Abstract

Background

Slow participant recruitment impedes Alzheimer’s disease research progress. While research suggests that direct involvement with potential participants supports enrollment, strategies for how to best engage potential participants are still unclear.

Purpose

This study explores whether community health fair (HF) attendees who engage in a brief cognitive screen (BCS) are more likely to enroll in research than attendees who do not complete a BCS. Subjects: 483 HF attendees.

Methods

Attendees were tracked for a one-year period to ascertain research involvement.

Results

364 attendees expressed interest in research and 126 completed a BCS. Over the follow-up period, 21 individuals prescreened as eligible and 19 enrolled in an investigational study. Among all HF attendees, BCS completers had a 2.5 fold increase in subsequently prescreening as eligible as compared to non-BCS completers. However, when limited only to participants who stated an interest in research, this difference was no longer significant.

Conclusion

Completing a BCS at a community event may be an indicator of future research engagement, but for those already interested in participation, the BCS may be a poor indicator of future involvement. The BCS may also reduce anxiety and stigma around memory evaluation, which may translate into research engagement in the future.

Keywords: Research Engagement, Brief Cognitive Screen, Recruitment, Community Outreach

Introduction

Expeditiously evaluating interventions aimed at the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is imperative. AD has significant economic costs for the individual, their family, and the healthcare system, as well as implications for the quality of life of the affected individual and their loved ones. Over five-million Americans are living with AD and that number is projected to more than double by 2050 if a disease modifying therapy is not developed1.

Slow participant recruitment remains a major obstacle in evaluating potential disease modifying AD interventions. There is a dearth of systematic examinations of real-world recruitment strategies2,3. Prior investigations have demonstrated that directly interacting with potential participants facilitates study enrollment among older adults4, including engagement in AD research5,6. Carr and colleagues demonstrated that a community outreach event yielded greater enrollment than an event focused on educating local practitioners on the value of patient referrals to research5. However, it remains unclear how best to engage potential participants at community events to maximize the likelihood of future research engagement.

The present study contributes to our understanding of practical solutions to the problem of research participant recruitment through an examination of voluntary brief cognitive screening (BCS) at a community outreach event and subsequent interventional research enrollment during a one-year follow-up period. This study tests whether community health fair (HF) attendees who engage in the BCS are more likely to enroll in research than attendees who do not engage in BCS. We hypothesized that HF attendees who voluntarily engaged in BCS would be more likely to enroll in an AD investigational study than those who do not engage in BCS. As an exploratory hypothesis, we hypothesized that participants who engage in BCS will get involved in research faster (i.e., in less time following HF) than those who get involved but do not engage in BCS.

Methods

Procedures

Event

The HF was held in the spring of 2016. The public was invited to attend using local online, print, and radio advertisements; a two-minute expose on daytime local news broadcast; and via mention in a newsletter distributed to active research participants and other interested parties. The HF featured 17 interactive exhibitors (community businesses). Examples include a boxing club with a Parkinson’s disease program and the opportunity to try on boxing gloves; a local pharmacy with demonstrations of electronic medication boxes; and a stroke care network with opportunities to take blood pressure and discuss stroke risk. A locally renowned chef catered a brain-healthy, vegetarian lunch. BCS were administered to interested attendees in a one-on-one format. The HF included three information sessions: [a] the brain health benefits of exercise, [b] how music can promote successful aging, and [c] the value and process of early detection of cognitive changes. Attendance was free and no pre-event registration was required. The event hours were 10AM-2PM; some attendees came for the whole event, others only for segments. The event cost was approximately $5,000. Staff time is not included in this estimate because outreach is a regular part of staff responsibilities and therefore not considered an additional cost.

On-Site Event Registration

Immediately inside the HF entrances attendees completed registration cards. Fields on the cards included name, address, telephone, email, age, sex, and a check box to indicate whether or not the registrant wished to be contacted for research participation opportunities. Research interest was defined as an individual endorsing on the registration card that he or she wished to be contacted about research opportunities. Individuals could skip any fields they did not wish to complete. However, registration forms were subsequently used to identify raffle prize winners and so the majority of attendees opted to provide at least their name.

