Abstract

In vivo PET imaging of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor complex has been accomplished using radiolabeled benzodiazepine derivatives, but development of specific presynaptic radioligands targeting the neuronal membrane GABA transporter type 1 (GAT-1) has been less successful. The availability of new structure-activity studies of GAT-1 inhibitors and the introduction of a GAT-1 inhibitor (tiagabine, Gabatril®) into clinical use prompted us to reinvestigate the syntheses of PET ligands for this transporter. Initial synthesis and rodent PET studies of N-[11C]methylnipecotic acid confirmed the low brain uptake of that small and polar molecule. The common design approach to improve blood-brain barrier permeability of GAT-1 inhibitors is the attachment of a large lipophilic substituent. We selected an unsymmetrical bis-aromatic residue attached to the ring nitrogen by a vinyl ether spacer from a series recently reported by Wanner and coworkers. Nucleophilic aromatic substitution of an aryl chloride precursor with [18F]fluoride was used to prepare the desired candidate radiotracer (R,E/Z)-1-(2-((4-fluoro-2-(4-[18F]fluorobenzoyl)styryl)oxy)ethyl)piperidine-3-carboxylic acid ((R,E/Z)-[18F]10). PET studies in rat showed no brain uptake, which was not altered by pretreatment of animals with the P-glycoprotein inhibitor cyclosporine A, indicating efflux by Pgp was not responsible. Subsequent PET imaging studies of (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 in rhesus monkey brain showed very low brain uptake. Finally, to test if the free carboxylic acid group was the likely cause of poor brain uptake, PET studies were done using the ethyl ester derivative of (R,E/Z)-[18F]10. Rapid and significant monkey brain uptake of the ester was observed, followed by a slow washout over 90 minutes. The blood-brain barrier permeability of the ester supports a hypothesis that the free acid function limits brain uptake of nipecotic acid-based GAT-1 radioligands, and future radiotracer efforts should investigate the use of carboxylic acid bioisosteres.

Keywords: GABA, transporter, positron emission tomography, fluorine-18

Introduction

The amino acids g-aminobutyric acid (GABA (1), Figure 1) and glycine are the predominant inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitters in the mammalian central nervous system. Neurons presenting the biochemical features of GABA-ergic neurons are widespread throughout the CNS, comprising 20–30% of cortical neurons,1 and provide the inhibitory balance to excitatory glutamatergic neurons. Reflecting this, dysfunction of the GABA system has been implicated in numerous neurodevelopmental diseases, such as seizure disorders (e.g., epilepsy), and psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), RETT syndrome, depression, and anxiety disorders. Drugs that target the GABA system are widely prescribed (e.g., benzodiazepines, progabide, gabapentin, pregabalin) to manage these disorders.

Figure 1.

GABA (1), GAT-1 inhibitors and radiotracers (2–5) and [11C]PMP (6)

Despite the importance of the GABA-ergic system in health and disease, efforts to develop in vivo agents for positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging of specific sites on GABA-ergic neurons have been limited. Successful imaging agents have targeted the benzodiazepine binding site on the GABAA receptor complex.2 Changes in radioligand (e.g., [11C]flumazenil ([11C]FMZ)) binding to the benzodiazepine binding site are then used as surrogate markers of alterations in concentrations of GABAA receptors, but as those receptors are largely found in the post-synaptic membranes (and are subject to regulation by trafficking mechanisms3) the binding of radiolabeled benzodiazepines such as [11C]FMZ does not provide information on the concentration of presynaptic GABA-ergic neurons. Radioligand development efforts for other sites in the GABA system receptor, such as GABAB receptors or the chloride ion channel of GABAA receptor complexes have been less successful,4 and have not progressed to human studies.

The development of radiotracers intended as presynaptic neuronal markers has targeted neuronal membrane and vesicular neurotransmitter transporters, resulting in validated radiotracers for the neuronal membrane transporters (dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine and glycine) and vesicular transporters (monoamines and acetylcholine).5

