Abstract

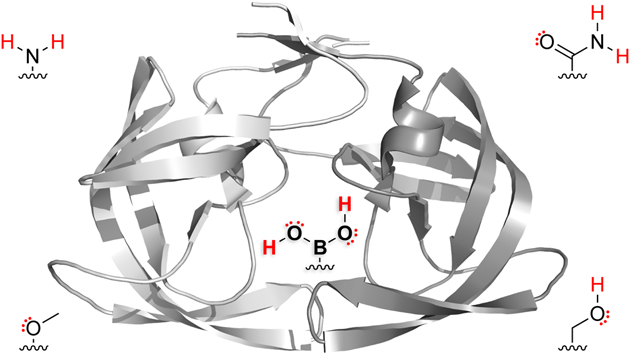

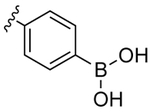

Boronic acids have been typecast as moieties for covalent complexation and are employed only rarely as agents for noncovalent recognition. By exploiting the profuse ability of a boronic acid group to form hydrogen bonds, we have developed an inhibitor of HIV-1 protease with extraordinary affinity. Specifically, we find that replacing an aniline moiety in darunavir with a phenylboronic acid leads to 20-fold greater affinity for the protease. X-Ray crystallography demonstrates that the boronic acid group participates in three hydrogen bonds, exceeding that of the amino group of darunavir or any other analog. Importantly, the boronic acid maintains its hydrogen bonds and its affinity for the drug-resistant D30N variant of HIV-1 protease. The BOH⋯OC hydrogen bonds between the boronic acid hydroxy group and Asp30 (or Asn30) of the protease are short (rO⋯O = 2.2 Å), and density functional theory analysis reveals a high degree of covalency. These data highlight the utility of boronic acids as versatile functional groups in the design of small-molecule ligands.

Graphical Abstract

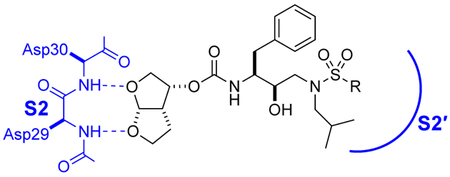

Clinical inhibitors of HIV-1 protease are quintessential triumphs of structure-based drug design.1 The protease cleaves diverse sequences that connect individual domains of viral polyproteins, recognizing four substrate residues on each side of the scissile bond.2 The components of most effective inhibitors—a tetrahedral-intermediate mimetic flanked by subsite-targeting groups—have undergone iterative optimization for 30 years.3 The discovery of the bis-THF moiety of darunavir, which targets the enzymic S2 subsite, was a major breakthrough.4 Its two bis-THF oxygen atoms accept hydrogen bonds from the main-chain amides of Asp29 and Asp30, leading to low picomolar affinity (Table 1).5 Mutations that overcome such main-chain interactions are rare,6 and darunavir is among the most resilient of protease inhibitors.7

Table 1.

Values of Ki for Inhibition of HIV-1 Protease

| R | Ki (pM) | Relative Affinitya | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

darunavir |

10 ± 1 | — | 9 | |

|

14 | 1.0 | 1b | |

|

12 | 1.2 | 1b | |

|

12.7 | 1.3 | 10 | |

|

10 | 1.6 | 11 | |

|

8.9 | 1.8 | 10 | |

1 |

0.5 ± 0.3 | 20 | This work |

Values of Ki can depend on assay conditions. Here, values are compared by using darunavir as a benchmark with Relative Affinity = Ki,darunavir /Ki,analog as reported in the indicated reference.

