Abstract

Critical regulation of bile acid (BA) pool size and composition occurs via an intensive molecular crosstalk between the liver and gut, orchestrated by the combined actions of the nuclear Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and the enterokine fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) with the final aim of reducing hepatic BA synthesis in a negative feedback fashion. Disruption of BA homeostasis with increased hepatic BA toxic levels leads to higher incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). While native FGF19 has anti-cholestatic and anti-fibrotic activity in the liver, it retains peculiar pro-tumorigenic actions. Thus, novel analogues have been generated to avoid tumorigenic capacity and maintain BA metabolic action. Here, using BA related Abcb4−/− and Fxr−/− mouse models of spontaneous hepatic fibrosis and HCC, we explored the role of a novel engineered variant of FGF19 protein, called FGF19-M52, which fully retains BA regulatory activity but is devoid of the pro-tumoral activity. Expression of the BA synthesis rate-limiting enzyme Cyp7a1 is reduced in FGF19-M52-treated mice compared to the GFP-treated control group with consequent reduction of BA pool and hepatic concentration. Treatment with the non-tumorigenic FGF19-M52 strongly protects Abcb4−/− and Fxr−/− mice from spontaneous hepatic fibrosis, cellular proliferation and HCC formation in terms of tumor number and size, with significant reduction of biochemical parameters of liver damage and reduced expression of several genes driving the proliferative and inflammatory hepatic scenario. Our data bona fide suggest the therapeutic potential of targeting the FXR-FGF19 axis to reduce hepatic BA synthesis in the control of BA-associated risk of fibrosis and hepatocarcinoma development.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common malignancy and the third most frequent cause of cancer-related death1. The lack of effective therapeutic options makes the quest for novel putative treatment strategies of paramount importance. The gut-liver axis homeostasis relies on a tight control of bile acid (BA) levels in order to avoid BA overload that is critical in the pathogenesis of hepatic diseases.

BAs are the end products of cholesterol catabolism, synthesized in the liver and released into the small intestine after meal ingestion. BA production and circulation are tightly regulated via the nuclear receptor, farnesoid X receptor (FXR). In the liver, FXR reduces conversion of cholesterol to BAs by downregulating the rate limiting enzyme of BA synthesis cytochrome P450 A1 (CYP7A1), via the small heterodimer partner (SHP). Moreover, FXR promotes hepatic bile secretion by increasing the expression of crucial BA transporters. In the enterocytes, BA-bound FXR induces the transcription of the fibroblast growth factor FGF15/19 (mouse and human, respectively), an enterokine secreted into the portal circulation, able to reach the liver and bind to the fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (FGFR4)/β-Klotho complex. This initiates a phosphorylation cascade in the c-jun N-terminal kinase-dependent pathway, ultimately inhibiting CYP7A1 expression hence BA synthesis2, a mechanism working in synergy with the hepatic FXR-SHP-dependent one3.

Altered BA signaling in the liver and intestine is associated with severe diseases including the development of cholestasis and HCC4–8. Hepatic diseases causing intrahepatic cholestasis, such as the progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 2 and 3 (PFIC2-3) caused by the multidrug resistance protein 3 (MDR3) deficiency, represent a specific risk of HCC development, especially in children9. ATP-binding cassette transporter (Abcb4)−/− and Fxr−/− mice are commonly used as elective models of HCC development8,10–15. Abcb4−/− mice lack the liver-specific permeability-glycoprotein responsible for phosphatidylcholine flippase on the outer leaflet of the hepatocyte canalicular membrane and therefore for secretion of phosphatidylcholine in bile. The absence of phospholipids from bile causes bile regurgitation into the portal tracts16, inducing accumulation of toxic BA levels, and consequent fibrosis that leads to hepatocyte dysplasia first and HCC at 12–15 months of age, mimicking human progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis17. Fxr−/− mice exhibit increased BA pool size and display cell hyperproliferation leading to the development of spontaneous HCC at 12 months of age18.

Strategies aimed at limiting BA overload are anticipated to provide hepatoprotection, as earlier reported in Fxr−/− mice treated with BA-sequestering agents8. We have recently shown that specific intestinal Fxr activation is sufficient to restore BA homeostasis in Fxr−/− mice, thus protecting them from age-related hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer18. Also, we have recently shown that long-term administration of a Fxr agonist enriched diet prevents spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis in Abcb4−/− mice via Fxr-Fgf15-dependent suppression of hepatic Cyp7a119.

The discovery of the role of FXR target gene, FGF15/19, in the feedback regulation of hepatic BA synthesis shed light on the physiological relevance of the crosstalk between the liver and intestine in the context of BA homeostasis2,20,21. FGF19 has also been implicated in HCC development. In fact, it is amplified in HCC and its expression is induced in liver of patients with extrahepatic cholestasis22–24. Interestingly, induction of Fgf15 expression in mice by intestinal Fxr overexpression protects against cholestasis and fibrosis, along with a reduction of the BA pool size25 suggesting that modulation of FGF19 levels could offer benefits in a plethora of BA-related metabolic disorders. However, despite its protective action, FGF19 has been shown to be protumorigenic and accelerate hepatic tumour formation in Abcb4−/− mice in an FGFR4-dependent fashion26,27 raising doubts on the safety of a chronic administration of this hormone28. Recently, the generation of a FGF19 variant (M70) that is equally effective as endogenous Fgf15/19 in terms of bile acid metabolic regulatory actions but does not show any pro-tumorigenic activity in 8 months old Abcb4−/− mice27 was described. Moreover, administration of FGF19-M70 in healthy human volunteers potently reduces BA synthesis29. This data provided us with the impetus to investigate the potential protective role of a novel non-tumorigenic FGF19 variant in spontaneous HCC development during BA dysregulation.

