Abstract

The individual- and population-level impact of household tuberculosis exposure on transmission is unclear but may have implications for the effectiveness and implementation of control interventions. We systematically searched for and included studies in which latent tuberculosis infection was assessed in 2 groups: children exposed and unexposed to a household member with tuberculosis. We also extracted data on the smear and culture status of index cases, the age and bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination status of contacts, and study design characteristics. Of 6,176 citations identified from our search strategy, 26 studies (13,999 children with household exposure to tuberculosis and 174,097 children without) from 1929–2015 met inclusion criteria. Exposed children were 3.79 (95% confidence interval (CI): 3.01, 4.78) times more likely to be infected than were their community counterparts. Metaregression demonstrated higher infection among children aged 0–4 years of age compared with children aged 10–14 years (ratio of odds ratios = 2.24, 95% CI: 1.43, 3.51) and among smear-positive versus smear-negative index cases (ratio of odds ratios = 5.45, 95% CI: 3.43, 8.64). At the population level, we estimated that a small proportion (<20%) of transmission was attributable to household exposure. Our results suggest that targeting tuberculosis prevention efforts to household contacts is highly effective. However, a large proportion of transmission at the population level may occur outside the household.

Keywords: contact tracing, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, recent transmission, systematic review, tuberculosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is acquired predominantly through sharing air space with an individual who has active tuberculosis and inhaling droplet aerosols produced by that person. The vast majority of those infected are from impoverished populations in developing countries (1, 2). The elimination of tuberculosis is not possible without a concerted effort to prevent the spread of the disease. Current control measures, predominately passive case-finding of diseased cases, are lowering global tuberculosis incidence rates by approximately 1% per year (3, 4). This level of reduction in new cases of tuberculosis is, however, lower than anticipated, despite renewed efforts and increased resources (3, 4). This modest improvement has led to calls for additional epidemiologic information that can assist in the development of programmatic measures supplementary to current tuberculosis control (5–9). Targeting locations where tuberculosis is likely to spread may open up entry points for interrupting transmission (6, 10). However, defining where transmission is more likely to occur needs further work in order to inform and target resources in future tuberculosis prevention efforts (10–13).

The spread of M. tuberculosis has long been hypothesized to occur more often in the household than in the community (14). However, molecular epidemiologic studies implemented between the late 1990s and early 2000s have not consistently shown this (11, 13, 15). In South Africa, investigators in several studies have found that more than 80% of total transmission was attributable to casual contact or community exposures (12, 16–18). Conversely, results of recent studies in Uganda and South Africa have suggested that M. tuberculosis infection and disease is more likely across all ages in households than among community members (11, 15).

To address this knowledge gap, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the balance of M. tuberculosis transmission among children between household exposure and community exposures to index cases. We calculated the odds of latent tuberculosis infection among studies with children in household contact with a person with tuberculosis and a community control group with no such exposure. In addition, we estimated the population attributable fraction in studies that randomly sampled from the general population in order to quantify at the population level the proportion of new latent tuberculosis infections due to household exposure to an individual with tuberculosis disease.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted a systematic review of studies that included children 0–14 years of age both as household contacts of a person with tuberculosis and as members of households in the community without known household contact with active tuberculosis. In choosing children as the primary focus of this review, we made 3 assumptions based on the epidemiology of tuberculosis. First, children are a reasonable proxy for recent tuberculosis transmission due to their young age (19). Young children are often used when conducting large tuberculin surveys measuring the annual risk of infection, and these rates are often generalized to the community at large (20). Because the incubation period of tuberculosis is variable and can last years (21, 22), using adults to measure household transmission may create a selection bias that would skew any estimate of transmission to a higher rate. Second, we assumed that an infected child living in a household with a person with tuberculosis was most likely to have been infected through contact with the index case and therefore represents household transmission (23, 24). Third, we assumed that an infected child living in a household free of tuberculosis disease must have contracted the infection from outside the household (25).

Literature search

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement for the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Web Appendix 1, available at http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/). We first searched the literature for systematic reviews investigating M. tuberculosis infection in household contact and community control groups among children. None were found. There are 4 systematic reviews on contact evaluations, but none included control groups (26–29). We then aimed to compile all studies investigating 2 groups: children in household contact with a person with tuberculosis and children in households without known household exposure.

We searched journal articles of any study design in PubMed (MEDLINE), Web of Science, BIOSIS, and Embase electronic databases. The search approach was conducted with the help of a librarian database consultant and was updated in October 2014. Keywords in these database searches included tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, tuberculin, contact*, transmission, childhood contact, and household contact (full search strategies are detailed in Web Appendix 2). We did not restrict articles by publication date, and we included articles in English and Spanish. The references of multiple reviews, both systematic and descriptive, were also searched and evaluated for eligibility (19, 26–28, 30, 31). We hand searched the table of contents of the following journals: International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Tubercle and Lung Disease, and American Review of Respiratory Disease. We also searched online abstract books from the Union World Conference on Lung Health (2004–2013). Dissertations and conference abstracts were included for collation if eligible. Corresponding authors of journal articles were contacted for additional data if a study met eligibility criteria but did not stratify by age.

After the search and exclusion of duplicate articles, 2 authors independently screened articles by title, abstract, and text for full review and inclusion in the study. If reviewers disagreed about including an article after a screening, a third author (C.C.W.) determined the eligibility of an article for full review.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed and piloted (Web Table 1). Using this form, 2 authors independently extracted all data from eligible studies and then compared results. Again, differences in data points were resolved by a third author (C.C.W.). From each article, we collected information on the year of publication and implementation, definition used for latent infection, study design, and study setting. Characteristics extracted from index cases included method of diagnosis, total number of cases found in household, human immunodeficiency virus status, and smear grade. From contacts and controls, we collated information on age, number with latent tuberculosis, bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination status, proximity to the index case, and matching characteristics between groups. We also collected national tuberculosis prevalence data from World Health Organization databases for each study conducted after 1990 as a proxy for local tuberculosis rates (32). Studies were classified into income levels using the World Bank definitions (high-, middle-, and low-income countries) as of 2015 (http://data.worldbank.org/news/2015-country-classifications). Additional data on methods and results included in each study were also extracted when available in order to compare studies (Web Tables 2–4).

Definition of key terms

Tuberculosis cases in the household were considered source cases and were eligible if diagnosis was confirmed either bacteriologically (positive on sputum smear or culture) or radiographically. Definition of household varied among the studies. We used each study's definition of household. Community controls were defined as a randomly selected household without household exposure to microbiological or radiologically confirmed tuberculosis and matched to contacts by age and location.