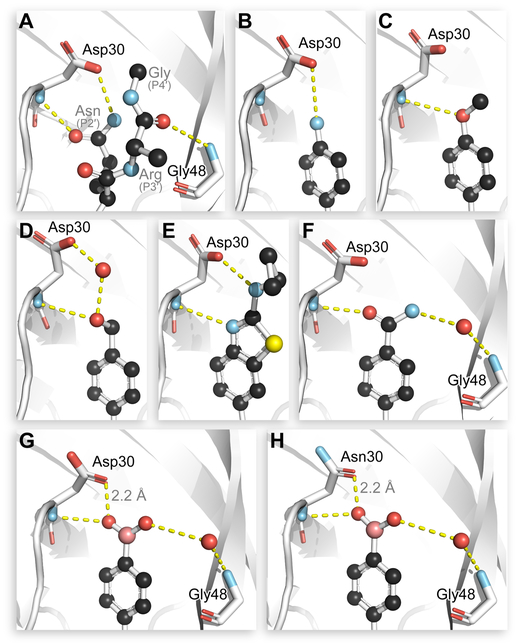

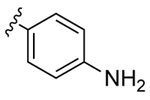

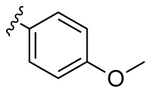

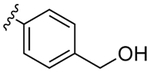

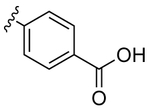

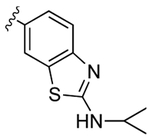

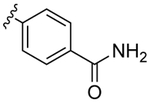

Despite countless attempts at optimization, an ideal functional group for the S2′ subsite has been elusive. Inspection of structures of complexes between substrates and darunavir analogs (Table 1, Figure 1) in conjunction with biochemical characterization revealed opportunities to us. Half of endogenous substrates occupy the S2′ subsite with a glutamine or glutamic acid residue.8,2 These side-chains have been observed to form hydrogen bonds with both the main-chain N-H and the side-chain carboxylate group of Asp30 (Figure 1A). The aniline nitrogen of darunavir and the methoxy group of an anisole analog form only a single hydrogen bond (Figures 1B and 1C). Benzyl alcohol and cyclopropyl-amino-benzothiazole groups can form two hydrogen bonds with Asp30, one with the main-chain N–H and another with the side-chain (either via a water-bridge or directly), but provide <2-fold increases in affinity (Table 1, Figures 1D and 1E). Other aryl sulfonamide substituents, including benzoic acid and benzamide, form a water-bridge with Gly48 in addition to accepting a hydrogen bond from the main chain of Asp30, but again exhibit a <2-fold increase in affinity (Table 1, Figure 1F). This water-bridge with Gly48 is another interaction that can be exploited to recognize the main chain. Yet, no extant protease inhibitor interacts with all three of these targets: main chain and side chain of Asp30, and a water molecule that bridges to the main chain of Gly48.

Figure 1.

Interactions with a substrate, darunavir, or its analogs and the S2′ subsite of HIV-1 protease. (A) A substrate (PDB entry 1kj7). (B) Darunavir (4hla). (C) Anisole analog (2i4u). (D) Benzyl alcohol analog (3o9g). (E) Cyclopropyl-amino-benzothiazole analog (5tyr). (F) Benzamide analog (4i8z). (G) Boronic acid 1 bound to wild-type HIV-1 protease (6c8x). (H) Boronic acid 1 bound to D30N HIV-1 protease (6c8y). Major conformers are shown for inhibitors that bound in non-symmetry–related conformations.

We reasoned that an optimal functional group for targeting the S2′ subsite would serve as both a donor and an acceptor of hydrogen bonds. We were aware that the two hydroxy groups presented by boronic acids are versatile in this manner.12 These hydroxy groups display four lone pairs and two hydrogen-bond donors. No other functional group provides six opportunities to form hydrogen bonds so economically. We anticipated that one hydroxy group of a boronic acid could form both interactions with Asp30 while allowing the other hydroxy group to form a water-bridge with Gly48. Accordingly, we synthesized boronic acid 1, in which the 4-sulfonylaniline moiety of darunavir is replaced with a 4-sulfonylphenylboronic acid (Table 1, Scheme S1).