In the present work, we show for the first time that the non-tumorigenic variant of FGF19, namely FGF19-M52, retaining its intrinsic metabolic effects on Cyp7a1 repression and consequent reduction of hepatic BA synthesis, protects Abcb4−/− and Fxr−/− mice against spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis thus electing hepatic BA suppression as a metabolic strategy to prevent fibrosis and HCC in susceptible models.

Results

M52 is a non-tumorigenic variant of FGF19 that retains activity in regulating BA synthesis

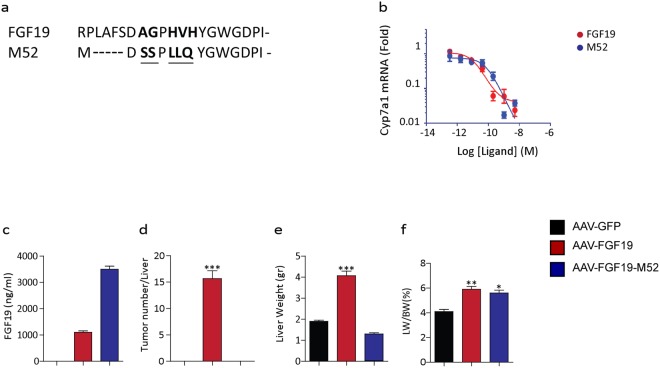

The novel engineered variant of the FGF19 protein M52 has been recently generated. M52 differs from wild-type FGF19 by five amino acid substitutions (A30S, G31S, H33L, V34L, H35Q) and five–amino acid deletion at the N terminus (Fig. 1a). In order to characterize the M52 variant and compare it to the full length FGF19, we tested CYP7A1 repression in primary human hepatocytes. qRT-PCR analysis shows that relative mRNA levels of CYP7A1 do not change in both FGF19 and M52 cell treatment, indicating that the M52 variant retains his biological activity of repression of de novo BA synthesis (Fig. 1b). Further in vivo analysis in db/db mice revealed that M52 is present in plasma as well as FGF19 (Fig. 1c). Moreover, while FGF19 administration causes an increased number of tumors per liver as well as a raised liver weight and liver/body weight ratio compared to controls, the M52 variant does not show any tumorigenic activity (Fig. 1d–f, respectively).

Figure 1.

M52 is a non-tumorigenic variant of FGF19 that retains activity in regulating BA synthesis. (a) Alignment of protein sequences of M52 and FGF19 in the N-terminal region. Mutations introduced into M52 are underlined. (b) Repression of CYP7A1 mRNA expression by AAV-M52 vs AAV-GFP in primary human hepatocytes. (c) Plasma levels of transgene expression, (d) number of tumors per liver, (e) liver weight and (f) percentage of liver weight over body weight ratio in db/db mice injected with AAV-GFP (black bar), AAV-FGF19 (red bar) or AAV-FGF19-M52 (blue bar). All values represent means ± SEM. Statistical significance comparing either FGF19 or M52 versus control (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test.

FGF19-M52 metabolically protects Abcb4−/− mice from age-related liver damage

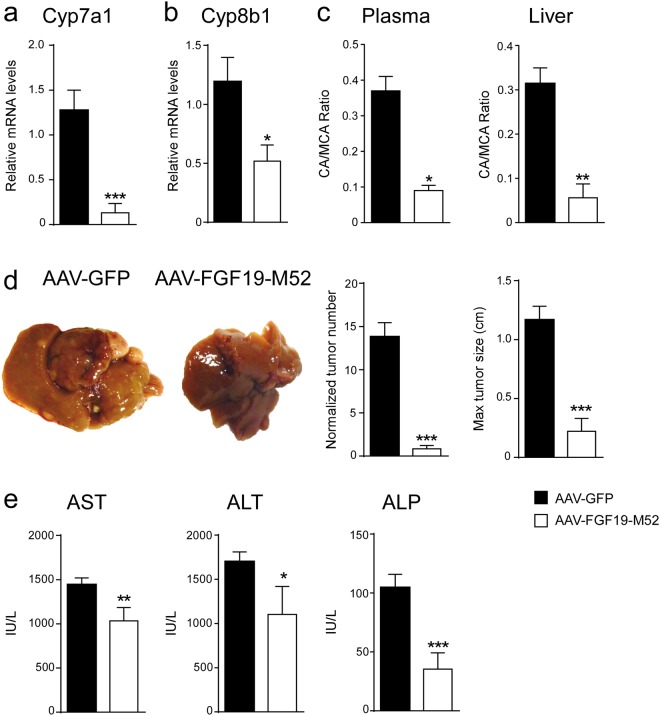

The non-tumorigenicity of the novel FGF19-M52 variant and its concomitant ability to maintain CYP7A1 repression, prompt us to explore its metabolic and antitumoral ability in aged Abcb4−/− mice, a murine model of impaired BA homeostasis-induced HCC. Aged Abcb4−/− mice have been elected as a unique animal model for studying HCC pathogenesis because they resemble many features of human HCC progression. 100% of aging Abcb4−/− mice display metabolic derangement due to liver inflammation and toxicity induced by a progressive increase and accumulation of BAs. ELISA measurement shows a strikingly higher amount of FGF19 in adenovirus (AAV)-FGF19-M52-treated mice compared to AAV-green fluorescent protein (GFP) controls (AAV-GFP 8.38 ± 6.28 vs AAV-FGF19-M52 434.5 ± 83.65 pg/ml). Compared to the control group, AAV-FGF19-M52-injected mice displayed a significant lower hepatic mRNA expression of the key limiting enzyme of BA synthesis Cyp7a1 (Fig. 2a). Also, the cytochrome P450 family 8 subfamily B member 1 (Cyp8b1) - another critical enzyme controlling the ration between Cholic Acid (CA) and Chenodeoxyxholic acid (CDCA) by regulating the synthesis of CA - results inhibited in AAV-FGF19-M52-treated mice compared to control (Fig. 2b). These changes were translated in an extremely powerful reduction of the plasmatic total BA pool size (AAV-GFP 74.65 ± 12.54 vs AAV-FGF19-M52 0.63 ± 0.11 μM) and a shift in both plasma and liver BA composition to a more hydrophilic BA pool profile due to the enrichment in muricholic acid (MCA) (Fig. 2c, Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 2.