Studies using the tuberculin skin test to diagnose latent tuberculosis infection were included. In most studies, the criterion for a positive skin test was an induration of ≥10 millimeters when read 48–72 hours after injection. Other criteria for a positive test were used; an induration of 5 millimeters and of 8 millimeters were used once each, and a 2-step process of diagnosis was used in a large trial from India (33). Five studies did not specify the criteria for a positive tuberculin skin test but were included in the analysis because they stipulated whether subjects had either a positive or negative skin test. One study defined a positive tuberculin skin test as an induration of ≥5 millimeters in children living with human immunodeficiency virus, and these results were classified as positive as defined in this study (34). One study using the Heaf test was included (35); a grade of 3 or 4 was considered a positive test in this study. Among studies that measured latent infection rates with both tuberculin skin tests and interferon-gamma assays, results from tuberculin skin tests were selected and extracted for analysis. No studies measured latent tuberculosis in both household-contact and community-control groups solely with interferon-gamma assays.

Statistical analysis and heterogeneity

We estimated the odds ratios for infection in the household compared with the community for each study then combined these odds ratios using a random-effects model. A random-effects model with DerSimonian and Laird weights, equalizing the weight of the studies to the pooled estimate, was used because of the high level of heterogeneity found in the odds ratio estimates among studies (36). Two-sided P values and 95% confidence intervals were used to assess statistical significance in all models, and the I2 statistic was used to evaluate heterogeneity between studies (37). We stratified the analysis by prespecified characteristics of the chosen studies and then used random-effects univariable and multivariable metaregression to calculate the ratio of odds ratios and investigate causes of heterogeneity. Variables were chosen for inclusion in the multivariable model by use of the coefficient of determination, or adjusted R2 statistic, which represents the proportion of between-study variance explained by the model. The adjusted R2 statistic was estimated by use of the restricted maximum likelihood, and the model that explained the most between-study variance was chosen. Stata, version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas), was used to perform all analyses; the metan command was used to create forest plots, and the metareg command was used to perform metaregression.

We calculated the population attributable fraction of household exposure to a person with tuberculosis. The population attributable fraction expresses the proportion of new tuberculosis infections that would be eliminated had transmission not occurred or was preempted in the household. The population attributable fraction was estimated only from studies where the control population was taken as a random sample of the community instead of purposive, neighborhood controls. Contact investigations with neighborhood control groups may overestimate the proportion of exposed individuals in a population in situations where tuberculosis disease, and hence transmission, is clustered. Therefore, we used only studies that randomly sampled the general population and calculated prevalence ratios for these studies. The following formula was used to ascertain the population attributable fraction (18, 38, 39):

where Pcases is the prevalence of exposure to household contact among cases and RR is the relative risk, represented here by the prevalence ratio. We calculated Wald confidence intervals that take into account the uncertainty around both the prevalence ratio and the prevalence of household exposure among cases (40).

Various sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess potential bias, including comparing crude and adjusted odds ratios when provided (Web Material), stratification by study design, and comparing studies from various time periods. We assessed publication bias through the Harbord test and by inspecting funnel plot symmetry (41).

RESULTS

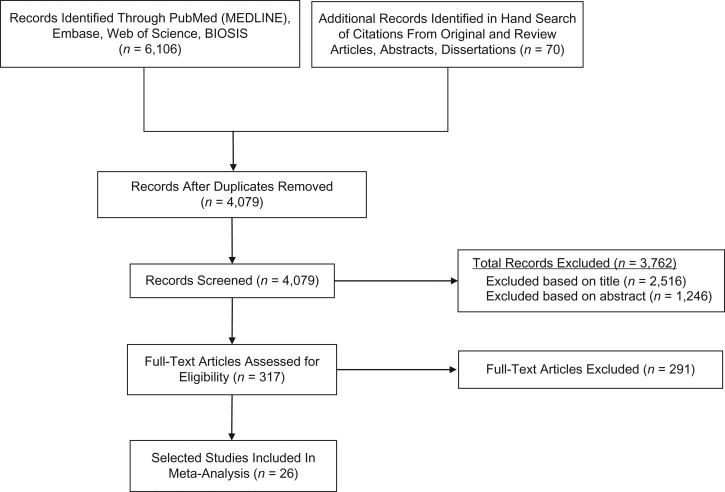

From our database searches we found a total of 4,079 original titles, of which 26 studies (15, 25, 33–35, 42–62) met eligibility requirements and were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1, Web Table 5). The mean number of household contacts and community controls per study was 538 (range, 16–3,191) and 6,696 (range, 18–106,717), respectively. The study designs included 16 case-control studies, 9 cross-sectional studies, and 1 cross-sectional, secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial at baseline (33) (Table 1). There were 10 studies from Africa, 3 from Europe, 6 from the Americas, and 7 from Asia. Fourteen studies had sputum smear–positive index cases; 3 studies contained smear-negative, culture-positive cases; and 5 studies contained index cases who were both smear- and culture-negative. Four studies gave information on acid-fast bacilli smear grade (+1, +2, +3).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for search and selection of 26 included studies, for a meta-analysis of the assessment of latent tuberculosis infection among children who were exposed to tuberculosis in the household and children who were not, published during 1929–2015.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 26 Selected Studies Measuring Latent Tuberculosis in Children Exposed and Unexposed to Tuberculosis in the Household, 1929–2015

| First Author, Yeara (Reference No.) | Definition of LTBIb | Age Range, years | Study Design | Country | Household Contacts | Community Controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Contactsc | % Yieldd | No. of Controlsc | % Yieldd | |||||

| Almeida, 1998 (42) | >10 | 0–14 | Case-control | Brazil | 141 | 47.5 | 506 | 3.6 |

| Blahd, 1946 (43) | NP | 0–2 | Case-control | United States | 143 | 22.4 | 3,589 | 3.7 |

| Brailey, 1928–1937 (61) | NP | 0–14 | Case-control | United States | 789 | 66.3 | 111 | 34.2 |

| Den Boon, 2002 (44) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Cross-sectional | South Africa | 401 | 44.6 | 943 | 26.8 |

| Dogra, 2004–2005 (45) | ≥10 | 1–12 | Cross-sectional | India | 16 | 18.8 | 89 | 7.9 |

| Dow, 1931 (46) | NP | 0–14 | Cross-sectional | United Kingdom | 279 | 62.4 | 724 | 35.6 |

| Gilpin, 1984 (35) | ≥3 | 0–14 | Case-control | South Africa | 80 | 30.0 | 94 | 12.8 |

| Gustafson, 1999–2000 (47) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Case-control | Guinea-Bissau | 482 | 27.8 | 541 | 10.9 |

| Hill, 2002–2004 (48) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Case-control | The Gambia | 255 | 26.6 | 18 | 5.5 |

