Abstract

Background:

Published approaches to the evaluation and management of patients with rapidly progressive dementia (RPD) have been largely informed by experience at academic hospitals and national centers specializing in the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Whether these approaches can be applied to patients assessed within lower-acuity outpatient settings is unknown.

Methods:

Ninety-six patients with suspected RPD were assessed within the Washington University School of Medicine (Saint Louis, Missouri, USA) outpatient memory clinic from February 2006 to February 2016. Consensus etiologic diagnoses were established following independent review of clinical data by two dementia specialists.

Results:

Sixty-seven (67/90, 70%) patients manifested with faster-than-expected cognitive decline leading to dementia within 2 years of symptom onset. Female sex (42/67, 63%), median patient age (68.3 years; range, 45.4-89.6) and years of education (12 years; range, 6-14) were consistent with clinic demographics. Atypical presentations of common neurodegenerative dementing illnesses accounted for 90% (60/67) of RPD cases. Older age predicted a higher odds of amnestic Alzheimer disease dementia (OR 2.1 per decade; 95%CI, 1.1-3.8, p=0.02). Parkinsonism (OR 6.9; 95%CI, 1.6-30.5, p=0.01) or cortical visual dysfunction (10.8; 95%CI, 1.7-69.4, p=0.01) predicted higher odds of another neurodegenerative cause of RPD, including sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Conclusions and Relevance:

The clinical environment influences the prevalence of RPD causes. The clinical evaluation should be adapted to promote detection of common causes of RPD, specific to the practice setting.

Keywords: rapidly progressive dementia, neurodegenerative disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, outpatient, memory clinic

Introduction

Published approaches to the evaluation and management of patients with rapidly progressive dementia (RPD)1–7 have been largely informed by experience at academic hospitals and national centers specializing in the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).1–5,8,9 These approaches prioritize testing using measures of varying sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of CJD, including magnetic resonance (MR) imaging,10 electroencephalogram (EEG),11 and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers (i.e., total-tau, 14-3-3 and real-time quaking-induced conversion [RT-QuIC]12–14). The prevalence of specific causes of RPD in a given practice environment are expected to vary with center- (e.g., level of care provided, academic affiliation, referral base3,7), practitioner- (e.g., sub-specialization, clinic wait times15), and patient-specific factors (e.g., age, risk factors and exposures16,17). Accordingly, it remains unclear whether existing approaches are applicable to the diagnosis of RPD in patients assessed in lower-acuity outpatient settings, where the majority of neurological care is delivered.

To address this issue, we evaluated the causes of RPD in patients evaluated over a 10-year period within a tertiary-care outpatient memory clinic. Like many outpatient memory clinics, our Memory Diagnostic Center (MDC) is comprised primarily of older community-dwelling patients, in whom neurodegenerative dementing illnesses (NDI) are increasingly prevalent.18 Acknowledging this, we hypothesized that atypical presentations of common NDI would account for the majority of cases of RPD encountered in our clinic. We also considered the clinical factors and tests that were most useful in establishing a primary diagnosis, in the interest of optimizing the evaluation of patients with RPD in the outpatient setting.

Methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Beginning February 2006, patients with suspected RPD were identified by MDC clinicians, and clinic identifiers maintained on an internal database to ensure that autopsies (if requested) were performed using appropriate protocols for patients with potentially transmissible diseases (namely prion disease). Medical records from all patients on the “RPD List” were retrospectively reviewed. The Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee approved the study protocols, and issued a waiver of consent.

Patients

Patients presented to the MDC for the evaluation and management of cognitive complaints from February 2006 and February 2016. Patients attended a median of two assessments (range, 1-11), completed over a median of 5.5 (max 85.1) months. Evaluations included a semi-structured interview with a knowledgeable collateral source, and detailed neurological examination. Standard tests of global cognitive function (including the Mini-Mental State Examination19), episodic memory, executive functioning, visuospatial ability, language and semantic memory were administered by experienced psychometrists at each visit. At the conclusion of each visit, the treating neurologist determined the most likely etiological diagnosis, and recorded the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). The CDR is a widely used measure of dementia severity that reflects performance across six cognitive and functional domains.20 Summation of scores across domains yields the CDR sum-of-boxes (CDR-SB). Change in CDR-SB was used to quantify dementia progression.21

