Abstract

Areas of the fusiform gyrus (FG) within human ventral temporal cortex (VTC) process high-level visual information associated with faces, limbs, words, and places. Since classical cytoarchitectonic maps do not adequately reflect the functional and structural heterogeneity of the VTC, we studied the cytoarchitectonic segregation in a region, which is rostral to the recently identified cytoarchitectonic areas FG1 and FG2. Using an observer-independent and statistically testable parcellation method, we identify 2 new areas, FG3 and FG4, in 10 human postmortem brains on the mid-FG. The mid-fusiform sulcus reliably identifies the cytoarchitectonic transition between FG3 and FG4. We registered these cytoarchitectonic areas to the common reference space of the single-subject Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template and generated probability maps, which reflect the intersubject variability of both areas. Future studies can relate in vivo neuroimaging data with these microscopically defined cortical areas to functional parcellations. We discuss these results in the context of both large-scale functional maps and fine-scale functional clusters that have been identified within the human VTC. We propose that our observer-independent cytoarchitectonic parcellation of the FG better explains the functional heterogeneity of the FG compared with the homogeneity of classic cytoarchitectonic maps.

Keywords: cytoarchitecture, fusiform gyrus, mid-fusiform sulcus (MFS), probabilistic mapping, ventral temporal cortex (VTC)

Introduction

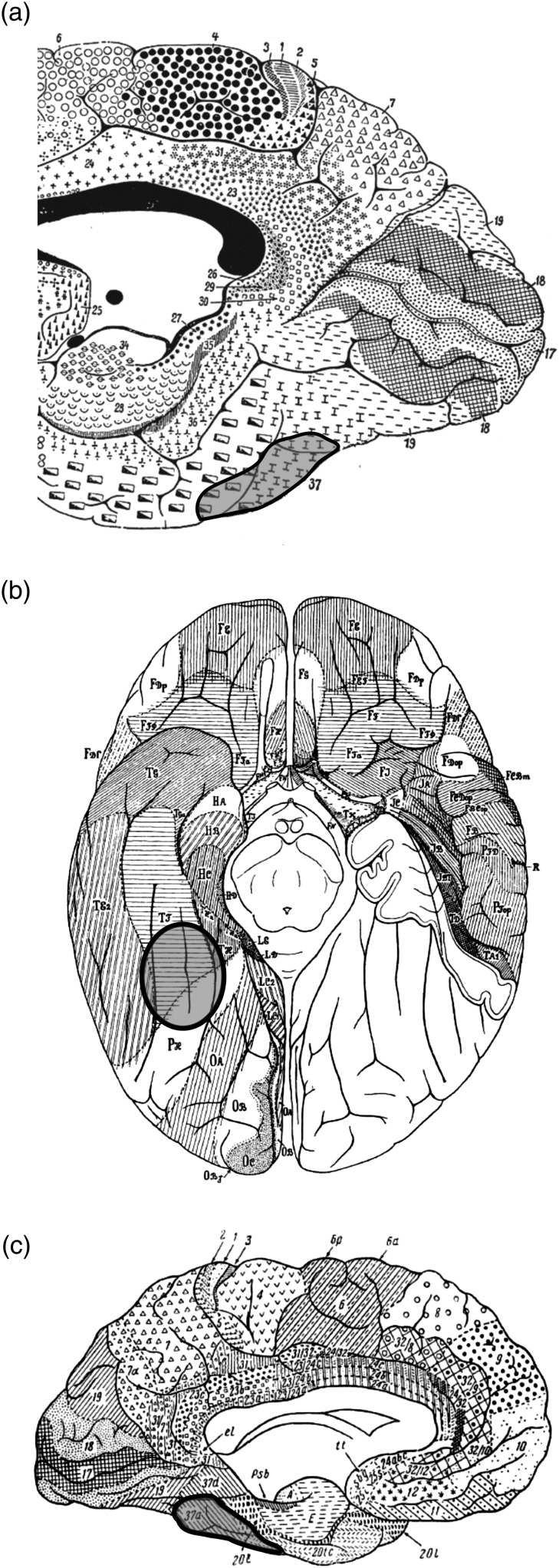

The fusiform gyrus (FG) is located in human ventral temporal cortex (VTC) within the ventral pathway or “what” processing stream (Ungerleider and Haxby 1994; Milner and Goodale 2008; Kravitz et al. 2013). Human VTC plays a pivotal role in higher order processing of visual information (Grill-Spector and Weiner 2014). Recent neuroimaging studies report that human VTC contains many functionally defined areas (Kanwisher, McDermott, et al. 1997; Epstein et al. 1999; Ishai et al. 1999; Cohen et al. 2000; Haxby et al. 2001; Peelen and Downing 2005; Schwarzlose et al. 2005; Taylor and Downing 2011; Wandell et al. 2012; Grill-Spector and Weiner 2014). However, it is relatively unknown how the microstructural organization of the VTC contributes to this higher order processing. This is because the relative cytoarchitectonic uniformity of VTC reported by historical studies (Brodmann 1909; von Economo and Koskinas 1925; Sarkisov et al. 1949; Bailey and von Bonin 1951) does not match the functional complexity of VTC reported in modern neuroimaging studies (Grill-Spector and Weiner 2014; Weiner et al. 2014). For example, Brodmann's frequently cited map (Brodmann 1909) suggests a relatively uniform cytoarchitecture of human VTC with only 1 or 2 [Brodmann Area (BA) 37 and 20] distinct areas (Fig. 1). These historical cytoarchitectonic parcellations are unsatisfactory in several ways. First, these studies implemented observer-dependent methods of a small sample of brains. The methodological shortcomings of these approaches are widely known for their inability to detect fine-grained differences between areas (Rottschy et al. 2007; Zilles and Amunts 2010; Caspers, Zilles, et al. 2013). Second, the traditional cytoarchitectonic maps are summarized as schematic two-dimensional drawings. These schematics are oversimplified and do not consider intersubject variability. Third, because some early studies argued against a correlation between sulci and cytoarchitectonic areas (Brodmann 1906; Kappers 1913), the correspondence between sulci and cytoarchitectonic divisions is largely unconsidered especially relative to tertiary sulci, which vary considerably from one hemisphere to the next.

Figure 1.

Classical cytoarchitectonic maps. (a) Brodmann (1909), mesial view, (b) von Economo and Koskinas (1925), basal view, and (c) Sarkisov et al. (1949), mesial view. Areas highlighted in blue indicate the ROI. Brodmann and Sarkisov (a and c) labeled the areas by arabic numerals (here: 20, 37). von Economo and Koskinas used both numerals and letters (here: TF, PH).

More recent anatomical studies identify additional subdivisions within the FG (Braak 1977, 1978; Caspers, Zilles, et al. 2013). For example, Caspers, Zilles, et al. (2013) used a modern observer-independent approach to determine cytoarchitectonic boundaries in the posterior FG (pFG). This approach identified 2 areas, FG1 and FG2, which differed in their columnar structure and neuronal density and distribution. The observer-independent approach was sensitive enough to detect and to quantify differences in the cytoarchitectonic profiles of FG1 and FG2 in a reproducible way, based on image analysis and statistical tests (Caspers, Zilles, et al. 2013). A further benefit in applying this approach is that it is “blind” to the geometrical pattern of the cortex. Thus, finding a correspondence between a sulcus and a cytoarchitectonic border cannot be induced by the algorithm and is particularly meaningful. Such is the case in the pFG, where the cytoarchitectonic transition between FG1 and FG2 is predicted by the shallow mid-fusiform sulcus (MFS) that bisects the FG into lateral and medial partitions (Weiner et al. 2014).

In the present study, we applied the well-established observer-independent method (Schleicher et al. 2009), which was previously used for the mapping of FG1 and FG2 as well as early and higher ventral visual areas (Amunts et al. 2000; Rottschy et al. 2007; Caspers, Zilles, et al. 2013), to investigate microstructural features of the mid-FG (mFG) and provide probabilistic anatomical maps. Furthermore, the relation of the discovered cytoarchitectonic areas of the mFG with surrounding sulci was analyzed with respect to intersubject variability in order to test the hypothesis that the MFS is a macroscopic landmark of the FG3–FG4 border.

Materials and Methods

Postmortem Brains

The cytoarchitectonic analysis was based on 10 postmortem brains acquired through the body donor program of the Anatomical Institute of the University of Düsseldorf (cf. Table 1) following the requirements of the Ethics Committee of the University of Düsseldorf. None of the subjects had a history of neurological or psychiatric diseases in their clinical records except for one, who suffered from transitory motor deficits. Handedness of the subjects was unknown. For the current analysis, 9 of the 10 brains from earlier anatomical studies of the visual cortex were used (Amunts et al. 2000; Rottschy et al. 2007; Caspers, Zilles, et al. 2013; Kujovic et al. 2013). One brain had to be replaced by another case because of artifacts in the respective histological sections through the region of interest.

