ABSTRACT

Background

Women's employment improves household income, and can increase resources available for food expenditure. However, employed women face time constraints that may influence caregiving and infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices. As economic and social trends shift to include more women in the labor force in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), a current understanding of the association between maternal employment and IYCF is needed.

Objective

We investigated the association between maternal employment and IYCF.

Design

Using cross-sectional samples from 50 Demographic and Health Surveys, we investigated the association between maternal employment and 3 indicators of IYCF: exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) among children aged <6 mo (n = 47,340) and minimum diet diversity (MDD) and minimum meal frequency (MMF) (n = 137,208) among children aged 6–23 mo. Mothers were categorized as formally employed, informally employed, or nonemployed. We used meta-analysis to pool associations across all countries and by region.

Results

According to pooled estimates, neither formal [pooled odds ratio (POR) = 0.91; 95% CI: 0.81, 1.03] nor informal employment (POR = 1.05; 95% CI: 0.95, 1.16), compared to nonemployment, was associated with EBF. Children of both formally and informally employed women, compared to children of nonemployed women, had higher odds of meeting MDD (formal POR = 1.47; 95% CI: 1.35, 1.60; informal POR = 1.11; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.20) and MMF (formal POR = 1.18; 95% CI: 1.10, 1.26; informal POR = 1.15; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.24). Sensitivity analyses indicated that compared to nonemployed mothers, the odds of continued breastfeeding at 1 y were lower among formally employed mothers (POR = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.73, 0.98) and higher among informally employed mothers (POR = 1.19; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.40).

Conclusion

Efforts to promote formalized employment among mothers may be an effective method for improving diet diversity and feeding frequency in LMICs. Formally employed mothers may benefit from support for breastfeeding to enable continued breastfeeding through infancy. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03209999.

Keywords: maternal employment, breastfeeding, diet quality, low- and middle-income countries, infant and young child feeding

INTRODUCTION

Established in 2000, the Millennium Development Goals raised global attention to women's employment by promoting women's participation in the labor force as a strategy for improving health and alleviating poverty in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Promotion of women's employment is important for gender equity, women's empowerment, and continued economic development (1). Women's employment can have many positive impacts on the household; for example, earned income from maternal employment may increase household food expenditures (2–5), improve financial stability, and increase investments in human capital (e.g., education) (6, 7). Employed women are likely to spend their earnings on nutrition-enhancing purchases and allocate their income towards their children (8). However, constraints on women's time imposed by employment may pose a potential challenge to caregiving and infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices (2, 3, 9–12). As more women in LMICs are expected to join the labor force in coming decades, it is important to understand the relation between maternal employment and IYCF behaviors and the potential need for additional workplace policies and programs to support the breastfeeding practices of working mothers in LMICs (13).

Prior studies suggest that income earned from maternal employment is associated with the purchase of higher-quality foods (3, 14–16). However, the positive income effects of maternal employment on diet may be offset by negative time allocation effects, and employment potentially changes the opportunity costs of women's time (17–19). Within LMICs, maternal employment has been associated with a lower probability of preparing foods, less time spent on childcare, and a higher probability of purchasing prepared foods (2, 3, 9). Mothers who work are hypothesized to face challenges to exclusive breastfeeding due to separation from their infants and limited breastfeeding support within the workplace. Prior research on maternal employment and breastfeeding is mixed: some studies report that employed women are less likely to exclusively breastfeed (20–24) or breastfeed for a shorter duration of time (25–29), whereas others find a greater likelihood of longer-duration breastfeeding among infants of working mothers (30, 31). Nevertheless, mothers often cite employment as a barrier to exclusive breastfeeding (10, 32). Although most countries have maternity protection legislation, just over half meet the International Labor Organization 14-wk minimum leave with greater inadequacies in the informal work sector (33). Thus, hundreds of millions employed mothers experience inadequate maternity policy coverage, of whom over three-quarters live in Africa and Asia. Within the formal employment sector, 25% of countries have no policy regarding paid breastfeeding breaks, let alone policies such as mandated provision of lactation rooms (33, 34).

We aim to investigate the associations between maternal employment and IYCF practices among 50 LMICs and by world region.

METHODS

Data source and population

We analyzed data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs), which are nationally representative, cross-sectional surveys that use standardized questionnaires and multistage cluster sampling to allow for cross-country comparisons (35).

Our study included DHS datasets that were administered between 2010 and April 2017 and that contained data on women's employment status and indicators of IYCF. Child diet is characterized based on 3 IYCF indicators that play a critical role in child nutritional status from birth to 2 y: exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), minimum diet diversity (MDD), and minimum meal frequency (MMF). Analyses included women who had ≥1 child aged 0–24 mo. If mothers had >1 child, we included the youngest child in the household. Children residing outside the household were excluded given that the likelihood of breastfeeding in this population of children is very low, and since children residing outside the household may be systematically different from children residing within the household.

In models that explored MDD and MMF as the dependent variables, our final analytic sample included 137,208 children aged 6–23 mo from 50 countries. In models that explored EBF as our dependent variable, our final analytic sample included 47,340 children aged 0–5 mo in 49 countries; Chad was excluded from EBF analyses because very few formally employed women (<20) practiced EBF (see Supplemental Figure 1 for study flow chart).

