Abstract

BACKGROUND

Subjects with hypertension are frequently obese or insulin resistant, both conditions in which hyperuricemia is common. Obese and insulin-resistant subjects are also known to have blood pressure that is more sensitive to changes in dietary sodium intake. Whether hyperuricemia is a resulting consequence, moderating or contributing factor to the development of hypertension has not been fully evaluated and very few studies have reported interactions between sodium intake and serum uric acid.

METHODS

We performed further analysis of our randomized controlled clinical trials (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry #12609000161224 and #12609000292279) designed to assess the effects of modifying sodium intake on concentrations of serum markers, including uric acid. Uric acid and other variables (including blood pressure, renin, and aldosterone) were measured at baseline and 4 weeks following the commencement of low (60 mmol/day), moderate (150 mmol/day), and high (200–250 mmol/day) dietary sodium intake.

RESULTS

The median aldosterone-to-renin ratio was 1.90 [pg/ml]/[pg/ml] (range 0.10–11.04). Serum uric acid fell significantly in both the moderate and high interventions compared to the low sodium intervention. This pattern of response occurred when all subjects were analyzed, and when normotensive or hypertensive subjects were analyzed alone.

CONCLUSIONS

Although previously reported in hypertensive subjects, these data provide evidence in normotensive subjects of an interaction between dietary sodium intake and serum uric acid. As this interaction is present in the absence of hypertension, it is possible it could play a role in hypertension development, and will need to be considered in future trials of dietary sodium intake.

CLINICAL TRIALS REGISTRATION

The trials were registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry as ACTRN12609000161224 and ACTRN1260.

Keywords: blood pressure, hypertension, sodium, urate, uric acid

Serum uric acid may play a potential role in hypertension. Serum uric acid has long been known to be elevated in subjects with primary hypertension,1 but this was originally thought to be secondary to reduced renal blood flow (common in hypertension), which increases uric acid reabsorption, or to the coexistence of insulin resistance, which is associated with increased reabsorption of uric acid by the kidney.2 Thus, it is not unexpected that increased serum uric acid correlates positively with increased proximal tubular reabsorption of sodium.3 Furthermore, elevations in serum renin also correlate with serum uric acid,4 suggesting that activation of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) might secondarily raise serum uric acid.

Support for a causal role for uric acid in some forms of hypertension, arises from animal studies using a uricase inhibitor to increase serum uric acid, and subsequent development of hypertension.5 In this model, raising serum uric acid was associated with hypertension and an increase in renin expression in the kidney, could be prevented by allopurinol.6 Epidemiological studies have reported that elevated serum uric acid concentrations independently preceded and predicted the development of hypertension, rather than hyperuricemia occurring secondary to hypertension.7 A pilot study also reported that lowering uric acid with allopurinol reduced blood pressure, reduced serum renin activity and systemic vascular resistance in adolescents with new-onset hypertension.8 The results of Mendelian randomization studies investigating the relationship between genetic polymorphisms that predict higher serum uric acid levels and incident hypertension have been largely,9–11 but not completely,12 negative. Thus, the role of uric acid in hypertension remains controversial. Clearly, larger and more definitive trials are needed.

Blood pressure differences between hyperuricemic and normouricemic animals are best observed, when animals are on low sodium diets.5,13 It has been proposed that the mutation in mammalian uricase that occurred during the Miocene may have acted as a “thrifty gene” by raising serum uric acid, that then helped maintain blood pressure during that period when sodium intake was likely low.13 While these later studies suggest that the effects of uric acid on blood pressure may be modulated by salt intake, salt intake may also modulate uric acid levels. For example, infusion of isotonic or hypertonic saline can result in a lowering of serum uric acid with uricosuria.14,15 In contrast, depleting extracellular volume,16 including with the use of diuretics,17 is known to increase serum uric acid.

Given the potential interactions of salt intake and uric acid, it would be useful to know if a high salt diet affects serum uric acid concentration. One might hypothesize that a high intake of dietary sodium would suppress serum uric acid levels, but to our knowledge this has never been fully evaluated. In a randomized controlled trial in hypertensive subjects, we demonstrated an incremental dosing of sodium was associated with a reduction in serum uric acid.18 Combining the results of an additional group of normotensive subjects,19 we have re-analyzed the relationship of salt intake and serum uric acid with changes in the RAS system.

In the first analysis, we evaluated if dietary sodium had the ability to modify serum uric acid concentrations in healthy normotensive individuals. In the second analysis, the association between serum uric acid, aldosterone, renin, and the aldosterone–renin ratio (ARR) in response to dietary sodium intake in normotensive and hypertensive subjects was assessed.