To date there are no radiotracers for the neuronal membrane GABA transporters. Our prior efforts in the design and synthesis of radioligands for GABA transporters targeted fluorine-18 radiotracers based on the structure of CI-966 (2), and yielded a potential GAT-1 radioligand ((R,S)-1-[2-(4-[18F]fluorophenyl)(4-fluorophenyl)]-methoxyethyl]piperidine-3-carboxylic acid ([18F]3) (Figure 1).6 Although exhibiting low brain permeability, [18F]3 did have a heterogeneous in vivo brain distribution similar to that obtained using [3H]tiagabine in vitro and ex vivo.7,8 These early studies were encouraging, but the combination of (1) a still rudimentary understanding of the pharmacology and brain distribution of the GABA transporters, (2) a lack of published structure-activity studies for GAT-1 inhibitors, (3) concerns over potential adverse pharmacological effects of this family of GAT-1 inhibitors,9 and (4) difficult chemistry to obtain the high specific activities needed for human studies led us to cease further effort in development of GABA transporter inhibitor radioligands. Subsequent efforts by others in syntheses of radiolabeled GABA transporter inhibitors (GAT-1 and GAT-3) for imaging have also been unsuccessful.10

In the intervening 20 years, much has changed. The molecular biology and pharmacology of GABA transporters is better characterized, including proposed tertiary structures of potential binding sites for ligands.11 Advances in radiochemistry have provided routinely successful preparations of 11C- and 18F-labeled compounds at high specific activities (>1000 Ci/mmol). Structure-activity relationships of GAT inhibitors and their selectivity for the four forms of GAT (GAT-1, 2, 3 and 4) have been explored by multiple investigators,12 and GAT-1 is now recognized as being predominantly located on presynaptic neurons, with a minor population on astrocytes.13 Notably, there is a large concentration of GAT-1 in human cortex (3400 fmol/mg protein, or 340 nM),14 a concentration higher than many receptor sites that have been successfully imaged.15 Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the GAT-1 inhibitor tiagabine (Gabitril® (4), Figure 1) has been shown safe for use in humans,16 and was FDA approved for clinical use in 1997 as an adjunctive treatment for seizures. [3H]Tiagabine has also been used for in vitro binding studies in rat and human brain tissues,7,14 including recent post-mortem studies that demonstrate significant changes in GAT-1 in aging17 and schizophrenia.18 In succeeding years multiple additional molecular scaffolds have been investigated, but all share a consistent structural design, that of a large lipophilic group attached to the nitrogen in the ring of a small cyclic amino acid such as nipecotic acid (5) (Figure 1) or guvacine (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine-3-carboxylic acid). The added lipophilicity is considered necessary, as it is known that nipecotic acid does not cross the blood-brain barrier, likely due to its polar nature (cLogD7.4 = −2.3819) and zwitterionic character.

Despite these advances, there are still no PET (or SPECT) radiotracers known for imaging presynaptic GABA neuron densities in the clinic, and we have therefore revisited the development of radioligands for GABA transporters to allow studies of GABA-ergic innervation in human diseases. Herein we report the design, synthesis and evaluation of a potential new PET radiotracer for the GAT-1 transporter.

Results and Discussion

Our re-investigation of potential GAT-1 imaging agents began with an examination of the in vivo properties of the simple N-[11C]methylated nipecotic acid ([11C]9, clogD7.4 = −1.62), which was easily prepared by N-[11C]methylation of racemic ethyl nipecotate (7) followed by immediate ester hydrolysis using 5M LiOH. PET imaging studies in rats showed no brain uptake of [11C]9 (see Supporting Information, Figure S13), which was not completely unexpected and confirmed the need for larger lipophilic N-methyl substituents. As the presence of the free carboxylic acid likely was the reason for poor blood-brain-barrier (BBB) permeability of [11C]9, we next isolated and purified the intermediate N-[11C]methylnipecotic acid ethyl ester ([11C]8, cLogD7.4 = −0.27). Surprisingly, that ester also demonstrated no permeability into the rat brain (see Supporting Information, Figure S13). That result was unexpected, given that compound [11C]8 is identical in molecular weight and functional groups (N-methylpiperidine and carboxylic acid ester) to the radiotracer N-[11C]methylpiperidin-4-yl propionate ([11C]PMP ([11C]6, Figure 1), clogD7.4 = −0.81) that has been extensively utilized for PET imaging of acetylcholinesterase in rat, primate and human brain. The poor BBB permeability of [11C]8 remains unexplained.

