INTRODUCTION

An escalating volume of injury prevention research over the past half century has dramatically increased our understanding of the risk and protective factors associated with injury and violence, and the efficacy of interventions for addressing these risk factors across the social ecology.1,2 However, this increased understanding has not resulted in widespread adoption and implementation of evidence-based and evidence-informed interventions, and countries such as the USA are still experiencing increased rates of injury and violence morbidity and mortality.3 The disassociation between our knowledge of injury causation and effectiveness of our efforts to reduce injury has been discussed in the injury prevention literature as the ‘research to practice gap’ and has focused primarily on the disconnect between evidence-based programmes and their wide-scale adoption.4

This research to practice gap evident in injury prevention is simply a special case of the more generic challenge evident throughout the public health field. Disciplines and approaches such as translation research and implementation science have emerged to help bridge this gap and facilitate the spread of evidence-based prevention programmes.4–7 This has included the development of tools, resources and methods to support and engage communities in the implementation of evidence-based injury and violence prevention programmes.7–10 However, translation research and implementation science have been developed largely within the existing paradigms of laboratory and clinical research.11 Some in the field of public health have begun to question whether the ‘research to practice gap’ is truly limited to the uptake of evidence-based programmes or if it may actually be a much broader disconnect requiring more integrated, multifaceted approaches to knowledge generation and application.3 Similarly, population health research is now recognising that efforts to achieve community-level well-being are more likely to be effective when they focus on systems change, and when they are not limited to single-sector, isolated, narrowly circumscribed interventions.12–15 Thus, the challenge that has arisen is that many of the approaches that have been developed and are currently used in service to bridge research and practice (or facilitate the uptake of evidence-based interventions) are poorly matched to the task of supporting, evaluating and learning from the complex, multifaceted, systems-focused efforts that may be particularly promising for achieving population-level impact.16,17

While there are a number of reasons why attempts at scale-up of evidence-based programmes often fail (eg, lack of adequate funding and resources, lack of attention to implementation capacity and training),7 a fundamental problem is that programmes are embedded within systems, and it is the overall system structure, rather than the individual embedded programmes alone, that is often the primary driver of the wellbeing indicator of interest.3,15 Although systems and system-related factors (eg, stakeholder relationships, organisational policies, community values and preferences, data sharing and access) can be barriers to scale-up and implementation of delimited prevention programmes, they can also provide leverage to achieve more wide-reaching, sustainable impact. A systemic approach recognises that the systems in which prevention efforts are being implemented must be known, understood, and actively coordinated and managed. It prioritises generating and applying data and knowledge for continuous learning and improvement. Together, these elements of a systemic approach offer great promise for increasing the responsiveness, reach and sustainability of prevention efforts to more effectively address complex public health challenges such as injury and violence prevention, and to achieve population-level impact.3,18,19

While systems science is a well-developed discipline with a long history of activity within the fields of engineering, physics, mathematics, computer science and the humanities,20–22 its influence on the scholarly practice of medicine and public health is minimal.13,16,18,23 Where systems thinking is evident in health literature, it is generally in the form of theoretical discussion rather than practical application.15 This observation is particularly true of the systemic approach to injury prevention and control. While it has been conceptualised,24 there are few actual examples of this approach being used in practice. To our knowledge, there are no previously published studies that have critiqued an application of the systemic approach to injury prevention in a way that allows for learning and inspires further development.

In this paper, we use examples from some of the many promising ‘cradle-to-career’ efforts taking place around the country, such as Harlem Children’s Zone (http://hcz.org/) and Promise Neighborhoods (https://innovation.ed.gov/what-we-do/parental-options/promise- neighborhoods-pn/), to highlight specific features of a systemic approach that help achieve population-level impact on key social and public health outcomes, including risk and protective factors tied to injury and violence. Our examples were drawn from conversations with local leaders who recognised these features in their work and were willing to reflect on their experiences. In providing concrete examples, we aim to encourage a better understanding of systemic injury prevention, illustrate the strengths and challenges inherent in this approach, and stimulate further debate among injury prevention scholar-practitioners.