METHODS

Analysis 1: Effect of changing dietary sodium intake on serum uric acid levels

We have previously published results for uric acid in hypertensive subjects.18 The aim of this analysis was to determine changes in uric acid with changes in sodium in normotensive subjects. The study design for the randomized controlled trial of dietary sodium modification in normotensive individuals has previously been published.19 In brief, 25 normotensive volunteers participated in a randomized controlled cross-over intervention study examining dietary sodium modification in adult subjects (>18 years). Normotension was defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) <130mm Hg and the absence of antihypertensive medications. Subjects were excluded if they were known to have pre-existing diabetes, cardiovascular, or kidney disease. Subjects commenced a low sodium diet (60 mmol/day) and following a 2-week run in period were randomized to receive the first of 3 different sodium interventions over a 4-week period: (A) 60 mmol sodium per day, (B) 150 mmol sodium per day, or (C) 200–250 mmol sodium per day. All interventions were administered using a tomato juice vehicle, into which additional sodium was added (or not added) to achieve the interventional level of intake. Data on blood pressure, serum renin and aldosterone, dietary sodium intake, and urinary sodium excretion were collected at baseline and the start and end of each intervention.

In addition to previously reported measurements, data were also collected on changes in serum uric acid at baseline and the start and end of each intervention. Sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine, and uric acid were measured upon collection at Southern Community Laboratories (Dunedin, New Zealand). Additional serum samples were stored at −80 °C for batch analysis at the conclusion of the study. Serum renin and aldosterone were measured at the Endolab Canterbury Health Laboratories, Christchurch, New Zealand. Renin was measured in an antibody trapping assay based on the method of Poulsen20,21 as modified by Nussberger.22 In this assay angiotensin 1 produced by the reaction of serum renin with its endogenous substrate at 37 °C is trapped with excess angiotensin 1 antiserum, protecting the released angiotensin 1 from degradation by angiotensinases present in serum. The mixture is then diluted with radiolabeled angiotensin 1 after 30 minutes and processed as a normal radioimmunoassay. In brief, serum or angiotensin 1 standard (75 µl) were incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes in the presence of 8-hydroxyquinoline (10 µl 0.34M) and excess (10 µl) angiotensin 1 antiserum. After incubation the tubes were diluted with 1 ml of assay buffer containing 10,000 cpm of [125I] angiotensin 1 and kept for 18 hours at 4 °C before separation with the solid phase second antibody reagent Saccell (IDS, Bolton on Tyne, UK). Radioactivity was counted in the pellet after centrifugation and aspiration of the supernatant. Aldosterone was measured by direct radioimmunoassay.23 Aldosterone standard in 100 µl of charcoal stripped serum, or 100 µl of serum sample were mixed with aldosterone antiserum and [125I] aldosterone-3-carboxymethyl oxime in 400 µl of buffer pH 3.6 and incubated for 24 hours at 4 °C. The assay was separated by addition of dextran coated charcoal solution, centrifuged, aspirated, and the charcoal pellet counted in a gamma counter. Changes in electrolytes, serum uric acid, and hormones were analyzed using Stata Statistical Software (version 10; StataCorp LP, TX). To determine if differences in serum uric acid existed between interventions, intention to treat analysis was performed using a mixed model with random effects for participants and likelihood methods. The model accounted for week 0, order, and time for each dependent variable. The results are presented as the mean difference (95% CI) between the treatments for week 0 and week 4. A 2-sided P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Analysis 2: Relationship of serum uric acid with RAS and the ARR

