Abstract

Radial spokes (RSs) are multiprotein complexes that regulate dynein activity. In the cell body, RS proteins (RSPs) are present in a 12S precursor, which enters the flagella and converts into the axoneme-bound 20S spokes consisting of a head and stalk. To study RS dynamics in vivo, we expressed fluorescent protein (FP)-tagged versions of the head protein RSP4 and the stalk protein RSP3 to rescue the corresponding Chlamydomonas mutants pf1, lacking spoke heads, and pf14, lacking RSs entirely. RSP3 and RSP4 mostly co-migrated by intraflagellar transport (IFT). The transport was elevated during flagellar assembly and IFT of RSP4-FP depended on RSP3. To study RS assembly independently of ciliogenesis, strains expressing FP-tagged RSPs were mated to untagged cells with, without, or with partial RSs. Tagged RSPs were incorporated in a spotted fashion along wild type-derived flagella indicating an exchange of radial spokes. During the repair of pf1-derived axonemes, RSP4-FP is added onto the preexisting spoke stalks with little exchange of RSP3. Thus, RSP3 and RSP4 are transported together but appear to separate inside flagella during the repair of RSs. The 12S RS precursor encompassing both proteins could represent a transport form to ensure stoichiometric delivery of RS proteins into flagella by IFT. (198 words)

Keywords: axoneme, cilia, flagella, intraflagellar transport (IFT), RSP3, RSP4

1 Introduction

The 9+2 axoneme is a highly ordered molecular machine consisting of dozens of distinct proteins conferring motility to cilia and flagella (Dutcher, 1995; Lefebvre and Silflow, 1999; Pazour et al., 2005). Ciliary proteins are synthesized in the cell body and then moved into the cilium followed by assembly into the axoneme. Transports of several axonemal proteins into cilia involves intraflagellar transport (IFT), a bidirectional motility of motorized protein carriers along the axonemal microtubules (Craft et al., 2015; Kozminski et al., 1993; Lechtreck, 2015; Wren et al., 2013). Certain axonemal substructures such as inner and outer dynein arms and radial spokes (RSs) are preassembled in the cell body prior to transport into the cilium (Fowkes and Mitchell, 1998; Piperno and Mead, 1997; Qin et al., 2004; Viswanadha et al., 2014). Outer dynein arms (ODAs) isolated from the cell body apparently comprise all subunits present in the mature axonemal ODAs; they will dock at the right sites onto the axoneme in vitro indicating that they are assembly competent and probably functional.

Here, we study the assembly of radial spokes (RSs), which project from the nine doublet microtubules toward the central pair and regulate the activity of dyneins by transmitting mechanical cues from the central pair (Oda et al., 2014; Smith and Yang, 2004). Mutations affecting the RSs result in paralyzed flagella (pf) phenotypes in protists (Piperno et al., 1977; Vasudevan et al., 2015) and cause primary ciliary dyskinesia in humans (Frommer et al., 2015). The RS consists of ~23 distinct proteins organized into the spoke head, the spoke neck, and the spoke stalk (Luck et al., 1977; Pigino et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2006). IFT has been also implicated in RS transport but direct evidence is still missing (Johnson and Rosenbaum, 1992; Qin et al., 2004). Similar to dynein arms, RSs are partially preassembled in the cell body. However, the RS precursor is a Γ-shaped 12S complex, which is moved into flagella and converted into the mature T-shaped 20S complex present on the axonemal microtubules (Diener et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2004). During spoke maturation, additional RS proteins (RSPs) that are not part of the 12S precursor (e.g., RSP16, HSP40 and LC8) are added to the complex (Gupta et al., 2012). However, how the 12S RS particles is converted into the mature RSs remains unclear.

We used fluorescent protein (FP)-tagged RSPs in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to analyze the transport and assembly of the RS. We focused on RSP3, a key structural protein of the spoke stalk; the N-terminus of RSP3 is close to doublet microtubules while its C-terminus extends into the spoke head (Oda et al., 2014). Spoke-less axonemes are assembled in pf14, a mutant lacking full-length RSP3 (Williams et al., 1989). As a marker for the spoke head, we tagged RSP4. Homodimers of RSP4 and the paralogous protein RSP6 form the two wings of the spoke head, respectively (Curry et al., 1992). In vivo imaging revealed that RSP4 and RSP3 are mostly co-transported by IFT confirming previous biochemical data that both proteins are part of the 12S RS precursor. The mutant pf1 lacks functional RSP4 causing a loss of the spoke heads while RSP3-containing stalks are retained (Luck et al., 1977). Two color imaging showed incorporation of tagged RSP4 into pf1 flagella independently of tagged RSP3 suggesting that the repair of the truncated pf1 RSs occurs by addition of spoke heads. In wild-type cilia, RSs are replaced in a random pattern at a low frequency with ~5% or less of the RSs exchanged per hour. We propose that the 12S RS precursor presents a transport complex of RSPs ensuring stoichiometric delivery of RSPs into flagella; bundling of RS proteins in one complex also reduces the cargo number of binding sites required on IFT trains.

2 RESULTS

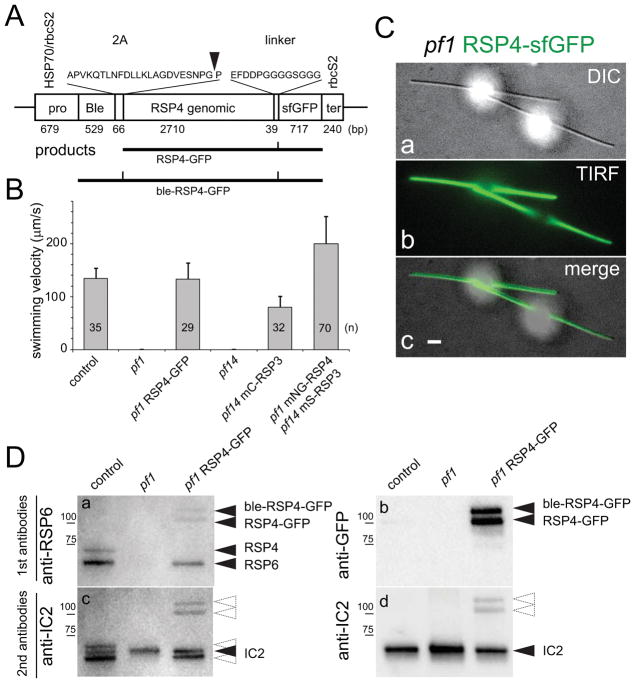

2.1 RSP4-sfGFP rescues the spoke-less pf1 mutant

Using a derivative of the bicistronic vector pBR25, the spoke-head protein RSP4 was tagged at its C-terminus with sfGFP and expressed in C. reinhardtii pf1, a mutant lacking functional RSP4 (Fig. 1A)(Rasala et al., 2013). As previously reported for RSP4-GFP, expression of RSP4-sfGFP rescued the paralyzed flagella (pf)-phenotype in ~50% of the transformants analyzed (Fig. 1B)(Oda et al., 2014). TIRF imaging of live cells showed that RSP4-sfGFP was present along the length of the flagella (Fig. 1C). For western blot analyses, we used an antibody raised against RSP6, which also reacts with RSP4. RSP4 and RSP6 are paralogues sharing 47% identity and depend on each other for assembly into flagella (Curry et al., 1992). In flagella of control cells, the antibody recognized two bands corresponding to RSP4 and the somewhat smaller RSP6 (Fig. 1D). Both bands were absent in the pf1 mutant cilia. In the pf1 RSP4-sfGFP rescue strain, the RSP6 band was restored while the RSP4 band was replaced by two slower migrating bands. These bands also reacted with anti-GFP and hence represent RSP4-sfGFP and uncleaved ble-RSP4-sfGFP (Fig. 1D); the amount of uncleaved ble-RSP4-sfGFP varied between preparations. In summary, expression of RSP4-sfGFP restored wild-type motility in pf1 suggesting that it can be used to monitor radial spoke (RS) transport in living cells.