Ninety-six patients with suspected RPD were identified. Of these, 67/96 (70%) met a priori defined criteria for the diagnosis of RPD, and comprised the study population. RPD was diagnosed when dementia developed within 2 years of the onset of the first symptom, or when symptoms progressed at a greater-than-expected rate for a known dementing illness (defined as an increase of more than two global CDR stages in ≤2 years). Although there is no universally accepted definition of RPD, these criteria were selected as they closely reflected physician practices at our outpatient MDC, and at other well-established tertiary care centers specializing in the assessment of RPD patients.1,7

Etiologic diagnoses and evaluation

The etiologic dementia diagnosis provided by the treating clinician was verified by neuropathological (n=4) or genetic (n=1) analyses in 5/67 (7%) cases. In the remaining cases, the medical records were reviewed by a second dementia specialist (blinded to the original clinician’s assessment), and a consensus clinical diagnosis was established. Disagreements concerning primary diagnoses were resolved via blinded-review by a third dementia specialist. Etiologic diagnoses were assigned in accordance with published diagnostic criteria (amnestic Alzheimer disease [AD],22 dementia with Lewy bodies,23 behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia,24 primary progressive aphasia [PPA],25 corticobasal syndrome,26 progressive supranuclear palsy,27 posterior cortical atrophy [PCA],28 vascular cognitive impairment,29 and CJD30). Secondary (potentially modifying) diagnoses were documented when present (e.g., active psychiatric symptoms, cerebrovascular disease, sleep disorder and medication-induced cognitive impairment).

The frequency with which “core tests”, recommended in the evaluation of RPD patients, were completed was systematically evaluated (i.e., screening serum studies, neuroimaging, CSF analysis and electroencephalogram [EEG]2,6,7). Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) or vitamin B12 levels beyond the expected range (expected TSH = 0.3-4.20 microliters/ml; expected vitamin B12 ≥230 picograms/ml) were labeled abnormal. Structural neuroimaging was deemed abnormal when any of the following findings were present: greater than mild generalized atrophy, prominent asymmetric / regional atrophy, severe deep white matter T2 hyperintensities (MR imaging; corresponding to a Fazekas score of ≥231) or confluent periventricular hypodensities (CT), hemorrhage (macroscopic, or microscopic hemorrhage identified on susceptibility-weighted MR imaging), acute infarction, or edema. Chronic infarcts were not counted as abnormalities. Abnormal EEG findings included diffuse slowing (<8Hz), focal epileptiform discharges, or periodic complexes. Cerebrospinal abnormalities included nucleated cell count >5 cells/mm3 (tube 4, corrected for red blood cells when appropriate) or elevated protein >45 mg/dl. The incidence of disease-specific testing was also considered, including AD- (e.g., amyloid-β42, total-tau and phosphorylated tau; commercial testing via Athena Diagnostics; Marlborough, Massachusetts) and CJD-specific CSF biomarkers (e.g., total-tau, 14-3-3, RT-QuIC; testing via the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center, Case Western Reserve University; Cleveland, Ohio), and autoantibody testing in serum and CSF (commercial testing via the Mayo Clinic; Rochester, Minnesota).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp., Version 24.0. Armonk, NY). Group-wise comparisons for continuous variables were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test; the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for post-hoc comparisons. Group-wise differences for categorical variables were determined using the Fisher’s exact test. Potential associations between demographic features, clinical variables and clinical diagnoses were explored using logistic regression, with diagnosis of amnestic AD dementia (versus other NDI, including CJD) included as the dependent variable. Age at first diagnosis and sex were included as covariates in the model (forced entry), with covariates of potential interest (years of education; reported history of memory loss, behavioral change, visuospatial or language dysfunction, sleep dysfunction, or weight loss; neurological examination findings indicative of aphasia, cortical visual impairment, cortical sensory or motor impairment, parkinsonism, ataxia, or other gait change) entered via forward step-wise regression (alpha of 0.05 was used for entry, and 0.1 for removal). Model explanatory power and fit were assessed using the c-statistic and Hosmer-Lemeshow lack-of-fit test. Annualized rates of progression were compared across disease categories (amnestic AD dementia, other NDI, prion disease, non-NDI) using an analysis of variance (ANCOVA), controlling for age-at-symptomatic onset. Group-wise differences in the median duration of illness were depicted via Kaplan-Meier curves, with differences assessed using the Mantel-Cox (log-rank) test. Statistical significance was established at p<0.05 (Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons when appropriate).