| Hoa, 2006–2007 (62) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Cross-sectional | Vietnam | 189 | 27.0 | 21,055 | 17.6 |

| Hossain, 2007–2009 (57) | ≥8 | 5–14 | Cross-sectional | Bangladesh | 19 | 47.4 | 17,530 | 16.7 |

| Kenyon, 1997 (49) | ≥10 | 0–4 | Case-control | Botswana | 107 | 12.2 | 697 | 6.2 |

| Lienhardt, 1999–2001 (50) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Case-control | The Gambia | 1,105 | 31.9 | 967 | 6.1 |

| Madico, 1990 (25) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Cross-sectional | Peru | 175 | 55.4 | 382 | 33.8 |

| Mandalakas, 2015 (34) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Case-control | South Africa | 824 | 45.9 | 501 | 30.1 |

| McPhedran, 1935 (59) | NP | 0–14 | Case-control | United States | 1,342 | 72.3 | 705 | 36.2 |

| Nakaoka, 2006 (51) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Case-control | Nigeria | 158 | 32.9 | 48 | 12.5 |

| Narain, 1960–1961 (52) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Cross-sectional | India | 790 | 24.2 | 9,186 | 12.0 |

| Narasimhan, 2012 (60) | >10 | 0–14 | Case-control | India | 53 | 34.0 | 53 | 22.6 |

| Olender, 1997–2000 (58) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Cross-sectional | Peru | 61 | 23.0 | 563 | 5.2 |

| Radhakrishna, 1968–1983 (33) | Multiplee | 0–14 | Cross-sectionalf | India | 3,191 | 37.1 | 106,717 | 15.9 |

| Roelsgaard, 1955–1960 (53) | ≥10 | 0–9 | Cross-sectional | Six countries in tropical Africag | 1,010 | 11.0 | 7,295 | 7.2 |

| Rutherford, 2012 (54) | ≥10 | 0–9 | Case-control | Indonesia | 299 | 48.2 | 72 | 9.7 |

| Schlesinger, 1929 (55) | NP | 0–10 | Case-control | United Kingdom | 68 | 67.7 | 438 | 18.3 |

| Shaw, 1948–1952 (56) | ≥5 | 0–14 | Case-control | United Kingdom | 823 | 41.8 | 709 | 22.1 |

| Whalen, 1995–2006 (15) | ≥10 | 0–14 | Case-control | Uganda | 1,199 | 65.3 | 564 | 13.3 |

Abbreviations: LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection; NP, not provided.

a Year refers to the year in which the study was implemented. If study implementation was not specified, the date of publication was used.

b Represented by millimeter induration recorded 48–72 hours after tuberculin skin test implementation. Gilpin et al. (35) is the only study that used the Heaf test, in which tuberculosis infection is measured by a grading system instead of millimeter induration.

c Represents the total number of household-contact or community-control participants in each study.

d Represents the percent yield of latent tuberculosis infections in household-contact or community-control groups.

e Multiple tuberculin skin tests used for positive classification based on group assigned.

f This was a cross-sectional secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial.

g Countries included Gambia, Kenya, Uganda, Zanzibar, Tanganyika, and Sierra Leone.

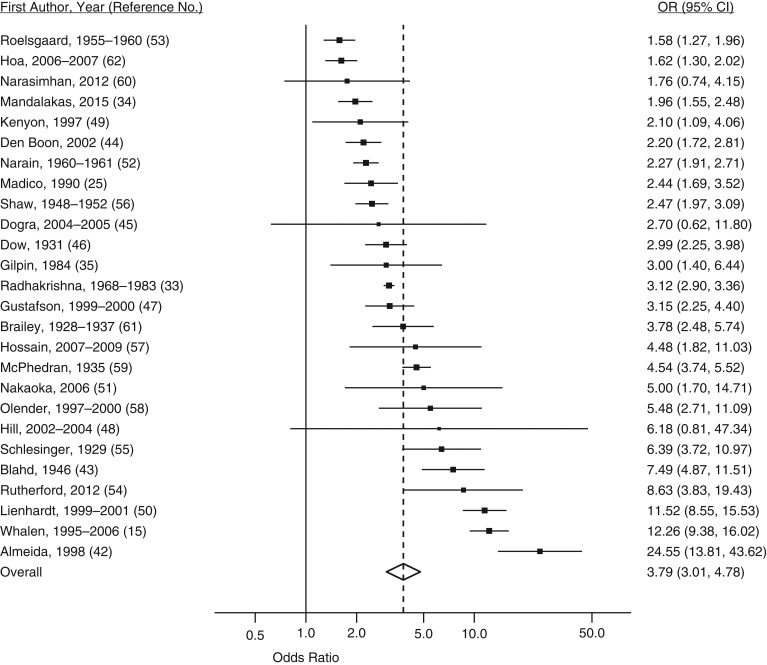

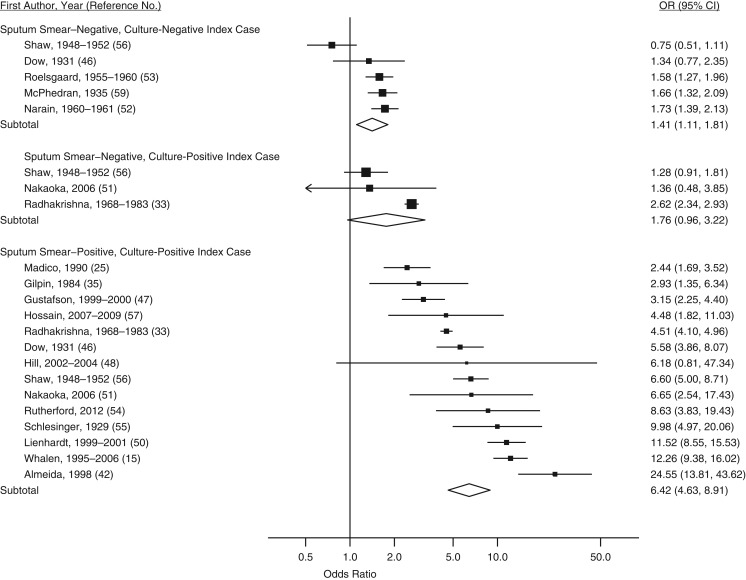

The overall odds ratio for infection between household contact and community control groups was 3.79 (95% confidence interval (CI): 3.01, 4.78; Table 2 and Figure 2). After stratification, the odds ratio for tuberculosis infection with household contact compared with community control groups was highest when the index case was positive on both smear and culture (odds ratio (OR) = 6.42, 95% CI: 4.63, 8.91; Table 2 and Figure 3), children were 0–4 years old (OR = 5.39, 95% CI: 3.86, 7.53), the study was implemented in the Americas (OR = 5.73, 95% CI: 3.44, 9.53), and the setting had a tuberculosis disease prevalence ≤250 cases per 100,000 (OR = 5.95, 95% CI: 1.01, 34.94) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup Analysis of Studies With Both Household Tuberculosis Contact and Community-Control Groups of Children, From a Meta-Analysis of 26 Studies Published During 1929–2015