HARLEM CHILDREN’S ZONE AND PROMISE NEIGHBORHOODS

The federal Promise Neighborhoods Program, administered by the U.S. Department of Education, aims to improve the educational and developmental outcomes of children and youth in the nation’s most distressed communities. In each Promise Neighborhood, partner organisations develop a continuum of educational programmes and family and community supports. This approach, inspired by the success of the Harlem Children’s Zone (HCZ), addresses critical systems and upstream antecedents of injury and violence, such as coordinating resources and services within communities, strengthening youths’ connection and commitment to school, and fostering family support and connectedness.25–27 HCZ began in 1997 as a one-block pilot designed to provide children and their families ‘cradle-to-career’ supports to break the cycle of intergen-erational poverty and grew to encompass 97 blocks over the next 10 years. In 2016, HCZ reported a 96% college acceptance rate across its programmes and 100% of children in its pre-kindergarten sites tested school-ready.28

The Promise Neighborhoods described below, as well as other Promise Neighborhoods around the country, are also working to build pipelines of support that achieve better results at scale for children and families (for the Promise Neighborhoods’ Results Framework, see https://promiseneighborhoods.ed.gov/content/results-framework). Promise Neighborhoods focus their efforts and track progress in 10 areas: school readiness, academic proficiency, successful transition from middle grades to high school, high school graduation, college and career readiness, healthy students, safe communities, stable communities, supportive communities and 21st Century learning tools.29 There are also some Promise Neighborhoods that address injury and violence-related outcomes even more directly, such as the Mi Escuelita Therapeutic Preschool in the Chula Vista Promise Neighborhood (https://southbaycommunityservices.org/index.php/services/90-mi-escuelita-thera-peutic-preschool), which provides specialised services to help children heal from violence-related trauma while building a foundation for their academic success.

FEATURES OF A SYSTEMIC APPROACH

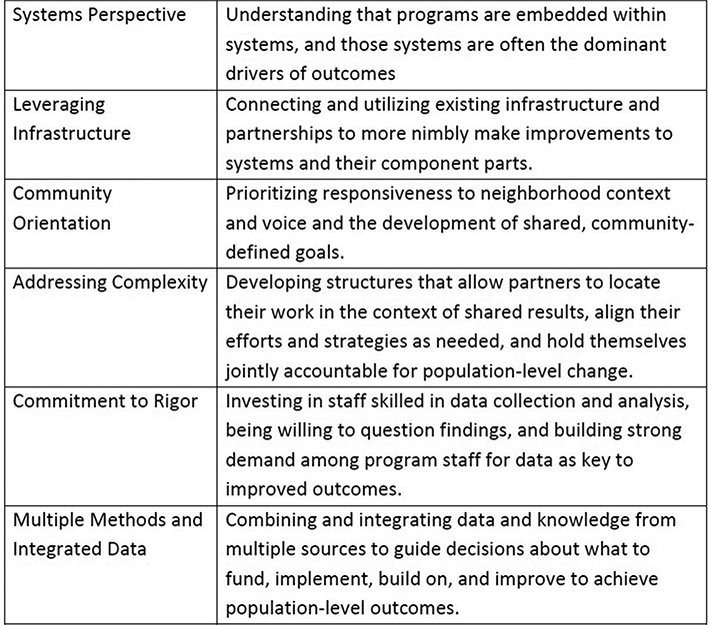

Promise Neighborhoods are not driven by conceptions of programme ‘scale up’ and replication that are common in current translation and implementation science approaches. In fact, the key features that distinguish them from more traditional evidence-based programme scale up and replication efforts is the extent to which they attend to the improvement and strengthening of systems in order to drive population-level changes and impact versus fidelity to specific circumscribed models or programmes. The key features of a systemic approach to prevention that are emerging from Promise Neighborhoods are described in more detail below and include a systems perspective, strong infrastructure, community orientation, ability to deal with complexity, commitment to rigour and use of multiple methods and data for decision-making, continuous learning and improvement.

The key features of a systemic approach, and the conclusions we have identified, are drawn from conversations with local leaders and from the extensive work that the Center for the Study of Social Policy has done, over the years, with Promise Neighbourhood sites. We have put together and synthesised this information to enable us to offer practical insights about how each feature is playing out in the context of cradle-to-career work, and what systemic change efforts look like in the context of cradle-to-career approaches to health and well-being.

Systems perspective

A foundational aspect of achieving population-level change is taking account of the power of systems to determine results (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Features of a systemic approach: lessons learned from Harlem Children’s Zone and Promise Neighborhoods.