Results

The median age-at-symptomatic onset of patients with suspected RPD was 68.3 years (range, 45.4-89.6). Patients had a median of 12 years (range, 6-14) of formal education. Sixty-three percent of patients were female (42/67). Sixty-two (93%) patients were Non-Hispanic White; five (7%) were African American. The causes of RPD were established by clinical consensus for the 93% (62/67) of cases without neuropathological or genetic confirmation. Inter-rater agreement was high (Cohen’s Kappa=0.77), with primary and secondary reviewers arriving at the same diagnosis in 56/62 (90%) cases. Primary NDI accounted for 60/67 (90%) cases; amnestic AD dementia was the most common clinical diagnosis (Table 1). Other NDI were the second most commonly diagnosed group, including patients with non-amnestic (atypical) dementia syndromes that are commonly (although not always) attributed to AD neuropathology (e.g., PCA, logopenic variant PPA). CJD accounted for 6% (4/67) of RPD cases.

Table 1:

Causes of RPD in the outpatient Memory Diagnostic Center.

| Clinical Diagnoses | Number (%); n=67 |

|---|---|

| Amnestic AD dementia | 34 (51) |

| Other NDI | 26 (39) |

| PCA | 8 (12) |

| DLB | 8 (12) |

| FTD | 6 (9) |

| Other | 4 (6) |

| Prion disease (CJD) | 4 (6) |

| Other | 3 (4) |

RPD=rapidly progressive dementia; AD=Alzheimer disease; NDI=neurodegenerative dementing illness; PCA=posterior cortical atrophy; DLB=dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD=frontotemporal dementia; CJD=Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Demographic features, presenting complaints and neurological examination findings are reported at the time of RPD designation (Table 2), stratified by clinical diagnosis. No between group differences were noted in age-at-symptomatic onset (χ2=3.2, df=3, p=0.4), years of education (χ2=1.9, df=3, p=0.6) or gender (Fisher’s exact test, two-sided; p=0.1). Given the limited number of patients with prion diseases or non-neurodegenerative causes of RPD, analyses considering the association between clinical features and clinical diagnoses were limited to those individuals with a diagnosis of amnestic AD dementia versus other NDI (including patients with CJD). The contributions of variables identified in Table 2 to the etiological diagnoses of RPD were considered via forward step-wise logistic regression, controlling for age and gender. Older age at first diagnosis (odds ratio [OR]=2.1 for each decade of age; 95% CI, 1.1-3.8; p=0.02) was associated with an increased probability of RPD due to amnesticAD dementia; while the detection of cortical visual signs (OR=10.8; 95% CI, 1.7-69.5; p=0.01) and/or parkinsonism (OR=6.9; 95% CI, 1.6-30.5; p=0.01) predicted an increased likelihood of RPD due to another NDI. The overall model accounted for a statistically significant (χ2=19.8, df=4, p=0.001), but clinically modest amount of variance (c-statistic=0.781). Model fit was adequate (Hosmer-Lemeshow lack-of-fit test: χ2=8.91, df=8, p=0.35).

Table 2:

Demographic features, presenting complaints and examination findings at RPD designation, stratified by clinical diagnosis.

| Patient demographics and clinical features | Amnestic AD dementia (n=34) | Other NDI (n=26) | Prion disease (n=4) | Other (n=3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at onset, median (range), y | 72.6 (45.4-89.6) | 65.2 (48.9-85.5) | 68.8 (50.0-81.5) | 59.1 (49.4-76.4) |

| Female, No. (%) | 25 (74) | 16 (62) | 0 | 1 (33) |

| Education duration, median (range), y | 12 (6-20) | 12.5 (9-20) | 12(12-16) | 12 |