FGF19-M52 analogue protects Abcb4−/− mice from age-related liver damage and HCC progression. qPCR of hepatic (a) Cyp7a1 (b) Cyp8b1. Expression was normalized to Cyclophillin. (c) BA composition (CA/MCA Ratio) in murine plasma and liver. (d) Macroscopic appearance of livers, normalized tumor number and maximum tumor size of 16-months-old Abcb4−/− mice (n = 14–24). (e) Biochemical parameters of liver damage in 16 months old Abcb4−/− mice. Statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) was assessed by Mann-Whitney’s U test.

Table 1.

Serum Bile Acid Composition.

| Genotype | CA% | UDCA% | CDCA% | DCA% | LCA% | MCA% | TCA% | TUDCA% | TCDCA% | TDCA% | TLCA% | TMCA% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abcb4−/−-GFP | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 5.42 ± 1.15 | 24.46 ± 1.58 | 2.08 ± 0.73 | 3.22 ± 0.13 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0 ± 0 | 63.69 ± 1.24 |

| Abcb4−/−-M52 | 4.98 ± 1.2 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 5.8 ± 1.65 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 18.32 ± 3.81 | 4.92 ± 3.32 | 0.12 ± 0.1 | 0.69 ± 0.61 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0 ± 0 | 62.63 ± 2.73 |

| Fxr−/−-GFP | 12.5 ± 3.17 | 0.83 ± 0.25 | 1.25 ± 0.38 | 8.2 ± 1.64 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | 8.1 ± 1.24 | 47.81 ± 3.69 | 0.68 ± 0.166 | 0.68 ± 0.166 | 3.78 ± 0.67 | 0 ± 0 | 15.93 ± 2.29 |

| Fxr−/−-M52 | 11.76 ± 3.03 | 1.22 ± 0.27 | 0.56 ± 0.14 | 3.22 ± 0.94 | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 28.88 ± 8.29 | 23.9 ± 6.86 | 0.53 ± 0.12 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.13 | 0 ± 0 | 29.37 ± 9.5 |

CA, cholic acid; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; CDCA, chenodeoxycholic acid; DCA, deoxycholic acid; LCA, lithocholic acid; MCA, muricholic acids; TCA, taurocholic acid; TUDCA, tauroursodeoxycholic acid; TCDCA, taurinechenodeoxycholic acid; TDCA, taurinedeoxycholic acid; TLCA, taurinelithocholic acid; TMCA, taurinemuricholic acids.

Table 2.

Liver Bile Acid Composition.

| Genotype | CA% | UDCA% | CDCA% | DCA% | LCA% | MCA% | TCA% | TUDCA% | TCDCA% | TDCA% | TLCA% | TMCA% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abcb4−/−-GFP | 1.23 ± 0.27 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.09 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0 | 34.73 ± 3.77 | 21.31 ± 1.69 | 0.88 ± 0.27 | 2.99 ± 0.25 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 37.74 ± 5.06 |

| Abcb4−/−-M52 | 0.7 ± 0.45 | 0.82 ± 0.15 | 0.96 ± 0.11 | 0 ± 0 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 70.04 ± 4.6 | 4.02 ± 1.86 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 2.15 ± 0.26 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0 ± 0 | 21.02 ± 3.82 |

| Fxr−/−-GFP | 5.31 ± 0.24 | 1.15 ± 0.25 | 0.78 ± 0.18 | 0.56 ± 0.12 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 25.98 ± 1.61 | 52.59 ± 2.88 | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 1.57 ± 0.34 | 8.62 ± 1.54 | 0.27 ± 0.09 | 2.83 ± 0.42 |

| Fxr−/−-M52 | 1.28 ± 0.24 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0 | 16.02 ± 3.9 | 24.96 ± 4.79 | 0.68 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.04 | 0.82 ± 0.22 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 55.5 ± 4.09 |

CA, cholic acid; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; CDCA, chenodeoxycholic acid; DCA, deoxycholic acid; LCA, lithocholic acid; MCA, muricholic acids; TCA, taurocholic acid; TUDCA, tauroursodeoxycholic acid; TCDCA, taurinechenodeoxycholic acid; TDCA, taurinedeoxycholic acid; TLCA, taurinelithocholic acid; TMCA, taurinemuricholic acids.

