Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the quality of information available online for abortion self-referral and to determine whether quality varies by region or distance to an abortion provider.

METHODS:

This was a cross-sectional study. We used a standard protocol to perform internet searches for abortion services in the 25 most populous U.S. cities and the 43 state capitals that were not one of the 25 most populous cities from August 2016 to June 2017. We classified the first ten webpage results and the first five map results and ads as facilitating abortion referral (local independent abortion provider; local Planned Parenthood facility; national abortion provider or organization; pro-choice website; or abortion directory), not facilitating abortion referral (non-providing physician office; non-medical website; abortion provider >50 miles from the location; news article; general directory; other), or hindering abortion referral (crisis pregnancy center or anti-choice website). We used U.S. Census Bureau sub-regions to examine geographic differences. We made comparisons using a chi-square test.

RESULTS:

Overall, from 612 searches from 68 cities, 52.9% of webpage results, 67.3% of map results, and 34.4% of ads facilitated abortion referral, while 12.9%, 21.7%, and 29.9%, respectively, hindered abortion referral. The content of the searches differed significantly based on U.S. Census Bureau sub-region (all P≤0.001) and distance to an abortion provider (all P≤0.02).

CONCLUSION:

Two thirds of map results facilitated abortion self-referral, while only half of webpage results did so. Ads were the least likely to facilitate and the most likely to hinder self-referral. Quality was lowest in areas that were farthest from abortion providers.

Précis:

While the internet may be a viable source of abortion self-referral, it seems least useful for those in greatest need of help finding an abortion provider.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, over 900,000 abortions are performed yearly.1 Despite it being a common and legal procedure, individuals seeking abortions may have difficulty finding an abortion provider, leading to delays in obtaining care. In a 2006 study of people seeking abortion in California, 7% seeking a first-trimester abortion reported difficulty locating an abortion provider, and 13% were initially referred to a clinic that could not perform the abortion; among those seeking second-trimester abortions, these proportions were 20% and 47%, respectively.2 Although 85% of surveyed clinics receiving federal family planning funds reported having a list of abortion providers available,3 such a list does not guarantee appropriate referrals, and a rule proposed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in June 2018 would bar these organizations from providing appropriate referrals for abortion services.4 A study using a simulated patient seeking abortion services found that only 28% of community-based obstetrician-gynecologist clinics offered a referral without being prompted by the simulated patient, and fewer than half offered a referral upon being directly asked for one.5

Despite the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee Opinion stating that all health care providers must provide accurate and unbiased information so patients can make informed decisions,6 individuals may not be able to obtain appropriate referrals even after pregnancy diagnosis at a clinic visit. Although a study in Massachusetts found that most people successfully obtained a referral from a health care provider,7 a study in Nebraska found that only one-third received any referral and 16% of those referrals were inappropriate.8 Nearly one-third of surveyed obstetrics and gynecology and family medicine clinicians in Nebraska reported they would not refer for abortion services, similar to a national survey,9 and 15% reported they would instead refer either to a health care provider who did not offer abortions or to an adoption agency or crisis pregnancy center,10 which is a facility that does not refer for abortion care. National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra decided in 2018 on free speech grounds that California could not compel these organizations to provide referrals for abortion services.11

Given the potential difficulty in obtaining referrals through traditional methods, individuals may use the internet to locate abortion care, as the internet is a convenient information source.12 Nearly all young people in the U.S. use the internet,13 and in 2015 there were 3.4 million Google searches for abortion clinics in the U.S.14 Studies in Nebraska8 and South Carolina16 found that many patients presenting for abortion care had successfully self-referred using the internet.

We hypothesized that a substantial proportion of the results obtained when seeking information about where to obtain an abortion would not help an individual locate abortion care. We hypothesized also that geography and distance to an abortion provider would affect the proportion of results that helped an individual locate abortion care. Our primary aim was to determine the proportion of search results that facilitated abortion referral, did not facilitate abortion referral, or hindered abortion referral, as shown in Boxes 1-3, respectively. Our secondary aim was to compare the quality of information obtained by geographic regions and distance to an abortion provider.

Box 1. Description of how data were summarized for results that facilitated abortion referral.

Local* independent abortion provider

Facilities within 50 miles of the city of interest that provide abortion services for the local population but were not part of a larger network such as Planned Parenthood (e.g., standalone clinics, private physician offices, hospital-based services)

Local* Planned Parenthood facility

Planned Parenthood facility within 50 miles of the city of interest

National abortion provider or organization

General websites of national networks of abortion providers (e.g., Planned Parenthood, the National Abortion Federation)

Pro-choice web site

Organizations that provided online or phone referrals to abortion providers

Abortion directory†

Box 3. Description of how data were summarized for results that hindered abortion referral.