Table 1.

Catalog of the analyzed postmortem brains

| Brain no. | Gender | Age (years) | Cause of death | Fresh weight (g) | Shrinkage factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pm 1 | F | 79 | Carcinoma of the bladder | 1.350 | 1.720 |

| Pm 2 | M | 56 | Rectal carcinoma | 1.270 | 1.979 |

| Pm 3 | M | 69 | Vascular disease | 1.360 | 1.951 |

| Pm 4 | M | 75 | Acute glomerulonephritis | 1.349 | 1.888 |

| Pm 6 | M | 54 | Cardiac infarction | 1.622 | 2.5 |

| Pm 7 | M | 37 | Cardiac arrest | 1.437 | 2.258 |

| Pm 8 | F | 72 | Renal arrest | 1.216 | 1.904 |

| Pm 9 | F | 79 | Cardiorespiratory insufficiency | 1.110 | 1.513 |

| Pm 10 | F | 85 | Mesenteric infarction | 1.046 | 1.722 |

| Pm 12 | F | 43 | Cardiorespiratory insufficiency | 1.198 | 2.194 |

F: female; M: male.

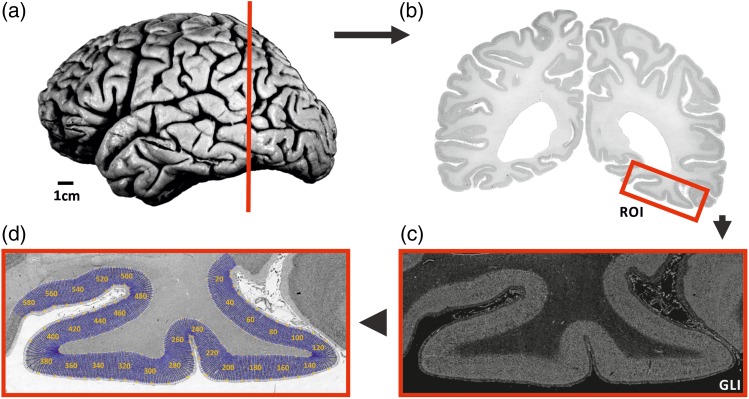

After a maximum postmortem delay of 24 h, the brains were removed from the skull and fixed in 4% formalin or Bodian's fixative for at least 6 months. To minimize deformations during fixation, all brains were suspended on the basilar/vertebral arteries. Then, MR scans of the fixated postmortem brains were acquired with a Siemens 1.5-T scanner (Erlangen, Germany) using a T1-weighted three-dimensional (3D) FLASH sequence (flip angle 40°, repetition time = 40 ms, and echo time = 5 ms for each image). Subsequently, the brains were embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned (20 µm) in the coronal plane. Every 15th section was mounted on gelatin-coated glass slides. Using a modified Gallyas silver-staining technique, the cell bodies were visualized (Merker 1983). Every fourth stained section, that is every 60th section of the series, was used for cytoarchitectonic analysis resulting in a distance of 1.2 mm between sections studied (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Histological procedure. (a) Postmortem brain pm 4 (cf. Table 1) sectioned in the coronal plane [cutting position of the histological section in (b) marked in red]. (b) Cell body-stained histological section (20 µm) indicated in (a). Red rectangle indicates the analyzed ROI. (c) The ROI was digitized and transformed into a GLI image enabling to discriminate between volume fractions of cell bodies and neuropil. (d) Curvilinear trajectories marked in blue were defined by interactively drawn inner and outer contour lines in the histological section. The equidistant GLI profiles were extracted along the trajectories for further analysis (yellow numbers indicate the position of the trajectories).

Observer-Independent Detection of Cortical Borders Based on Gray Level Index

For cytoarchitectonic analysis and detection of cortical borders, we applied an established observer-independent and statistically testable, quantitative approach (Amunts and Zilles 2001; Zilles et al. 2002; Schleicher et al. 2005, 2009) (Fig. 2). Briefly, rectangular regions of interest (ROI) covering the mFG as well as adjacent regions were digitized in the histological sections at high resolution in a meander-like sequence using a motorized scanning microscope (AxioCam MRm, Zeiss 3200K) with a mounted CCD camera (Sony, Tokyo, Japan, resolution 1.01 × 1.01 µm2/pixel). The digitized sections were then transformed into gray level index (GLI) images as a measure of the volume fraction of cell bodies (Wree et al. 1982; Schleicher and Zilles 1990). Each pixel decodes the GLI as the volume fraction of cell bodies in a corresponding square measuring field of 17 × 17 µm2. Equidistant GLI profiles were extracted along curvilinear trajectories oriented orthogonal to the cortical layers and running from an interactively traced outer contour between layers I and II to an inner contour between layer VI and the white matter. The profiles quantitatively reflect the laminar fluctuations of cell density, that is, a major hallmark of cytoarchitecture. Since the cortical thickness varied regionally and between brains, each profile was corrected to a cortical depth of 100%.

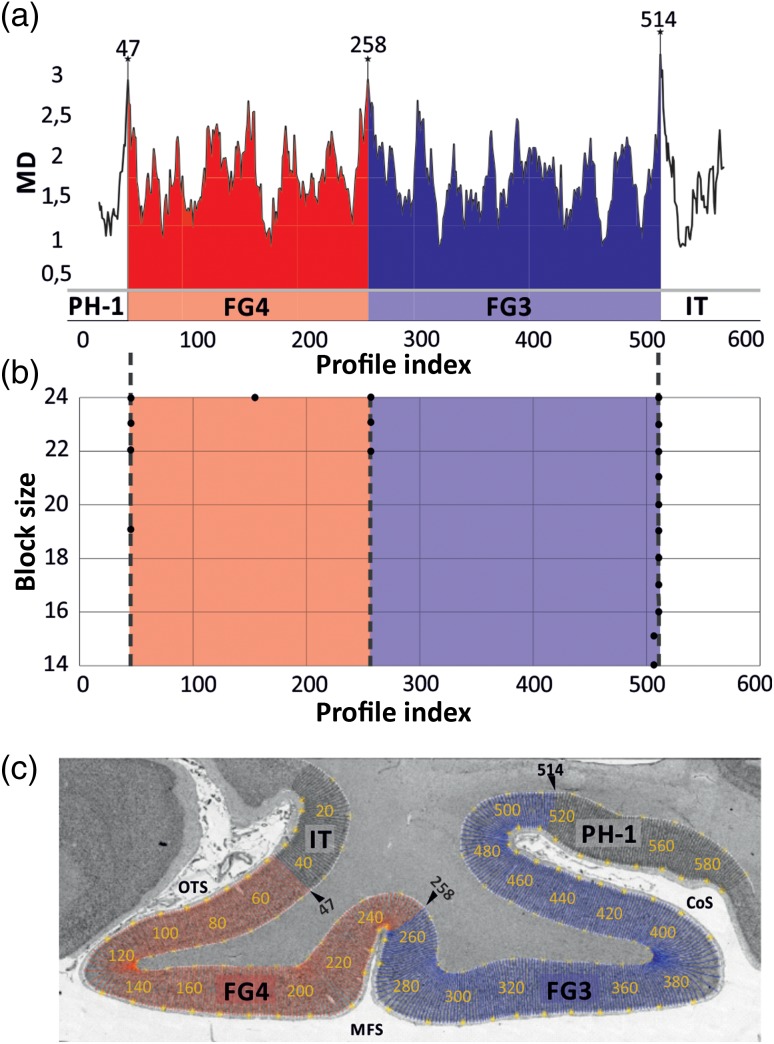

To quantitatively analyze differences between GLI profiles, the shape of each profile was expressed as a feature vector comprising the mean GLI, standard deviation, cortical depth of the center of gravity, skewness, kurtosis of the profiles, and the corresponding parameters of the profile's first derivative (Schleicher et al. 1999; Zilles et al. 2002). Differences between the feature vectors of neighboring blocks of GLI profiles at a certain profile position in the cortical ribbon were expressed as Mahalanobis distances (MDs; Mahalanobis et al. 1949; Bartels 1979) with subsequent Hotelling's T2 test with Bonferroni correction. Adjacent blocks were moved like sliding windows along the cortical ribbon. To assure reliability, the procedure was repeated for different block sizes (8–24 profiles per block; Schleicher and Zilles 1990; Schleicher et al. 2005). Areal borders are expected at positions where the distance function shows local maxima corresponding. The significance of maxima in the MD function was tested by a Hotelling's T2 test with Bonferroni correction. Cortical borders were accepted, if they were consistently present at the same position across several block sizes, and if the positions were found at comparable sites in adjacent sections (Fig. 3). To discriminate effects of occasionally inevitable histological artifacts on the automated measurements from consistent cortical transitions in the images, the detection of a border region was reconfirmed by visual inspection in the aftermath and exclusion of effect of eventual artifacts in the histological sections.

