Key Points

Question

Which factors are associated with development of moderate or severe depression among patients with stages II through IV head and neck malignant neoplasms?

Findings

In an ad hoc secondary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of 125 patients who received a diagnosis of new or recurrent stages II through IV head and neck epidermoid carcinoma, the factors associated with development of moderate or severe depression during treatment course were Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report baseline score and initial radiotherapy–based treatment.

Meaning

Patients with baseline depression symptoms or initial radiotherapy–based treatment may benefit from pharmacologic prophylaxis of depression during treatment of head and neck cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) experience increased risk of depression and compromised quality of life. Identifying patients with HNC at risk of depression can help establish targeted interventions.

Objective

To identify factors that may be associated with the development of moderate or severe depression during treatment of HNC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This is a retrospective, ad hoc, secondary analysis of prospectively collected data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Patients were screened at academic- and community-based tertiary care HNC centers from January 2008 to December 2011. Of the 125 evaluable patients with stages II through IV HNC but without baseline depression, 60 were randomized to prophylactic antidepressant escitalopram oxalate and 65 to placebo at the time of the initial diagnosis. Data analyses were conducted from May 2016 to April 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Depression outcomes were measured using Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report (QIDS-SR) scores (range, 0-27 with a score of 11 or higher indicative of moderate or greater depression). Factors that may be associated with development of moderate or severe depression were assessed, including patient demographics; cancer site and stage; primary treatment modality (surgery or radiotherapy); history of depression or other psychiatric diagnosis; previous treatment of depression or suicide attempt, family history of depression, suicide, or suicide attempt; and baseline score on the QIDS-SR and clinician-rated QIDS instruments. Participants were stratified by study site, sex, cancer stage (early [stage II] vs advanced [stage III or IV]), primary modality of treatment (radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy vs surgery with or without radiotherapy), and randomization to placebo or escitalopram and balanced within these strata.

Results

The mean (SD) age of the 148 patients in the study population was 63.0 (11.9) years; 118 (79.7%) were men, and 143 (96.6%) were white. In the evaluable population of 125 patients, receiver operating characteristic analyses assessing the area under the curve for baseline QIDS-SR score (0.816; 95% CI, 0.696-0.935) and for initial radiotherapy-based treatment (0.681, 95% CI, 0.552-0.811) suggested that these 2 variables were associated with the likelihood of developing moderate or greater depression during the study period among patients who did not receive prophylactic antidepressants. The diagnostic sensitivity for identifying patients at risk of depression using the baseline QIDS-SR score improved to 100% at a threshold of 2 from 94% at a threshold of 4.

Conclusions and Relevance

Baseline symptoms and initial radiotherapy-based treatment may be associated with development of moderate or greater depression in patients with HNC. Patients with QIDS-SR baseline scores of 2 or higher may benefit the most from pharmacologic prophylaxis of depression.

This ad hoc secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial of patients with new or recurrent stages II through IV head and neck epidermoid carcinoma assesses the factors that may be associated with the development of moderate or severe depression during treatment.

Introduction

Depression has been reported to be one of the most common adverse effects associated with the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Studies indicate that as many as 49% of patients with cancer meet the diagnostic criteria for some form of depression.1 Clinical depression or depressive symptoms can present a number of challenges throughout cancer treatment and recovery for both clinicians and patients.2,3,4 However, because concerns are often focused on the physical needs of the patients and because the treating physicians are often ill equipped to recognize and manage depression, depression is often underrecognized in oncology populations.5

Head and neck cancers (HNCs) are among the most challenging cancers in terms of their effects on survivors.6 Treatment of these cancers can be extremely invasive and can cause long-term adverse effects, functional deficits, and permanent disfigurement.7 Major depression can be a serious consequence of HNC and its treatment.8 Patients who develop depression are less likely to complete treatment, leading to subsequent increased mortality.9,10 Furthermore, patients with HNC who develop depression during HNC treatment have been shown to have poorer quality of life following treatment.4 Therefore, preventing depression in patients with HNC represents an enormous opportunity to effect the overall course of the disease and improve the quality of life of patients.