| No. of Studiesa | Pooled OR | 95% CI | I2 | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 26 | 3.79 | 3.01, 4.78 | 93.6 | (15, 25, 33–35, 42–62) |

| Age group, years | |||||

| 0–4 | 14 | 5.39 | 3.86, 7.53 | 82.5 | (15, 33, 42–44, 46, 47, 49, 50, 52, 53, 56, 59) |

| 5–9 | 9 | 3.48 | 2.46, 4.94 | 89.6 | (33, 42, 44, 46, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59) |

| 10–14 | 8 | 2.77 | 2.12, 3.63 | 78.6 | (33, 42, 44, 46, 52, 53, 56, 58) |

| Region | |||||

| Asia | 7 | 2.70 | 1.95, 3.72 | 87.2 | (33, 45, 52, 54, 57, 60, 62) |

| Africa | 10 | 3.66 | 2.06, 6.49 | 96.2 | (15, 34, 35, 44, 47–51, 53) |

| Europe | 3 | 3.37 | 2.20, 5.15 | 80.5 | (46, 55, 56) |

| Americas | 6 | 5.73 | 3.44, 9.53 | 90.0 | (25, 42, 43, 58, 59, 61) |

| BCG vaccination status of household contact | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 3.78 | 1.60, 8.97 | 92.4 | (15, 42, 47, 58) |

| No | 4 | 2.45 | 1.32, 4.56 | 48.9 | (15, 42, 47, 58) |

| Proximity of household contact to index case | |||||

| Different room | 3 | 2.70 | 1.38, 5.30 | 88.1 | (15, 47, 48) |

| Same room, different bed | 3 | 3.86 | 2.57, 5.81 | 61.8 | (15, 47, 48) |

| Shared bed | 2 | 4.31 | 3.19, 5.83 | 0 | (15, 47) |

| HIV status of index case | |||||

| Positive | 3 | 2.69 | 1.49, 4.87 | 83.0 | (15, 47, 49) |

| Negative | 3 | 3.27 | 1.77, 6.04 | 83.3 | (15, 47, 49) |

| Sputum-smear and culture status of index case | |||||

| Smear-positive, culture-positive vs. control | 14 | 6.42 | 4.63, 8.91 | 90.6 | (15, 25, 33, 35, 42, 46–48, 50, 51, 54–57) |

| Smear-negative, culture-positive vs. control | 3 | 1.76 | 0.96, 3.22 | 87.7 | (33, 51, 56) |

| Smear-negative, culture-negative vs. control | 5 | 1.41 | 1.11, 1.81 | 72.9 | (46, 52, 53, 56, 59) |

| Smear-positive vs. culture-positiveb | 3 | 3.74 | 1.32, 10.58 | 96.9 | (33, 50, 55) |

| Sputum-smear grade of index casec | |||||

| Smear grade +1 | 4 | 4.39 | 2.09, 9.23 | 80.3 | (18, 24, 40, 44) |

| Smear grade +2 | 4 | 5.84 | 2.56, 13.30 | 81.2 | (3, 25, 40, 59) |

| Smear grade +3 | 4 | 8.72 | 2.21, 34.41 | 95.4 | (25, 42, 47, 54) |

| Study design | |||||

| Cross-sectional | 10 | 2.46 | 1.96, 3.07 | 87.4 | (25, 33, 44–46, 52, 53, 57, 58, 62) |

| Case-control | 16 | 4.94 | 3.37, 7.24 | 93.4 | (15, 34, 35, 42, 43, 47–51, 54–56, 59–61) |

| Yeard | |||||

| Before 2000 | 13 | 3.56 | 2.79, 4.54 | 91.7 | (25, 33, 35, 42, 43, 46, 49, 52, 53, 55, 56, 59, 61) |

| 2000 and later | 13 | 4.06 | 2.44, 6.74 | 95.0 | (15, 34, 44, 45, 47, 48, 50, 51, 54, 57, 58, 60, 62) |

| Before 1980 | 9 | 3.28 | 2.58, 4.16 | 91.2 | (33, 43, 46, 52, 53, 55, 56, 59, 61) |

| 1980 and later | 17 | 4.15 | 2.66, 6.45 | 94.5 | (15, 25, 34, 35, 42, 44, 45, 47–51, 54, 57, 58, 60, 62) |

| Before 1960 | 7 | 3.60 | 2.43, 5.35 | 92.5 | (43, 46, 53, 55, 56, 59, 61) |

| 1960 and later | 19 | 3.89 | 2.88, 5.26 | 94.2 | (15, 25, 33–35, 42, 44, 45, 47–52, 54, 57, 58, 60, 62) |

| Tuberculosis disease prevalencee | |||||

| >500 per 100,000 | 4 | 2.13 | 1.84, 2.48 | 0 | (25, 34, 44, 49) |

| >250 and ≤500 per 100,000 | 9 | 5.49 | 3.22, 9.35 | 87.0 | (15, 45, 47, 48, 50, 51, 54, 57, 60) |

| ≤250 per 100,000 | 3 | 5.95 | 1.01, 34.94 | 97.5 | (42, 58, 62) |

| National income statusf | |||||

| Low income | 6 | 5.12 | 2.07, 12.67 | 97.3 | (15, 45, 47, 48, 50, 53, 57) |

| Middle income | 14 | 3.09 | 2.39, 4.00 | 89.1 | (25, 33–35, 42, 44, 45, 49, 51, 52, 54, 58, 60, 62) |

| High income | 6 | 4.12 | 2.98, 5.71 | 84.9 | (43, 46, 55, 56, 59, 61) |

Abbreviations: BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio.

a The number of studies in each subgroup may exceed the total number of studies because a study may include multiple values of each subgroup. For example, a single study may have children in all age groups of 0–4, 5–9, and 10–14 years.

b Comparison of infection rates from contacts of smear-positive, culture-positive index cases versus smear-negative, culture-positive index cases.

c Includes only studies with smear-positive, culture-positive index cases.

d Year refers to the year in which the study was implemented. If study implementation was not specified, the date of publication was used.

e Disease prevalence is per 100,000 persons. Only studies conducted in 1990 or afterward were included unless prevalence levels were given in the paper.