Primary dependent variables

EBF, MDD, and MMF served as our primary dependent variables of interest as prior literature suggests changes in women's income and time, stemming from women's employment, may affect these indicators of IYCF (2, 3, 5, 10, 36, 37). These indicators were created using data from the 24-h recall of foods and food groups available in the DHSs. EBF was modeled as a binary variable, indicating whether infants aged 0–5 mo were fed exclusively with breast milk (38). Children aged 6–23 mo who achieved MDD (a binary variable) were those who received foods from ≥4 of the following 7 food groups: grains, roots and tubers; legumes and nuts; dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese); flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and liver or organ meats); eggs; vitamin A–rich fruits and vegetables; and other fruits and vegetables (38). Breastfed and nonbreastfed children aged 6–23 mo who achieved MMF (a binary variable) were those who received solid, semisolid, or soft foods the minimum number of times or more (38). For breastfed children, the minimum number of times varies with age (2 times if the child is aged 6–8 mo and 3 times if the child is aged 9–23 mo). Nonbreastfed children aged 6–23 mo must be fed ≥4 times/d to meet the MMF indicator.

Primary independent variable

Maternal employment was grouped into 3 categories---formally employed, informally employed, and nonemployed--- which allowed for a unique investigation of the relation between maternal employment and IYCF in LMICs (Supplemental Table 1). We modeled maternal employment as a 3-category variable (formally employed, informally employed, and nonemployed) based on prior research which suggests the following: 1) a large proportion of women in LMICs are engaged in less-formalized employment; and 2) wages earned are >60% lower in the informal sector (39). Women are described as nonemployed because this term includes persons who choose to not seek employment whereas unemployed only describes persons without jobs who are actively seeking employment (40).

Employment type was defined based on 4 indicators: 1) employment status in the last 12 mo (employed, nonemployed); 2) aggregate occupation category (skilled, unskilled); 3) type of earnings (cash only, cash and in-kind, in-kind only, unpaid); and 4) seasonality of employment (all year, seasonal or occasional employment). In-kind earnings include earnings other than money, such as shelter, food, or clothing; the type of in-kind earnings women received were not specified. Formal employment included the following 3 combinations: 1) employed, skilled occupation, cash-only earnings, employed all year; 2) employed, skilled occupation, cash-only earnings, seasonal or occasional employment; and 3) employed, unskilled occupation, cash-only earnings, employed all year. Other employed women were categorized as informally employed (see Supplemental Table 1).

Although there is no standard definition of formal or informal employment, and several definitions of informal employment have been proposed, we aimed to align our definition with recent work that refers to informal employment as employment without legal and social protection—both inside and outside the informal sector (e.g., self-employed informal and informal wage employment) (41). We believe our categorization of employment type is accurate, to the extent feasible using the DHSs, based on several factors. First, using the same definitions of employment type we have previously found that formal employment was associated with higher odds of overweight among women, whereas informal employment was associated with lower odds of overweight (42). The difference in the directionality of the association is noteworthy because it is consistent with prior literature that suggests formally employed workers earn a higher wage (39); we might expect women earning a higher wage to have higher odds of obesity in lower-income countries, because wealthier households within lower-income countries are able to afford and purchase energy-dense or processed foods. Second, the demographic characteristics of our sample suggest that we have correctly classified most women as formally or informally employed. Specifically, formally employed women, compared to informally employed, are more highly educated and tended to reside in wealthier households. Thus, again, this points to the fact that formally employed women are likely earning a higher wage (39) and it is plausible that more educated women are formally employed (compared to informally employed), as these occupations tend to be more skilled (e.g., teacher). Third, among employed women in our sample, 60% are informally employed, which is similar to recent World Bank estimates which suggest ∼65% of individuals employed in LMICs participate in the informal labor market (45). Finally, the relatively high percentage of women employed in our sample (53%), which includes mostly low-income countries, is generally consistent with Goldin's hypothesis (43); this hypothesis indicates that female labor force participation is relatively high in low-income countries (compared to middle-income), where women work out of necessity, mainly in agriculture or less-formalized labor.

Confounders, mediators, effect measure modifiers

We identified confounding factors a priori using a directed acyclic graph, which is a causal diagram used to characterize the relation among variables that influence the primary independent and the dependent variables based on both theorized and documented relations (44). In all models, confounders included maternal education (less than primary school complete, primary school or higher complete), maternal age (years), marital status (married or living together compared to single, widowed, divorced), parity, child morbidity (presence of diarrhea or fever in the last 2 wk), child age (months), and urban or rural status. We aimed to model covariates so that the same specification could be applied in each country and for each outcome. For variables that were in their continuous form in the DHSs (maternal age, child age, parity), we assessed their linearity with the outcomes by specifying disjoint indicator variables. Because variables were approximately linearly associated with the outcomes in most countries, they were retained in their continuous form to minimize the number of observations dropped from the model due to small cell sizes. Marital status and maternal education were dichotomized because there were very few people in some categories (e.g., divorced).

In these cross-sectional data, earned income or wealth was hypothesized as a mediator and on the causal pathway of the employment-IYCF association a priori. Maternal employment would result in increased income or assets, or a combination, and it is plausible that, over a longer period of time, employment could affect household wealth (i.e., accumulation of assets and household income) and, subsequently, IYCF practices. Wealth prior to work force entry (i.e., at time point 0) could be a plausible confounder of the employment-IYCF association; however, the temporality of wealth and employment cannot be established using cross-sectional data. Therefore, wealth was considered a mediator, and not controlled for in these analyses.

We hypothesized that the association between maternal employment and IYCF would vary by countries’ stage in the nutrition transition. Therefore, we explored differences in the country-level associations by log GDP per capita, adjusted for purchasing power parity, a theorized driver of the nutrition transition (45). Data were obtained from the World Development Indicators database, corresponding to the survey year (46). GDP per capita was log transformed to reflect the expected influence of a percentage increase (e.g., 5%), rather than an absolute dollar increase (e.g., $5).

Statistical analysis

We would expect that trends in employment (i.e., the percentage of women in formal compared to informal employment) and dietary quality would both differ depending on countries’ stage of the nutrition transition. Therefore, we aimed to keep samples comparable by selecting countries with a recent DHS (2010–2017) and we allowed for different relations in each country by starting with disaggregate, country-specific estimates. We first employed separate multivariable logistic regression models for each country to test the association between maternal employment and IYCF indicators (EBF, MDD, MMF). In these country-specific models, we utilized sampling weights to account for differential probability of selection and response and Taylor series linearized standard errors accounted for the clustered design of the DHS.