We concluded from these initial studies that N-methylnipecotic acid derivatives were not sufficiently drug-like to penetrate the CNS (Table 1), and so turned our attention to developing a radiotracer that was based upon nipecotic acid but with improved drug-like properties. We chose to avoid further derivatives of CI-966, given its known toxicity and the poor brain uptake of [18F]3.6,9 Therefore, we were attracted by a new series of GAT-1 inhibitors reported by Wanner and colleagues in 2013.20 These compounds consisted of a nipecotic acid core and an unsymmetrical bis-aromatic residue attached to the ring nitrogen by a vinyl ether spacer, and we selected compound 10 as the lead because of its potency in a functional [3H]GABA uptake assay (pIC50 = 5.73±0.14 ((E)-10) and 6.47±0.08 ((Z)-10)) and >100-fold selectivity for GAT-1 over GAT-2, -3 and -4.20 The functional GABA uptake assay is commonly used to screen GAT-1 inhibitors, but has been demonstrated to consistently and significantly underestimate the binding affinities (Ki or Kd values).21 For example, tiagabine exhibits a pIC50 = 6.88 (or 132 nM) for inhibiting [3H]GABA uptake, but binding assays with [3H]tiagbine gave a Kd = 16 nM.14 Extending this relationship to lead compound 10 suggests that a pIC50 of 6.47 (340 nM) would equate with an in vitro binding affinity of approximately 41 nM. This estimated in vitro affinity was then used to project a potential in vivo cortical binding potential (BP) for compound 10, where BP = Bmax/Kd, yielding a value of 340 nM/41 nM = 8. Such a value is higher than the often-proposed need for a BP > 5 to achieve successful in vivo human imaging of specific brain binding for new radiotracers,22 and together with the medicinal chemistry properties comparable to successful CNS drugs (Table 1)23 and amenability for labeling with both carbon-11 and fluorine-18 made compound 10 attractive from a radiotracer development perspective.

Table 1.

Lead GAT-1 Inhibitor (10) for radiolabeling

| Property | Typical value for successful CNS drugs23 |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| clogp | 1.5–2.7 | −1.65 | 1.81 |

