This crossover study of primary care physicians evaluates whether the use of medical scribes in primary care improves physician productivity and patient satisfaction.

Key Points

Question

Can the use of medical scribes decrease electronic health record documentation burden, improve productivity and patient communication, and enhance job satisfaction among primary care physicians?

Findings

In this crossover study of 18 primary care physicians, use of scribes was associated with significant reductions in electronic health record documentation time and significant improvements in productivity and job satisfaction.

Meaning

Use of medical scribes to reduce the increasing electronic health record documentation burden faced by primary care physicians could potentially reduce physician burnout.

Abstract

Importance

Widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) in medical care has resulted in increased physician documentation workload and decreased interaction with patients. Despite the increasing use of medical scribes for EHR documentation assistance, few methodologically rigorous studies have examined the use of medical scribes in primary care.

Objective

To evaluate the association of use of medical scribes with primary care physician (PCP) workflow and patient experience.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This 12-month crossover study with 2 sequences and 4 periods was conducted from July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017, in 2 medical center facilities within an integrated health care system and included 18 of 24 eligible PCPs.

Interventions

The PCPs were randomly assigned to start the first 3-month period with or without scribes and then alternated exposure status every 3 months for 1 year, thereby serving as their own controls. The PCPs completed a 6-question survey at the end of each study period. Patients of participating PCPs were surveyed after scribed clinic visits.

Main Outcomes and Measures

PCP-reported perceptions of documentation burden and visit interactions, objective measures of time spent on EHR activity and required for closing encounters, and patient-reported perceptions of visit quality.

Results

Of the 18 participating PCPs, 10 were women, 12 were internal medicine physicians, and 6 were family practice physicians. The PCPs graduated from medical school a mean (SD) of 13.7 (6.5) years before the study start date. Compared with nonscribed periods, scribed periods were associated with less self-reported after-hours EHR documentation (<1 hour daily during week: adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 18.0 [95% CI, 4.7-69.0]; <1 hour daily during weekend: aOR, 8.7; 95% CI, 2.7-28.7). Scribed periods were also associated with higher likelihood of PCP-reported spending more than 75% of the visit interacting with the patient (aOR, 295.0; 95% CI, 19.7 to >900) and less than 25% of the visit on a computer (aOR, 31.5; 95% CI, 7.3-136.4). Encounter documentation was more likely to be completed by the end of the next business day during scribed periods (aOR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.2-7.1). A total of 450 of 735 patients (61.2%) reported that scribes had a positive bearing on their visits; only 2.4% reported a negative bearing.

Conclusions and Relevance

Medical scribes were associated with decreased physician EHR documentation burden, improved work efficiency, and improved visit interactions. Our results support the use of medical scribes as one strategy for improving physician workflow and visit quality in primary care.

Introduction

The transition from paper-based to electronic health records (EHRs) ushered in a new era of health care delivery. Financial incentives for EHR adoption and meaningful use provided the impetus for EHR implementation in the United States,1 resulting in adoption rates of 99% in hospitals2 and 70% among office-based physicians as of 2016.3 Although EHRs modestly improve quality, enhance patient safety, and reduce costs,4,5,6,7 they also impose added demands on a physician’s time. Emerging evidence indicates that EHRs, as currently implemented, increase clerical workload and physician stress and interfere with direct physician-patient interaction, thereby diminishing professional satisfaction and contributing to professional burnout.8,9,10

Physician burnout induced by work-related stress leads to emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment.11,12 One in every 2 physicians experience symptoms of burnout, with primary care physicians (PCPs) experiencing the highest rates.12 Between 2011 and 2014, burnout prevalence among physicians increased from 46% to 54%.13 A major contributor to physician burnout is the burden of EHR-created documentation.8,14 For every hour of direct patient care, physicians spend nearly 2 additional hours on unpaid EHR and desk work.15 Among PCPs, introduction of additional EHR features has been associated with even higher rates of burnout, stress, and desire to leave practice.14

Use of medical scribes, paraprofessionals who transcribe clinical visit information into the EHRs in real time under physician supervision, has been proposed as one strategy to alleviate documentation burden and improve physician efficiency. Recent estimates indicate that there are approximately 20 000 scribes currently working with physicians, with the number expected to reach 100 000 by 2020.16,17 However, despite the rapid increase in the number of scribes, evidence of their association with PCP job satisfaction and productivity is lacking, especially among PCPs at the frontline of care. Existing small-scale studies18,19,20,21 suggest that scribes may improve physician productivity, professional satisfaction, and patient-physician interaction. However, methodologic limitations of these initial studies underscore the need for a more rigorous approach to assess the use of scribes in primary care.18,21,22,23 Using a 12-month multiple crossover design, we tested the hypothesis that medical scribe use in primary care would reduce physician documentation burden and improve clinical workflow, physician work satisfaction, and patient-physician visit interactions.