Boronic acid 1 is a competitive inhibitor of catalysis by HIV-1 protease. By using a hypersensitive assay of catalytic activity,9 we found its inhibition constant (Ki) to be 0.5 ± 0.3 pM, which is indicative of 20-fold greater affinity compared to darunavir itself (Table 1, Figure S1D). Because the boronic acid moiety of 1 is anticipated to interact with Asp30, we suspected that D30N HIV-1 protease, which is a common variant that endows resistance, could compromise the affinity of boronic acid 1. For example, the D30N substitution entices darunavir to form a water-bridge between its aniline nitrogen and the nascent asparagine, diminishing affinity by 30-fold.13 Remarkably, the affinity of boronic acid 1 for the D30N variant (Ki = 0.4 ± 0.3 pM) is indistinguishable from that for wild-type HIV-1 protease.

To understand the basis for the extraordinary affinity and resiliency of boronic acid 1, we determined the X-ray crystal structures of its complexes with both wild-type HIV-1 protease and the D30N variant. The two structures were solved at resolutions of 1.60 Å (Rfree = 0.1967) and 1.94 Å (Rfree = 0.2203), respectively (Table S1, Figure S2). True to its design, the boronic acid participated in all three hydrogen-bonding interactions (Figures 1G and 1H). Of special note are BOH⋯OC hydrogen bonds observed in both structures (Figures 1G and 1H). The interatomic distance of 2.2 Å between the boronate oxygen and side-chain Oδ of residue 30 is reminiscent of a low-barrier hydrogen bond (LBHB).14

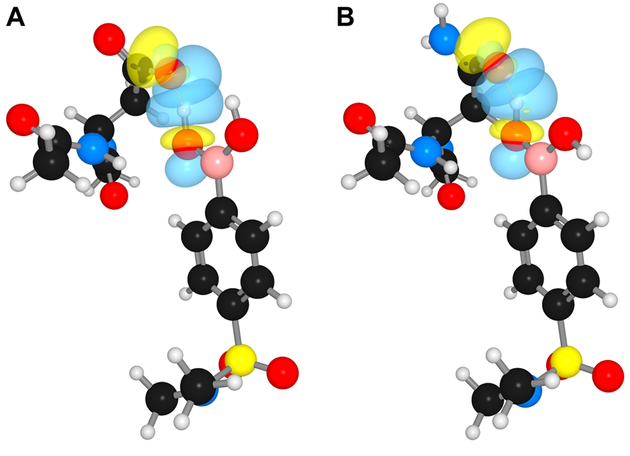

We analyzed the atypically short hydrogen bonds between boronic acid 1 and HIV-1 protease with computational methods. First, we optimized the hydrogen atoms by applying density functional theory (DFT) to a simple model extracted from the crystal structure. We examined the electronic structure by using Natural Bonding Orbital (NBO) analysis.15 NBO analysis revealed an interaction energy of 69.8 kcal/mol between boronic acid 1 and the wild-type protease. The typically non-hybridized p-type lone pair of the carboxylate oxygen hybridizes to sp3.99 in the hydrogen-bonded complex. This large interaction energy and hybridization suggest a large degree of covalency in the BOH⋯OC hydrogen bond. Next, we assessed the covalency of the short hydrogen bond between boronic acid 1 and the wild-type protease with quantum theory of atoms in molecules (AIM).16 AIM calculations—specifically, structural elements at the bond critical point (BCP)—enable quantification of the covalency between neighboring atoms. At the BOH⋯OC BCP, we calculated an electron density (ρ) of 0.174 eÅ–3, a Laplacian (∇2ρ) of –0.08 eÅ–5, and a bond index of 0.22. Typical OH⋯OC hydrogen bonds display ρ < 0.2 eÅ–3, positive Δ2ρ values, and a bond index <0.1.17 Instead, the attributes of BOH⋯OC are consistent with the attributes of an LBHB.14