Much of what makes interventions effective is so often undermined by the systems within which they must operate, especially when the intervention is expanded to reach large numbers.30–32 Moreover, shifting the focus away from systems merely as facilitators or barriers to interventions and towards understanding systems as priority drivers of shared outcomes of interest poses great potential for achieving broad-scale impact. For example, East-side Promise Neighborhood (EPN, http://eastsidepromise.org/epn-schools/), with San Antonio Independent School District (SAISD) as its lead educational partner, created a learning laboratory for teachers and administrators on six target campuses with the intention of integrating the most promising pieces of work across the district in order to create change beyond just singular pilot sites, but at the systems level. Through this partnership, SAISD developed and introduced a comprehensive plan for STEM education, redesigning the curriculum to more purposefully align STEM content from early childhood through high school and integrate Science/ Math and English Language Arts/Writing/ Social Studies instruction. This work emphasised building STEM proficiency in students while also addressing state standards in all core subjects, increasing teacher capacity in STEM, and strengthening pedagogy and technology skills. Based on strong results at the six target campuses, the district adopted a STEM curriculum across all grades, resulting in a more coherent STEM pipeline for all students moving through the public education system. EPN leaders point to strong relationships with district staff, codified agreements at the school board level, and the ability to demonstrate clear value as essential for engaging the school system both as an object of change strategies and as a driver to achieve broad-scale impact. Because EPN is working to document both its strategies and results, most recently through the use of case studies, this series of interventions lends itself to creating knowledge that can be useful to others who are looking to understand and engage in changes to systems within their own contexts.

Role of infrastructure

The importance of infrastructure and partnerships for managing and coordinating change efforts has been well documented in public health and social service domains.33–35 Place-based, systems-focused initiatives, with their emphasis on partnerships, are often able to act effectively when siloed programmes cannot. These initiatives are supported by an infrastructure that allows them to continually evolve in response to data that demonstrate where outcomes are being achieved and where improvements or additions are needed. For example, HCZ conducted a large-scale household survey36 and found that a third of children tested in the neighbourhood under the age of 13 had asthma (which is more than four times the national average). In response, HCZ engaged a wide range of partners to mobilise a collection of interventions that ranged from strongly evidence-based to evidence informed. Partners mobilised and each played a role in working towards reducing asthma among children in the neighbourhood. Harlem Hospital, for example, provided medical care including regular home visits, while the Columbia School of Public Health helped support ongoing data collection to track asthma outcomes over time. The City Health Department and Columbia Urban Planning Programme provided technical assistance on the environmental factors contributing to the issue, and Volunteers of Legal Services provided relevant legal assistance. Finally, the deep ties HCZ had developed over the years with families in the community proved to be a critical facilitator in implementing this new asthma prevention strategy. When HCZ reached out to neighbourhood families with guidance on how to reduce their children’s asthma, it was these existing relationships and shared history that allowed the families to trust the new Harlem Children’s Zone Asthma Initiative enough to take action based on the advice they got. The impact of this comprehensive, coordinated effort that leveraged existing partnerships and infrastructure was substantial and included dramatic decreases in hospitalisations, emergency room visits and school absences36,37.

Importance of a community orientation

There has been increasing focus in public health and related fields on the importance of understanding and addressing aspects of communities and environments (vs individuals) that contribute to poor social and health outcomes.30,38 In order to be fully responsive to its neighbourhood context and set shared, community-defined goals, EPN initiated a target setting process that included 13 community-wide meetings with over 200 individuals from the broader community and 10 small-group meetings with over 50 individuals from specific workgroups or partnerships. During these meetings, partners set targets for each of the 10 Promise Neighborhoods focus areas. In setting targets, partners sought to address the question ‘What do we want to see our children and families achieve?’ In some cases, this process resulted in target ranges to allow for the ‘aspirational’ expectations of the community. In other instances, EPN and its community partners determined that single annual targets were realistic, satisfactory and achievable based on available baseline data and the proposed continuum of solutions. While EPN implemented the target setting process at the population level, it was also simultaneously implementing a target setting process at the programme level, following a Results Based Accountability framework.39 Partners were asked to set targets for programmes through the end of the grant period. EPN then rolled up the programme targets against the population targets; in instances where the programme targets did not meet a target range, EPN went back to its partnership to see which programmes could be strengthened, or what additional programmes could be implemented to address a target gap. Observers noted that this approach gave a sense of urgency to the process, engaged both community members and professional partners in productive exchanges about what was both realistic and feasible, and pushed everyone involved to orient the effort around community input and priorities.