Brief Cognitive Screens

The HF setting provided separate rooms where attendees could register to be administered BCS. Attendees seeking a BCS completed a registration form identical to that described previously. BCS registration personnel guided attendees to an administration area where a BCS administrator was available. BCS administrators were either staff trained in administration or graduate students who received training by a staff neuropsychologist.

The BCS consisted of the four-word Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)7 with a modified distraction period which included identification of five overlapping figures8 and the Tapping A’s portion of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment9. The distraction period was modified prior to the HF after receiving feedback that the MIS alone seemed overly simplistic and unfulfilling. Upon completion of the BCS all examinees were given a folder containing educational and informational materials about research. BCS administrators indicated to all BCS participants that they should consult their primary care provider if they were experiencing memory or thinking problems. Additionally, a card was given to individuals who scored below a 5 out of 8 on the MIS recall, indicating that the BCS showed possible trouble with memory and thinking and suggesting they follow up with their primary care provider. Upon completion of the BCS all examinees were offered the opportunity to speak privately with SBCOA personnel about research participation.

Follow-up

To determine research participation outcomes of HF attendance and BCS engagement, we reviewed contacts during the following year with HF attendees who indicated research interest at HF registration. Contact information of attendees who wished to be contacted for research participation opportunities was added to the existing recruitment contact database (RCD). To track HF attendance, another database (i.e., separate of the RCD) was created for all registration information (i.e., every HF registration card), as was a separate database containing the BCS registration data to track BCS participation. After interacting with HF attendees interested in research, recruitment specialists added a dated note in the RCD describing the interactions and indicating what follow-up contact was needed. Interactions are defined as conversation via telephone, email exchange, or face-to-face meetings.

Attendees declining to provide contact information or indicating they were uninterested in research at the HF registration were neither added to the RCD nor contacted. Those wishing to receive research information but who were age-ineligible for studies enrolling at the time of the HF were sent a letter indicating such, thanking them for their interest and attendance, and stating that they would be contacted if age-eligible for future studies. These individuals were added to the RCD, but no further interactions were initiated by recruitment specialists until the individuals became age-eligible or new studies with different criteria began enrollment.

HF attendees who were already participating in an investigational research study at the time of the HF or who had already pre-screened as eligible and been put in contact with a study coordinator were mailed a letter thanking them for their attendance. Attendees who had been determined to be ineligible for studies enrolling at the time of the HF were also mailed the thank you letter (these individuals could have been contacted later in the follow-up period if new studies with different exclusionary criteria began enrollment). All other attendees expressing research interest were mailed a HF follow-up packet containing a letter thanking them for their attendance as well as flyers for actively-recruiting studies. Within three weeks after the HF, at least one phone call was made to all individuals who were mailed a follow-up packet. If the phone call was unanswered, voicemail messages were left when possible. If no phone number was provided or calls went unanswered, emails were sent when an email address was available.

Recruitment specialists described study opportunities and answered questions for those individuals who expressed further interest. Recruitment specialists helped potential participants identify which study would be the best fit. Based on the chosen study, recruitment specialists administered a brief 10- to 15-minute pre-screen, generally via telephone, to confirm basic eligibility and identify common exclusionary criteria. If no exclusionary criteria were evident and the individual was still interested in participating, recruitment specialists provided the individual’s contact info to the study coordinator of the chosen study. The date on which this occurred was recorded in the RCD. Recruitment specialists then tracked the date of initial study screening and recorded it in the RCD. If an individual met exclusionary criteria for one study during the pre-screen, recruitment specialists discussed other research participation opportunities to determine interest and potential eligibility.

After the 356-day follow-up period, the entries of 2016 HF registrants were extracted from the RCD. The tertiary HF registration database was accessed to obtain the count of registrants as well as age and sex. The tertiary BCS registration database was accessed only to determine which HF registrants completed a BCS. The de-identified RCD notes for each individual who endorsed future contact at registration were reviewed by J.M.B., naïve to the content of the RCD, and then by S.H.B., who manages the RCD.