f Income status was calculated based on the World Bank Income Classification (2015).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of latent tuberculosis infection for children who were exposed to tuberculosis in the household and children who were not, from a meta-analysis of 26 studies published during 1929–2015. Squares with bars represent study-specific odds ratios (ORs) with confidence intervals (CIs), and the diamond represents the summary odds ratio estimate. A random-effects model with DerSimonian and Laird weights, equalizing the weight of the studies to the pooled estimate, was used to derive the summary estimate. Assessment of heterogeneity: I2 = 93.6%; P = 0.000.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of latent tuberculosis infection in household-contact and community-control groups by the smear and culture status of the index case from a meta-analysis of 26 studies published during 1929–2015. Squares with bars represent study-specific odds ratios (ORs) with confidence intervals (CIs), and each diamond represents the summary OR estimate for the stratum above it. A random-effects model with DerSimonian and Laird weights, equalizing the weight of the studies to the pooled estimate, was used to derive each stratified summary estimate. Assessments of heterogeneity: sputum smear–negative, culture-negative index cases, I2 = 72.9% (P = 0.005); sputum smear–negative, culture-positive index cases, I2 = 87.7% (P = 0.000); sputum smear–positive, culture-positive index cases, I2 = 90.6% (P = 0.000).

In univariable metaregression analysis, the ratio of odds ratios was statistically higher in children <5 years of age compared with children 10–14 years of age (ratio of ORs = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.00, 3.78), smear- and culture-positive index cases versus smear- and culture-negative (ratio of ORs = 4.46, 95% CI: 2.49, 8.00), and in case-control studies versus cross-sectional studies (ratio of ORs = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.17, 3.26) (Table 3). Compared with settings with tuberculosis disease prevalence >500 cases per 100,000, ratios of odds ratios of infection were higher in settings with more than 250 and up to 500 cases per 100,000 (ratio of ORs = 2.58, 95% CI: 0.93, 7.18) and ≤250 cases per 100,000 (ratio of ORs = 2.40, 95% CI: 0.67, 8.57), but these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Univariable and Multivariable Metaregression in Studies With Household Tuberculosis Contact and Community Control Groups of Children, From a Meta-Analysis of 26 Studies Published During 1929–2015

| Study Characteristic | No. of Studiesa | Univariable Model | Multivariable Modelb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio of Odds Ratiosb | 95% CI | Ratio of Odds Ratiosb | 95% CI | ||

| Age of child with household contact, years | |||||

| 10–14 | 8 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 5–9 | 9 | 1.22 | 0.61, 2.44 | 1.35 | 0.88, 2.06 |

| 0–4 | 14 | 1.95 | 1.00, 3.78 | 2.24 | 1.43, 3.51 |

| Region | |||||

| Asia | 7 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Africa | 10 | 1.30 | 0.62, 2.73 | 0.83 | 0.45, 1.52 |

| Europe | 3 | 1.22 | 0.45, 3.30 | 0.88 | 0.42, 1.82 |

| Americas | 6 | 2.01 | 0.87, 4.60 | 1.85 | 0.73, 4.68 |

| BCG vaccination status of household contact | |||||

| No | 4 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Yes | 4 | 1.41 | 0.31, 6.47 | ||

| Proximity of household contact to index case | |||||

| Different room | 3 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Same room, different bed | 3 | 1.39 | 0.54, 3.55 | ||

| Shared bed | 2 | 1.49 | 0.51, 4.38 | ||

| HIV status of index case | |||||

| Negative | 3 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Positive | 3 | 0.84 | 0.26, 2.69 | ||

| Sputum-smear and culture status of the index case | |||||

| Smear-negative, culture-negative | 5 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Smear-negative, culture-positive | 3 | 1.35 | 0.61, 2.99 | 1.42 | 0.86, 2.36 |

| Smear-positive, culture-positive | 14 | 4.46 | 2.49, 8.00 | 5.45 | 3.43, 8.64 |

| Sputum-smear grade of the index casec | |||||

| Smear grade +1 | 4 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Smear grade +2 | 4 | 1.31 | 0.22, 7.77 | ||

| Smear grade +3 | 4 | 1.87 | 0.32, 10.85 | ||

| Study design | |||||

| Cross-sectional | 10 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Case-control | 16 | 1.95 | 1.17, 3.26 | 1.11 | 0.56, 2.32 |

| Yeard | |||||

| Before 2000 | 13 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| 2000 and later | 13 | 1.13 | 0.62, 2.04 | ||

| Before 1980 | 9 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| 1980 and later | 17 | 1.24 | 0.68, 2.24 | ||

| Before 1960 | 7 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| 1960 and later | 19 | 1.08 | 0.56, 2.05 | ||

| Tuberculosis disease prevalencee | |||||

| >500 per 100,000 | 4 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| >250 and ≤500 per 100,000 | 9 | 2.58 | 0.93, 7.18 | ||

| ≤250 per 100,000 | 3 | 2.40 | 0.67, 8.57 | ||

| National income statusf | |||||

| Low income | 6 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Middle income | 14 | 0.61 | 0.30, 1.27 | ||

| High income | 6 | 0.82 | 0.35, 1.88 | ||

Abbreviations: BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a The number of studies in each subgroup may be greater than the total number of studies because a study may include multiple values of each subgroup. For example, a single study may have children in all age groups of 0–4, 5–9, and 10–14 years.

b Differences in latent tuberculosis between subgroups of studies were quantified using random-effects meta-regression to estimate ratios of odds ratios. The multivariable metaregression model adjusted for the age of the household contact, smear and culture status of the index case, region in which the study was implemented, and the study design. Variables were chosen for inclusion in the multivariable model by use of the adjusted R2 statistic, which represents the proportion of between-study variance explained by the model. The model that explained the most between-study variance was chosen.

c Includes only studies with smear-positive, culture-positive index cases.

d Year refers to the year in which the study was implemented. If study implementation was not specified, the date of publication was used.

e Disease prevalence is per 100,000 persons. Only studies conducted in 1990 or afterward were included unless prevalence levels were given in the paper.

f Income status was calculated based on the World Bank Income Classification (2015).

Despite stratification, between-study heterogeneity of results remained high (Table 2). To investigate heterogeneity further, we performed a multivariable, random-effects metaregression analysis. After adjustment for covariates, we found that the ratio of odds ratios between household-contact and community-control groups was higher among children 0–4 years old compared with children 10–14 years old (ratio of ORs = 2.24, 95% CI: 1.43, 3.51) and among smear-positive compared with smear-negative index cases (ratio of ORs = 5.45, 95% CI: 3.43, 8.64). Other study factors, such as region or study design, did not explain variance across studies (Table 3).