Figure 1. RSP4-sfGFP rescues the pf1 mutant.

A) Schematic presentation of the bicistronic vector used to express RSP4-sfGFP. Due to incomplete cleavage of the 2A sequence, transformants express both RSP4-sfGFP and the uncleaved ble-RSP4-sfGFP.

B) Swimming velocity of wild type, and the pf1 and pf14 rescue strains. n, number of cells analyzed; Error bars indicate standard deviation.

C) DIC (a), TIRF (b), and merged (c) images of a live cell expressing RSP4-sfGFP. Bar = 2μm.

D) Western blots analyzing flagella isolated from wild-type (control), pf1, and the pf1 RSP4-sfGFP rescue strain. The two replicate membranes (a/c and b/d) were first stained with anti-RSP6 (a) or anti-GFP (b) and subsequently with anti-IC2, a component of outer arm dynein, as a loading control. The positions of RSP6, RSP4, RSP4-sfGFP, ble-RSP4-sfGFP, and standard proteins are indicated. Dashed arrowheads indicate residual signals from the first round of antibody staining.

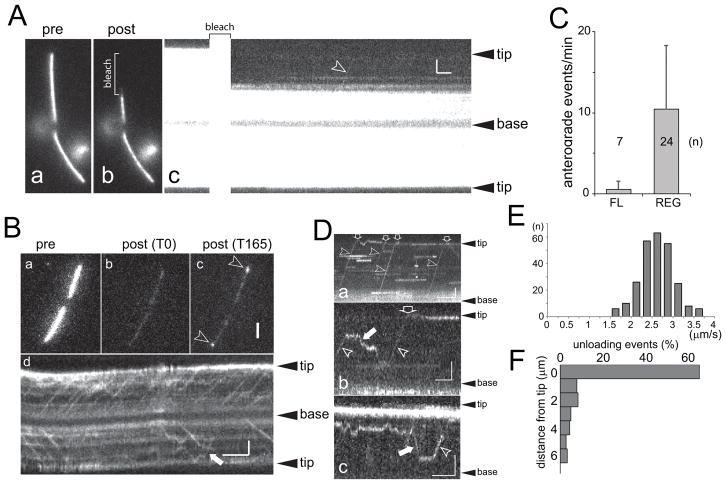

2.2 RSP4-sfGFP is a cargo of IFT

Previous data indicate that radial spokes move via IFT into flagella but formal demonstration of this transport has not yet been reported (Johnson and Rosenbaum, 1992; Qin et al., 2004). After photobleaching of RSP4-sfGFP already incorporated into the flagella, IFT-like transports of RSP4-sfGFP became visible (Fig. 2A). In steady-state flagella of the pf1 RSP4-sfGFP cells, anterograde IFT of RSP4-sfGFP was observed only occasionally with a frequency of 0.6 transports/min. To study transport in growing flagella, cells were deflagellated by a pH shock and allowed to initiate flagellar regeneration prior to mounting for TIRF imaging (Fig. 2B, C). In such cells, the average anterograde transport frequency of RSP4-sfGFP was 10.4 transports/min and a maximum of 30 transports/min was observed (Video 1). This is close to the expected rate of RS transport of 36 transports/minute, i.e., ~2,200 RSs have to enter each flagellum during regeneration, which requires ~60 minutes.

Figure 2. Transport of RSP4-sfGFP is upregulated during flagellar growth.

A) Cell with steady-state flagella before (a) and after (b) photobleaching of the distal segment of one flagellum (indicated by a brackets in b and c). The corresponding kymogram shows a single anterograde transport event (arrowhead in c). Bars = 2s 2μm.

B) A cell during regenerating flagella before (a), immediately after photobleaching (b, T0), and 165 s after the bleach (c). Note incorporation of unbleached RSP4-sfGFP at the distal ends of both flagella (arrowheads in c) indicative for axonemal elongation and spoke assembly. d) Kymogram of a regenerating flagellum showing numerous transport events of RSP4-sfGFP. White arrows, retrograde transport. Bars = 2s 2μm.

C) Anterograde IFT events of RSP4-sfGFP observed in full-length (FL) and regenerating (REG) flagella. n, number of flagella analyzed.

D) Gallery of kymograms depicting RSP4-sfGFP transport to the flagellar tip and dwelling at the tip (a), unloading and reloading from IFT, diffusion, and retrograde transport (b, c). Arrowheads, anterograde transports; filled arrows, retrograde transport; open arrows, arrival at the flagellar tip. Kymograms are based on recordings of tagged RSP4 in the pf1 RSP4-derived (a) and pf1-derived (c) flagella of pf1 RSP4-sfGFP × pf1 zygotes and wild type-derived flagella of pf1 RSP4-sfGFP × wild type zygotes (b). Bars = 2s 2μm. See figure S1 for additional kymograms.

E) Distribution of the velocity of anterograde RSP4-sfGFP transports.

F) Distribution of IFT transport termination points of RSP4-sfGFP along the flagella. Note high share of RSP4-sfGFP transport moving processively to the flagellar tip.

To study details of RSP4-sfGFP transport, we used zygotes obtained by mating pf1 RSP4-sfGFP cells to untagged wild type or RS mutant cells (Video 2). The untagged flagella of such zygotes are well suited to image RSP4-sfGFP traffic because they are full-length and initially lack GFP incorporated into the axoneme abolishing the need to photobleach (see Fig. 3A). Most RSP4-sfGFP transport events progressed uninterrupted from the flagellar base to the tip (Fig. 2Da, E). Anterograde transport of RSP4-sfGFP progressed at typical IFT rates with an average velocity of 2.4 μm/s (STD 0.4 μm/s, n=256); retrograde transport was observed only rarely (white arrows in Fig. 2B, D). Transitions from IFT to diffusion and vice versa along the flagellar shaft were observed as well (Fig. 2D). RSP4-sfGFP arriving via IFT at the flagellar tip often moved to a subdistal position and remained stationary for extended times exceeding those observed for other axonemal proteins (Fig. S1) (Wren et al., 2013). Previously, it was proposed that the RS precursors are remodeled into mature spokes at the flagellar tip and the extended pausing of RSP4-sfGFP at the tip observed here could indicate that a modification of the RS precursor occurs (Gupta et al., 2012). Apparent assembly of RSP4-sfGFP onto pf1 axonemes was rarely observed; the putative assembly events shown in Fig. S1f were preceded by extended periods of diffusion. We conclude that RSP4-sfGFP is a cargo of IFT, that it mostly moves processively via IFT to the tip and that RSP4 transport is strongly upregulated in regenerating flagella.

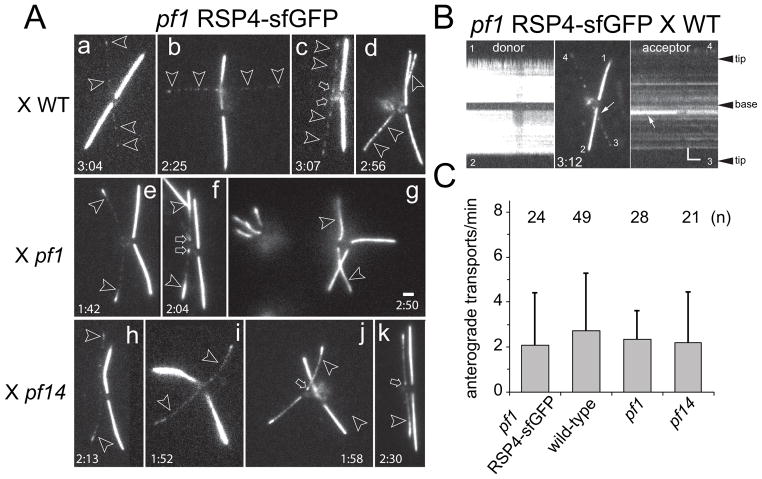

Figure 3. RSP4-sfGFP incorporates with distinct patterns into pf1 and pf14 flagella.