Methods

Setting and Study Population

We conducted this study from July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017, in 2 medical center facilities in Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC). KPNC is an integrated health care delivery system that provides comprehensive care to 4.2 million patients in Northern California. The demographic and socioeconomic composition of patients in the KPNC system is representative of the area population except at the extremes of income distribution.24 This quality improvement study was reviewed and approved by the Kaiser Permanente Research Determination Board and deemed exempt from review by the Kaiser Permanente Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was not required; patient data were collected without identifiers other than the patient’s PCP name.

Of the 24 eligible PCPs at the 2 practices, 18 (75%) agreed to participate. The 6 PCPs who declined cited reluctance to train a scribe in the particulars of their workflow, concern about having to review scribed notes, and unwillingness to have a third person in the examination room with them. None of the eligible PCPs had any prior experience working with scribes. Before the study, the PCPs completed EHR documentation independently, simultaneously while evaluating patients, at the end of the day, or after clinic hours and on weekends. Scribes were trained by and contracted through an independent scribe company. Scribes logged into the EHR using their own log-in credentials and documented clinical visit notes in real time. The PCPs assessed the notes for accuracy before signing them.

Study Design

We used a dual-balanced crossover design with 4 periods, 2 sequences, and 2 treatments. We assume that the carryover effect from each period is negligible. Each period lasted 3 months. The PCPs were randomly assigned to begin the first period with a scribe (treatment A) or without a scribe (treatment B). The use of a scribe was then alternated in each subsequent period for 1 year, thus creating ABAB or BABA treatment sequences. By contrasting the same PCP in different treatment periods, this study design allowed PCPs to serve as their own matched controls, thereby reducing the potential influence of between-PCP variance.

Data Collection

The PCPs completed a 4-question survey at baseline and a 6-question survey (eTable 1 in the Supplement) near the end of each of the 4 study periods. Surveys assessed the association of scribe use with the aspects of physician work that have previously been reported as worsened by EHRs: clerical burden, quality of patient-physician interaction, and job satisfaction. Clerical work that extended into personal time (nonclinic hours on weekdays and on weekends) was assessed using a 4-level ordinal scale (<1, 1 to <2, 2 to <3, and >3 hours daily). Physician perception of time spent on EHRs and on direct patient interaction during a clinical visit was measured using a 4-level ordinal scale (<25%, 25 to <50%, 50 to <75%, and >75% of visit). Physician perception of the association of scribe use with the quality of patient interactions and work satisfaction was measured using a 5-point Likert-scale, with 1 indicating much worse and 5 indicating much better. The PCPs also completed a poststudy survey to assess their satisfaction with scribe-written notes and the additional number of patients that they would be willing to accept if they received scribe assistance.

Near the end of each scribed period, a week was allocated for collecting anonymous patient satisfaction surveys that asked patients (eTable 2 in the Supplement) to compare their usual clinical visits with their PCP with the just-completed scribed visit with their PCP. Patient perception of the time spent by PCPs on direct interaction and on the computer was assessed using a 3-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating less time than usual, 2 indicating no difference, and 3 indicating more time than usual. Patient’s comparative satisfaction with the quality of visit was measured using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating much worse and 5 indicating much better.

Physician survey collection periods were designed to overlap with KPNC’s quarterly quality reporting periods. These administrative quality reports, created using EHR data, were the source of the physician’s clinical workflow data and included user activity measured using time-stamped event logs. These event log data were used to calculate the proportion of a physician’s clinic unit (1 unit = 240 minutes) spent on EHR activity: the mean number of minutes each physician spent on in-person visits and on EHR documentation during and after clinic hours. Similarly, event logs generated from office, telephone, and virtual encounters were used to calculate the time that physicians required to close encounters. KPNC PCPs are prescribed a target of closing 95% of these encounters by the end of next business day. We used achievement of target (yes/no) as a measure of the PCP’s clinical workflow efficiency.