| clogD7.4 | 0–3 | −1.62 | 2.56 |

| tPSA | 60–90 | 40.54 Å | 66.84 Å |

| molecular weight | ≤400–600 g/mol | 143 g/mol | 415 g/mol |

| heteroatoms (O + N) | ≤5 | 3 | 5 |

| Acidic pKa | >4 | 3.22 | 3.27 |

| Basic pKa | <10 | 9.60 | 7.76 |

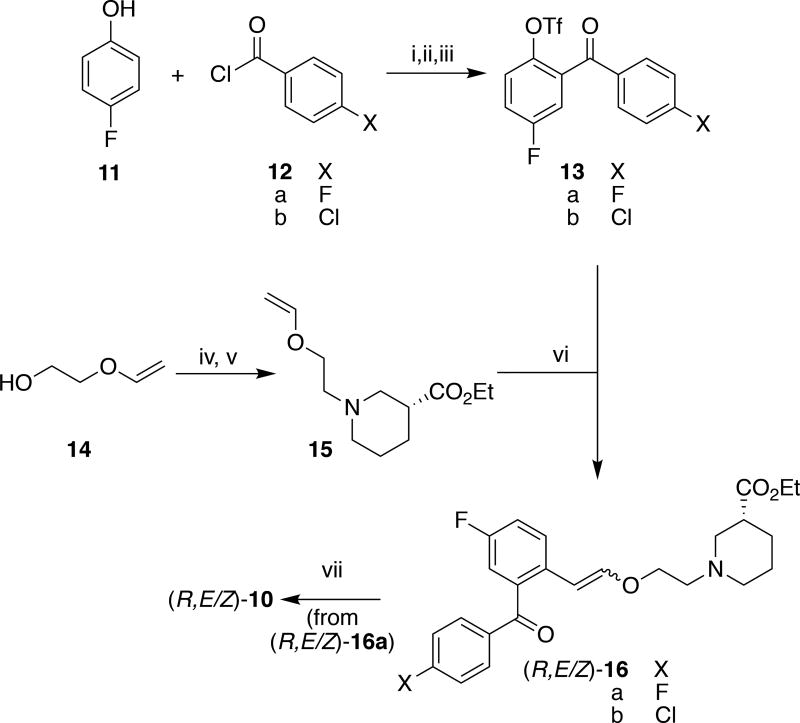

We elected to prepare the fluorine-18 labeled version of the lead compound ((R,E/Z)-[18F]10) from the corresponding chlorinated precursor (R,E/Z)-16b using nucleophilic aromatic substitution with [18F]fluoride. The synthetic pathway to access unlabeled reference standard (R,E/Z)-10 and chloro-precursor (R,E/Z)-16b was the same (Scheme 2). Initially 4-fluorophenol 11 was coupled with the corresponding acyl chloride 12 to provide the ester. Treating the intermediate ester with aluminum trichloride promoted a Fries rearrangement to give an ortho-acylated phenol, and the phenol was converted to triflate derivative 13. Concomitantly, 2-(vinyloxy)ethan-1-ol 14 was tosylated and used to alkylate nipecotate (R)-7 and generate (R)-15. A Pd-mediated Heck cross-coupling of aryl triflate 13 and nipecotic acid derivative (R)-15 yielded ester derivative (R)-16 as a mixture of the E and Z products.24 The chlorinated ester is the desired precursor for radiolabeling ((R,E/Z)-16b), while saponification of the fluorinated ester ((R,E/Z)-16a) generated unlabeled reference standard (R,E/Z)-10.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of precursor (R,E/Z)-16b and reference standard (R,E/Z)-10. Reagents and conditions: i) Et3N, CH2Cl2, reflux, 1 h (X = F, 77% X=Cl, 83%); ii) AlCl3, 200 °C, 30–40 min (X= F, 54%, X=Cl, 59%); iii) Tf2O, 2,6-lutidine, CH2Cl2, 0 °C – rt, 36 h (X= F, 59% X=Cl, 61%); iv) TsCl, Et3N, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 48 h (65%); v) Et3N, (R)-7, rt, 16 h (50%); vi) Pd(OAc)2, Et3N, PPh3, DMF, 80 °C, 48 h (X= F, 20%, X=Cl, 48%); vii) 2M LiOH, EtOH, 0 °C – rt, 0.5 h (X = F, 46%).

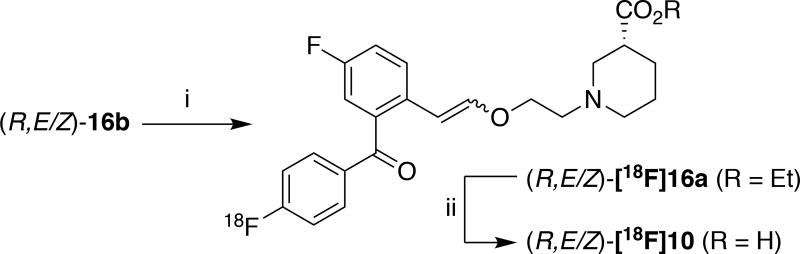

Synthesis of the fluorine-18 labeled compound ((R,E/Z)-[18F]10, clogD7.4 = 2.56) was accomplished by subjecting chloro-precursor (R,E/Z)-16b to standard SNAr conditions ([18F]KF and kryptofix-2.2.2 (K2.2.2) in DMF, 130 °C, 30 min) and saponification of the ester with LiOH (Scheme 3). Purification (semi-preparative HPLC) and reformulation (C18 cartridge) provided 9.3±3.3 mCi of (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 (1% non-corrected RCY, 100% radiochemical purity and specific activity = 1702 Ci/mmol, n = 4; see Supporting Information for full details of the radiosynthesis).

Scheme 3.

Radiosynthesis of (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 and (R,E/Z)-[18F]16a. Reagents and conditions: i) [18F]KF, K2.2.2, DMF, 130 °C, 30 min; ii) LiOH, 100 °C, 15 min ((R,E/Z)-[18F]10 and (R,E/Z)-[18F]16a were both isolated in 1% non-corrected RCY).

PET imaging studies using (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 were first conducted in rodents (Figure 2A). To our surprise however, there was very little brain uptake of (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 in the rat brain. To test if the lack of brain uptake was due to the actions of P-glycoprotein (Pgp), an efflux transporter at the blood-brain barrier,25 we repeated imaging of a rat following pre-treatment with 50 mg/kg cyclosporine A, as we have done previously for other radiotracers.25b However, this had no effect on brain uptake of (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 (Figure 2B). Finally, to test if the BBB impermeability was due to the free carboxylic acid functionality, we isolated and purified the intermediate ester ((R,E/Z)-[18F]16a, clogD7.4 = 4.11) but PET studies again showed no brain uptake (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Baseline rodent imaging with (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 (A), imaging of rodents pre-treated with 50 mg/kg cyclosporine A 60 min prior to injection of (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 (B), and baseline rodent imaging with (R,E/Z)-[18F]16A (C). Images are summed sagittal images 0–90 min post-injection of the radiotracer.