A) Gallery of still images of live zygotes from crosses between pf1 RSP4-sfGFP and wild-type (WT; a–d), pf1 (e–f), and pf14 gametes (h–k). Acceptor flagella are marked by arrowheads. The time passed between the mixing of the gametes and the recording is noted on each image (h:mm). Late zygotes are shown in g; arrows in c and f mark proximal RSP4-sfGFP signals. Bar = 2μm.

B) Kymograms and still image of a pf1 RSP4-sfGFP × wild type zygote. Horizontal trajectories in the acceptor flagella reveal that RSP4-sfGFP is stationary likely because of stable incorporation into the axoneme. Arrow: Crossing point of flagellum No. 2 and No. 3. Bar = 2s 2μm.

C) Transport frequency of RSP4-sfGFP in zygotic flagella. n: number of flagella analyzed.

2.3 RSP4 incorporates with distinct patterns into wild-type, pf1, and pf14 flagella

Next, we analyzed RS assembly and repair in full-length flagella using zygotes obtained by mating RS mutants and RSP4-sfGFP cells. Proteins provided by the latter will enter and assemble in the mutant–derived flagella restoring RSs. Previous experiments based on antibody staining suggest that radial spoke precursors are transported by IFT to the flagellar tip where they are released followed by diffusion to nearby axonemal assembly sites resulting in a tip-to-base progression of RS protein incorporation (Johnson and Rosenbaum, 1992; Qin et al., 2004). The pf1 RSP4-sfGFP strain was mated to wild-type, pf1, and pf14 (Fig. 3A). The zygotes possessed two GFP-positive flagella derived from the pf1 RSP4-sfGFP donor strain and two acceptor flagella initially devoid of GFP-tagged protein. In matings with wild type, RSP4-sfGFP was present in a spotted fashion along wild-type derived flagella (Fig. 3Aa–d). Kymograms revealed that these signals are stationary and remained in place for extended periods of time suggesting stable incorporation of the protein into the axoneme (Fig. 3B). After mixing of the gametes, cell fusion will occur over an extended period of time; thus, the precise age of a zygote is typically unknown and the times indicated in Fig. 3A present the maximum age of the zygotes. However, flagella progressively shorten during zygote maturation and more mature zygotes can be recognized by the presence of shorter flagella. In the wild-type derived flagella of older zygotes, the signals representing RSP4-sfGFP were mostly stronger and more continuous (Fig. 3Ad). The data suggest that untagged RSP4 was exchanged with RSP4-sfGFP indicative of partial or complete RS turnover; however, nonspecific binding of RSP4-sfGFP particles to the axoneme cannot be excluded. In pf1 RSP4-sfGFP × pf1 zygotes, RSP4-sfGFP was added in a pronounced tip-to-base pattern to the formerly pf1 flagella (Fig. 3Ae–g). Most cells showed RSP4-sfGFP incorporation also in a small region near each flagellar base, a region for which IFT-independent assembly of RSs has been proposed (Alford et al., 2013). In older zygotes, RSP4-sfGFP was equally or almost equally present along all four flagella indicative for complete repair (Fig. 3Ag). In contrast to the repair of pf1-derived flagella, RSP4-sfGFP incorporation into pf14-derived flagella, while more pronounced near the tip, was also well represented along the length of the flagella (Fig. 3Ah–k). This observation is in agreement with previous antibody-based analyses of RS assembly in pf14 flagella (Johnson and Rosenbaum, 1992). Note that in our experiments, zygotes possessed both tagged and untagged RSP4, which likely contributes to the overall weaker signals of RSP4-sfGFP in the pf14-derived flagella. We conclude that the addition of RSP4-sfGFP to pf14- and pf1-derived flagella follow distinct patterns indicating differences between RS repair and RS de novo assembly.

We wondered whether RS transport is regulated by demand and thus is elevated in flagella lacking the spoke heads or the entire spokes. With ~2 events/min, the transport frequency of RSP4-sfGFP in zygotic flagella was above that of non-regenerating flagella and below that of regenerating flagella of vegetative cells. Regardless of whether RSs were present, partially present (pf1), or absent (pf14), the transport frequencies were similar indicating that RSP4-sfGFP transport is not regulated by the presence or absence of intact RSs inside flagella (Fig. 3C). Based on the weakness of the signal in full-length flagella and low frequency at which diffusion was observed, most of RSP4-sfGFP transported into wild-type cilia is likely to exit the cilia by diffusion or IFT.

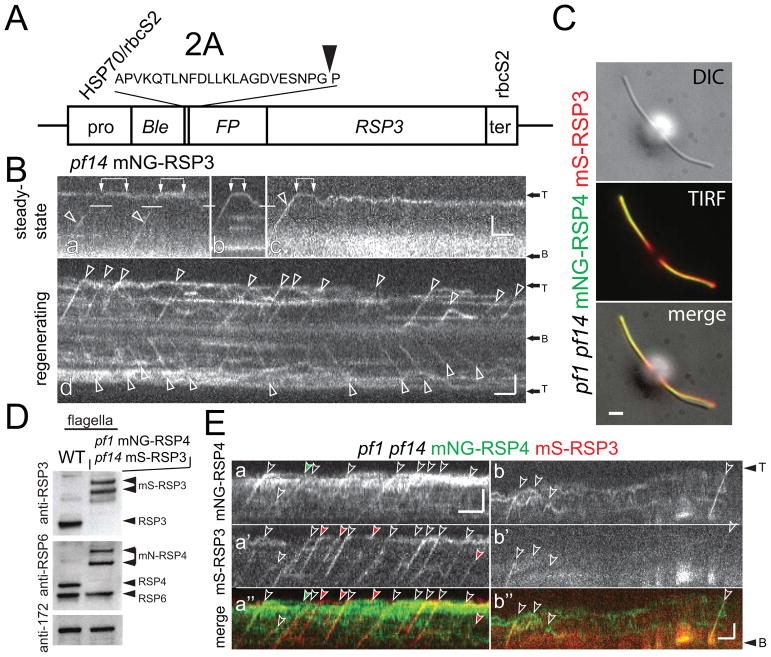

2.4 RSP3 is a cargo of IFT

Next, we rescued the pf14 mutant by expression of RSP3 tagged at its N-terminus with mNeonGreen (mNG); rescue was also observed for mScarlet-I (mS), mCherry (mC), and mTAG-BFP N-terminal fusions and has been previously reported for a C-terminal RSP3-GFP fusion (Fig. 4A and not shown; (Yanagisawa et al., 2014)). Similar to RSP4-sfGFP, mNG-RSP3 is transported by IFT; its transport frequency is elevated during flagellar regeneration, and most transports progressed uninterrupted to the flagellar tip (Fig. 4B). At the flagellar tip, mNG-RSP3 paused only briefly before the on-set of diffusion, which is distinct from our observations on RSP4-sfGFP (Fig. 4Ba–c). In matings with pf14, mNG-RSP3 was incorporated along the length of the pf14-derived flagella; incorporation was somewhat stronger in the distal flagellar region (Fig. S2).

Figure 4. Tagged RSP4 and RSP3 are co-transported by IFT.

A) Schematic presentation of the vector used for FP-tagging of RSP3.

B) Kymograms showing mNG-RSP3 in steady state (a–c) and regenerating (d) flagella. Transport events are marked with arrowheads, interconnected pairs of white arrows indicate dwelling of mNG-RSP3 at the flagellar tip. Bars = 2s 2μm.

C) DIC and TIRF images of a pf1 pf14 mNG-RSP4 mS-RSP3 cell obtained by mating pf1 mNG-RSP4 and pf14 mS-RSP3. Bar = 2μm.

