Transcription factors play key roles in regulating virulence of the human fungal pathogen C. albicans. In addition to regulating the expression of virulence factors, they also control the ability of C. albicans to switch to filamentous hyphal growth, which facilitates biofilm formation on medical devices and invasion into tissues. We therefore used new CRISPR/Cas9 methods to examine the effects of deleting three C. albicans genes (NDT80, REP1, and RON1) that encode transcription factors with similar DNA binding domains. Interestingly, double and triple mutant strains mostly showed the combined properties of the single mutants; there was only very limited evidence of synergistic interactions in regulating morphogenesis, stress resistance, and ability to metabolize different sugars. These results demonstrate that NDT80, REP1, and RON1 have distinct functions in regulating C. albicans virulence functions.

KEYWORDS: Candida albicans, NDT80, REP1, RON1, hyphae, morphogenesis

ABSTRACT

Ndt80 family transcription factors are highly conserved in fungi, where they regulate diverse processes. The human fungal pathogen Candida albicans contains three genes (NDT80, REP1, and RON1) that encode proteins with similarity to Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ndt80, although the homology is restricted to the DNA binding domain. To better understand their role in virulence functions, we used clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat/CRISPR-associated gene 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) to delete the three NDT80-family genes. An ndt80Δ mutant showed strong defects in forming hyphae in response to serum or N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), which was linked to the ability of Ndt80 to regulate the expression of RAS1, an upstream regulator of hyphal signaling. Conversely, the ndt80Δ mutant formed hyphal cells on glycerol medium, indicating that Ndt80 is not required for hyphal growth under all conditions. In contrast to our previously published data, a ron1Δ single mutant could grow and form hyphae in response to GlcNAc. However, deleting RON1 partially restored the ability of an ndt80Δ mutant to form hyphae in response to GlcNAc, indicating a link to GlcNAc signaling. REP1 was required for growth on GlcNAc, as expected, but not for GlcNAc or serum to induce hyphae. The ndt80Δ mutant was defective in growing under stressful conditions, such as elevated temperature, but not the ron1Δ mutant or rep1Δ mutant. Quantitative assays did not reveal any significant differences in the fluconazole susceptibility of the NDT80-family mutants. Interestingly, double and triple mutant analysis did not identify significant genetic interactions for these NDT80 family genes, indicating that they mainly function independently, in spite of their conserved DNA binding domain.

IMPORTANCE Transcription factors play key roles in regulating virulence of the human fungal pathogen C. albicans. In addition to regulating the expression of virulence factors, they also control the ability of C. albicans to switch to filamentous hyphal growth, which facilitates biofilm formation on medical devices and invasion into tissues. We therefore used new CRISPR/Cas9 methods to examine the effects of deleting three C. albicans genes (NDT80, REP1, and RON1) that encode transcription factors with similar DNA binding domains. Interestingly, double and triple mutant strains mostly showed the combined properties of the single mutants; there was only very limited evidence of synergistic interactions in regulating morphogenesis, stress resistance, and ability to metabolize different sugars. These results demonstrate that NDT80, REP1, and RON1 have distinct functions in regulating C. albicans virulence functions.

INTRODUCTION

The human fungal pathogen Candida albicans commonly lives as a commensal on mucosal surfaces of most healthy humans, but it can initiate life-threatening systemic infections in those who are immunocompromised. Thus, C. albicans infections are the fourth most common type of nosocomial bloodstream infection (1). The attributable mortality rate is about 40% in spite of recent advances in antifungal therapy (2, 3), and the emergence of strains that are resistant to antifungal drugs is a further challenge to delivering effective therapy (4). Therefore, it is important to define the mechanisms of C. albicans pathogenesis in order to develop new therapies. One major factor that promotes C. albicans infections is its ability to grow in different morphologies ranging from budding cells to long chains of hyphal or pseudohyphal cells (5). The ability of C. albicans to grow as long filamentous hyphae is significant for its pathogenic potential as it promotes invasive growth into host tissues and biofilm formation (5, 6). Hyphal growth can be induced in vitro by a variety of environmental stimuli, including serum, alkaline pH, CO2, and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) (5, 7–9). Mutational analysis has identified a network of transcription factors (TFs) that are important for inducing the hyphal morphology. These TFs are also needed to induce a special set of genes during hyphal growth that encode factors needed for virulence, such as adhesin proteins and superoxide dismutase (5, 10–12).

One TF needed for hyphal growth in C. albicans is Ndt80 (10). The Ndt80 family is significant because it is highly conserved across a large group of fungal species (Fig. 1A). The number of Ndt80-like genes varies in different fungi, ranging from zero (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) and one (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) to six (Fusarium oxysporum strain HDV247) (13). They regulate diverse processes, including sexual development, filamentation, drug resistance, virulence, and the response to nutrient stress (13–16). One well-studied paralog is S. cerevisiae Ndt80, which is a key regulator of meiosis and sporulation (17, 18). In species that encode multiple Ndt80 homologs, genetic analyses indicate they can carry out distinct functions (13). In A. nidulans, one Ndt80-like protein (XprG) is a positive regulator that controls expression of an extracellular protease, mycotoxin production, and programmed cell death induced by carbon starvation (15), similarly to N. crassa VIB-1, which is required for expression of genes involved in heterokaryon incompatibility programmed cell death and, like XprG, is a positive regulator of extracellular protease production (14, 19). A. nidulans NdtA and N. crassa FSD-1, representing another type of Ndt80-related factor, have greater sequence similarity to S. cerevisiae Ndt80 and are required for sexual reproduction. Deletion of a third Ndt80-like gene in N. crassa (N. crassa U04729 [NCU04729]) had no effect on sexual reproduction or on any other phenotypes tested (14). Recently, functional analysis in Trichoderma reesei showed that one of Ndt80 homologs is a key activator of the GlcNAc gene cluster that is essential for GlcNAc catabolism (20).

FIG 1.