| Presenting Complaints | ||||

| Memory loss | 31 (91) | 23 (89) | 2 (50) | 3 (100) |

| Behavioral change | 11 (32) | 12 (46) | 1 (25) | 1 (33) |

| Visuospatial dysfunction | 3 (9) | 5 (19) | 1 (25) | 0 |

| Language impairment | 5 (15) | 7 (27) | 0 | 1 (33) |

| Other | 5 (15) | 8 (30) | 2 (50) | 0 |

| Examination Findings | ||||

| Normal examination | 11 (32) | 4 (15) | 0 | 3 (100) |

| Psychosis | 12 (35) | 8 (31) | 0 | 0 |

| Aphasia | 9 (27) | 7 (27) | 1 (25) | 0 |

| Cortical visual loss | 2 (6) | 7 (27) | 3 (75) | 0 |

| Cortical sensorimotor loss | 9 (27) | 7 (27) | 1 (25) | 0 |

| Parkinsonism | 8 (24) | 12 (46) | 1 (25) | 0 |

| Cerebellar signs | 3 (9) | 2 (8) | 2 (50) | 0 |

| Gait impairment | 17 (50) | 15 (58) | 2 (50) | 0 |

| Summary measures | ||||

| global CDR | 2 (0.5-3) | 1 (0.5-3) | 1 (0.5-2) | 1 (0.5-3) |

| CDR sum-of-boxes | 9.5 (1.5-18) | 6.5 (1.0-18) | 5.0 (2.0-12.0) | 2.5 (1.5-12.0) |

| MMSE | 14 (2-28) | 18 (2-28) | 18 (5-18) | 19 (16-22) |

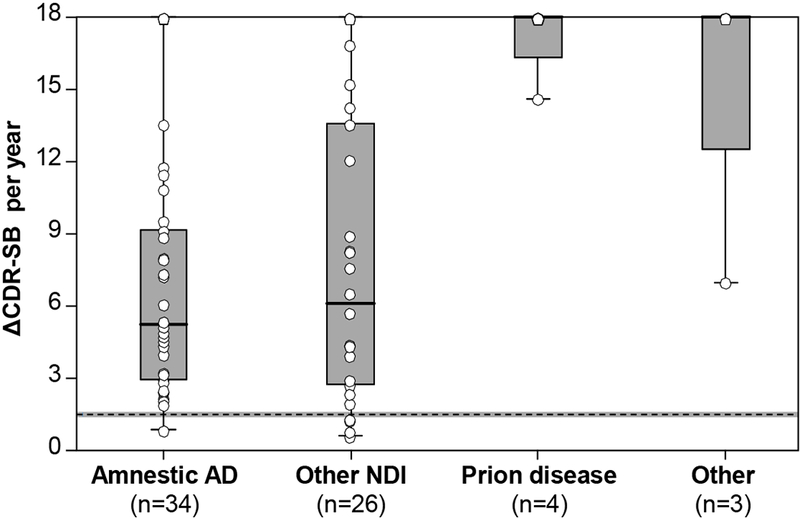

The median annualized rate of change in CDR-SB from symptom onset to diagnosis was 6.5 units/year (range, 0.6-18.0) across all individuals. The most extreme rates of progression were observed in the limited number of individuals with RPD due to prion disease (mean 17.4 units/year; 95% CI, 12.4-18.0) or “other” (non-neurodegenerative) causes (mean 15.5 units/year; 95% CI, 9.7-18.0; Figure 1). When controlling for the effects of age, annualized rates of progression were higher in patients with prion disease than those with amnestic AD dementia (mean difference 11.0; 95% CI, 3.8-18.0; p=0.001), or another NDI (9.2; 95% CI, 2.0-16.5; p=0.006); and higher in patients with an “other” (non-neurodegenerative) cause than those with amnestic AD dementia (9.1, 95% CI, 0.9-17.3; p=0.02), but not those with another NDI (7.3; 95% CI, −0.9-15.6; p=0.1). No differences were observed between patients with RPD due to amnestic AD dementia or another NDI (mean difference, −1.8; 95% CI, −5.3-1.8; p>0.99), or those with RPD due to prion disease or “other” (non-neurodegenerative) causes (1.9; 95% CI, −8.4-12.2; p>0.99).

