Abstract

Context.

A notable gap in the evidence-base for palliative care (PC) for cancer is that most trials were conducted in specialized centers with limited translation and further evaluation in “real-world” settings. Health systems are desperate for guidance on effective, scalable models.

Objective.

Determine the effects of a nurse-led PC intervention for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and their family caregivers (FCGs) in a community-based setting.

Methods.

Two-group, sequential, quasi-experimental design with Phase 1 (Usual care, UC) followed by Phase 2 (Intervention) conducted at three Kaiser Permanente Southern California sites. Participants included patients with stage 2-4 NSCLC and their FCG. Standard measures of quality of life (QOL) included FACT-L, FACIT- SP12, City of Hope Family QOL; other outcomes were distress, health care utilization, caregiver preparedness and burden.

Results.

Patients in the intervention cohort had significant improvements in three (physical, emotional, and functional well-being) of the five QOL domains at 1-month that were sustained through 3-months compared to UC (p<.01). Caregivers in the intervention cohort had improvements in physical (p=.04) and spiritual well-being (p=.03) and preparedness (p=.04) compared to UC. There were no differences in distress or health care utilization between cohorts.

Conclusions.

Our findings suggest that a research-based PC intervention can be successfully adapted to community settings to achieve similar, if not better, QOL outcomes for patients and FCGs compared to UC. Nonetheless, additional modifications to ensure consistent referrals to PC and streamlining routine assessments and patient/FCG education are needed to sustain and disseminate the PC intervention.

Keywords: Palliative care, lung cancer, implementation, translation, community-practice

Introduction

Although a number of professional societies, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), have recommended that palliative care (PC) be integrated into standard oncology practice,1 the decisional dilemma for most health care systems remains as to the most effective and sustainable approach to providing PC for patients with serious illnesses in “real-world”, community-based settings. We recently described the protocol for the Translation of a Lung Cancer Palliative Care Intervention (TLC-PCI) study and lessons learned from adapting and implementing the PC intervention at three sites in a large integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC)).2

We identified several early key lessons learned that have notable implications for efforts to broadly disseminate and implement any new practice derived from ideal research settings to real-world community practice. Implementation facilitators included external pressures, internal readiness, and adaptability of the intervention to local contexts. Barriers included the rapidly changing lung cancer therapeutic landscape and perceived need for PC support by patients and providers,3 insufficient staffing to meet existing demands for PC services by patients with malignant and non-malignant disease, and acceptability of efforts to achieve PC integration given existing resource constraints.

The purpose of this paper is two-fold: 1) describe the effects of the PC intervention on patient (quality of life (QOL), distress, and health care utilization) and family caregiver (quality of life, preparedness, burden, and distress) outcomes over 3 months compared to usual care and 2) describe strategies to address several modifiable implementation barriers identified in the earlier report to further strengthen, sustain, and spread components of the PC intervention within the health care system.

Methods

Study Design

The design was a two-group, prospective sequential, quasi-experimental, tandem enrollment design wherein the usual care group was accrued and followed during Phase 1 (Jan 2015-Mar 2016) and the intervention group was accrued and followed during Phase 2 (Jun 2016-Mar 2018) at three KPSC sites. Phase I patients and family caregivers (FCGs) continued to receive usual care which could have included PC consultation and participation in telephone surveys at baseline, 1- and 3-months. Phase 2 was focused on implementation of the PC intervention following the same measurement scheme.

Sample

The sample included English-speaking patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of stage 2-4 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from three KPSC sites. Family caregivers who were 18 years or older and designated by the patient as a person closely involved in their care were eligible for the study.

Power calculation

The trial was designed to have the ability to detect a moderate effect size or 0.5 SD. The correlation of the repeated measures was assumed to be between 0.5 and 0.8, which implies that the SD of changes from baseline would be smaller (~70% or less) than the SD of individual measurements. Conservatively defining effect size in terms of individual measurements, an effect of 0.5 SD can be detected with 90% power (alpha=0.05, 2-sided testing), with 78 and 93 FCGs in usual care and PC intervention groups, respectively. Sample size estimates for patients were set at 98 and 116, respectively, as we estimated that 20% of patients would not have a participating FCG. All sample sizes were inflated to account for an anticipated 25% attrition rate at 1-month follow-up.

Study Procedures

The clinic PC registered nurses were responsible for patient and FCG recruitment, consent, and PC intervention implementation. Our recruitment approach was similar across both study phases. Patients who were referred to PC by their oncologists or other specialists were approached by the nurse about the study in person during their initial PC consult or by telephone. Patients were then asked if they had a FCG who would also like to participate. Since referrals were provider-dependent, we also proactively identified patients through monthly queries of the EMR for patients newly diagnosed with NSCLC. The nurse performed a chart review to determine patients’ appropriateness before a letter and brochure was sent via U.S. mail and subsequently followed up via telephone within 7-10 days to assess patients’ interest.