D) Western blots analyzing flagella isolated from wild-type (WT) and the pf1 pf14 mNG-RSP4 mS-RSP3 strain. Two replica membranes were stained with anti-RSP3 and anti-RSP6 as indicated. Anti-IFT172 staining was used to control for equal loading.

E) Kymograms of regenerating flagella of the double-tag RS strain; flagella where partially photobleached prior to the recording. Transports are indicated by arrowheads; in detail, open arrowheads mark co-transports while sole mNG-RSP4 and mS-RSP3 transports are marked with green and red arrowheads, respectively. Bars = 2s 2μm.

Biochemical studies in C. reinhardtii showed that RSP4 and RSP3 are both present in the 12S RS precursor complex in the cell body and ciliary marix (Diener et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2004). To analyze whether these proteins remain associated during assembly, we generated a strain expressing RSP3 and RSP4 tagged with different colors by mating pf14 mC-RSP3 to pf1 RSP4-sfGFP. While mNG and sfGFP-tagged versions of RSP3 were readily detectable during transport, we were not able to detect mC-RSP3 transport, which could be explained by the low brightness and stability of mC. During the course of this study, mScarlet I (mS), a novel bright monomeric red fluorescent protein, became available (Bindels et al., 2017). Using mating, we generated a strain expressing mS-RSP3 and mNG-RSP4 in the corresponding double mutant background (Fig. 4C, D). Co-transport of tagged RSP3 and RSP4 was observed in regenerating flagella of this strain (Fig. 4E). mS-RSP3 co-migrated with RSP4-sfGFP in the majority (~90%, n>100) of the analyzed transports. Imaging of these transports required photobleaching of mNG-RSP4 and mS-RSP3 already incorporated into the regrowing flagella and bleaching of mNG-RSP4 was often incomplete obscuring weaker transport signals and putatively explaining the apparent lack of mNG-RSP4 signals in a fraction of the mS-RSP3 transports. Co-migration of RSP3 and RSP4 was also observed in longer flagella, when only a small share of the IFT trains carried the two tagged RS cargoes suggesting that both proteins are in a complex rather than being transported independently of each other on the same IFT train. RSP3 and RSP4 are thought to be dimers in the mature spokes and likely in the 12S precursor suggesting that TIRF microscopy allows for simultaneous in vivo imaging of two low-abundance proteins in C. reinhardtii flagella (Johnson and Rosenbaum, 1992; Oda, 2017) ). The data support the notion that RSP3 and RSP4 are in a complex during IFT transport.

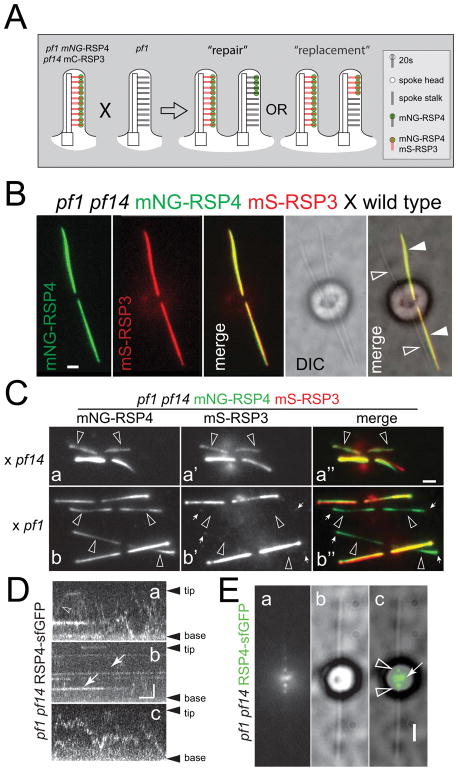

2.5 During the repair of pf1 axonemes, RSP4 is added to preexisting stalks

Flagella of pf1 already possess RSP3-containing spoke stalks. The repair of pf1 axonemes in dikaryons could occur by the addition of spoke heads onto the preexisting stalks or by replacement of those stalks with newly imported entire RSs; the outcome will potentially inform on the permanence of the RSP3/RSP4-containing RS precursor during the conversion into mature spokes (Fig. 5A). To distinguish between these two possibilities, the mS-RSP3 mNG-RSP4 strain was mated to pf1 gametes and, as controls, to pf14 and wild-type gametes. Initially, the tagged proteins were restricted to the donor flagella of such zygotes (Fig. 5B). As the zygotes matured, the tagged proteins became detectable in the acceptor flagella (Fig. 5C). Both proteins were incorporated into pf14-derived spoke-less flagella (Fig. 5Ca). The mNG-RSP4 and mS-RSP3 levels mostly remained below those of the donor flagella putatively indicating a partial repair within the time available prior to the resorption of zygotic flagella. In pf1-derived flagella, mNG-RSP4 was readily visible in distal segments of early zygotes and along most of the length in later zygotes indicative for tip-to-base assembly (Fig. 5Cb). In contrast, the signals representing mS-RSP3 in the mutant-derived flagella were weak and mostly limited to the tips even when the acceptor flagella contained a near full complement of mNG-RSP4 (Fig. 5Cb). Similar patterns were observed in matings using the pf1 pf14 RSP4-sfGFP mC-RSP3 strain (Fig. S3). Apparently, RSP4-sfGFP can be added to pf1 flagella independently of mS-RSP3 incorporation. The data favor a model in which RSP4-containing head complexes are added to the preexisting spoke stalks of pf1 flagella (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. RSP4 assembles into spoke head-deficient.

pf1 flagella independently of RSP3

A) Schematic presentation of the mating between pf1 pf14 mNG-RSP4 mS-RSP3 and pf1, and the possible outcomes, i.e., spoke repair by addition of RSP4-sfGFP heads or spoke replacement with newly imported mS-RSP3 mNG-RSP4 spokes.

B) Early pf1 pf14 mNG-RSP4 mS-RSP3 × wild type zygote showing the fluorescent donor flagella (filled arrowheads) and the wild-type derived acceptor flagella (open arrowheads) lacking fluorescence. Bar = 2 μm.

C) TIRF images of zygotes obtained by mating the double-tag RS strain to either pf14 or pf1. Shown are the mNG (a/b), the mS (a′/b′), and the merged (a″/b″) images of live cells. Arrowheads indicate the acceptor flagella. Note presence of both tagged RSP3 and RSP4 in the pf14-derived flagella. Small arrows, incorporation of mS-RSP3 at the tip of pf1-derived flagella. Bar = 2 μm.

D/E) Analysis of RSP4-sfGFP in pf1 pf14 cells. D) Kymograms showing IFT of RSP4-sfGFP (a) and diffusing (c) and stationary (b) protein. Bar = 2s 2 μm.

E) TIRF, bright field and merged image of a pf1 pf14 RSP4-sfGFP cell showing the accumulation of RSP4-sfGFP in the basal body region (arrow) and at the base of each flagellum (arrowheads). Bar = 2μm.