Studies Enrolling in Follow-Up

Fourteen interventional studies were actively enrolling at some point during the follow-up period (See Table, Supplementary Digital Content 1). Studies varied in terms of the target population (normal, mild cognitive impairment, or AD) the target of investigation (investigational medication or lifestyle intervention), and the procedures involved (magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), lumbar puncture, etc.). Consistent with general recruitment practices at the site, recruitment efforts were not study specific; rather multiple research studies were considered for individuals interested in participation to identify options that would be a good fit.

Variables

An integral time-to-coordinator variable was computed as the number of days between the HF and recruitment specialists transferring contact of an attendee to a study coordinator. We selected time-to-coordinator as opposed to time to enrollment, because once in contact with coordinators, prospective participants are subject to constraints beyond the control of recruiters that may delay time to enrollment (e.g., including availability of clinicians and MRI time slots). Classification, or class, was a five-level nominal variable that is described in-depth below.

Classification

Outcomes of research interest and follow-up contact were classified based on the RCD entries. Five exclusive outcome classifications were specified: follow-up packet not sent (heretofore, no-packet), unreachable, declined participation, ineligible, or prescreened eligible. The classifications of no-packet, declined participation, and ineligible each had several subgroups (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Outcomes of Attendees Interested in Research

| Alla n (%) |

BCSb n (%) |

No BCSb n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Participation Classification | |||

| Interest in Research Participation | 364 (75.05) | 126 (34.61) | 238 (65.39) |

| No Follow-Up Packet Sent | 106 (29.12) | 29 (27.36) | 77 (72.64) |

| Age Ineligible | 74 (20.32) | 25 (33.78) | 49 (66.22) |

| Enrolled/Recruited in CT | 22 (6.04) | 4 (18.18) | 18 (81.82) |

| Ineligibility Established | 10 (2.74) | 0 (0.00) | 10 (100.00) |

| Follow-Up Packet Sent | 258 (70.88) | 97 (37.60) | 161 (62.40) |

| Unreachable | 112 (30.77) | 35 (31.25) | 77 (68.75) |

| Declined Participation | 88 (24.18) | 35 (39.77) | 53 (60.23) |

| No Elaboration | 24 (6.59) | 8 (33.33) | 16 (66.67) |

| Opposed Element of Study | 28 (7.69) | 10 (35.71) | 18 (64.29) |

| Lumbar Puncture | 15 (4.12) | 7 (46.67) | 8 (53.33) |

| Neuroimaging | 2 (0.55) | 1 (50.00) | 1 (50.00) |

| Study Drug | 11 (3.02) | 2 (18.18) | 9 (81.82) |

| Infusion | 5 (1.37) | 1 (20.00) | 4 (80.00) |

| Visit Frequency/Duration | 5 (1.37) | 0 (0.00) | 5 (100.00) |

| Competing Demands | 39 (10.71) | 21 (53.85) | 18 (46.15) |

| Personal Health | 14 (3.85) | 9 (64.29) | 5 (35.71) |

| Caregiver | 8 (2.20) | 1 (12.50) | 7 (87.50) |

| Leisure Travel/Seasonal Migrant | 6 (1.65) | 2 (33.33) | 4 (66.67) |

| Too Busy | 9 (2.47) | 6 (66.67) | 3 (33.33) |

| Unreliable Transport | 4 (1.10) | 3 (75.00) | 1 (25.00) |

| Social Influences | 5 (1.37) | 1 (20.00) | 4 (80.00) |

| Family Opposition | 3 (0.82) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (100.00) |

| Primary Care Provider Input | 2 (0.55) | 1 (50.00) | 1 (50.00) |

| Ineligible | 37 (10.16) | 17 (45.95) | 20 (54.05) |

| Exclusionary Medical Reason | 36 (9.89) | 16 (44.44) | 20 (55.56) |

| Unable to undergo LP | 3 (0.82) | 3 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Unable to undergo MRI | 4 (1.10) | 1 (25.00) | 3 (75.00) |

| Health Condition | 19 (5.22) | 7 (36.84) | 12 (63.16) |

| Medication | 12 (3.30) | 5 (41.67) | 7 (58.33) |

| Neurologic or Psychiatric | 11 (3.02) | 6 (54.55) | 5 (45.45) |

| No Study Partner | 2 (0.55) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (100.00) |

| Pre-screened Eligible | 21 (5.77) | 10 (47.62) | 11 (52.38) |

| Enrolled | 19 (5.22) | 9 (47.37) | 10 (52.63) |

Note: Within classifications, the sum of ns for subclasses (e.g., four under Declined Participation = 96) may exceed the n of the classification because participants could be designated multiple subclasses; this is true for the groups under subclasses (e.g., under Exclusionary Medical Reason, sum = 49).