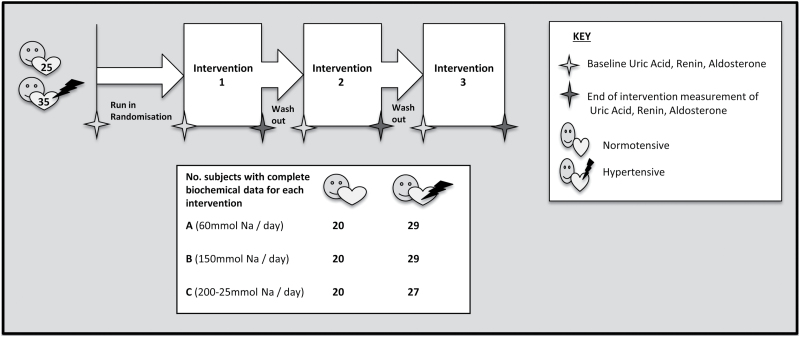

The ARR has previously been linked to central blood pressure.24 To determine if changes in the ARR could modulate serum uric acid concentrations, we pooled data for 60 subjects from our normotensive and hypertensive trials18,19 (25 and 35 subjects, respectively) (Figure 1). Data for hypertensive subjects were extracted from a randomized controlled trial of identical design to that described above, aside from recruiting subjects with SBP >130 mmHg. Methods and baseline characteristics of subjects in this study have been previously published.18 Serum renin, aldosterone, and uric acid were measured upon collection at Southern Community Laboratories (Dunedin, New Zealand). The ARR was calculated for 52 subjects (22 normotensive, 30 hypertensive) with available renin, aldosterone, and uric acid measurements at baseline and week 0 and week 4 of at least one intervention, who did not have an ARR suggestive of primary aldosteronism (>50 pg/ml/pg/ml). The ARR was calculated using the formula described by Trenkel et al.25 and values are presented as [pg/ml]/[pg/ml]. Statistical analyses were undertaken in SPSS Statistics for Mac (version 22; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Baseline characteristics and end of intervention measurements were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Spearman’s Rho was used to determine correlations between urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio (Na:C), aldosterone, renin, the ARR, and uric acid. A 2-sided P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Design of interventions and biochemical data collection.

Ethical approval for both randomized controlled trials was sought from the Lower South Regional Ethics Committee (Project Keys: LRS/06/06/026 and LRS/06/11/057). The trials were registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry as ACTRN12609000161224 and ACTRN12609000292279.

RESULTS

Analysis 1: Effect of changing dietary sodium intake on serum uric acid concentrations in normotensive subjects

Twenty-three subjects completed at least one intervention. Serum uric acid was 0.04 mmol/l (14%) higher during the lowest sodium diet (intervention A), than during the highest sodium diet (intervention C), after adjustment for week 0, order, and time (Table 1). Serum volume only varied by 4% so could not fully explain the changes in serum uric acid concentration. Serum renin and aldosterone were also significantly lower during intervention C, compared to intervention A.

Table 1.

Serum uric acid, electrolytes, and hormones in normotensive subjects

| A | B | C | B–A | C–A | C–B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Adjusted difference (95% CI) | Adjusted difference (95% CI) | Adjusted difference (95% CI) | |

| Serum sodium (mmol/l) | 139 (2) | 139 (2) | 139 (2) | −0.02 (−1.52, 1.47) | 1.25 (−0.46, 2.96) | 1.28 (−0.48, 3.03) |

| Serum potassium (mmol/l) | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.3 (0.3) | 0.12 (−0.09, 0.34) | 0.05 (−0.20, 0.30) | −0.07 (−0.33, 0.18) |

| Serum urea (mmol/l) | 5.2 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.6) | 5.1 (1.1) | 0.61 (−0.15, 1.38) | −0.03 (−0.90, 0.84) | −0.64 (−1.54, 0.25) |

| Serum creatinine (mmol/l) | 79 (9) | 80 (8) | 79 (9) | −0.87 (−5.55, 3.81) | −2.93 (−8.26, 2.40) | −2.06 (−7.57, 3.45) |

| Serum uric acid (mmol/l) | 0.29 (0.07) | 0.28 (0.07) | 0.27 (0.07) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) | −0.04 (−0.06, −0.01)** | −0.03 (0.08, 0.00) |

| Serum renin activity (nmol.l−1.s−1) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.4) | −0.47 (−0.81, −0.14)** | −0.60 (−1.01, −0.18)** | −0.12 (−0.56, 0.31) |

| Serum aldosterone (pmol/l) | 549 (342) | 293 (182) | 297 (161) | −259 (−394, −124)*** | −205 (−384, −27)* | 54 (−132, 239) |

A = 60 mmol sodium/day, B = 150 mmol/day, C = 200–250 mmol/day. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. Serum uric acid, electrolytes, and hormones are reported for week 4 (end of intervention) and as adjusted differences between interventions A, B, and C. Analysis adjusted for week 0, order, and time. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Analysis 2: Relationship of serum uric acid with RAS and the ARR in sodium-loaded normotensive and hypertensive subjects