During Phase 1, patients and FCGs had limited interactions with the nurses (n=5 across 3 outpatient clinics) other than to complete the consent forms. All telephone assessments at baseline, 1, and 3 months were conducted by the research staff. For Phase 2, nurses (n=6) recruited and consented patients and FCGs, completed the baseline assessments, developed the interdisciplinary care plans, and provided the teaching sessions and phone follow-ups. Research staff not involved with the PC intervention completed the 1 and 3 month assessments.

TLC-PC Intervention

The TLC-PC intervention was adapted from earlier work at City of Hope4,5 and described recently.2 The PC intervention consisted of three key components: comprehensive patient/FCG assessment using standardized study measures, interdisciplinary care planning, and patient/FCG education. The first component involved a comprehensive baseline assessment of the patient’s and caregiver’s QOL followed by the development of an individualized interdisciplinary care plan based on patient’s and FCG’s concerns. The care plan was then discussed by the interdisciplinary PC team and PC team members made recommendations for any additional supportive services with follow-up by the nurses to ensure that appropriate referrals were generated. The third component included tailored educational sessions guided by the QOL model specific to concerns for NSCLC for patients and FCGs. The first patient session covered physical and psychological issues and the second, social and spiritual; sessions could be combined depending on the patient’s preferences and needs. A third teaching session was held with the FCG alone. Patients and FCGs also received 1-2 semi-structured follow-up calls to reinforce content from the teaching sessions or address outstanding concerns.

Process Measures

The number and duration of the education sessions were tracked. Measures of satisfaction and effectiveness with the education sessions were assessed from the perspective of the nurses, patients, and FCGs. At the end of each session, nurses rated the effectiveness of their session on a 0 (not at all effective) to 10 (very effective) point scale. Patients and FCGs were asked at 3 months: “How satisfied are you with the teaching program? and How prepared did you feel about self-care in relation to the teaching program?” using a 1 (very) to 5 (not at all) point scale.

Patients and FCGs completed an 8-item care experience survey [1 (always/a great deal) to 4 (never/not at all) point Likert scale] developed by the health care system that asked their perception about the care they received from doctors and staff for their lung cancer in the previous 3 months from the start of the study. Cronbach’s alpha for this survey was 0.85.

Outcome Measures

For patient-centered outcomes, the following instruments were administered at baseline, 1, and 3 months. Quality of life (QOL) was measured with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L)6 and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spirituality Subscale (FACIT-Sp-12)7 for spiritual well-being. The distress thermometer provided a general assessment of distress.8

Patient health care utilization measures were derived from KPSC’s comprehensive electronic medical records including acute care encounters (hospitalizations, observational stays, emergency department visits, and urgent care) and use of supportive services. Quality of end-of-life care measures included documentation of advance care planning and a proxy decision maker, chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life, use of home-based PC, hospice referral and enrollment, and place of death. Days at home, considered as an integrated patient-centered outcome, was calculated as 30 days minus the number of inpatient days in an acute care or skilled nursing facility.9

FCG-centered outcomes were measured with the City of Hope-QOL-Family instrument,10,11 Preparedness Scale,12,13 Caregiver Burden Scale,14 and distress thermometer.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the SAS®9.4. All results are based on an intention-to-treat analysis. Participants who completed at least one follow-up assessment (at either 1 or 3 months) were included in the predictive mixed models analysis. Chi-squared statistic or Wilcoxon tests were used to compare selected demographic, clinical, or care characteristics between groups. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the probability of being in the usual care or PC intervention cohort. Baseline patient characteristics (age, gender, education, marital status, years since lung cancer diagnosis, lung cancer stage, presence of other cancer, and study site) were used in propensity score calculations for patients. Similar calculations were made for FCGs, adjusting for baseline caregiver characteristics (age, gender, marital status, study site), but also including primary patient variables (age, presence of other cancer, lung cancer stage, years since diagnosis). Mixed model with repeated measures (baseline, 1, and 3 months) was used for prediction of outcome measures, and to determine significance of group effects and interaction effects between group and time. Propensity score adjustments were used in the mixed model analysis in lieu of the addition of multiple covariates. Patient and FCG quality of life scores, distress levels, caregiver burden, and other metrics were analyzed in the same manner.