Figure 3.

Observer-independent border detection. ROI analyzed as shown in Fig. 2. (a) MD functions plotted against trajectory positions (profile index). Significant maxima were found on the position 47, 258, 514. (b) MD functions ranging from block size 8–24 profiles used for border detection are displayed. Positions of significant maxima are indicated by dots at their positions (abscissa) and the blocksize (ordinate). (c) ROI with trajectory lines along the cortical ribbon (every 10th is labeled). Borders with significant maxima in the MD function across different block sizes (cf. b) are indicated with black arrowheads. CoS: collateral sulcus; OTS: occipitotemporal sulcus; MFS: mid-fusiform sulcus; FG3: fusiform gyrus area 3 (blue); FG4: fusiform gyrus area 4 (red); adjacent not yet mapped areas: IT (inferotemporal area) and PH1 (parahippocampal area 1).

Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of Cortical Areas and Computation of Probabilistic Maps

The extent of the delineated areas FG3/4 in histological sections was interactively transferred to high-resolution scans of the respective histological sections. To provide a reliable 3D reconstruction of the histological volumes of the areas, the following datasets were used: (1) The 3D-MRI scan of the postmortem brain before histological processing and (2) the high-resolution flatbed scans of the stained histological sections (Amunts et al. 2000).

The delineated areas were mapped to the respective 3D-reconstructed histological volumes. The histological volumes were spatially normalized to the T1-weighted single-subject template of the MNI (Evans et al. 1992, 2012) using a combination of affine transformations and nonlinear elastic registration (Evans et al. 1992; Hömke 2006). To keep the anterior commissure as the anatomical reference, the data were shifted 4 mm caudally (y-axis) and 5 mm dorsally (z-axis) to the “anatomical MNI space” (Amunts et al. 2005).

Volumes of cytoarchitectonic areas were determined for each hemisphere in the 3D-reconstructed histological sections (Amunts et al. 2007). Normalized volumes of cytoarchitectonic areas were calculated as the ratio between the fresh brain volumes and brain volumes after histological processing to correct for differences in whole-brain volumes. The comparison of left and right areas, as well between genders, did not reach significant differences (non-parametric pair-wise permutation test, all P > 0.05; Bludau et al. 2014), and thus, only normalized volumes averaged across hemispheres are reported.

Probability maps of the delineated regions were calculated by superimposing the areas of all 10 brains in the MNI reference space. These maps indicate the intersubject variability of a cytoarchitectonic area at a certain position of the reference brain. The probability that a cortical area was found at a certain position in the reference brain was described by values from 0% to 100%, and color-coded.

Based on these probabilistic maps, a maximum probability map (MPM) was generated, which represents a continuous, non-overlapping parcellation of the human ventral visual cortex (Eickhoff et al. 2005, 2006). The MPM includes the areas of the present study, as well as neighboring areas on the FG (FG1/2 (Caspers, Zilles, et al. 2013) and also hOc3v, hOc4v (Rottschy et al. 2007). Here, each voxel was assigned to the cytoarchitectonic area with the highest probability in this voxel. Voxels with equal probabilities for different areas were assigned by taking the adjacent voxel probabilities of these areas into account (Eickhoff et al. 2005).

Cytoarchitectonic Similarities and Dissimilarities Between Cortical Areas as Indicated by Hierarchical Clustering of Mean Areal GLI Profiles

Hierarchical clustering analysis was conducted to detect putative groupings of the areas on the FG and surrounding regions [FG1–4, parahippocampal area1/2 (PH1/2), and inferotemporal area (IT)] based on similarities of their mean GLI profiles. For this, representative blocks with an average of 15 profiles each were extracted from 3 separate ROIs of each area and hemisphere, resulting in 45 profiles per area, hemisphere, and brain. To reduce data variability, ROIs were collected at sites where the cortex appeared to be sectioned vertical to the surface without any disturbance of the cytoarchitecture due to tangential sectioning. Mean GLI profiles were computed from the 45 profiles. They were divided into 10 equidistant units (bins), each of which corresponded to a particular fraction of the underlying cortical layer pattern in dependence on cortical depth. Mean feature vectors were generated for each area based on the mean GLI profiles.

Differences in cytoarchitectonic patterns between the areas were disclosed by a hierarchical clustering using the Euclidean distance and the Ward linkage procedures (Ward 1963). We here used the Euclidean distance instead of the MD, because it does not require information regarding variability between feature vectors. The higher the difference between cytoarchitectonic patterns of 2 cortical areas, the larger the Euclidean distance between the 2 mean areal feature vectors.

In addition to the areas analyzed in the present study and previously delineated areas of the ventral visual cortex, areas PH1/2 and IT were included; PH1/2 and IT represent 2 areas, which have not yet been systematically analyzed. However, PH1/2 and IT (1) neighbor FG3/4, (2) display different cytoarchitectonic properties than FG3/4, and (3) will be mapped to completion in a future study.

Cortical Surface Reconstructions

A combination of automated (FreeSurfer: http://surfer.nmh.harvard.edu) and manual segmentation tools (ITK-SNAP; http://white.stanford.edu/itkgray) was used to separate gray from white matter in each brain. We then reconstructed the cortical surface for each individual (Wandell et al. 2000).

Macroanatomic Landmarks in VTC

Using previously published methods (Weiner et al. 2014), we identified 3 sulci in the VTC on the cortical surfaces of all 20 hemispheres: the occipitotemporal sulcus (OTS), collateral sulcus (CoS), and MFS. We manually generated anatomical ROIs (aROIs) on the cortical surface encompassing the entire sulcus. We then measured the distance between these aROIs and each point of the FG3/FG4 boundary in a given hemisphere. It is important to stress that these measurements were calculated (1) after the FG3/FG4 boundary was determined by observer-independent methods that are ignorant of the macroanatomy and (2) that the aROIs were defined by independent observers, which did not know the location of the FG3/FG4 boundary. Thus, the cytoarchitectonic boundary was unconstrained by the macroanatomic structure. We then compared the coupling of cytoarchitectonic areas and surrounding sulci between pFG areas (FG1 and FG2) and mFG areas (FG3 and FG4) using a repeated-measures ANOVA and paired t-tests.

Results

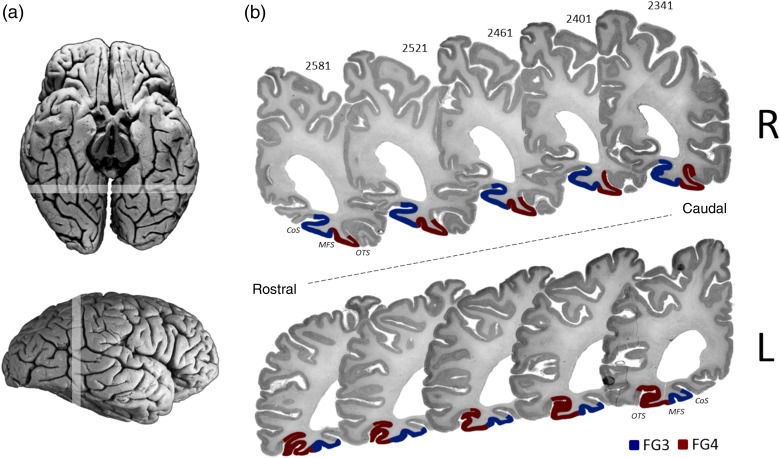

On the basis of the observer-independent algorithm and subsequent statistical analysis of GLI profiles, we demonstrated the existence of significant architectonic borders in the region of the mFG, and identified 2 new distinct cytoarchitectonic areas, FG3 and FG4. To follow the terminology introduced by Caspers, Zilles, et al. (2013), these newly identified areas on the mFG anterolateral to FG1 and FG2 were named “FG3” and “FG4” (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Sequence of 5 coronal histological sections (pm 4). (a) Dorsal and lateral views of the postmortem brain. Highlighted rostro-caudal range locates the sections presented in (b). (b) Positions of FG3 (blue) and FG4 (red) in 5 sections from caudal to rostral in both hemispheres (R: right; L: left). CoS: collateral sulcus; MFS: mid-fusiform sulcus; OTS: occipitotemporal sulcus.

Areas FG3 and FG4 occupied mainly the middle part of the mFG. Both areas were consistently separated by the MFS. The more medial area FG3 immediately adjoined FG1, rostrally extending into the CoS. The more lateral area, FG4, bordered FG3 laterally and FG2 anteriorly. FG4 encompassed parts of the OTS and rarely extended into the inferior temporal gyrus (4/20 hemispheres). FG3 is medially flanked by 2 not yet mapped areas, which were preliminary named according to their macroanatomic location: PH1 and PH2. Laterally, FG4 is adjoined by an additionally unmapped area, which we refer as IT.