Strategy for multiple deletion of NDT80-family genes using transient CRISPR/Cas9 and the SAT1-FLP system. (A) In Candida albicans (Ca), there are three genes that encode proteins with similarity to S. cerevisiae (Sc) Ndt80. The amino acid sequence similarity is restricted to the DNA binding domain. The phylogenetic analysis of putative Ndt80 family proteins in Ascomycota indicates that Ndt80-like proteins can be assigned to two groups. One superbranch contains direct orthologs of S. cerevisiae Ndt80, such as Ca Ndt80 and Ca Ron1. Ca Rep1 clusters in the other superbranch, which features orthologs from Pezizomycotina. Colored stars indicate S. cerevisiae Ndt80 and C. albicans Ndt80 family proteins as follows. Color code: Candida CTG clade, blue; Saccharomycetaceae, green; Pezizomycotina, red. (B) The CAS9 gene and the sgRNA were expressed transiently after transformation and were not integrated into the genome. The sgRNA targets Cas9 protein to produce a double-strand break (DSB) at a defined target sequence. The double-strand breaks can be repaired by homology-directed recombination with the SAT1-FLP cassette DNA fragment, which has homology on the ends to the target gene, to create a homozygous deletion of the gene of interest (GOI). The SAT1-FLP cassette confers nourseothricin (NAT) selection and marker recycling. Marker excision of the SAT1 gene is mediated by the maltose-inducible FLP recombinase, leaving a single FLP recombinase target (FRT) site in place of the each GOI.

There are three NDT80 paralogs in C. albicans (NDT80, RON1, and REP1). NDT80 has been shown to promote resistance to various stress conditions and to have a role in hyphal growth (21–23). We previously reported that a mutant lacking RON1 displayed defects in growing on GlcNAc media and in inducing hyphae in response to GlcNAc (24), but we showed here that it is not required by the use of a new clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat/CRISPR-associated gene 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) method for making gene deletions. The third paralog, REP1, was identified as a negative regulator of the expression of the drug efflux pump MDR1 (25). REP1 was also shown to be needed for growth on some sugars, such as GlcNAc and galactose (26), and is thought to act in part by recruiting Ngs1 to specific promoters to regulate histone acetylation (26). To compare the mutant phenotypes in the same strain background, and to determine whether the Ndt80-like TFs have overlapping functions, we constructed single, double, and triple mutant combinations. To circumvent the difficulties of creating homozygous mutations in the diploid C. albicans, we took advantage of recent developments in the application of CRISPR-Cas9 (27–31), including transient CRISPR-Cas9 and SAT1-Flipper (27, 32). The use of the SAT1-Flipper drug resistance marker enabled us to analyze mutant phenotypes in fully prototrophic strains such that their phenotypes were not affected by auxotrophies. Interestingly, the results showed that the functions of Ndt80-like TFs are largely independent despite the presence of the conserved DNA binding domain (DBD) in C. albicans.

RESULTS

Creation of gene deletion strains using transient CRISPR-Cas9 and SAT1-FLP systems.

To investigate the genetic interactions within the NDT80 TF family, we constructed a set of mutants that contained homozygous deletion mutations for each TF, the three possible double mutants, and a triple mutant. The mutations were constructed using transient CRISPR-Cas9 and SAT1-FLP systems (Fig. 1B). In construction of single mutants, wild-type strain S. cerevisiae 5314 (SC5314) was transformed with Cas9 DNA, which is transiently expressed (27); a gene encoding a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to guide the CRISPR-Cas9 to a specific site in the target gene; and a repair template consisting of the recyclable SAT1-FLP cassette providing resistance to nourseothricin (NATr) (32) flanked by regions of homology to the sequences surrounding the targeted open reading frame. We then created the double deletion mutants in the NATs versions of the single deletion mutants in which the NATr gene was excised. A triple deletion mutant of the NDT80 TF family was generated in the ron1Δ rep1Δ NATs double mutant (Table 1). The frequency of creation of homozygous deletion mutants was similar to previous results for each round of gene deletions in the construction of the triple mutant (27).

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains used in this study

| Strain | Short genotype | Parent | Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC5314 | Wild-type strain | ||

| KH1493 | ndt80Δ | SC5314 | ndt80Δ::SAT1-FLIP/ndt80Δ::SAT1-FLIP |

| KH1494 | rep1Δ | SC5314 | rep1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/rep1Δ::SAT1-FLIP |

| KH1495 | ron1Δ | SC5314 | ron1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/ron1Δ::SAT1-FLIP |

| KH1496 | rep1Δ ndt80Δ | rep1Δ Nats | rep1Δ::FRT/rep1Δ::FRT ndt80Δ::SAT1-FLIP/ndt80Δ::SAT1-FLIP |

| KH1497 | ron1Δ ndt80Δ | ron1Δ Nats | ron1Δ::FRT/ron1Δ::FRT ndt80Δ::SAT1-FLIP/ndt80Δ::SAT1-FLIP |

| KH1498 | ron1Δ rep1Δ | ron1Δ Nats | ron1Δ::FRT/ron1Δ::FRT rep1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/rep1Δ::SAT1-FLIP |

| KH1499 | ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ | ron1 rep1Δ Nats | ron1Δ::FRT/ron1Δ::FRT rep1Δ::FRT/rep1Δ::FRT ndt80Δ::SAT1-FLIP/ndt80Δ::SAT1-FLIP |

| KH1500 | ndt80Δ + NDT80 | ndt80Δ Nats | ndt80Δ::FRT/ndt80Δ::FRT rps1::NDT80-CIp10-SAT1/RPS1 |

| KH1501 | rep1Δ + REP1 | rep1Δ Nats | rep1Δ::FRT/rep1Δ::FRT rps1::REP1-CIp10-SAT1/RPS1 |

| KH1502 | ron1Δ + RON1 | ron1Δ Nats | ron1Δ::FRT/ron1Δ::FRT rps1::RON1-CIp10-SAT1/RPS1 |

| KH1503 | ndt80Δ Nats | ndt80Δ | ndt80Δ::FRT/ndt80Δ::FRT |

| KH1504 | rep1Δ Nats | rep1Δ | rep1Δ::FRT/rep1Δ::FRT |

| KH1505 | ron1Δ Nats | ron1Δ | ron1Δ::FRT/ron1Δ::FRT |

| KH1506 | ron1Δ rep1Δ Nats | ron1Δ rep1Δ | ron1Δ::FRT/ron1Δ::FRT rep1Δ::FRT/rep1Δ::FRT |

Growth on different carbon sources.