We have previously reported our results of a randomized clinical trial aimed at examining whether depression could be prevented in patients with HNC undergoing primary curative therapy.11 The purpose of that study, the Prevention of Depression in Patients Being Treated for Head and Neck Cancer Trial (PROTECT), was to investigate the effect of prophylactic administration of the antidepressant escitalopram oxalate on the prevention of major depression in patients who were diagnosed as having HNC, who were not diagnosed as having depression at baseline, and who were about to begin cancer treatment.11 The trial showed that compared with patients receiving placebo, patients randomized to escitalopram had a greater than 50% lower incidence of depression. Although the findings from PROTECT suggested a strategy of prophylactic antidepressant use for all patients with HNC and without depression prior to starting cancer treatment, those results also prompted an examination of whether other factors may be identified at treatment initiation that may enable more targeted interventions in the future. The objective of the present ad hoc study was to examine the baseline characteristics of the PROTECT population to identify potential factors associated with moderate or greater depression in real-world patients with HNC but without baseline depression.

Methods

Study Design and Intervention

The detailed methods used in PROTECT have been previously published,11 the full trial protocol is provided in Supplement 1, and a brief summary is provided herein. For PROTECT, we conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of escitalopram treatment among patients without depression who were about to undergo treatment of HNC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00536172). Participants were eligible if they were older than 18 years with new or recurrent stages II through IV epidermoid carcinoma of the head and neck. Exclusion criteria were cognitive impairment, systemic metastatic cancer, other conditions that limited life expectancy to 6 months or less, psychosis, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, current treatment of anxiety or depression, persistent inability to communicate, uncontrolled pain, current participation in another research study receiving therapy, or women who were pregnant, nursing, or not practicing reliable birth control. The study was conducted at an academic medical center and a community cancer center, with institutional review board approval from the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Nebraska Methodist Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants were stratified by study site, sex, cancer stage (early [stage II] vs advanced [stage III or IV]), primary modality of treatment (radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy vs surgery with or without radiotherapy), and randomization to placebo or escitalopram and balanced within these strata. The trial design sought to maximize safety in this population, which has an elevated risk of suicide. Thus, participants exited the study at the first instance they met the primary end point of moderate depression on a self-rated measure. Participants were also withdrawn if they reported suicidal ideation or intent or had a diagnosis of major depression as assessed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview depression module.

All patients received standard clinical psychosocial interventions throughout the study as well as education and counseling from physicians and nurses as needed. Per the standard practice of the clinic, participants were offered the opportunity to join a monthly support group but did not receive formal psychotherapy.

Measurement Tools

The primary assessment measure was the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report (QIDS-SR). Given the difficulties with verbal communication that some of the patients experienced, this self-administered measure was chosen to minimize the burden to participants. The QIDS-SR was administered at baseline and subsequent weeks. A QIDS-SR score of 11 or higher was indicative of moderate or greater depression. The clinician-rated version of the QIDS was also given at each rating period. At baseline, participants were screened for psychiatric illness using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

Choice of Variables

Variables to investigate were selected based on those previously reported in the literature. These variables included patient age at diagnosis, sex, educational level, place of residence (urban or rural), tumor site, stage of cancer, primary treatment modality (surgery or radiotherapy), history of depression or other psychiatric diagnosis, previous treatment of depression or suicide attempt, family history of depression, suicide, or suicide attempt, and baseline number of symptoms reported on the QIDS-SR and clinician-rated QIDS.8,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed data from the baseline visit to determine whether any of the variables were associated with development of moderate or greater depression (primary end point of the study). Because the patient group receiving placebo most closely represented the real-world scenario of patients newly diagnosed as having HNC who have no baseline depression and who are not receiving prophylaxis against development of depression, data for the placebo group were specifically evaluated to determine the cutoff values for the baseline QIDS-SR score and other patient- and treatment-related factors associated with the primary end point. Continuous variables were analyzed using paired t tests, and categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher exact tests or 2-tailed χ2 tests. Multivariable receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to identify the optimum cutoff points for the development of depression. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant, and odds ratios are presented with exact 95% CIs. Data analyses were conducted from May 2016 to April 2017 using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Patients were screened from January 2008 to December 2011, with 160 agreeing to participate. Twelve of those potential participants did not meet the eligibility criteria; thus, 148 patients were randomized, 74 each to the escitalopram and placebo arms. Table 1 summarizes the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population.