Cytoarchitecture

Both areas belong to the six-layered homotypical isocortex with an inner granular layer IV. They revealed several cytoarchitectonic features, which made them distinct from each other and from neighboring areas.

Area FG3 was characterized by a relatively compact, dense layer II (Fig. 5). Layer III was subdivided into a cell-sparse sublayer IIIa/b with small pyramidal cells, forming a sharp border to layer II, and a prominent sublayer IIIc with medium-sized pyramidal cells; the latter sublayer covered approximately one-third of layer III. Layer IV of FG3 was clearly visible with little clusters of granular cells. Layers V and VI appeared rather homogeneous and showed medium-sized pyramidal cells, particularly in layer V.

Figure 5.

Cytoarchitectonic features of FG1–FG4, as well as adjacent areas (PH1/2, IT). Upper row: Lines indicate mean GLI profiles (abscissa) from 15 individual profiles. The cortical depth was normalized to 100%. FG3 (blue) is characterized by a thin layer IIIc with small- to medium-sized pyramidal cells compared with a prominent layer IIIc with medium- to large-sized cells in FG4 (red). FG4 is further characterized by a heterogeneously packed layer V/VI with a cell dense layer Va and a strip-like cell-sparse sublayer Vb, compared with a rather homogeneously distributed V/VI in FG3. The posteriorly adjoining FG1 mainly differed from FG3 by a distinct columnar arrangement of pyramidal cells in layers III and V. FG4 showed a subdivision of layer V, which could not be identified in FG2. Lower row: Cytoarchitectonic features of the neighboring areas from one representative brain (brain pm 8; cf. Table 1). Cortical layers are marked in Roman numeral. Black bar in the left lower corner: 1 mm.

Compared with FG3, the laterally adjoining area FG4 had a less densely packed layer II, which merged with the superficial aspects of layer III (Fig. 5). Similar to FG3, layer III of FG4 also showed a relatively cell-sparse layer IIIa/b with small pyramidal cells and a prominent sublayer IIIc with medium- to large-sized pyramidal cells. However, layer IIIc in FG4 was broader than in FG3 covering approximately half of layer III. The pyramidal cells of this sublayer were slightly larger. The thin inner granular layer IV of FG4 was moderately dense and did not have sharp borders with the adjacent sublayers IIIc and Va. Layer V could be divided into layers Va and Vb. Both layers contained mainly medium-sized pyramidal cells. Layer Va was cell dense, whereas layer Vb appeared as a strip-like cell-sparse sublayer. Moreover, a particularly high cell density of layer VI provided a strong contrast to layer Vb. When compared with FG3, FG4 showed less well-defined, thin bundle-like cell strings in layers III and V. Areas FG3 and FG4 appeared homogenous within both their range and borders with no substantial gradients or subdivisions.

The posteriorly adjoining FG1 mainly differed from FG3 by a pronounced columnar arrangement of cells (Fig. 5); in addition, it showed a less compact layer II with a rather smooth transition to layer III, and the pyramidal cells in layer IIIc of FG3 were slightly larger than those in FG1. Both FG1 and FG3 had no clear border between layers V and VI, yet cells of these layers in FG1 were more heterogeneously packed with small pyramidal cells in layer V and a relatively cell-sparse layer VI.

Areas FG4 and the more posteriorly located FG2 were characterized by a conspicuous layer IIIc and a rather cell-sparse layer IIIa/b, yet the pyramidal cells of FG2 were slightly larger than in FG4 and merge partially into sublayer IIIb (Fig. 5). A prominent and cell dense layer IV was characteristic for FG2, whereas layer IV of FG4 was rather thin and only moderately cell dense. Both areas exhibited a notable contrast between a cell-sparse layer V and a densely packed layer VI. However, FG4 showed a clear subdivision of layer V in a more cell dense layer Va with mostly medium cell sizes and a cell-sparse layer Vb, which was less distinct in FG2.

FG3 was medially adjoined by 2 areas, which will be cytoarchitectonically delineated in future studies. The more posteriorly adjoining area, PH1, was located in the depth of the CoS and on the lateral banks of the parahippocampal and lingual gyri. Compared with FG3, PH1 was characterized by a less compact and more blurred layer II and a broader layer IIIc with a higher number of larger pyramid cells (Fig. 5). Most strikingly, layer VI showed a prominent cell packing density distinct from layer V, which clearly distinguished PH1 from FG3.

More anteriorly, PH2 could be identified rostral to area PH1 and medial to FG3 on the lateral portion of the CoS, which continuously expanded onto the FG laterally and the parahippocampal gyrus medially. Layers V and VI of PH2 showed a homogeneously packed and cell dense layer V and VI with medium-sized cells, which could be clearly differentiated from layers V/VI of FG3 (Fig. 5). In contrast to FG3, layer III of PH2 containing small pyramidal cells was conspicuously cell sparse and did not have clear subdivisions. Layer II of PH2 was rather diffuse compared with the compact layer II of FG3

An additional area lateral to FG4, which we refer as IT, will be cytoarchitectonically analyzed and mapped in a future study. Area IT extended largely into the OTS and reached onto the medial aspects of the inferior temporal gyrus. Compared with FG4, IT had a more compact layer II with less marked transition between layers II and III (Fig. 5). Layer IIIc was marginally thinner in IT than in FG4 with slightly smaller and fewer pyramidal cells. Furthermore, layer IV of IT appeared considerably thinner with a higher cell density of granular cells and sharper borders to adjacent sublayers. Notably, layer VI of IT showed a subdivision into sublayers VIa and VIb.

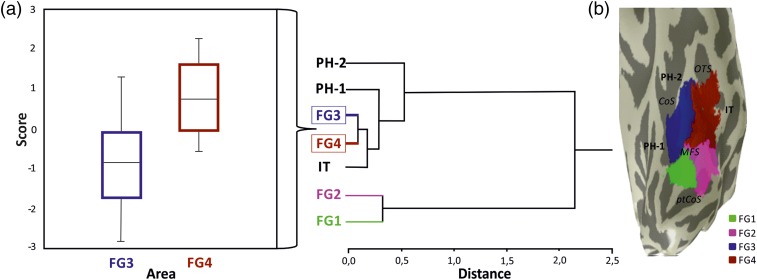

Cytoarchitectonic Similarities as Revealed by Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

The hierarchical cluster dendrogram of FG3 and FG4 together with the adjoining areas FG1, FG2, PH1, PH2, and IT reflects cytoarchitectonic differences between the areas, and groups them according to their similarities (Fig. 6a). The 10 areas were agglomerated in the sequence of their similarity, while the length of the horizontal branches indicates the Euclidean distance as a similarity measure between the areas. Areas FG3 and FG4 were most similar between each other (lowest Euclidean distance); these areas merge first. Next, IT merges with FG3/FG4, followed by PH1 and PH2. Areas FG1 and FG2 were most distinct from areas FG3 and FG4, indicating a clear cytoarchitectonic difference between areas within the mFG and pFG.

Figure 6.

Analysis of mean GLI profiles. (a) Dendrogram including FG3 and FG4 as well as the adjacent areas PH1/2, IT, FG1, and FG2. The hierarchical clustering is based on the degree of dissimilarity in the set of 10 mean areal feature vectors (bin means) of profiles by the Euclidean distance. (b) Brain no. pm 3 (cf. Table 1 and Fig. 9) representative inflated brain displaying the spatial organization of the fusiform areas (FG1–4) as well as the not yet entirely mapped adjoining areas (PH1/2 and IT). Transparency of the fusiform areas reveals the relationships with the macroanatomic landmarks. CoS: collateral sulcus; OTS: occipitotemporal sulcus; ptCoS: posterior transverse CoS; MFS: mid-fusiform sulcus.