After obtaining disaggregated estimates for each country, coefficients for the employment-EBF, employment-MDD, and employment-MMF associations were entered into a random effects meta-analysis to obtain ORs pooled across all countries and by world region as defined by the World Bank (East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin American and Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa). Random effects meta-analysis, used to generate pooled ORs (PORs), is a 2-stage process involving the estimation of an OR for each country (described above), followed by the calculation of a weighted average across all countries and by world region. By using random effects, we assume that the associations between employment and IYCF may differ by country and/or region.

Country-specific β coefficients were also entered into a random-effects meta-regression to assess whether the associations between employment and IYCF varied by country-level log GDP. Meta-regression is an extension to standard meta-analysis and investigates the extent to which statistical heterogeneity between associations estimated for multiple countries can be related to ≥1 characteristics of the countries (e.g., log GDP) (47). Random-effects meta-regression allows for between-country variance not explained by log GDP. Similar to linear regression, the coefficient can be interpreted as the effect of the association between employment and IYCF per each unit increase in log GDP and estimates how much of the heterogeneity in the association is explained by GDP.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses included modeling several alternative outcomes as follows: 1) continued breastfeeding at 1 y; 2) diet diversity score; and 3) minimum acceptable diet. As an additional sensitivity check, we included a proxy variable for childcare support—living with one’s mother, mother-in-law, or sister (a binary variable). Continued breastfeeding at 1 y, a binary variable, was defined as children aged 12–15 mo who are fed breast milk (38). Diet diversity score, a continuous variable estimated among children aged 6–23 mo, was based on the same 7 foods groups used to calculate MDD (38). For each of the 7 food groups, children received 1 point if any food in the group was consumed (i.e., minimum DDS = 0, maximum DDS = 7). The minimum acceptable diet (MAD) indicator was modeled as a binary variable and was defined as children aged 6–23 mo who achieved a minimum acceptable diet as determined by minimum food frequency, diet diversity, and breastfeeding status (38). α was set to 0.05. Analyses were performed using Stata 14.1 (StataCorp LP). No institutional review board review was obtained given that all analyses used anonymized secondary data.

RESULTS

Across all countries in the sample (n = 50), 22.5% of mothers were formally employed, 31.2% were informally employed, and 46.4% were nonemployed (Table 1). Thus, ∼53% of women in the total sample were either formally or informally employed, consistent with recent World Bank estimates for LMICs (45). Notably, our sample contained a higher proportion of informally employed mothers (60%, n = 43,515 of 73,317 employed women), which is also generally consistent with estimates from the World Bank (45).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics of children participating in selected Demographic and Health Surveys, by employment status1

| Overall | Formally employed | Informally employed | Nonemployed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | (n = 137,208)2 | (n = 29,802)2 | (n = 43,515)2 | (n = 63,891)2 |

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Maternal age, y | 27.7 ± 6.6 | 28.9 ± 6.3 | 28.4 ± 6.9 | 26.8 ± 6.5 |

| ≥Primary education, n (%) | 60,511 (44.8) | 17,789 (58.5) | 13,050 (31.0) | 29,671 (47.3) |

| Parity | 3.4 ± 2.3 | 3.3 ± 2.2 | 3.8 ± 2.5 | 3.1 ± 2.2 |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Child age,3 mo | 14.0 ± 5.1 | 14.3 ± 5.1 | 14.2 ± 5.1 | 13.7 ± 5.0 |

| Exclusively breastfed,3n (%) | 18,130 (40.8) | 3427 (38.0) | 5380 (45.1) | 9322 (39.7) |

| Diet diversity score3 | 2.6 ± 1.7 | 3.0 ± 1.8 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 1.8 |

| Minimum diet diversity,3n (%) | 38,803 (28.7) | 11,480 (37.8) | 9138 (21.7) | 18,185 (29.0) |

| Minimum meal frequency,3n (%) | 62,881 (46.5) | 15,346 (50.5) | 18,121 (43.0) | 29,415 (46.9) |

| Morbidity, n (%) | 57,273 (42.4) | 11,975 (39.4) | 18,814 (44.7) | 26,485 (42.3) |

| Household characteristics | ||||

| Resides in urban area, n (%) | 43,703 (32.3) | 15,375 (50.6) | 6781 (16.1) | 21,546 (34.4) |

| Wealth, n (%) | ||||

| Poorest | 30,451 (22.5) | 4336 (14.3) | 12,761 (30.3) | 13,354 (21.3) |

| Poorer | 29,116 (21.5) | 4950 (16.3) | 11,017 (26.2) | 13,150 (21.1) |

| Middle | 27,590 (20.4) | 5641 (18.6) | 9131 (21.7) | 12,818 (20.5) |

| Rich | 25,888 (19.1) | 7198 (23.7) | 6362 (15.1) | 12,328 (19.7) |

| Richest | 22,183 (16.4) | 8280 (27.2) | 2862 (6.8) | 11,042 (17.6) |

1Values are means ± SDs or n (%). Total sample sizes (overall and by subgroup) are unweighted. Mean ± SD and number of observations (percentage) were estimated using the country-specific sample weight. Characteristics represent our analytic sample for our primary minimum dietary diversity and minimum meal frequency models.

2Type of employment was based on 4 indicators: 1) employment during the last 12 mo (yes, no); 2) aggregate occupation category (skilled, unskilled); 3) type of earnings (cash only, cash and in-kind, in-kind only, unpaid); and 4) seasonality of employment (all year, seasonally, occasionally).