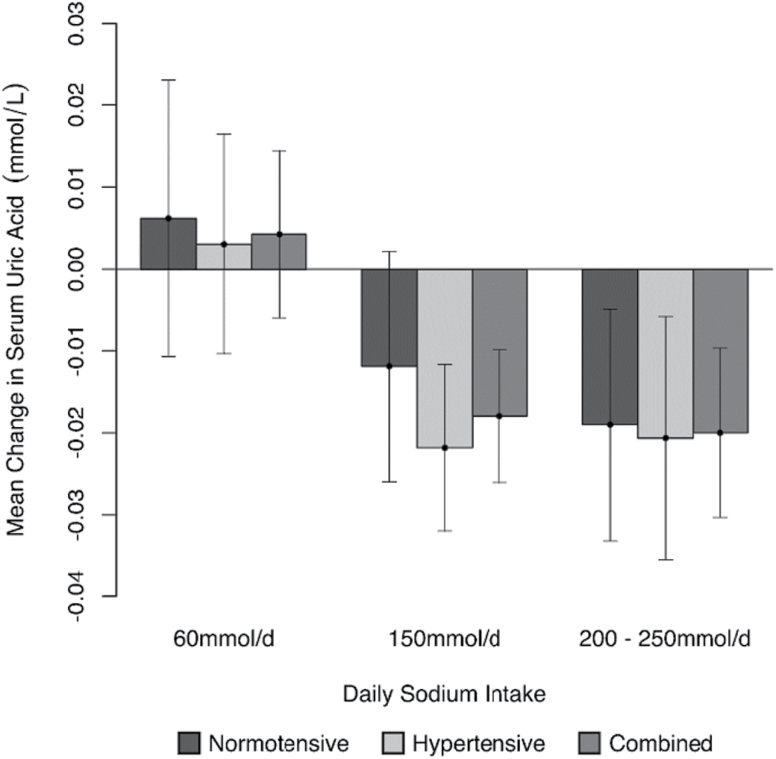

Baseline characteristics from pooled data including both normotensive and hypertensive subjects are displayed in Table 2. Fifty-seven subjects completed at least one intervention. Serum uric acid was maintained at a higher level during intervention A, than during intervention B and C (Figure 2). In the 52 subjects for whom the ARR was calculated, this pattern of response was consistent when all subjects or when normotensive and hypertensive subjects were analyzed alone. Across all measures from all levels of sodium intake (n = 346) the median ARR was 1.90 [pg/ml]/[pg/ml] (range 0.10–11.04). Bivariate correlation to the ARR from all levels of sodium intake (60, 150, and 200–250 mmol/day) identified correlations with serum uric acid of −0.23 (P < 0.001), −0.27 (P = 0.002), and −0.14 (P = 0.044), for all subjects, males, and females, respectively. When the data were analyzed by intervention (A, B, C) this correlation became stronger during the highest level of sodium intake (intervention C) and lost significance during low and moderate intakes of sodium (interventions A and B; Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of normotensive and hypertensive subjects combined

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.40 (10.7) |

| Male (n) | 18 (34.6%) |

| Hypertensive (n) | 30 (56.6%) |

| Medicated (n) | 22 (41.5%) |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 127.40 (15.85) |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 77.25 (10.75) |

| Plasma renin (pg/ml) | 66.56 (47.98) |

| Plasma aldosterone (pg/ml) | 107.17 (48.07) |

| ARR ([pg/ml]/[pg/ml]) | 2.16 (1.35) |

| Serum uric acid (mmol/l) | 0.30 (0.07) |

| Urinary Na:C | 11.31 (7.98) |

Abbreviations: ARR, aldosterone-to-renin ratio; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP Systolic blood pressure; Urinary Na:C, urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio.

Figure 2.

Change in serum uric acid levels 4 weeks after 60 (25 normotensive and 35 hypertensive) individuals consumed 60, 150, or 200–250 mmol sodium per day.

Table 3.

Bivariate correlations to serum uric acid in 52 subjects with available biochemical measurementsa

| Overall | Baseline | Intervention A | Intervention B | Intervention C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary Na:C | −0.254*** | −0.088 | −0.192 | −0.193 | −0.473*** |

| Serum aldosterone | −0.055 | −0.154 | −0.171 | 0.097 | −0.177 |

| Serum renin | 0.237*** | 0.225 | 0.147 | 0.238 | 0.365** |

| ARR | −0.234*** | −0.281* | −0.266 | −0.074 | −0.389** |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.281*** | 0.335* | 0.396** | 0.323* | 0.175 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 0.152** | 0.233 | 0.104 | 0.249 | 0.155 |

A = 60 mmol sodium/day, B = 150 mmol sodium/day, C = 200–250 mmol sodium/day, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. Abbreviations: ARR, aldosterone-to-renin ratio; Urinary Na:C, urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio.

aMeasurements available for baseline as well as week 0 and week 4 of at least one intervention.