Local crisis pregnancy center

Facilities that provide in-person services such as ultrasounds, pregnancy testing, or “options counseling” but do not provide abortion services or refer elsewhere for abortion services

National crisis pregnancy center

Facilities that provide referrals to local crisis pregnancy centers but not to abortion providers

Anti-abortion web site

Organizations that provide online or phone services to either refer women to crisis pregnancy centers or discourage them from having abortions

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used the Google Chrome web browser to search the Google, Bing, and Yahoo search engines for the following search terms: 1) “abortion” AND “city, state”; 2) “abortion provider” AND “city, state”; and 3) “where to get an abortion” AND “city, state.” We designed these terms with the assumption that an individual using these terms would be searching specifically to locate abortion services and not searching for general information about abortion or for places to obtain other types of care. We turned location services off, which prevents the computer from sending the latitude and longitude to the search engine; the search engine will use the city name included in the search and the location of the computer to geolocate the search. We performed searches in incognito mode to prevent the browser from storing the browsing history, which could affect the search results. We searched the 25 most populous cities in the United States and the 43 state capitals that were not one of the 25 most populous cities (Table 1) to obtain a sample of convenience. Searches were performed from August 2016 to June 2017.

Table 1.

U.S. states by U.S. Census Bureau region and sub-region

| Region | Sub-region | Cities and states |

|---|---|---|

| Northeast | New England | Hartford, CT; Augusta, ME; Boston, MA; Concord, NH; Providence, RI; Montpelier, VT |

| Middle Atlantic | Trenton, NJ; Albany, NY; New York, NY; Harrisburg, PA; Philadelphia, PA | |

| South | South Atlantic | Dover, DE; Jacksonville, FL; Tallahassee, FL; Atlanta, GA; Annapolis, MD; Charlotte, NC; Raleigh, NC; Columbia, SC; Richmond, VA; Washington, DC; Charleston, WV |

| East South Central | Montgomery, AL; Frankfort, KY; Jackson, MS; Memphis, TN; Nashville, TN | |

| West South Central | Little Rock, AR; Oklahoma City, OK; Baton Rouge, LA; Austin, TX; Dallas, TX; El Paso, TX; Fort Worth, TX; Houston, TX; San Antonio, TX | |

| Midwest | East North Central | Chicago, IL; Springfield, IL; Indianapolis, IN; Detroit, MI; Lansing, MI; Columbus, OH; Madison, WI |

| West North Central | Des Moines, IA; Topeka, KS; Jefferson City, MO; St. Paul, MN; Lincoln, NE; Bismarck, ND; Pierre, SD | |

| West | Mountain | Phoenix, AZ; Denver, CO; Boise, ID; Helena, MT; Carson City, NV; Santa Fe, NM; Salt Lake City, UT; Cheyenne, WY |

| Pacific | Juneau, AK; Los Angeles, CA; Sacramento, CA; San Diego, CA; San Francisco, CA; San Jose, CA; Honolulu, HI; Salem, OR; Olympia, WA; Seattle, WA |

Web searches using the three search engines returned three categories of results— 1) webpage results, which are the main search results and lead to webpages; 2) map results, which are shown as locations on an inset map; and 3) ads, which are shown at the top, side, and/or bottom of the page, around the webpage results. We categorized all of the results shown on the first page, which included up to 10 webpage results and up to five map results and ads; in rare cases where more search results appeared on the first page, we included only the first 10 webpages and the first five maps results and ads. We used only the first page of the search because previous work has shown that sites listed on the first page generate 92% of all traffic from an average search.17

Data that facilitated abortion referral consisted of information that would theoretically allow the searcher to locate abortion services, while data that hindered abortion referral consisted of information that would potentially make it more difficult for the searcher to locate abortion services (e.g., a listing for an entity that does not provide referrals for the desired care). Data that did not facilitate abortion referral consisted of information that would be expected to have a neutral effect, i.e., it would not affect the searcher’s ability to successfully locate abortion services. If the website did not provide a clear indication of its proper categorization (e.g., abortion provider or crisis pregnancy center), one of the authors called the organization to determine whether they provided or referred for abortion services. Results that facilitated abortion referral were considered to be high quality, while results that hindered abortion referral were considered to be low quality with respect to the searcher’s goal of identifying an abortion provider. We report data as counts and proportions, and we anonymized search engines, as our objective was to describe the overall quality of information available online for abortion self-referral and not to compare individual search engines. To examine geographic differences, we stratified findings using U.S. Census Bureau sub-regions (Table 1). We performed sub-analyses based on distance of the location to a publicly-listed abortion provider; these abortion providers were listed by the National Abortion Federation or Planned Parenthood or found on internet searches for abortion providers. We categorized locations as those <50 miles from an abortion provider, those 50-99 miles from an abortion provider, and those ≥100 miles from an abortion provider. We made comparisons using the chi-square test. We considered P values <0.05 to be statistically significant, and all tests were two sided. We used SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism version 6 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) for all analyses. The Committee on Clinical Investigations at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center determined this study to be non-human subjects research.

