Key Points

Question

Is a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant effective in the treatment of chronic low back pain?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 146 participants with chronic low back pain, the use of low-dose amitriptyline did not demonstrate an improvement in pain, disability, or work at 6 months compared with an active comparator. However, there was a reduction in disability at 3 months, an improvement in pain intensity that was nonsignificant at 6 months, and minimal adverse events reported for the treatment group.

Meaning

These results suggest that low-dose amitriptyline may be an effective treatment for chronic low back pain; although large-scale trials are needed, it may be worth considering amitriptyline, especially if the alternative is opioids.

This randomized clinical trial examines the efficacy of low-dose amitriptyline vs an active comparator in reducing pain, disability, and work absence and hindrance in individuals with chronic low back pain.

Abstract

Importance

Antidepressants at low dose are commonly prescribed for the management of chronic low back pain and their use is recommended in international clinical guidelines. However, there is no evidence for their efficacy.

Objective

To examine the efficacy of a low-dose antidepressant compared with an active comparator in reducing pain, disability, and work absence and hindrance in individuals with chronic low back pain.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A double-blind, randomized clinical trial with a 6-month follow-up of adults with chronic, nonspecific, low back pain who were recruited through hospital/medical clinics and advertising was carried out.

Intervention

Low-dose amitriptyline (25 mg/d) or an active comparator (benztropine mesylate, 1 mg/d) for 6 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was pain intensity measured at 3 and 6 months using the visual analog scale and Descriptor Differential Scale. Secondary outcomes included disability assessed using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire and work absence and hindrance assessed using the Short Form Health and Labour Questionnaire.

Results

Of the 146 randomized participants (90 [61.6%] male; mean [SD] age, 54.8 [13.7] years), 118 (81%) completed 6-month follow-up. Treatment with low-dose amitriptyline did not result in greater pain reduction than the comparator at 6 (adjusted difference, −7.81; 95% CI, −15.7 to 0.10) or 3 months (adjusted difference, −1.05; 95% CI, −7.87 to 5.78), independent of baseline pain. There was no statistically significant difference in disability between the groups at 6 months (adjusted difference, −0.98; 95% CI, −2.42 to 0.46); however, there was a statistically significant improvement in disability for the low-dose amitriptyline group at 3 months (adjusted difference, −1.62; 95% CI, −2.88 to −0.36). There were no differences between the groups in work outcomes at 6 months (adjusted difference, absence: 1.51; 95% CI, 0.43-5.38; hindrance: 0.53; 95% CI, 0.19-1.51), or 3 months (adjusted difference, absence: 0.86; 95% CI, 0.32-2.31; hindrance: 0.78; 95% CI, 0.29-2.08), or in the number of participants who withdrew owing to adverse events (9 [12%] in each group; χ2 = 0.004; P = .95).

Conclusions and Relevance

This trial suggests that amitriptyline may be an effective treatment for chronic low back pain. There were no significant improvements in outcomes at 6 months, but there was a reduction in disability at 3 months, an improvement in pain intensity that was nonsignificant at 6 months, and minimal adverse events reported with a low-dose, modest sample size and active comparator. Although large-scale clinical trials that include dose escalation are needed, it may be worth considering low-dose amitriptyline if the only alternative is an opioid.

Trial Registration

anzctr.org.au Identifier: ACTRN12612000131853

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the largest contributor to disability worldwide.1 Although there are a range of treatments available for LBP, the efficacy of these therapies are limited.2 Antidepressants are a commonly prescribed treatment for LBP in clinical practice.3 Typically, higher doses of antidepressants are used to treat depression, whereas low doses are prescribed for chronic pain, with the analgesic effects of the drug occurring independent of depression.4 The use of antidepressants is rapidly increasing, with an increase in prescriptions of 3.9 million (6.8%) over 12 months in the United Kingdom5 and 29% of these reported to be off label (unapproved indication).6 This is despite the lack of evidence from systematic reviews7 and conflicting recommendations in clinical guidelines.8

A review of national and international guidelines has highlighted that not only do recommendations for antidepressant treatment for LBP vary substantially, but 7 of 14 guidelines recommend their use, with none indicating whether they should be prescribed in high or low doses.8 Two treatment guidelines published in 2016 to 2017 provide further conflicting recommendations, 1 stating that while tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are not recommended, duloxetine hydrochloride should be considered as a second-line therapy,9 whereas the other did not recommend the use of any class of antidepressant for chronic LBP.10

A number of systematic reviews, including our Cochrane systematic review,7 have concluded that there is no clear evidence that antidepressants are more effective than placebo for LBP.11,12,13 They have highlighted the need for high-quality trials and identified limitations of previous studies including insufficient blinding, small sample sizes, and short treatment and follow-up periods (≤3 months). Moreover, no studies have examined the effectiveness of a low-dose TCA, a common method of prescribing for LBP. Amitriptyline hydrochloride is a TCA widely used in low doses to treat pain,6,14 particularly nonspecific LBP,3 independent of depression.4 However, there is no evidence to support its widespread use.

Thus, the aim of this double-blind, randomized clinical trial was to determine whether low-dose amitriptyline is effective in reducing pain, disability, and work absence and hindrance over 6 months in those with chronic, nonspecific LBP compared with an active comparator.