Statistical Analysis

We used χ2 and independent 2-tailed, paired t tests to assess the significance of frequency and continuous variable differences between the scribe and nonscribe groups. We applied multilevel logistic (PROC GLIMMIX, SAS, version 9.3) and multilevel linear (PROC MIXED, SAS, version 9.3) regression models (SAS Institute Inc) to assess each outcome by treating the period and treatment effects as fixed effects and the subject effect (PCP) as the random effect. The random-effects model was chosen to account for possible heterogeneity across PCPs. The PCP responses were dichotomized to account for skewness in distribution. Responses were dichotomized to less than 1 vs 1 hour or more for documentation, less than 25% vs 25% or more for time spent on the EHR during the office visit, and less than 75% vs 75% or more for interaction.

Results

Of the 18 participating PCPs, 10 were women. Twelve PCPs were internal medicine and 6 were family practice physicians. The PCPs graduated from medical school a mean (SD) of 13.7 (6.5) years before the study start date. At baseline, 11 PCPs (61%) reported spending 1 to 2 hours daily during the week and 1 to 3 hours daily on the weekends outside scheduled clinic time on EHR documentation. Only 5 (28%) reported spending more than 75% of a typical return visit on patient interaction and less than 25% of the visit on EHR documentation.

Association of Scribe Use With PCP-Reported Experience

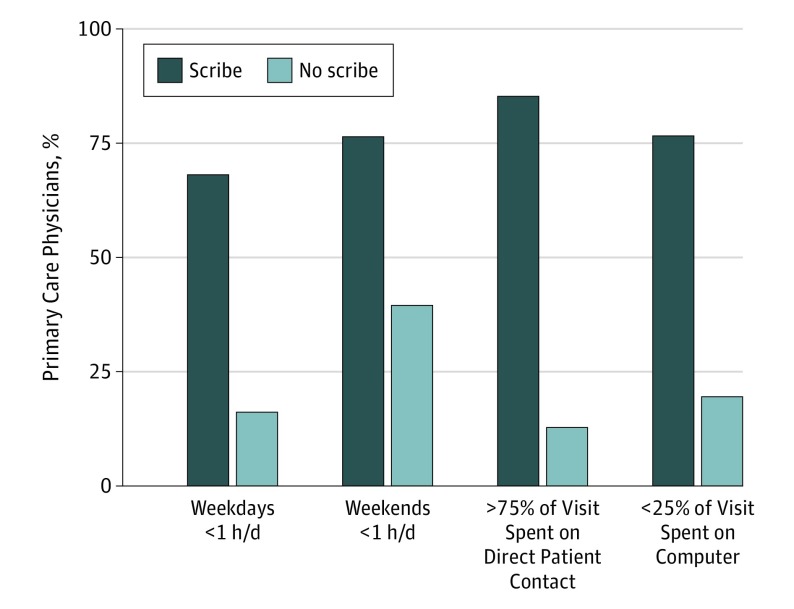

The PCPs completed 65 of 72 surveys (90% response rate) during the study period. The PCPs reported significant improvements across all outcome measures during scribe intervention periods. Compared with nonscribed periods, scribed periods were associated with decreased off-hour EHR documentation work (69% vs 17% of PCPs reported <1 hour daily on weekdays; adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 18.0 [95% CI, 4.7-69.0], P < .001; 77% vs 40% reported <1 hour daily on weekends; aOR, 8.7 [95% CI, 2.7-28.7], P < .001). Scribed periods were also associated with greater patient interaction during visits (85% vs 13% spending >75% of visit interacting with patient; aOR, 295.0; 95% CI, 19.7 to >900; P < .001) and correspondingly less time during the visit documenting in the EHR (77% vs 20% spending <25% of time on EHR; aOR, 31.5; 95% CI, 7.3-136.4; P < .001). Seventeen PCPs (94%) reported greater job satisfaction, and 16 (89%) reported improved clinical interactions when assisted by scribes. The Figure presents the PCP survey results by scribe status.

Figure. Physician Survey Results by Scribe Status.