RESULTS

We performed 612 searches using three search engines and three sets of search terms for 68 cities. The number of searches performed in the Northeast, South, Midwest, and West were 99 (16.2%), 225 (36.8%), 126 (20.6%), and 162 (26.5%), respectively. Among all cities searched, 477 (77.9%) were <50 miles from an abortion provider, 99 (16.2%) were 50-99 miles from an abortion provider, and 36 (5.9%) were ≥100 miles from an abortion provider.

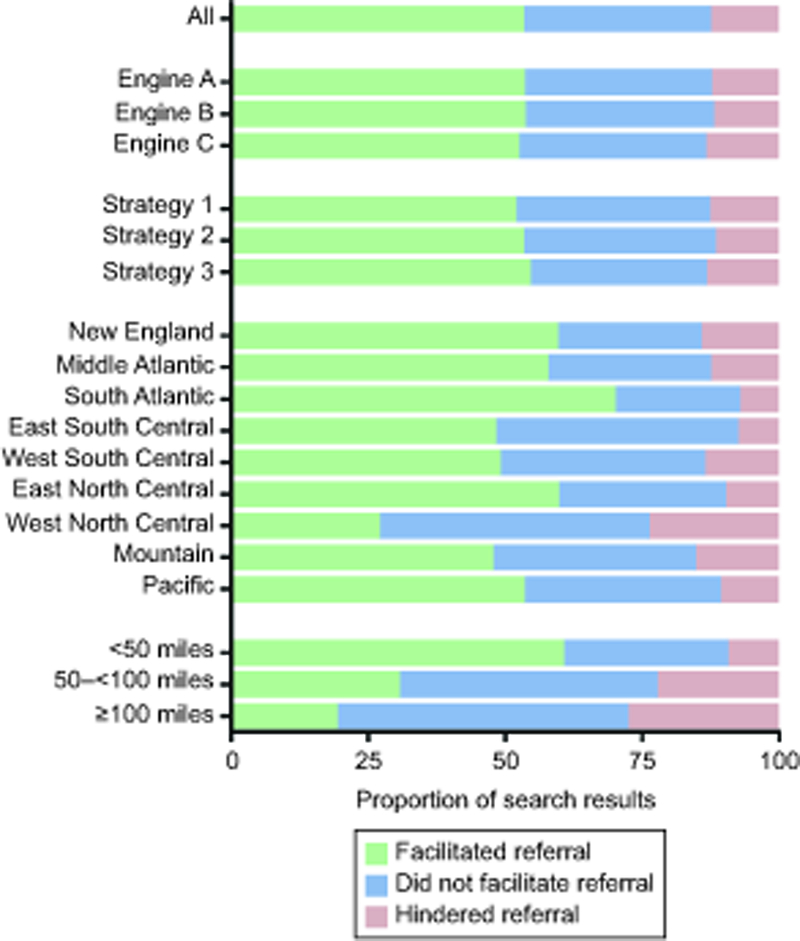

Each search returned varying numbers of results, and some searches showed fewer than 10 webpages, 5 map results, and 5 ads on the first page of results. Thus, we classified 5,800 webpage results, 1,543 map results, and 2,027 ads. Among all webpage results, 3,066 (52.9%) facilitated referral, 750 (12.9%) hindered referral, and 1,984 (34.2%) did not facilitate referral. The first search result facilitated referral 80.2% (n=489) of the time and hindered referral 4.8% (n=29) of the time. We found no difference in the proportion of searches that facilitated, hindered, or provided no referral returned by the three sets of search terms (P=0.13). Additionally, substantial geographical differences emerged when looking at the results using all three search engines individually and combined (P<0.001). Searches facilitating referral ranged from a high of 69.7% (n=654) in the South Atlantic sub-region to a low of 26.7% (n=163) in the West North Central sub-region, which also had the highest proportion of searches hindering referral at 24.3% (n=149) (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Proportion of webpage results that facilitated, did not facilitate, and hindered abortion self-referral

| Characteristic | Facilitated abortion self- referral |

Did not facilitate abortion self-referral |

Hindered abortion self- referral |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All webpages (n=5,800) | 3,066 (52.9) | 1,984 (34.2) | 750 (12.9) | |

| Search engine | 0.71 | |||

| A (n=1,977) | 1,052 (53.2) | 674 (34.1) | 251 (12.7) | |

| B (n=1,795) | 957 (53.3) | 618 (34.4) | 220 (12.3) | |

| C (n=2,028) | 1,057 (52.1) | 692 (34.1) | 279 (13.8) | |

| Search strategy | 0.13 | |||

| ”Abortion” and city (n=1,990) | 1,027 (51.6) | 703 (35.3) | 260 (13.1) | |

|

”Abortion clinic” and city

(n=1,925) |

1,018 (52.9) | 676 (35.1) | 231 (12.0) | |

|

”Where to get an abortion”