In this column Interest in Research Participation % = n/485; all other %s = n/364.

Displays n and % within each Research Participation Classification with BCS or without BCS.

HF attendees interested in research contact were classified as no-packet if they were age-ineligible per the protocols of active studies, actively enrolled in a study, previously determined to be ineligible for enrolling studies, or already in contact with a study coordinator. The no-packet classification precluded other classifications.

Second, each participant was designated any subgroup evident in their RCD entry. To avoid speculation, subgroups were only designated when explicitly evident in the RCD entries. For example, if the note in an RCD entry for a subject declining to participate was leisure travel, that subject was not also designated as being opposed to the frequency of visits or duration of studies, although that might be a reasonable assumption. Third, individuals were ascribed one of the five classifications based on the subgroup(s) that appeared to factor most prominently in their participation outcome.

Individuals were classified as unreachable if [a] recruitment specialists were never able to interact with them or [b] the individual expressed a desire to contemplate participating and indicated no reason they might not participate but were unreachable afterwards. However, if an individual expressed a desire to contemplate participation and indicated reasons they might not participate but were unreachable afterwards, they were classified as declined to participate for the reason(s) they indicated. This may appear to conflict with the intent to avoid speculation but, in practice, such recruits are managed as though they declined to participate because they provided reasons for declining and were unreceptive to repeated contact attempts. Alternatively, individuals satisfying criterion [b] may still receive future research contact. Otherwise, unreachable precluded other classifications.

Individuals were classified as declining to participate if they communicated an unwillingness to participate in interventional research. Reasons for declining were distilled into four subgroups: outright without elaboration, opposition to elements of the study protocol(s), competing demands, and social influences. Individuals were classified as ineligible if it was determined that they met one or more exclusionary criteria for the enrolling study protocol(s). Being ineligible was due either to meeting exclusionary medical reasons (e.g. pacemaker or claustrophobia preventing MRI) or lacking a study partner. Individuals who provided reasons they might decline participation but were also determined to be ineligible via prescreen were classified as ineligible, because regardless of their intent they were ineligible per study protocols. Alternatively, individuals were classified as declining to participate if they declined after expressing interest in a study but no exclusionary factors were identified. To distinguish these two groups, we defined declining to participate as some factor that could be changed or surmounted if the individual so desired whereas ineligible meant there was some factor they could neither change nor readily undo.

Individuals were considered prescreen eligible if they were interested in participating, prescreened as eligible for an enrolling study, and contact was transferred to study coordinator. Individuals who prescreened eligible were classified as such, unless they declined to participate after prescreening eligible but before attending an initial study visit, in which case they were classified as declined to participate. Otherwise, being prescreen eligible precluded any other classification including, for instance, being ineligible for or declining to participate in a study earlier in the follow-up period.

Analysis

Analyses were performed using the R 3.3.2 console. The ‘ggplot2’ package was used for figure creation10. ANOVAs were used to examine age between categorical variables. Fisher Exact tests were used to compare distributions between categorical variables and to compare the proportions among classes that were or were not administered the BCS to test the hypothesis that subjects obtaining a BCS were more likely to get involved in research (i.e., to pre-screen eligible). Survival curves for time-to-coordinator were computed for and compared between prescreen eligible participants who were and were not administered a BCS; a log-rank test was used for comparison.