Methods

This study is a double-blind, randomized clinical trial, with a 2-arm, parallel-group, superiority design. The trial was registered at the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12612000131853) prior to recruitment. Ethics approval was obtained from the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee (HREC/12/Alfred/16:476/11), Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (CF12/0271-2012000106), and Eastern Health Human Ethics Committee (SERP28/1112). Trial reporting was guided by the CONSORT guidelines.15 The study protocol has been published16 and is available in Supplement 1.

Sample

A total of 146 individuals with chronic LBP were recruited through hospital, medical, and allied health clinics and advertising in local media. Written informed consent was obtained prior to study commencement.

We recruited men and women aged 18 to 75 years with chronic, nonspecific LBP, defined as pain below the costal margin and above the gluteal folds, without a specific cause and which had been present for greater than 3 months.17 Participants with any of the following were excluded: pathological entity, major coexisting illness that might confound function or for which amitriptyline may be contraindicated, another significant musculoskeletal condition, history of psychosis, current or previously diagnosed depression with or without the use of medication, prior or current use of antidepressants, current use of opioids, any contraindication or allergy to amitriptyline, pregnancy, planning or trying to become pregnant or breastfeeding, or inability to give informed consent.

Randomization and Blinding

Randomization was based on computer-generated random numbers prepared by a statistician who had no involvement in trial conduct. Participants were allocated in a ratio of 1:1 to either the intervention or active comparator group. Although it was planned that block randomization based on hospital site would be used to stratify, most participants were recruited through advertising so this was not required. The use of a central allocation that involved pharmacy-controlled randomization ensured that the allocation could not be accessed by research personnel. Allocation concealment and double blinding was ensured by the following means: dispensing of medications by the hospital clinical trial pharmacy, use of an identical comparator tablet that mimicked the adverse events of amitriptyline, and questionnaire data that was collected by research assistants blinded to group allocation.

Study Intervention

Participants in the intervention arm received a low-dose TCA, 25 mg of amitriptyline (Alphapharm Pty Ltd), and those in the control arm received an active comparator, 1 mg benztropine mesylate (Phebra Pty Ltd). These were administered in identical capsules to be taken in a single dose at the same time each day for 6 months. We selected benztropine, an active comparator because it mimics adverse events of amitriptyline while having no known effect on chronic pain.18,19 Cost of medication was funded by the study, with no sponsorship from industry. All participants were provided with usual care by their treating practitioners, and the use of nonopioid analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents was allowed.

Study Procedure

Potential participants were telephone screened using a questionnaire to determine their eligibility. They then attended the study center for an assessment to confirm eligibility and obtain informed consent. Eligible participants were randomized, completed a baseline assessment, and received the first 3 months of amitriptyline or comparator from the Alfred Hospital Clinical Trials Pharmacy. Participants were contacted by telephone at 2 weeks, 1 to 2 months, 3 months, 4 to 5 months, and 6 months to monitor their progress and any adverse events. The 3- and 6-month outcome questionnaires and the second 3 months of medication were sent to the participants by mail. The same researchers, blinded to treatment allocation, administered questionnaires, monitored adherence, and recorded adverse events. Participants’ adherence to trial medication was defined as the return of empty medication bottles at 6 months. Participants were not paid for their participation but were reimbursed for parking and transport costs.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures were administered by research assistants blinded to group allocation at baseline and 3 and 6 months. The primary outcome measure was current level of pain intensity measured at 6 months using a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS). The Descriptor Differential Scale (DDS; range, 0-20), a valid measure of pain intensity,20 was also assessed because it has been used in a previous LBP trial of antidepressants.21

The secondary outcome of disability was assessed using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ),22 a validated instrument designed to assess self-rated low back disability. Greater levels of disability are reflected by higher numbers, and scores are sensitive to change over time.23 We examined absenteeism and hindrance in performance of paid and unpaid work using the Short Form Health and Labour Questionnaire, a validated questionnaire for examining work outcomes in relation to injury.24

Additional Outcomes

Global improvement was measured using a 6-point Likert scale (range, “much worse” to “completely recovered”).25 General health status, depression, and fear of movement and/or (re)injury were measured using the EuroQol Instrument (version, EQ-5D-5L),26 Beck Depression Inventory,27 and Tampa scale,28 respectively.

Other Measures

Height, weight, and body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) were measured at baseline. We recorded any associated compensation claims and the nature of these claims. The presence of neuropathic pain was assessed using the painDetect questionnaire, with scores of 19 or greater reflecting a neuropathic component.29

Adverse events were assessed using the UKU Side-Effects Rating Scale,30 a validated questionnaire for assessing the severity and impact of adverse events on daily function due to psychotropic medication. Adverse events were examined at baseline, 2 weeks, and 2, 4, and 6 months. Adverse events were assessed according to their psychotropic, neurological, autonomic, or “other” nature and were recorded as mild, moderate, or severe. Details of major adverse events were reported to the ethics committees.