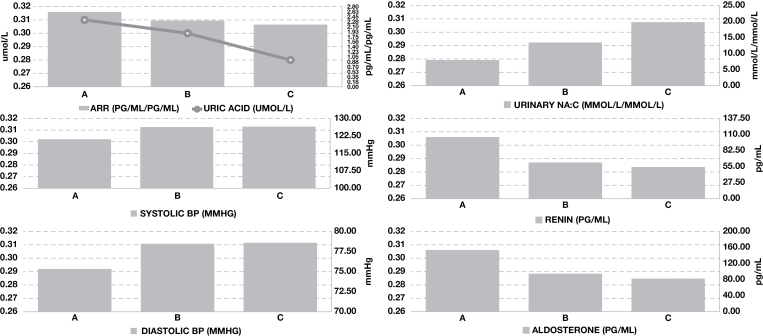

During the lowest level of sodium intake, the urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio decreased, and serum renin and aldosterone increased (Figure 3). Significant correlations were observed between serum uric acid, urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio, and serum renin in all subjects across all levels of sodium intake (Table 3). Analysis of data by intervention again identified that these correlations were greatest during the highest level of sodium intake, and lost significance during lower levels of sodium intake. When the data were split by gender, correlations remained significant in male and female subjects for urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio (r = 0.23, P = 0.019 and r = 0.25, P < 0.001, respectively), but only retained significance in male subjects for serum renin (r = 0.47, P < 0.001; female r = 0.064, P = 0.344). Although no correlation between serum uric acid and serum aldosterone was observed in all subjects across all levels of sodium intake, a significant correlation was observed in male subjects when the data were stratified by gender (r = 0.27, P = 0.03).

Figure 3.

Changes in serum biochemistry, urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio and blood pressure across differing levels of sodium intake in 52 subjects (22 normotensive and 30 hypertensive) for whom the ARR could be calculated. A = 60 mmol sodium/day, B = 150 mmol/day, C = 200–250mmol/day. Abbreviations: ARR, aldosterone-to-renin ratio; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; Urinary NA:C, urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio.

Serum uric acid was also correlated with SBP and DBP in all subjects across all levels of sodium intake, however when the cohort was split by gender and hypertensive status, the correlation between serum uric acid and SBP only remained significant in females (r = 0.22, P = 0.001; males r = 0.029, P = 0.755) and those without hypertension (r = 0.38, P < 0.001; with hypertension r = 0.034, P = 0.641), and no significant correlations were observed for DBP. Analysis by intervention indicated that the relationship between serum uric acid and SBP was strongest at lower levels of sodium intake.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report data from a RCT in normotensive subjects that demonstrates serum uric acid is regulated by changes in dietary sodium intake. Analysis 1 shows that serum uric acid fell significantly during the high sodium diet, with approximately a 14% change in overall serum uric acid. The fall in uric acid was accompanied by increases in serum renin and the urine sodium-to-creatinine ratio. These results are very similar to those observed in hypertensive subjects studied using the same RCT design (Figure 2).18 Analysis 2 evaluated the relationship of serum uric acid to markers of the RAS and blood pressure in a larger cohort that included both normotensive and hypertensive subjects. This analysis demonstrated that serum uric acid correlates with SBP and diastolic blood pressure, with the relationship with SBP being greatest during the low sodium dietary conditions. Serum uric acid also correlated with serum renin and inversely with urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratios, but primarily under high salt conditions. Thus, the primary finding of the analyses presented in this paper is that dietary sodium intake can modulate serum uric acid concentration. It is also apparent from these analyses that the relationship of uric acid with blood pressure is best observed under low dietary sodium conditions, whereas the relationship with serum renin and reduced urine sodium is best observed in subjects exposed to high dietary sodium intake.

Uric acid may represent a physiological response to maintain blood pressure under low sodium dietary conditions, as the effects of uric acid in raising blood pressure of animals is best observed when animals are placed on a low sodium diet.5 It has been postulated that the loss of uricase13 and higher uric acid levels may have aided survival in ancestral primates. This would have assisted to maintain blood pressure as well as amplify the effects of fructose to stimulate fat storage.26,27 Thus, the observation in this study that higher serum uric acid concentrations were maintained with a low dietary sodium intake and that serum uric acid concentrations correlated best with SBP under low sodium conditions is very relevant. Furthermore, the observation that serum uric acid also correlated with a low urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio and with serum renin under high salt conditions suggests the effect of uric acid were present but masked under high salt conditions due to other effects of the high sodium diet on serum volume.

While our analyses show a relationship between dietary sodium intake, uric acid and the RAS, we recognize that this is simply an association, and does not demonstrate that uric acid itself is actually influencing blood pressure. To demonstrate this would require randomizing subjects to uric acid-lowering therapies. Pilot clinical trials in younger subjects with prehypertension or stage I hypertension have been positive, while studies in older subjects tend to show lesser blood pressure effects.28,29 One could view this as consistent with experimental data reporting uric acid effects are best observed in early hypertension. Nevertheless, Mendelian randomization studies have generally failed to confirm a relationship between serum uric acid and blood pressure.11,30 Additionally, it is worth noting some studies suggest uric acid may be beneficial since it can function as an antioxidant.31

The mechanism by which a low sodium diet may maintain higher serum uric acid concentrations and a high sodium diet may lower serum uric acid were not addressed in this study. The mechanism likely involves impaired uric acid clearance, due in part to enhanced uric acid reabsorption in the proximal tubule of the kidney.32,33 It has been proposed that an increased sodium gradient from a lower sodium diet may drive the secondary active transport of uric acid through the primary active transport of sodium.34 Activation of the RAS with a low sodium diet might also lead to impaired clearance of uric acid as suggested by the studies of Ferris and colleagues.35 The nitric oxide system can be impaired during periods of sodium deprivation and may reduce renal blood flow leading to transient rises in serum uric acid36 and likewise uric acid may also reduce nitric oxide bioavailability.37 As well established, a reduced nitric oxide profile reduces vascular blood flow in hypotensive states and following exposure to a low sodium diet.36 Taken together, several mechanisms may be involved in how changes in sodium intake influence serum uric acid levels.