2.6 IFT of RSP4-sfGFP requires RSP3

The observation that mNG-RSP4 incorporates into pf1 flagella without the apparent replacement of untagged RSP3 with mS-RSP3 could be explained by the transport of a RSP4-sfGFP complex independently of RSP3. Indeed, Diener et al. (2011) reported the presence of a RSP4/6/9/10 complex in the cell body cytoplasm of pf14 mutants indicating that near complete spoke heads assemble in the absence of RSP3. To test if such head complexes travel via IFT, we expressed RSP4-sfGFP in pf1 pf14 double mutants (Fig. 5D, E). Anterograde and retrograde IFT of RSP4-sfGFP was sporadically observed in both steady state and regenerating flagella but its frequency was exceedingly low (<0.01 events/minutes; Fig. 5Da). Further, some RSP4-sfGFP diffused inside pf1 pf14 flagella (Fig. 5D) and occasionally remained stationary in the mutant flagella indicating an association with the axoneme (Fig. 5Db). Axonemal binding and residual IFT of mNG-RSP4 in pf14 could be explained by the formation of a transport-competent complex with truncated RSP3 protein, which is present in a small amount in pf14 cell bodies (Diener et al., 1993; Williams et al., 1989). However, residual IFT or low frequency diffusion of RSP4-sfGFP are unlikely to explain the tip-to-base pattern observed during the repair of pf1 flagella. The data suggest that RSP3 and RSP4 are transported together into pf1-derived flagella and then separate followed by assembly of a head complex containing RSP4-sfGFP onto the preexisting spoke stalks. We assume that RSP3, which is not needed for the repair, will eventually be exported from cilia by IFT or diffusion.

Interestingly, RSP4-sfGFP accumulated near the basal bodies of many pf1 pf14 RSP4-sfGFP cells with steady state or regenerating flagella (Fig. 5E). In contrast to previous antibody-based studies, an accumulation of RSP4-sfGFP and mNG-RSP3 was not observed in the corresponding pf1 and pf14-derived rescue strains with growing or steady state flagella (not shown; (Qin et al., 2004)). Thus, the RSP4-sfGFP build-up at the basal bodies is likely to be related to the near complete failure of RSP4-sfGFP to associate to IFT in the absence of RSP3. This could suggest a two-step cargo-loading process, in which cargoes are first recruited to the flagella base and then handed over to IFT trains.

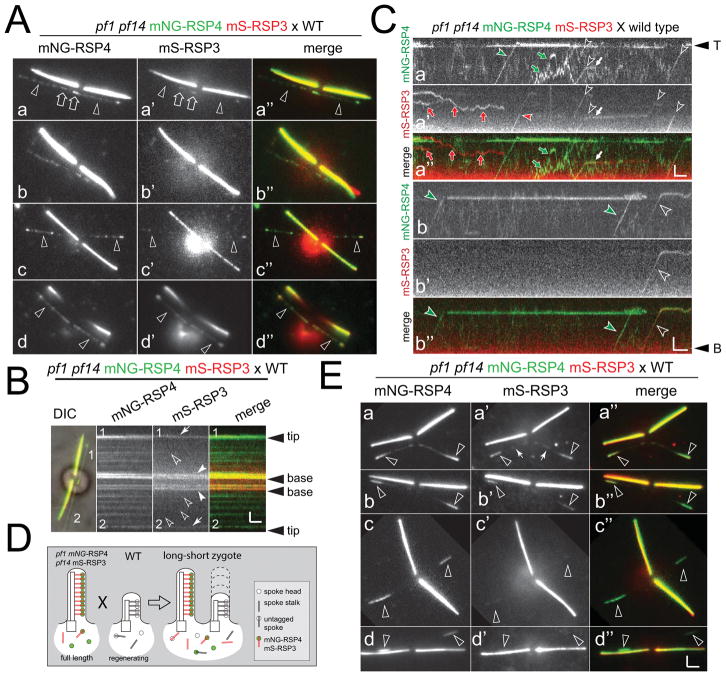

2.7 RSs are exchanged at a low rate in full-length cilia

Matings between the double-tag RSP3 RSP4 strain and wild type allow for an assessment of RS exchange as apparent the incorporation of tagged RSPs into the wild type-derived flagella (Fig. 6A). In such zygotes, we observed stable incorporation of mNG-RSP4 along the length of the wild type-derived flagella while the signal representing mS-RSP3 was generally weak or absent (Fig. 6A, B). The preferred incorporation of mNG-RSP4 compared to tagged RSP3 into the wild type-derived flagella could be explained by a preferred exchange of the untagged spoke heads with mNG-RSP4-containing complexes without exchange of the spoke stalks. However, other explanations for a reduced presence of an mS-RSP3 signal in such flagella exist: mS, for example, is less bright and less stable than mNG and it requires more time to mature rendering new synthesized mS-RSP3 invisible in TRIF microscopy (Bindels et al., 2017; Shaner et al., 2013). Also, in wild type X pf1 pf14 mS-RSP3 mNG-RSP4 zygotes, the tagged RSP proteins are in competition with the endogenous proteins for incorporation into the RS precursor, transport by IFT and assembly into the axoneme. Direct two-color imaging of transport events in zygotes showed co-transports of the two tagged RSPs (n=8) but transports of mNG-RSP4 without an mS-RSP3 signal (n=16) and mS-RSP3 without a mNG-RSP4 (n=5) were observed as well (Fig. 6C). The latter could represent complexes encompassing both tagged and endogenous RSPs. Such tagged-untagged hybrid complexes can only form after gamete fusion and their apparent presence suggests that the 12S precursors are dynamic. On rare occasions, we observed the separation of mS-RSP3 and mNG-RSP4 inside flagella (white arrow in Fig. 6Ca; n=2). A preference of untagged over tagged RSP3 could reduce the presence of tagged RSP3 in flagella and prevent a realistic assessment the rate of RSP3 exchange.

Figure 6. Lateral exchange of RSs in full-length flagella.

A) Gallery of images from zygotes obtained by mating pf1 pf14 mNG-RSP4 mS-RSP3 to wild-type cells. Arrowheads, acceptor flagella; arrows, signal near flagellar base. Note that the signal representing mNG-RSP4 exceeds that of mS-RSP3 in the acceptor flagella. Bar = 2μm.

B) Merge DIC and TIRF image of the zygote shown in Fig. 5Aa-a″ and the corresponding kymograms of the acceptor flagella as indicated. Incorporation of mS-RSP3 at the flagellar tip (arrows), along the flagella (open arrowheads) and near the flagellar base (full arrowheads) are marked. 1, 2, indicate the flagellar number. Bar = 2s 2μm.

C) Kymograms of acceptor flagella of pf1 pf14 mNG-RSP4 mS-RSP3 × wild type zygotes. Transports are indicated by arrowheads; in detail, open arrowhead mark co-transports while sole mNG-RSP4 and mS-RSP3 transports are marked by green and red arrowheads, respectively. Red and green arrows, diffusion of mS-RSP3 and mNG-RSP4, respectively. White arrow in a, apparent separation of mNG-RSP4 and mS-RSP3; the latter remains stationary. Bars = 2s 2μm.

D) Schematic presentation of a long-short experiment in zygotes to test for a possible completion of tagged and untagged RSPs.

E) Gallery of zygotes obtained by mating wild-type cells with regenerating flagella to double-tag cells with full-length flagella. Arrowheads, acceptor flagella; arrows, spotted mS-RSP3 signals in the flagellar mid segment. Bar = 2s 2μm.

To assess a possible discrimination of tagged RSPs further, we mated wild-type cells with regenerating flagella to double-tag cells with full-length flagella (Fig. 6D, E). During the assembly of the flagellar segment built before cell fusion, only untagged RSPs are available whereas after cell fusion tagged and untagged species are available for assembly into the distal flagellar segment (Fig. 6D). The mNG-RSP4 was robustly incorporated into distal segments of the acceptor flagella while the amount of mS-RSP3 in these distal segments varied greatly from bright signals to not detectable (Fig. 6E). For mNG-RSP4, the signal strength in the distal segment was 34% (STD 20.8%, n=9; relative signal/length) of that of the donor flagella, the signal of mS-RSP3 was 3.1% (STD 6.2%, n=9) of that of the donor flagella. Considering the dependency of RSP4 on RSP3 for IFT and axonemal incorporation, we conclude that untagged RSP3 outcompetes the tagged derivative during the assembly of the distal segments of such zygotes. By extension, the preferred incorporation of tagged RSP4 vs. tagged RSP3 into wild type-derived zygotic flagella can be explained by a discrimination against mS-RSP3 rather than being indicative for an accelerated exchange of the RSP4-containing spoke heads. At 2 – 3 hours after mating, the strength of the mNG-RSP4 signal along the length of the wild-type derived acceptor flagella in zygotes excluding the tip and base regions was ~6% (STD 9.7%, n=11) of the signal in the donor cilia. Assuming that both tagged and untagged RSP4 are used for axonemal maintenance and that both proteins are equally available in the cell body, we estimate that approximately ~100 of the ~2,200 RSs in a ~12-μm long flagellum are exchanged during one hour.

