ABSTRACT

Objectives:

to evaluate the evidence from the literature regarding the effects of cupping therapy on chronic back pain in adults, the most used outcomes to evaluate this condition, the protocol used to apply the intervention and to investigate the effectiveness of cupping therapy on the intensity of chronic back pain.

Method:

systematic review and meta-analysis carried out by two independent researchers in national and international databases. Reference lists of systematic reviews were also explored. The quality of evidence was assessed according to the Jadad scale.

Results:

611 studies were identified, of which 16 were included in the qualitative analysis and 10 in the quantitative analysis. Cupping therapy has shown positive results on chronic back pain. There is no standardization in the treatment protocol. The main assessed outcomes were pain intensity, physical incapacity, quality of life and nociceptive threshold before the mechanical stimulus. There was a significant reduction in the pain intensity score through the use of cupping therapy (p = 0.001).

Conclusion:

cupping therapy is a promising method for the treatment of chronic back pain in adults. There is the need to establish standardized application protocols for this intervention.

Descriptors: Review, Chronic Pain, Back Pain, Cupping Therapy, Meta-Analysis, Nursing

Introduction

Chronic back pain causes physical, emotional and socioeconomic changes 1 - 3 and, consequently, high use of medicines and health resources 4 . The search for demedicalization leads to an increasing use of integrative and complementary practices, such as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) resources, to complement pain-related allopathic care 5 . Cupping therapy is one of the recommended TCM therapies for chronic pain reduction 6 . It involves the application of cups of different materials 7 in an acupoint or area of pain by means of heat or vacuum apparatus 8 .

The effect on pain reduction has not yet been fully elucidated 9 , but different mechanisms of action, based on several assumptions 10 , are attributed to cupping therapy, such as the metabolic, neuronal hypotheses 9 , 11 and TCM 12 . Evidence of the efficacy of this intervention is limited because of the lack of high quality, well-delineated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) 6 that result in validated and efficient protocols for the treatment of chronic back pain. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the literature evidence regarding the effects of cupping therapy on chronic back pain in adults compared to sham, active treatment, waiting list, standard medical treatment or no treatment, outcomes most commonly used to assess this condition, the protocol used to apply the intervention and subsequently investigate the effectiveness of cupping therapy on the intensity of chronic back pain.

Method

A systematic review of the literature was performed, followed by meta-analysis, used to determine the intensity of back pain in adult clients. The study was based on the criteria of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes (PRISMA Statement) 13 .

The PICO (P - population; I - intervention; C - comparison; O - outcomes) 14 guided the elaboration of the guiding question: “What are the effects of cupping therapy on adults with chronic back pain?”

The search strategy, carried out by two independent reviewers from June 2017 to May 2018 was based on the following databases: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) via the US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health (PUBMED), Web of Science, The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), Embase, Scopus, as well as databases indexed in the Virtual Health Library (VHL), such as Latin American & Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) and the National Information Center of Medical Sciences of Cuba (CUMED). Reference lists of systematic reviews were also explored in the search for relevant studies related to the guiding question.

The terms, controlled and free, were combined by means of the Boolean operators OR and AND as follows: (“Back Pain” OR “Low Back Pain” OR “Sciatica” OR “Chronic Pain” OR “Musculoskeletal Pain” OR Myalgia OR “Neck Pain” OR “Low Back Pains” OR “Musculoskeletal Pains” OR “Muscle Pain” OR “Neck Pains” OR “Cervical Pain” OR “Cervical Pains” OR Lumbago OR “lumbar pain”) AND (“cupping therapy” OR cupping OR cups).

The eligibility criteria for the selection of articles were: RCT with adults (18 years or older); chronic pain (for three months or more) 15 in at least one of the segments of the spine (cervical, thoracic and/or lumbar); use of cupping therapy (dry, wet, massage, flash) 7 compared to one or more of the following groups: sham, active treatment, waiting list, standard medical treatment, or no treatment. We excluded studies that did not present online abstract in full for analysis, those that were not located by any means and studies with pregnant women.

In order to collect the information from the selected studies, we used an adapted form 16 in accordance with the recommendations of the Revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) 17 and the classifications of cupping therapy 7 , 18 .

The following data were extracted: article identification (title, author (s)/training area, journal, year of publication, study country/language); objectives; methodological characteristics (design, sample size and loss of follow-up; inclusion and exclusion criteria); clinical data (number of patients by sex, mean age, diagnosis, duration of symptoms); description of interventions in the follow-up groups (number of sessions, duration of treatment, type of technique applied (dry, wet, flash or massage cupping), application device, time of stay of the device, suction method (manual, fire, automatic-electric)/suction strength (light, medium, strong or pulsating) 18 ; peculiarities of the intervention; application points; training area of the professional who carried out the intervention; years of experience in the area); outcomes and methods of evaluation (number of evaluations, intervals between them, measurement tools); data analysis; main results; and study findings.