An LBHB arises from functional groups with closely matched pKa values.14 This requirement can be met by a carboxylic acid and a boronic acid,18 which are isoelectronic. In the enzyme·inhibitor complex (Figure 1G), the boronic acid group of 1 displays an no,p→pB interaction (i.e., resonance) of 89.1 kcal/mol, and the carboxylic acid group of Asp30 in HIV-1 protease displays a comparable no,p→π*C=O interaction of 87.9 kcal/mol. The ensuing hyperconjugative interaction between a boronic acid and carboxyl acid is reminiscent of a resonance-assisted hydrogen bond.19 Such hyperconjugation is absent in other inhibitors, such as the benzyl alcohol analog of darunavir (Figure 1D).

Boronic acids possess attractive properties beyond their versatile hydrogen bonding. Boronic acid 1, like darunavir, is not toxic to human cells at concentrations up to 1 mM (Figure S3). In vivo, aniline moieties can exhibit problematic genotoxicity as a result of metabolic activation.20 In contrast, the major metabolite of boronic acids is the oxidative deboronation product, an alcohol, which is modified further in phase II metabolism for efficient excretion.21,22

We conclude that a boronic acid group in a ligand can be profuse and versatile in forming hydrogen bonds with a protein. These attributes are especially valuable in the design of ligands for proteins that are under the selective pressure of drug resistance. In those instances, the ability of boronic acids to form multiple hydrogen bonds enhances affinity, and the admixture of hydrogen-bond acceptors and donors enables adaption to mutations.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Orbital interactions in a model of boronic acid 1 and residue 30 of HIV-1 protease derived from X-ray crystal structures (PDB entries 6c8x and 6c8y). NBO rendering of the hydrogen bond between a boronic acid hydroxy group and Oδ of Asp30 (A) and Asn30 (B) with hydrogen atoms optimized at the M06–2X/6–311+G(d,p) level of theory employing the IEFPCM solvation model.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I.W.W. was supported by Biotechnology Training Grant T32 GM008349 (NIH) and a Genentech predoctoral fellowship. M.J.P. was supported by Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology Training Grant T32 GM008688 (NIH) and American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship 09PRE2260125. B.G. was supported by an Arnold O. Beckman Postdoctoral Fellowship. This work was supported by Grants R01 GM044783 (NIH) and MCB 1518160 (NSF), and made use of NMRFAM (University of Wisconsin–Madison), which is supported by Grant P41 GM103399 (NIH). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02–06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.xxxxxxx.