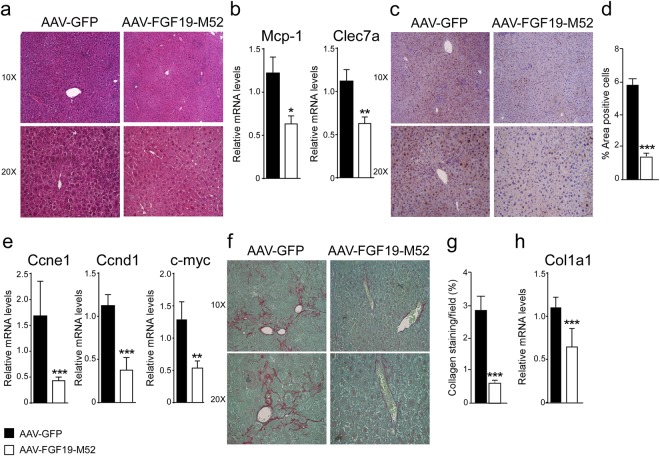

In order to investigate whether the metabolic changes induced by the FGF19-M52 analogue would translate in protection from HCC occurrence, macroscopic analysis of 16 months old Abcb4−/− mice liver was performed at the day of sacrifice. Earlier studies suggested that attenuation of systemic BA overload reduce number and size of liver tumors8,18. As expected, 100% of Abcb4−/− mice injected with the control adenovirus AAV-GFP showed macroscopically identifiable tumours. Remarkably, almost no tumors could be identified in Abcb4−/− mice injected with AAV-FGF19-M52 compared to controls (Fig. 2d), and when a tumor was borne in these mice it was significantly smaller compared to control mice. This protection was accompanied by a great reduction of plasma biochemical parameters of liver damage, as indicated by a decrease of the hepatic enzymes aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in FGF19-M52 mice compared to GFP-treated mice (Fig. 2e). We also analysed liver morphology and HE staining shows liver injury and disrupted hepatic parenchymal structure in GFP-injected Abcb4−/− mice, while FGF19-M52-injected mice display a more preserved hepatic parenchyma and less inflammatory infiltrates (Fig. 3a). This is accompanied by a reduction of the immune response regulators C-type lectin domain family 7 member A (Clec7a) and monocyte chemo-attractant protein 1 (MCP-1) (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

FGF19-M52 analogue protects Abcb4−/− mice from fibrosis and cellular proliferation. (a) Liver histology assessed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and observed by light microscopy (magnification, 10–20X). (b) Mcp-1 and Clec7a gene expression levels assessed by real time qPCR in tumor-free liver extracts. (c) Hepatic immunohistochemical staining of the oncogene Ccnd1. (d) Quantification of Ccnd1 staining assessed with ImageJ and expressed as % of the area occupied by positive cells. (e) CCnd1, Ccne1 and c-myc gene expression levels assessed by real time qPCR in tumor-free liver extracts. Expression was normalized to Cyclophillin. (f) Hepatic collagen deposition assessed by Sirius Red staining (magnification, 10–20X). (g) Quantification of collagen deposition assessed with ImageJ and expressed as % of collagen staining/field (h) Col1a1 gene expression levels assessed by real time qPCR in tumor-free liver extracts. Expression was normalized to Cyclophillin. All values represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) was assessed by Mann-Whitney’s U test.

FGF19-M52 protects Abcb4−/− mice from hepatic collagen deposition and fibrosis

Liver fibrosis results from chronic damage to the liver in conjunction with the accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, which is a characteristic of most types of chronic liver diseases30. Lack of the Abcb4 gene elicits a plethora of detrimental cell responses, including hepatic fibrosis, thus laying the foundation to hepatocarcinogenesis. In order to explore the effect of our FGF19 analogue on fibrogenesis we examine the extent of hepatic collagen deposition in liver isolated from aged Abcb4−/− mice injected with or without M52. Liver immunohistochemical analysis with Sirius Red staining and quantification of the signal revealed that livers from M52-treated Abcb4−/− mice were less fibrotic as compared to GFP mice (Fig. 3f,g). This finding was paralleled by mRNA inhibition of Collagen type 1 alpha 1 (Col1a1) in M52 Abcb4−/− mice compared to the control group (Fig. 3h).

FGF19-M52 protects Abcb4−/− mice from overexpression of HCC oncogenes

Alterations of cell-cycle-related genes have been documented in hepatocarcinogenesis31,32 as well as a compensatory proliferative response to BA-induced hepatocellular damage, thus providing evidence for a prognostic role of G1-S modulators in HCC. Abcb4−/− mice also present with cell hyperproliferation. CyclinD1 (Ccnd1) is a key regulator of cell cycle progression, and its overexpression has been reported to be sufficient to initiate hepatocellular carcinogenesis33. Accordingly, mouse models of disrupted BA homeostasis, such as Fxr−/− and Shp−/− mice, display enhanced Ccnd1 expression34,35. AAV-FGF19-M52 lowered Ccnd1 protein, as shown by immunohistochemical analysis, and transcript in aged Abcb4−/− mice (Fig. 3c,d). Furthermore, dysregulated cyclinE1 (Ccne1) expression, as well as c-myc gene, have been shown to act as potent oncogenes, and amplification of both genes promotes HCC formation36,37. mRNA analysis also revealed a marked inhibition of Ccne1 and c-myc expression in AAV-FGF19-M52-injected Abcb4−/− mice compared to controls (Fig. 3e).