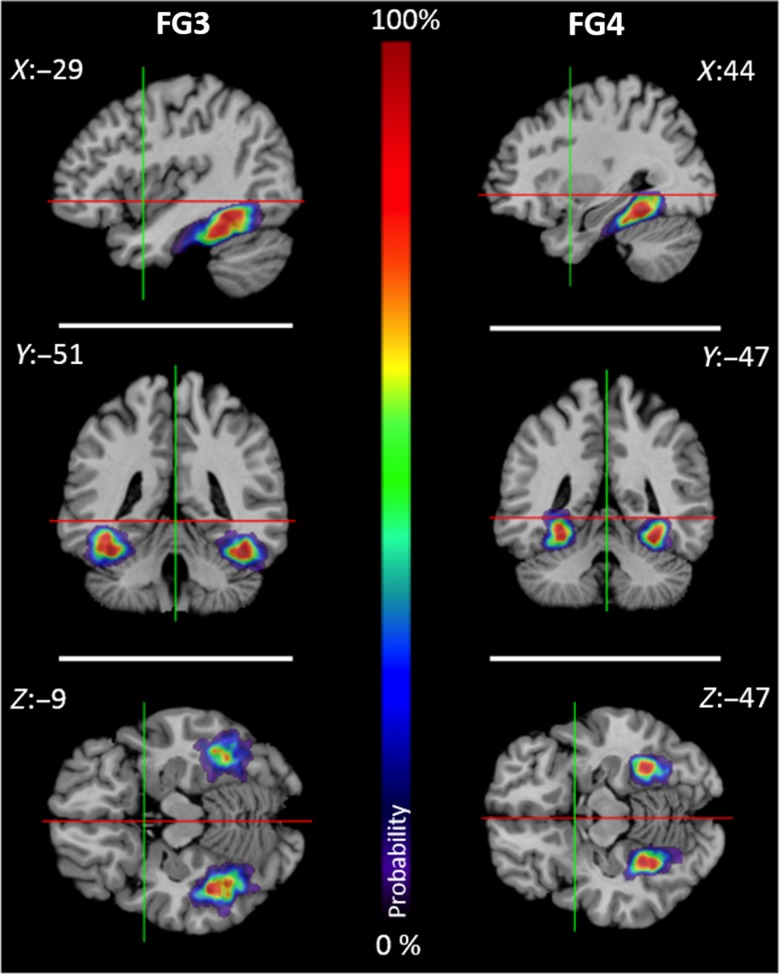

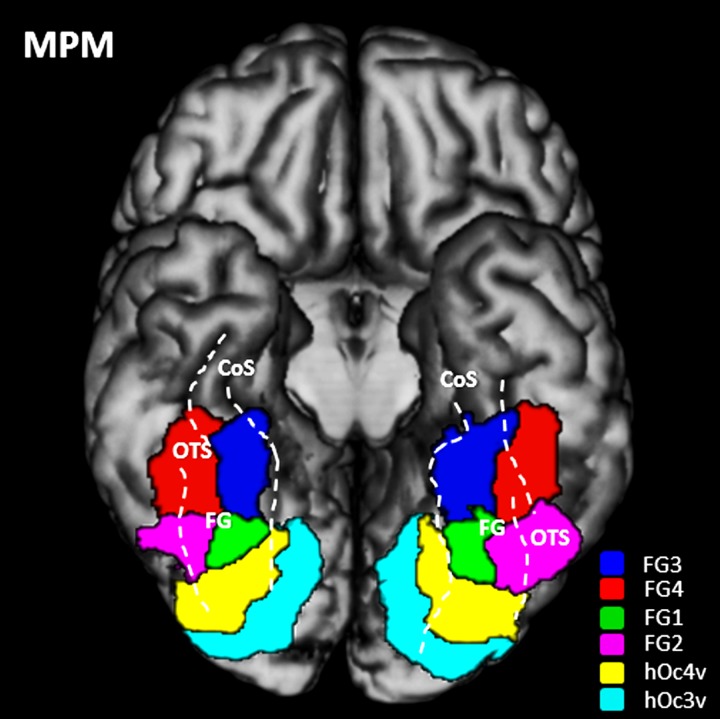

Continuous Probability Maps and MPMs

Continuous probability maps of areas FG3 and FG4 were calculated in the anatomical MNI space (Fig. 7). Both areas showed large regions of overlap (i.e., low intersubject variability) in both hemispheres, and relatively small regions with low overlap (and higher intersubject variability) in the periphery. The MPMs of areas FG3 and FG4 together with other visual areas are shown in Figure 8. Although these are “summary maps,” they adequately reflect the topography as found in each individual brain. Cytoarchitectonic maps are publicly available through the JuBrain atlas (https://jubrain.fz-juelich.de).

Figure 7.

Probabilistic maps of FG3 and FG4 in the anatomical MNI space. The voxel-based probability of overlap was color-coded. Regions of high areal overlaps (9–10 brains) were depicted in dark red. The lowest areal representation was displayed by dark blue. From top to bottom: sagittal, coronal, and horizontal sections. Red and green lines cross in x = 0 and y = 0 coordinates of the different sections.

Figure 8.

MPM of the visual cortex. The MPM is displayed on a 3D rendering of the MNI single-subject reference template without the cerebellum including hOc3v (cyan), hOc4v (yellow), FG1 (green) and FG2 (violet), FG3 (red) and FG4 (blue) (Rottschy et al. 2007; Caspers, Zilles, et al. 2013). Basal view is shown. Dashed lines highlight the position and extent of sulci delimiting the FG. FG: fusiform gyrus; CoS: collateral sulcus; OTS: occipitotemporal sulcus.

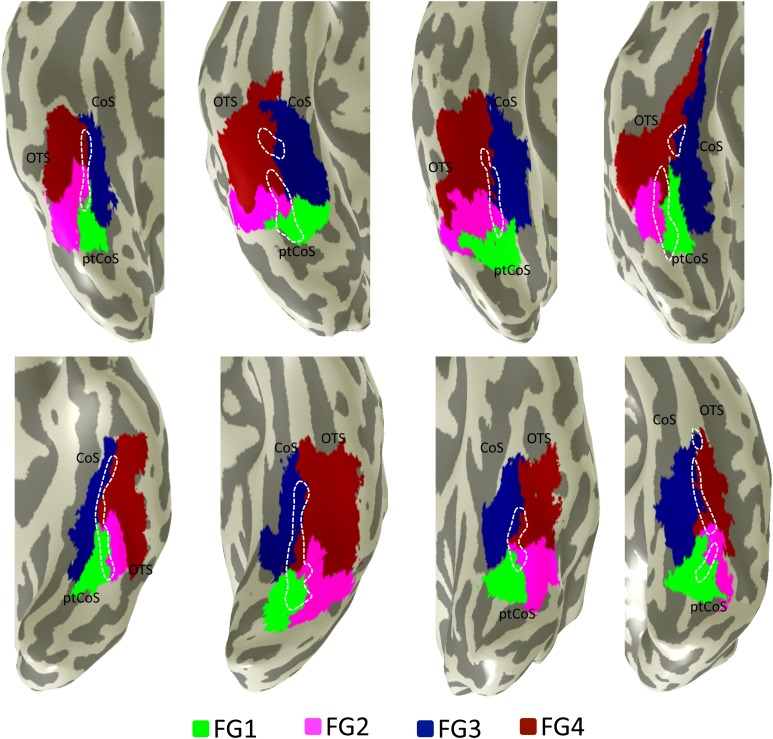

Topographical Relationship of FG3 and FG4 with Macroanatomic Landmarks

The MFS is a shallow, longitudinal sulcus that bisects the FG into lateral and medial partitions. In our prior work (Weiner et al. 2014), we demonstrated that the boundary between FG1 and FG2 occurs within the posterior MFS in a majority (18/20) of hemispheres. However, the FG1/FG2 boundary did not occur within the entirety of the MFS. Thus, in the present work, we tested if the FG3/FG4 boundary also occurred in the more anterior portions of the MFS.

The FG3/FG4 boundary was identified within the MFS in 18 of the 20 examined hemispheres (Fig. 9). The boundary is tightly coupled with the MFS, located on average 1.42 ± 0.54 mm from the MFS. The anterior extent of the FG3/FG4 boundary continues 1.76 cm ± 0.35 cm beyond the anterior tip of the MFS. Thus, the MFS is a macroanatomic landmark containing cytoarchitectonic borders among 4 regions: FG3/FG4 anteriorly and FG1/FG2 posteriorly (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

The cytoarchitectonic transition between FG3 and FG4 occurs within the MFS. Cytoarchitectonic regions FG1 (green), FG2 (magenta), FG3 (blue), and FG4 (red) projected to the inflated cortical surface of individual right (top) and left (bottom) hemispheres. The border between FG3 and FG4 occurs within the anterior MFS (dotted line), whereas the border between FG1 and FG2 occurs within the posterior MFS. CoS: collateral sulcus; OTS: occipitotemporal sulcus; ptCoS: posterior transverse CoS. The brains included in this image are from left to right: top: pm 10, pm 9, pm 8, and pm 7; bottom: pm 10, pm 4, pm 3, and pm 1 (cf. Table 1).

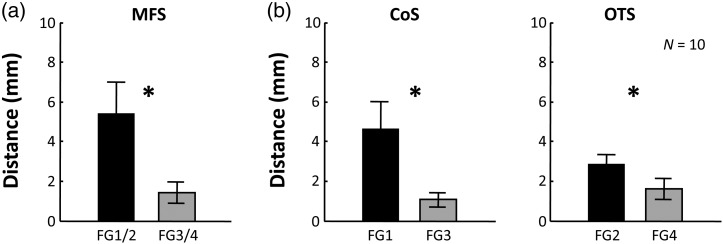

Additional anatomical landmarks, the CoS and OTS, were coupled with the lateral boundary of FG4 and the medial boundary of FG3, respectively. Specifically, the distance between the medial boundary of FG3 and the CoS was 1.07 ± 0.36 mm. The distance between the lateral boundary of FG4 and the OTS was on average 1.61 ± 0.27 mm. Comparatively, the FG1/FG2 boundary was within 5.41 ± 1.59 mm from the MFS (Weiner et al. 2014); the medial boundary of FG1 was 4.66 ± 0.13 mm apart from the CoS; and the lateral boundary of FG2 was 2.88 ± 0.45 mm distant from the OTS (Fig. 10). A two-way ANOVA with landmark (MFS/CoS/OTS) and region (FG1/FG2/FG3/FG4) as factors yielded a main effect of region (F1.59 = 17.6, P < 0.001), indicating that FG3 and FG4 were more tightly coupled with sulci in VTC than FG1 and FG2.