Results

Baseline Sample Characteristics of Patients and Caregivers

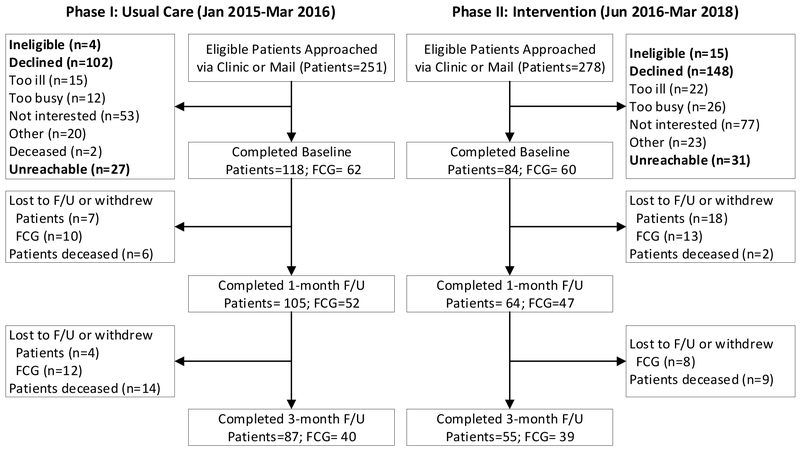

A total of 202 patients and 122 FCGs were eligible and enrolled in the study between January 2015 through December 2017 (Figure 1). Of this total, 118 patients and 62 FCGs in the usual care cohort and 84 patients and 60 FCGs in the PC intervention cohort completed the baseline assessments and were included in the primary outcome analysis if they had at least one subsequent follow-up assessment. The majority of patients came from clinic referrals (75%) versus via EMR screening (25%). Patient accrual with Phase II did not meet our target due to significant challenges with recruitment across all three sites. Moreover, patient attrition over the 3 months was high and was mostly due to death and loss to follow-up or withdrawals (phase 1: 26%; phase II: 35%). Caregiver dropouts were often due to patient deaths. Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of patients and FCGs who dropped out were not significantly different from those who completed the study.

Figure 1.

Patient and Caregiver Sample Flow

The baseline socio-demographics and clinical characteristics of patients and FCGs were similar between phase I and II (Table 1). There was a higher percentage of FCG participation in phase II (73%) compared to phase I (53%). Lower than expected participation by FCGs was mostly due to patients’ reluctance to impose additional burden on their loved ones.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Patients and Family Caregivers

| Patients | Caregivers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Usual Care |

Phase II: PCI |

Phase I: Usual Care |

Phase II: PCI |

|

| (n=118) | (n=84) | (n=62) | (n=60) | |

| Age (y) | 67.5 ± 10.3 | 67.6 ± 11.3 | 63.8 ± 11.5 | 63.0 ± 12.4 |

| Female | 71 (60.2%) | 47 (56.0%) | 38 (61.3%) | 35 (58.3%) |

| BMI | 26.5 ± 5.1 | 25.6 ± 5.2 | - | - |

| Hispanic or Latino | ||||

| Yes | 15 (12.7%) | 10 (11.9%) | 5 (8.2%) | 9 (15.5%) |

| No | 103 (87.3%) | 73 (86.9%) | 56 (91.8%) | 49 (84.5%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (1.6%) | 2 (3.3%) |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 6 (5.1%) | 8 (9.5%) | 5 (8.1%) | 3 (5.4%) |

| Asian | 9 (7.6%) | 6 (7.1%) | 3 (4.8%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Caucasian | 102 (86.4%) | 64 (76.2%) | 53 (85.5%) | 47 (83.9%) |

| Native-American | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Other | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (6.7%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (6.7%) |

| Religion | ||||

| None | 16 (13.6%) | 11 (13.1%) | 11 (17.7%) | 8 (13.3%) |

| Catholic | 43 (36.4%) | 21 (25.0%) | 18 (29.0%) | 15 (25.0%) |

| Protestant | 44 (37.3%) | 35 (41.7%) | 22 (35.5%) | 24 (40.0%) |

| Other | 15 (12.7%) | 16 (19.0%) | 11 (17.7%) | 12 (20.0%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Education | ||||

| High School | 45 (38.1%) | 40 (47.6%) | 20 (32.3%) | 20 (33.3%) |

| College | 73 (61.9%) | 44 (52.4%) | 42 (67.7%) | 39 (65.0%) |

| Missing | - | - | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 9 (7.6%) | 6 (7.1%) | 4 (6.4%) | 2 (3.3%) |

| Separated or Divorced | 10 (8.5%) | 14 (16.7%) | 54 (87.1%) | 51 (85.0%) |

| Widowed | 19 (16.1%) | 9 (10.7%) | 1 (1.6%) | 6 (10.0%) |

| Married or Partnered | 80 (67.8%) | 55 (65.5%) | 3 (4.8%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Living situation | ||||

| Alone | 18 (15.2%) | 10 (11.9%) | - | - |

| Spouse | 51 (43.2%) | 46 (54.8%) | - | - |

| Spouse and Others | 25 (21.2%) | 14 (16.7%) | - | - |

| Adult Children | 9 (7.6%) | 6 (7.1%) | - | - |

| Other | 15 (12.7%) | 8 (9.5%) | - | - |

| Relationship to patient | ||||

| Spouse/Partner | - | - | 42 (67.7%) | 45 (75.0%) |

| Parent | - | - | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Daughter | - | - | 9 (14.5%) | 8 (13.3%) |

| Son | - | - | 2 (3.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other | - | - | 9 (14.5%) | 4 (6.7%) |

| Missing | - | - | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.3%) |

| Employment status* | ||||

| Self-employed | 3 (2.5%) | 5 (6.0%) | - | - |

| Employed <32 hrs/wk | 3 (2.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | - | - |

| Employed ≥32 hrs/wk | 15 (12.7%) | 3 (3.6%) | - | - |

| Unemployed | 97 (82.2%) | 72 (85.7%) | - | - |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (3.6%) | - | - |

| Household income* | ||||

| $10,000 or less | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (2.4%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| $10,001 to $20,000 | 10 (8.5%) | 6 (7.1%) | 5 (8.1%) | 4 (6.7%) |