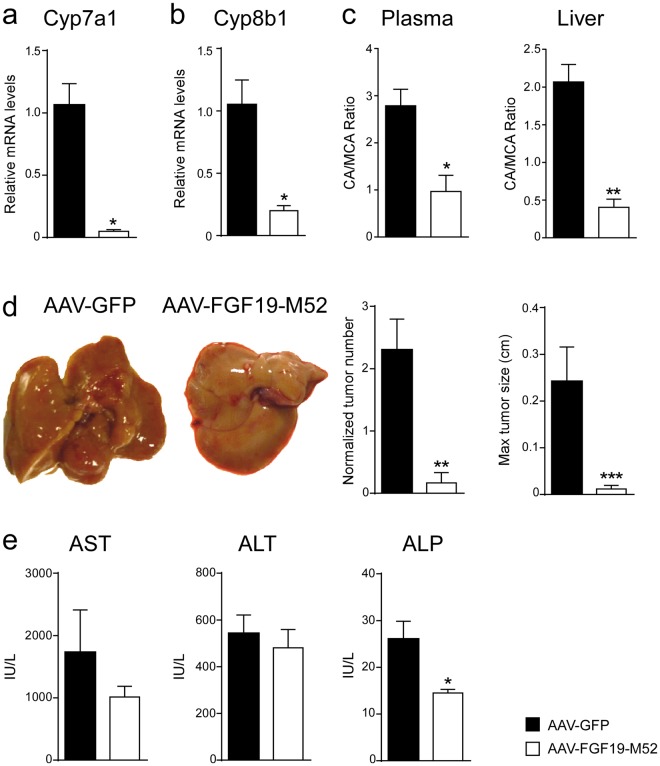

FGF19-M52 protects Fxr−/− mice from HCC

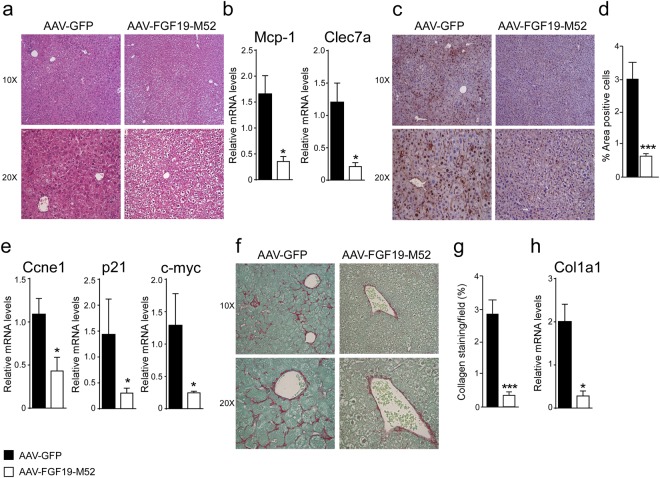

We have previously shown that intestinal-specific Fxr reactivation, and in particular the entero-hepatic Fxr-Fgf15 axis activation, is able to prevent liver damage and its spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis progression even in the absence of hepatic Fxr. In order to bypass the Fxr involvement and corroborate the importance of the intestinal hormone FGF19, we performed the same experiment and analysis conducted in Abcb4−/− mice in aged Fxr−/− mice. ELISA measurement shows a stricking amount of FGF19 in AAV-FGF19-M52-treated mice compared to AAV-GFP controls (AAV-GFP 0.33 ± 0.06 vs AAV-FGF19-M52 1021 ± 178.3 μM). AAV-FGF19-M52-injected mice displayed a significant lower hepatic mRNA expression of the key limiting enzymes of BA synthesis Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 compared to the control GFP-injected group (Fig. 4a,b). These changes were translated in a reduction of the plasmatic total BA pool size (AAV-GFP 11.48 ± 13.88 vs AAV-FGF19-M52 8.20 ± 3.59 μM) and a shift in both plasma and liver BA composition to a more hydrophilic BA pool profile due to the enrichment in MCA (Fig. 4c, Tables 1 and 2). 14 months old AAV-FGF19-M52 Fxr−/− mice presented with a striking lower number of macroscopically visible liver tumors and smaller in size compared to controls (Fig. 4d). This was accompanied by a significantly decreased level of plasma ALP level and a lowered trend of ALT and AST compared to control mice (Fig. 4e). Liver morphology and HE staining shows liver injury and disrupted hepatic parenchymal structure in GFP-injected Fxr−/− mice, in contrast with a more preserved hepatic parenchyma and less inflammatory infiltrates observed in FGF19-M52-treated mice (Fig. 5a). In parallel, a decrease in Clec7a and MCP-1 was observed in FGF19-M52-injected mice compared to the control group (Fig. 5b). Previous studies have shown that, during aging, Fxr−/− mice are characterized by enhanced fibrogenesis and cell proliferation8,11,38,39, therefore we performed Sirius Red and Ccnd1 stainings along with q-RTPCR analysis. M52-treatment revealed a protection in terms of fibrosis and collagen deposition at mRNA and protein level (Fig. 5f–h) as well as significantly lower hyperproliferative molecular status compared to GFP-treated controls as indicated by a decrease in protein and mRNA levels of Ccne1, p21 and c-myc (Fig. 5c–e).

Figure 4.

FGF19-M52 analogue protects Fxr−/− mice from age-related liver damage and HCC progression. qPCR of hepatic (a) Cyp7a1 (b) Cyp8b1. Expression was normalized to Cyclophillin. (c) BA composition (CA/MCA Ratio) in murine plasma and liver. (d) Macroscopic appearance of livers, normalized tumor number and maximum tumor size of 14-months-old Fxr−/− mice (n = 8–16). (e) Biochemical parameters of liver damage in 14 months old Fxr−/− mice. Statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) was assessed by Mann-Whitney’s U test.

Figure 5.

FGF19-M52 analogue protects Fxr−/− mice from fibrosis and cellular proliferation. (a) Liver histology assessed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and observed by light microscopy (magnification, 10–20X). (b) Mcp-1 and Clec7a gene expression levels assessed by real time qPCR in tumor-free liver extracts. (c) Hepatic immunohistochemical staining of the oncogene Ccnd1. (d) Quantification of Ccnd1 staining assessed with ImageJ and expressed as % of the area occupied by positive cells. (e) Ccne1, p21 and c-myc gene expression levels assessed by real time qPCR in tumor-free liver extracts. Expression was normalized to Cyclophillin. (f) Hepatic collagen deposition assessed by Sirius Red staining (magnification, 10–20X). (g) Quantification of collagen deposition assessed with ImageJ and expressed as % of collagen staining/field (h) Col1a1 gene expression levels assessed by real time qPCR in tumor-free liver extracts. Expression was normalized to Cyclophillin. All values represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) was assessed by Mann-Whitney’s U test.