Table 1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63.0 (11.9) |

| Male sex | 118 (79.7) |

| White race | 143 (96.6) |

| Smoker at baseline | 34 (23.0) |

| Study site | |

| UNMC | 68 (45.9) |

| NMH | 80 (54.1) |

| Prognostic stage (clinical) | |

| II | 35 (23.6) |

| III or IV | 113 (76.4) |

| Initial treatment | |

| Surgery (not biopsy) | 81 (54.7) |

| Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy | 67 (45.3) |

| Cancer site | |

| Pharynx | 49 (33.1) |

| Oral | 65 (43.9) |

| Other | 34 (23.0) |

| Intervention | |

| Escitalopram oxalate | 74 (50.0) |

| Placebo | 74 (50.0) |

Abbreviations: NMH, Nebraska Methodist Hospital; UNMC, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Of the 148 randomized patients, 125 were evaluable, with 60 patients receiving prophylactic escitalopram and the remaining 65 receiving placebo. Twenty-two patients developed moderate or severe depression during the course of the study (16 in the placebo group and 6 in the escitalopram group). The results of our previous analyses11 indicated those patients with HNC who received radiotherapy as their initial therapy were significantly more likely to develop depression than patients who were surgically treated (radiotherapy group compared with surgery group hazard ratio, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.38-9.40).

The eTable in Supplement 2 gives the bivariate analysis results of selected clinical and demographic variables by the primary depression end point for all patients included in the study, irrespective of treatment arm. The only baseline patient variable that was shown to be associated with the outcome of development of moderate or severe depression was the QIDS-SR score at baseline. The mean baseline QIDS-SR scores of those who developed moderate or greater depression during the study period were significantly higher than the baseline scores of those individuals who did not develop depression during the study period (6.2 vs 4.2, respectively [difference, 2.0; 95% CI for difference, 0.9-3.0]).

The eFigure in Supplement 2 shows the side-by-side boxplot of the baseline QIDS-SR scores by depression outcome (independent of treatment arm) during the study period. In total, 7 of the 125 participants (approximately 6%) had a score of 0 or 1 on the QIDS-SR at baseline and were in the group of patients who did not develop moderate or greater depression during the course of the study. The baseline QIDS-SR scores ranged from 0 to 9 for individuals who did not develop depression and from 2 to 10 for individuals who developed moderate or greater depression during the study period. The eFigure in Supplement 2 shows that baseline scores for patients who developed moderate or greater depression were higher than those for patients who were free of depression during follow-up. Furthermore, no one who developed the depression outcome of interest had a baseline score of less than 2 at the time of treatment initiation, and 20 of 22 (90.9%) patients who developed depression in the entire study cohort had a baseline QIDS-SR score of 4 or greater.

Other factors that were not associated with the subsequent development of moderate or greater depression included patient age, sex, rural vs urban residence, educational level, clinical stage, cancer site, having a family or personal history of depression, and having a history of suicide attempt or psychiatric illness.

We performed additional analyses to consider clinical factors that may be significant specifically in the placebo group. Table 2 gives the bivariate analysis results of selected clinical and demographic variables by the primary end point among patients receiving no prophylactic intervention for prevention of depression.

Table 2. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics by Depression Status for Patients in the Placebo Group.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | Difference, OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Never Depressed (n = 49) | Depressed (n = 16) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 60.9 (12.2) | 62.8 (10.9) | −1.9 (−8.8 to 5.0) |

| QIDS-SR at baseline, mean (SD) | 4.0 (1.8) | 6.5 (2.0) | −2.5 (−3.7 to −1.3) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 40 (82) | 13 (81) | 1.03 (0.16-4.99) |

| Female | 9 (18) | 3 (19) | |

| Urban residence | |||

| Yes | 35 (71) | 9 (56) | 0.51 (0.14-1.99) |

| No | 14 (29) | 7 (44) | |

| College education (any) | |||

| Yes | 24 (49) | 10 (62) | 1.74 (0.48-6.73) |

| No | 25 (51) | 6 (38) | |

| Clinical stage | |||

| II | 12 (24) | 3 (19) | 1.41 (0.31-8.93) |

| III or IV | 37 (76) | 13 (81) | |

| Initial treatment | |||

| Surgery (not biopsy) | 30 (61) | 4 (25) | 4.74 (1.33-16.85) |

| Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy | 19 (39) | 12 (75) | |

| Site | |||

| Pharynx | 14 (29) | 6 (38) | 1 [Reference] |

| Oral | 24 (49) | 9 (56) | 0.88 (0.22-3.68) |

| Other | 11 (22) | 1 (6) | 0.21 (0.00-2.26) |

| Family history of depression | |||

| Yes | 6 (12) | 4 (25) | 0.42 (0.08-2.39) |

| No | 43 (88) | 12 (75) | |

| Personal history of depression | |||

| Yes | 5 (10) | 2 (12) | 0.80 (0.11-9.26) |

| No | 44 (90) | 14 (88) | |

| History of suicide attempt | |||

| Yes | 3 (6) | 0 | NA |

| No | 46 (94) | 16 (100) | |

| History of psychiatric illness | |||

| Yes | 3 (6) | 0 | NA |

| No | 46 (94) | 16 (100) | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report.