Experimental protocols and analytical data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Vondrasek J; Wlodawer A Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 1998, 27, 249–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh AK, Ed. Aspartic Acid Proteases as Therapeutic Targets. Wiley–VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Prabu-Jeyabalan M; Nalivaika E; Schiffer CA Structure 2002, 10, 369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Ripka AS; Rich DH Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 1998, 2, 441–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ghosh AK; Kincaid JF; Cho W; Walters DE; Krishnan K; Hussain KA; Koo Y; Cho H; Rudall C; Holland L; Buthod J Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 1998, 8, 687–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Koh Y; Nakata H; Maeda K; Ogata H; Bilcer G; Devasamudram T; Kincaid JF; Boross P; Wang YF; Tie Y; Volarath P; Gaddis L; Harrison RW; Weber IT; Ghosh AK; Mitsuya H Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2003, 47, 3123–3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh AK; Dawson ZL; Mitsuya H Bioorg. Med. Chem 2007, 15, 7576–7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) King NM; Prabu-Jeyabalan M; Nalivaika EA; Schiffer CA Chem. Biol 2004, 11, 1333–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Agniswamy J; Shen CH; Aniana A; Sayer JM; Louis JM; Weber IT Biochemistry 2012, 51, 2819–2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) de Vera IM; Blackburn ME; Fanucci GE Biochemistry 2012, 51, 7813–7815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhang Y; Chang YC; Louis JM; Wang YF; Harrison RW; Weber IT ACS Chem. Biol 2014, 9, 1351–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Ghosh AK; Sridhar PR; Leshchenko S; Hussain AK; Li J; Kovalevsky AY; Walters DE; Wedekind JE; Grum-Tokars V; Das D; Koh Y; Maeda K; Gatanaga H; Weber IT; Mitsuya H J. Med. Chem 2006, 49, 5252–5261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lefebvre E; Schiffer CA AIDS Rev. 2008, 10, 131–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nalam MN; Ali A; Reddy GS; Cao H; Anjum SG; Altman MD; Yilmaz NK; Tidor B; Rana TM; Schiffer ,CA Chem. Biol 2013, 20, 1116–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Weber IT; Wu J; Adomat J; Harrison RW; Kimmel AR; Wondrak EM; Louis JM Eur. J. Biochem 1997, 249, 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Beck ZQ; Hervio L; Dawson PE; Elder JH; Madison EL Virology 2000, 274, 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Windsor IW; Raines RT Sci. Rep 2015, 5, 11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Yedidi RS; Maeda K; Fyvie WS; Steffey M; Davis DA; Palmer I; Aoki M; Kaufman JD; Stahl SJ; Garimella H; Das D; Wingfield PT; Ghosh AK; Mitsuya H Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 4920–4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ghosh AK; Rao KV; Nyalapatla PR; Osswald HL; Martyr CD; Aoki M; Hayashi H; Agniswamy J; Wang YF; Bulut H; Das D; Weber IT; Mitsuya HJ Med. Chem 2017, 60, 4267–4278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Hall DG, Ed. Boronic Acids: Preparation and Applications in Organic Synthesis, Medicine and Materials, 2nd ed Wiley–VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tzeli D; Theodorakopoulos G; Petsalakis ID; Ajami D; Rebek JJ Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 16977–16985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Diaz DB; Yudin AK Nat. Chem 2017, 9, 731–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kovalevsky AY; Tie Y; Liu F; Boross PI; Wang Y-F; Leshchenko S; Ghosh AK; Harrison RW; Weber IT J. Med. Chem 2006, 49, 1379–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Cleland WW; Frey PA; Gerlt JA J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273, 25529–25532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Perrin CL Acc. Chem. Res 2010, 43, 1550–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Weinhold FJ Comput. Chem 2012, 33, 2363–2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bader RF W. Chem. Rev 1991, 91, 893–928. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Schiott B; Iversen BB; Madsen GK; Larsen FK; Bruice TC Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 12799–12802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).The pKa of phenylboronic acid is 8.9 (Westmark PR; Gardiner SJ; Smith BD J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 11093–11100). [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Gilli G; Bellucci F; Ferretti V; Bertolasi V J. Am. Chem. Soc 1989, 111, 1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Góra RW; Maj M; Grabowski SJ Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2013, 15, 2514–2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Grosch AA; van der Lubbe SCC; Fonseca GC J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 1813–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Gentile JM; Gentile GJ; Plewa MJ Mutat. Res 1987, 188, 185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bomhard EM; Herbold BA Crit. Rev. Toxicol 2005, 35, 783–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Makhdoumi P; Limoee M; Ashraf GM; Hossini H Curr. Neuropharmacol 2018, DOI : 10.2174/1570159X16666180803164238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Pekol T; Daniels JS; Labutti J; Parsons I; Nix D; Baronas E; Hsieh F; Gan LS; Miwa G Drug Metab. Dispos 2005, 33, 771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bu W; Akama T; Chanda S; Sullivan D; Ciaravino V; Jarnagin K; Freund Y; Sanders V; Chen C-W; Fan X; Heyman I; Liu LJ Pharm. Biomed. Anal 2012, 70, 344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Notably, a growing number of boronic acids are achieving clinical utility.Raedler LA Am. Health Drug Benefits 2016, 9, 102–105.Kailas A Dermatol. Ther 2017, 30, e12533.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.