and city (n=1,885) |

1,021 (54.2) | 605 (32.1) | 259 (13.7) | |

| Subregion | <0.001 | |||

| New England (n=520) | 308 (59.2) | 136 (26.2) | 76 (14.6) | |

| Middle Atlantic (n=439) | 252 (57.4) | 131 (29.8) | 56 (12.8) | |

| South Atlantic (n=938) | 654 (69.7) | 213 (22.7) | 71 (7.6) | |

| East South Central (n=428) | 205 (47.9) | 189 (44.2) | 34 (7.9) | |

| West South Central (n=758) | 369 (48.7) | 283 (37.3) | 106 (14.0) | |

| East North Central (n=588) | 349 (59.4) | 179 (30.4) | 60 (10.2) | |

| West North Central (n=614) | 163 (26.7) | 302 (49.2) | 149 (24.3) | |

| Mountain (n=675) | 320 (47.4) | 250 (37.0) | 105 (15.6) | |

| Pacific (n=840) | 446 (53.1) | 301 (35.8) | 93 (11.1) | |

| Distance to abortion provider | <0.001 | |||

| <50 miles (n=4,494) | 2,710 (60.3) | 1,349 (30.0) | 435 (9.7) | |

| 50 -<100 miles (n=962) | 291 (30.3) | 452 (47.0) | 219 (22.8) | |

| ≥100 miles (n=344) | 65 (18.9) | 183 (53.2) | 96 (27.9) |

Figure 1.

The proportion of webpage results facilitating, hindering, and not facilitating referral stratified by anonymous search engine (Google, Bing, or Yahoo), search strategy (1: “abortion” and location; 2: “abortion clinic” and location; 3: “where to get an abortion” and location), and Census Bureau subregion, and distance to an abortion provider.

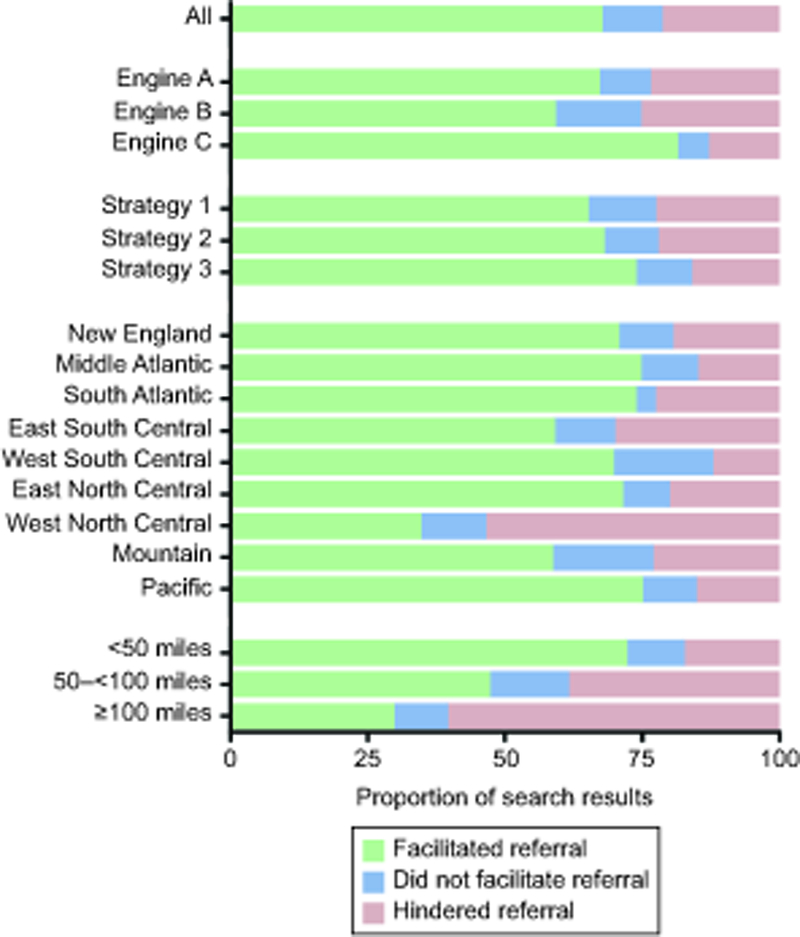

We classified 1,543 map results. Among all map results, 1,039 (67.3%) facilitated referral, while 335 (21.7%) hindered referral, and 169 (11.0%) did not facilitate referral. As with webpage searches, the first map result usually facilitated referral (n=417, 83.4%) and less frequently hindered referral (n=65, 13.0%). There were no differences based on the set of search terms (P=0.09). Notably, the “where to get an abortion” search strategy returned many fewer map results (n=245) than either the “abortion” (n=663) or “abortion clinic” (n=635) strategy; we found no differences in the proportion of the first map result that facilitated, hindered, or did not facilitate by search terms (P=0.74).