In the placebo group, development of moderate or severe depression was associated with type of initial treatment (primary radiotherapy) and QIDS-SR score at baseline. In this group, 12 of 31 patients (39%) who received radiation as part of their initial course of treatment developed depression during the study period compared with only 4 of 34 patients (12%) who did not receive radiotherapy as part of their initial treatment strategy (odds ratio, 4.74; CI, 1.33-16.85). In addition, mean baseline QIDS-SR scores for patients who received placebo and developed moderate or greater depression during the study period were significantly higher than the baseline scores of those individuals who did not develop depression during the study period (6.5 vs 4.0, respectively; difference, 2.5; CI for the difference, 1.3-3.7).

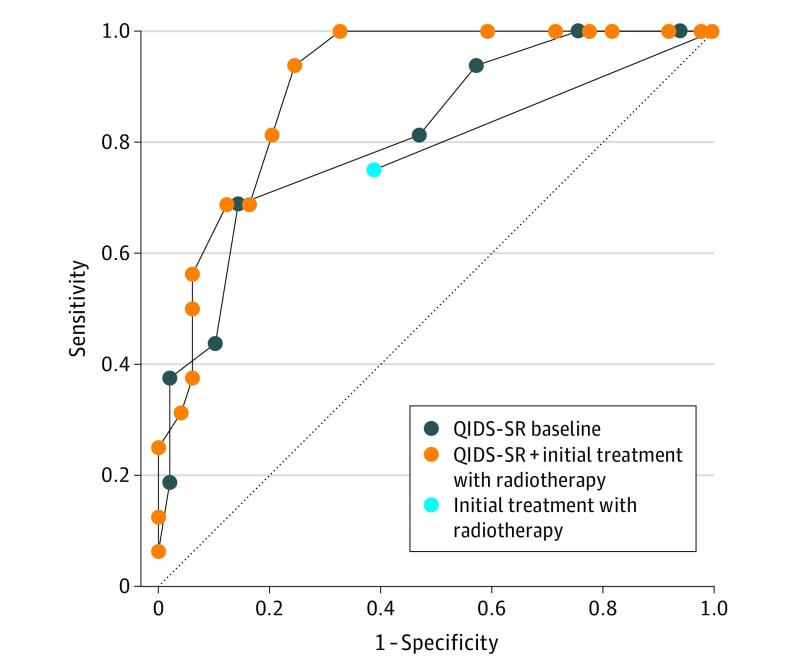

On the basis of the bivariate analysis results, multivariable ROC analyses were conducted using baseline QIDS-SR score and initial treatment as factors in the placebo group. The results of the multivariable ROC analyses for the placebo group are shown in the Figure and Table 3.

Figure. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves for the Placebo Group.

QIDS-SR indicates Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report.

Table 3. Multivariable Receiver Operating Characteristic Analysis for Patients in the Placebo Group.

| Model | AUC | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| QIDS-SR baseline | 0.816 | 0.696-0.935 |

| Initial treatment with radiotherapy | 0.681 | 0.552-0.811 |

| QIDS-SR plus initial treatment with radiotherapy | 0.904 | 0.833-0.975 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report.

For the placebo group, the area under the curve (AUC) for the model that included both variables (0.904) had significantly better fit than models with either baseline QIDS-SR scores (AUC, 0.816; 95% CI, 0.696-0.935) or initial treatment selection (AUC, 0.681; 95% CI, 0.552-0.811) alone.

The suggested cutoff values are the model-determined probability values that minimize the distance between the ROC curve and point (0, 1), maximize the vertical distance between the ROC curve and the diagonal reference line, or both. Using the optimal cutoff for the combined model produced a sensitivity of 0.938 with a specificity of 0.755 in the placebo group (Table 4).