With the hypothesis that (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 possesses properties consistent with BBB permeability (Table 1), the lack of brain uptake of both the ester and the free carboxylic acid into the rat brain was unexpected. As there is always the possibility of species differences in distribution and metabolism of drugs and radiotracers, we undertook evaluation of imaging studies with (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 and (R,E/Z)-[18F]16a in rhesus monkey brain. While there were some discernible points of retention of (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 in the monkey brain (Figure 3A), the levels were deemed too low for (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 to be useful for imaging GAT-1 activity in the CNS. In contrast to the result in rats, administration of the ester (R,E/Z)-[18F]16a gave significant brain uptake of radioactivity in cortex, thalamus, striatum and cerebellum (Figure 3B, 3C). The species differences between rodents and primates could be due to differences in esterase expression, as the hydrolysis of certain esters is known to be much faster in rat than monkey.26 Although (R,E/Z)-[18F]16a clearly enters the brain, this uptake cannot be assumed to correspond to specific binding to GAT-1, as it has been shown in a number of studies into GABA and related compounds that a free acid is essential for activity and that esters are not active.27 Moreover, even if ester [18F]16a were to have affinity for GAT-1 or was behaving as a pro-drug and being hydrolyzed in the brain to acid [18F]10, we anticipated that the inability to determine whether the PET images were due to ester [18F]16a or acid [18F]10 would thwart any attempts at quantitative analysis.

Figure 3.

Baseline nonhuman primate imaging with (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 (A), (R,E/Z)-[18F]16a (B) and regional time–radioactivity curves for (R,E/Z)-[18F]16a (C). PET images are summed sagittal images 0–90 min post-injection of the radiotracer.

Our results of low brain uptake of (R,E/Z)-[18F]10 are consistent with those obtained for [18F]3 and [123I]iodotiagabine, previously tested as GAT-1 radioligands.6,28 Together, the radiotracers evaluated to date span a range of clogD7.4 values (−1.62 – +4.11) and do not appear to be Pgp substrates. A common component of all of them is the nipecotic acid moiety, suggesting that the free carboxylic acid functionality limits BBB permeability: however, a carboxylic acid group in a molecule does not disqualify it from crossing the BBB and entering the CNS, as exemplified by the radiotracer [11C]bexarotene (clogD7.4 = 3.32) that has been used successfully for PET imaging of retinoid X receptors.29 More likely, the difficulty with using nipecotic acid derivatives as imaging agents lies in the ability of such compounds to form highly polar zwitterions.

The development of GAT-1 imaging agents thus remains unsuccessful, and may present different challenges than the requirements for therapeutic drug applications. Tiagabine may in fact achieve low brain uptake, which would be consistent with its pharmacology in rodents30 and need for careful dosing in human subjects including the requirement for an extensive titration period.31 Whereas, low brain uptake of a therapeutic drug such as tiagabine can be countered by administering repeated doses of the drug over several weeks to build up brain concentrations until the desired efficacy is achieved, for radiotracers used in PET or SPECT rapid brain uptake at sufficient levels must be achieved to allow external imaging and quantification. This apparent mismatch between the pharmacokinetic properties of GAT-1 inhibitors such as tiagabine and CI-966 and the requirements for an in vivo imaging radiotracer offers a plausible explanation for why our efforts to image GAT-1 have been unsuccessful to date, but also points to a possible solution: carboxylic acid bioisosterism. If the carboxylic acid function is necessary for high affinity binding to the GAT-1, but limits BBB permeability, then the replacement by an alternative functional group that mimics the size, volume, electronic and physicochemical properties of the carboxylic acid might be considered. Fortunately for our purposes, many bioisosteres of the carboxylic acid group have been developed,32 and there is precedent for applying them to GABA and its analogs.33,34 Our efforts to design 2nd generation GAT-1 PET radiotracers containing carboxylic acid bioisosteres are ongoing and will be the subject of a future report.

Conclusions

The attachment of a large lipophilic substituent to a small cyclic amino acid such as nipecotic acid remains the only successful design strategy for high affinity GAT-1 inhibitors. This has resulted in a useful clinical GAT-1 inhibitor (tiagabine, Gabatril®); unfortunately, as demonstrated by the latest fluorine-18 labeled radioligand reported here and consistent with prior efforts, such molecules show very low brain uptake and are not useful for in vivo imaging. Converting the free acid function to an ester resulted in good uptake into the rhesus monkey brain, supporting that the acid function may be largely responsible for the blood-brain barrier impermeability, possibly due to formation of a zwitterionic species. As the acid group is necessary for high affinity binding it cannot be simply removed or esterified, and future efforts in GAT-1 radiotracer design will investigate carboxylic acid bioisosteres in an attempt to improve brain uptake.