Figure 10.

Tighter coupling between cortical folding and cytoarchitectonic boundaries of FG3 and FG4 compared with FG1 and FG2. (a) Distance (mm) between cytoarchitectonic transition and the MFS. (b) Left: Distance between medial boundaries of FG1 and FG3, respectively, and the CoS. Right: Distance between lateral boundaries of FG2 and FG4, respectively, and the OTS. *P < 10−4.

Discussion

The present study identified 2 new cytoarchitectonic areas of the mid-FG: FG3 (medial) and FG4 (lateral). Both areas were found throughout the investigated sample in both hemispheres. Combined with more the delineated areas FG1 and FG2 (Caspers, Zilles, et al. 2013) in the pFG, the 4 FG areas cover approximately the posterior two-thirds of the FG. It should be stressed that all of the cytoarchitectonical borders, inner and outer, were consistently mapped employing the same observer-independent method and applying the same statistical criteria. In addition, we applied further statistical methods (cluster analysis) to address the distinctiveness of adjacent cytoarchitectonic areas.

We provide cytoarchitectonic parcellations of the pFG and mFG as a new stereotaxic map that reflects the intersubject and interhemispheric variability (Fig. 7). These maps can be used in the future to study the relationships between the microscopic segregation of the cortex and its functional involvement in ventral stream processing on a sound anatomical basis. In the sections below, we discuss (1) the present cytoarchitectonic parcellation of the FG in the context of prior divisions from classic cytoarchitectonic studies, (2) the relationship between FG1–4 and large-scale functional parcellations of VTC, and (3) the relationship between FG1–4 and fine-scale functional parcellations of VTC.

Relating FG3 and FG4 to Maps of Brodmann and von Economo and Koskinas

Compared with the cytoarchitectonic map of Brodmann (1909), FG3/FG4 is located within Brodmann Area 37 (BA37) and partly BA20 (Fig. 1). Specifically, areas FG3 and FG4 do not match the segregation as presented in Brodmann's drawing of a map. Brodmann described BA37 as a large transitional region between temporal and occipital regions with rather unclear and only vaguely discernable borders to the adjoining areas (Brodmann 1909). Using our established observer-independent quantitative mapping approach, we were able to discover further partitioning of this incompletely described cortical region. Crucially, this method also provided reproducible borders of additional regions that were unidentified in Brodmann's map.

Compared with the map of von Economo and Koskinas (1925), areas FG3/FG4 are roughly located within the “area fusiformis” (TF) and the “Area parietalis temporooccipitalis” (PH). von Economo and Koskinas described these regions as clearly distinguishable from adjacent temporal and hippocampal areas with rather smooth transitions in-between each. Still, they particularly mentioned “TF” as one large cytoarchitectonic area spanning the range of mFG and aFG. Interestingly, “PH” merges medially onto the FG in the more posterior part of the mFG, which likewise indicates a “transitional” bipartition of this cortical region, yet, to a different extent compared with our parcellation. In accordance with von Economo's and Koskina's descriptions of “PH” we also found strikingly homogenous layers V/VI in FG3. Moreover, the detailed description of “TF” shows great similarities with the characteristics of FG4—in particular, the relatively light layer V with a clear demarcation to layer VI as well as the particular cell packing in layer III with mainly medium-sized pyramidal cells and a rather loose layer IV are similarly found in the description of von Economo and Koskinas. However, the light radial columns in layer III of “TF” (von Economo and Koskinas 1925) were inconsistently present in FG4. Though a description of the MFS is not included in their original study, it is also interesting to note that in the summary schematic of von Economo and Koskinas (Fig. 1), the transition between PH and TF occurs in the posterior portion of a sulcus within the pFG. While they do not mention the MFS, this transition is consistent with the present parcellation where FG1/2 composes a part of the posterior area PH and FG3/4 composes a part of the anterior area TF.

Relationship Between Areas FG1–4 and Large-Scale Functional Parcellations of VTC

In prior work, we showed that the border between FG1 and FG2 was well predicted by the MFS (Weiner et al. 2014). In the present study, we demonstrate that this relationship extends to the mFG, where the MFS also predicts the border between areas FG3 and FG4. From a macroscopic perspective, we extend these measurements also to the OTS and CoS, showing that the lateral borders of FG2/4 are well predicted by the OTS and the medial borders of FG1/3 are well predicted by the CoS. Interestingly, there are many large-scale functional representations that are implemented in VTC with similar lateral (OTS) and medial (CoS) borders. For example, representations of eccentricity bias (foveal vs. peripheral; Levy et al. 2001; Hasson et al. 2002; Malach et al. 2002), domain specificity (faces vs. places; Kanwisher, Woods, et al. 1997; Epstein and Kanwisher 1998), animacy (animate vs. inanimate; Haxby et al. 2011), and real-world object size (small vs. large; Talia Konkle 2012) are each implemented as large-scale maps with lateral–medial trajectories in the VTC (Grill-Spector and Weiner 2014). Overall, we can hypothesize that FG2/4 on the lateral FG is likely to overlap the face, animacy, small objects, and foveal bias representations. Area FG1/3, which are medial to the MFS and extend to the CoS, probably overlaps with place, inanimate, large objects, and peripheral representations.

Interestingly, the hierarchical cluster analysis of cytoarchitectonic features grouped together areas FG3/4 as well as FG1/2, which is “orthogonal” to functional similarities emphasizing similarity for FG1/3 as well as FG2/4. Cytoarchitectonic similarities between FG2 and FG4 were nonetheless found: both contained a conspicuous layer IIIc and a rather cell-sparse layer IIIa/b. The same is true for FG1/3: both showed a rather unsharp border between layers V and VI. While the cluster analysis considered features extracted from the GLI profile over its full extent as a global measure of cytoarchitecture, individual features like the structure of layer III or the layering of infragranular layers V/VI may have functional implications, relevant for the analysis of fMRI contrasts. Such similarities may contribute to the widely documented large-scale maps in the VTC that also show lateral–medial topologies just discussed (Weiner et al. 2014). Further anatomical analyses, such as myeloarchitecture (Clarke and Miklossy 1990; Sereno et al. 2013; Abdollahi et al. 2014; Glasser et al. 2014; Van Essen and Glasser 2014) and receptor architecture (Zilles and Amunts 2009; Caspers, Palomero-Gallagher, et al. 2013) may further shed light on these correspondences in future studies.

Functional Significance of FG2 and FG4 for Face and Word Processing in Lateral VTC

While we consider the similarities between lateral (FG2/4) and medial (FG1/3) cytoarchitectonic areas, it is the difference between them that may help explain the fine-scale functional heterogeneity of VTC. For example, in lateral VTC, different portions of the OTS predict the fusiform body area also known as OTS limbs (Peelen and Downing 2005; Schwarzlose et al. 2005; Weiner and Grill-Spector 2010) and the visual word form area (VWFA; Cohen et al. 2002 ; Cohen and Dehaene 2004; Wandell et al. 2012; Yeatman et al. 2013). Caspers, Zilles, et al. (2013) proposed that the VWFA, which is lateralized mainly in the left OTS extending into the lateral FG, was located 1 cm anterior to the left FG2, making it likely that the VWFA is partially located within the left FG4 (Cohen and Dehaene 2004; Dehaene et al. 2010; Wandell et al. 2012). In this scheme, FG2 seems to be involved in reading at an intermediate level such as processing the visual form of words (Szwed et al. 2011; Caspers, Zilles, et al. 2013, Caspers et al. 2014). As opposed to the idea of regions rather explicitly devoted to reading, another recent theory hypothesizes that reading is supported by less specific polymodal functional areas along the lateral ventral stream (Price and Devlin 2003, 2011; Devlin et al. 2006). This basic approach characterized the ventral occipitotemporal cortex as “an interface between bottom-up sensory inputs and top-down predictions” integrating also stimuli from different sensory modalities (e.g., tactile and auditory). Accordingly, areas FG4 and FG2 are probably part of a complex system of word recognition within the ventral visual cortex. In particular, the medium- to large-sized pyramidal cells within the prominent layer IIIc indicate strong cortico-cortical connectivity, which points toward “top-down” inputs and would be well in line with the aforementioned functional notions.