The methodological quality of eligible studies was assessed using the Jadad scale 19 , which is centered on internal validity. The questions have a yes/no answer option with a total score of five points: three times one point for the yes responses and two additional points for appropriate randomization and concealment of allocation methods. Two independent reviewers conducted the evaluation, and a third investigator was consulted to solve possible disagreements.

Data analyzes were performed using Stata SE/12.0 statistical software. The absolute difference between means with 95% confidence intervals was selected to describe the mean differences between the treated and control groups in the evaluation performed shortly after treatment. P-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Potential heterogeneity among the studies was examined using Cochran Q 20 and I2( 21 statistics. Since there was statistical significance in the test for heterogeneity of the results (p <0.05) and the calculated value of I2 suggested a moderate to high heterogeneity (67.7%) 21 , the random effects model was adopted for the analysis.

Results

A total of 614 studies were found in electronic and manual searches. Of these, 296 were removed from the list because they were duplicates. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 265 studies were excluded and 53 remained for analysis of the full text. Of these, 11 studies were not found (online, via bibliographic switching or direct contact with authors) and 26 articles were excluded. Finally, 16 articles remained in the review for the synthesis of the qualitative analysis and 10 articles entered the quantitative analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of literature search and selection process. Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, 2018.

*n - Number of articles; †MEDLINE - Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online; ‡PUDMED - US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health; §PEDRO - Physiotherapy Evidence Database; ||CINAHL - The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; ¶LILACS - Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature; **VHL - Virtual Health Library; ††CUMED - National Information Center of Medical Sciences of Cuba; ‡‡RCT - Randomized Clinical Trial

All articles selected were published in English language and were conducted in Germany 9 , 22 - 27 , Taiwan 28 - 30 , Iran 31 - 33 , South Korea 34 - 35 and in Saudi Arabia 36 . Participants were a total of 1049 people, aged between 18 and 79 years, of whom 519 were in the groups receiving the experimental therapy and 530 in the control groups (sham, waiting list, standard medical treatment/active treatment or no treatment). Of these, all had chronic pain conditions 15 , being the cervical spine/neck the most affected area 9 , 23 - 27 , 29 , 34 , followed by the lumbar region 22 , 28 , 30 - 33 , 35 - 36 . Two other studies 31 , 33 , although they did not make clear the temporality of the pain, were selected because this information could be inferred with great accuracy.

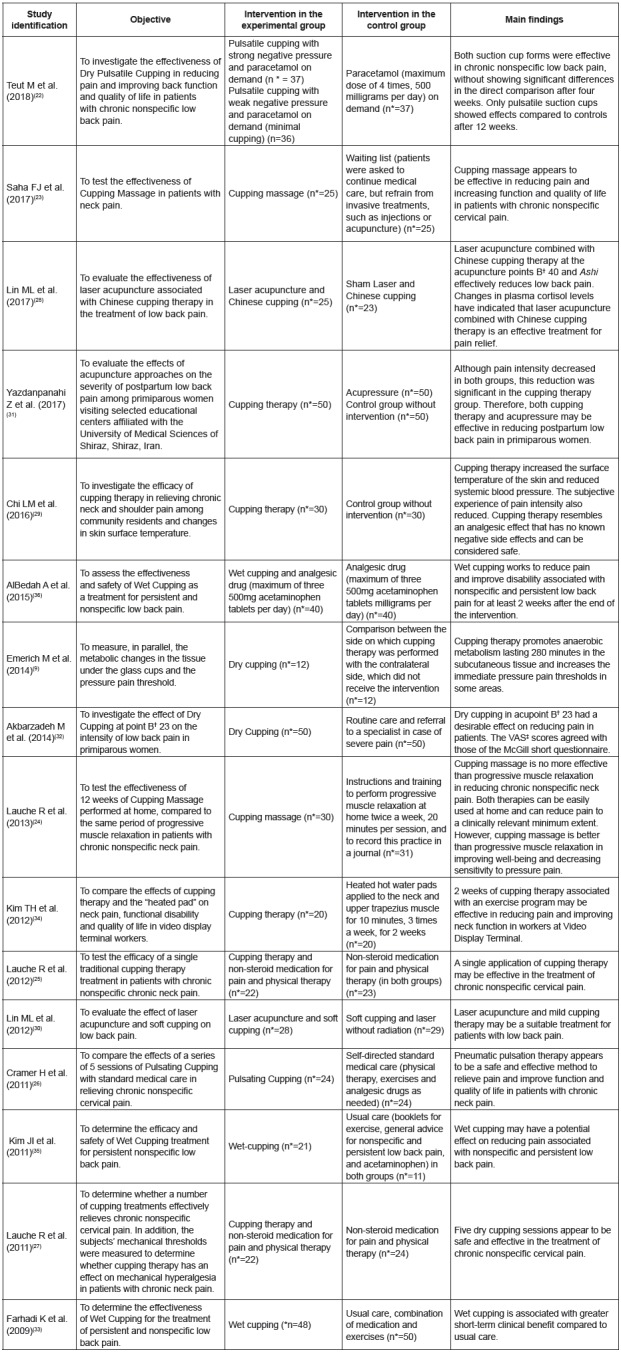

The characterization of the studies regarding the objective, the interventions applied in the experimental and control groups, and the main findings are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Characterization of the studies regarding the applied intervention, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, 2018 (n=16) .