Table 4. Probability Cutpoints, Sensitivity, and Specificity for Patients in the Placebo Group.

| Model | Probability of Developing Depression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cutpoint | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| QIDS-SR baseline | ≥0.356 | 0.688 | 0.857 |

| Initial treatment with radiotherapy | ≥0.387 | 0.750 | 0.612 |

| QIDS-SR plus initial treatment with radiotherapy | ≥0.145 | 0.938 | 0.755 |

Abbreviation: QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report.

For the placebo group, using the QIDS-SR score as a factor associated with developing moderate or severe depression, we found that a score threshold of 6 provided a sensitivity of 0.69 and a specificity of 0.86. When a score threshold of 4 was used, the sensitivity was 0.94 and the specificity was 0.43. A score threshold of 2 improved the sensitivity to 1.00, with an expected decrease in specificity.

Discussion

The risks of failing to treat depression in HNC are stark and multiple: decreased compliance with treatment,9 decreased quality of life,13 and increased mortality.23 In addition, HNC is associated with a higher risk of suicide compared with most other cancer sites and compared with the general population.24 In our previously published trial reports,11,25 we showed that prophylactic use of escitalopram could reduce the number of patients who met the predetermined criteria for moderate or severe depression. As with all prevention strategies, the goal is to minimize the number of people who are exposed to the risk of the drug while maximizing the number who benefit. Although our previous study provides an important finding, prophylactic treatment of all patients who are starting treatment of HNC will mean unnecessary administration of the drug to some patients who may not develop depression. The number needed to treat was 6.8 when using a strategy based on offering pharmacologic prophylaxis against depression to all patients planning to initiate therapy of stages II through IV epidermoid carcinoma of the head and neck region. Therefore, in the present analysis, we examined available baseline measures that might enable us to home in on participants at increased risk thus potentially allow some targeting for this intervention.

For the placebo group, baseline QIDS-SR scores and choice of initial treatment (primary radiotherapy) showed statistically significant associations with the predefined end point of development of moderate or severe depression. This finding is consistent with previous research showing a significant positive association with depressive symptoms at study onset.26,27 Furthermore, development of depression may be linked to the choice of initial therapy, and patients who receive initial radiation–based therapy may be particularly vulnerable.11,28 These patient- and treatment-related factors should alert the clinician to the potential development of depression and encourage discussion and shared decision making of management strategies, including the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis against depression. Of note, despite prophylactic therapy, some patients still progressed to develop clinically relevant depression. It is important that clinicians maintain continued surveillance for signs and symptoms of depression even among those patients who choose to receive pharmacologic prophylaxis at the outset.

An important secondary finding of PROTECT was the sustained improvement in quality of life among participants who did not develop depression for up to 3 months after cessation of treatment with the drug.11 Withholding antidepressant treatment may result in loss of these quality-of-life benefits in a patient population that is at significant risk for decline in well-being. It is our hypothesis that a type of posttraumatic stress reaction may have developed in the group of patients who did not receive prophylactic antidepressant treatment, particularly in the radiotherapy arm, and that this reaction may be mitigated, at least in part, by prophylactic administration of escitalopram. The implications of limiting access to prophylactic escitalopram among patients with a low QIDS-SR score, and therefore the loss of this potential advantage, must be considered when using any baseline score threshold as a measure of when to offer prophylactic escitalopram to patients with HNC. Because of the favorable safety profile and low incidence of adverse effects of escitalopram in the study population,11 setting the cutoff at a very low number affords more patients this potential benefit while minimizing treatment-associated harm.

Although the present study showed that the baseline QIDS-SR score and initial treatment with radiotherapy were significantly associated with depression in the placebo group, we did not find support for other measures that have previously been reported to be associated with increased risk of developing moderate or greater depression, such as having a personal history of major depression or its treatment,22 a history of other psychiatric illness,16 a family history of major depression,22 age,8 sex,27 educational level,15,16,17 and stage of cancer.17

Other variables not examined in the present study have also been shown to be associated with the development of depression in this patient population. A study by De Leeuw et al29 examined the association of social support via social networks with depression among 197 patients with HNC. The extent of their social network was measured with 2 questions about the number of individuals in their professional and informal network (partner, family, and friends). The results of that study found that higher levels of support were associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Karnell and colleagues30 also prospectively examined the role of social support as a risk factor of developing depression among patients with HNC. They studied 394 patients and found that ratings of perceived posttreatment social support at diagnosis were significantly associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Other studies have found that factors, including patients’ coping style, overall health and physical functioning, openness of the family to discussing cancer, and size of the informal social network, may also be associated with the development of depression among patients with HNC.26,27 In addition, the medical comorbidities of patients with cancer or other chronic disease have been shown to be associated with the development of depression, especially among elderly patients.31,32 Because one of the goals in designing PROTECT was to minimize the burden of participation for patients, we limited the number of measures that we asked participants to complete. Therefore, we were unable to directly compare the importance of social support strength and other factors as potential factors.

