? JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(9):801. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inverso G, Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Donoff RB, Chuang SK. Health insurance affects head and neck cancer treatment patterns and outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74(6):1241-1247. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hines RB, Barrett A, Twumasi-Ankrah P, et al. . Predictors of guideline treatment nonadherence and the impact on survival in patients with colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(1):51-60. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta A, Sonis ST, Schneider EB, Villa A. Impact of the insurance type of head and neck cancer patients on their hospitalization utilization patterns. Cancer. 2018;124(4):760-768. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao D, Zheng C, Jindal M, et al. . Medicaid expansion and disparity reduction in surgical cancer care at high-quality hospitals. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(1):22-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopanci Bicakli D, Ozkaya Akagunduz O, Meseri Dalak R, Esassolak M, Uslu R, Uyar M. The effects of compliance with nutritional counselling on body composition parameters in head and neck cancer patients under radiotherapy. J Nutr Metab. 2017;2017:8631945. doi: 10.1155/2017/8631945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ. Both the ‘private option’ and traditional Medicaid expansions improved access to care for low-income adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):96-105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bittoni MA, Wexler R, Spees CK, Clinton SK, Taylor CA. Lack of private health insurance is associated with higher mortality from cancer and other chronic diseases, poor diet quality, and inflammatory biomarkers in the United States. Prev Med. 2015;81:420-426. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]