We calculated the population attributable fraction of household exposure using the results of studies that included randomly sampled surveys (Table 4) as the measure of community prevalence of infection (25, 33, 44–46, 52, 53, 57, 58, 62). The average of the probability of exposure among cases (Pcases) was 22.9, and the random-effects pooled prevalence ratio from these studies was 1.97 (95% CI: 1.69, 2.29; I2 = 85.0%). From this, we found the population attributable fraction of household exposure to a person with tuberculosis to be 11.3% (95% CI: 9.37, 12.92). After exclusion of 2 outlier studies (57, 62), where the probability of exposure among cases was low (Table 4), the mean probability of exposure among cases was 28.5, and the pooled prevalence ratio was 1.98 (95% CI: 1.69, 2.33). From this data, we found the population attributable fraction to be 14.1% (95% CI: 11.6, 16.3).

Table 4.

Estimates of the Population Attributable Fraction of Household and Community Tuberculosis Transmission From 10 Studies That Included Randomly Sampled Surveys From the General Populationa, 1931–2009

| First Author, Yearb (Reference No.) | Household Contacts | Community Controls | Pcasesc | Prevalence Ratio | 95% CI | PAF | 95% CId | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Infected | Total No. | No. Infected | Total No. | ||||||

| Dow, 1931 (46) | 102 | 170 | 140 | 507 | 42.15 | 2.17 | 1.80, 2.62 | 22.73 | 16.41, 32.62 |

| Roelsgaard, 1955–1960 (53) | 111 | 1,010 | 528 | 7,295 | 17.37 | 1.52 | 1.25, 1.84 | 5.94 | 1.62, 10.36 |

| Narain, 1960–1961 (52) | 191 | 790 | 1,102 | 9,186 | 14.78 | 2.02 | 1.76, 2.31 | 7.46 | 4.18, 10.92 |

| Madico, 1990 (25) | 97 | 175 | 129 | 382 | 42.92 | 1.64 | 1.35, 1.99 | 16.75 | 9.58, 25.86 |

| Olender, 1997–2000 (58) | 14 | 61 | 29 | 563 | 32.56 | 4.46 | 2.49, 7.96 | 25.26 | 0, 60.54 |

| Dogra, 2004–2005 (45) | 3 | 16 | 7 | 89 | 30.0 | 2.38 | 0.69, 8.27 | 17.39 | 0, 60.87 |

| Den Boon, 2002 (44) | 179 | 401 | 253 | 943 | 41.44 | 1.66 | 1.43, 1.94 | 16.48 | 11.05, 23.58 |

| Radhakrishna, 1969–1983 (33) | 1,173 | 3,191 | 16,960 | 106,717 | 6.47 | 2.34 | 2.23, 2.45 | 3.71 | 2.97, 4.39 |

| Hoa, 2006–2007 (62) | 51 | 189 | 3,699 | 21,055 | 1.36 | 1.54 | 1.21, 1.95 | 0.48 | 0, 0.98 |

| Hossain, 2007–2009 (57) | 9 | 19 | 2,934 | 17,530 | 0.31 | 2.83 | 1.76, 4.55 | 0.20 | 0, 0.64 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PAF, population attributable fraction.

a Only data from randomly sampled surveys were used. Case-control designs may incorrectly estimate the proportion of exposed (household contact) and/or unexposed (community control) populations in the community at large.

b Year refers to the year in which the study was implemented. If study implementation was not specified, the date of publication was used. Data from Madico were taken from a previous tuberculin survey.

cPcases is the prevalence of household tuberculosis exposure among cases.

d These are Wald confidence intervals that reflect the uncertainty around the prevalence ratio and the probability of exposure among cases.

Five studies (25, 33, 44, 45, 47) provided adjusted odds ratios when comparing children exposed to a person with tuberculosis in their household with children who were not (Web Table 6). Sensitivity analysis displayed little difference after adjustment for potential confounders. The Harbord test for publication bias was not significant (P = 0.841). Inspecting funnel plots for asymmetry also did not reveal remarkable asymmetry, suggesting minimal if any publication bias (Web Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

To estimate the influence of household contact on tuberculosis transmission, we collected and analyzed data from 26 studies of children who were exposed to tuberculosis in the household and children who were not. Using a random-effects analysis, we found that a child exposed to a person with tuberculosis in the household was almost 4 times more likely to have tuberculosis infection than an age-matched child in the same community but without active tuberculosis in the household. At the population level however, contact with a household member with tuberculosis accounted for a relatively small proportion of total transmission in studies with randomly sampled study populations.

Recently, 4 important meta-analyses evaluating tuberculosis contact investigations have been published, all demonstrating that individuals in household contact with a person with tuberculosis have a high yield of tuberculosis infection and disease (26–29). The current analysis expands the scope of these studies by including control households and community tuberculin skin test surveys. With the added control group, we focused our analysis on the age-specific differences in the prevalence of tuberculosis infection in the households and the community. This difference was expressed as an odds ratio which can be interpreted as the odds of infection associated with household exposure compared with the odds of infection among community members in the same age category. The odds ratio was greater, sometimes much greater, than 1 for all included age groups, indicating that the household is a “hot spot” of intense transmission of M. tuberculosis.

We found that age of the child with household contact and sputum-smear status of the index case were influential predictors of increased yield of infection in case-contact groups compared with community-control groups. These results support current recommendations to perform contact investigations and provide preventive isoniazid therapy in households with smear-positive index cases and children younger than 5 years of age (63). Despite significant differences between different age groups of children, our results also support an expanded implementation of current guidelines in older children. Contact investigations may identify young children, less than 5 years of age, with progressive primary disease (15, 64–66) and lead to appropriate antituberculosis therapy. However, children aged 5–14 years were also at increased likelihood of tuberculosis infection compared with community control groups in our analysis. Although these children may have a lower risk for progressive disease than younger children, they would likely benefit from treatment for latent tuberculosis, if present, and thereby reduce the risk of developing disease from recent exposure (67). Protecting children at risk for tuberculosis transmission in households of index cases should be recommended and advocated for by policy makers, especially in developing countries (68).

Households clearly represent areas of intense transmission of M. tuberculosis, but the effect of this transmission on the overall burden of disease in a community remains unknown. Results from published studies vary. Investigators in Uganda suggest transmission might be primarily within households (15), whereas studies from South Africa estimate that community transmission accounts for >80% of transmission (12, 17). We found that the population attributable fraction of household exposure was <20%, meaning that less than 20% of transmission in a population occurs in households. The population attributable fraction takes into account both the magnitude of effect and the prevalence of the exposure—in this case, the presence of an individual with tuberculosis in the home. Our population attributable fraction estimate is low because the prevalence of household exposure at the population level is low. Because tuberculosis disease affects less than 1% of households in a community at any time, exposure opportunities between a person with tuberculosis and their social network outside the household are more numerous, influencing the proportion of M. tuberculosis transmission that occurs in the community.