Cells lacking NDT80 (C2_00140W) grew well on various carbon sources (Fig. 2A and B), similarly to the previous results (24). In fact, we found that the ndt80Δ mutant displayed slightly better growth on nonfermentable carbon sources (glycerol, lactate, and acetate) than the wild-type control. Interestingly, the ndt80Δ mutant showed filamentous hyphal cells emanating from colonies grown on the synthetic glycerol plates whereas other strains, including the wild-type SC5313 strain, formed smooth-edged colonies (Fig. 2C). This phenotype was surprising since Ndt80 has been reported to be required for hyphal growth in C. albicans (10, 12, 33, 34). These results indicate that Ndt80 can also act as a repressor of filamentous growth under some conditions. Cells lacking REP1 (CR_04250W) showed a strong defect with respect to growth on the amino sugars GlcNAc and glucosamine. Rep1 was reported to regulate GlcNAc catabolic genes by recruiting Ngs1 to the promoters of the genes (26). However, the rep1Δ mutant was also unable to grow on galactose, indicating that it has broader roles in regulating metabolism (Fig. 2A). The deletion mutant lacking RON1 (CR_04250W) did not exhibit a significant defect in growth on the different carbon sources. This contrasts with our previously published data (24) suggesting that mutant ron1Δ was defective in growth on GlcNAc and glucosamine. The reasons for these differences are unclear. However, we note that one difference is that the previous ron1Δ mutant was constructed in a different manner, including the use of auxotrophic markers for selection.

FIG 2.

The REP1 gene is needed for growth on galactose, GlcNAc, and glucosamine. Dilutions of cells were spotted onto minimal medium plates containing the indicated sugar. The genotype of the strain in each row is indicated on the left. The sugars were present at 50 mM, except for the plates containing glycerol, which was present at a higher concentration (300 mM) to promote better growth of the strains. The plates were incubated at 30°C for (A) 2 days or (B) 6 days and then photographed. The deletion mutants of REP1 (strains rep1Δ, rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ rep1Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) were specifically defective in growth on galactose, GlcNAc, and glucosamine. Note that the deletion mutants of NDT80 (strains ndt80Δ, rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ ndt80Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) grew slightly better on nonfermentative carbon sources (glycerol, lactate, and acetate). (C) The ndt80Δ cells grown on glycerol medium were distinct in that there were filamentous outgrowths of cells from the edges of the colonies. Scale bars indicate 1 mm. The strains used are listed in Table 1.

We next examined the set of double and triple homozygous mutants to determine if combining different mutations led to synergistic or compensatory growth phenotypes. However, none were detected (Fig. 2). All double and triple mutants lacking REP1 (mutants rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ rep1Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) did not grow well on galactose, GlcNAc, and glucosamine, similarly to the rep1Δ mutant. The multiple deletion mutants lacking NDT80 (mutants rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ ndt80Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) all showed slightly better growth on nonfermentable carbon sources such as was seen for the ndt80Δ single mutant.

Hyphal morphogenesis.

Cell morphology was first examined after growth under conditions where the wild-type cells predominantly grew as budding cells (minimal glucose medium) (Fig. 3). In contrast, microscopic observation revealed that the ndt80Δ mutants formed connected chains of elongated cells. The multiple deletion mutants of NDT80 (mutants rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ ndt80Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) also showed a similar defect in morphology. To determine whether the mutant cells could form hyphae, they were induced in minimal medium containing either serum or GlcNAc (Fig. 3). As expected, the wild-type strain switched to forming filamentous cells under these conditions. Consistent with previous studies (34), the ndt80Δ mutant was strongly defective in hyphal growth as it instead formed short, elongated cells with a swollen appearance in the presence of the serum or GlcNAc.

FIG 3.

Deletion of NDT80 caused defects in cell separation and hyphal growth. The strains indicated at the top were grown in the medium indicated on the left, and then cell morphology was assessed microscopically. Interestingly, the mutant strains lacking NDT80 (strains ndt80Δ, rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ ndt80Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) displayed a cell separation defect in minimal media containing 50 mM glucose, whereas the other mutants were similar to the wild-type control in that respect. Cells were also grown in liquid medium containing 15% serum or 50 mM GlcNAc to induce hyphal growth. The wild-type control and the ron1Δ mutant showed the formation of filamentous hyphal cells. In contrast, the ndt80 mutant strains were defective, as they formed swollen, slightly elongated cells in the presence of the serum or GlcNAc. Since the rep1Δ mutant could not grow on GlcNAc, 5 mM glucose was added to the GlcNAc medium to support growth of the rep1Δ strains. The rep1Δ and ron1Δ rep1Δ mutants both grew well under these conditions and were induced in vitro to form hyphae by GlcNAc. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h and then photographed. Scale bars indicate 20 µm.

Deletion of REP1 did not affect hyphal induction in serum (Fig. 3). The rep1Δ mutant could not be induced in GlcNAc like the other strains, since it failed to grow on GlcNAc as the sole carbon source (Fig. 2A). On the basis of the inability of rep1Δ cells to grow on GlcNAc, it was suggested they might also be defective in inducing the transcriptional responses needed to form hyphae (26). In order to test this, the rep1Δ cells were induced in minimal GlcNAc medium supplemented with glucose to provide a source of energy. Although glucose can repress the induction of the GlcNAc transporter (35), the low concentration of glucose used in these experiments (5 mM) did not inhibit the hyphal induction by high levels of GlcNAc (50 mM). Interestingly, the rep1Δ mutant was stimulated efficiently by GlcNAc to form hyphae under those growth conditions (Fig. 3). Thus, our result demonstrated that Rep1 is not important for GlcNAc induction of hyphal morphogenesis.

Although we previously reported that Ron1 was defective in responding to GlcNAc to form hyphae in liquid medium (24), the ron1Δ mutant made with CRISPR/Cas9 approaches did not show any obvious defects in responding to GlcNAc or serum (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we also did not detect any synergistic defects in double and triple mutant combinations lacking NDT80 family TFs.