Figure 1:

Rates of change in CDR-SB at diagnosis. The annualized rate of change in the CDR-SB is shown at the time of RPD designation, stratified by clinical diagnosis. Annualized rates of change were greatest in patients with RPD due to prion disease or “other” (non-neurodegenerative) causes. Differences were evaluated using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), controlling for age, and adjusting for multiple comparisons. The dashed horizontal line depicts mean annualized rates of change reported in patients with typical amnestic AD dementia (±95% CI).21

Active secondary diagnoses with the potential to affect cognition were more common in patients with RPD due to amnestic AD dementia, affecting 56% (19/34) of patients with amnestic AD dementia, 15% (4/26) of patients with other NDI, and no patients with prion disease or other (non-neurodegenerative) causes (Fisher’s exact test, two-sided; p=0.001). Depression was the most common secondary diagnosis (amnestic AD dementia=27%, other NDI=4%), followed by cerebrovascular disease (amnestic AD dementia=12%, other NDI=12%) and sleep dysfunction (amnestic AD dementia=27%, other NDI=0%).

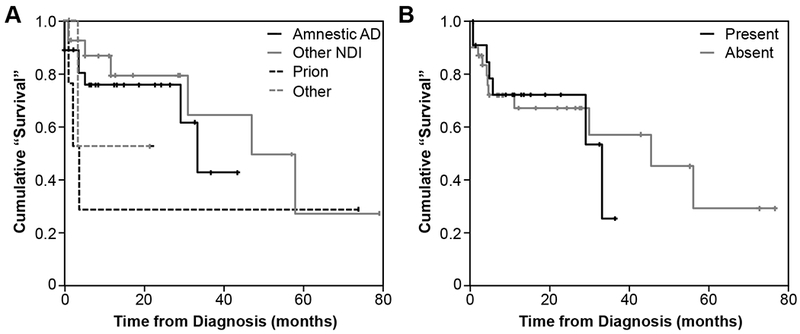

Outcome data was available for 79% (53/67) of participants. Of these, 32% (17/53) died of their dementing illness during the study period (median time from symptom onset to death, 12.4 months; range, 2.7-76.9). One patient with a non-NDI diagnosis (radiation/chemotherapy-induced leukoencephalopathy) died of metastatic lung cancer. Kaplan-Meier survival curves are shown in Figure 2. No differences in survival were observed between participants with amnestic AD dementia and other NDI (log-rank: p>0.05 for all pair-wise comparisons; Figure 2A). Secondary clinical diagnoses did not affect survival (log-rank: χ2=0.06, df=1, p=0.81; Figure 2B).

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier ‘survival’ curves. A. Depicting time from diagnosis to death or severe dementia (CDR 3), stratified by clinical diagnosis. B. Depicting time from diagnosis to death or severe dementia (CDR 3), stratified by the presence or absence of secondary diagnoses. Events were defined as death or the development of severe dementia (CDR 3). Participants lost to follow-up were censored at the time of their last assessment. No differences were noted in time to outcome across groups (log-rank statistics, p>0.05).