Also in lateral VTC, the MFS anatomically dissociates different portions of the fusiform face area (FFA; Kanwisher, McDermott, et al. 1997; Grill-Spector et al. 2004; Saygin et al. 2012). In particular, the anterior tip of the MFS reliably identifies mFus-faces/FFA-2, which is 1–1.5 cm anterior to pFus-faces/FFA-1 (Pinsk et al. 2009; Weiner and Grill-Spector 2010; Caspers et al. 2014; Weiner et al. 2014). FG2 never extends to the anterior tip of the MFS, whereas FG4 always extends to and often exceeds the anterior tip of the MFS. Consequently, it is likely that mFus-faces/FFA-2 falls within FG4, whereas pFus-faces/FFA-1 falls within FG2. The overall assumption of multiple circumscribed face patches is further substantiated by evidences from comparative homology studies in macaques (Tsao et al. 2003, 2006, 2008; Freiwald and Tsao 2010). However, because each cytoarchitectonic area is apparently larger than any one of these functional clusters, it is likely that each cytoarchitectonic area is involved in multiple functional domains and contains additional functional clusters as we previously proposed (Grill-Spector and Weiner 2014).

Relationship Between FG1 and FG3 with Retinotopic Maps and Scene Processing in Medial VTC

The macroanatomic framework and stereotaxic map provided in the present study can also serve as a guide for future studies examining the correspondence between cytoarchitectonic and fine-scale functional parcellations of medial VTC. For example, the CoS reliably predicts the location of the parahippocampal place area (CoS-places/PPA; Nasr et al. 2011). Our present measurements indicate a tight coupling between the medial boundary of FG3 and the CoS. Thus, future work examining the location of the PPA relative to the branching of the CoS will be able to shed light on the relationship between FG3 and CoS-places/PPA. As CoS-places/PPA also contains many retinotopic maps, it is likely that FG3 also contains more than one retinotopic area (Brewer et al. 2005; Wandell et al. 2007; Arcaro et al. 2009).

This implies, however, that a simple one-to-one relationship of cytoarchitectonic areas with functionally defined units may not be true throughout all functional systems. Rather, different scenarios might be considered: (1) There is a common computation that is shared across functional ROIs, requiring a particular “neural hardware.” However, there is still a gap between our concepts of a brain function as measured in an fMRI experiment and the underlying “computation,” which may better fit to cytoarchitectonic segregation. (2) There may be additional differences in the architecture, that is, the neural hardware within FG4 and FG3, perhaps generating finer partitions corresponding to the different functional ROIs, and these may be found using additional measures such as myeloarchitecture, receptor architecture, connectivity, or other aspects of cortical organization. (3) Functional experiments might not use the identical levels of categories and tasks to reveal cortical segregation, and therefore result in a different granularity of cortical segregation. (4) Brodmann's concept that every cytoarchitectonic area subserves a certain function has to be (partly) revisited [see also Weiner and Zilles (2015)].

In conclusion, the here presented cytoarchitectonic segregation of the mFG facilitates comparison to functional data. Similar to areas FG1 and FG2, the MFS serves as a consistent macroanatomic landmark between areas FG3 and FG4 and enables the identification of cortical areas underlying visual processing with high spatial accuracy. Furthermore, the cytoarchitectonic bipartition into medial and lateral areas on the FG is in agreement with widely documented large-scale lateral-to-medial functional distinctions. In lateral VTC, it is likely that FG2 and FG4 contribute to face and word processing. In medial VTC, FG1 and FG3 probably contribute to scene processing. Taken together, these new cytoarchitectonic subdivisions of the FG explain the large-scale and fine-scale functional heterogeneity of human VTC much better than the classic cytoarchitectonic maps.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 604102 (Human Brain Project).

Notes

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Abdollahi RO, Kolster H, Glasser MF, Robinson EC, Coalson TS, Dierker D, Jenkinson M, Van Essen DC, Orban GA. 2014. Correspondences between retinotopic areas and myelin maps in human visual cortex. NeuroImage. 99:509–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Kedo O, Kindler M, Pieperhoff P, Mohlberg H, Shah NJ, Habel U, Schneider F, Zilles K. 2005. Cytoarchitectonic mapping of the human amygdala, hippocampal region and entorhinal cortex: intersubject variability and probability maps. Anat Embryol (Berl). 210:343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Malikovic A, Mohlberg H, Schormann T, Zilles K. 2000. Brodmann's areas 17 and 18 brought into stereotaxic space-where and how variable? NeuroImage. 11:66–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Zilles K. 2001. Advances in cytoarchitectonic mapping of the human cerebral cortex. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 11:151–169, vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Armstrong E, Malikovic A, Homke L, Mohlberg H, Schleicher A, Zilles K. 2007. Gender-specific left-right asymmetries in human visual cortex. J Neurosci. 27:1356–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcaro MJ, McMains SA, Singer BD, Kastner S. 2009. Retinotopic organization of human ventral visual cortex. J Neurosci. 29:10638–10652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey P, von Bonin G. 1951. The isocortex of man. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels PH. 1979. Numerical evaluation of cytologic data: II. Comparison of profiles. Anal Quant Cytol. 1:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bludau S, Eickhoff SB, Mohlberg H, Caspers S, Laird AR, Fox PT, Schleicher A, Zilles K, Amunts K. 2014. Cytoarchitecture, probability maps and functions of the human frontal pole. NeuroImage. 93(Pt 2):260–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H. 1977. The pigment architecture of the human occipital lobe. Anat Embryol (Berl). 150:229–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H. 1978. The pigment architecture of the human temporal lobe. Anat Embryol (Berl). 154:213–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer AA, Liu J, Wade AR, Wandell BA. 2005. Visual field maps and stimulus selectivity in human ventral occipital cortex. Nat Neurosci. 8:1102–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K. 1906. Beiträge zur histologischen Lokalisation des Grosshirnrinde: Fünfte Mitteilung: Über den allgemeinen Bauplan des Cortex Pallii bei den Mammaliern und zwei homologe Rindenfelder im besonderen. Zugleich ein Beitrag zur Furchenlehre. Leipzig: Barth. [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K. 1909. Vergleichende Lokalisationslehre der Großhirnrinde. Leipzig: Barth. [Google Scholar]