Sample Size Calculation

We determined that 150 patients (75 per group) would be needed to provide the trial with 90% power to detect a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in pain intensity (15 points on 100-mm VAS25,31) and disability (3 points on 24-point RMDQ32) between the groups at 6 months. This was assuming a 2-sided α level of .05 and mean (SD) for pain and disability of 2.5 (5) points and a maximum 20% withdrawal rate.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were based on intention to treat. Summary statistics comparing randomized arms at baseline were tabulated. Continuous outcomes were analyzed using analysis of covariance, and logistic regression was performed for binary outcomes, with adjustments for baseline measurements where appropriate. Multiple imputation by chained equations33 was used to impute missing 3- and 6-month pain, disability, and work data by treatment arm. A responder analysis was conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Task Force Research Standards,34 using the MCIDs for pain25,31 and disability32 (as described herein) to define a responder, and logistic regression for the analysis. The percentages of individuals with moderate or severe adverse events were calculated based on treatment, and differences between groups at baseline and 6 months, and over the 6-month period, were tested using χ2 tests and generalized estimating equations for repeated measures, respectively. SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 (IBM Corp), was used and P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

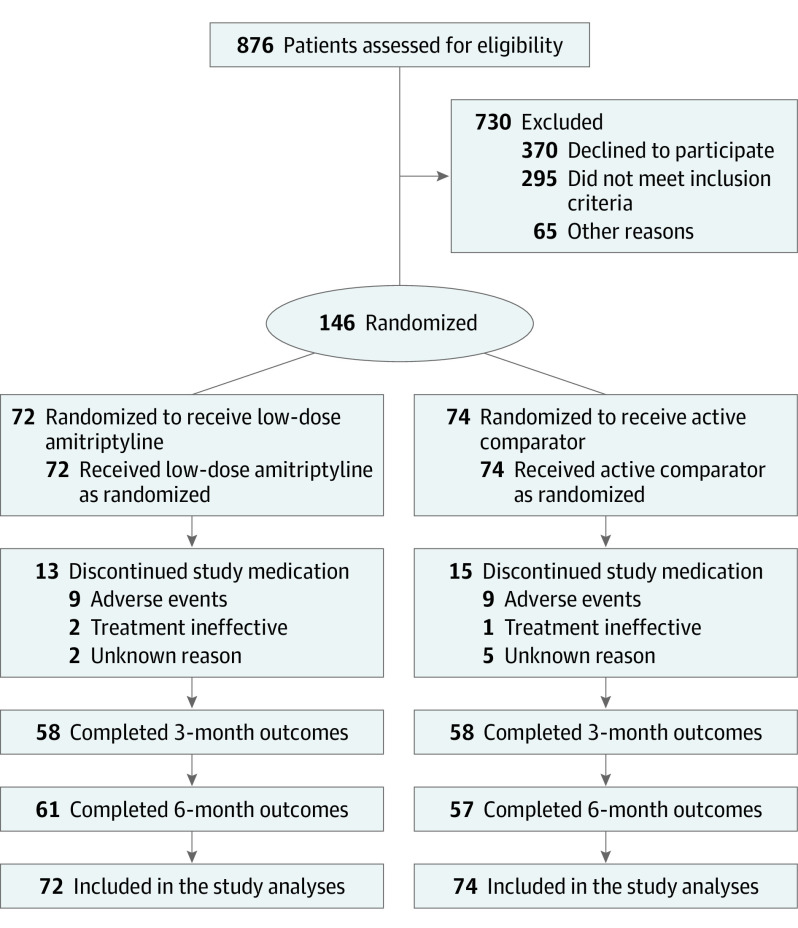

From April 30, 2012, until June 1, 2016, 876 participants were screened and 146 randomized, with 72 allocated to the low-dose amitriptyline group and 74 to the active comparator group (Figure 1). The mean (SD) age of participants was 54.8 (13.7) years, mean (SD) body mass index was 29.4 (5.8), and 90 (62%) were men. Participants had a mean (SD) pain score of 41.6 (20.8) and disability score of 7.9 (4.5). A total of 35 (25%) and 117 (85%) participants reported work absence and hindrance owing to LBP, respectively. Baseline characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram Showing the Flow of Participants Through the Trial.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics at Baseline.

| Characteristics | Valuea | |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Dose Amitriptyline (n = 72) | Active Comparator (n = 74) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 53.5 (14.2) | 56.0 (13.2) |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 28 (39) | 28 (38) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 85.9 (20.0) | 86.3 (17.4) |

| Height, mean (SD), m | 1.71 (0.09) | 1.71 (0.09) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 29.6 (6.03) | 29.3 (5.91) |

| Duration of low back pain, mean (SD), y | 13.3 (12.6) | 15.2 (13.2) |

| Neuropathic pain, No. (%)b | 9 (13) | 8 (11) |

| Compensation, No. (%) | 4 (6) | 2 (3) |

| Depression score, mean (SD)c | 10.5 (6.71) | 11.2 (8.63) |

| Paid employment, No. (%) | 41 (58) | 36 (51) |

| Pain intensity, mean (SD)d | 39.8 (20.5) | 43.4 (21.0) |

| Disability, mean (SD)e | 7.54 (4.37) | 8.15 (4.54) |

| Absence from paid/unpaid work, No. (%)f | 16 (22) | 19 (27) |

| Hindrance in paid/unpaid work, No. (%)g | 56 (81) | 61 (88) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); MCID, minimal clinically important difference.