*n - Number of participants; †B - Bladder; ‡VAS - Visual Analogue Scale.

Regarding the methodological quality of the RCTs, all reported the random sequence generation method and in only one study 9 this process was not appropriate. In another study 30 there is not enough information to infer this information. Only in four RCTs 22 , 24 , 28 - 29 ) there was a description of masking and in only two 22 , 28 this was considered appropriate. Loss of follow-up was not described in only one RCT 29 .

Therefore, 6.25% (n = 1) of the studies 9 scored one on the Jadad score; 12.5% (n = 2) 29 - 30 scored two; 62.5% (n=10) 23 , 25 - 27 , 31 - 36 scored three; 12.5% (n=2) 22 , 24 score four; and 6.25% (n=1) 28 scored five points.

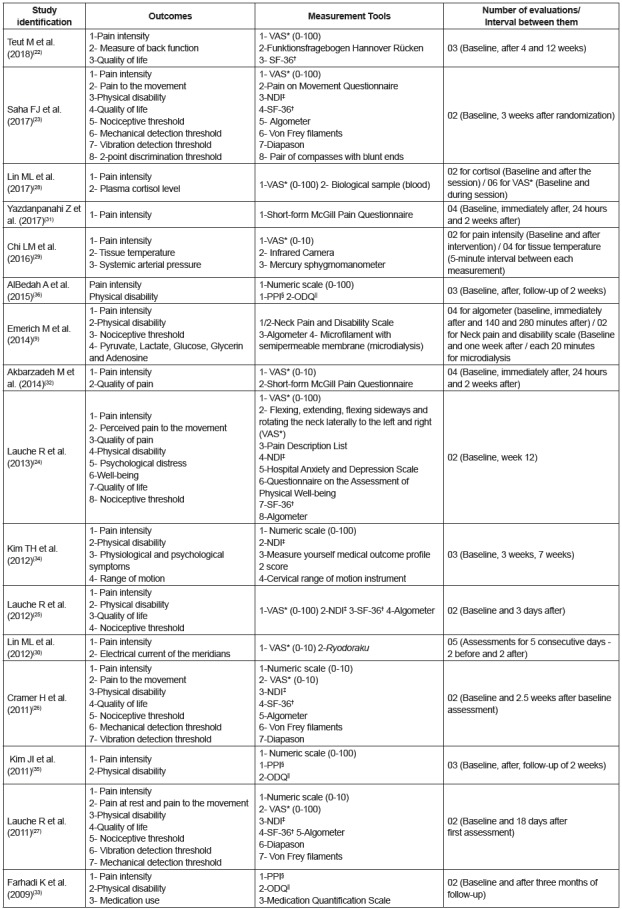

The studied outcomes, the measurement tools, the number of evaluations and the interval between them are described in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Evaluated outcomes, measurement tools, number of evaluations and interval between them. Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, 2018. (n=16).

*VAS - Visual Analogue Scale; †SF-36 - Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire; ‡NDI - Neck Disability Index; §PPI- McGill Present Pain Intensity questionnaire; ||ODQ - Oswestry Disability Questionnaire

The most evaluated outcomes were pain intensity (100%; n=16) 9 , 22 - 36 , followed by Physical disability (62.5%; n=10) 9 , 23 - 27 , 33 - 36 , quality of life (37.5%; n=6) 22 - 27 and nociceptive threshold before the mechanical stimulus, by means of an algometer (37.5%; n=6) 9 , 23 - 27 .

The number of evaluations ranged from two (baseline and after treatment) to 18. Three studies performed evaluations between sessions 9 , 28 - 29 ; and 13 studies performed follow-up evaluations after the end of the treatment, ranging from two days to three months 9 , 22 - 23 , 25 - 27 , 30 - 36 (Figure 3).

The characteristics of the intervention protocol were based on the recommendations of the Revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) 17 and in the classifications of cupping therapy 7 , 18 , which are described in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Intervention protocol. Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, 2018 (n=16).

*cm - Centimeter; †B - Bladder; ‡ml - Milliliter; §SB - Small bladder; ||GB - Gallbladder; ¶LB - Large bladder; **cc - Cubic centimeter; ††mm - Millimeter; ‡‡GV - Governing Vessel

The intervention was predominantly applied by physicians (31.25%; n=5) 22 , 25 - 28 , 34 ; followed by nurses (18.75%; n=3) 22 , 29 , 32 and pharmacists (6.25%; n=1) 32 . And 25% of the studies (n=4) 9 , 23 , 35 - 36 reported that the intervention was performed by a therapist, without specifying the training area.