The individual- and population-level epidemiologic parameters estimated in our study have important implications for public health; however, they should be interpreted cautiously. We found substantial heterogeneity when using all 26 studies and when we used a subset of 10 community-based studies. Some, but not all, of this heterogeneity was explained by stratification, random-effects models, or metaregression analysis. Enduring variability suggests that factors not investigated in this analysis—such as undocumented past household exposure among community controls, differences in the recruitment of control groups between studies, or the reliability of readers of tuberculin skin tests—could be influencing the observed differences. Other meta-analyses addressing contact investigations have found similarly high heterogeneity, even after stratification (26–29). This may indicate that the significance of household transmission is largely reliant on local dynamics of tuberculosis transmission.

Our study has other limitations. First, we pooled data only from observational studies, which may be subject to confounding. Our effect sizes were large, however, and confounding is generally more of a concern when effect sizes are small (69). Second, our assumption that household transmission occurred when an infected child had household tuberculosis exposure is most reliable for children of younger ages, because exposures outside the home increase with age. Third, children with household contact with a person with tuberculosis are more likely to receive isoniazid preventative treatment than community-control children, and therefore misclassification of uninfected case-contact children is possible. Finally, we used a subset of 10 papers when estimating the population attributable fraction; most of these papers came from high-burden countries, so the results may be less applicable in low-burden countries. Moreover, we were not able to stratify results because of the low number of studies and 2 clear outlier studies.

Publication bias is possible in even the most thorough systematic review. A strength of our review is that our systematic search used multiple electronic reference databases with no restrictions by year of publication. A substantial number of important studies on tuberculosis were conducted in the first half of the 20th century (66), and we found and included several high-quality studies from before 1950. Furthermore, our team searched other literature, such as conference abstracts and dissertations. Our exhaustive search, in combination with symmetrical funnel plots and a statistically nonsignificant Harbord test, suggest publication bias did not have a strong impact on our results.

Our analysis indicates that households of tuberculosis index cases are areas of intense transmission. This high risk of infection acquired in the household was evident in countries of all income levels and over all time periods. Our analysis also suggests that at the population level, a sizeable portion of tuberculosis transmission occurs in the community. Contact investigations are clearly highly effective at finding vulnerable children at risk, even up to age 14 years, and must be further encouraged as part of tuberculosis control. However, to reduce the global incidence of tuberculosis to 1 case per million by 2050, to reach the goal set by the World Health Organization (70), additional methods of community-based prevention must be further studied and prioritized to supplement passive disease case-finding and household-contact investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia (Leonardo Martinez, Ye Shen, Allan Kizza, Christopher C. Whalen); Institute of Global Health, College of Public Health, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia (Leonardo Martinez, Christopher C. Whalen); Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda (Ezekiel Mupere); Uganda–Case Western Reserve University Research Collaboration, Tuberculosis Research Unit, Kampala, Uganda (Ezekiel Mupere); and Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Centre for International Health and the Otago International Health Research Network, University of Otago Medical School, Dunedin, New Zealand (Philip C. Hill).

L.M., A.K., C.C.W. were supported in part by an investigator-initiated grant (grant AI 093856), and L.M. was supported by a diversity supplement grant (grant 3R01AI093856-05W1) from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank the University of Georgia Interlibrary Loan office for their tireless efforts at retrieving hard-to-reach manuscripts, dissertations, and books. We thank Dr. Robert H. Gilman, Lilia Cabrera, and the rest of the Asociación Benefica PRISMA research team in Peru for providing reformatted data from a published study to allow for its inclusion in the current analysis. Also we thank the research groups, Epidemiology in Action and the Jiangsu Province Tuberculosis Control Division at China's Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for their useful and instructive comments on presentations of this project. In addition, we thank Fernando Martinez, Dr. Limei Zhu, Maria Eugenia Castellanos, and Dr. Juliet Sekandi for their thoughts and editorial comments on the manuscript.

The funders had no involvement in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, in writing the report, or in the decision to submit.