In conclusion, modulating dietary sodium intake does have an effect on serum uric acid, with higher levels in low sodium conditions and with lower uric acid levels in high sodium dietary conditions. Whether this is a physiological response to help maintain BP in low sodium environments or reduce the effects of high salt diet on blood pressure will require further study.

CONCLUSION

Reducing sodium to a level of 60 mmol/day or below may lead to higher uric acid concentrations and transiently increase blood pressure in subjects with normal blood pressure as well as in those with prehypertension and hypertension (though the long-term benefit of sodium restriction may counterbalance this and lead to a slow reduction independent of uric acid). In those with other chronic disease this response system may lead to further exacerbation of those pathological states posing an additional clinical risk, however that is yet to be demonstrated. Further research is required to explore the role of uric acid within intracellular and extracellular systems and its potential modulation by dietary sodium intake.

DISCLOSURE

A.S.T. received a PhD scholarship from the New Zealand Dietetic Association. Funding for this scholarship was provided to the New Zealand Dietetic Association by Unilever Australia. A.S.T. and her co-authors retained independent control of all data and Unilever had no input into the design, conduct or reporting of these studies. R.J.J. has several patents and patent applications related to uric acid and fructose and their role in hypertension and metabolic disease. He is also on the Scientific Board of Amway, and is a member of a startup company, Colorado Research Partners LLC that is developing inhibitors of fructose metabolism. The remaining authors declared no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The National Heart Foundation (New Zealand) and The HS and JC Anderson Charitable Trust (New Zealand) funded the studies used in this analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cannon PJ, Stason WB, Demartini FE, Sommers SC, Laragh JH. Hyperuricemia in primary and renal hypertension. N Engl J Med 1966; 275:457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeFronzo RA. The effect of insulin on renal sodium metabolism. A review with clinical implications. Diabetologia 1981; 21:165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cappuccio FP, Strazzullo P, Farinaro E, Trevisan M. Uric acid metabolism and tubular sodium handling. Results from a population-based study. JAMA 1993; 270:354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saito I, Saruta T, Kondo K, Nakamura R, Oguro T, Yamagami K, Ozawa Y, Kato E. Serum uric acid and the renin-angiotensin system in hypertension. J Am Geriatr Soc 1978; 26:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mazzali M, Hughes J, Kim YG, Jefferson JA, Kang DH, Gordon KL, Lan HY, Kivlighn S, Johnson RJ. Elevated uric acid increases blood pressure in the rat by a novel crystal-independent mechanism. Hypertension 2001; 38:1101–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mazzali M, Kanellis J, Han L, Feng L, Xia YY, Chen Q, Kang DH, Gordon KL, Watanabe S, Nakagawa T, Lan HY, Johnson RJ. Hyperuricemia induces a primary renal arteriolopathy in rats by a blood pressure-independent mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2002; 282:F991–F997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grayson PC, Kim SY, LaValley M, Choi HK. Hyperuricemia and incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011; 63:102–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feig DI, Soletsky B, Johnson RJ. Effect of allopurinol on blood pressure of adolescents with newly diagnosed essential hypertension: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008; 300:924–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levy D, Ehret GB, Rice K, Verwoert GC, Launer LJ, Dehghan A, Glazer NL, Morrison AC, Johnson AD, Aspelund T, Aulchenko Y, Lumley T, Köttgen A, Vasan RS, Rivadeneira F, Eiriksdottir G, Guo X, Arking DE, Mitchell GF, Mattace-Raso FU, Smith AV, Taylor K, Scharpf RB, Hwang SJ, Sijbrands EJ, Bis J, Harris TB, Ganesh SK, O’Donnell CJ, Hofman A, Rotter JI, Coresh J, Benjamin EJ, Uitterlinden AG, Heiss G, Fox CS, Witteman JC, Boerwinkle E, Wang TJ, Gudnason V, Larson MG, Chakravarti A, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Genet 2009; 41:677–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palmer TM, Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Davey Smith G, Lawlor DA, Timpson NJ. Association of plasma uric acid with ischaemic heart disease and blood pressure: mendelian randomisation analysis of two large cohorts. BMJ 2013; 