Only 18,75% of the studies (n = 3) presented the time of experience of the professional who performed the intervention, from three 35 - 36 to four years 34 ; 37.5% of the studies (n=6) 9 , 22 - 25 , 27 informed only that the intervention had been performed by experienced or trained professionals, but did not mention the time of training.

Of the 16 articles selected for the systematic review, 10 entered for meta-analysis that investigated the effectiveness of cupping therapy on pain intensity. All of them approached the outcome in two comparison groups (experimental and control), in evaluations performed before and immediately after the treatment. Five studies 9 , 22 , 29 , 35 - 36 did not enter because they did not have enough data for this analysis and one study 33 performed the evaluation only three months after the end of treatment.

The results of the meta-analysis showed that cupping therapy was more effective in reducing pain compared to the control group (absolute difference between means: -1.59, [95% Confidence Interval: -2.07 to -1.10]; p = 0.001), with moderate to high heterogeneity (I2 = 67.7%, p = 0.001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plot of the pain intensity score. Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, 2018.

*CI - Confidence interval; †% - Percentage; ‡I2 - Measurement of heterogeneity

Discussion

Cupping therapy has shown positive results on chronic back pain in adults, not only in behavioral variables of pain, but also in physiological parameters in the majority of RCTs evaluated in this study, which contributes to the consolidation of its use in the treatment of this clinical condition in the study population.

Regarding methodological quality, most studies 23 , 25 - 27 , 31 - 36 ) obtained a median score (three) according to the Jadad scale 19 . This score can be justified by the lack of masking of RCTs.

It is not feasible to conceal evaluation and intervention methods in cupping therapy 22 , since the marks left by the suction cups are often visible and may persist for several days, making it difficult to perform a masking process 27 . Only one study 28 achieved masking properly; however, it was true only for volunteers who received laser therapy, an intervention used concomitantly with cupping therapy, where sham laser acupuncture was performed by applying the same procedure in one of the groups, but without energy. In a second study 24 , there is a description that the masking was applied to the evaluator of the results; however, the application of suction cups causes marks (ecchymoses, petechiae) and one of the evaluated outcomes was the pain threshold, using the algometer; for this evaluation, as the area must be naked, the marks on the skin make this kind of masking impossible. Finally, in another study 22 , the majority of participants in the minimal cupping group (84%) was able to identify the allocation after four weeks, whereas in the cupping group 55% identified the allocation.

Regarding the evaluated outcomes, pain intensity predominated, which was measured mostly by means of the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) 22 - 25 , 27 - 30 , 32 and the Numerical Scale 26 , 34 - 36 , followed by the Neck Pain and Disability Scale 9 , by the short version of the McGill Pain Questionnaire 31 , and by the Present Pain Intensity Scale 33 .

Although there are variations, the VAS usually consists of scores of 0-10 or 0-100, the extreme left being described as no pain and the extreme right as the worst possible pain; the numerical scale has a numerical rating of 0-10, 0-20 or 0-100. These scales can be classified as: painless (0), mild (1-3), moderate (4-6), and severe (7-10), and are frequently used in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain 37 . In addition, some researchers 38 - 40 have pointed to these two scales as the gold standard for assessing pain intensity, these being the instruments most used when evaluating adults, both in clinics and research.

Physical disability was the second most approached outcome, measured by means of the Neck Disability Index (NDI) 23 - 27 , 34 , of the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODQ) 33 , 35 - 36 and the Neck Pain and Disability Scale 9 . In fact, the severity and chronicity of back pain are associated with severe functional limitations 37 that imply limitations in activities of daily living 41 .

In addition, patients with chronic diseases, who require continuous treatment over a long period, present important changes in quality of life 42 , being another important outcome to be evaluated, as occurred in six studies, through the Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) 22 - 27 .

Finally, the physiological parameter most evaluated in the studies was the nociceptive threshold before the mechanical stimulus, by means of a pressure algometer 9 , 23 - 27 . It is known that individuals who have pain in the spine have higher nociceptive sensitivity compared to healthy people 43 . However, this is still considered a subjective variable, since it is the patient who determines his/her pain threshold. In fact, when the evaluation process is more related to the symptoms, such as subjective phenomena, especially pain, than to physical or laboratory results, self-assessment is considered the most reliable indicator of the existence of pain 44 . Thus, the necessary information to carry out its evaluation has its origin in the individual’s report 45 , who is the primary source of the assessment.

The systematized analysis of cupping therapy application methods showed that there is no standardization in the treatment protocol for chronic back pain. However, recent efforts have been made to standardize the cupping therapy procedure in general 46 and specifically for chronic back pain, since the most appropriate type of technique, duration of treatment, number of sessions, devices, time of application, method and suction strength and application points have not been determined.