- Caspers J, Palomero-Gallagher N, Caspers S, Schleicher A, Amunts K, Zilles K. 2013. Receptor architecture of visual areas in the face and word-form recognition region of the posterior fusiform gyrus. Brain Struct Funct. 2201:205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers J, Zilles K, Amunts K, Laird AR, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB. 2014. Functional characterization and differential coactivation patterns of two cytoarchitectonic visual areas on the human posterior fusiform gyrus. Hum Brain Mapp. 35:2754–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers J, Zilles K, Eickhoff SB, Schleicher A, Mohlberg H, Amunts K. 2013. Cytoarchitectonical analysis and probabilistic mapping of two extrastriate areas of the human posterior fusiform gyrus. Brain Struct Funct. 218:511–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S, Miklossy J. 1990. Occipital cortex in man: organization of callosal connections, related myelo- and cytoarchitecture, and putative boundaries of functional visual areas. J Comp Neurol. 298:188–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Dehaene S. 2004. Specialization within the ventral stream: the case for the visual word form area. NeuroImage. 22:466–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Dehaene S, Naccache L, Lehericy S, Dehaene-Lambertz G, Henaff MA, Michel F. 2000. The visual word form area: spatial and temporal characterization of an initial stage of reading in normal subjects and posterior split-brain patients. Brain. 123(Pt 2):291–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Lehéricy S, Chochon F, Lemer C, Rivaud S, Dehaene S. 2002. Language-specific tuning of visual cortex? Functional properties of the visual word form area. Brain Lang. 125:1054–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Pegado F, Braga LW, Ventura P, Nunes Filho G, Jobert A, Dehaene-Lambertz G, Kolinsky R, Morais J, Cohen L. 2010. How learning to read changes the cortical networks for vision and language. Science. 330:1359–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JT, Jamison HL, Gonnerman LM, Matthews PM. 2006. The role of the posterior fusiform gyrus in reading. J Cogn Neurosci. 18:911–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Heim S, Zilles K, Amunts K. 2006. Testing anatomically specified hypotheses in functional imaging using cytoarchitectonic maps. NeuroImage. 32:570–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Stephan KE, Mohlberg H, Grefkes C, Fink GR, Amunts K, Zilles K. 2005. A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. NeuroImage. 25:1325–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Harris A, Stanley D, Kanwisher N. 1999. The parahippocampal place area: recognition, navigation, or encoding? Neuron. 23:115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Kanwisher N. 1998. A cortical representation of the local visual environment. Nature. 392:598–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AC, Janke AL, Collins DL, Baillet S. 2012. Brain templates and atlases. NeuroImage. 62:911–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AC, Marrett S, Neelin P, Collins L, Worsley K, Dai W, Milot S, Meyer E, Bub D. 1992. Anatomical mapping of functional activation in stereotactic coordinate space. NeuroImage. 1:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiwald WA, Tsao DY. 2010. Functional compartmentalization and viewpoint generalization within the macaque face-processing system. Science. 330:845–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser MF, Goyal MS, Preuss TM, Raichle ME, Van Essen DC. 2014. Trends and properties of human cerebral cortex: correlations with cortical myelin content. NeuroImage. 93(Pt 2):165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Knouf N, Kanwisher N. 2004. The fusiform face area subserves face perception, not generic within-category identification. Nat Neurosci. 7:555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Weiner KS. 2014. The functional architecture of the ventral temporal cortex and its role in categorization. Nat Rev Neurosci. 15:536–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson U, Levy I, Behrmann M, Hendler T, Malach R. 2002. Eccentricity bias as an organizing principle for human high-order object areas. Neuron. 34:479–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby J, Guntupalli J, Connolly A, Halchenko Y, Conroy B, Gobbini M, Hanke M, Ramadge P. 2011. A common, high-dimensional model of the representational space in human ventral temporal cortex. Neuron. 72:404–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Gobbini MI, Furey ML, Ishai A, Schouten JL, Pietrini P. 2001. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science. 293:2425–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hömke L. 2006. A multigrid method for anisotropic PDEs in elastic image registration. Numer Linear Algebr Appl. 13:215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Ishai A, Ungerleider LG, Martin A, Schouten JL, Haxby JV. 1999. Distributed representation of objects in the human ventral visual pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 96:9379–9384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. 1997. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J Neurosci. 17:4302–4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, Woods RP, Iacoboni M, Mazziotta JC. 1997. A locus in human extrastriate cortex for visual shape analysis. J Cogn Neurosci. 9:133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappers CUA. 1913. Cerebral localization and the significance of sulci. London: International Congress of medical Science. [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz DJ, Saleem KS, Baker CI, Ungerleider LG, Mishkin M. 2013. The ventral visual pathway: an expanded neural framework for the processing of object quality. Trends Cogn Sci. 17:26–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujovic M, Zilles K, Malikovic A, Schleicher A, Mohlberg H, Rottschy C, Eickhoff SB, Amunts K. 2013. Cytoarchitectonic mapping of the human dorsal extrastriate cortex. Brain Struct Funct. 218:157–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy I, Hasson U, Avidan G, Hendler T, Malach R. 2001. Center-periphery organization of human object areas. Nat Neurosci. 4:533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalanobis PC, Majumdar DN, Yeatts MWM, Rao CR. 1949. Anthropometric survey of the United Provinces, 1941: a statistical study. Sankhyā. 9:89–324. [Google Scholar]

- Malach R, Levy I, Hasson U. 2002. The topography of high-order human object areas. Trends Cogn Sci. 6:176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merker B. 1983. Silver staining of cell bodies by means of physical development. J Neurosci Methods. 9:235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner AD, Goodale MA. 2008. Two visual systems re-viewed. Neuropsychologia. 46:774–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr S, Liu N, Devaney KJ, Yue X, Rajimehr R, Ungerleider LG, Tootell RB. 2011. Scene-selective cortical regions in human and nonhuman primates. J Neurosci. 31:13771–13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peelen MV, Downing PE. 2005. Selectivity for the human body in the fusiform gyrus. J Neurophysiol. 93:603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsk MA, Arcaro M, Weiner KS, Kalkus JF, Inati SJ, Gross CG, Kastner S. 2009. Neural representations of faces and body parts in macaque and human cortex: a comparative fMRI study. J Neurophysiol. 101:2581–2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Devlin JT. 2011. The interactive account of ventral occipitotemporal contributions to reading. Trends Cogn Sci. 15:246–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Devlin JT. 2003. The myth of the visual word form area. NeuroImage. 19:473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottschy C, Eickhoff SB, Schleicher A, Mohlberg H, Kujovic M, Zilles K, Amunts K. 2007. Ventral visual cortex in humans: cytoarchitectonic mapping of two extrastriate areas. Hum Brain Mapp. 28:1045–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisov S, Filimonoff IN, Preobrashenskaya NS. 1949. Cytoarchitecture of the human cortex cerebri. Moscow: Medgiz; [in Russian]. [Google Scholar]

- Saygin ZM, Osher DE, Koldewyn K, Reynolds G, Gabrieli JD, Saxe RR. 2012. Anatomical connectivity patterns predict face selectivity in the fusiform gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 15:321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher A, Amunts K, Geyer S, Morosan P, Zilles K. 1999. Observer-independent method for microstructural parcellation of cerebral cortex: a quantitative approach to cytoarchitectonics. NeuroImage. 9:165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher A, Morosan P, Amunts K, Zilles K. 2009. Quantitative architectural analysis: a new approach to cortical mapping. J Autism Dev Disord. 39:1568–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher A, Palomero-Gallagher N, Morosan P, Eickhoff SB, Kowalski T, de Vos K, Amunts K, Zilles K. 2005. Quantitative architectural analysis: a new approach to cortical mapping. Anat Embryol (Berl). 210:373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher A, Zilles K. 1990. A quantitative approach to cytoarchitectonics: analysis of structural inhomogeneities in nervous tissue using an image analyser. J Microsc. 157:367–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzlose RF, Baker CI, Kanwisher N. 2005. Separate face and body selectivity on the fusiform gyrus. J Neurosci. 25:11055–11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno MI, Lutti A, Weiskopf N, Dick F. 2013. Mapping the human cortical surface by combining quantitative T(1) with retinotopy. Cereb Cortex. 23:2261–2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szwed M, Dehaene S, Kleinschmidt A, Eger E, Valabregue R, Amadon A, Cohen L. 2011. Specialization for written words over objects in the visual cortex. NeuroImage. 56:330–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia Konkle AO. 2012. A real-world size organization of object responses in occipito-temporal cortex. Neuron. 74:1114–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JC, Downing PE. 2011. Division of labor between lateral and ventral extrastriate representations of faces, bodies, and objects. J Cogn Neurosci. 23:4122–4137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao DY, Freiwald WA, Knutsen TA, Mandeville JB, Tootell RB. 2003. Faces and objects in macaque cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. 6:989–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao DY, Freiwald WA, Tootell RB, Livingstone MS. 2006. A cortical region consisting entirely of face-selective cells. Science. 311:670–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao DY, Moeller S, Freiwald WA. 2008. Comparing face patch systems in macaques and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 105:19514–19519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider LG, Haxby JV. 1994. “What” and “where” in the human brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 4:157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC, Glasser MF. 2014. In vivo architectonics: a cortico-centric perspective. NeuroImage. 93(Pt 2):157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Economo C, Koskinas GN. 1925. Die Cytoarchitektonik der Hirnrinde des erwachsenen Menschen. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wandell BA, Chial S, Backus BT. 2000. Visualization and measurement of the cortical surface. J Cogn Neurosci. 12:739–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandell BA, Dumoulin SO, Brewer AA. 2007. Visual field maps in human cortex. Neuron. 56:366–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandell BA, Rauschecker AM, Yeatman JD. 2012. Learning to see words. Annu Rev Psychol. 63:31–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner KS, Golarai G, Caspers J, Chuapoco MR, Mohlberg H, Zilles K, Amunts K, Grill-Spector K. 2014. The mid-fusiform sulcus: a landmark identifying both cytoarchitectonic and functional divisions of human ventral temporal cortex. NeuroImage. 84:453–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JH. 1963. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J Am Stat Assoc. 58:236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner KS, Grill-Spector K. 2010. Sparsely-distributed organization of face and limb activations in human ventral temporal cortex. NeuroImage. 52:1559–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner KS, Zilles K. forthcoming2015. The anatomical and functional specialization of the fusiform gyrus. Neuropsychologia. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wree A, Schleicher A, Zilles K. 1982. Estimation of volume fractions in nervous tissue with an image analyzer. J Neurosci Methods. 6:29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeatman JD, Rauschecker AM, Wandell BA. 2013. Anatomy of the visual word form area: adjacent cortical circuits and long-range white matter connections. Brain Lang. 125:146–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Amunts K. 2010. Centenary of Brodmann's map—conception and fate. Nat Rev Neurosci. 11:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Amunts K. 2009. Receptor mapping: architecture of the human cerebral cortex. Curr Opin Neurol. 22:331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Schleicher A, Palomero-Gallagher N, Amunts K. 2002. 21—Quantitative analysis of cyto- and receptor architecture of the human brain. In: Mazziotta AWTC, editor. Brain Mapping: The Methods. 2nd ed San Diego: Academic Press; p. 573–602. [Google Scholar]