As with the webpage results, we found significant differences in the map results by geography (P<0.001), with the West North Central sub-region having both the lowest proportion of searches facilitating referral (n=35, 34.3%) and the highest proportion of searches hindering referral (n=55, 53.9%). Among the remaining sub-regions, the proportion of searches facilitating referral ranged from 58.3-74.6%, and the proportion hindering referral ranged from 12.5-30.4% (Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 3.

Proportion of map results that facilitated, did not facilitate, and hindered abortion self-referral

| Characteristic | Facilitated abortion self- referral |

Did not facilitate abortion self-referral |

Hindered abortion self- referral |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All map results (n=1,543) | 1,039 (67.3) | 169 (11.0) | 335 (21.7) | |

| Search engine | <0.001 | |||

| A (n=482) | 322 (66.8) | 45 (9.3) | 115 (23.9) | |

| B (n=640) | 376 (58.8) | 100 (15.6) | 164 (25.6) | |

| C (n=421) | 341 (81.0) | 24 (5.7) | 56 (13.3) | |

| Search strategy | 0.09 | |||

| ”Abortion” and city (n=663) | 429 (64.7) | 82 (12.4) | 152 (22.9) | |

|

”Abortion clinic” and city

(n=635) |

430 (67.7) | 62 (9.8) | 143 (22.5) | |

|

”Where to get an abortion”

and city (n=245) |

180 (73.5) | 25 (10.2) | 40 (16.3) | |

| Subregion | <0.001 | |||

| New England (n=121) | 85 (70.3) | 12 (9.9) | 24 (19.8) | |

| Middle Atlantic (n=117) | 87 (74.4) | 12 (10.3) | 18 (15.4) | |

| South Atlantic (n=287) | 211 (73.5) | 10 (3.5) | 66 (23.0) | |

| East South Central (n=92) | 54 (58.7) | 10 (10.9) | 28 (30.4) | |

| West South Central (n=232) | 161 (69.4) | 42 (18.1) | 29 (12.5) | |

| East North Central (n=176) | 125 (71.0) | 15 (8.5) | 36 (20.5) | |

| West North Central (n=102) | 35 (34.3) | 12 (11.8) | 55 (53.9) | |

| Mountain (n=180) | 105 (58.3) | 33 (18.3) | 42 (23.3) | |

| Pacific (n=236) | 176 (74.6) | 23 (9.8) | 37 (15.7) | |

| Distance to abortion provider | <0.001 | |||

| <50 miles (n=1,304) | 936 (71.8) | 137 (10.5) | 231 (17.7) | |

| 50 -<100 miles (n=188) | 88 (46.8) | 27 (14.4) | 73 (38.8) | |

| ≥100 miles (n=51) | 15 (29.4) | 5 (9.8) | 31 (60.8) |

Figure 2.

The proportion of location results facilitating, hindering, and not facilitating referral stratified by anonymous search engine (Google, Bing, or Yahoo), search strategy (1: “abortion” and location; 2: “abortion clinic” and location; 3: “where to get an abortion” and location), and Census Bureau subregion, and distance to an abortion provider.