Results

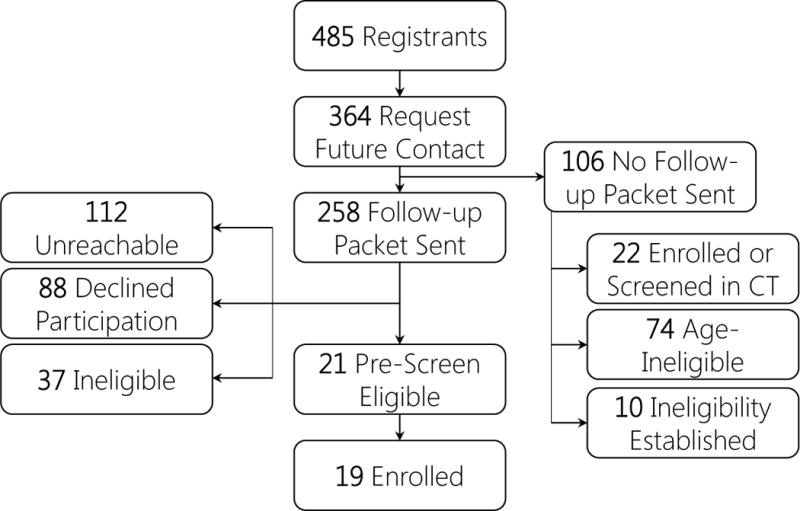

Figure 1 diagrams the progression of participants from attendance to research classification outcome. Of 483 attendees, 364 expressed interest in being contacted for research opportunities and 119 did not. Table 1 shows the outcomes of the 364 participants contacted during the follow-up period. Eleven attendees provided neither age nor sex, all of whom declined follow-up. Eight attendees did not provide age (all but one declined follow-up). Excluding these 19 attendees, descriptives for age and sex are presented in Table 2. Age range of attendees was 20 to 95. Female attendees were significantly younger than males, F(1,460) = 12.52, p < 0.001. Age did not significantly differ between attendees who expressed interest in participation and those who did not, F(1,460) = 0.285, p = 0.59. However, there was a significant research interest by sex interaction, F(1,460) = 3.98, p = 0.05. Among attendees interested in being contacted about research, males were younger than and females were older than their counterparts who were not interested. More female attendees expressed research participation interest (79.2%) than males (69.8%), Fisher’s p = 0.05.

Figure 1.

Note. CT = Clinical Trial. HF = Health Fair.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Health Fair Attendees

| Interested in Research Contact | Not Interested in Research | Totals | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD |

| Female | 290 | 70.38 | 10.65 | 76 | 67.80 | 16.79 | 366 | 69.87 | 12.15 |

| Male | 74 | 73.46 | 8.92 | 32 | 76.82 | 9.89 | 106 | 74.38 | 9.27 |

| TOTAL | 364 | 71.01 | 10.38 | 108 | 70.31 | 15.68 | 472 | 70.86 | 11.72 |

A total of 126 attendees completed a BCS (34.6%) and they were predominantly female (82.54%). The distribution of females was statistically similar to those who did not complete a BCS (77.73%), Fisher’s p = 0.221. There was no difference in age between attendees who engaged in BCS and those who did not, F(1,361) = 0.348, p = 0.55. Ultimately, of the 483 HF attendees, 21 pre-screened as eligible (4.35%), 19 of whom had enrolled in a clinical trial at the close of the follow up period. These 19 individuals enrolled in five different studies (See Table, Supplementary Digital Content 1). Amongst all attendees, 10 of 126 (7.9%) who obtained a BCS pre-screened as eligible whereas only 11 of 357 (3.1%) without a BCS were pre-screened as eligible, Fisher’s p = 0.04, demonstrating a 2.5 greater likelihood of engagement among those undergoing BCS compared to those that did not.

The remainder of the analysis considers only participants who expressed interest in being contacted and who were sent a follow-up packet. That is, HF attendees who were participation-naïve, age-eligible, and not known to be otherwise ineligible. The distributions of sex and mean ages were unchanged by the exclusion, leaving 258 participants (See Table 3). There was no difference in age by sex, F(1,255) = 0.534, p = 0.466 or by classification, F(3,257) = 0.055, p = 0.98. The distribution of sexes was statistically different across classification, Fisher’s p < 0.001. Notably, a greater proportion of males prescreened ineligible and a greater proportion of females were unreachable. Amongst participants sent a follow-up packet, 10 of 97 (10.3%) who obtained a BCS prescreened as eligible whereas only 11 of 161 (6.8%) without a BCS were pre-screened as eligible, Fisher’s p = 0.352.