The mutant cells were also tested for the ability to undergo invasive hyphal growth into agar in the presence of different types of media (Fig. 4). Control studies showed the expected results, i.e., that there were essentially no detectable hyphae emanating from the zone of growth for the fungal cells spotted onto minimal glucose medium. In contrast, the wild-type cells formed robust invasive hyphae 5 days after spotting of the cells onto the surface of serum, Spider, and GlcNAc agar plates. The ndt80Δ cells were strongly defective in invasive growth, as there were no hyphal outgrowths seen even after 5 days of incubation on serum and Spider media (Fig. 4). The ndt80Δ mutant showed only rare hyphal outgrowths on agar containing GlcNAc. The rep1Δ mutant was not defective in invasive growth into agar containing serum or Spider media. Although the rep1Δ mutant appeared to be strongly defective for invasion into GlcNAc medium, this was likely due to the poor growth of the rep1Δ mutant on GlcNAc as a sole carbon source (Fig. 2A). The ron1Δ mutant did not show an obvious defect in invasive hyphal growth on agar containing GlcNAc, in contrast to our previous result (24). However, the agar invasion studies revealed an interesting genetic interaction between NDT80 and RON1. Deletion of RON1 partially rescued the hyphal defect of the ndt80Δ mutant on GlcNAc (see the arrow in Fig. 4), indicating a role for RON1 in GlcNAc regulation.

FIG 4.

NDT80 is needed for invasive hyphal growth into agar. The cells indicated at the top were spotted onto the agar plates listed on the left. Serum was present in the medium at 15% (vol/vol), and GlcNAc was present at 2.5 mM. The plates were incubated at 37°C and then photographed after 5 days to record the extent of invasive growth emanating from the edges of the colonies. The deletion mutants lacking NDT80 (mutants ndt80Δ, rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ ndt80Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) were strongly defective in invasive hyphal growth into agar media containing serum, Spider, or GlcNAc. Note that the ron1Δ ndt80Δ double mutant showed an improved ability to form hyphae on GlcNAc (arrow). The deletion mutants of REP1 (mutants rep1Δ, rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ rep1Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) grew poorly and were not detectably induced on GlcNAc. Scale bars indicate 1 mm.

Resistance to stress.

We used a disk diffusion assay to measure the sensitivity of the mutant cells to the antifungal drugs amphotericin B and fluconazole. To quantitatively measure the drug sensitivity, we calculated the average radius in millimeters to the point where 50% growth reduction occurred (RAD50) using diskImageR image analysis software (see Materials and Methods). Statistical analysis showed that the single and double deletion mutants of NDT80 family were similar to the wild type in amphotericin B sensitivity (Fig. 5). The triple deletion mutant (mutant ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) showed a statistically significant increase in sensitivity to amphotericin B, but the magnitude of difference was minor. Although it has been reported that Ndt80 and Rep1 are involved in fluconazole susceptibility (21, 22, 25); surprisingly, our disk diffusion assays did not reveal any significant differences in the fluconazole susceptibility of the mutants compared to the wild type. However, we observed that all the deletion mutants lacking NDT80 failed to show the trailing growth around the fluconazole disks that was seen for the wild-type strain (Fig. 5). Trailing growth (also called tolerance) is due to the slow growth of subpopulations of cells at antifungal drug concentrations above the MIC (36). Because these “tolerant” cells continue to divide in the presence of antifungals, they might contribute to the persistence and/or recurrence of fungal infections (37). Rosenberg demonstrated that fluconazole tolerance was clearly distinct from fluconazole susceptibility measured as MIC in C. albicans (37). Therefore, our result indicates that deletion of NDT80 reduced drug tolerance of C. albicans without affecting the overall susceptibility to fluconazole.

FIG 5.

Sensitivity of mutants to antifungal drugs. The sensitivity to amphotericin B and fluconazole was determined by a disk diffusion assay in which cells were spread onto the surface of an RPMI 1640 medium plate and then filter discs containing 25 µg of the drugs were placed on the surface of the plate. The ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ triple mutant was slightly more sensitive to amphotericin B (AMB) than the wild-type SC5314 strain but was not more sensitive to fluconazole (FLC). None of the mutants showed significant differences in the zone of 50% growth inhibition (RAD50) in fluconazole compared to the wild-type strain. However, the deletion mutants lacking NDT80 (mutants ndt80Δ, rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ ndt80Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) did not show the trailing growth around the fluconazole disks that was seen for the other strains. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h and then photographed. Image analysis software was used to measure the zone of growth inhibition to determine the average radius that corresponded to a 50% growth reduction (RAD50). Double asterisks show statistically significant differences (P < 0.01) from the wild-type strain based on a Student's t test.

The mutant cells were also tested for resistance to other stress conditions (Fig. 6). The ndt80Δ mutant grew poorly in Congo red, which binds and weakens the cell wall. The ndt80Δ mutant also showed sensitivity to the detergent SDS, which likely acts by disrupting the plasma membrane. These results indicate that deletion of NDT80 resulted in defects in cell wall and plasma membrane integrity. A previous study reported that an ndt80Δ mutant showed slow growth at 42°C (23). Although we could not see a growth defect clearly at 42°C, the ndt80Δ mutant showed a very strong growth defect at 44°C (Fig. 6). Deletion of REP1 or RON1 did not appear to further enhance these phenotypes of the ndt80Δ mutant; the double and triple deletion mutants lacking NDT80 (mutants rep1Δ ndt80Δ, ron1Δ ndt80Δ, and ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ) showed the same phenotypes as the ndt80Δ single mutant.

FIG 6.

Sensitivity to cell wall stress and heat stress. The absence of NDT80 resulted in increased sensitivity to Congo red and inhibition of growth at an elevated temperature (44°C). The deletion mutants of NDT80 were also weakly sensitive to SDS. Dilutions of cells were spotted onto YPD plates containing the indicated chemicals. Congo red was present at 140 µM, and SDS was present at 0.06%. The plates were incubated at 30°C and then photographed after 3 days. To examine heat sensitivity, YPD cultures were incubated at 44°C and then photographed after 4 days.

Ndt80 regulates transcription of RAS1.