Dealing with complexity

Simple interventions, be they a pill, a curriculum or a piece of software, present a relatively straightforward challenge: how do you get people to use it as designed, and how do you measure its impact on the targeted individuals? Complex interventions, by contrast, require a different mindset. The complexity that characterises so many of the most promising interventions targeted at population-based change means they cannot be implemented or assessed with the tools that were designed around individual programmes.16 A number of Promise Neighborhoods dealt with this complexity by adding a new layer to their approach; in addition to managing the performance of individual partners, lead agencies introduced opportunities for clusters of programme and service providers to think and act together, with an eye to Promise Neighborhood’s population-level results. Indianola Promise Community (IPC, http://deltahealthalliance.org/project-category/indianola-promise-community/), for example, developed separate flow charts for program-level and population-level accountability as a way to standardise and institutionalise both levels of work. At the programme level, the focus is on obtaining usable performance data and reviewing these data on a monthly basis with the relevant staff and partners. The process outlines specific steps related to data delivery and reporting, data analysis, internal and external meetings and includes a follow-up meeting to discuss progress on any action items identified. At the population level, IPC convenes partners across the entire continuum of services in addition to holding quarterly meetings for staff and partners working in five areas: early childhood, community, parent engagement, school/academic and college and career. These meetings helped Promise partners locate their work in the context of a shared result, align their efforts as needed and hold themselves jointly accountable for population-level change.

Commitment to rigour

The commitment to accessing, analysing and using reliable data is essential for high-quality implementation and evaluation. The Promise Neighborhoods that embraced this approach had several characteristics in common: they all invested resources in dedicated data staff with the appropriate training and experience, they displayed a willingness to question their own findings and they built strong demand for data among programme staff. In several cases, this commitment to rigour resulted in changes to data collection processes. For example, when Promise Neighborhood leaders suspected that community members might be over-reporting on a particular measure, they adjusted their approach so that community surveys were initiated by a fellow resident (to gain access and establish trust) but conducted by an outside partner (to reduce concerns about privacy). As a result, they were able to craft more reliable narratives about where data came from, what it measured and what it meant.

Using multiple methods and data sources for decision-making, continuous learning and improvement

The strongest evidence to guide decisions about which investments to fund, implement and build on, and how to improve outcomes, comes from combining and integrating what we learn and analyse from multiple sources.40 These multiple sources include experimental evidence; real-time knowledge from practice and lived experience; studies of implementation and dissemination; basic and social science research examining causal connections; analyses that combine theory, experience and other empirical data; and findings culled from the proliferating digital infrastructure. At the HCZ, data reviews are held several times a year and entail close examination of individual cases to shed light on the effectiveness of its many strategies. Staff from all parts of the organisation gather, usually to review the case notes describing several students, who may be having particular difficulty, or whose troubles reflect a broader problem, in order to reflect on what systematic changes might be made and how programme staff might be better supported. HCZ programme leaders participate in these data review meetings, led by Quality Assurance and Performance Management teams, to ensure that programmes are implemented effectively and continually improved. Thus, HCZ data review process functions as both an accountability check and as an opportunity to share best practices, collectively solve problems and improve outcomes.41

Northside Achievement Zone (NAZ; http://northsideachievement.org/), the Promise Neighborhood in Minneapolis, offers another example of skilled partners that have figured out how to combine evidence from multiple sources in creative ways to inform decision-making. As a first step in its design, NAZ searched for relevant evidence-based programmes, followed by a well-defined process for adapting interventions and developing new ‘solutions’ tailored to the local area, a predominantly African-American community with considerable resident assets but also high poverty and low rates of school success. To adopt and embed the learning from its own experience and from elsewhere, NAZ leaders invented a process they call the ‘NAZ Seal of Effectiveness’. It aims to build on the best knowledge available by adapting existing models or creating new solutions. A panel of local leaders, residents, researchers and programme experts, augmented by national consultants in the subject area, synthesise all they know from research and experience into an intervention that NAZ and its partners will put into practice. The essential ingredients are specified, along with indicators that will show whether the ingredients are used appropriately. Implementation is carefully tracked to assess evidence of impact as well as fidelity to essential ingredients. A NAZ ‘Results Roundtable’ meets regularly, using assessment data to determine if the intervention is being implemented as intended, having the desired effect or needs to be adapted to increase the chances of success. NAZ is establishing roundtables for several components of its ‘cradle-to-career’ pipeline, with the goal that this rigorous and adaptive oversight will ultimately apply to each segment of the service continuum. This process also fosters accountability in a way that shifts away from focusing on the achievement of predetermined results on a predetermined plan, and toward demonstrating the ability to achieve results in complex, dynamic environments. NAZ’s Seal of Effectiveness also illustrates how it is possible to deeply involve stakeholders in knowledge generation and to codify their process in ways that can become gener-alisable knowledge.