| $20,001 to $30,000 | 16 (13.6%) | 3 (3.6%) | 4 (6.5%) | 3 (5.0%) |

| $30,001 to $40,000 | 11 (9.3%) | 9 (10.7%) | 4 (6.5%) | 6 (10.0%) |

| $40,001 to $50,000 | 15 (12.7%) | 10 (11.9%) | 13 (21.0%) | 7 (11.7%) |

| Greater than $50,000 | 61 (51.7%) | 39 (46.4%) | 32 (51.6%) | 28 (46.7%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (2.5%) | 15 (17.9%) | 3 (4.8%) | 11 (17.4%) |

| Lung cancer stage | ||||

| II | 10 (8.5%) | 2 (2.4%) | - | - |

| III | 32 (27.1%) | 20 (24.1%) | - | - |

| IV | 76 (64.4%) | 61 (73.5%) | - | - |

|

Years since lung cancer diagnosed |

0.9 ± 1.7 | 1.0 ± 3.0 | - | - |

| Treatment (from dx to 3 mo f/u) | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 71 (60.2%) | 50 (59.5%) | - | - |

| Radiation therapy | 22 (18.6%) | 14 (16.7%) | - | - |

| Lung-cancer related surgery | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | - | - |

| Other cancer diagnosis | 29 (24.6%) | 25 (29.8%) | - | - |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 8.6 ± 3.14 | 9.7 ± 2.78 | - | - |

| Study site | ||||

| 1 | 55 (46.6%) | 31 (36.9%) | 27 (43.6%) | 19 (31.7%) |

| 2 | 32 (27.1%) | 36 (42.9%) | 23 (37.1%) | 29 (48.3%) |

| 3 | 31 (26.3%) | 17 (20.2%) | 12 (19.4%) | 12 (20.0%) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD

p<.05, patients only

Process Measures, Satisfaction, and Care Experience

Approximately 75% of patients (n=62) and 78% of FCGs (n=47) received at least one education session with an average of 1.8±0.54 sessions per patient. Non-participation was primarily due to deaths and withdrawals in the first month. The first patient education session often covered physical symptoms followed by psychological, social, and spiritual topics. Patients were joined by a family member for 25% of the sessions. Most of the education sessions were completed via phone (>60%). The average duration for the patient sessions were 40±13 minutes (first) and 32±11 minutes (second); FCG average duration was 36±13 minutes.

The nurses’ ratings of the effectiveness of the education sessions were high, 8.1±1.5 (patients) and 8.3±1.3 (FCG). Ratings by the patients (1.4 ± 0.7) and FCGs (1.4 ± 0.8) regarding their satisfaction with the education sessions were similarly positive. They also reported feeling more prepared to engage in self-care as a result of the education sessions: patients (1.5 ± 0.6) and FCGs (1.5 ± 0.7).

Ratings of care experience by both patients and FCGs were relatively positive during usual care (Table 2); however, small incremental improvements were observed only with patient ratings from the usual to intervention phase in the areas of alleviating pain/discomfort, lessening burden, and assisting with decision making and addressing things that worry patients the most.

Table 2.

Patient and Caregiver Care Experience in the Past 3 Months

| Patients | Caregivers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Usual Care (n=86) |

Phase II: PCI (n=55) |

P value |

Phase I: Usual Care (n=40) |

Phase II: PCI (n=39) |

P value |

|

| 1. Alleviated pain or discomfort | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 0.03 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.9 |

| 2. Lessened burden | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 0.002 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.1 |

| 3. (Care team) worked well together | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.07 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.05 |

| 4. Listened | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.08 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 5. Answered questions | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 0.02 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 6. Explained what to expect with illness | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.3 |

| 7. Helped with things that worry you most | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.01 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 0.1 |

| 8. Helped with making decisions | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 0.01 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 0.4 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD

Note: Response options for questions 1-6, 1=Always, 2=Usually, 3=Sometimes, 4=Never and 5=Not Sure; for questions 7 and 8, 1=A great deal, 2=Quite a bit, 3=Somewhat, 4=Not at all, and 5=Not Sure

All responses except for “Not sure” were counted

Patient Quality of Life, Distress, and Functioning over 3 months

Baseline scores on the FACT-L were lower (physical, emotional, functional, and lung cancer subscale) with the intervention compared to the usual care cohort (Table 3). There were significant immediate improvements in these four domains at the 1-month assessment that were sustained through 3 months with the intervention cohort compared to no changes in the usual care cohort (p<.01). Social and spiritual well-being and general distress were similar between cohorts at baseline with no significant differences over 3 months (p>.05).

Table 3.