For each of the included variables, results were based on available data.

The presence of neuropathic pain was assessed using the painDetect questionnaire (ranging from 0 to 38), with scores of 19 or greater reflecting a high likelihood of a neuropathic component.

Depression was measured using the Beck Depression Inventory, with scores ranging from 0 to 63 and higher scores (29-63) indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Pain intensity was assessed using the 100-mm visual analog scale where participants were asked to rate their current pain, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating the worst pain imaginable. The MCID was 15 points.

Disability was measured using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, with scores range from 0 to 23 and higher scores indicating greater disability. The MCID was 3 points.

Assessed using the Short Form Health and Labour Questionnaire. Participants answered yes or no to whether they were off work during the past month due to their health.

Assessed using the Short Form Health and Labour Questionnaire. Participants answered yes or no to whether their job performance was adversely affected during the past month due to their health.

Outcomes at 6 months were completed by 118 (81%) participants. Although the number of participants who did not complete the 6-month outcomes was small, we found no significant differences between participants who completed them and those who did not (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). A total of 53 (71%) participants in the active comparator group and 50 (70%) in the treatment group were found to be adherent to the study treatment.

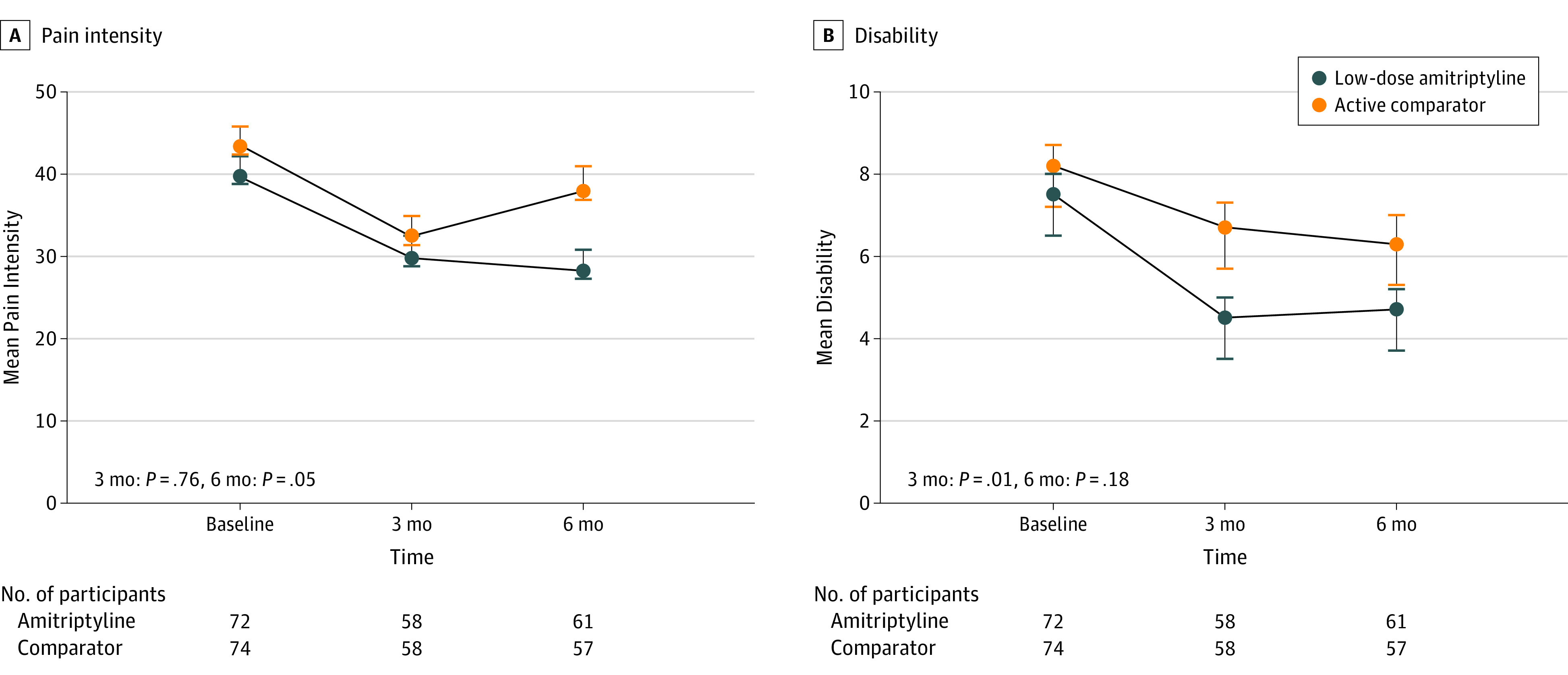

Table 2 presents the results for the primary and secondary outcomes. Although the low-dose amitriptyline group reported an adjusted mean (SE) reduction in pain intensity of 12.6 (2.7) points on the VAS from baseline to 6 months compared with a 4.8 (2.9)-point reduction for the active comparator group, treatment with low-dose amitriptyline did not result in a greater pain reduction at 6 months (adjusted difference, −7.81; 95% CI, −15.7 to 0.10) or 3 months (adjusted difference, −1.05; 95% CI, −7.87 to 5.78) (Figure 2). When multiple imputation was performed, the effect of low-dose amitriptyline on pain at 6 months was not significant (adjusted difference, −6.70; 95% CI, −14.4 to 1.04). There was no statistically significant difference in disability between groups at 6 months (adjusted difference, −0.98; 95% CI, −2.42 to 0.46); however, there was a statistically significant improvement in disability for the low-dose amitriptyline group at 3 months (adjusted difference, −1.62; 95% CI, −2.88 to −0.36) (Figure 2). There were no significant differences between groups in work absence (odds ratio [OR], 1.51; 95% CI, 0.43-5.38) or hindrance (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.19-1.51) at 6 months. Moreover, responder analyses did not show clinically meaningful differences in pain or disability between the treatment groups (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Treatment Effect on Pain Intensity, Disability, and Work Absence and Hindrance in Individuals With Chronic, Nonspecific Low Back Pain.