Table 3.

Characteristics of HF Attendees Interested in Research and Sent Follow-Up Packet, by Outcome Class

| Class | n (%) | Female n (%) |

Male n (%) |

Age mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decline | 88 (34.11) | 74 (36.27) | 14 (25.92) | 74.52 (6.83) |

| Eligible | 21 (8.14) | 15 (7.35) | 6 (11.11) | 74.52 (5.10) |

| Ineligible | 37 (14.34) | 20 (19.23) | 17 (31.48) | 73.97 (6.59) |

| Unreachable | 112 (43.41) | 95 (46.57) | 17 (31.48) | 74.41 (7.78) |

| ALL | 258 | 204 | 54 | 74.39 (7.07) |

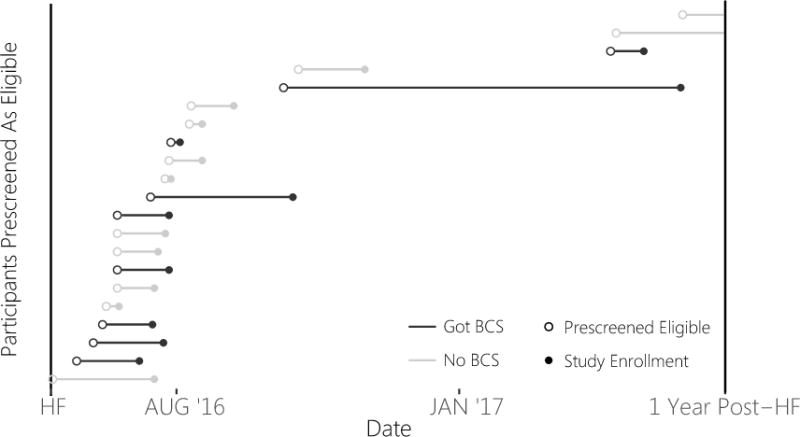

Note. % for Sex derived using respective value in the ALL row. HF = Health Fair.

The distribution of BCS administrations between classifications were not significantly different, Fisher’s p = 0.239. Although we retain the null hypothesis, it is worth noting that the participants we were unable to interact with evidenced the lowest proportion of BCS administrations at the HF. For participants prescreened as eligible, survival curves were computed for the time (days) from the HF to contact with a study coordinator between participants administered a BCS (Median = 36 days, IQR = 37) and those who were not (Median = 63 days, IQR = 54.5). There was no difference in time-to-coordinator, χ2 = 1.1, p = 0.29, and we retain the null hypothesis. Figure 2 shows the timeline from HF to transfer to coordinator for participants who prescreened as eligible.

Figure 2.

Note. Prescreened Eligible means contact was transferred from recruitment specialist to study coordinator. Study Enrollment means the individual completed the study screening visit. The absence of a solid dot means that the participant did not enroll during follow-up. BCS = Brief Cognitive Screen. HF = Health Fair.

Discussion

The present study examined if voluntarily engaging in BCS at a community outreach event predicted future participation in interventional AD studies. We predicted that HF attendees who engaged in research-like behaviors (a BCS) may be more likely to engage in a research study. Consistent with our hypothesis, when looking at all HF attendees irrespective of stated research interest, BCS engagement predicted future research engagement. However, when limited to just those who expressed interest in research, BCS engagement was not a significant indicator of subsequent research participation; however, these results still trended in the direction of BCS predicting engagement. Accordingly, interest in undergoing a BCS may help to predict future research engagement, but for those who already interested in engaging, participation in the BCS may not significantly impact future involvement.

An exploratory hypothesis tested whether engaging in the BCS at the HF reduced the time from the HF to being prescreened as eligible. The motivation for this analysis was that, if individuals engaging in a BCS have a greater desire to participate, then they may enroll sooner than those who did not engage in the BCS. There was no difference in the median time from HF to prescreening for participants who obtained a BCS and those who did not.