Methods

Details of experimental procedures as well as associated analytical data can be found in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Radiosynthesis of [11C]8 and [11C]9. Reagents and Conditions: i) [11C]MeOTf, DMF, room temperature, 3 min; ii) 5M LiOH, 100 °C, 5 min ([11C]8 was isolated in 2% non-corrected radiochemical yield (RCY) from 7; [11C]9 was isolated in 4% non-corrected RCY from 7).

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funding from the National Institutes of Health (R21NS086758) and the University of Michigan (Rackham Pre-doctoral Fellowship and College of Pharmacy) is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- CNS

central nervous system

- FMZ

flumazenil

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GAT-1

GABA Transporter 1

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- K2.2.2

kryptofix-2.2.2

- PET

positron emission tomography

- Pgp

P-glycoprotein transporter

- RCY

radiochemical yield

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Conti F, Melone M, De Biasi S, Minelli A, Brecha NC, Ducati A. Neuronal and glial localization of GAT-1, a high affinity γ-aminobutyric acid plasma membrane transporter in human cerebral cortex: with a note on its distribution in monkey cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;396:51–63. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980622)396:1<51::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson JD, Halldin C. PET radioligands targeting the brain GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor complex. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 2013;56:196–206. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vithlani M, Terunuma M, Moss SJ. The dynamic modulation of GABAA receptor trafficking and its role in regulating the plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Physiol. Rev. 2011;91:1009–1022. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Naik R, Valentine H, Dannals RF, Wong DF, Horti AG. Synthesis and Evaluation of a New 18F-Labeled Radiotracer for Studying the GABAB Receptor in the Mouse Brain. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018 doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Snyder SE, Kume A, Jung Y-W, Connor SE, Sherman PS, Albin RL, Wieland DM, Kilbourn MR. Synthesis of carbon-11, fluorine-18, and iodine-125-labeled GABAA-gated chloride ion channel blockers: substituted 5-tert-butyl-2-phenyl-1,3-dithianes and dithiane oxides. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:2663–2671. doi: 10.1021/jm00014a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li X, Jung Y-W, Snyder S, Blair J, Sherman PS, Desmond TD, Frey KA, Kilbourn MR. 5-tert-butyl-2-(4’-[18F]fluoropropynylphenyl)-1,3-dithiane oxides: Potential new GABAA receptor radioligands. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2008;35:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For a review of PET tracers for transporter imaging, see: Kilbourn MR. Small Molecule PET Tracers for Transporter Imaging. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2017;47:536–552. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2017.05.005.