Patient Quality of Life, Distress, and Functioning*

| Phase I: Usual Care | Phase II: PCI | PS Adjusted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=106) |

Week 4 (n=105) |

Week 12 (n=87) |

Baseline (n=64) |

Week 4 (n=63) |

Week 12 (n=55) |

p-value | ||

| Quality of Life | Group | Group x Time |

||||||

| FACT-L Total (0-144↑) | 98.4±20.2 | 100.8±20.7 | 102.5±20.6 | 91.7±22.1 | 102.0±20.9 | 104.3±17.7 | 0.53 | <0.01 |

| Physical well being | 19.5±5.9 | 20.2±5.8 | 20.9±5.8 | 17.3±6.4 | 20.4±5.4 | 19.9±5.6 | 0.23 | <0.01 |

| Social well being | 20.9±5.3 | 21.7±4.8 | 21.2±4.4 | 21.2±4.3 | 21.5±5.0 | 21.8±4.1 | 0.75 | 0.22 |

| Emotional well being | 18.5±4.9 | 19.0±4.8 | 18.9±4.4 | 16.9±5.0 | 19.2±4.0 | 19.7±4.2 | 0.52 | <0.01 |

| Functional well being | 16.6±6.1 | 16.8±6.5 | 17.5±6.7 | 15.3±7.2 | 17.2±6.8 | 18.4±5.7 | 0.62 | <0.01 |

| Lung cancer subscale | 22.9±5.2 | 23.1±4.9 | 23.9±5.0 | 21.0±5.4 | 23.7±5.5 | 24.5±5.0 | 0.70 | <0.01 |

| FACIT-SP12 (0-48↑) | 36.4±8.9 | 36.0±10.1 | 37.1±7.9 | 36.3±9.3 | 37.9±9.1 | 38.0±8.0 | 0.47 | 0.14 |

| Peace | 12.8±2.7 | 12.8±3.0 | 12.9±2.8 | 12.8±2.8 | 13.2±3.1 | 13.2±2.8 | 0.59 | 0.40 |

| Meaning | 12.3±3.2 | 12.0±3.7 | 12.3±3.3 | 12.0±3.7 | 12.5±3.5 | 12.7±3.3 | 0.69 | 0.12 |

| Faith | 11.3±4.5 | 11.3±4.4 | 12.0±3.8 | 11.5±4.4 | 12.1±4.1 | 12.1±3.9 | 0.37 | 0.38 |

| General Distress (↓0-10) | 4.5±2.9 | 4.5±2.8 | 4.4±2.8 | 4.4±2.8 | 3.8±2.9 | 3.4±2.9 | 0.63 | 0.12 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD

Abbreviations: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spirituality Subscale (FACIT-SP12); propensity score (PS) adjusted model

Patients need to have data on at least two time point to be included in the analysis

Arrows indicate direction of better scores

Patient Healthcare Resource Utilization over 3 Months

As expected, use of supportive services such as social work increased during the intervention phase with very few differences in the use of chaplaincy, psychiatry, nutrition, or pulmonary rehabilitation services and home-based PC (Table 4). PC intervention patients who did not have any documentation of being touched in outpatient PC during the 3-month period (11%) either died or dropped out soon after completing their baseline measures. There were no significant differences in use of acute care services (hospitalizations, observational stays or emergency department visits, and urgent care visits) between the usual care and intervention cohorts during the 3-month follow-up period.

Table 4.

Patient Healthcare Utilization During 3 Months on Study

| Phase I: Usual Care (n=118) |

Phase II: PCI (n=84) |

All Patients (n=202) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Supportive Services | |||

| Outpatient PC visits | 45 (38.1%) | 75 (89.3%) | 120 (59.4%) |

| Home-based PC | 6 (5.1%) | 4 (4.8%) | 10 (5.0%) |

| Chaplaincy | 5 (4.2%) | 10 (11.9%) | 15 (7.4%) |

| Social work | 37 (31.4%) | 51 (60.7%) | 88 (43.6%) |

| Psychiatry/psychology | 5 (4.2%) | 2 (2.4%) | 7 (3.5%) |

| Nutrition | 5 (4.2%) | 3 (3.6%) | 8 (4.0%) |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Acute Care Use | |||

| Hospitalizations | 25 (21.2%) | 19 (22.6%) | 44 (21.8%) |

| mean (range) | 0.3 (0 - 5) | 0.3 (0 - 3) | 0.3 (0 - 5) |

| Emergency dept visits/observational stays | 38 (32.2%) | 23 (27.4%) | 61 (30.2%) |

| mean (range) | 0.5 (0 - 5) | 0.4 (0 - 4) | 0.5 (0 - 5) |

| Urgent care visits | 14 (11.9%) | 17 (20.2%) | 31 (15.3%) |

| mean (range) | 0.1 (0 - 3) | 0.3 (0 - 3) | 0.2 (0 - 3) |

| Advance Care Planning and Code Status | |||

| Advance care planning documentation | 91 (77.1%) | 65 (77.4%) | 156 (77.2%) |

| Proxy decision maker documentation* | |||

| No | 41 (34.7%) | 8 (9.5%) | 49 (24.3%) |

| Yes | 77 (65.3%) | 76 (90.5%) | 153 (75.7%) |

| Most recent code status | |||

| DNR | 24 (20.3%) | 14 (16.7%) | 38 (18.8%) |

| Full Code | 76 (64.4%) | 58 (69.0%) | 134 (66.3%) |

| None/Missing | 18 (15.3%) | 12 (14.3%) | 30 (14.9%) |

| Vital Status and End of Life Care | |||

| Hospice referral | |||

| No | 87 (73.7%) | 70 (83.3%) | 157 (77.7%) |

| Yes | 31 (26.3%) | 14 (16.7%) | 45 (22.3%) |

| Hospice enrolled of those referred | |||

| No | 1 (3.2%) | 1 (7.1%) | 2 (4.4%) |

| Yes | 27 (87.1%) | 13 (92.8%) | 40 (88.9%) |

| Unknown | 3 (9.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Death within 3 months of baseline | 20 (16.9%) | 11 (13.1%) | 31 (15.3%) |