The BCS is offered at community events like the HF, providing examinees some exposure to cognitive testing, a prominent aspect of AD research. Many individuals who completed the BCS ended up being identified as ineligible or declined participation due to competing demands related to personal health, unreliable transport, and being too busy. Therefore, while not supporting research engagement directly, offering brief screens like the BCS at community events may provide an accessible and unobtrusive option for individuals who have guarded concerns about their memory or who want reassurance of healthy functioning. While not all of these individuals pursue research engagement immediately after their screen, the BCS may help to reduce anxiety and stigma around memory evaluation and may help them to pursue clinical work-ups when appropriate, potentially increasing the likelihood of research engagement further in the future.

As with all real-world research, this study has several limitations. First, the exact impact of the BCS and the HF on participation are hard to quantify. Successful AD trial recruitment is often the result of sustained community activity over a span of years11–13. Many participants had prior or subsequent contacts with our center through other outreach activities and engagement in research may have occurred after the one-year follow-up period. This can be addressed in future studies by accounting for prior exposures (e.g., other event attendance). Attendees may also share information with family or friends and we are unable able to track interest generated by word-of-mouth back to the HF. Second, recruitment is often a gradual process; interest and eligibility can waiver over time with the vicissitudes of life and the availability of study opportunities. Thus, we have done our best to empirically evaluate recruitment by capturing outcomes during a one-year follow-up period, but recognize that recruitment is truly a dynamic process. Third, the HF and subsequent research engagement examined was confined to one research center in a single geographic area and results may not generalize to other centers and regions. HF attendees may be more receptive to research participation than the general public; therefore, evaluating the BCS in other outreach contexts may reveal different results. Finally, we measured engagement in the BCS but not results of the BCS, and therefore were unable to examine how cognitive status may influence research engagement.

This study makes a valuable contribution to the existing literature by providing a real-world evaluation of one recruitment strategy and highlighting the outreach and follow-up required to enroll research participants. Future research should explore the recruitment outcomes of additional outreach approaches to better enable researchers to make informed, evidence based decisions for how to engage prospective research participants. As more research evaluates recruitment efforts, it may be possible to compare cost effectiveness of different strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Table of characteristics of interventional AD studies enrolling during follow-up period.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The project described was supported by the National Institute on Aging P30 AG028383. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2015;11(3):332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grill JD, Galvin JE. Facilitating Alzheimer’s Disease Research Recruitment. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2014;28(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bower P, Brueton V, Gamble C, et al. Interventions to improve recruitment and retention in clinical trials: a survey and workshop to assess current practice and future priorities. Trials. 2014;15(1):399. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elley CR, Robertson MC, Kerse NM, et al. Falls Assessment Clinical Trial (FACT): design, interventions, recruitment strategies and participant characteristics. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr SA, Davis R, Spencer D, et al. Comparison of recruitment efforts targeted at primary care physicians versus the community at large for participation in Alzheimer disease clinical trials. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2010;24(2):165–170. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181aba927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarrant SD, Bardach SH, Bates K, et al. The Effectiveness of Small-group Community-based Information Sessions on Clinical Trial Recruitment for Secondary Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2016 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buschke H, Kuslansky G, Katz M, et al. Screening for dementia with the memory impairment screen. Neurology. 1999;52(2):231–231. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghent L. Perception of overlapping and embedded figures by children of different ages. The American journal of psychology. 1956;69(4):575–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etkin CD, Farran CJ, Barnes LL, Shah RC. Recruitment and enrollment of caregivers for a lifestyle physical activity clinical trial. Research in nursing & health. 2012;35(1):70–81. doi: 10.1002/nur.20466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jefferson AL, Lambe S, Chaisson C, Palmisano J, Horvath KJ, Karlawish J. Clinical research participation among aging adults enrolled in an Alzheimer’s Disease Center research registry. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease. 2011;23(3):443–452. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galvin JE, Meuser TM, Morris JC. Improving physician awareness of Alzheimer’s disease and enhancing recruitment: the Clinician Partners Program. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2012;26(1):61. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318212c0df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Table of characteristics of interventional AD studies enrolling during follow-up period.