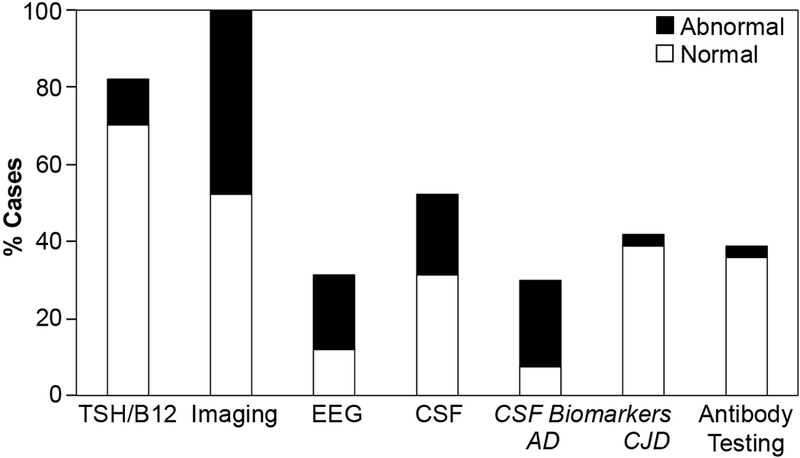

Serum screening tests, neuroimaging (MR imaging in 62/67, 93%), and routine CSF analyses were performed in the majority of patients, while routine EEG, and CSF and serum biomarkers studies were ordered less frequently (Figure 3). When CSF was obtained, commercially available AD biomarkers were measured in 60% (21/35), and CJD biomarkers in 80% (28/35) of patients. CSF levels of amyloid-β42, total-tau and phosphorylated-tau were “consistent with AD” in 76% (16/21) of patients tested for AD biomarkers, including 11 patients with clinical diagnoses of amnestic AD dementia, three patients with PCA, and one patient each with cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation and mixed-vascular dementia. CSF biomarkers for CJD were consistent with CJD in two (7%) of 28 patients tested. One patient had a corresponding clinical diagnosis of CJD (total tau, 1528 pg/ml; 14-3-3, “negative”; RT-QuIC, “positive”), with a compatible clinical course and neuroimaging findings. Biomarkers were interpreted as “consistent with CJD” in the other patient (total tau, 1258 pg/ml; 14-3-3, “equivocal”; RT-QuIC, not available); however, the clinical course was more protracted (progression of symptoms over 4+ years), and MR neuroimaging did not support the diagnosis. Subsequent CSF analyses demonstrated a biomarker profile compatible with AD (decreased amyloid-β42, 318.9 pg/ml; increased phosphorylated tau, 111.75 pg/ml), supporting the clinical diagnosis of rapidly progressive amnestic AD dementia. Testing for autoantibodies known to associate with autoimmune encephalitis was performed in the serum of 21 and CSF of 15 patients (both in 10 patients). Moderate titers of autoantibodies against anti-ganglionic acetylcholine receptor and voltage-gated calcium channel (P/Q) antigens were identified in the serum but not the CSF of two patients with a clinical diagnosis of amnestic AD dementia. In both cases, autoantibodies were deemed unlikely to contribute to RPD. No other potentially relevant autoantibodies were detected.

Figure 3:

Diagnostic testing in RPD patients. The prevalence of diagnostic testing performed in RPD patients is depicted together with the frequency of abnormal test results. CSF biomarker profiles deemed consistent with AD or CJD were labelled as “abnormal”. Similarly, the detection of disease-associated autoantibodies in serum or CSF were labelled “abnormal”.

Discussion

Rapidly progressive NDI accounted for 90% of RPD cases diagnosed and managed in our outpatient memory clinic across a 10-year period. Of these, rapidly progressive amnestic AD dementia represented the most common diagnosis. “Other NDI” were the second-most commonly encountered etiologies, including patients with PCA and logopenic variant PPA. As the majority of cases of PCA and logopenic variant PPA are attributable to AD pathology,28,32 AD was the most common cause of RPD in our outpatient memory clinic. These findings are consistent with prior reports in RPD patients,1–3,5,8,9,30 and with estimates of dementia subtypes reported in older (>68 years) United States Medicare beneficiaries with typically progressive dementia.33 Together, these findings establish AD and other NDI as common causes of rapidly and typically progressive dementias in older individuals encountered in outpatient clinics. Although comorbid diseases or exposures with the potential to affect rates of progression were commonly observed in our cohort (i.e., vascular disease, sleep dysfunction, anxiety or depression), these secondary diagnoses did not alter rates of dementia progression, including the time to development of severe dementia or death. This finding adds to the literature suggesting that rapidly progressive variants of NDI represent distinct disease presentations.3,34

The results of this study may inform the evaluation of outpatients with RPD. In this series, standardized clinical assessments and typical diagnostic tests were used to establish a reliable clinical diagnosis, with excellent inter-rater reliability. These findings suggest that rapidly progressive NDI can reliably be diagnosed in the outpatient setting using standard approaches to dementia assessment. In particular, the detection of parkinsonism or cortical visual dysfunction in patients with RPD should raise suspicion of atypical NDI and/or prion diseases. The absence of these findings may make a diagnosis of amnestic AD dementia more likely—particularly in the older patient.

Consistent with guidelines for the evaluation of patients with typically progressive dementia, routine serum studies and neuroimaging (favoring MR) were completed in the vast majority of RPD patients.22,35 However, somewhat unexpectedly, not all investigations routinely recommended for the evaluation of RPD patients were completed in clinic patients.2,6,7 In particular, CSF analyses and EEG were performed in a minority of patients. This may reflect clinicians’ hesitancy to subject outpatients with suspected NDI to extensive testing, or challenges associated with coordinating testing outside of the hospital environment. In the absence of evidence supporting a more refined outpatient approach, we continue to assert that “core tests” (serum studies, neuroimaging, EEG and CSF analysis2,6,7) should be completed in all patients with RPD. This recommendation acknowledges the diagnostic and therapeutic value of abnormal CSF (e.g., elevated CSF leukocytes supporting an autoimmune, inflammatory or infectious cause) and EEG findings (e.g., temporal epileptiform discharges implying focal temporal lobe epilepsy) in informing the clinical diagnosis.