It can be observed, however, that the most applied technique was dry cupping, specifically for the lumbar 22 , 28 , 30 - 32 and cervical regions 9 , 27 , 29 , 34 . This modality allows the stimulation of the acupoints in the same way as the acupuncture needles 47 . Researchers 18 suggest that laceration of the skin and capillaries, promoted by wet cupping, may act as another nociceptive stimulus that activates the descending inhibitory pathways of pain control 18 , thus helping to treat chronic musculoskeletal conditions 35 . However, risk for infection, vasovagal attacks and scars are the disadvantages of this method 18 . Still, compared to cupping massage, authors 47 emphasize that dry cupping has a greater analgesic effect, since the use of lubricants can reduce the friction between the edge of the cup and the skin, a fact corroborated by some authors 24 who used arnica oil for the realization of cupping massage.

Despite the variability in the application of the intervention, it was possible to identify that, on average, the cupping therapy was applied in 5 sessions, with permanence of the cups in the skin for around 8 minutes, and interval of three to four days between the applications. According to some researchers 27 , at least five sessions are required for any significant effects of cupping treatment to appear, in addition to ensuring the feasibility of the RCT. Moreover, authors 47 recommend that the cups should be left on the skin for 5 to 10 minutes or more, which culminates in the appearance of residual marks after treatment as a result of the rupture of small blood vessels that are painless and disappear between 1 and 10 days 12 . Therefore, an interval between sessions is necessary in order to allow the reestablishment of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues.

Regarding the application cups, the disposable ones are preferable a high-level sterilization or disinfection process is required prior to reuse, since the pressure exerted may cause extravasation of blood and fluids from the skin 46 . Nowadays, cupping therapy has increasingly been performed with plastic cups 47 . The size of the cups varies according to the place of application, but it is often applied in places with abundant muscles, such as the back 48 .

Regarding the suction method to create negative pressure, the use of fire predominated 9 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 32 , followed by manual pumping 23 , 34 - 36 and automatic pumping 22 , 26 , 33 . Suction with fire is the traditional method used in China, however, there is a risk of burns 18 . Manual vacuum is created when using a suction pump. This method allows microcirculation to increase more effectively if compared to fire 18 . Finally, automatic pumping is created using an electric suction pump, which allows to adjust and measure the negative pressure inside the cup, being the most suitable method for scientific research 18 .

Only three studies 22 , 26 , 28 reported the suction strength used, which should be standardized in the application protocols. The suction can be light (100 and 300 millibar/one or two manual pumpings), medium (300 and 500 milibar/three or four manual pumpings), strong (above 500 milibar/five or more manual pumpings) or pulsatile (pressure inside the cups is variable, between 100 and 200 milibar every 2 seconds) 47 , 49 . The medium suction is often indicated for painful conditions of the musculoskeletal system 18 .

There was also no standardization in relation to the application points of cupping therapy. Despite this, the application in specific acupoints in the cervical region, mainly on the bladder, gallbladder and small intestine meridians, prevailed 29 , 34 , and in the lumbar region on the bladder meridian 30 - 32 , 35 - 36 , followed by sensitive points 9 , 25 - 27 , 30 named Ashi by TCM or trigger points by Western medicine.

Meridians are passages for the flow of “qi” (vital energy) and “xue” (blood), the two basic body fluids of TCM, which spread throughout the body surface, uniting the interior with the exterior of the body and connecting the internal organs, the joints and the extremities, transforming the whole body into a single organ 50 . Part of the meridians of the bladder, small intestine and gallbladder pass through the dorsal region. The acupuncture points are located in the meridians; besides local action, they also play a systemic action and reestablish the energy balance of the body by adjusting the function of the organs, maintaining homeostasis and treating the disease 51 , so the advantage in using them.

The trigger points or Ashi are specific points of high irritability; they are sensitive to digital pressure and can trigger local and referred pain 52 . They may be deriving from dynamic overload, such as trauma or overuse, or static overload, such as postural overloads occurring during daily activities and occupational activities 53 , besides emotional tension. Addressing these points can also be a way to relieve local pain 54 .

After the application of cupping therapy, both the acupoints of the meridians of the affected regions and the trigger points or Ashi may present bruising, erythema and/or ecchymoses. According to TCM, these signs represent stagnation of “qi” and/or “xue” and may help the therapist in identifying body disorders.

Finally, the meta-analysis revealed a significant reduction of the pain intensity score in adults with chronic back pain by using cupping therapy (p = 0.001). Compared with a control group (usual care/other intervention/waiting list), this modality has advantages in relieving pain, as can be seen in Figure 5.