| Home | 14 (70.0%) | 7 (63.6%) | 21 (67.7%) |

| Hospital | 5 (25.0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 8 (25.8%) |

| Other/Unknown | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (6.5%) |

| Days at home in the last 90 days of life | 84.5±5.0 | 87.2±5.8 | 85.5±5.4 |

| Days at home in the last 30 days of life | 26.9±3.3 | 27.2±5.8 | 27.0±4.2 |

| Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life | 3 (15.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 4 (12.9%) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD

Manual chart review of all notes during 3 months

Patient Quality of End-of-Life Care

Documentation of advance care planning in the form of an advance directive or living will (77%) and designation of a proxy decision maker (90%) were high during both phases. Code status also did not differ, with approximately 66% of patients electing full code; 64% of patients with stage IV had a full code status. A similar percentage of patients enrolled in hospice upon referral across the two phases (89%). For patients who died (n=20 and n=11) within the 3-month follow-up, the number of days at home in the last 90 days of life were 84.5±5.0 and 87.2±5.8 for the usual care and PC intervention cohorts, respectively. Very few of the deceased patients received chemotherapy in the last two weeks of life (13%); 68% died at home with no differences between the two cohorts.

Caregiver Quality of Life, Perceptions of Preparedness, Burden, and Distress over 3 Months

Similar to intervention patients, all domains of QOL for FCGs were lower at baseline compared to the usual care cohort (Table 5). The FCG intervention cohort showed improvements in overall QOL scores that approached significance compared to usual care (p=.05). Perception of preparedness for caregiving also showed positive changes in the intervention cohort (p=.04) compared to usual care. Distress and burden did not differ over time by groups with the exception of the subjective demand subscale where the scores changed in an unexpected direction.

Table 5.

Family Caregiver Quality of Life, Preparedness, Burden, and Distress*

| Phase I: Usual Care | Phase II: PCI | PS Adjusted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=53) |

Week 4 (n=52) |

Week 12 (n=40) |

Baseline (n=47) |

Week 4 (n=45) |

Week 12 (n=39) |

p-value | ||

| Group | Group x Time |

|||||||

|

Quality of Life Family Scale Total (0-370↑) |

231.7±52.8 | 229.8±49.0 | 220.8±46.6 | 215.0±46.6 | 225.7±47.5 | 228.7±41.1 | 0.69 | 0.05 |

| Physical well-being | 36.8±7.9 | 35.8±9.7 | 32.1±10.4 | 34.5±10.4 | 35.6±9.3 | 34.5±8.6 | 0.80 | 0.04 |

| Psychological well-being | 90.0±27.9 | 88.7±25.4 | 85.3±24.3 | 80.4±22.0 | 84.5±22.0 | 86.2±20.0 | 0.16 | 0.31 |

| Social well-being | 59.2±15.5 | 58.2±15.4 | 57.1±16.0 | 54.9±17.2 | 55.9±16.1 | 58.3±15.7 | 0.82 | 0.53 |

| Spiritual well-being | 45.7±13.0 | 47.1±11.2 | 43.3±10.4 | 45.1±13.0 | 49.7±12.6 | 49.6±11.4 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

|

Caregiving Preparedness (0-32↑) |

23.0±5.0 | 23.0±4.7 | 22.1±5.4 | 22.9±5.4 | 24.4±5.3 | 24.7±4.3 | 0.47 | 0.04 |

|

Caregiver Burden Total (↓0-70) |

45.3±5.3 | 42.8±4.6 | 43.8±6.0 | 45.3±6.0 | 44.0±6.3 | 43.1±6.1 | 0.91 | 0.76 |

| Objective | 20.0±4.3 | 18.6±3.5 | 18.6±4.1 | 22.8±3.4 | 20.0±4.3 | 19.3±3.3 | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| Subjective demand | 11.9±1.1 | 11.7±1.6 | 12.3±1.1 | 9.5±3.2 | 11.6±1.8 | 11.5±2.4 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Subjective stress | 13.4±2.0 | 12.6±2.2 | 12.9±1.8 | 13.1 ±2.9 | 12.5±2.3 | 12.4±2.1 | 0.37 | 0.97 |

| General Distress (↓0-10) | 5.2±2.6 | 4.6±2.5 | 4.6±2.7 | 4.4±2.7 | 4.0±2.4 | 4.2±2.9 | 0.07 | 0.91 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD

Caregivers need to have data on at least two time point to be included in analysis