| Parametera | Low-Dose Amitriptyline | Active Comparator | Treatment Comparison | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 72) | 3 mo (n = 58) | 6 mo (n = 61) | Baseline (n = 74) | 3 mo (n = 58) | 6 mo (n = 57) | 3 mo | 6 mo | |||

| Difference (95% CI)b |

P Value | Difference (95% CI)b |

P Value | |||||||

| Pain intensity, mean (SE)c | ||||||||||

| Without multiple imputation | 39.8 (2.4) |

29.8 (2.7) |

28.3 (2.5) |

43.4 (2.4) |

32.4 (2.5) |

37.9 (3.1) |

−1.05 (−7.87 to 5.78) |

.76 | −7.81 (−15.7 to 0.10) |

.05 |

| With multiple imputation | NA | 32.4 (2.1) |

28.9 (2.6) |

NA | 30.0 (2.7) |

37.1 (3.2) |

−0.38 (−7.62 to 5.87) |

.91 | −6.70 (−14.5 to 0.51) |

.09 |

| Disability, mean (SE)d | ||||||||||

| Without multiple imputation | 7.5 (0.5) |

4.5 (0.5) |

4.7 (0.5) |

8.2 (0.5) |

6.7 (0.6) |

6.3 (0.7) |

−1.62 (−2.88 to −0.36) |

.01 | −0.98 (−2.42 to 0.46) |

.18 |

| With multiple imputation | NA | 4.5 (0.5) |

4.7 (0.5) |

NA | 6.5 (0.5) |

5.9 (0.6) |

−1.67 (−2.80 to −0.53) |

.001 | −0.91 (−2.27 to 0.44) |

.18 |

| Paid/unpaid work absence, No. (%)e | ||||||||||

| Without multiple imputation | 16 (22.5) |

10 (19.6) |

7 (15.9) |

19 (27.1) |

13 (26.0) |

6 (14.0) |

0.86 (0.32 to 2.31) |

.77 | 1.51 (0.43 to 5.38) |

.52 |

| With multiple imputation | NA | NA (20.8) |

NA (16.2) |

NA | NA (26.2) |

NA (16.1) |

0.78 (0.32 to 1.90) |

.58 | 1.13 (0.34 to 3.76) |

.84 |

| Paid/unpaid work hindrance, No. (%)e | ||||||||||

| Without multiple imputation | 56 (81.2) |

37 (72.5) |

30 (68.2) |

61 (88.4) |

40 (80.0) |

34 (79.1) |

0.78 (0.29 to 2.08) |

.62 | 0.53 (0.19 to 1.51) |

.24 |

| With multiple imputation | NA | NA (71.0) |

NA (67.0) |

NA | NA (79.0) |

NA (79.1) |

0.64 (0.61 to 1.62) |

.35 | 0.65 (0.21 to 1.36) |

.20 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Means and standard errors reported at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months.

Analysis of covariance, adjusted for the baseline score.

Pain intensity was assessed using the 100-mm visual analog scale where participants were asked to rate their current pain, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating the worst pain imaginable. The minimal clinically important difference was 15 points. Means and standard errors reported at baseline, 3, and 6 months.

Disability was measured using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, with scores ranging from 0 to 23 and higher scores indicating greater disability. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was 3 points.

Assessed using the Short Form Health and Labour Questionnaire (SFHLQ). Participants answered yes or no to whether they were off work during the past month due to their health. These are presented as odds ratios (95% CIs) calculated using logistic regression, adjusted for the baseline score.

Figure 2. Change in Mean Low Back Pain Intensity and Disability Scores for the Low-Dose Amitriptyline and Active Comparator Groups From Baseline to 3 and 6 Months.