3 Discussion

Previous biochemical and immunofluorescence-based data suggest that a 12S complex encompassing most RSPs is transported by an active mechanism to the flagellar tip (Johnson and Rosenbaum, 1992 Qin et al., 2004). In vivo imaging demonstrates IFT of two FP-tagged RSPs in Chlamydomonas flagella and uncovered additional features of RS transport in flagella, which would be difficult to determine by biochemical approaches. For example, the transport frequency of both proteins is upregulated during flagellar elongation further supporting the notion that the amount of axonemal proteins present on IFT trains is increased during flagellar growth (Craft et al., 2015; Wren et al., 2013). RSP transports showed a high propensity to move on IFT trains in one run from the flagellar base to the tip. The processivity of an IFT-cargo complex is likely to reflect the stability of the interaction and since different cargoes attach to distinct sites of the IFT particle or train, differences in the stability of the various IFT-cargo complexes are expected (Bhogaraju et al., 2013; Lechtreck, 2015; Taschner et al., 2017). Based on the distribution of unloading sites along the flagellar length, the RS-IFT complex is more stable than the DRC4-IFT complexes and less stable than tubulin-IFT complexes.

Two-color live imaging of FP-tagged RSP3 and RSP4 showed that they co-migrate on given IFT trains. Thus, TIRF microcopy is suited to image two proteins of low abundance simultaneously while moving inside C. reinhardtii flagella. IFT trains are polymeric structures providing multiple repetitive cargo binding sites (Pigino et al., 2009). However, co-transport of both proteins was also observed in longer regenerating flagella and in full-length zygotic flagella when the transport of RSPs occurred at a low frequency. This suggests that both proteins are in a complex rather than being associated independently of each other to different “carts” of the same IFT train. In summary, the in vivo imaging data demonstrate that RSP3 and RSP4 are in complex while being transported by IFT inside flagella (Diener et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2004).

How the 12S RS precursor complex is converted into the axonemal 20S spokes remains unclear. Two of the Γ-shaped 12S complexes could dimerize to form the T-shaped mature RSs (Pigino and Ishikawa, 2012). Alternatively, one 12S precursor could be remodeled into the 20S complex, e.g., by recruiting HSP40 and the dimeric 10-kDa protein LC8; LC8, for example, could bind and stretch-out RSP3 dimers already present in the 12S precursor (Gupta et al., 2012; Wirschell et al., 2008). Immunofluorescence and immunoblotting-based quantification of epitope-tagged RS proteins indicates that one RS contains two copies each of RSP3, 4 and 6 in agreement with remodeling of the 12S precursor rather than its dimerization (Oda, 2017). The dimensions of the 12S complex (~28nm length and 20nm width) and of 20S spokes isolated from axonemes (50nm length and 25nm width, each based on negative stain) support the notion that more complex rearrangements are required to convert the 12S into the 20S complex (Diener et al., 2011). Both models assume that RSP3 and RSP4 present in a given 12S precursor remain associated during its conversion into the mature spokes.

To test further test this assumption, we took advantage of the pf1 mutant, which possesses the spoke stalks but lacks the heads, a defect which is complemented in pf1 × wild type zygotes possessing the missing RSP4 proteins (Luck et al., 1977). To test whether complementation occurs by addition of spoke heads to the residual pf1 spokes or de novo assembly of entire RSs, we mated pf1 to a strain expressing two tagged RSPs, one each as markers for the head and stalk. Tagged RSP4 amply incorporated into the pf1-derived flagella whereas the incorporation of tagged RSP3 was sparse. The pattern suggests that a complex encompassing RSP4 but not RSP3 is added onto the untagged spoke stalks in pf1 axonemes. This scenario would imply that RSP3 and RSP4 present in a given 12S complexes separate during the repair of the residual pf1 spokes.

A caveat is that in zygotes the tagged RSPs compete with the endogenous proteins for assembly into the RSs, e.g., pf1 × pf1 pf14 FP-RSP4 FP-RSP3 zygotes possess tagged and untagged RSP3 but only tagged RSP4. Even while tagged RSP3 and RSP4 fully rescued the corresponding single and double null mutants, a ~28-kD tag could still interfere with their performance during the formation of the 12S precursor, IFT transport, or assembly of the mature spokes. To test for such a bias, we mated wild-type gametes with regenerating flagella to the double-tag RSP strain and compared the signal strength of the donor flagella, assembled while cells exclusively possessed tagged RSP3 and RSP4, to that of the flagellar segments added to the regrowing wild-type flagella after cell fusion, when both tagged and untagged RSPs were available. While mNG-RSP4 was abundant in the newly formed flagellar segments of such zygotes, the mS-RSP3 signal was more variable in strength and often weak. The data suggest that cells preferred endogenous RSP3 to tagged RSP3 during de novo RS assembly. RSP3 binds to the axonemal microtubules via its N-terminal region and the presence of a large tag at the N-terminus could perturb this interaction potentially explaining both the underrepresentation of tagged RSP3 in flagella and the slow pace of RS repair in cells exclusively expressing tagged RSP3 (Oda et al., 2014).

Could the apparent bias against tagged RSP3 also explain its near absence during the repair of the stunted pf1 spokes? The signals representing incorporation of the tagged RSPs into wild-type derived cilia, which occurs by low frequency exchange of existing spokes, were weak but readily detectable including those of mS-RSP3. However, the signals representing tagged RSP3 remained exceedingly weak (but for the flagellar tips and proximal regions) in zygotic pf1 flagella when a large number of spokes is complemented. Further, the repair of pf1 spokes proceeds in a pronounced tip-to-base pattern while the de novo assembly of RSs in pf14 flagella (this study) or spoke-deficient pf27 flagella (Alford et al., 2013) is apparent along the entire length of the cilia. We therefore conclude that the repair of the pf1 axonemes occurs predominately by addition of spoke heads to the incomplete spokes rather than by replacement of the entire spokes.

Previous studies have shown that proteins in steady state flagella undergo turnover, but the exchange rate of the various axonemal substructures as well as the spatial distribution of such replacements remain largely unknown (Song and Dentler, 2001). We show incorporation of tagged RSPs into wild type-derived flagella indicating an exchange of RSs (or RS subunits) in full-length cilia. A C. reinhardtii flagellum contains ~2,200 RSs and based of the signal intensity of tagged RSPs in wild type-derived flagella, we estimate a low-level exchange at a rate of ~1 RSs/minute/flagellum. Higher rates of incorporation were observed at the flagellar base and tip. The signal resulting from the incorporation of tagged RSP4 into wild-type flagella was well above that representing tagged RSP3. Based on these data, we initially thought that the spoke head undergoes an increased rate of exchange during maintenance. Infrequently, we observed separation of tagged RSP3 and RSP4 inside flagella and the tagged proteins displayed distinct behaviors at the flagellar tip with RSP4 often dwelling for extended periods. However, critical testing of this hypothesis showed that the discrepancy in the exchange of the tagged RSPs could also result from differences between the FP tags and a bias against mS-RSP3 in the presence of the endogenous protein. Thus, it is unclear whether the proposed split of the 12S complex occurs only during the repair of head-less pf1 spokes or also during de novo RS assembly and axonemal maintenance by RS exchange.