Arrows indicate direction of better scores

Discussion

Translating and evaluating evidence-based PC interventions generated from specialty care centers to community settings is a high priority for the field and practice of PC.15-17 The major finding of this quasi-experimental study conducted at three community oncology practices is that a brief, nurse-led palliative care intervention provided to patients with stage 2-4 NSCLC and their family caregivers was associated with significant, clinically important18 improvements in patients’ overall quality of life over 3 months compared to usual care. The PC intervention had marginal significant positive effects on family caregivers’ quality of life and perception of preparedness for caregiving. These findings compare favorably with the earlier seminal study conducted at a specialized cancer center4,5 and other PC studies for adults with advanced cancer.19

It is important to note that in contrast to the original study where usual care meant that patients did not receive any specialist PC care, patients recruited during the usual care phase for this study received some element of PC care which could have potentially diluted differences between groups. In fact, approximately 38% of the usual care cohort received outpatient PC touches either in the form of clinic or telephone visits during the 3-month follow-up as the study did not restrict routine care. The lack of effect on patients’ social and spiritual well-being may reflect that these domains are simply difficult to change in the face of a serious illness or implementation of the PC intervention was suboptimal. While the process data showed that these domains were covered at a similar frequency during the individualized education sessions as the physical and psychological domains, the quality of teaching and guidance by the nurses, especially around spiritual concerns, may have been suboptimal due to the discomfort expressed by the nurses in addressing this topic as well as limited access to chaplains at two of the sites and no chaplaincy at one site. A recent systematic review suggests that spiritual care competencies and training for PC team members need to be refined as well, further research is needed to better conceptualize spirituality and associated interventions to meet the needs of diverse patient populations.20

Interestingly, for FCGs, the PC intervention appears to have a positive effect on physical and spiritual well-being and perception of preparedness, none of which was found in the earlier study. A recent study of early PC for FCGs of patients newly diagnosed with lung or gastrointestinal cancer showed that while depressive symptoms improved, there was no positive impact on FCG quality of life.21 Differences across studies could be attributed to the intervention components and/or responsiveness of measures. Jacobs et al22 found that distress is interdependent in patients and FCGs, with FCGs experiencing greater anxiety, while patients report more depressive symptoms.

With regard to implementation and uptake, recruitment challenges for this translational study were due in part to our heavy reliance on provider referrals, requirement for written informed consent, and lack of integration of the assessment surveys within routine clinical workflows. The use of short video testimonials about PC in specialty clinics may help promote patient and family demand for PC and lead to more reliable and earlier referrals to PC in the future if default, automated referrals to PC for newly diagnosed patients is not an acceptable option for upstream specialty providers. Such videos may also be used for provider education to dispel myths and misunderstandings about PC.

Sustaining the lung cancer-specific comprehensive assessment battery used in this study is not realistic given that PC clinics provide care to patients with other serious illnesses. Our health care system is now working towards streamlining standardized EMR-based assessments across our PC services to include use of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS),23 distress thermometer,8 and the Palliative Performance Scale24 to inform patients’ care plans and for ongoing performance improvement efforts. While routine assessments on all patients receiving PC will provide a more unbiased evaluation of PC’s impact, accounting for death and inability to complete the surveys due to worsening health would continue to be a challenge. While there are no discussions yet regarding the routine use of FCG measures to assess PC’s impact on FCG outcomes, our health system is working towards implementing a FCG bereavement measure for all deceased members in the near future.

Although the provision of three individualized patient and FCG education sessions is far more realistic than the original six sessions, the nurses acknowledged that this would be difficult to sustain given their growing clinical responsibilities. The programs are exploring a combination of patient and FCG education formats including integration of teaching into the after-visit summaries, directing patients to the online portal for other e-learning resources, and planning for group education sessions for greater efficiencies.

Limitations

This translational study was not without limitations. The main threat to internal validity owing to the sequential, non–randomized design are the secular changes in lung cancer and palliative care treatment and practice across the two phases. It was not practical to randomize at either the participant or site level due to potential cross-contamination across PC team members and costs associated with a large number of sites, respectively. Moreover, when the study was initiated in 2014, our health system had already established a joint oncology and palliative care department goal that all stage 3-4 NSCLC patients be referred to PC thus patient randomization to receive PC or not was not acceptable. Nevertheless, we plan to conduct additional analyses to compare EMR-based outcomes between study patients, those who declined, and patients from non-study sites. Second, there may be selection bias among patients and FCGs willing to participate, as well, those who completed at least one follow-up assessment to be included in the analyses. While we used propensity score adjustments, there are likely residual, unmeasured confounding factors, e.g. changes in care patterns and available therapies between the phases, nurse experience, patient prognosis, that we have not fully accounted for. Third, due to recruitment challenges and high attrition from death, loss to follow-up and withdrawals, we did not reach our sample targets and thus some of the null findings may be due to insufficient power, especially for the FCG measures. Alternatively, the number of multiple comparisons may have also resulted in findings of significance by chance. Fourth, while Kaiser Permanente is a community practice setting, the findings may not fully extend to other settings due to the high level of performance on serious illness care even during the usual care phase, e.g. documentation of advance care planning by 77% of patients and relatively high care experience ratings. Fifth, the data collection at baseline differed between the phases and could have contributed to potential errors or differences in baseline scores. However, we felt the tradeoff was worthwhile as it was important for the clinic PC nurses to obtain those assessments to inform their care plans as would occur in usual practice. Similarly, clinic nurse ratings of their effectiveness with the education sessions may be biased; nevertheless, we found that patients and FCG’s positive ratings triangulated with the nurses’ self-ratings. Finally, the short follow-up time of 3-months resulted in relatively few deaths to confidently compare the quality of end-of-life care or acute care utilization across the two cohorts and will require longer-term follow-up and comparisons with patients who were not enrolled in the study.

Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest that a PC intervention previously tested at a specialized center can be successfully adapted to a community setting to achieve similar, if not better QOL outcomes for patients and FCGs compared to usual care. Despite these positive results, additional modifications to ensure consistent referrals to PC and streamlining routine assessments and patient/FCG education are needed to sustain and extend the PCI beyond the three study sites.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the Kaiser Permanente Southern California palliative care nurses (Loraine Martinez, RN, BSN, Chrissie Mirasol, RN, BSN, and Meesha Land, RN, BSN), physicians (Thomas Cuyegkeng, MD, Karisa Jahn, MD, and Tieu Phung, MD), department administrators (Mandy Gonzalez, RN, Salisha Peters, RN, MSN, Amin Rabiei, and Joseph Tolentino, RN, MBA), and oncology physician leads (Drs. Farah Brassfield, Sohail Saeed, and Candice Ruby) for their contributions to and support of this project.

Funding by the National Institutes of Health, 5R01NR015341-03 and support from the City of Hope Biostatistics Core P30CA033572

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors have a conflict of interest related to this paper to declare.

Clinical Trials.gov registration: NCT02243748

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Huong Q. Nguyen, Department of Research & Evaluation, Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

Nora Ruel, City of Hope Medical Center.

Mayra Macias, Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

Tami Borneman, City of Hope Medical Center.

Melissa Alian, Riverside Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

Mark Becher, Fontana Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

Kathy Lee, Anaheim and Irvine Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

Betty Ferrell, Nursing Research & Education, City of Hope Medical Center.

References

- 1.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen HQ, Cuyegkeng T, Phung TO, et al. Integration of a Palliative Care Intervention into Community Practice for Lung Cancer: A Study Protocol and Lessons Learned with Implementation. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(12):1327–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gidwani R, Nevedal A, Patel M, et al. The Appropriate Provision of Primary Versus Specialist Palliative Care to Cancer Patients: Oncologists' Perspectives. J Palliat Med. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrell B, Sun V, Hurria A, et al. Interdisciplinary Palliative Care for Patients With Lung Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(6):758–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun V, Grant M, Koczywas M, et al. Effectiveness of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention for family caregivers in lung cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(20):3737–3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd SR, Tulsky DS, Kaplan E, Bonomi P. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung cancer. 1995;12(3): 199–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graves KD, Arnold SM, Love CL, Kirsh KL, Moore PG, Passik SD. Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung cancer. 2007;55(2):215–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groff AC, Colla CH, Lee TH. Days Spent at Home - A Patient-Centered Goal and Outcome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(17):1610–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrell BR, Grant M, Chan J, Ahn C, Ferrell BA. The impact of cancer pain education on family caregivers of elderly patients. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(8): 1211–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrell BR, Grant M, Borneman T, Juarez G, ter Veer A. Family caregiving in cancer pain management. J Palliat Med. 1999;2(2):185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13(6):375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schumacher KL, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG. Mutuality and preparedness moderate the effects of caregiving demand on cancer family caregiver outcomes. Nurs Res. 2007;56(6):425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery RV, Stull DE, Borgatta EF. Measurement and the analysis of burden. Res Aging. 1985;7(1): 137–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Block SD, Billings JA. A need for scalable outpatient palliative care interventions. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1699–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carmont SA, Mitchell G, Senior H, Foster M. Systematic review of the effectiveness, barriers and facilitators to general practitioner engagement with specialist secondary services in integrated palliative care. BMJ supportive & palliative care. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malani PN, Widera E. The Promise of Palliative Care: Translating Clinical Trials to Clinical Care. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2090–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella D, Eton DT, Fairclough DL, et al. What is a clinically meaningful change on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) Questionnaire? Results from Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Study 5592. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(3):285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haun MW, Estel S, Rucker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD011129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balboni TA, Fitchett G, Handzo GF, et al. State of the Science of Spirituality and Palliative Care Research Part II: Screening, Assessment, and Interventions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(3):441–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Pirl WF, et al. Effects of Early Integrated Palliative Care on Caregivers of Patients with Lung and Gastrointestinal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The oncologist. 2017;22(12):1528–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs JM, Shaffer KM, Nipp RD, et al. Distress is Interdependent in Patients and Caregivers with Newly Diagnosed Incurable Cancers. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):519–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Mcacmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. Journal of palliative care. 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): a new tool. Journal of palliative care. 1996; 12(1):5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]