A, Low back pain intensity was measured using the 100-mm visual analog scale (greater pain intensity is indicated by higher numbers). B, Low back disability was assessed using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (0-23 points; greater levels of disability are reflected by higher numbers). The number of randomized participants in each of the groups who contributed the data at each time point is shown at the bottom of the graphs. The P values, derived from the analysis of covariance, adjusted for baseline score, for the pain intensity and disability outcomes are also shown. Measurements were performed at baseline and 3 and 6 months. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

Table 3 presents data for additional outcomes. At 6 months, there were no significant differences in global improvement (adjusted difference, 0.08; 95% CI, −0.77 to 0.92), depression (adjusted difference, −0.93; 95% CI, −3.34 to 1.49), general health (adjusted difference, 5.01; 95% CI, −0.44 to 10.5), or fear of movement/reinjury (adjusted difference, −2.32; 95% CI, −4.91 to 0.26) in the treatment group compared with the active comparator group.

Table 3. Treatment Effect on Global Improvement, General Health, and Psychological Outcomes in Individuals With Chronic, Nonspecific Low Back Paina.

| Parameter | Mean (SE) | Treatment Comparison | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Dose Amitriptyline | Active Comparator | 3 mo | 6 mo | |||||||

| Baseline (n = 72) |

3 mo (n = 58) |

6 mo (n = 61) |

Baseline (n = 74) |

3 mo (n = 58) |

6 mo (n = 57) |

Difference (95% CI)b |

P Value | Difference (95% CI)b |

P Value | |

| Global improvementc | 3.53 (0.2) |

3.80 (0.3) |

3.46 (0.3) |

3.71 (0.3) |

0.08 (−0.77 to 0.92) |

.86 | ||||

| General health statusd | 69.3 (1.8) |

72.9 (2.1) |

73.9 (1.8) |

71.3 (1.7) | 71.3 (2.1) |

70.1 (2.2) |

3.20 (−1.07 to 7.47) |

.14 | 5.01 (−0.44 to 10.5) |

.07 |

| Depression scoree | 10.5 (0.8) |

7.59 (0.6) |

7.78 (0.8) |

11.2 (1.0) | 9.06 (0.8) |

8.71 (1.0) |

−0.84 (−2.42 to 0.74) |

.29 | −0.93 (−3.34 to 1.49) |

.45 |

| Fear of movement/reinjuryf | 37.7 (0.9) |

38.0 (0.9) |

36.5 (1.0) |

38.0 (0.9) | 39.0 (0.8) |

39.2 (1.2) |

−0.56 (−2.68 to 1.56) |

.60 | −2.32 (−4.91 to 0.26) |

.08 |

Means and standard errors reported at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months.

Analysis of covariance, adjusted for the baseline score, with the exception of “global improvement,” where no adjustment was made because improvement cannot be assessed at baseline.

Global improvement was measured using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from “much worse” to “completely recovered,” with higher scores indicating greater improvement.

General health status was assessed using the EuroQol-Visual Analog Scale component of the EuroQol Instrument, ranging from 0 being the worst health you can imagine and 100 being the best health.

Depression was measured using the Beck Depression Inventory, with scores ranging from 0 to 63 and higher scores (29-63) indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Fear of movement/(re)injury were measured using Tampa scale. The total score ranged between 17 and 68, with a high value indicating a greater fear of movement.

Nine (12%) participants from each group withdrew from the trial owing to adverse effects (χ2 = 0.004; P = .95). There were no significant differences between the groups in the percentage of participants reporting moderate to severe symptoms at baseline (35% intervention, 41% comparator: χ2 = 0.63; P = .43) or 6 months (26% intervention, 32% comparator; χ2 = 0.32; P = .58) (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Although the number of individuals who experienced moderate to severe symptoms appeared to be lower at 6 months than at baseline, this was not statistically significant for the intervention (35% baseline, 26% 6 months; P = .37) or comparator groups (41% baseline, 32% 6 months; P = .32). While a similar number of participants in both groups reported an increase in sleep duration at baseline (8% intervention, 12% comparator, χ2 = 3.14; P = .37), more participants in the treatment group reported an increase in duration of sleep than those in the comparator group at 6 months (55% intervention, 16% comparator, χ2 = 15.4; P < .001).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first double-blind, randomized, controlled trial to examine the efficacy of a low-dose TCA for the treatment of chronic, nonspecific LBP. Although there were no significant differences in pain, disability, and work outcomes between the groups at 6 months, there was an improvement in disability at 3 months and minimal adverse events reported at 6 months for those treated with low-dose amitriptyline compared with the active comparator group. Although the improvements in pain intensity, general health and fear of movement/reinjury at 6 months did not reach statistical significance, they suggest that low-dose amitriptytline may have an effect with a larger sample size. These findings provide support for large-scale clinical trials, with an escalating dose as required, to determine the treatment effectiveness of amitriptyline.

Previous systematic reviews, which have concluded that there is no clear evidence that antidepressants are effective for LBP, have identified major limitations of previous studies and the need for high-quality trials.7,11,12,13 The present trial aimed to address these limitations, namely, the lack of investigation of low-dose antidepressants for pain, insufficient blinding and statistical power, and short treatment and follow-up periods. We conducted a double-blind, randomized controlled trial of a low-dose TCA and compared it with an active comparator, which mimicked the adverse effects of amitriptyline and optimized blinding. The present study was sufficiently powered to detect a clinically meaningful effect of low-dose amitriptyline on pain and disability, and our treatment and follow-up periods were extended beyond those of previous studies to 6 months. While we did not meet our primary end point of a reduction in pain at 6 months, treatment with low-dose amitriptyline resulted in statistically significant improvements in disability with minimal adverse events, providing evidence to suggest that amitriptyline may have a therapeutic effect for LBP.