3Exclusive breastfeeding is estimated among children aged <6 mo; dietary diversity score, minimum dietary diversity, and minimum meal frequency are estimated for children aged 6–23 mo; morbidity is calculated for all children in the sample.

Maternal age (mean ± SD) was 27.7 ± 6.6 y, and under half of mothers in the sample (44.8%) had completed a primary level of education or higher. Child age (mean ± SD) was 14.0 ± 5.1 mo. Among children <6 mo, 40.8% were EBF. Among children aged 6–23 mo, 28.7% met their age-specific MDD indicator, whereas 46.5% met the indicator for MMF.

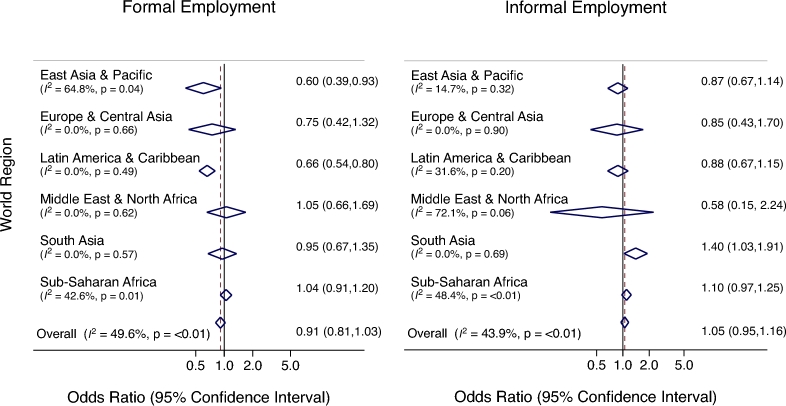

Exclusive breastfeeding among infants 0–5 mo

When pooling estimates across 49 LMICs, formal employment, compared to nonemployment, was not associated with EBF (POR = 0.91; 95% CI: 0.81, 1.03) (Table 2). We observed some differences by region. In East Asia and the Pacific (n = 4 countries) (POR = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.39, 0.93) and Latin America (n = 5 countries) (POR = 0.66; 95% CI: 0.54, 0.80), formal employment was associated with lower odds of EBF (Figure 1).

TABLE 2.

PORs for the relation between formal and informal maternal employment and IYCF indicators1

| POR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive breastfeeding2 | Minimum diet diversity2 | Minimum meal frequency2 | |

| Formal employment3 | 0.91 (0.81, 1.03) | 1.47 (1.35, 1.60) | 1.18 (1.10, 1.26) |

| Informal employment3 | 1.05 (0.95, 1.16) | 1.11 (1.03, 1.20) | 1.15 (1.06, 1.24) |

1Random effects meta-analysis (using the metan command in Stata) was used to generate PORs. The POR represents the weighted average of these statistics across all countries. Models are adjusted for maternal education (less than primary school complete, primary school or higher complete), maternal age (years), marital status (married or living together compared to single, widowed, divorced), parity, morbidity (presence of diarrhea or fever in the last 2 wk), child age (months), within-country urban or rural status. IYCF, infant and young child feeding; POR, pooled odds ratio.

2Exclusive breastfeeding (n = 47,340 in 49 countries) was modeled as a binary variable, indicating whether infants aged 0–5 mo were fed exclusively with breast milk. Children (aged 6–23 mo) who achieved minimum diet diversity (n = 137,208 in 50 countries) were those who received foods from ≥4 of the following 7 food groups: grains, roots, and tubers; legumes and nuts; dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese); flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and liver/organ meats); eggs; vitamin A–rich fruits and vegetables; and other fruits and vegetables. Breastfed and nonbreastfed children (aged 6–23 mo) who achieved minimum meal frequency (n = 137,208 in 50 countries) were those who received solid, semisolid, or soft foods the minimum number of times or more.

3Type of employment was based on 4 indicators: 1) employment during the last 12 mo (yes, no); 2) aggregate occupation category (skilled, unskilled); 3) type of earnings (cash only, cash and in-kind, in-kind only, unpaid); and 4) seasonality of employment (all year, seasonally, occasionally).

FIGURE 1.

Estimates for the association between formal and informal maternal employment and exclusive breastfeeding by world region. Random effects meta-analysis (using the metan command in Stata) was used to generate PORs, comparing formal employment to nonemployment and informal employment to nonemployment, for 49 countries (n = 47,340). The POR represents the weighted average of these statistics across all countries and by region. I2 represents the heterogeneity by region and larger values show increasing heterogeneity. Models are adjusted for maternal education (less than primary school complete, primary school or higher complete), maternal age (years), marital status (married or living together compared to single, widowed, divorced), parity, morbidity (presence of diarrhea or fever in the last 2 wk), child age (months), within-country urban/rural status. Type of employment was based on 4 indicators: 1) employment during the last 12 mo (yes, no); 2) aggregate occupation category (skilled, unskilled); 3) type of earnings (cash only, cash and in-kind, in-kind only, unpaid); and 4) seasonality of employment (all year, seasonally, occasionally). Exclusive breastfeeding was modeled as a binary variable, indicating whether infants aged 0–5 mo were fed exclusively with breast milk. POR, pooled odds ratio.

Overall, informal employment (POR = 1.05; 95% CI: 0.95, 1.16), compared to nonemployment, was not associated with EBF (Table 2). However, there were differences in the informal employment-EBF associations by region. In South Asia (n = 4), informal employment, compared to nonemployment, was significantly associated with higher odds of EBF (POR = 1.40; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.91) (Figure 1).