Results are presented as the percentage of primary care physicians reporting spending less than 1 hour daily on electronic health record (EHR) documentation outside clinic hours on weekdays, spending less than 1 hour daily on EHR documentation outside clinic hours on weekends, spending more than 75% of visit time interacting directly with patient, and spending less than 25% of visit time interacting directly with the computer.

Quantitative Measures of the Association of Scribe Use With Physician Experience

Physician scheduling templates with number of available appointments per clinical session appointment schedules were not changed during the study period. As expected, scribes produced no mean (SD) change in the length of clinic visit (20.6 [3.9] vs 21.4 [4.7] minutes, P = .42). Compared with nonscribed periods, the PCPs were significantly more likely to meet their prescribed target for timely completion of their visit documentation during the scribed periods (61.7% vs 50.9% without scribe; aOR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.2-7.1; P = .02). Scribed periods were also associated with a 77-minute decrease in the time that the PCPs spent on clinical documentation per clinic unit (32% of a clinic unit); however, the decrease approximated but did not reach statistical significance (mean, −77.2 minutes; 95% CI, −172.7 to 18.3 minutes; P = .11). The PCPs also had modestly improved patient-reported satisfaction scores (69.4% above medical center mean with scribe vs 63.9% without scribe) that did not reach statistical significance (aOR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.4-5.4; P = .48). Compared with the nonscribed periods, measured time spent logged into the EHR system during off hours decreased by 17 minutes per week on each EHR; however, this reduction was not statistically significant (mean, −17.1 minutes; 95% CI, −50.2 to 16.1 minutes; P = .62). The proportion of each PCP’s clinic unit spent on EHR activity decreased in the scribed periods by 8% but did not reach statistical significance (101.3% vs 110.4% in the scribed vs nonscribed periods; 95% CI, 25.5-9.5; P = .36).

Patient-Reported Visit Quality With Use of Scribes

Surveys were received from 735 patients of the participating PCPs (37 patients per PCP; range, 9-77 patients) during scribed periods. A total of 428 patients (57.0%) reported that their PCP spent less time than usual on the computer during scribed visits, 281 (37.2%) reported no difference, and only 47 (6.2%) reported more computer use than usual. A total of 375 patients (49.8%) reported that their PCP spent more time than usual speaking with them during the scribed periods. A total of 460 patients (61.2%) reported that scribes had a positive consequence and 274 (36.4%) reported they had no consequence on the office visit, with only 18 (2.4%) reporting a negative consequence.

Poststudy PCP Survey

After completion of the study, 17 PCPs completed a brief survey about their scribe experience. All PCPs worked with at least 3 different scribes during the study, with 7 PCPs (39%) working with 4 or more. Fifteen of the 17 PCPs (88%) indicated satisfaction with the quality of scribe EHR documentation. Eleven of the 17 PCPs (65%) indicated that they would be willing to accept additional patients into their panel (100-200 additional patients by 8 PCPs and >200 additional patients by 3 PCPs) in exchange for a full-time scribe. Of the PCPs who would not be willing to expand their patient panel sizes in exchange for a scribe, 4 of 6 had an existing panel size that exceeded the practice limit.

Discussion

Burnout is an increasing problem in US medicine and is particularly intense among PCPs. The burden of EHR documentation has been posited as one of the leading contributors to this problem. In this crossover study, we evaluated the association between use of scribes for EHR documentation assistance and PCP perception of documentation burden, visit quality, and job satisfaction. Our study also leveraged extensive quantitative EHR clinical workflow data to complement PCP- and patient-reported outcomes. We found that scribe assistance resulted in significant reduction in PCP-reported EHR documentation burden outside visits and significant increase in time spent on face-to-face patient interaction during visits. These self-reported results were corroborated by objective improvement in measured time to completion of encounter documentation. Other quantitative measures (eg, time spent logged into the EHR) favored scribe use but did not reach statistical significance. Overall, most PCPs and patients consistently indicated that scribes had a positive association with their clinical visit.

Physician-perceived meaningful communication with patients is central to physician job satisfaction25; however, there is increasing evidence that EHR documentation burden is interfering with physician-patient interaction time.15 A study8 of physicians in 4 US states found that physicians spend 27% of office time on direct patient interaction and more than 49% of office time on EHRs and deskwork. Despite conceptually recognizing the benefits of EHRs, many physicians struggle to use currently implemented EHR systems, which they report has worsened their professional satisfaction and quality of patient care.8 Physicians also report that administrative tasks required by EHRs could be performed more efficiently by clerks and transcriptionists.8 Our study found that perceived patient interaction time in office visits increased significantly in the scribed periods. This result provides evidence that delegating EHR documentation to scribes may reduce EHR distraction, securing PCPs more time for patient interaction.