This finding is important given that LBP is the leading cause of disability globally,1 effective treatments for LBP are limited,2 and there is currently an epidemic of escalated usage of narcotics, with more than 50% of narcotic prescriptions issued to people with LBP.35 Moreover, recent systematic reviews have reported drug alternatives, such as paracetamol,36 opioid analgesics,37 and gabapentinoids,38 to be ineffective, leaving physicians looking for an effective alternative. Amitriptyline is commonly used for LBP, and its off-label prescription is rapidly increasing.6,14 Although TCAs are not recommended in 2016 to 2017 international guidelines,9,10 the use of low-dose amitriptyline is an attractive option for physicians given its efficacy in other pain conditions,39,40 and to many patients, who prefer the use of medications that they believe are simple, cost-effective, and prevent their condition from becoming worse.41 Moreover, the cornerstone of LBP management is encouraging individuals to stay active and progressively increase their activity levels.9,10 Given that a variety of factors, including pain, disability, and fear, are key barriers to activity and that in this trial we found that low-dose amitriptyline treatment may address a number of these factors, it is possible that low-dose amitriptyline may serve as a valuable treatment for LBP. While large trials, which include dose escalation, are needed to clarify the effect of amitriptyline treatment, it may be worth considering in the management of chronic LBP, especially if the alternative is prescribing opioids.

We found that amitriptyline, prescribed in a low dose, was well tolerated. There was a similar number of withdrawals due to adverse events for both groups, indicating that the adverse events associated with low-dose amitriptyline are no greater than those of an active comparator. Of note, we found that prior to study commencement more than 30% of participants in each group had moderate to severe symptoms that were similar to the adverse events associated with psychotropic medications.30 Given that these could not be attributed to the study medications, it suggests that a large proportion of the symptoms reported by individuals with chronic LBP who are taking TCAs may not be related to their medication use. Because low-dose TCAs are commonly prescribed for other conditions, such as headache,40 it is important for physicians to be aware of this potential issue. Furthermore, the high proportion of psychotropic symptoms reported highlights the poor health status associated with LBP and the need to consider these symptoms in the management of the condition.

Limitations

This trial has several limitations. We recruited individuals with chronic, nonspecific LBP, the most common type of LBP. While this is a potentially heterogeneous group, this is a well-recognized and clinically important population,2 which has been shown to be the leading contributor to disease burden worldwide.1 We used well-accepted, standard definitions for LBP and chronicity,2 excluded individuals with a known, pathoanatomical cause for their LBP, and did not include a subgroup of individuals with a diagnosis of depression who may have differed in their pain response to amitriptyline treatment. We used the VAS and DDS to assess pain and allow comparison with previous studies. Although our participants experienced difficulty completing the DDS, the VAS was completed without issue and provided sufficient data for analysis. We powered this trial to detect statistical and clinical significant differences in pain and disability based on previous LBP trials of antidepressants and evidence on MCIDs for these measures. However, we did not power the trial to detect differences in our work or additional outcomes and it is therefore possible that the trial was underpowered in relation to these. Our follow-up rate was 81%, which is considered acceptable for a study of short to intermediate time frame.42 Although we randomized 146, rather than the prespecified 150, the precision of the estimates of treatment effect based on the 95% CIs did not include a clinically significant effect. In this study we used an active comparator, benztropine, to reduce the potential of unblinding due to dry mouth. While benztropine has the potential to improve LBP through its sedating effect, it is unlikely that this occurred because a greater number of participants in the treatment group reported an increased sleep duration at 6 months than those in the benztropine group.

Conclusions

The results of this trial suggest that the use of low-dose amitriptyline may be an effective treatment for chronic LBP. Although we did not find statistically significant reductions in outcomes at 6 months, the findings of a reduction in disability at 3 months, an improvement in pain intensity that was nonsignificant at 6 months, and minimal adverse events with a low-dose, modest sample size and active comparator, provide support for large-scale clinical trials of low dose amitriptyline, with gradual dose escalation. In the meantime, it may be worth trying low-dose amitriptyline for these patients, especially if the only alternative is an opioid.

Trial Protocol.

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics of participants who did and didn’t provide 6 month follow-up data

eTable 2. Responder analyses examining clinical meaningful change in low back pain and disability based on treatment with low-dose amitriptyline or an active comparator

eTable 3. Percentage of participants with moderate to severe side-effects based on treatment with low-dose amitriptyline or an active comparator

References

- 1.Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):968-974. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 2017;389(10070):736-747. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30970-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Kantor E, Johnstone BM, Swindle RW. Real-world practice patterns, health-care utilization, and costs in patients with low back pain: the long road to guideline-concordant care. Spine J. 2011;11(7):622-632. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McQuay HJ, Tramèr M, Nye BA, Carroll D, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. A systematic review of antidepressants in neuropathic pain. Pain. 1996;68(2-3):217-227. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03140-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prescribing and Medicines Team . Prescriptions dispensed in the community—statistics for England, 2005-2015. National Health Service; 2016. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/prescriptions-dispensed-in-the-community/prescriptions-dispensed-in-the-community-statistics-for-england-2005-2015. Accessed March 10, 2018.