4 Materials and Methods

4.1 Strains and Culture conditions

All strain were maintained in Minimal (M) medium (https://www.chlamycollection.org/methods/media-recipes) at 24°C with a light/dark cycle of 14/10 hours. The following strains were obtained from the Chlamydomonas Resource Center (https://www.chlamycollection.org/): CC-613 (pf14 mt−), CC-1032 (pf14 mt+), CC-1024 (pf1 mt+), CC-602 (pf1 mt−), CC-620 (nit1 nit2 mt+), and CC-621 (nit1 nit2 mt−).

4.2 Cloning and transformation

For C-terminal tagging of RSP4 with super folder GFP (sfGFP), RSP4 was amplified by PCR using the primers RSP4f (CGCCTCGAGATGGCGGCAGTGGACAGC) and RSP4r (CGCAGATCTGCTGCCGCCGCCGCTG) and a previously described genomic RSP4-GFP construct as a template (Oda et al., 2014). The cleaned PCR product was digested with Xho1 and BlgII, gel-purified, and ligated into the pBR25-sfGFP-sfGFP vector (Lechtreck, 2016) (Lechtreck, 2016) digested with Xho1 and BamH1. This placed the RSP4 CDS upstream of the gene encoding sfGFP. For N-terminal tagging of RSP4, the coding sequence was amplified using the primers RSP4-f-Bgl2 (CGCAGATCTGGCGGCAGCGGCGGCATGGCGGCAGTGGACAGCG) and RSP4-r-EcoR1 (GCGGAATTCCTACTCGTCCGCCTCGGCCTC) and ligated downstream of the mNeonGreen (mNG) gene using the pBR25-mNG-α-tubulin vector (Craft et al., 2015). For N-terminal tagging of RSP3, the RSP3 coding region was amplified from a RSP3 cDNA clone (Diener et al., 1990) using the primers RSP3f (CGCGGATCCATGGTGCAGGCTAAGGCGCA) and RSP3r (GCGGAATTCTTACGCGCCCTCCGCCTC). After digestion with BamH1 and EcoR1, the PCR fragment was gel-purified and ligated into the pBR25-mNeon-α-tubulin vector digested with the same enzymes. Derivatives were obtained by replacing the mNeon gene with genes encoding other FPs by restriction digest and ligation. Primers mS-f-XhoI (GCGCTCGAGATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAG) and mS-r-BamHI (CGCGGATCCCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC) were used to amplify mScarlet-I (mS) codon-adopted for expression in mammalian cells. For transformation, the plasmids were digested with Xba1 and Kpn1, the ble-RSP4-sfGFP and ble-mNeon-RSP3 cassettes were gel purified, and introduced into appropriate strains (CC-602 and CC-1032) by electroporation. Transformants were selected on zeocin plates (10 μg/ml), transferred to liquid medium, and analyzed for restoration of motility. Expression of FP-tagged RSPs was verified by TIRF microscopy and Western blotting. A strain expressing both RSP4-sfGFP and mCherry (mC)-RSP3 was obtained by mating the corresponding single rescue strains in CC-602 (RSP4-sfGFP pf1 mt−) and CC-1032 (mC-RSP3 pf14 mt+). The progeny was screened by TRIF microcopy for expression of GFP and mC and Western blotting was used to confirm the pf1 pf14 RSP4-sfGFP mC-RSP3 double mutant double rescue strain. The pf1 pf14 RSP4-sfGFP strain was isolated from the progeny of this cross. The pf1 pf14 mNG-RSP4 mScarlet-RSP3 strain was generated following the same strategy.

4.3 Flagellar isolation and Western blotting

For Western blot analyses, cells in 10 mM Hepes, 5 mM MgSO4, 4% sucrose (w/v) were deflagellated by the addition of dibucaine. After removing the cell bodies by two differential centrifugations, flagella were sedimented at 40,000 × g, 20 minutes, 4°C as previously described (Witman, 1986) Flagella were dissolved in Laemmli SDS sample buffer, separated on Mini-Protean TGX gradient gels (BioRad), and transferred electrophoretically to PVDF membrane. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight in the primary antibodies; secondary antibodies were applied for 90–120 minutes at room temperature. After addition of the substrate (Femtoglow; Michigan Diagnostics), chemiluminescent signals were documented using A BioRad Chemi Doc imaging system. The following primary antibodies were used in this study: rabbit anti-RSP6 (Williams et al., 1986), rabbit anti-RSP3 (Williams et al., 1989), rabbit anti-GFP (A-11122; ThermoFischer), mouse monoclonal anti-IFT172 (Cole et al., 1998) and mouse monoclonal anti-IC2 (King and Witman, 1990).

4.4 In vivo microscopy

Live imaging was performed on a Nikon eclipse Ti-U equipped with a 60× NA1.49 TIRF objective, 488-nm and 561-nm diode lasers (Spectraphysics), a dual view system (Photometrics), and an EMCCD camera (Andor iXon3). Simultaneous imaging of mS-RSP3 and mNG-RSP4 during transport required optimal settings of our manual TIRF system and bleaching of the flagella prior to the recording in a way that removed most RSP4-mNG signal while preserving sufficient amounts of fluorescent mS-RSP3. Data were collected using the Nikon Elements software package and exported into Fiji for further analysis including kymography and frame extraction. The camera was set to a readout mode of 10MHz and an EM gain multiplier of 150–160× avoiding pixel saturation and ensuring a high dynamic range (http://www.andor.com/learning-academy/dynamic-range-and-emccds-uncovering-the-facts). Contrast and brightness were adjusted in Fiji and in Photoshop and all figures were prepared in Illustrator (Adobe). Specimen preparation, TIRF imaging, and data analysis have been described in detail in (Lechtreck, 2013) and (Lechtreck, 2016).

4.5 Flagellar regeneration and mating experiments

For flagellar regeneration experiments, 0.5 M acetic acid was rapidly added to cells in fresh M medium under stirring (1,200 rpm) to reach a pH of ~4.25. After ~45s, KOH (0.25 M) was added to neutralize the solution (pH ~6.8), the cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in M medium and either used directly or stored on ice until needed. During regeneration, cells were incubated on a shaker in bright light at room temperature. Specimens for live imaging were prepared 25 minutes after the pH shock and later.

For mating experiments, cells were grown in bright light on M plates for ~9–12 days and then transferred to dim light for 2–3 days (see above for conditions). The evening before the experiment, cells were resuspended in 6–10 ml M-N medium (7–10 ml/plate) and incubated overnight in constant light with agitation; agitation was omitted for the RS mutants, which better assembled flagella without shaking. In the morning, cells were transferred to 1/5M-N supplemented with 10 mM Hepes, pH7 and incubated for an additional ~2–6 hours. Gametes of opposite mating types were mixed in a microcentrifuge tube and samples for imaging were taken over a period of ~5 minutes to several hours. In some experiments, db-cAMP was added to the mixed gametes to promote cell fusion (Pasquale and Goodenough, 1987).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jacek Gaertig (University of Georgia) for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM110413 to K.L.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- IFT