DISCUSSION

Despite increasing calls for a more purposeful consideration of the ways in which systems drive public health outcomes,15,42 there have been few, if any, examples of the application of a systemic approach to injury prevention in the current literature. This paper presents efforts taken by HCZ and Promise Neighborhoods to move beyond the ‘scale up’ of evidence-based programmes and towards a more systemic approach to prevention of upstream factors linked to injury and violence outcomes. This approach, focused on the processes that facilitate and optimise the larger systems in which interventions, individuals, families and communities are embedded, provides opportunities for increasing the responsiveness, reach, effectiveness and sustainability of prevention efforts. It provides great promise for addressing complex public health challenges such as injury and violence prevention in ways that may lead to greater population-level impact.

The features of a systemic approach to prevention that have emerged from HCZ and Promise Neighborhoods that are presented here (a systems perspective, strong infrastructure, community orientation, ability to deal with complexity, commitment to rigour, and use of multiple methods and data for continuous learning and improvement) are not intended to serve as a comprehensive and exhaustive list of elements necessary for engaging in meaningful, effective systems change. Rather, they provide the field of injury prevention with an emerging set of considerations for initiating and sustaining systems-level changes and provide a ‘starting point’ for further consideration, application and refinement among injury prevention scholars and practitioners as efforts towards systems change grow.

It is important to acknowledge that while a systemic approach to prevention poses great potential for creating population level change, it is not without challenges. First, this kind of an approach requires adequate time, effort and resources to build trust, establish shared accountability, invest in infrastructure and reinforce norms of collaboration versus competition between key partners. This necessitates ‘calibrating’ expectations among key stakeholders and garnering their buy-in and investment in the process.43 Also, there is much we still have to learn about the ways in which systems function and their impact on injury and violence-related outcomes. While there is a relatively robust literature on the theory of systems thinking, complexity science and other related systems-ori- ented approaches,18,20–22 there are few concrete examples of their application in public health, and injury and violence prevention more specifically. Finally, there are also likely other features of a systemic approach to prevention that have not yet fully emerged from HCZ or Promise Neighborhoods, but may be critical to achieving population-level impact for injury and violence prevention. For example, identifying and understanding the ‘essential elements’ that account for the success of prevention initiatives allows for a critical level of flexibility that is likely to be essential for integrating prevention approaches across broad-scale systems.44 Once identified, these essential elements can be embedded within broad-reaching systems more easily than traditional evidence-based programmes, as they can be re-bundled to fit new populations and unique circumstances while still maintaining those characteristics most closely tied to effectiveness.

The field of injury and violence prevention is rich in many critical scientific and practice-based skills and experiences that have the potential to grow and improve our understanding of the value of a systemic approach to prevention. From developing innovative and rigorous research methodologies, to fostering meaningful and sustainable collaborations and partnerships, to using data in strategic planning and continuous improvement and evaluation activities, the field of injury and violence prevention is well positioned to build on the lessons learnt from HCZ and Promise Neighborhoods to revolutionise the way we approach complex social and public health issues to achieve population-level impact.

Acknowledgments

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Collaborators Roderick McClure.

Contributors CT: organised overall writing of the manuscript. Contributed substantial content knowledge and expertise. Co-drafted ‘Harlem Children’s Zone and Promise Neighborhoods’ and ‘Features of a Systemic Approach’ sections. LBS: contributed content knowledge and expertise. Co-drafted ‘Harlem Children’s Zone and Promise Neighborhoods’ and ‘Features of a Systemic Approach’ sections. NW: drafted Introduction and Discussion sections of the manuscript. Edited all sections of the manuscript. LSS: edited all sections of the manuscript and contributed to the Introduction and Discussion sections.