Only two studies 24 , 30 did not present a statistically significant difference between the groups on the benefit or harm of this intervention (Figure 5). In fact, the first study 24 pointed out that cupping therapy has the same effect as other intervention (progressive muscle relaxation) in reducing chronic nonspecific neck pain; despite this, cupping therapy was better than relaxation in improving well-being and decreasing sensitivity to pressure pain. The authors 24 justify this result, among other limitations, due to the fact that cupping therapy was performed by patients’ relatives or friends at home. The second study 30 , despite having found a positive result on the intensity of pain, did not obtain a result in the meta-analysis. It is believed that this may have been due to the fact that both groups received the intervention of soft cupping and both obtained positive results.

In the other studies 23 , 25 - 28 , 31 - 32 , 34 , the intervention reduced the probability of the outcome, being the study with the largest sample 31 the one the most contributed (15.68% weight in the meta-analysis) for this (Figure 5). In fact, all these studies reported promising results of intervention on pain intensity.

However, the results of the effectiveness of cupping therapy still need to be confirmed by subgroup analyzes, based on different types of application techniques and control groups. In addition, it is important to perform meta-regression to find the source of heterogeneity of RCTs.

In a general way, the results showed a substantial variation in the application of cupping therapy, especially in relation to the type of technique, as well as differences in the control group, which made subgroup or meta-regression unfeasible, respectively, due to the small number of studies with each of these specifications.

Conclusion

Cupping therapy is a promising method for the treatment and control of chronic back pain in adults, since it significantly decreases pain intensity scores when compared to control groups. However, the high heterogeneity and the median methodological quality of RCTs has limited the findings.

Despite this, a protocol can be established for this clinical condition: application of dry cupping technique in 5 sessions, with permanence of the disposable or plastic cups on the skin for about 8 minutes, preferably automatic or manual pumping, with medium suction strength, and three to seven days interval between applications. It is better to opt for acupoints of the dorsal region, especially those from the bladder meridian in the lumbar region, and for the meridians of the bladder, gallbladder and small intestine in the cervical and thoracic regions, as well as Ashi or trigger points. This protocol needs to be validated in future studies. And the main outcomes evaluated for this clinical condition were pain intensity, physical disability, quality of life and nociceptive threshold before the mechanical stimulus (pressure).