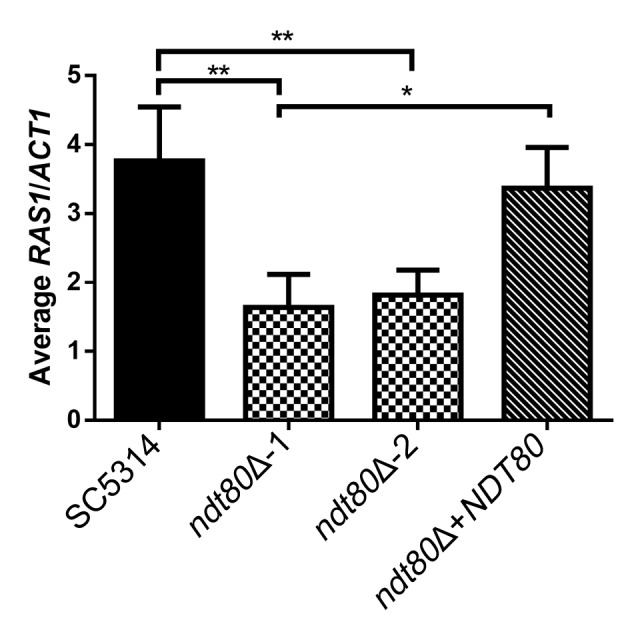

Given that Ndt80 has been found via chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to bind upstream of RAS1 during biofilm formation (10) and that Ras1 is known to play a key role in the cAMP signaling that leads to hyphal growth, we investigated whether Ndt80 regulates RAS1 expression. Using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), we determined ratios of RAS1 expression to ACT1 expression in wild-type SC5314, ndt80Δ, and NDT80-complemented cells grown under hypha-inducing conditions. We observed that both ndt80Δ strains tested had significantly reduced RAS1/ACT1 ratios compared to SC5314 (Fig. 7). Complementing NDT80 back into an ndt80Δ strain restored RAS1 expression to nearly wild-type levels (Fig. 7). Taken together, these results suggest that Ndt80 was a positive regulator of RAS1 expression under the conditions tested.

FIG 7.

Ndt80 regulates expression of RAS1. Deletion of NDT80 resulted in significantly reduced RAS1 expression compared to wild-type strain SC5314. Complementation of an ndt80Δ mutant with NDT80 restored RAS1 expression to nearly wild-type levels. Cells were cultured under hypha-inducing conditions (YNBNP medium, pH 7.0, 37°C) for 1 h prior to RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis for qRT-PCR analysis. Values are shown as ratios of RAS1 transcription to ACT1 transcription. Asterisks show statistically significant differences (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01) from the wild-type strain based on one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons.

DISCUSSION

Use of a recyclable marker system for CRISPR-Cas9 analysis of the NDT80 family.

We further improved the previously reported transient CRISPR-Cas9 system (27) by using a SAT1-FLP system (32) for marker recycling. In this transient CRISPR system, Cas9 and sgRNA are transiently expressed from linear DNA fragments that are not stable in the cells, thereby avoiding integration of CRISPR/Cas9 into the C. albicans genome and the potential problems that could arise from long-term expression of this enzyme (27). The incorporation of a fusion PCR method for generating new sgRNAs streamlined the process of making gene deletions. However, the original system was not adequate to produce multiple deletion mutants since it did not use recyclable markers (27). Huang and Mitchell solved this problem by surrounding the selectable markers with direct repeats, enabling CRISPR-directed marker recycling. In their approach, two auxotrophic marker genes could be used to sequentially delete three or more genes in the same strain (30). Another approach for recycling selectable markers was used by Nguyen et al. in which CRISPR-Cas9 and a selectable marker were integrated in tandem into the genome and were then excised after confirming that the expected genome editing event had occurred (31). Although this method enables rapid gene editing, the initial stable genome integration results in constitutive expression of CRISPR-Cas9 system that could induce off-target mutations in the genome. In the present study, we therefore combined the use of transient CRISPR-Cas9 and a recyclable SAT1-FLP marker for selection. This approach allowed us to construct single, double, and triple mutant combinations of the three NDT80 family genes in a wild-type strain background with no concerns about interference due to auxotrophic markers used for selection and the fact that transient CRISPR/Cas9 system does not generate a permanent disruption of a genomic locus.

Roles of Ndt80 family transcription factors in filamentous hyphal growth.

Using the new CRISPR/Cas9 approaches, we analyzed the effects of deleting the three NDT80-family genes in the same strain background without the use of auxotrophic selection markers. The ndt80Δ mutant was defective in forming hyphae in response to the strong inducers serum and GlcNAc, as expected. Interestingly, we found that Ndt80 regulates the expression of RAS1, which is a key upstream component of the cAMP signaling pathway that is needed for hyphal growth (Fig. 7). These results are consistent with ChIP sequencing (ChIP-Seq) data, which have shown that Ndt80 binds to the promoter region of the RAS1 gene (12). However, the ndt80Δ mutant appears to have a stronger hyphal defect than a ras1Δ mutant (38, 39) indicating that Ndt80 must also regulate other aspects of hyphal growth. In addition, the ndt80Δ mutant showed abnormal cell morphology under budding conditions, which is not seen for ras1Δ mutants (38, 39). Interestingly, Ndt80 was not essential for filamentous growth under all conditions as ndt80Δ cells grown on glycerol medium instead of glucose formed hyphae (Fig. 2B and C). This contrasting phenotype implies that the requirement for Ndt80 in filamentous growth changes depending on the environmental condition.

In this study, deletion of RON1 did not reveal significant phenotypes, in contrast to our previous study of a ron1Δ mutant made with a different approach that indicated a role for RON1 in regulating GlcNAc signaling (24). However, the ndt80Δ ron1Δ double mutant had an improved ability to form hyphae on GlcNAc medium, which is consistent with a role for RON1 in GlcNAc regulation. This phenotype suggests that RON1 can act as a negative regulator of filamentous growth response to GlcNAc in the absence of NDT80. ChIP-Seq performed by Nocedal et al. showed that Ron1 binds to many fewer genomic regions but that all those sites are also bound by Ndt80 (12). This suggests that Ron1 may influence expression of a subset of genes regulated by Ndt80.

Our results indicated that Rep1 was not needed for hyphal induction when cells were stimulated by GlcNAc (Fig. 3). This contrasts with a suggestion from the previous study by Su et al. (26). They predicted that Rep1 could be involved in stimulating hyphal growth because it is needed to induce GlcNAc catabolic genes by recruiting the histone acetyltransferase, Ngs1, to the promoter region of these GlcNAc genes (26). However, when the rep1Δ mutant was supplied with an alternative sugar to promote growth, it could be induced to form hyphae in response to GlcNAc (Fig. 3). This is consistent with the previous finding that GlcNAc induction of hyphal morphogenesis in C. albicans is not dependent on its metabolism (40).