Limitations

Other limitations of our study include a relatively small number of participants at 1 academic center and 1 community hospital and a study design that did not collect patient data on participants after they met the depression study end point, which allowed these patients to exit the study and receive specific care for depression as medically necessary. Although not statistically significant, a higher proportion of patients in the placebo group who became depressed were nonurban residents, had some college education, received a diagnosis at a later stage, had a diagnosis of oral cancer, and had a family or personal history of depression. The present study was likely underpowered to determine whether any of these differences may have been important. Although we cannot definitively conclude whether these baseline characteristics may be associated with developing depression, this information can provide guidance for characteristics that should be considered for future study. In addition, the relatively small sample size and small proportion of patients who developed depression limited the present study to primarily univariate analyses. A more extensive multivariable analysis could help identify whether specific combinations of baseline characteristics are associated with the development of depression. This should be investigated further in future studies.

Conclusions

The present study found that, among patients who received a diagnosis of HNC, baseline depressive symptoms (as measured by the QIDS-SR score) and use of radiotherapy as a primary therapeutic modality were associated with an increased likelihood of developing moderate or severe depression during cancer treatment. These associations are clinically meaningful because they permit clinicians to better recognize at-risk patients. Moreover, these results may inform patients, their caregivers, and health care professionals when considering the risk of clinically relevant depression during treatment of HNC, the contribution of depression to survivorship experience and quality of life, and the potential strategies for prevention and mitigation of depression.

Prophylactic antidepressant treatment should be strongly considered for patients who meet a threshold score of 4 on the QIDS-SR and for those who are expected to receive radiotherapy as part of their initial cancer therapy. This strategy, which attempts risk prediction, may help identify patients who may derive the most benefit from pharmacologic prophylaxis of depression. It should augment clinical discussion and decision making for clinicians who may prefer more specificity when selecting patients with HNC for administration of prophylactic antidepressants. However, this threshold may lead to a missed treatment opportunity for up to 9% of patients with HNC at risk of developing depression.

Because of the potential for profound effects of untreated depression in this patient population, it is reasonable to err on the side of sensitivity rather than specificity. By this argument, lowering the threshold for offering prophylactic antidepressant treatment to a QIDS-SR score of 2 further reduces the risk of untreated depression in patients with HNC.

Although a strategy of universal prophylaxis in the PROTECT population led to a number needed to treat of 6.8, the more selective strategy of using the low QIDS-SR score of 2 as a threshold slightly decreased the number needed to treat to 6.6. Overall, irrespective of treatment strategy, the use of prophylactic antidepressants in the present study population resulted in a relatively low number of individuals being unnecessarily treated.

Depression can substantially affect the safety and well-being of patients with HNC. Clinicians may recognize that antidepressant use for these patients, in addition to mitigating depression, may contribute to sustained improvement in quality of life.11

Prophylactic escitalopram administration should be considered for all patients who receive a diagnosis of HNC as part of their multidisciplinary care, but its use should be more strongly considered for patients who show depressive symptoms at baseline and for those expected to receive radiotherapy as their initial cancer treatment. Future research using larger sample sizes and multisite studies should continue to try to identify other clinical and social factors that may be predictive of depression.

Trial Protocol

eTable. Bivariate Analysis of Clinical and Demographic Variables by Depression Endpoint (Overall Patient Cohort Irrespective of Use of Escitalopram or Placebo)

eFigure. Boxplot of QIDS-SR at Baseline (for All Patients Included in the Study)