Referências

- 1.Sielski R, Rief W, Glombiewski JA. Efficacy of Biofeedback in Chronic back Pain: a Meta-Analysis. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24(1):25–41. doi: 10.1007/s12529-016-9572-9. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs12529-016-9572-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos T, Barber RN, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4561509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergström G, Hagberg J, Busch H, Jensen I, Björklund C. Prediction of sickness absenteeism, disability pension and sickness presenteeism among employees with back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(2):278–286. doi: 10.1007/s10926-013-9454-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4000420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gore M, Sadosky A, Stacey BR, Tai KS, Leslie D. The burden of chronic low back pain: clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and health care costs in usual care settings. Spine. 2012;37(11):E668–E677. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318241e5de. https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=22146287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sita Ananth M. 2010 Complementary Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals - Summary of Results. Alexandria, VA: Samueli Institute; 2011. https://allegralearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/CAM-Survey-FINAL-2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YT, Qi Y, Tang FY, Li FM, Li QH, Xu CP, et al. The effect of cupping therapy for low back pain: A meta-analysis based on existing randomized controlled trials. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2017;30(6):1187–1195. doi: 10.3233/BMR-169736. https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-back-and-musculoskeletal-rehabilitation/bmr169736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aboushanab TS, AlSanad S. Cupping Therapy: An Overview From A Modern Medicine Perspective. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2018;S2005-2901(17):30204–30202. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2018.02.001. https://www.jams-kpi.com/article/S2005-2901(17)30204-2/pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao H, Li X, Yan X, Wang NS, Bensoussan A, Liu J. Cupping therapy for acute and chronic pain management: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Tradit Chin Med. 2014;1(1):49–61. https://ac.els-cdn.com/S2095754814000040/1-s2.0-S2095754814000040-main.pdf?_tid=c1e983c6-64eb-465c-9208-08657cacb479&acdnat=1526231974_f88ac1fbce7d2ac75da5b3f28000df71 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emerich M, Braeunig M, Clement HW, Lüdtke R, Huber R. Mode of action of cupping--local metabolism and pain thresholds in neck pain patients and healthy subjects. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(1):148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.013. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0965229913002112?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kheirandish H, Shojaeeefar E, Meysamie A. Role of Cupping in the treatment of different diseases:systematic review article. Tehran Univ Med J. 2017;74(12):829–842. http://tumj.tums.ac.ir/article-1-7880-en.html [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rozenfeld E, Kalichman L. New is the well-forgotten old: The use of dry cupping in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2016;20(1):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.11.009. https://www.bodyworkmovementtherapies.com/article/S1360-8592(15)00279-X/pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markowski A, Sanford S, Pikowski J, Fauvell D, Cimino D, Caplan S. A Pilot Study Analyzing the Effects of Chinese Cupping as an Adjunct Treatment for Patients with Subacute Low Back Pain on Relieving Pain, Improving Range of Motion, and Improving Function. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(2):113–117. doi: 10.1089/acm.2012.0769. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/acm.2014.5302.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2707599/pdf/pmed.1000097.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. 2nd . 2002. 238p. https://www.iasp-pain.org/files/Content/ContentFolders/Publications2/FreeBooks/Classification-of-Chronic-Pain.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moura CC, Carvalo CC, Silva AM, Iunes DH, Carvalho EC, Chaves ECL. Effect of auriculotherapy on anxiety. Rev Cuba Enferm. 2014;30(2):1–15. http://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/revcubenf/cnf-2014/cnf142e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, Youping L, Taixiang W, White A, et al. Revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): Extending the CONSORT Statement. PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000261. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2882429/pdf/pmed.1000261.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Bedah AM, Aboushanab TS, Alqaed MS, Qureshi NA, Suhaibani I, Ibrahim G, et al. Classification of Cupping Therapy: A Tool for Modernization and Standardization. JOCAMR. 2016;1(1):1–10. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306240082_Classification_of_Cupping_Therapy_A_Tool_for_Modernization_and_Standardization [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the Quality of Reports of Randomized Clinical Trials: Is Blinding Necessary. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0197245695001344?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(9):820–826. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. http://annals.org/aim/article-abstract/710939/quantitative-synthesis-systematic-reviews?volume=127&issue=9&page=820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statist. Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d76b/de423b71f1cb900b988311bd2d71b700d506.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teut M, Ullmann A, Ortiz M, Rotter G, Binting S, Cree M, et al. Pulsatile dry cupping in chronic low back pain - a randomized three-armed controlled clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):115–115. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2187-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5879872/pdf/12906_2018_Article_2187.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saha FJ, Schumann S, Cramer H, Hohmann C, Choi KE, Rolke R, et al. The Effects of Cupping Massage in Patients with Chronic Neck Pain - A Randomised Controlled Trial. Complement Med Res. 2017;24(1):26–32. doi: 10.1159/000454872. https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/454872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauche R, Materdey S, Cramer H, Haller H, Stange R, Dobos G, et al. Effectiveness of home- based cupping massage compared to progressive muscle relaxation in patients with chronic neck pain - a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065378. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3676414/pdf/pone.0065378.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lauche R, Cramer H, Hohmann C, Choi KE, Rampp T, Saha FJ, et al. The effect of traditional cupping on pain and mechanical thresholds in patients with chronic nonspecific neck pain: a randomised controlled pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2012/429718. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3235710/pdf/ECAM2012-429718.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cramer H, Lauche R, Hohmann C, Choi KE, Rampp T, Musial F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of pulsating cupping (pneumatic pulsation therapy) for chronic neck pain. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18(6):327–334. doi: 10.1159/000335294. https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/335294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauche R, Cramer H, Choi KE, Rampp T, Saha FJ, Dobos GJ, et al. The influence of a series of five dry cupping treatments on pain and mechanical thresholds in patients with chronic non-specific neck pain-a randomised controlled pilot study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;18(6):327–334. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3224248/pdf/1472-6882-11-63.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin ML, Wu JH, Lin CW, Su CT, Wu HC, Shih YS, et al. Clinical Effects of Laser Acupuncture plus Chinese Cupping on the Pain and Plasma Cortisol Levels in Patients with Chronic Nonspecific Lower Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2017/3140403. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2017/3140403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chi LM, Lin LM, Chen CL, Wang SF, Lai HL, Peng TC. The Effectiveness of Cupping Therapy on Relieving Chronic Neck and Shoulder Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2016/7358918. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2016/7358918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin ML, Wu HC, Hsieh YH, Su CT, Shih YS, Lin CW, et al. Evaluation of the effect of laser acupuncture and cupping with ryodoraku and visual analog scaleon low back pain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/521612. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482015/pdf/ECAM2012-521612.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yazdanpanahi Z, Ghaemmaghami M, Akbarzadeh M, Zare N, Azisi A. Comparison of the Effects of Dry Cupping and Acupressure at Acupuncture Point (BL23) on the Women with Postpartum Low Back Pain (PLBP) Based on Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaires in Iran: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Fam Reprod Health. 2017;11(2):82–89. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5742668/pdf/JFRH-11-82.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akbarzadeh M, Ghaemmaghami M, Yazdanpanahi Z, Zare N, Azizi A, Mohagheghzadeh A. The Effect Dry Cupping Therapy at Acupoint BL23 on the Intensity of Postpartum Low Back Painin Primiparous Women Based on Two Types of Questionnaires, 2012; A Randomized ClinicalTrial. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2014;2(2):112–120. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4201191/pdf/ijcbnm-2-112.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farhadi K, Schwebel DC, Saeb M, Choubsaz M, Mohammadi R, Ahmadi A. The effectiveness of wet-cupping for nonspecific low back pain in Iran: a randomized controlledtrial. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2008.05.003. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0965229908000630?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim TH, Kang JW, Kim KH, Lee MH, Kim JE, Kim JH, et al. Cupping for treating neck pain in video display terminal (VDT) users: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Occup Health. 2012;54(6):416–426. doi: 10.1539/joh.12-0133-oa. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/joh/54/6/54_12-0133-OA/_pdf/-char/en [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JI, Kim TH, Lee MS, Kang JW, Kim KH, Choi JY, et al. Evaluation of wet-cupping therapy for persistent non-specific low back pain: a randomised, waiting-list controlled, open-label, parallel-group pilot trial. Trials. 2011;12:146–146. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-146. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3141528/pdf/1745-6215-12-146.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.AlBedah A, Khalil M, Elolemy A, Hussein AA, AlQaed M, Al Mudaiheem A, et al. The Use of Wet Cupping for Persistent Nonspecific Low Back Pain: Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21(8):504–508. doi: 10.1089/acm.2015.0065. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4522952/pdf/acm.2015.0065.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salaffi F, Ciapetti A, Carotti M. Pain assessment strategies in patients with musculoskeletal conditions. Reumatismo. 2012;64(4):216–229. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2012.216. http://reumatismo.org/index.php/reuma/article/view/reumatismo.2012.216/pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puntillo K, Neighbor M, Nixon R. Accuracy of emergency nurses in assessment of patients pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2003;4(4):171–175. doi: 10.1016/s1524-9042(03)00033-x. http://allnurses.com/pain-management-nursing/accuracy-of-emergency-59028.html [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. http://www.immpact.org/static/publications/Dworkin%20et%20al.,%202005.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(1):17–24. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen103. https://bjanaesthesia.org/article/S0007-0912(17)34263-0/pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cunha LL, Mayrink WC. Influence of chronic pain in the quality of life of the elderly. Rev Dor. 2011;12(2):120–124. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rdor/v12n2/v12n2a08.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 42.Castro MMC, Daltro C, Kraychete DC, Lopes J. The cognitive behavioral therapy causes an improvement in quality of life in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arq Neuro-psiquiatr. 2012;70(11):864–868. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2012001100008. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/anp/v70n11/a08v70n11.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farasyn A, Lassat B. Cross friction algometry (CFA): Comparison of pressure pain thresholds between patients with chronic non-specific low back pain and healthy subjects. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2016;20(2):224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.09.005. https://www.bodyworkmovementtherapies.com/article/S1360-8592(15)00259-4/pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Institutes of Health The Integrated Approach to the Management of Pain; Consensus Development Conference Statement; 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sousa FAEF, Pereira LV, Cardoso R, Hortense P. Multidimensional pain evaluation scale. (EMADOR). Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2010;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692010000100002. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v18n1/pt_02.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nielsen A, Kligler B, Koll BS. Safety protocols for gua sha (press-stroking) and baguan (cupping) Complement Ther Med. 2012;20(5):340–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2012.05.004. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0965229912000829?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tham LM, Lee HP, Lu C. Cupping: From a biomechanical perspective. J Biomech. 2006;39(12):2183–2193. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.06.027. https://www.jbiomech.com/article/S0021-9290(05)00322-2/pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoo S.S., Tausk F. Cupping: east meets west. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(9):664–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02224.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teut M, Kaiser S, Ortiz M, Roll S, Binting S, Willich SN, et al. Pulsatile dry cupping in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee - a randomized controlled exploratory trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12(184):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-184. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3527288/pdf/1472-6882-12-184.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang GJ, Ayati MH, Zhang WB. Meridian studies in China: a systematic review. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2010;3(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/S2005-2901(10)60001-5. https://www.jams-kpi.com/article/S2005-2901(10)60001-5/pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li F, He T, Xu Q, Lin LT, Li H, Liu Y, et al. What is the Acupoint? A preliminary review of Acupoints. Pain Med. 2015;16(10):1905–1915. doi: 10.1111/pme.12761. https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article/16/10/1905/2460295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.International Association for the Study of Pain . Global year against musculoskeletal pain. Myofascial Pain; 2010. http://www.iasp-pain.org/files/Content/ContentFolders/GlobalYearAgainstPain2/MusculoskeletalPainFactSheets/MyofascialPain_Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dommerholt J. Dry needling - peripheral and central considerations. Pain Med. 2015;16(10):1905–1915. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3201653/pdf/jmt-19-04-223.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao H. Clinical observation on therapeutic effect of cupping combined with acupuncture stimulation at trigger points for lumbar myofascial pain syndrome. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2014;39(4):324–328. https://web.b.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=10471979&AN=123067289&h=KVyuzUBFiXE6HntiPqHImXntz1iicxcKNwGrlQq0AMeIF2V6vP7ve956sIg8M0zmRdGAVvtrgKrGNtqZ4USF4g%3d%3d&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLocal=ErrCrlNotAuth&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d10471979%26AN%3d123067289 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]