- 6.Wong J, Motulsky A, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Abrahamowicz M, Tamblyn R. Treatment indications for antidepressants prescribed in primary care in Quebec, Canada, 2006-2015. JAMA. 2016;315(20):2230-2232. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urquhart DM, Hoving JL, Assendelft WW, Roland M, van Tulder MW. Antidepressants for non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;10(1):CD001703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(12):2075-2094. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians . Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514-530. doi: 10.7326/M16-2367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management (NG59). London, England: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung JW, Zeng Y, Wong TK. Drug therapy for the treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2013;16(6):E685-E704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuijpers T, van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for chronic non-specific low-back pain. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(1):40-50. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1541-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White AP, Arnold PM, Norvell DC, Ecker E, Fehlings MG. Pharmacologic management of chronic low back pain: synthesis of the evidence. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(21)(suppl):S131-S143. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822f178f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong J, Motulsky A, Abrahamowicz M, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Tamblyn R. Off-label indications for antidepressants in primary care: descriptive study of prescriptions from an indication based electronic prescribing system. BMJ. 2017;356:j603. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urquhart DM, Wluka AE, Sim MR, et al. Is low-dose amitriptyline effective in the management of chronic low back pain? study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17(1):514. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1637-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Tulder M, Koes B, Bombardier C. Low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16(5):761-775. doi: 10.1053/berh.2002.0267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson CP, Moulin D, Watt-Watson J, Gordon A, Eisenhoffer J. Controlled-release oxycodone relieves neuropathic pain: a randomized controlled trial in painful diabetic neuropathy. Pain. 2003;105(1-2):71-78. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00160-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moulin DE, Iezzi A, Amireh R, Sharpe WK, Boyd D, Merskey H. Randomised trial of oral morphine for chronic non-cancer pain. Lancet. 1996;347(8995):143-147. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90339-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gracely RH, Kwilosz DM. The Descriptor Differential Scale: applying psychophysical principles to clinical pain assessment. Pain. 1988;35(3):279-288. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90138-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkinson JH, Slater MA, Capparelli EV, et al. Efficacy of noradrenergic and serotonergic antidepressants in chronic back pain: a preliminary concentration-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(2):135-142. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e3180333ed5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8(2):141-144. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198303000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleland J, Gillani R, Bienen EJ, Sadosky A. Assessing dimensionality and responsiveness of outcomes measures for patients with low back pain. Pain Pract. 2011;11(1):57-69. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Roijen L, Essink-Bot ML, Koopmanschap MA, Bonsel G, Rutten FF. Labor and health status in economic evaluation of health care: the Health and Labor Questionnaire. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1996;12(3):405-415. doi: 10.1017/S0266462300009764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. ; IMMPACT . Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1-2):9-19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kind P. The Euroqol Instrument: an index of health-related quality of life. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:191-201. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck A, Steer R, Garbin M. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8(1):77-100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW, Heuts PH, Lysens R. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain. 1999;80(1-2):329-339. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00229-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR, Tölle D. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(10):1911-1920. doi: 10.1185/030079906X132488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The UKU side effect rating scale: a new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1987;334:1-100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb10566.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, et al. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(1):90-94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bombardier C, Hayden J, Beaton DE. Minimal clinically important difference: low back pain: outcome measures. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(2):431-438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, et al. Report of the NIH Task Force on research standards for chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2014;15(6):569-585. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deyo RA, Von Korff M, Duhrkoop D. Opioids for low back pain. BMJ. 2015;350:g6380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saragiotto BT, Machado GC, Ferreira ML, Pinheiro MB, Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG. Paracetamol for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;6(6):CD012230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG, Williams KA, Day R, McLachlan AJ. Efficacy, tolerability, and dose-dependent effects of opioid analgesics for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):958-968. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shanthanna H, Gilron I, Rajarathinam M, et al. Benefits and safety of gabapentinoids in chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2017;14(8):e1002369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(2):318-328. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson JL, Shimeall W, Sessums L, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants and headaches: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c5222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wluka A, Chou L, Briggs A, Cicuttini F. Understanding the needs of consumers with musculoskeletal conditions: consumers’ perceived needs of health information, health services and other non-medical services: a systematic scoping review. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: MOVE muscle, bone and joint health; 2016. https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/understanding-the-needs-of-consumers-with-musculoskeletal-conditi. Accessed August 17, 2018.

- 42.Furlan AD, Malmivaara A, Chou R, et al. ; Editorial Board of the Cochrane Back, Neck Group . 2015 Updated method guideline for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back and Neck Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(21):1660-1673. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics of participants who did and didn’t provide 6 month follow-up data

eTable 2. Responder analyses examining clinical meaningful change in low back pain and disability based on treatment with low-dose amitriptyline or an active comparator

eTable 3. Percentage of participants with moderate to severe side-effects based on treatment with low-dose amitriptyline or an active comparator