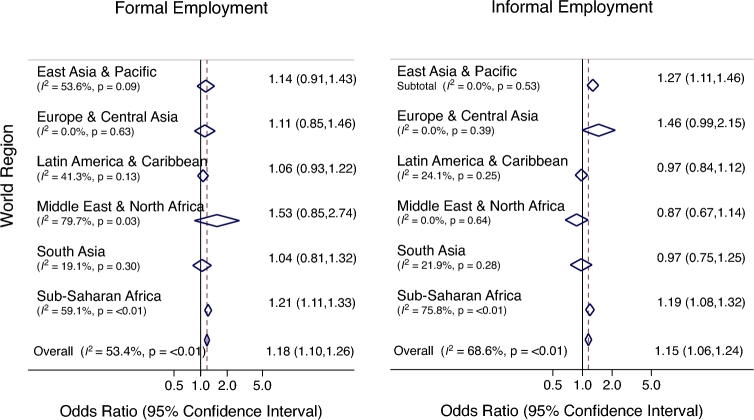

Minimum diet diversity and meal frequency among children 6–23 mo

Regarding dietary diversity, formal employment, compared to nonemployment, was associated with higher odds of children achieving MDD (POR = 1.47; 95% CI: 1.35, 1.60) when data were pooled across 50 LMICs (Table 2). The direction, magnitude, and statistical significance of the association was substantively similar in most world regions, including East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Estimates for the association between formal and informal maternal employment and minimum diet diversity by world region. PORs compare formal employment to nonemployment and informal employment to nonemployment for 50 countries (n = 137,208). Children (aged 6–23 mo) who achieved minimum diet diversity were those who received foods from ≥4 of the following 7 food groups: grains, roots, and tubers; legumes and nuts; dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese); flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry and liver/organ meats); eggs; vitamin A–rich fruits and vegetables; and other fruits and vegetables. POR, pooled odds ratio.

Similarly, children of informally employed women, compared to children of nonemployed women, had higher odds of achieving MDD (POR = 1.11; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.20). This result may largely be explained by the association observed in sub-Saharan Africa (n = 24), where informal employment was significantly associated with higher odds of achieving MDD (POR = 1.19; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.30) (Figure 2). Results were not significant in other world regions.

Regarding the frequency of child meals, formal employment, compared to nonemployment, was also associated with higher odds of children meeting MMF when pooling estimates across all countries (POR = 1.18; 95% CI: 1.10, 1.26) (Table 2). Although the direction and magnitude of the association were similar in most world regions, formal employment was significantly associated with higher odds of meeting MMF only in sub-Saharan Africa (POR = 1.21; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.33) (Figure 3). Informal employment, compared to nonemployment, was also associated with higher odds of children meeting MMF when pooling estimates across the 50 LMICs included in this sample (POR = 1.15; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.24) (Table 2). We observed similar trends in East Asia (POR = 1.27; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.46) and sub-Saharan Africa (POR = 1.19; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.32) where informal employment was significantly associated with higher odds of children meeting MMF.

FIGURE 3.

Estimates for the association between formal and informal maternal employment and minimum meal frequency by world region. PORs compare formal employment to nonemployment and informal employment to nonemployment for 50 countries (n = 137,208). Breastfed and nonbreastfed children (aged 6–23 mo) who achieved minimum meal frequency were those who received solid, semisolid, or soft foods the minimum number of times or more. POR, pooled odds ratio.

Heterogeneity in the employment-IYCF associations by GDP

Neither the associations for employment and EBF nor MDD differed by log GDP (Table 3). However, the associations between both formal and informal employment, compared to nonemployment, and children meeting MMF were lower in countries with a higher GDP (Formal β = –0.08; 95% CI: –0.16, –0.01; Informal β = –0.13; 95% CI: –0.22, –0.04).

TABLE 3.

Meta-regression results for the association between formal and informal maternal employment and IYCF indicators by log-GDP1

| β (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Formal employment2 | Informal employment2 | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding3 | −0.11 (−0.26, 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.16, 0.12)4 |

| Minimum diet diversity3 | −0.07 (−0.18, 0.04) | −0.09 (−0.18, 0.01) |

| Minimum meal frequency3 | −0.08 (−0.16, −0.01) | −0.13 (−0.22, −0.04) |

1β Coefficients were estimated using meta-regression (using the metareg command in Stata). Meta-regression investigates the extent to which statistical heterogeneity between results of multiple countries can be related to log GDP (47). Random-effects meta-regression allows for between-country variance not explained by log GDP. Similar to linear regression, the coefficient can be interpreted as the effect of the association between employment and IYCF per each unit increase in log GDP (i.e., how much of the heterogeneity in the association is explained by GDP). Models are adjusted for maternal education (less than primary school complete, primary school or higher complete), maternal age (years), marital status (married or living together compared to single, widowed, divorced), parity, morbidity (presence of diarrhea or fever in the last 2 wk), child age (months), within-country urban or rural status.

2Type of employment was based on 4 indicators: 1) employment during the last 12 mo (yes, no); 2) occupation category (skilled, unskilled); 3) type of earnings (cash only, cash and in-kind, in-kind only, unpaid); and 4) seasonality of employment (all year, seasonally, occasionally).

3Exclusive breastfeeding was modeled as a binary variable, indicating whether infants aged 0–5 mo were fed exclusively with breast milk (n = 47,340 in 49 countries). Children (aged 6–23 mo) who achieved minimum diet diversity (n = 137,208 in 50 countries) were those who received foods from ≥4 of the following 7 food groups: grains, roots, and tubers; legumes and nuts; dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese); flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and liver/organ meats); eggs; vitamin A–rich fruits and vegetables; and other fruits and vegetables. Breastfed and nonbreastfed children (aged 6–23 mo) who achieved minimum meal frequency (n = 137,208 in 50 countries) were those who received solid, semisolid, or soft foods the minimum number of times or more.

4Excludes Armenia due to small cell sizes.