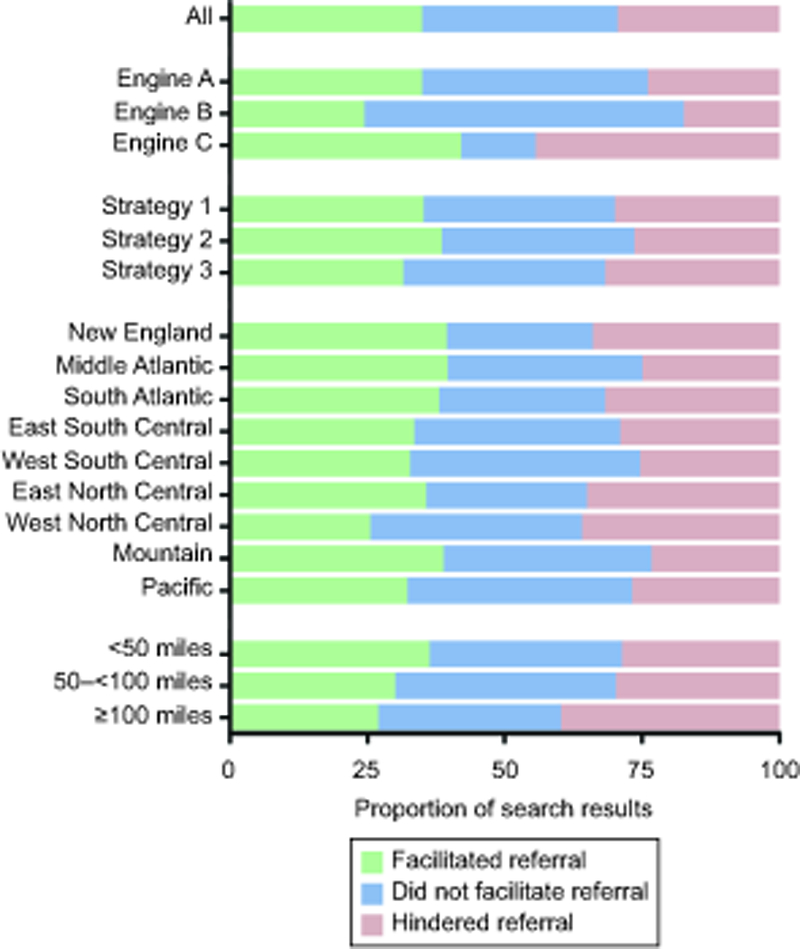

Of 2,027 ads, similar proportions facilitated (n=697, 34.4%), hindered (n=606, 29.9%), and did not facilitate (n=724, 35.7%) referral, though the proportions that facilitated and hindered referral were higher (n=266, 50.7%) and lower (n=121, 23.1%), respectively, among the first ad result. While there was a significant difference for all ad results based on search strategy (P=0.04), we found no difference for the first ad result (P=0.25). As with both the webpage and map results, significant differences based on geography emerged (P=0.001), with the West North Central sub-region having the lowest proportion of searches facilitating referral (n=46, 25.0%) and the highest proportion hindering referral (36.4%; Table 4, Figure 3).

Table 4.

Proportion of ads that facilitated, did not facilitate, and hindered abortion self-referral

| Characteristic | Facilitated abortion self- referral |

Did not facilitate abortion self-referral |

Hindered abortion self- referral |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ads (n=2,027) | 697 (34.4) | 724 (35.7) | 606 (29.9) | |

| Search engine | <0.001 | |||

| A (n=853) | 293 (34.4) | 351 (41.2) | 209 (24.5) | |

| B (n=477) | 114 (23.9) | 278 (58.3) | 85 (17.8) | |

| C (n=697) | 290 (41.6) | 95 (13.6) | 312 (44.8) | |

| Search strategy | 0.04 | |||

| ”Abortion” and city (n=461) | 160 (34.7) | 161 (34.9) | 140 (30.4) | |

|

”Abortion clinic” and city

(n=721) |

275 (38.1) | 252 (35.0) | 194 (26.9) | |

|

”Where to get an abortion”

and city (n=845) |

262 (31.0) | 311 (36.8) | 272 (32.2) | |

| Subregion | 0.001 | |||

| New England (n=154) | 60 (39.0) | 41 (26.6) | 53 (34.4) | |

| Middle Atlantic (n=130) | 51 (39.2) | 46 (35.4) | 33 (25.4) | |

| South Atlantic (n=335) | 126 (37.6) | 101 (30.2) | 108 (32.2) | |

| East South Central (n=136) | 45 (33.1) | 51 (37.5) | 40 (29.4) | |

| West South Central (n=291) | 94 (32.3) | 122 (41.9) | 75 (25.8) | |

| East North Central (n=239) | 84 (35.2) | 70 (29.3) | 85 (35.6) | |

| West North Central (n=184) | 46 (25.0) | 71 (38.6) | 67 (36.4) | |

| Mountain (n=203) | 78 (38.4) | 77 (37.9) | 48 (23.7) | |

| Pacific (n=355) | 113 (31.8) | 145 (40.9) | 97 (27.3) | |

| Distance to abortion provider | 0.02 | |||

| <50 miles (n=1,632) | 584 (35.8) | 573 (35.1) | 475 (29.1) | |

| 50 -<100 miles (n=278) | 82 (29.5) | 112 (40.3) | 84 (30.2) | |

| ≥100 miles (n=117) | 31 (26.5) | 39 (33.3) | 47 (40.2) |

Figure 3.

The proportion of advertisements facilitating, hindering, and not facilitating referral stratified by anonymous search engine (Google, Bing, or Yahoo), search strategy (1: “abortion” and location; 2: “abortion clinic” and location; 3: “where to get an abortion” and location), and Census Bureau subregion, and distance to an abortion provider.

Distance to an abortion provider was significantly associated with the content of webpage, map, and ad results (all P≤0.02). In all cases, locations within 50 miles of an abortion provider had the largest proportion of results facilitating referral and the smallest proportion hindering referral, and locations ≥100 miles from an abortion provider had the smallest proportion of results facilitating referral and the largest proportion hindering referral. These findings were similar for the first webpage and map results (both P<0.001), while no difference was seen for the first ad result (P=0.22).

There were 1,274 (22.0%) webpage results, 574 (37.2%) map results, and 162 (8.0%) ad results that identified local independent abortion providers. Of these, 1,234 (96.9%) of the webpage results, 567 (98.8%) of the map results, and 159 (98.1%) of the ad results identified were freestanding clinics. Among the results identifying local independent abortion providers, no private physician offices were identified in maps or ads, and only 14 (1.1%) webpage results identified private physicians; hospital-based services were found in 26 (2.0%) webpage results, 7 (1.2%) map results, and 3 (1.9%) ads.