Roles of NDT80 family transcription factors in response to drugs and stress.

Previous studies reported that the ndt80Δ mutant was sensitive to fluconazole whereas the rep1Δ mutant was resistant to fluconazole (22, 25). The authors of those studies used spot assays, which do not quantify the changes in drug sensitivity. To compare fluconazole sensitivities in a quantitative manner, we used disk diffusion assays, which showed that three different deletion mutants lacking the NDT80 family genes were not significantly different from the wild-type strain (Fig. 5). Instead, we found that the ndt80Δ mutant was distinct in that it did not show the typical trailing growth that is seen with the wild-type strain. Rosenberg et al. demonstrated that this type of drug tolerance is clearly distinct from susceptibility/resistance measured as MIC or halo size (37). We also found that the ndt80Δ mutant was susceptible to Congo red, SDS, and high temperature (Fig. 6). These phenotypes suggest that Ndt80 has multiple functions in stress response under various conditions.

Limited genetic interactions among the members of the NDT80 family.

We hypothesized that the three NDT80 family genes might display strong genetic interactions due to the similarity of their DBDs. Surprisingly, in spite of the fact that a previous study indicated that Ron1 binds to a subset of Ndt80 binding sites in the genome, we observed only a weak genetic interaction between ndt80Δ and ron1Δ for GlcNAc-induced hyphal growth and did not detect other evidence for genetic interactions. Furthermore, deletion of REP1 did not alter the hyphal defect of the ndt80Δ mutant or show a genetic interaction with ron1Δ. Similarly, deletion of RON1 or NDT80 did not change the growth defect of the rep1Δ mutant on galactose, glucosamine, or GlcNAc, which is consistent with the fact that Ndt80 and Ron1 did not bind to the promoters of GlcNAc catabolic genes (12) that are reported to be bound by Rep1 (26). These results suggest that the three NDT80 family TFs are functionally independent and that their regulatory networks do not affect each other. A further sign of this is that Nocedal et al. did not detect the binding of Ndt80 or Ron1 to each other’s promoter regions or to the promoter region of REP1 (12). Consistent with this, even the ron1Δ rep1Δ ndt80Δ triple mutant displayed a phenotype similar to the combined phenotypes of the corresponding single mutants.

The failure to detect genetic interactions for the NDT80 family is in sharp contrast to the results of analysis of other genetic networks, such as the transcription factors involved in biofilm formation (Bcr1, Brg1, Efg1, Ndt80, Rob1, and Tec1) (33). In the latter case, many double mutants showed synergistic defects and were severely defective in biofilm formation. The biofilm network showed properties of a highly interdependent network that is susceptible to genetic perturbation (10, 33). It is interesting that Ndt80 is highly interconnected with other transcription factors in the biofilm network whereas it is largely independent of the other NDT80 family transcription factors in spite of their conserved DBD. The roles for the three NDT80-family genes in C. albicans therefore appear to be similar to the function of the multiple NDT80-family genes found in filamentous fungi. The NDT80 family TFs in filamentous fungi fall into two main groups; one group has functions in sexual development, and the other has various functions in metabolism, including GlcNAc catabolism (13–15, 19). Taken together, these results help us to understand the role of the highly conserved NDT80 family of transcription factors in fungi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The genotypes of the C. albicans strains that were used are described in Table 1. All strains were stored in 15% glycerol stocks at −80°C. All C. albicans strains were streaked from −80°C onto YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) plates every week and incubated at 30°C. C. albicans transformants were selected on YPD plus 200 µg/ml nourseothricin (NAT; Werner BioAgents) for nourseothricin-resistant (Natr) isolates. To obtain nourseothricin-sensitive (Nats) derivatives, transformants were grown overnight in maltose medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% maltose). Cells were then spread on YPD plates containing 25 µg/ml of NAT and incubated for 2 days at 30°C. Nats colonies were screened by their colony size, which was smaller than that of their Natr parental strains.

Fungal strains were tested for growth on different sugars by spotting dilutions of cells on synthetic agar medium containing 0.67% yeast nitrogen base with ammonium sulfate and the indicated carbon source. Fungal strains were also tested for resistance to different stress conditions by spotting dilutions of cells on YPD agar medium containing 140 µM Congo red or 0.06% SDS or by incubation at 44°C. Strains were grown overnight in YPD with shaking and adjusted to 2 × 107 cells/ml, and then 5-fold dilutions of cells were prepared. A 3-µl aliquot of each dilution was then spotted onto the indicated type of plate, and the plates were incubated at 30°C or 44°C as indicated.

The ability to form hyphae in liquid media was analyzed with cells grown overnight at 30°C in YPD. The cells were then diluted to 2 × 106 cells/ml into synthetic medium containing 50 mM glucose. After 3 h of incubation at 30°C, hyphal growth was induced by a shift in temperature to 37°C in combination with 15% bovine serum. For N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) induction, the cells were diluted into synthetic medium containing 50 mM GlcNAc and incubated at 37°C. Glucose (5 mM) was added to the GlcNAc medium to support growth of the rep1Δ strains.

Invasive hyphal morphogenesis was analyzed by spotting 3 µl of serial dilutions of cells on an agar plate with the indicated type of medium and then incubating at 37°C. Cells were induced on synthetic medium containing 2.5 mM GlcNAc, agar medium containing 15% bovine serum, or Spider medium. The morphology of the cells at the edge of the zone of growth was photographed to record the extent of invasive hyphal growth into the agar.

Assaying susceptibility to antifungal drugs with disk diffusion assays.

C. albicans cells were grown overnight in YPD, and then 2.5 × 105 cells were spread onto 20-ml RPMI 1640 agar plates. Stock solutions of amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) and fluconazole (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) were prepared at 10 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). A 2.5-µl volume of the stock solution (25 µg) was spotted onto 6-mm-diameter paper disks and allowed to dry in the dark. A single paper disk was placed in the center of each plate, and then the plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h and each plate was photographed individually. Analysis of the disk diffusion assay was done using the diskImageR package from the R library. The diskImageR analysis measured pixel intensity corresponding to cell density and calculated the average radius in millimeters to the point where 50% growth reduction occurred (RAD50) (41).