Results from this project were presented as a poster at the 46th Union Conference on Lung Health, December 2–6, 2015, in Cape Town, South Africa (abstract PC-1172-06).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Janssens JP, Rieder HL. An ecological analysis of incidence of tuberculosis and per capita gross domestic product. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(5):1415–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oxlade O, Murray M. Tuberculosis and poverty: why are the poor at greater risk in India. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e47533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dye C, Garnett GP, Sleeman K, et al. Prospects for worldwide tuberculosis control under the WHO DOTS strategy. Directly observed short-course therapy. Lancet. 1998;352(9144):1886–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raviglione M, Marais B, Floyd K, et al. Scaling up interventions to achieve global tuberculosis control: progress and new developments. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1902–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borgdorff MW, Yew WW, Marks G. Active tuberculosis case finding: why, when and how? [editorial]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(3):285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dowdy DW, Azman AS, Kendall EA, et al. Transforming the fight against tuberculosis: targeting catalysts of transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(8):1123–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lönnroth K, Castro KG, Chakaya JM, et al. Tuberculosis control and elimination 2010–50: cure, care, and social development. Lancet. 2010;375(9728):1814–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whalen CC. Failure of directly observed treatment for tuberculosis in Africa: a call for new approaches. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(7):1048–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wood R, Lawn SD, Johnstone-Robertson S, et al. Tuberculosis control has failed in South Africa—time to reappraise strategy. S Afr Med J. 2011;101(2):111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lienhardt C, Bennett S, Del Prete G, et al. Investigation of environmental and host-related risk factors for tuberculosis in Africa. I. Methodological aspects of a combined design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(11):1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shapiro AE, Variava E, Rakgokong MH, et al. Community-based targeted case finding for tuberculosis and HIV in household contacts of patients with tuberculosis in South Africa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(10):1110–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Verver S, Warren RM, Munch Z, et al. Proportion of tuberculosis transmission that takes place in households in a high-incidence area. Lancet. 2004;363(9404):212–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilkinson D, Pillay M, Crump J, et al. Molecular epidemiology and transmission dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in rural Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2(8):747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beyers N. Case finding in children in contact with adults in the house with TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7(11):1013–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whalen CC, Zalwango S, Chiunda A, et al. Secondary attack rate of tuberculosis in urban households in Kampala, Uganda. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glynn JR, Guerra-Assunção JA, Houben RM, et al. Whole genome sequencing shows a low proportion of tuberculosis disease is attributable to known close contacts in rural Malawi. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Middelkoop K, Mathema B, Myer L, et al. Transmission of tuberculosis in a South African community with a high prevalence of HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(1):53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crampin AC, Glynn JR, Traore H, et al. Tuberculosis transmission attributable to close contacts and HIV status, Malawi. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(5):729–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rieder HL. Contacts of tuberculosis patients in high-incidence countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7(12 suppl 3):S333–S336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rieder HL, Chadha VK, Nagelkerke NJ, et al. Guidelines for conducting tuberculin skin test surveys in high-prevalence countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(suppl 1):S1–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Borgdorff MW, Sebek M, Geskus RB, et al. The incubation period distribution of tuberculosis estimated with a molecular epidemiological approach. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(4):964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vynnycky E, Fine PE. Lifetime risks, incubation period, and serial interval of tuberculosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(3):247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bloch AB, Snider DE Jr. How much tuberculosis in children must we accept. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(1):14–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Drucker E, Alcabes P, Bosworth W, et al. Childhood tuberculosis in the Bronx, New York. Lancet. 1994;343(8911):1482–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Madico G, Gilman RH, Checkley W, et al. Community infection ratio as an indicator for tuberculosis control. Lancet. 1995;345(8947):416–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morrison J, Pai M, Hopewell PC. Tuberculosis and latent tuberculosis infection in close contacts of people with pulmonary tuberculosis in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(6):359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fox GJ, Barry SE, Britton WJ, et al. Contact investigation for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(1):140–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shah NS, Yuen CM, Heo M, et al. Yield of contact investigations in households of patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):381–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blok L, Sahu S, Creswell J, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of tuberculosis contact investigation interventions in eleven high burden countries. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sepkowitz KA. How contagious is tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(5):954–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Menzies D. Issues in the management of contacts of patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Can J Public Health. 1997;88(3):197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Theron G, Jenkins HE, Cobelens F, et al. Data for action: collection and use of local data to end tuberculosis. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2324–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Radhakrishna S, Frieden TR, Subramani R, et al. Additional risk of developing TB for household members with a TB case at home at intake: a 15-year study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11(3):282–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mandalakas AM, Kirchner HL, Walzl G, et al. Optimizing the detection of recent tuberculosis infection in children in a high tuberculosis-HIV burden setting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(7):820–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gilpin TP, Hammond M. Active case-finding—for the whole community or for tuberculosis contacts only. S Afr Med J. 1987;72(4):260–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C. Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(1):15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. Epidemiologic Research. Belmont, CA: Lifetime Learning Publications; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Greenland S. Interval estimation by simulation as an alternative to and extension of confidence intervals. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(6):1389–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006;25(20):3443–3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Almeida LM, Barbieri MA, Da Paixao AC, et al. Use of purified protein derivative to assess the risk of infection in children in close contact with adults with tuberculosis in a population with high Calmette-Guérin bacillus coverage. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20(11):1061–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blahd M, Leslie EI, Rosenthal SR. Infectiousness of the “closed case” in tuberculosis. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1946;36(7):723–726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. den Boon S, Verver S, Marais BJ, et al. Association between passive smoking and infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dogra S, Narang P, Mendiratta DK, et al. Comparison of a whole blood interferon-gamma assay with tuberculin skin testing for the detection of tuberculosis infection in hospitalized children in rural India. J Infect. 2007;54(3):267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dow DJ, Lloyd WE. The incidence of tuberculous infection and its relation to contagion in children under 15. Br Med J. 1931;2(3682):183–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gustafson P, Lisse I, Gomes V, et al. Risk factors for positive tuberculin skin test in Guinea-Bissau. Epidemiology. 2007;18(3):340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hill PC, Brookes RH, Fox A, et al. Surprisingly high specificity of the PPD skin test for M. tuberculosis infection from recent exposure in The Gambia. PLoS One. 2006;1:e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kenyon TA, Creek T, Laserson K, et al. Risk factors for transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from HIV-infected tuberculosis patients, Botswana. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(10):843–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lienhardt C, Fielding K, Sillah J, et al. Risk factors for tuberculosis infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a contact study in The Gambia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(4):448–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nakaoka H, Lawson L, Squire SB, et al. Risk for tuberculosis among children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(9):1383–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Narain R, Nair SS, Rao GR, et al. Distribution of tuberculous infection and disease among households in a rural community. Bull World Health Organ. 1966;34(4):639–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Roelsgaard E, Iversen E, Blocher C. Tuberculosis in tropical Africa. An epidemiological study. Bull World Health Organ. 1964;30:459–518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rutherford ME, Nataprawira M, Yulita I, et al. QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube assay vs. tuberculin skin test in Indonesian children living with a tuberculosis case. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(4):496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schlesinger B, Hart PD. Human contagion and tuberculous infection in childhood. Arch Dis Child. 1930;5(27):191–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shaw JB, Wynn-Williams N. Infectivity of pulmonary tuberculosis in relation to sputum status. Am Rev Tuberc. 1954;69(5):724–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hossain S, Zaman K, Banu S, et al. Tuberculin survey in Bangladesh, 2007–2009: prevalence of tuberculous infection and implications for TB control. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(10):1267–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Olender S, Saito M, Apgar J, et al. Low prevalence and increased household clustering of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in high altitude villages in Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68(6):721–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McPhedran FM, Opie EL. The spread of tuberculosis in families. Am J Epidemiol. 1935;22(3):565–643. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Narasimhan P. The Epidemiology and Transmission Dynamics of Tuberculosis in southern India, With a Focus on Risk Factors and Household Contact Patterns [dissertation]. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: School of Public Health and Community Medicine at the University of New South Wales; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brailey M. A study of tuberculous infection and mortality in the children of tuberculous households. Am J Hyg. 1940;31:1–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hoa NB, Cobelens FG, Sy DN, et al. First national tuberculin survey in Viet Nam: characteristics and association with tuberculosis prevalence. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(6):738–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stop TB Partnership Childhood TB Subgroup World Health Organization Guidance for National Tuberculosis Programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. Chapter 1: introduction and diagnosis of tuberculosis in children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(10):1091–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Comstock GW, Livesay VT, Woolpert SF. The prognosis of a positive tuberculin reaction in childhood and adolescence. Am J Epidemiol. 1974;99(2):131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Frost WH. Risk of persons in familial contact with pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1933;23(5):426–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, et al. The natural history of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(4):392–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zelner JL, Murray MB, Becerra MC, et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin and isoniazid preventive therapy protect contacts of patients with tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(7):853–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hill PC, Rutherford ME, Audas R, et al. Closing the policy-practice gap in the management of child contacts of tuberculosis cases in developing countries. PLoS Med. 2011;8(10):e1001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shapiro S. Is meta-analysis a valid approach to the evaluation of small effects in observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(3):223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dye C, Maher D, Weil D, et al. Targets for global tuberculosis control. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(4):460–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.