DISCUSSION

In our study, more search results facilitated referrals than hindered them. More than 50% of map and webpage searches facilitated referrals, while approximately one-third of ad results did so. The first search result was the most likely to lead to a referral to an abortion provider. For all types of searches, those conducted for cities in the West North Central region were the least likely to facilitate referral, with only approximately 27% of webpage results, 34% of map results, and 25% of ads directing the searcher to an abortion provider. The closer a city was to an abortion provider, the more likely that an appropriate referral was returned, demonstrating athat quality was higher in areas with greater abortion access.

The internet is frequently used to find information about abortion. In 2015, there were approximately 3.4 million Google searches for abortion clinics in the U.S.;13 adding other search engines would increase this number considerably. Individuals living in areas with multiple restrictions on abortion access, which tend to be areas with fewer abortion providers, are the most likely to use the internet to search for abortion.18 Such individuals are more likely to live farther from abortion clinics, as these restrictions have been associated with clinic closures.19 We found that searches in areas where the nearest abortion clinic was at least 100 miles away, which have recently been referred to as “abortion deserts,20 were the most likely to lead to inappropriate referrals; 27 U.S. cities, containing a total population in 2015 of over 3.3 million, are located within abortion deserts.20 Thus, people who are most likely to rely on the internet to locate abortion services are the least likely to access accurate information with which to locate an abortion provider. Additionally, because abortion providers tend to be concentrated in more urban areas, which were the focus of this study, these findings likely provide an overestimate of the quality of information available online for abortion self-referral for the country as a whole.

Many results in our searches led to either crisis pregnancy centers or anti-abortion websites regardless of search term or search engine. Prior research has shown that crisis pregnancy centers intend to dissuade individuals from choosing abortion; they generally do not provide referrals for abortion care and are affiliated with anti-abortion organizations.21 One study of the websites of crisis pregnancy centers found that 80% provided incorrect information about abortion.22 Another study reported that being unaware of a crisis pregnancy center’s intended purpose can lead to surprise and anger about their refusal to provide or even refer for abortion care.16 Additionally, crisis pregnancy centers spend significant sums of money to advertise on internet search engines.21 Although Google banned such ads paid for by religious organizations in 2008, a settlement was reached, and the ads are now allowed.23 Google does have a policy against “misleading content,”24 and in 2014, Google removed the ads of many crisis pregnancy centers that were deemed to have misleading content.25 Despite this, we found that anti-abortion websites and crisis pregnancy centers were prominently featured among ads on all three search engines.

Of note, our searches rarely identified hospital-based abortion providers or private physicians’ offices that provided abortions. Abortion clinics, which are defined as nonhospital facilities in which half or more of patient visits are for abortion services, regardless of annual caseload, make up 16% of facilities that provide abortions and provide 59% of abortions in the country.1 Non-specialized clinics, hospitals, and private physicians’ offices account for the majority of locations where abortions are available,1 but our findings suggest that an internet search would be unlikely to lead to these facilities.

While the strengths of our study include wide geographic coverage, the large number of searches, and the use of various search terms, our findings are limited by the complexities of search engines. We prevented detailed location data from being accessed by the search engine, as we conducted all searches from one city. Our results could have been different had our searches originated from the cities for which we were searching due to the use of location identification by the search engines. However, tests of searches within one city distant from the study location showed nearly identical results when searching within that city and when using an anonymized location at the study site. While use of a virtual private network would have further prevented our study location from being used in the search results, this was not feasible. Any individual who searches for abortion clinics may see results that differ from that of another individual based on past searches, demographics, location, and even whether the search occurred on a computer or a mobile device.26 However, because each search engine uses proprietary algorithms to rank websites for each search, the extent of this personalization is unknown. Our study is also limited by its cross-sectional nature; while the top webpage results are expected to remain relatively stable, changes in the rankings of websites, map results, and ads do occur, and thus the results of this study represent a single snapshot in time. Additionally, we did not quantify the number of inactive links among the search results, though we expect that few inactive links were returned on the first page of results; we would not expect the proportion of inactive links to differ between organizations that facilitate, do not facilitate, and hinder abortion referral. Finally, our search was limited to cities, and thus we were not able to characterize the quality of information available online for abortion self-referral in more rural areas.

Although many searches resulted in referrals to abortion providers, some led to anti-abortion websites and crisis pregnancy centers. These proportions differed by search location, type of search result, and distance to an abortion provider. Because ads that hindered abortion self-referral featured prominently in search results from all search engines, individuals who use the internet to locate abortion providers should be wary of information obtained through ads. Patients who use the internet to locate abortion services are at risk of encountering misinformation and of mistakenly seeking care at facilities that do not provide the care they seek. As such, it is an ethical responsibility5 and critically important for health care providers and staff to be able to provide appropriate referrals for abortion care.