intraflagellar transport

- FP

fluorescent protein

- mC

mCherry

- mNG

mNeonGreen

- mS

mScarlet-I

- RS

radial spoke

- RSP

radial spoke protein

- sfGFP

superfolder GFP

References

- Bhogaraju S, Cajanek L, Fort C, Blisnick T, Weber K, Taschner M, Mizuno N, Lamla S, Bastin P, Nigg EA, Lorentzen E. Molecular basis of tubulin transport within the cilium by IFT74 and IFT81. Science. 2013;341:1009–1012. doi: 10.1126/science.1240985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindels DS, Haarbosch L, van Weeren L, Postma M, Wiese KE, Mastop M, Aumonier S, Gotthard G, Royant A, Hink MA, Gadella TW., Jr mScarlet: a bright monomeric red fluorescent protein for cellular imaging. Nat Methods. 2017;14:53–56. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DG, Diener DR, Himelblau AL, Beech PL, Fuster JC, Rosenbaum JL. Chlamydomonas kinesin-II-dependent intraflagellar transport (IFT): IFT particles contain proteins required for ciliary assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans sensory neurons. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:993–1008. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft JM, Harris JA, Hyman S, Kner P, Lechtreck KF. Tubulin transport by IFT is upregulated during ciliary growth by a cilium-autonomous mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:223–237. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201409036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry AM, Williams BD, Rosenbaum JL. Sequence analysis reveals homology between two proteins of the flagellar radial spoke. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3967–3977. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener DR, Ang LH, Rosenbaum JL. Assembly of flagellar radial spoke proteins in Chlamydomonas: identification of the axoneme binding domain of radial spoke protein 3. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:183–190. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener DR, Curry AM, Johnson KA, Williams BD, Lefebvre PA, Kindle KL, Rosenbaum JL. Rescue of a paralyzed-flagella mutant of Chlamydomonas by transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5739–5743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener DR, Yang P, Geimer S, Cole DG, Sale WS, Rosenbaum JL. Sequential assembly of flagellar radial spokes. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2011;68:389–400. doi: 10.1002/cm.20520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutcher SK. Flagellar assembly in two hundred and fifty easy-to-follow steps. Trends Genet. 1995;11:398–404. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowkes ME, Mitchell DR. The role of preassembled cytoplasmic complexes in assembly of flagellar dynein subunits. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2337–2347. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.9.2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer A, Hjeij R, Loges NT, Edelbusch C, Jahnke C, Raidt J, Werner C, Wallmeier J, Grosse-Onnebrink J, Olbrich H, Cindric S, Jaspers M, Boon M, Memari Y, Durbin R, Kolb-Kokocinski A, Sauer S, Marthin JK, Nielsen KG, Amirav I, Elias N, Kerem E, Shoseyov D, Haeffner K, Omran H. Immunofluorescence Analysis and Diagnosis of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia with Radial Spoke Defects. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53:563–573. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0483OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Diener DR, Sivadas P, Rosenbaum JL, Yang P. The versatile molecular complex component LC8 promotes several distinct steps of flagellar assembly. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:115–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Rosenbaum JL. Polarity of flagellar assembly in Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1605–1611. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Witman GB. Localization of an intermediate chain of outer arm dynein by immunoelectron microscopy. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19807–19811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozminski KG, Johnson KA, Forscher P, Rosenbaum JL. A motility in the eukaryotic flagellum unrelated to flagellar beating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5519–5523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck KF. In vivo Imaging of IFT in Chlamydomonas Flagella. Methods Enzymol. 2013;524:265–284. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397945-2.00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck KF. IFT-Cargo Interactions and Protein Transport in Cilia. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:765–778. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck KF. Methods for Studying Movement of Molecules Within Cilia. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1454:83–96. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3789-9_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre PA, Silflow CD. Chlamydomonas: the cell and its genomes. Genetics. 1999;151:9–14. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck D, Piperno G, Ramanis Z, Huang B. Flagellar mutants of Chlamydomonas: studies of radial spoke-defective strains by dikaryon and revertant analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:3456–3460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T. Three-dimensional structural labeling microscopy of cilia and flagella. Microscopy (Oxf) 2017;66:234–244. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/dfx018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T, Yanagisawa H, Yagi T, Kikkawa M. Mechanosignaling between central apparatus and radial spokes controls axonemal dynein activity. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:807–819. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale SM, Goodenough UW. Cyclic AMP functions as a primary sexual signal in gametes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2279–2292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazour GJ, Agrin N, Leszyk J, Witman GB. Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:103–113. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigino G, Bui KH, Maheshwari A, Lupetti P, Diener D, Ishikawa T. Cryoelectron tomography of radial spokes in cilia and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:673–687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigino G, Geimer S, Lanzavecchia S, Paccagnini E, Cantele F, Diener DR, Rosenbaum JL, Lupetti P. Electron-tomographic analysis of intraflagellar transport particle trains in situ. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:135–148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200905103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigino G, Ishikawa T. Axonemal radial spokes: 3D structure, function and assembly. Bioarchitecture. 2012;2:50–58. doi: 10.4161/bioa.20394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperno G, Huang B, Luck DJ. Two-dimensional analysis of flagellar proteins from wild-type and paralyzed mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:1600–1604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.4.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperno G, Mead K. Transport of a novel complex in the cytoplasmic matrix of Chlamydomonas flagella. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4457–4462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Diener DR, Geimer S, Cole DG, Rosenbaum JL. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) cargo: IFT transports flagellar precursors to the tip and turnover products to the cell body. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:255–266. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasala BA, Barrera DJ, Ng J, Plucinak TM, Rosenberg JN, Weeks DP, Oyler GA, Peterson TC, Haerizadeh F, Mayfield SP. Expanding the spectral palette of fluorescent proteins for the green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J. 2013 doi: 10.1111/tpj.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Lambert GG, Chammas A, Ni Y, Cranfill PJ, Baird MA, Sell BR, Allen JR, Day RN, Israelsson M, Davidson MW, Wang J. A bright monomeric green fluorescent protein derived from Branchiostoma lanceolatum. Nat Methods. 2013;10:407–409. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EF, Yang P. The radial spokes and central apparatus: mechano-chemical transducers that regulate flagellar motility. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;57:8–17. doi: 10.1002/cm.10155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Dentler WL. Flagellar protein dynamics in Chlamydomonas. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29754–29763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschner M, Mourao A, Awasthi M, Basquin J, Lorentzen E. Structural basis of outer dynein arm intraflagellar transport by the transport adaptor protein ODA16 and the intraflagellar transport protein IFT46. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:7462–7473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.780155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan KK, Song K, Alford LM, Sale WS, Dymek EE, Smith EF, Hennessey T, Joachimiak E, Urbanska P, Wloga D, Dentler W, Nicastro D, Gaertig J. FAP206 is a microtubule-docking adapter for ciliary radial spoke 2 and dynein c. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:696–710. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanadha R, Hunter EL, Yamamoto R, Wirschell M, Alford LM, Dutcher SK, Sale WS. The ciliary inner dynein arm, I1 dynein, is assembled in the cytoplasm and transported by IFT before axonemal docking. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2014;71:573–586. doi: 10.1002/cm.21192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BD, Mitchell DR, Rosenbaum JL. Molecular cloning and expression of flagellar radial spoke and dynein genes of Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BD, Velleca MA, Curry AM, Rosenbaum JL. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the Chlamydomonas gene coding for radial spoke protein 3: flagellar mutation pf-14 is an ochre allele. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:235–245. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirschell M, Zhao F, Yang C, Yang P, Diener D, Gaillard A, Rosenbaum JL, Sale WS. Building a radial spoke: flagellar radial spoke protein 3 (RSP3) is a dimer. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:238–248. doi: 10.1002/cm.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witman GB. Isolation of Chlamydomonas flagella and flagellar axonemes. Methods Enzymol. 1986;134:280–290. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)34096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren KN, Craft JM, Tritschler D, Schauer A, Patel DK, Smith EF, Porter ME, Kner P, Lechtreck KF. A differential cargo-loading model of ciliary length regulation by IFT. Curr Biol. 2013;23:2463–2471. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa HA, Mathis G, Oda T, Hirono M, Richey EA, Ishikawa H, Marshall WF, Kikkawa M, Qin H. FAP20 is an inner junction protein of doublet microtubules essential for both the planar asymmetrical waveform and stability of flagella in Chlamydomonas. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:1472–1483. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-08-0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Diener DR, Yang C, Kohno T, Pazour GJ, Dienes JM, Agrin NS, King SM, Sale WS, Kamiya R, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB. Radial spoke proteins of Chlamydomonas flagella. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1165–1174. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.