347:f4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang Q, Köttgen A, Dehghan A, Smith AV, Glazer NL, Chen MH, Chasman DI, Aspelund T, Eiriksdottir G, Harris TB, Launer L, Nalls M, Hernandez D, Arking DE, Boerwinkle E, Grove ML, Li M, Linda Kao WH, Chonchol M, Haritunians T, Li G, Lumley T, Psaty BM, Shlipak M, Hwang SJ, Larson MG, O’Donnell CJ, Upadhyay A, van Duijn CM, Hofman A, Rivadeneira F, Stricker B, Uitterlinden AG, Paré G, Parker AN, Ridker PM, Siscovick DS, Gudnason V, Witteman JC, Fox CS, Coresh J. Multiple genetic loci influence serum urate levels and their relationship with gout and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2010; 3:523–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mallamaci F, Testa A, Leonardis D, Tripepi R, Pisano A, Spoto B, Sanguedolce MC, Parlongo RM, Tripepi G, Zoccali C. A polymorphism in the major gene regulating serum uric acid associates with clinic SBP and the white-coat effect in a family-based study. J Hypertens. 2014; 32:1621–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Watanabe S, Kang DH, Feng L, Nakagawa T, Kanellis J, Lan H, Mazzali M, Johnson RJ. Uric acid, hominoid evolution, and the pathogenesis of salt-sensitivity. Hypertension 2002; 40:355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Steele TH. Evidence for altered renal urate reabsorption during changes in volume of the extracellular fluid. J Lab Clin Med 1969; 74:288–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cannon PJ, Svahn DS, Demartini FE. The influence of hypertonic saline infusions upon the fractional reabsorption of urate and other ions in normal and hypertensive man. Circulation 1970; 41:97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weinman EJ, Eknoyan G, Suki WN. The influence of the extracellular fluid volume on the tubular reabsorption of uric acid. J Clin Invest 1975; 55:283–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Steele TH, Oppenheimer S. Factors affecting urate excretion following diuretic administration in man. Am J Med 1969; 47:564–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Todd AS, Macginley RJ, Schollum JB, Johnson RJ, Williams SM, Sutherland WH, Mann JI, Walker RJ. Dietary salt loading impairs arterial vascular reactivity. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91:557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Todd AS, Macginley RJ, Schollum JB, Williams SM, Sutherland WH, Mann JI, Walker RJ. Dietary sodium loading in normotensive healthy volunteers does not increase arterial vascular reactivity or blood pressure. Nephrology (Carlton) 2012; 17:249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Poulsen K. Simplified method for radioimmunoassay of enzyme systems. Application on the human renin-angiotensin system. J Lab Clin Med 1971; 78:309–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Poulsen K, Jorgensen J. An easy radioimmunological microassay of renin activity, concentration and substrate in human and animal plasma and tissues based on angiotensin I trapping by antibody. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1974; 39:816–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nussberger J, Fasanella d’Amore T, Porchet M, Waeber B, Brunner DB, Brunner HR, Kler L, Brown AN, Francis RJ. Repeated administration of the converting enzyme inhibitor cilazapril to normal volunteers. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1987; 9:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lun S, Espiner EA, Nicholls MG, Yandle TG. A direct radioimmunoassay for aldosterone in plasma. Clin Chem 1983; 29:268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tomaschitz A, Maerz W, Pilz S, Ritz E, Scharnagl H, Renner W, Boehm BO, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Weihrauch G, Dobnig H. Aldosterone/renin ratio determines peripheral and central blood pressure values over a broad range. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55:2171–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Trenkel S, Seifarth C, Schobel H, Hahn EG, Hensen J. Ratio of serum aldosterone to plasma renin concentration in essential hypertension and primary aldosteronism. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2002; 110:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson RJ, Andrews P. The fat gene: A genetic mutation in prehistoric apes may underlie today’s pandemic of obesity and diabetes. Sci Am 2015; 313:64–69. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kratzer JT, Lanaspa MA, Murphy MN, Cicerchi C, Graves CL, Tipton PA, Ortlund EA, Johnson RJ, Gaucher EA. Evolutionary history and metabolic insights of ancient mammalian uricases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111:3763–3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soletsky B, Feig DI. Uric acid reduction rectifies prehypertension in obese adolescents. Hypertension 2012; 60:1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgins P, Walters MR, Murray HM, McArthur K, McConnachie A, Lees KR, Dawson J. Allopurinol reduces brachial and central blood pressure, and carotid intima-media thickness progression after ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack: a randomised controlled trial. Heart 2014; 100:1085–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Köttgen A, Albrecht E, Teumer A, Vitart V, Krumsiek J, Hundertmark C, Pistis G, Ruggiero D, O’Seaghdha CM, Haller T, Yang Q, Tanaka T, Johnson AD, Kutalik Z, Smith AV, Shi J, Struchalin M, Middelberg RP, Brown MJ, Gaffo AL, Pirastu N, Li G, Hayward C, Zemunik T, Huffman J, Yengo L, Zhao JH, Demirkan A, Feitosa MF, Liu X, Malerba G, Lopez LM, van der Harst P, Li X, Kleber ME, Hicks AA, Nolte IM, Johansson A, Murgia F, Wild SH, Bakker SJ, Peden JF, Dehghan A, Steri M, Tenesa A, Lagou V, Salo P, Mangino M, Rose LM, Lehtimäki T, Woodward OM, Okada Y, Tin A, Müller C, Oldmeadow C, Putku M, Czamara D, Kraft P, Frogheri L, Thun GA, Grotevendt A, Gislason GK, Harris TB, Launer LJ, McArdle P, Shuldiner AR, Boerwinkle E, Coresh J, Schmidt H, Schallert M, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Kubo M, Nakamura Y, Tanaka T, Munroe PB, Samani NJ, Jacobs DR Jr, Liu K, D’Adamo P, Ulivi S, Rotter JI, Psaty BM, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Campbell S, Devuyst O, Navarro P, Kolcic I, Hastie N, Balkau B, Froguel P, Esko T, Salumets A, Khaw KT, Langenberg C, Wareham NJ, Isaacs A, Kraja A, Zhang Q, Wild PS, Scott RJ, Holliday EG, Org E, Viigimaa M, Bandinelli S, Metter JE, Lupo A, Trabetti E, Sorice R, Döring A, Lattka E, Strauch K, Theis F, Waldenberger M, Wichmann HE, Davies G, Gow AJ, Bruinenberg M, Stolk RP, Kooner JS, Zhang W, Winkelmann BR, Boehm BO, Lucae S, Penninx BW, Smit JH, Curhan G, Mudgal P, Plenge RM, Portas L, Persico I, Kirin M, Wilson JF, Mateo Leach I, van Gilst WH, Goel A, Ongen H, Hofman A, Rivadeneira F, Uitterlinden AG, Imboden M, von Eckardstein A, Cucca F, Nagaraja R, Piras MG, Nauck M, Schurmann C, Budde K, Ernst F, Farrington SM, Theodoratou E, Prokopenko I, Stumvoll M, Jula A, Perola M, Salomaa V, Shin SY, Spector TD, Sala C, Ridker PM, Kähönen M, Viikari J, Hengstenberg C, Nelson CP, Meschia JF, Nalls MA, Sharma P, Singleton AB, Kamatani N, Zeller T, Burnier M, Attia J, Laan M, Klopp N, Hillege HL, Kloiber S, Choi H, Pirastu M, Tore S, Probst-Hensch NM, Völzke H, Gudnason V, Parsa A, Schmidt R, Whitfield JB, Fornage M, Gasparini P, Siscovick DS, Polašek O, Campbell H, Rudan I, Bouatia-Naji N, Metspalu A, Loos RJ, van Duijn CM, Borecki IB, Ferrucci L, Gambaro G, Deary IJ, Wolffenbuttel BH, Chambers JC, März W, Pramstaller PP, Snieder H, Gyllensten U, Wright AF, Navis G, Watkins H, Witteman JC, Sanna S, Schipf S, Dunlop MG, Tönjes A, Ripatti S, Soranzo N, Toniolo D, Chasman DI, Raitakari O, Kao WH, Ciullo M, Fox CS, Caulfield M, Bochud M, Gieger C; LifeLines Cohort Study; CARDIoGRAM Consortium; DIAGRAM Consortium; ICBP Consortium; MAGIC Consortium Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nat Genet 2013; 45:145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Hochstein P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1981; 78:6858–6862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Del Río A, Rodríguez-Villamil JL. Metabolic effects of strict salt restriction in essential hypertensive patients. J Intern Med 1993; 233:409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Egan BM, Weder AB, Petrin J, Hoffman RG. Neurohumoral and metabolic effects of short-term dietary NaCl restriction in men. Relationship to salt-sensitivity status. Am J Hypertens 1991; 4:416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bobulescu IA, Moe OW. Renal transport of uric acid: evolving concepts and uncertainties. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2012; 19:358–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ferris TF, Gorden P. Effect of angiotensin and norepinephrine upon urate clearance in man. Am J Med 1968; 44:359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maxwell AJ, Bruinsma KA. Uric acid is closely linked to vascular nitric oxide activity. Evidence for mechanism of association with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38:1850–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Khosla UM, Zharikov S, Finch JL, Nakagawa T, Roncal C, Mu W, Krotova K, Block ER, Prabhakar S, Johnson RJ. Hyperuricemia induces endothelial dysfunction. Kidney Int 2005; 67:1739–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]