During periods of scribe assistance, the PCPs reported significant reductions in their EHR documentation burden during off hours, suggesting that scribes may also improve a physician’s work-life balance. These results are consistent with a prior report18 of increased patient facetime, improved clinical visit quality, and enhanced physician work satisfaction with scribe assistance. Concordant with our finding, a study26 of 5 urologists found that scribes reduced EHR documentation burden and improved satisfaction with clinic hours. Similarly, a small (4 PCPs) study18 in an academic family medicine practice reported that scribes produced significant improvements in patient facetime and clinic satisfaction and significant reductions in perceived documentation time.

Our study found that use of scribes was associated with improved physician productivity, which was measured by the likelihood of closing at least 95% of office, telephone, and virtual encounters by the targeted time. This result suggests that by removing documentation burden from PCPs, scribes created more time for PCPs to complete their EHR work. Consistent with our results, the study of 4 PCPs mentioned above also reported improved odds of completing EHR work within 48 hours in association with scribe assistance.18 Our findings also confirm a prior report27 of high patient satisfaction in scribed visits. A study27 of scribes with 12 dermatologists in an academic dermatology practice reported positive patient-perceived association of scribe use with visit experience, for which patients expressed a high degree of scribe approval.

Of note, the self-reported results showing the benefit of scribes were of a greater relative magnitude compared with the objectively measured data. This finding may reflect PCP enthusiasm that exceeds the reality of scribe benefit. Alternatively, PCP self-report may be accurate but reflective of the best week rather than the full overall experience. All PCPs having 3 or more different scribes during their two 3-month scribe periods indicates that there was likely some variation in the experience from week to week as PCPs learned to work with new and different scribes.

Limitations

Our results must be considered in the context of the study design. First, although we have undertaken the largest crossover study, to our knowledge, assessing the association between scribe use and PCP job satisfaction to date, we recognize that our PCP sample size remains relatively small. However, crossover studies are uniquely able to reduce the subject-level variability that requires larger sample sizes in traditional, parallel randomized clinical studies.28 Second, revenue analysis was beyond the scope of our study, although the willingness of many of the participating PCPs to modestly increase their panel size in return for a scribe suggests the possibility of cost savings. Investigation of scribe use in fee-for-service or pay-for-performance health care delivery systems is warranted to measure the association between scribe use and revenue. Third, although most patients surveyed (>94%) had favorable views of scribes, qualitative analysis of patient perspectives is needed to evaluate the potential of drawbacks of using scribes. Prior research has established that primary care patients are reluctant to discuss sensitive topics, such as sexually transmitted diseases, mental health, and domestic violence, with physicians, which may be an impediment to delivering adequate care.29 Future research is needed to assess how scribes may affect such patient disclosures, particularly among vulnerable populations. Qualitative analysis is also needed to evaluate the quality of scribe documentation and coding accuracy. Fourth, surveyed patients were asked to recall their usual PCP visits with the scribed visits, which could have subjected patient response to a recall bias. However, we found that KPNC patients had a mean of 2 visits with a PCP in the study period, suggesting that a patient’s last visit likely occurred within the same year. Fifth, PCPs in the study might have been more amenable to scribe implementation than their counterparts who declined participation. However, analysis comparing physician characteristics, such as age, specialty, sex, years of employment, and years since graduation, revealed no significant differences between the 2 groups.

Conclusions

One of the drivers of increasing interest in medical scribes is the current crisis in primary care. The current PCP shortage is expected to increase to 20 400 by 2020 and up to 43 100 by 2030, with fewer graduates entering the field and more leaving because of physician burnout.30,31,32,33 Addressing physician burnout is critical to control the impending PCP shortage crisis. Although physician burnout is a multifaceted and complex issue, there is increasing evidence associating EHR adoption with increasing burnout rates.8,9,12,34 Our results suggest that the use of scribes may be one strategy to mitigate the increasing EHR documentation burden among PCPs, who are at the highest risk of burnout among physicians. Although scribes do not obviate the need for improving suboptimal EHR designs, they may help alleviate some of the inefficiencies of currently implemented EHRs.

eTable 1. Physician Survey Tool

eTable 2. Patient Survey Tool

References

- 1.Electronic Health Records (EHR) Incentive Programs https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html?redirect=/EHRIncentivePrograms. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 2.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology Hospitals Participating in the CMS EHR Incentive Programs. https://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/pages/FIG-Hospitals-EHR-Incentive-Programs.php. Accessed July 27, 2018.