Macroscopic and microscopic analysis of cells.

Cells were allowed to grow on solid agar media for the indicated number of days and then photographed. Unless otherwise noted, all spot assays were completed as at least three independent replicates, and a representative data set is shown. To record the extent of invasive hyphal growth into the agar, the cells at the edge of the zone of growth were photographed using an Olympus BH2 microscope equipped with a 4× objective and a Zeiss AxioCam digital camera. To image the morphology of cells under hypha-inducing conditions, the cells in liquid medium were concentrated by centrifugation and then photographed using differential interference contrast (DIC) optics. Photographic images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Observer 7 inverted microscope equipped with a 100× objective and a Zeiss AxioCam 702 digital camera.

DNA and plasmids.

The single, double, and triple mutant strains of NDT80 family were created using transient expression of CRISPR-Cas9 to facilitate the homozygous deletion of a target gene. The methods were performed essentially as described previously (27). We used 20-bp target sequences of the sgRNA, as reported previously by Vyas et al. (28), to delete NDT80 (target sequence GCATGCCCGTATTGATAGA), REP1 (TGTAGTGTAGCCATACTCGC), and RON1 (TCTCCCCACTTAAAGCAGCT). Gene deletion PCR constructs were synthesized using plasmid pGR-NAT as the template. The pGR-NAT plasmid has a full cassette of SAT1 flipper (32). The primers were designed to include 60 to 80 bases of homology to the sequences upstream or downstream from the target gene. PCR was conducted with Ex Taq in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.).

The complemented strains of the NDT80 family were constructed by integrating a copy of the wild-type gene sequence into the genome. The NDT80, REP1, and RON1 plasmids were constructed by PCR amplification of genomic DNA from 1 kb upstream of the start codon and 0.5 kb downstream of the stop codon of the NDT80, REP1, and RON1 genes, respectively. PCR was conducted with Phusion in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer (New England Biolabs, Inc.). The primers were designed to include 20 bases with homology to CIp10-SAT1, a SAT1-marked version of plasmid CIp10 (42, 43). The DNA fragments were then inserted at EcoRI restriction site of the CIp10-SAT1 plasmid using Gibson assembly master mix (New England Biolabs, Inc.). The constructed plasmids were linearized by the use of StuI and integrated into the RPS1 locus of the fungal strains.

Fungal transformation.

PCR products and linearized plasmids for transformation were purified and concentrated by the use of a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen N.V.). Electroporation was used to introduce the DNA into the cells in order to obtain optimal transformation efficiency. The electrocompetent fungal cells were prepared following a previously described method (44). A cell suspension (40 µl) was added to aliquoted DNA, placed in electroporation cuvettes, and electroporated on a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser at 1.5 kV. One milliliter of 0.5× YPD containing 1 M sorbitol was added immediately to the cuvette, and then the cell mixture was incubated for 3 h at 30°C before plating onto selective media was performed. Natr transformants were selected, and PCR genotyping of the transformants verified that both copies of the target gene had been deleted. Marker excision was mediated by the maltose-inducible FLP recombinase, and NATs cells were screened as described above (32).

qRT-PCR.