Sensitivity analyses

Results were similar in magnitude and direction when modeling continued breastfeeding at 1 y (Supplemental Table 2). However, unlike our primary EBF model, formal employment, compared to nonemployment, was significantly associated with lower odds of continued breastfeeding at 1 y (POR = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.73, 0.98) and informal employment, compared to nonemployment, was associated with higher odds of continued breastfeeding at 1 y (POR = 1.19; 95% CI: 1.01,1.40). When including a proxy variable for childcare support, results were unchanged in terms of magnitude, direction, and significance (data not shown).

Results were substantively similar in magnitude, direction, and significance when modeling minimum acceptable diet as the outcome (formal employment POR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.21, 1.48; informal employment POR = 1.13; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.25, Supplemental Table 2). Both formal (pooled β = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.22, 0.34) and informal employment (pooled β = 0.12; 95% CI: 0.07, 0.17), compared to nonemployment, were associated with having a higher diet diversity score (Supplemental Table 2).

DISCUSSION

To improve understanding of the relation between maternal employment and IYCF, this study combined data from a large number of LMICs using current, standardized national surveys. Overall, our findings indicated that neither formal nor informal employment was associated with EBF at 6 mo, but that formal employment was associated with lower odds of continued breastfeeding at 12 mo. Our results indicate that employed mothers, compared to nonemployed mothers, had higher odds of feeding their children with healthful complementary feeding practices, assessed by the indicators MDD and MMF. When comparing associations pooled across all 50 countries, the magnitude of the association between employment and MDD was higher for children of formally employed women and was most consistent in sub-Saharan Africa, where both formal and informal employment were associated with higher odds of meeting both MDD and MMF.

Consistent with some prior literature (20–24), we find that neither formal employment nor informal employment, compared to nonemployment, was associated with EBF among infants <6 mo, overall and in most regions. One possible explanation for this finding is that systemic factors play a larger role in influencing EBF practices, such as sociocultural norms around availability and use of breast milk substitutes, maternity leave duration, and workplace breastfeeding supports (48–50). We did observe some differences by region, specifically that formally employed mothers in East Asia and the Pacific and Latin America and the Caribbean may experience some work-related challenges to EBF through 6 mo. Furthermore, formal employment was significantly associated with lower odds of continued breastfeeding at 1 y. Limited evidence from LMICs suggests that more formalized employment demands longer working hours and offers childcare arrangements that are less flexible, and a recent review highlights the unmet need for workplace supports to encourage breastfeeding among working mothers in LMICs (33). A study in Ghana found that limited flexibility was a factor which decreased breastfeeding adherence in working mothers (48). Similarly, a small study in Nigeria also found that flexibility was a factor and reported that breastfeeding duration was significantly longer for full-time housewives (17.6 mo) compared to women who worked away from home (14.1 mo) (51). On the contrary, informal employment (e.g., street vending, house cleaning) may be somewhat more conducive to successful EBF practices, particularly in South Asia where infants may accompany mothers at work due to flexible work schedules (49). Sensitivity analyses also indicated that informal employment was associated with higher odds of continued breastfeeding at 1 y. In several qualitative studies, mothers often cite employment as a key barrier to continued exclusive breastfeeding (10, 32, 36). This may point to a need for stronger social and workplace supports (e.g., nursing breaks, cold storage for expressed milk) and maternity leave policies that positively support mother's breastfeeding intentions in light of their employment responsibilities, particularly where breastfeeding promotion has declined since 2000 (49). Social supports, such as education from classes or support groups and friends or relatives, have been associated with longer breastfeeding duration in prior studies (52).

Overall, our results suggest that formal employment has a beneficial effect on children's diets across all countries and in most world regions. This is consistent with prior literature indicating that maternal employment specifically, and increased maternal income more broadly, are associated with increased household food expenditures (2–4) and improved dietary quality (16, 53). Mothers are likely to allocate these food purchases towards their children (8). Our results further indicate that the magnitude of the employment-MDD association overall was higher among children of formally employed women, compared to children of informally employed women in East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa, and informal employment was associated with having more diverse diets in sub-Saharan Africa. This may be driven by the fact that children of formally employed women are consuming several higher-quality foods (see Supplemental Table 3). Although both children of formally and informally employed women, compared to children of nonemployed women, had higher odds of consuming animal source foods, the magnitude of the association for formal employment was larger than the analogous association for informal employment. Children of formally employed women also had higher odds of consuming dairy, grains, eggs, fats, and sweets. We hypothesize that smaller increases in income among informally employed women, relative to formally employed women, may elicit different food-purchasing behaviors, as wages in the informal sector employment are lower than wages in the formal sector (39). Nominal increases in income may allow informally employed women to increase their food expenditures somewhat, but not enable them to “trade up” to a wide variety of protein-rich (e.g., dairy, eggs) or energy-dense foods (e.g., fats, sweets) (45). Prior evidence also suggests that substantive dietary changes may not occur until income increases beyond 15% of household expenditures; for example, in a predominantly informally employed sample in Guatemala, employed women reported that some foods (e.g., beef) largely remained unaffordable even when employed (7, 54). Further research is needed to identify the specific pathways (e.g., solely income, exposure to prosocial nutrition ideas) by which employment may improve children's diet quality.

Our study identified that employed mothers also had higher odds of feeding their children according to the minimally recommended frequency of meals per day, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. A very limited literature describes the influence of maternal work on mother's caregiver capabilities and suggests that employed mothers may feel that their work schedules caused their children's feeding schedules to become unregulated (55). We hypothesize that working mothers may be exposed to more prosocial nutrition ideas, support from other working mothers, and potentially nutrition education resulting in a more frequent child feeding schedule. It is also plausible that in multigenerational households, as is particularly common in sub-Saharan Africa, grandmothers or mothers-in-law are in part responsible for meal preparation, thus, meal frequency may not change even if the mother is employed. In one qualitative study, working mothers perceived that their substitute childcare provider, often a family member, provided care similar to the care they themselves provide (7).