- 6.Kilbourn MR, Pavia MR, Gregor VE. Synthesis of fluorine-18 labelled GABA uptake inhibitors. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1990;41:823–828. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(90)90059-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braestrup C, Nielsen EB, Sonnewald U, Knutsen LJ, Andersen KE, Jansen JA, Frederiksen K, Andersen PH, Mortensen A, Suzdak PD. (R)-N-[4,4-(bis(3-methyl-2-thienyl)but-3-en-1-yl]nipecotic acid binds with high affinity to the brain γ-aminobutyric acid uptake carrier. J. Neurochem. 54:639–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzdak PD, Swedberg MDB, Andersen KE, Knutsen LJ, Braestrup C. In vivo labeling of the central GABA uptake carrier with 3H-tiagabine. Life Sci. 51:1857–1868. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90037-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radulovic L, Woolf T, Bjorge S, Taylor C, Reily M, Bockbrader H, Chang T. Identification of a pyridinium metabolite in human urine following a single oral dose of 1-[2[[bis[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]methoxy]ethyl]-1,2,5,6-tetrahydro-3-pyridinecarboxylic acid, a γ-aminobutyric acid uptake inhibitor. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1993;6:341–344. doi: 10.1021/tx00033a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Vandersteene I, Slegers G. Synthesis of (R)-1-(4-[11C]-p-methoxyphenyl-4-phenyl-3-butenyl)-3-piperidinecarboxylic acid for Positron Emission Tomography of the GABA uptake carrier. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1996;47:201–205. [Google Scholar]; b) Schirrmacher R, Hamkens W, Piel M, Schmitt U, Lüddens H, Hiemke C, Rösch F. Radiosynthesis of (±)-(2-((4-(2-[18F]fluoroethoxy) phenyl)bis(4-methoxy-phenyl)methoxy)ethylpiperidine-3-carboxylic acid: a potential GAT-3 PET ligand to study GABAergic neuro-transmission in vivo 2001 [Google Scholar]; c) Schijns O, van Kroonenburgh M, Beekman F, Verbeek J, Herscheid J, Rijkers K, Visser-Vandewalle V, Hoogland G. Development and characterization of [123I]iodotiagabine for in vivo GABA-transporter imaging. Nucl. Med. Comm. 2013;34:175–9. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32835bbbd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Bennet ER, Kanner BI. The membrane topology of GAT-1, a (Na+ + Cl−)-coupled γ-aminobutyric acid transporter from rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:1203–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Clausen RP, Frølund B, Larsson OM, Schousboe A, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, White HS. A novel selective gamma-aminobutyric acid transport inhibitor demonstrates a functional role for GABA transporter subtype GAT2/BGT-1 in the CNS. Neurochem Int. 2006;48:637–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Madsen KK, White HS, Schousboe A. Neuronal and non-neuronal GABA transporters as targets for antiepileptic drugs. Pharm. Ther. 2010;125:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Skovstrup S, Taboureau O, Brauner-Osborne H, Jorgensten FS. Homology modeling of the GABA transporter and analysis of tiagabine binding. ChemMedChem. 2010;5:986–1000. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Skovstrup S, David L, Taboureau O, Jorgensten FS. A Steered molecular dynamics study of the binding and translocation processes in the GABA transporter. PLOS One. 2012;7:e39360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Knutsen LJS, Andersen KE, Lau J, Lundt BF, Henry RF, Morton HE, Naerum L, Petersen H, Stephensen H, Suzdak PD, Swedberg MD, Thomsen C, Sørensen PO. Synthesis of novel GABA uptake inibitors. 3. Diaryloxime and diarylvinyl ether derivatives of nipecotic acid and guavacine as anticonvulsant agents. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:3447–3462. doi: 10.1021/jm981027k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zheng J, Wen R, Luo X, Lin G, Zhang J, Xu L, Guo L, Jiang H. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of the N-diarylalkenyl-piperidinecarboxylic acid derivatives as GABA uptake inhibitors (I) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:225–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Pizzi D, Leslie CP, Di Fabio R, Seri C, Bernasconi G, Squaglia M, Carnevale G, Falchi A, Greco E, Mangiarini L, Negri M. Stereospecific synthesis and structure-activity relationships of unsymmetrical 4,4,-diphenylbut-3-enyl derivatives of nipecotic acid as GAT-1 inhibitors. Biorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:602–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madsen KK, White HS, Schousboe A. Neuronal and non-neuronal GABA transporters as targets for antiepileptic drugs. Pharm. Ther. 2010;125:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson IS, Allard P, Marcusson J. [3H]Tiagabine binding to GABA uptake sites in human brain. Brain Res. 1999;851:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zilles K, Palomero-Gallagher N. Multiple transmitter receptors in regions and layers of the human cerebral cortex. Front. Neuroanat. 2017;11:78. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2017.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leppik IE, Gram L, Deaton R, Sommerville KW. Safety of tiagabine: summary of 53 trials. Epilepsy Res. 1999;33:235–246. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundman-Eriksson I, Allard P. Age-correlated decline in [3H]tiagabine binding to GAT-1 in human frontal cortex. Aging Clin. Exper. Res. 2006;18:257–260. doi: 10.1007/BF03324657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundman-Eriksson I, Blennow K, Davidson P, Dandenell A-K, Marcusson J. Increased [3H]tiagabine binding to GAT-1 in the cingulated cortex in schzophrenia. Neuropsychobiology. 2002;45:7–11. doi: 10.1159/000048666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ADMET Predictor™ 8.1 was utilized to predict logD values with the S+logD method, which is the octanol-water distribution coefficient (log D) calculated from S+pKa and S+logP.