Beyond standard tests, the sensitivity, specificity and limitations of available CSF biomarkers of AD (i.e., amyloid-β42, total-tau, and phosphorylated tau) are well defined in patients with NDI,36 with the potential to affirm or refute the clinical diagnosis when interpreted appropriately in RPD patients.37 Similarly, the high sensitivity and specificity of CJD biomarkers (total-tau, 14-3-3 and RT-QuIC12–14) supports the routine use of these measures in the evaluation of RPD patients—particularly when results are interpreted together with clinical and neuroimaging findings. The role of routine testing for autoantibodies in older outpatients with RPD is less clear. Autoantibody testing did not influence the clinical diagnoses in patients in this study. Accordingly, we suggest that autoantibody testing in serum and CSF should be limited to patients with clinical, radiologic or CSF findings suggestive of an autoimmune / inflammatory cause of RPD.38,39 Whether autoantibody testing should be routinely performed in younger RPD patients remains unknown, recognizing that autoimmune / inflammatory contributions to RPD may be more common in patients ≤45 years-old.17

This retrospective case series is subject to several limitations. All patients were assessed at a single center, yielding a modest study size. As a result, it was not possible to robustly evaluate the interactions between multiple variables across patient subgroups. Additionally, as this study exclusively evaluated older outpatients in a tertiary-care memory clinic, our findings are best used to inform the care of patients in similar settings. In this context, the focus of our study can be interpreted as a relative strength, providing useful insights into the causes and contributors to RPD in the outpatient setting, where the majority of neurological care is delivered. Finally, we acknowledge that the low rate of pathological confirmation raises questions concerning the validity of clinical diagnoses. The low autopsy rate reflects a general shift away from routine autopsies in clinical practice.40 However, as clinical and pathologically-confirmed diagnoses may diverge in ~15% of individuals undergoing systematic dementia assessments,41 the importance of pathologic verification of suspected diagnoses is clear. Increasing access to in vivo disease-specific biomarkers may further decrease the perceived need for autopsy in patients with suspected NDI. The importance of autopsy confirmation should continue to be emphasized in patients with atypical clinical presentations, including RPD, recognizing the critical role of pathologic confirmation in establishing the sensitivity and specificity of emergent disease biomarkers,42 and in deciphering the contributions of multiple neurodegenerative pathologies to the clinical presentation of disease.43

Conclusions:

Atypical presentations of typical NDI (especially amnestic AD dementia) accounted for the majority of causes of RPD in older patients assessed and managed in our outpatient memory clinic. The clinical evaluation should be adapted to promote detection of common causes of RPD, specific to the practice setting. In the outpatient clinic, our experience suggests that diagnoses can be reliably established by integrating information from history and physical examination, together with results from serum studies, neuroimaging, CSF analyses and routine EEG. Disease-specific CSF biomarkers may be leveraged to increase confidence in the clinical diagnosis, but do not replace the need for autopsy to confirm the final diagnosis.

Acknowledgements:

The Authors wish to thank Mr. Gregory Alcazeren for assistance with data extraction and analysis during his Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center summer studentship, and Dr. Rohini Samudralwar for providing useful comments on the manuscript. This project was supported by a career development grant (GS Day: Weston Brain Institute and American Brain Foundation), and by an endowed post-doctoral fellowship (GS Day: Neiss-Gain Fellowship) through the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center.

Study funding and Author Disclosures:

GS Day is involved in research supported by an in-kind gift of radiopharmaceuticals from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, and is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs sponsored by Eli Lilly. He holds stocks (>$10,000) in ANI Pharmaceuticals (a generic pharmaceutical company).

ES Musiek is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs sponsored by the A4 (The Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease) trial, and has consulted for Eisai Pharmaceuticals. He is funded by NIH grants R01AG054517 and P50AG005681.

JC Morris is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs from Eli Lilly and Company, Biogen, and Janssen. Dr. Morris serves as a consultant for Lilly USA. He receives research support from Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and is funded by NIH grants # P50AG005681; P01AG003991; P01AG026276 and UF01AG032438. Neither Dr. Morris nor his family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company.