Discussion

FGF19 is a post-prandial enterokine and a cornerstone of BA synthesis control, also regulating carbohydrate, lipid and energy homeostasis40,41. The landmark discovery of the FXR-FGF19 axis in the regulation of the BA homeostasis core2,20,21,42 opened new avenues for intestinal-specific therapeutic management of chronic diseases of the gut-liver axis. The therapeutic exploitation of the intestinal FXR/FGF19 axis activation in cholestasis25 and its translation into protection from HCC development in Abcb4−/− mice19 prompt us to further examine the feasibility of a FGF19-based therapy in chronic liver and intestinal disease. However, literature data are debatable whether the enterokine FGF19 is per se implicated22–24,26,28 or not43,44 in HCC development. The in-depth characterization of FGF19 molecular structure and function allowed us to design a novel FGF19-based pre-clinical therapeutic agent uncoupling its metabolic activities from the proliferative ones. In fact, another novel engineered variant of FGF19 protein (M70) which fully retains BA regulatory activity but is devoid of murine pro-tumoral activity has been recently identified45. M70 differs from wild-type FGF19 by three amino acid substitutions (A30S, G31S, H33L) and a five amino acid deletion at the N terminus (P24-S28). Zouh et al. demonstrated that M70 interacts with the FGFR4 receptor and exhibits the pharmacologic characteristics of a biased ligand that selectively activates certain signalling pathways (e.g., cytochrome P450 7A1, phosphorylated extracellular signal–regulated kinase) and exclusion of others (e.g., tumorigenesis, phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3)45. The identification of these types of FGF19 variants, including our M52, has greatly helped in overcoming the severe side effect of therapies targeting FGF1946,47, due to derangement in the gut-liver axis regulation of BA homeostasis and consequent development of liver toxicity and diarrhoea. The therapeutic potential of FGF19-M70 analogue has been well characterized and, unlike the natural form of FGF19, it does not show any pro-tumorigenic activity in 8 months old Abcb4−/− mice, age at which these mice have not developed hepatic tumours yet27.

Here, we study the novel non-tumorigenic analogue FGF19-M52 as putative drug to inhibit Cyp7a1, reduce BA synthesis and eventually protect against BA-induced cancer in the liver. To this end, we show for the first time that the FGF19-M52 analogue protects against spontaneous hepatic tumorigenesis in 16 months old mice Abcb4−/−, through the reduction of BA concentrations and modification of the BA pool. Moreover, our results demonstrate that M52 retains control of BA negative feedback of the gut-liver loop and prevents BA-induced spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis in 14 months old Fxr−/− mice. Moreover, FGF19-M52 is also able to reduce Cyp8b1 expression, while no changes in the expression of BA transporters (Bsep, Ntcp, Oatp1 and Oatp2) and FGF19 receptors (Fgfr4 and β-klotho) were found (data not shown), indicating that FGF19-M52 globally reduces BA levels without a direct transcriptional impact on their secretory or transport genes.

It is well known that both Fxr and Abcb4 genes ablation in mice leads to liver damage, fibrosis, cholestasis and spontaneous HCC induced by high level of hydrophobic cytotoxic BAs. Indeed, the absence of Abcb4 leads to accumulation of intraductal and biliary BAs that in absence of phosphatidylcholine are cytotoxic and exert their detergent activity that represent the primum movens for the sequaela of events that lead to HCC. On a different angle, the absence of Fxr leads to de-repression of hepatic Cyp7a1 with consequent potent increased BA synthesis and concentration systemically and within the liver. These events represent the leading step for liver damage, inflammation and fibrosis that bring Fxr−/− mice to spontaneous HCC formation.

FGF19-M52-dependent inhibition of Cyp7a1 and the consequent decrease of intrinsically harmful BA pool size and composition protect from hepatic tumour formation, even in the absence of Fxr. Mechanistically, the decrease of BA chronically high level and the shift of their composition into a more favourable hydrophilic one result in an outstanding inhibition of hepatic fibrosis that promptly translates into a blockage of overexpression of the typical HCC oncogenes Ccnd1, c-myc and others. Thus, in both models, FGF19-M52-dependent modulation of BA concentration with reduction of their levels and toxicity protect from liver damage and HCC.

Our findings support the concept that the control of BAs synthesis is definitely of great importance and could effectively reverse Abcb4- and Fxr-deficiency-associated hepatocarcinogenesis, suggesting that multiple metabolic players are involved in the hepatocarcinogenesis-preventing scenario. Our finding leverages the fine effort of testing novel FGF19 engineered variants that could display anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects but also antitumoral actions, thus opening bona fide a novel pharmacological strategy for example in PFIC patients who are susceptible to HCC formation even in young age.

Methods

AAV Production

AAV293 cells (Agilent Technologies) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1x antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Mediatech). Cells were transfected with three different plasmids (20 µg/plate, each) including AAV transgene plasmids, pHelper plasmid (Agilent Technologies) and AAV2/9 plasmid. Cells were harvested forty-eight hours after transfection. Viral particles in cell lysates were purified using a discontinued iodixanal gradient (Sigma-Aldrich). To determine the viral titer or genome copy number, viral stock was incubated in a solution containing 50 units/mL Benzonase, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM CaCl2 at 37 °C for 30 minutes. Viral DNA was cleaned with mini DNeasy Kit (Qiagen) and eluted with 40 µL of water. Viral genome copy was determined by quantitative PCR.

Animal studies

For the characterization of the FGF19 analogue M52 obtained from NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Inc (se WO 2013/006486), 10–12 week old male db/db mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory, and housed in a pathogen-free animal facility at 22ºC under controlled 12 hour light/12 hour dark cycle. All mice were kept on standard chow diet (Harlan Laboratories, Teklad 2918) and autoclaved water ad libitum. For in vivo tumorigenicity studies, cohorts db/db mice (n = 5) were randomized into treatment groups based on body weight. All animals received a single 200 μl intravenous injection of 3 × 1011 genome copies of either AAV-FGF19, AAV-M52, or a control virus encoding green fluorescent protein via tail vein. Animals were euthanized and livers were collected 24 weeks after injection of the AAV vectors for histology and gene expression analysis. These animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at NGM. For the HCC murine models, Abcb4−/− mice on an FVB/N background were obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Charles River, Lecco, Italy) and whole-body Fxr−/− mice were originally obtained from Dr. Frank J. Gonzalez (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Male 8-weeks-old Abcb4−/− and Fxr−/− mice (n = 14–24 and n = 8–16, respectively) received a single intravenous dose of 1 × 1011 vector genome of AAV containing genes encoding either the FGF19-M52 form or control GFP. All mice were housed under a standard 12-hour light/dark cycle and fed standard rodent chow diet and autoclaved tap water ad libitum. Mice were aged until 14 and 16-months-old (Fxr−/− and Abcb4−/−, respectively), sacrificed and analyzed for tumor development. All experiments were approved by the Italian Ministry of Health in accord with internationally accepted guidelines for animal care.