- 3.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology Office-Based Health Care Professionals Participating in the CMS EHR Incentive Program. https://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/pages/FIG-Health-Care-Professionals-EHR-Incentive-Programs.php. Accessed July 27, 2018.

- 4.King J, Patel V, Jamoom EW, Furukawa MF. Clinical benefits of electronic health record use: national findings. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1, pt 2):392-404. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Lorenzetti D, Straus SE, Sykes L, Quan H. The impact of the electronic medical record on structure, process, and outcomes within primary care: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(6):732-737. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang SJ, Middleton B, Prosser LA, et al. A cost-benefit analysis of electronic medical records in primary care. Am J Med. 2003;114(5):397-403. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00057-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menachemi N, Collum TH. Benefits and drawbacks of electronic health record systems. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2011;4:47-55. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S12985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors Affecting Physician Professional Satisfaction and Their Implications for Patient Care, Health Systems, and Health Policy. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836-848. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young RA, Burge SK, Kumar KA, Wilson JM, Ortiz DF A time-motion study of primary care physicians’ work in the electronic health record era. Fam Med. 2018;50(2):91-99. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.184803 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100-e106. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753-760. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gellert GA, Ramirez R, Webster SL. The rise of the medical scribe industry: implications for the advancement of electronic health records. JAMA. 2015;313(13):1315-1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller N, Howley I, McGuire M. Five lessons for working with a scribe. Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(4):23-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gidwani R, Nguyen C, Kofoed A, et al. Impact of scribes on physician satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and charting efficiency: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):427-433. doi: 10.1370/afm.2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sattler A, Rydel T, Nguyen C, Lin S. One year of family physicians’ observations on working with medical scribes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(1):49-56. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imdieke BH, Martel ML. Integration of medical scribes in the primary care setting: improving satisfaction. J Ambul Care Manage. 2017;40(1):17-25. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bank AJ, Obetz C, Konrardy A, et al. Impact of scribes on patient interaction, productivity, and revenue in a cardiology clinic: a prospective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:399-406. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S49010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shultz CG, Holmstrom HL. The use of medical scribes in health care settings: a systematic review and future directions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(3):371-381. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.03.140224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heaton HA, Castaneda-Guarderas A, Trotter ER, Erwin PJ, Bellolio MF. Effect of scribes on patient throughput, revenue, and patient and provider satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(10):2018-2028. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.07.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karter AJ, Moffet HH, Liu J, et al. Achieving good glycemic control: initiation of new antihyperglycemic therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Diabetes Registry. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(4):262-270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-426. doi: 10.1370/afm.2121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, Kogan BA. Scribes in an ambulatory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol. 2010;184(1):258-262. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danila MI, Melnick JA, Curtis JR, Menachemi N, Saag KG. Use of scribes for documentation assistance in rheumatology and endocrinology clinics: impact on clinic workflow and patient and physician satisfaction. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018;24(3):116-121. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones J, Kenward MG. Design and Analysis of Cross-Over Trials. 2nd ed Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sankar P, Jones NL. To tell or not to tell: primary care patients’ disclosure deliberations. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(20):2378-2383. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.20.2378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis Projecting the Supply and Demand for Primary Care Practitioners Through 2020. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Research shows shortage of more than 100,000 doctors by 2030 [press release]. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; March 14, 2017.

- 32.Choi PA, Xu S, Ayanian JZ. Primary care careers among recent graduates of research-intensive private and public medical schools. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(6):787-792. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2286-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and outcomes of burnout in primary care physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41-43. doi: 10.1177/2150131915607799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pekham C. Medscape lifestyle report 2016: bias and burnout. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;09(01):011-014. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1620263 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Physician Survey Tool

eTable 2. Patient Survey Tool