Fungal cells were grown overnight in YPD, washed once with phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and resuspended in phosphate buffer. Approximately 4.5 × 106 cells were inoculated in 5 ml YNBNP medium (0.67% YNB, 0.2% glucose, 25 mM phosphate buffer, 5 mM GlcNAc) at pH 7.0 and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. RNA was extracted using a MasterPure yeast RNA purification kit (Epicentre). DNA contamination was removed by the use of a Turbo DNA-free kit (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng DNase-treated RNA using a RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific), following the manufacturer’s instructions for the random hexamer primer (IDT) and GC rich template. qRT-PCR was performed on a CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad), using SsoFast Evergreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) with the indicated primers to detect ACT1 (forward primer, 5′-ACTACCATGTTCCCAGGTATTG-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CCACCAATCCAGACAGAGTATT-3′) and RAS1 (forward primer, 5′-TATCAAGATGGATTAGCATTCG-3′; reverse primer, 5′-ATATTGGTCTTGACCTTGTTG-3′). Thermocycler conditions were as follows: 95°C for 30 s followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 65°C for 3 s, and 95°C for 5 s. RAS1 transcripts were normalized to ACT1 transcripts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH award R01GM116048 to J.B.K. and R01AI127548 to D.A.H. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis 39:309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. 2010. Epidemiology of invasive mycoses in North America. Crit Rev Microbiol 36:1–53. doi: 10.3109/10408410903241444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. 2012. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 4:165rv13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher MC, Hawkins NJ, Sanglard D, Gurr SJ. 2018. Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science 360:739–742. doi: 10.1126/science.aap7999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudbery PE. 2011. Growth of Candida albicans hyphae. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:737–748. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkel JS, Mitchell AP. 2011. Genetic control of Candida albicans biofilm development. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:109–118. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biswas S, Van Dijck P, Datta A. 2007. Environmental sensing and signal transduction pathways regulating morphopathogenic determinants of Candida albicans. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71:348–376. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00009-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteway M, Bachewich C. 2007. Morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Annu Rev Microbiol 61:529–553. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis DA. 2009. How human pathogenic fungi sense and adapt to pH: the link to virulence. Curr Opin Microbiol 12:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nobile CJ, Fox EP, Nett JE, Sorrells TR, Mitrovich QM, Hernday AD, Tuch BB, Andes DR, Johnson AD. 2012. A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell 148:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y, Su C, Liu H. 2014. Candida albicans hyphal initiation and elongation. Trends Microbiol 22:707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nocedal I, Mancera E, Johnson AD. 2017. Gene regulatory network plasticity predates a switch in function of a conserved transcription regulator. Elife 6:e23250. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz ME, Cooper S. 2015. Extreme diversity in the regulation of Ndt80-like transcription factors in fungi. G3 (Bethesda) 5:2783–2792. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.021378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchison EA, Glass NL. 2010. Meiotic regulators Ndt80 and Ime2 have different roles in Saccharomyces and Neurospora. Genetics 185:1271–1282. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.117184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz ME, Braunberger K, Yi G, Cooper S, Nonhebel HM, Gondro C. 2013. A p53-like transcription factor similar to Ndt80 controls the response to nutrient stress in the filamentous fungus, Aspergillus nidulans. F1000Res 2:72. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-72.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caddick MX, Arst HN. 1986. Structural genes for phosphatases in Aspergillus nidulans. Genet Res 47:83–91. doi: 10.1017/S0016672300022904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu S, DeRisi J, Eisen M, Mulholland J, Botstein D, Brown PO, Herskowitz I. 1998. The transcriptional program of sporulation in budding yeast. Science 282:699–705. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hepworth SR, Friesen H, Segall J. 1998. NDT80 and the meiotic recombination checkpoint regulate expression of middle sporulation-specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 18:5750–5761. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.10.5750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dementhon K, Iyer G, Glass NL. 2006. VIB-1 is required for expression of genes necessary for programmed cell death in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot Cell 5:2161–2173. doi: 10.1128/EC.00253-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kappel L, Gaderer R, Flipphi M, Seidl-Seiboth V. 2016. The N-acetylglucosamine catabolic gene cluster in Trichoderma reesei is controlled by the Ndt80-like transcription factor RON1. Mol Microbiol 99:640–657. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasse C, Schillig R, Dierolf F, Weyler M, Schneider S, Mogavero S, Rogers PD, Morschhäuser J. 2011. The transcription factor Ndt80 does not contribute to Mrr1-, Tac1-, and Upc2-mediated fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans. PLoS One 6:e25623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen CG, Yang YL, Shih HI, Su CL, Lo HJ. 2004. CaNdt80 is involved in drug resistance in Candida albicans by regulating CDR1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:4505–4512. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4505-4512.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Homann OR, Dea J, Noble SM, Johnson AD. 2009. A phenotypic profile of the Candida albicans regulatory network. PLoS Genet 5:e1000783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naseem S, Min K, Spitzer D, Gardin J, Konopka JB. 2017. Regulation of hyphal growth and N-acetylglucosamine catabolism by two transcription factors in Candida albicans. Genetics 206:299–314. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.201491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CG, Yang YL, Tseng KY, Shih HI, Liou CH, Lin CC, Lo HJ. 2009. Rep1p negatively regulating MDR1 efflux pump involved in drug resistance in Candida albicans. Fungal Genet Biol 46:714–720. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su C, Lu Y, Liu H. 2016. N-acetylglucosamine sensing by a GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase induces transcription via chromatin histone acetylation in fungi. Nat Commun 7:12916. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Min K, Ichikawa Y, Woolford CA, Mitchell AP. 2016. Candida albicans gene deletion with a transient CRISPR-Cas9 system. mSphere 1:e00130-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00130-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vyas VK, Barrasa MI, Fink GR. 2015. A Candida albicans CRISPR system permits genetic engineering of essential genes and gene families. Sci Adv 1:e1500248. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng H, Dean N. 2017. Dramatic improvement of CRISPR/Cas9 editing in Candida albicans by increased single guide RNA expression. mSphere 2:e00385-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00385-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang MY, Mitchell AP. 2017. Marker recycling in Candida albicans through CRISPR-Cas9-induced marker excision. mSphere 2:e00050-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00050-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen N, Quail MMF, Hernday AD. 2017. An efficient, rapid, and recyclable system for CRISPR-mediated genome editing in Candida albicans. mSphere 2:e00149-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphereDirect.00149-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reuss O, Vik A, Kolter R, Morschhauser J. 2004. The SAT1 flipper, an optimized tool for gene disruption in Candida albicans. Gene 341:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glazier VE, Murante T, Murante D, Koselny K, Liu Y, Kim D, Koo H, Krysan DJ. 2017. Genetic analysis of the Candida albicans biofilm transcription factor network using simple and complex haploinsufficiency. PLoS Genet 13:e1006948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sellam A, Askew C, Epp E, Tebbji F, Mullick A, Whiteway M, Nantel A. 2010. Role of transcription factor CaNdt80p in cell separation, hyphal growth, and virulence in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 9:634–644. doi: 10.1128/EC.00325-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alvarez FJ, Konopka JB. 2007. Identification of an N-acetylglucosamine transporter that mediates hyphal induction in Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell 18:965–975. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e06-10-0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brauner A, Fridman O, Gefen O, Balaban NQ. 2016. Distinguishing between resistance, tolerance and persistence to antibiotic treatment. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:320–330. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg A, Ene IV, Bibi M, Zakin S, Segal ES, Ziv N, Dahan A, Colombo AL, Bennett RJ, Berman JG. 2018. Clearing the FoG: antifungal tolerance is a subpopulation effect that is distinct from resistance and is associated with persistent candidemia. bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/03/02/206359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Parrino SM, Si H, Naseem S, Groudan K, Gardin J, Konopka JB. 2017. cAMP-independent signal pathways stimulate hyphal morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol 103:764–779. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grahl N, Demers EG, Lindsay AK, Harty CE, Willger SD, Piispanen AE, Hogan DA. 2015. Mitochondrial activity and Cyr1 are key regulators of Ras1 activation of C. albicans virulence pathways. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005133. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naseem S, Gunasekera A, Araya E, Konopka JB. 2011. N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) induction of hyphal morphogenesis and transcriptional responses in Candida albicans are not dependent on its metabolism. J Biol Chem 286:28671–28680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.249854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerstein AC, Rosenberg A, Hecht I, Berman J. 2016. diskImageR: quantification of resistance and tolerance to antimicrobial drugs using disk diffusion assays. Microbiology 162:1059–1068. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vylkova S, Lorenz MC. 2014. Modulation of phagosomal pH by Candida albicans promotes hyphal morphogenesis and requires Stp2p, a regulator of amino acid transport. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003995. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murad AM, Lee PR, Broadbent ID, Barelle CJ, Brown AJ. 2000. CIp10, an efficient and convenient integrating vector for Candida albicans. Yeast 16:325–327. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Backer MD, Maes D, Vandoninck S, Logghe M, Contreras R, Luyten WH. 1999. Transformation of Candida albicans by electroporation. Yeast 15:1609–1618. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]