Primary human hepatocytes

Primary hepatocytes from human livers (Life Technologies) were plated on collagen I-coated 96-well plates (Becton Dickinson) and incubated overnight in Williams’ E media supplemented with 100 nM dexamethasone and 0.25 mg/mL matrigel. Cells were treated with recombinant M52 or FGF19 proteins for six hours before lysis. Cells were treated with recombinant M52 or FGF19 proteins for six hours before lysis.

Measurement of Plasma M52 and FGF19 Protein

Levels of human FGF19 and variants were measured in plasma using an ELISA assay (Biovendor). The assay recognizes both FGF19 and M52 in an indistinguishable manner.

Blood Parameters

Levels of ALT, AST and ALP were measured with a colorimetric kit (BioQuant Heidelberg, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Chemicals

CA and other endogenous BAs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All solvents were of high purity and used without further purification. Acetonitrile for HPLC was from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany); methyl alcohol RPE, ammonia solution 30% RPE, glacial acetic acid RPE were from Carlo Erba Reagent (Milan, Italy); activated charcoal was from Sigma-Aldrich; and ISOLUTE C18 cartridges (500 mg, 6 ml) for the plasma sample pretreatment were purchased from StepBio (Bologna, Italy). Plasma BA free rat plasma was treated with activated 50 mg/ml charcoal and stirred at 4°C overnight. After centrifugation at 3000 g for 5 minutes the plasma was filtered through Millipore A10 Milli-Q Synthesis (0.45 µm) and stored at −20° C.

Bile Acid Measurements

Plasma and hepatic BAs were identified and quantified by high-pressure liquid chromatography-electrospray-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (HPLC-ES-MS/MS) by optimized methods48 suitable for use in pure standard solution, plasma and liver samples after appropriate clean-up preanalytical procedures. Liquid chromatography analysis was performed using an Alliance HPLC system model 2695 from Waters combined with a triple quadruple mass spectrometer QUATTRO-LC (Micromass; Waters) using an electrospray interface. The analytical column was a Waters XSelect CSH Phenyl-hexyl column, 5 µm, 150 × 2.1 mm, protected by a self-guard column Waters XSelect CSH Phenyl- hexyl 5 µm, 10 × 2.1 mm. BAs were separated by elution gradient mode with a mobile phase composed of a mixture ammonium acetate buffer 15 mM, pH 8.0 (Solvent A) and acetonitrile:methanol = 75:25 v/v (Solvent B). Chromatograms were acquired using the mass spectrometer in multiple reaction monitoring mode. Plasma and hepatic bile acids were extracted using a standard, previously validated protocol19.

mRNA extraction and quantitative real time qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from tumor-free livers using RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Milano, Italy). cDNA was generated from 4 µg total RNA using High Capacity DNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA expression levels were quantified by qRTPCR using Power Syber Green chemistry and normalized to cyclophillin mRNA levels. Relative quantification was performed using the ΔΔCT method. Validated primers for real time PCR are available upon request.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Macroscopically tumor-free liver samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer- thick sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) following standard protocols. Liver fibrosis was analyzed with Sirius Red by using Direct Red 80 and Fast Green FCF (Sigma Aldrich, Milan, Italy). Hepatocyte proliferation was assessed by immuno-histochemical detection of cyclin D1 (CCND1). All stained sections were analyzed through a light microscope. Histological features of hepatic disease have been assessed according to Histological Scoring System by Kleiner DE et al.49 and Brunt EM et al.50.

Statistical Analysis

All measurements were performed in technical triplicates. All results are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Significant differences between three groups were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test, while between two groups were determined by Mann-Whitney’s U test. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software (v5.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) and conducted as a two-sided alpha level of 0.05.

Ethics Statement

The Ethical Committee of the University of Bari approved this experimental set-up, which also was certified by the Italian Ministry of Health in accordance with internationally accepted guidelines for animal care.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. A.K. Groen for providing the Abcb4−/− mice. A. Moschetta is funded by Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC, IG 18987), NR-NET FP7 Marie Curie ITN and JPI Fatmal.

Author Contributions

R.G. contributed to study design, performed experiments and contributed to paper writing; N.S. performed animal studies; C.P. performed histology; M.C. performed gene expression analysis; B.K. and J.L. generated AAVFGF19M52 and performed experiments in db/db mice; E.P. performed BA measurements; A.R. supervised the BA profiling; C.S. provided expertise in hepatic physiology and contributed to the translational relevance of the data analysis; A.M. designed the study, supervised the project and wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