References

- 1.Walker J, Holm Hansen C, Martin P, et al. . Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):895-900. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couper JW, Pollard AC, Clifton DA. Depression and cancer. Med J Aust. 2013;199(6)(suppl):S13-S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paula JM, Sonobe HM, Nicolussi AC, Zago MM, Sawada NO. Symptoms of depression in patients with cancer of the head and neck undergoing radiotherapy treatment: a prospective study. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2012;20(2):362-368. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692012000200020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammerlid E, Silander E, Hörnestam L, Sullivan M. Health-related quality of life three years after diagnosis of head and neck cancer—a longitudinal study. Head Neck. 2001;23(2):113-125. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4488-4496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner J, Yates P, Kenny L, et al. . The ENHANCES study—Enhancing Head and Neck Cancer Patients’ Experiences of Survivorship: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):191. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, et al. . Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333(6046):1154-1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haisfield-Wolfe ME, McGuire DB, Soeken K, Geiger-Brown J, De Forge BR. Prevalence and correlates of depression among patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review of implications for research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(3):E107-E125. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E107-E125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(11):1797-1810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lydiatt WM, Bessette D, Schmid KK, Sayles H, Burke WJ. Prevention of depression with escitalopram in patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(7):678-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Robbins KT, et al. . Physical activity and quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(10):1012-1019. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0044-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy SA, Ronis DL, Valenstein M, et al. . Depressive symptoms, smoking, drinking, and quality of life among head and neck cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):142-148. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.2.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz MR, Irish JC, Devins GM, Rodin GM, Gullane PJ. Psychosocial adjustment in head and neck cancer: the impact of disfigurement, gender and social support. Head Neck. 2003;25(2):103-112. doi: 10.1002/hed.10174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sehlen S, Lenk M, Herschbach P, et al. . Depressive symptoms during and after radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2003;25(12):1004-1018. doi: 10.1002/hed.10336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandey M, Devi N, Thomas BC, Kumar SV, Krishnan R, Ramdas K. Distress overlaps with anxiety and depression in patients with head and neck cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16(6):582-586. doi: 10.1002/pon.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kugaya A, Akechi T, Okuyama T, et al. . Prevalence, predictive factors, and screening for psychologic distress in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2000;88(12):2817-2823. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burris JL, Andrykowski M. Disparities in mental health between rural and nonrural cancer survivors: a preliminary study. Psychooncology. 2010;19(6):637-645. doi: 10.1002/pon.1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen AM, Daly ME, Vazquez E, et al. . Depression among long-term survivors of head and neck cancer treated with radiation therapy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(9):885-889. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miovic M, Block S. Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1665-1676. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snyderman D, Wynn D. Depression in cancer patients. Prim Care. 2009;36(4):703-719. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins C, Carmody TJ, Rush AJ. Depression in radiation oncology patients: a preliminary evaluation. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(1):17-21. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00039-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazure KE, Lydiatt WM, Denman D, Burke WJ. Association between depression and survival or disease recurrence in patients with head and neck cancer enrolled in a depression prevention trial. Head Neck. 2009;31(7):888-892. doi: 10.1002/hed.21046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR, Redman M, Yueh B. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4731-4738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lydiatt WM, Denman D, McNeilly DP, Puumula SE, Burke WJ. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of citalopram for the prevention of major depression during treatment for head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134(5):528-535. doi: 10.1001/archotol.134.5.528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Leeuw JRJ, de Graeff A, Ros WJG, Blijham GH, Hordijk GJ, Winnubst JAM. Prediction of depressive symptomatology after treatment of head and neck cancer: the influence of pre-treatment physical and depressive symptoms, coping, and social support. Head Neck. 2000;22(8):799-807. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Leeuw JRJ, de Graeff A, Ros WJG, Blijham GH, Hordijk GJ, Winnubst JAM. Prediction of depression 6 months to 3 years after treatment of head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2001;23(10):892-898. doi: 10.1002/hed.1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kam D, Salib A, Gorgy G, et al. . Incidence of suicide in patients with head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(12):1075-1081. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.2480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Leeuw JRJ, De Graeff A, Ros WJG, Hordijk GJ, Blijham GH, Winnubst JAM. Negative and positive influences of social support on depression in patients with head and neck cancer: a prospective study. Psychooncology. 2000;9(1):20-28. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karnell LH, Christensen AJ, Rosenthal EL, Magnuson JS, Funk GF. Influence of social support on health-related quality of life outcomes in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2007;29(2):143-146. doi: 10.1002/hed.20501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):216-226. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00273-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishnan KRR, Delong M, Kraemer H, et al. . Comorbidity of depression with other medical diseases in the elderly. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(6):559-588. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01472-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable. Bivariate Analysis of Clinical and Demographic Variables by Depression Endpoint (Overall Patient Cohort Irrespective of Use of Escitalopram or Placebo)

eFigure. Boxplot of QIDS-SR at Baseline (for All Patients Included in the Study)