Our study is limited by several factors. First, we utilize cross-sectional data, and therefore unmeasured or residual confounding could occur and we cannot make causal inferences; for example, reverse causation may occur if EBF practices influenced women's decision not to work, or having a diet lacking diversity prompted a woman to seek employment. Second, the measures of breastfeeding and children's dietary quality were based on maternal report, which is subject to recall and social desirability bias. Third, countries retained for these analyses may not be representative of other LMICs that no longer participate in the DHS (e.g., upper- and middle-income countries). Fourth, our construction of the informal employment variable may be an under- or overestimate of the informal labor market in LMICs, as a more approximate measure (e.g., social insurance registration) was not available. Moreover, the literature suggests that the informal employment sector is not homogeneous. For example, some literature characterizes informal labor as either voluntary or forced (39), or compares informal self-employment with informal wage employment (41), but we were unable to distinguish between these sectors using the DHSs. Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths that improve upon the existing evidence: 1) we pool associations across 50 countries and by world region for several indicators of IYCF; 2) we uniquely distinguish nonemployed women from formally and informally employed women; and 3) we assess employment, diet, and demographic factors using standardized, nationally representative surveys.

In conclusion, maternal employment is associated with improved complementary feeding practices among children as indicated by diet quality and meal frequency across 50 LMICs and in several regions. Although children of formally employed mothers were not less likely to be breastfed exclusively at <6 mo, they were less likely to be breastfed at 1 y. Given variation in the associations across regions, countries’ stage within the nutrition transition and cultural norms around IYCF likely play a role in these relations. Further research is needed to identify the pathways by which employment may improve child feeding practices and diet quality. As an increasing number of women are expected to join the labor force in LMICs in the coming decades, it may also be important to consider and identify effective intervention strategies and policy-level approaches which support breastfeeding among formally employed mothers in the workplace in LMICs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Tracey Tran for general research support.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows: VMO: developed the research plan, conducted the statistical analysis, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript; and both authors: designed the research, share the primary responsibility for the final content, and read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Notes

Supplemental Tables 1–3 and Supplemental Figure 1 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