Brian Ko and Jian Luo are employers of NGM Biopharmaceuticals, San Francisco CA and provided the AAV with FGF19-M52 analogue and GFP controls. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur. J. Cancer. 2010;46:765–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inagaki T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005;2:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim I, et al. Differential regulation of bile acid homeostasis by the farnesoid X receptor in liver and intestine. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:2664–2672. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700330-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron R, Imaida K, Ito N. Promotive effects of deoxycholic acid on hepatocarcinogenesis initiated by diethylnitrosamine in male rats. Gan. 1981;72:635–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen T, et al. Serum and urine metabolite profiling reveals potential biomarkers of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.004945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knisely AS, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in ten children under five years of age with bile salt export pump deficiency. Hepatology. 2006;44:478–486. doi: 10.1002/hep.21287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, et al. Bile Acid Receptors and Liver Cancer. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2013;1:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s40139-012-0003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang F, et al. Spontaneous development of liver tumors in the absence of the bile acid receptor farnesoid X receptor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:863–867. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zen Y, Vara R, Portmann B, Hadzic N. Childhood hepatocellular carcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 12 cases with special reference to EpCAM. Histopathology. 2014;64:671–682. doi: 10.1111/his.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauad TH, et al. Mice with homozygous disruption of the mdr2 P-glycoprotein gene. A novel animal model for studies of nonsuppurative inflammatory cholangitis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 1994;145:1237–1245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim I, et al. Spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis in farnesoid X receptor-null mice. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:940–946. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kok T, et al. Enterohepatic circulation of bile salts in farnesoid X receptor-deficient mice: efficient intestinal bile salt absorption in the absence of ileal bile acid-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:41930–41937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makishima M, et al. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science. 1999;284:1362–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parks DJ, et al. Bile acids: natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science. 1999;284:1365–1368. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinal CJ, et al. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell. 2000;102:731–744. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fickert P, et al. Regurgitation of bile acids from leaky bile ducts causes sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:261–274. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vree JM, et al. Correction of liver disease by hepatocyte transplantation in a mouse model of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1720–1730. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degirolamo C, et al. Prevention of spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis in farnesoid X receptor-null mice by intestinal-specific farnesoid X receptor reactivation. Hepatology. 2015;61:161–170. doi: 10.1002/hep.27274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cariello M, et al. Long-term Administration of Nuclear Bile Acid Receptor FXR Agonist Prevents Spontaneous Hepatocarcinogenesis in Abcb4(−/−) Mice. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11203. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11549-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt JA, et al. Definition of a novel growth factor-dependent signal cascade for the suppression of bile acid biosynthesis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1581–1591. doi: 10.1101/gad.1083503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung D, et al. FXR agonists and FGF15 reduce fecal bile acid excretion in a mouse model of bile acid malabsorption. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:2693–2700. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700351-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latasa MU, et al. Regulation of amphiregulin gene expression by beta-catenin signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells: a novel crosstalk between FGF19 and the EGFR system. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e52711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawey ET, et al. Identification of a therapeutic strategy targeting amplified FGF19 in liver cancer by Oncogenomic screening. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaap FG, van der Gaag NA, Gouma DJ, Jansen PL. High expression of the bile salt-homeostatic hormone fibroblast growth factor 19 in the liver of patients with extrahepatic cholestasis. Hepatology. 2009;49:1228–1235. doi: 10.1002/hep.22771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Modica S, et al. Selective activation of nuclear bile acid receptor FXR in the intestine protects mice against cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:355–365. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.French DM, et al. Targeting FGFR4 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma in preclinical mouse models. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e36713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou M, et al. Engineered fibroblast growth factor 19 reduces liver injury and resolves sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2016;63:914–929. doi: 10.1002/hep.28257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholes K, et al. A mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma: ectopic expression of fibroblast growth factor 19 in skeletal muscle of transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;160:2295–2307. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61177-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo J, et al. A nontumorigenic variant of FGF19 treats cholestatic liver diseases. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:247ra100. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis — from bench to bedside. J. Hepatol. 2003;38(Suppl 1):S38–S53. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishida N, et al. Amplification and overexpression of the cyclin D1 gene in aggressive human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3107–3110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishida N, Fukuda Y, Ishizaki K, Nakao K. Alteration of cell cycle-related genes in hepatocarcinogenesis. Histol. Histopathol. 1997;12:1019–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deane NG, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma results from chronic cyclin D1 overexpression in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5389–5395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li G, et al. Small heterodimer partner overexpression partially protects against liver tumor development in farnesoid X receptor knockout mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013;272:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, et al. Orphan receptor small heterodimer partner suppresses tumorigenesis by modulating cyclin D1 expression and cellular proliferation. Hepatology. 2008;48:289–298. doi: 10.1002/hep.22342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaposi-Novak P, et al. Central role of c-Myc during malignant conversion in human hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2775–2782. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohashi R, et al. Enhanced expression of cyclin E and cyclin A in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:657–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kong B, et al. Mechanism of tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor in suppressing the expression of genes in bile-acid synthesis in mice. Hepatology. 2012;56:1034–1043. doi: 10.1002/hep.25740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu N, et al. Hepatocarcinogenesis in FXR−/− mice mimics human HCC progression that operates through HNF1alpha regulation of FXR expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012;26:775–785. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kir S, et al. FGF19 as a postprandial, insulin-independent activator of hepatic protein and glycogen synthesis. Science. 2011;331:1621–1624. doi: 10.1126/science.1198363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin BC, Desnoyers LR. FGF19 and cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012;728:183–194. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0887-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song KH, Li T, Owsley E, Strom S, Chiang JY. Bile acids activate fibroblast growth factor 19 signaling in human hepatocytes to inhibit cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene expression. Hepatology. 2009;49:297–305. doi: 10.1002/hep.22627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Avila MA, Moschetta A. The FXR-FGF19 Gut-Liver Axis as a Novel “Hepatostat”. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:537–540. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naugler WE, et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor Signaling Controls Liver Size in Mice With Humanized Livers. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:728–740. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou M, et al. Separating Tumorigenicity from Bile Acid Regulatory Activity for Endocrine Hormone FGF19. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3306–3316. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desnoyers LR, et al. Targeting FGF19 inhibits tumor growth in colon cancer xenograft and FGF19 transgenic hepatocellular carcinoma models. Oncogene. 2008;27:85–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pai R, et al. Antibody-mediated inhibition of fibroblast growth factor 19 results in increased bile acids synthesis and ileal malabsorption of bile acids in cynomolgus monkeys. Toxicol. Sci. 2012;126:446–456. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roda A, Gioacchini AM, Cerre C, Baraldini M. High-performance liquid chromatographic-electrospray mass spectrometric analysis of bile acids in biological fluids. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 1995;665:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00544-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kleiner DE, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brunt EM. Grading and staging the histopathological lesions of chronic hepatitis: the Knodell histology activity index and beyond. Hepatology. 2000;31:241–246. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]