Supplementary Material

Box 2. Description of how data were summarized for results that did not facilitate abortion referral.

Physician office that does not provide abortions

Non-local*, non-national abortion provider

Abortion provider located more than 50 miles from the city of interest

Non-medical website

Cafes, retailers, etc.

News article†

Online news sites

General directory†

Yelp, Yellow Pages

Other

Other results

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102), and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers.

Footnotes

Presented at the 2017 North American Forum on Family Planning in Atlanta, Georgia, October 13-15, 2017.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

For locations that did not have any abortion provider within 50 miles, the closest abortion provider regardless of distance would have been considered “local,” though in no case did the closest abortion provider appear in the search results

Only returned in ad results

Reference List

- 1.Jones RK, Jerman J. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2014. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49(1):17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drey EA, Foster DG, Jackson RA, Lee SJ, Cardenas LH, Darney PD. Risk factors associated with presenting for abortion in the second trimester. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):128–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebert LE, Fabiyi C, Hasselbacher LA, Starr K, Gilliam ML. Variation in pregnancy options counseling and referrals, and reported proximity to abortion services, among publicly funded family planning facilities. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48(2):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compliance with statutory program integrity requirements, 83 FR 25502 (June 1, 2018). Federal Register: The Daily Journal of the United States. 2018, [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodge LE, Haider S, Hacker MR. Using a simulated patient to assess referral for abortion services in the USA. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38(4):246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The limits of conscientious refusal in reproductive medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 385. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennis A, Manski R, Blanchard K. A qualitative exploration of low-income women’s experiences accessing abortion in Massachusetts. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25(5):463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French V, Anthony R, Souder C, Geistkemper C, Drey E, Steinauer J. Influence of clinician referral on Nebraska women’s decision-to-abortion time. Contraception. 2016;93(3):236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai S, Jones RK, Castle K. Estimating abortion provision and abortion referrals among United States obstetrician-gynecologists in private practice. Contraception. 2018;97(4):297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homaifar N, Freedman L, French V. “She’s on her own”: a thematic analysis of clinicians’ comments on abortion referral. Contraception. 2017;95(5):470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra. Supreme Court of the United States. No. 16–1140; 585 U.S, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connaway LS, Dickey TJ, Radford ML. “If it is too inconvenient I’m not going after it:” convenience as a critical factor in information-seeking behaviors. Library & Information Science Research. 2011;33(3):179–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pew Research Center. Internet/broadband fact sheet. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/internet-broadband Updated January 12, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2017.

- 14.Stephens-Davidowitz S The Return of the D.I.Y. Abortion. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/06/opinion/sunday/the-return-of-the-diy-abortion.html Updated March 5, 2016. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- 15.Pew Research Center. Health Online 2013. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013/ Updated January 15, 2013. Accessed September 29, 2017.

- 16.Foster AM, Wynn LL, Trussell J. Evidence of global demand for medication abortion information: an analysis of www.medicationabortion.com. Contraception. 2014;89(3):174–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Margo J, McCloskey L, Gupte G, Zurek M, Bhakta S, Feinberg E. Women’s pathways to abortion care in South Carolina: a qualitative study of obstacles and supports. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48(4):199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chitika . The value of Google result positioning. Retrieved from http://chitika.com/2013/06/07/the-value-of-google-result-positioning-2/ Accessed July 31, 2018.

- 19.Reis BY, Brownstein JS. Measuring the impact of health policies using Internet search patterns: the case of abortion. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:514. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerdts C, Fuentes L, Grossman D, et al. Impact of clinic closures on women obtaining abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):857–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cartwright AF, Karunaratne M, Barr-Walker J, Johns NE, Upadhyay UD. Identifying national availability of abortion care and distance from major US cities: systematic online search. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(5):e186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform—Minority Staff Special Investigations Division. False and Misleading Health Information Provided by Federally Funded Pregnancy Resource Centers. https://www.chsourcebook.com/articles/waxman2.pdf Accessed October 11, 2017.

- 23.Bryant AG, Narasimhan S, Bryant-Comstock K, Levi EE. Crisis pregnancy center websites: Information, misinformation and disinformation. Contraception. 2014;90(6):601–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clifford S Google in shift on ‘abortion’ as keyword. The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/22/technology/22google.html Updated September 22, 2008. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- 25.Google. Advertising Policies Help: Misrepresentation. https://support.google.com/adwordspolicy/answer/6020955?hl=en Accessed October 10, 2017.

- 26.Tsukayama H Google removes “deceptive” pregnancy center ads. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2014/04/28/naral-successfully-lobbies-google-to-take-down-deceptive-pregnancy-center-ads/?utm_term=.56303cac1341 Updated April 28, 2014. Accessed October 11, 2017.

- 27.British Broadcasting Corporation. How does Google work? Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/z8yc2p3 Accessed October 9, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.