Abbreviations: DHS, Demographic and Health Survey; EBF, exclusive breastfeeding; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; LMIC, low- and middle-income country; MDD, minimum diet diversity; MMF, minimum meal frequency; POR, pooled odds ratio.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ruel MT, Alderman H, Maternal and Child Nutrition Study G Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: how can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet 2013;382:536–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Popkin BM. Time allocation of the mother and child nutrition. Ecol Food Nutr 1980;9:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tucker K, Sanjur D. Maternal employment and child nutrition in Panama. Soc Sci Med 1988;26:605–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Popkin BM. Rural women work and child welfare in the Philippines. In: Buvinic M., McGreevey W, editors. Women and poverty in the third world. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1983. p. 157–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mwadime R, Klaver JHW, Hautvast J. Links between non-farm employment and child nutritional status among farming households in rural coastal Kenya. Non-farm employment in rural Kenya: micro-mechanisms influencing food and nutrition of farming households 1996:93 Internet: http://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/fulltext/200353#page=97 (accessed 15 June 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Katz J, West KP Jr, Pradhan EK, Leclerq SC, Khatry SK, Shrestha SR. The impact of a small steady stream of income for women on family health and economic well-being. Glob Public Health 2007;2:35–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oddo VM, Surkan PJ, Hurley KM, Lowery C, Ponce S, Jones-Smith JC. Pathways of the association between maternal employment and weight status among women and children: qualitative findings from Guatemala. Matern Child Nutr 2017;e12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoong J, Rabinovich L, Diepeveen S. The impact of economic resource transfers to women versus men. 2012. Internet http://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP201200154.html (accessed 5 October 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bisgrove EZ, Popkin BM. Does women's work improve their nutrition: evidence from the urban Philippines. Soc Sci Med 1996;43:1475–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hackett KM, Mukta US, Jalal CS, Sellen DW. A qualitative study exploring perceived barriers to infant feeding and caregiving among adolescent girls and young women in rural Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2015;15:771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chaturvedi S, Ramji S, Arora N, Rewal S, Dasgupta R, Deshmukh V. Time-constrained mother and expanding market: emerging model of under-nutrition in India. BMC Public Health 2016;16:632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matare CR, Mbuya MN, Pelto G, Dickin KL, Stoltzfus RJ. Assessing maternal capabilities in the SHINE trial: highlighting a hidden link in the causal pathway to child health. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(Suppl 7):S745–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, Haider BA, Kirkwood B, Morris SS, Sachdev HPS. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet 2008;371:417–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pfeiffer J, Gloyd S, Ramirez Li L. Intrahousehold resource allocation and child growth in Mozambique: an ethnographic case-control study. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mascie-Taylor CG, Marks MK, Goto R, Islam R. Impact of a cash-for-work programme on food consumption and nutrition among women and children facing food insecurity in rural Bangladesh. Bull World Health Org 2010;88:854–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Engle PL. Influences of mothers' and fathers' income on children's nutritional status in Guatemala. Soc Sci Med 1993;37:1303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cawley J, Liu F. Maternal employment and childhood obesity: a search for mechanisms in time use data. Econ Hum Biol 2012;10:352–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Glick P. Women's employment and its relation to children's health and schooling in developing countries: conceptual links, empirical evidence, and policies. Cornell Food and Nutrition Policy Program Working Paper no. 131, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bamji MS, Thimayamma BVS. Impact of women's work on maternal and child nutrition. Ecol Food Nutr 2000;39:13–31. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Komatsu H, Malapit HJL, Theis S. How does women's time in reproductive work and agriculture affect maternal and child nutrition? Evidence from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ghana, Mozambique, and Nepal. IFPRI 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Polineni V, Boralingiah P, Kulkarni P, Manjunath R. A comparative study of breastfeeding practices among working and non-working women attending a tertiary care hospital, Mysuru. Natl J Community Med 2016;7(4):235–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lakati A, Binns C, Stevenson M. The effect of work status on exclusive breastfeeding in Nairobi. Asia Pac J Public Health 2002;14(2):85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dearden KA, Quan LN, Do M, Marsh DR, Pachón H, Schroeder DG, Lang TT. Work outside the home is the primary barrier to exclusive breastfeeding in rural Viet Nam: insights from mothers who exclusively breastfed and worked. Food Nutr Bull 2002;23(4 Suppl 2):99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rasheed S, Frongillo EA, Devine CM, Alam DS, Rasmussen KM. Maternal, infant, and household factors are associated with breast-feeding trajectories during infants' first 6 months of life in Matlab, Bangladesh. J Nutr 2009;139:1582–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hiremath BR, Angadi MM, Sorganvi V. A Cross-sectional study on breast feeding practices in a rural area of north Karnataka. Int J Curr Res Rev 2013;5(21):13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirschman C, Sweet JA. Social background and breastfeeding among American mothers. Soc Biol 1974;21:39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yimyam S, Morrow M, Srisuphan W. Role conflict and rapid socio-economic change: breastfeeding among employed women in Thailand. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:957–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chuang C-H, Chang P-J, Chen Y-C, Hsieh W-S, Hurng B-S, Lin S-J, Chen P-C. Maternal return to work and breastfeeding: a population-based cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:461–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hawkins SS, Griffiths LJ, Dezateux C. The impact of maternal employment on breast-feeding duration in the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr 2007;10:891–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jimeno J. Some factors explaining differences in duration of breastfeeding in a rural province: Bohol Philippines. Tagbilaran City Philippines, Department of Health, Bohol Province, Maternal Child Health/Family Planning Project, March 1978(Research Note No 38):19. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Orwell S, Murray J. Infant feeding and health in Ibadan. J Trop Pediatr Environ Child Health 1974;20:206–19. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Balogun OO, Dagvadorj A, Anigo KM, Ota E, Sasaki S. Factors influencing breastfeeding exclusivity during the first 6 months of life in developing countries: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Matern Child Nutr 2015;11:433–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Lutter CK, Martines JC, Piwoz EG, Richter LM, Victora CG, Group TLBS Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 2016;387:491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Atabay E, Moreno G, Nandi A, Kranz G, Vincent I, Assi T-M, Vaughan Winfrey EM, Earle A, Raub A, Heymann SJ. Facilitating working mothers’ ability to breastfeed: global trends in guaranteeing breastfeeding breaks at work, 1995–2014. J Hum Lact 2015;31:81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. ICF Macro Demographic and Health Surveys: DHS model questionnaires. Calverton, MD: ICF Macro; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nair M, Ariana P, Webster P. Impact of mothers' employment on infant feeding and care: a qualitative study of the experiences of mothers employed through the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004434–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saffari M, Pakpour AH, Chen H. Factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding among Iranian mothers: a longitudinal population-based study. Health Promot Perspect 2017;7:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington DC, USA. World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Günther I, Launov A. Informal employment in developing countries: opportunity or last resort? J Dev Econ 2012;97:88–98. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murphy KM, Topel R. Unemployment and nonemployment. Am Econ Rev 1997;87:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen MA. The informal economy: definitions, theories and policies. Women in informal economy globalizing and organizing. WIEGO Working Paper 2012. Internet http://www.wiego.org/publications/informal-economy-definitions-theories-and-policies (accessed 17 December 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oddo VM, Bleich SN, Pollack KM, Surkan PJ, Mueller NT, Jones-Smith JC. Maternal employment and overweight in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Goldin C. The U-shaped female labor force function in economic development and economic history. Schultz TP, editor. Investment in women's human capital and economic development. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1995. p. 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Textor J, Hardt J, Knuppel S. DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology 2011;22:745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Popkin BM, Du S. Dynamics of the nutrition transition toward the animal foods sector in China and its implications: a worried perspective. J Nutr 2003;133(11 Suppl 2):S3898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. The World Bank Internet: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Thompson SG, Higgins J. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med 2002;21:1559–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dun-Dery EJ, Laar AK. Exclusive breastfeeding among city-dwelling professional working mothers in Ghana. Int Breastfeed J 2016;11:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nkrumah J. Maternal work and exclusive breastfeeding practice: a community based cross-sectional study in Efutu Municipal, Ghana. Int Breastfeed J 2017;12:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thet MM, Khaing EE, Diamond-Smith N, Sudhinaraset M, Oo S, Aung T. Barriers to exclusive breastfeeding in the Ayeyarwaddy region in Myanmar: Qualitative findings from mothers, grandmothers, and husbands. Appetite 2016;96:62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Davies-Adetugbo AA, Ojofeitimi E. Maternal education, breastfeeding behaviours and lactational amenorrhoea: studies among two ethnic communities in Ile Ife, Nigeria. Nutr Health 1996;11:115–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen PG, Johnson LW, Rosenthal MS. Sources of education about breastfeeding and breast pump use: what effect do they have on breastfeeding duration? An analysis of the Infant Feeding Practices Survey II. Matern Child Health J 2012;16:1421–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Blumberg RL. Income under female versus male control. In: Gender, family and the economy: the triple overlap. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Leroy JL, Ruel M, Verhofstadt E. The impact of conditional cash transfer programmes on child nutrition: a review of evidence using a programme theory framework. J Dev Effect 2009;1:103–29. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Roshita A, Schubert E, Whittaker M. Child-care and feeding practices of urban middle class working and non-working Indonesian mothers: a qualitative study of the socio-economic and cultural environment. Matern Child Nutr 2012;8:299–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.