- 20.Quandt G, Hofner G, Wanner KT. Synthesis and evaluation of N-substituted nipecotic acid derivatives with an unsymmetrical bis-aromatic residue attached to a vinyl ether spacer as potential GABA uptake inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:3363–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kern FT, Wanner KT. generation and screening of oxime libraries addressing the neuronal GABA transporter GAT1. ChemMedChem. 2014;10:396–410. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van de Bittner GC, Ricq EL, Hooker JM. A Philosophy for CNS Radiotracer Design. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:3127–3134. doi: 10.1021/ar500233s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pajouhesh H, Lenz GR. Medicinal chemical properties of successful central nervous system drugs. NeuroRx. 2005;2:541–553. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.4.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The stereoisomers are stable and monitoring by NMR shows they do not interconvert. Preliminary efforts to separate the isomers proved challenging, but were not optimized given the lack of promising imaging data.

- 25.a) Sarkadi B, Homolya L, Szakaćs G, Vaŕadi A. Human multidrug resistance ABCB and ABCG transporters: Participation in a chemoimmunity defense system. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:1179–1236. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shao X, Carpenter GM, Desmond TJ, Sherman P, Quesada CA, Fawaz M, Brooks AF, Kilbourn MR, Albin RL, Frey KA, Scott PJH. Evaluation of [11C]N-methyl lansoprazole as a radiopharmaceutical for PET imaging of tau neurofibrillary tangles. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:936–941. doi: 10.1021/ml300216t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahar FG, Ohura K, Ogihara T, Imai T. Species difference of esterase expression and hydrolase activity in plasma. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012;101:3979–3988. doi: 10.1002/jps.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.a) Crider AM, Wood JD, Tschappat KD, Hinko CN, Seibert K. γ-Aminobutyric acid uptake inhibition and anticonvulsant activity of nipecotic acid esters. J. Pharm. Sci. 1984;73:1612–6. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600731132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Falch E, Meldrum BS, Krogsgaard-Larsen P. GABA uptake inhibitors. Synthesis and effects on audiogenic seizures of ester prodrugs of nipecotic acid, guvacine and cis-4-hydroxynipecotic acid. Drug Des. Deliv. 1987;2:9–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gokhale R, Crider AM, Gupte R, Wood JD. 1990 Hydrolysis of Nipecotic Acid Phenyl Esters. J. Pharm. Sci. 79:63–65. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600790115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; D) Bonina FP, Arenare L, Palagiano F, Saija A, Nava F, Trombetta D, de Caprariis P. Synthesis, stability, and pharmacological evaluation of nipecotic acid prodrugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999;88:561–567. doi: 10.1021/js980302n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schijns O, van Kroonenburgh M, Beekman F, Verbeek J, Herscheid J, Rijkers K, Visser-Vandewalle V, Hoogland G. Development and characterization of [123I]iodotiagabine for in-vivo GABA-transporter imaging. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2013;34:175–9. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32835bbbd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotstein BH, Placzek MS, Krishnan HS, Pekošak A, Collier TL, Wang C, Liang SH, Burstein ES, Hooker JM, Vasdev N. Preclinical PET Neuroimaging of [11C]Bexarotene. Mol. Imaging. 2016;15:1–5. doi: 10.1177/1536012116663054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.a) Wang X, Ratnaraj N, Patsalos PN. The pharmacokinetic inter-relationship of tiagabine in blood, cerebrospinal fluid and brain extracellular fluid (frontal cortex and hippocampus) Seizure. 2004;13:574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Suzdak PD, Jansen JA. A review of the preclinical pharmacology of tiagabine: a potent and selective anticonvulsant GABA uptake inhibitor. Epilepsia. 1995;36:612–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. [accessed 24-Mar-2018];Gabitril® (tiagabine hydrochloride) package insert. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020646s016lbl.pdf.

- 32.Lassalas P, Gay B, Lasfargeas C, James MJ, Tran V, Vijayendran KG, Brunden KR, Kozlowski MC, Thomas CJ, Smith AB, III, Huryn DM, Ballatore C. Structure Property Relationships of Carboxylic Acid Isosteres. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:3183–3203. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krehan D, Frølund B, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Kehler J, Johnston GA, Chebib M. Phosphinic, phosphonic and seleninic acid bioisosteres of isonipecotic acid as novel and selective GABAC receptor antagonists. Neurochem. Int. 2003;42:561–565. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen KE, Sørensen JL, Huusfeldt PO, Knutsen LJ, Lau J, Lundt BF, Petersen H, Suzdak PD, Swedberg MD. Synthesis of novel GABA uptake inhibitors. 4. Bioisosteric transformation and successive optimization of known GABA uptake inhibitors leading to a series of potent anticonvulsant drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:4281–4291. doi: 10.1021/jm980492e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.