Disclaimer The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, et al. The world report on violence and health. The Lancet 2002;360:1083–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sumner SA, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, et al. Violence in the United States: status, challenges, and opportunities. JAMA 2015;314:478–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanson DW, Finch CF, Allegrante JP, et al. Closing the gap between injury prevention research and community safety promotion practice: revisiting the public health model. Public Health Rep 2012;127:147–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saul J, Wandersman A, Flaspohler P, et al. Research and action for bridging science and practice in prevention. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41:165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41(3– 4):171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA 2008;299:211–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, et al. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wandersman A, Imm P, Chinman M, et al. Getting to outcomes: a results-based approach to accountability. EvalProgram Plann 2000;23:389–95. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinman M, Hunter SB, Ebener P, et al. The getting to outcomes demonstration and evaluation: an illustration of the prevention support system. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41:206–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Kuklinski MR. Communities that care. Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, et al. National Institutes of Health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1274–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreuter MW, De Rosa C, Howze EH, et al. Understanding wicked problems: a key to advancing environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav 2004;31:441–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leischow SJ, Best A, Trochim WM, et al. Systems thinking to improve the public’s health. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:S196–S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keyes KM, Galea S. Population health science: Oxford University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet 2017;390:2602–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luke DA, Stamatakis KA. Systems science methods in public health: dynamics, networks, and agents. Annu Rev Public Health 2012;33:357–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gates EF. Making sense of the emerging conversation in evaluation about systems thinking and complexity science. Eval Program Plann 2016;59:62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trochim WM, Cabrera DA, Milstein B, et al. Practical challenges of systems thinking and modeling in public health. Am J Public Health 2006;96:538–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters DH. The application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking? Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meadows DH. Thinking in systems: a primer: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Checkland P Systems thinking, systems practice, 1981.

- 22.Checkland P, Thinking S. Rethinking management information systems: an interdisciplinary perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green LW. Public health asks of systems science: to advance our evidence-based practice, can you help us get more practice-based evidence? Am J Public Health 2006;96:406–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClure RJ, Mack K, Wilkins N, et al. Injury prevention as social change. Inj Prev 2016;22:226–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobbie W, Fryer RG, Fryer G Jr. Are high-quality schools enough to increase achievement among the poor? Evidence from the Harlem Children’s Zone. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2011;3:158–87. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkins N, Tsao B, Hertz M, et al. Connecting the dots: an overview of the links among multiple forms of violence, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkins NJ, Myers L, Kuehl T, et al. Connecting the dots: state health department approaches to addressing shared risk and protective factors across multiple forms of violence. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harlem children’s zone results. 2016. http://hcz.org/ results/

- 29.Comey J Measuring performance: a guidance document for Promise Neighborhoods on collecting data and reporting results, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health 2010;100:590–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoenwald SK, Hoagwood K. Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: what matters when? Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:1 190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson DD. A conceptual framework for transferring research to practice. J Subst Abuse Treat 2002;22:171–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frieden TR. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. Am J Public Health 2014;104:17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavinghouze SR, Snyder K, Rieker PP. The component model of infrastructure: a practical approach to understanding public health program infrastructure. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e14–e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pringle JL, Edmondston LA, Holland CL, et al. The role of wrap around services in retention and outcome in substance abuse treatment: findings from the wrap around services impact study. Addict Disord Their Treat 2002;1:109–18. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholas S, Hutchinson V, Ortiz B, et al. Reducing childhood asthma through community-based service delivery—New York City, 2001–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schorr LB. Broader evidence for bigger impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 2012:50–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinderhughes H, Davis R, Williams M. Adverse community experiences and resilience: a framework for addressing and preventing community trauma: Prevention Institute, 2016:5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedman M Trying hard is not good enough: how to produce measurable improvements for customers and communities. 3rd edn: PARSE Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shonkoff JP, Radner JM, Foote N. Expanding the evidence base to drive more productive early childhood investment. Lancet 2017;389:14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCarthy K, Jean-Louis B. Harlem children’s zone. Washington, D.C: Center for the Study of Social Policy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galea S On adopting solutions to improve population health: do we have the political will? Health Educ Behav 2016;43:621–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.A developmental pathway for achieving promise neighborhoods results: policy Link. 2014.

- 44.Better-evidence for decision makers. Washington, DC: Center for the Study for Social Policy, 2016. [Google Scholar]