References

- 1.Poser S, Mollenhauer B, Krauβ A, et al. How to improve the clinical diagnosis of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Brain. 1999;122(12):2345–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geschwind MD, Shu H, Haman A, Sejvar JJ, Miller BL. Rapidly progressive dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(1):97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Parisi JE, et al. Rapidly progressive neurodegenerative dementias. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(2):201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papageorgiou SG, Kontaxis T, Bonakis A, Karahalios G, Kalfakis N, Vassilopoulos D. Rapidly progressive dementia: causes found in a Greek tertiary referral center in Athens. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sala I, Marquie M, Sanchez-Saudinos MB, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia: experience in a tertiary care medical center. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26(3):267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day GS, Tang-Wai DF. When dementia progresses quickly: a practical approach to the diagnosis and management of rapidly progressive dementia. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2014;4(1):41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geschwind MD. Rapidly Progressive Dementia. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016;22(2 Dementia):510–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Everbroeck B, Dobbeleir I, De Waele M, De Deyn P, Martin JJ, Cras P. Differential diagnosis of 201 possible Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease patients. J Neurol. 2004;251(3):298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinemann U, Krasnianski A, Meissner B, et al. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in Germany: a prospective 12-year surveillance. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 5):1350–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiga Y, Miyazawa K, Sato S, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI abnormalities as an early diagnostic marker for Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Neurology. 2004;63:443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinhoff BJ, Zerr I, Glatting M, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Poser S, Kretzschmar HA. Diagnostic value of periodic complexes in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;56(5):702–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muayqil T, Gronseth G, Camicioli R. Evidence-based guideline: diagnostic accuracy of CSF 14-3-3 protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: report of the guideline development subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012;79(14):1499–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foutz A, Appleby BS, Hamlin C, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of human prion detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(1):79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamlin C, Puoti G, Berri S, et al. A comparison of tau and 14-3-3 protein in the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 2012;79(6):547–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wile DJ, Warner J, Murphy W, Lafontaine AL, Hanson A, Furtado S. Referrals, Wait Times and Diagnoses at an Urgent Neurology Clinic over 10 Years. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2014;41(2):260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anuja P, Venugopalan V, Darakhshan N, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia: An eight year (2008-2016) retrospective study. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley BJ, Boeve BF, Josephs KA. Young-onset dementia: demographic and etiologic characteristics of 235 patients. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(11):1502–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Group GNDC. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neuro. 2017;16:877–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams MM, Storandt M, Roe CM, Morris JC. Progression of Alzheimer’s disease as measured by Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes scores. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1 Suppl):S39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forman MS, Farmer J, Johnson JK, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathological correlations. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(6):952–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. 2013;80(5):496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josephs KA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of frontotemporal and corticobasal degenerations and PSP. Neurology. 2006;66(1):41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crutch SJ, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, et al. Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(8):870–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Brien JT, Erkinjuntti T, Reisberg B, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(2):89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zerr I, Kallenberg K, Summers DM, et al. Updated clinical diagnostic criteria for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 10):2659–2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1987;149(2):351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santos-Santos MA, Rabinovici GD, Iaccarino L, et al. Rates of Amyloid Imaging Positivity in Patients With Primary Progressive Aphasia. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(3):342–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodman RA, Lochner KA, Thambisetty M, Wingo TS, Posner SF, Ling SM. Prevalence of dementia subtypes in United States Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, 2011-2013. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(1):28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt C, Haik S, Satoh K, et al. Rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease: a multicenter update. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30(4):751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56(9):1143–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fagan AM, Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomark Med. 2010;4(1):51–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoeck K, Sanchez-Juan P, Gawinecka J, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker supported diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and rapid dementias: a longitudinal multicentre study over 10 years. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 10):3051–3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):391–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Long JM, Day GS. Autoimmune Dementia. Semin Neurol. 2018;38(3):303–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ayoub T, Chow J. The conventional autopsy in modern medicine. J R Soc Med. 2008;101(4):177–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beach TG, Monsell SE, Phillips LE, Kukull W. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005-2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(4):266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Day GS, Gordon BA, Perrin RJ, et al. In vivo [(18)F]-AV-1451 tau-PET imaging in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 2018;90(10):e896–e906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69(24):2197–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]